Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

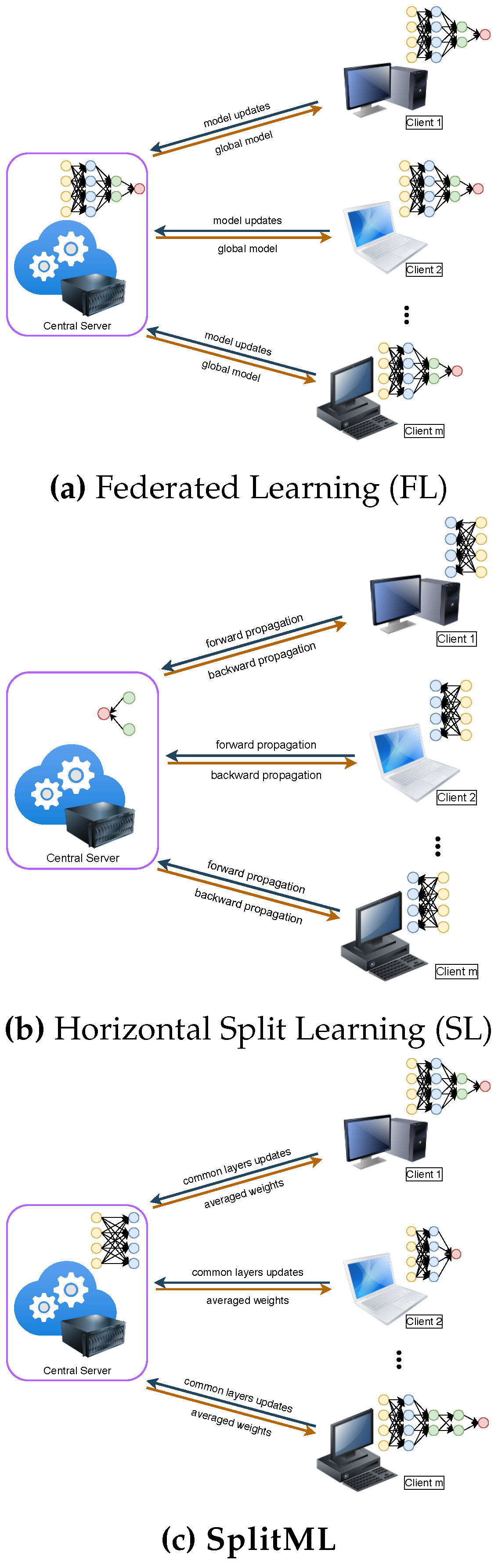

- We formalize FL and SL and present SplitML, a fused FL (for training) and SL (for inference) partitioned between ML model layers to reduce information leakage. The novelty stems from clients collaborating on partial models (instead of full models in FL) to enhance collaboration while reducing privacy risks. While federation helps improve feature extraction, horizontal splitting allows entities to personalize their models concerning their specific environments, thus improving results.

- SplitML implements multi-key FHE with DP during training to protect against clients colluding with each other or a server colluding with clients under an honest-but-curious assumption. SplitML reduces time compared to training in silo while upholding privacy with security.

- We propose a novel privacy-preserving counseling process for inference. An entity can request a consensus by submitting an encrypted classification query using single-key FHE with DP to its peers.

- We empirically show that SplitML is robust against various threats such as poisoning and inference attacks.

2. Our Framework

2.1. Threat Model

2.2. Proposed Architecture

| Algorithm 1 Public and Secret Keys Generation |

|

Input: Each client performs iteratively

Output: Public and private keypairs for each client

|

| Algorithm 2 Evaluation Keys Generation for Addition |

|

Input: Keypairs for each client

Output: Evaluation key for Addition

|

| Algorithm 3 Evaluation Keys Generation for Multiplication |

|

Input: Keypairs for each client

Output: Evaluation key for Multiplication

|

| Algorithm 4 Training |

|

Input:

Output: Trained models for each client

|

| Algorithm 5 Inference |

|

Input: Data subset from client

Output: Class labels or predictions scores from clients

|

- SplitML can generalize Federate Learning (FL) with a parameter over model layers, where controls the proportion of layers to collaborate on. Thus, FL is realized when clients collaborate to train all layers of the global ML model M; hence, . A value of indicates no collaboration, thus .

- Transfer Learning (TL) [22,23,24,25,26] is realized for an architecture (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks - Artificial Neural Networks (CNN-ANN) model) where K distinct clients collaborate to train the first n (e.g., convolution) layers for feature extraction. For inference after training, clients retrain the rest of the (e.g., Fully Connected (FC)) layers of their ML model till convergence on their private data without updating the first n layers (effectively freezing the feature extracting CNN layers).

