Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Compositions

2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.5. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

2.6. Pyrolysis of PLA, PLA/Na-MMT and PLA/GnP Compositions

2.7. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS)

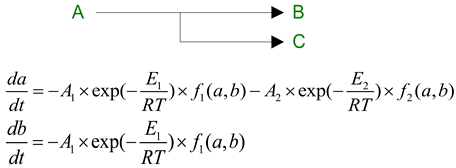

2.8. Model Thermokinetics

3. Results

3.1. AFM Characterization

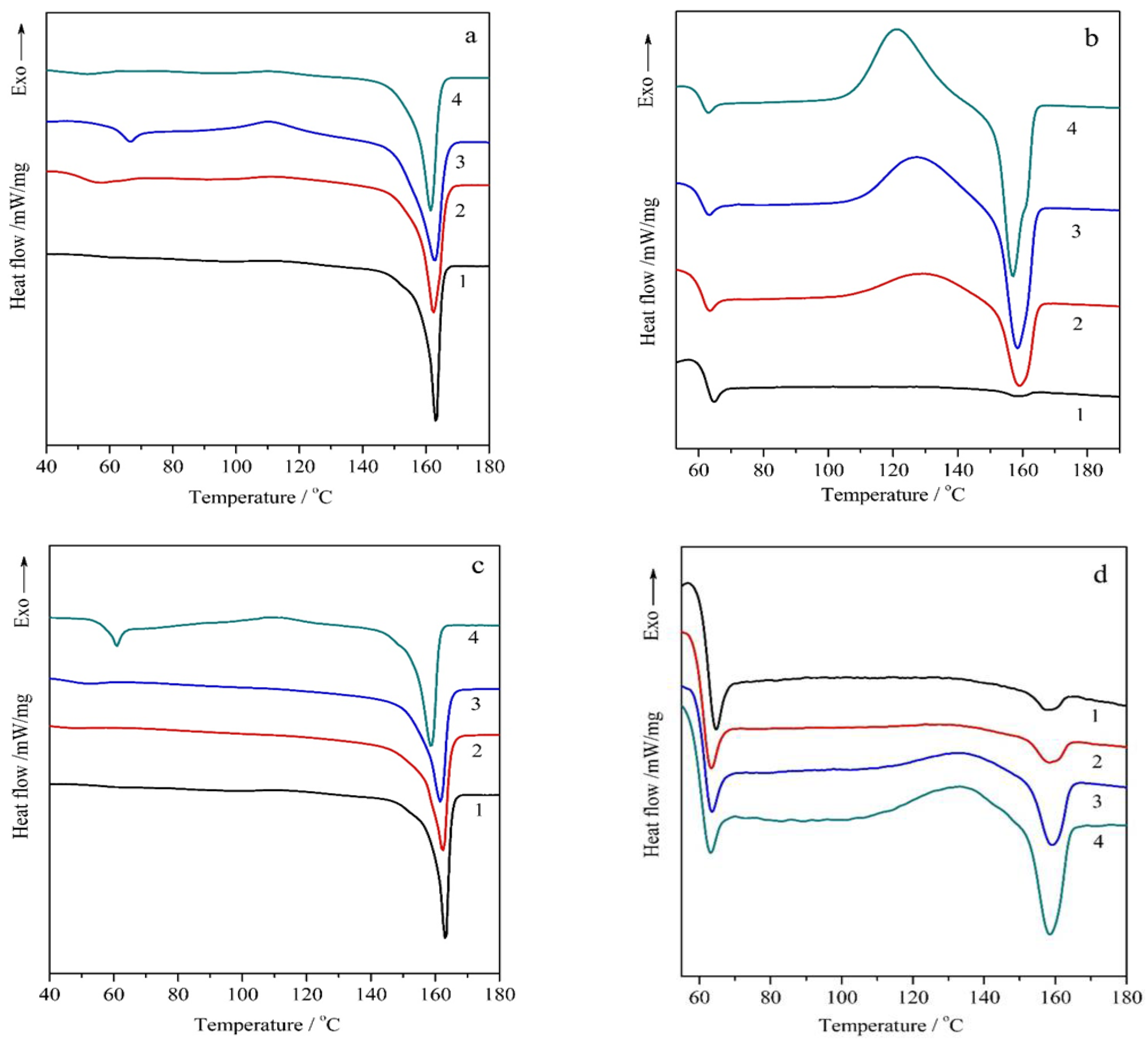

3.2. DSC Analysis of PLA/CR PLA/Na-MMT and PLA/GnP Compositions

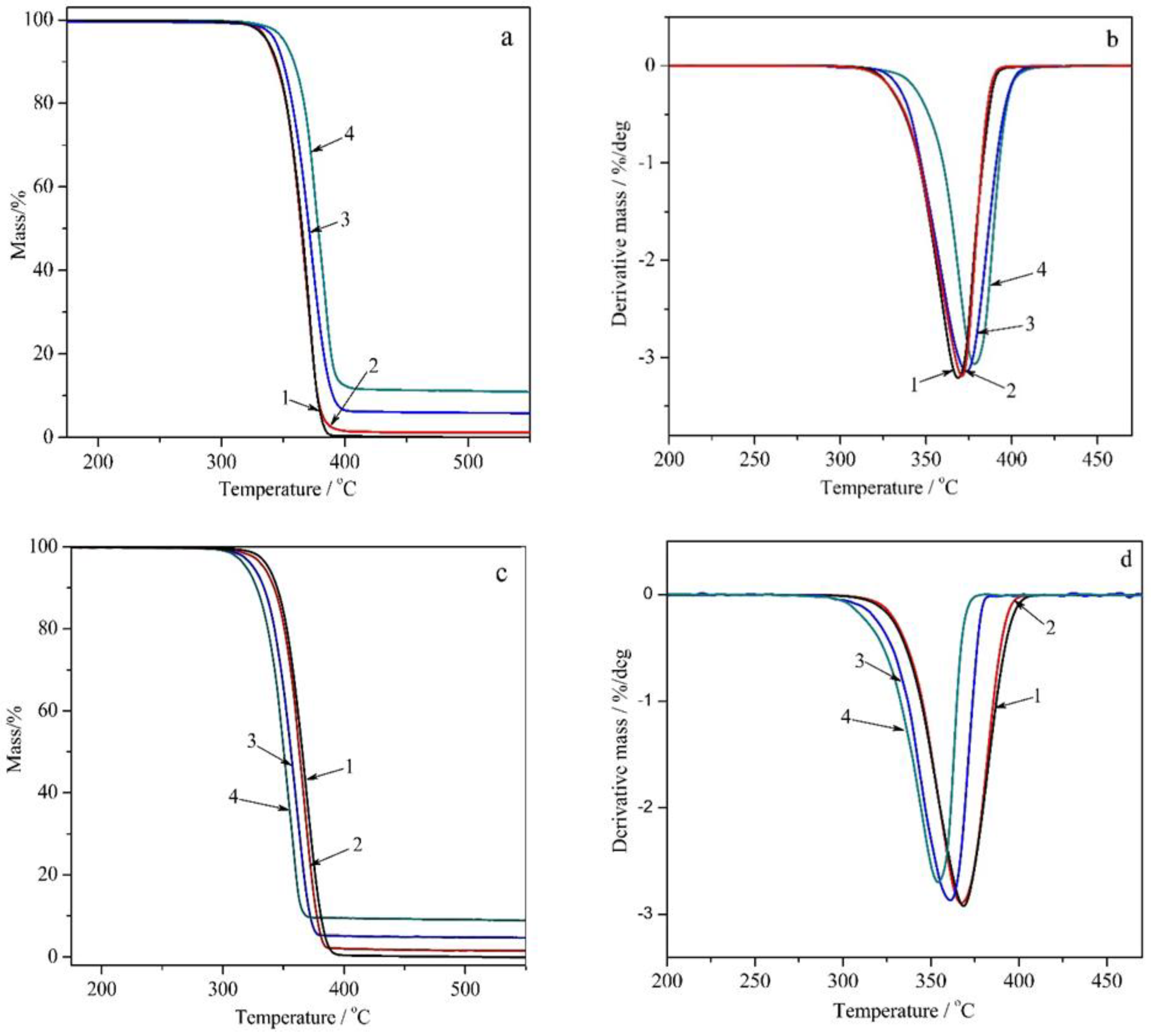

