Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Methods

Ethical Approval

Sampling

- Time between sampling and analysis not exceeding 48h

- Each of the five samples was positive for all the three genes (E, N, and Rdrp).

- Five samples showed the lowest Ct values among the four genes tested.

- The type of transport medium was identical for all selected samples.

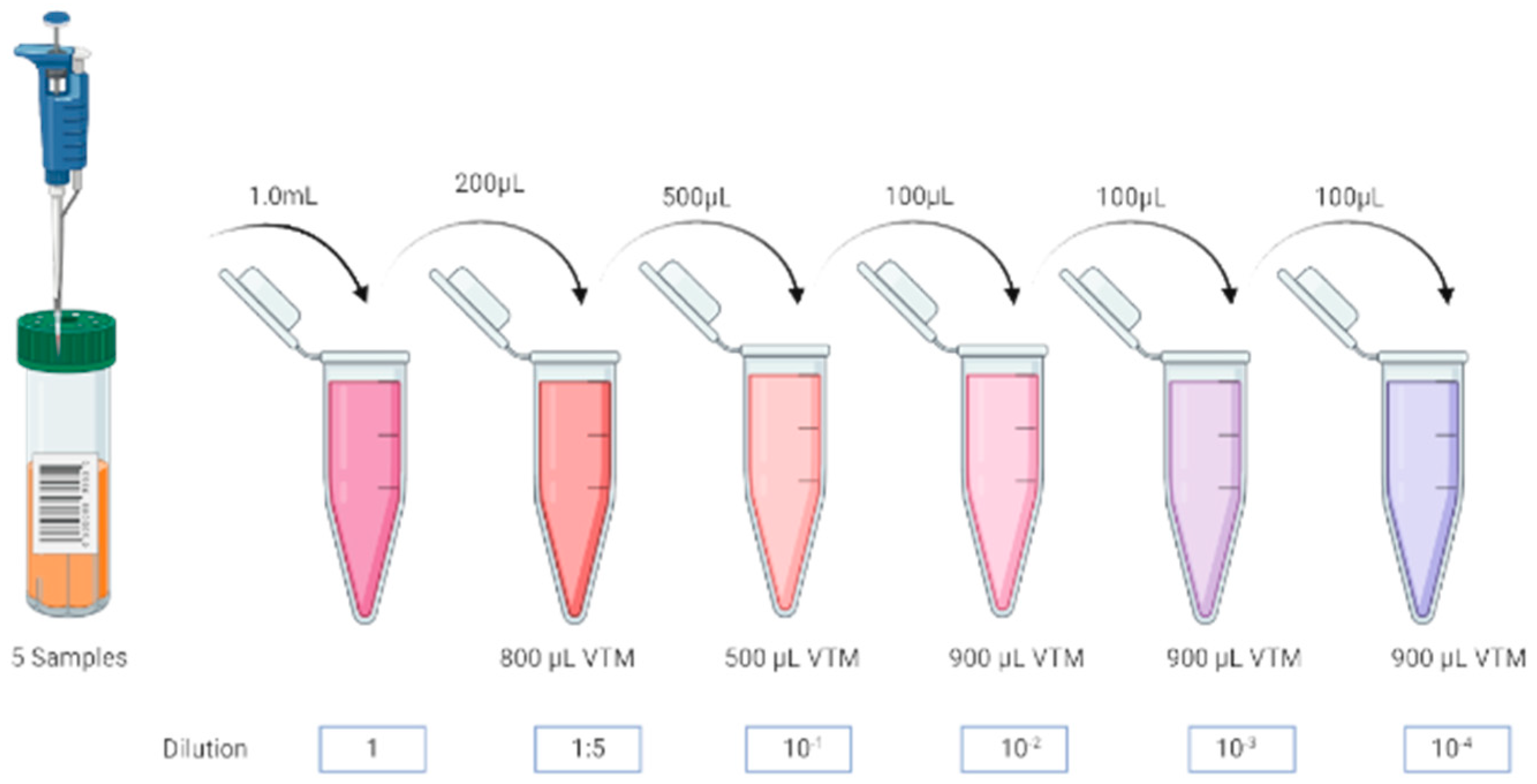

Samples Preparation and Pooling

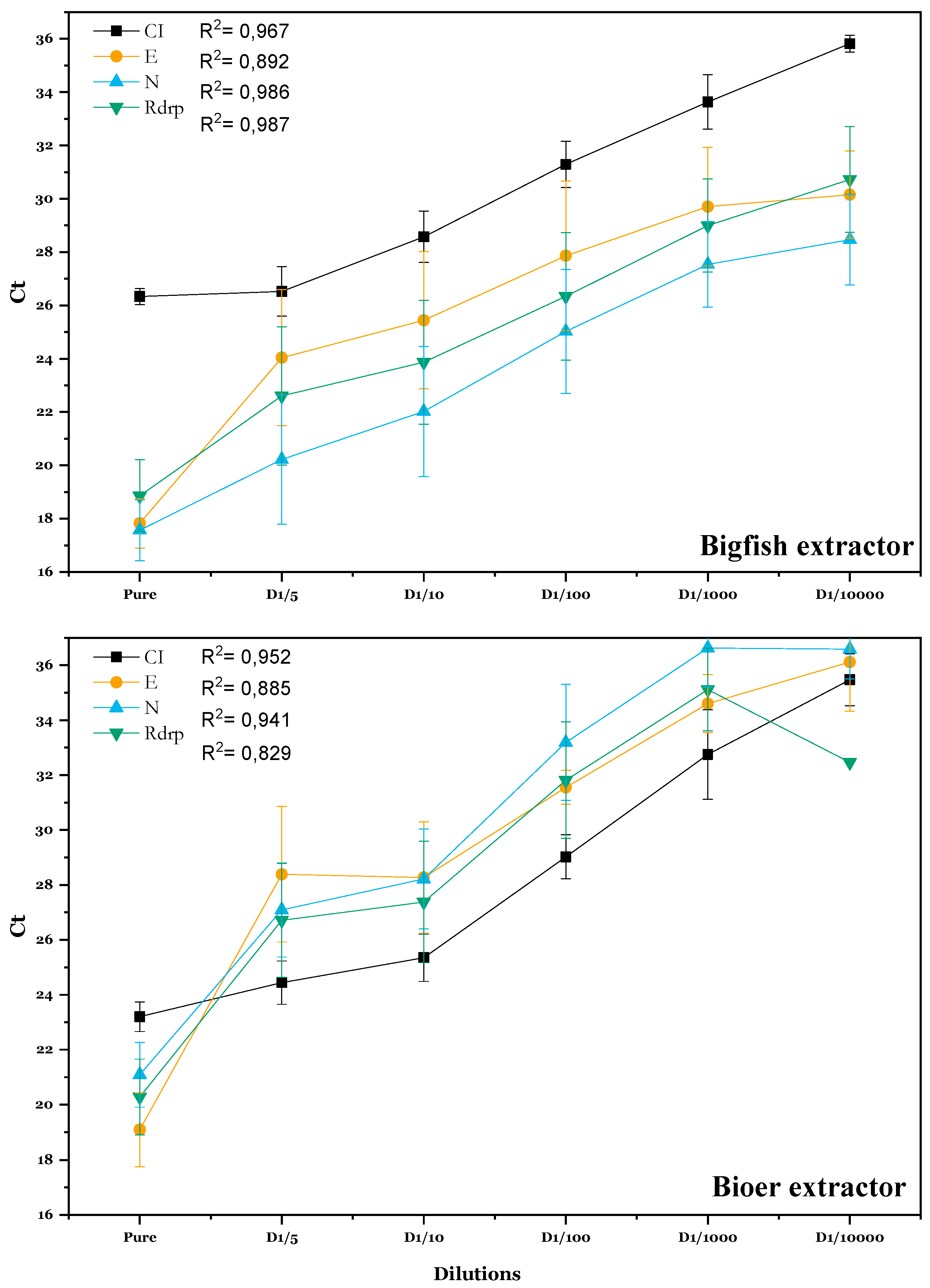

Samples Dilution

Pooling Strategies

Nucleic Acid Extraction

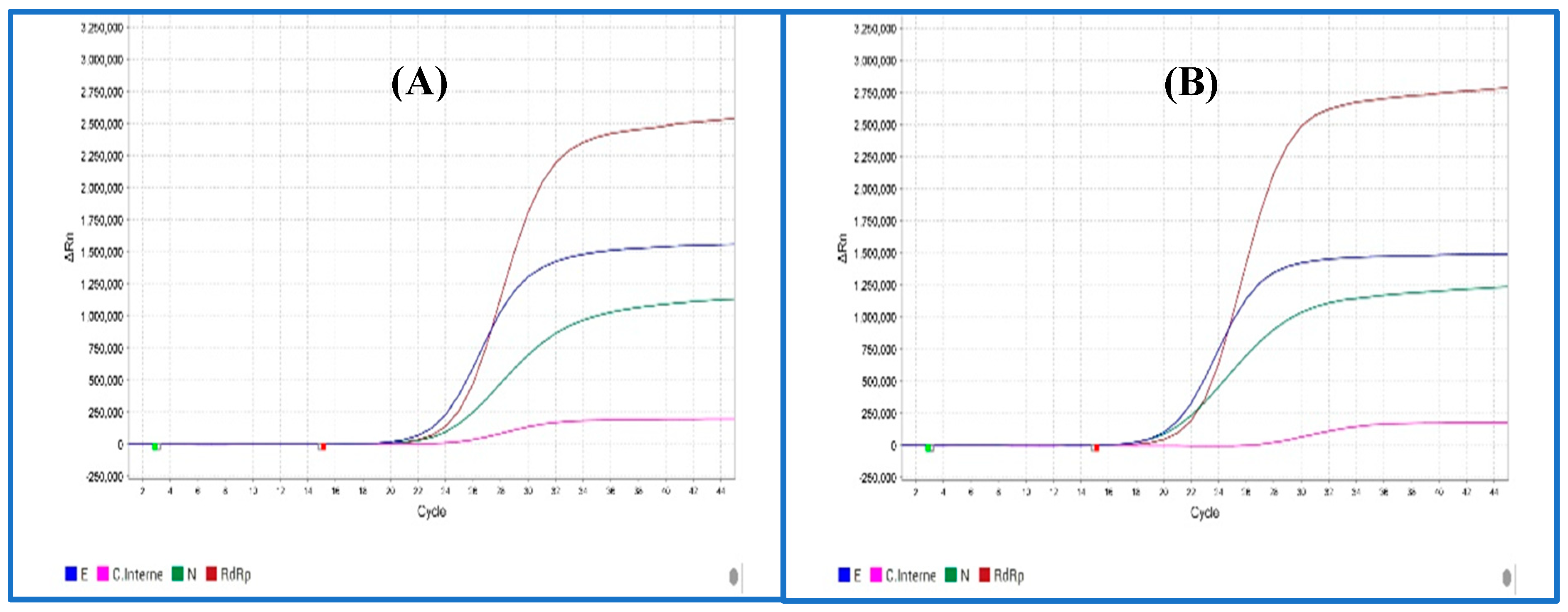

SARS-CoV2 RNA Detection by RT-qPCR

Statistical Analysis

Results

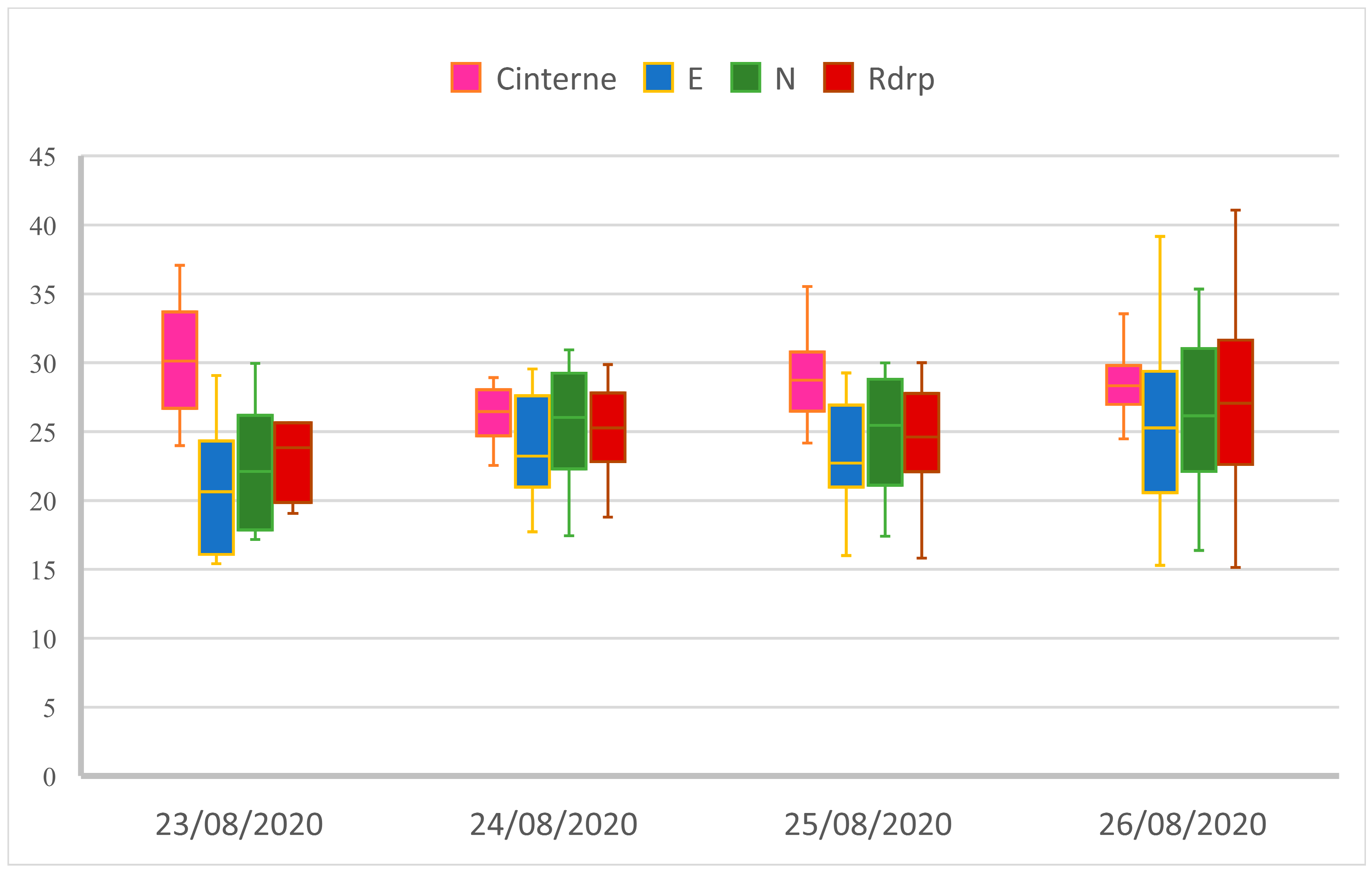

Comparing Extraction Kits

Simulation of a Non-Compliant Nasopharyngeal Swab Sample

Impact of Pooling Strategy on SARS-CoV2 RT-qPCR Results

Technical Evaluation of Pooling Strategy

Economic Evaluation of Pooling Strategy

Discussion

Conclusion

Funding

Declaration of Competing Interests