2.3. Key Generation

2.3.1. Public and Secret Keys

2.3.2. Evaluation Key for Addition

2.3.3. Evaluation Key for Multiplication

2.4. Training Phase

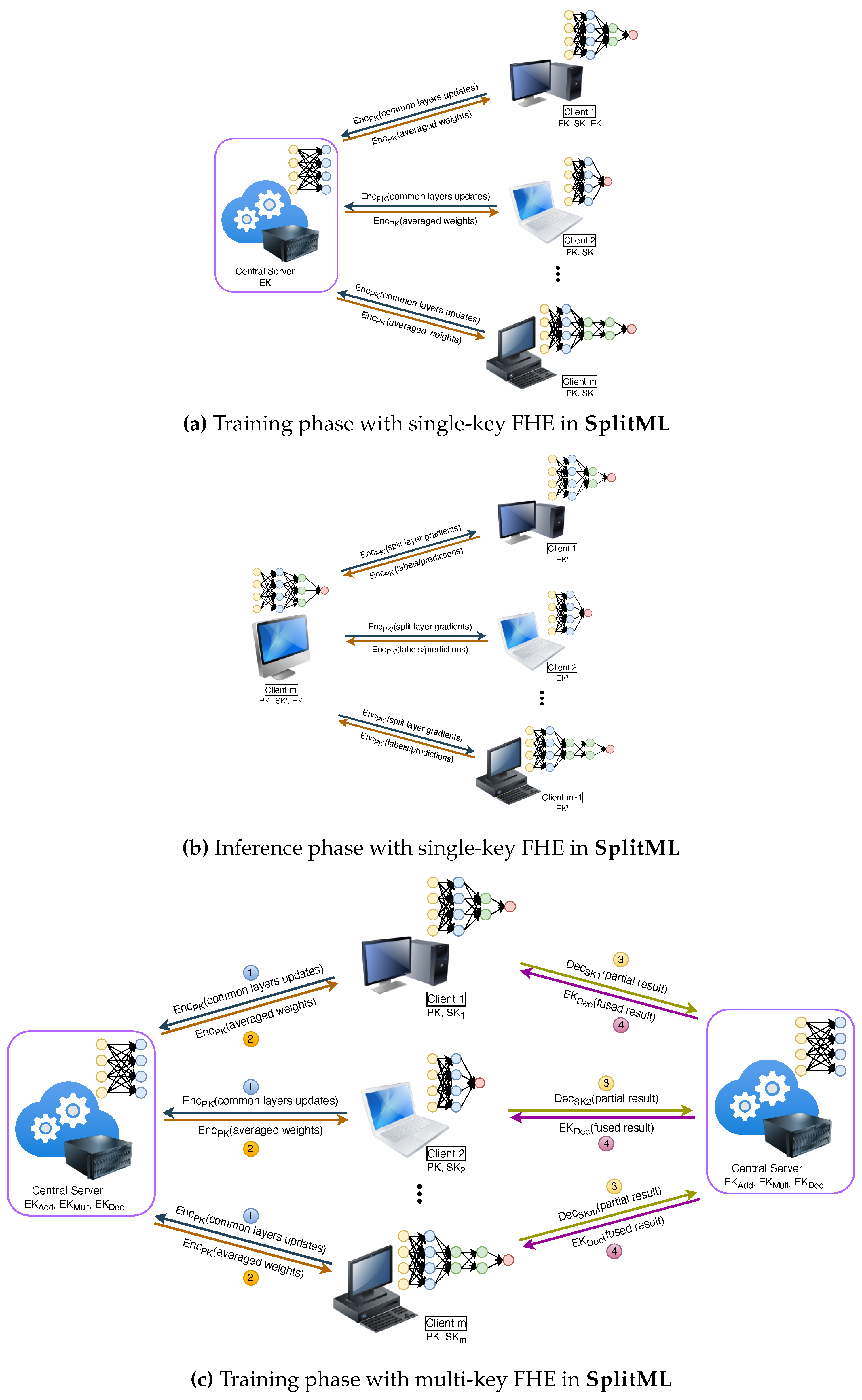

2.4.1. Single-key FHE

2.4.2. Multi-key FHE

2.5. Inference Phase

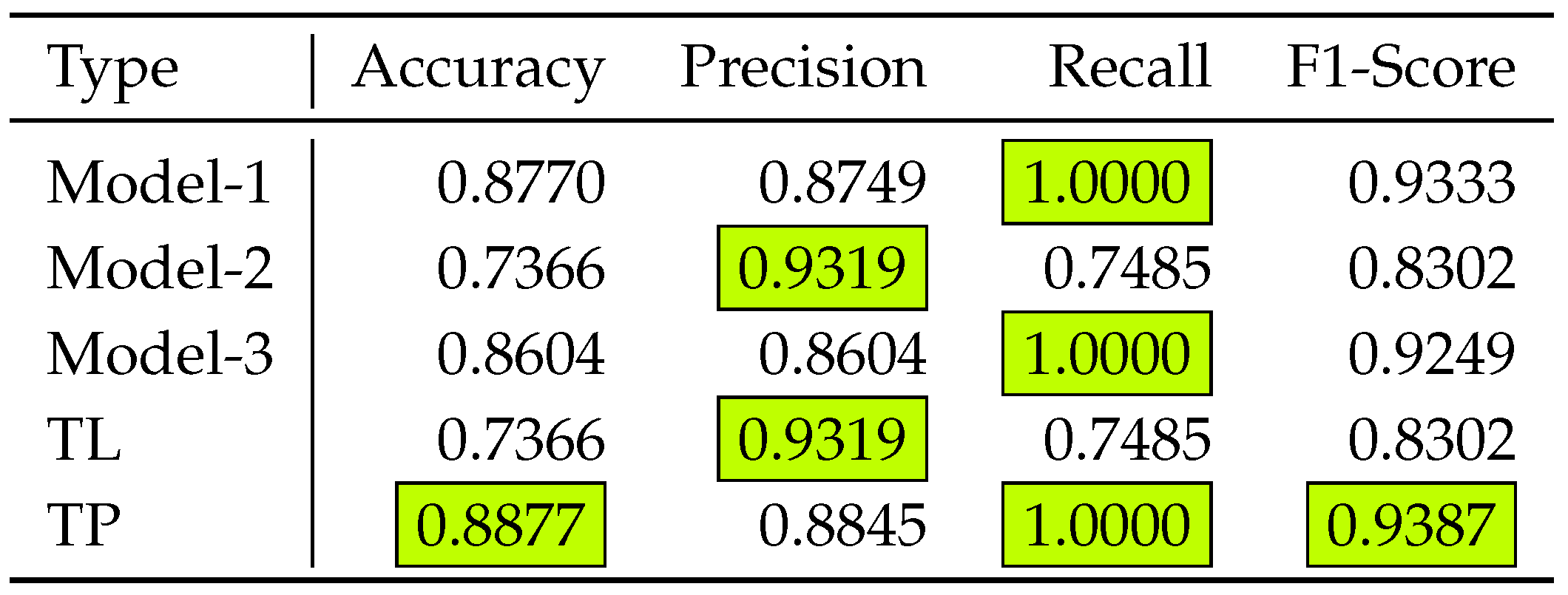

- The (voting) clients send a classification label (TL), and the consensus is done on a label majority.

- The (voting) clients send a result of the final activation function (TP), which is summed up, and the label is chosen if the summation is higher than some required threshold.

2.6. Differential Privacy

3. Security Analysis

3.1. Model Poisoning Attacks

3.2. Inference Attacks

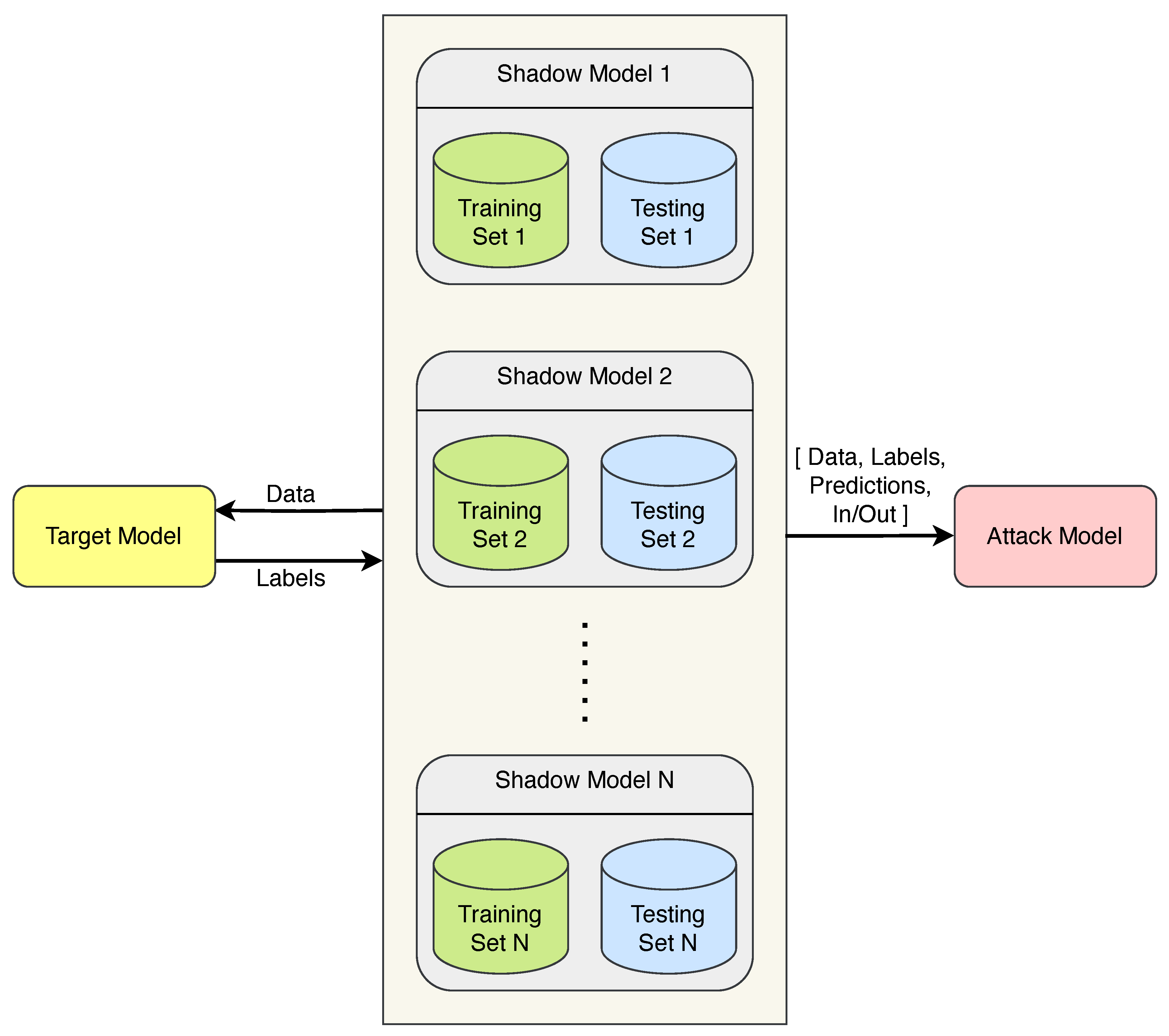

3.2.1. Membership Inference

- First, we attack (input) datasets and their gradients from the split layer to determine their membership.

