Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

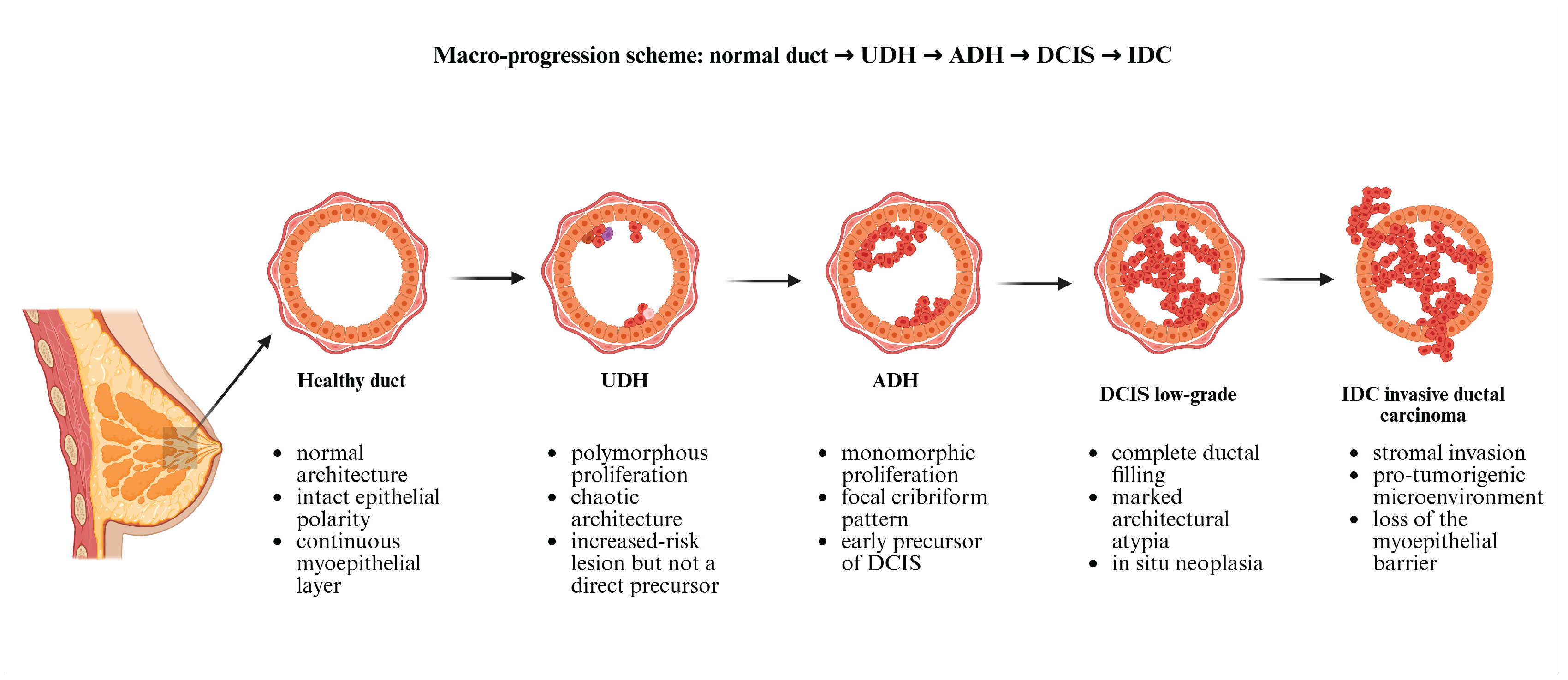

2. Mammary Ductal Hyperplasia (MDH) and Its Types

- nonproliferative changes;

- proliferative hyperplasia without cytologic atypia

- proliferative hyperplasia with cytologic atypia [1].

2.1. Classification of Benign Breast Lesions and Associated Risks

2.1.1. Nonproliferative Changes

2.1.2. Proliferative Hyperplasia Without Atypia

2.1.3. Proliferative Hyperplasia with Atypia

2.1.4. Subtype Nuances: FEA, ADH vs ALH and the Extent of Atypia

2.1.5. Upgrade Rates and Interpretive Caution

2.2. Mechanistic Frameworks: Why Some Lesions Progress?

2.2.1. Degree of Atypia

2.2.2. Morphologic and Histopathologic Continuum: ADH as a “mini-DCIS”

2.2.3. Epidemiologic and Clinical Evidence: Progression Risk Linked to Atypia

2.2.4. Microenvironmental and Epithelial Constraints: How Atypia May Loosen Barriers

3. Genetic Causes and Mechanisms of Mammary Gland Hyperplasia: From Atypia to Malignant Transformation

3.1. Mechanism of Malignant Transformation

3.1.1. Gene Expression Changes

3.1.2. Loss of Tumor Suppressor Genes

3.1.3. Genetic Instability

3.1.4. Microenvironmental Factors

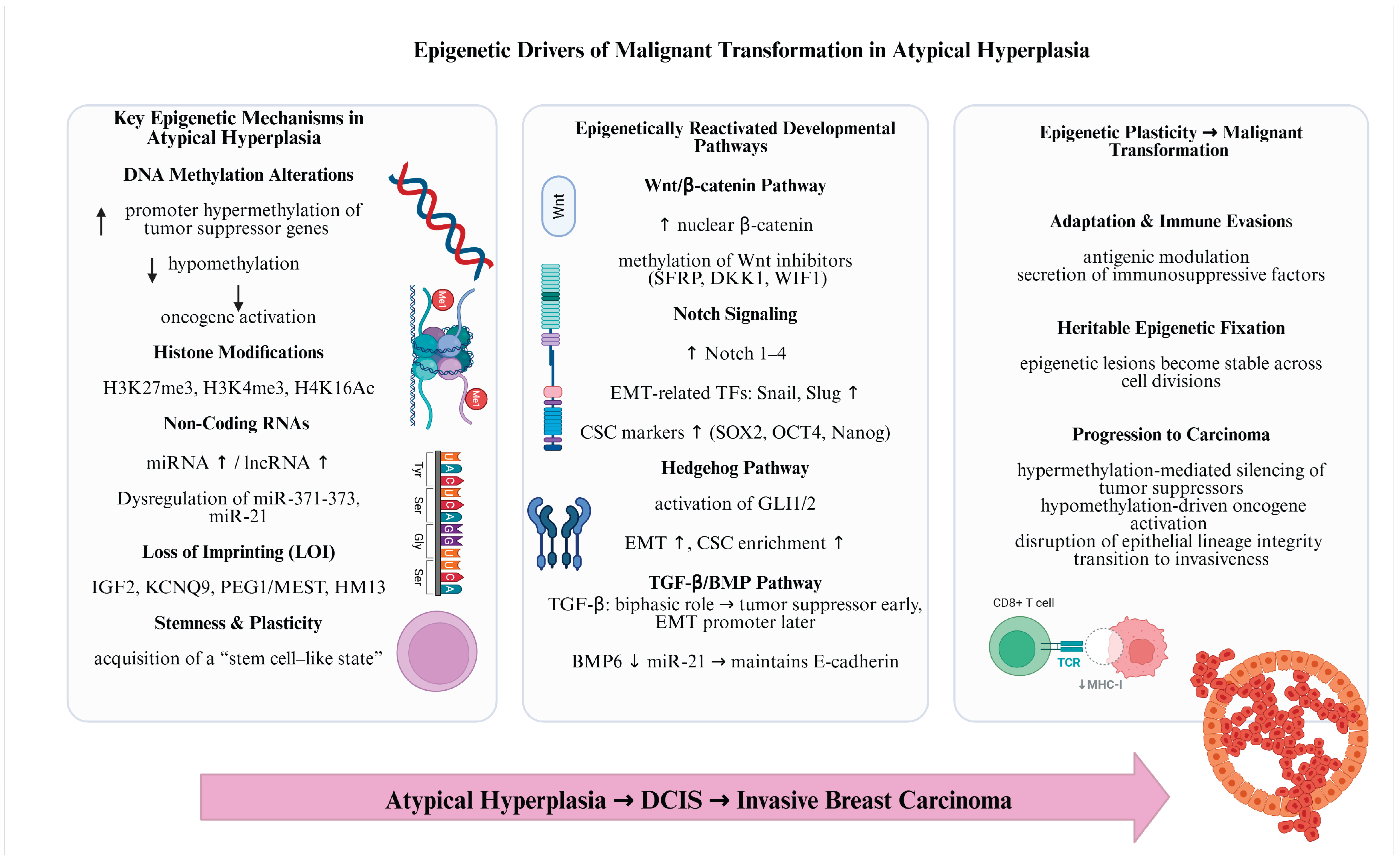

4. Epigenetic Modifications in Atypical Hyperplasia and Their Role in Malignant Transformation

4.1. General Features

4.2. The Main Epigenetic Mechanisms Involved in Breast Tumorigenesis

4.3. Epigenetic Plasticity

5. Tumor Microenvironment Changes in Driving Malignant Transformation of Atypical Hyperplasia

5.1. Key TME Components and Their Impact on Malignant Transformation

5.1.1. Stromal Remodeling

5.1.2. Immune Cell Infiltration

5.1.3. Hypoxia and Angiogenesis

5.1.5. Extracellular Matrix (ECM) and Cell-Cell Interactions

5.1.4. Exosomes and Tumor Signaling

6. Diet and Environmental Factors Influencing the Transformation of Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia (ADH) into Breast Cancer