Sequence Information

References

- Luk, H.K.H.; Li, X.; Fung, J.; Lau, S.K.P.; Woo, P.C.Y. Molecular epidemiology, evolution and phylogeny of SARS coronavirus. Infect. Genet. Evol. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2019, 71, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Ali, A.; Siddique, R.; Nabi, G. Novel coronavirus is putting the whole world on alert. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 252–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khailany, R.A.; Safdar, M.; Ozaslan, M. Genomic characterization of a novel SARS-CoV-2. Gene Rep. 2020, 19, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Y.A. Properties of Coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2. Malays. J. Pathol. 2020, 42, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotfi, M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Rezaei, N. COVID-19: Transmission, prevention, and potential therapeutic opportunities. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2020, 508, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonny, V.; Maillard, A.; Mousseaux, C.; Plaçais, L.; Richier, Q. COVID-19: physiopathologie d’une maladie à plusieurs visages. Rev. Médecine Interne 2020, 41, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Reports. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed on Sep 15, 2020).

- Dong, E.; Du, H.; Gardner, L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 533–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Freedman, D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marca, A.L.; Capuzzo, M.; Paglia, T.; Roli, L.; Trenti, T.; Nelson, S.M. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): a systematic review and clinical guide to molecular and serological in-vitro diagnostic assays. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 41, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascella, M.; Rajnik, M.; Cuomo, A.; Dulebohn, S.C.; Di Napoli, R. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Pan, Y.; Cheng, S.M.S.; Hui, K.P.Y.; Krishnan, P.; Liu, Y.; Ng, D.Y.M.; Wan, C.K.C.; Yang, P.; Wang, Q.; et al. Molecular Diagnosis of a Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Causing an Outbreak of Pneumonia. Clin. Chem. 2020, 66, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Du, R.-H.; Li, B.; Zheng, X.-S.; Yang, X.-L.; Hu, B.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Xiao, G.-F.; Yan, B.; Shi, Z.-L.; et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gard, L.; Fliss, M.A.; Bosma, F.; ter Veen, D.; Niesters, H.G.M. Validation and verification of the GeneFinderTM COVID-19 Plus RealAmp kit on the ELITe InGenius® instrument. J. Virol. Methods 2022, 300, 114378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health, C. for D. and R. qRT-PCR Emergency Use Authorizations for Medical Devices. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices (accessed on Sep 30, 2020).

