1. Introduction

Primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCLs) represent a diverse group of T- and B-cell neoplasms confined to the skin at diagnosis, with no evidence of extracutaneous disease. They differ from systemic lymphomas with secondary skin involvement in terms of pathogenesis, clinical course and prognosis, requiring a dedicated classification and management approach [

1]. In the updated WHO–EORTC classification, the most prevalent entities are CTCL, particularly mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS), and three major PCBCL subtypes: primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma/lymphoproliferative disorder (PCMZL/LPD) and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (PCDLBCL-LT) [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Epidemiologically, CTCLs are rare, with an annual incidence around 6–7 cases per million, and MF/SS accounting for approximately half of all CTCLs [

5,

6]. PCBCLs are less common but represent about one quarter of all PCLs in Western cohorts [

3,

7]. Despite their rarity, PCLs have a significant impact on quality of life due to chronic, often therapy-refractory skin disease, pruritus and disfiguring lesions, and they require long-term follow-up by dermatologists.

Over the last decade, advances in next-generation sequencing, transcriptomics and microenvironmental profiling have reshaped our understanding of PCL biology [

4,

6,

8]. Recurrent alterations in TCR signalling (e.g. PLCG1), co-stimulatory and JAK–STAT pathways, epigenetic regulators and immune checkpoints have been described in CTCL, while PCBCLs show subtype-specific patterns such as MYD88/CD79B mutations in PCDLBCL-LT [

3,

4,

8,

9]. These discoveries underpin a rapidly evolving therapeutic landscape that includes monoclonal antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates and immune modulators.

This review provides an integrated, dermatology-focused overview of PCLs, emphasising practical diagnostic considerations, recent biologic insights and clinically relevant therapeutic advances.

2. Results

To provide an integrated overview of the main clinicopathologic and therapeutic concepts emerging from the reviewed literature, we summarised key themes in

Table 1.

2.1. Classification and Clinicopathologic Spectrum

2.1.1. Evolution of the WHO–EORTC Framework

The 2018 WHO–EORTC update consolidated PCL entities and incorporated new lymphoproliferative disorders, reflecting their distinct clinical behaviour [

1]. Notable changes include reclassification of primary cutaneous CD4⁺ small/medium T-cell lymphoma as a lymphoproliferative disorder, expansion of the spectrum of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) and recognition of primary cutaneous acral CD8⁺ T-cell lymphoma and EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer as provisional entities [

1,

2]. The International Consensus Classification and the 5th edition of the WHO haematologic neoplasm classification further harmonise cutaneous and systemic lymphoma taxonomy [

2,

10].

2.1.2. Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas

MF is the prototypic CTCL, typically presenting with slowly progressive patches and plaques on photoprotected sites. Histologically, it is characterised by epidermotropic atypical T cells, often CD4⁺, with variable loss of pan-T-cell antigens and a clonal TCR gene rearrangement. Clinical variants include folliculotropic, pagetoid reticulosis and granulomatous slack skin, each with distinct prognostic implications [

5,

6,

69]. SS is defined by triad of erythroderma, lymphadenopathy and a leukaemic clone of neoplastic T cells in peripheral blood, often with prominent expression of PD-1 and other follicular helper T-cell markers [

1,

5,

23].

Other CTCL entities of dermatologic relevance include primary cutaneous CD30⁺ T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, C-ALCL), primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8⁺ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma and primary cutaneous acral CD8⁺ T-cell lymphoma [

1,

2,

69]. CD30⁺ disorders, while histologically malignant-appearing, often display indolent clinical behaviour and may regress spontaneously, making accurate clinicopathologic correlation essential [

70].

2.1.3. Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas

PCBCLs are confined to the skin at diagnosis and show a predilection for the head/neck and trunk. PCFCL typically presents as solitary or grouped plaques or tumours on the scalp or trunk, composed of centrocytes and centroblasts with a germinal centre B-cell phenotype (CD20⁺, CD79a⁺, BCL6⁺, often BCL2-negative) [

3,

7]. PCMZL/LPD exhibits nodular or plaque-like lesions on the trunk or upper extremities, with marginal-zone B cells, plasma cells and frequent evidence of chronic antigenic stimulation; it is now considered a lymphoproliferative disorder in some classifications due to its excellent prognosis [

3,

10].

PCDLBCL-LT, in contrast, is an aggressive lymphoma presenting as rapidly enlarging tumours on one or both legs, more common in elderly women and associated with frequent MYD88L265P and CD79B mutations and strong expression of BCL2 and MUM1/IRF4 [

3,

4,

9]. Correct distinction between PCFCL with large-cell morphology and PCDLBCL-LT is crucial, as it dictates the need for systemic chemo-immunotherapy rather than local therapies alone.