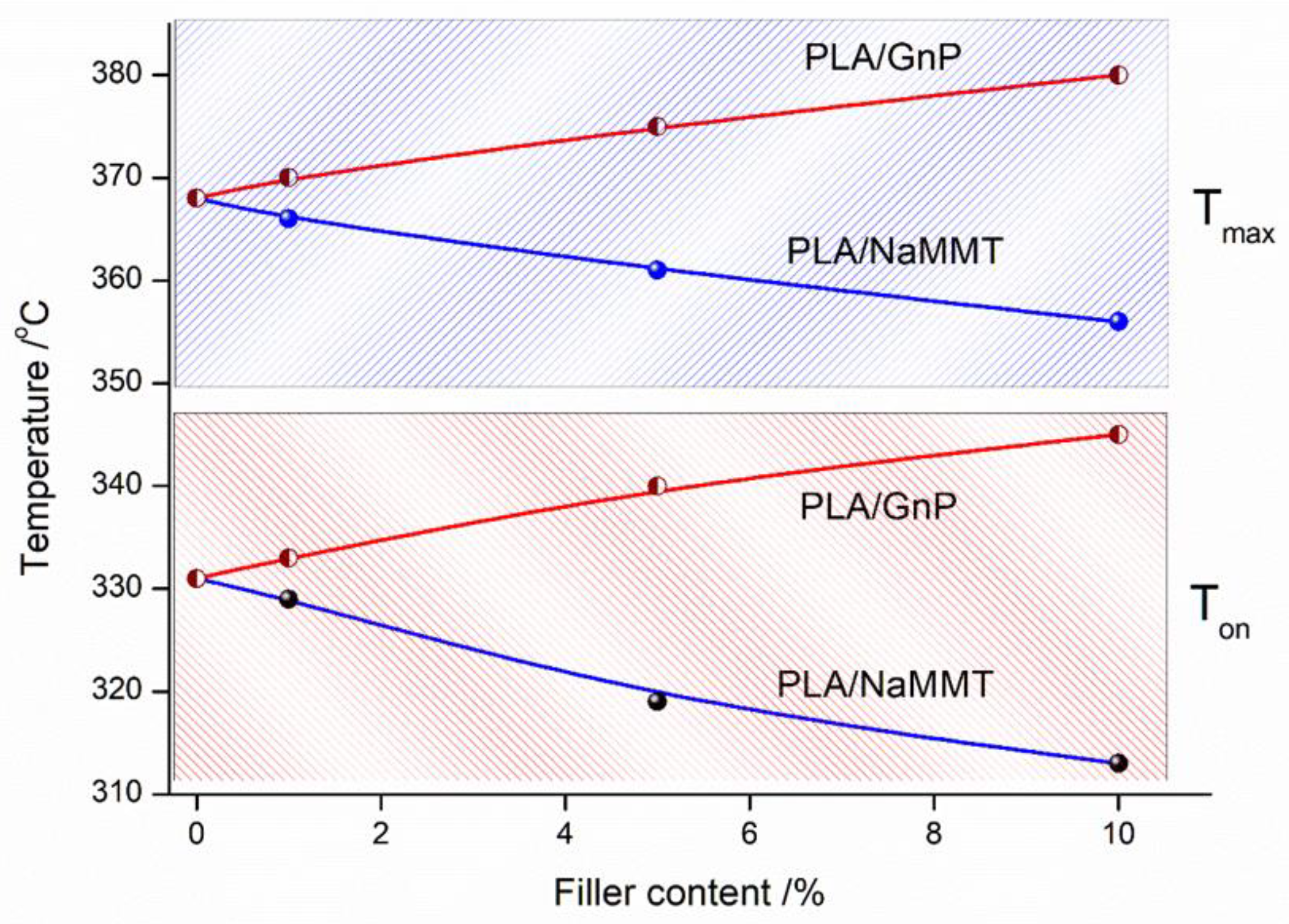

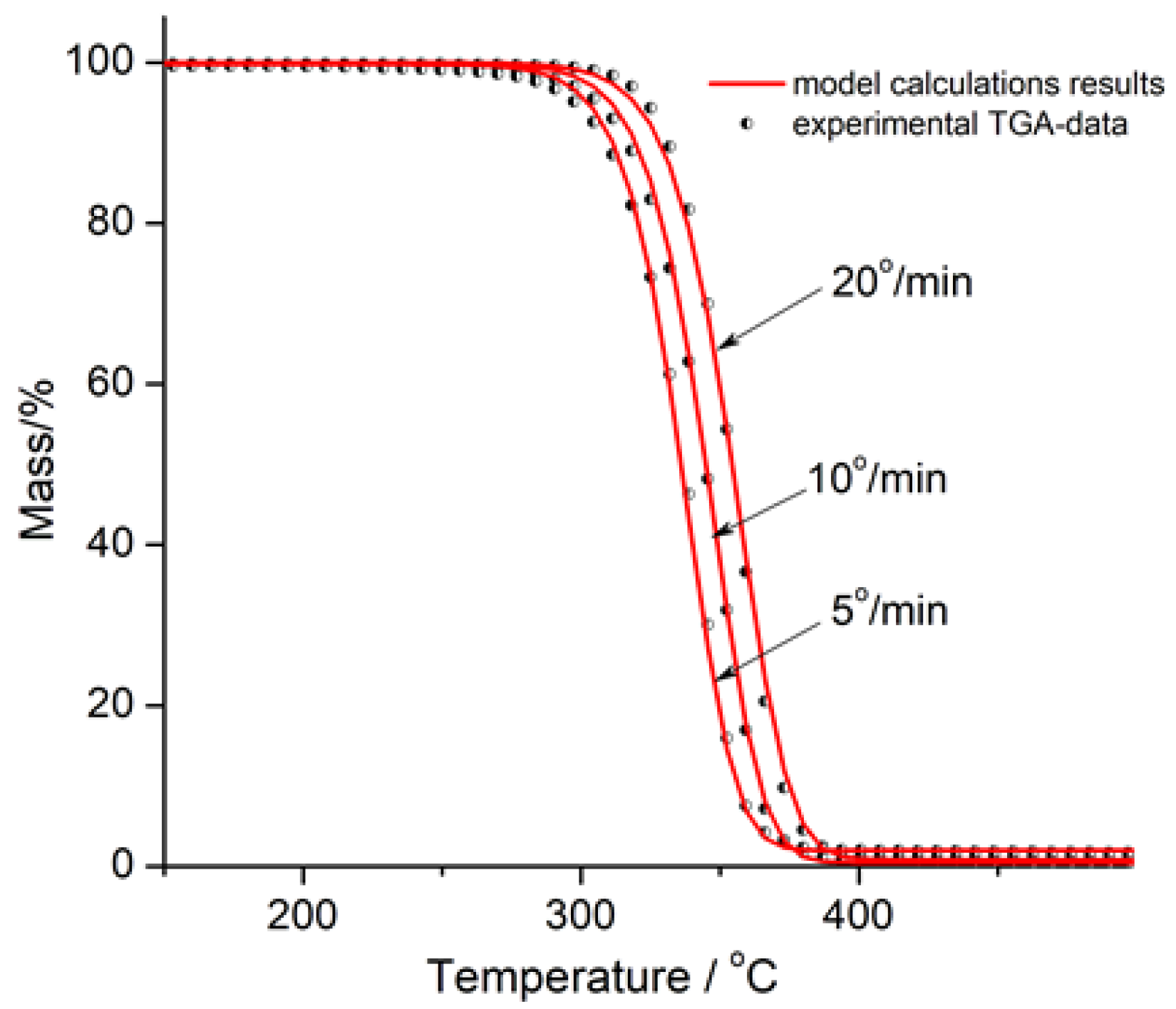

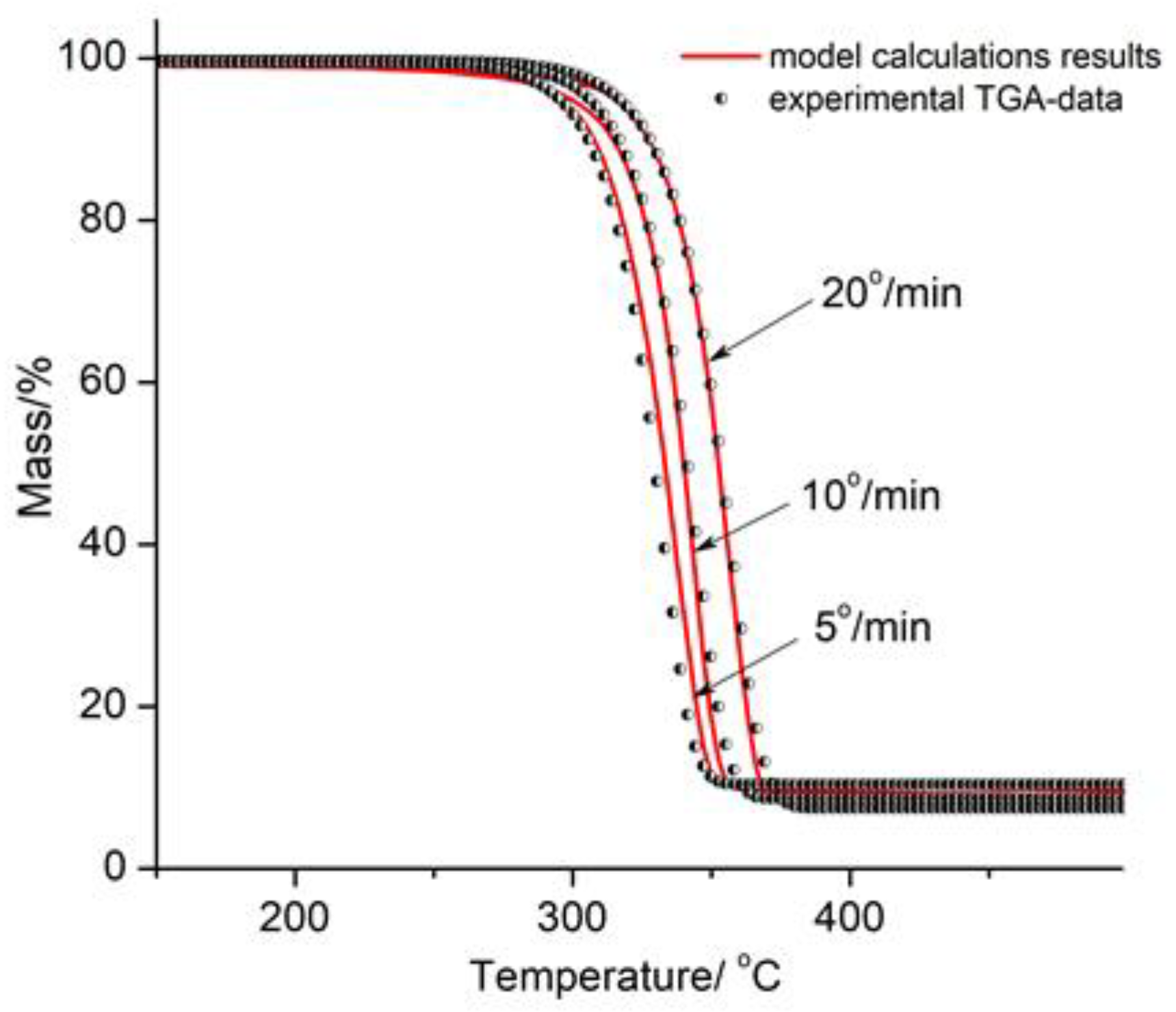

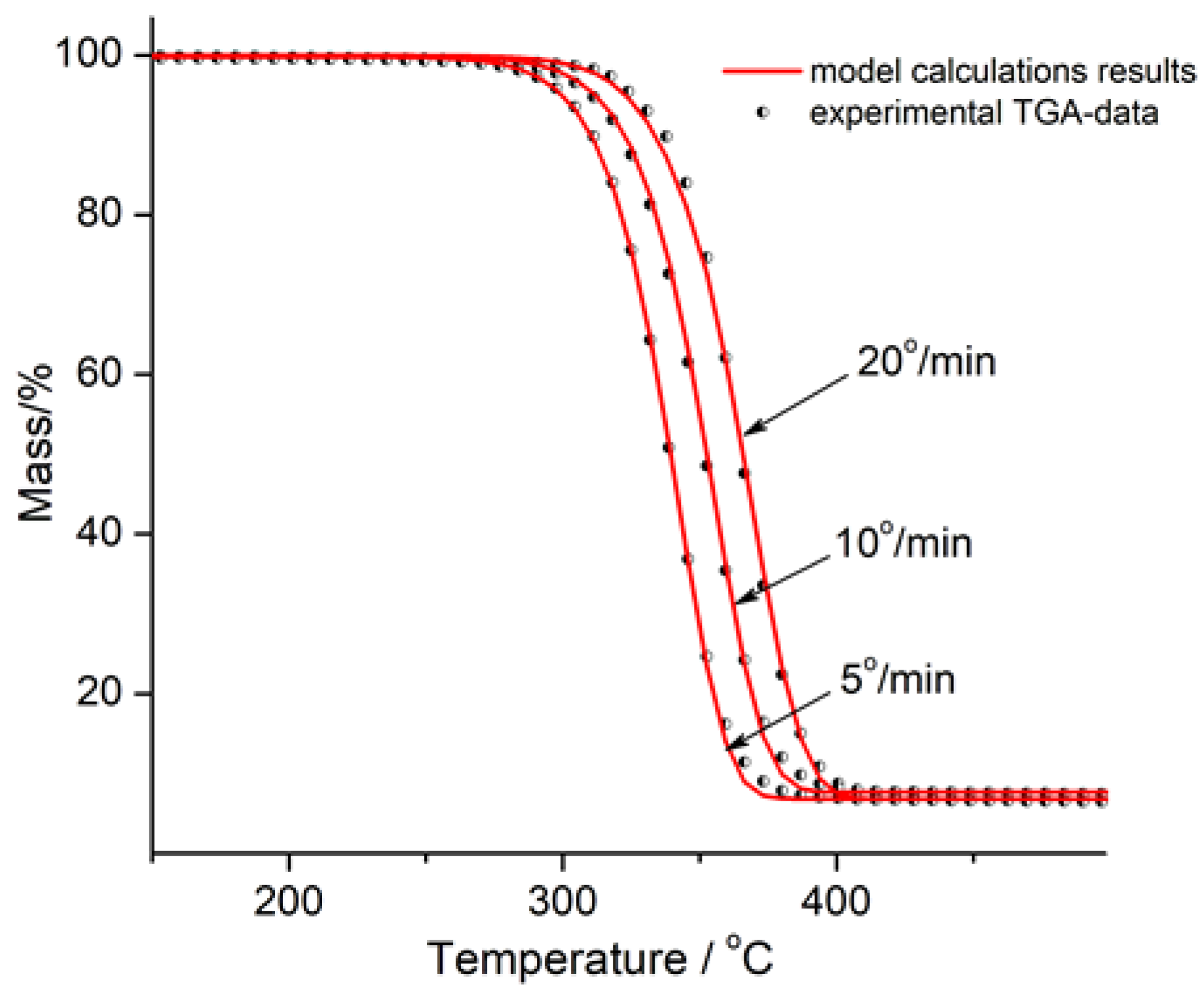

3.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis of PLA/Na-MMT and PLA/GnP Compositions