- Brianna, D.H.; Christopher, B.; Joshua, T.; Christopher, M. Pooled Testing. Available online: https://bilder.shinyapps.io/PooledTesting/ (accessed on Jul 6, 2023).

- Wang, X.; Yao, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, M.; Shao, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, H. Limits of Detection of 6 Approved RT–PCR Kits for the Novel SARS-Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin. Chem. 2020, 66, 977–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.-W.; Yip, C.C.-Y.; To, K.K.-W.; Tang, T.H.-C.; Wong, S.C.-Y.; Leung, K.-H.; Fung, A.Y.-F.; Ng, A.C.-K.; Zou, Z.; Tsoi, H.-W.; et al. Improved Molecular Diagnosis of COVID-19 by the Novel, Highly Sensitive and Specific COVID-19-RdRp/Hel Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay Validated In Vitro and with Clinical Specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelin, I.; Aharony, N.; Shaer-Tamar, E.; Argoetti, A.; Messer, E.; Berenbaum, D.; Shafran, E.; Kuzli, A.; Gandali, N.; Hashimshony, T.; et al. Evaluation of COVID-19 RT-qPCR test in multi-sample pools. medRxiv 2020, 2020.03.26.20039438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, A.K.A.; Demoliner, M.; Gularte, J.S.; Hansen, A.W.; Schallenberger, K.; Mallmann, L.; Hermann, B.S.; Heldt, F.H.; Almeida, P.R. de; Fleck, J.D.; et al. Comparison of Different Kits for SARS-CoV-2 RNA Extraction Marketed in Brazil. bioRxiv 2020, 2020.05.29.122358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhoff, O.M.; Bellini, E.; Lienhard, R.; Stark, W.J.; Bechtold, P.; Grass, R.N.; Bosshard, P.P.; Levesque, M.P. Comparison of RNA extraction methods for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR 2020, 2020.08.13.20172494. [CrossRef]

- Chu, A.W.-H.; Chan, W.-M.; Ip, J.D.; Yip, C.C.-Y.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Yuen, K.-Y.; To, K.K.-W. Evaluation of simple nucleic acid extraction methods for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal and saliva specimens during global shortage of extraction kits. J. Clin. Virol. Off. Publ. Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 2020, 129, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantara, J.C.; Alharbi, B.; Almotairi, Y.; Alam, M.J.; Muddathir, A.R.M.; Alshaghdali, K. Analysis of preanalytical errors in a clinical chemistry laboratory: A 2-year study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e29853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagnostic samples: from the patient to the laboratory ; the impact of preanalytical variables on the quality of laboratory results, Guder, W.G., Ed.; 4., updated ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Weinheim, 2014; ISBN 978-3-527-32307-4. [Google Scholar]

- Falasca, F.; Sciandra, I.; Di Carlo, D.; Gentile, M.; Deales, A.; Antonelli, G.; Turriziani, O. Detection of SARS-COV N2 Gene: Very low amounts of viral RNA or false positive? J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 133, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, D.; Aita, A.; Navaglia, F.; Franchin, E.; Fioretto, P.; Moz, S.; Bozzato, D.; Zambon, C.-F.; Martin, B.; Prà, C.D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA identification in nasopharyngeal swabs: issues in pre-analytics. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM 2020, 58, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Simundic, A.-M.; Plebani, M. Potential preanalytical and analytical vulnerabilities in the laboratory diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020, 58, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, R. The Detection of Defective Members of Large Populations. Ann. Math. Stat. 1943, 14, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Shah, J.; Shah, R.; Shah, P.; Harimoorthy, V.; Choudhury, N.; Tulsiani, S. A study on optimization of plasma pool size for viral infectious markers in Indian blood donors using nucleic acid amplification testing. Asian J. Transfus. Sci. 2012, 6, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, B.S.W.; Tran, T.; Druce, J.; Ballard, S.A.; Simpson, J.A.; Catton, M. Sample pooling is a viable strategy for SARS-CoV-2 detection in low-prevalence settings. Pathology (Phila.) 2020, 52, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, J.; Singh, V.; Pandey, P.; Verma, A.; Sen, M.; Das, A.; Agarwal, J. Evaluation of sample pooling for diagnosis of COVID-19 by real time-PCR: A resource-saving combat strategy. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 1526–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Geng, Z.; Wang, J.; Liuchang, W.; Huang, D.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L. Comparing two sample pooling strategies for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection for efficient screening of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 2805–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Ami, R.; Klochendler, A.; Seidel, M.; Sido, T.; Gurel-Gurevich, O.; Yassour, M.; Meshorer, E.; Benedek, G.; Fogel, I.; Oiknine-Djian, E.; et al. Large-scale implementation of pooled RNA extraction and RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1248–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, K.; Kanta, P.; Ghosh, A.; Prakash, R.C.; Goyal, K.; Singh, M.P. Validation of SARS CoV-2 detection by real-time PCR in matched pooled and deconvoluted clinical samples before and after nucleic acid extraction: a study in tertiary care hospital of North India. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 99, 115206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health, C. for D. and R. Pooled Sample Testing and Screening Testing for COVID-19. FDA 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, E.; Padhi, A.; Khodare, A.; Agarwal, R.; Ramachandran, K.; Mehta, V.; Kilikdar, M.; Dubey, S.; Kumar, G.; Sarin, S.K. Pooled RNA sample reverse transcriptase real time PCR assay for SARS CoV-2 infection: A reliable, faster and economical method. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0236859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacharapluesadee, S.; Kaewpom, T.; Ampoot, W.; Ghai, S.; Khamhang, W.; Worachotsueptrakun, K.; Wanthong, P.; Nopvichai, C.; Supharatpariyakorn, T.; Putcharoen, O.; et al. Evaluating the efficiency of specimen pooling for PCR-based detection of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2193–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target | CI | E | N | Rdrp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 26,82 | 16,75 | 17,85 | 19,32 |

