Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Application of nMOFs in Biomedical Fields

2.1. Metal Organic Frameworks in Drug Delivery

- the use of various metal ions or clusters and organic linkers allows for the creation of nMOFs with diverse morphologies, compositions, and sizes, facilitating the loading of a wide range of cargo molecules, from small drugs to larger proteins.

- the tuneable pore sizes and high surface area-to-volume ratios of nMOFs contribute to their ability to achieve substantial drug loading capacities.

- controlled drug release, achieved by adjusting host–guest interactions of nMOFs, can provide controllable drug release, ensuring that the therapeutic effects are directed to tumour sites and controlled.

- due to their biodegradability and safety, most nMOFs are both bio-accessible and biodegradable, which helps mitigate adverse effects on the human body [8].

2.2. Classification of the Efficacy of Combinations Therapies

2.3. PDT Combinations with IMT

2.4. Applications of Metal Organic Frameworks in Combinations of PDT with IMT

3. Purpose Statement

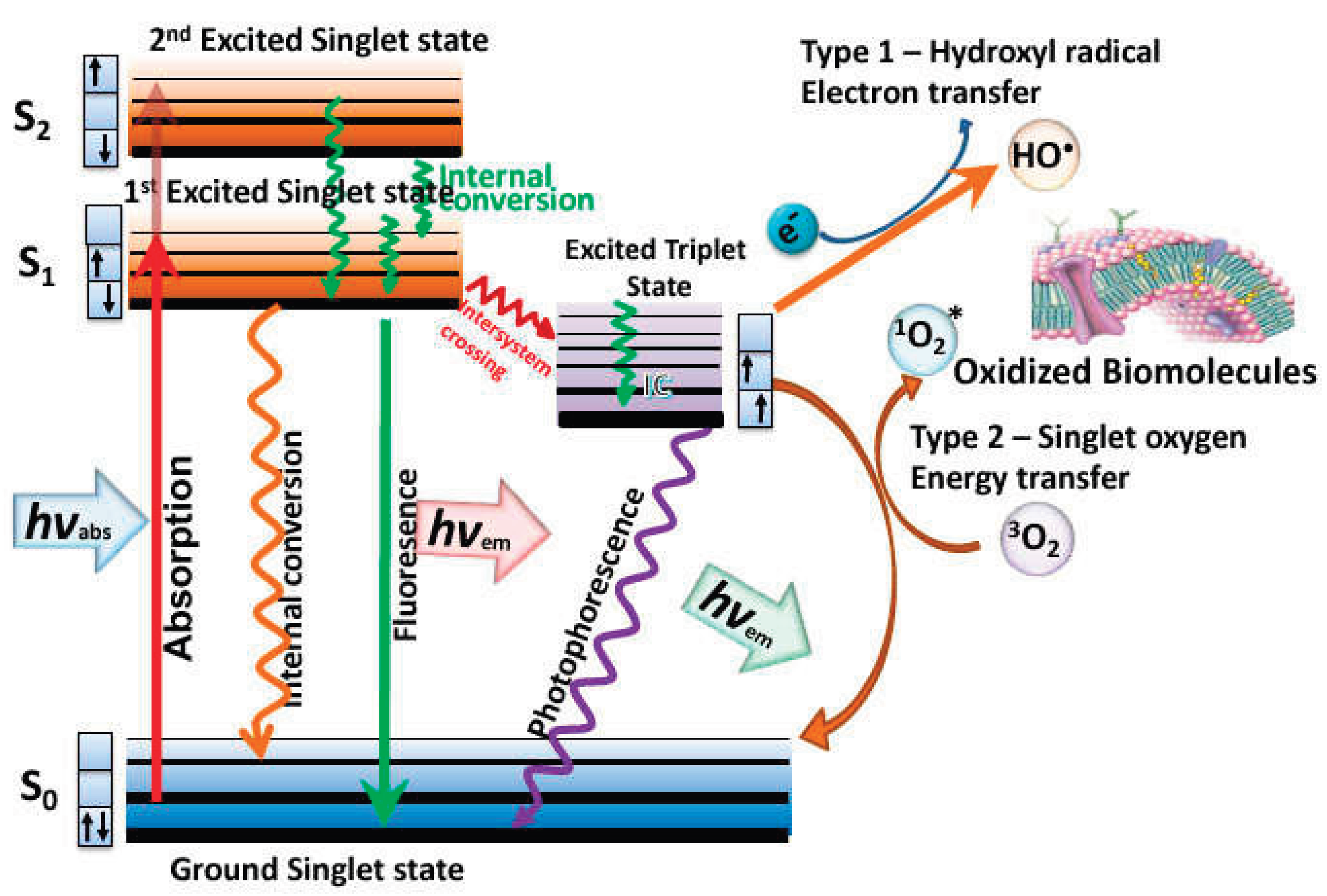

4. Photodynamic Therapy

5. Immunotherapy

5.1. Innate Immunity

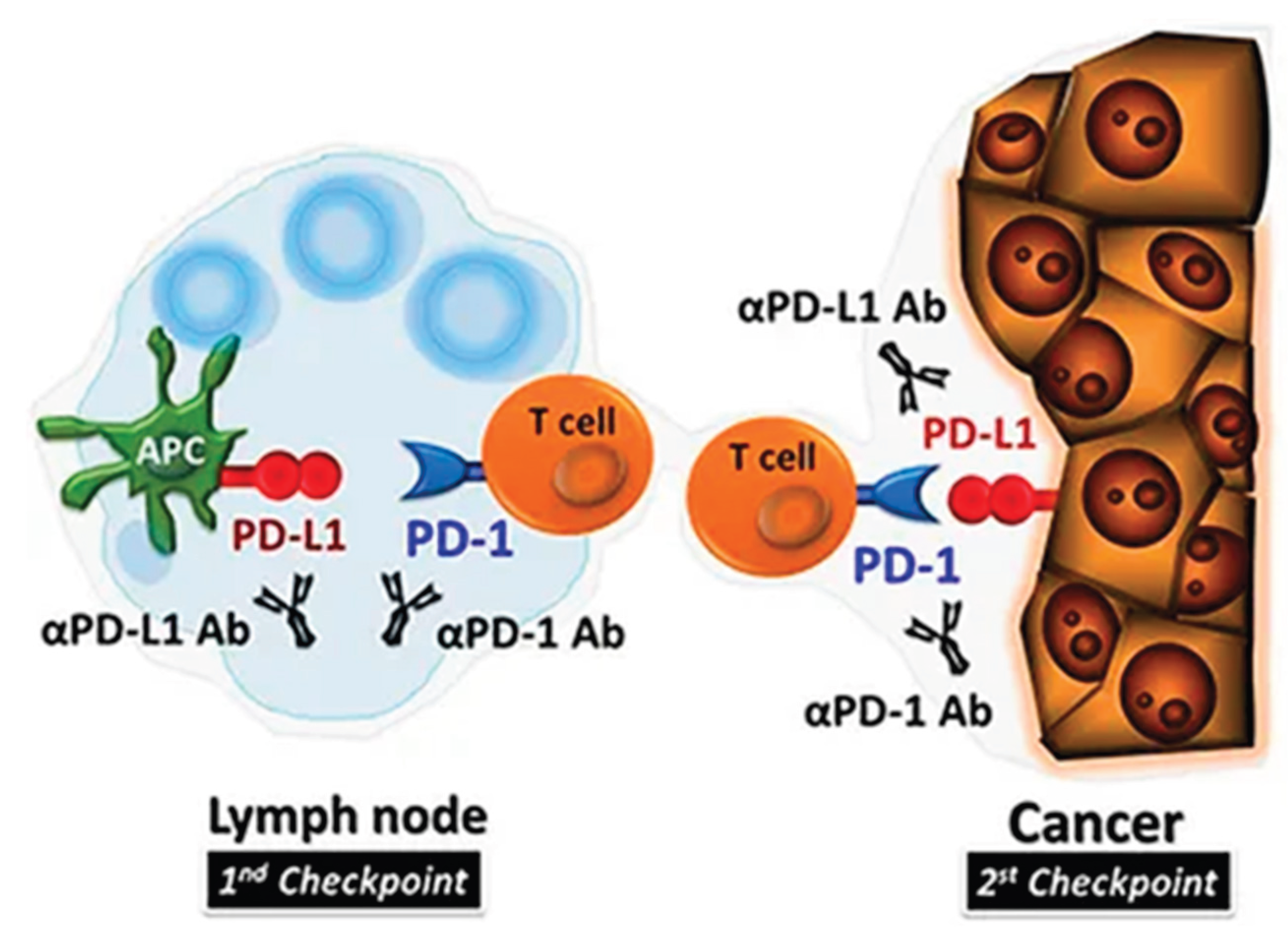

5.2. Checkpoint Inhibitors

6. Synergistic Effects of Combining PDT and IMT

6.1. Combination with Innate Immunity Stimulation

| Combination | Photosensitizer | IMT agent | Impact on tumour/cancer cells |

| PDT + checkpoint inhibitors PDT + SLP Vaccination |

mTHPC Bremachlorin |

anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies Synthetic Long Peptides (SLP) |

Research indicates that PDT enhances the efficacy of R837 by creating a more favourable immune environment [24]. When PDT was combined with therapeutic synthetic long peptide (SLP) vaccination, one-third of the treated mice were cured [25] |

| PDT + Immune Checkpoint Blockade | Several, like Ce6 | Anti-PD-1, Anti-PD-L1 | Improves antitumor immune response while prohibiting the metastasis and recurrence [23]. |

| PDT + Anti-PD-L1 | Photofrin | Anti-PD-L1 | Enhanced activation of CD8+ T-cells and decreased tumour growth observed in preclinical models [27]. |

| PDT + TLR5 agonist | Mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6 | FlaB-Vax | Increased the infiltration of tumour antigen-reactive CD8+ T cells [26] |

6.2. PDT and Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy

| Combination | Photosensitizer | IMT agents | Type of cancer | Impact on tumour/cancer cells |

| PDT + checkpoint blockage | mTHPC | PD-L1 blockade | colorectal cancer | Inhibited both primary and distant tumour growth and helped establish long-term immunological memory in the host to prevent tumour recurrence [30]. |

| PDT + checkpoint blockage | ZnP@pyro | PD-L1 antibody | primary 4T1 breast tumour | led to the complete eradication of light-irradiated primary tumours and the inhibition of untreated distant tumours by generating a systemic tumour-specific cytotoxic T cell response [31]. |

