Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

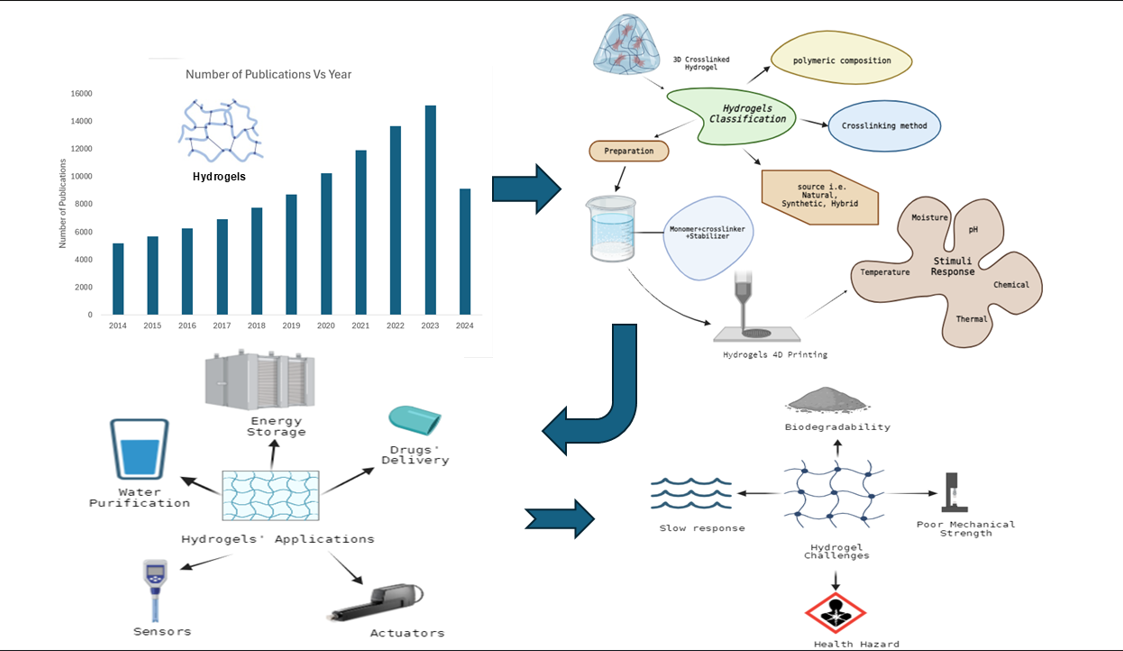

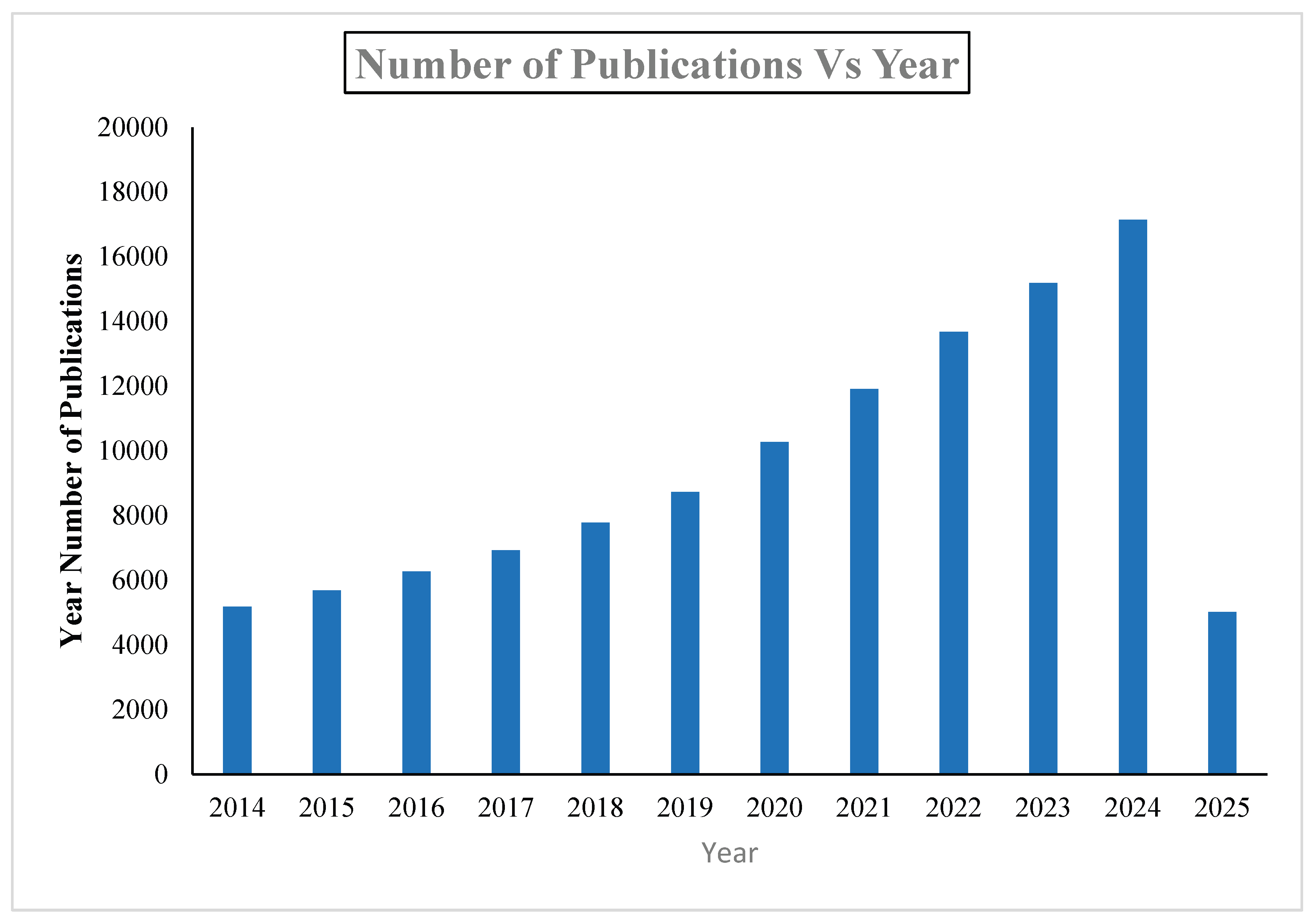

1. Introduction

2. Classification of Hydrogels

2.1. Classification Based on Crosslink Type

2.2. Classification Based on Source

2.2.1. Natural Hydrogels

2.2.2. Synthetic Hydrogels

2.2.3. Hybrid Hydrogels

2.3. Classification According to Polymeric Composition

2.3.1. Homopolymeric Hydrogels

2.3.2. Copolymeric Hydrogels

2.3.3. Multipolymer Interpenetrating Polymeric Hydrogel

3. Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels

3.1. Moisture-Responsive Hydrogels

3.2. Thermo-Responsive Hydrogels

3.3. Chemical-Responsive Hydrogel

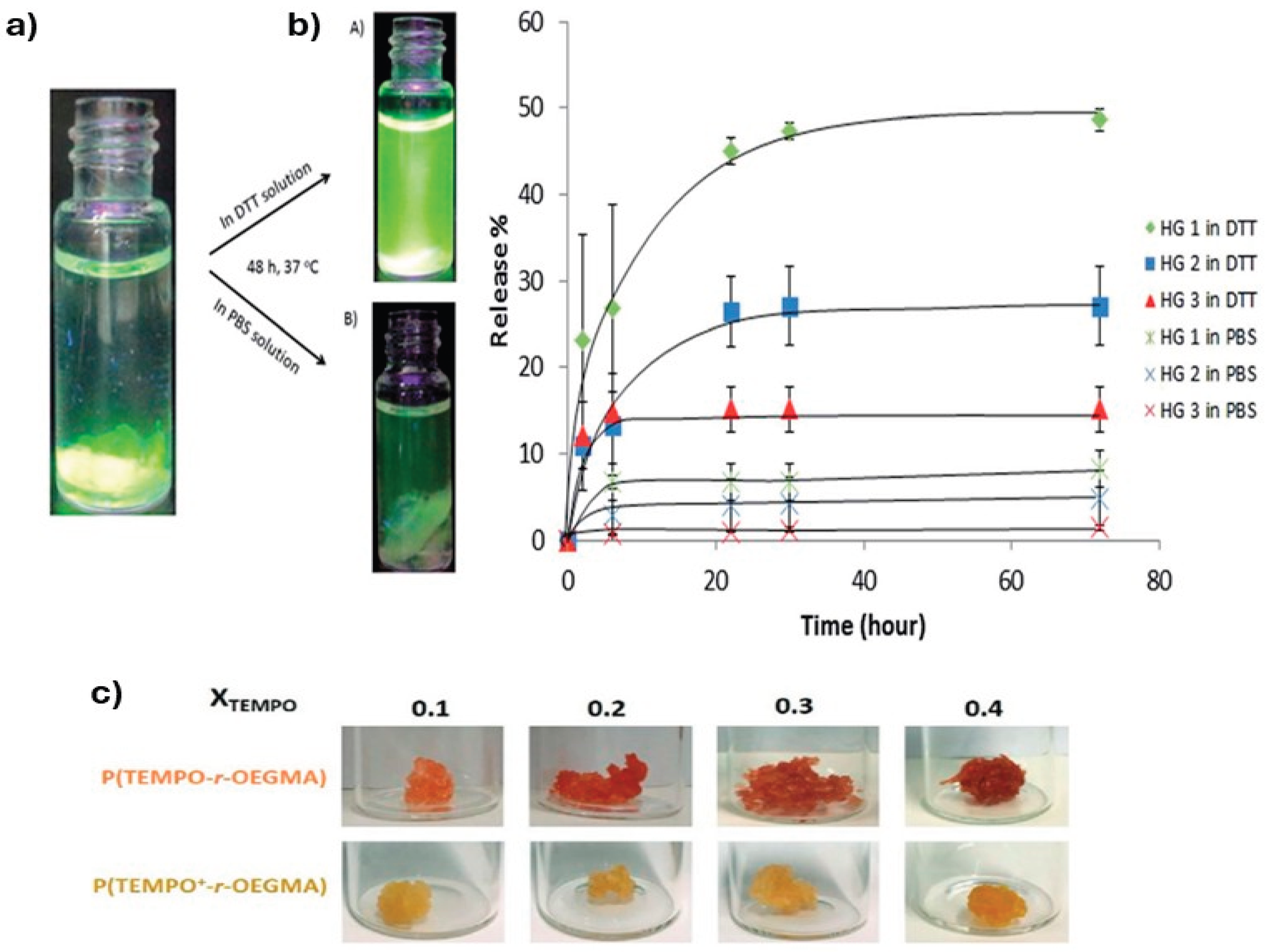

3.4. Redox-Responsive Hydrogels

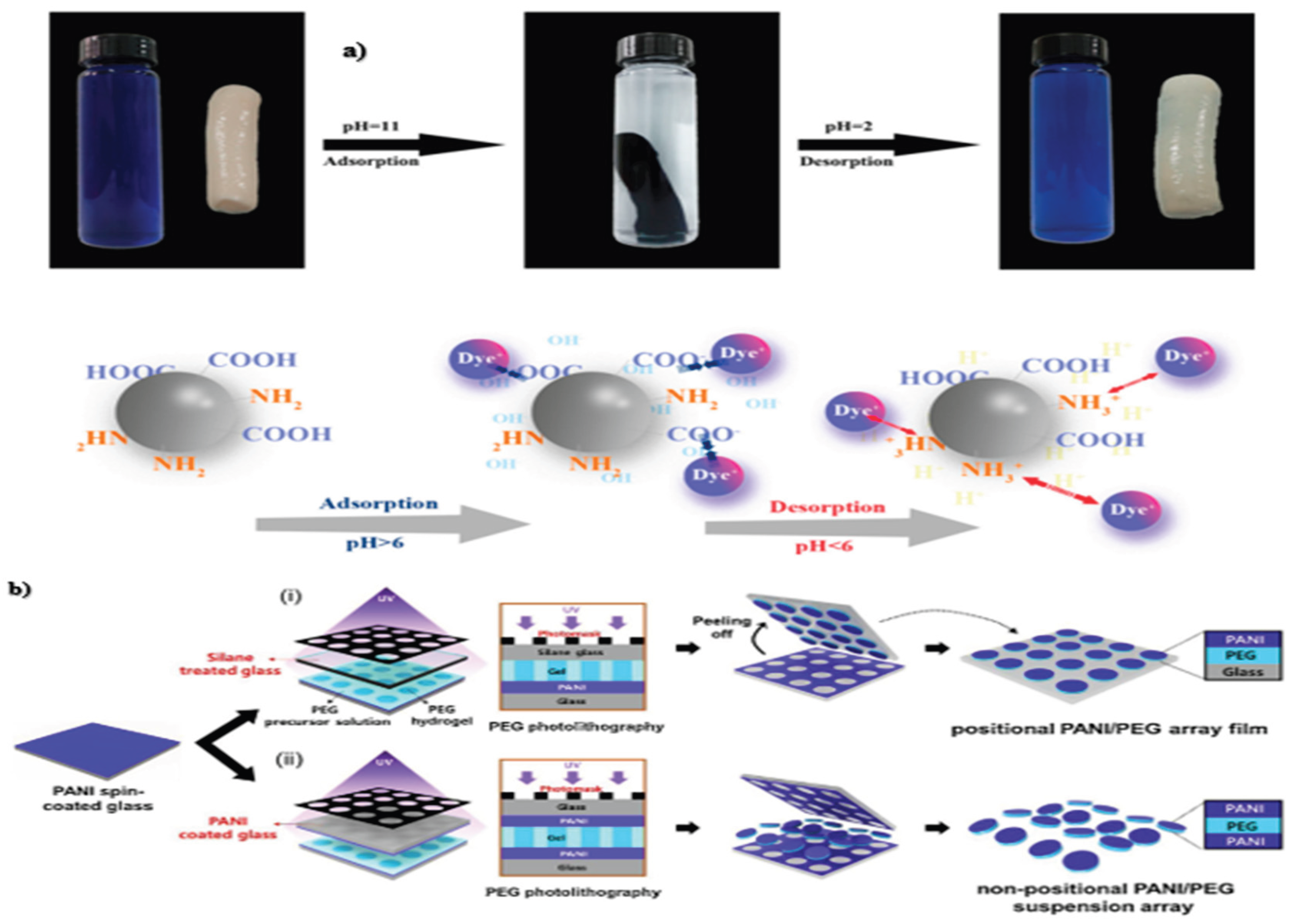

3.5. pH-Responsive Hydrogels

3.6. Other Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels

4. Applications

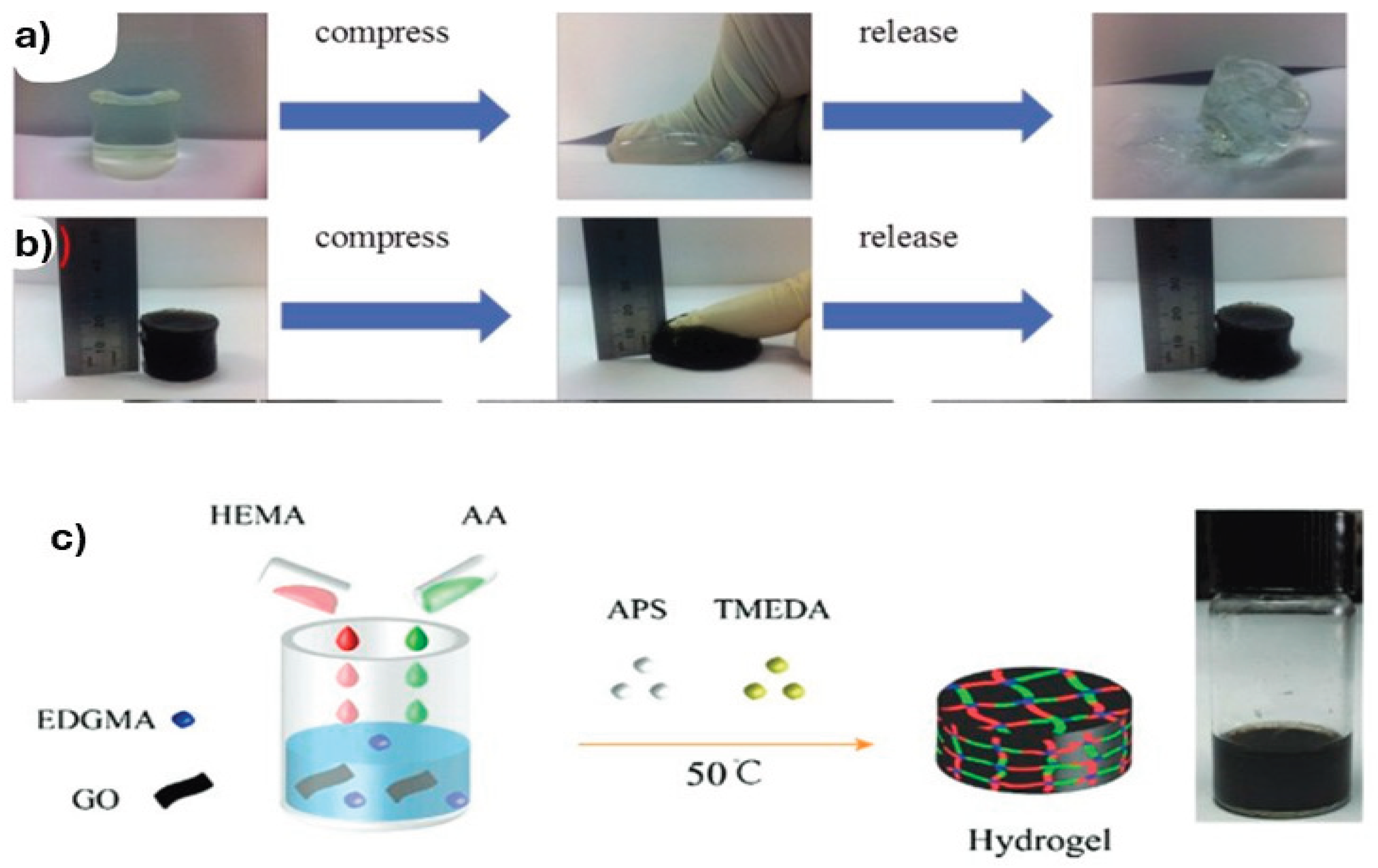

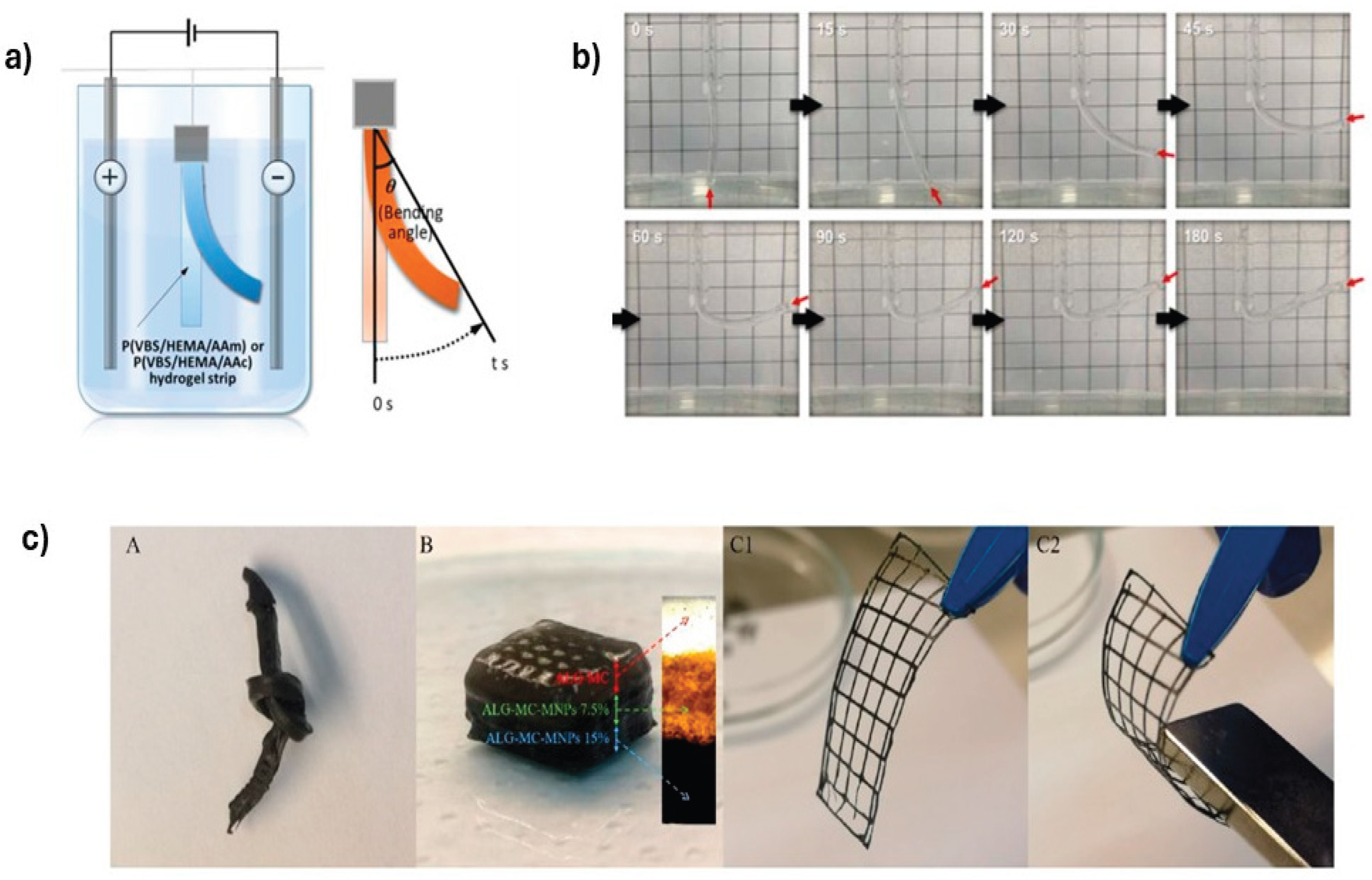

4.1. Actuators

4.2. Energy Storage

4.3. Sensors

4.4. Soft Robotics

4.5. Drug Delivery

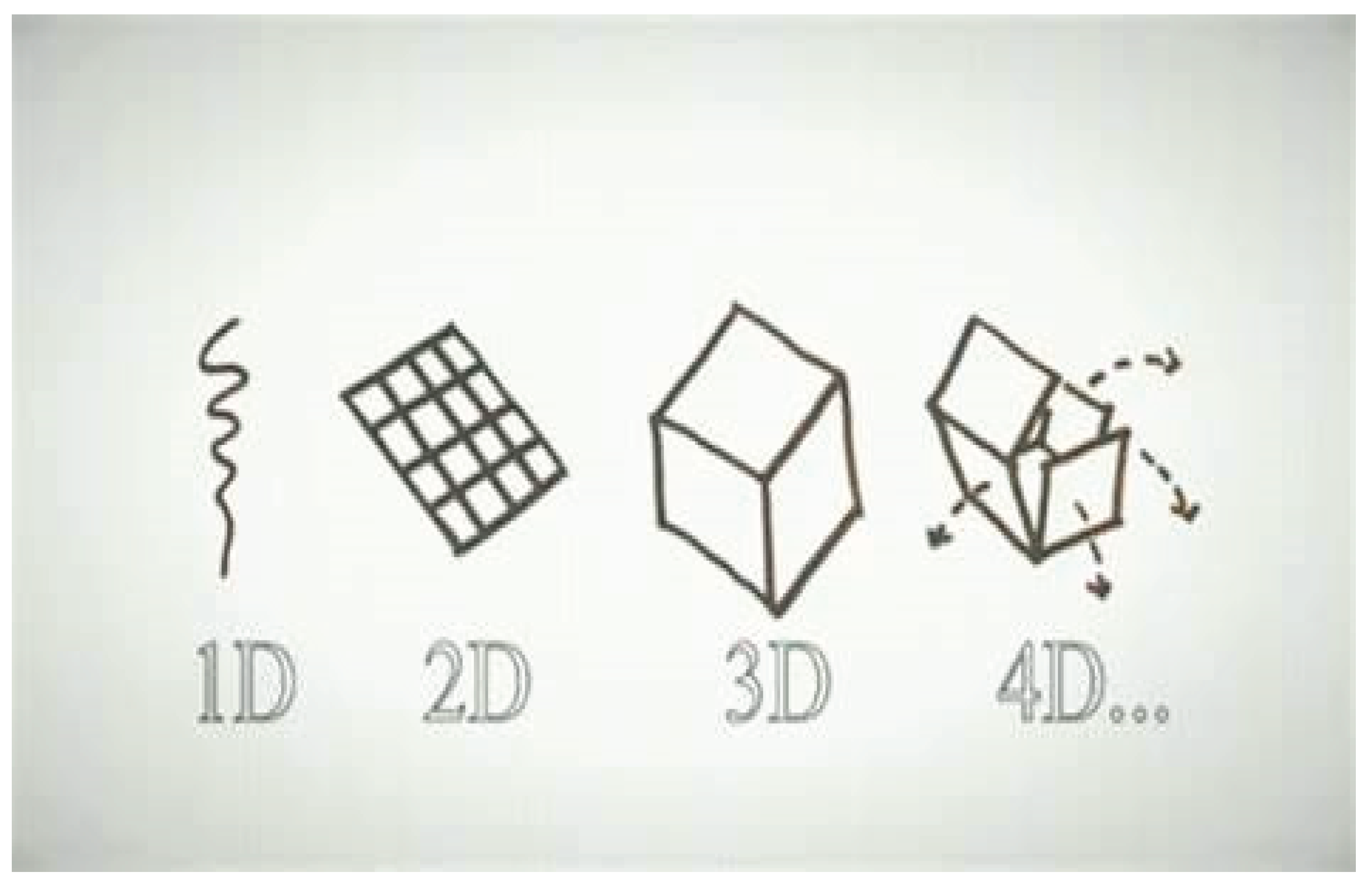

5. Printing Technologies and Material Requirements

5.1. Vat Photopolymerization

5.1.1. Stereolithography

5.1.2. Digital Light Processing

5.2. Extrusion-Based Printing Techniques

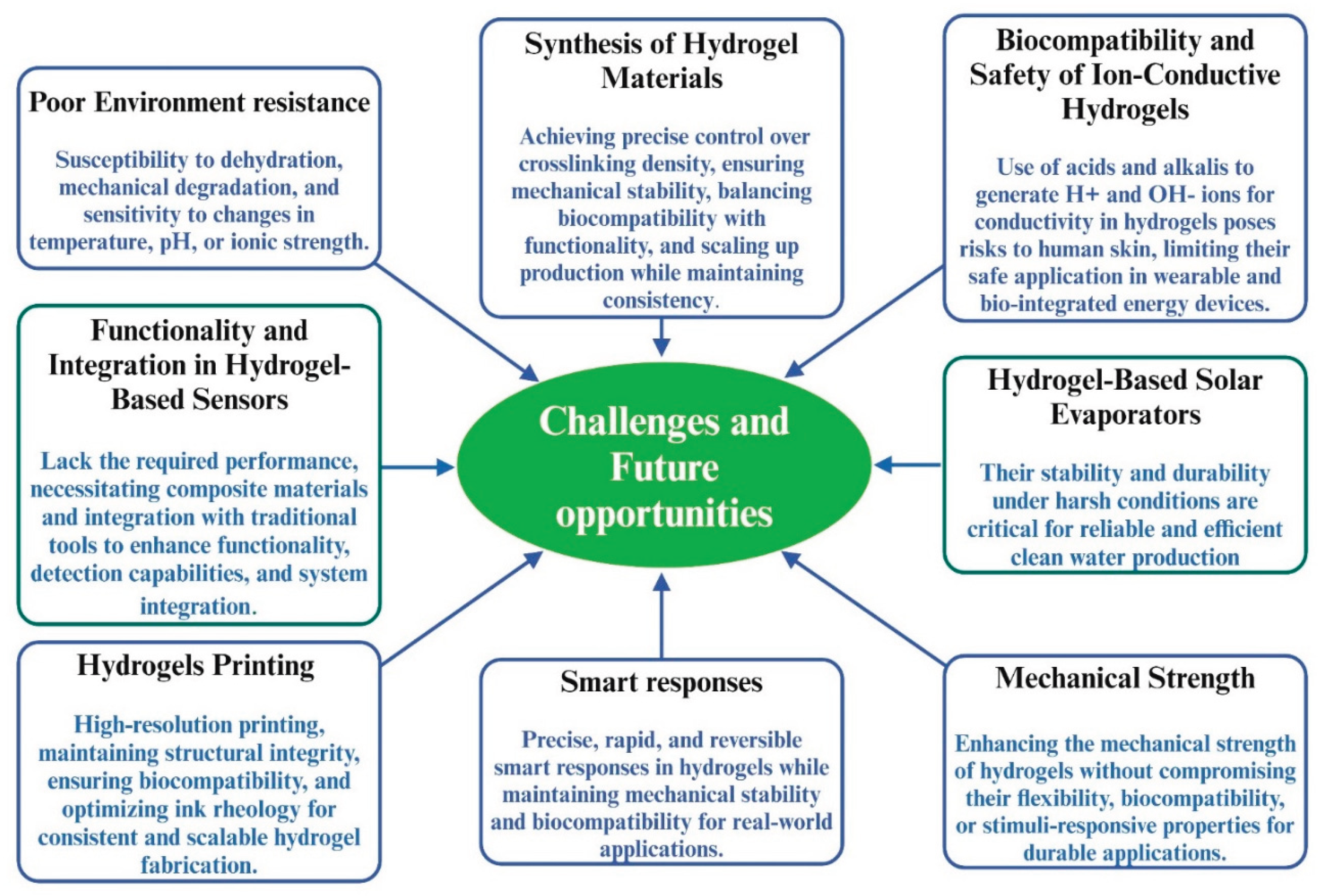

6. Challenges and Future Opportunities

- (1)

- For instance, conventional conductive hydrogels are limited to moderate environments due to their poor environmental resilience. Their high-water content and hydrophilic structure cause them to swell undesirably in humid conditions, freeze at sub-zero temperatures, and dehydrate through evaporation, compromising their structural integrity [291]. However, conductive hydrogels are typically designed to achieve desired properties by incorporating many conductive fillers. However, this often weakens the gels' mechanical properties due to reduced network compatibility caused by the aggregation of conductive materials. As a result, this restricts their practical applications, particularly in wearable electronics, which necessitate a blend of high conductivity, stretchability, fracture strength, appropriate modulus, and quick self-recovery. Therefore, ongoing efforts are necessary to meticulously choose the raw materials, optimize fabrication methods, and refine structural designs [292]. Moreover, developing suitable ink for printing requires balancing tunable rheology with printing quality, as highly concentrated ink offers rapid prototyping. Still, it can result in rigid, less responsive devices, while dilute ink improves flexibility but sacrifices shape fidelity and speed [293].

