1. Introduction

Nowadays, we experience a high level of image production and manipulation, mainly due to the widespread use of cell phones and digital cameras, in addition to the constant traffic of images on the Internet, which encompasses virtually all areas of modern life. To maintain the security and confidentiality of this information, image encryption has become a topic of great current importance due to its applications in multiple domains. In particular, the protection and security of image databases consisting of human face banks [

1,

2] or biometric data [

3] are relevant to the vast majority of people, since everyone needs to transfer one or more images over the Internet at some point [

4,

5]. We also store and send private images through our social networks [

6,

7], among others. Moreover, there is a growing need for privacy in biomedical diagnostic images [

8,

9], as well as in scientific, spatial, military, governmental, and educational images. Thus, the need for encrypting digital images represents a current challenge in computational work ap-plied to a wide range of fields.

In recent years the use of chaotic functions in image encryption has become very popular, induced mainly by the intrinsic properties of chaotic systems, such as their non-linear behavior or their high sensitivity to initial conditions, which leads to the production of unpredictable pseudo-random sequences of values. Unlike traditional encryption algorithms, chaotic methods are better suited to the continuous and highly correlated nature of digital images, providing more effective confusion and diffusion mechanisms. Early approaches relied on simple one-dimensional maps, such as the logistic or tent maps, which were easy to implement but offered limited security. Since 2019, however, the dominant trend has been the use of two-dimensional and hyperchaotic maps, which expand the key space and improve the entropy of the encrypted image [

10,

11]. Among these, systems that combine logistic, sine, or exponential maps, as well as 3D–5D systems derived from Lorenz or Chen models, stand out. These produce multiple positive Lyapunov exponents, increasing the dynamic complexity and unpredictability of the encryption process [

11,

12].

A significant development in this period has been the integration of confusion and diffusion into a single, interdependent process, strengthening the relationship between original and encrypted pixels. For instance, Teng et al. [

10] introduced an algorithm based on a two-dimensional hyperchaotic map (2D-CLSS) that performs permutation and dif-fusion simultaneously. This approach achieves high NPCR (Number of Pixels Change Rate) and UACI (Unified Average Changing intensity) values and demonstrates strong robustness against differential attacks. Further innovations include hyperchaotic maps combined with exponential or logarithmic transformations to avoid non-chaotic regions and improve numerical stability [

11]. Additionally, chaotic systems have been integrated with bio-inspired cryptographic mechanisms, such as DNA encoding and dynamic S-boxes, to enhance nonlinearity and information dispersion [

13,

14].

More recently, artificial intelligence has become pivotal in developing modern encryption models that merge complex pseudo-random sources with deep learning. To counter the inherent linearity of traditional optical methods like Double Random Phase Encoding (DRPE), researchers have enhanced it with advanced techniques such as two-dimensional quantum walks for phase mask generation, significantly expanding the key space and attack resistance [

15,

16]. Another example is the AT-ResNet-CM model, designed for medical image encryption [

17]. In this and other hybrid models, chaotic maps act as a powerful pseudo-random source—a logistic system encrypts the ResNet’s output—while AI algorithms optimize the overall process. The ResNet architecture ex-tracts profound image features and accelerates convergence, and an attention mechanism intelligently guides the encryption to focus on critical regions, such as a medical image’s area of interest.

Building on this paradigm of hybridizing chaos with intelligent architectures, subsequent research has demonstrated the efficacy of directly coupling chaotic systems with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to elevate both security and operational efficiency. One such approach integrates the fundamental properties of randomness and nonlinear mapping from chaotic sequences with the advanced feature extraction capabilities of a CNN [

18]. This synergy enables robust encryption by performing dissimi-larity operations between the chaotic sequence and image pixels, guided by the high-level features identified by the network. The result is a significant enhancement in encryption quality and security, as confirmed by experimental comparisons with tradi-tional chaotic methods, alongside improved computational performance and faster en-cryption/decryption speeds. This trajectory indicates that the most advanced models are evolving beyond simple process combination towards deeply interconnected systems where AI actively shapes and reinforces the cryptographic transformation.

In this paper, we present a novel image encryption scheme that employs confusion and diffusion processes governed by chaotic functions. The encryption key is derived from 12 ASCII symbols and four user-selected words, which, through a Key Derivation Function (KDF), generate a 96-digit seed for two calls to the chaotic function. The confusion stage utilizes the first 48 digits to create a table. This table drives N successive operations that partition the image into blocks and perform intra-block pixel permuta-tions, resulting in a permuted image. The subsequent diffusion stage uses the remaining 48 digits to generate a chaotic matrix of the same dimensions as the permuted image. The final cipher-image is obtained via a modulo 256 sum between this matrix and the permuted image. The effectiveness of the proposed method has been verified through a series of security tests, the results of which are presented and discussed.

2. Encryption Method

The encryption process is applied to gray-level (GL) images initially stored at 8 bit depth, using confusion and diffusion processes in which chaotic functions play a key role, primarily due to their quasi-random nature. The encryption is performed on the real plane, where the image pixels to be encrypted are first permuted (confusion) and then distorted by a diffusion process consisting of performing a modular sum between image and chaotic values.

In our processes, color images (RGB) have not been considered for encryption because each of the three layers of these can be treated individually as a GL image, which implies that this same process must be repeated three times, but this does not add any complexity to the problem.

2.1. Chaotic Functions and Encryption

The proposed encryption scheme for 8-bit grayscale like the images is based on a two-stage process—confusion followed by diffusion—governed by a chaotic system. The core of this system is a two-dimensional map derived from the dynamics of a delta-kicked oscillator [

19,

20], defined by Eqs. (

1) and (

2). These must be iterated t times before beginning to construct the arrays of values that will be used in the encryption.

Here, the parameters k and , along with the initial seed values , form a critical part of the encryption key and are user-defined through the KDF. The number t of iterations prior to constructing the chaotic arrays is called the transient. The transient number is also part of the encryption key.

2.1.1. Dynamical Analysis of the Chaotic System

The two-dimensional chaotic system defined by Equations (

1) and (

2) is characterized by its capacity to generate complex, nonlinear trajectories in phase space, making it an ideal candidate for image encryption. To validate its utility as a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG), we numerically evaluate its dynamical properties. The parameter domains are constrained within the algorithm’s input specifications: the parameter

and

. All subsequent analyses of Lyapunov exponents and stability maps are performed within these bounds.

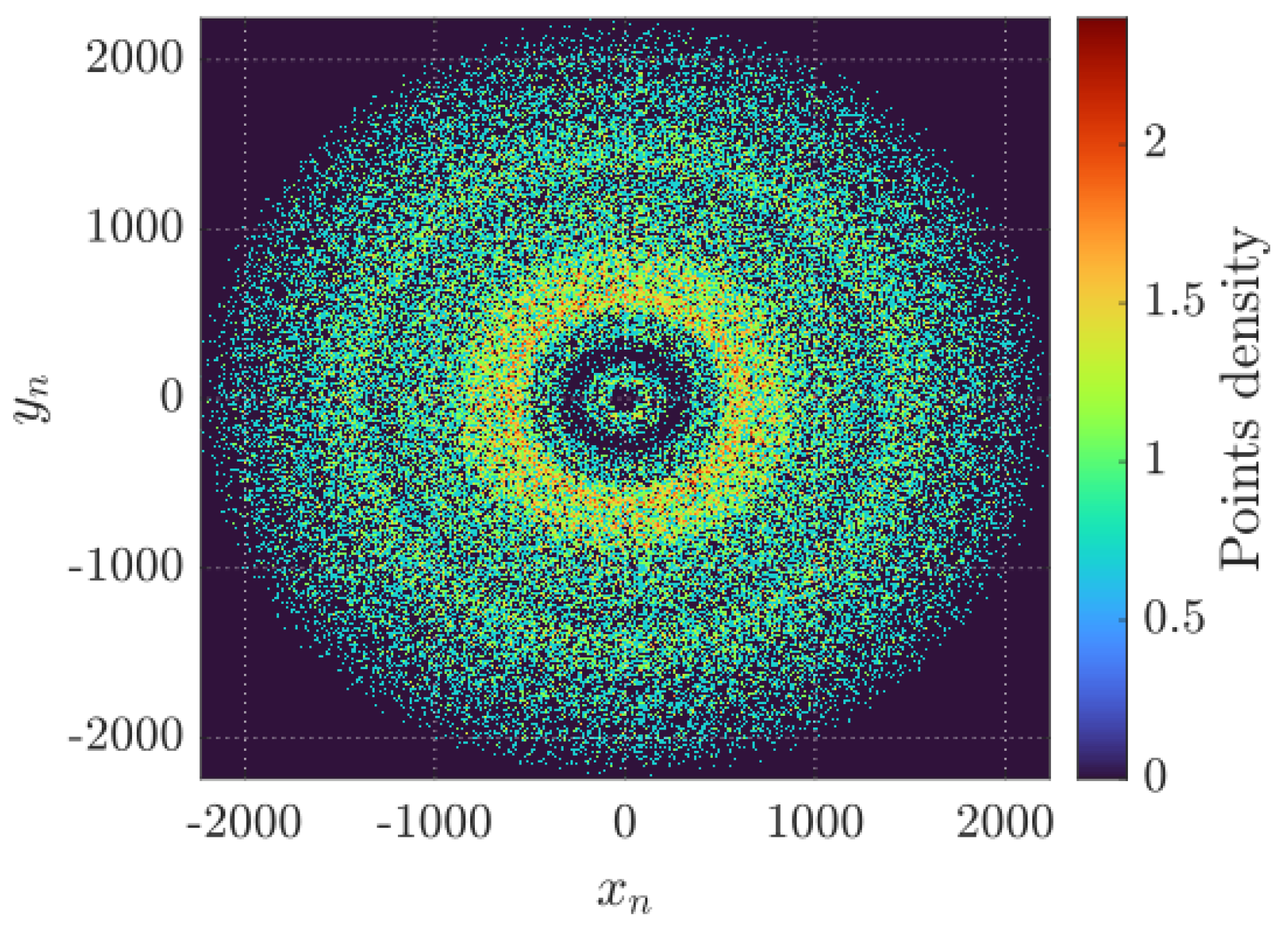

Figure 1 illustrates the system’s dynamical behavior and phase-space distribution after a transient of

iterations. The system exhibits a dense occupation of the phase space, with trajectories that are not confined to simple attractors or periodic orbits, indicating a fully developed chaotic dynamics. This

dense cloud structure suggests ergodic mixing and an absence of dominant periodic regions. This behavior is highly advantageous for encryption, as it implies that minor variations in initial parameters lead to highly unpredictable and divergent state evolutions.