| PDT + check-point blockage | protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) | IDO1 inhibitor | 4T1 breast cancer | The combination therapy enhanced dendritic cell (DC) maturation and increased the in-filtration of IFN-γ-positive CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes into the tumour, which demonstrated to be effective in treating both CT26 and 4T1 tumours [32]. |

6.3. Synergized PDT- Immunoadjuvant Therapy

| Combination | Photosensitizer | IMT agent | Cancer type | Impact on tumour/cancer cells |

| PDT + immune adjuvants | Temoporfin and chlorin e6 (Ce6) | Calreticulin | SCCVII tumour cells | The study found that calreticulin gene expression decreased in PDT-treated cells but remained unchanged in other tissues. Overall, externally added calreticulin can augment antitumor responses mediated by PDT or PDT-generated vaccines, serving as an effective adjuvant for cancer treatment involving PDT and other stress-inducing therapies [33]. |

| photothermal therapy + immune adjuvants | Fe3O4-R837 SPs | Fe3O4 super particles (SPs), imiquimod (R837),PD-L1 antibodies and | 4T1 breast tumor | PTT also triggers the release of R837, an immune adjuvant that stimulates a robust anti-tumour immune response. When combined with checkpoint blockade therapy using PD-L1 antibodies, the Fe3O4-R837 SPs not only eliminate primary tumours but also prevented metastasis to the lungs and liver [38]. |

| Photothermal + Immunoadjuvant | indocyanine green (ICG) | imiquimod (R837) | Various cancers | The combination of photothermal agent with checkpoint blockage generated immunological responses were able to attack remaining tumour cells in mice, inhibiting metastasis and potentially being applicable to various tumour models [39]. |

7. MOFs as Carriers for PDT+IMT Therapeutics

| nMOF-Mediated Combinations | Therapeutic Agents | Mechanism | Immunologic Modulation | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zr-MOFs with TLR Agonists | TLR agonists | Activates immune pathways next to PDT | Improves immune responses through TLR signalling | Synergistic effect on tumour growth inhibition [23,42]. |

| ZIF-8@PDT + IMT | PS | Synergistic effects of PDT and IMT | Modulates tumour microenvironment to enhance immune responses | Enhanced therapeutic outcomes in resistant tumours [23,43] |

| AuNC@MnO2 NPs | Gold Nanoclusters (AuNCs), MnO2 | Induces ICD and enhances PDT efficacy | Increases tumour-associated antigens (TAAs), dendritic cells (mDC), CD4+, CD8+, NK cells | Enhanced immune response leading to tumour regression [44] |

7.1. Metabolic Pathways in nMOF

7.2. In-Vitro Studies for nMOFs as Carries of PDT+IMT Therapeutics

| Study | Type of MOF | PDT + IMT Modality | Cancer model | Key Findings / Outcomes | Cytotoxicity assessment |