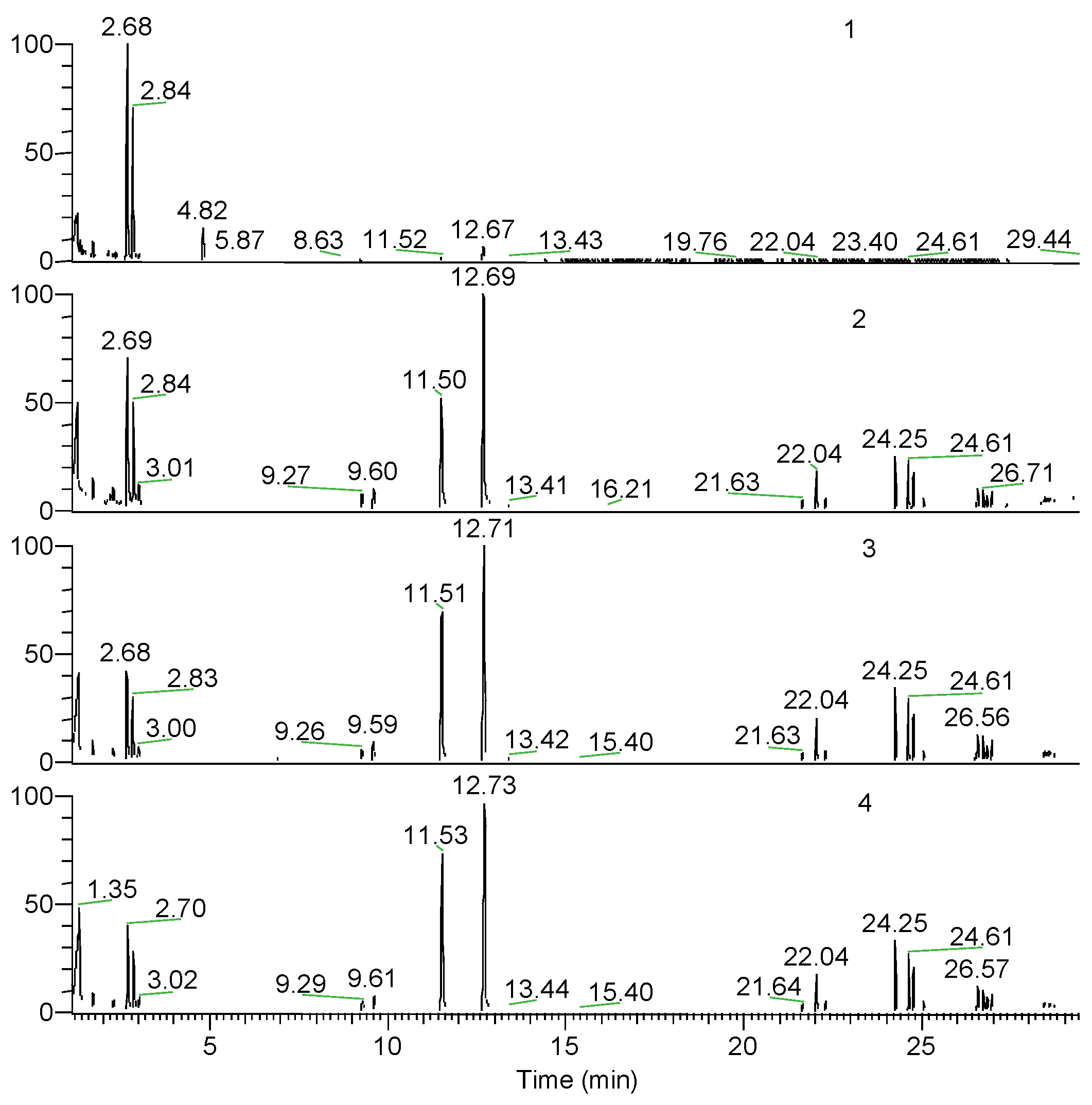

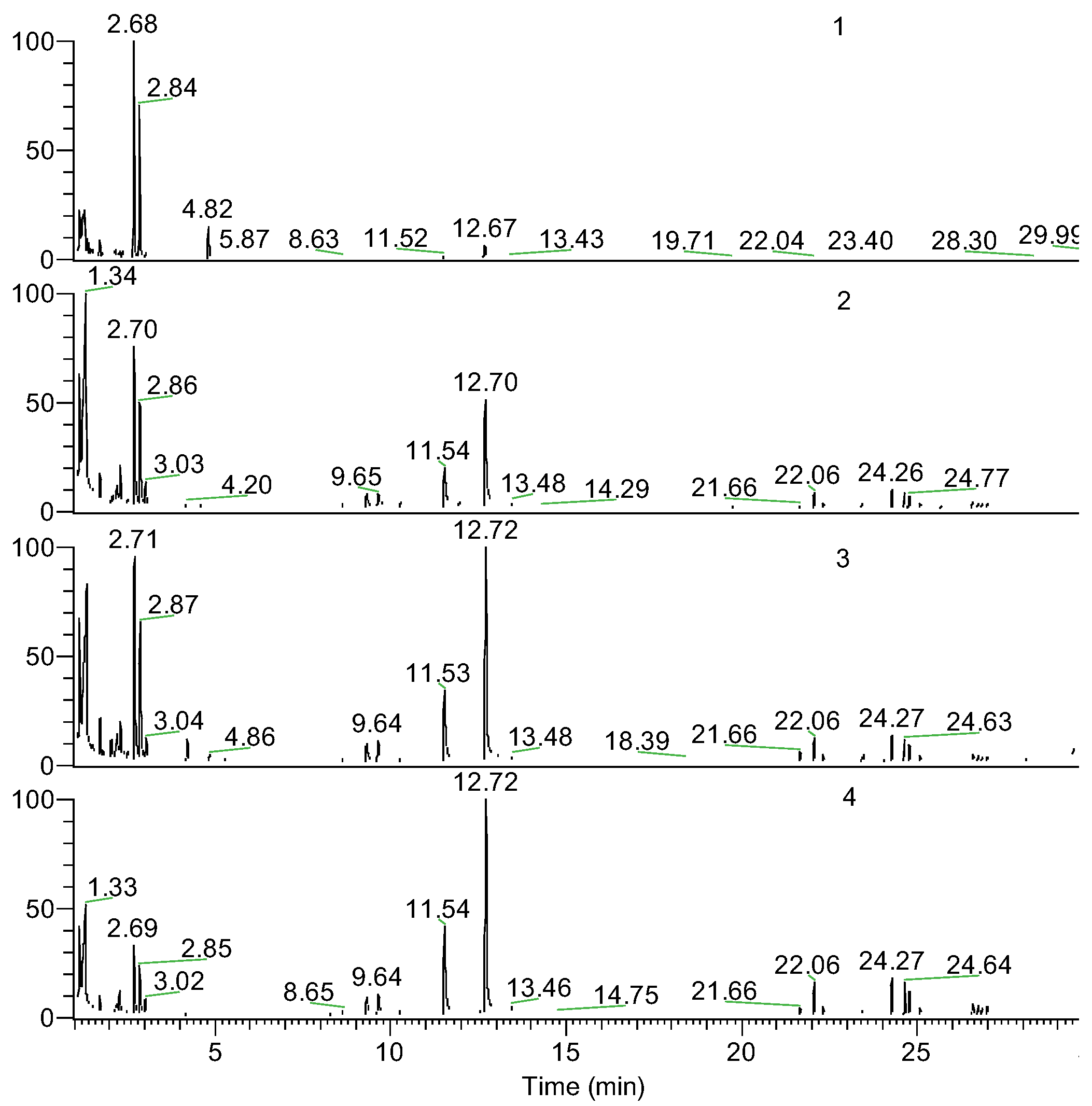

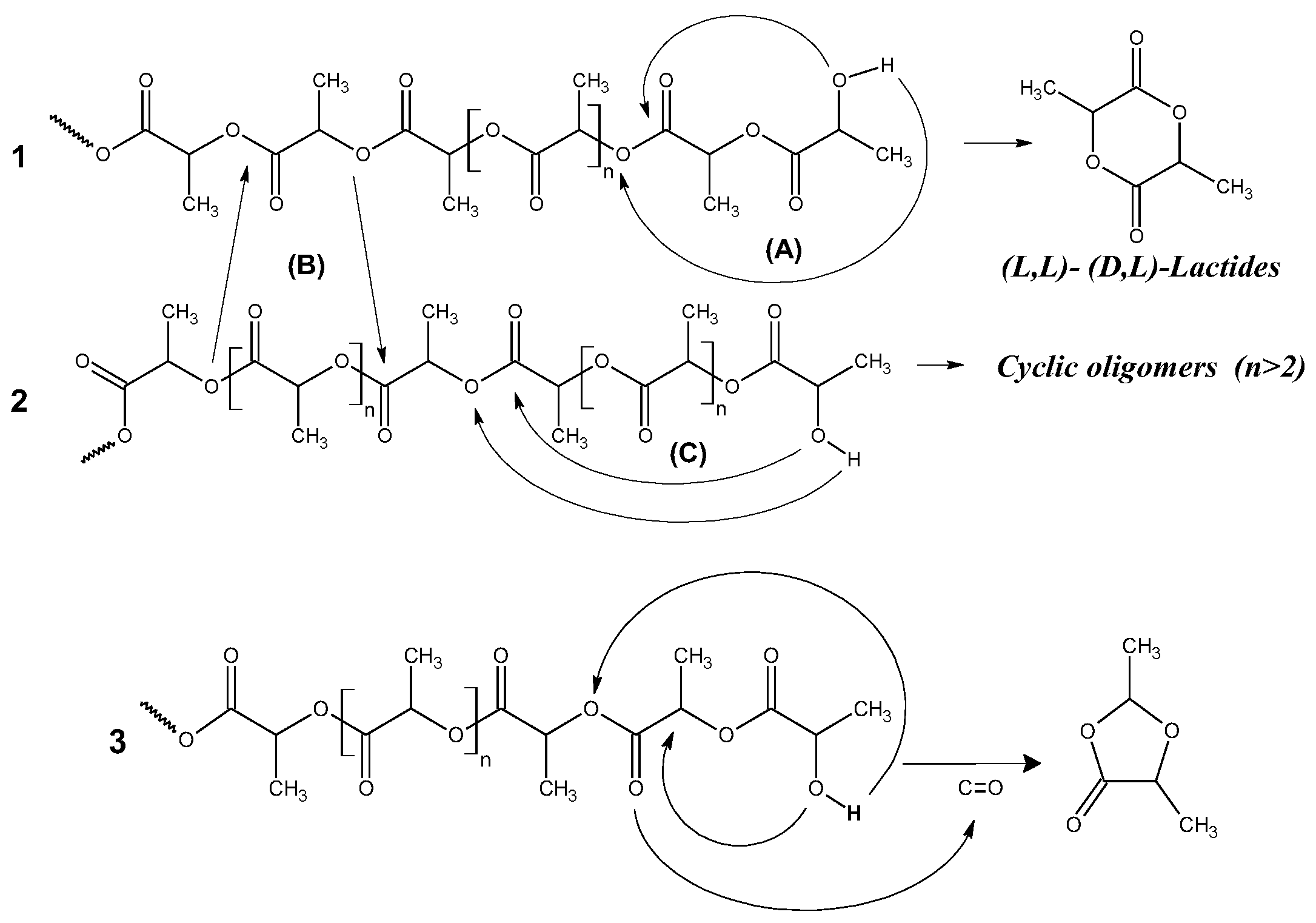

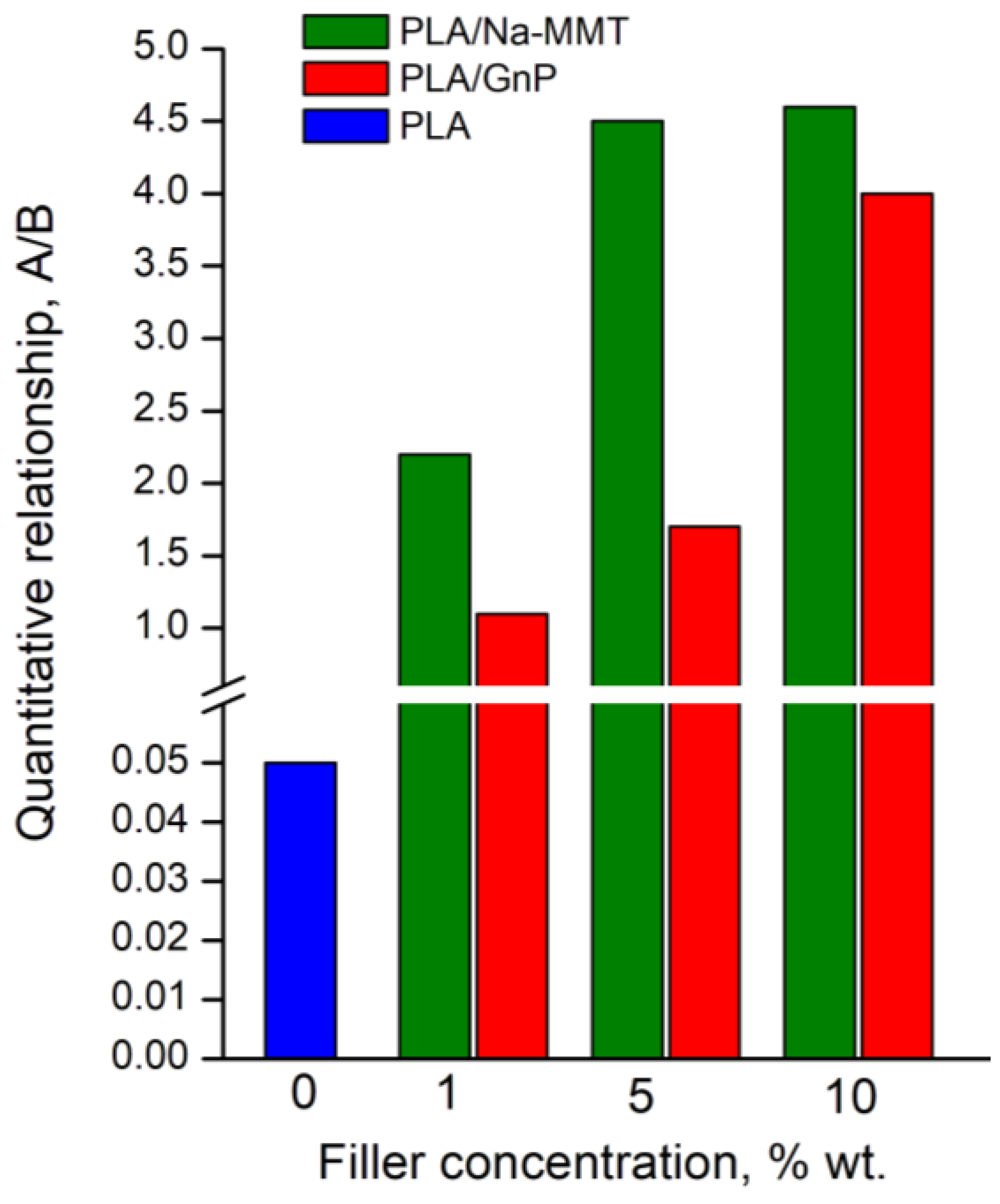

3.4. Pyrolysis–Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (PyGCMS) of PLA, PLA/Na-MMT and PLA/GnP Compositions

| Retention time (min) | Pyrolysis products | PAi (wt.%) | |||

| 0 | 1 | 5 | 10 | ||

| 1.32 | Acrylic acid | 9.10 | 8.90 | 8.00 | 9.83 |

| 2.15 | Vinylacetic acid | 1.48 | 0.80 | 0.36 | 0.23 |

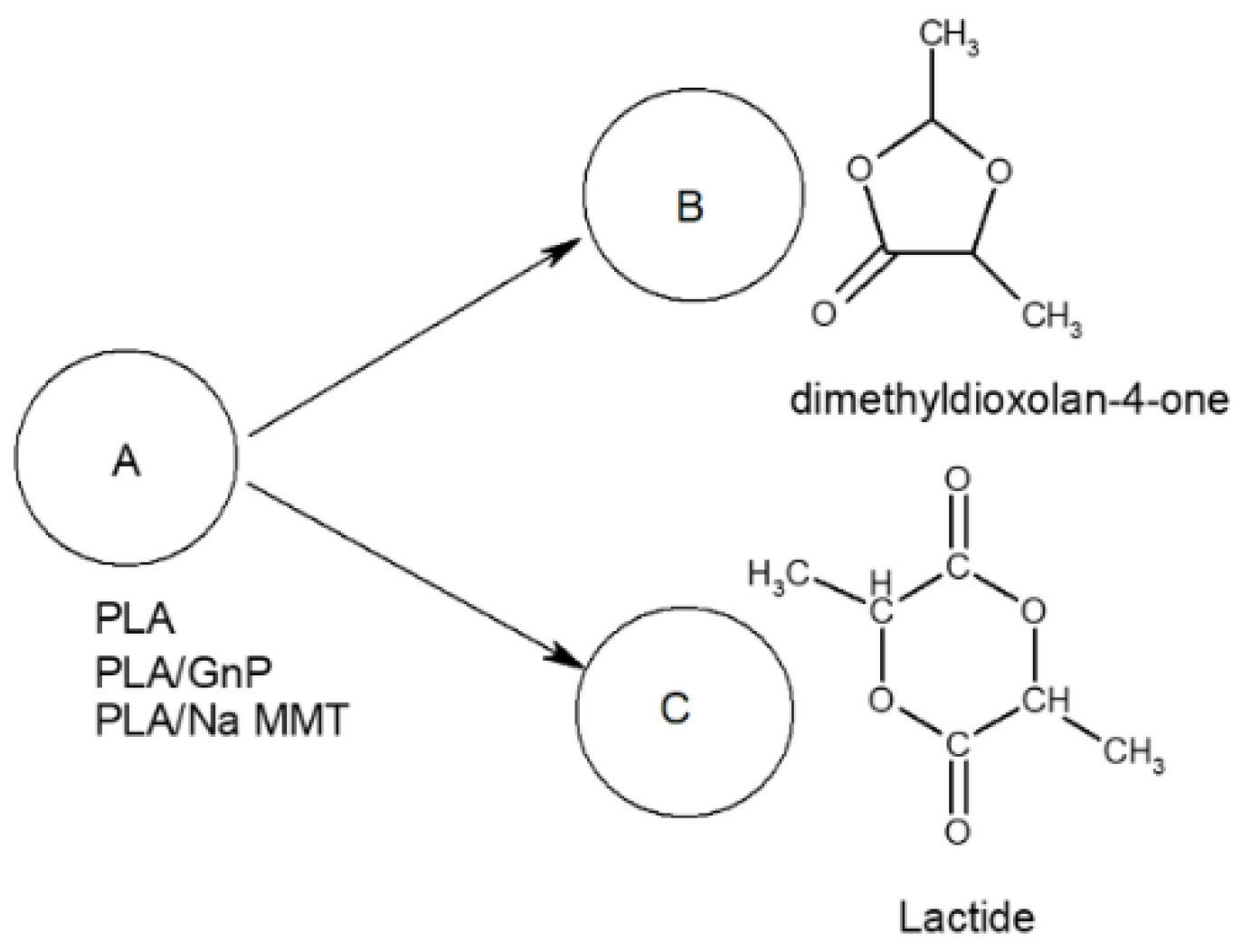

| 2.65 | cis-1,3-dimethyldioxolan-4-one | 49.03 | 15.29 | 9.18 | 8.99 |

| 2.8 | trans-1,3-dimethyldioxolan-4-one | 34.60 | 10.65 | 6.45 | 6.09 |