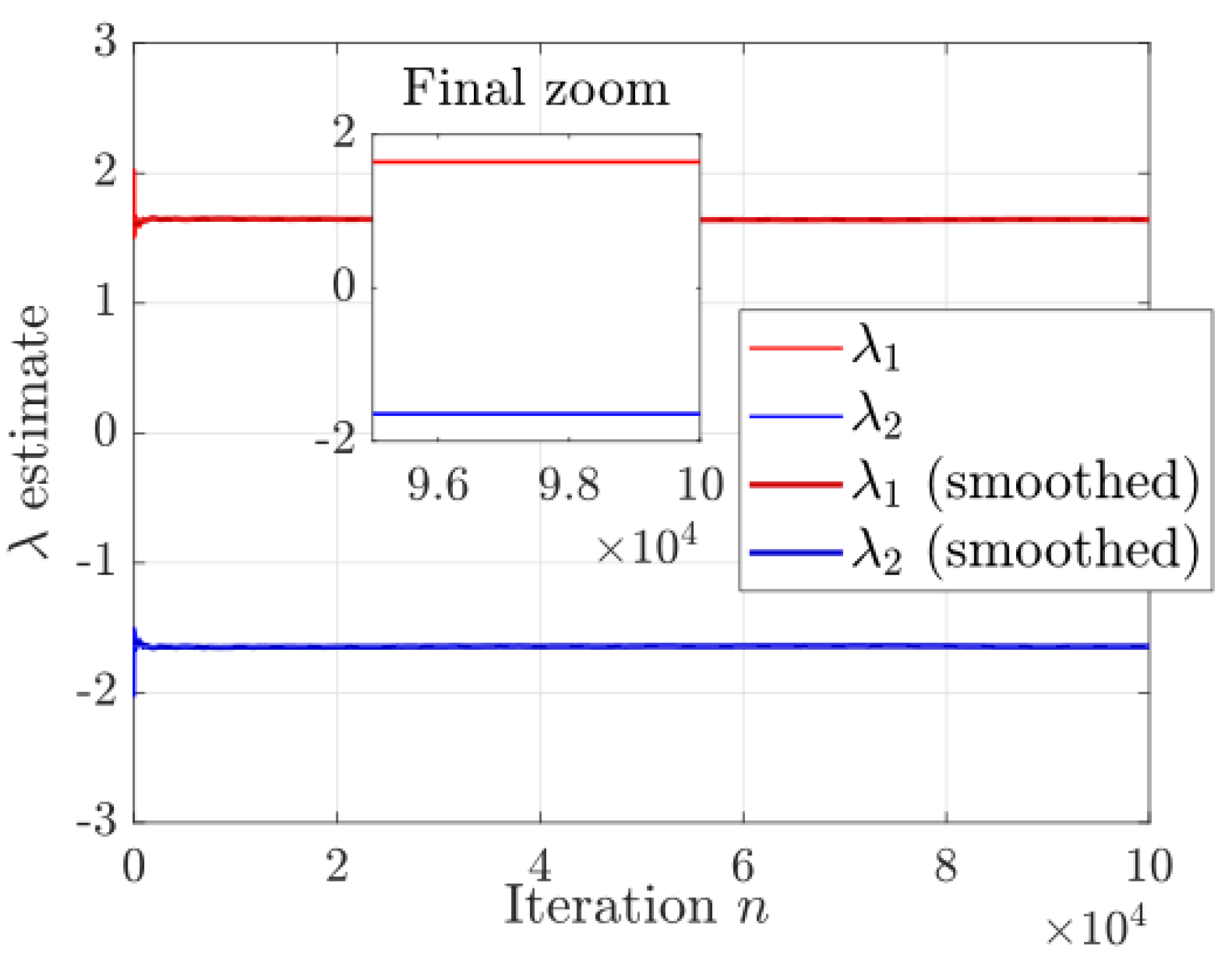

The Lyapunov exponents were calculated using the QR method of Benettin [

21] over

iterations, see

Figure 2. The obtained values are

and

. Their sum is practically zero

, confirming volume conservation in the phase space and verifying that the map is area-preserving.

Both exponents show stable convergence, indicating a sustained chaotic regime without appreciable numerical drift. The positive value of

represents the exponential divergence of nearby trajectories, while the negative value of

corresponds to a complementary contraction, maintaining the conservative nature of the system. The existence of a positive Lyapunov exponent of considerable magnitude confirms the system’s capacity to generate highly divergent and unpredictable sequences, an essential quality for a cryptographically robust PRNG, see the repository [

22].