- (2)

- Natural hydrogels derived from renewable and cost-effective sources like starch form a fascinating category of biopolymeric materials. They are being progressively employed in a diverse range of applications spanning the biomedical, cosmeceutical, and food industries. However, the synthesis of these materials is hampered by lengthy processing times, high energy consumption, and safety concerns, which often result in significant environmental damage. These issues are major obstacles to their broader utilization [294]. There are several limitations related to the printability of natural hydrogels, for example, the mechanical performance, specifically the elastic modulus, is lower in the permanent state compared to the temporary state after the printing [295].

- (3)

- Hydrogels have emerged as promising materials for energy conversion and storage systems. Most ion-conductive hydrogel electrolytes derive their conductivity from the movement of H+ and OH- ions. However, generating these ions typically requires the use of acids and alkalis, which can be harmful to human skin. This presents a challenge for their application in wearable electronic devices. While the preparation methods and technologies for hydrogel electrolytes are relatively mature, there is significant room for improvement in material selection. Developing environmentally and socially sustainable materials, or using biodegradable hydrogels as electrolyte or electrode materials, is an urgent need today and market [296].Figure 22. Challenges and Opportunities in Hydrogels.

- (1)

- Another area where hydrogels are making strides is sensors. Hydrogel material alone often falls short of meeting application demands, so composite materials are used to introduce additional functionalities. The synergy between hydrogels and other traditional analytical tools is leveraged. While hydrogels do not always surpass existing techniques, they enhance functionality, facilitate detection, and integrate multiple sensor components into a single system.

- (2)

- Hydrogel-based evaporators have outperformed many reported evaporators, offering distinct advantages. However, challenges and opportunities remain to enhance their strengths. For instance, a deeper understanding of the fundamental evaporation mechanism within hydrogels is needed. Additionally, the stability and durability of hydrogel-based solar evaporators under severe conditions require improvement to ensure stable clean water delivery in practical applications [297].

- (3)