6.1. Dietary Factors Influencing ADH Progression

6.2. Environmental Factors and Toxins Influencing ADH Progression

6.2.1. Ionizing Radiations

6.2.2. Chemical Endocrine Disruptors

6.2.3. Air Pollution

6.2.4. Pesticides

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kumar, V; Abbas, AK; Aster, JC. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, 10th ed.; Philadelphia (PA); Elsevier, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, C.L.; Hines, S.L.; Ghosh, K. Common Benign Breast Concerns for the Primary Care Physician. CCJM 2019, 86, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, L.C.; Degnim, A.C.; Pankratz, V.S.; Blake, C.; Iii, L.J.M. Benign Breast Disease and the Risk of Breast Cancer. n engl j med 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A.; O’Driscoll, J.; Abubakar, M.; Bennett, K.E.; Carmody, E.; Flanagan, F.; Gierach, G.L.; Mullooly, M. A Systematic Review of Determinants of Breast Cancer Risk among Women with Benign Breast Disease. npj Breast Cancer 2025, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachs, A.; Stubert, J.; Reimer, T.; Hartmann, S. Benign Breast Disease in Women. Deutsches Ärzteblatt international 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, L.; Barnard, K.; Elnicki, D.M. Benign Breast Disease: When to Treat, When to Reassure, When to Refer. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2002, 69, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat, G.C.; Jones, J.G.; Olson, N.; Negassa, A.; Duggan, C.; Ginsberg, M.; Kandel, R.A.; Glass, A.G.; Rohan, T.E. A Multi-Center Prospective Cohort Study of Benign Breast Disease and Risk of Subsequent Breast Cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2010, 21, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.C.; Baer, H.J.; Tamimi, R.M.; Connolly, J.L.; Colditz, G.A.; Schnitt, S.J. The Influence of Family History on Breast Cancer Risk in Women with Biopsy-confirmed Benign Breast Disease: Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer 2006, 107, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, L.C.; Degnim, A.C.; Santen, R.J.; Dupont, W.D.; Ghosh, K. Atypical Hyperplasia of the Breast — Risk Assessment and Management Options. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.A.; Newell, M.S. Radial Scars of the Breast Encountered at Core Biopsy: Review of Histologic, Imaging, and Management Considerations. American Journal of Roentgenology 2017, 209, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.M.; Cha, J.H.; Shin, H.J.; Chae, E.Y.; Choi, W.J.; Kim, H.H.; Oh, H.-Y. Radial Scars/Complex Sclerosing Lesions of the Breast: Radiologic and Clinicopathologic Correlation. BMC Med Imaging 2018, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoué, V.; Fritel, X.; Antoine, M.; Beltjens, F.; Bendifallah, S.; Boisserie-Lacroix, M.; Boulanger, L.; Canlorbe, G.; Catteau-Jonard, S.; Chabbert-Buffet, N.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF): Benign Breast Tumors – Short Text. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2016, 200, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.I.; Borges, S.; Sousa, A.; Ribeiro, C.; Mesquita, A.; Martins, P.C.; Peyroteo, M.; Coimbra, N.; Leal, C.; Reis, P.; et al. Radial Scar of the Breast: Is It Possible to Avoid Surgery? European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO) 2017, 43, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, V.Y.; Causey, M.W.; Steele, S.R.; Keylock, J.B.; Brown, T.A. The Treatment of Radial Scars in the Modern Era—Surgical Excision Is Not Required. The American SurgeonTM 2010, 76, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, A.R.; Sieck, L.; Booth, C.N.; Calhoun, B.C. Radial Scars Diagnosed on Breast Core Biopsy: Frequency of Atypia and Carcinoma on Excision and Implications for Management. The Breast 2016, 30, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.Y.Y.; Veis, D.J.; Aft, R. Radial Scar on Image-Guided Breast Biopsy: Is Surgical Excision Necessary? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018, 170, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.L.; Dupont, W.D.; Rogers, L.W.; Rados, M.S. Atypical Hyperplastic Lesions of the Female Breast. A Long-Term Follow-up Study. Cancer 1985, 55, 2698–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnim, A.C.; Visscher, D.W.; Berman, H.K.; Frost, M.H.; Sellers, T.A.; Vierkant, R.A.; Maloney, S.D.; Pankratz, V.S.; De Groen, P.C.; Lingle, W.L.; et al. Stratification of Breast Cancer Risk in Women With Atypia: A Mayo Cohort Study. JCO 2007, 25, 2671–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, L.C.; Baer, H.J.; Tamimi, R.M.; Connolly, J.L.; Colditz, G.A.; Schnitt, S.J. Magnitude and Laterality of Breast Cancer Risk According to Histologic Type of Atypical Hyperplasia: Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer 2007, 109, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menes, T.S.; Kerlikowske, K.; Lange, J.; Jaffer, S.; Rosenberg, R.; Miglioretti, D.L. Subsequent Breast Cancer Risk Following Diagnosis of Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia on Needle Biopsy. JAMA Oncol 2017, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kader, T.; Hill, P.; Rakha, E.A.; Campbell, I.G.; Gorringe, K.L. Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia: Update on Diagnosis, Management, and Molecular Landscape. Breast Cancer Res 2018, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board Breast Tumours; International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2019.

- Schnitt, S.J. The Diagnosis and Management of Pre-Invasive Breast Disease: Flat Epithelial Atypia – Classification, Pathologic Features and Clinical Significance. Breast Cancer Res 2003, 5, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, L.R.; Bahl, M.; Gadd, M.A.; Lehman, C.D. Flat Epithelial Atypia: Upgrade Rates and Risk-Stratification Approach to Support Informed Decision Making. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2017, 225, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dialani, V.; Venkataraman, S.; Frieling, G.; Schnitt, S.J.; Mehta, T.S. Does Isolated Flat Epithelial Atypia on Vacuum-Assisted Breast Core Biopsy Require Surgical Excision? Breast J 2014, 20, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPasquale, A.; Silverman, S.; Farag, E.; Peiris, L. Flat Epithelial Atypia: Are We Being Too Aggressive? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020, 179, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, L.C.; Radisky, D.C.; Frost, M.H.; Santen, R.J.; Vierkant, R.A.; Benetti, L.L.; Tarabishy, Y.; Ghosh, K.; Visscher, D.W.; Degnim, A.C. Understanding the Premalignant Potential of Atypical Hyperplasia through Its Natural History: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Cancer Prevention Research 2014, 7, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.C.; Aroner, S.A.; Connolly, J.L.; Colditz, G.A.; Schnitt, S.J.; Tamimi, R.M. Breast Cancer Risk by Extent and Type of Atypical Hyperplasia: An Update from the N Urses’ H Ealth S Tudies. Cancer 2016, 122, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degnim, A.C.; Dupont, W.D.; Radisky, D.C.; Vierkant, R.A.; Frank, R.D.; Frost, M.H.; Winham, S.J.; Sanders, M.E.; Smith, J.R.; Page, D.L.; et al. Extent of Atypical Hyperplasia Stratifies Breast Cancer Risk in 2 Independent Cohorts of Women. Cancer 2016, 122, 2971–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A.; O’Driscoll, J.; Abubakar, M.; Bennett, K.E.; Carmody, E.; Flanagan, F.; Gierach, G.L.; Mullooly, M. A Systematic Review of Determinants of Breast Cancer Risk among Women with Benign Breast Disease. npj Breast Cancer 2025, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.L.; Wagner, J.L. Contemporary Management of Atypical Breast Lesions Identified on Percutaneous Biopsy: A Narrative Review. Ann Breast Surg 2021, 5, 9–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, C.L.; Fraker, J.L.; Pruthi, S. Updates on Management of Atypical Hyperplasia of the Breast. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2025, 100, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, AJ; Bing, RS; Ding, DC. Endometrial Atypical Hyperplasia and Risk of Endometrial Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Nov 5;14(22):2471. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pinder, S.E.; Ellis, I.O. The Diagnosis and Management of Pre-Invasive Breast Disease: Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS) and Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia (ADH) – Current Definitions and Classification. Breast Cancer Res 2003, 5, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J; Noguchi, N; Marinovich, ML; Sprague, BL; Salisbury, E; Houssami, N. Atypical ductal or lobular hyperplasia, lobular carcinoma in-situ, flat epithelial atypia, and future risk of developing breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast. 2024 Oct;77:103807. [CrossRef]

- Han, LK; Hussain, A; Dodelzon, K; Ginter, PS; Towne, WS; Marti, JL. Active Surveillance of Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia of the Breast. Clin Breast Cancer. 2023 Aug;23(6):649-657. Epub 2023 May 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, D.L.; Dupont, W.D.; Rogers, L.W.; Rados, M.S. Atypical Hyperplastic Lesions of the Female Breast. A Long-Term Follow-up Study. Cancer 1985, 55, 2698–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, F.A.; Norris, H.J. A Comparison of the Results of Long-Term Follow-up for Atypical Intraductal Hyperplasia and Intraductal Hyperplasia of the Breast. Cancer 1990, 65, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowsky, A; Glencer, A; Ramalingam, K; Schindler, N; Mori, H; Ghule, P; Lee, K; Nachmanson, D; Officer, A; Harismendy, O; Stein, J; Stein, G; Evans, M; Weaver, D; Yau, C; Hirst, G; Campbell, M; Esserman, L. Tumor microenvironmental determinants of high-risk DCIS progression. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2024 May 9:rs.3.rs-4126092. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, Z.; Zheng, B.; Lin, X.; Pan, Y.; Gong, P.; Zhuo, W.; Hu, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, L.; et al. Cancer-associated Fibroblasts in Breast Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities. Cancer Communications 2022, 42, 401–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northey, J.J.; Barrett, A.S.; Acerbi, I.; Hayward, M.-K.; Talamantes, S.; Dean, I.S.; Mouw, J.K.; Ponik, S.M.; Lakins, J.N.; Huang, P.-J.; et al. Stiff Stroma Increases Breast Cancer Risk by Inducing the Oncogene ZNF217. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2020, 130, 5721–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, R.; Liu, Z.; Mohamud, R.; Mussa, A. Editorial: Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1661039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, X.; Yu, W.; Liu, J.; Tang, D.; Yang, L.; Chen, X. Oxidative Cell Death in Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, B.; Luo, M.; Huang, J.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, J. Progression from Ductal Carcinoma in Situ to Invasive Breast Cancer: Molecular Features and Clinical Significance. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajzendanc, K. DCIS Progression and the Tumor Microenvironment: Molecular Insights and Prognostic Challenges. Cancers 2025, 17, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Schuyler, P.A.; Dupont, W.D.; Page, D.L. The Natural History of Low-grade Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast in Women Treated by Biopsy Only Revealed over 30 Years of Long-term Follow-up. Cancer 2005, 103, 2481–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhala, R.; Cando, L.F.; Verma, P.; Adesoye, T.; Bhardwaj, A. Biomarkers Predicting Progression and Prognosis of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS). Anticancer Res 2025, 45, 1305–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, K.J.; Roberts, A.L.; Conlon, E.M.; Mayfield, J.A.; Hagen, M.J.; Crisi, G.M.; Bentley, B.A.; Kane, J.J.; Makari-Judson, G.; Mason, H.S.; et al. Gene Expression Signature of Atypical Breast Hyperplasia and Regulation by SFRP1. Breast Cancer Res 2019, 21, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombonati, A; Sgroi, DC. The molecular pathology of breast cancer progression. J Pathol. 2011 Jan;223(2):307-17. Epub 2010 Nov 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krings, G; Shamir, ER; Shelley Hwang, E; Chen, YY. Genetic Analysis of Early Neoplasia in the Breast: Next-Generation Sequencing of Flat Epithelial Atypia and Associated Ductal and Lobular Lesions. Mod Pathol. 2025 Jun 17;38(11):100820. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keraite, I; Alvarez-Garcia, V; Garcia-Murillas, I; Beaney, M; Turner, NC; Bartos, C; Oikonomidou, O; Kersaudy-Kerhoas, M; Leslie, NR. PIK3CA mutation enrichment and quantitation from blood and tissue. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 13;10(1):17082. [CrossRef]

