1. Introduction

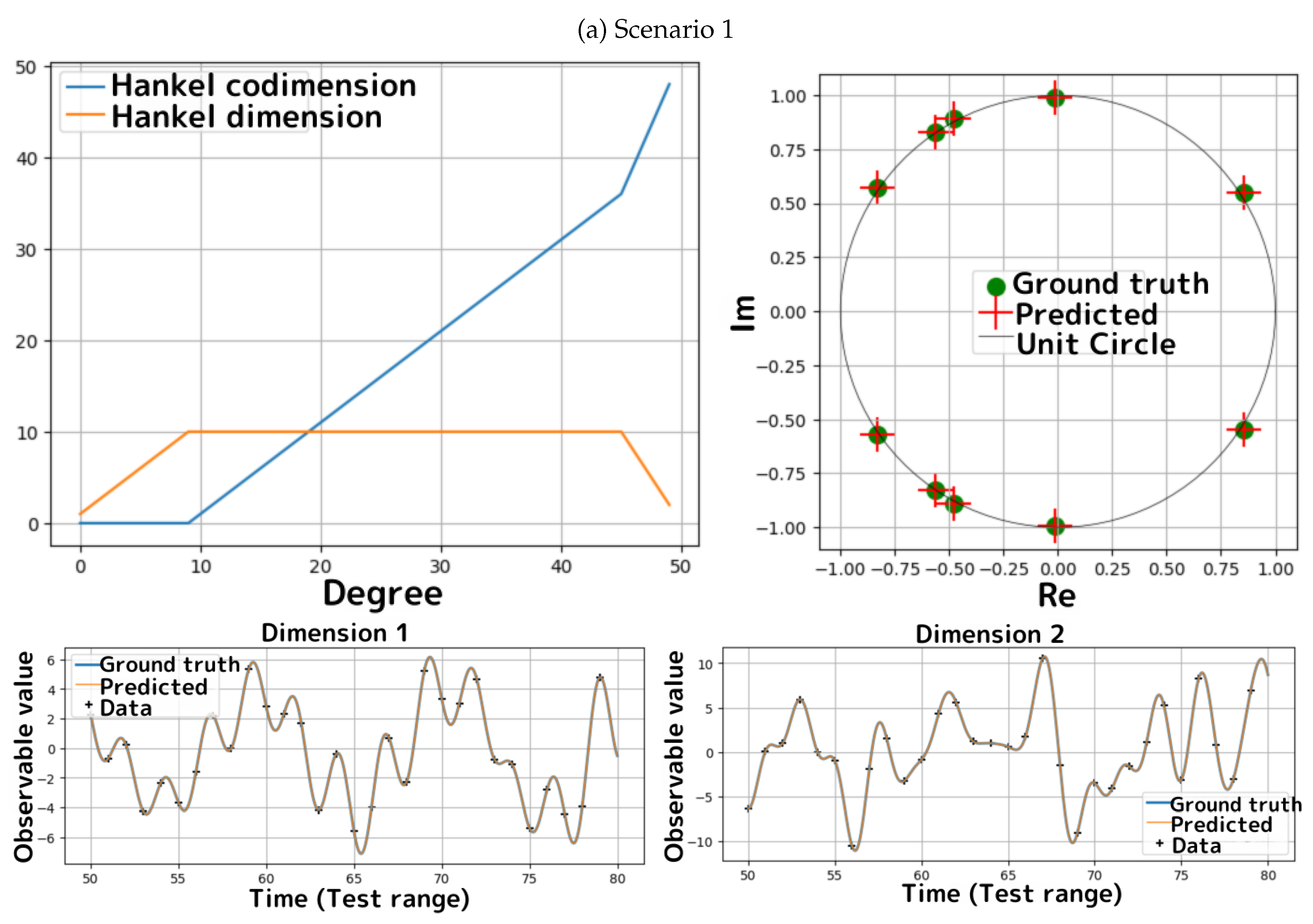

A wide range of natural and social phenomena are observed as superpositions of multiple nonlinear elemental processes. For example, recorded audio signals typically include not only the target speech—for instance, a conversation between individuals—but also various environmental noise components. Similarly, variations in the geomagnetic field arise from both internal processes, such as temporal fluctuations in the Earth’s main magnetic field, and external perturbations, such as solar flares and solar wind. Decomposing such observations into constituent processes and extracting only the components relevant to the study is a fundamental procedure in scientific research. Among such methods, frequency analysis—where time-series data are decomposed into countably (often finitely) many frequency components—plays a central role in data science.