2.2. Molecular Pathogenesis and Tumour Microenvironment

2.2.1. Genomic Landscape of CTCL

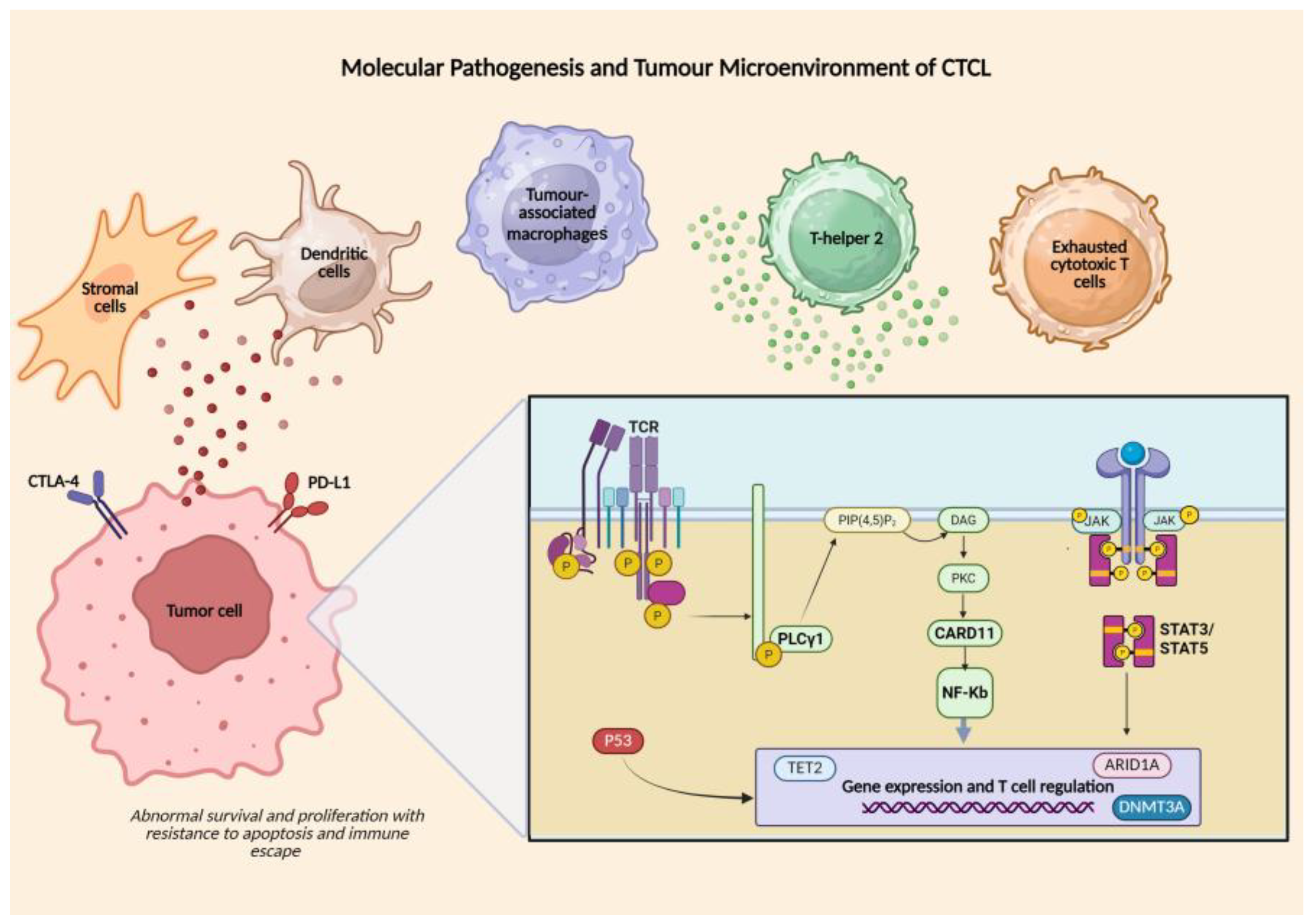

Genomic profiling has identified recurrent copy-number alterations and mutations affecting TCR signalling (PLCG1, CARD11), JAK–STAT pathway components (STAT3, STAT5B, JAK1, JAK3), NF-κB regulators, epigenetic modifiers (DNMT3A, TET2, ARID1A) and tumour suppressors (TP53, CDKN2A) in MF/SS [

6,

8,

11]. These changes converge on abnormal survival and proliferation of malignant T cells, along with resistance to apoptosis and immune escape. UV mutational signatures and chromosomal instability further support a role for environmental and stochastic factors in CTCL pathogenesis [

17].

2.2.2. Tumour Microenvironment and Immune Evasion

The CTCL microenvironment is enriched in tumour-associated macrophages, regulatory T cells, Th2-skewed cytokines and exhausted cytotoxic T cells, creating an immunosuppressive milieu [

4,

8,

12]. Expression of PD-1/PD-L1, CTLA-4, and other checkpoints, as well as altered antigen presentation, contributes to tumour immune escape and may influence responsiveness to immunotherapies. Crosstalk between malignant T cells and stromal or dendritic cells via chemokines and cytokines shapes skin tropism and disease progression [

8,

12].

2.2.3. Molecular Features of PCBCL

PCBCLs share some molecular features with their nodal counterparts but show distinctive patterns. PCFCL often lacks BCL2 translocations and exhibits a more restricted mutational profile than nodal follicular lymphoma, whereas PCMZL/LPD is frequently associated with chronic antigenic drive (e.g. Borrelia in some geographic regions) and displays plasmacytic differentiation and class-switched immunoglobulin rearrangements [

3,

7,

10]. PCDLBCL-LT shows frequent MYD88 and CD79B mutations, activation of NF-κB signalling and an immune-privileged microenvironment enriched in M2 macrophages, supporting the use of rituximab-based chemo-immunotherapy and, potentially, novel targeted agents [

3,

4,

9].

The key molecular drivers and microenvironmental interactions that sustain MF/SS pathogenesis are summarised in

Figure 1.

The CTCL microenvironment is enriched in tumour-associated macrophages, regulatory T cells, Th2-skewed cytokines and exhausted cytotoxic T cells. Crosstalk between malignant T cells and stromal or dendritic cells, mediated by chemokines and cytokines, drives skin tropism and disease progression. Tumor cells are characterized by copy-number alterations and mutations affecting TCR signalling (PLCG1, CARD11), the JAK–STAT pathway, NF-κB regulators, epigenetic modifiers (DNMT3A, TET2, ARID1A) and tumour suppressors such as TP53 and CDKN2A. Expression of PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 contributes to tumour immune escape and may influence immunotherapy response. [

6,

8,

11,

12,

16]

2.3. Diagnosis and Staging: A Dermatologic Approach

2.3.1. Clinical Assessment and Imaging

Early MF often mimics chronic eczematous or psoriasiform dermatoses, resulting in diagnostic delays of several years in many patients [

18]. Dermatologists should maintain a high index of suspicion for persistent, therapy-refractory patches and plaques on photoprotected sites, especially when accompanied by poikiloderma, atrophy or follicular involvement. Detailed full-body skin examination, photographic documentation and severity scores (e.g. mSWAT) are essential for longitudinal assessment.