- Van Baelen, K; Geukens, T; Maetens, M; Tjan-Heijnen, V C.G.; Lord, C J; Linn, S; et al. Current and future diagnostic and treatment strategies for patients with invasive lobular breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2022, 33(8), 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, A; Lakhani, SR. Lobular carcinoma in situ: diagnostic criteria and molecular correlates. Mod Pathol. 2021 Jan;34(Suppl 1):8-14. Epub 2020 Oct 6. [CrossRef]

- Cai, YW; Liu, CC; Zhang, YW; Liu, YM; Chen, L; Xiong, X; Shao, ZM; Yu, KD. MAP3K1 mutations confer tumor immune heterogeneity in hormone receptor-positive HER2-negative breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2024 Nov 12;135(2):e183656. [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, JE; Lindsey, B; Zukin, M; et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants in an unselected population of women with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2025, 8(9), e2531577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plesea, RM; Riza, AL; Ahmet, AM; et al. Clinically significant BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline variants in breast cancer—A single-center experience. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, J; Bomanson, J; Pérez-Tenorio, G; Jönsson, C; Nordenskjöld, B; Fornander, T; Lindström, LS; Stål, O. GATA3 and markers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition predict long-term benefit from tamoxifen in ER-positive breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2024 Sep 6;10(1):78. [CrossRef]

- Dopeso, H; Gazzo, AM; Derakhshan, F; Brown, DN; Selenica, P; Jalali, S; Da Cruz Paula, A; Marra, A; da Silva, EM; Basili, T; Gusain, L; Colon-Cartagena, L; Bhaloo, SI; Green, H; Vanderbilt, C; Oesterreich, S; Grabenstetter, A; Kuba, MG; Ross, D; Giri, D; Wen, HY; Zhang, H; Brogi, E; Weigelt, B; Pareja, F; Reis-Filho, JS. Genomic and epigenomic basis of breast invasive lobular carcinomas lacking CDH1 genetic alterations. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2024 Feb 12;8(1):33. [CrossRef]

- Smyth, LM; Tamura, K; Oliveira, M; Ciruelos, EM; Mayer, IA; Sablin, MP; Biganzoli, L; Ambrose, HJ; Ashton, J; Barnicle, A; Cashell, DD; Corcoran, C; de Bruin, EC; Foxley, A; Hauser, J; Lindemann, JPO; Maudsley, R; McEwen, R; Moschetta, M; Pass, M; Rowlands, V; Schiavon, G; Banerji, U; Scaltriti, M; Taylor, BS; Chandarlapaty, S; Baselga, J; Hyman, DM. Capivasertib, an AKT Kinase Inhibitor, as Monotherapy or in Combination with Fulvestrant in Patients with AKT1E17K-Mutant, ER-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Aug 1;26(15):3947-3957. Epub 2020 Apr 20. [CrossRef]

- Chen, KM; Stephen, JK; Raju, U; Worsham, MJ. Delineating an epigenetic continuum for initiation, transformation and progression to breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2011 Jun;3(2):1580-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, SK; Fuqua, SAW. ESR1 mutations and therapeutic resistance in metastatic breast cancer: progress and remaining challenges. Br J Cancer. 2022 Feb;126(2):174-186. Epub 2021 Oct 7. [CrossRef]

- Arruabarrena-Aristorena, A; Maag, JLV; Kittane, S; Cai, Y; Karthaus, WR; Ladewig, E; Park, J; Kannan, S; Ferrando, L; Cocco, E; Ho, SY; Tan, DS; Sallaku, M; Wu, F; Acevedo, B; Selenica, P; Ross, DS; Witkin, M; Sawyers, CL; Reis-Filho, JS; Verma, CS; Jauch, R; Koche, R; Baselga, J; Razavi, P; Toska, E; Scaltriti, M. FOXA1 Mutations Reveal Distinct Chromatin Profiles and Influence Therapeutic Response in Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020 Oct 12;38(4):534-550.e9. Epub 2020 Sep 3. [CrossRef]

- Marei, HE. Epigenetic regulators in cancer therapy and progression. NPJ Precis Oncol 2025, 9, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqsood, Q; Khan, MU; Fatima, T; et al. Recent insights into breast cancer: molecular pathways, epigenetic regulation, and emerging targeted therapies. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2025, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajzendanc, K; Domagała, P; Hybiak, J; et al. BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation is not associated with germline variants in Polish breast cancer patients. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2025, 23(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H; Fang, Y; Wang, H; Lu, T; Chen, Q; Liu, H. Progress in epigenetic research of breast cancer: a bibliometric analysis since the 2000s. Front Oncol. 2025 Sep 5;15:1619346. [CrossRef]

- Pu, R; Laitala, L; Alli, P; et al. Methylation profiling of benign and malignant breast lesions and its application to cytopathology. Mod Pathol. 2003, 16(11), 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, AM; Ianculescu, LM; Suciu, N. MiRNAs as potential biomarkers in early breast cancer detection: a systematic review. J Med Life 2024, 17(6), 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keohavong, P; Gao, WM; Mady, HH; Kanbour-Shakir, A; Melhem, MF. Analysis of p53 mutations in cells taken from paraffin-embedded tissue sections of ductal carcinoma in situ and atypical ductal hyperplasia of the breast. Cancer Lett. 2004 Aug 20;212(1):121-30. [CrossRef]

- Panda, KM; Naik, R. A Clinicopathological Study of Benign Phyllodes Tumour of Breast with Emphasis on Unusual Features. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Jul;10(7):EC14-7. Epub 2016 Jul 1. [CrossRef]

- Kader, T; Hill, P; Rakha, EA; Campbell, IG; Gorringe, KL. Atypical ductal hyperplasia: update on diagnosis, management, and molecular landscape. Breast Cancer Res. 2018 May 2;20(1):39. [CrossRef]

- Laws, A; Leonard, S; Hershey, E; Stokes, S; Vincuilla, J; Sharma, E; Milliron, K; Garber, JE; Merajver, SD; King, TA; Pilewskie, ML. Upgrade Rates and Breast Cancer Development Among Germline Pathogenic Variant Carriers with High-Risk Breast Lesions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024 May;31(5):3120-3127. Epub 2024 Jan 23. [CrossRef]

- Werner, M; Mattis, A; Aubele, M; Cummings, M; Zitzelsberger, H; Hutzler, P; Höfler, H. 20q13.2 amplification in intraductal hyperplasia adjacent to in situ and invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Virchows Arch. 1999 Nov;435(5):469-72. [CrossRef]

- Martin, EM; Orlando, KA; Yokobori, K; Wade, PA. The estrogen receptor/GATA3/FOXA1 transcriptional network: lessons learned from breast cancer. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2021 Dec;71:65-70. Epub 2021 Jul 2. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y; Fu, F; Lv, J; Wang, M; Li, Y; Zhang, J; Wang, C. Identification of potential key genes for HER-2 positive breast cancer based on bioinformatics analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Jan;99(1):e18445. [CrossRef]

- Kader, T; Hill, P; Rakha, EA; Campbell, IG; Gorringe, KL. Atypical ductal hyperplasia: update on diagnosis, management, and molecular landscape. Breast Cancer Res. 2018 May 2;20(1):39. [CrossRef]

- Santisteban, M; Reynolds, C; Barr Fritcher, EG; Frost, MH; Vierkant, RA; Anderson, SS; Degnim, AC; Visscher, DW; Pankratz, VS; Hartmann, LC. Ki67: a time-varying biomarker of risk of breast cancer in atypical hyperplasia. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 Jun;121(2):431-7. Epub 2009 Sep 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, KJ; Roberts, AL; Conlon, EM; Mayfield, JA; Hagen, MJ; Crisi, GM; Bentley, BA; Kane, JJ; Makari-Judson, G; Mason, HS; Yu, J; Zhu, LJ; Simin, K; Johnson, JPS; Khan, A; Schneider, BR; Schneider, SS; Jerry, DJ. Gene expression signature of atypical breast hyperplasia and regulation by SFRP1. Breast Cancer Res. 2019 Jun 27;21(1):76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassini, D; Cascardi, E; Sarotto, I; Annaratone, L; Sapino, A; Berrino, E; Marchiò, C. Unusual Patterns of HER2 Expression in Breast Cancer: Insights and Perspectives. Pathobiology Epub 2022 May 2. 2022, 89(5), 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luen, SJ; Viale, G; Nik-Zainal, S; Savas, P; Kammler, R; Dell’Orto, P; Biasi, O; Degasperi, A; Brown, LC; Láng, I; MacGrogan, G; Tondini, C; Bellet, M; Villa, F; Bernardo, A; Ciruelos, E; Karlsson, P; Neven, P; Climent, M; Müller, B; Jochum, W; Bonnefoi, H; Martino, S; Davidson, NE; Geyer, C; Chia, SK; Ingle, JN; Coleman, R; Solbach, C; Thürlimann, B; Colleoni, M; Coates, AS; Goldhirsch, A; Fleming, GF; Francis, PA; Speed, TP; Regan, MM; Loi, S. Genomic characterisation of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer arising in very young women. Ann Oncol. 2023 Apr;34(4):397-409. Epub 2023 Jan 25. [CrossRef]