- Achieving high-strength hydrogels requires overcoming limitations such as balancing mechanical robustness with flexibility, ensuring biocompatibility, and enhancing stability under varying environmental conditions. Developing tunable mechanical properties for specific applications, integrating multiple enhancement strategies for synergistic effects, and understanding structure-property relationships through advanced characterization techniques remain critical hurdles [298,299]. Additionally, creating scalable and sustainable fabrication methods while maintaining performance consistency poses significant challenges.

- (4)

- The widespread adoption of 3D hydrogel printing faces several critical hurdles, including optimizing material properties for improved printability and bioactivity, enhancing printing techniques for higher resolution and speed, and designing complex scaffold architectures with functional gradients and vascular networks. Post-printing processing, such as ensuring structural integrity and functionality, along with the challenges of scaling up to high-throughput manufacturing, further complicate its implementation. Additionally, the clinical translation of 3D-printed hydrogels requires addressing regulatory and ethical considerations, as well as ensuring reproducibility and biocompatibility for real-world applications [300,301,302].

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| AA | Ascorbic Acid |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| CAD | Computer Aided Design |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl cellulose |

| CNF | Cellulose Nanofiber |

| CNT | Carbon Nanotubes |

| CS | Chitosan |

| DIW | Direct Ink Writing |

| DLP | Digital Light Processing |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| GO | Graphene Oxide |

| IPN | Interpenetrating Polymer Network |

| LCST | Lower Critical Solution Temperature |

| MBA | NN′-Methylenebis(acrylamide) |

| NIPAm | N-isopropylacrylamide |

| PAA | Poly(acrylic acid) |

| PAM | Polyacrylamide |

| PANI | Polyaniline |

| PEDOT | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): polystyrene sulfonate |

| PEG | Poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PEGDA | Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate |

| PEGDMA | Polyethylene glycol dimethacrylate |

| PI | Photoinitiator |

| PNIPAm | Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) |

| PVA | Polyvinyl Alcohol |

| SLA | Stereolithography |

| SPIONs | Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles |

| TPO | Diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)-phosphine oxide |

