1. Introduction

The world is facing interconnected pressures arising from rapid population growth, increasing urbanisation, rising energy demand, and growing water insecurity. Global primary energy consumption has continued to increase over recent decades and is projected to rise further as developing economies expand and standards of living improve (Dodangodage, Premarathne, et al., 2025)(Mishra et al., 2021). Simultaneously, freshwater resources are under increasing stress due to climate change, pollution, and inefficient use in agriculture and industry, with water scarcity emerging as a critical global risk (Ingrao et al., 2023)(Bănăduc et al., 2022). Addressing these coupled challenges requires integrated solutions that enhance resource efficiency while minimising environmental impacts.

Liquid biofuels such as bioethanol have been promoted as renewable alternatives to fossil-derived transport fuels; however, many first- and second-generation bioethanol production pathways rely heavily on food crops and resource-intensive agricultural practices. Large-scale ethanol production from corn, sugarcane, or other terrestrial feedstocks competes for arable land, increases freshwater consumption, and can contribute to food price volatility and indirect land-use change (Hirani et al., 2018)(Moonsamy et al., 2022). These limitations have driven increasing interest in third-generation biofuel feedstocks that avoid food–fuel competition by utilising non-food biomass, marginal resources, and low-quality water within circular bioeconomy frameworks (Sadaqat et al., 2025)(John et al., 2025)(de Abreu et al., 2025)

Microalgae have emerged as promising third-generation feedstocks for bioethanol and other biofuels due to their rapid growth rates, high areal productivity, and ability to accumulate substantial quantities of carbohydrates under suitable cultivation conditions(Sadaqat et al., 2025)(Sachin Powar et al., 2022). Among various species, Chlorella sp. is particularly attractive because of its robustness, tolerance to a wide range of environmental conditions, and proven capacity to synthesise carbohydrate-rich biomass that can be hydrolysed into fermentable sugars (Mendes et al., 2024)(Olguín et al., 2022). In addition to biofuel production, microalgal cultivation offers multiple co-benefits, including nutrient recovery from wastewater, carbon dioxide sequestration, and the generation of value-added coproducts that can improve overall process economics (Dodangodage, Kasturiarachchi, et al., 2025a)(Geng et al., 2025)

Despite these advantages, the economic and environmental viability of algal biofuel pathways is strongly influenced by the choice of growth medium and the extent to which cultivation can be integrated into existing nutrient and water streams. The use of wastewater or effluents as culture media has been widely reported as an effective strategy to reduce production costs, minimise freshwater demand, and enhance sustainability through nutrient recycling(Dodangodage, Kasturiarachchi, et al., 2025b) (Slade & Bauen, 2013)(Herrera et al., 2021). However, most existing studies have focused on municipal wastewater, industrial effluents, or conventional aquaculture waters in isolation. In contrast, the potential of aquaponics-derived effluents—particularly the clarified overflow from sedimentation or clarifier units—remains insufficiently explored as a nutrient source for carbohydrate-oriented algal biomass production (Bhuyar et al., 2021)(Hossain et al., 2019)(Sydney et al., 2019)(Walls et al., 2019).

Aquaponics integrates recirculating aquaculture with hydroponic plant cultivation, creating a resource-efficient food production system in which fish waste-derived nutrients support plant growth while plants improve water quality for fish (Dodangodage, Kasturiarachchi, et al., 2025a)(Luz et al., 2025)(Palm et al., 2024). To maintain system performance, aquaponic operations typically employ solids removal and clarification processes that generate a continuous stream of clarified, nutrient-rich effluent. This sedimentation effluent is characterised by elevated concentrations of dissolved nitrogen and phosphorus, reduced suspended solids, and the presence of trace minerals, making it a potentially suitable medium for microalgal cultivation(Dodangodage, Kasturiarachchi, et al., 2025a) (Tetreault et al., 2021). Yet, this stream is often underutilised and discharged with limited valorisation.

Utilising clarified aquaponic sedimentation effluent for microalgae cultivation offers several advantages. First, it reduces freshwater consumption by substituting clean water with a recycled effluent stream. Second, it enables the recovery of dissolved nutrients by converting them into algal biomass that can serve as a feedstock for biofuels or other bioproducts. Third, integration of microalgae into aquaponic systems can enhance overall system resilience by further polishing effluents and reducing nutrient discharge to the environment(Dodangodage, Kasturiarachchi, et al., 2025a)(Mahmood et al., 2023)(Farooq, 2021) . Despite these potential benefits, critical questions remain regarding biomass productivity, carbohydrate accumulation, and biomass quality when Chlorella sp. is cultivated in clarified aquaponic effluents compared with conventional synthetic media.

Carbohydrate content is a key determinant of microalgal biomass suitability for bioethanol production, as fermentable sugar yield after saccharification directly governs theoretical ethanol output. Although carbohydrate accumulation can be enhanced through nutrient limitation, light manipulation, or stress induction, most evidence to date is derived from studies using synthetic media or well-characterised wastewaters (Osman et al., 2023)(Tse et al., 2021)(Condor et al., 2022). Empirical data on the carbohydrate response of Chlorella sp. to the specific nutrient composition and organic matter profile of clarified aquaponic sedimentation effluent remain scarce, particularly with respect to total carbohydrate fraction and bioethanol-relevant productivity metrics.

Moreover, the composition of aquaponic effluents varies with fish species, feeding regimes, system design, and solids removal efficiency, which may significantly influence algal growth kinetics and biochemical composition. Consequently, experimental evaluation using real effluent streams under controlled cultivation conditions is necessary to assess both biomass productivity and carbohydrate accumulation before large-scale or integrated bioethanol production can be realistically proposed(Dodangodage, Kasturiarachchi, et al., 2025a)(Kushwaha et al., 2025).

In this context, the present study investigates the feasibility of producing carbohydrate-rich Chlorella sp. biomass using clarified effluent from aquaponic sedimentation tanks. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first studies to evaluate clarified aquaponic sedimentation effluent effluent as a cultivation medium specifically for carbohydrate-oriented Chlorella sp. biomass production targeted at bioethanol feedstock applications. The study quantifies biomass productivity, assesses carbohydrate accumulation as a percentage of dry weight, and evaluates the theoretical bioethanol potential of the produced biomass. By focusing on a real aquaponics-derived nutrient stream, this work provides practical insights into resource recovery strategies for integrated food–energy–water systems and contributes data essential for future techno-economic and life-cycle assessments of algal bioethanol pathways.

The specific objectives of this study are: (i) to characterise the nutrient composition of clarified aquaponic sedimentation effluent used as a culture medium; (ii) to evaluate the growth kinetics and biomass productivity of Chlorella sp. cultivated in this effluent under controlled laboratory conditions; and (iii) to quantify carbohydrate accumulation in the harvested biomass and assess its suitability as a fermentable feedstock for bioethanol production.

2. Method

2.1. Wastewater Collection and Pre-treatment

Aquaponics Sedimentation Effluent was collected from the Aquaponics facility of the University of Moratuwa in sterile polyethylene containers, transported on ice, and processed within 24 h. Suspended solids were removed by filtration through a 0.45 µm nylon mesh (Millipore), and the clarified wastewater was used as the experimental medium. Preliminary screening experiments were conducted to determine optimal dilution and illumination conditions for Chlorella sp. cultivation. Based on these results, a 100% (v/v) without dilution of wastewater was selected, with pH adjusted to 6.8 using 1 M NaOH. BG11 medium (HiMedia, India) served as the control. Both media were sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min.

2.2. Wastewater Characterization

Initial characterization of Aquaponics Sedimentation Effluent was performed according to APHA Standard Methods (Fitri et al., 2020). All measurements were conducted in triplicate (n = 3). The following parameters were determined:

pH – using a benchtop pH meter.

Nitrate (NO₃⁻–N) – UV absorbance at 220 nm with baseline correction at 275 nm.

Phosphate (PO₄³⁻–P) – molybdenum blue method, absorbance at 880 nm.

The characterized wastewater parameters were compared against national discharge standards (Central Environmental Authority, Sri Lanka, 2022). Nitrate (8–12 mg L⁻¹) and phosphate (5–7 mg L⁻¹) concentrations also surpassed thresholds for secondary-treated effluent (NO₃⁻ ≤ 5 mg L⁻¹; PO₄³⁻ ≤ 2 mg L⁻¹). These findings confirmed the necessity of nutrient remediation prior to discharge.

2.3. Microalgal Strain and Inoculum Preparation

A pure culture of Chlorella sp. was obtained from Progreen Laboratory, University of Moratuwa. Pre-cultures were grown in standard nitrate concentration (BBM) medium under controlled conditions (25 ± 2 °C, continuous illumination at 150 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ with cool-white LED lights, and aeration at 0.5 vvm sterile-filtered air) before being transferred to experimental flasks. Explorational phase cultures were harvested, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 min, and inoculated into experimental media at an initial biomass concentration of 0.3 g L⁻¹. 2 L laboratory glass bottles containing 1.5 L of autoclave sterilized media, inclusive of 3-port GL45 screw caps with openings for aeration and pressure compensation were employed as the photobioreactors. Aeration and pressure compensation ports were equipped with 0.45 µm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane filters for sterile aeration and reduction of evaporative losses. The photobioreactors were illuminated with cool white LED strips at 10, 000 lux light intensity under a 12/12 h light/dark cycle(Premaratne et al., 2021).