- Fico, F; Santamaria-Martínez, A. TGFBI modulates tumour hypoxia and promotes breast cancer metastasis. Mol Oncol. 2020 Dec;14(12):3198-3210. Epub 2020 Nov 5. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H; Wang, X; Xu, L. Transforming growth factor-induced gene TGFBI is correlated with the prognosis and immune infiltrations of breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2024 Jan 20;22(1):22. [CrossRef]

- Han, D; Li, Z; Luo, L; Jiang, H. Targeting Hypoxia and HIF1α in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: New Insights from Gene Expression Profiling and Implications for Therapy. Biology (Basel). 2024 Jul 31;13(8):577. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobi, G; Cline, JM; Ethun, KF; Simillion, C; Keller, I; Stute, P. Impact of 6 month conjugated equine estrogen versus estradiol-treatment on biomarkers and enriched gene sets in healthy mammary tissue of non-human primates. PLoS One. 2022 Mar 17;17(3):e0264057. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bockstal, MR; Wesseling, J; Lips, EH; Smidt, M; Galant, C; van Deurzen, CHM. Systematic assessment of HER2 status in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a perspective on the potential clinical relevance. Breast Cancer Res. 2024 Aug 27;26(1):125. [CrossRef]

- Sapino, A; Marchiò, C; Kulka, J. “Borderline” epithelial lesions of the breast: what have we learned in the past three decades? Pathologica. 2021 Oct;113(5):354-359. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batistatou, A; Stefanou, D; Arkoumani, E; Agnantis, NJ. The usefulness of p63 as a marker of breast myoepithelial cells. In Vivo. 2003 Nov-Dec;17(6):573-6.

- Taha, SR; Boulos, F. E-cadherin staining in the diagnosis of lobular versus ductal neoplasms of the breast: the emperor has no clothes. Histopathology. 2025 Feb;86(3):327-340. Epub 2024 Aug 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H; Antony, VM; Tang, H; Theriot, J; Liang, Y; Hui, P; Krishnamurti, U; DiGiovanna, MP. PTEN inactivating mutations are associated with hormone receptor loss during breast cancer recurrence. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2025 Jun;211(2):441-447. Epub 2025 Mar 10. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, G; Ahmadinejad, N; Zarei, D; Sadighi, N. Sonographic Correlations With Histological Grade and Biomarker Profiles in Breast Invasive Ductal Carcinoma. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2025 Aug;8(8):e70288. [CrossRef]

- Boyraz, B; Ly, A. Spectrum of histopathologic findings in risk-reducing bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in patients with and without BRCA mutations. Hum Pathol. 2024 Sep;151:105534. Epub 2023 Nov 22. [CrossRef]

- Dabbs, DJ; Carter, G; Fudge, M; Peng, Y; Swalsky, P; Finkelstein, S. Molecular alterations in columnar cell lesions of the breast. Mod Pathol. 2006 Mar;19(3):344-9. [CrossRef]

- Aubele, MM; Cummings, MC; Mattis, AE; Zitzelsberger, HF; Walch, AK; Kremer, M; Höfler, H; Werner, M. Accumulation of chromosomal imbalances from intraductal proliferative lesions to adjacent in situ and invasive ductal breast cancer. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2000 Mar;9(1):14-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuaqui, RF; Zhuang, Z; Emmert-Buck, MR; Liotta, LA; Merino, MJ. Analysis of loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 11q13 in atypical ductal hyperplasia and in situ carcinoma of the breast. Am J Pathol. 1997 Jan;150(1):297-303. [PubMed]

- Ghaleb, A; Padellan, M; Marchenko, N. Mutant p53 drives the loss of heterozygosity by the upregulation of Nek2 in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2020 Dec 2;22(1):133. [CrossRef]

- Privitera, AP; Barresi, V; Condorelli, DF. Aberrations of Chromosomes 1 and 16 in Breast Cancer: A Framework for Cooperation of Transcriptionally Dysregulated Genes. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Mar 30;13(7):1585. [CrossRef]

- Krings, G; Shamir, ER; Shelley Hwang, E; Chen, YY. Genetic Analysis of Early Neoplasia in the Breast: Next-Generation Sequencing of Flat Epithelial Atypia and Associated Ductal and Lobular Lesions. Mod Pathol. 2025 Jun 17;38(11):100820. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, F; Li, Y; Liu, H; Luo, J. Single-cell and Spatial Transcriptomic Analyses Implicate Formation of the Immunosuppressive Microenvironment during Breast Tumor Progression. J Immunol. 2024 Nov 1;213(9):1392-1401. [CrossRef]

- Fasching, PA; Hu, C; Hart, SN; Ruebner, M; Polley, EC; Gnanaolivu, RD; Hartkopf, AD; Huebner, H; Janni, W; Hadji, P; Tesch, H; Uhrig, S; Ettl, J; Lux, MP; Lüftner, D; Wallwiener, M; Wurmthaler, LA; Goossens, C; Müller, V; Beckmann, MW; Hein, A; Anetsberger, D; Belleville, E; Wimberger, P; Untch, M; Ekici, AB; Kolberg, HC; Hartmann, A; Taran, FA; Fehm, TN; Wallwiener, D; Brucker, SY; Schneeweiss, A; Häberle, L; Couch, FJ. Susceptibility gene mutations in germline and tumors of patients with HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2024 Jul 13;10(1):57. [CrossRef]

- Walter, C; Hartkopf, A; Koch, A; Klaumünzer, M; Schulze, M; Grischke, EM; Taran, FA; Brucker, S; Battke, F; Biskup, S. Sequencing for an interdisciplinary molecular tumor board in patients with advanced breast cancer: experiences from a case series. Oncotarget. 2020 Sep 1;11(35):3279-3285. [CrossRef]

- Daoud, SA; Ismail, WM; Abdelhamid, MS; Nabil, TM; Daoud, SA. Possible Prognostic Role of HER2/Neu in Ductal Carcinoma In Situ and Atypical Ductal Proliferative Lesions of the Breast. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016, 17(8), 3733–6. [Google Scholar]

- Niwińska, A; Olszewski, WP. The role of stromal immune microenvironment in the progression of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) to invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2021 Dec 24;23(1):118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, LC; Radisky, DC; Frost, MH; Santen, RJ; Vierkant, RA; Benetti, LL; Tarabishy, Y; Ghosh, K; Visscher, DW; Degnim, AC. Understanding the premalignant potential of atypical hyperplasia through its natural history: a longitudinal cohort study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014 Feb;7(2):211-7. Epub 2014 Jan 30. [CrossRef]

- Mascharak, S; Guo, JL; Foster, DS; Khan, A; Davitt, MF; Nguyen, AT; Burcham, AR; Chinta, MS; Guardino, NJ; Griffin, M; Lopez, DM; Miller, E; Januszyk, M; Raghavan, SS; Longacre, TA; Delitto, DJ; Norton, JA; Longaker, MT. Desmoplastic stromal signatures predict patient outcomes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep Med. 2023 Nov 21;4(11):101248. Epub 2023 Oct 20. [CrossRef]

- Gierach, GL; Brinton, LA; Sherman, ME. Lobular involution, mammographic density, and breast cancer risk: visualizing the future? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010 Nov 17;102(22):1685-7. Epub 2010 Oct 29. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H; Wu, L; Yan, G; Chen, Y; Zhou, M; Wu, Y; Li, Y. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021 Jul 12;6(1):263. [CrossRef]

- Greene, AJE; Davis, J; Moon, J; Dubin, I; Cruz, A; Gupta, M; Moazzez, A; Ozao-Choy, J; Gupta, E; Manchandia, T; Kalantari, BN; Rahbar, G; Dauphine, C. Determination of Factors Associated with Upstage in Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia to Identify Low-Risk Patients Where Active Surveillance May be an Alternative. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024 May;31(5):3177-3185. Epub 2024 Feb 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rageth, CJ; Rubenov, R; Bronz, C; Dietrich, D; Tausch, C; Rodewald, AK; Varga, Z. Atypical ductal hyperplasia and the risk of underestimation: tissue sampling method, multifocality, and associated calcification significantly influence the diagnostic upgrade rate based on subsequent surgical specimens. Breast Cancer. 2019 Jul;26(4):452-458. Epub 2018 Dec 27. Erratum in: Breast Cancer. 2021 Jan;28(1):246. doi: 10.1007/s12282-020-01186-w. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornell, LF; Klassen, CL; Ghosh, K; Ball, C; Advani, P; Pruthi, S. Improved Uptake and Adherence to Risk-Reducing Medication with the Use of Low-Dose Tamoxifen in Patients at High Risk for Breast Cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2024 Dec 3;17(12):565-570. [CrossRef]

- Vamre, TB; Stalsberg, H; Thomas, DB. WHO Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives. Extra-tumoral breast tissue in breast cancer patients: variations with steroid contraceptive use. Int J Cancer. 2006 Jun 1;118(11):2827-31.

- Urrutia, AA; Mesa-Ciller, C; Guajardo-Grence, A; Alkan, HF; Soro-Arnáiz, I; Vandekeere, A; Ferreira Campos, AM; Igelmann, S; Fernández-Arroyo, L; Rinaldi, G; Lorendeau, D; De Bock, K; Fendt, SM; Aragonés, J. HIF1α-dependent uncoupling of glycolysis suppresses tumor cell proliferation. Cell Rep. 2024 Apr 23;43(4):114103. Epub 2024 Apr 11. [CrossRef]

- Wood, CE; Hester, JM; Appt, SE; Geisinger, KR; Cline, JM. Estrogen effects on epithelial proliferation and benign proliferative lesions in the postmenopausal primate mammary gland. Lab Invest. 2008 Sep;88(9):938-48. Epub 2008 Jul 7. [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, L; Mahalingaiah, PK S; Chang, YW; Singh, KP. Role of cellular reprogramming and epigenetic dysregulation in acquired chemoresistance in breast cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019, 2, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwiche, N. Epigenetic mechanisms and the hallmarks of cancer: an intimate affair. Am J Cancer Res. 2020 Jul 1;10(7):1954-1978.