- We develop another attack model to infer membership from labels or predictions given the gradients from the cut layer.

3.2.2. Model Inversion

3.3. Model Extraction Attacks

4. Experimental Analysis

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Results

5. Conclusion

Appendix A Background

| Symbol | Name |

|---|---|

| Encryption | |

| Decryption | |

| Addition | |

| Multiplication | |

| Public Key | |

| Secret Key | |

| Evaluation Key for Addition | |

| Evaluation Key for Multiplication | |

| Evaluation Key for Fused Decryption | |

| Scaling Factor for FHE | |

| Classification Threshold | |

| Activation Function f on Input z | |

| S | Central (Federation) Server |

| K | (Total) Number of Clients |

| k | Client Index () |

| T | (Threshold) Number of Clients |

| required for Fused Decryption () | |

| Number of Colluding Clients | |

| k-th Client | |

| Dataset of k-th Client | |

| o | Observation (Record) in a Dataset ( |

| A | Shared Attributes (Features) |

| L | Shared Labels |

| n | Number of Shared Layers |

| Number of Personalized Layers | |

| of k-th Client | |

| ML model of k-th Client | |

| Number of Total Layers of k-th Client | |

| () | |

| q | Cut (Split) Layer |

| Size of the Cut Layer | |

| Gradient from Cut Layer q | |

| Number of Decryption Queries | |

| m | Number of Participants in Training |

| p | Training Participant Index () |

| p-th Participant | |

| Number of Participants in Consensus | |

| h | Consensus Participant Index () |

| R | Number of Training Rounds |

| r | Round Index () |

| Fraction of ML parameters with a Client | |

| Fraction of ML parameters with the Server | |

| Batch Size | |

| Learning Rate |

Appendix A.1. Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE)

- : generates a key pair.

- : encrypts a plaintext.

- : decrypts a ciphertext.

- : evaluates an arithmetic operation on ciphertexts (encrypted data).

Appendix A.2. Differential Privacy (DP)

Appendix B Related Work

Appendix B.1. Federated Learning

- Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL), where organizations share partial features.

- Vertical Federated Learning (VFL), where organizations share partial samples.

- Federated Transfer Learning (FTL), where neither samples nor features have much in common.

Appendix B.2. Split Learning

Appendix B.3. Integrating FL with SL

Appendix C Defenses

Appendix C.1. Model Poisoning

Appendix C.2. Membership Inference

Appendix C.3. Model Inversion

Appendix C.4. Model Extraction

References

- de Montjoye, Y.A.; Radaelli, L.; Singh, V.K.; Pentland, A.S. Unique in the shopping mall: On the reidentifiability of credit card metadata. Science 2015, 347, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Qi, J.; He, J. A Survey on Class Imbalance in Federated Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.11673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR, 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, O.; Raskar, R. Distributed learning of deep neural network over multiple agents. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2018, 116, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, J. A comprehensive survey of privacy-preserving federated learning: A taxonomy, review, and future directions. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.; Shokri, R.; Houmansadr, A. Comprehensive privacy analysis of deep learning: Passive and active white-box inference attacks against centralized and federated learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP), 2019; IEEE; pp. 739–753. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Q.; Tao, Z.; Hao, Z.; Li, Q. FABA: an algorithm for fast aggregation against byzantine attacks in distributed neural networks. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, C. Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the forty-first annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, 2009; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, D. Privacy-Preserving Security Analytics; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, D. The Future of Cryptography: Performing Computations on Encrypted Data. ISACA Journal 2023, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, S.; Chen, H.; Laine, K.; Setty, S. PIR with compressed queries and amortized query processing. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP), 2018; IEEE; pp. 962–979. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, J.W.; Castryck, W.; Iliashenko, I.; Vercauteren, F. Privacy-friendly forecasting for the smart grid using homomorphic encryption and the group method of data handling. In Proceedings of the Progress in Cryptology-AFRICACRYPT 2017: 9th International Conference on Cryptology in Africa, Dakar, Senegal, May 24-26, 2017; Springer; pp. 184–201. [Google Scholar]

- Boudguiga, A.; Stan, O.; Sedjelmaci, H.; Carpov, S. Homomorphic Encryption at Work for Private Analysis of Security Logs. In Proceedings of the ICISSP, 2020; pp. 515–523. [Google Scholar]

- Bourse, F.; Minelli, M.; Minihold, M.; Paillier, P. Fast homomorphic evaluation of deep discretized neural networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2018: 38th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 19–23, 2018; Proceedings, Part III 38. Springer; pp. 483–512. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Lauter, K. Private genome analysis through homomorphic encryption. Proceedings of the BMC medical informatics and decision making. BioMed Central 2015, Vol. 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trama, D.; Clet, P.E.; Boudguiga, A.; Sirdey, R. Building Blocks for LSTM Homomorphic Evaluation with TFHE. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Cyber Security, Cryptology, and Machine Learning, 2023; Springer; pp. 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, D.; Boudguiga, A.; Triandopoulos, N. SigML: Supervised Log Anomaly with Fully Homomorphic Encryption. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Cyber Security, Cryptology, and Machine Learning, 2023; Springer; pp. 372–388. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, J.H.; Kim, A.; Kim, M.; Song, Y. Homomorphic Encryption for Arithmetic of Approximate Numbers. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2016/421. 2016. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/421.

- Badawi, A.A.; Alexandru, A.; Bates, J.; Bergamaschi, F.; Cousins, D.B.; Erabelli, S.; Genise, N.; Halevi, S.; Hunt, H.; Kim, A.; et al. OpenFHE: Open-Source Fully Homomorphic Encryption Library. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2022/915. 2022. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/915.

- Al Badawi, A.; Bates, J.; Bergamaschi, F.; Cousins, D.B.; Erabelli, S.; Genise, N.; Halevi, S.; Hunt, H.; Kim, A.; Lee, Y.; et al. OpenFHE: Open-Source Fully Homomorphic Encryption Library. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th Workshop on Encrypted Computing & Applied Homomorphic Cryptography, New York, NY, USA, 2022; WAHC’22, pp. 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonawitz, K.; Ivanov, V.; Kreuter, B.; Marcedone, A.; McMahan, H.B.; Patel, S.; Ramage, D.; Segal, A.; Seth, K. Practical Secure Aggregation for Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, New York, NY, USA, 2017; CCS ’17, pp. 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on knowledge and data engineering 2009, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Sun, F.; Kong, T.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, C. A survey on deep transfer learning. In Proceedings of the Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning–ICANN 2018: 27th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Rhodes, Greece, October 4-7, 2018, Proceedings, Part III 27, 2018; Springer; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, M.B. CHILD: A first step towards continual learning. Machine Learning 1997, 28, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ling, C.; Chai, X.; Pan, R. Test-cost sensitive classification on data with missing values. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2006, 18, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wu, X. Class noise handling for effective cost-sensitive learning by cost-guided iterative classification filtering. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2006, 18, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, C.; Arachchige, P.C.M.; Camtepe, S.; Sun, L. Splitfed: When federated learning meets split learning. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2022, Vol. 36, 8485–8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Security Notes for Homomorphic Encryption — OpenFHE documentation. 2022. Available online: https://openfhe-development.readthedocs.io/en/latest/sphinx_rsts/intro/security.html.