2.4. Experimental Setup and Cultivation Conditions

2.4.1. Screening of Wastewater Dilution Factors

Four dilutions of Aquaponics Sedimentation Effluent (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% v/v) were prepared using distilled water, with 400 mL working volume in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. Initial pH (<3.9) was adjusted to 6.8 using NaOH. BBM medium (400 mL) served as the control. Cultures were incubated at 32 °C under a 12:12 h light–dark cycle, aerated continuously, and illuminated at 100 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ (LED, cool-white). Biomass growth was monitored every 48 h by optical density (OD₆8₀) and dry weight measurement(Reyimu & Özçimen, 2017).

2.4.2. Screening of Light Intensities

The effect of light intensity on biomass production was evaluated using the Aquaponics Sedimentation Effluent medium. Four light intensities (90, 140, 185, and 230 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹, LED, cool-white) were tested, with BBM at 100 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ as the control. Cultures were incubated under the same conditions as

Section 3.4.1. Biomass accumulation was monitored every 48 h(Azizi et al., 2021).

2.4.3. Main Cultivation Experiment

Based on the screening results, the undiluted (100% v/v) Aquaponics Sedimentation Effluent was selected for subsequent experiments as it supported high biomass accumulation without freshwater consumption. Similarly, the light intensity screening indicated that 185 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ supported the optimal growth trade-off, and this intensity was selected for the main experiment.

The main batch cultivation was carried out in 2 L sterilized glass vessels with 1.5 L working volume, using the selected undiluted (100% v/v) aquaponics sedimentation effluent and BBM control. Cultures were incubated at 32 °C under a 12:12 h light–dark photoperiod, aerated with sterile-filtered air pumps (BOYO, 0.45 µm filter), and illuminated with LED lights at 185 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹. Light intensity was monitored with a quantum sensor (LI-COR LI-250A). The BBM control was cultivated under the same optimized illumination conditions (185 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹) to ensure comparability

2.5. Analytical Procedures

2.5.1. Biomass Concentration

Biomass growth was monitored every 48 h. Optical density (OD₆8₀) was measured with a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800). Microalgal growth was evaluated at 2-day time intervals by the determination of biomass concentration of cultures. Culture aliquots of 5 mL were filtered through pre-dried and pre-weighed glass microfiber filter papers (Hyundai GF/C, ϕ47 mm, 1.2 µm pore size)(Premaratne et al., 2021). Thereafter, the glass microfiber filter papers were oven dried at 60 °C for 24 h, and the biomass concentration of cultures was determined as per the following equation

where DWn is the biomass concentration (g/L) of microalgae on the nth day of cultivation (Tn), Wf is the final weight of the dried filters with microalgal biomass, Wi is the initial weight of the filters and V is the volume of the culture aliquot.

2.5.2. Nutrient Removal

The nitrate concentration in the media and pH of cultures were determined at 2-day time intervals. Culture samples (5mL) were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 5min and the supernatant was filtered through 0.22µm nylon syringe filters. (Hanna HI98194)(Rita & Bragança, 2021). Nitrate and phosphate concentrations were determined as in

Section 2.2.

Nutrient removal efficiency (RE, %) was calculated as:

where (Ci) and (Cf) are initial and final concentrations (mg L⁻¹), respectively.

2.5.3. Analytical Validation

All analyses were performed in triplicate. UV–Vis measurements were calibrated with standard solutions (potassium nitrate, KH₂PO₄, and potassium hydrogen phthalate). Calibration curves showed excellent linearity (R² ≥ 0.996). Instrumental blanks were run for each batch to eliminate baseline drift.

2.6. Biomass Harvesting

At the end of the 20-day cultivation period, biomass was harvested by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 20 min (Eppendorf 5810R), washed twice with sterile distilled water, and oven-dried at 60 °C to constant weight(Dodangodage, Kasturiarachchi, et al., 2025b).

2.7. Carbohydrate Content

10mg samples were also utilized for the determination of carbohydrate content. 0.5mL of acetic acid was added to microalgal biomass, and the solution was heated at 80°C for 20min in a temperature- controlled water bath. The solution was cooled, and 10mL of acetone was added for the extraction of pigments. Thereafter, the samples were centrifuged at 3500×g for 10min, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was hydrolyzed by incubation with 2.5mL of 4M trifluoroacetic acid at 95°C for 4h. The hydrolysate was separated from the residual biomass by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 5min. The carbohydrate content in the hydrolysate was determined using the phenol-sulfuric acid method(Jia et al., 2015)(Dubois et al., 1956).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All screening experiments were conducted in duplicate, while the main cultivation experiments and all analytical measurements were performed in triplicate (n = 3). Statistical significance of media dilution and light intensity was evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test, with significance defined at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Aquaponics Wastewater

Prior to inoculation, the physicochemical properties of the sedimentational aquaponics effluent (AE) were analyzed to assess its suitability as a growth medium. The initial composition of the wastewater (Day 0) revealed a nutrient-rich profile characteristic of intensive aquaculture systems.

As summarized in

Table 1, the wastewater was slightly acidic to neutral with a pH of 6.81 ± 0.33, which is within the optimal physiological range for

Chlorella sp. Notably, the wastewater contained a high concentration of nitrate (153.02 ± 4.26 mg/L), exceeding the nitrate concentration found in the standard Bold's Basal Medium (BBM) control (142.40 ± 2.98 mg/L). However, the phosphate concentration in the wastewater (6.91 ± 0.25 mg/L) was significantly lower than that of the control medium (13.76 ± 0.60 mg/L). This resulted in a high N:P ratio in the wastewater (22 : 1), suggesting that phosphorus could potentially become the limiting nutrient during prolonged cultivation.

