Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and in essence naturally available DESs (NADESs) are considered to be green solvents due to their low vapor pressure, non-flammability, thermal stability, good solvent power and low oxicity. These properties make them attractive as safer and more environmentally acceptable solvent options. Green Chemistry promotes the use of renewable and biocompatible compounds such as amino acids, lipids and acids of natural origin to yield more sustainable DESs, which yields their application in several industrial processes. Driven by the current requisite for sustainable progress, along with overcoming dependence on fossil-based resources, the current work details important findings pertaining to the design of sustainable NADESs from the perspective of green chemistry to exhibit suitable physico-chemical properties and a low toxicological profile. Biodegradation studies using OECD 301D closed bottle test (CBT) were performed to observe the biodegradability of 15 selected NADESs. Toxicity controls were run along with the CBT run to observe the behavior of these NADESs in the environment. In this framework, the present paper investigates the development of safer NADESs. The results obtained suggest that our synthesized NADESs, have high biodegradability and low toxicity towards microalgae. Although a conventional threat to the environment would seem out of reach, it must be hypothesized that such compounds might act as enhancers of eutrophication phenomena.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

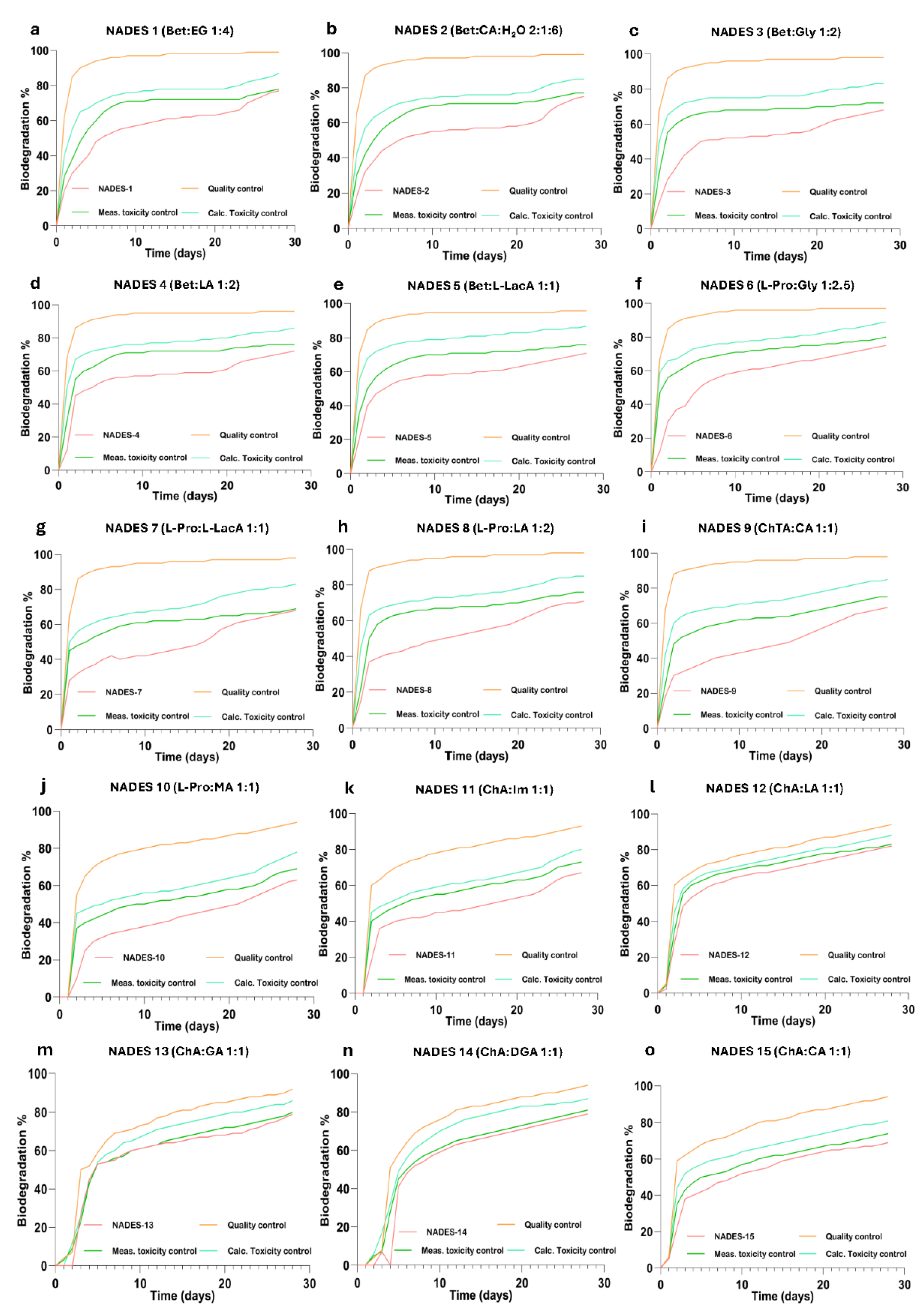

2.1. Biodegradation Results of NADESs

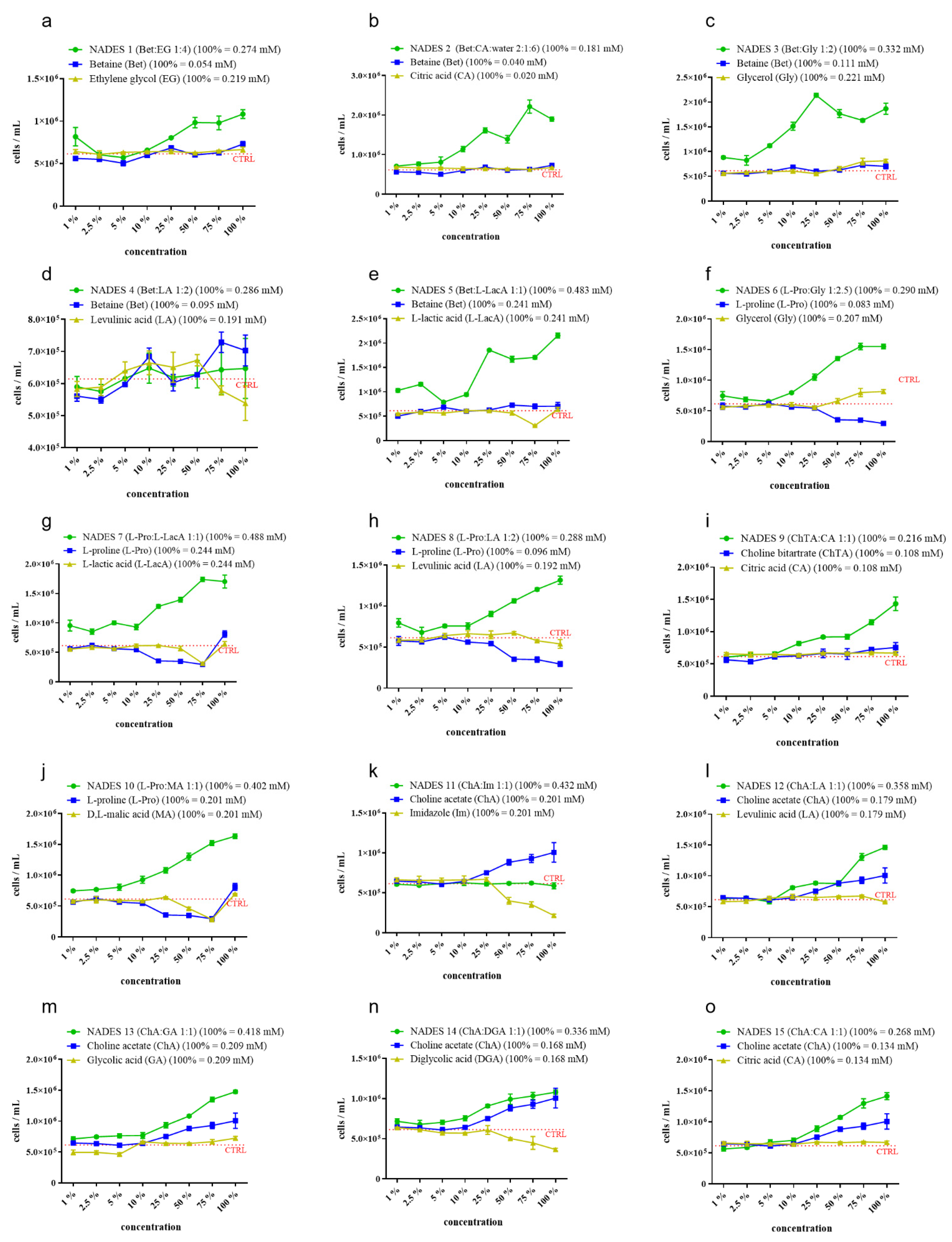

2.2. Raphidocelis subcapitata Growth Bioassay

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Biodegradability Assessment

4.3. Ecotoxicity Assessment

4.4. Naturally Available Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES)

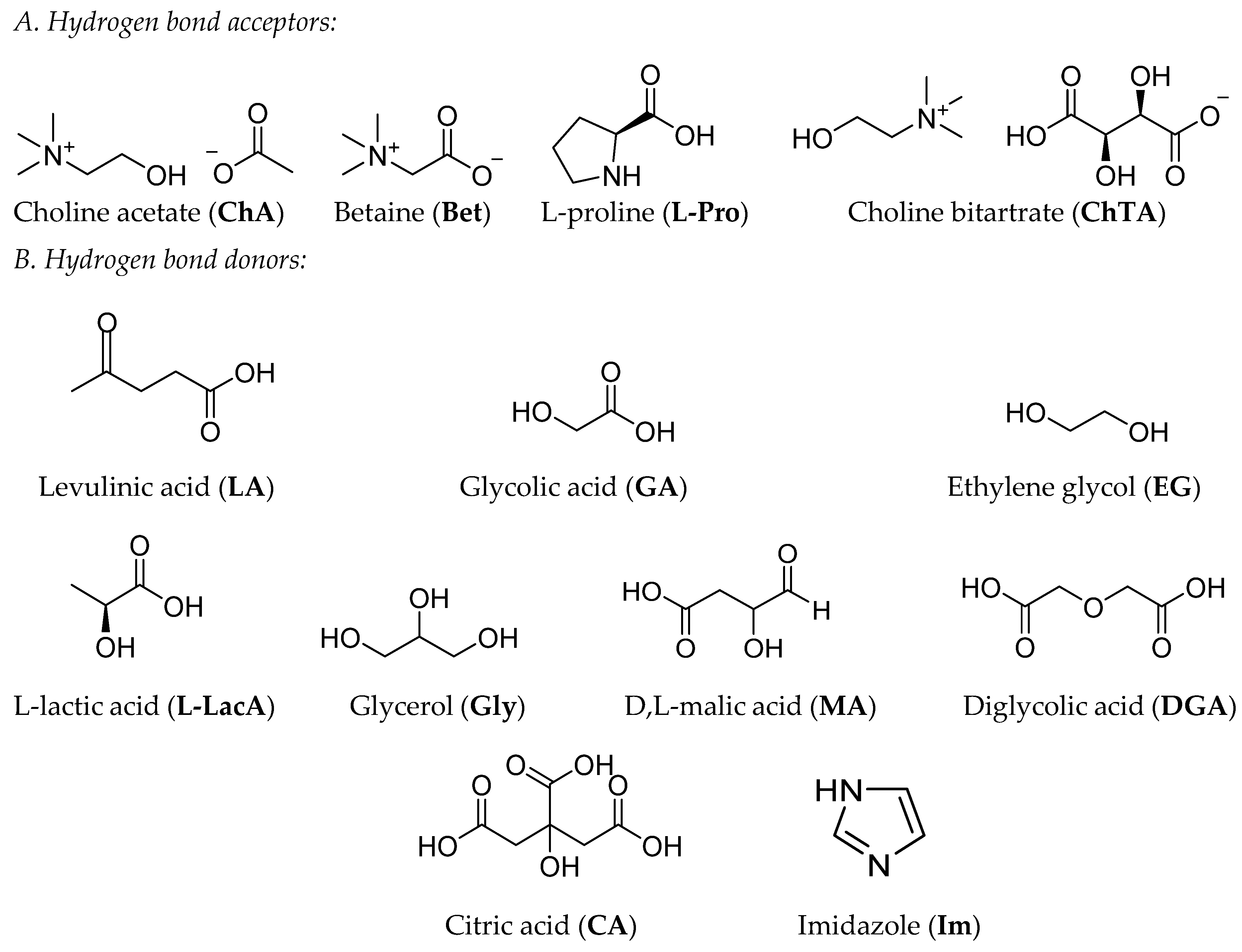

4.5. HBAs and HBDs

4.6. Raphidocelis subcapitata Growth Bioassay

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Declaration: of competing interest

References

- Hessel, V.; Tran, N.N.; Asrami, M.R.; Tran, Q.D.; Van Duc Long, N.; Escribà-Gelonch, M.; Tejada, J.O.; Linke, S.; Sundmacher, K. Sustainability of Green Solvents – Review and Perspective. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 410–437. [CrossRef]