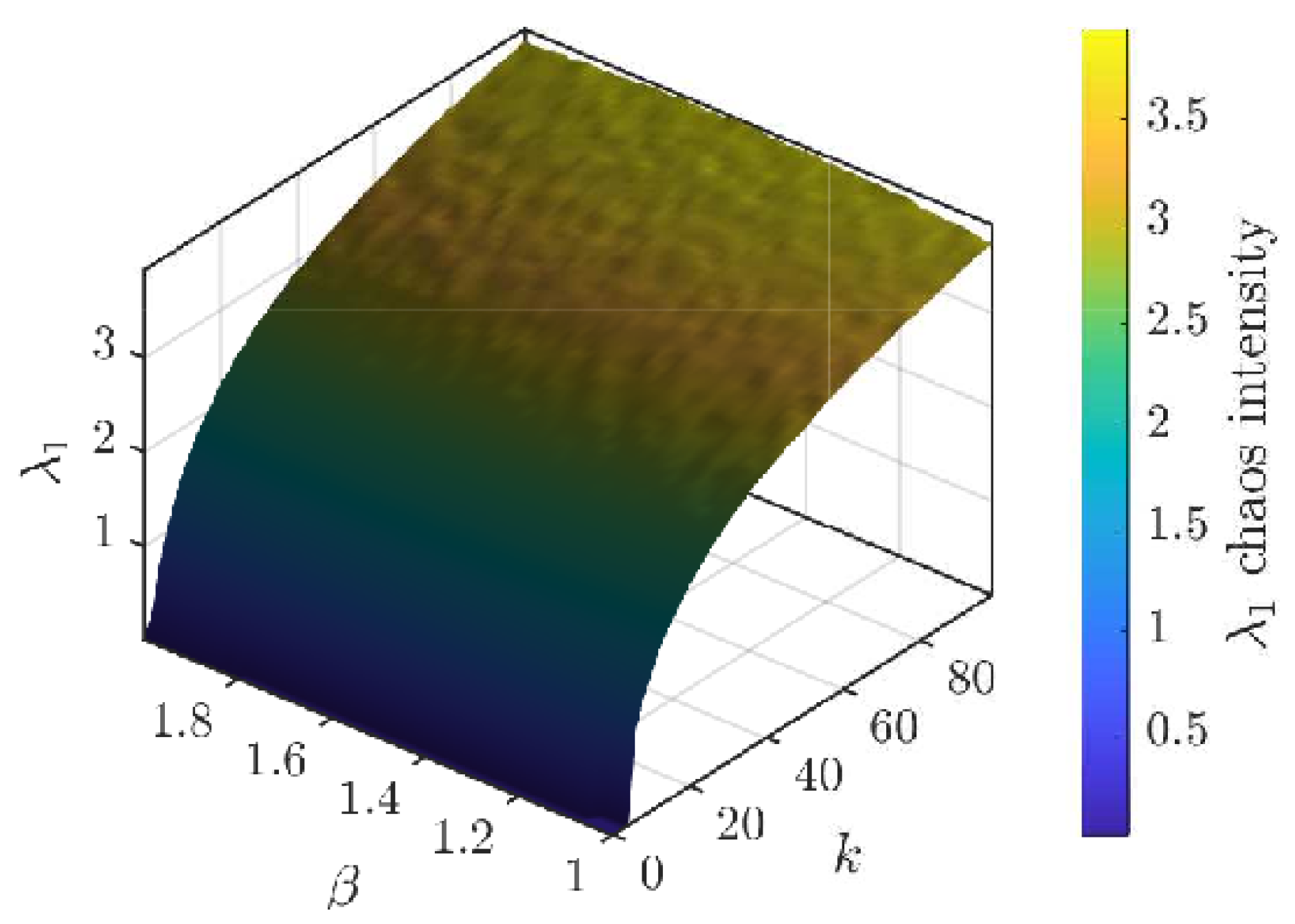

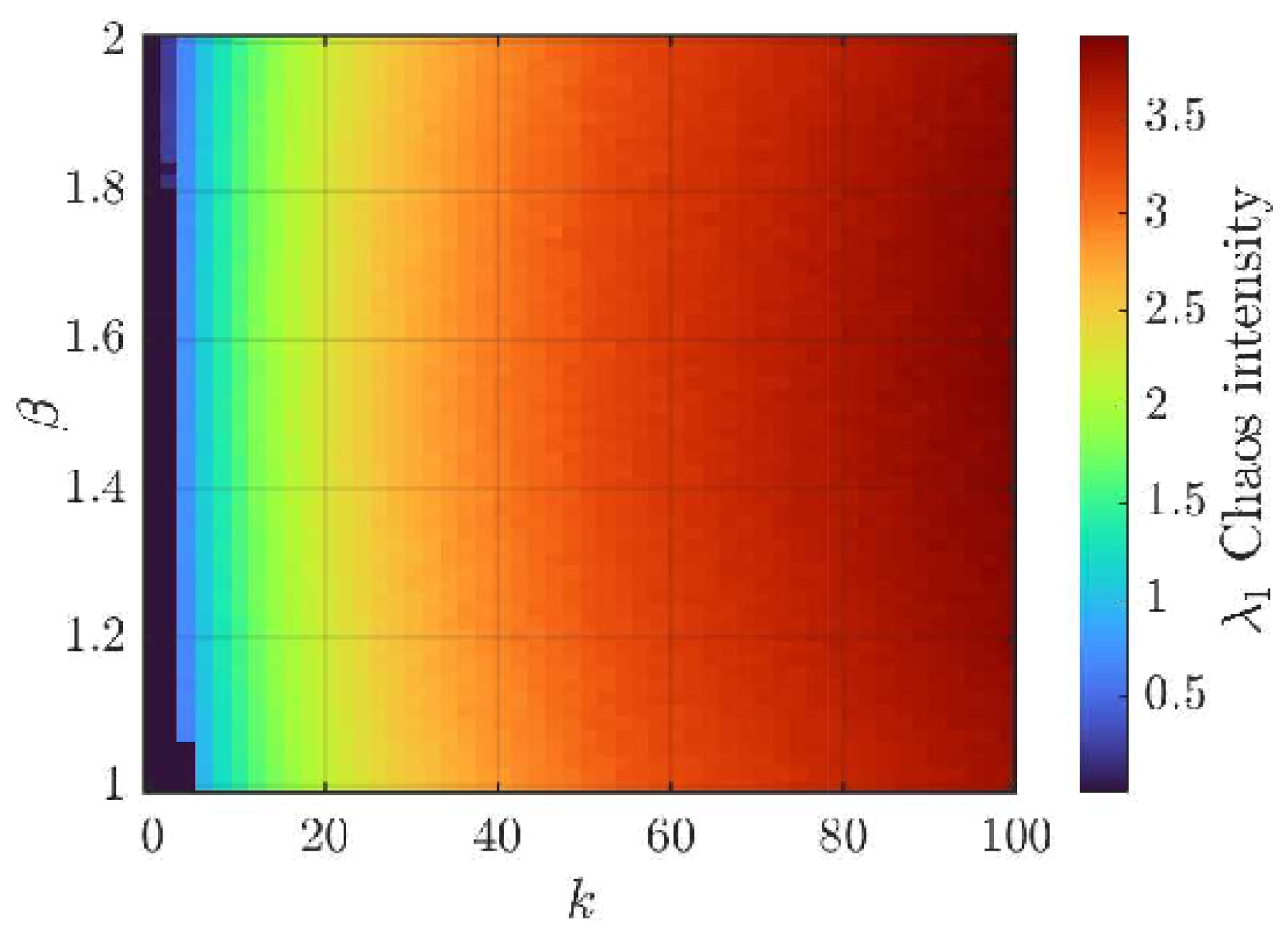

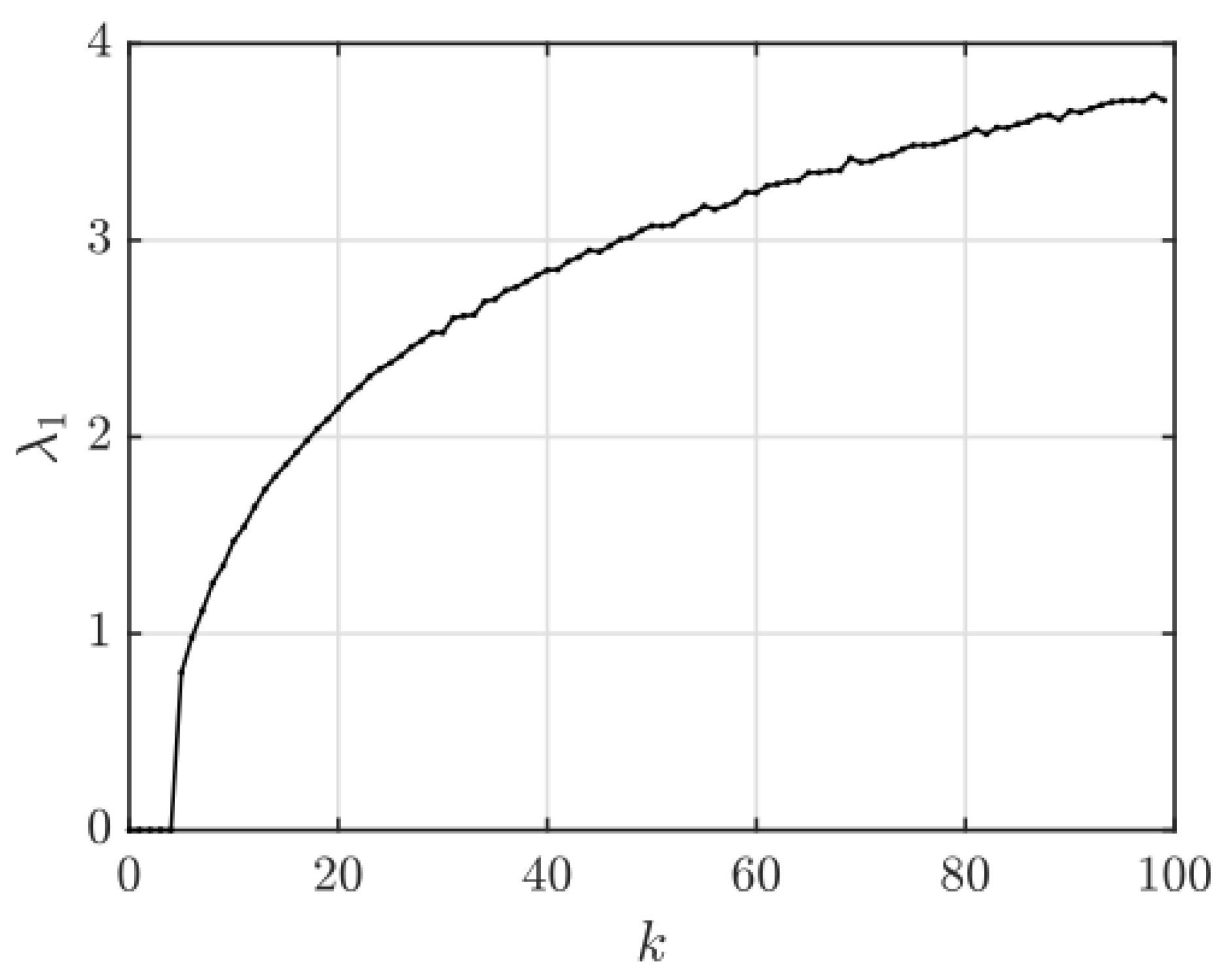

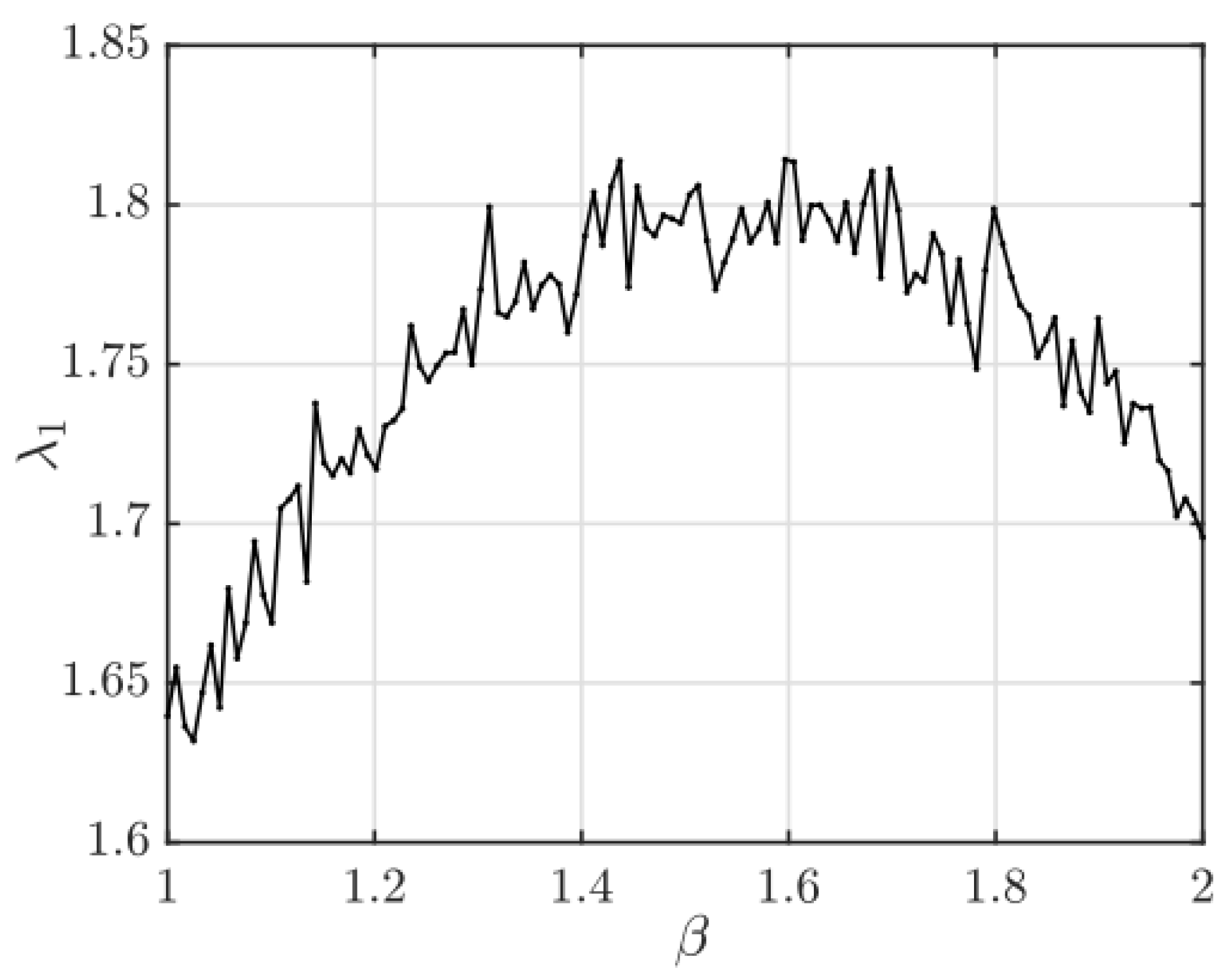

2.1.2. Parameter Space and Robust Chaos

Figure 3 presents the two-dimensional map of the Lyapunov exponent

, while

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show one-dimensional cuts

and

, respectively, highlighting regions of chaos and stability. These results reveal extensive regions of sustained chaos, primarily for

and

, where

. The edges of these regions correspond to quasi-periodic or transitional zones where the system may temporarily exhibit regular behavior.

Figure 3.

3D Lyapunov surface .

Figure 3.

3D Lyapunov surface .

Figure 4.

Average stability map of chaotic regions.

Figure 4.

Average stability map of chaotic regions.

Figure 5.

One-dimensional slices of the chaos regions and stability maps at .

Figure 5.

One-dimensional slices of the chaos regions and stability maps at .

Figure 6.

One-dimensional slices of the chaos regions and stability maps at .

Figure 6.

One-dimensional slices of the chaos regions and stability maps at .

Figure 4 extends this analysis through an average stability map, where yellow-to-red tones identify the most chaotic configurations (redder indicates stronger chaos) and blue tones indicate ordered behavior. The predominance of red confirms the existence of robust chaos across wide parametric variations. This property is highly desirable for crypto-graphic applications, as it guarantees statistical independence between sequences gen-erated under small perturbations of the control parameters, thereby ensuring a vast and reliable key space.

2.2. Generation of Encryption Chaotic Arrays

The encryption process begins with a user-defined key composed of twelve ASCII characters (including uppercase/lowercase letters, numbers, and symbols), each one corresponds to one number in the interval , providing an initial entropy of 96 bits. To transform this key into a robust cryptographic seed for the chaotic system, a key-derivation function (KDF) is applied.

The implemented KDF is PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256, configured with 200,000 iterations and a derived key length of 256 bits. A critical enhancement to the standard KDF is the use of a unique and deterministic salt. This salt is constructed from four user-provided “words” (actually, any arbitrary character strings) concatenated with an eight-character random sequence generated from printable ASCII codes. This

personalized plus random design ensures that even identical user inputs never produce the same derived key. To further guarantee entropy, the algorithm performs a redundancy check on the final salt. If half or more characters are repeated, an additional random block is injected. This ap-proach, implemented directly in the MATLAB key-derivation routine, see the repository, [

22] prevents degenerate seeds and eliminates collisions from low-entropy user inputs while maintaining an intuitive interface. This design strengthens the key space against brute-force attacks and aligns the system with modern cryptographic standards.

The KDF output (32 bytes = 256 bits) is then expanded into 96 balanced decimal digits by a nonlinear digit-generation function. These digits form a statistically uniform and entropy-preserving connection between the cryptographic and chaotic domains. The 96-digit sequence is divided into two independent 48-digit blocks: Block 1, which initializes the partition–permutation (PP) chaotic matrix controlling the confusion stage; and Block 2, which initializes the diffusion matrix. Each block undergoes an internal Fisher–Yates permutation of 48 positions, deterministically derived from the key bytes, ensuring maximal dispersion. The

digits are then mapped to the parameters of the chaotic functions according to the next assignment:

This process provides a deterministic, injective, and entropy-amplified mapping from the pair (user key, reinforced salt) to the chaotic system parameters. The dual-block structure guarantees that the confusion and diffusion phases remain statistically independent, avoiding cross-correlations that could degrade security. In the implementation shown here, the chaotic functions described in Eqs. (

1) and (

2) are applied twice: first, to construct the PP matrix of size

(

partition–permutation pairs), and second, to produce the diffusion matrix of

elements. The numerical values within each array are ordered according to the transient iteration count

t, as defined as follows:

Where J corresponds in each case to the number of entries in the array. When generating the first table corresponding to the partitions and permutations, the algorithm is conditioned to generate only digits, because each of these numbers is associated with a partition (in the first row) and a permutation (in the second row) preassigned within the algorithms. When generating the second matrix, the algorithm is conditioned to generate quasi-random values in the interval , because these are the values required for the modular sum between two square matrices of 1024 pixels on each side.