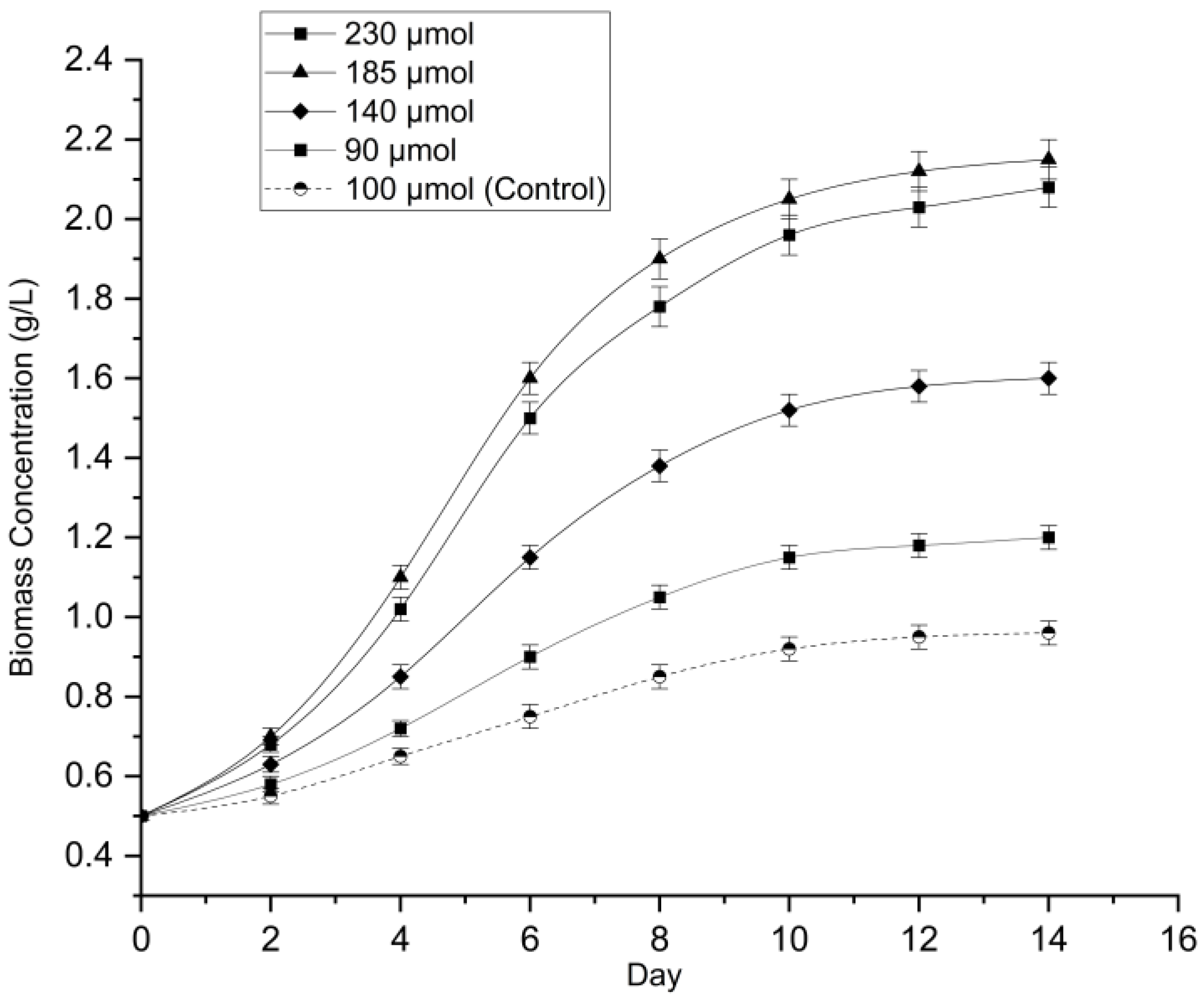

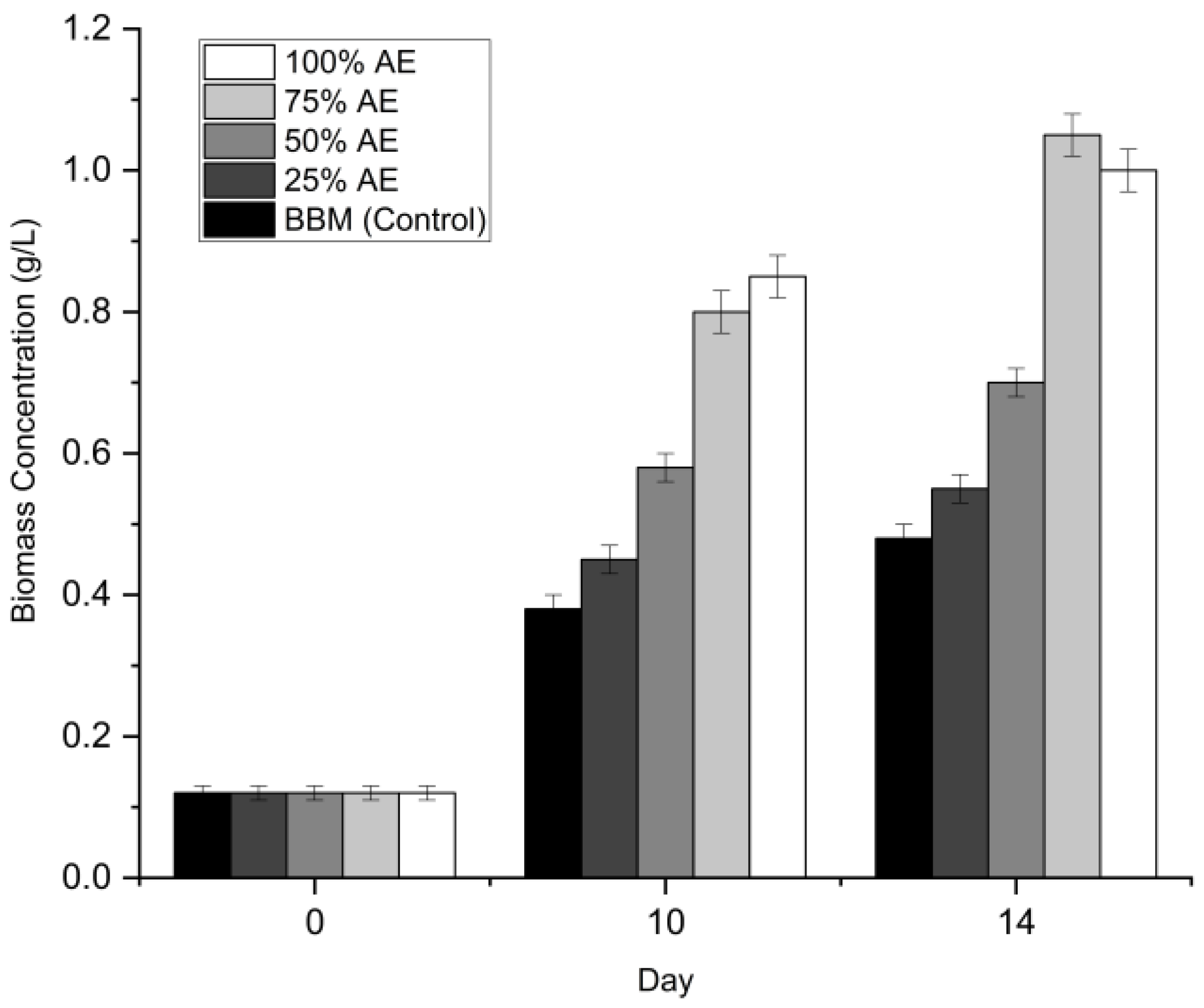

3.2. Screening of Optimal Aquaponics Effluent (AE) Dilution

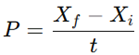

The growth of Chlorella sp. was evaluated under five different dilution regimes (0% to 100% Aquaponics Effluent AE) to identify the optimal nutrient concentration for biomass production. The growth profiles in terms of optical density (OD₆₈₀) and dry cell weight (DCW) are presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

3.2.1. Growth Dynamics (OD₆₈₀)

The cultures grown in higher concentrations of wastewater (75% and 100% AE) exhibited rapid exponential growth compared to the control (BBM) and lower dilutions. A one-way ANOVA analysis confirmed that the dilution factor had a statistically significant effect on growth (p < 0.001). By Day 12, the highest optical densities were recorded in 100% AE (2.20 ± 0.03) and 75% AE (2.18 ± 0.05). A Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test revealed that there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the 75% and 100% concentrations, though both were significantly superior to the BBM control (1.11 ± 0.04).

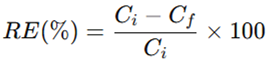

3.2.2. Biomass Production (Dry Weight)

While the optical density suggested equal performance between the two highest concentrations, the dry weight analysis revealed a significant divergence. As shown in

Figure 2, the maximum biomass yield was achieved in 75% AE (1.08 ± 0.02 g/L) on Day 12. Statistical analysis indicated that the biomass yield in 75% AE was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that obtained under the 100% AE condition (0.97 ± 0.02 g L⁻¹). However, the absolute difference in biomass accumulation between the two treatments was marginal (<10%), indicating that Chlorella sp. can maintain comparable growth performance even under undiluted aquaponics effluent. Although the 100% AE condition may have introduced mild growth constraints, such as increased self-shading or nutrient imbalance, its ability to support high biomass productivity without the use of freshwater is particularly relevant from a sustainability perspective. Therefore, in alignment with resource-efficiency principles and Sustainable Development Goals related to water conservation and circular resource use, the undiluted (100% v/v) aquaponics effluent was selected as the optimal medium for subsequent light-intensity optimization experiments. Although the 75% dilution yielded marginally higher biomass, the 100% condition eliminates the need for freshwater addition, significantly lowering the operational water footprint. In a circular bioeconomy context, eliminating freshwater input is prioritized over marginal yield gains.

3.3. Optimization of Light Intensity for Biomass Production

Following the determination of the optimal dilution factor, the influence of light intensity on

Chlorella sp. growth was evaluated under five photosynthetic photon flux densities (PPFD) ranging from 90 to 230 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹. The growth dynamics, measured via optical density (OD₆₈₀), exhibited a significant non-linear response to light availability (

Figure 3).

A one-way ANOVA confirmed that light intensity had a statistically significant effect on the growth rate (p < 0.001). The cultures exposed to higher intensities (185 and 230 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹) demonstrated rapid exponential growth, achieving the highest final optical densities of 2.15 ± 0.05 and 2.08 ± 0.05, respectively. Interestingly, the lowest light intensity (90 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹) recorded a higher optical density (1.20 ± 0.03) compared to the control at 100 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ (0.96 ± 0.03), suggesting a potential physiological response to low-light stress through increased pigmentation.

However, the dry cell weight (DCW) analysis provided a more definitive measure of productivity and revealed distinct saturation kinetics (

Figure 4). Unlike the optical density results, the biomass yield at 90 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ (0.48 ± 0.02 g/L) was significantly lower than the control (0.55 ± 0.02 g/L;

p < 0.05), confirming that light limitation constrained actual biomass accumulation despite the higher turbidity. The biomass yield increased consistently with light intensity, peaking at 1.05 ± 0.03 g/L under 185 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹. A Tukey’s HSD post-hoc analysis revealed no significant difference (

p > 0.05) between the yields at 185 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ and 230 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ (1.00 ± 0.03 g/L). This plateau indicates that the culture reached photo-saturation at 185 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹, where further increases in light energy did not translate into additional biomass. Consequently, 185 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ was identified as the optimal illumination intensity for the subsequent main experiment.

3.4. Results: Growth Kinetics and Biomass Productivity

The cultivation of Chlorella sp. under the optimized conditions (100% Aquaponics Effluent (AE) + 185 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹) was compared against a control group grown in standard BBM. The results demonstrate that the waste-derived medium supported significantly higher growth rates and biomass accumulation than the commercial nutrient solution.