Dermatoscopy and high-frequency ultrasound or line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT) may assist in distinguishing inflammatory dermatoses from early lymphoma and in selecting optimal biopsy sites [

22]. In PCBCL, clinical distribution (head/neck vs leg), number of lesions and growth kinetics provide important prognostic clues [

3,

7].

2.3.2. Histopathology, Immunophenotyping and Molecular Studies

Multiple, adequately deep biopsies from representative lesions are often required. For MF/SS, classic features include epidermotropism, Pautrier microabscesses and atypical cerebriform T cells, but early lesions may be subtle, and clinicopathologic correlation with repeated biopsies is often necessary [

5,

69]. Immunophenotyping typically demonstrates a CD3⁺, CD4⁺, CD45RO⁺ phenotype with variable loss of CD7, CD26 or other pan-T antigens; CD30 expression, when present, must be interpreted in the broader context to differentiate large-cell transformation from co-existing CD30⁺ lymphoproliferative disorders [

5,

13,

70].

TCR gene rearrangement studies and, increasingly, high-throughput sequencing of T-cell clonotypes help confirm clonality in challenging cases and assess blood involvement in SS. Flow cytometry of peripheral blood can quantify aberrant CD4⁺ populations and supports TNMB staging [

13,

23].

In PCBCL, histology and immunophenotype (germinal centre vs marginal-zone vs activated B-cell phenotype) are complemented by molecular tests for IGH/IGK rearrangements, MYD88 mutations and exclusion of systemic disease by imaging and bone marrow evaluation where appropriate [

3,

4,

7].

2.3.3. Staging and Prognostic Stratification

The ISCL/EORTC TNMB staging system remains the cornerstone for MF/SS, with skin-limited early stages (IA–IIA) showing excellent disease-specific survival and advanced stages with nodal, visceral or blood involvement carrying poorer outcomes [

5,

6,

24]. International registry efforts such as PROCLIPI have highlighted substantial diagnostic delay and identified clinical and laboratory predictors of progression in early MF [

14,

18]. In PCBCL, subtype (indolent vs aggressive), lesion multiplicity, leg involvement and patient age are key prognostic factors [

3,

7]. Racial and ethnic disparities also influence outcomes in MF/SS. A large retrospective cohort from a major cancer referral center demonstrated that African American/Black patients present with more advanced stage, have higher blood involvement, and experience worse overall survival compared with White patients, even after adjusting for stage and treatment variables [

19].

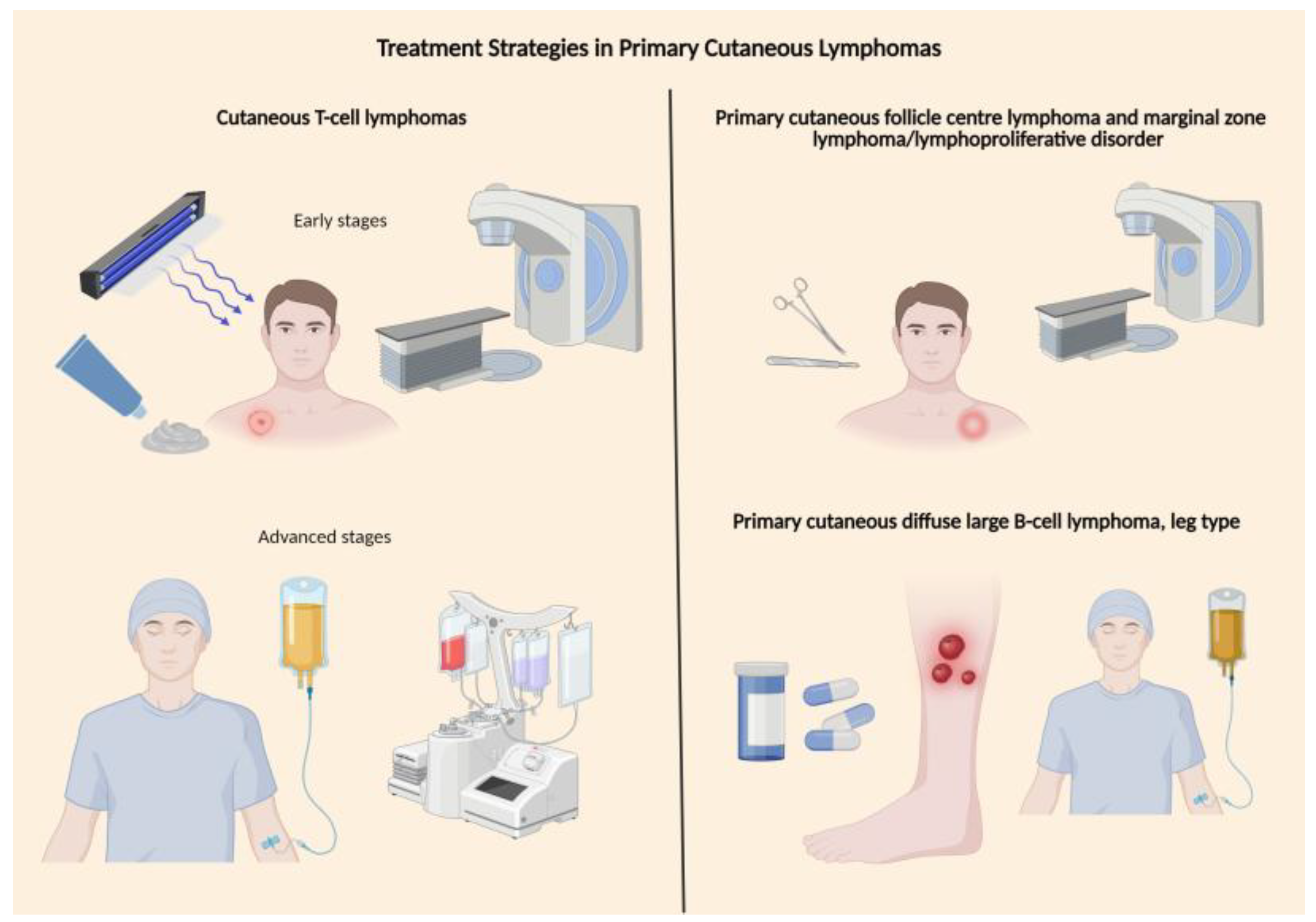

2.4. Therapeutic Landscape of Primary Cutaneous Lymphomas

2.4.1. Principles of Treatment Stratification

The therapeutic approach to primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCLs) is shaped by histotype, stage, symptom burden and comorbidities, and must balance disease control with long-term toxicity in a largely chronic, relapsing setting. In mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS), early stages are typically managed with skin-directed treatments (topical corticosteroids, chlormethine, phototherapy, localized radiotherapy), whereas advanced stages require systemic agents, often administered sequentially, with allogeneic haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation reserved for selected fit patients with aggressive or refractory disease [