2.3. Mechanisms of Confusion and Diffusion

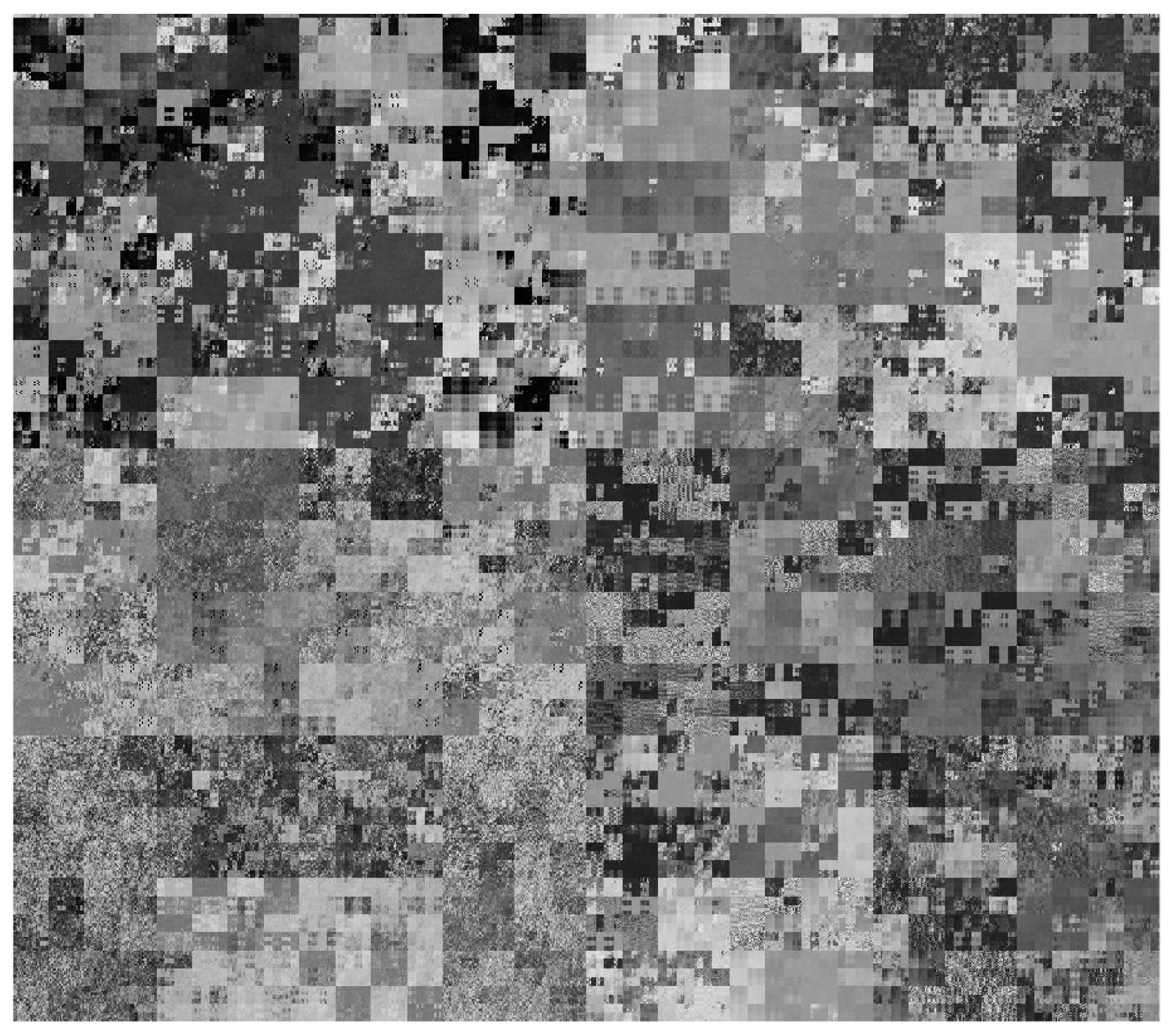

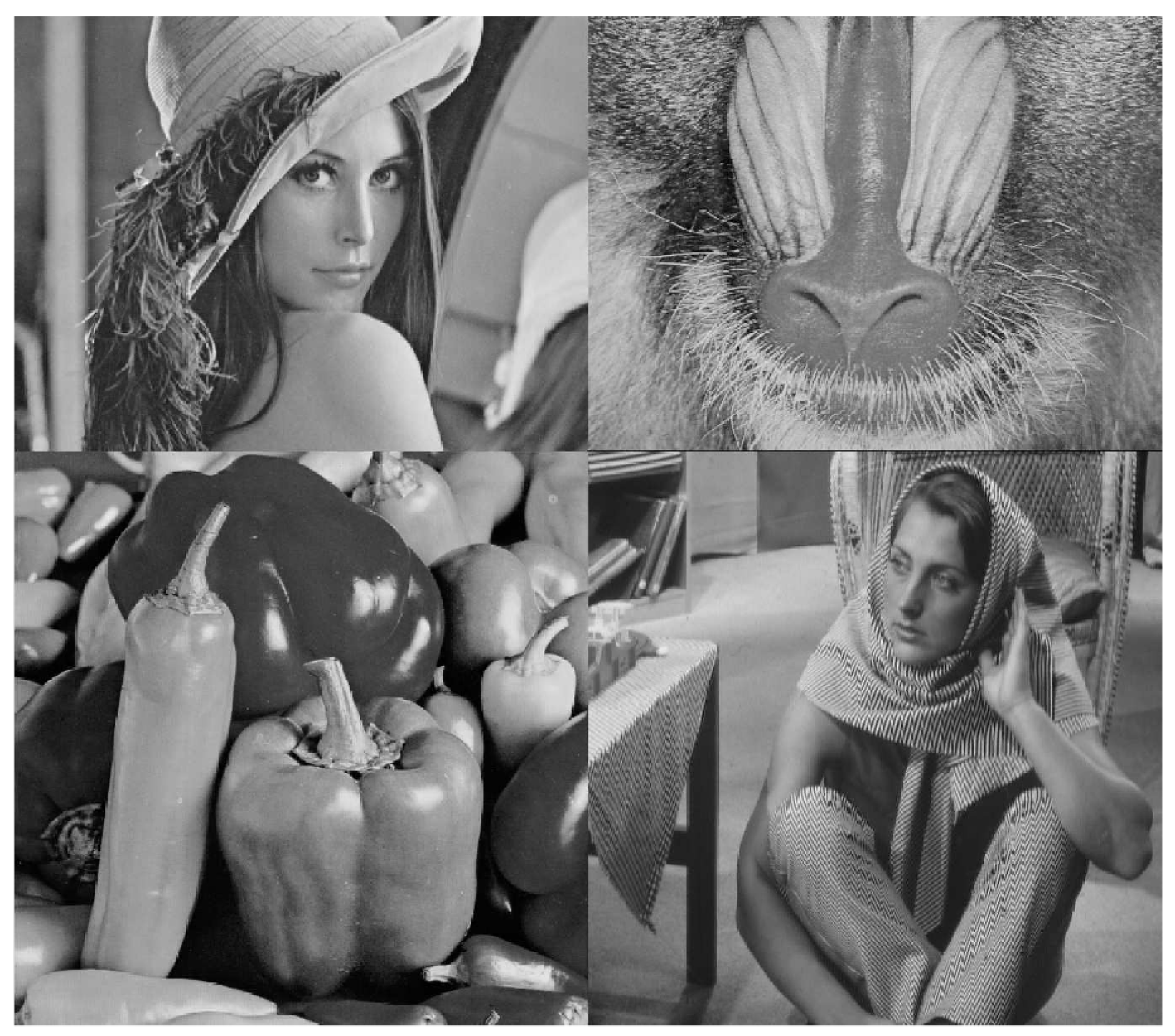

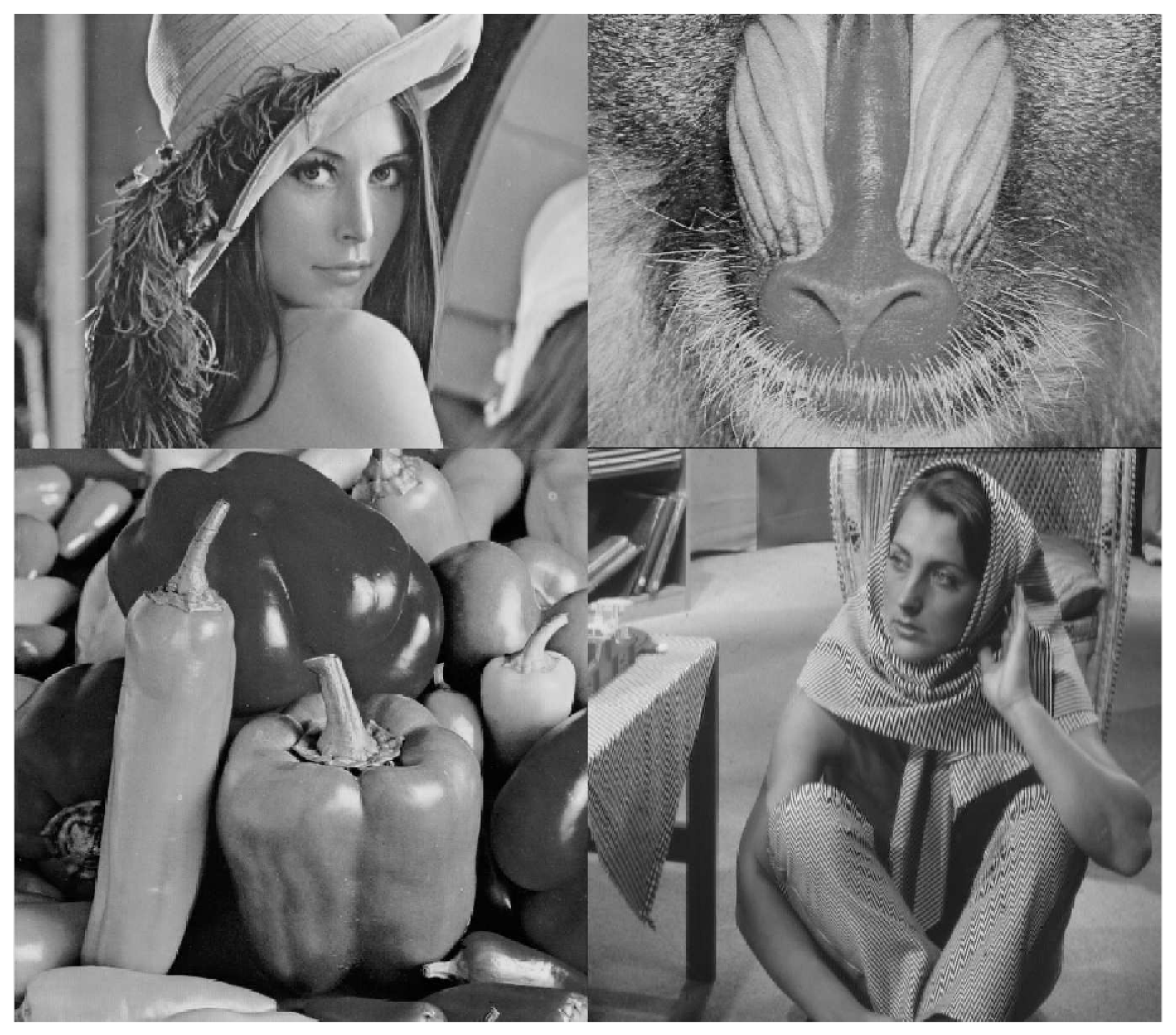

The image test to be encrypted has a size of 1024 square pixels, contains four human faces at 8 bits, and can be seen in

Figure 7.

The first stage of encryption is a confusion process performed on the image pixels, which in this case is applied to the one illustrated in

Figure 7, executed step by step, taking each pair of digits from the first chaotic matrix of partitions and permutations (which we will henceforth call the PP matrix), and applying it successively to the pixels as detailed below. To give a concrete example of the operation and application of the PP matrix, the first 48 digits of the key illustrated in the previous section are taken as inputs to the chaotic function, with which the data contained in

Table 1 are produced.

The first stage of encryption is a confusion process performed on the image pixels, which in this case is applied to the one illustrated in

Figure 7, executed step by step, taking each pair of digits from the first chaotic matrix of partitions and permutations (which we will henceforth call the PP matrix), and applying it successively to the pixels as detailed below. To give a concrete example of the operation and application of the PP matrix, the first 48 digits of the key illustrated in the previous section are taken as inputs to the chaotic function, with which the data contained in

Table 1 are produced.

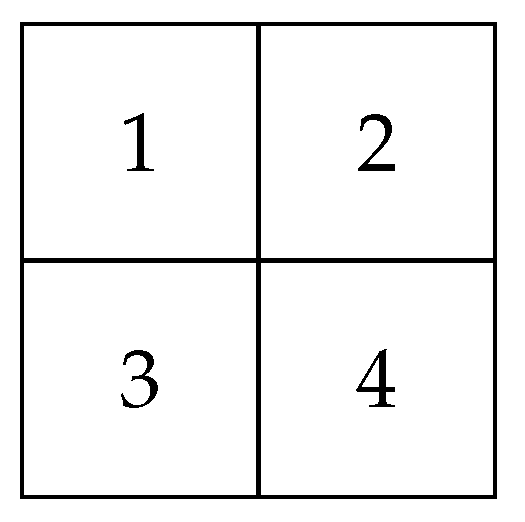

Next, we call the element of the first row Pa and the corresponding element of the second row Pe. For each pair of digits

in each column of the PP matrix, the algorithm partitions the image to be encrypted into square regions, so that the side with 1024 pixels is divided by

, which means that the possible options are between 1 and 512 regions per side, each of which has an even number of pixels per side between 1024 pixels if

(for

), and 2 pixels if

(for

). Each of these square regions is subdivided into four interior regions of

pixels per side, as can be seen illustrated in

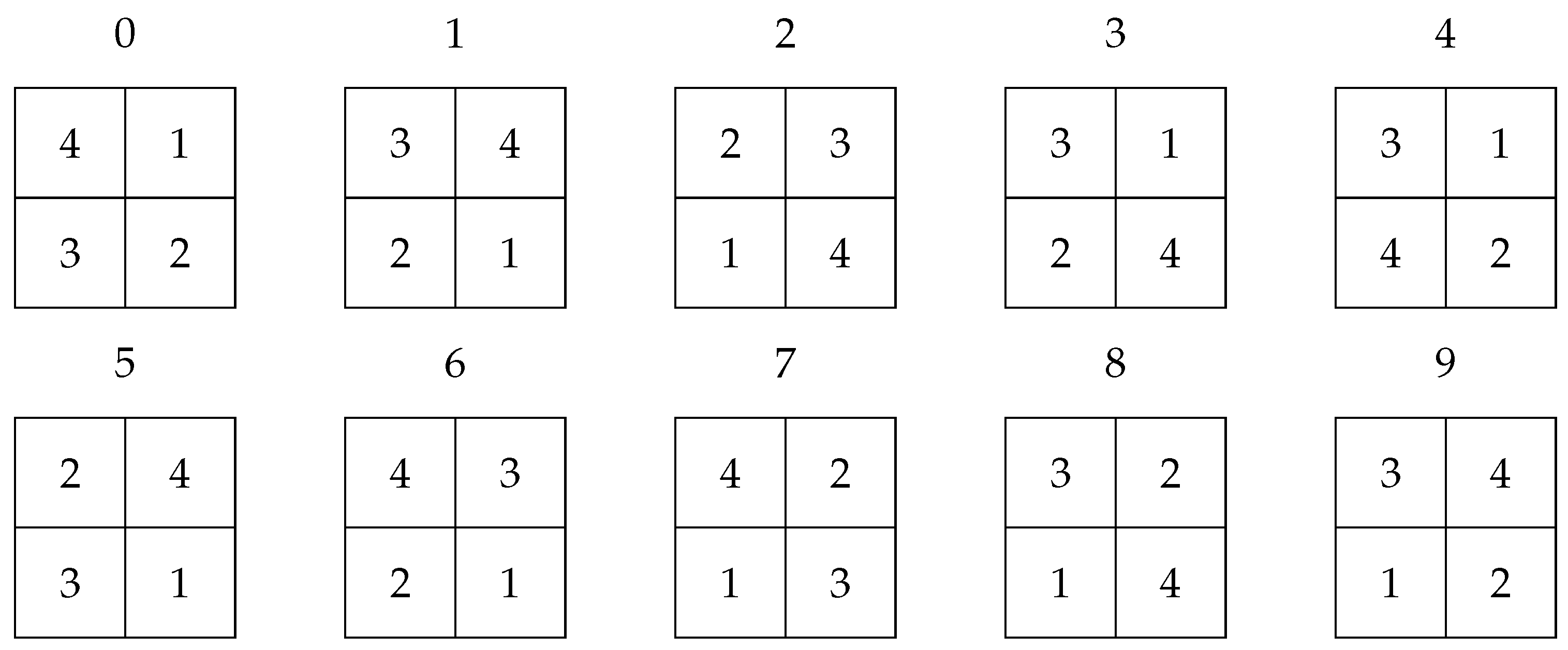

Figure 8.