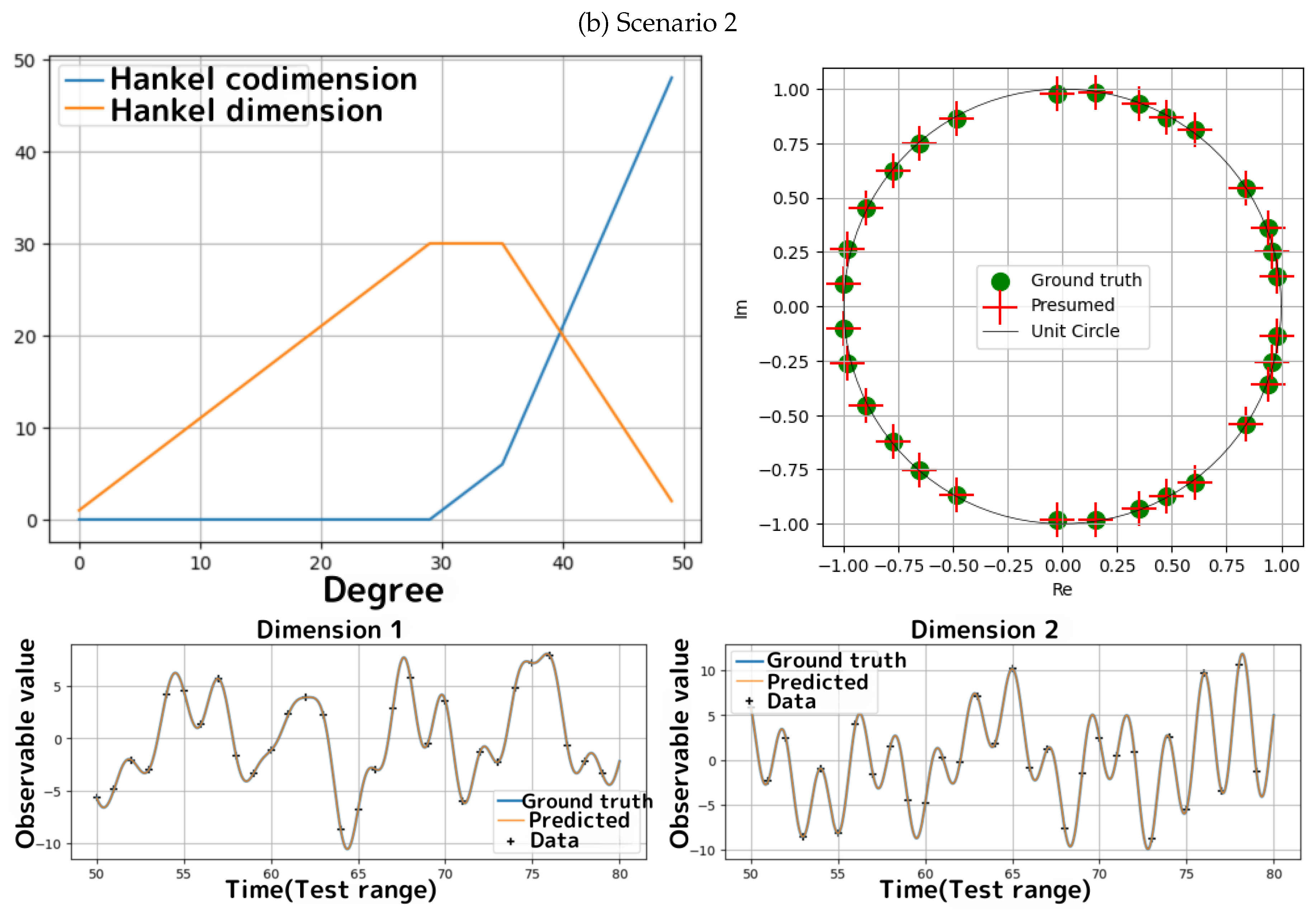

A foundational principle across the natural sciences involves reducing nonlinear phenomena to linear problems, enabling analysis via linear algebra. For instance, kernel methods in machine learning embed data into high-dimensional (often infinite-dimensional Hilbert) spaces to facilitate linear solutions. Likewise, neural networks—which approximate arbitrary continuous (and thus potentially nonlinear) functions via linear combinations followed by nonlinear activations—rely on efficient linear transformations during training. The backpropagation algorithm, essential for learning from large-scale data, exemplifies this reliance.

A well-established and widely applied technique based on this principle is Fourier decomposition, which forms the foundation of frequency analysis across a wide range of fields. Grounded in functional analysis, it represents a function as a linear combination of frequency components, typically expressed in terms of an orthonormal basis of trigonometric functions. This decomposition facilitates tasks such as signal characterization and noise reduction and has found broad applications in speech recognition and compression, image processing, radar and sonar analysis, time-series forecasting, and medical imaging.

Koopman Mode Decomposition (KMD) has recently attracted considerable theoretical attention as a powerful extension of Fourier decomposition. Its origin traces back to the 1931 work of B.O. Koopman, who formulated a representation of nonlinear dynamical systems through linear operators acting on function spaces—now referred to as Koopman operators. The theoretical foundation of this framework was subsequently formalized, and beginning in the 1990s, research by I. Mezić and collaborators renewed interest in its potential to reveal latent dynamics in nonlinear systems. The development of Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) by P.J. Schmid ignited a new wave of research and led to advanced extensions such as Extended DMD (EDMD), which enable practical estimation of Koopman spectral components from data beyond the original limitations of DMD. Although KMD often provides accurate representations of observed data, it has been noted that its predictive accuracy may deteriorate under certain conditions.

The present study aims to address this limitation by identifying the sources of prediction error in KMD and proposing efficient algorithms to extract those Koopman modes that, if present, are the only viable candidates for accurate forecasting.

To illustrate Koopman Mode Decomposition and our contributions, we begin by recalling the concept of Fourier Decomposition (FD). Let

be a

-periodic, complex-valued function in

. That is,

for all

t, and

The space of such functions forms a Hilbert space, where the inner product between

and

is defined by

with

denoting the complex conjugate of

x. Then,

admits the decomposition:

This decomposition is justified by the fact that the family

forms a countable orthonormal basis for the Hilbert space of

-periodic functions in

. The convergence in Equation (

1) is understood in the

-norm. Although such convergence does not imply pointwise convergence,

Riesz’s theorem [

1] [Theorem 3.12] guarantees that a subsequence of the partial sums converges pointwise almost everywhere.