1,

5,

14,

20,

25,

26,

27,

45]. Consensus recommendations from EORTC, ISCL and NCCN emphasize a risk-adapted strategy that prioritizes skin-directed modalities and low-toxicity systemic agents in early disease, while reserving more intensive or experimental therapies for advanced or transformed stages [

1,

3,

20,

25,

26,

27,

45].

In primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (PCBCLs), indolent entities such as primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma (PCFCL) and marginal zone lymphoma/lymphoproliferative disorder (PCMZL/LPD) generally respond to localized radiotherapy or surgical excision and have an excellent prognosis, with skin-limited relapses that are amenable to repeat local treatment [

1,

4,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. In contrast, primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (PCDLBCL-LT) behaves as an aggressive lymphoma, often requiring anthracycline-based immunochemotherapy and, increasingly, novel immunomodulatory and B-cell receptor (BCR)/BTK-inhibitor–based strategies in the relapsed setting [

4,

26,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

65,

66,

67,

71].

Dermatologists are central to this landscape: they frequently determine the initial diagnostic pathway, longitudinally assess cutaneous response and toxicity, and often coordinate multidisciplinary care with haematologists, radiation oncologists and transplant teams.

2.4.2. Established Systemic Agents and Targeted Small Molecules in CTCL

For MF/SS requiring systemic therapy, so-called “conventional” agents—now often considered first-generation targeted or immunomodulatory therapies—remain important anchors of treatment [

5,

15,

25,

26,

27,

45].

Topical mechlorethamine. A randomized, controlled, multicentre trial demonstrated that 0.02% mechlorethamine (chlormethine) gel achieved overall response rates (ORR) of approximately 60% in stage IA–IIA MF, with durable cutaneous responses and manageable local dermatitis [

37]. Real-world evidence and prospective studies have clarified the spectrum of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis and the role of supportive care. The MIDAS randomized study demonstrated that prophylactic use of topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment significantly reduces chlormethine-induced dermatitis while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [

38]. Clinical experience and guideline-based recommendations have confirmed its effectiveness and clarified the spectrum of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis, underscoring the need for proactive skin care, topical corticosteroids and schedule modification to preserve adherence [

5,

15,

25,

26,

27,

45]. Mechanistic work demonstrates that chlormethine exerts cytotoxic activity not only through DNA alkylation but also through induction of immunogenic cell death and immune-microenvironment remodeling, as recently characterized in a detailed dermatopathologic and molecular study [

39].

Retinoids. Oral bexarotene remains a backbone for advanced-stage MF/SS. In the pivotal multinational phase II–III trial of refractory advanced CTCL, bexarotene produced an ORR of 45% with a median response duration of approximately nine months and meaningful improvement in pruritus in a subset of patients [

40]. Its toxicity profile—dominated by hypertriglyceridaemia, central hypothyroidism and hepatic enzyme elevation—requires close dermatologic and metabolic monitoring, but the drug is particularly attractive in pruritic erythrodermic disease and is frequently used in combination with phototherapy, interferon-α or low-dose methotrexate [

5,

15,

25,

26,

27,

45].

Extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP). ECP represents a key immunomodulatory option for erythrodermic MF/SS, especially in patients with significant blood involvement or Sézary syndrome [

5,

15,

25,

26,

27,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Early series and long-term follow-up studies demonstrated durable responses and favourable survival in subsets of patients, often when ECP is integrated into multimodality regimens that include interferon-α, bexarotene or systemic corticosteroids [

41,

42,

43]. Subsequent single-centre and multicentre experiences have confirmed that ECP can induce partial and complete remissions with an excellent safety profile, supporting repeated cycles over many months or years and making it particularly suitable for frail patients and those in whom cytotoxic chemotherapy is undesirable [

41,

42,

43,

44].

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors. Vorinostat and romidepsin are well-established systemic agents for relapsed/refractory MF/SS [

15,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. In the phase II trial of vorinostat 400 mg/day in refractory MF/SS, the ORR was approximately 30%, with clinically meaningful pruritus improvement and a safety profile characterized mainly by fatigue, diarrhoea, nausea and thrombocytopenia [

45]. A larger phase IIb multicentre trial confirmed the activity and safety of vorinostat, supporting its regulatory approval [

48]. Romidepsin, evaluated in a pivotal multi-institutional phase II study, achieved an ORR of 34% (CR 6%) in heavily pretreated CTCL, with some responses lasting beyond one year [

46]. A separate multi-institutional phase II trial corroborated these findings and highlighted sustained symptom relief in a proportion of patients [

47]. Taken together, these data firmly position HDAC inhibitors as important systemic options in advanced-stage MF/SS, particularly in tumour-stage or folliculotropic disease where tumour debulking and rapid symptom control are priorities [

15,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

PI3K inhibitors and other small molecules. The PI3K–AKT axis is increasingly recognised as a pathogenic driver in CTCL, with both tumour-intrinsic and microenvironmental effects [

15,

16,

50,

51,

52,

53]. Tenalisib (RP6530), an oral dual PI3K-δ/γ inhibitor, demonstrated promising activity in a phase I/Ib study including patients with relapsed/refractory peripheral and CTCL: among evaluable CTCL patients, the ORR approached 45%, with transaminase elevations as the most common grade ≥3 adverse event [

50,

51]. In a subsequent phase I/II study combining tenalisib with romidepsin, the ORR across peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) and CTCL was approximately 60%, including durable responses in MF/SS and manageable overlapping haematologic toxicity [

52].