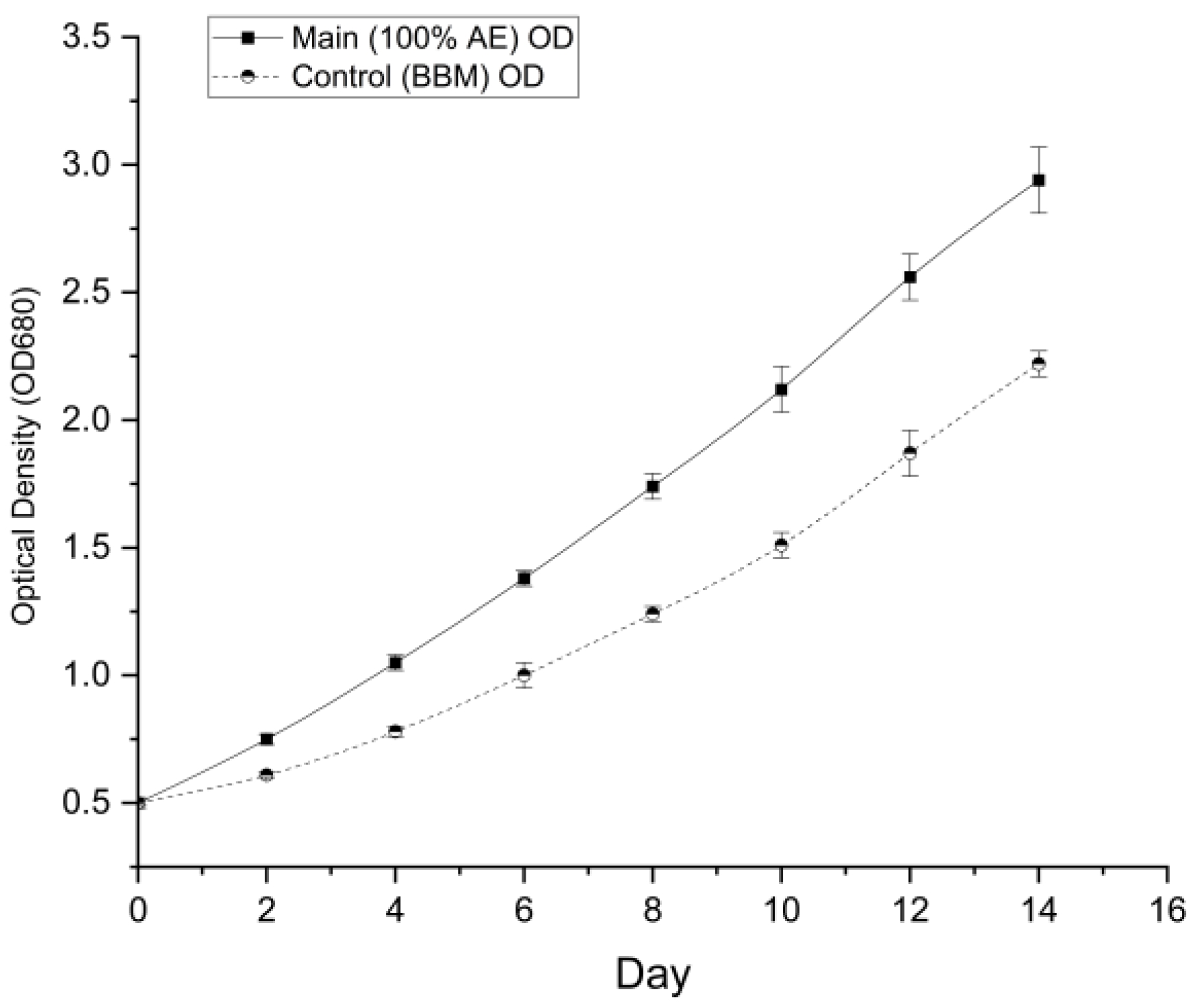

3.4.1. Growth Dynamics

The optical density profile (

Figure 5) reveals that the optimized wastewater culture entered the exponential phase earlier and maintained a higher growth trajectory throughout the 14-day period. By Day 14, the optical density of the main experimental group reached 2.94 ± 0.13, which was significantly higher (

p < 0.001, t-test) than the control group (2.22 ± 0.05).

Specific Growth Rate (μ): The specific growth rate during the exponential phase (Days 2–10) was calculated to be 0.130 d⁻¹ for the wastewater group, compared to 0.113 d⁻¹ for the control.

Doubling Time (tₙ): Consequently, the cells in the aquaponics wastewater doubled faster (tₙ = 5.34 days) than those in the standard medium (tₙ = 6.12 days).

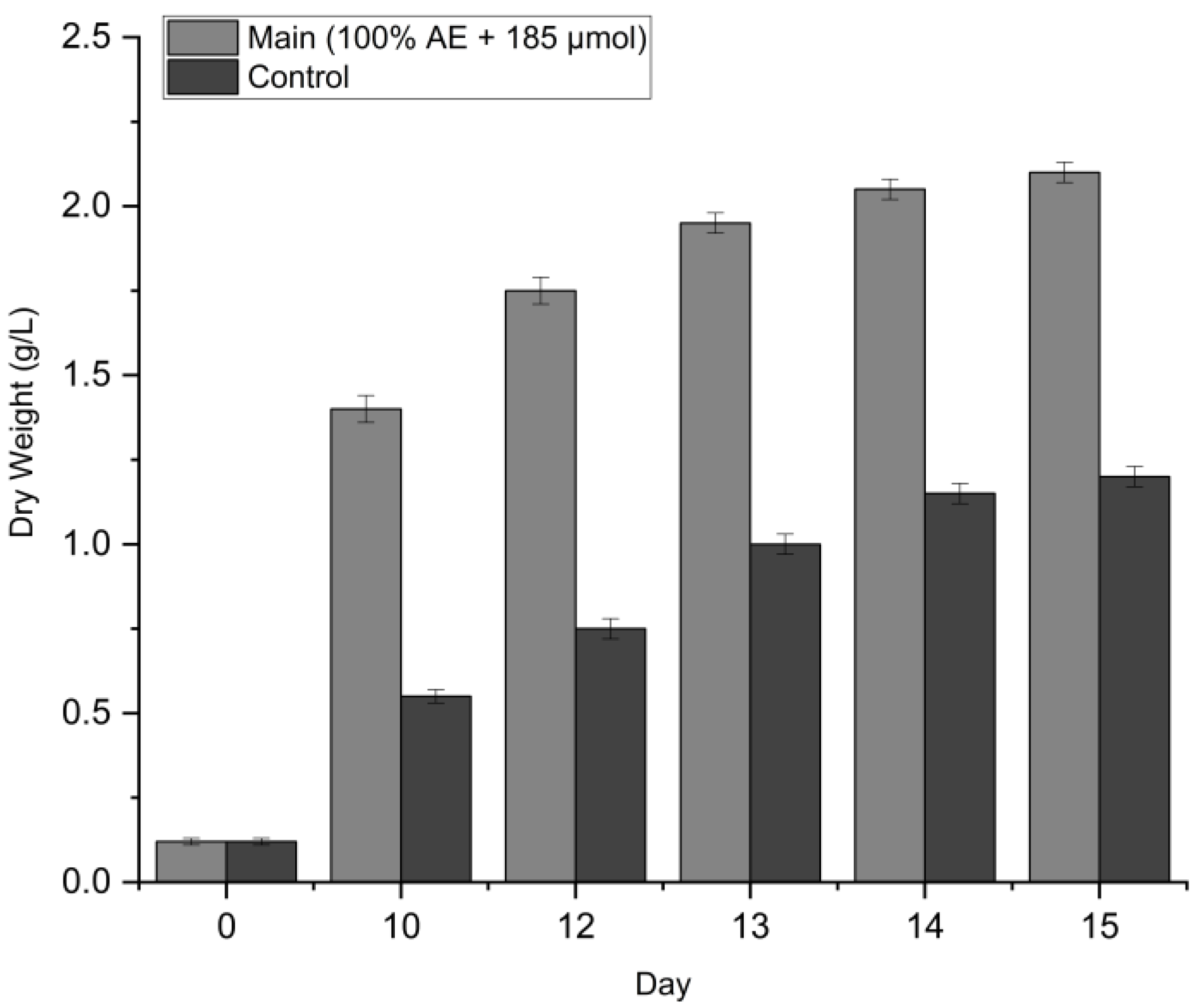

3.4.2. Biomass Productivity

The superiority of the aquaponics effluent (AE) was most evident in the dry biomass yield (

Figure 6). While both cultures started with an initial biomass of 0.12 ± 0.01 g/L, the optimized group diverged sharply after Day 10. By the end of the cultivation period (Day 15), the main experiment achieved a maximum biomass of 2.05 ± 0.03 g/L, representing a 75% increase over the control (1.20 ± 0.03 g/L,

p < 0.001).