| SD | 1,17 | 1,21 | 0,80 | 0,50 |

| CV | 0,04 | 0,07 | 0,04 | 0,03 |

| Median | 27,58 | 16,31 | 17,44 | 19,20 |

| Max | 27,71 | 18,29 | 19,14 | 20,12 |

| Min | 25,29 | 15,42 | 17,17 | 18,79 |

| (n) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Targets | Fluorescence (Reporter dye) |

|---|---|

| Rdrp | FAM (C21H12O7) |

| N | JOE (C27H17Cl2NO11) |

| E | Texas Red (C31H29ClN2O6S2) |

| CI | Cy5 (C32H39CN2O2) |

| BIGFISH | BIOER | |

|---|---|---|

| CI Gene | 29/ 30 | 30/ 30 |

| E Gene | 29/ 30 | 22/30 |

| N Gene | 30/30 | 27/30 |

| Rdrp Gene | 30/30 | 26/30 |

| Positive rate | 29/30 (96.67%) | 26/30 (86,67%) |

| Negative rate | 0/30 (0%) | 2/30 (6,67%) |

| Invalids | 1/30 (3,33%) | 2/ 30 (6,67%) |

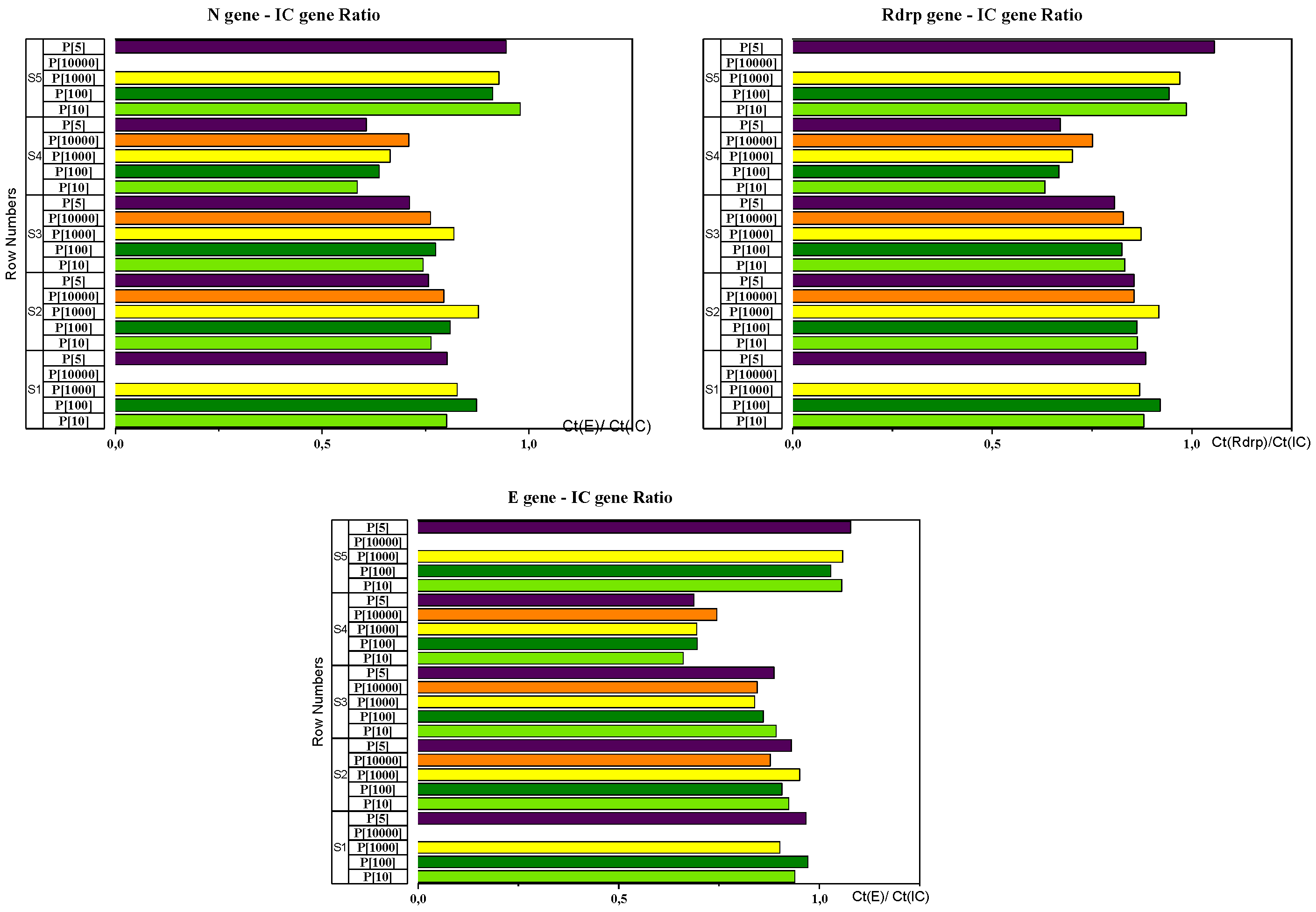

| CT (gène E) /CT(CI) Ratio | CT (gène N) /CT(CI) Ratio | CT (gène Rdrp) /CT(CI) Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | CV | Mean | CV | Mean | CV | |