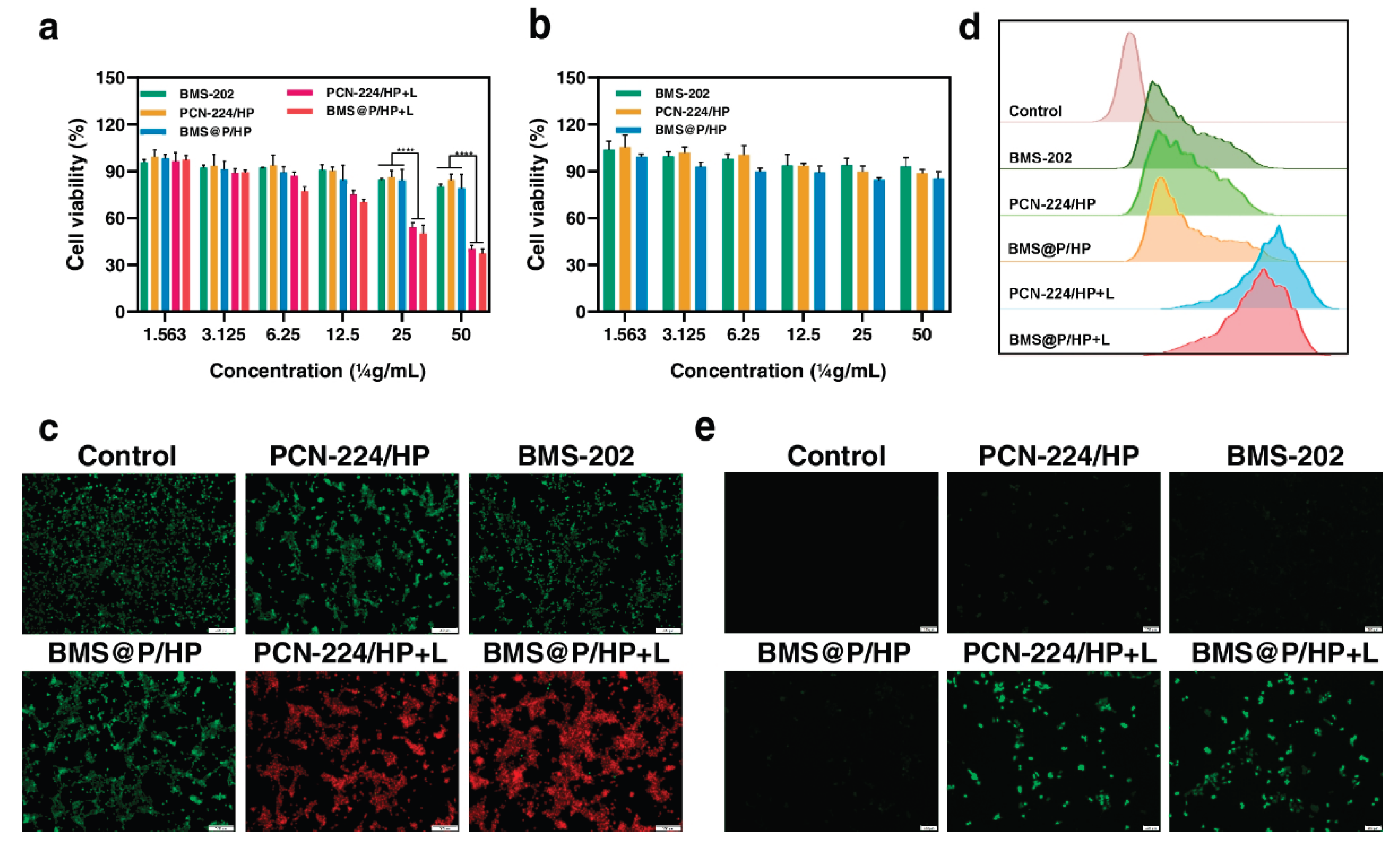

| Investigated the effect of PDT+IMT using metal-organic frameworks to inhibit metastatic progression of triple-negative breast cancer | PCN-224 | PDT + PD-L1 small molecule inhibitor BMS-202 | triple-negative breast cancer | synergistic anti-tumour approach for combining PDT and IMT | The cytotoxicity of the nanocomposite against cancer cells was assessed. Importantly, the viability of L929 cells remained nearly unchanged after treatment with PCN-224/HP and BMS@P/HP across a PCN-224 concentration range of 1.56 to 50.00 μg/ml, indicating good cytocompatibility [40]. |