Koopman Mode Decomposition (KMD) [

2] is similar to FD in that it expresses a function as a sum of oscillatory components. However, unlike FD, KMD allows for exponentially growing or decaying components. Hence, if a KMD of

exists, it takes the form:

where

. Thus, unless

, each term represents an exponentially growing (if

) or decaying (if

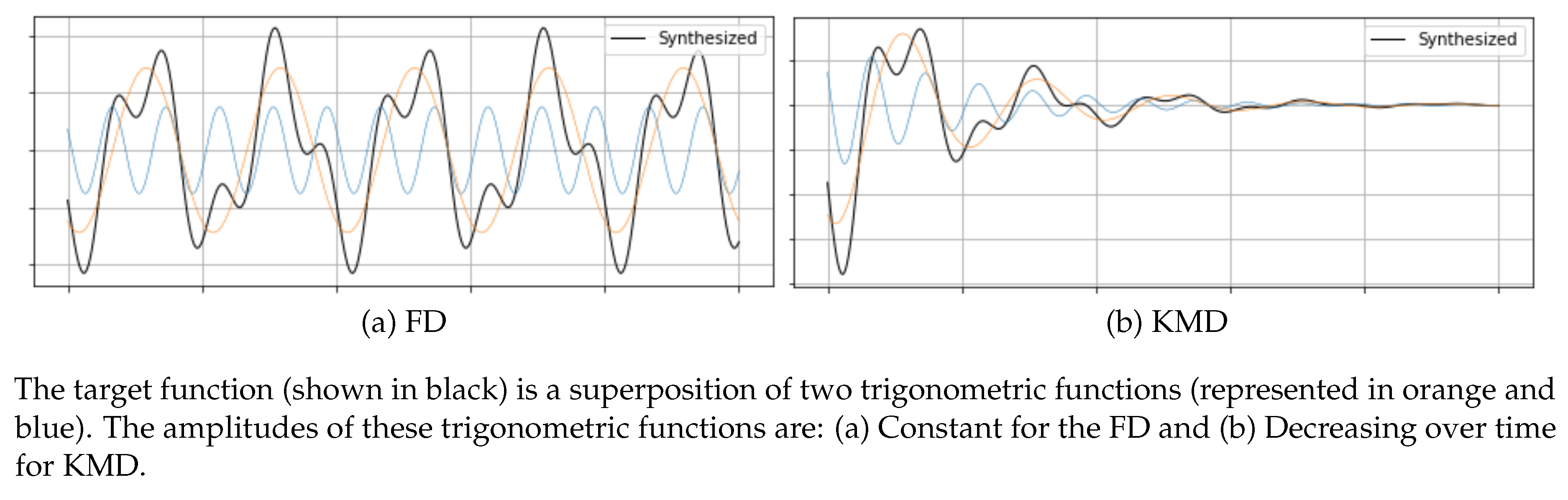

) wave (see

Figure 1). The

constitute a countable subset of the spectrum of the so-called

Koopman operator [

2].

KMD is expected to provide a more flexible framework for representing diverse phenomena and has been applied in a wide array of domains, including: fluid dynamics [

3,

4,

5,

6], chaotic systems [

7], neuroscience [

8], plasma physics [

9,

10,

11], sports analytics [

12], robotics [

13], and video processing [

14].

In practical settings, both FD and KMD rely on a finite number of observations. Without restricting the summations in Equation (

1) and Equation (

2) to finitely many terms, the decomposition becomes ill-posed. We therefore approximate the function by a finite superposition of

ℓ oscillatory components, where

ℓ is called the

degree of the decomposition.

In the case of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), we assume observations

at

, for

. Since

whenever

, the problem of finding the coefficients

reduces to solving the linear system:

This system has a unique solution, as the coefficient matrix is a square Vandermonde matrix over distinct T-th roots of unity.

In general, an

matrix

is referred to as a

Vandermonde matrix, whose determinant when

is given by

The square matrix on the right-hand side of Equation (

3) is a Vandermonde matrix, and Equation (

3) can be restated as

where

is a primitive

T-th root of unity.

By the aforementioned invertibility of the Vandermonde matrix generated by distinct points

, Equation (

3) admits a unique solution:

Here, denotes the conjugate transpose (i.e., Hermitian transpose) of a matrix .

In contrast, the KMD problem can be formulated analogously as:

with the following distinctions:

Each observable is an m-dimensional vector. We denote the matrix of observations by .

The eigenvalues and the corresponding modes are unknown and must be determined.

The choice

, which is required for DFT, is entirely unsuitable for KMD: for any distinct set of

, there always exists a corresponding set of modes

such that Equation (

6) holds exactly.

Despite the increased complexity of the KMD problem, several numerical methods exist to solve Equation (

6) for a given degree

ℓ, including: Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD), which is typically applicable when

; the Arnoldi method, applicable when

; and the vector Prony method, which allows arbitrary

ℓ. These methods yield approximate solutions minimizing the residual sum of squares (RSS), especially in the presence of observation noise.