| Sample 1 | 0,944 | 0,034 | 0,826 | 0,041 | 0,888 | 0,025 |

| Sample 2 | 0,918 | 0,030 | 0,800 | 0,061 | 0,871 | 0,030 |

| Sample 3 | 0,865 | 0,028 | 0,762 | 0,052 | 0,833 | 0,029 |

| Sample 4 | 0,696 | 0,044 | 0,640 | 0,076 | 0,684 | 0,065 |

| Sample 5 | 1,055 | 0,019 | 0,928 | 0,041 | 0,985 | 0,043 |

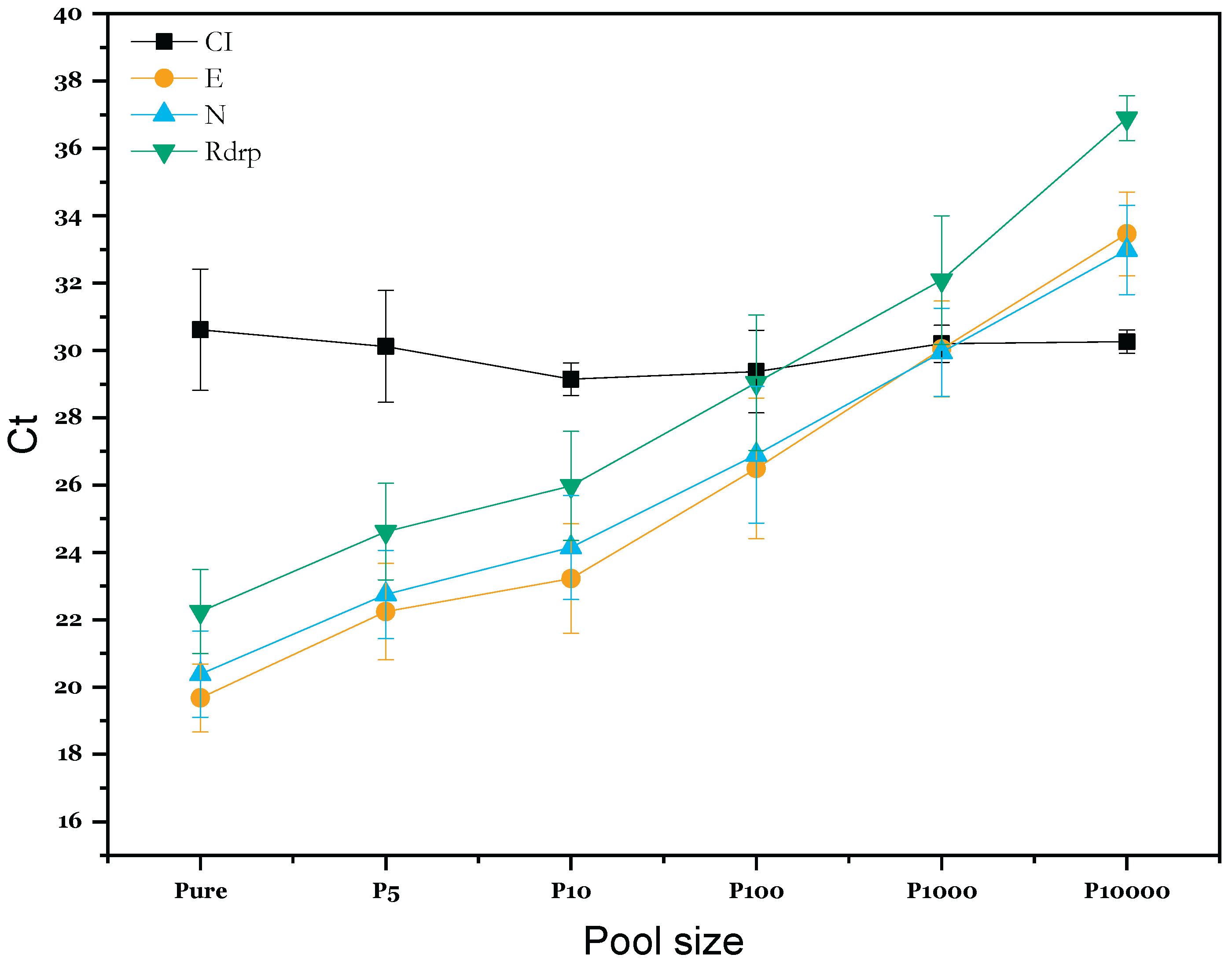

| P-Value | ||||

| Compared Pool strategies | CI | E | N | Rdrp |

| P100 - P10 | 1.000 | 0.1394 | 0.2336 | 0.2166 |

| P1000 - P10 | 0.892 | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | 0.0014 ** |

| P10000 - P10 | 0.868 | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| P5 - P10 | 0.919 | 0.9685 | 0.8474 | 0.8971 |

| Pure - P10 | 0.679 | 0.0911 | 0.0450 * | 0.0825 |

| P1000 - P100 | 0.957 | 0.0911 | 0.1524 | 0.2194 |

| P10000 - P100 | 0.943 | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| P5 - P100 | 0.972 | 0.0279 * | 0.0218 * | 0.0275 * |

| Pure - P100 | 0.805 | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| P10000 - P1000 | 1.000 | 0.1504 | 0.1546 | 0.0420 * |