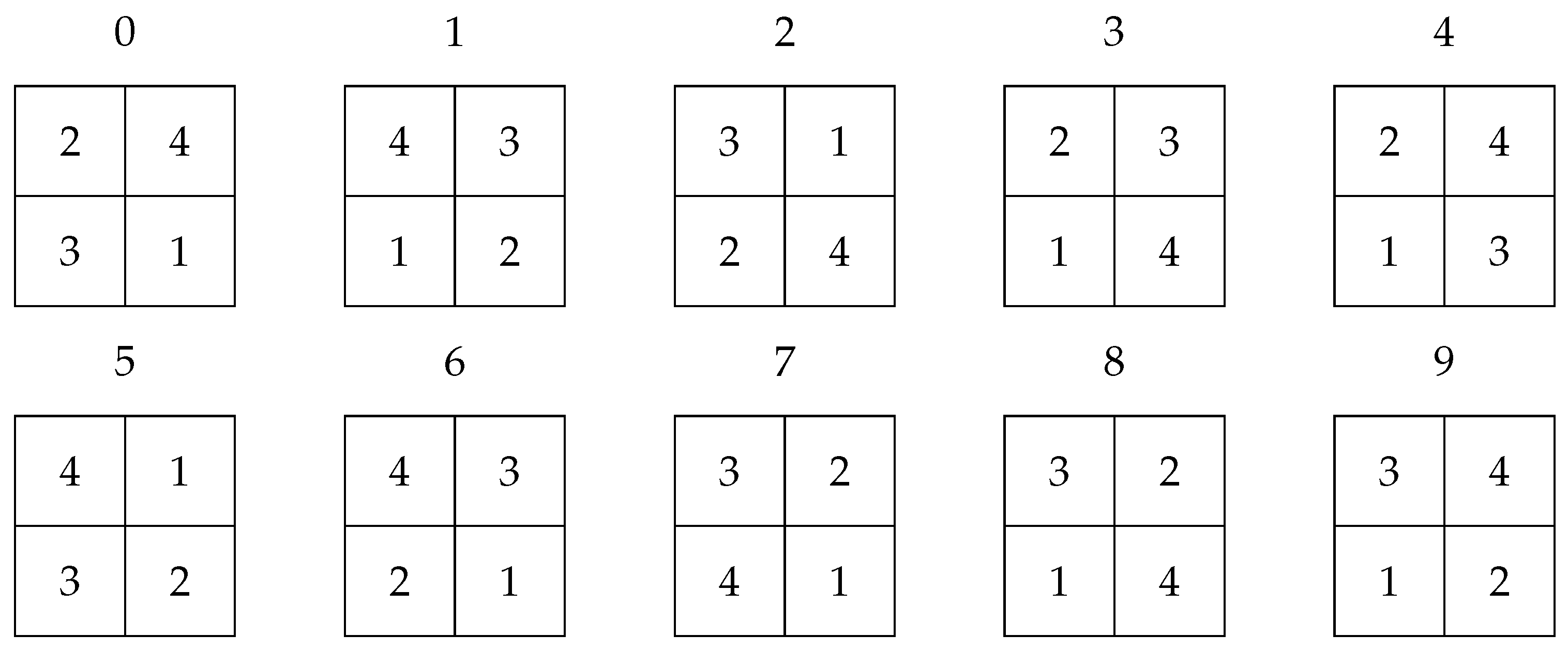

The four parts in

Figure 8 are labeled in the algorithm for subsequent permutation, corresponding to the digit Pe in their respective columns. The permutations are arbitrarily chosen from the 24 possible for this four-position configuration. In our case, the one shown in

Figure 9 was chosen, and it is implemented within the encryption program.

Figure 9.

Arbitrary assigning permutations to each digit. Source: The authors.

Figure 9.

Arbitrary assigning permutations to each digit. Source: The authors.

Figure 10.

Image obtained after the confusion process

1. Source: The authors.

Figure 10.

Image obtained after the confusion process

1. Source: The authors.

The process of pixel confusion ends once the process of partitions and permutations given by

Table 1 and

Figure 9 has finished, from which, for the case we are analyzing of encryption in

Figure 7, the image illustrated in

Figure 11 is obtained and which we will call from now on the mixed matrix, obtained after application of PP matrix expressed in

Figure 9.

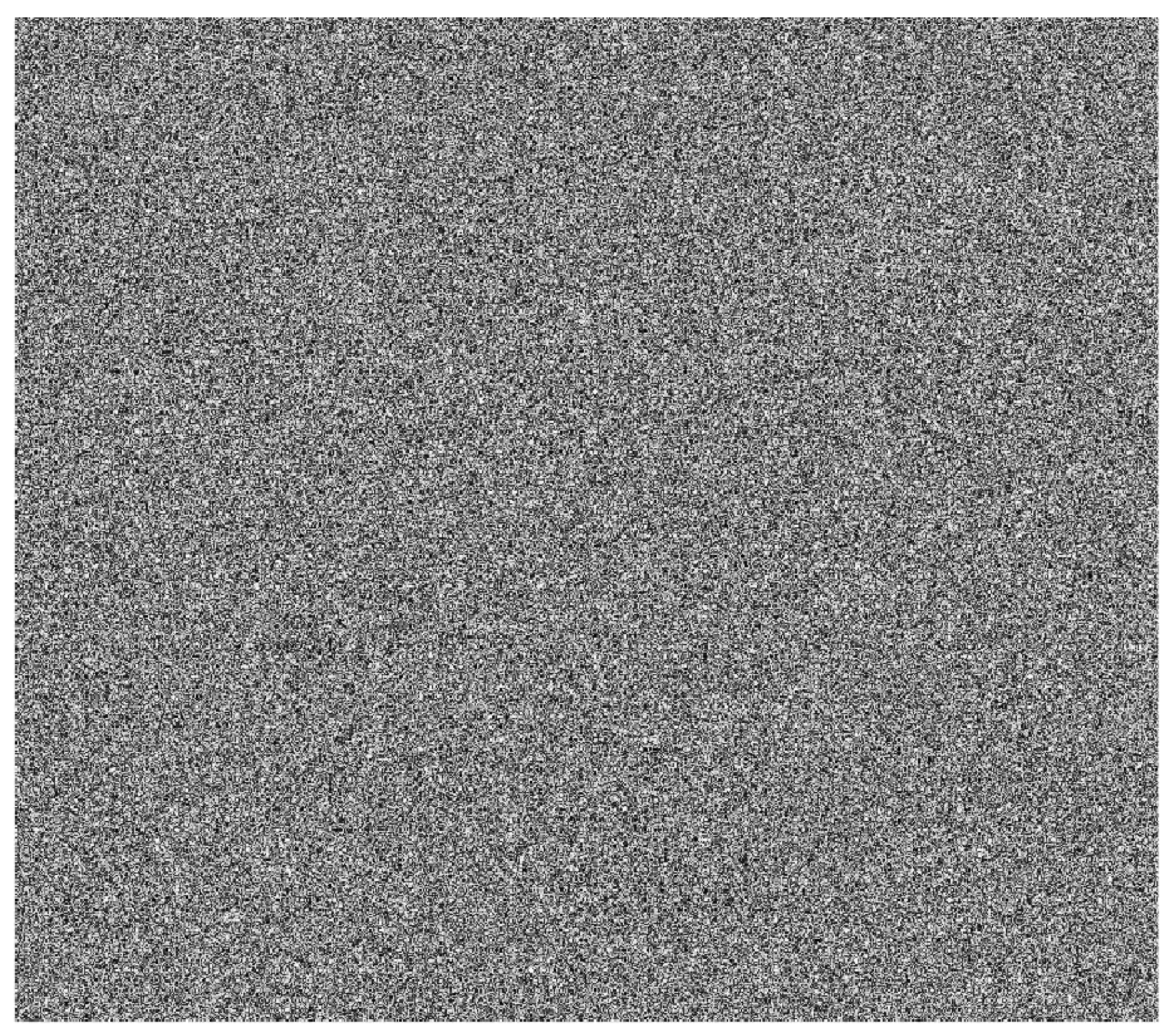

The next stage is the diffusion stage, for which the next 48 digits of the key are entered, distributed over the parameters of the chaotic functions, as specified in

Section 2.2, to generate the diffusion matrix, which is the same size as the image illustrated in

Figure 7 (

pixels). The diffusion process is performed by means of a modular sum within the interval

, since both the mixed matrix

X and the diffusion matrix

Y have integer inputs within this interval when represented as an 8-bit grayscale image.

To execute the modular sum, the result is determined by the following rule: if , but if . This form of modular addition guarantees that the result will always remain within the same interval and can therefore be stored as an 8-bit grayscale image and that this operation is reversible and allows the information X to be recovered if the encrypted image Z and the diffusion matrix Y are available.

The result of performing the modular addition between the mixed matrix

X and the diffusion matrix

Y, in our case, is the image illustrated in

Figure 11, which corresponds to the encrypted image

Z.

2.4. Decryption of Information

To decrypt the information, the key (12 symbols + 4 words) must be known in order to generate the data table or PP matrix, in addition to the diffusion matrix. Once these two matrices are known, we begin by reversing the modular sum to recover the mixed matrix

X. Since both the diffusion matrix

Y and the encrypted information

Z are known, the next step is to perform the inverse operation of the modular sum, which is executed as follows: If

then

, but if

, then

. In this way, the mixed matrix

X illustrated in

Figure 11 is recovered.

The next step is to reverse the confusion process, for which all partition and permutation steps given in

Table 1 must be reversed in an orderly manner, reversing all the permutation instructions in

Figure 9. The permutation reversal instructions are given in

Figure 12.

3. Results

In this process, all the steps described in this work have been followed to encrypt the image illustrated in

Figure 7, to which the confusion and diffusion steps described in

Section 2.3 have been applied, starting from the encryption key composed of twelve characters plus four words described in

Section 2.2. By using the 96 digits provided by this key, the PP and diffusion matrices have been constructed, which lead to the encrypted image illustrated in

Figure 11. Subsequently, the same key is used to decrypt the hidden image, reversing the diffusion and confusion steps. First, the scrambled matrix is recovered by applying the inverse operation of modular sum detailed at the

Section 2.3. Then, the partition and permutation process is reversed, traversing

Figure 12 from back to front until the original image is reached, which in our case is obtained with a quality index

. The recovered image is illustrated in

Figure 13.