- Winterton, N. The Green Solvent: A Critical Perspective. Clean Technol Environ Policy 2021, 23, 2499–2522. [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, J.; Albericio, F.; de la Torre, B.G. N , N -Dimethyl Formamide European Restriction Demands Solvent Substitution in Research and Development. ChemSusChem 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Wei, C.; Jiang, J. A Review of Designable Deep Eutectic Solvents for Green Fabrication of Advanced Functional Materials. RSC Sustainability 2025, 3, 738–756. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; De Oliveira Vigier, K.; Royer, S.; Jérôme, F. Deep Eutectic Solvents: Syntheses, Properties and Applications. Chem Soc Rev 2012, 41, 7108. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem Rev 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.R.; Pinho, S.P.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Insights into the Nature of Eutectic and Deep Eutectic Mixtures. J Solution Chem 2019, 48, 962–982. [CrossRef]

- Afonso, J.; Mezzetta, A.; Marrucho, I.M.; Guazzelli, L. History Repeats Itself Again: Will the Mistakes of the Past for ILs Be Repeated for DESs? From Being Considered Ionic Liquids to Becoming Their Alternative: The Unbalanced Turn of Deep Eutectic Solvents. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 59–105. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, V.; Geller, D.; Malberg, F.; Sánchez, P.B.; Padua, A.; Kirchner, B. Strong Microheterogeneity in Novel Deep Eutectic Solvents. ChemPhysChem 2019, 20, 1786–1792. [CrossRef]

- Mero, A.; Koutsoumpos, S.; Giannios, P.; Stavrakas, I.; Moutzouris, K.; Mezzetta, A.; Guazzelli, L. Comparison of Physicochemical and Thermal Properties of Choline Chloride and Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: The Influence of Hydrogen Bond Acceptor and Hydrogen Bond Donor Nature and Their Molar Ratios. J Mol Liq 2023, 377, 121563. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; van Spronsen, J.; Dai, Y.; Verberne, M.; Hollmann, F.; Arends, I.W.C.E.; Witkamp, G.J.; Verpoorte, R. Are Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents the Missing Link in Understanding Cellular Metabolism and Physiology? Plant Physiol 2011, 156, 1701–1705. [CrossRef]

- Vieira Sanches, M.; Freitas, R.; Oliva, M.; Mero, A.; De Marchi, L.; Cuccaro, A.; Fumagalli, G.; Mezzetta, A.; Colombo Dugoni, G.; Ferro, M.; et al. Are Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents Always a Sustainable Option? A Bioassay-Based Study. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 17268–17279. [CrossRef]