Duvelisib, another oral PI3K-δ/γ inhibitor, has also shown relevant activity in T-cell lymphomas. In a phase I trial, duvelisib produced an ORR of 50% in CTCL, with evidence from preclinical models that the drug not only directly kills malignant T cells but also reprograms tumour-associated macrophages from an immunosuppressive M2 phenotype to a pro-inflammatory M1 state [

15,

16,

53]. Real-world data on duvelisib combined with romidepsin suggest that this doublet is feasible and active in relapsed/refractory CTCL, supporting the rationale for PI3K–HDAC inhibitor combinations in future prospective trials [

54]. Collectively, these agents provide a therapeutic platform onto which newer immunotherapies and antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) are now being layered [

5,

15,

25,

26,

27,

45,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54].

2.4.3. Antibody–Drug Conjugates

Brentuximab vedotin in CD30-positive CTCL. Brentuximab vedotin (BV), an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody conjugated to the microtubule toxin monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE), has significantly transformed the management of CD30-positive cutaneous lymphomas. In a phase II trial of patients with CD30⁺ CTCL and lymphomatoid papulosis, BV yielded an ORR of approximately 70%, with complete responses in 16–20% of patients and meaningful improvements in pruritus and quality of life [

55]. These results have been corroborated by real-world and small-case series, including reports of rapid and deep clinical responses in primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma treated with BV [

56].

These results were confirmed and extended by the randomized phase III ALCANZA trial, which compared BV with physician’s choice (methotrexate or bexarotene) in patients with CD30-expressing MF or primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (C-ALCL) requiring systemic therapy [

57,

58]. BV significantly improved the primary endpoint of objective response lasting ≥4 months (ORR4 56.3% vs 12.5%), prolonged progression-free survival (median 16.7 vs 3.5 months; HR 0.27) and improved patient-reported symptom burden [

57,

58].

From a dermatologic viewpoint, BV’s toxicity profile is dominated by peripheral neuropathy and mild cutaneous adverse events [

15,

55,

57,

58]. The neuropathy is often cumulative but at least partially reversible; thus, early recognition, dose modification and treatment interruption are critical. Infusion-related reactions and alopecia are typically manageable. The main challenge in practice is to integrate BV into therapeutic sequences that also include skin-directed therapies—such as pairing BV with localized RT for bulky plaques or tumours—to maximize local control while limiting systemic exposure [

3,

15,

26,

27,

45,

55,

57,

58].

ADCs and payload diversification in PCBCL. In PCDLBCL-LT, antibody–drug conjugates developed for nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) are beginning to enter the cutaneous arena. Case reports and small series, often embedded within broader PCBCL reviews, describe responses to B-cell–directed ADCs (such as CD79b-targeted polatuzumab vedotin) and other novel agents in multiply relapsed PCDLBCL-LT, particularly in patients harbouring MYD88 and BCR-pathway mutations [

28,

29,

30,

32,

33,

34,

35,

65,

66,

67]. Although clinical data remain limited, the biological parallels between PCDLBCL-LT and activated B-cell-type DLBCL—especially their addiction to the BCR–MYD88–NF-κB axis—support further exploration of ADCs and related targeted approaches in this setting [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

65,

66,

67,

71].

Future ADC strategies in PCL may include CD30- or CD25-directed ADCs for transformed MF and primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas, and CD19/CD22/CD79b ADCs for relapsed PCDLBCL-LT. Payload optimisation (for example using topoisomerase-I inhibitors) may improve skin penetration and bystander killing while mitigating systemic toxicity.

2.4.4. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Other Immune Therapies

PD-1 blockade in MF and Sézary syndrome. Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are characterised by profound immune dysregulation: malignant T cells coexist with an exhausted, PD-1–high cytotoxic infiltrate and an immunosuppressive microenvironment enriched in regulatory T cells and tumour-associated macrophages [

5,

15,

16,

46,

59]. This biology provides a compelling rationale for PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. In a multicentre phase II study, pembrolizumab (200 mg every three weeks) in 24 patients with relapsed/refractory MF/SS resulted in an ORR of 38%, including two complete and seven partial responses, with some responses exceeding 12 months; activity was observed in both MF and SS [

60]. A subset of patients experienced transient “flare” reactions, with erythema and pruritus in pre-existing lesions, highlighting the importance of dermatologic expertise in distinguishing immune activation from true disease progression [

15,

60].

At a mechanistic level, single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses have shown that CTCL lesions responding to PD-1 blockade are enriched in clonally expanded, granzyme-B–positive CD8⁺ T cells and exhibit a “hot” immune cell topography, whereas non-responders display immune exclusion and enrichment of PD-L1–positive myeloid cells [

59]. These findings support combinatorial strategies (for example, with RT, HDAC or PI3K inhibitors) to remodel the tumour microenvironment and sensitise otherwise “cold” tumours to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade [

15,

16,

59]. Case reports of pembrolizumab combined with palliative radiotherapy in refractory MF further illustrate potential synergy between immune checkpoint blockade and localized radiation [

60,

61].

Early experiences with nivolumab and durvalumab in CTCL, mostly in basket trials and small series, suggest similar response rates, but also underscore the potential for immune-related adverse events (colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies), which require prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management [

15,

35].

CCR4-directed therapy: mogamulizumab. Mogamulizumab is a defucosylated humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody targeting CCR4, which is abundantly expressed on Sézary cells and on subsets of MF cells, as well as on regulatory T cells. In the phase III MAVORIC trial, mogamulizumab significantly improved progression-free survival compared with vorinostat (median 7.7 vs 3.1 months; HR 0.53) and more than quintupled the ORR (28% vs 5%) in previously treated MF/SS, with the greatest benefit seen in patients with high blood tumour burden [

62]. Post-hoc analyses confirmed that patients with B2 blood involvement derive the most pronounced benefit, reinforcing the role of detailed blood staging in therapeutic decision-making [

16,

59,

62,

63].