- Tramèr, F.; Zhang, F.; Juels, A.; Reiter, M.K.; Ristenpart, T. Stealing Machine Learning Models via Prediction APIs. Proceedings of the USENIX security symposium 2016, Vol. 16, 601–618. [Google Scholar]

- Juuti, M.; Szyller, S.; Marchal, S.; Asokan, N. PRADA: protecting against DNN model stealing attacks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), 2019; IEEE; pp. 512–527. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Micciancio, D. On the security of homomorphic encryption on approximate numbers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2021: 40th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Zagreb, Croatia, October 17–21, 2021, Proceedings, Part I 40, 2021; Springer; pp. 648–677. [Google Scholar]

- openfhe-development/src/pke/examples/CKKS_ NOISE_FLOODING.md at main · openfheorg/openfhe-development. 2022. Available online: https://github.com/openfheorg/openfhe-development/blob/main/src/pke/examples/.

- Ogilvie, T. Differential Privacy for Free? Harnessing the Noise in Approximate Homomorphic Encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive 2023. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Zhu, J.; He, P.; Lyu, M.R. Loghub: A Large Collection of System Log Datasets towards Automated Log Analytics. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, R.; Stronati, M.; Song, C.; Shmatikov, V. Membership inference attacks against machine learning models. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP). IEEE, 2017; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolae, M.I.; Sinn, M.; Tran, M.N.; Buesser, B.; Rawat, A.; Wistuba, M.; Zantedeschi, V.; Baracaldo, N.; Chen, B.; Ludwig, H.; et al. Adversarial Robustness Toolbox v1.2.0. CoRR 2018, 1807.01069. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Cortes, C. MNIST handwritten digit database. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrikson, M.; Jha, S.; Ristenpart, T. Model inversion attacks that exploit confidence information and basic countermeasures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 2015; pp. 1322–1333. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6572. [Google Scholar]

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.06083. [Google Scholar]

- Rakin, A.S.; He, Z.; Fan, D. Bit-flip attack: Crushing neural network with progressive bit search. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2019; pp. 1211–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Rakin, A.S.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; He, Z.; Fan, D.; Chakrabarti, C. Model Extraction Attacks on Split Federated Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagielski, M.; Carlini, N.; Berthelot, D.; Kurakin, A.; Papernot, N. High accuracy and high fidelity extraction of neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Conference on Security Symposium, 2020; pp. 1345–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Jagielski, M.; Carlini, N.; Berthelot, D.; Kurakin, A.; Papernot, N. High-fidelity extraction of neural network models. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.01838. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Lyu, M.R. Drain: An online log parsing approach with fixed depth tree. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE international conference on web services (ICWS), 2017; IEEE; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation, P.S. Python 3.11. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buitinck, L.; Louppe, G.; Blondel, M.; Pedregosa, F.; Mueller, A.; Grisel, O.; Niculae, V.; Prettenhofer, P.; Gramfort, A.; Grobler, J.; et al. API design for machine learning software: experiences from the scikit-learn project. In Proceedings of the ECML PKDD Workshop: Languages for Data Mining and Machine Learning, 2013; pp. 108–122. [Google Scholar]

- Brakerski, Z.; Gentry, C.; Vaikuntanathan, V. (Leveled) fully homomorphic encryption without bootstrapping. ACM Transactions on Computation Theory (TOCT) 2014, 6, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.H.; Kim, A.; Kim, M.; Song, Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2017: 23rd International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptology and Information Security, Hong Kong, China, December 3-7, 2017, Proceedings, Part I 23, 2017; Springer; pp. 409–437. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Vercauteren, F. Somewhat practical fully homomorphic encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, C.; Sahai, A.; Waters, B. Homomorphic encryption from learning with errors: Conceptually-simpler, asymptotically-faster, attribute-based. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2013: 33rd Annual Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 18-22, 2013; Proceedings, Part I. Springer; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chillotti, I.; Gama, N.; Georgieva, M.; Izabachene, M. Faster fully homomorphic encryption: Bootstrapping in less than 0.1 seconds. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2016: 22nd International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Hanoi, Vietnam, 4-8 December 2016; Proceedings, Part I 22. Springer; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ducas, L.; Micciancio, D. FHEW: bootstrapping homomorphic encryption in less than a second. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2015: 34th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Sofia, Bulgaria, April 26-30, 2015, Proceedings, Part I 34, 2015; Springer; pp. 617–640. [Google Scholar]

- Brakerski, Z. Fully Homomorphic Encryption Without Modulus Switching from Classical GapSVP. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32Nd Annual Cryptology Conference on Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO 2012 -, New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 7417, pp. 868–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Vercauteren, F. Somewhat Practical Fully Homomorphic Encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2012/144. 2012. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2012/144.

- Brakerski, Z.; Gentry, C.; Vaikuntanathan, V. Fully Homomorphic Encryption without Bootstrapping. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2011/277. 2011. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2011/277.

- Chillotti, I.; Gama, N.; Georgieva, M.; Izabachène, M. Faster Fully Homomorphic Encryption: Bootstrapping in Less Than 0.1 Seconds. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology – ASIACRYPT 2016; Berlin, Heidelberg, Cheon, J.H., Takagi, T., Eds.; 2016; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dwork, C. Differential privacy. In Proceedings of the International colloquium on automata, languages, and programming; Springer, 2006; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dwork, C.; Roth, A.; et al. The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy. Foundations and Trends® in Theoretical Computer Science 2014, 9, 211–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Qardaji, W.; Su, D.; Wu, Y.; Yang, W. Membership privacy: A unifying framework for privacy definitions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC conference on Computer & communications security, 2013; pp. 889–900. [Google Scholar]

- Vinterbo, S.A. Differentially private projected histograms: Construction and use for prediction. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, 2012; Springer; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, K.; Monteleoni, C. Privacy-preserving logistic regression. Advances in neural information processing systems 2008, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, X.; Yang, Y.; Winslett, M. Functional mechanism: Regression analysis under differential privacy. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1208.0219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, B.I.; Bartlett, P.L.; Huang, L.; Taft, N. Learning in a large function space: Privacy-preserving mechanisms for SVM learning. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0911.5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, G.; Pillaipakkamnatt, K.; Wright, R.N. A practical differentially private random decision tree classifier. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops. IEEE, 2009; pp. 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Shokri, R.; Shmatikov, V. Privacy-preserving deep learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 2015; pp. 1310–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Pustozerova, A.; Mayer, R. Information leaks in federated learning. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium 2020, Vol. 10, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, Z.; Han, S. Deep leakage from gradients. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, H.B.; Ramage, D.; Talwar, K.; Zhang, L. Learning differentially private language models without losing accuracy. CoRR abs/1710.06963 (2017). arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M.; Chu, A.; Goodfellow, I.; McMahan, H.B.; Mironov, I.; Talwar, K.; Zhang, L. Deep learning with differential privacy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 2016; pp. 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- Papernot, N.; Song, S.; Mironov, I.; Raghunathan, A.; Talwar, K.; Erlingsson, Ú. Scalable private learning with pate. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.08908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater, C.; Bellet, A.; Ramon, J. Distributed differentially private averaging with improved utility and robustness to malicious parties. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grivet Sébert, A.; Pinot, R.; Zuber, M.; Gouy-Pailler, C.; Sirdey, R. SPEED: secure, PrivatE, and efficient deep learning. Machine Learning 2021, 110, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yin, H.; Alvarez, J.M.; Kautz, J.; Molchanov, P.; Kung, H. Privacy Vulnerability of Split Computing to Data-Free Model Inversion Attacks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.06304. [Google Scholar]