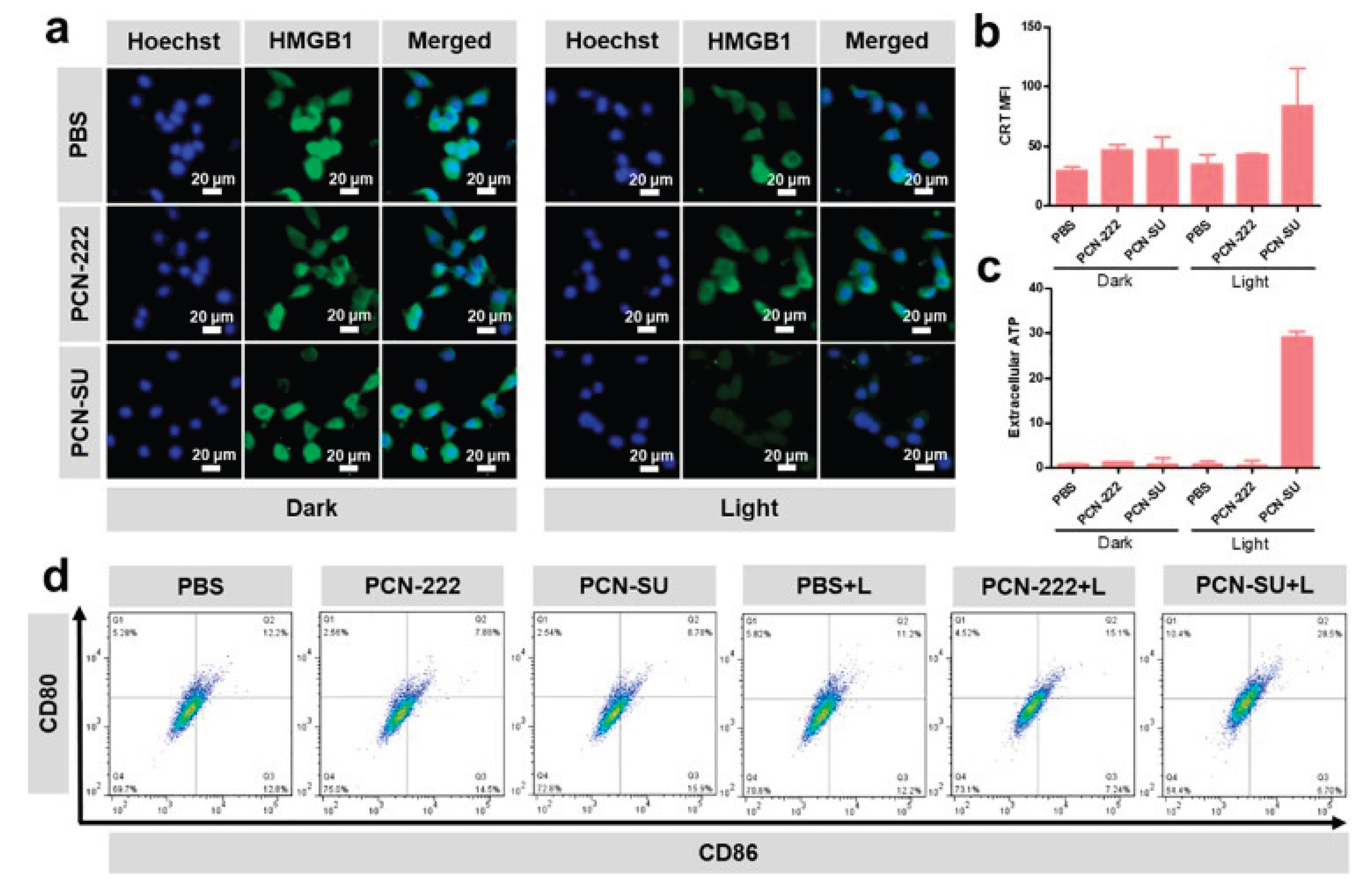

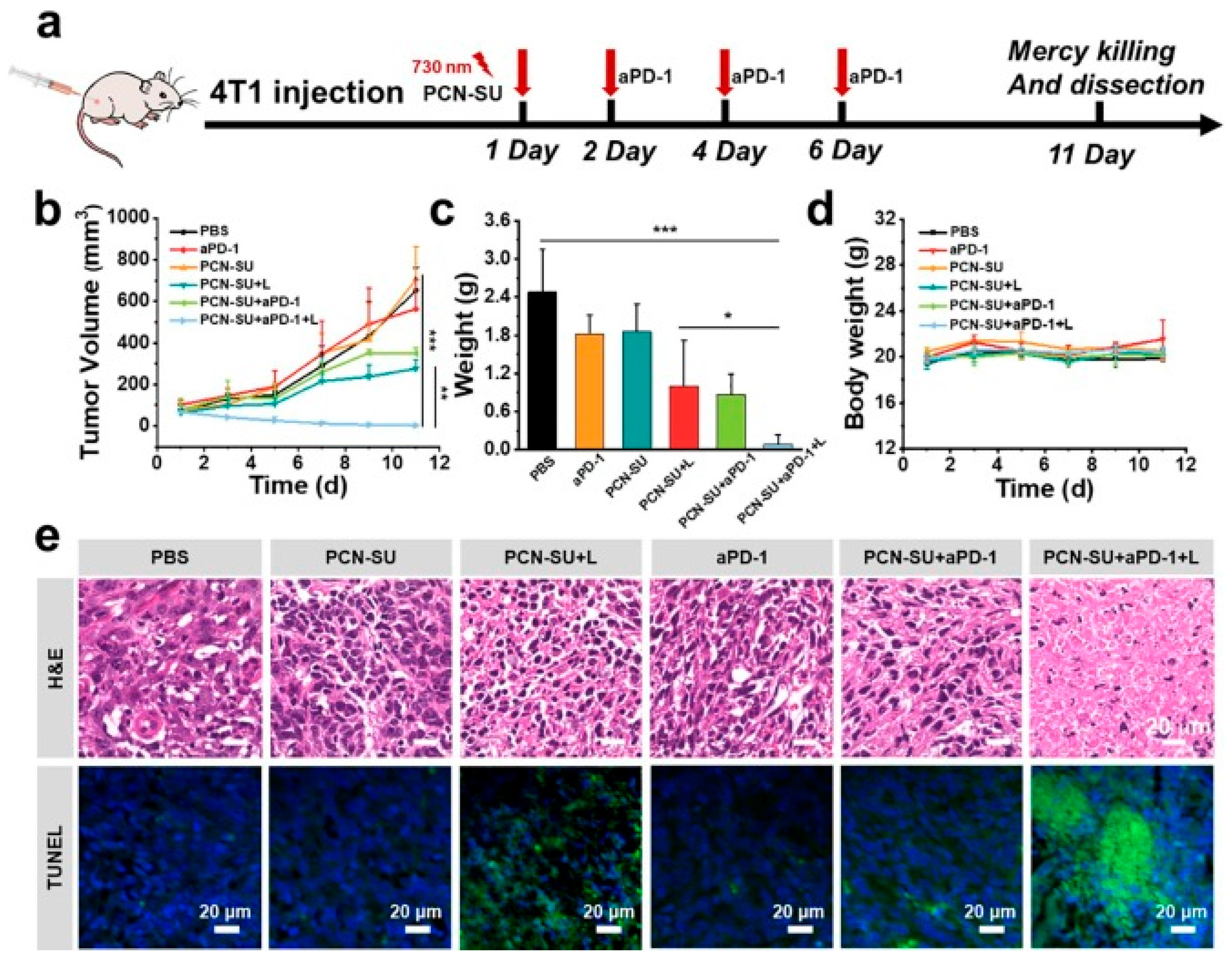

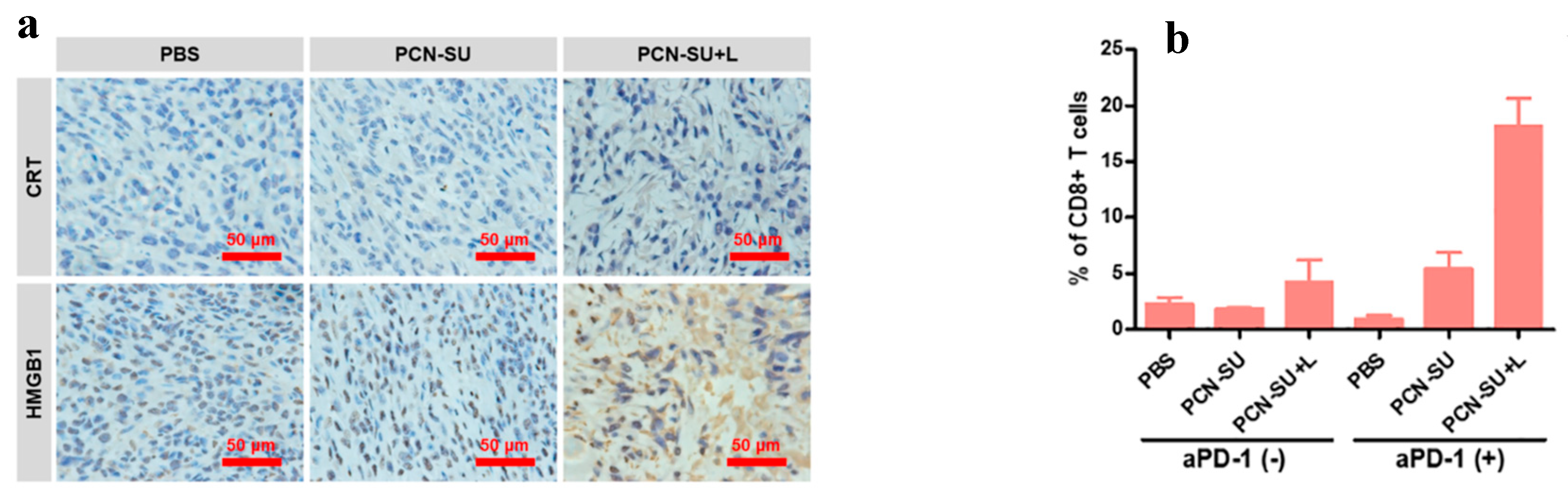

| synthesized spindle-shaped PCN-SU through a sulfonation reaction for near-infrared (NIR)-enhanced photodynamic IMT targeting 4T1 tumours | PCN-222 |

PCN-SU + IMT agent | 4T1 tumours | PDT induces ICD, releasing DAMPs that serve as signals, which help recruit and activate macrophages and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to initiate an anti-tumour immune response | Cytotoxicity was assessed indirectly by measuring HMGB1 release, CRT translocation, and extracellular ATP release after 730 nm light irradiation. The PCN-SU + light (L) group showed rapid HMGB1 release, stronger CRT translocation, and significantly increased extracellular ATP levels (10x higher), indicating enhanced immunogenic cell death (ICD) and cytotoxicity against 4T1 cells [48]. |