From a dermatologic standpoint, mogamulizumab-associated rashes are common (up to 40%), often eczematous or psoriasiform, and may histologically mimic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Interestingly, the emergence of these immune-mediated eruptions has been associated with better systemic responses, similar to observations with other immune therapies [

15,

16,

63,

64]. However, prior mogamulizumab exposure increases the risk of severe acute GVHD after allogeneic transplant, making careful timing and adequate wash-out before transplantation critical [

16,

25,

26,

27,

59].

Immune modulation in PCDLBCL-LT. PCDLBCL-LT is strongly enriched in immune-evasion mechanisms, including overexpression of PD-L1/PD-L2 and recurrent alterations in antigen presentation pathways [

30,

31,

32,

34,

35]. Small series suggest that integrating PD-1 blockade into salvage regimens can achieve meaningful responses. A case series combining rituximab, lenalidomide and pembrolizumab in multiply relapsed PCDLBCL-LT reported durable complete responses in patients who had progressed after R-CHOP and radiotherapy [

66]. Another cohort treated with rituximab, lenalidomide and ibrutinib achieved high response rates with acceptable toxicity, suggesting that dual immunomodulation plus BTK inhibition can re-sensitize chemoresistant disease [

67]. These experiences, together with mechanistic data on PD-L1/PD-L2 expression and MYD88/BCR pathway activation, support a conceptual shift in PCDLBCL-LT from purely cytotoxic approaches toward immune- and pathway-directed combinations [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

65,

66,

67].

2.4.5. Other Emerging Targeted and Immune Strategies in CTCL

The therapeutic landscape of CTCL is rapidly expanding beyond HDAC and PI3K inhibitors. Hyperactivation of JAK/STAT and SYK signalling is a hallmark of many T-cell lymphomas, including CTCL, often driven by autocrine and paracrine cytokine loops [

15,

16]. Cerdulatinib, a dual SYK/JAK inhibitor, has produced ORRs of roughly one-third in relapsed/refractory peripheral and cutaneous T-cell lymphomas in early-phase studies, with particularly encouraging responses in T-follicular helper–type nodal lymphomas and symptom relief (notably pruritus) in CTCL patients [

15]. Although still investigational, such data highlight cytokine and BCR-proximal signalling as promising therapeutic targets.

Preclinical models suggest that HDAC inhibition can increase tumour immunogenicity by upregulating MHC and co-stimulatory molecules, potentially enhancing sensitivity to PD-1 blockade [

15,

16,

46,

48,

49]. Clinically, combinations of HDAC inhibitors (romidepsin or vorinostat) with PI3K inhibitors (tenalisib, duvelisib) are emerging in early-phase trials and real-world series, where they appear to deepen responses compared with either agent alone, albeit at the cost of increased haematologic toxicity and infectious risk [

15,

16,

50,

51,

53,

54]. Frequent dermatologic assessment is essential to distinguish drug-related exanthems and immune phenomena from CTCL progression.

Allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation remains the only established curative-intent strategy for advanced MF/SS, with registry data showing long-term disease control in a subset of high-risk patients but at the price of significant transplant-related morbidity and mortality [

14,

20,

21,

25,

26,

27]. Early-phase trials of CD30-targeted and CD5-directed CAR-T cells in T-cell lymphomas have demonstrated proof-of-concept responses, including in CTCL, but issues such as fratricide, prolonged T-cell aplasia and antigen-negative relapse remain major challenges [

15].

Innate immune engagement and macrophage reprogramming are also emerging as therapeutic concepts. Preclinical data indicate that agents targeting the CD47–SIRPα “don’t-eat-me” axis and PI3K-δ/γ can re-educate tumour-associated macrophages and enhance phagocytosis of CTCL cells [

15,

16,

51,

52,

53]. Early-phase clinical trials of anti-CD47 antibodies and SIRPα-Fc fusion proteins in T-cell lymphomas will provide critical insights; dermatologic endpoints—such as ulceration, re-epithelialisation and inflammation in heavily infiltrated plaques—are likely to be particularly informative in CTCL.

2.4.6. Novel Strategies in Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas

Lenalidomide and immunomodulation in PCDLBCL-LT. Lenalidomide has emerged as a rational partner for rituximab in PCDLBCL-LT, leveraging both direct anti-lymphoma effects and T-cell/macrophage activation [

26,

28,

29,

30,

31,

65,

66]. In a multicentre, single-arm phase II trial of relapsed/refractory PCDLBCL-LT, lenalidomide monotherapy achieved an ORR of 26% at six months, with some durable complete remissions in an elderly, frail population; cytopenias and infections were the main toxicities [

65]. Real-world case reports confirm the activity of lenalidomide, including impressive responses after multiple prior lines of therapy and in combination with rituximab, supporting its use as a palliative yet potentially disease-modifying option in selected patients [

65,

66,

68].

BTK inhibition and BCR–MYD88 pathway targeting. PCDLBCL-LT is characterised by high frequencies of MYD88 L265P and CD79B mutations, underpinning dependence on chronic active BCR signalling and NF-κB activation [

29,

30,

31,

32,

34,

35]. This biology translates into clinical sensitivity to BTK inhibition. A landmark case report of low-dose ibrutinib documented a rapid and deep remission in a patient with PCDLBCL-LT harbouring MYD88 and CD79B mutations, after failure of anthracycline-based therapy and lenalidomide [

71]. Subsequent small series combining rituximab, lenalidomide and ibrutinib in relapsed/refractory PCDLBCL-LT reported high response rates with acceptable tolerability, suggesting that simultaneous BCR blockade and immunomodulation may overcome chemoresistance in some patients [

67,

68].