When it comes to productivity (Pₘₐₓ)(Vivanco-Bercovich et al., 2025), the overall biomass productivity for the optimized system was 0.132 g/L/day, nearly double that of the control (0.072 g/L/day). This confirms that aquaponics wastewater, when paired with optimized lighting, provides a nutrient-dense environment that outperforms standard inorganic media.

3.5. Results: Nutrient Removal Efficiency

To evaluate the bioremediation potential of the system, the depletion of nitrate (NO₃⁻) and phosphate (PO₄³⁻) was monitored throughout the cultivation period. The results confirm that Chlorella sp. is highly effective at recovering nutrients from aquaponics wastewater.

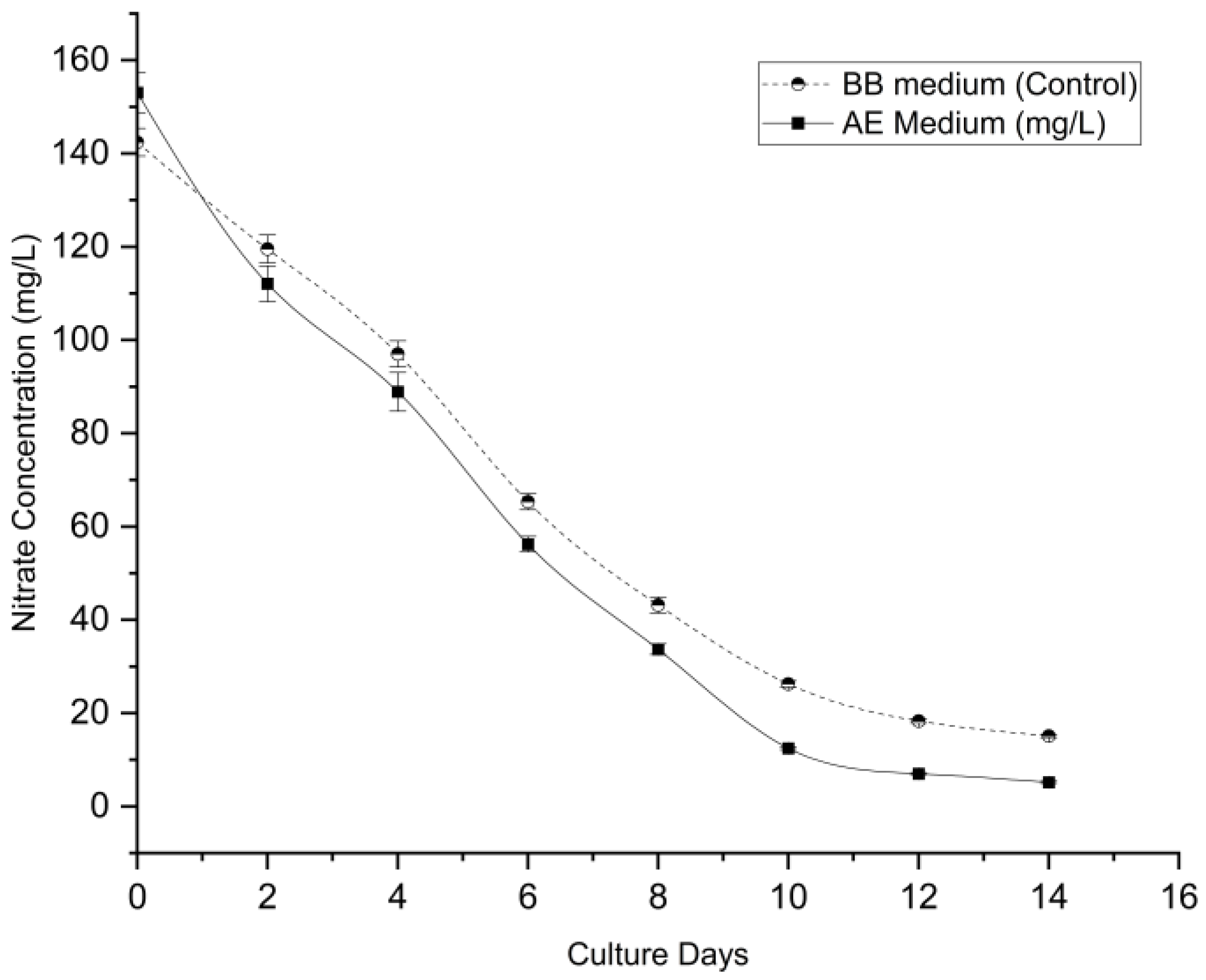

3.5.1. Nitrate Removal

The system demonstrated high nitrate removal kinetics (

Figure 7). The aquaponics wastewater initially contained higher nitrate loads (153.02 ± 4.26 mg/L) compared to the BBM control (142.40 ± 2.98 mg/L). Despite this higher initial burden, the optimized culture achieved a significantly faster removal rate of 10.56 mg/L/day, compared to 9.09 mg/L/day in the control. By Day 14, the nitrate concentration in the AE was reduced to just 5.20 ± 0.22 mg/L, corresponding to a removal efficiency of 96.60%. This was significantly higher (p < 0.001) than the 89.39% efficiency observed in the control group.

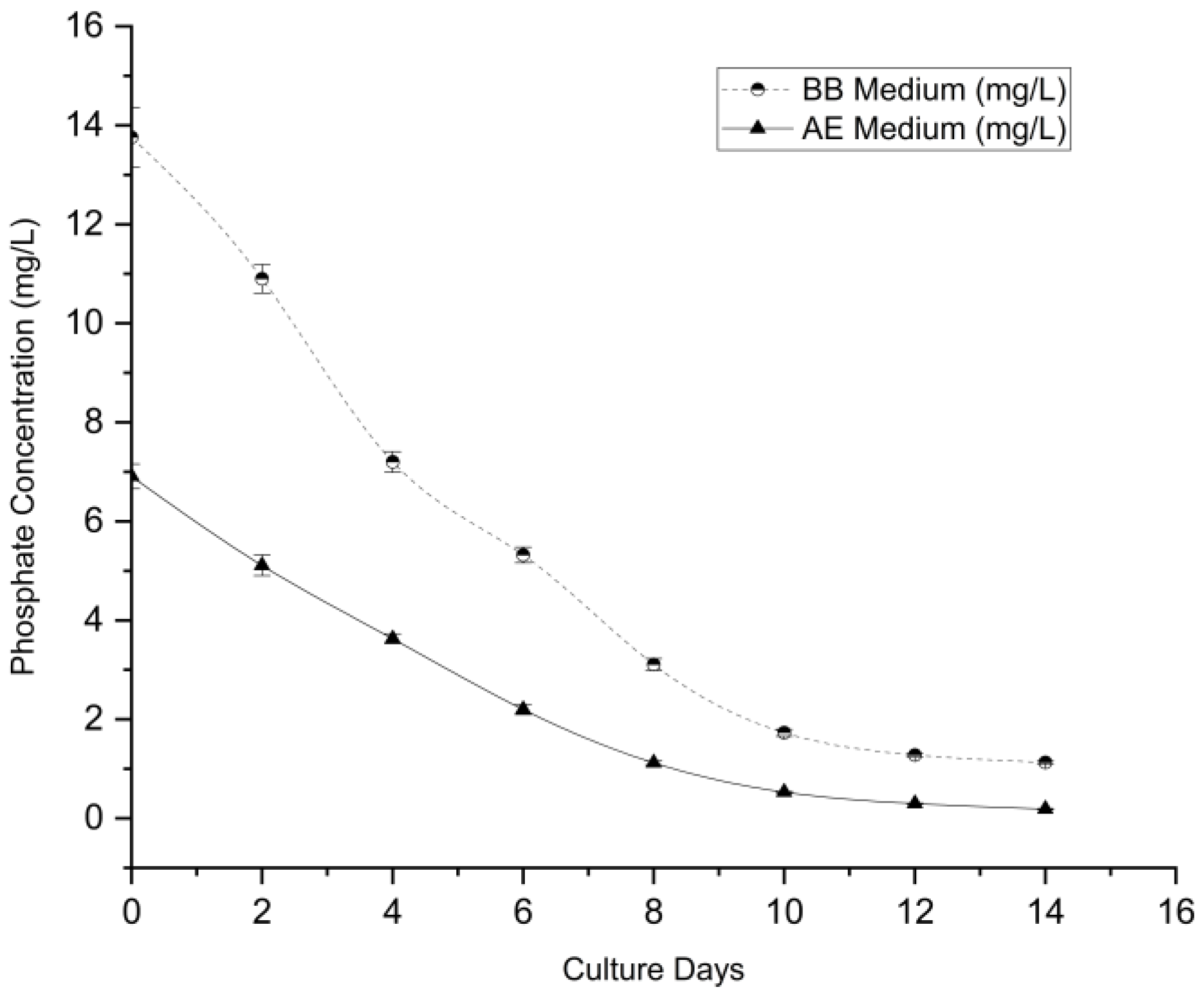

3.5.2. Phosphate Removal

Phosphate removal followed a similar trend of rapid depletion (

Figure 8). Although the initial phosphate concentration in the wastewater (6.91 ± 0.25 mg/L) was approximately half of the BBM control (13.76 ± 0.60 mg/L), the culture scavenged the available phosphorus to near-exhaustion. By Day 14, the residual phosphate in the wastewater dropped to 0.19 ± 0.01 mg/L, representing a 97.25% removal efficiency. This complete depletion suggests that the system is capable of polishing wastewater effluent to meet stringent discharge standards.

