Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Culture and siRNA Transfection

2.3. Incorporation of [35S]Sulfate into GAGs

2.4. Quantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.5. PG Core Protein Expression and Western Blotting Analysis

2.6. Intracellular Accumulation of Gold Atoms

2.7. Arf6 Activation (GTP-Bound Arf6 Pulldown) Assay

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

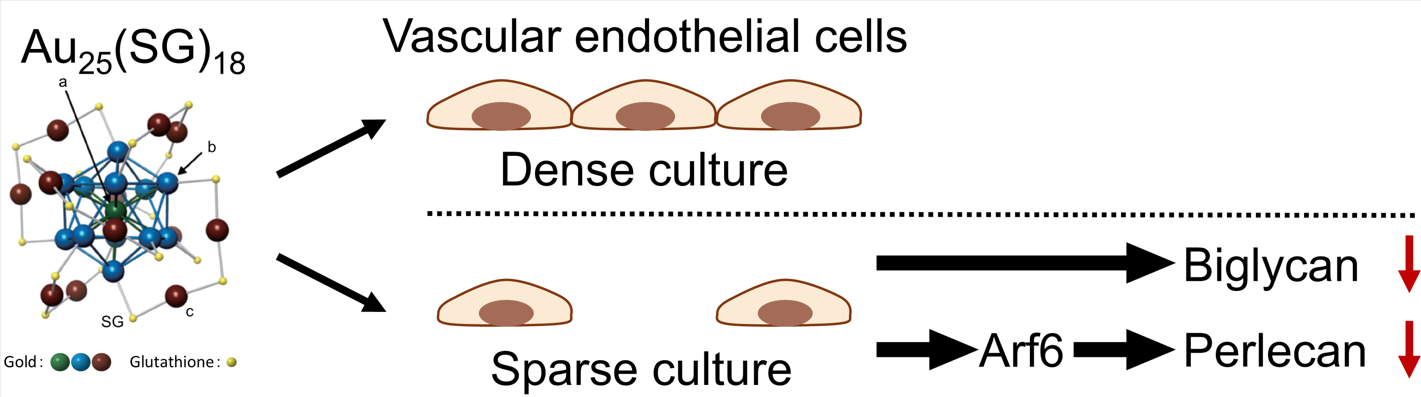

3.1. Au25(SG)18 Suppresses PG Synthesis in Sparse Cultures of Vascular Endothelial Cells

3.2. Perlecan and Biglycan Expression Is Suppressed by Au25(SG)18 in Sparse Cultures of Vascular Endothelial Cells

3.3. Au25(SG)18 Does Not Affect the mRNA Expression Levels of Perlecan and Biglycan in Dense Cultures of Vascular Endothelial Cells, Even at High Concentrations

3.4. Role of Arf6 in the Regulation of Cell Density-Dependent PG Synthesis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Arf6 | ADP-ribosylation factor 6 |

| BCA | bicinchoninic acid |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| DSPG | Dermatan sulfate proteoglycan |

| FGF | fibroblast growth factor |

| GAG | Glycosaminoglycan |

| GAP | GTPase activating protein |

| GEF | guanine nucleotide exchange factor |

| HSPG | Heparan sulfate proteoglycan |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| PG | Proteoglycan |

| SDS | sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| TGF | Transforming growth factor |