- Titcombe, T.; Hall, A.J.; Papadopoulos, P.; Romanini, D. Practical defences against model inversion attacks for split neural networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.05743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truex, S.; Liu, L.; Gursoy, M.E.; Yu, L.; Wei, W. Demystifying membership inference attacks in machine learning as a service. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2019, 14, 2073–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Song, M.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qi, H. Beyond inferring class representatives: User-level privacy leakage from federated learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2019-IEEE conference on computer communications. IEEE, 2019; pp. 2512–2520. [Google Scholar]

- Bagdasaryan, E.; Veit, A.; Hua, Y.; Estrin, D.; Shmatikov, V. How to backdoor federated learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. PMLR, 2020; pp. 2938–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, B.; Gao, J.; Guo, X.; Baker, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Liu, Z. Mitigating the backdoor attack by federated filters for industrial IoT applications. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2021, 18, 3562–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Cao, X.; Jia, J.; Gong, N.Z. Local model poisoning attacks to byzantine-robust federated learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Conference on Security Symposium, 2020; pp. 1623–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, E.; Ding, J.; Tarokh, V. Heterofl: Computation and communication efficient federated learning for heterogeneous clients. arXiv arXiv:2010.01264. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yu, F.; Xiong, J.; Chen, X. Helios: Heterogeneity-aware federated learning with dynamically balanced collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2021 58th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), 2021; IEEE; pp. 997–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Vepakomma, P.; Gupta, O.; Swedish, T.; Raskar, R. Split learning for health: Distributed deep learning without sharing raw patient data. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.00564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jia, R.; Qi, G.J. Improved techniques for model inversion attacks. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, R.; Pei, H.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Song, D. The secret revealer: Generative model-inversion attacks against deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, X.; Ding, J.; Nguyen, H.; Yu, R.; Pan, M.; Wong, S.T. Evaluation of inference attack models for deep learning on medical data. arXiv arXiv:2011.00177. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, T.; Lee, R.B. Model inversion attacks against collaborative inference. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 35th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, 2019; pp. 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Douceur, J.R. The sybil attack. In Proceedings of the Peer-to-Peer Systems: First International Workshop, IPTPS 2002, Cambridge, MA, USA, 7–8 March 2002; Springer; pp. 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; Bellet, A.; Bennis, M.; Bhagoji, A.N.; Bonawitz, K.; Charles, Z.; Cormode, G.; Cummings, R.; et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning 2021, 14, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, D.; Ateniese, G.; Bernaschi, M. Unleashing the tiger: Inference attacks on split learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2021; pp. 2113–2129. [Google Scholar]

- Hitaj, B.; Ateniese, G.; Perez-Cruz, F. Deep models under the GAN: information leakage from collaborative deep learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 2017; pp. 603–618. [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğan, E.; Küpçü, A.; Çiçek, A.E. Unsplit: Data-oblivious model inversion, model stealing, and label inference attacks against split learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21st Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society, 2022; pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Abedi, A.; Khan, S.S. Fedsl: Federated split learning on distributed sequential data in recurrent neural networks. arXiv arXiv:2011.03180. [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Chen, Y.; Kannan, R.; Bartlett, P. Byzantine-robust distributed learning: Towards optimal statistical rates. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2018; pp. 5650–5659. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, P.; El Mhamdi, E.M.; Guerraoui, R.; Stainer, J. Machine learning with adversaries: Byzantine tolerant gradient descent. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Guerraoui, R.; Rouault, S.; et al. The hidden vulnerability of distributed learning in byzantium. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2018; pp. 3521–3530. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Tople, S.; Saxena, P. Auror: Defending against poisoning attacks in collaborative deep learning systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Conference on Computer Security Applications, 2016; pp. 508–519. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, C.; Yoon, C.J.; Beschastnikh, I. The Limitations of Federated Learning in Sybil Settings. In Proceedings of the RAID, 2020; pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Lai, L.; Suda, N.; Civin, D.; Chandra, V. Federated learning with non-iid data. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.00582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kaplan, Z.; Niu, D.; Li, B. Optimizing federated learning on non-iid data with reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2020-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications. IEEE, 2020; pp. 1698–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Fang, M.; Liu, J.; Gong, N.Z. Fltrust: Byzantine-robust federated learning via trust bootstrapping. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.13995. [Google Scholar]

- Melis, L.; Song, C.; De Cristofaro, E.; Shmatikov, V. Exploiting unintended feature leakage in collaborative learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP), 2019; IEEE; pp. 691–706. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, M. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): European regulation that has a global impact. International Journal of Market Research 2017, 59, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, H.; Xu, G.; Chen, Z.; Huang, X.; Lu, R. Privacy-enhanced federated learning against poisoning adversaries. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2021, 16, 4574–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Ma, J.; Miao, Y.; Li, Y.; Deng, R.H. ShieldFL: Mitigating model poisoning attacks in privacy-preserving federated learning. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2022, 17, 1639–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Li, J.; Ding, M.; Ma, C.; Yang, H.H.; Farokhi, F.; Jin, S.; Quek, T.Q.; Poor, H.V. Federated learning with differential privacy: Algorithms and performance analysis. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2020, 15, 3454–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.C.; Klein, T.; Nabi, M. Differentially private federated learning: A client level perspective. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.07557. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, M.; Li, H.; Luo, X.; Xu, G.; Yang, H.; Liu, S. Efficient and privacy-enhanced federated learning for industrial artificial intelligence. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2019, 16, 6532–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phong, L.T.; Aono, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Wang, L.; Moriai, S. Privacy-Preserving Deep Learning via Additively Homomorphic Encryption. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2018, 13, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuadbba, S.; Kim, K.; Kim, M.; Thapa, C.; Camtepe, S.A.; Gao, Y.; Kim, H.; Nepal, S. Can we use split learning on 1d cnn models for privacy preserving training? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2020; pp. 305–318. [Google Scholar]

- Dwork, C. Differential privacy: A survey of results. In Proceedings of the Theory and Applications of Models of Computation: 5th International Conference, TAMC 2008, Xi’an, China, April 25-29, 2008; Proceedings 5. Springer; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mireshghallah, F.; Taram, M.; Ramrakhyani, P.; Jalali, A.; Tullsen, D.; Esmaeilzadeh, H. Shredder: Learning noise distributions to protect inference privacy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, 2020; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vepakomma, P.; Gupta, O.; Dubey, A.; Raskar, R. Reducing leakage in distributed deep learning for sensitive health data. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1812.005642. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Rakin, A.S.; Chen, X.; He, Z.; Fan, D.; Chakrabarti, C. Ressfl: A resistance transfer framework for defending model inversion attack in split federated learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022; pp. 10194–10202. [Google Scholar]

- Vepakomma, P.; Singh, A.; Gupta, O.; Raskar, R. NoPeek: Information leakage reduction to share activations in distributed deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), 2020; IEEE; pp. 933–942. [Google Scholar]