| 11.48 | meso-lactide | 0.85 | 11.29 | 15.54 | 16.92 |

| 12.69 | D,L-lactide | 2.85 | 21.87 | 22.04 | 22.06 |

| 21.6 ÷ 22.2 | Trimer (n=3) | 0.45 | 5.23 | 6.32 | 5.54 |

| 24.2 ÷ 24.7 | Tetrame (n=4) | 0.54 | 13.56 | 18.64 | 18.30 |

| 26.5 ÷ 26.9 | Pentamer (n=5) | 0.00 | 5.88 | 8.34 | 7.56 |

| Unidentified compounds | 1.11 | 6.52 | 5.12 | 4.47 | |

| Retention time (min) | Pyrolysis products | PAi (wt.%) | |||

| 0 | 1 | 5 | 10 | ||

| 1.36 | Acrylic acid | 9.10 | 25.91 | 16.39 | 13.33 |

| 2.19 | Vinylacetic acid | 1.48 | 2.13 | 2.25 | 1.06 |

| 2.7 | cis-1,3-dimethyldioxolan-4-one | 49.03 | 21.70 | 20.86 | 9.14 |

| 2.85 | trans-1,3-dimethyldioxolan-4-one | 34.60 | 14.01 | 14.10 | 6.43 |

| 11.53 | meso-lactide | 0.85 | 5.26 | 7.21 | 11.78 |

| 12.71 | D,L-lactide | 2.85 | 14.56 | 21.72 | 28.40 |

| 21.6÷22.2 | Trimer (n=3) | 0.45 | 3.06 | 3.78 | 6.17 |

| 24.2÷24.7 | Tetrame (n=4) | 0.54 | 6.23 | 6.34 | 12.36 |

| 26.5÷26.9 | Pentamer (n=5) | 0.00 | 2.20 | 1.91 | 4.33 |

| Unidentified compounds | 1.11 | 4.95 | 5.43 | 6.98 | |

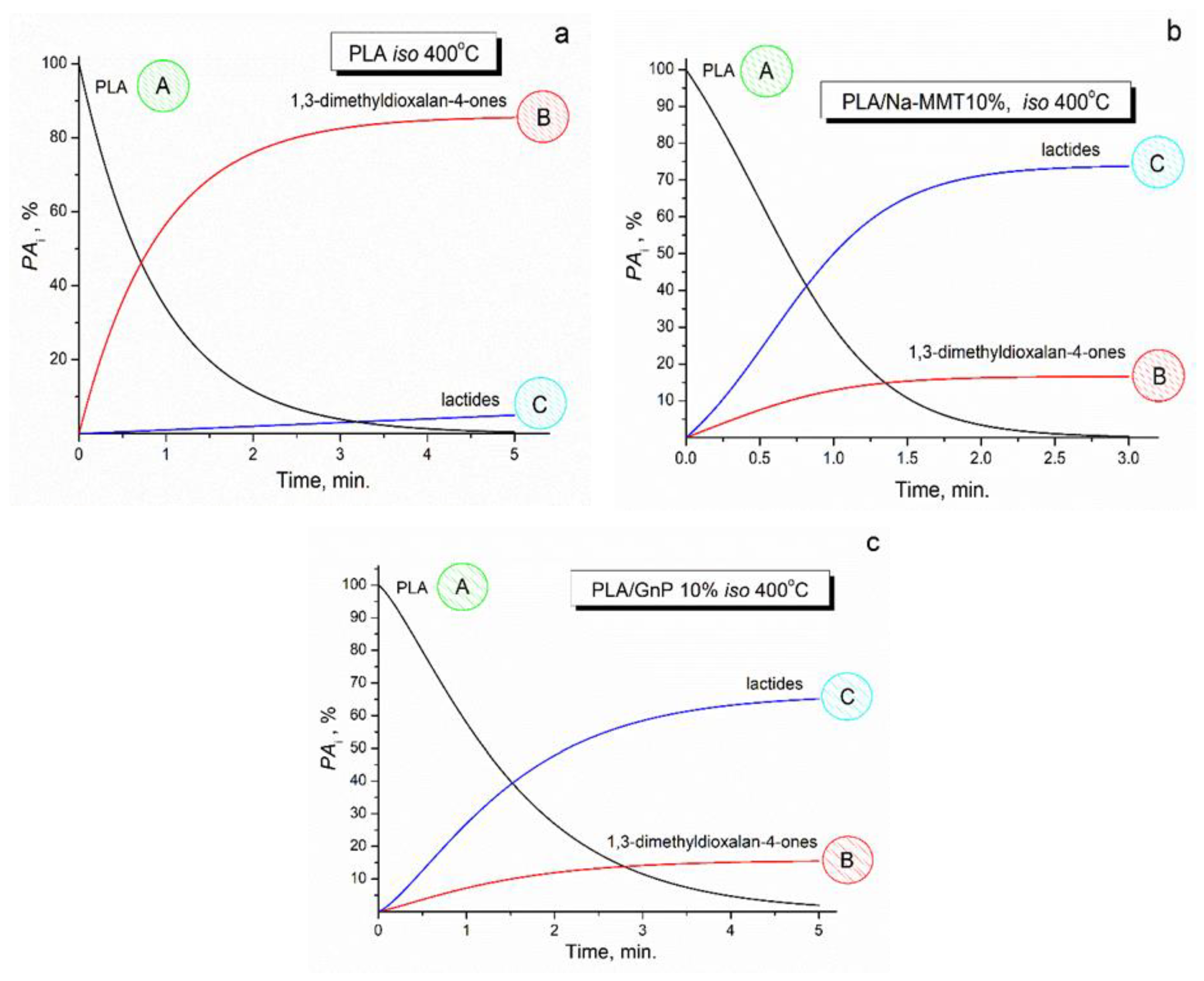

3.5. Kinetic Analysis of Thermal Degradation for PLA, PLA/Na-MMT and PLA/GnP Compositions

4. Conclusions

- Morphological analysis using AFM showed successful incorporation of fillers into the PLA matrix. Na-MMT demonstrated intercalation and exfoliation processes, while GnP formed interconnected layers with preferential orientation.