- Muñoz, P; Iliou, MS; Esteller, M. Epigenetic alterations involved in cancer stem cell reprogramming. Mol Oncol. 2012 Dec;6(6):620-36. Epub 2012 Oct 26. [CrossRef]

- Daniel Romero-Mujalli, Laura I R Fuchs, Martin Haase, Jan-Peter Hildebrandt, Franz J Weissing, Tomás A Revilla, Emergence of phenotypic plasticity through epigenetic mechanisms, Evolution Letters, Volume 8, Issue 4, August 2024, Pages 561–574. [CrossRef]

- Connolly, R; Stearns, V. Epigenetics as a therapeutic target in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2012 Dec;17(3-4):191-204. [CrossRef]

- Goovaerts, T.; Steyaert, S.; Vandenbussche, C.A.; et al. A comprehensive overview of genomic imprinting in breast and its deregulation in cancer. Nat Commun 9, 4120 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Baran, Y; Subramaniam, M; Biton, A; Tukiainen, T; Tsang, EK; Rivas, MA; Pirinen, M; Gutierrez-Arcelus, M; Smith, KS; Kukurba, KR; Zhang, R; Eng, C; Torgerson, DG; Urbanek, C; Li, JB; Rodriguez-Santana, JR; Burchard, EG; Seibold, MA; MacArthur, DG; Montgomery, SB; Zaitlen, NA; Lappalainen, T.; GTEx Consortium. The landscape of genomic imprinting across diverse adult human tissues. Genome Res. 2015 Jul;25(7):927-36. Epub 2015 May 7. [CrossRef]

- Maupetit-Méhouas, S; Montibus, B; Nury, D; Tayama, C; Wassef, M; Kota, SK; Fogli, A; Cerqueira Campos, F; Hata, K; Feil, R; Margueron, R; Nakabayashi, K; Court, F; Arnaud, P. Imprinting control regions (ICRs) are marked by mono-allelic bivalent chromatin when transcriptionally inactive. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Jan 29;44(2):621-35. Epub 2015 Sep 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, A; Jiang, L; Lu, F; Suzuki, T; Zhang, Y. Maternal H3K27me3 controls DNA methylation-independent imprinting. Nature. 2017 Jul 27;547(7664):419-424. Epub 2017 Jul 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsthemke, B. In brief: genomic imprinting and imprinting diseases. J Pathol. 2014 Apr;232(5):485-7. Epub 2014 Jan 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, K; Hoad, G; Scott, P; Simpson, L; Horgan, GW; Smyth, E; Heys, SD; Haggarty, P. Breast cancer risk and imprinting methylation in blood. Clin Epigenetics. 2015 Sep 4;7(1):92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, MT; Coussement, L; De Meyer, T. Characterization of Loss-of-Imprinting in Breast Cancer at the Cellular Level by Integrating Single-Cell Full-Length Transcriptome with Bulk RNA-Seq Data. Biomolecules. 2024 Dec 14;14(12):1598. 1598. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H; Li, Z; Wang, Z; Zhang, X; Dai, X; Zhou, G; Ding, Q. Histocompatibility Minor 13 (HM13), targeted by miR-760, exerts oncogenic role in breast cancer by suppressing autophagy and activating PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2022 Sep 25;13(8):728. [CrossRef]

- Skaar, DA; Dietze, EC; Alva-Ornelas, JA; Ann, D; Schones, DE; Hyslop, T; Sistrunk, C; Zalles, C; Ambrose, A; Kennedy, K; Idassi, O; Miranda Carboni, G; Gould, MN; Jirtle, RL; Seewaldt, VL. Epigenetic Dysregulation of KCNK9 Imprinting and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Nov 30;13(23):6031. 6031. [CrossRef]

- Cui, H. Loss of imprinting of IGF2 as an epigenetic marker for the risk of human cancer. Dis Markers 2007, 23(1-2), 105–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z; Li, Y; Kong, D; Sarkar, FH. The role of Notch signaling pathway in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) during development and tumor aggressiveness. Curr Drug Targets. 2010 Jun;11(6):745-51. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X; Fan, D. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cells: functional and mechanistic links. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21(10):1279-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W; Qin, Y; Liu, S. Cytokines, breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) and chemoresistance. Clin Transl Med. 2018 Sep 3;7(1):27. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W; Glöckner, SC; Guo, M; Machida, EO; Wang, DH; Easwaran, H; Van Neste, L; Herman, JG; Schuebel, KE; Watkins, DN; Ahuja, N; Baylin, SB. Epigenetic inactivation of the canonical Wnt antagonist SRY-box containing gene 17 in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2008 Apr 15;68(8):2764-72. Erratum in: Cancer Res. 2008 Jul 15;68(14):6030. [CrossRef]

- Li, X; Gonzalez, ME; Toy, K; Filzen, T; Merajver, SD; Kleer, CG. Targeted overexpression of EZH2 in the mammary gland disrupts ductal morphogenesis and causes epithelial hyperplasia. Am J Pathol. 2009 Sep;175(3):1246-54. Epub 2009 Aug 6. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X; Tan, J; Li, J; Kivimäe, S; Yang, X; Zhuang, L; Lee, PL; Chan, MT; Stanton, LW; Liu, ET; Cheyette, BN; Yu, Q. DACT3 is an epigenetic regulator of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer and is a therapeutic target of histone modifications. 2008 Jun;13(6):529-41. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M; Rao, M; Humphries, AE; Hong, JA; Liu, F; Yang, M; Caragacianu, D; Schrump, DS. Tobacco smoke induces polycomb-mediated repression of Dickkopf-1 in lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009 Apr 15;69(8):3570-8. Epub 2009 Apr 7. [CrossRef]

- Inui, M; Martello, G; Piccolo, S. MicroRNA control of signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010 Apr;11(4):252-63. Epub 2010 Mar 10. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, Y; Katoh, M. Hedgehog target genes: mechanisms of carcinogenesis induced by aberrant hedgehog signaling activation. Curr Mol Med. 2009 Sep;9(7):873-86. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J; Hui, CC. Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2008 Dec;15(6):801-12. [CrossRef]

- Sakaki-Yumoto, M; Katsuno, Y; Derynck, R. TGF-β family signaling in stem cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Feb;1830(2):2280-96. Epub 2012 Aug 16. [CrossRef]

- Du, J; Yang, S; An, D; Hu, F; Yuan, W; Zhai, C; Zhu, T. BMP-6 inhibits microRNA-21 expression in breast cancer through repressing deltaEF1 and AP-1. Cell Res. 2009 Apr;19(4):487-96. [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M; Hu, JJ; Liang, J; He, CY; Wan, WD; Huang, YQ; Jiang, CH; Wu, H; Li, N. Hallmarks of cancer resistance. iScience. 2024 May 15;27(6):109979. [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, EN; Scaffidi, P. Epigenetics and Cancer Stem Cells: Unleashing, Hijacking, and Restricting Cellular Plasticity. Trends Cancer. 2017 May;3(5):372-386. Epub 2017 May 5. [CrossRef]

- Shi, ZD; Pang, K; Wu, ZX; Dong, Y; Hao, L; Qin, JX; Wang, W; Chen, ZS; Han, CH. Tumor cell plasticity in targeted therapy-induced resistance: mechanisms and new strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Mar 11;8(1):113. [CrossRef]

- Pang, L; Zhou, F; Liu, Y; Ali, H; Khan, F; Heimberger, AB; Chen, P. Epigenetic regulation of tumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2024 Jun 17;134(12):e178540. [CrossRef]

- Hoque, MO; Prencipe, M; Poeta, ML; Barbano, R; Valori, VM; Copetti, M; Gallo, AP; Brait, M; Maiello, E; Apicella, A; Rossiello, R; Zito, F; Stefania, T; Paradiso, A; Carella, M; Dallapiccola, B; Murgo, R; Carosi, I; Bisceglia, M; Fazio, VM; Sidransky, D; Parrella, P. Changes in CpG islands promoter methylation patterns during ductal breast carcinoma progression. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009 Oct;18(10):2694-700. Epub 2009 Sep 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison BT, D’Alfonso TM, Schnitt SJ. Columnar cell lesions and flat epithelial atypia. In: Shin SJ, Chen YY, Ginter PS, editors. A Comprehensive Guide to Core Needle Biopsies of the Breast. Cham: Springer; 2022. p. 331-350. [CrossRef]

- Otterlei Fjørtoft, M; Huse, K; Rye, IH. The Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Breast Cancer Progression. Acta Oncol. 2024 May 23;63:359-367. [CrossRef]

- Kim, A; Mo, K; Kwon, H; Choe, S; Park, M; Kwak, W; Yoon, H. Epigenetic Regulation in Breast Cancer: Insights on Epidrugs. Epigenomes. 2023 Feb 18;7(1):6. 6. [CrossRef]

- Brena, D; Huang, MB; Bond, V. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transport: Reprogramming a tumor microenvironment conducive with breast cancer progression and metastasis. Transl Oncol. 2022 Jan;15(1):101286. Epub 2021 Nov 25. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y; Yang, D; Xi, L; Chen, Y; Fu, L; Sun, K; Yin, J; Li, X; Liu, S; Qin, Y; Liu, M; Hou, Y. Primed atypical ductal hyperplasia-associated fibroblasts promote cell growth and polarity changes of transformed epithelium-like breast cancer MCF-7 cells via miR-200b/c-IKKβ signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2018 Jan 26;9(2):122. [CrossRef]

- Casbas-Hernandez, P; D’Arcy, M; Roman-Perez, E; Brauer, HA; McNaughton, K; Miller, SM; Chhetri, RK; Oldenburg, AL; Fleming, JM; Amos, KD; Makowski, L; Troester, MA. Role of HGF in epithelial-stromal cell interactions during progression from benign breast disease to ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(5):R82. [CrossRef]