- Papernot, N.; Abadi, M.; Erlingsson, U.; Goodfellow, I.; Talwar, K. Semi-supervised knowledge transfer for deep learning from private training data. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.05755. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Gu, Z.; Jang, J.; Wu, H.; Stoecklin, M.P.; Huang, H.; Molloy, I. Protecting intellectual property of deep neural networks with watermarking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2018; pp. 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, Y.; Uchida, Y.; Sakazawa, S.; Satoh, S. Digital watermarking for deep neural networks. International Journal of Multimedia Information Retrieval 2018, 7, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagielski, M.; Oprea, A.; Biggio, B.; Liu, C.; Nita-Rotaru, C.; Li, B. Manipulating machine learning: Poisoning attacks and countermeasures for regression learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP), 2018; IEEE; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H.; Choquette-Choo, C.A.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Papernot, N. Entangled Watermarks as a Defense against Model Extraction. In Proceedings of the USENIX Security Symposium, 2021; pp. 1937–1954. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | A curious adversary is a passive entity that observes and learns from a system’s communication without altering it, whereas a malicious adversary is an active entity that can observe, alter, and inject false information into the system. |

| 2 | A semi-honest threat model (also known as “honest-but-curious") assumes that an adversary will faithfully follow a protocol’s instructions but will attempt to learn as much private information as possible from the messages they observe. |

| 3 | Fused decryption in multi-key FHE efficiently combines partial decryption results from multiple parties into a single plaintext. |

| 4 | A ‘cut or split layer’ is the separation boundary between (shared) common layers and the rest of the (local) model. |

| 5 | For simplicity, we denote various OpenFHE API for key generation as a variation of function. |

| 6 | Multi-key FHE requires all participants to be online and share their partial decryptions to evaluate the fused decryption, which may be infeasible for organizations distributed over the internet. Threshold-FHE eases this by requiring T out of K, partial decryptions to calculate fused decryption. |

| 7 | After federated training concludes, a client may observe the output range for false predictions and choose to perform consensus for the samples falling in this range to improve the inference accuracy. For as , we choose for boundaries (label 0) and (label 1) by simulation. Since all the false predictions were from ranges and . |

| 8 | We do not manually inject additional DP noise into the system; instead, we rely on two inherent features of the CKKS scheme for DP guarantees: the default OpenFHE configuration for noise flooding and the intrinsic noise generated during CKKS operations. Alternatively, for FHE schemes like BGV or BFV, achieving DP would typically involve adding extra noise directly to the model updates before they are encrypted. |

| 9 | We denote normal class as label-0 and anomalous with label-1. |

| 10 | We omit the details of textual log data parsing for brevity. |

| Method | Computation | Communication |

|---|---|---|

| FL [3] | ||

| SL [4] | ||

| SFL [27] | ||

| SplitML |

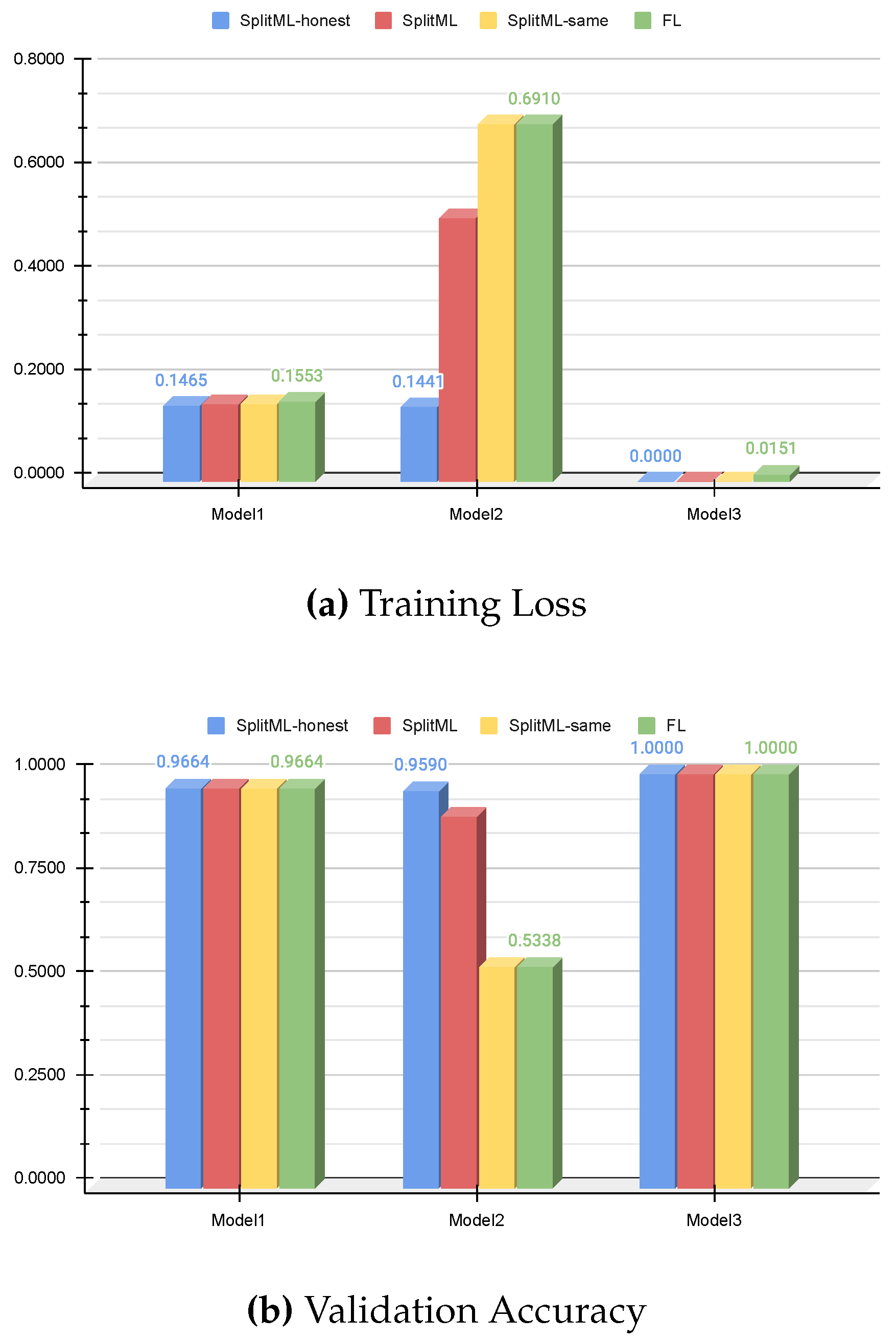

| Type | S1 | S2 | S3 | FL | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| TA | 0.9655 | 0.9583 | 1.0000 | 0.9655 | 0.8404 | 1.0000 | 0.9655 | 0.5345 | 1.0000 | 0.9655 | 0.5345 | 0.9994 |