-

Thermal behavior investigation via DSC revealed that:Both fillers Na-MMT and GnP acted as nucleating agents, increasing PLA crystallinity;Na-MMT showed more significant nucleating effect on crystallinity of PLA than GnP (up to 39.7%);

-

Thermal stability assessment using TGA demonstrated:Na-MMT decreased thermal stability with increasing concentration by catalytical effect of Na-MMT on PLA depolymerization through an unzipping mechanism; In contrast to Na-MMT GnP improved thermal stability of PLA composition (growth of Ton and Tmax) due to the formation of a physical barrier by GnP particles that hinders mass transfer, ultimately reducing material loss by volatilizing of degradation products during thermal decomposition.

-

Degradation mechanism study by PYGCMS showed:Formation of lactides and dioxalanones as main degradation products; Change in product ratio depending on filler type and concentration; Different effects of Na-MMT and GnP on degradation pathways of PLA.

-

Kinetic modeling has successfully described the thermal degradation behavior of PLA-based materials through formal scheme of two-stage competing reactions where:The first stage produces 1,3-dimethyldioxalan-4-ones; The second stage leads to lactide formation; PLA follows first-order kinetics; PLA/Na-MMT exhibits first-order autocatalytic reactions; PLA/GnP shows Avrami-Erofeev type kinetics;GnP and Na-MMT fillers modify the degradation mechanism;Both fillers influence the ratio of degradation products;

-

The developed kinetic model provides:Accurate prediction of thermal degradation behavior; Quantitative description of reaction mechanisms; Insight into the influence of fillers on degradation processes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, T.S.; Bee, S.T. Polylactic Acid. A Practical Guide for the Processing, Manufacturing, and Applications of PLA. In A volume in Plastics Design Library, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Inc., 2019, 422 p. [CrossRef]

- Nofar, M.; Sacligil, D.; Carreau, P.J.; Kamal, M.R.; Heuzey, M.-C. Poly (lactic acid) blends: Processing, properties and applications. Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 125, 307–360. [CrossRef]

- Murariu, M.; Dubois, P. PLA composites: From production to properties. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2016, 107, 17–46. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zurayk, R.; Khalaf, A.; Alnairat, N.; Waleed, H.; Bozeya, A.; Abu-Dalo, D.; Rabba’a, M. Green polymer nanocomposites: bridging material innovation with sustainable industrial practice. Frontiers in Materials 2025, 12, 12:1701086. [CrossRef]

- Scaffaro, R.; Maio, A.; Gammino, M. Hybrid biocomposites based on polylactic acid and natural fillers from Chamaerops humilis dwarf palm and Posidonia oceanica leaves. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater 2022, 5, 1988–2001. [CrossRef]

- Scaffaro, R.; Maio, A.; Gammino, M. Electrospun polymeric nanohybrids with outstanding pollutants adsorption and electroactivity for water treatment and sensing devices. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater 2024, 7, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Jollands, M.; Parthasarathy R. Mechanical and thermal properties of melt processed PLA/organoclay nanocomposites. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2nd International Conference on Mining, Material and Metallurgical Engineering, Bangkok, Thailand, 17–18 March 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kontou, E.; Niaounakis, M.; Panayiotis, G. Comparative study of PLA nanocomposites reinforced with clay and silica nanofillers and their mixtures. J Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 122, 1519–1529. [CrossRef]

- Botta, L.; Scaffaro, R.; Sutera, F.; Mistretta, M.C. Reprocessing of PLA/Graphene Nanoplates Nanocomposites. Polymers 2018, 10, 18. [CrossRef]

- Sinha Ray, S.; Bousmina, M. Biodegradable polymers and their layered silicate nanocomposites: In greening the 21st century materials world. Progress in Materials Science 2005, 50 (8), 962–1079. [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Hedenqvist, M. S. A Review on Barrier Properties of Poly(LacticAcid)/Clay Nanocomposites. Polymers 2020, 12(5), 1095. [CrossRef]

- Kalendova, A.; Smotek, J.; Stloukal, P.; Kracalik, K.M.; Slouf, M.; Laske, S. Transport Properties of PLA/Clay Nanocomposites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2019, 59, 2498–2501. [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.-M.; Wub, S.-H.; Lin, G.-G.; Don, T.-M. Unusual mechanical properties of melt-blended poly(lactic acid) (PLA)/clay nanocomposites. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 52, 193–206. [CrossRef]

- Kuruma, M.; Bandyopadhyay, J.; Sinha Ray, S. Thermal Degradation Characteristic and Flame Retardancy of Polylactide-Based Nanobiocomposites. Molecules, 2018, 23(10). [CrossRef]

- Angelova, P. Mechanical and thermal properties of PLA based nanocomposites with graphene and carbon nanotubes. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics 2019, 49, 241–256. [CrossRef]

- Maio, A.; Pibiri, I.; Morreale, M.; La Mantia, F.P.; Scaffaro, R. An Overview of Functionalized Graphene Nanomaterials for Advanced Applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11(7), 1717. [CrossRef]

- Gulino, E.F.; Citarrella, M.C.; Maio, A.; Scaffaro R. An innovative route to prepare in situ graded crosslinked PVA graphene electrospun mats for drug release. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2022, 155, 106827. [CrossRef]

- Scaffaro, R.; Maio, A.; Gulino, E.F.; Morreale, M.; La Mantia, F.P. Effects of Nanoclay on the Mechanical Properties, Carvacrol Release and Degradation of a PLA/PBAT Blend. Materials 2020, 13(4), 983. [CrossRef]

- Rucinska, K.; Florjanczyk, Z.; Debowski, M.; Gołofit, T.; Malinowski, R. New Organophilic Montmorillonites with Lactic Acid Oligomers and Other Environmentally Friendly Compounds and Their Effect on Mechanical Properties of Polylactide (PLA). Materials 2021, 14, 6286. [CrossRef]

- Bourbigot, S.; Fontaine, G. Flame retardancy of polylactide: an overview. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 1413–1422. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Fukui, I.; Daimon, H.; Fujie, K. Poly(l-lactide) XI. Lactide formation by thermal depolymerisation of poly(L-lactide) in a closed system. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2003, 81, 501–509. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.J.; Nishida, H.; Shirai, Y.; Tokiwa, Y.; Endo, T. Thermal degradation behaviour of poly(lactic acid) stereocomplex. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2004, 86, 197–208. [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Nishida, H.; Shirai, Y.; Endo T. Effects of chain end structures on pyrolysis of poly(L-lactic acid) containing tin atoms. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2004, 84, 243–251. [CrossRef]

- McNeill, I.C.; Leiper H.A. Degradation studies of some polyesters and polycarbonates-2. Polylactide: degradation under isothermal conditions, thermal degradation mechanism and photolysis of the polymer. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1985, 11, 309–326. [CrossRef]

- Kopinke, F.D.; Mackenzie, K. Mechanistic aspects of the thermal degradation of poly(lactic acid) and poly(β-hydroxybutyric acid). J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 1997, 40–41, 43–53. [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.P.; Parres, F.; Lopez, J.; Jimenez A. Development of a novel pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method for the analysis of poly(lactic acid) thermal degradation products. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2013, 101, 150–155. [CrossRef]

- Usachev, S.V.; Lomakin, S.M.; Koverzanova, E.V.; Shilkina, N.G.; Prut, E.V.; Rogovina, S.Z.; Berlin, A.A.; Levina, I.I. Thermal degradation of various types of polylactides research. The effect of reduced graphite oxide on the composition of the PLA4042D pyrolysis products. Thermochimica Acta 2022, 712, 179227. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, F.; Perez-Maqueda, L.A.; Sanchez-Jimenez, P.E.; Perejon, A.; Santana, O.O.; Maspoch, M.Ll. Enhanced general analytical equation for the kinetics of the thermal degradation of poly(lactic acid) driven by random scission. Polymer Testing 2013, 32 (5), 937–945. [CrossRef]