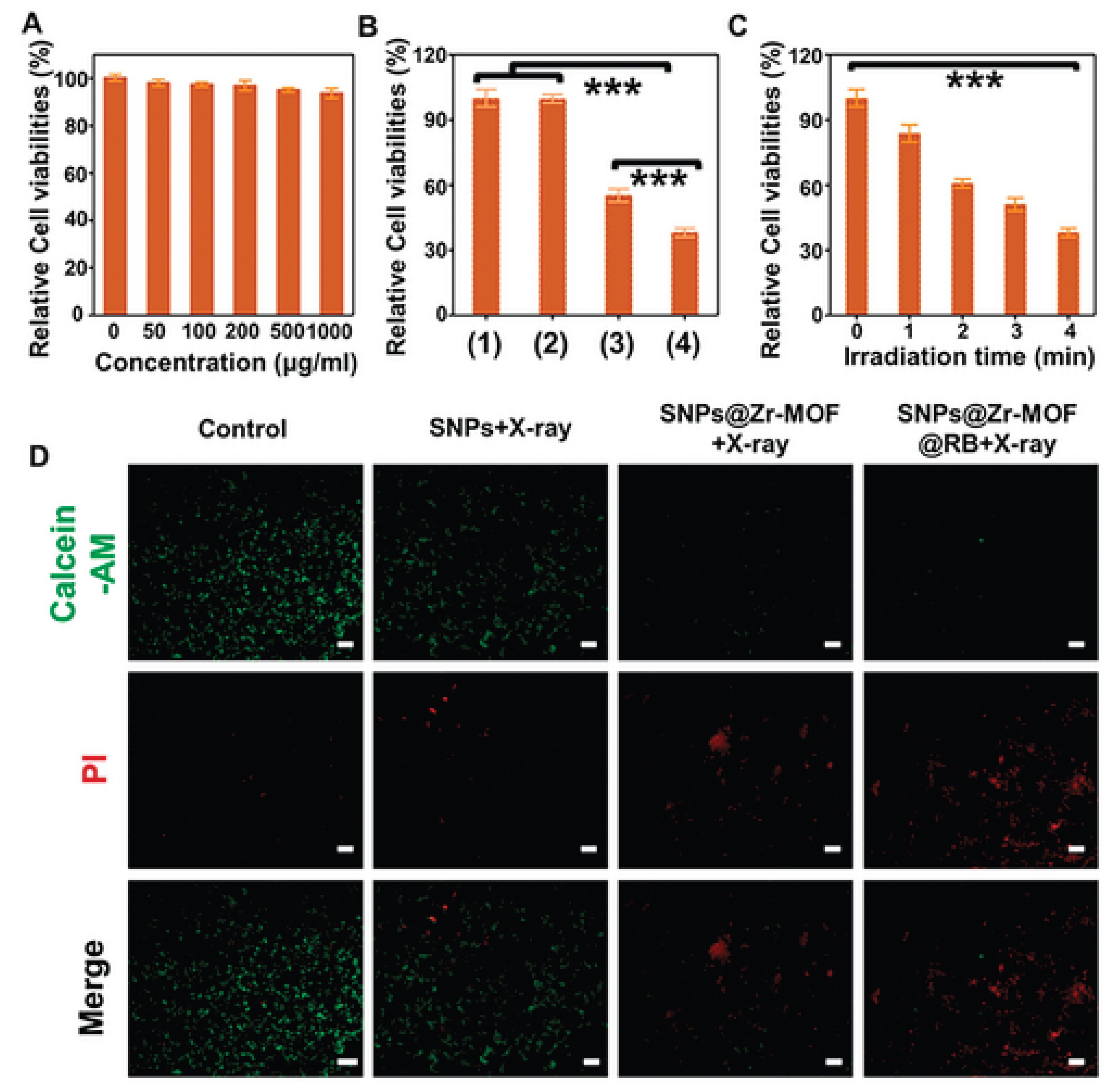

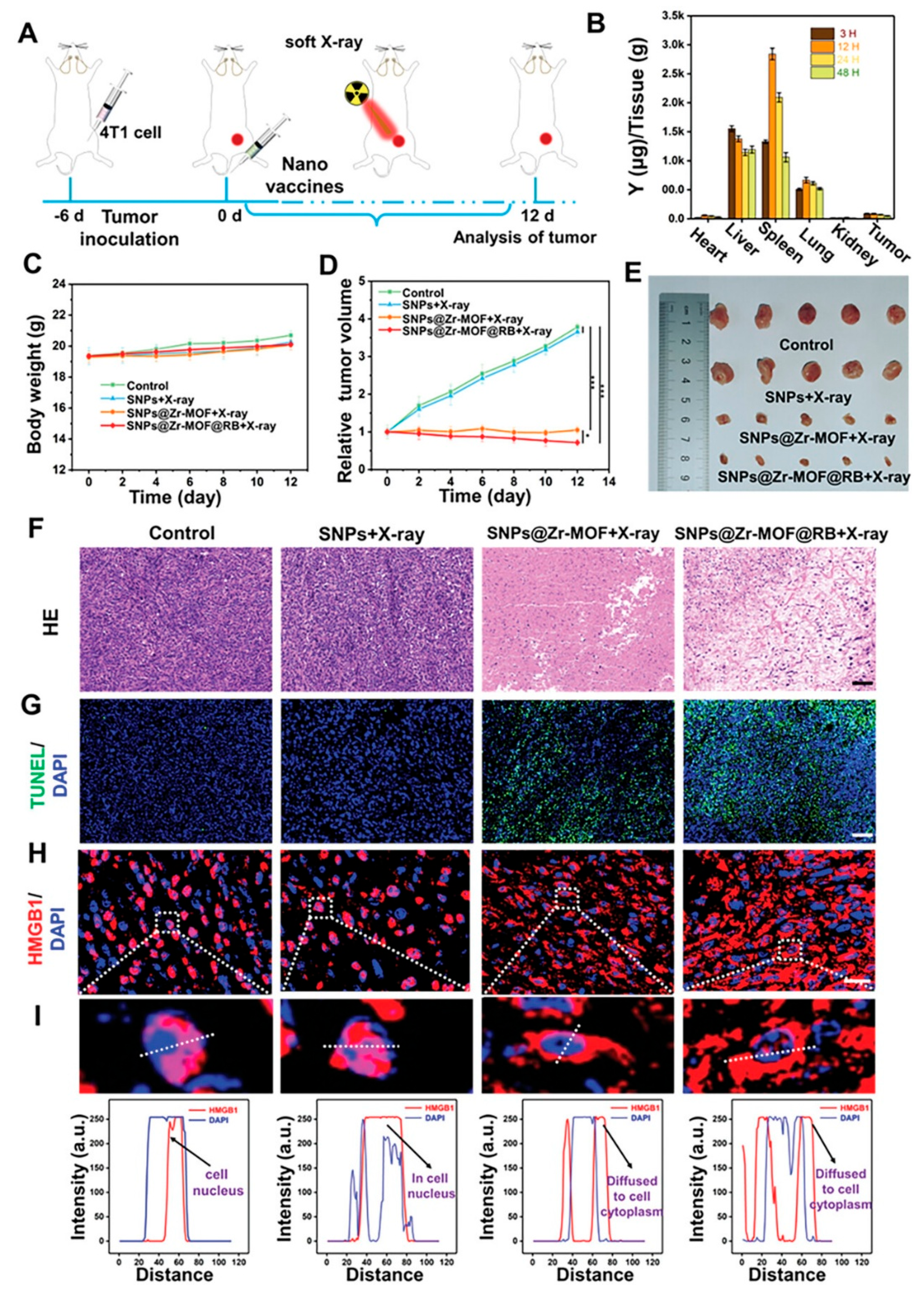

| investigated A soft X-ray-activated nanoprobe which was strategically designed by combining a porphyrin zirconium-based PnMOF with lanthanide NaYF4:Gd,Tb@NaYF4 scintillator NPs (SNPs) using a novel in situ growth method | Zr-MOF | SNPs@Zr-MOF@RB nano-probe | 4T1 cancer cells. | The in vitro therapeutic effects of the SNPs@Zr-MOF@RB nanoprobe under varying durations of X-ray irradiation time from 1 to 4 minutes led to a gradual decline in cell survival, attributed to increased ROS production. | The 4T1 cells exhibited increased viability rate of >90% after exposure to varying concentrations (0–1 mg/mL) of the SNPs@Zr-MOF@RB nanoprobe for 24 hours, indicating its low cytotoxicity and excellent biocompatibility [49]. |