3.1. Encryption Features

One of the qualities that a well-encrypted image must have is its randomness, which must be reflected in several objectively measurable aspects, such as an entropy that tends to 8 for grayscale images stored at 8-bit depth or a uniform distribution of its pixel values. Additionally, a statistical analysis of the correlation between adjacent pixels can be performed. In our case, measuring the entropy of the encrypted image illustrated in

Figure 6 yields a value

, which implies a high degree of randomness in the distribution of pixel values.

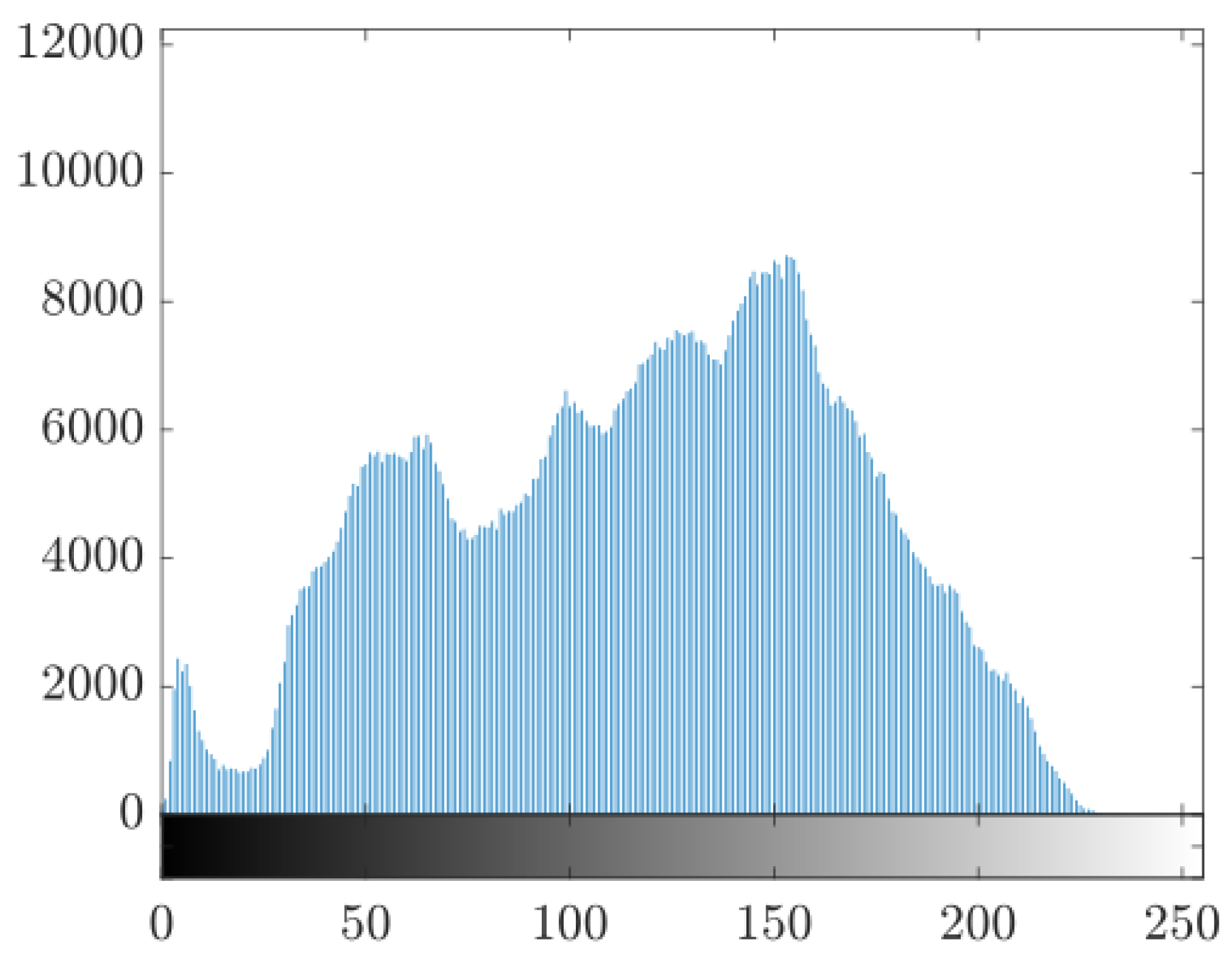

To compare this with other factors, the histograms of the original image can be compared with those of the encrypted image.

Figure 14 shows the histogram of the original image (seen in

Figure 7), which shows a non-uniform distribution that suggests the existence of recognizable patterns or characteristics in the image.

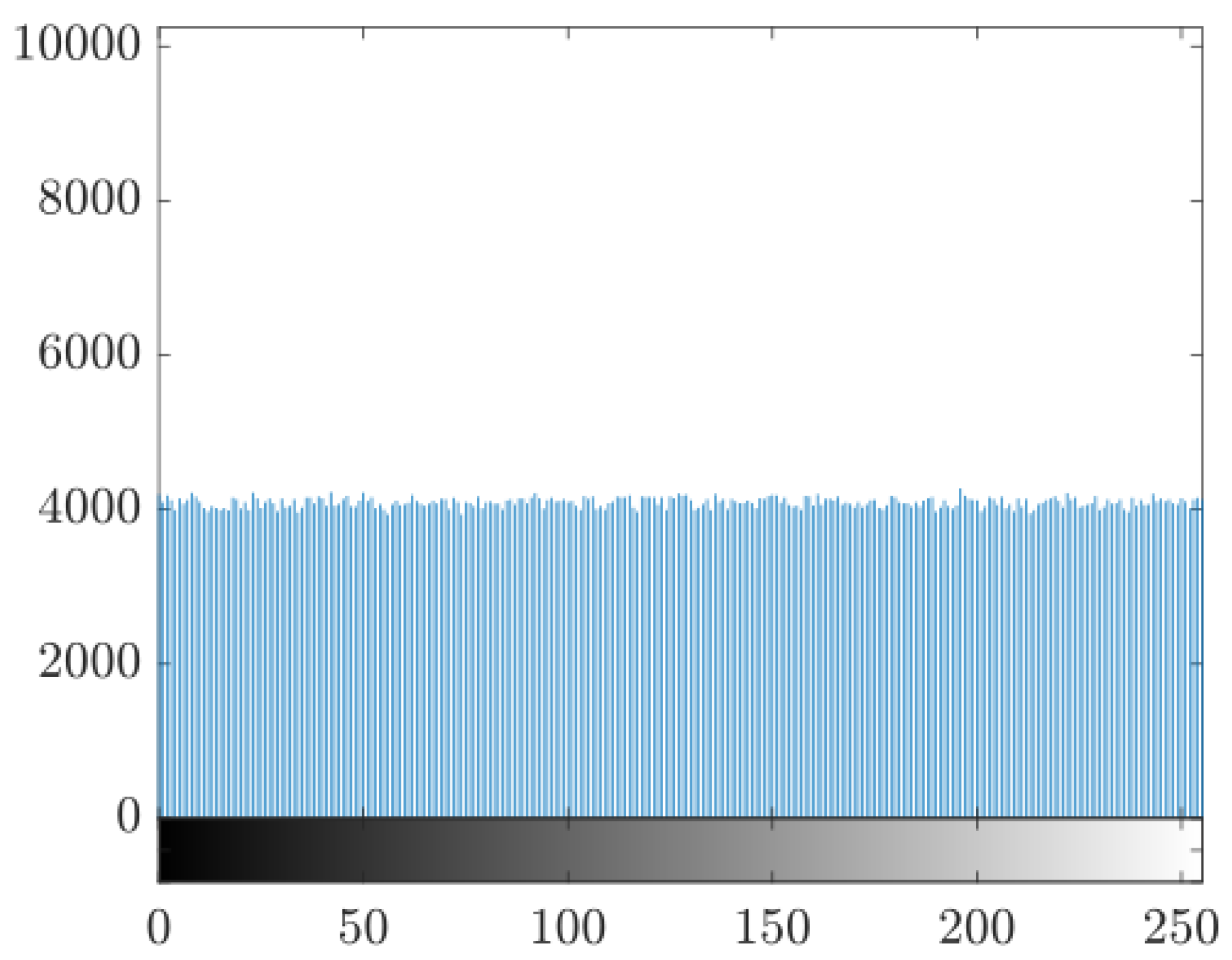

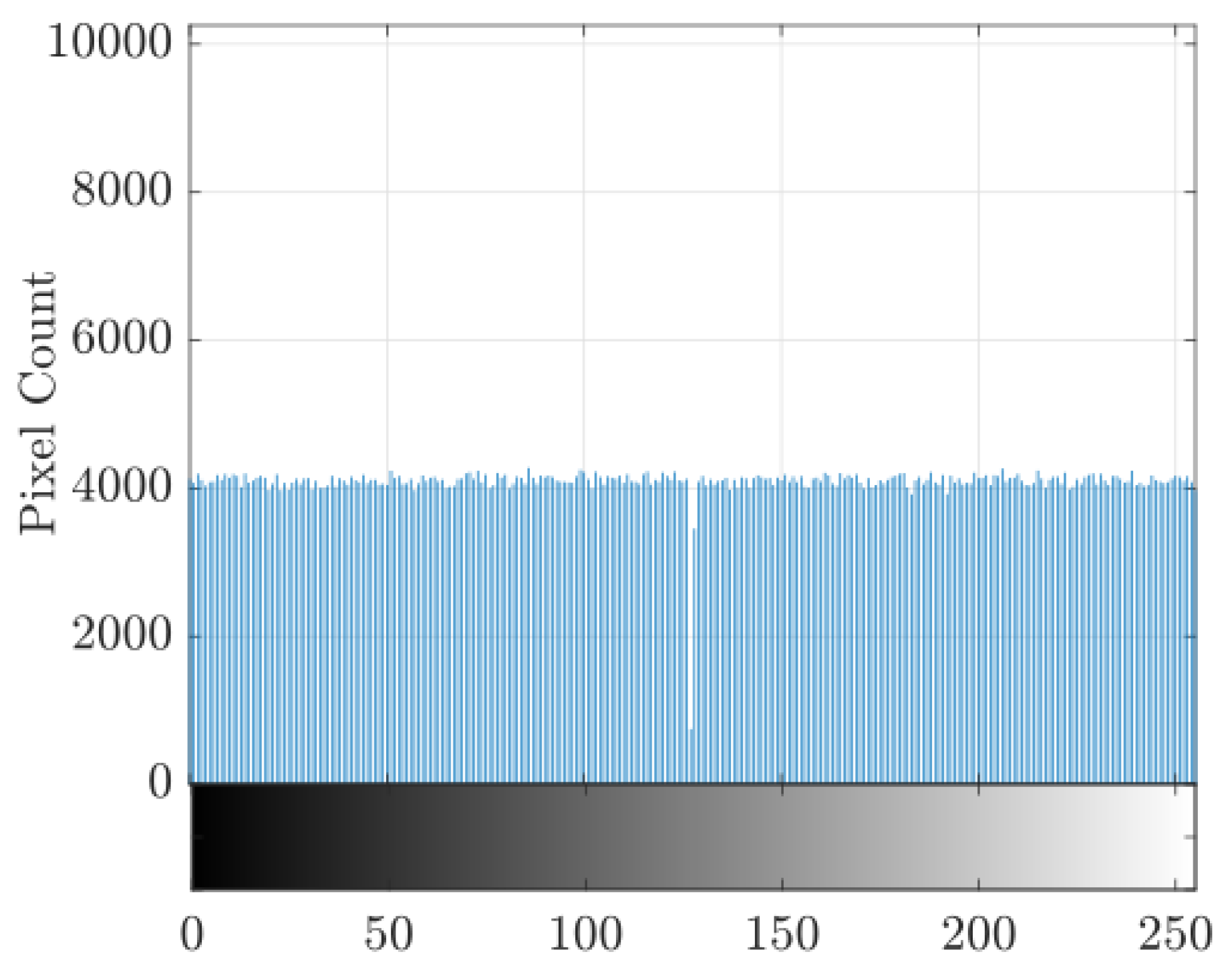

Figure 15 shows the histogram of the encrypted image (for the image in

Figure 7). The histogram of the encrypted image has a mean value of

and a flat or uniform distribution, meaning its pixel values appear with approximately the same frequency, which is evidence that there is no recognizable pattern that suggests any possibility of an attack on the encryption.