| TOCN | TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofiber |

References

- Seliktar, D. Designing Cell-Compatible Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Science (1979) 2012, 336, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wan, C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, S.; Dai, Z.; Ji, K.; Jiang, H.; Chen, X.; Long, Y.; et al. Highly Stretchable, Elastic, and Ionic Conductive Hydrogel for Artificial Soft Electronics. Adv Funct Mater 2019, 29, 1806220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichterle, O.; Lím, D. Hydrophilic Gels for Biological Use. Nature 1960, 185:4706 1960(185), 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg Guru, S.; Khalsa, R.; Garg Guru, A. Hydrogel: Classification, Properties, Preparation and Technical Features; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Narain, R.; Zeng, H. Hydrogels; Polymer Science and Nanotechnology: Fundamentals and Applications, 2020; pp. 203–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Han, L.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Hu, W.; Gu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zeng, H. Rapid Dewatering and Consolidation of Concentrated Colloidal Suspensions: Mature Fine Tailings via Self-Healing Composite Hydrogel. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11, 21610–21618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk, H.; Lin, S.; Ma, C.; Takaffoli, M.; Fang, N.X.; Zhao, X. Hydraulic Hydrogel Actuators and Robots Optically and Sonically Camouflaged in Water. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Lu, W.; Yang, X.; He, J.; Le, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Serpe, M.J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, T. Bioinspired Anisotropic Hydrogel Actuators with On–Off Switchable and Color-Tunable Fluorescence Behaviors. Adv Funct Mater 2018, 28, 1704568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Peng, Q.; Thundat, T.; Zeng, H. Stretchable, Injectable, and Self-Healing Conductive Hydrogel Enabled by Multiple Hydrogen Bonding toward Wearable Electronics. Chemistry of Materials 2019, 31, 4553–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yan, B.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Zeng, H. Novel Mussel-Inspired Injectable Self-Healing Hydrogel with Anti-Biofouling Property. Advanced Materials 2015, 27, 1294–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maulvi, F.A.; Lakdawala, D.H.; Shaikh, A.A.; Desai, A.R.; Choksi, H.H.; Vaidya, R.J.; Ranch, K.M.; Koli, A.R.; Vyas, B.A.; Shah, D.O. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of Novel Implantation Technology in Hydrogel Contact Lenses for Controlled Drug Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 226, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, D.; Nagao, M.; Hall, D.G.; Thundat, T.; Narain, R. Injectable Self-Healing Zwitterionic Hydrogels Based on Dynamic Benzoxaborole–Sugar Interactions with Tunable Mechanical Properties. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.C.; Tao, L.; Hsieh, F.Y.; Wei, Y.; Chiu, I.M.; Hsu, S.H. An Injectable, Self-Healing Hydrogel to Repair the Central Nervous System. Advanced Materials 2015, 27, 3518–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Tan, M.L.; Taheri, M.; Yan, Q.; Tsuzuki, T.; Gardiner, M.G.; Diggle, B.; Connal, L.A. Strong, Self-Healable, and Recyclable Visible-Light-Responsive Hydrogel Actuators. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2020, 59, 7049–7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavahir, S.; Sobolčiak, P.; Krupa, I.; Han, D.S.; Tkac, J.; Kasak, P. Ti3C2Tx MXene-Based Light-Responsive Hydrogel Composite for Bendable Bilayer Photoactuator. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Li, B.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, G.; Pu, S.; Feng, Y.; Jia, D.; Zhou, Y. PH-Responsive UV Crosslinkable Chitosan Hydrogel via “Thiol-Ene” Click Chemistry for Active Modulating Opposite Drug Release Behaviors. Carbohydr Polym 2021, 251, 117101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, P.; Mao, G.; Yin, T.; Zhong, D.; Yiming, B.; Hu, X.; Jia, Z.; Nian, G.; Qu, S.; et al. Dual PH-Responsive Hydrogel Actuator for Lipophilic Drug Delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 12010–12017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, L.; Liu, A.; He, S.; Shao, W. Ultrafast Thermo-Responsive Bilayer Hydrogel Actuator Assisted by Hydrogel Microspheres. Sens Actuators B Chem 2022, 357, 131434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yang, Y.; Peng, H.; Whittaker, A.K.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Z. Cellulose Nanocrystals Reinforced Highly Stretchable Thermal-Sensitive Hydrogel with Ultra-High Drug Loading. Carbohydr Polym 2021, 266, 118122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Fan, L.; Yan, S.; Li, F.; Li, H.; Tang, J. Tough and Electro-Responsive Hydrogel Actuators with Bidirectional Bending Behavior. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 2231–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Wang, Q.; Xie, J.; Li, B.; Lin, X.; Hui, S. Novel Electrically-Conductive Electro-Responsive Hydrogels for Smart Actuators with a Carbon-Nanotube-Enriched Three-Dimensional Conductive Network and a Physical-Phase-Type Three-Dimensional Interpenetrating Network. J Mater Chem C Mater 2020, 8, 4192–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjua, A.C.; Alves, V.D.; Crespo, J.G.; Portugal, C.A.M. Magnetic Responsive PVA Hydrogels for Remote Modulation of Protein Sorption. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11, 21239–21249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Shang, L.; Su, Z. Programmable Anisotropic Hydrogels with Localized Photothermal/Magnetic Responsive Properties. Advanced Science 2022, 9, 2202173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Rong, L.; Wang, B.; Xie, R.; Sui, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, Y.; Mao, Z. Facile Fabrication of Redox/PH Dual Stimuli Responsive Cellulose Hydrogel. Carbohydr Polym 2017, 176, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, R.D.; Jha, P.K. Mathematical Models for Controlled Drug Release Through PH-Responsive Polymeric Hydrogels. J Pharm Sci 2017, 106, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta Ramos, M.L.; González, J.A.; Fabian, L.; Pérez, C.J.; Villanueva, M.E. Sustainable and Smart Keratin Hydrogel with PH-Sensitive Swelling and Enhanced Mechanical Properties. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017, 78, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.R.; Tarighatjoo, M.; Nikravesh, G. 1,3,5-Triazine-2,4,6-Tribenzaldehyde Derivative as a New Crosslinking Agent for Synthesis of PH-Thermo Dual Responsive Chitosan Hydrogels and Their Nanocomposites: Swelling Properties and Drug Release Behavior. Int J Biol Macromol 2017, 105, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momeni, F.; Hassani, M.Mehdi; N, S.; Liu, X.; Ni, J. A Review of 4D Printing. Mater Des 2017, 122, 42–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbits: The Emergence of “4D Printing” - Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0,5&cluster=9787433058056401908 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Choi, J.; Reddy, D.A.; Islam, M.J.; Seo, B.; Joo, S.H.; Kim, T.K. Green Synthesis of the Reduced Graphene Oxide–CuI Quasi-Shell–Core Nanocomposite: A Highly Efficient and Stable Solar-Light-Induced Catalyst for Organic Dye Degradation in Water. Appl Surf Sci 2015, 358, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Qi, H.J.; Dunn, M.L. Active Materials by Four-Dimension Printing. Appl Phys Lett 2013, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, E. 4D Printing: Dawn of an Emerging Technology Cycle. Assembly Automation 2014, 34, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, Z.X.; Teoh, J.E.M.; Liu, Y.; Chua, C.K.; Yang, S.; An, J.; Leong, K.F.; Yeong, W.Y. 3D Printing of Smart Materials: A Review on Recent Progresses in 4D Printing. Virtual Phys Prototyp 2015, 10, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, S.; Ke, Y.; Ding, L.; Zeng, X.; Magdassi, S.; Long, Y. 4D Printed Hydrogels: Fabrication, Materials, and Applications. Adv Mater Technol 2020, 5, 2000034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3D Printing Is So 2013 — Introducing 4D Printing! - Brit + Co. Available online: https://www.brit.co/4d-printing/ (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jin, D.; Zhang, C.; Sun, R.; Li, Z.; Hu, K.; Ni, J.; Cai, Z.; Pan, D.; et al. Botanical-Inspired 4D Printing of Hydrogel at the Microscale. Adv Funct Mater 2020, 30, 1907377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Ji, X.; Gong, J.; Hu, Y.; Wu, W.; Wang, X.; Peng, H.Q.; Kwok, R.T.K.; Lam, J.W.Y.; et al. Bioinspired Simultaneous Changes in Fluorescence Color, Brightness, and Shape of Hydrogels Enabled by AIEgens. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 1906493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, C.A.; Hippler, M.; Münchinger, A.; Bastmeyer, M.; Barner-Kowollik, C.; Wegener, M.; Blasco, E. 4D Printing at the Microscale. Adv Funct Mater 2020, 30, 1907615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Seo, Y.B.; Yeon, Y.K.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, H.S.; Sultan, M.T.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, O.J.; Hong, H.; et al. 4D-Bioprinted Silk Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2020, 260, 120281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narupai, B.; Smith, P.T.; Nelson, A. 4D Printing of Multi-Stimuli Responsive Protein-Based Hydrogels for Autonomous Shape Transformations. Adv Funct Mater 2021, 31, 2011012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koetting, M.C.; Peters, J.T.; Steichen, S.D.; Peppas, N.A. Stimulus-Responsive Hydrogels: Theory, Modern Advances, and Applications. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 2015, 93, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, F.; Othman, M.B.H.; Javed, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Akil, H.M. Classification, Processing and Application of Hydrogels: A Review. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2015, 57, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Yao, F.; Li, J. Nanocomposite Hydrogel-Based Strain and Pressure Sensors: A Review. J Mater Chem A Mater 2020, 8, 18605–18623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendi, A.; Hassan, M.U.; Elsherif, M.; Alqattan, B.; Park, S.; Yetisen, A.K.; Butt, H. Healthcare Applications of PH-Sensitive Hydrogel-Based Devices: A Review. Int J Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 3887–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasution, H.; Harahap, H.; Dalimunthe, N.F.; Ginting, M.H.S.; Jaafar, M.; Tan, O.O.H.; Aruan, H.K.; Herfananda, A.L. Hydrogel and Effects of Crosslinking Agent on Cellulose-Based Hydrogels: A Review. Gels 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champeau, M.; Heinze, D.A.; Viana, T.N.; de Souza, E.R.; Chinellato, A.C.; Titotto, S. 4D Printing of Hydrogels: A Review. Adv Funct Mater 2020, 30, 1910606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsak, I.S.; Morozov, Y.M.; Protsak, I.S.; Morozov, Y.M. Fundamentals and Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels and Their Applications: A Review. Gels 2025, Vol. 11, 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, B.M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B.M. Current Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels as Smart Drug Delivery Carriers. Gels 2023, Vol. 9, 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, A.; Hussain, C.M.; Agrawal, A.; Hussain, C.M. 3D-Printed Hydrogel for Diverse Applications: A Review. Gels 2023, Vol. 9, 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.J.; Park, T.G. Self-Assembled and Nanostructured Hydrogels for Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering. Nano Today 2009, 4, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, B. V.; Khurshid, S.S.; Fisher, O.Z.; Khademhosseini, A.; Peppas, N.A. Hydrogels in Regenerative Medicine. Advanced Materials 2009, 21, 3307–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Torres, M.; Romero-Fierro, D.; Arcentales-Vera, B.; Palomino, K.; Magaña, H.; Bucio, E. Hydrogels Classification According to the Physical or Chemical Interactions and as Stimuli-Sensitive Materials. Gels 2021, Vol. 7 7, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Su, J. Fabrication of Physical and Chemical Crosslinked Hydrogels for Bone Tissue Engineering. Bioact Mater 2022, 12, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebers, L.; Reichsöllner, R.; Regett, S.; Tovar, G.E.M.; Borchers, K.; Baudis, S.; Southan, A. Differentiation of Physical and Chemical Cross-Linking in Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogels. Scientific Reports 2021, 11:1 2021(11), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; West, J.L. Photopolymerizable Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 4307–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrbar, M.; Rizzi, S.C.; Schoenmakers, R.G.; San Miguel, B.; Hubbell, J.A.; Weber, F.E.; Lutoff, M.P. Biomolecular Hydrogels Formed and Degraded via Site-Specific Enzymatic Reactions. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 3000–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.Y.; Tsai, Y.T.; Wu, C.Y.; Tu, L.H.; Bai, M.Y.; Yeh, Y.C. The Role of Aldehyde-Functionalized Crosslinkers on the Property of Chitosan Hydrogels. Macromol Biosci 2022, 22, 2100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Jin, X.; Cong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fu, J. Degradable Natural Polymer Hydrogels for Articular Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2013, 88, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, R.; Gupta, K. A Review: Tailor-Made Hydrogel Structures (Classifications and Synthesis Parameters). Polym Plast Technol Eng 2016, 55, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Sharma, M.; Devi, M. Hydrogels: An Overview of Its Classifications, Properties, and Applications. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2023, 147, 106145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, B.; Kargar, P.G.; Ashrafi, S.S.; Ghani, M.; Maleki, B.; Kargar, P.G.; Ashrafi, S.S.; Ghani, M. Perspective Chapter: Introduction to Hydrogels – Definition, Classifications, Applications and Methods of Preparation. Ionic Liquids - Recent Advances [Working Title] 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohite, P.; Pharm. S.A.-Int.J.Adv.; 2017, undefined A Hydrogels: Methods of Preparation and Applications. In core.ac.uk.

- Ahmad, Z.; Salman, S.; Khan, S.A.; Amin, A.; Rahman, Z.U.; Al-Ghamdi, Y.O.; Akhtar, K.; Bakhsh, E.M.; Khan, S.B. Versatility of Hydrogels: From Synthetic Strategies, Classification, and Properties to Biomedical Applications. Gels 2022, Vol. 8(Page 167 2022, 8), 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.S. Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2012, 64, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P. Synthesis and Characterization of Polyionic Hydrogels. Theses and Dissertations 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizawa, T.; Taketa, H.; Maruta, M.; Ishido, T.; Gotoh, T.; Sakohara, S. Synthesis of Porous Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Gel Beads by Sedimentation Polymerization and Their Morphology. J Appl Polym Sci 2007, 104, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.K.; Hasnain, M.S.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Drug Delivery Using Interpenetrating Polymeric Networks of Natural Polymers: A Recent Update. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2021, 66, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Thakur, V.K.; Arotiba, O.A. History, Classification, Properties and Application of Hydrogels: An Overview 2018, 29–50. [CrossRef]

- Sperling, L.H. Interpenetrating Polymer Networks: An Overview 1994, 3–38. [CrossRef]