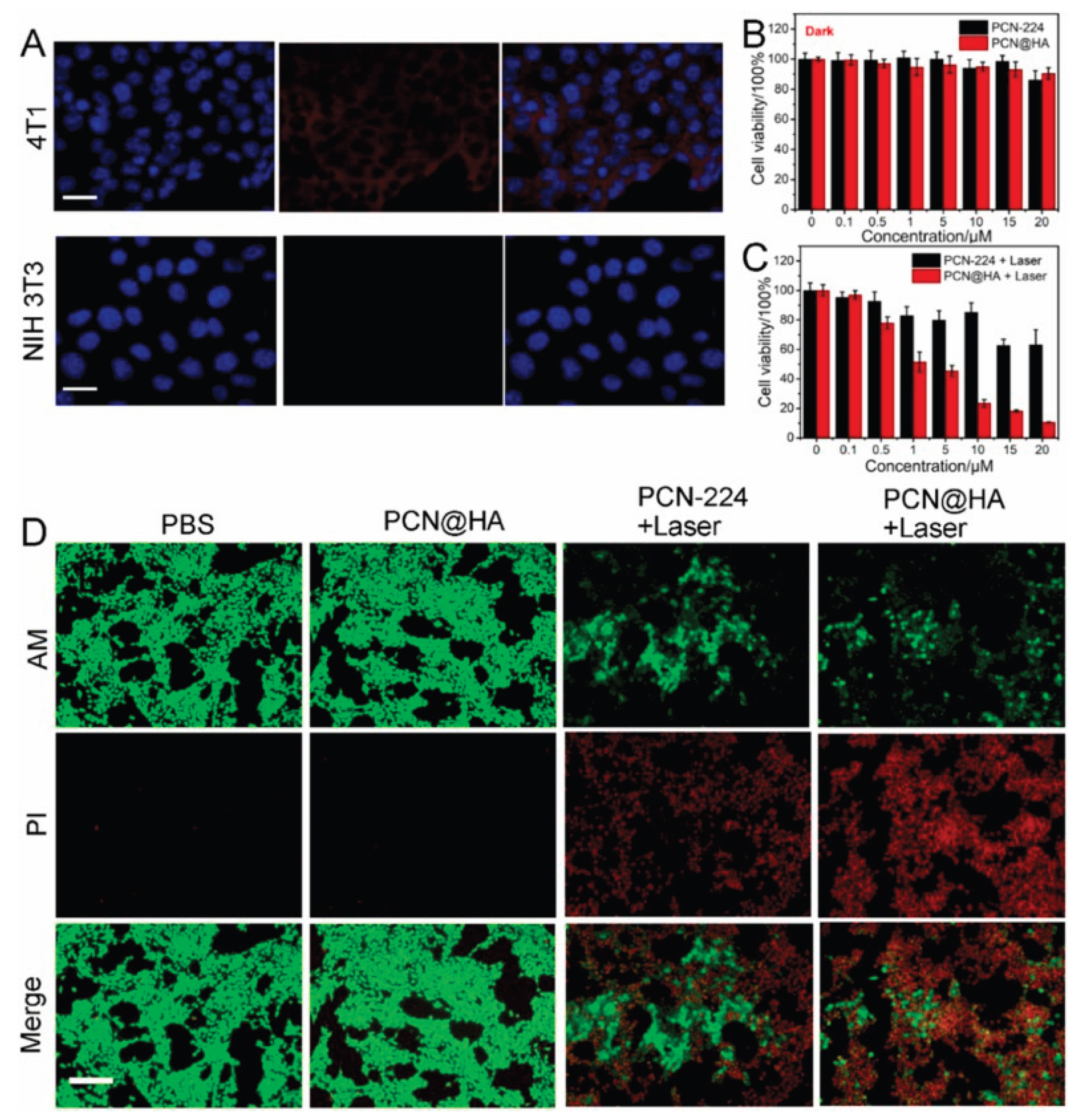

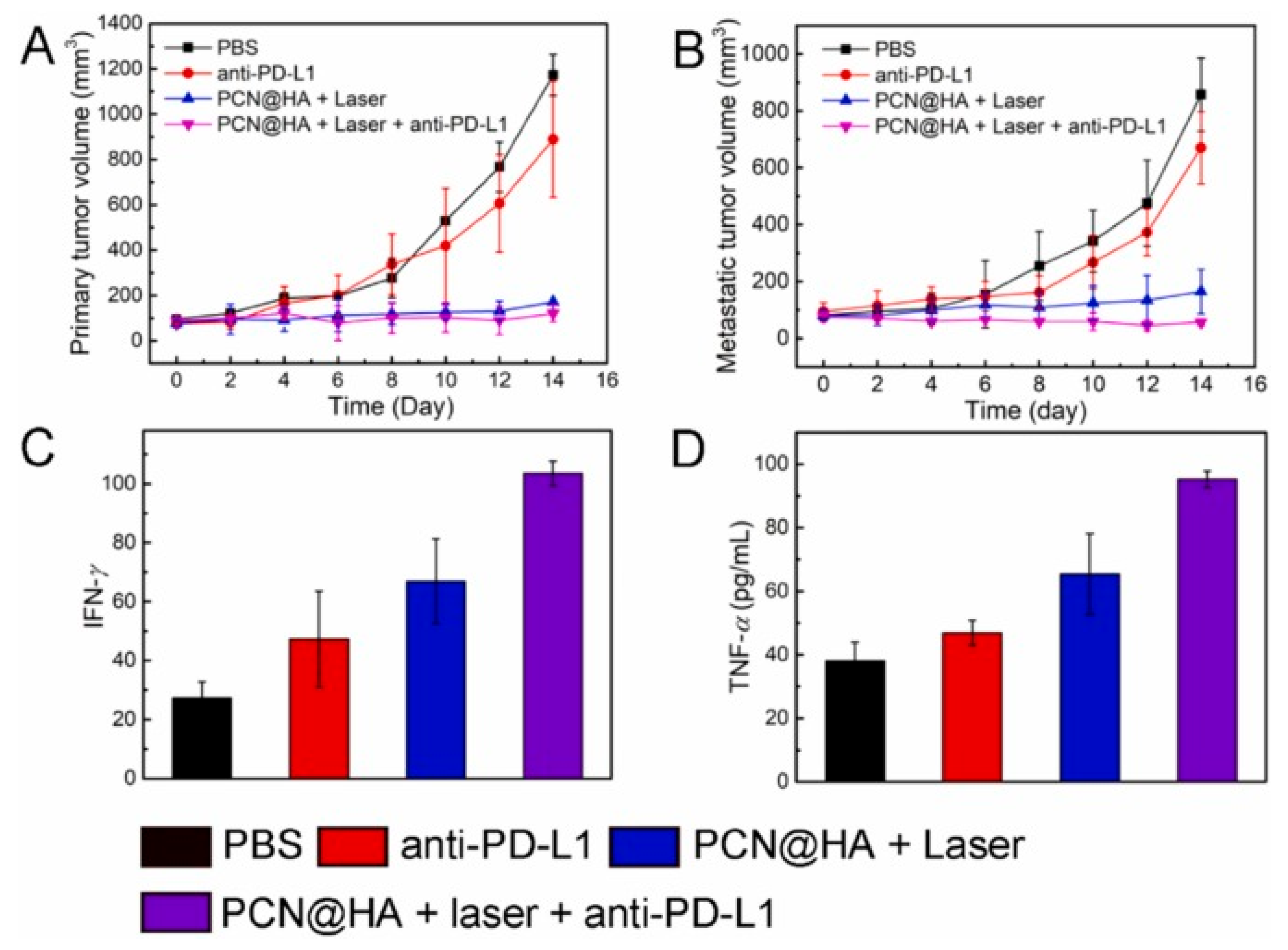

| prepared a tumour targeted nanomedicine ( designated as PCN@HA) which was engineered to increase PDT against tumour cells through modification with hyaluronic acid (HA) | PCN-MOF | PCN@HA + IMT Adjuvant | 4T1 cells | The PCN@HA is said to produce a singlet oxygen that not only destroys and kills the cancer cells but also eliminate the tumours. ). These findings clearly demonstrate that PCN@HA specifically targets 4T1 cells, attributed to the HA modification, highlighting its excellent potential for targeted drug delivery | The biocompatibility and phototoxicity of PCN@HA were evaluated using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. 4T1 cells were exposed to varying concentrations of PCN@HA for 24 hours. Minimal cytotoxicity was observed even at high concentrations of up to 20 μM without irradiation [50]. |