- Borowsky, A; Glencer, A; Ramalingam, K; Schindler, N; Mori, H; Ghule, P; Lee, K; Nachmanson, D; Officer, A; Harismendy, O; Stein, J; Stein, G; Evans, M; Weaver, D; Yau, C; Hirst, G; Campbell, M; Esserman, L. Tumor microenvironmental determinants of high-risk DCIS progression. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2024 May 9:rs.3.rs-4126092. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y; Sundaram, S; Essaid, L; Chen, X; Miller, SM; Yan, F; Darr, DB; Galanko, JA; Montgomery, SA; Major, MB; Johnson, GL; Troester, MA; Makowski, L. Weight loss reduces basal-like breast cancer through kinome reprogramming. Cancer Cell Int. 2016 Apr 1;16:26. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q; Yang, YM; Zhang, QH; Zhang, TG; Zhou, Q; Zhou, CJ. Inhibitor of differentiation is overexpressed with progression of benign to malignant lesions and related with carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 distribution in mammary glands. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011 Feb;15(1):30-6. Epub 2010 Nov 24. [CrossRef]

- Pavlakis, K; Messini, I; Vrekoussis, T; Yiannou, P; Keramopoullos, D; Louvrou, N; Liakakos, T; Stathopoulos, EN. The assessment of angiogenesis and fibroblastic stromagenesis in hyperplastic and pre-invasive breast lesions. BMC Cancer. 2008 Apr 2;8:88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degnim, AC; Hoskin, TL; Arshad, M; Frost, MH; Winham, SJ; Brahmbhatt, RA; Pena, A; Carter, JM; Stallings-Mann, ML; Murphy, LM; Miller, EE; Denison, LA; Vachon, CM; Knutson, KL; Radisky, DC; Visscher, DW. Alterations in the Immune Cell Composition in Premalignant Breast Tissue that Precede Breast Cancer Development. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Jul 15;23(14):3945-3952. Epub 2017 Jan 26. [CrossRef]

- Kader, T; Provenzano, E; Jayawardana, MW; Hendry, S; Pang, JM; Elder, K; Byrne, DJ; Tjoeka, L; Frazer, HM; House, E; Jayasinghe, SI; Keane, H; Murugasu, A; Rajan, N; Miligy, IM; Toss, M; Green, AR; Rakha, EA; Fox, SB; Mann, GB; Campbell, IG; Gorringe, KL. Stromal lymphocytes are associated with upgrade of B3 breast lesions. Breast Cancer Res. 2024 Jul 8;26(1):115. [CrossRef]

- Borowsky, A; Glencer, A; Ramalingam, K; Schindler, N; Mori, H; Ghule, P; Lee, K; Nachmanson, D; Officer, A; Harismendy, O; Stein, J; Stein, G; Evans, M; Weaver, D; Yau, C; Hirst, G; Campbell, M; Esserman, L. Tumor microenvironmental determinants of high-risk DCIS progression. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2024 May 9:rs.3.rs-4126092. [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, I; Perego, M; Nefedova, Y; Lin, C; Milcarek, A; Vogel, P; Ghosh, JC; Kossenkov, AV; Altieri, DC. Intercellular hif1α reprograms mammary progenitors and myeloid immune evasion to drive high-risk breast lesions. J Clin Invest. 2023 Apr 17;133(8):e164348. [CrossRef]

- Cichon, MA; Degnim, AC; Visscher, DW; Radisky, DC. Microenvironmental influences that drive progression from benign breast disease to invasive breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010 Dec;15(4):389-97. [CrossRef]

- Kuziel, G; Moore, BN; Haugstad, GP; Xiong, Y; Williams, AE; Arendt, LM. Alterations in the mammary gland and tumor microenvironment of formerly obese mice. BMC Cancer. 2023 Dec 1;23(1):1183. [CrossRef]

- Bluff, JE; Menakuru, SR; Cross, SS; Higham, SE; Balasubramanian, SP; Brown, NJ; Reed, MW; Staton, CA. Angiogenesis is associated with the onset of hyperplasia in human ductal breast disease. Br J Cancer. 2009 Aug 18;101(4):666-72. Epub 2009 Jul 21. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, O; Nishimura, R; Miyayama, H; Yasunaga, T; Ozaki, Y; Tuji, A; Yamashita, Y. Evaluation of tumor angiogenesis using dynamic enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: comparison of plasma vascular endothelial growth factor, hemodynamic, and pharmacokinetic parameters. Acta Radiol. 2004 Jul;45(4):446-52. [CrossRef]

- Silva, P; Hernández, N; Tapia, H; Gaete-Ramírez, B; Torres, P; Flores, T; Herrera, D; Cáceres-Verschae, A; Acuña, RA; Varas-Godoy, M; Torres, VA. Tumor-derived hypoxic small extracellular vesicles promote endothelial cell migration and tube formation via ALS2/Rab5/β-catenin signaling. FASEB J. 2024 Jun 15;38(11):e23716. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J; Abisoye-Ogunniyan, A; Metcalf, KJ; Werb, Z. Concepts of extracellular matrix remodelling in tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Commun. 2020 Oct 9;11(1):5120. [CrossRef]

- Wang, JL; Sun, SZ; Qu, X; Liu, WJ; Wang, YY; Lv, CX; Sun, JZ; Ma, R. Clinicopathological significance of CEACAM1 gene expression in breast cancer. Chin J Physiol. 2011 Oct 31;54(5):332-8.

- Seo, BR; Bhardwaj, P; Choi, S; Gonzalez, J; Andresen Eguiluz, RC; Wang, K; Mohanan, S; Morris, PG; Du, B; Zhou, XK; Vahdat, LT; Verma, A; Elemento, O; Hudis, CA; Williams, RM; Gourdon, D; Dannenberg, AJ; Fischbach, C. Obesity-dependent changes in interstitial ECM mechanics promote breast tumorigenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2015 Aug 19;7(301):301ra130. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y; Meng, L; Bai, S; Li, S. Extracellular vesicles: the “Trojan Horse” within breast cancer host microenvironments. Mol Cancer. 2025 Jun 23;24(1):183. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brena, D; Huang, MB; Bond, V. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transport: Reprogramming a tumor microenvironment conducive with breast cancer progression and metastasis. Transl Oncol. 2022 Jan;15(1):101286. Epub 2021 Nov 25. [CrossRef]

- Sneider, A; Liu, Y; Starich, B; Du, W; Nair, PR; Marar, C; Faqih, N; Ciotti, GE; Kim, JH; Krishnan, S; Ibrahim, S; Igboko, M; Locke, A; Lewis, DM; Hong, H; Karl, MN; Vij, R; Russo, GC; Gómez-de-Mariscal, E; Habibi, M; Muñoz-Barrutia, A; Gu, L; Eisinger-Mathason, TSK; Wirtz, D. Small Extracellular Vesicles Promote Stiffness-mediated Metastasis. Cancer Res Commun. 2024 May 9;4(5):1240-1252. [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, RM; Spiegelman, D; Smith-Warner, SA; Wang, M; Pazaris, M; Willett, WC; Eliassen, AH; Hunter, DJ. Population Attributable Risk of Modifiable and Nonmodifiable Breast Cancer Risk Factors in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2016 Dec 15;184(12):884-8930. Epub 2016 Dec 6. [CrossRef]

- Seiler, A.; Chen, M. A.; Brown, R. L.; Fagundes, C. P. (2018). Obesity, Dietary Factors, Nutrition, and Breast Cancer Risk. Current breast cancer reports, 10(1), 14–27. [CrossRef]

- Uhomoibhi, T. O.; Okobi, T. J.; Okobi, O. E.; Koko, J. O.; Uhomoibhi, O.; Igbinosun, O. E.; Ehibor, U. D.; Boms, M. G.; Abdulgaffar, R. A.; Hammed, B. L.; Ibeanu, C.; Segun, E. O.; Adeosun, A. A.; Evbayekha, E. O.; Alex, K. B. (2022). High-Fat Diet as a Risk Factor for Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Cureus, 14(12), e32309. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, NF; Stone, J; Vogt, KN; Connelly, BS; Martin, LJ; Minkin, S. Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: a meta-analysis of the published literature. Br J Cancer. 2003 Nov 3;89(9):1672-85. [CrossRef]

- Khodarahmi, M; Azadbakht, L. The association between different kinds of fat intake and breast cancer risk in women. Int J Prev Med. 2014 Jan;5(1):6-15. [PubMed]

- Fay, MP; Freedman, LS; Clifford, CK; Midthune, DN. Effect of different types and amounts of fat on the development of mammary tumors in rodents: a review. Cancer Res. 1997 Sep 15;57(18):3979-88.

- Wirfält, E; Mattisson, I; Gullberg, B; Johansson, U; Olsson, H; Berglund, G. Postmenopausal breast cancer is associated with high intakes of omega6 fatty acids (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control. 2002 Dec;13(10):883-93. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J; Liu, X; Zou, Y; Gong, J; Ge, Z; Lin, X; Zhang, W; Huang, H; Zhao, J; Saw, PE; Lu, Y; Hu, H; Song, E. A high-fat diet promotes cancer progression by inducing gut microbiota-mediated leucine production and PMN-MDSC differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 May 14;121(20):e230677612. Epub 2024 May 6. [CrossRef]

- Hergueta-Redondo, M; Sánchez-Redondo, S; Hurtado, B; Santos, V; Pérez-Martínez, M; Ximénez-Embún, P; McDowell, SAC; Mazariegos, MS; Mata, G; Torres-Ruiz, R; Rodríguez-Perales, S; Martínez, L; Graña-Castro, O; Megias, D; Quail, D; Quintela-Fandino, M; Peinado, H. The impact of a high fat diet and platelet activation on pre-metastatic niche formation. Nat Commun. 2025 Apr 2;16(1):2897. [CrossRef]

- Rose, DP; Gracheck, PJ; Vona-Davis, L. The Interactions of Obesity, Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2015 Oct 26;7(4):2147-68. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, PJ; Stambolic, V. Obesity and insulin resistance in breast cancer--chemoprevention strategies with a focus on metformin. Breast. 2011 Oct;20 Suppl 3:S31-5. Erratum in: Breast. 2012 Apr;21(2):224. [CrossRef]