- Usmani, Z.; Sharma, M.; Tripathi, M.; Lukk, T.; Karpichev, Y.; Gathergood, N.; Singh, B.N.; Thakur, V.K.; Tabatabaei, M.; Gupta, V.K. Biobased Natural Deep Eutectic System as Versatile Solvents: Structure, Interaction and Advanced Applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163002. [CrossRef]

- Azouz, H.H.; Hayyan, M. Preservation of Biological Systems and Materials Using Deep Eutectic Solvents: Pinnacles and Pitfalls. Sep Purif Technol 2025, 135584. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Chen, J.X.; Tang, Y.L.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Assessing the Toxicity and Biodegradability of Deep Eutectic Solvents. Chemosphere 2015, 132, 63–69. [CrossRef]

- Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M.A.; Al-Saadi, M.A.; Hayyan, A.; AlNashef, I.M.; Mirghani, M.E.S. Assessment of Cytotoxicity and Toxicity for Phosphonium-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 455–459. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Han, X.; Liu, Z.; Yu, D.; Guo, W.; Mu, T. Capture of Toxic Gases by Deep Eutectic Solvents. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2020, 8, 5410–5430. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mu, T. Application of Deep Eutectic Solvents in Biomass Pretreatment and Conversion. Green Energy & Environment 2019, 4, 95–115. [CrossRef]

- Mero, A.; Mezzetta, A.; De Leo, M.; Braca, A.; Guazzelli, L. Sustainable Valorization of Cherry ( Prunus Avium L.) Pomace Waste via the Combined Use of (NA)DESs and Bio-ILs. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 6109–6123. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Tong, J.; Guo, Y.; Bi, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, D. Environmental Science Water Research & Technology Novel Reed + Deep Eutectic Solvent-Derived Adsorbents for Recyclable and Low-Cost Capture of Dyes and Radioactive Iodine from Wastewater. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol 2022, 8, 2411. [CrossRef]

- Chabib, C.M.; Ali, J.K.; Jaoude, M.A.; Alhseinat, E.; Adeyemi, I.A.; Al Nashef, I.M. Application of Deep Eutectic Solvents in Water Treatment Processes: A Review. J Water Process Eng 2022, 47. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Xue, Z.; Mu, T. Deep Eutectic Solvents as a Green Toolbox for Synthesis. Cell Rep Phys Sci 2022, 3, 100809. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, J.; Shan, S.; Cao, Y. High Toxicity of Amino Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. J Mol Liq 2023, 370, 121044. [CrossRef]

- Khorsandi, M.; Shekaari, H.; Mokhtarpour, M.; Hamishehkar, H. Cytotoxicity of Some Choline-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Effect on Solubility of Coumarin Drug. Eur J Pharm Sci 2021, 167, 106022. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Juan, E.; López, S.; Abia, R.; J. G. Muriana, F.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.; García-Borrego, A. Antimicrobial Activity on Phytopathogenic Bacteria and Yeast, Cytotoxicity and Solubilizing Capacity of Deep Eutectic Solvents. J Mol Liq 2021, 337, 116343. [CrossRef]

- Garralaga, M.P.; Lomba, L.; Leal-Duaso, A.; Gracia-Barberán, S.; Pires, E.; Giner, B. Ecotoxicological Study of Bio-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents Formed by Glycerol Derivatives in Two Aquatic Biomodels †. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lapeña, D.; Errazquin, D.; Lomba, L.; Lafuente, C.; Giner, B. Ecotoxicity and Biodegradability of Pure and Aqueous Mixtures of Deep Eutectic Solvents: Glyceline, Ethaline, and Reline. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 8812–8821. [CrossRef]