| P5 - P1000 | 1.000 | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| Pure - P1000 | 0.998 | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| P5 - P10000 | 1.000 | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| Pure - P10000 | 0.999 | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| Pure - P5 | 0.996 | 0.3546 | 0.3861 | 0.4707 |

| Prevalence % | Pool of 3 samples | Pool of 4 samples | Pool of 5 samples | Pool of 10 samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of PCR tests | Economy | Number of PCR tests | Economy | Number of PCR tests | Economy | Number of PCR tests | Economy | |

| 0,1 | 350 | 65% | 260 | 74% | 210 | 79% | 120 | 88% |

| 0,2 | 350 | 65% | 270 | 73% | 220 | 78% | 130 | 87% |

| 0,5 | 360 | 64% | 280 | 72% | 230 | 77% | 160 | 84% |

| 1 | 370 | 63% | 300 | 70% | 260 | 74% | 200 | 80% |

| 2 | 400 | 60% | 330 | 67% | 300 | 70% | 280 | 72% |

| 5 | 480 | 52% | 430 | 57% | 420 | 58% | 490 | 51% |

| 8 | 550 | 45% | 530 | 47% | 530 | 47% | 640 | 36% |

| 10 | 600 | 40% | 580 | 42% | 590 | 41% | 720 | 28% |

| 15 | 710 | 29% | 710 | 29% | 730 | 27% | 860 | 14% |

| 20 | 800 | 20% | 810 | 19% | 840 | 16% | 950 | 5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).