Mechanistic work has also shown that, under ibrutinib pressure, PCDLBCL-LT can acquire additional mutations in genes such as PIM1 and other downstream effectors, providing insights into mechanisms of secondary resistance and pointing to potential combinational strategies with PIM1 or NF-κB inhibitors [

34,

35,

36].

Checkpoint blockade and microenvironmental targeting. Genomic and immunohistochemical studies demonstrate frequent loss-of-function alterations in antigen-presentation genes (for example, B2M), high PD-L1/PD-L2 expression and a complex immune microenvironment in PCDLBCL-LT, often with abundant PD-L1–positive macrophages [

29,

30,

31,

32,

34,

35].These features support the use of checkpoint inhibitors, particularly in biologically selected patients and in combination regimens. The combination of rituximab, lenalidomide and pembrolizumab has generated durable complete responses in patients with refractory PCDLBCL-LT who had previously failed multiple lines of chemo-immunotherapy and radiotherapy [

66]. Although numbers remain small, these observations hint at a therapeutic paradigm in which immune-directed combinations—rather than purely cytotoxic escalation—become the preferred salvage strategy in selected patients [

4,

26,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

66].

High-level PCBCL perspectives. Recent comprehensive reviews and molecular studies emphasise that PCBCL management is moving toward biologically tailored regimens for PCDLBCL-LT based on BCR/MYD88 mutation status and immune-evasion signatures; de-escalation of systemic therapy in indolent PCBCL using localised RT, intralesional agents and conservative systemic regimens; and integration of targeted agents (lenalidomide, BTK inhibitors and potentially BCL2 and EZH2 inhibitors) for relapse and peri-transplant management [

4,

26,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

65]. For dermatologists, this evolution underscores the importance of high-quality diagnostic biopsies (including molecular profiling), long-term surveillance for relapse and close partnership with lymphoma centres experienced in rare cutaneous entities.

These therapeutic principles are summarised schematically in

Figure 2.

In MF and SS, early disease is treated with skin-directed therapies, while advanced stages require sequential systemic treatments, with allogeneic stem-cell transplantation reserved for selected aggressive or refractory cases [

5,

23,

24,

26].

In PCBCLs, indolent subtypes (PCFCL, PCMZL/LPD) respond well to localized radiotherapy or excision and have excellent outcomes, whereas PCDLBCL-LT is aggressive and typically requires anthracycline-based immunochemotherapy, with growing use of immunomodulatory and BCR/BTK-targeted therapies in relapse [

3,

28,

29,

65,

66,

67].

3. Discussion

Primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCLs) constitute a clinically and biologically heterogeneous group of lymphoid neoplasms that increasingly require molecularly informed diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Advances in sequencing technologies and high-dimensional immune profiling have clarified central pathogenic mechanisms in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL), including dysregulated TCR signalling, JAK/STAT activation, PI3K pathway involvement and robust immune-evasion programs, which help explain treatment resistance, blood involvement and the immunosuppressive microenvironment characteristic of advanced MF and Sézary syndrome (SS) [

1,

6,

11,

12].

In primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (PCBCL), and especially in primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (PCDLBCL-LT), recurrent MYD88 L265P and CD79B mutations and alterations in antigen-presentation genes establish a biologic profile deeply reliant on BCR–NF-κB signalling and enriched in immune-escape signatures [

30,

32,

34,

35]. These insights increasingly guide not only prognosis but also therapeutic selection, supporting the use of BTK inhibitors, lenalidomide-containing regimens and emerging checkpoint-based combinations [

65,

66,

67,

71].

Despite these advances, diagnostic delay remains a pervasive issue, particularly in early MF, where clinical overlap with benign dermatoses and subtle early histopathology frequently hinder timely recognition [

18,

19,

69]. Dermatologists remain central in identifying persistent or atypical dermatoses, coordinating repeat biopsies and incorporating molecular testing when indicated [

13,

26]. Accurate subclassification of PCBCL is equally essential: while PCFCL and PCMZL typically benefit from conservative, skin-directed approaches, PCDLBCL-LT mandates systemic therapy informed by its aggressive molecular profile [

28,

29,

30].

Therapeutically, the landscape for CTCL continues to broaden. Skin-directed therapy remains foundational in early MF, with chlormethine gel demonstrating consistent efficacy across randomised and real-world settings, and mechanistic studies suggesting additional immunogenic effects beyond direct alkylation [

37,

38,

39]. Systemic therapies—ranging from bexarotene to extracorporeal photopheresis, HDAC inhibitors and PI3K inhibitors—offer varied benefits depending on disease stage, burden and symptom profile [

15,

25,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. HDAC inhibitors, such as vorinostat and romidepsin, retain particular value in tumour-stage or folliculotropic MF, and early-phase data support the synergistic potential of combinations with PI3K inhibitors [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Brentuximab vedotin (BV) represents one of the most significant therapeutic advances in CD30-positive CTCL, with the ALCANZA trial demonstrating superior and durable responses compared with physician’s choice, along with meaningful symptom improvement [

55,

56,

57,

58]. Its activity in primary cutaneous ALCL is further supported by case-based evidence [

56], though peripheral neuropathy remains a major dose-limiting toxicity. Immunotherapy has also expanded treatment options: pembrolizumab provides durable benefit in a subset of MF/SS patients [

60], and immune-topographic profiling has begun to identify microenvironmental signatures predictive of response [

59]. However, immune-related adverse events and flare reactions require careful dermatologic assessment to avoid misinterpretation as progression [

22,

24].

Immune-directed strategies extend to mogamulizumab, which shows substantial benefit—particularly in SS with high blood tumour burden—but its association with drug-related rashes and increased risk of post-transplant GVHD demands careful sequencing, especially in transplant-eligible patients [

62,

63,

64].

In PCDLBCL-LT, combinations such as rituximab–lenalidomide–pembrolizumab and rituximab–lenalidomide–ibrutinib have shown encouraging activity in relapsed settings, reinforcing the role of immunomodulation and targeted therapy in a disease with limited chemoresponsiveness [

65,

66,

67,

71]. Mechanistic studies describing ibrutinib-induced resistance via PIM1 and related pathways suggest avenues for future rational combinations with downstream inhibitors [

36].