- Myung, D.; Waters, D.; Wiseman, M.; Duhamei, P.E.; Noolandi, J.; Ta, C.N.; Frank, C.W. Progress in the Development of Interpenetrating Polymer Network Hydrogels. Polym Adv Technol 2008, 19, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Singh, S.; Dhyani Assistant Professor, A.; Shailesh Kumar Singh, C.; Dhyani, A.; Juyal, D. Hydrogel: Preparation, Characterization and Applications. The Pharma Innovation Journal 2017, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Qian, C.; Yuan, W. Self-Healing, Anti-Freezing, Adhesive and Remoldable Hydrogel Sensor with Ion-Liquid Metal Dual Conductivity for Biomimetic Skin. Compos Sci Technol 2021, 203, 108608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadian, H.; Maleki, H.; Allahyari, Z.; Jaymand, M. Natural Polymers-Based Light-Induced Hydrogels: Promising Biomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Coord Chem Rev 2020, 420, 213432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourjavadi, A.; Heydarpour, R.; Tehrani, Z.M. Multi-Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels and Their Medical Applications. New Journal of Chemistry 2021, 45, 15705–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Dong, X.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lu, S.; Wang, Q.; Liao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H. Multi-Responsive Lanthanide-Based Hydrogel with Encryption, Naked Eye Sensing, Shape Memory, Self-Healing, and Antibacterial Activity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 28539–28549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.J.; Huang, L.M.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T. 4D Printing: History and Recent Progress. Chinese Journal of Polymer Science (English Edition) 2018, 36, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, D.J.; Moore, J.S.; Bauer, J.M.; Yu, Q.; Liu, R.H.; Devadoss, C.; Jo, B.H. Functional Hydrogel Structures for Autonomous Flow Control inside Microfluidic Channels. Nature 2000, 404 404, 6778 2000 588–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, A.; Kuckling, D.; Howitz, S.; Gehring, T.; Arndt, K.F. Electronically Controllable Microvalves Based on Smart Hydrogels: Magnitudes and Potential Applications. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems 2003, 12, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, I. Stimuli-Controlled Hydrogels and Their Applications. Acc Chem Res 2017, 50, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.K.; Kasi, R.M.; Kim, S.C.; Sharma, N.; Zhou, Y. Stimuli-Responsive Polymer Gels. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabha Raju, M.; Mohana Raju, K. Synthesis and Water Absorbency of Superabsorbent Copolymers. International Journal of Polymer Analysis and Characterization 2003, 8, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvekar, A.V.; Huang, W.M.; Xiao, R.; Wong, Y.S.; Venkatraman, S.S.; Tay, K.H.; Shen, Z.X. Water-Responsive Shape Recovery Induced Buckling in Biodegradable Photo-Cross-Linked Poly(Ethylene Glycol) (PEG) Hydrogel. Acc Chem Res 2017, 50, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Cui, Z.; Bao, L.; Xia, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, X. High Performance and Multifunction Moisture-Driven Yin–Yang-Interface Actuators Derived from Polyacrylamide Hydrogel. Small 2023, 19, 2303228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Yin, C.; Hong, S.; Chen, H.; Shi, Q.; Wang, J.; Lu, X.; Zhou, N. Lanthanide-Ion-Coordinated Supramolecular Hydrogel Inks for 3D Printed Full-Color Luminescence and Opacity-Tuning Soft Actuators. Chemistry of Materials 2020, 32, 8868–8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Huang, H.; Yu, J.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y. Highly Stretchable and Strong Poly (Vinyl Alcohol)-Based Hydrogel for Reprogrammable Actuator Applications. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 454, 140054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Gao, X.; Ullah, M.W.; Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Yang, G. Electroconductive Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels. Biomaterials 2016, 111, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Peng, Q.; Thundat, T.; Zeng, H. Stretchable, Injectable, and Self-Healing Conductive Hydrogel Enabled by Multiple Hydrogen Bonding toward Wearable Electronics. Chemistry of Materials 2019, 31, 4553–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, B.; Ren, X.; Long, Y.; Fang, L.; Ou, R.; Liu, T.; Wang, Q. Highly Compressible Hydrogel Sensors with Synergistic Long-Lasting Moisture, Extreme Temperature Tolerance and Strain-Sensitivity Properties. Mater Chem Front 2020, 4, 3319–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, X.; Wu, J. Conductive Hydrogel- And Organohydrogel-Based Stretchable Sensors. In ACS Appl Mater Interfaces; GIF, 2021; Volume 13, pp. 2128–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Pi, M.; Zhang, X.; Yan, B.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.; Ran, R. High Strength, Antifreeze, and Moisturizing Conductive Hydrogel for Human-motion Detection. Polymer (Guildf) 2020, 196, 122469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nahari, B.B.M.A.; Zarbane, K.; Beidouri, Z. The Use of Moisture-Responsive Materials in 4D Printing. Journal of Achievements in Materials and Manufacturing Engineering 2023, 119, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capanema, N.S.V.; Mansur, A.A.P.; Carvalho, I.C.; Carvalho, S.M.; Mansur, H.S. Bioengineered Water-Responsive Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Hydrogel Hybrids for Wound Dressing and Skin Tissue Engineering Applications. Gels 2023, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Jia, S.; Guan, J.; Ma, C.; Shao, Z. Robust and Highly Sensitive Cellulose Nanofiber-Based Humidity Actuators. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 54417–54427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sydney Gladman, A.; Matsumoto, E.A.; Nuzzo, R.G.; Mahadevan, L.; Lewis, J.A. Biomimetic 4D Printing. Nat Mater 2016, 15, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, W.; Li, B.; Dong, J.; Gao, G.; Jiang, Z. Double-Layer Temperature-Sensitive Hydrogel Fabricated by 4D Printing with Fast Shape Deformation. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2022, 648, 129307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.; Wu, D.; Wu, S.; Ma, Y.; Alsaid, Y.; He, X. 4D Printable Tough and Thermoresponsive Hydrogels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 12689–12697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, T.; Okay, O. 4D Printing of Body Temperature-Responsive Hydrogels Based on Poly(Acrylic Acid) with Shape-Memory and Self-Healing Abilities. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2023, 6, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossier, T.; Habib, M.; Benkhaled, B.T.; Volpi, G.; Lapinte, V.; Blanquer, S. 4D Printing of Hydrogels Based on Poly(Oxazoline) and Poly(Acrylamide) Copolymers by Stereolithography. Mater Adv 2024, 5, 2750–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narupai, B.; Smith, P.T.; Nelson, A. 4D Printing of Multi-Stimuli Responsive Protein-Based Hydrogels for Autonomous Shape Transformations. Adv Funct Mater 2021, 31, 2011012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podstawczyk, D.; Nizioł, M.; Szymczyk-Ziółkowska, P.; Fiedot-Toboła, M.; Podstawczyk, D.; Nizioł, M.; Szymczyk-Ziółkowska, P.; Fiedot-Toboła, M. Development of Thermoinks for 4D Direct Printing of Temperature-Induced Self-Rolling Hydrogel Actuators. Adv Funct Mater 2021, 31, 2009664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, T.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z. A Bioinspired 4D Printed Hydrogel Capsule for Smart Controlled Drug Release. Mater Today Chem 2022, 24, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelluau, T.; Brossier, T.; Habib, M.; Sene, S.; Félix, G.; Larionova, J.; Blanquer, S.; Guari, Y. 4D Printing Nanocomposite Hydrogel Based on PNIPAM and Prussian Blue Nanoparticles Using Stereolithography. Macromol Mater Eng 2024, 309, 2300305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Huang, Y.; Lv, F.; Liu, L.; Gu, Q.; Wang, S. Biomimetic 4D-Printed Breathing Hydrogel Actuators by Nanothylakoid and Thermoresponsive Polymer Networks. Adv Funct Mater 2021, 31, 2105544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.; Sahu, S.; Mitra, S.; Niranjan, R.; Priyadarshini, R.; Yadav, R.; Lochab, B. Nanocellulose-Reinforced 4D Printed Hydrogels: Thermoresponsive Shape Morphing and Drug Release. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2024, 6, 1348–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.; Guo, Y.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, S. 4D Printing of Core–Shell Hydrogel Capsules for Smart Controlled Drug Release. Biodes Manuf 2022, 5, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Shen, P.; Li Tan, M.; Yan, Q.; Viktorova, J.; Cementon, C.; Peng, X.; Xiao, P.; Connal, L.A. 3D and 4D Printable Dual Cross-Linked Polymers with High Strength and Humidity-Triggered Reversible Actuation. Mater Adv 2021, 2, 5124–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahouni, Y.; Cheng, T.; Lajewski, S.; Benz, J.; Bonten, C.; Wood, D.; Menges, A. Codesign of Biobased Cellulose-Filled Filaments and Mesostructures for 4D Printing Humidity Responsive Smart Structures. 3D Print Addit Manuf 2023, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, S.; Shu Hieng Tie, B.; Keane, G.; Geever, L.M. Strategies for Developing Shape-Shifting Behaviours and Potential Applications of Poly (N-Vinyl Caprolactam) Hydrogels. Polymers 2023, Vol. 15 15, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Tao, L.; Gong, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, Q.; Ju, J.; Zhang, Y. 4D Printing of a Sodium Alginate Hydrogel with Step-Wise Shape Deformation Based on Variation of Crosslinking Density. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2021, 3, 6167–6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parimita, S.; Kumar, A.; Krishnaswamy, H.; Ghosh, P. Solvent Triggered Shape Morphism of 4D Printed Hydrogels. J Manuf Process 2023, 85, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanjul-Mosteirín, N.; Aguirresarobe, R.; Sadaba, N.; Larrañaga, A.; Marin, E.; Martin, J.; Ramos-Gomez, N.; Arno, M.C.; Sardon, H.; Dove, A.P. Crystallization-Induced Gelling as a Method to 4D Print Low-Water-Content Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Hydrogels. Chemistry of Materials 2021, 33, 7194–7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Li, B.; Liu, Q.; Ren, L.; Song, Z.; Zhou, X.; Gao, P. 4D Printing Dual Stimuli-Responsive Bilayer Structure Toward Multiple Shape-Shifting. Front Mater 2021, 8, 655160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, P.; Mao, G.; Yin, T.; Zhong, D.; Yiming, B.; Hu, X.; Jia, Z.; Nian, G.; Qu, S.; et al. Dual PH-Responsive Hydrogel Actuator for Lipophilic Drug Delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 12010–12017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simińska-Stanny, J.; Nizioł, M.; Szymczyk-Ziółkowska, P.; Brożyna, M.; Junka, A.; Shavandi, A.; Podstawczyk, D. 4D Printing of Patterned Multimaterial Magnetic Hydrogel Actuators. Addit Manuf 2022, 49, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, H.; Chen, G.; Zheng, J.; Wang, W.; Ren, J.; Zhu, C.; Yang, Y.; Cong, Y.; Fu, J. 4D Printing of Biomimetic Anisotropic Self-Sensing Hydrogel Actuators. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 473, 145444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Chen, J.R.; Su, C.K. 4D-Printed PH Sensing Claw. Anal Chim Acta 2022, 1204, 339733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiguchi, A.; Zhang, H.; Schweizerhof, S.; Schulte, M.F.; Mourran, A.; Möller, M. 4D Printing of a Light-Driven Soft Actuator with Programmed Printing Density. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 12176–12185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yuan, C.; Cheng, J.; He, X.; Ye, H.; Jian, B.; Li, H.; Bai, J.; Ge, Q. Direct 4D Printing of Ceramics Driven by Hydrogel Dehydration. Nature Communications 2024, 15 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.; Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Jiao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, F.; Gao, H.; Deng, L.; Xiong, W. Femtosecond Laser 4D Printing of Light-Driven Intelligent Micromachines. Adv Funct Mater 2023, 33, 2211473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Qu, J.; Dong, J.; Guo, Y.; Wu, X.; Fang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wei, Y.; Li, Z. 4D Printing of Magnetic Smart Structures Based on Light-Cured Magnetic Hydrogel. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 494, 152992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Boon Chng, C.; Zheng, H.; See Wu, M.; Jorge Da Silva Bartolo, P.; Jerry Qi, H.; Jun Tan, Y.; Zhou, K.; Li, H.; Zheng, H.; et al. Self-Healable and 4D Printable Hydrogel for Stretchable Electronics. Advanced Science 2024, 11, 2305702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Shi, G.; He, Y.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, X.; Fu, P.; Liu, M.; Qiao, X.; et al. High Colloidal Stable Carbon Dots Armored Liquid Metal Nano-Droplets for Versatile 3D/4D Printing Through Digital Light Processing (DLP). Energy & Environmental Materials 2024, 7, e12609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Jang, S.; Kuss, M.A.; Alimi, O.A.; Liu, B.; Palik, J.; Tan, L.; Krishnan, M.A.; Jin, Y.; Yu, C.; et al. Digital Light Processing 4D Printing of Poloxamer Micelles for Facile Fabrication of Multifunctional Biocompatible Hydrogels as Tailored Wearable Sensors. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 7580–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratri, M.C.; Suh, J.; Ryu, J.; Chung, B.G.; Shin, K. Formulation of Three-Dimensional, Photo-Responsive Printing Ink: Gold Nanorod-Hydrogel Nanocomposites and Their Four-Dimensional Structures That Respond Quickly to Stimuli. J Appl Polym Sci 2023, 140, e53799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antezana, P.E.; Municoy, S.; Ostapchuk, G.; Catalano, P.N.; Hardy, J.G.; Evelson, P.A.; Orive, G.; Desimone, M.F. 4D Printing: The Development of Responsive Materials Using 3D-Printing Technology. Pharmaceutics 2023, Vol. 15 15, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, V.; Singh, R.; Kumar, R.; Gehlot, A. 4D Printing of Thermoresponsive Materials: A State-of-the-Art Review and Prospective Applications. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing 2023, 17, 2075–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Q.Q.; Liow, S.S.; Ye, E.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Loh, X.J. Biodegradable Thermogelling Polymers: Working Towards Clinical Applications. Adv Healthc Mater 2014, 3, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xue, K.; Loh, X.J. Thermo-Responsive Hydrogels: From Recent Progress to Biomedical Applications. Gels 2021, Vol. 7(Page 77 2021, 7), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takezawa, T.; Mori, Y.; Yonaha, T.; Yoshizato, K. Characterization of Morphology and Cellular Metabolism during the Spheroid Formation by Fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res 1993, 208, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Weber, C.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R. Thermoresponsive Polymers with Lower Critical Solution Temperature: From Fundamental Aspects and Measuring Techniques to Recommended Turbidimetry Conditions. Mater Horiz 2017, 4, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Ajazuddin; Khan, J.; Saraf, S.; Saraf, S. Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)–Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm) Based Thermosensitive Injectable Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2014, 88, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Srivastava, A.; Galaev, I.Y.; Mattiasson, B. Smart Polymers: Physical Forms and Bioengineering Applications. Prog Polym Sci 2007, 32, 1205–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.J.; An, N.; Yang, J.H.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.M. Tough Al-Alginate/Poly(N -Isopropylacrylamide) Hydrogel with Tunable LCST for Soft Robotics. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015, 7, 1758–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratte, T.; Geiger, S.; Colombo, F.; Mishra, A.; Taale, M.; Hsu, L.Y.; Blasco, E.; Selhuber-Unkel, C. Increasing the Efficiency of Thermoresponsive Actuation at the Microscale by Direct Laser Writing of PNIPAM. Adv Mater Technol 2023, 8, 2200714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, L.; Zhao, B. Multi-Thermo Responsive Double Network Composite Hydrogel for 3D Printing Medical Hydrogel Mask. J Colloid Interface Sci 2023, 638, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Larrea, N.; Wustoni, S.; Peñas, M.I.; Uribe, J.; Dominguez-Alfaro, A.; Gallastegui, A.; Inal, S.; Mecerreyes, D. PNIPAM/PEDOT:PSS Hydrogels for Multifunctional Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Adv Funct Mater 2024, 2403708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, F.; Wu, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhang, L. Construction of Ionic Thermo-Responsive PNIPAM/γ-PGA/PEG Hydrogel as a Draw Agent for Enhanced Forward-Osmosis Desalination. Desalination 2020, 495, 114667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, X. 3D Printed Thermo-Responsive Hydrogel Evaporator with Enhanced Water Transport for Efficient Solar Steam Generation. Solar Energy 2024, 273, 112507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.; Arbab, A.; Khan, S.; Fatima, H.; Bibi, I.; Chowdhry, N.P.; Ansari, A.Q.; Ursani, A.A.; Kumar, S.; Hussain, J.; et al. Recent Progress in Thermosensitive Hydrogels and Their Applications in Drug Delivery Area. MedComm - Biomaterials and Applications 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, P.; Biofabrication, B.K.-. 2019, undefined Review of Alginate-Based Hydrogel Bioprinting for Application in Tissue Engineering.