| TL | 0.1465 | 0.1441 | 0.0000 | 0.1501 | 0.5115 | 0.0000 | 0.1501 | 0.6908 | 0.0000 | 0.1553 | 0.6910 | 0.0151 |

| VA | 0.9664 | 0.9590 | 1.0000 | 0.9664 | 0.8980 | 1.0000 | 0.9664 | 0.5338 | 1.0000 | 0.9664 | 0.5338 | 1.0000 |

| VL | 0.1433 | 0.1438 | 0.0000 | 0.1473 | 0.4348 | 0.0000 | 0.1472 | 0.6910 | 0.0000 | 0.1472 | 0.6909 | 0.0008 |

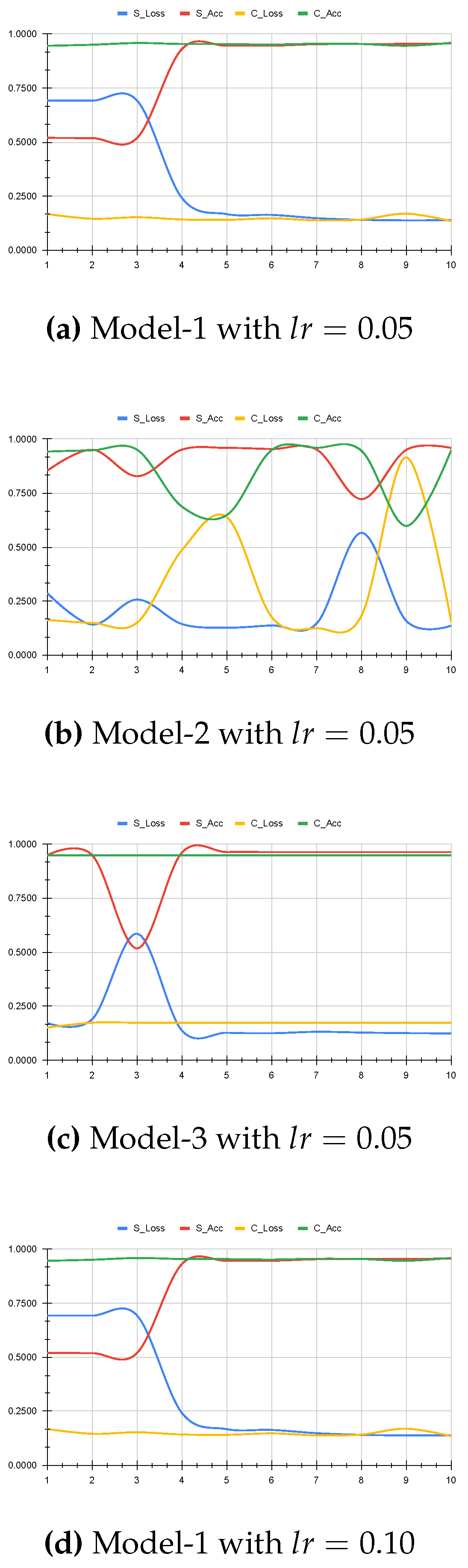

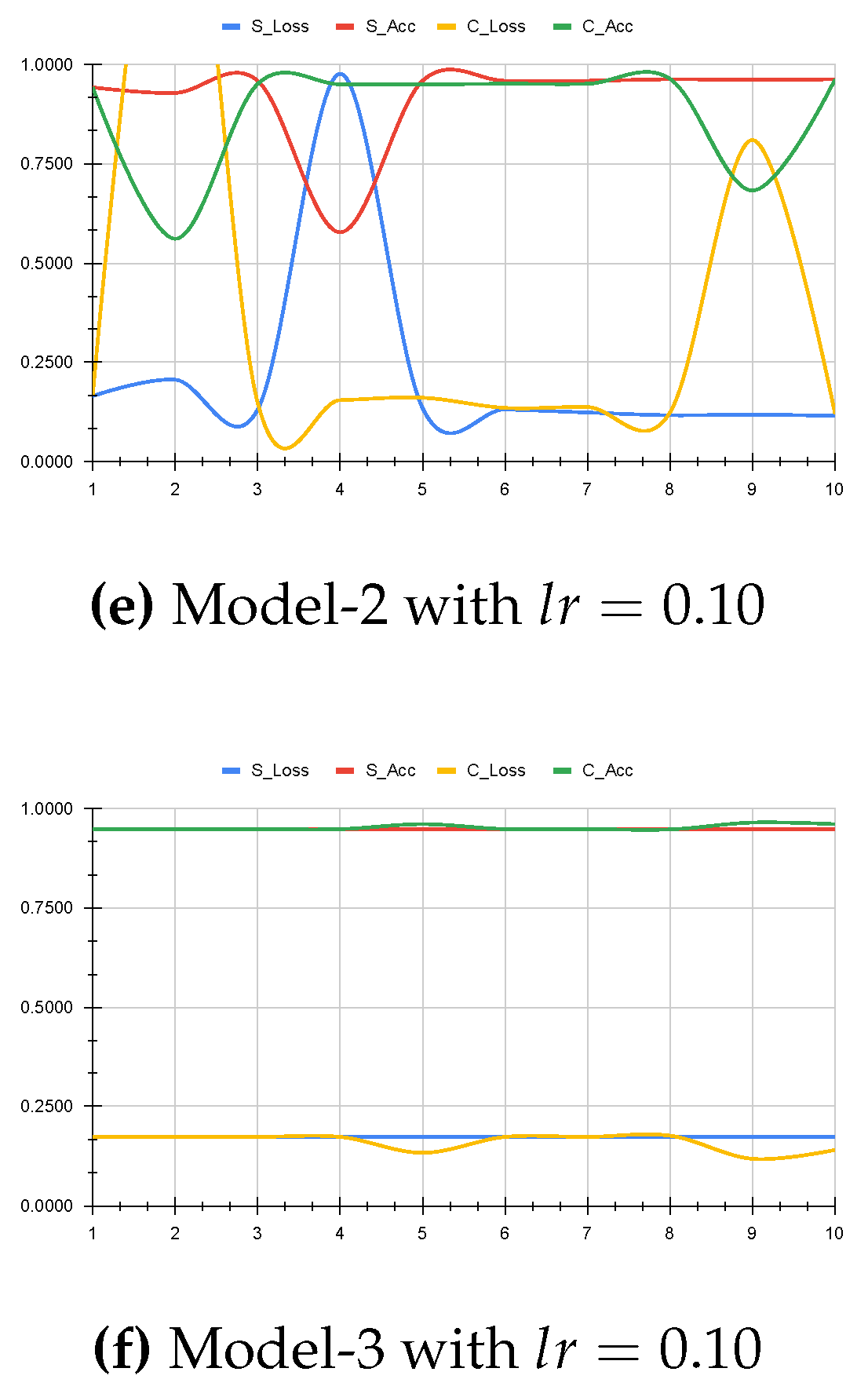

| Arch | Training Loss | Validation Accuracy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

| S1 | 0.1352 | 0.1564 | 0.2390 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9691 | 0.9623 | 0.9163 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| S2 | 0.1378 | 0.1568 | 5241.3701 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9691 | 0.9623 | 0.5658 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| S3 | 0.1378 | 0.1568 | 0.6839 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9691 | 0.9623 | 0.5658 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| FL | 8.48E+15 | 1.03E+16 | 1.19E+17 | 3.20E+17 | 3.43E+17 | 0.9691 | 0.9623 | 0.5658 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