- Phipps, AI; Chlebowski, RT; Prentice, R; McTiernan, A; Stefanick, ML; Wactawski-Wende, J; Kuller, LH; Adams-Campbell, LL; Lane, D; Vitolins, M; Kabat, GC; Rohan, TE; Li, CI. Body size, physical activity, and risk of triple-negative and estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011 Mar;20(3):454-63. Epub 2011 Mar 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protani, M; Coory, M; Martin, JH. Effect of obesity on survival of women with breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 Oct;123(3):627-35. Epub 2010 Jun 23. [CrossRef]

- Javed, SR; Skolariki, A; Zameer, MZ; Lord, SR. Implications of obesity and insulin resistance for the treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2024 Dec;131(11):1724-1736. Epub 2024 Sep 9. [CrossRef]

- Dehesh, T; Fadaghi, S; Seyedi, M; Abolhadi, E; Ilaghi, M; Shams, P; Ajam, F; Mosleh-Shirazi, MA; Dehesh, P. The relation between obesity and breast cancer risk in women by considering menstruation status and geographical variations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health. 2023 Jul 26;23(1):392. [CrossRef]

- Chan, DSM; Vieira, AR; Aune, D; Bandera, EV; Greenwood, DC; McTiernan, A; Navarro Rosenblatt, D; Thune, I; Vieira, R; Norat, T. Body mass index and survival in women with breast cancer-systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 82 follow-up studies. Ann Oncol. 2014 Oct;25(10):1901-1914. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shami, K; Awadi, S; Khamees, A; Alsheikh, AM; Al-Sharif, S; Ala’ Bereshy, R; Al-Eitan, SF; Banikhaled, SH; Al-Qudimat, AR; Al-Zoubi, RM; Al Zoubi, MS. Estrogens and the risk of breast cancer: A narrative review of literature. Heliyon. 2023 Sep 17;9(9):e20224. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossmann, ME; Nkhata, KJ; Mizuno, NK; Ray, A; Cleary, MP. Effects of adiponectin on breast cancer cell growth and signaling. Br J Cancer. 2008 Jan 29;98(2):370-9. Epub 2008 Jan 8. [CrossRef]

- Caffa, I; Spagnolo, V; Vernieri, C; Valdemarin, F; Becherini, P; Wei, M; Brandhorst, S; Zucal, C; Driehuis, E; Ferrando, L; Piacente, F; Tagliafico, A; Cilli, M; Mastracci, L; Vellone, VG; Piazza, S; Cremonini, AL; Gradaschi, R; Mantero, C; Passalacqua, M; Ballestrero, A; Zoppoli, G; Cea, M; Arrighi, A; Odetti, P; Monacelli, F; Salvadori, G; Cortellino, S; Clevers, H; De Braud, F; Sukkar, SG; Provenzani, A; Longo, VD; Nencioni, A. Fasting-mimicking diet and hormone therapy induce breast cancer regression. Nature. 2020 Jul;583(7817):620-624. Epub 2020 Jul 15. Erratum in: Nature. 2020 Dec;588(7839):E33. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2957-6. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, NM; Zhou, XK; Gucalp, A; Morris, PG; Howe, LR; Giri, DD; Morrow, M; Wang, H; Pollak, M; Jones, LW; Hudis, CA; Dannenberg, AJ. Systemic Correlates of White Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016 May 1;22(9):2283-9. Epub 2015 Dec 28. [CrossRef]

- Chang, MC; Eslami, Z; Ennis, M; Goodwin, PJ. Crown-like structures in breast adipose tissue of breast cancer patients: associations with CD68 expression, obesity, metabolic factors and prognosis. [CrossRef]

- Birts, CN; Savva, C; Laversin, SA; Lefas, A; Krishnan, J; Schapira, A; Ashton-Key, M; Crispin, M; Johnson, PWM; Blaydes, JP; Copson, E; Cutress, RI; Beers, SA. Prognostic significance of crown-like structures to trastuzumab response in patients with primary invasive HER2 + breast carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2022 May 24;12(1):7802. [CrossRef]

- Hill, AA; Anderson-Baucum, EK; Kennedy, AJ; Webb, CD; Yull, FE; Hasty, AH. Activation of NF-κB drives the enhanced survival of adipose tissue macrophages in an obesogenic environment. Mol Metab. 2015 Jul 28;4(10):665-77. [CrossRef]

- Takikawa, A; Mahmood, A; Nawaz, A; Kado, T; Okabe, K; Yamamoto, S; Aminuddin, A; Senda, S; Tsuneyama, K; Ikutani, M; Watanabe, Y; Igarashi, Y; Nagai, Y; Takatsu, K; Koizumi, K; Imura, J; Goda, N; Sasahara, M; Matsumoto, M; Saeki, K; Nakagawa, T; Fujisaka, S; Usui, I; Tobe, K. HIF-1α in Myeloid Cells Promotes Adipose Tissue Remodeling Toward Insulin Resistance. Diabetes. 2016 Dec;65(12):3649-3659. Epub 2016 Sep 13. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, RA; Bhat-Nakshatri, P; Patel, NM; Constantinidou, D; Ali, S; Nakshatri, H. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT-mediated activation of estrogen receptor alpha: a new model for anti-estrogen resistance. J Biol Chem. 2001 Mar 30;276(13):9817-24. Epub 2001 Jan 3. [CrossRef]

- Denduluri, SK; Idowu, O; Wang, Z; Liao, Z; Yan, Z; Mohammed, MK; Ye, J; Wei, Q; Wang, J; Zhao, L; Luu, HH. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling in tumorigenesis and the development of cancer drug resistance. Genes Dis. 2015 Mar 1;2(1):13-25. [CrossRef]

- Sohi, I; Rehm, J; Saab, M; Virmani, L; Franklin, A; Sánchez, G; Jhumi, M; Irshad, A; Shah, H; Correia, D; Ferrari, P; Ferreira-Borges, C; Lauby-Secretan, B; Galea, G; Gapstur, S; Neufeld, M; Rumgay, H; Soerjomataram, I; Shield, K. Alcoholic beverage consumption and female breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (Hoboken). 2024 Dec;48(12):2222-2241. Epub 2024 Nov 24. [CrossRef]

- Fanfarillo, F; Caronti, B; Lucarelli, M; Francati, S; Tarani, L; Ceccanti, M; Piccioni, MG; Verdone, L; Caserta, M; Venditti, S; Ferraguti, G; Fiore, M. Alcohol Consumption and Breast and Ovarian Cancer Development: Molecular Pathways and Mechanisms. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024 Dec 20;46(12):14438-14452. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, RA. Phytoestrogens. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:225-61. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 225–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, ZQ. What about the progress in the synthesis of flavonoid from 2020? Eur J Med Chem. 2022 Dec 5;243:114671. Epub 2022 Aug 27. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, VC; Mittal, S; Gosden, B; Koch, R; Lieberman, ME. Structure-activity relationships of estrogens. Environ Health Perspect. 1985 Sep;61:97-110. [CrossRef]

- Hamblen, EL; Cronin, MT; Schultz, TW. Estrogenicity and acute toxicity of selected anilines using a recombinant yeast assay. Chemosphere. 2003 Aug;52(7):1173-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teegarden, D; Romieu, I; Lelièvre, SA. Redefining the impact of nutrition on breast cancer incidence: is epigenetics involved? Nutr Res Rev. 2012 Jun;25(1):68-95. [CrossRef]

- Zengul, AG; Demark-Wahnefried, W; Barnes, S; Morrow, CD; Bertrand, B; Berryhill, TF; Frugé, AD. Associations between Dietary Fiber, the Fecal Microbiota and Estrogen Metabolism in Postmenopausal Women with Breast Cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73(7):1108-1117. Epub 2020 Jun 26. [CrossRef]

- Brody, JG; Rudel, RA. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 2003 Jun;111(8):1007-19. [CrossRef]

- Datta, K; Hyduke, DR; Suman, S; Moon, BH; Johnson, MD; Fornace, AJ, Jr. Exposure to ionizing radiation induced persistent gene expression changes in mouse mammary gland. Radiat Oncol. 2012 Dec 5;7:205. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, O; Batten, KG; Richardson, JA; Xie, XJ; Gazdar, AF; Kaisani, AA; Girard, L; Behrens, C; Suraokar, M; Fasciani, G; Wright, WE; Story, MD; Wistuba, II; Minna, JD; Shay, JW. Radiation-enhanced lung cancer progression in a transgenic mouse model of lung cancer is predictive of outcomes in human lung and breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014 Mar 15;20(6):1610-22. Epub 2014 Jan 31. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, PRS; Oliveira, VD; Vasques, CI; Dos Reis, PED; Amato, AA. Exposure to endocrine disruptors and risk of breast cancer: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021 May;161:103330. Epub 2021 Apr 20. [CrossRef]

- Williams, GP; Darbre, PD. Low-dose environmental endocrine disruptors, increase aromatase activity, estradiol biosynthesis and cell proliferation in human breast cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2019 Apr 15;486:55-64. Epub 2019 Feb 26. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y. Potential Pro-Tumorigenic Effect of Bisphenol A in Breast Cancer via Altering the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Jun 19;14(12):3021. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C; Lazennec, G; Vogel, CFA. Environmental exposure and the role of AhR in the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Dec 15;13:1095289. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q; Wang, X; Gao, Y; Zhou, J; Huang, C; Zhang, Z; Chu, H. Relationship between particulate matter exposure and female breast cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2021 Feb;94(2):191-201. Epub 2020 Sep 10. [CrossRef]

- Lichtiger, L; Rivera, J; Sahay, D; Miller, RL. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Mammary Cancer Risk: Does Obesity Matter too? J Cancer Immunol (Wilmington). 2021;3(3):154-162. J Cancer Immunol (Wilmington) 2021, 3(3), 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Panis, C; Candiotto, LZP; Gaboardi, SC; Teixeira, GT; Alves, FM; da Silva, JC; Scandolara, TB; Rech, D; Gurzenda, S; Ponmattam, J; Ohm, J; Castro, MC; Lemos, B. Exposure to Pesticides and Breast Cancer in an Agricultural Region in Brazil. Environ Sci Technol. 2024 Jun 18;58(24):10470-10481. Epub 2024 Jun 6. [CrossRef]