- Han, X.; Dong, Z.; Fan, M.; Liu, Y.; li, J.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Li, B.; Zhang, S. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 12/2012. Macromol Rapid Commun 2012, 33, 1017–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, G.; Tuncer, C.; Bütün, V. PH-Responsive Polymers. Polym Chem 2016, 8, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Tan, Y.; Yue, Q.; Meng, F. Physically Cross-Linked PH-Responsive Chitosan-Based Hydrogels with Enhanced Mechanical Performance for Controlled Drug Delivery. RSC Adv 2016, 6, 106035–106045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Liu, T.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Guang, N. Temperature and PH Responsive Hydrogels Based on Polyethylene Glycol Analogues and Poly(Methacrylic Acid) via Click Chemistry. Polym Int 2015, 64, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Arotiba, O.A. Synthesis, Swelling and Adsorption Studies of a PH-Responsive Sodium Alginate–Poly(Acrylic Acid) Superabsorbent Hydrogel. Polymer Bulletin 2018, 75, 4587–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hu, J.; Zhang, R.; Yan, C.; Cui, L.; Zhu, J. A PH-Responsive Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Chitosan Hydrogel for Adsorption and Desorption of Anionic and Cationic Dyes. Cellulose 2021, 28, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhand, C.; Das, M.; Datta, M.; Malhotra, B.D. Recent Advances in Polyaniline Based Biosensors. Biosens Bioelectron 2011, 26, 2811–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.; Jeong, H.Y.; Kwon, G.; Kim, D.; Lee, C.; You, J. PH-Responsive Polyaniline/Polyethylene Glycol Composite Arrays for Colorimetric Sensor Application. Sens Actuators B Chem 2020, 305, 127447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Cohn, D. Temperature and PH Responsive 3D Printed Scaffolds. J Mater Chem B 2017, 5, 9514–9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Gallardo, A.; López, D.; Elvira, C.; Azzahti, A.; Lopez-Martinez, E.; Cortajarena, A.L.; González-Henríquez, C.M.; Sarabia-Vallejos, M.A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J. Smart PH-Responsive Antimicrobial Hydrogel Scaffolds Prepared by Additive Manufacturing. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2018, 1, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Sun, F. Calcium-Responsive Hydrogels Enabled by Inducible Protein–Protein Interactions. Polym Chem 2020, 11, 4973–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, X.; Ma, Q.; Xu, Y.; Yang, M.; Wu, G.; Sun, P. High-Performance Ionic Conductive Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Hydrogels for Flexible Strain Sensors Based on a Universal Soaking Strategy. Mater Chem Front 2021, 5, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, H.; Laycock, B.; Strounina, E.; Seviour, T.; Oehmen, A.; Pikaar, I. Modified Poly(Acrylic Acid)-Based Hydrogels for Enhanced Mainstream Removal of Ammonium from Domestic Wastewater. Environ Sci Technol 2020, 54, 9573–9583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Shi, Y. Anisotropic Single-Domain Hydrogel with Stimulus Response to Temperature and Ionic Strength. Macromolecules 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jiang, R.; Wu, J.; Song, J.; Bai, H.; Li, B.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T. Ultrafast Digital Printing toward 4D Shape Changing Materials. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1605390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, A.; Maxson, R.; Stoychev, G.; Gomillion, C.T.; Ionov, L. 4D Biofabrication Using Shape-Morphing Hydrogels. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1703443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza, R.D.; dos Santos, C.C.; Pinto, G.C.; Lucena, G.N.; Junior, M.J.; Marques, R.F.C. Multifunctional Redox and Temperature-Sensitive Drug Delivery Devices. Biomedical Materials & Devices 2023, 2023 2 2, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddimath, S.; Payamalle, S.; Channabasavana Hundi Puttaningaiah, K.P.; Hur, J. Recent Advances in PH and Redox Responsive Polymer Nanocomposites for Cancer Therapy. Journal of Composites Science 2024, Vol. 8 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Sekhar, K.P.C.; Zhang, P.; Cui, J. Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Injectable Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Biomater Sci 2024, 12, 5468–5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinbasak, I.; Sanyal, R.; Sanyal, A. Best of Both Worlds: Diels–Alder Chemistry towards Fabrication of Redox-Responsive Degradable Hydrogels for Protein Release. RSC Adv 2016, 6, 74757–74764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodeir, M.; Antoun, S.; van Ruymbeke, E.; Gohy, J.F. Temperature and Redox-Responsive Hydrogels Based on Nitroxide Radicals and Oligoethyleneglycol Methacrylate. Macromol Chem Phys 2020, 221, 1900550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, T.R.; Kohane, D.S. Hydrogels in Drug Delivery: Progress and Challenges. Polymer (Guildf) 2008, 49, 1993–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymer Gels; 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.H.; Ariga, K. Redox-Active Polymers for Energy Storage Nanoarchitectonics. Joule 2017, 1, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, Y.; Pan, L.; Shi, Y.; Yu, G. Rational Design and Applications of Conducting Polymer Hydrogels as Electrochemical Biosensors. J Mater Chem B 2015, 3, 2920–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocak, G.; Tuncer, C.; Bütün, V. PH-Responsive Polymers. Polym Chem 2016, 8, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Vermani, K.; Garg, S. Hydrogels: From Controlled Release to PH-Responsive Drug Delivery. Drug Discov Today 2002, 7, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Yahya, R.; Hassan, A.; Yar, M.; Azzahari, A.D.; Selvanathan, V.; Sonsudin, F.; Abouloula, C.N. Erratum: PH Sensitive Hydrogels in Drug Delivery: Brief History, Properties, Swelling, and Release Mechanism, Material Selection and Applications. Polymers 2017, 9, 137. Polymers 2017, Vol. 9(Page 225 2017, 9), 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Kumar, A.; Tan, A.; Jin, S.; Mozhi, A.; Liang, X.J. PH-Sensitive Nano-Systems for Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Biotechnol Adv 2014, 32, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mooney, D.J. Designing Hydrogels for Controlled Drug Delivery. Nat Rev Mater 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, A.; Meng, Q.; Shi, G.; Arabi, S.; Ma, J.; Zhao, N.; Kuan, H.C. Electrically Conductive, Mechanically Robust, PH-Sensitive Graphene/Polymer Composite Hydrogels. Compos Sci Technol 2016, 127, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Liu, J.; Min, X.; Cao, T.; Fan, X. Smart Composite Hydrogels with PH-Responsiveness and Electrical Conductivity for Flexible Sensors and Logic Gates. Polymers 2019, Vol. 11 11, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.S. Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2012, 64, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mooney, D.J. Designing Hydrogels for Controlled Drug Delivery. Nature Reviews Materials 2016, 12 2016(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Choi, M.Y.; Choi, J.; Na, J.H.; Kim, S.Y. Design of an Electro-Stimulated Hydrogel Actuator System with Fast Flexible Folding Deformation under a Low Electric Field. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 15633–15646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Farino, C.; Yang, C.; Scott, T.; Browe, D.; Choi, W.; Freeman, J.W.; Lee, H. Soft Robotic Manipulation and Locomotion with a 3D Printed Electroactive Hydrogel. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 17512–17518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podstawczyk, D.; Nizioł, M.; Szymczyk, P.; Wiśniewski, P.; Guiseppi-Elie, A. 3D Printed Stimuli-Responsive Magnetic Nanoparticle Embedded Alginate-Methylcellulose Hydrogel Actuators. Addit Manuf 2020, 34, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, D.; Liu, B.; Nian, G.; Li, X.; Yin, J.; Qu, S.; Yang, W. 3D Printing of Multifunctional Hydrogels. Adv Funct Mater 2019, 29, 1900971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Park, S. 4D Printed Untethered Milli-Gripper Fabricated Using a Biodegradable and Biocompatible Electro- and Magneto-Active Hydrogel. Sens Actuators B Chem 2023, 384, 133654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, Z.; Yu, H.; Meng, D.; Zhu, L.; Li, H. Direct 3D Printing of Triple-Responsive Nanocomposite Hydrogel Microneedles for Controllable Drug Delivery. J Colloid Interface Sci 2024, 670, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zari, E.; Grillo, D.; Tan, Z.; Swiatek, N.; Linfoot, J.D.; Borvorntanajanya, K.; Nasca, L.; Pierro, E.; Florea, L.; Dini, D.; et al. A Reinforced Light-Responsive Hydrogel for Soft Robotics Actuation. 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Soft Robotics RoboSoft, 2024 2024; pp. 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Ma, C.; Chen, L.; Sun, Y.; Wei, X.; Ma, C.; Zhao, H.; Yang, X.; Ma, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. A Tissue Paper/Hydrogel Composite Light-Responsive Biomimetic Actuator Fabricated by In Situ Polymerization. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuksenok, O.; Balazs, A.C. Stimuli-Responsive Behavior of Composites Integrating Thermo-Responsive Gels with Photo-Responsive Fibers. Mater Horiz 2015, 3, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirani, N.; Yahia, H.; Gritsch, L.; Motta, F.L.; Chirani, S.; Faré, S. History and Applications of Hydrogels. JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES 2021, 04, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, W.U.; Asim, M.; Hussain, S.; Khan, S.A.; Khan, S.B. Hydrogel: A Promising Material in Pharmaceutics. Curr Pharm Des 2020, 26, 5892–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolfagharian, A.; Denk, M.; Bodaghi, M.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Kaynak, A. Topology-Optimized 4D Printing of a Soft Actuator. Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica 2020, 33, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takishima, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Khosla, A.; Kawakami, M.; Furukawa, H. Fully 3D-Printed Hydrogel Actuator for Jellyfish Soft Robots. ECS Journal of Solid State Science and Technology 2021, 10, 037002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Liang, Y.; Ren, L.; Qiu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, L. Study on Temperature and Near-Infrared Driving Characteristics of Hydrogel Actuator Fabricated via Molding and 3D Printing. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2018, 78, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Williamson, A.S.; Sukhnandan, R.; Majidi, C.; Yao, L.; Feinberg, A.W.; Webster-Wood, V.A.; Sun, W.; Williamson, A.S.; Sukhnandan, R.; et al. Biodegradable, Sustainable Hydrogel Actuators with Shape and Stiffness Morphing Capabilities via Embedded 3D Printing. Adv Funct Mater 2023, 33, 2303659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumley, E.H.; Preninger, D.; Shomron, A.S.; Rothemund, P.; Hartmann, F.; Baumgartner, M.; Kellaris, N.; Stojanovic, A.; Yoder, Z.; Karrer, B.; et al. Biodegradable Electrohydraulic Actuators for Sustainable Soft Robots. In Sci Adv; ZIP, 2023; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumley, E.H.; Preninger, D.; Shomron, A.S.; Rothemund, P.; Hartmann, F.; Baumgartner, M.; Kellaris, N.; Stojanovic, A.; Yoder, Z.; Karrer, B.; et al. Biodegradable Electrohydraulic Actuators for Sustainable Soft Robots. In Sci Adv; ZIP, 2023; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Shen, J.; Zhang, F.; He, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, B.; Niu, S.; Han, Z.; et al. Bioinspired Hydrogel Actuator for Soft Robotics: Opportunity and Challenges. Nano Today 2023, 49, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hua, M.; Wu, S.; Du, Y.; Pei, X.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, F.; He, X. Bioinspired High-Power-Density Strong Contractile Hydrogel by Programmable Elastic Recoil. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chu, H.; Yuan, H.; Li, D.; Deng, W.; Fu, Z.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Bioinspired Multifunctional Self-Sensing Actuated Gradient Hydrogel for Soft-Hard Robot Remote Interaction. Nanomicro Lett 2024, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Huang, H.; Liu, H.; Rehfeldt, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K. Multi-Responsive Bilayer Hydrogel Actuators with Programmable and Precisely Tunable Motions. Macromol Chem Phys 2019, 220, 1800562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yue, Y.; He, S.; Jiang, S.; Mei, C.; Xu, X.; Wu, Q.; Xiao, H.; Han, J. Nanocellulose-Mediated Bilayer Hydrogel Actuators with Thermo-Responsive, Shape Memory and Self-Sensing Performances. Carbohydr Polym 2024, 335, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, X.; Dong, B.; Sitti, M. In-Air Fast Response and High Speed Jumping and Rolling of a Light-Driven Hydrogel Actuator. Nat Commun 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Ding, L.; Wu, P. Cyano-Bridged Coordination Polymer Hydrogel-Derived Sn–Fe Binary Oxide Nanohybrids with Structural Diversity: From 3D, 2D, to 2D/1D and Enhanced Lithium-Storage Performance. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 9828–9836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Peng, L.; Yu, G. Nanostructured Conducting Polymer Hydrogels for Energy Storage Applications. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 12796–12806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ruan, Z.; Ma, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhi, C. Hydrogel Electrolytes for Flexible Aqueous Energy Storage Devices. Adv Funct Mater 2018, 28, 1804560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhai, S.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, J.; Yu, Z.; Pei, Z.; Liu, F.; Li, X.; Wei, L.; Chen, Y. Drying Graphene Hydrogel Fibers for Capacitive Energy Storage. Carbon N Y 2020, 164, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, J.; Zhou, W.; Han, X.; Yao, Y.; Wong, C.P. Realizing an All-Round Hydrogel Electrolyte toward Environmentally Adaptive Dendrite-Free Aqueous Zn–MnO2 Batteries. Advanced Materials 2021, 33, 2007559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Hong, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Jin, X.; Xiong, B.; Bai, S.; Zhi, C. Lean-Water Hydrogel Electrolyte for Zinc Ion Batteries. Nature Communications 2023, 14 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, F.; Cong, L.; Feng, W.; Wang, C.; Chu, F.; Nan, J.; Chen, R. Lignin-Containing Hydrogel Matrices with Enhanced Adhesion and Toughness for All-Hydrogel Supercapacitors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 450, 138025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Cao, L.; Lai, F.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Du, X.; Li, W.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, P. Double-Cross-Linked Polyaniline Hydrogel and Its Application in Supercapacitors. Ionics (Kiel) 2022, 28, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. hao; Du, X. sheng Self-Healable and Redox Active Hydrogel Obtained via Incorporation of Ferric Ion for Supercapacitor Applications. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 446, 137244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Meng, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, T.; Zhang, C. Recent Advances in Conductive Polymer Hydrogel Composites and Nanocomposites for Flexible Electrochemical Supercapacitors. Chemical Communications 2021, 58, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Jiang, C.; Sun, N.; Tan, D.; Li, Q.; Bi, S.; Song, J. Recent Progress in Multifunctional Hydrogel-Based Supercapacitors. Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices 2021, 6, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Chaudhary, J.; Kumar, V.; Thakur, V.K. Progress in Pectin Based Hydrogels for Water Purification: Trends and Challenges. J Environ Manage 2019, 238, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; de Vasconcelos, L.S.; Manohar, N.; Geng, J.; Johnston, K.P.; Yu, G. Highly Elastic Interconnected Porous Hydrogels through Self-Assembled Templating for Solar Water Purification. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2022, 61, e202114074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, N.; Wang, S.; Qiao, L.; Yu, L.; Murto, P.; Xu, X. Self-Repairing and Damage-Tolerant Hydrogels for Efficient Solar-Powered Water Purification and Desalination. Adv Funct Mater 2021, 31, 2104464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhao, F.; Zhou, X.; Shi, W.; Yu, G. Biomass-Derived Hybrid Hydrogel Evaporators for Cost-Effective Solar Water Purification. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 1907061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Peng, X.; Sun, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, H.; et al. Hydrogels for the Removal of the Methylene Blue Dye from Wastewater: A Review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2022, 4 20, 2665–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim Teik Zheng, A.; Phromsatit, T.; Boonyuen, S.; Andou, Y. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles/Porphyrin/Reduced Graphene Oxide Hydrogel as Dye Adsorbent for Wastewater Treatment. FlatChem 2020, 23, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, G.J.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, D.; Zhou, J.; Sun, R. Removed Heavy Metal Ions from Wastewater Reuse for Chemiluminescence: Successive Application of Lignin-Based Composite Hydrogels. J Hazard Mater 2022, 421, 126722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.T.; Joo, S.W.; Berkani, M.; Mashifana, T.; Kamyab, H.; Wang, C.; Vasseghian, Y. Sustainable Cellulose-Based Hydrogels for Water Treatment and Purification. Ind Crops Prod 2023, 205, 117525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Md.S.; Hossain, Md.M.; Khatun, Most.K.; Hossain, K.R. Hydrogel-Based Superadsorbents for Efficient Removal of Heavy Metals in Industrial Wastewater Treatment and Environmental Conservation. Environmental Functional Materials 2023, 2, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Mu, B.; Zong, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, A. One-Step Green Construction of Granular Composite Hydrogels for Ammonia Nitrogen Recovery from Wastewater for Crop Growth Promotion. Environ Technol Innov 2024, 33, 103465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacon, A.; Albota, F.; Mocanu, A.; Brincoveanu, O.; Podaru, A.I.; Rotariu, T.; Ahmad, A.A.; Rusen, E.; Toader, G. Dual-Responsive Hydrogels for Mercury Ion Detection and Removal from Wastewater. Gels 2024, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godiya, C.B.; Martins Ruotolo, L.A.; Cai, W. Functional Biobased Hydrogels for the Removal of Aqueous Hazardous Pollutants: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. J Mater Chem A Mater 2020, 8, 21585–21612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Zhang, Z.; Mo, F.; Wang, Y. A Review of Functional Hydrogels for Flexible Chemical Sensors. Advanced Sensor Research 2024, 3, 2300021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sun, L.; Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Song, J.; Qian, S.; Liu, Z.; Guan, Q.; Meade Jeffries, E.; Liu, W.; et al. Mechanically and Biologically Skin-like Elastomers for Bio-Integrated Electronics. Nature Communications 2020, 11:1 2020(11), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Lv, S.; Zuo, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Zeng, Q. Engineering Versatile Bi-Network Ionic Conductive Hydrogels Wearable Sensors via on Demand Graft Modification for Real-Time Human Movement Monitoring. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 154176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, F.; Xu, Z.; Chen, F.; Shi, Y.; Hou, C.; Huang, Y.; Lin, C.; Yu, R.; et al. Highly Stretchable, Adhesive, and Self-Healing Silk Fibroin-Dopted Hydrogels for Wearable Sensors. Adv Healthc Mater 2021, 10, 2002083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Zhou, P.; Hu, F.; Rong, Y.; Lu, B.; Gu, G.; Shen, Z.; et al. High-Stretchability, Ultralow-Hysteresis ConductingPolymer Hydrogel Strain Sensors for Soft Machines. Advanced Materials 2022, 34, 2203650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Ma, Y.; Wei, H.; Lü, S.; Ren, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. An Anti-Swellable Hydrogel Strain Sensor for Underwater Motion Detection. Adv Funct Mater 2022, 32, 2107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fei, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, J.; Xu, L.; Li, Y. Polyionic Liquids Supramolecular Hydrogel with Anti-Swelling Properties for Underwater Sensing. J Colloid Interface Sci 2022, 628, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Sheng, Y.; Yao, L.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, S. Anti-Swelling Conductive Polyampholyte Hydrogels via Ionic Complexations for Underwater Motion Sensors and Dynamic Information Storage. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 463, 142439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Song, W.J.; Sun, J.Y. Hydrogel Soft Robotics. Materials Today Physics 2020, 15, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhao, Q.; Che, L.; Li, M.; Leng, X.; Long, Y.; Lu, Y. Multi-Stimuli-Responsive Weldable Bilayer Actuator with Programmable Patterns and 3D Shapes. Adv Funct Mater 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J. Tetherless and Batteryless Soft Navigators and Grippers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 14345–14356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zeng, L.; Qiao, Z.; Wang, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.S.; Yang, H. Functionalizing Double-Network Hydrogels for Applications in Remote Actuation and in Low-Temperature Strain Sensing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 30247–30258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jang, B.; Harduf, Y.; Chapnik, Z.; Avci, Ö.B.; Chen, X.; Puigmartí-Luis, J.; Ergeneman, O.; Nelson, B.J.; Or, Y.; et al. Helical Klinotactic Locomotion of Two-Link Nanoswimmers with Dual-Function Drug-Loaded Soft Polysaccharide Hinges. Advanced Science 2021, 8, 2004458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Chang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Liang, Y.; Ren, L.; Ren, L. Bionic Intelligent Soft Actuators: High-Strength Gradient Intelligent Hydrogels with Diverse Controllable Deformations and Movements. J Mater Chem B 2020, 8, 9362–9373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Guan, J. Thermosensitive Hydrogels for Drug Delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2011, 8, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Li, M.; Chen, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Kong, Y.; Zuo, X. Synthesis of Stimuli-Responsive Copolymeric Hydrogels for Temperature, Reduction and PH-Controlled Drug Delivery. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2025, 143, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wei, H.; Yu, C.Y. Injectable Hydrogels as Emerging Drug-Delivery Platforms for Tumor Therapy. Biomater Sci 2024, 12, 1151–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Agarwal, R.; Alam, M.S. Hydrogels for Wound Healing Applications. Biomedical Hydrogels 2011, 184–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, S.; Martín, C.; Kostarelos, K.; Prato, M.; Vázquez, E. Nanocomposite Hydrogels: 3D Polymer-Nanoparticle Synergies for on-Demand Drug Delivery. In ACS Nano; GIF, 2015; Volume 9, pp. 4686–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Qin, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Cui, W.; Li, F.; Xiang, N.; He, X. Injectable Thermosensitive Hydrogel-Based Drug Delivery System for Local Cancer Therapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2021, 200, 111581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Roach, D.J.; Wu, J.; Hamel, C.M.; Ding, Z.; Wang, T.; Dunn, M.L.; Qi, H.J. Advances in 4D Printing: Materials and Applications. Adv Funct Mater 2019, 29, 1805290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanjin, M.; Rejab, M.R.M.; Idris, M.S.; Kumar, N.M.; Abdullah, M.H.; Reddy, G.R. Recent 3D and 4D Intelligent Printing Technologies: A Comparative Review and Future Perspective. Procedia Comput Sci 2020, 167, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, G.H.; Pei, E.; Harrison, D.; Monzón, M.D. An Overview of Functionally Graded Additive Manufacturing. Addit Manuf 2018, 23, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Owusu, K.A.; Mai, L.; Ke, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, P.; Magdassi, S.; Long, Y. Vanadium Dioxide for Energy Conservation and Energy Storage Applications: Synthesis and Performance Improvement. Appl Energy 2018, 211, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Li, M.; White, T.J.; Long, Y. Vanadium Dioxide: The Multistimuli Responsive Material and Its Applications. Small 2018, 14, 1802025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Franco, B.; Tapia, G.; Karayagiz, K.; Johnson, L.; Liu, J.; Arroyave, R.; Karaman, I.; Elwany, A. Spatial Control of Functional Response in 4D-Printed Active Metallic Structures. Scientific Reports 2017, 7:1 2017(7), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champeau, M.; Alves Heinze, D.; Nunes Viana, T.; Rodrigues de Souza, E.; Cristine Chinellato, A.; Titotto, S.; Champeau, M.; Heinze, D.A.; Viana, T.N.; de Souza, E.R.; et al. 4D Printing of Hydrogels: A Review. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Henríquez, C.M.; Sarabia-Vallejos, M.A.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, J. Polymers for Additive Manufacturing and 4D-Printing: Materials, Methodologies, and Biomedical Applications. Prog Polym Sci 2019, 94, 57–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.; Reidy, J.P.; Pötschke, J. Sinter-Based Additive Manufacturing of Hardmetals: Review. Int J Refract Metals Hard Mater 2023, 119, 263–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafadar, A.; Guzzomi, F.; Rassau, A.; Hayward, K. Advances in Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Common Processes, Industrial Applications, and Current Challenges. Applied Sciences 2021, Vol. 11 11, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaee, M.; Crane, N.B. Binder Jetting: A Review of Process, Materials, and Methods. Addit Manuf 2019, 28, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlizky, D.; Das, M.; Zheng, B.; Vyatskikh, A.L.; Bose, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Schoenung, J.M.; Lavernia, E.J.; Eliaz, N. Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Additive Manufacturing: Physical Characteristics, Defects, Challenges and Applications. Materials Today 2021, 49, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülcan, O.; Günaydın, K.; Tamer, A. The State of the Art of Material Jetting—A Critical Review. Polymers 2021, Vol. 13 13, 2829 2021 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleff, A.; Küster, B.; Stonis, M.; Overmeyer, L. Process Monitoring for Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing: A State-of-the-Art Review. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2021, 4 2021(6), 705–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev Singh, D.; Mahender, T.; Raji Reddy, A. Powder Bed Fusion Process: A Brief Review. Mater Today Proc 2021, 46, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M. Additive Manufacturing Processes in Medical Applications. Materials 2021, Vol. 14 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Tang, W.; Li, N.; Yang, J. The Recent Development of Vat Photopolymerization: A Review. Addit Manuf 2021, 48, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puza, F.; Lienkamp, K. 3D Printing of Polymer Hydrogels—From Basic Techniques to Programmable Actuation. Adv Funct Mater 2022, 32, 2205345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liz-Basteiro, P.; Reviriego, F.; Martínez-Campos, E.; Reinecke, H.; Elvira, C.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Gallardo, A. Vat Photopolymerization 3D Printing of Hydrogels with Re-Adjustable Swelling. Gels 2023, 9, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchels, F.P.W.; Feijen, J.; Grijpma, D.W. A Review on Stereolithography and Its Applications in Biomedical Engineering. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 6121–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Mapili, G.; Suhali, G.; Chen, S.; Roy, K. A Digital Micro-Mirror Device-Based System for the Microfabrication of Complex, Spatially Patterned Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A 2006, 77, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Cohn, D. Temperature and PH Responsive 3D Printed Scaffolds. J Mater Chem B 2017, 5, 9514–9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzcategui, A.C.; Muralidharan, A.; Ferguson, V.L.; Bryant, S.J.; McLeod, R.R. Understanding and Improving Mechanical Properties in 3D Printed Parts Using a Dual-Cure Acrylate-Based Resin for Stereolithography. Adv Eng Mater 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Lu, Z.; Chester, S.A.; Lee, H. Micro 3D Printing of a Temperature-Responsive Hydrogel Using Projection Micro-Stereolithography. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, H. Automatic Method for Fabricating a Three-dimensional Plastic Model with Photo-hardening Polymer. Review of Scientific Instruments 1981, 52, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jiang, R.; Wu, J.; Song, J.; Bai, H.; Li, B.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T. Ultrafast Digital Printing toward 4D Shape Changing Materials. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1605390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakurt, I.; Aydoğdu, A.; Çıkrıkcı, S.; Orozco, J.; Lin, L. Stereolithography (SLA) 3D Printing of Ascorbic Acid Loaded Hydrogels: A Controlled Release Study. Int J Pharm 2020, 584, 119428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alketbi, A.S.; Shi, Y.; Li, H.; Raza, A.; Zhang, T.J. Impact of PEGDA Photopolymerization in Micro-Stereolithography on 3D Printed Hydrogel Structure and Swelling. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 7188–7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Zhang, J.; Bethel, K.; Liu, Y.; Davis, E.M.; Zeng, H.; Kong, Z.; Johnson, B.N. Closed-Loop Controlled Photopolymerization of Hydrogels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 40365–40378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalossaka, L.M.; Mohammed, A.A.; Sena, G.; Barter, L.; Myant, C. 3D Printing Nanocomposite Hydrogels with Lattice Vascular Networks Using Stereolithography. J Mater Res 2021, 36, 4249–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, D.W.; Gale, R.O. The Digital Micromirror Device for Projection Display. Microelectron Eng 1995, 27, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yu, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; Huang, W. Digital Light Processing 4D Printing of Transparent, Strong, Highly Conductive Hydrogels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 36286–36294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Ma, C.; Xie, W.; Tang, A.; Liu, W. An Effective DLP 3D Printing Strategy of High Strength and Toughness Cellulose Hydrogel towards Strain Sensing. Carbohydr Polym 2023, 315, 121006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprioli, M.; Roppolo, I.; Chiappone, A.; Larush, L.; Pirri, C.F.; Magdassi, S. 3D-Printed Self-Healing Hydrogels via Digital Light Processing. Nature Communications 2021, 12:1 2021(12), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, S.; Hingorani, H.; Serjouei, A.; Larush, L.; Pawar, A.A.; Goh, W.H.; Sakhaei, A.H.; Hashimoto, M.; Kowsari, K.; et al. Highly Stretchable Hydrogels for UV Curing Based High-Resolution Multimaterial 3D Printing. J Mater Chem B 2018, 6, 3246–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Smith, W.; Jackson, J.; Moran, B.; Cui, H.; Chen, D.; Ye, J.; Fang, N.; Rodriguez, N.; Weisgraber, T.; et al. Multiscale Metallic Metamaterials. Nature Materials 2016, 15:10 2016(15), 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Q.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.F.; Li, H.; He, X.; Yuan, C.; Liu, J.; Magdassi, S.; et al. 3D Printing of Highly Stretchable Hydrogel with Diverse UV Curable Polymers. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.A. Direct Ink Writing of 3D Functional Materials. Adv Funct Mater 2006, 16, 2193–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.A.; Smay, J.E.; Stuecker, J.; Cesarano, J. Direct Ink Writing of Three-Dimensional Ceramic Structures. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2006, 89, 3599–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smay, J.; Gratson, G.R.S.-A.; Gratson, GM; Shepherd, RF; Cesarano, J, III. undefined Directed Colloidal Assembly of 3D Periodic Structures. In Wiley Online LibraryJE Smay;JA LewisAdvanced Materials, 2002•Wiley Online Library; 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Jiang, Y.; Ji, Z.; Yang, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qin, H.; Jia, X.; Wang, X. Three-Dimensional Printing of High-Performance Polyimide by Direct Ink Writing of Hydrogel Precursor. J Appl Polym Sci 2021, 138, 50636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Chan, K.H.; Wang, X.Q.; Ding, T.; Li, T.; Lu, X.; Ho, G.W. Direct-Ink-Write 3D Printing of Hydrogels into Biomimetic Soft Robots. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 13176–13184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Garcia, J.; Leahy, L.M.; Song, R.; Mullarkey, D.; Fei, B.; Dervan, A.; Shvets, I. V.; Stamenov, P.; Wang, W.; et al. 3D Printing of Multifunctional Conductive Polymer Composite Hydrogels. Adv Funct Mater 2023, 33, 2214196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Yang, C. Direct-Ink-Write Printing of Hydrogels Using Dilute Inks. iScience 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Sharabani-Yosef, O.; Eliaz, N.; Mandler, D. Hydrogel-Integrated 3D-Printed Poly(Lactic Acid) Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. J Mater Res 2021, 36, 3833–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tan, C.; Li, L. Review of 3D Printable Hydrogels and Constructs. Mater Des 2018, 159, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demoly, F.; Dunn, M.L.; Wood, K.L.; Qi, H.J.; André, J.C. The Status, Barriers, Challenges, and Future in Design for 4D Printing. Mater Des 2021, 212, 110193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Mohd Ripin, Z. 4D Printing in Biomedical Engineering: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Directions. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2023, Vol. 14 14, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Q.; Sakhaei, A.H.; Lee, H.; Dunn, C.K.; Fang, N.X.; Dunn, M.L. Multimaterial 4D Printing with Tailorable Shape Memory Polymers. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercea, M. Bioinspired Hydrogels as Platforms for Life-Science Applications: Challenges and Opportunities. Polymers 2022, Vol. 14 14, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, T.; Luo, M.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X. Recent Progress of Anti-Freezing, Anti-Drying, and Anti-Swelling Conductive Hydrogels and Their Applications. Polymers 2024, Vol. 16 16, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Huo, P.; Teng, P.; Ding, H.; Shen, X. Recent Progress in Fabrications, Properties and Applications of Multifunctional Conductive Hydrogels. Eur Polym J 2024, 208, 112895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Alshareef, H.N.; Dong, X. 3D Printing of Hydrogels for Stretchable Ionotronic Devices. Adv Funct Mater 2021, 31, 2107437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystyjan, M.; Koshenaj, K.; Ferrari, G. A Comprehensive Review on Starch-Based Hydrogels: From Tradition to Innovation, Opportunities, and Drawbacks. Polymers 2024, Vol. 16 16, Page 1991 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.D.C.; Costa, D.C.S.; Correia, T.R.; Gaspar, V.M.; Mano, J.F. Natural Origin Biomaterials for 4D Bioprinting Tissue-Like Constructs. Adv Mater Technol 2021, 6, 2100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xiao, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Duan, G.; Wu, Y.; Gong, X.; Wang, H. Design and Fabrication of Conductive Polymer Hydrogels and Their Applications in Flexible Supercapacitors. J Mater Chem A Mater 2020, 8, 23059–23095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Hydrogels as an Emerging Material Platform for Solar Water Purification. In Acc Chem Res; GIF, 2019; Volume 52, pp. 3244–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Yu, D.; Wang, S.; Fu, L.; Lin, Y. Nanosheet–Hydrogel Composites: From Preparation and Fundamental Properties to Their Promising Applications. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.M.; Dong, K.; Liu, Z.Q.; Xu, F. Double Network Hydrogel with High Mechanical Strength: Performance, Progress and Future Perspective. Sci China Technol Sci 2012, 55, 2241–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Schaffer, S.; Dai, K.; Yao, L.; Feinberg, A.; Webster-Wood, V. 3D Printing Hydrogel-Based Soft and Biohybrid Actuators: A Mini-Review on Fabrication Techniques, Applications, and Challenges. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Schaffer, S.; Dai, K.; Yao, L.; Feinberg, A.; Webster-Wood, V. 3D Printing Hydrogel-Based Soft and Biohybrid Actuators: A Mini-Review on Fabrication Techniques, Applications, and Challenges. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Schaffer, S.; Dai, K.; Yao, L.; Feinberg, A.; Webster-Wood, V. 3D Printing Hydrogel-Based Soft and Biohybrid Actuators: A Mini-Review on Fabrication Techniques, Applications, and Challenges. [CrossRef]