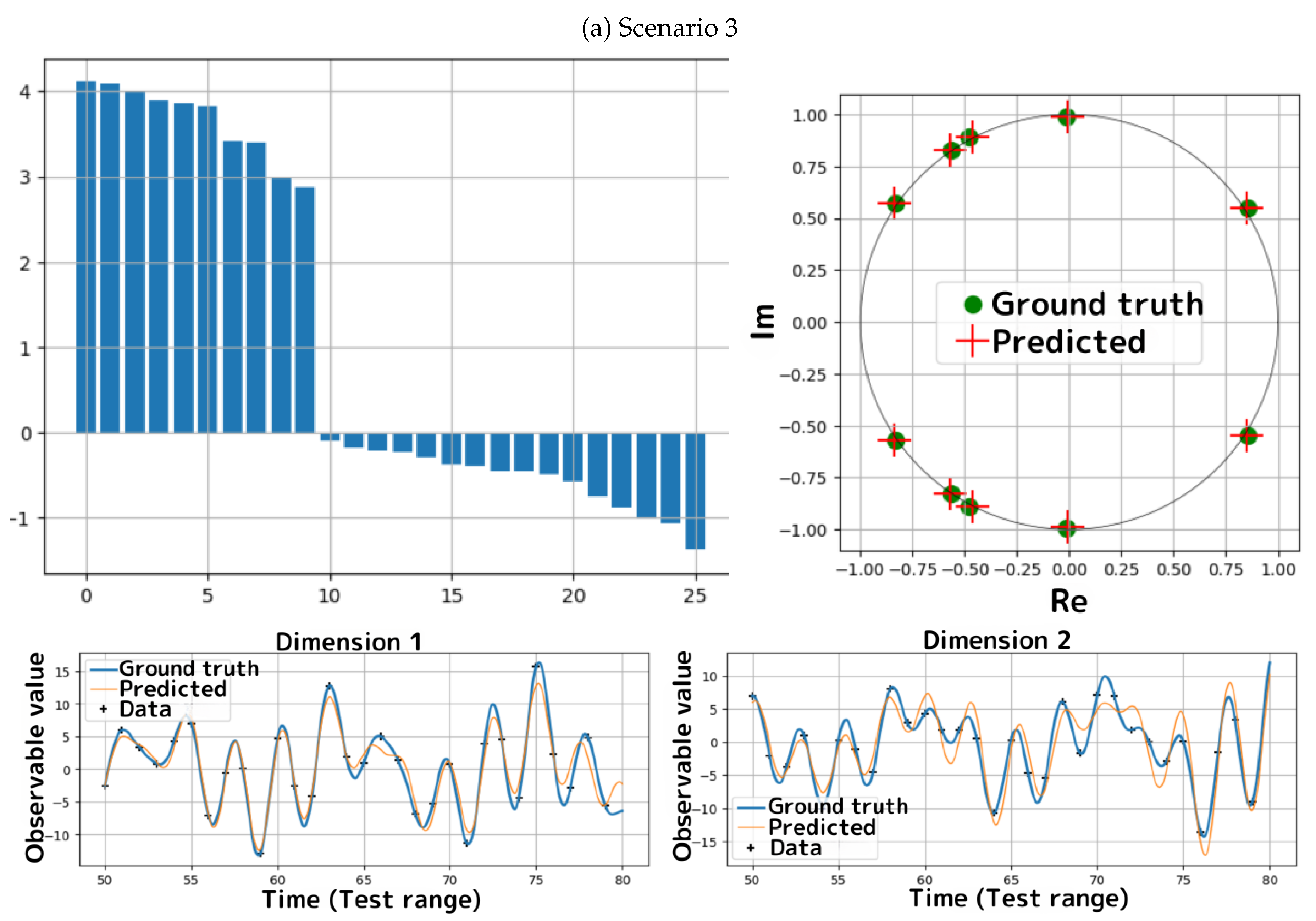

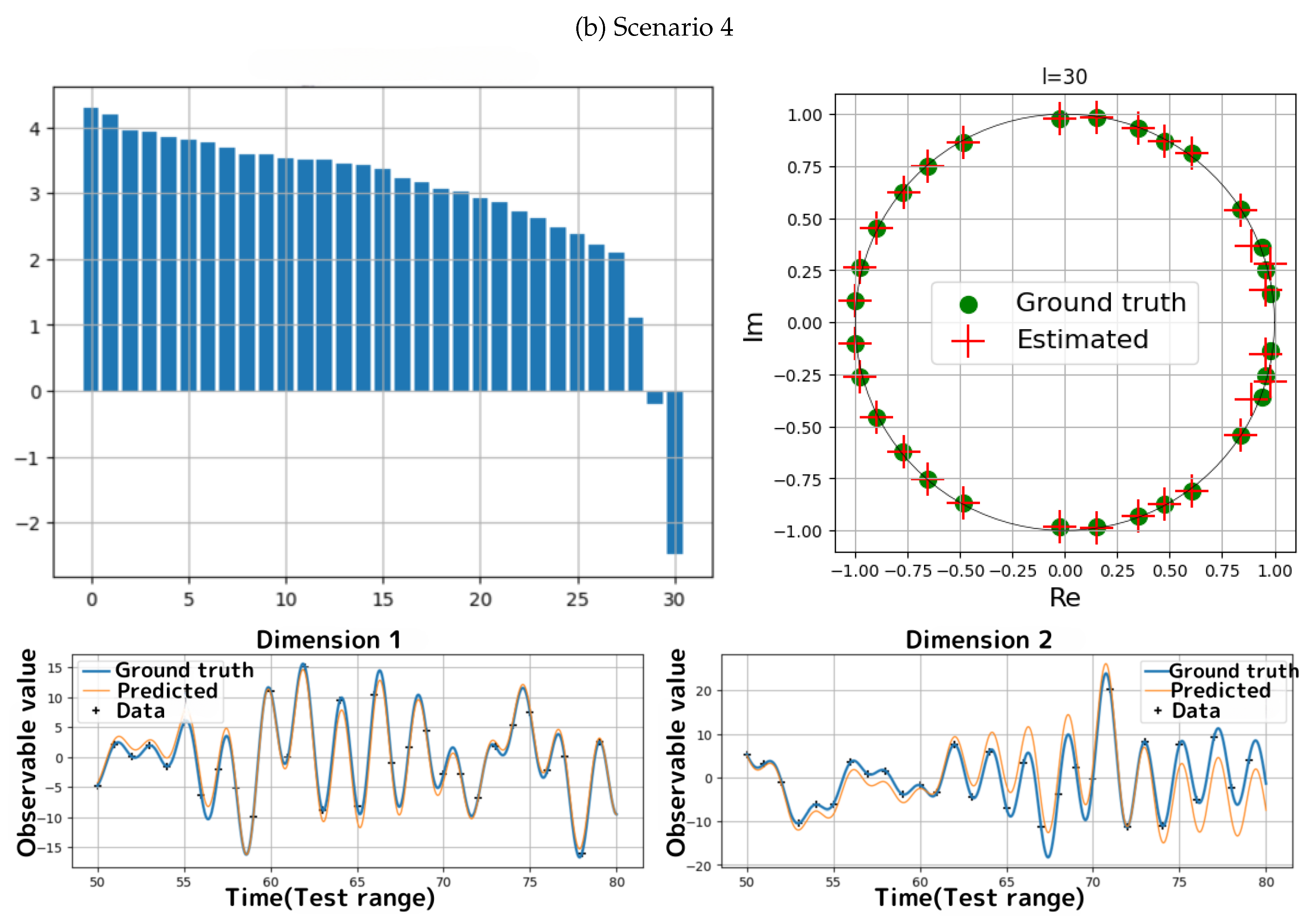

However, what remained unresolved was how to determine an optimal degree ℓ. We illustrate its importance through the following example, highlighting the predictive risk of inappropriate choice.

Example 1.

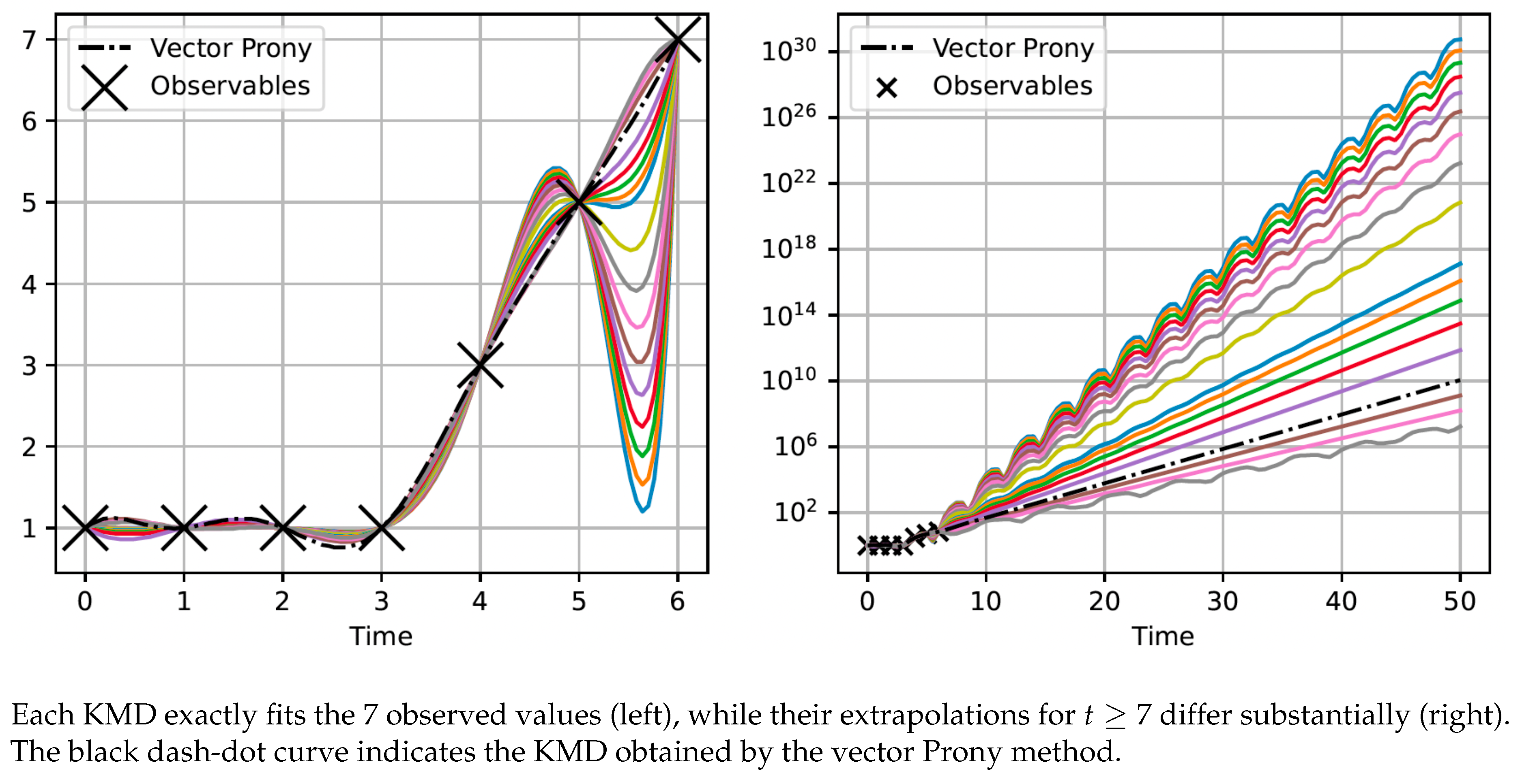

Consider one-dimensional observables given by . It is readily verified that Equation (6) admits no solution if . For , the roots of the following equation

uniquely determine the modes such that Equation (6) is satisfied, thereby yielding a valid KMD for any value of the parameter α. As illustrated in Figure 2, all such KMDs exactly reproduce the observed sequence for , yet their extrapolations for differ significantly.