- De Morais, P.; Gonçalves, F.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Ventura, S.P.M. Ecotoxicity of Cholinium-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2015, 3, 3398–3404. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.J.; Meneses, L.; Paiva, A.; Diniz, M.; Duarte, A.R.C. Assessment of Deep Eutectic Solvents Toxicity in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Chemosphere 2022, 299, 134415. [CrossRef]

- Brett, C.M.A. Perspectives for the Use of Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Preparation of Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors. Curr Opin Electrochem 2024, 45, 101465. [CrossRef]

- Juneidi, I.; Hayyan, M.; Ali, M.; Ab, H. Evaluation of Toxicity and Biodegradability for Cholinium-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 83636. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Boothby, D.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K. Deep Eutectic Solvents Formed between Choline Chloride and Carboxylic Acids: Versatile Alternatives to Ionic Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 9142. [CrossRef]

- Nejrotti, S.; Antenucci, A.; Pontremoli, C.; Gontrani, L.; Barbero, N.; Carbone, M.; Bonomo, M. Critical Assessment of the Sustainability of Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Case Study on Six Choline Chloride-Based Mixtures. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 47449–47461. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.S.; Lobo, H.R.; Shankarling, G.S. Choline Chloride Based Eutectic Solvents: Magical Catalytic System for Carbon–Carbon Bond Formation in the Rapid Synthesis of β-Hydroxy Functionalized Derivatives. Catal Commun 2012, 24, 70–74. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Cao, J.; Wang, N.; Su, E. Significantly Improving the Solubility of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Deep Eutectic Solvents for Potential Non-Aqueous Liquid Administration. Medchemcomm 2016, 7, 955–959. [CrossRef]

- Zdanowicz, M.; Jędrzejewski, R.; Pilawka, R. Deep Eutectic Solvents as Simultaneous Plasticizing and Crosslinking Agents for Starch. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 129, 1040–1046. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lei, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Novel Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvent Coupled with In-Situ-Ultrasound Synergistic Extraction of Flavonoids from Epimedium Wushanense: Machine Learning, Mechanistic Investigation, and Antioxidant Activity. Ultrason Sonochem 2025, 121, 107547. [CrossRef]

- Guglielmero, L.; Mero, A.; Koutsoumpos, S.; Kripotou, S.; Moutzouris, K.; Guazzelli, L.; Mezzetta, A. Choline Acetate-, L-Carnitine- and L-Proline-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Comparison of Their Physicochemical and Thermal Properties in Relation to the Nature and Molar Ratios of HBAs and HBDs. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 8625. [CrossRef]

- Sernaglia, M.; Rivera, N.; Bartolomé, M.; Fernández-González, A.; González, R.; Viesca, J.L. Tribological Behavior of Two Novel Choline Acetate-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. J Mol Liq 2024, 414, 126102. [CrossRef]

- Mangiacapre, E.; Barhoumi, Z.; Brehm, M.; Castiglione, F.; Di Lisio, V.; Triolo, A.; Russina, O. Choline Acetate/Water Mixtures: Physicochemical Properties and Structural Organization. Molecules 2025, 30, 3403. [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, M.E.; Tortora, M.; Bottari, C.; Colombo Dugoni, G.; Pivato, R.V.; Rossi, B.; Paolantoni, M.; Mele, A. In Competition for Water: Hydrated Choline Chloride:Urea vs Choline Acetate:Urea Deep Eutectic Solvents. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2021, 9, 12262–12273. [CrossRef]

- Colombo Dugoni, G.; Mezzetta, A.; Guazzelli, L.; Chiappe, C.; Ferro, M.; Mele, A. Purification of Kraft Cellulose under Mild Conditions Using Choline Acetate Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Green Chem 2020, 22, 8680–8691. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; De Oliveira Vigier, K.; Royer, S.S.; Franc¸ois, F.; Je´roˆme, J.J. Deep Eutectic Solvents: Syntheses, Properties and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2012, 41, 7108–7146. [CrossRef]