- Shanshan, Lv.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, H. Thermal and thermo-oxidative degradation kinetics and characteristics of poly (lactic acid) and its composites. Waste Management 2019, 87, 335–344. [CrossRef]

- Chrissafis, K. Detail kinetic analysis of the thermal decomposition of PLA with oxidized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Thermochimica Acta 2010, 511, 163–167. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Criado, J.; Perez-Maqueda, L.; Popescu, C.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim Acta 2011, 520 (1–2), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S. Isoconversional methods: The many uses of variable activation energy. Thermochimica Acta 2024, 733, 179701. [CrossRef]

- Bayon, R.; Garcia-Rojas, R.; Rojas, E.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.M. Assessment of isoconversional methods and peak functions for the kinetic analysis of thermogravimetric data and its application to degradation processes of organic phase change materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 13879–13899. [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, D.K.; Singh, A.K.; Chakraborty, J.P. Model-free isoconversional methods to determine the intrinsic kinetics and thermodynamic parameters during pyrolysis of boiled banana peel: influence of inorganic species. Bioresource Technology Reports 2023, 24, 101676. [CrossRef]

- Budrugeac, P.; Segal, E. Application of isoconversional and multivariate non-linear regression methods for evaluation of the degradation mechanism and kinetic parameters of an epoxy resin. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2008, 93 (6), 1073–1080. [CrossRef]

- Lomakin, S.; Brevnov, P.; Koverzanova, E.; Usachev, S.; Shilkina, N.; Novokshonova, L.; Krasheninnikov, V.; Berezkina, N.; Gajlewicz, I.; Lenartowicz-Klik, M. The effect of graphite nanoplates on the thermal degradation and combustion of polyethylene. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2017, 128, 275–280. [CrossRef]

- Lomakin, S.M.; Rogovina, S.Z.; Grachev, A.V.; Prut, E.V.; Alexanyan, Ch.V. Thermal degradation of biodegradable blends of polyethylene with cellulose and ethylcellulose. Thermochimica Acta 2011, 521 (1–2), 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.W.; Sterzel, H.J.; Wegner, G. Investigation of the structure of solution grown crystals of lactide copolymers by means of chemical reactions. Kolloid-Zeitschrift und Zeitschrift für Polymere 1973, 251, 980–990. [CrossRef]

- Magonov, S.N.; Whangbo, M.-H. Surface Analysis with STM and AFM: Experimental and Theoretical Aspects of Image Analysis. Wiley-VCH, Germany, 2008, 335.

- Lomakin, S.; Mikheev, Y.; Usachev, S.; Rogovina, S.; Zhorina, L.; Perepelitsina, E.; Levina, I.; Kuznetsova, O.; Shilkina, N.; Iordanskii, A.; Berlin, A. Evaluation and Modeling of Polylactide Photodegradation under Ultraviolet Irradiation: Bio-Based Polyester Photolysis Mechanism. Polymers 2024, 16, 985. [CrossRef]

- Opfermann, J. Kinetic Analysis Using Multivariate Non-linear Regression. I. Basic concepts. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2000, 60, 641–658. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, T. Applicability of Friedman plot. Journal of Thermal Analysis 1986, 31, 547–551. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Heating | Tg (°C) | Tcc (°C) | Tm (°C) | ΔHcc (J/g) | ΔHm (J/g) | χ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | first | 56.6 | 114 | 163.2 | 2.0 | -30.8 | 30.8 |

| second | 61.3 | n/a | 158 | n/a | -0.6 | 0.7 | |

| PLA/GnP 1 wt.% |

first | 54.5 | 113.1 | 162.4 | 1.8 | -31.8 | 32.2 |

| second | 61.3 | 128.6 | 159.0 | 7.1 | -10.9 | 4.0 | |

| PLA/GnP 5 wt.% |

first | 64.6 | 110.5 | 162.8 | 5.8 | -31.6 | 27.7 |

| second | 61.1 | 127.1 | 158.5 | 16.5 | -23.4 | 7.8 | |

| PLA/GNP 10 wt.% | first | 53.9 | 113.2 | 162.2 | n/a | -32.1 | 34.2 |

| second | 62.0 | 121.3 | 157/162* | 25.5 | -32.2 | 3.9 | |

| PLA/MMT 1 wt.% | first | 51.7 | n/a | 163.5 | n/a | -36.8 | 39.7 |

| second | 61.2 | n/a | 158.3 | n/a | -0.8 | 0.9 | |

| PLA/MMT 5 wt.% | first | 51.0 | n/a | 159.1 | n/a | -35.5 | 39.0 |

| second | 61.1 | 133.2 | 159.1 | 0.4 | -2.0 | 1.9 | |

| PLA/MMT 10 wt.% | first | 66.4 | 113.9 | 160.8 | 2.7 | -27.2 | 29.0 |

| second | 60.8 | 132.8 | 158.1 | 0.9 | -3.4 | 3.0 |

| Sample | Тon (°C) | Тmax (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| PLA | 331 | 368 |

| PLA/GnP 1 wt.% | 333 | 372 |

| PLA/GnP 5 wt.% | 340 | 375 |

| PLA/GnP 10 wt.% | 345 | 380 |

| PLA/Na-MMT 1 wt.% | 329 | 366 |

| PLA/ Na-MMT 5 wt.% | 319 | 361 |

| PLA/ Na-MMT 10 wt.% | 313 | 356 |

| Composition | The quantitative relationship (A) : (B) |

|---|---|

| PLA | 1.0 : 18.0 |

| PLA/Na-MMT 1 wt.% | 2.2 : 1.0 |

| PLA/ Na-MMT 5 wt.% | 4.5 : 1.0 |

| PLA/ Na-MMT 10 wt.% | 4.6 : 1.0 |

| PLA/GnP 1 wt.% | 1.1 : 1.0 |

| PLA/GnP 5 wt.% | 1.7 : 1.0 |

| PLA/GnP 10 wt.% | 4.0 : 1.0 |

| Name | f(co,cf) | Reaction type |

|---|---|---|

| F1 F2 Fn R2 R3 D1 D2 D3 D4 B1 Bna C1-X Cn-X A2 A3 An |

c c2 cn 2 · c1/2 3 · c2/3 0.5/(1 - c) -1/ln(c) 1.5 · e1/3(c-1/3 - 1) 1.5/(c-1/3 - 1) co · cf con · cfa c · (1+Kcat · X) cn · (1+Kcat · X) 2 · c · (-ln(c))1/2 3 · c · (-ln(c))2/3 N · c · (-ln(c))(n-1)/n |

first-order reaction second-order reaction nth-order reaction two-dimensional phase boundary reaction three-dimensional phase boundary reaction one-dimensional diffusion two-dimensional diffusion three-dimensional diffusion (Jander's type) three-dimensional diffusion (Ginstling-Brounstein type) simple Prout-Tompkin’s equation expanded Prout-Tompkin’s equation (na) first-order reaction with autocatalysis through the reactants, X. X = cf nth-order reaction with autocatalysis through the reactants, X two-dimensional nucleation three-dimensional nucleation n-dimensional nucleation/nucleus growth according to Avrami/Erofeev |

| Composition | Model Reaction | Parameter | Value | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | Model Step 1: first-order reaction |

lgA1, s-1 E1, kJ/mol |

10.7 176.8 |

Correlation coefficient: 0.999388 Durbin-Watson Value: .357 |

| Model Step 2: first-order reaction |

lgA2, s-1 E2, kJ/mol |

16.9 229.3 |

||

| PLA/Na-MMT 10 wt.% |

Model Step 1: first-order reaction with autocatalysis |

lgA1, s-1 E1, kJ/mol lgKcat |

11.1 170.1 0.5 |

Correlation coefficient: 0.999402 Durbin-Watson Value: 0.081 |

| Model Step 2: first-order reaction with autocatalysis |

lgA2, s-1 E2, kJ/mol lgKcat |

11.7 198.0 0.8 |

||

| PLA/GnP 10 wt.% |

Model Step 1: n-dim. Avrami-Erofeev |

lgA1, s-1 E1, kJ/mol dimention1 |

9.5 142.3 1.20 |

Correlation coefficient: 0.999889 Durbin-Watson Value: 0.272 |

| Model Step 2: n-dim. Avrami-Erofeev |

lgA2, s-1 E2, kJ/mol dimention2 |

12.5 178.6 1.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).