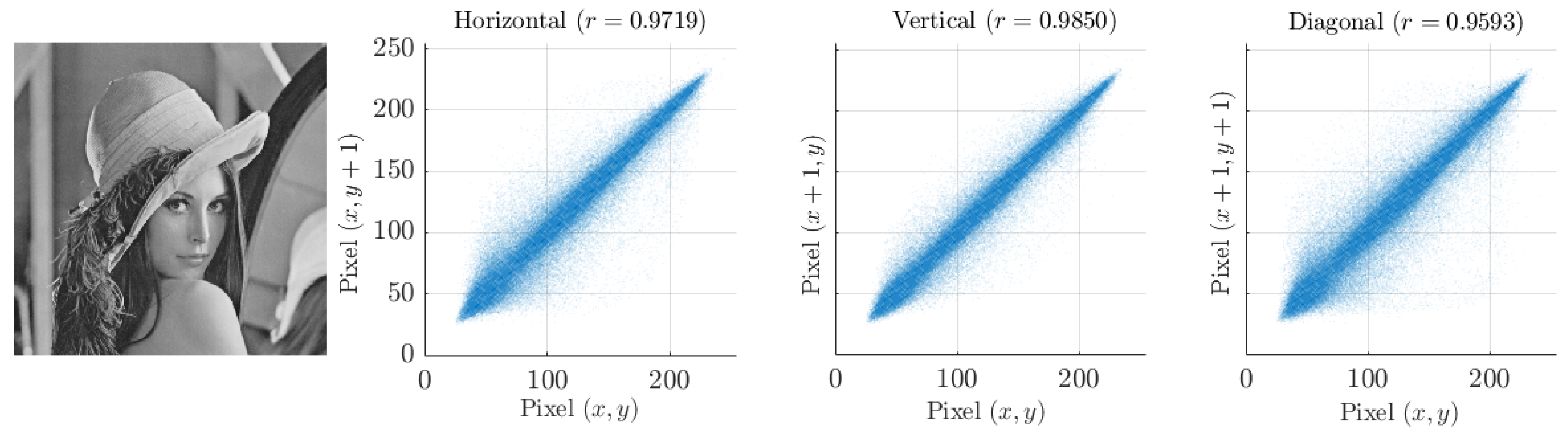

Another objective criterion is the evaluation of the correlation between adjacent pixels in the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions for the first of the four images in

Figure 7 (those in the other three are very similar).

Figure 16 shows the correlations between adjacent pixels, in which the tendency to plot along the diagonal means that the pixels have a similar value. In all three cases, the Pearson correlation coefficient

r tends to 1, implying a high positive correlation.

Figure 17 shows the correlation between adjacent pixels for the encrypted image, for which the coefficient

r tends to zero in all three directions.

3.2. Cryptanalysis

Entropy, as well as the pixel distribution, guarantees that any attack or attempt to decrypt the images cannot be based on simple statistical characteristics. To analyze the security of the proposed method, seven proofs are performed.

3.3. Sensitivity Test

The sensitivity test consists of attempting to extract the images by making very small changes to the encryption key. These attempts are made by modifying all the parameters of the chaotic functions. The first case corresponds to introducing a small change of

to the seed

, for which the mixed image is illustrated in

Figure 18, and the final decrypted image is

Figure 19.

By slightly modifying the parameter

to a very small value, such as

, of the encryption key, the mixed and decrypted images are obtained as images in

Figure 20a,b. By slightly modifying the parameter

, the images as in

Figure 20c,d are obtained.

Figure 21a,b show the result obtained by modifying the seed transient parameter

t in 1 step.

Figure 21a corresponds to the mixed image obtained, while

Figure 21b corresponds to the final decrypted image.

Figure 21c,d show the mixed and final decrypted images obtained by slightly modifying (

) the seed parameter

k.

Since the seed values corresponding to diffusion were modified in the previous analysis, the effect of modifying the parameters that only affect the confusion stage will be analyzed below, so that what is affected is the information recovery process from the mixed matrix.

Figure 22 illustrates the effects of modifying the seed in its parameters

.

Figure 22a,

Figure 22b,

Figure 22c and

k Figure 22d, altering them in the same minimal quantities (

). In all cases, the impossibility of recovering the original images is observed.

3.3.1. Numerical Stability and Chaotic Dynamics

Regarding sensitivity to initial conditions, the delta-kicked oscillator exhibits robust chaotic behavior under parameter variation, characterized by positive Lyapunov exponents and area-preserving dynamics. To demonstrate this sensitivity, a small A perturbation of

was applied to the initial state,

Figure 23. The resulting separation

grows approximately exponentially, with an average logarithmic slope of

. This result reveals an extreme sensitivity to initial conditions, consistent with the principle of chaotic dependence, whereby small changes in the initial key or in the control parameters (

k,

) lead to entirely different output sequences, see the repository [

22].

Comparisons performed under double, single, and quantized (fixed-point) arithmetic reveal that the chaotic dynamics persist with negligible precision loss,

Figure 24. The estimated Lyapunov exponent remains nearly constant (

), and no periodic cycles were observed within

iterations. These findings confirm that the generator maintains numerical stability and robustness, making it suitable for cryptographic applications. The pseudo-random sequences produced remain unpredictable, non-repetitive, and highly sensitive to minute variations in the

key + salt.

3.3.2. Key Security and Brute-Force Resistance

The security of the derived key was assessed both theoretically and experimentally. Key derivation employs PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256 with a four-word salt and 200,000 iterations, ensuring uniform bit dispersion across the 256-bit output while preserving the input entropy. In large-scale simulations using randomly generated key–salt pairs (with 1,000 iterations for computational tractability), no collisions were observed and the empirical entropy was bits/byte, indicating an injective, collision-resistant mapping.

Theoretical brute-force estimates produce infeasible attack times even for extreme adversarial capabilities: years at attempts/s, years at attempts/s, and years at attempts/s. PBKDF2’s iteration count adds substantial computational hardness to each guess, markedly slowing large-scale brute-force campaigns. Although PBKDF2 does not increase the entropy of a human-chosen password, it greatly raises the cost per attempt; the public salt prevents reusable precomputation (e.g., rainbow tables), and if the salt is incorporated into the secret material it would further enlarge the effective search space.

3.3.3. Resistance to Known-Plaintext and Chosen-Plaintext Attacks

The robustness of the proposed chaotic encryption scheme was evaluated under both known-plaintext (KPA) and chosen-plaintext (CPA) scenarios. In the KPA assessment, comparative analyses between the original and encrypted images confirmed complete statistical independence. Using identical keys and parameters, a plaintext–ciphertext pair was generated, and the effective diffusion mask was computed as , where C and P denote the ciphered and original images, respectively.

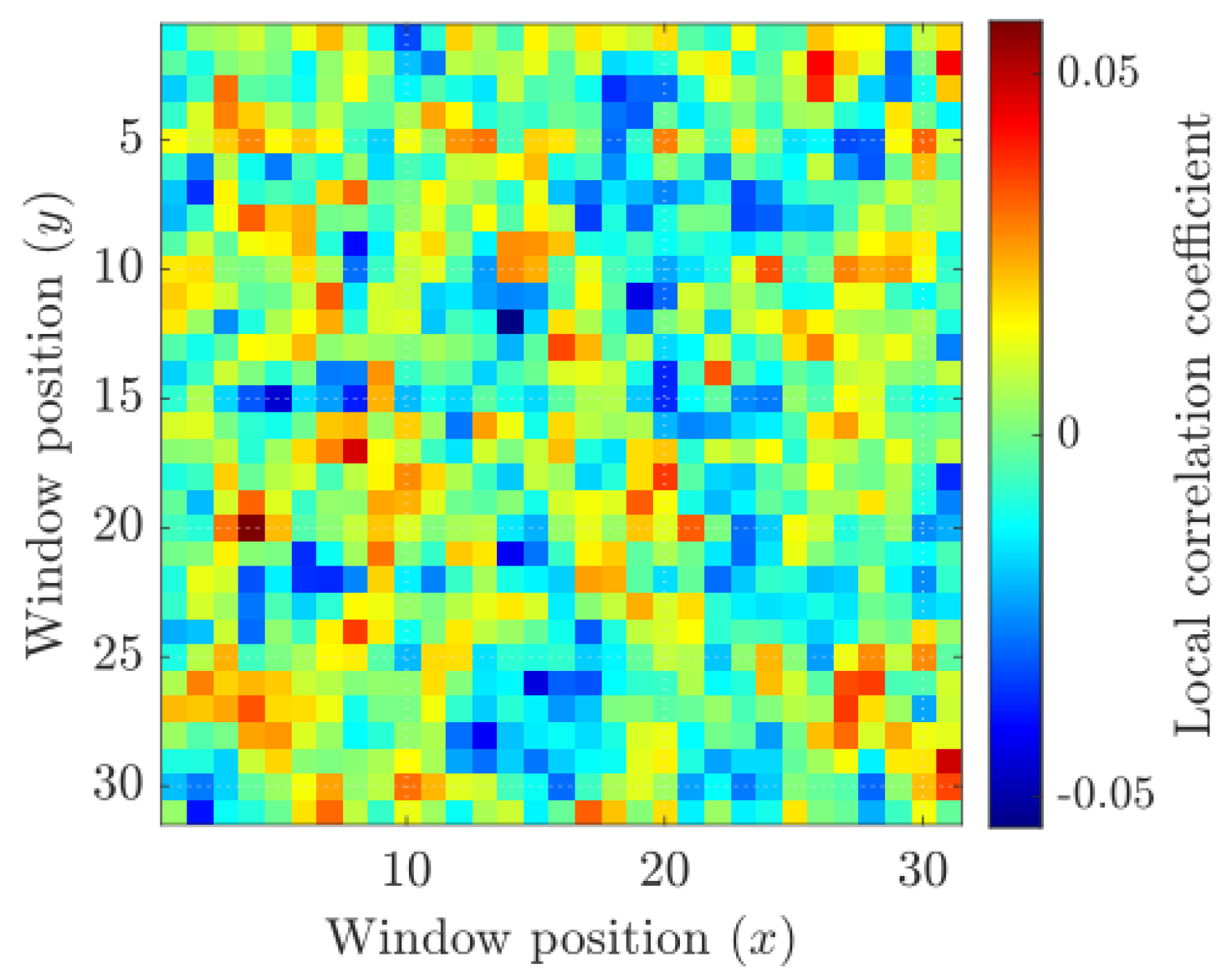

The Pearson correlation coefficient between plaintext and ciphertext pixels was

,

Figure 25, and local correlations over

sliding windows remained within

, confirming the absence of linear or structural dependencies. The diffusion-mask histogram,

Figure 26 exhibited a uniform distribution over

with a Shannon entropy of

bits/byte, near the theoretical limit of 8 bits/byte. These results demonstrate complete confusion and diffusion in the Shannon sense and validate the pseudo-randomness of the delta-kicked oscillator.

A chosen-plaintext attack was implemented using MATLAB routines developed for this study, see data availability. Six controlled input patterns with distinct spatial structures in the repository [

22] were encrypted under identical PBKDF2–HMAC–SHA256 parameters. For each case, the correlation between the estimated diffusion mask

M and its plaintext

P remained on the order of

, indicating negligible dependence. Even for structured or constant inputs, no deterministic features could be inferred from the ciphertext.

Together, these findings confirm that the proposed system maintains statistical independence between plaintext and ciphertext domains and is resistant to both known- and chosen-plaintext attacks. The modular diffusion and dual-seed key derivation ensure unpredictable, noise-like outputs even when the encryption algorithm is fully disclosed, thus satisfying Shannon’s secrecy criterion.

3.3.4. Differential Attack and NPCR–UACI Metrics

A classical way to evaluate the security of an image encryption algorithm is by testing its ability to propagate small variations in the plaintext across the entire ciphertext. This property, known as diffusion, is quantitatively assessed using the standard metrics NPCR (Number of Pixels Change Rate) and UACI (Unified Average Changing Intensity). These measures evaluate the system’s sensitivity to minute perturbations under identical key and salt conditions.

In this stage, differential tests were conducted using a custom MATLAB routine (NPCR_UACI_final.m, see Data Availability) implementing the complete encryption scheme. For each trial, two

images differing by only one pixel (

) at random positions were encrypted using the same key derived via PBKDF2–HMAC–SHA256, ensuring identical chaotic sequences and diffusion masks. The individual and mean results for five encryption trials are summarized in

Table 2. The average NPCR value of

indicates that modifying a single pixel in the plaintext image changes more than

of the ciphertext pixels, demonstrating excellent global diffusion. Similarly, the UACI value of

, very close to the theoretical optimum of

for 8-bit images, confirms that the intensity variations in the encrypted image are uniform and statistically balanced.