- Abranches, D.O.; Silva, L.P.; R Martins, M.A.; Pinho, S.P.; P Coutinho, J.A.; Abranches, D.O.; Silva, L.P.; R Martins, M.A.; P Coutinho, J.A.; Pinho, S.P. Understanding the Formation of Deep Eutectic Solvents: Betaine as a Universal Hydrogen Bond Acceptor. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4916–4921. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.J.; Paiva, A.; Diniz, M.; Duarte, A.R. Uncovering Biodegradability and Biocompatibility of Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Systems. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 40218–40229. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.A.; Cardeira, M.; Leonardo, I.C.; Gaspar, F.B.; Radojčić Redovniković, I.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Paiva, A.; Matias, A.A. Deep Eutectic Systems from Betaine and Polyols – Physicochemical and Toxicological Properties. J Mol Liq 2021, 335, 116201. [CrossRef]

- Benlebna, M.; Ruesgas-Ramón, M.; Bonafos, B.; Fouret, G.; Casas, F.; Coudray, C.; Durand, E.; Cruz Figueroa-Espinoza, M.; Feillet-Coudray, C. Toxicity of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Betaine:Glycerol in Rats. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 6205–6212. [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, K.; Wysokowski, M.; Galiński, M. Synthesis and Characterization of Betaine-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for Electrochemical Application. J Mol Liq 2025, 424, 127071. [CrossRef]

- Jangir, A.K.; Bhawna; Verma, G.; Pandey, S.; Kuperkar, K. Design and Thermophysical Characterization of Betaine Hydrochloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents as a New Platform for CO 2 Capture. New J Chem 2022, 46, 5332–5345. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Rubio, C.; Rafikova, K.; Mutelet, F. Desulfurization and Denitrogenation Using Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. J Chem Eng Data 2024, 69, 2244–2254. [CrossRef]

- Cysewski, P.; Jeliński, T.; Przybyłek, M. Exploration of the Solubility Hyperspace of Selected Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients in Choline- and Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: Machine Learning Modeling and Experimental Validation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4894. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-M.; Niu, H.-Y.; Xue, M.-X.; Guo, Q.-X.; Cun, L.-F.; Mi, A.-Q.; Jiang, Y.-Z.; Wang, J.-J. L-Proline in an Ionic Liquid as an Efficient and Reusable Catalyst for Direct Asymmetric a-Aminoxylation of Aldehydes and Ketones. Green Chem., 2006, 8, 682-684. [CrossRef]

- Obregón-Zúñiga, A.; Milán, M.; Juaristi, E. Improving the Catalytic Performance of (S)-Proline as Organocatalyst in Asymmetric Aldol Reactions in the Presence of Solvate Ionic Liquids: Involvement of a Supramolecular Aggregate. Org Lett 2017, 19, 1108–1111. [CrossRef]

- Nica Fernández-Stefanuto, V.; Corchero, R.; Rodríguez-Escontrela, I.; Soto, A.; Tojo, E. Ionic Liquids Derived from Proline: Application as Surfactants., ChemPhysChem, 2018, 19, 2885. [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Wang, M.; Shan, W.; Deng, C.; Ren, W.; Shi, Z.; Lü, H. L-Proline-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) for Deep Catalytic Oxidative Desulfurization (ODS) of Diesel. J Hazard Mater 2017, 339, 216–222. [CrossRef]

- Giri, C.; Karadendrou, M.-A.; Kostopoulou, I.; Kakokefalou, V.; Tzani, A.; Detsi, A. L-Proline-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as Efficient Solvents and Catalysts for the Ultrasound-Assisted Synthesis of Aurones via Knoevenagel Condensation. Catalysts 2022, 12(3), 249. [CrossRef]

- Vachan, B.S.; Karuppasamy, M.; Vinoth, P.; Vivek Kumar, S.; Perumal, S.; Sridharan, V.; Menéndez, J.C. Proline and Its Derivatives as Organocatalysts for Multi- Component Reactions in Aqueous Media: Synergic Pathways to the Green Synthesis of Heterocycles. Adv Synth Catal 2020, 362, 87–110.