| Stimulus | Materials Responsible for Shape-Morphing | Material (Hydrogel: Composition of the Base Material) | Fabrication Technique | Proposed Application(s) |

Authors | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | poly(NIPAM-co-DMAPMA)/clay | Bilayer NIPAM+DMAPMA+ crosslinking agent (MBA)+ light initiator TPO+ rheological modifier (Laponite XLG) |

DIW | Bionic | Yangyang Li et. al | [95] |

| Temperature | PVA/(PVA-MA)-g-PNIPAM | PVA + NIPAM + Photoabsorber (tartrazineas) + light initiator TPO | DLP | Actuators | Mutian Hua et al. | [96] |

| Temperature | PAA | Acrylic Acid+PI (TPO)+crosslinker (dexadecyl acrylate) | SLA | Biomedical | Turdimuhammad Abdullah et al. | [97] |

| Temperature | PNIPAM PNIPAM+PiPrOx | 2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline+ 2-Methyl-2-oxazoline+NIPAM+ PI (TPO)+ photoabsorber (Orange G) |

SLA | Biomedical | Thomas Brossier et al. | [98] |

| Temperature + pH |

NIPAAm+MA-BSA | poly(ethyleneoxide)-b-poly(propylene oxide)-b-poly(ethylene oxide)+Photocurer (Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate) | DIW | Biomaterials | Benjaporn Narupai et.al. | [99] |

| Temperature | PNIPAM+Alginate | NIPAAm+ crosslinker (PEGDA)+ PI+ rheological modifier (Laponite XLG) | - | soft robotics | Daria Podstawczyk et al. | [100] |

| Temperature | PNIPAM | NIPAM+ PI a-ketoglutaric acid+ cross-linker(MBA)+ Rheology modifier Carbomer 940 |

Extrusion+UV curing | Drug release |

S. Zu et al. | [101] |

| Temperature + Light |

PNIPAM + Prussian Blue Nanoparticles | NIPAM + PEG dimethacrylate)+ crosslinker (PEGDA700) + PI (Darocur 1173) | SLA | Actuators | Tristan Pelluau et.al. | [102] |

| Temperature | (PNIPA/PAA) | rheological modifier (Laponite)+ NIPAM+Crosslinker N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (Bis) + PI (LAP) | Extrusion | Actuators | Hao Zhao et al. | [103] |

| Temperature | PNIPAM/Alginate/CNF | NIPAM+PI (Irgacure)+crosslinker (MBA)+Crosslinker PEGDA+Reinforced (TCNF)+ | DIW | Drug Release | Rohit Goyal. et al. | [104] |

| Temperature | PNIPAM | NIPAM+crosslinker (MBA)+ rheology modifier (Carbomer) | DIW | controlled drug release |

Shou Zu et al. | [105] |

| Humidity | poly(MAA-co- OEGMA) |

oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate (OEGMA)+ ethacrylic acid (MAA)+ 4-Nitrophenyl benzoate (Catalyst) | DIW | soft robots | Zhen Jiang et al. | [106] |

| Humidity | PLA+PHBV | Bilayer Polyurethane+polyketone+PLA |

FDM | Smart structures | Yasaman Tahouni et al. | [107] |

| Temperature + Hydration |

Poly (N-vinyl caprolactam) (PNVCL) | Bilayer N, N-Dimethylacrylamid+NVCL+Crosslinker (PEGFMA)+ PI (Irgacure) |

SLA | actuator | Shuo Zhuo et al. | [108] |

| Ca2+/chitosan | Sodium Alginate | Sodium alginate+ 2-(Dimethylamino) ethyl methacrylate+ methacrylic anhydride+ PI 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone | DIW | - | Pengrui Cao et al. | [109] |

| Humidity | Chitosan+Acetic Acid | Chitosan Powder+Crosslinker (Critric Acid)+Rheological Modifier (trimethyl silane spray) | DIW | Actuator | Smruti Parimita et.al. | [110] |

| Water | non-isocyanate poly(hydroxyurethane) | poly(ethyleneglycol) + Chain Extender poly(ethylene oxide) diamine+ cross-linker tris(2-aminoethylene)amine (TAEA) | DIW | Biomedical | Noé Fanjul-Mosteirín et al. | [111] |