This example highlights a key issue: even if an algorithm happens to return a single quartic KMD, it is merely one among infinitely many KMDs that fit the observed data. Consequently, the forecast made by such a KMD is almost certainly different from the ground truth, and the chance of accurate prediction is negligibly small.

Thus, for the sake of predictive accuracy, it is crucial to select ℓ such that it is uniquely feasible, defined as follows:

Definition 1.

Given an observable matrix , a degree ℓ is said to befeasible

if there exists at least one solution to Equation (6). Moreover, if this solution is unique, then ℓ is said to beuniquely feasible.

This paper develops a theoretical framework for uniquely feasible degrees and, based on this foundation, proposes efficient and practical algorithms to determine whether a given set of observables admits a uniquely feasible degree—and if so, to identify it. We also demonstrate through simulations that the KMD selected by our algorithms can yield highly accurate predictions.

2. Theoretical Frameworks Underlying Koopman Mode Decomposition

A key significance of Koopman Mode Decomposition (KMD) is its ability to analyze the dynamics of a nonlinear system using only methods from linear algebra. In this section, we provide a brief review of the theoretical framework of KMD, which bridges nonlinear dynamics and linear algebra.

2.1. Temporal Transition of States and Semigroup Property

Let

Z denote a (possibly unobservable) state space. Under a deterministic assumption, once a state

is observed at some time, the state of the system after an elapsed time

is uniquely determined and is denoted by

. Accordingly, the temporal evolution of the system is described by the mapping

In the discrete-time setting, is instead defined on , which can be regarded as a special case of the continuous-time formulation.

While the notation

emphasizes the bivariate nature of the mapping, the map

is essentially regarded as a univariate function of

t, with the initial state

fixed. The deterministic assumption also requires the identity

, which is equivalently expressed as

for all

. This implies that if we define

for

, then the family

forms a one-parameter semigroup under composition, that is,

holds for all

.

2.2. Koopman Operator

We denote the space of

-valued functions defined over

Z by

. The function space

forms a

-algebra, equipped with addition, multiplication, and scalar multiplication, defined as follows for

and

:

In particular, is a vector space over .

The

Koopman operator parameterized by time

t is defined as

It is straightforward to verify that the Koopman operator is a -algebra homomorphism and, in particular, a linear operator. Furthermore, we have:

Proposition 1. The collection of Koopman operators forms a one-parameter semigroup. That is, holds for any .

2.3. Koopman Generator

In general, when a one-parameter semigroup

is defined on a Banach space

, it is said to be

strongly continuous if, for every

, the following norm convergence holds:

A strongly continuous one-parameter semigroup

has several important properties [

15] [Chapter 13]:

Each is bounded; that is, the operator norm is well-defined. More precisely, there exist constants and such that for all .

The set

of all

for which

exists is a dense linear subspace of

, and

A is a closed linear operator with domain

. This operator

A is called the

infinitesimal generator of

.

If is bounded, i.e., , then .

For every

, the derivative

exists, and we have

for all

and

.

If

for some

and

(that is,

is an eigenvalue of

A), then

When we say that the Koopman operator semigroup

is

strongly continuous, we assume that it acts on a Banach space

whose elements can be regarded as functions in

in some way (e.g.,

), and that for each

the limit

holds in the norm of

. Pointwise convergence of functions is a more primitive notion, and although these two modes of convergence are generally independent, they are closely related in certain settings.

-

Let

X be a compact topological space and let

denote the space of continuous functions on

X. Since every continuous function on a compact space is bounded, we may equip

with the supremum norm:

With this norm, is a Banach space. In this setting, convergence in norm is equivalent to uniform convergence, and in particular, uniform convergence implies pointwise convergence.

Let

be a measure space, and let

for

. Elements of

are equivalence classes of measurable functions that are equal almost everywhere. Thus, any statement about pointwise convergence should be interpreted in terms of representatives of these equivalence classes, that is, convergence almost everywhere. If a sequence

satisfies

then there exists a subsequence that converges to

f pointwise almost everywhere. This follows from the completeness of

spaces and is sometimes referred to as a version of the Riesz convergence theorem (see [

1] [Theorem 3.12]).

If the Koopman operator semigroup

is bounded, then its infinitesimal generator, referred to as the

Koopman generator, and defined by

is defined on the entire Banach space.

We next consider the case in which the Koopman operators are bounded. Let be a measure space, and suppose that for each the map is measurable. We examine the boundedness of the associated Koopman operator acting on .

A sufficient condition for

to be bounded on

is that

is

non-expansive with respect to

, meaning that

In this case, for any

,

where

denotes the pushforward of

by

. If

is non-expansive, then

(as measures), and hence

so in particular

(For , the same argument shows .)

Conversely, if

is

expansive, i.e., there exists

such that

then the family

may fail to be uniformly bounded in

t (even though each fixed

can still be bounded).

In many applications, especially in ergodic theory and dynamical systems,

is assumed to be

measure-preserving, that is,

This implies

, and hence

acts as an isometry on

for every

. On

, the Koopman operators are therefore

unitary. If, in addition,

forms a measure-preserving

flow (so that

is a strongly continuous unitary group), then by Stone’s theorem [

1] [Theorem 13.40] the Koopman generator

is

skew-adjoint, i.e.,

. Since unitary and skew-adjoint operators are normal, the spectral theorem applies and provides the functional-analytic foundation for the Koopman Mode Decomposition.