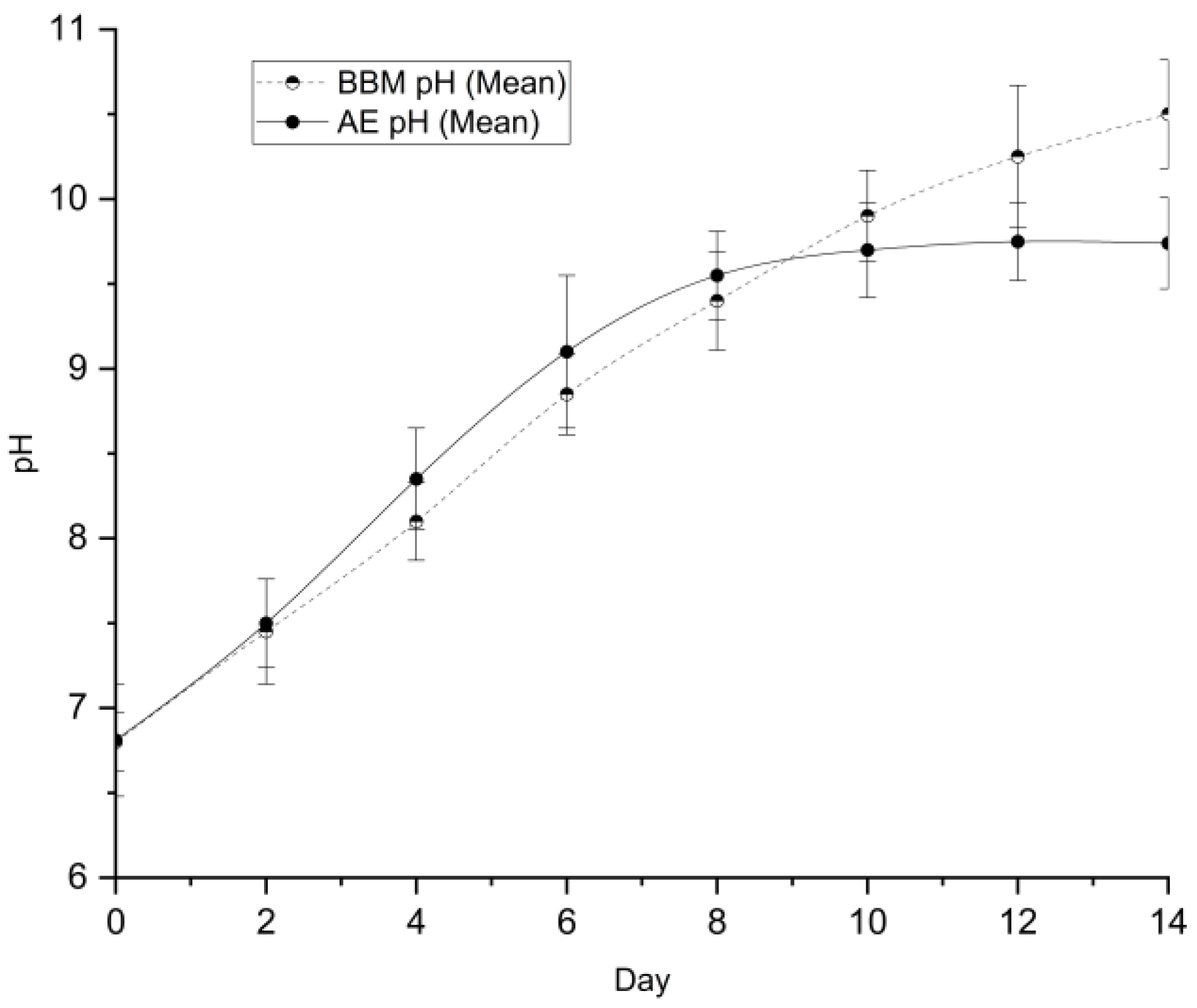

3.5.3. pH Evolution

The pH profile (

Figure 9) provided insight into the photosynthetic activity of the cultures. Both groups exhibited a pH increase over time, indicative of dissolved CO₂ consumption during photosynthesis.

Control (BBM), the pH rose continuously, reaching a highly alkaline peak of 10.50 by Day 14. AE the pH rose initially but stabilized at approximately 9.75 after Day 10. This stabilization in the wastewater group is advantageous for large-scale cultivation, as extreme alkalinity (pH > 10) can sometimes precipitate essential micronutrients or inhibit growth. The natural buffering capacity of the aquaponics effluent likely contributed to maintaining this more favorable range.

Consequently, the total nutrient removal efficiency was calculated to quantify the treatment performance (

Table 2). The aquaponics wastewater medium demonstrated superior bioremediation capacity, achieving significantly higher removal rates (p < 0.05) for both nitrate (96.59%) and phosphate (97.25%) compared to the control. This high efficiency suggests that the system effectively mitigates the risk of eutrophication while generating biomass.

3.7. Biomass Accumulation and Carbohydrate Productivity

To assess the potential of the produced biomass as a feedstock for bioethanol, the dry cell weight (DCW), carbohydrate content (%), and total carbohydrate yield were analyzed after 14 days of cultivation.

3.7.1. Enhanced Biomass and Carbohydrate Profile

The biochemical analysis (

Table 3) confirms that aquaponics effluent (AE) significantly enhances both cell growth and energy storage compared to the standard BBM control.

The biomass consistent with the growth kinetics observed in

Section 3.4, the final dry cell weight reached 2.05 ± 0.03 g/L, representing a 78.3% increase over the control yield of 1.15 ± 0.03 g/L. This superior growth is attributed to the organic carbon and micronutrients present in the fish effluent, which facilitate mixotrophic growth (Chaudhuri & Balasubramanian, 2025).

Decisively, the algal cells grown in wastewater accumulated significantly higher intracellular carbohydrates. The carbohydrate content in the AE group reached 40.71 ± 2.14% of dry weight, a 72.9% increase compared to the control (23.54 ± 2.24%). This accumulation is a stress response to the nitrogen depletion observed towards the end of the cultivation period, a known trigger for starch synthesis in Chlorella sp.

3.7.2. Theoretical Bioethanol Potential

The combination of high biomass and high carbohydrate content resulted in a high in total feedstock availability. The total carbohydrate yield in the AE medium was calculated to be 0.835 g/L, which corresponds to a 208% enhancement compared to the control (0.271 g/L).

Based on the standard stoichiometric conversion factor of 0.511 g ethanol/g hexose, the theoretical bioethanol potential of the AE-grown biomass is approximately 0.427 g/L, compared to just 0.138 g/L for the control. These findings confirm that aquaponics wastewater is a highly feasible, low-cost medium for producing carbohydrate-rich feedstock for biofuel applications(Miskat et al., 2020)(Alfonsín et al., 2019).

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that clarified aquaponics effluent (AE) can serve as an effective nutrient medium for Chlorella sp., supporting significantly higher biomass productivity than the conventional Bold’s Basal Medium (BBM). The enhanced growth observed under optimized AE conditions is consistent with previous reports indicating that aquaculture- and aquaponics-derived effluents often outperform synthetic media due to the presence of readily assimilable nitrogen species, phosphorus, trace elements, and dissolved organic carbon ((Dall’Osto et al., 2019); (Chaiprapat et al., 2017)). Unlike strictly inorganic formulations, aquaponics effluents may enable partial mixotrophic growth because of their organic carbon fraction, thereby accelerating cell division and biomass accumulation without external carbon supplementation.

The earlier onset of exponential growth and the higher specific growth rate recorded in AE relative to BBM align well with values reported for Chlorella cultivated in fish farm wastewater and aquaculture effluents, where specific growth rates typically range from 0.11 to 0.15 d⁻¹ (Difusa et al., 2015; Dhandwal et al., 2025). The close agreement between these reported values and the present findings suggests that clarified AE provides a nutritionally balanced environment rather than imposing strong inhibitory effects commonly associated with untreated or highly concentrated wastewaters.

The dilution-dependent response observed in this study highlights the importance of balancing nutrient availability and light penetration when cultivating microalgae in real effluents. Although high optical densities were achieved under both 75% and 100% AE conditions, dry biomass accumulation was only marginally higher at the optimized dilution, with the absolute difference between diluted and undiluted media remaining below 10%. This indicates that Chlorella sp. can maintain comparable biomass productivity even under undiluted effluent conditions. The slight reduction in biomass observed at 100% AE is likely attributable to increased self-shading, reduced light penetration, or minor nutrient imbalances, phenomena that have been widely reported for dense algal cultures grown in wastewater matrices (Chaiprapat et al., 2017;Lakatos et al., 2019).