7.3. In-Vivo Studies of nMOFs as Carries of PDT+IMT Therapeutics

| Study | PDT + IMT Modality | Cancer / Mouse Mode | Key Findings / Outcomes | Immune Mechanisms Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCN-SU synthesized through a sulfonation reaction for near-infrared (NIR)-enhanced PDT+IMT, antitumor efficacy in 4T1 tumour-bearing BALB/c mice | PCN-SU + PD-1 and aPD-1 | 4T1 tumour-bearing BALB/c mice | The PCN-SU+aPD-1+L (PDT+IMT) group, however, achieved a remarkable 99.6% tumour growth inhibition, higher than the 57.6% inhibition from PCN-SU+L (PDT alone), demonstrating a synergistic effect between PDT and aPD-1 IMT | The PCN-SU + L group displayed higher CD80 and CD86 expression when compared to other groups. The PCN-SU + L + aPD-1 group exhibited a notably higher percentage of activated CD8+ T cells (19.1%) compared to PBS (1.92%), aPD-1 (1.21%), PCN-SU (1.91%), PCN-SU + L (6.40%), and PCN-SU + aPD-1 (6.70%) groups, while the levels of activated CD4+ T cells remained largely un-change [48]. |

| Soft X-ray triggered PDT utilizing the SNPs@Zr-MOF and SNPs@Zr-MOF@RB nanoprobes in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. | Photodynamic therapy (PDT) activated by soft X-rays, employing silver nanoparticles (SNPs) incorporated within a zirconium-based metal-organic framework (Zr-MOF), with or without the inclusion of Rose Bengal (RB) as the photosensitizing agent. | 4T1 xenografted breast tumours in mice | The combination of SNPs@Zr-MOF and X-ray treatment markedly suppressed tumor growth compared to the control groups (PBS and SNPs with X-ray). The group treated with SNPs@Zr-MOF@RB and X-ray exhibited the most effective tumor suppression, attributed to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). No significant loss in body weight or major organ toxicity was detected, indicating favorable biocompatibility. | The study primarily investigates the effects of photodynamic therapy (PDT); however, immune-related mechanisms such as dendritic cell activation or T cell responses were not specifically addressed in this excerpt [49]. |

| evaluated combining PCN@HA-mediated PDT with anti-PD-L1 checkpoint blockade in a bilateral 4T1 tumour mouse model | PCN@HA nanoparticles + Immune Checkpoint Blockade (anti-PD-L1 antibody) | Bilateral mammary carcinoma tumours derived from 4T1 cells were implanted in mice. | Treatment with either PBS or anti-PD-L1 alone did not significantly impact tumor growth. Both PCN@HA combined with laser-induced photodynamic therapy (PDT) and PCN@HA with laser plus anti-PD-L1 effectively suppressed the growth of primary tumors and prevented metastasis. The combined treatment of PCN@HA, laser, and anti-PD-L1 demonstrated greater efficacy than PDT alone. | Tumor immunity was activated through an increase in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. The antitumor immune response was further strengthened by enhanced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α [50]. |

8. Challenges

9. Future Perspectives and Innovations

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Acetic acid |

| BDC | benzene dicarboxylic acid |

| BTC | 1,3,5- benzenetricarboxylate |

| CDT | chemodynamic therapy |

| DDQ | dichlorodicyanoquinone |

| DDS | drug delivery systems |

| DEF | diethyl formamide |

| DMA | dimethyl acetamide |

| DMF | dimethyl formamide |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulphoxide |

| EPR | enhanced permeability and retention |

| EtOH | ethanol |

| ICD | immunogenic cell death |

| ICIs | immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| IMT | immunotherapy |

| LAG | Liquid assisted griding |

| ILAG | Ion and Liquid assisted griding |

| MeOH | methanol |

| MOF | Metal organic framework |

| NDC | naphthalene dicarboxylic acid |

| PDT | Photodynamic therapy |

| PS | photosensitizer |

| PT | Photothermal therapy |

| RME | reverse microemulsion |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| STS | solvothermal synthesis |

| TME | Tumour microenvironment |

| CAR | chimeric antigen receptors |

| TAM | tumour-associated macrophages |

References

- Yang, J.; Dai, D.; Zhang, X.; Teng, L.; Ma, L.; Yang, Y.-W. Multifunctional metal-organic framework (MOF)-based nanoplatforms for cancer therapy: from single to combination therapy. Theranostics 2023, 13, 295.

- He, S.; Wu, L.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Xiong, T.; Liu, J.; Huang, C.; Xu, H.; Sun, H.; Chen, W. Metal-organic frameworks for advanced drug delivery. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2021, 11, 2362-2395.

- Ye, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cao, J. Recent progress of metal-organic framework-based photodynamic therapy for cancer treatment. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2022, 2367-2395.

- Mallakpour, S.; Nikkhoo, E.; Hussain, C.M. Application of MOF materials as drug delivery systems for cancer therapy and dermal treatment. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2022, 451, 214262.

- Pattnaik, A.K.; Priyadarshini, N.; Priyadarshini, P.; Behera, G.C.; Parida, K. Recent advancements in metal organic framework-modified multifunctional materials for photodynamic therapy. Materials Advances 2024.

- Li, B.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Jiao, T. Biomedical application of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) in cancer therapy: stimuli-responsive and biomimetic nanocomposites in targeted delivery, phototherapy and diagnosis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 260, 129391.

- Wang, A.; Walden, M.; Ettlinger, R.; Kiessling, F.; Gassensmith, J.J.; Lammers, T.; Wuttke, S.; Peña, Q. Biomedical metal–organic framework materials: perspectives and challenges. Advanced functional materials 2024, 34, 2308589.

- Dong, X.; Mu, Y.; Shen, L.; Wang, H.; Huang, C.; Meng, C.; Zhang, Y. Structure engineering of Mn2SiO4/C architecture improving the potential window boosting aqueous Li-ion storage. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 456, 141031.

- Nirosha Yalamandala, B.; Shen, W.T.; Min, S.H.; Chiang, W.H.; Chang, S.J.; Hu, S.H. Advances in functional metal-organic frameworks based on-demand drug delivery systems for tumor therapeutics. Advanced NanoBiomed Research 2021, 1, 2100014.

- Shano, L.B.; Karthikeyan, S.; Kennedy, L.J.; Chinnathambi, S.; Pandian, G.N. MOFs for next-generation cancer therapeutics through a biophysical approach—a review. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2024, 12, 1397804.

- Tong, P.-H.; Zhu, L.; Zang, Y.; Li, J.; He, X.-P.; James, T.D. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) as host materials for the enhanced delivery of biomacromolecular therapeutics. Chemical Communications 2021, 57, 12098-12110.

- Hamblin, M.R.; Abrahamse, H. Inorganic salts and antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: mechanistic conundrums? Molecules 2018, 23, 3190.

- Kwiatkowski, S.; Knap, B.; Przystupski, D.; Saczko, J.; Kędzierska, E.; Knap-Czop, K.; Kotlińska, J.; Michel, O.; Kotowski, K.; Kulbacka, J. Photodynamic therapy–mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy 2018, 106, 1098-1107.

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, C.; Longo, J.P.F.; Azevedo, R.B.; Zhang, H.; Muehlmann, L.A. An updated overview on the development of new photosensitizers for anticancer photodynamic therapy. Acta pharmaceutica sinica B 2018, 8, 137-146.

- Berraondo, P.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Ochoa, M.C.; Etxeberria, I.; Aznar, M.A.; Pérez-Gracia, J.L.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.E.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Castañón, E.; Melero, I. Cytokines in clinical cancer immunotherapy. British journal of cancer 2019, 120, 6-15.

- Bayer, V.; Amaya, B.; Baniewicz, D.; Callahan, C.; Marsh, L.; McCoy, A.S. Cancer Immunotherapy. Clinical journal of oncology nursing 2017, 21.

- Yang, S.; Wu, G.-l.; Li, N.; Wang, M.; Wu, P.; He, Y.; Zhou, W.; Xiao, H.; Tan, X.; Tang, L. A mitochondria-targeted molecular phototheranostic platform for NIR-II imaging-guided synergistic photothermal/photodynamic/immune therapy. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 475.

- Herzberg, B.; Campo, M.J.; Gainor, J.F. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. The oncologist 2017, 22, 81-88.

- Kim, K.; Park, M.-H. Advancing cancer treatment: enhanced combination therapy through functionalized porous nanoparticles. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 326.

- Bienia, A.; Wiecheć-Cudak, O.; Murzyn, A.A.; Krzykawska-Serda, M. Photodynamic therapy and hyperthermia in combination treatment—Neglected forces in the fight against cancer. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1147.

- Dudzik, T.; Domański, I.; Makuch, S. The impact of photodynamic therapy on immune system in cancer–an update. Frontiers in immunology 2024, 15, 1335920.