- Tayour, C; Ritz, B; Langholz, B; Mills, PK; Wu, A; Wilson, JP; Shahabi, K; Cockburn, M. A case-control study of breast cancer risk and ambient exposure to pesticides. Environ Epidemiol. 2019 Oct 14;3(5):e070. [CrossRef]

- Snedeker, SM. Pesticides and breast cancer risk: a review of DDT, DDE, and dieldrin. Environ Health Perspect. 2001 Mar;109 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):35-47. [CrossRef]

| Lesion Type | Characteristic genetic alterations (mutations and copy number changes) |

|---|---|

| Usual Ductal Hyperplasia (UDH) | Polyclonal proliferation with minimal or no clonal driver mutations. Occasional activating PI3K-AKT pathway mutations (e.g., PIK3CA hotspot mutations) have been detected. It lacks consistent chromosomal aberrations; considered a benign hyperplastic response rather than true neoplasia. [50] |

| Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia (ADH) | Clonal neoplastic lesion sharing many alterations with low-grade DCIS. Frequent PIK3CA mutations (on the order of 30-40% of cases). Loss of chromosome 16q (harboring CDH1 and other genes) is common. Other recurrent mutations in luminal breast cancer genes (e.g., GATA3, MAP3K1, CBFB genes) may be present. Overall, ADH exhibits a luminal A-like genomic profile indicative of early cancerous change. [53] |

| Atypical Lobular Hyperplasia (ALH) | Almost uniformly associated with E-cadherin loss due to CDH1 gene inactivation. This occurs via CDH1 gene mutation or 16q LOH in the majority of cases. Often accompanied by PIK3CA gene mutations similar to those in invasive lobular carcinoma. Occasional mutations in AKT1 or PTEN genes are reported. The genetic pattern overlaps with ER-positive lobular carcinoma, minus additional alterations required for invasion [52]. |

| Columnar Cell Lesions (CCL) and Flat epithelial atypia (FEA) |

High frequency of early oncogenic mutations despite bland histology. PIK3CA gene activating mutations are present in 50-60% of cases, making this a hallmark of FEA/CCLs. Some cases show modest copy number changes (e.g., gains on 1q; losses on 16q or 17p). Clonal relationship to adjacent ADH/DCIS is evidenced by shared mutations, supporting CCL/FEA as the earliest morphologic precursor in low-grade tumor evolution. [53]. |

| Gene/locus | Pathway/function | Frequent alterations in ADH/FEA | Pathological implication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIK3CA | PI3K/AKT signaling (oncogene) | H1047R, E545K, E542K (missense mutations) | Frequent in FEA/ADH and luminal DCIS/IBC; early driver; sustained proliferation; defines low-grade pathway | [54] |

| TP53 | Genome integrity/ apoptosis (tumor suppressor) |

R175H, R248Q/W, R273H/C (missense mutations) |

Subset of atypia/DCIS on progression trajectory; common in high-grade disease; often with ERBB2 amplification | [52] |

| BRCA1 | Homologous recombination DNA repair (tumor suppressor) |

c.68_69delAG (185delAG), c.5266dupC (5382insC); numerous truncations | High-risk hereditary context; genomic instability in early clones | [55] |

| BRCA2 | Homologous recombination DNA repair (tumor suppressor) |

Multiple frameshifts/nonsense variants across exons | High-risk hereditary context; facilitates mutation accumulation | [56] |

| GATA3 | Luminal lineage transcription Factor | Frameshift/truncations; splice-site alterations | Supports luminal differentiation program in HR+ precursors | [57] |

| CDH1 | E-cadherin; cell–cell adhesion (tumor suppressor) |

Bi-allelic inactivation/truncating mutations | Marks the lobular pathway (atypical lobular hyperplasia to lobular carcinoma) | [58] |

| AKT1 | Serine/threonine kinase downstream of PI3K (oncogene) |

E17K (PH domain hotspot) | Activates AKT independent of PI3K, specific to HR+ lesions | [59] |

| PTEN | PI3K negative regulator; lipid phosphatase (tumor suppressor) |

Loss-of-function mutations/deletions; promoter silencing | Cooperates with PIK3CA activation in atypia/DCIS | [50] |

| ERBB2 (HER2) | Receptor tyrosine kinase (oncogene) |

Amplification; S310F/Y; Y772_A775dup (kinase insertion) | Low-level expression in some early lesions; targetable alterations | [60] |

| ERBB3 (HER3) | Receptor tyrosine kinase; dimerizes with HER2 | E928G and kinase-domain substitutions | Co-occurs with ERBB2 mutations; luminal contexts | [62] |

| RUNX1/ CBFB | Core-binding factor complex; lineage and differentiation | RUNX1 Runt domain loss-of-function; CBFB alterations | Luminal tumors/precursors; tumor-suppressor roles | [50] |

| MAP3K1 | MAPK signaling; luminal A-associated | Multiple truncations/missense; pathway-inactivating | Co-mutation patterns with PIK3CA/CBFB in luminal A | [58] |

| ESR1 | Estrogen receptor alpha (nuclear receptor) |

Ligand-binding domain: Y537S, D538G (rare in primary) | Rare in early lesions; prevalent in endocrine-resistant metastases | [61] |

| FOXA1 | Pioneer transcription factor for ER program | Wing2/DBD hotspots (e.g., R219); indels affecting DNA binding | Luminal program maintenance in HR+ tumors; early presence reported | [62] |

| KMT2C (MLL3)/ KMT2D (MLL2) | Histone H3K4 methyltransferases (chromatin modifier) | Truncating mutations across coding exons | Epigenetic deregulation in luminal tumors/precursors | [63] |

| ARID1A/ ARID1B | SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex (tumor suppressor) | Frameshift/nonsense mutations; loss of protein expression | Subset of HR+/basal lesions; chromatin accessibility shifts | [64] |

| NCOR1/ NCOR2 | Nuclear receptor co-repressors; ER signaling modulation | Truncations and splice variants | Associated with endocrine response and luminal programs | [65] |

| CREBBP/ EP300 | Histone acetyltransferases; transcriptional co-activators | Loss-of-function mutations | Transcriptional reprogramming in early neoplasia | [68] |

| PIK3R1 | PI3K regulatory subunit p85α (tumor suppressor-like) |

Truncations/indels disrupting SH2 domains | Cooperates with PIK3CA in PI3K activation | [54] |

| NOTCH1 | NOTCH signaling (context-dependent) | PEST-domain truncations; activating mutations | Subset of breast lesions; cross-talk with ER and PI3K | [52] |

| Lesion type/stage | Epigenetic alterations |

|---|---|

| Early proliferative lesions (UDH, mild hyperplasia) |

Subtle epigenetic deviations may begin. Global DNA methylation levels start to increase in proliferative breast tissue. Promoter methylation is generally low in UDH, but isolated foci can show initial methylation of genes like RASSF1A. Histones in UDH largely retain normal patterns, although minor shifts toward a more closed chromatin conformation have been noted in high-risk patients. MiRNA expression is near-normal, aside from slight upregulation of proliferative miRNAs (e.g., miR-21) in some cases. Overall, UDH lacks the pronounced epigenetic silencing seen in atypia [144]. |

| Atypical hyperplasias (ADH, ALH, FEA) |

Promoter hypermethylation becomes common and non-random. Frequent methylation of tumor suppressor genes (e.g., RASSF1A, APC) is documented in ADH and FEA lesions. In lobular neoplasia, CDH1 promoter methylation is an alternative mechanism to gene mutation for turning off E-cadherin [62]. These methylation marks often coexist with repressive histone modifications; for instance, hypermethylated genes show enriched H3K27me3 and decreased acetylation, reinforcing chromatin compaction. Genome-wide, atypical lesions exhibit a shift toward a cancer-like epigenome with dozens of genes epigenetically silenced. MicroRNA profiles are significantly altered: oncomiRs such as miR-21 and miR-155 are elevated in ADH, correlating with suppressed PTEN and TP53 pathways [145]. Conversely, certain anti-proliferative miRNAs (e.g., miR-1297, miR-125b) are downregulated in FEA/ADH [62]. These changes act in concert to disable cell-cycle checkpoints and promote survival, thereby potentiating progression to carcinoma in situ. |

| Carcinoma in situ (DCIS, LCIS) |

Widespread epigenetic reprogramming is present. DCIS lesions show hypermethylation at numerous loci, e.g., more than 40% of DCIS cases have RASSF1A gene methylation [71], and many harbor methylation of p16, cyclin D2, and others. LCIS (especially pleomorphic LCIS) likewise accumulates methylation events, though classical LCIS may rely more on CDH1 loss by mutation. Global DNA hypomethylation begins to be evident in carcinoma in situ, contributing to genomic instability. Histone modification patterns are clearly abnormal: high levels of HDACs lead to histone hypoacetylation, and Polycomb complexes maintain silencing of differentiation genes. MicroRNAs in CIS lesions often mirror invasive cancer profiles; for example, miR-21 and miR-210 are strongly up, while miR-205 (an anti-Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) miRNA is down. Such miRNA dysregulation in CIS has been linked with aggressive features and may predict which in situ lesions are likely to invade [72]. |

| Mechanism | Gene targets/factor | Molecular results in ADH/DCIS | Functional consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter hypermethylation (DNA) | RASSF1, CDKN2A (p16INK4a), BRCA1, PTEN | Stable silencing of tumor suppressors | Loss of cell cycle arrest; early event in monoclonal progression [146] |

| Oncogene hypomethylation (DNA) | HER2, CCND1 (Cyclin D1) | Transcriptional increase | Overexpression of proliferation drivers [147] |

| Non-coding RNA dysregulation | miR-21 (Upregulation) | Post-transcriptional inhibition of PTEN | Constitutive activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway; promotes survival [148] |

| Histone modifications/remodeling | KMT2C/D, EZH2 | Aberrant acetylation/methylation patterns | Transcriptional reprogramming for malignant phenotype [49] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).