2.4. Koopman Mode Decomposition and Spectral Theorem

To introduce the Koopman mode decomposition, we assume that the Koopman operator semigroup defined on a Banach space is strongly continuous in the norm of and induces a Koopman generator defined on the entire . For example, this holds when the semigroup is bounded.

Let

denote the point spectrum of

, and let

be the eigenspace corresponding to

. When

f belongs to the completion in

of the linear span of

, that is, when

holds in the norm of

, only countably many

are nonzero. We denote the corresponding eigenvalues by

. Then the Koopman mode decomposition of

f is expressed as

and the following relations hold:

If, in addition, every element of the one-parameter semigroup is measure-preserving on a measure space , then the Koopman operators and the Koopman generator defined on are unitary and skew-adjoint, respectively; that is, they are normal linear operators defined on the entire . Hence, the Koopman mode decomposition can be understood in the context of the spectral theorem.

The spectral theorem asserts that a normal operator

T defined on a Hilbert space

can be represented as

where

E is a

projection-valued measure, which plays the role of a Borel measure defined on the Borel

-algebra

of

. For each

, the value

is an orthogonal projection operator on

rather than a real number, and the measure

E satisfies the following properties:

Based on the projection-valued measure

E, the integral of a measurable function

F over

is defined as

in complete analogy with the Lebesgue integral.

This integral representation is essential, because the spectrum

may be distributed continuously in

. Furthermore, letting

denote the set of all isolated eigenvalues of

T, we can express the decomposition as

where each

for

coincides with the orthogonal projection onto the eigenspace of

.

For

—an equivalence class of functions equal almost everywhere— the Koopman mode decomposition of

f and the actions of the Koopman generator

and the Koopman operators

are obtained by setting

and assuming that the integral part of Equation (

9) vanishes (or is negligible). Since

is nonzero only for a countable subset of

, we label the corresponding eigenvalues as

for

, and write

.

For

, we obtain the Koopman mode decomposition of

f:

For

, we obtain the action of

:

For

, we obtain the action of

:

6. The Contributions of This Article

Given an observable matrix, the vector Prony method introduced in the previous section computes a DKMD for a specified Koopman degree ℓ. However, a DKMD does not always exist for the given degree, and even when it does, it may not be unique.

Definition 7 (Feasible Degree). A Koopman degree ℓ is said to befeasiblefor the observables if a DKMD of degree ℓ exists for the given observable matrix.

Although the Koopman degree ℓ must satisfy (Proposition 2), a DKMD may exist for multiple values of ℓ. Thus, selecting the optimal feasible degree is essential to obtain an optimal DKMD.

For this selection, we consider two independent principles:

- Minimality:

The optimal degree should be the smallest among all feasible degrees. This principle is analogous to Occam’s razor, favoring the simplest representation that adequately explains the observations.

- Uniqueness:

The optimal degree should correspond to a unique DKMD. If multiple DKMDs exist for a given ℓ, as described in a later section, the set of such decompositions forms a continuum, where different DKMDs yield distinct eigenvalues and modes. Consequently, any particular DKMD extracted from this continuum— such as one obtained by the vector Prony method— may fail to reproduce the true dynamics precisely.

In this article, we demonstrate that if a degree satisfies the uniqueness criterion, it also satisfies the minimality criterion, but the converse does not necessarily hold. Thus, between these two principles, we adopt the uniqueness criterion as the standard for selecting the optimal Koopman degree.

Definition 8 (Uniquely Feasible Degree). A Koopman degree is said to beuniquely feasibleif a DKMD of that degree exists and is unique for the given observables.

In summary, the objective of this paper is to establish a theoretical framework for uniquely feasible degrees. Specifically, we demonstrate and present the following:

A uniquely feasible degree for a given observable matrix, if it exists, is the smallest among all feasible degrees.

Several structural properties of uniquely feasible degrees lead to computationally efficient algorithms for determining them.

These algorithms are further extended to handle noisy observables via least-squares formulations.

8. Algorithms

Leveraging the five properties mentioned in

Section 7.4, we develop efficient algorithms to search for a uniquely feasible degree

L and to determine an

L-degree characteristic polynomial, which provides eigenvalues of a DKMD. Once mutually distinct eigenvalues are obtained, the associated Koopman modes are calculated as described in

Section 5.2. Our algorithms are categorized into:

To introduce the algorithms, we start by addressing a theoretical scenario where the observables exactly consist of a finite number of wave components. In this case, an exact DKMD is obtained. Subsequently, we consider a practical scenario where the observables comprise a finite number of dominant wave components, an infinite number of minor wave components, and noise. Here, our algorithms focus on extracting only the dominant wave components, effectively filtering out the minor components and the noise, resulting in an approximate DKMD.

8.1. A Theoretical Scenario

We first present Algorithm 1, which reduces the dimension of each observable so that decomposing the reduced observable matrix is equivalent to decomposing the original one. This reduction is practically useful for more efficient computation and clearer understanding of the underlying structure. We then present algorithms that decompose an observable matrix for two cases: (Algorithms 2 and 3) and (Algorithm 4).

8.1.1. Dimension Reduction

Although each observable vector, i.e., a column vector of , is of dimension m, the rank r of can be smaller than m. In this case, Algorithm 1 determines a dimensionally reduced observable matrix and a conversion matrix such that and . By Theorem 3, the Hankel dimensions and codimensions, as well as the set of characteristic polynomials, are invariant under this conversion, and DKMDs for and those for are mutually converted by matrix multiplication by and .