- Liu, Z.; Xie, Z.; Li, W.; Wu, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, G.; Cao, L.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.; Xue, P. Photodynamic immunotherapy of cancers based on nanotechnology: recent advances and future challenges. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 160.

- Thiruppathi, J.; Vijayan, V.; Park, I.-K.; Lee, S.E.; Rhee, J.H. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy with photodynamic therapy and nanoparticle: making tumor microenvironment hotter to make immunotherapeutic work better. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, 1375767.

- Alvarez, N.; Sevilla, A. Current advances in photodynamic therapy (PDT) and the future potential of PDT-combinatorial cancer therapies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 1023.

- Kleinovink, J.W.; van Driel, P.B.; Snoeks, T.J.; Prokopi, N.; Fransen, M.F.; Cruz, L.J.; Mezzanotte, L.; Chan, A.; Löwik, C.W.; Ossendorp, F. Combination of photodynamic therapy and specific immunotherapy efficiently eradicates established tumors. Clinical Cancer Research 2016, 22, 1459-1468.

- Hwang, H.S.; Cherukula, K.; Bang, Y.J.; Vijayan, V.; Moon, M.J.; Thiruppathi, J.; Puth, S.; Jeong, Y.Y.; Park, I.-K.; Lee, S.E. Combination of photodynamic therapy and a flagellin-adjuvanted cancer vaccine potentiated the anti-PD-1-mediated melanoma suppression. Cells 2020, 9, 2432.

- Mušković, M.; Pokrajac, R.; Malatesti, N. Combination of two photosensitisers in anticancer, antimicrobial and upconversion photodynamic therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 613.

- Cramer, G.M.; Moon, E.K.; Cengel, K.A.; Busch, T.M. Photodynamic therapy and immune checkpoint blockade. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2020, 96, 954-961.

- Kleinovink, J.W.; Ossendorp, F. Combination of Photodynamic Therapy and Immune Checkpoint Blockade. In Photodynamic Therapy: Methods and Protocols; Springer: 2022; pp. 589-596.

- Yuan, Z.; Fan, G.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; Zhan, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Shou, C.; Gao, F.; Zhang, J.; Yin, P. Photodynamic therapy synergizes with PD-L1 checkpoint blockade for immunotherapy of CRC by multifunctional nanoparticles. Molecular Therapy 2021, 29, 2931-2948.

- Duan, X.; Chan, C.; Guo, N.; Han, W.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Lin, W. Photodynamic therapy mediated by nontoxic core–shell nanoparticles synergizes with immune checkpoint blockade to elicit antitumor immunity and antimetastatic effect on breast cancer. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 16686-16695.

- Huang, Z.; Wei, G.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Shen, Y.; Sun, X.; Xu, C.; Zhao, C. Enhanced cancer therapy through synergetic photodynamic/immune checkpoint blockade mediated by a liposomal conjugate comprised of porphyrin and IDO inhibitor. Theranostics 2019, 9, 5542.

- Korbelik, M.; Banath, J.; Saw, K.M.; Zhang, W.; Čiplys, E. Calreticulin as cancer treatment adjuvant: combination with photodynamic therapy and photodynamic therapy-generated vaccines. Frontiers in oncology 2015, 5, 15.

- Obeid, M.; Tesniere, A.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Fimia, G.M.; Apetoh, L.; Perfettini, J.-L.; Castedo, M.; Mignot, G.; Panaretakis, T.; Casares, N. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nature medicine 2007, 13, 54-61.

- Guo, R.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Zong, Q.; Li, T.; Ling, G.; Zhang, P. Engineered nanomaterials for synergistic photo-immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2022, 282, 121425.

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Bai, X.; Wu, X.; Guo, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Combination of phototherapy with immune checkpoint blockade: Theory and practice in cancer. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 955920.

- Meng, Z.; Zhou, X.; Xu, J.; Han, X.; Dong, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; She, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, C. Light-triggered in situ gelation to enable robust photodynamic-immunotherapy by repeated stimulations. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1900927.

- Ge, R.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, D.; Hou, Y. Photothermal-activatable Fe3O4 superparticle nanodrug carriers with PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade for anti-metastatic cancer immunotherapy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2018, 10, 20342-20355.

- Chen, Q.; Xu, L.; Liang, C.; Wang, C.; Peng, R.; Liu, Z. Photothermal therapy with immune-adjuvant nanoparticles together with checkpoint blockade for effective cancer immunotherapy. Nature communications 2016, 7, 13193.

- Liang, X.; Mu, M.; Chen, B.; Fan, R.; Chen, H.; Zou, B.; Han, B.; Guo, G. Metal-organic framework-based photodynamic combined immunotherapy against the distant development of triple-negative breast cancer. Biomaterials Research 2023, 27, 120.

- Zeng, J.-Y.; Zou, M.-Z.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.-S.; Zeng, X.; Cong, H.; Zhang, X.-Z. π-extended benzoporphyrin-based metal–organic framework for inhibition of tumor metastasis. ACS nano 2018, 12, 4630-4640.

- Hua, J.; Wu, P.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Z.; He, J.; Zhong, L.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y. Current strategies for tumor photodynamic therapy combined with immunotherapy. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11, 738323.

- Song, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, Z. Metal–organic frameworks for photodynamic therapy: emerging synergistic cancer therapy. Biotechnology Journal 2021, 16, 1900382.

- Ji, B.; Wei, M.; Yang, B. Recent advances in nanomedicines for photodynamic therapy (PDT)-driven cancer immunotherapy. Theranostics 2022, 12, 434.

- Prasad, S.B.; Shinde, A.; Srinivasrao, D.A.; Famta, P.; Shah, S.; Kolipaka, T.; Pandey, G.; Gaonker, D.; Vambhurkar, G.; Khairnar, P. Metal-Organic Frameworks as Therapeutic Chameleons: Revolutionizing the Cancer Therapy Employing Novel Nanoarchitectonics. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2025, 101054.

- Wang, N.; Song, W.; Ji, J.; Guo, W.; Du, Q. Metal-organic framework nanomaterials alter cellular metabolism in bladder cancer. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2025, 298, 118292.

- Soman, S.; Kulkarni, S.; Kulkarni, J.; Dhas, N.; Roy, A.A.; Pokale, R.; Mukharya, A.; Mutalik, S. Metal–organic frameworks: a biomimetic odyssey in cancer theranostics. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 12620-12647.

- Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Pei, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, Z. Near-infrared light-boosted photodynamic-immunotherapy based on sulfonated metal-organic framework nanospindle. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 437, 135370.

- Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Du, L.; Deng, Z.; Jiang, M.; Zeng, S. Soft x-ray stimulated lanthanide@ MOF nanoprobe for amplifying deep tissue synergistic photodynamic and antitumor immunotherapy. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2021, 10, 2101174.

- Liu, Y.; Zou, B.; Yang, K.; Jiao, L.; Zhao, H.; Bai, P.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, R. Tumor targeted porphyrin-based metal–organic framework for photodynamic and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2024, 239, 113965.

- Hirakawa, A.; Asano, J.; Sato, H.; Teramukai, S. Master protocol trials in oncology: review and new trial designs. Contemporary clinical trials communications 2018, 12, 1-8.

- Harvey, P.D.; Plé, J. Recent advances in nanoscale metal–organic frameworks towards cancer cell cytotoxicity: an overview. Journal of inorganic and organometallic polymers and materials 2021, 31, 2715-2756.

- Fernandes, P.D.; Magalhães, F.D.; Pereira, R.F.; Pinto, A.M. Metal-organic frameworks applications in synergistic cancer photo-immunotherapy. Polymers 2023, 15, 1490.

- Nguyen, N.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Ge, S.; Liew, R.K.; Nguyen, D.T.C.; Van Tran, T. Recent progress and challenges of MOF-based nanocomposites in bioimaging, biosensing and biocarriers for drug delivery. Nanoscale Advances 2024, 6, 1800-1821.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).