From a system-integration perspective, the ability to cultivate microalgae directly in undiluted aquaponics wastewater is particularly advantageous. Operating without dilution eliminates freshwater demand while preserving high productivity, which is critical for large-scale deployment in water-scarce regions and aligns with resource-efficiency principles emphasized in wastewater-based algal cultivation systems ((Dall’Osto et al., 2019); (Dhandwal et al., 2025)).

Light intensity optimization further revealed a clear photo-saturation response. Biomass productivity increased with irradiance up to approximately 180–190 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ and plateaued thereafter, indicating that photosynthetic capacity became saturated beyond this range. Similar optimal irradiance windows (150–200 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹) have been reported for Chlorella spp. cultivated in wastewater-based systems ((Dall’Osto et al., 2019); (Dhandwal et al., 2025)). At lower irradiance, enhanced pigmentation may elevate optical density without a proportional increase in dry biomass, whereas excessive light does not translate into higher productivity once photosynthetic electron transport becomes limiting.

Beyond biomass production, the high nitrate and phosphate removal efficiencies achieved in AE cultures demonstrate the strong bioremediation capability of Chlorella sp. The near-complete depletion of dissolved nutrients by Day 14 compares favorably with nutrient removal efficiencies reported for microalgae-based treatment of aquaculture effluents, which typically range from 70–95% for nitrate and 80–98% for phosphate ((Difusa et al., 2015); (Chaiprapat et al., 2017)).

The stabilization of pH observed in AE cultures, in contrast to the continuous increase recorded in BBM, suggests an inherent buffering capacity associated with the wastewater matrix. This buffering behavior has been attributed to bicarbonate alkalinity, dissolved organic matter, and the coexistence of multiple nitrogen species in aquaculture-derived effluents ((Dall’Osto et al., 2019)). Similar pH moderation effects have been reported in integrated algae–aquaculture systems, where extreme pH excursions during intense photosynthesis are dampened by the chemical composition of the wastewater. Such pH stability is particularly advantageous for scale-up, as excessive alkalinity can impair micronutrient bioavailability, alter carbon speciation, and compromise long-term culture stability.

A key outcome of this study is the substantial enhancement of carbohydrate accumulation in Chlorella sp. cultivated in AE. The carbohydrate content exceeding 40% of dry weight falls within, and in some cases exceeds, the range reported for carbohydrate-enriched Chlorella biomass produced under nitrogen-limited or wastewater-based conditions (30–45% DW)(Lakatos et al., 2019); (Dall’Osto et al., 2019)). This accumulation is strongly associated with progressive nitrogen depletion during cultivation, which is known to redirect cellular carbon flux away from protein synthesis toward starch and other storage polysaccharides.

When combined with elevated biomass yield, the resulting total carbohydrate productivity significantly exceeded that of the BBM control, translating into a markedly higher theoretical bioethanol potential. Previous studies have emphasized that total carbohydrate yield, rather than percentage content alone, is the critical determinant of bioethanol process feasibility ((Difusa et al., 2015); (Dhandwal et al., 2025)). In this context, the present results underscore the advantage of integrating algal cultivation with aquaponics wastewater streams to maximize both nutrient recovery and biofuel feedstock generation. While bioethanol yields were estimated using stoichiometric conversion factors, experimental fermentation trials were beyond the scope of the present study and should be addressed in future work.

The findings of this study support the integration of microalgae into aquaponic operations as an effective resource recovery strategy. By converting dissolved nutrients into carbohydrate-rich biomass, the system simultaneously mitigates eutrophication risk and generates a valuable bioenergy precursor. Life-cycle and sustainability assessments have consistently highlighted that coupling algal biofuel production with wastewater treatment can substantially reduce freshwater demand, fertilizer inputs, and overall production costs ((Dall’Osto et al., 2019); (Dhandwal et al., 2025)).

Overall, the present work provides experimental evidence that clarified aquaponics sedimentation effluent is not merely a waste stream but a viable cultivation medium for producing carbohydrate-rich

Chlorella sp. biomass. These results establish a robust foundation for future studies focusing on continuous operation, downstream fermentation performance, and integrated techno-economic and life-cycle assessments to evaluate large-scale implementation.

Table 4.

Comparison of carbohydrate-rich Chlorella sp. production in wastewater-based systems reported in the literature and the present study.

Table 4.

Comparison of carbohydrate-rich Chlorella sp. production in wastewater-based systems reported in the literature and the present study.

| Study / Source |

Wastewater Type |

Biomass Yield (g L⁻¹) |

Carbohydrate Content (% DW) |

Key Outcome |

| (Difusa et al., 2015) |

Fish farm wastewater |

0.8–1.4 |

28–38 |

Effective nutrient removal with moderate carbohydrate accumulation |

| (Chaiprapat et al., 2017) |

Aquaculture effluent |

0.9–1.6 |

30–40 |

Improved growth under diluted effluent conditions |

| (Dall’Osto et al., 2019) |

Integrated aquaculture–algae systems |

1.0–2.0 |

35–45 |

Enhanced biofuel feedstock potential through wastewater valorization |

| (Dhandwal et al., 2025) |

Wastewater-grown Chlorella

|

1.2–2.1 |

32–44 |

High carbohydrate productivity coupled with nutrient recovery |

| Present study |

Clarified aquaponics wastewater |

≈2.05 |

≈40.7 |

High biomass yield, strong nutrient removal, and elevated bioethanol potential |

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the technical feasibility of utilizing clarified aquaponics sedimentation effluent as a growth medium for producing carbohydrate-rich Chlorella sp. biomass suitable for bioethanol applications. Undiluted aquaponics effluent supported robust algal growth, achieving a maximum biomass concentration of 2.05 g L⁻¹ under optimized illumination (185 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹), representing a 78% increase compared with the conventional BBM control.

In addition to enhanced biomass productivity, cultivation in aquaponics effluent significantly promoted carbohydrate accumulation, with carbohydrate content reaching 40.7% of dry weight. This resulted in a more than threefold increase in total carbohydrate yield and a corresponding theoretical bioethanol potential of 0.427 g L⁻¹, highlighting the suitability of the produced biomass as a fermentable feedstock.

The system also demonstrated strong wastewater polishing capability, achieving nitrate and phosphate removal efficiencies exceeding 96%, while maintaining a more stable pH profile compared with the synthetic medium. This buffering behaviour is advantageous for operational stability and suggests that aquaponics effluent can support sustained algal cultivation without excessive chemical intervention.

Overall, the findings confirm that clarified aquaponics sedimentation effluent is not merely a waste stream but a valuable resource that can be directly valorised for biofuel feedstock production without freshwater dilution. By integrating microalgal cultivation into aquaponic systems, the approach simultaneously enables nutrient recovery, wastewater treatment, and renewable energy feedstock generation. Future work should focus on continuous cultivation, downstream fermentation validation, and comprehensive techno-economic and life-cycle assessments to support large-scale implementation within integrated food–energy–water systems.

References

- Alfonsín, V.; Maceiras, R.; Gutiérrez, C. Bioethanol production from industrial algae waste. Waste Management 2019, 87, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, S.; Bayat, B.; Tayebati, H.; Hashemi, A.; Pajoum Shariati, F. Nitrate and phosphate removal from treated wastewater by Chlorella vulgaris under various light regimes within membrane flat plate photobioreactor. Environmental Progress and Sustainable Energy 2021, 40(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bănăduc, D.; Simić, V; Cianfaglione, K.; Barinova, S.; Afanasyev, S.; Öktener, A.; McCall, G.; Simić, S.; Curtean-Bănăduc, A. Freshwater as a Sustainable Resource and Generator of Secondary Resources in the 21st Century: Stressors, Threats, Risks, Management and Protection Strategies, and Conservation Approaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(Issue 24). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyar, P.; Trejo, M.; Dussadee, N.; Unpaprom, Y.; Ramaraj, R.; Whangchai, K. Microalgae cultivation in wastewater effluent from tilapia culture pond for enhanced bioethanol production. Water Science and Technology 2021, 84(10–11), 2686–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R.; Balasubramanian, P. Enhancing nutrient removal from hydroponic effluent with simultaneous production of lipid-rich biomass through mixotrophic cultivation of microalgae. Journal of Applied Phycology 2025, 37(2), 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condor, B.E.; de Luna, M.D.G.; Chang, Y.H.; Chen, J.H.; Leong, Y.K.; Chen, P.T.; Chen, C.Y.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Bioethanol production from microalgae biomass at high-solids loadings. Bioresource Technology 2022, 363, 128002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, V.H.S.; da Costa, M.G.; de Assis, T.F.; D’Agosto, M. de A.; Rocha, R.S.; de Paula, L.O.D.; Laissone, A.M.S. Assessing the Feasibility of Enzymatic Biodiesel Production Using the 5W2H Framework: A Brazilian Case Study with Distiller’s Corn Oil. Energies 2025, 18(20). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodangodage, C.A.; Kasturiarachchi, J.; Perera, T.; Rajapakshe, D.; Halwatura, R. Integrated Microalgal-Aquaponic Systems for Enhanced Water Treatment and Food Security: A Critical Review of Recent Advances in Process Integration and Resource Recovery. 2025a. [Google Scholar]