References

- Baldwin, A. L.; Thurston, G. Mechanics of endothelial cell architecture and vascular permeability. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2001, 29, 247–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, J. R.; Dreyer, B. E.; Stemerman, M. B.; Pitlick, F. A. Tissue-factor coagulant activity of cultured human endothelial and smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts. Blood 1977, 50, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncada, S.; Gryglewski, R.; Bunting, S.; Vane, J. R. An enzyme isolated from arteries transforms prostaglandin endoperoxides to an unstable substance that inhibits platelet aggregation. Nature 1976, 263, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmon, C. T.; Owen, W. G. Identification of an endothelial cell cofactor for thrombin-catalyzed activation of protein C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 2249–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E. G.; Loskutoff, D. J. Cultured bovine endothelial cells produce both urokinase and tissue-type plasminogen activators. J. Cell Biol. 1982, 94, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mourik, J. A.; Lawrence, D. A.; Loskutoff, D. J. Purification of an inhibitor of plasminogen activator (antiactivator) synthesized by endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 14914–14921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoslahti, E. Structure and biology of proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1988, 4, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, C.; Deng, X.; Fujiwara, Y.; Kaji, T. Proteoglycans predominantly synthesized by human brain microvascular endothelial cells in culture are perlecan and biglycan. J. Health Sci. 2005, 51, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saku, T.; Furthmayr, H. Characterization of the major heparan sulfate proteoglycan secreted by bovine aortic endothelial cells in culture. Homology to the large molecular weight molecule of basement membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 3514–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Shworak, N. W.; Rosenberg, R. D. Molecular cloning and expression of two distinct cDNA-encoding heparan sulfate proteoglycan core proteins from a rat endothelial cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 4870–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järveläinen, H. T.; Kinsella, M. G.; Wight, T. N.; Sandell, L. J. Differential expression of small chondroitin/dermatan sulfate proteoglycans, PG-I/biglycan and PG-II/decorin, by vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells in culture. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 23274–23281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Agostini, A. I.; Watkins, S. C.; Slayter, H. S.; Youssoufian, H.; Rosenberg, R. D. Localization of anticoagulantly active heparan sulfate proteoglycans in vascular endothelium: Antithrombin binding on cultured endothelial cells and perfused rat aorta. J. Cell Biol. 1990, 111, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T. Targeted gene disruption of natural anticoagulant proteins in mice. Int. J. Hematol. 2002, 76, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, G.; Cassiman, J. J.; Van den Berghe, H.; Vermylen, J.; David, G. Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans from human vascular endothelial cells. Core protein characterization and antithrombin III binding properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 20435–20443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whinna, H. C.; Choi, H. U.; Rosenberg, L. C.; Church, F. C. Interaction of heparin cofactor II with biglycan and decorin. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 3920–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, T.; Yamada, A.; Miyajima, S.; Yamamoto, C.; Fujiwara, Y.; Wight, T. N.; Kinsella, M. G. Cell density-dependent regulation of proteoglycan synthesis by transforming growth factor-β1 in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 1463–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Yoshida, E.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yamamoto, C.; Kaji, T. Transforming growth factor-β1 modulates the expression of syndecan-4 in cultured vascular endothelial cells in a biphasic manner. J. Cell Biochem. 2017, 118, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, M. G.; Tsoi, C. K.; Järveläinen, H. T.; Wight, T. N. Selective expression and processing of biglycan during migration of bovine aortic endothelial cells. The role of endogenous basic fibroblast growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, T.; Yamamoto, C.; Oh-i, M.; Nishida, T.; Takigawa, M. Differential regulation of biglycan and decorin synthesis by connective tissue growth factor in cultured vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 322, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, T.; Yamamoto, C.; Oh-i, M.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yamazaki, Y.; Morita, T.; Plaas, A. H.; Wight, T. N. The vascular endothelial growth factor microvascular endothelial cells. VEGF165 induces perlecan synthesis via VEGF receptor-2 in cultured human brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006, 1760, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Lipke, D. W.; McClain, C. J.; Hennig, B. Tumor necrosis factor reduces proteoglycan synthesis in cultured endothelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1995, 162, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skop, B.; Sobczak, A.; Drózdz, M.; Kotrys-Puchalska, E. Comparison of the action of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and interleukin-1 beta on matrix metabolism in the culture of porcine endothelial cells. Biochimie 1996, 78, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Yabushita, S.; Yamamoto, C.; Kaji, T. Cell density-dependent fibroblast growth factor-2 signaling regulates syndecan-4 expression in cultured vascular endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawara, S.; Yamamoto, C.; Fujiwara, Y.; Sakamoto, M.; Kaji, T. Cadmium induces the production of high molecular weight heparan sulfate proteoglycan molecules in cultured vascular endothelial cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1997, 3, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Kaji, T. Lead inhibits the core protein synthesis of a large heparan sulfate proteoglycan perlecan by proliferating vascular endothelial cells in culture. Toxicology 1999, 133, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Kumagai, R.; Tanaka, T.; Nakano, T.; Fujie, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yamamoto, C.; Kaji, T. Lead suppresses perlecan expression via EGFR-ERK1/2-COX-2-PGI2 pathway in cultured bovine vascular endothelial cells. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2023, 48, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Kaji, T. Possible mechanism for lead inhibition of vascular endothelial cell proliferation: a lower response to basic fibroblast growth factor through inhibition of heparan sulfate synthesis. Toxicology 1999, 133, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Tatsuishi, H.; Banno, T.; Fujie, T.; Yamamoto, C.; Naka, H.; Kaji, T. Copper(II) bis(diethyldithiocarbamate) induces the expression of syndecan-4, a transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan, via p38 MAPK activation in vascular endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Kojima, T.; Matsuzaki, H.; Nakamura, T.; Yoshida, E.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yamamoto, C.; Saito, S.; Kaji, T. Induction of syndecan-4 by organic–inorganic hybrid molecules with a 1,10-phenanthroline structure in cultured vascular endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Sakamaki, S.; Ikeda, A.; Nakamura, T.; Yamamoto, C.; Kaji, T. Cell density-dependent modulation of perlecan synthesis by dichloro(2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline)zinc(II) in vascular endothelial cells. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 45, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Konishi, T.; Yasuike, S.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yamamoto, C.; Kaji, T. Sb-Phenyl-N-methyl-5,6,7,12-tetrahydrodibenz[c,f][1,5]azastibocine induces perlecan core protein synthesis in cultured vascular endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Qian, H.; Drake, B. A.; Jin, R. Atomically precise Au25(SR)18 nanoparticles as catalysts for the selective hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated ketones and aldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1295–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazoe, S.; Koyasu, K.; Tsukuda, T. Nonscalable oxidation catalysis of gold clusters. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoppe, S.; Dolamic, I.; Dass, A.; Bürgi, T. Separation of enantiomers and CD spectra of Au40(SCH2CH2Ph)24: spectroscopic evidence for intrinsic chirality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7589–7591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, S.; Beeby, A.; FitzGerald, S.; El-Sayed, M. A.; Schaaff, T. G.; Whetten, R. L. Visible to infrared luminescence from a 28-atom gold cluster. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002, 106, 3410–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jin, R. On the ligand’s role in the fluorescence of gold nanoclusters. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2568–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Aikens, C. M.; Hendrich, M. P.; Gupta, R.; Qian, H.; Schatz, G. C.; Jin, R. Reversible switching of magnetism in thiolate-protected Au25 superatoms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2490–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonello, S.; Perera, N. V.; Ruzzi, M.; Gascon, J. A.; Maran, F. Interplay of charge state, lability, and magnetism in the molecule-like Au25(SR)18 cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 15585–15594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazoe, S.; Takano, S.; Kurashige, W.; Yokoyama, T.; Nitta, K.; Negishi, Y.; Tsukuda, T. Hierarchy of bond stiffnesses within icosahedral-based gold clusters protected by thiolates. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, Y.; Sakamoto, C.; Ohyama, T.; Tsukuda, T. Synthesis and the origin of the stability of thiolate-protected Au130 and Au187 clusters. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 1624–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, T.; Shibuta, M.; Tsunoyama, H.; Negishi, Y.; Eguchi, T.; Nakajima, A. Size and structure dependence of electronic states in thiolate-protected gold nanoclusters of Au25(SR)18, Au38(SR)24, and Au144(SR)60. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013, 117, 3674–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, Y.; Nobusada, K.; Tsukuda, T. Glutathione-protected gold clusters revisited: bridging the gap between gold(I)–thiolate complexes and thiolate-protected gold nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5261–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Gayathri, C.; Gil, R. R.; Jin, R. Probing the structure and charge state of glutathione-capped Au25(SG)18 clusters by NMR and mass spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6535–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shichibu, Y.; Negishi, Y.; Tsukuda, T.; Teranishi, T. Large-scale synthesis of thiolated Au25 clusters via ligand exchange reactions of phosphine-stabilized Au11 clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13464–13465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Sakuma, M.; Fujie, T.; Kaji, T.; Yamamoto, C. Cadmium induces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 via Smad2/3 signaling pathway in human endothelial EA.hy926 cells. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2021, 46, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Saeki, M.; Negishi, Y.; Kaji, T.; Yamamoto, C. Cell density-dependent accumulation of low polarity gold nanocluster in cultured vascular endothelial cells. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 45, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennerberg, K.; Rossman, K. L.; Der, C. J. The Ras superfamily at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 843–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Nam, J. M.; Kojima, C.; Mochizuki, N.; Sabe, H. EphA2 engages Git1 to suppress Arf6 activity modulating epithelial cell–cell contacts. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009, 20, 1949–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, R. L.; Parrott, D. P.; Kaplan, S. R.; Fuller, G. C. A mechanism of action of gold sodium thiomalate in diseases characterized by a proliferative synovitis: reversible changes in collagen production in cultured human synovial cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1981, 218, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, A. E.; Walz, D. T.; Batista, V.; Mizraji, M.; Roisman, F.; Misher, A. A.; Auranofin. New oral gold compound for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1976, 35, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storhoff, J. J.; Mirkin, C. A. Programmed materials synthesis with DNA. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 1849–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskerician, G.; Shive, M. S.; Shawgo, R. S.; von Recum, H.; Anderson, J. M.; Cima, M. J.; Langer, R. Biocompatibility and biofouling of MEMS drug delivery devices. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 1959–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Stockmar, F.; Azadfar, N.; Nienhaus, G. U. Intracellular thermometry by using fluorescent gold nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11154–11157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Y.; Wang, C. W.; Yuan, Z. Q.; Chang, H. T. Fluorescent gold nanoclusters: recent advances in sensing and imaging. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. D.; Luo, Z.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Song, S.; Sun, Y.; Fan, S.; Fan, F.; Leong, D. T.; Xie, J. Ultrasmall Au10−12(SG)10−12 nanomolecules for high tumor specificity and cancer radiotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 4565–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R. S.; Day, E. S. Gold nanoparticle-mediated photothermal therapy: applications and opportunities for multimodal cancer treatment. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrault, S. D.; Walkey, C.; Jennings, T.; Fischer, H. C.; Chan, W. C. Mediating tumor targeting efficiency of nanoparticles through design. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, L. Y.; Chan, W. C. Fluorescence-tagged gold nanoparticles for rapidly characterizing the size-dependent biodistribution in tumor models. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2012, 1, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. D.; Wu, D.; Shen, X.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y. M.; Liu, P. X.; Liang, X. J. Size-dependent radiosensitization of PEG-coated gold nanoparticles for cancer radiation therapy. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6408–6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, C. M.; McCusker, C. D.; Yilmaz, T.; Rotello, V. M. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles functionalized with cationic and anionic side chains. Bioconjug. Chem. 2004, 15, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, F.; Cinatl, J.; Kabičková, H.; Kreuter, J.; Stieneker, F. Preparation, characterization and cytotoxicity of methylmethacrylate copolymer nanoparticles with a permanent positive surface charge. Int. J. Pharm. 1997, 157, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Huo, S.; Mizuhara, T.; Das, R.; Lee, Y. W.; Hou, S.; Moyano, D. F.; Duncan, B.; Liang, X. J.; Rotello, V. M. The interplay of size and surface functionality on the cellular uptake of sub-10 nm gold nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2015, 9, 9986–9993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroozandeh, P.; Aziz, A. A. Insight into cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Shang, L.; Nienhaus, G. U. Mechanistic aspects of fluorescent gold nanocluster internalization by live HeLa cells. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 1537–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, E.; Di Fiore, P. P.; Sigismund, S. Endocytic control of signaling at the plasma membrane. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2016, 39, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, K.; Haucke, V. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis: membrane factors pull the trigger. Trends Cell Biol. 2001, 11, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Werling, D.; Hope, J. C.; Taylor, G.; Howard, C. J. Caveolae and caveolin in immune cells: distribution and functions. Trends Immunol. 2002, 23, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamaze, C.; Schmid, S. L. The emergence of clathrin-independent pinocytic pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1995, 7, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucrot, E.; Kirchhausen, T. Endosomal recycling controls plasma membrane area during mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007, 104, 7939–7944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisanti, M. P.; Scherer, P. E.; Vidugiriene, J.; Tang, Z.; Hermanowski-Vosatka, A.; Tu, Y. H.; Cook, R. F.; Sargiacomo, M. Characterization of caveolin-rich membrane domains isolated from an endothelial-rich source: implications for human disease. J. Cell Biol. 1994, 126, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucrot, E.; Howes, M. T.; Kirchhausen, T.; Parton, R. G. Redistribution of caveolae during mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 1965–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinze, C.; Boucrot, E. Endocytosis in proliferating, quiescent and terminally differentiated cells. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs216804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béglé, A.; Tryoen-Tóth, P.; de Barry, J.; Bader, M. F.; Vitale, N. ARF6 regulates the synthesis of fusogenic lipids for calcium-regulated exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 4836–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, P.; Zhang, Z.; Degeest, G.; Mortier, E.; Leenaerts, I.; Coomans, C.; Schulz, J.; N’Kuli, F.; Courtoy, P. J.; David, G. Syndecan recycling is controlled by syntenin-PIP2 interaction and Arf6. Dev. Cell. 2005, 9, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renault, L.; Guibert, B.; Cherfils, J. Structural snapshots of the mechanism and inhibition of a guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Nature 2003, 426, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaschet, J.; Hsu, V. W. Distribution of ARF6 between membrane and cytosol is regulated by its GTPase cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 20040–20045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J. G.; Jackson, C. L. ARF family G proteins and their regulators: roles in membrane transport, development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongu, T.; Kanaho, Y. Activation machinery of the small GTPase Arf6. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2014, 54, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviezer, D.; Hecht, D.; Safran, M.; Eisinger, M.; David, G.; Yayon, A. Perlecan, basal lamina proteoglycan, promotes basic fibroblast growth factor-receptor binding, mitogenesis, and angiogenesis. Cell. 1994, 79, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santy, L. C.; Casanova, J. E. Activation of ARF6 by ARNO stimulates epithelial cell migration through downstream activation of both Rac1 and phospholipase D. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 154, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knizhnik, A. V.; Kovaleva, O. V.; Komelkov, A. V.; Trukhanova, L. S.; Rybko, V. A.; Zborovskaya, I. B.; Tchevkina, E. M. Arf6 promotes cell proliferation via the PLD-mTORC1 and p38MAPK pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 113, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).