- Zárate-Roldán, S.; Trujillo-Rodríguez, M.J.; Gimeno, M.C.; Herrera, R.P. L-Proline-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents as Green and Enantioselective Organocatalyst/Media for Aldol Reaction. J Mol Liq 2024, 396, 123971. [CrossRef]

- Assessment of Chemicals | OECD Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/assessment-of-chemicals.html (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Levain, A.; Barthélémy, C.; Bourblanc, M.; Douguet, J.M.; Euzen, A.; Souchon, Y. Green Out of the Blue, or How (Not) to Deal with Overfed Oceans: An Analytical Review of Coastal Eutrophication and Social Conflict. Environment and Society: Advances in Research 2020, 11, 115–142. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Hilt, S.; Shi, P.; Cheng, H.; Feng, M.; Pan, M.; Guo, Y.; et al. Heat Waves Rather than Continuous Warming Exacerbate Impacts of Nutrient Loading and Herbicides on Aquatic Ecosystems. Environ Int 2022, 168, 107478. [CrossRef]

- Silbiger, N.J.; Nelson, C.E.; Remple, K.; Sevilla, J.K.; Quinlan, Z.A.; Putnam, H.M.; Fox, M.D.; Donahue, M.J. Nutrient Pollution Disrupts Key Ecosystem Functions on Coral Reefs. Proc R Soc B: Bio Sci 2018, 285. [CrossRef]

- Leavitt, P.R.; Findlay, D.L.; Hall, R.I.; Smol, J.P. Algal Responses to Dissolved Organic Carbon Loss and PH Decline during Whole-Lake Acidification: Evidence from Paleolimnology. Limnol Oceanogr 1999, 44, 757–773. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, D.S.,; Whittington, J.,; Oliver, R., Temporal Variability of Dissolved P Speciation in a Eutrophic Reservoir—Implications for Predicating Algal Growth. Water Res 2003, 37(19), 4595-4598.

- Zhao, B.Y.; Xu, P.; Yang, F.X.; Wu, H.; Zong, M.H.; Lou, W.Y. Biocompatible Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Choline Chloride: Characterization and Application to the Extraction of Rutin from Sophora Japonica. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2015, 3, 2746–2755. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Friesen, J.B.; Mcalpine, J.B.; Lankin, D.C.; Chen, S.-N.; Pauli, G.F. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: Properties, Applications, and Perspectives. J Nat Prod 2018, 81 (3), 679–690. [CrossRef]

- Glibert, P.; Seitzinger, S.; Heil, C.; Burkholder, J.; Parrow, M.; Codispoti, L.; Kelly, V. The Role of Eutrophication in the Global Proliferation of Harmful Algal Blooms. Oceanography 2005, 18, 198–209. [CrossRef]

- Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M.A.; Al-Saadi, M.A.; Hayyan, A.; AlNashef, I.M.; Mirghani, M.E.S. Assessment of Cytotoxicity and Toxicity for Phosphonium-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 455–459. [CrossRef]

- Colombo Dugoni, G.; Mezzetta, A.; Guazzelli, L.; Chiappe, C.; Ferro, M.; Mele, A. Purification of Kraft Cellulose under Mild Conditions Using Choline Acetate Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Green Chem 2020, 22, 8680–8691. [CrossRef]

- Nyholm, N. The European System of Standardized Legal Tests for Assessing the Biodegradability of Chemicals. Environ Toxicol Chem 1991, 10, 1237–1246. [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Test Guidelines for Chemicals 1992.

- Friedrich, J.; Längin, A.; Kümmerer, K. Comparison of an Electrochemical and Luminescence-Based Oxygen Measuring System for Use in the Biodegradability Testing According to Closed Bottle Test (OECD 301D). Clean (Weinh) 2013, 41, 251–257. [CrossRef]

- Kitano, M. Updating of OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals. Water Sci Technol 1992, 25, 465–472. [CrossRef]

- ASTM E1218-21. Standard Guide for Conducting Static Toxicity Tests with Microalgae 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).