Such

and

can be constructed by selecting

r linearly independent rows of

and defining

so that these rows become the rows of

. Since these

r rows of

are linearly independent and form all the rows of

, we have

.

|

Algorithm 1 Dimension reduction of the observable matrix. |

-

Require:

-

Ensure:

Matrices and for with and

- 1:

Find such that the row vectors are linearly independent; - 2:

Determine a matrix such that the component is 1 and all other components are 0 for ; - 3:

return and . |

By applying Algorithm 1, we can reduce the problem of decomposing to the problem of decomposing with . This reduction provides benefits in terms of computational efficiency and clearer understanding of the data structure when executing the algorithms presented below. However, these algorithms are formulated in general terms and do not require that such a dimension reduction has been performed.

8.1.2. Case

Algorithm 2 first investigates whether by leveraging the equivalence between and . Indeed, if , then holds by Theorem 6. Conversely, if , then by the definition of L.

If this investigation reveals , the algorithm identifies L as by Theorem 7, and then executes Algorithm 3 to determine whether L is uniquely feasible. If , the algorithm returns the value continue, indicating that Algorithm 4 should be used.

When invoked, Algorithm 3 verifies the following:

A vector exists in . This can be efficiently verified by performing a QR decomposition of .

If such a vector exists, verify that the polynomial

has no repeated roots.

If both conditions are satisfied, this confirms that

L is feasible, and we can then apply Theorem 7. As a result, we have

, meaning that

L is uniquely feasible. Thus, the polynomial obtained in the verification is square-free and serves as the characteristic polynomial of the unique

L-degree DKMD of

. In this case, the algorithm returns the obtained characteristic polynomial. Otherwise, it returns the value no_solution, indicating that no uniquely feasible degree exists.

|

Algorithm 2 Search for an L-degree characteristic polynomial when . |

-

Require:

-

Ensure:

The signal continue if ; the characteristic polynomial if is uniquely feasible; no_solution if is not uniquely feasible. - 1:

if then

- 2:

Let ; - 3:

Execute Algorithm 3; - 4:

return the return value of Algorithm 3; - 5:

else - 6:

return continue - 7:

end if |

|

Algorithm 3 Determine the characteristic polynomial. |

-

Require:

and L

-

Ensure:

An L-degree characteristic polynomial or no_solution - 1:

if then

- 2:

Let ; - 3:

if has no repeated roots then

- 4:

return

- 5:

end if

- 6:

end if - 7:

return no_solution |

8.1.3. Case

Algorithm 4 details the procedure for cases when . Note that if L is uniquely feasible, then holds by Theorem 5, and this gives the best possible upper bound.

The algorithm first verifies whether . If this condition does not hold, no uniquely feasible degree exists, and the algorithm returns the signal no_solution.

If , then L lies in the range . The algorithm utilizes a binary search to find L, leveraging the fact that is a strictly increasing function by Theorem 6.

Since the identified L does not necessarily satisfy , the algorithm must verify before executing Algorithm 3 to confirm that L is uniquely.

8.2. A Practical Scenario

In practice, even if the Koopman operator has only discrete eigenvalues, the number of eigenvalues can be infinite, and in addition, observables can contain error signals. In such situations, the purpose of DKMD is to find a finite number of major wave components that most significantly affect the observables. From the viewpoint of executing our algorithms, the presence of minor components and errors makes direct computation of Hankel dimensions via QR decomposition impractical. In fact, may always hold, which makes it impossible to identify the Hankel dimensions. In this section, we present a method to estimate Hankel dimensions for the major components via singular value decomposition (SVD) rather than QR decomposition.

We assume that the observables are represented as

|

Algorithm 4 Search for an L-degree characteristic polynomial when . |

-

Require:

with

-

Ensure:

Either the characteristic polynomial of the DKMD of for the uniquely feasible degree , if present, or no_solution, otherwise. - 1:

if then

- 2:

return

- 3:

end if - 4:

Let ; - 5:

Let ; - 6:

while do

- 7:

Let ; - 8:

if then

- 9:

Let ; - 10:

else if then

- 11:

Let ; - 12:

Execute Algorithm 3; - 13:

return the return value of Algorithm 3; - 14:

else

- 15:

Let ; - 16:

end if

- 17:

end while - 18:

if then

- 19:

Let ; - 20:

Execute Algorithm 3; - 21:

return the return value of Algorithm 3; - 22:

else - 23:

return ; - 24:

end if |

where

and

represent major and minor wave components, respectively, and

is noise. We define:

and our basic assumption is that

is a small perturbation. Our aim is to estimate

from

, taking advantage of the fact that

equals the number of positive singular values of

.

We consider

with

. Let

,

, and

be the singular values of

,

, and

, respectively. Then,

holds for all

. This can be proven as follows. By the Courant–Fischer min-max theorem [

17], the

i-th singular value of

satisfies

Since

, we have

as follows:

By the same reasoning, we also obtain .

Furthermore, if

, that is,

then we have

Therefore, if is sufficiently larger than , there exists a large gap between for and for , and hence, we can estimate r from . Thus, if we can assume that the smallest positive singular value of is sufficiently larger than the largest singular value of , we can apply this method to estimate .

8.3. Time Complexities

The computationally intensive operations in these algorithms primarily involve executing QR decomposition (QRD), singular value decomposition (SVD), and solving equations (EqS).

Table 2 demonstrates that the algorithms execute these computations only a small number of times, and consequently, prove to be highly efficient.