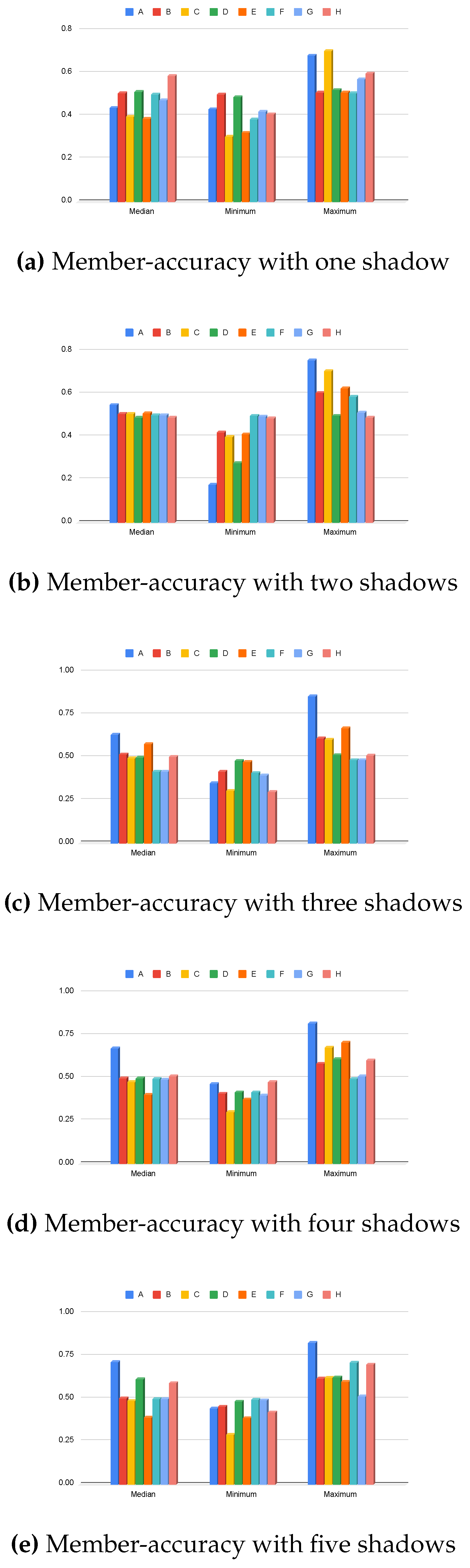

| Shadows | Architecture | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full model | 0.4374 | 0.4302 | 0.6816 | |

| 1 | Top layers | 0.5072 | 0.5006 | 0.5100 |

| Bottom layers | 0.3970 | 0.3046 | 0.7036 | |

| Full model | 0.5464 | 0.1764 | 0.7552 | |

| 2 | Top layers | 0.5064 | 0.4186 | 0.6028 |

| Bottom layers | 0.5072 | 0.3994 | 0.7042 | |

| Full model | 0.6306 | 0.3482 | 0.8566 | |

| 3 | Top layers | 0.5170 | 0.4154 | 0.6088 |

| Bottom layers | 0.4958 | 0.3030 | 0.6030 | |

| Full model | 0.6750 | 0.4644 | 0.8170 | |

| 4 | Top layers | 0.4994 | 0.4080 | 0.5838 |

| Bottom layers | 0.4778 | 0.3004 | 0.6784 | |

| Full model | 0.7130 | 0.4420 | 0.8260 | |

| 5 | Top layers | 0.5015 | 0.4542 | 0.6166 |

| Bottom layers | 0.4881 | 0.2892 | 0.6196 | |

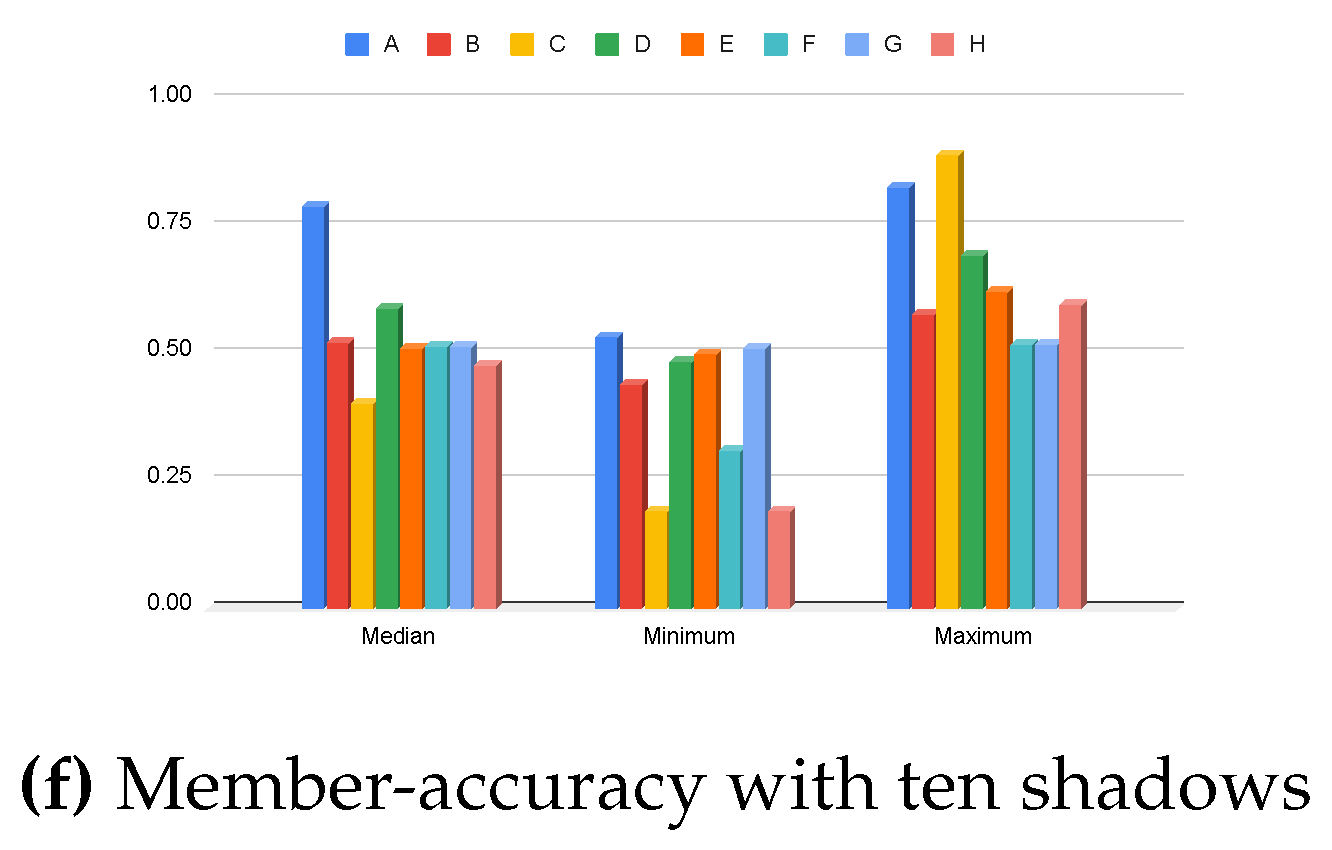

| Full model | 0.7610 | 0.4730 | 0.8984 | |

| 6 | Top layers | 0.5058 | 0.4352 | 0.5674 |

| Bottom layers | 0.3934 | 0.3792 | 0.5972 | |

| Full model | 0.7572 | 0.7324 | 0.8428 | |

| 7 | Top layers | 0.4766 | 0.4566 | 0.5402 |

| Bottom layers | 0.5054 | 0.5016 | 0.5856 | |

| Full model | 0.7546 | 0.5564 | 0.7862 | |

| 8 | Top layers | 0.5242 | 0.3714 | 0.5594 |

| Bottom layers | 0.4052 | 0.3768 | 0.8056 | |

| Full model | 0.8356 | 0.8176 | 0.8530 | |

| 9 | Top layers | 0.4482 | 0.4374 | 0.5168 |

| Bottom layers | 0.5008 | 0.3904 | 0.6004 | |

| Full model | 0.7886 | 0.5324 | 0.8270 | |

| 10 | Top layers | 0.5206 | 0.4376 | 0.5776 |

| Bottom layers | 0.4020 | 0.1910 | 0.8900 |

| Type | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full (100%) | 0.4999 | 0.4999 | 1.0000 | 0.6666 |

| Test (20%) | 0.5016 | 0.5016 | 1.0000 | 0.6681 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).