- Dodangodage, C.A.; Kasturiarachchi, J.; Perera, T.; Rajapakshe, D.; Halwatura, R. Valorization of Canteen Wastewater Through Optimized Spirulina platensis Cultivation for Enhanced Carotenoid Production and Nutrient Removal. 2025b. [Google Scholar]

- Dodangodage, C.A.; Premarathne, H.; Kasturiarachchi, J.C.; Perera, T.A.; Rajapakshe, D.; Halwatura, R.U. Algae-Based Protective Coatings for Sustainable Infrastructure: A Novel Framework Linking Material Chemistry, Techno-Economics, and Environmental Functionality. Phycology 2025, 5(4), 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Analytical Chemistry 1956, 28(3), 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, W. Sustainable production of microalgae biomass for biofuel and chemicals through recycling of water and nutrient within the biorefinery context: A review. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13(6), 914–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitri, A.; Abdul Maulud, K.N.; Pratiwi, D.; Phelia, A.; Rossi, F.; Zuhairi, N.Z. Trend Of Water Quality Status In Kelantan River Downstream, Peninsular Malaysia. Jurnal Rekayasa Sipil (JRS-Unand) 2020, 16(3), 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Shaukat, A.; Azhar, W.; Raza, Q.U.A.; Tahir, A.; Abideen, M.Z. ul; Zia, M.A.B.; Bashir, M.A.; Rehim, A. Microalgal biorefineries: a systematic review of technological trade-offs and innovation pathways. In Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts; BioMed Central Ltd, 2025; Volume 18, Issue 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A.; D’Imporzano, G.; Acién Fernandez, F.G.; Adani, F. Sustainable production of microalgae in raceways: Nutrients and water management as key factors influencing environmental impacts. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 287, 125005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirani, A.H.; Javed, N.; Asif, M.; Basu, S.K.; Kumar, A. A Review on First- and Second-Generation Biofuel Productions. In Biofuels: Greenhouse Gas Mitigation and Global Warming: Next Generation Biofuels and Role of Biotechnology; Kumar, A., Ogita, S., Yau, Y.-Y., Eds.; Springer India, 2018; pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.; Zaini, J.; Indra Mahlia, T.M. Life cycle assessment, energy balance and sensitivity analysis of bioethanol production from microalgae in a tropical country. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 115, 109371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrao, C.; Strippoli, R.; Lagioia, G.; Huisingh, D. Water scarcity in agriculture: An overview of causes, impacts and approaches for reducing the risks. In Heliyon; Elsevier Ltd, 2023; Volume 9, Issue 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Han, D.; Gerken, H.G.; Li, Y.; Sommerfeld, M.; Hu, Q.; Xu, J. Molecular mechanisms for photosynthetic carbon partitioning into storage neutral lipids in Nannochloropsis oceanica under nitrogen-depletion conditions. Algal Research 2015, 7, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.U.; Onu, C.E.; Ezechukwu, C.M.-J.; Nwokedi, I.C.; Onyenanu, C.N. Multi-product biorefineries for biofuels and value-added products: advances and future perspectives. Academia Green Energy 2025, 2(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, J.; Priyadarsini, M.; Rani, J.; Pandey, K.P.; Dhoble, A.S. Aquaponic trends, configurations, operational parameters, and microbial dynamics: a concise review. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2025, 27(1), 213–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, T.M.R.; Ushiña, D.; Santos, O.; Ispolnov, K.; Aires, L.M.I.; Sousa, H.P.D.; Bernardino, R.; Vaz, D.; Cotrim, L.; Sebastião, F.; Vieira, J. Wastewater Valorisation in Sustainable Productive Systems: Aquaculture, Urban, and Swine Farm Effluents Hydroponics. Applied Sciences 2025, 15(23), 12695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Hussain, N.; Shahbaz, A.; Mulla, S.I.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Bilal, M. Sustainable production of biofuels from the algae-derived biomass. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering 2023, 46(8), 1077–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.R.; Spínola, M.P.; Lordelo, M.; Prates, J.A.M. Advances in Bioprocess Engineering for Optimising Chlorella vulgaris Fermentation: Biotechnological Innovations and Applications. In Foods; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), 2024; Volume 13, Issue 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.K.; Kumar, P.; Saraswat, C.; Chakraborty, S.; Gautam, A. Water security in a changing environment: Concept, challenges and solutions. Water (Switzerland) 2021, 13(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskat, M.I.; Ahmed, A.; Chowdhury, H.; Chowdhury, T.; Chowdhury, P.; Sait, S.M.; Park, Y.K. Assessing the theoretical prospects of bioethanol production as a biofuel from agricultural residues in bangladesh: A review. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12(Issue 20), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonsamy, T.A.; Mandegari, M.; Farzad, S.; Görgens, J.F. A new insight into integrated first and second-generation bioethanol production from sugarcane. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 188, 115675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olguín, E.J.; Sánchez-Galván, G.; Arias-Olguín, I.I.; Melo, F.J.; González-Portela, R.E.; Cruz, L.; De Philippis, R.; Adessi, A. Microalgae-Based Biorefineries: Challenges and Future Trends to Produce Carbohydrate Enriched Biomass, High-Added Value Products and Bioactive Compounds. Biology 2022, 11(Issue 8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, M.E.H.; Abo-Shady, A.M.; Elshobary, M.E.; Abd El-Ghafar, M.O.; Hanelt, D.; Abomohra, A. Exploring the Prospects of Fermenting/Co-Fermenting Marine Biomass for Enhanced Bioethanol Production. In Fermentation; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), 2023; Vol. 9, Issue 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, H.W.; Knaus, U.; Kotzen, B. Aquaponics nomenclature matters: It is about principles and technologies and not as much about coupling. Reviews in Aquaculture 2024, 16(1), 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premaratne, M.; Liyanaarachchi, V.C.; Nishshanka, G.K.S.H.; Nimarshana, P.H.V.; Ariyadasa, T.U. Nitrogen-limited cultivation of locally isolated Desmodesmus sp. For sequestration of CO2from simulated cement flue gas and generation of feedstock for biofuel production. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyimu, Z.; Özçimen, D. Batch cultivation of marine microalgae Nannochloropsis oculata and Tetraselmis suecica in treated municipal wastewater toward bioethanol production. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 150, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, A.; Bragança, S. Microalgae for the Production of High-Value Compounds: Evaluation of the Effect of Different Nitrogen and Carbon Sources on the Production of Fucoxanthin in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sachin Powar, R.; Singh Yadav, A.; Siva Ramakrishna, C.; Patel, S.; Mohan, M.; Sakharwade, S.G.; Choubey, M.; Kumar Ansu, A.; Sharma, A. Algae: A potential feedstock for third generation biofuel. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 63, A27–A33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaqat, B.; Dar, M.A.; Xie, R.; Sun, J. Drawbacks of first-generation biofuels: Challenges and paradigm shifts in technology for second- and third-generation biofuels. Biofuels and Sustainability: Life Cycle Assessments, System Biology, Policies, and Emerging Technologies 2025, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, R.; Bauen, A. Micro-algae cultivation for biofuels: Cost, energy balance, environmental impacts and future prospects. Biomass and Bioenergy 2013, 53, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydney, E.B.; Neto, C.J.D.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Vandenberghe, L.P. de S.; Sydney, A.C.N.; Letti, L.A.J.; Karp, S.G.; Soccol, V.T.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Soccol, C.R. Microalgal biorefineries: Integrated use of liquid and gaseous effluents from bioethanol industry for efficient biomass production. Bioresource Technology 2019, 292, 121955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetreault, J.; Fogle, R.; Guerdat, T. Towards a Capture and Reuse Model for Aquaculture Effluent as a Hydroponic Nutrient Solution Using Aerobic Microbial Reactors. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, T.J.; Wiens, D.J.; Reaney, M.J.T. Production of bioethanol—a review of factors affecting ethanol yield. Fermentation 2021, 7(Issue 4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco-Bercovich, M.; Bonet-Melia, P.; Schubert, N.; Marin-Guirao, L.; Muniz-Salazar, R.; Cabello-Pasini, A.; Ferreira-Arrieta, A.; Garcia-Pantoja, J.A.; Guzman-Calderon, J.M.; Procaccini, G. Crossing thermal limits: functional collapse of the surfgrass Phyllospadix scouleri under extreme marine heatwaves. BioRxiv 2025, 2011–2025. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, L.E.; Velasquez-Orta, S.B.; Romero-Frasca, E.; Leary, P.; Yáñez Noguez, I.; Orta Ledesma, M.T. Non-sterile heterotrophic cultivation of native wastewater yeast and microalgae for integrated municipal wastewater treatment and bioethanol production. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2019, 151, 107319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).