These results are in line with those reported in previous studies on chaotic encryption, indicating that the proposed modular-sum diffusion mechanism provides strong diffusion capability. The mechanism, controlled by the pseudo-random sequence generated through the CPMfun function, see Data Availability, further validates the robustness of the proposed approach. Overall, the findings confirm that the encryption method satisfies Shannon’s second condition of complete diffusion. The combination of the chaotic map and the key derived via the KDF ensures efficient information dispersion, making the system highly resistant to differential attacks and exhibiting an error-propagation behavior consistent with modern cryptographic systems.

4. Conclusions

In this work, an image encryption mechanism has been presented that combines the strength of the deterministic dynamics of chaotic delta-kicked oscillator type functions with a key derivation function. By integrating PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256 with a personalized four-word salt, the system transforms human-readable passwords into 256-bit entropy sources, ensuring unique seeds for every execution. The dual-block design of 96 digits effectively decouples confusion and diffusion, producing independent chaotic sequences. The experimental results confirm statistical uniformity (entropy ), near-zero correlations, and full diffusion (NPCR , UACI ). The recovered image exhibits no degradation, achieving a structural similarity index (SSIM) of . Sensitivity and cryptanalysis tests, both known and chosen plaintext attacks, demonstrate resistance to differential and structural attacks. The model maintains compatibility with standard MATLAB arithmetic and achieves reversibility with minimal numerical drift.

The next step is to fully develop the adaptability of the image encryptor and validate it for RGB images of any size. Additional analyses can also be included, such as extension to multidimensional chaotic maps to increase parallel performance. The validation results should ultimately lead to an application that functions as a high-security image encryptor, beneficial to any user, and computationally efficient as a modern, privacy-preserving image encryption system.

Author Contributions

J.V. was responsible for the conceptualization, methodology, software development, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, visualization, supervision, and project admin-istration. M.L., H.D.S., C.M.A., and L.F.D. contributed to the validation and review of the manuscript. Specifically, M.L. and C.M.A. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the chaotic system components; H.D.S. contributed to the development and discussion of the manuscript; and L.F.D. contributed to the discussion of results and implementation of the computational programs. Writing—original draft preparation, J.V.; writing—review and editing, M.L., H.D.S., C.M.A., and L.F.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data, source codes, and supplementary materials supporting the findings of this study are openly available in a public GitHub repository at the site

https://github.com/xavierdelafontaine-boop/Image_Encryption_Real_Plane_01. The core source code used for the main simulations is not publicly released due to ongoing development and intellectual property restrictions, but it can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

The authors used OpenAI’s GPT-5 model for language refinement and minor technical assistance under full author supervision. All prompts and supporting materials are available in the GitHub repository referenced in the Data Availability Statement. GPT-5 had no role in the research design, data interpretation, or scientific conclusions.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KDF |

Key Derivation Function |

| SSIM |

Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| NPCR |

Number of Pixels Change Rate |

| UACI |

Unified Average Changing Intensity |

| GL |

Gray Level |

| PP |

Partition-permutation matrix |

References

- Alshahrani, A.A.; Jaha, E.S.; Alowidi, N. Fusion of Hash-Based Hard and Soft Biometrics for Enhancing Face Image Database Search and Retrieval. Computers, Materials and Continua 2023, 77, 3489–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Cui, H.; Tang, Z.; Li, Y. A Review of Homomorphic Encryption for Privacy-Preserving Biometrics. Sensors número no especificado. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, Z. A Secure and Efficient Face Template Protection Scheme Based on Chaos. Journal of Information Security and Applications 2025, 93, 104111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hyari, A.; Abu-Faraj, M.; Obimbo, C.; Alazab, M. Chaotic Hénon–Logistic Map Integration: A Powerful Approach for Safeguarding Digital Images. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisha, U.; Chandana, B.S. Privacy Preserving Image Encryption with Optimal Deep Transfer Learning Based Accident Severity Classification Model. Sensors 2023, 23, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barik, K.; Misra, S.; Sanz, L.F.; Chockalingam, S. Enhancing Image Data Security Using the APFB Model. Connection Science 2024, 36, 2379275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Wen, W. A Privacy-Preserving Image Retrieval Scheme with Access Control Based on Searchable Encryption in Media Cloud. Cybersecurity 2024, 7, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, N.; Dua, M. A Novel One-Dimensional Cosine within Sine Chaotic Map and Novel Permutation–Diffusion Based Medical Image Encryption. Nonlinear Dynamics 2025, 113, 4839–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Bhaya, C.; Pal, A.K.; Singh, A.K. A Novel Binary Operator for Designing Medical and Natural Image Cryptosystems. Signal Processing: Image Communication 2021, 98, 116377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; Wang, X.; Xian, Y. Image Encryption Algorithm Based on a 2D-CLSS Hyperchaotic Map Using Simultaneous Permutation and Diffusion. Information Sciences 2022, 605, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, K.; Te, R.; Yan, F. Robust Image Encryption with 2D Hyperchaotic Map and Dynamic DNA-Zigzag Encoding. Entropy 2025, 27, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umar, T.; Nadeem, M.; Anwer, F. Chaos Based Image Encryption Scheme to Secure Sensitive Multimedia Content in Cloud Storage. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 257, 125050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexan, W.; Elbeltagy, M.; Aboshousha, A. RGB Image Encryption through Cellular Automata, S-Box and the Lorenz System. Symmetry 2022, 14, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, M.U.; Shah, T.; Ali, A. Multiple-Image Encryption Algorithm Based on S-Boxes and DNA Sequences. Signal Processing: Image Communication 2025, 138, 117353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Hao, W.; Zhou, A.; Ma, J. Optical Color Image Encryption Algorithm Based on Two-Dimensional Quantum Walking. Electronics 2024, 13, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Su, R. A Novel Virtual Optical Image Encryption Scheme Created by Combining Chaotic S-Box with Double Random Phase Encoding. Sensors 2022, 22, 5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, H. Chaotic Medical Image Encryption Method Using Attention Mechanism Fusion ResNet Model. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2023, 17, 1226154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Du, J.; Fu, C.; Song, W. Image Encryption Algorithm Combining Chaotic Image Encryption and Convolutional Neural Network. Electronics 2023, 12, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullaev, S. S. Canonical Stochastic Web Map. Physical Review E 2007, 76, 026216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.R.R.; de Matos Filho, R.L.; Davidovich, L. Environmental Effects in the Quantum-Classical Transition for the Delta-Kicked Harmonic Oscillator. Physical Review E 2004, 70, 026211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieci, L.; Van Vleck, E.S. Computation of a Few Lyapunov Exponents for Continuous and Discrete Dynamical Systems. Applied Numerical Mathematics 1995, 17, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Fontaine, X. Image Encryption Real Plane 01: Source Code and Dataset. GitHub repository. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/xavierdelafontaine-boop/Image_Encryption_Real_Plane_01 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Abusham, E.; Ibrahim, B.; Zia, K.; Rehman, M. Facial Image Encryption for Secure Face Recognition System. Electronics 2023, 12, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, R.B.; Singh, U. A Review on Applications of Chaotic Maps in Pseudo-Random Number Generators and Encryption. Annals of Data Science 2024, 11, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, B.; Kuppusamy, K.; Senthilrajan, A. Dynamic DNA Cryptography-Based Image Encryption Scheme Using Multiple Chaotic Maps and SHA-256 Hash Function. Optik 2023, 289, 171253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, A.; Mehmood, A.; Alawida, M.; Khan, A.N. Enhancing Privacy in Data Transmission between IoT Devices: A Robust Encryption and Embedding Framework for Secure and Meaningful Image Communication. Journal of Information Security and Applications 2025, 93, 104112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, L. Chaos-Based Image Encryption: Review, Application, and Challenges. Mathematics número no especificado. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Zhao, B. DNA Image Encryption Algorithm Based on Serrated Spiral Scrambling and Cross Bit Plane. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2023, 35, 101858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Lu, D. An Efficient Image Encryption Algorithm Based on S-Box and DNA Code. Measurement: Sensors 2023, 29, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Phase space density for , and .

Figure 1.

Phase space density for , and .

Figure 2.

Lyapunov exponent onvergence: , , sum=.

Figure 2.

Lyapunov exponent onvergence: , , sum=.

Figure 8.

Subdivision of each partition into 4 regions of pixels per side. Source: The authors.

Figure 8.

Subdivision of each partition into 4 regions of pixels per side. Source: The authors.

Figure 11.

Image obtained after the diffusion process. Source: The authors.

Figure 11.

Image obtained after the diffusion process. Source: The authors.

Figure 12.

Assignment of inversions to the permutations for each digit. Source: The authors.

Figure 12.

Assignment of inversions to the permutations for each digit. Source: The authors.

Figure 13.

Recovered decrypted image. Source: the authors.

Figure 13.

Recovered decrypted image. Source: the authors.

Figure 14.

Unencrypted image histogram. Histograms of the unencrypted and encrypted images. Source: The authors.

Figure 14.

Unencrypted image histogram. Histograms of the unencrypted and encrypted images. Source: The authors.

Figure 15.

Encrypted image histogram. Histograms of the unencrypted and encrypted images. Source: The authors.

Figure 15.

Encrypted image histogram. Histograms of the unencrypted and encrypted images. Source: The authors.

Figure 16.

Correlations of adjacent pixels for the unencrypted image. Source: The authors.

Figure 16.

Correlations of adjacent pixels for the unencrypted image. Source: The authors.

Figure 17.

Correlations of adjacent pixels for the encrypted image. Source: The authors.

Figure 17.

Correlations of adjacent pixels for the encrypted image. Source: The authors.

Figure 18.

Mixed image obtained. Images obtained by varying the first parameter of the seed of chaotic functions. Source: The authors.

Figure 18.

Mixed image obtained. Images obtained by varying the first parameter of the seed of chaotic functions. Source: The authors.

Figure 19.

Final decrypted image obtained. Images obtained by varying the first parameter of the seed of chaotic functions. Source: The authors.

Figure 19.

Final decrypted image obtained. Images obtained by varying the first parameter of the seed of chaotic functions. Source: The authors.

Figure 20.

Images obtained by slightly varying the parameters and of the seed. Source: The authors.

Figure 20.

Images obtained by slightly varying the parameters and of the seed. Source: The authors.

Figure 21.

Images obtained by slightly varying the parameters t and k. Source: The authors.

Figure 21.

Images obtained by slightly varying the parameters t and k. Source: The authors.

Figure 22.

Images obtained by minimally varying the parameters (a), (b), (c) and k (d). Source: The authors.

Figure 22.

Images obtained by minimally varying the parameters (a), (b), (c) and k (d). Source: The authors.

Figure 23.

Exponential divergence under a perturbation . Sensitivity to initial perturbation (), slope.

Figure 23.

Exponential divergence under a perturbation . Sensitivity to initial perturbation (), slope.

Figure 24.

Lyapunov exponents and trajectory deviations under double, single, and fixed-point arithmetic, showing preserved chaotic stability across precision levels. (Top) Lyapunov exponents by precision. (Bottom) Divergence vs double (fixed grid=).

Figure 24.

Lyapunov exponents and trajectory deviations under double, single, and fixed-point arithmetic, showing preserved chaotic stability across precision levels. (Top) Lyapunov exponents by precision. (Bottom) Divergence vs double (fixed grid=).

Figure 25.

Local Pearson correlation map computed over sliding windows between the plaintext and ciphertext images.

Figure 25.

Local Pearson correlation map computed over sliding windows between the plaintext and ciphertext images.

Figure 26.

Histogram of diffusion mask intensities.

Figure 26.

Histogram of diffusion mask intensities.

Table 1.

PP matrix of partitions and permutations. Source: The authors.

Table 1.

PP matrix of partitions and permutations. Source: The authors.

| 3 |

3 |

9 |

7 |

0 |

5 |

8 |

7 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

| 4 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

9 |

7 |

9 |

7 |

6 |

0 |

2 |

7 |

3 |

3 |

7 |

6 |

Table 2.

NPCR and UACI metrics. Source: The authors.

Table 2.

NPCR and UACI metrics. Source: The authors.

| Trial |

|

|

| 1 |

99.5981 |

33.3347 |

| 2 |

99.6030 |

33.4018 |

| 3 |

99.6139 |

33.4298 |

| 4 |

99.6036 |

33.4103 |

| 5 |

99.6072 |

35.7299 |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).