Looking ahead, biomarker-driven treatment selection remains underdeveloped across both CTCL and PCBCL. Integrating spatial transcriptomics, immune-phenotyping and genomic profiling may improve prediction of responsiveness to HDAC inhibitors, PI3K inhibitors and checkpoint blockade. Reducing diagnostic delay—particularly in early MF—will require standardized dermatologic algorithms and development of non-invasive molecular tools [

18,

22].

Trials exploring rational therapeutic combinations and optimal sequencing are urgently needed, as are more robust translational models that reflect the unique biology of cutaneous lymphomas. As therapeutic options expand, multidisciplinary collaboration across dermatology, haematology, pathology, immunology and computational biology will become increasingly essential. Overall, the rapidly expanding therapeutic armamentarium offers genuine potential to improve outcomes in PCL, though personalization of therapy remains the central challenge.

The principal clinical, translational and molecular studies informing current practice in PCL are summarised in

Table 2.

4. Materials and Methods

This manuscript was prepared as a narrative review synthesising current evidence on the biology, diagnosis and management of primary cutaneous lymphomas. A structured, non-systematic search of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase and Web of Science was performed from database inception through March 2025, using combinations of keywords related to CTCL (e.g., mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), PCBCL (e.g., PCFCL, PCMZL, PCDLBCL-LT), pathogenesis (JAK/STAT, MYD88, CD79B, TCR signalling, epigenetics) and treatment (chlormethine, bexarotene, HDAC inhibitors, PI3K inhibitors, brentuximab vedotin, mogamulizumab, pembrolizumab, lenalidomide, ibrutinib). Reference lists of pivotal clinical trials, molecular studies and major reviews were examined for additional sources.

Eligible publications included clinical trials, prospective and retrospective cohorts, translational studies, case series with mechanistic relevance and authoritative consensus guidelines. We excluded non–peer-reviewed material and reports unrelated to cutaneous disease. Study characteristics and findings were extracted manually and synthesised narratively; no meta-analysis or quantitative pooling was undertaken.

No new data were generated and no human, animal or institutional datasets were collected; therefore, ethics approval was not required. All information derives from publicly available peer-reviewed literature. In accordance with journal guidelines, we disclose that generative AI tools were used only for language refinement under direct author supervision, and all scientific interpretations, literature selection and synthesis were performed solely by the authors.

5. Conclusions

Primary cutaneous lymphomas require nuanced, multidisciplinary and stage-specific management. Advances in genomic profiling and immune characterization have refined diagnostic criteria and therapeutic decision-making, particularly in MF/SS and PCDLBCL-LT [

6,

8,

14,

15,

24,

30,

31,

32,

35]. Novel systemic agents—including PI3K and HDAC inhibitors, brentuximab vedotin, mogamulizumab, immunomodulatory drugs and checkpoint inhibitors—have expanded treatment options and improved outcomes in selected patients [

15,

20,

25,

40,

45,

47,

57,

60,

63,

64].

Future progress will rely on biomarker-guided therapy, rational combination strategies and deeper integration of molecular diagnostics into routine dermatologic practice. Because the skin provides unparalleled access for serial tissue analysis, dermatologists will continue to play a central role in advancing precision medicine for these rare lymphomas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, O.C.; software, V.P.; validation, S.R. and P.Q.; investigation, C.S.; resources, M.A.; data curation, O.C.; writing—original draft preparation, O.C.; writing—review and editing, O.C.; visualization, F.R.; supervision, F.R. and U.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- R. Willemze et al., “The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas,” Blood, vol. 133, no. 16, pp. 1703–1714, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Campo et al., “The International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms: a report from the Clinical Advisory Committee,” Blood, vol. 140, no. 11, pp. 1229–1253, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Hristov, T. Tejasvi, and R. A. Wilcox, “Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management,” Am J Hematol, vol. 98, no. 8, pp. 1326–1332, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. R. Barbati and Y. Charli-Joseph, “Unveiling Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas: New Insights into Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 17, no. 7, p. 1202, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Hristov, T. Tejasvi, and R. A. Wilcox, “Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: 2021 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management,” Am J Hematol, vol. 96, no. 10, pp. 1313–1328, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. García-Díaz, M. Á. Piris, P. L. Ortiz-Romero, and J. P. Vaqué, “Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome: An Integrative Review of the Pathophysiology, Molecular Drivers, and Targeted Therapy,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 8, p. 1931, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Krenitsky, S. Klager, L. Hatch, C. Sarriera-Lazaro, P. L. Chen, and L. Seminario-Vidal, “Update in Diagnosis and Management of Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas,” Am J Clin Dermatol, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 689–706, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Walia and C. C. S. Yeung, “An Update on Molecular Biology of Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma,” Front Oncol, vol. 9, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Laurent, J. R. Cook, T. Yoshino, L. Quintanilla-Martinez, and E. S. Jaffe, “Follicular lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma: how many diseases?,” Virchows Archiv, vol. 482, no. 1, pp. 149–162, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Alaggio et al., “The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms,” Leukemia, vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 1720–1748, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Jones et al., “Spectrum of mutational signatures in T-cell lymphoma reveals a key role for UV radiation in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma,” Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 3962, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, X. Wu, S. T. Hwang, and J. Liu, “The Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome,” Ann Dermatol, vol. 33, no. 6, p. 487, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Gibbs et al., “Utility of flow cytometry and gene rearrangement analysis in tissue and blood of patients with suspected cutaneous T-cell lymphoma,” Oncol Rep, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 349–358, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. S. Agar et al., “Survival Outcomes and Prognostic Factors in Mycosis Fungoides/Sézary Syndrome: Validation of the Revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Staging Proposal,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 28, no. 31, pp. 4730–4739, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. Stuver and A. J. Moskowitz, “Therapeutic Advances in Relapsed and Refractory Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 3, p. 589, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Guglielmo, C. Zengarini, C. Agostinelli, G. Motta, E. Sabattini, and A. Pileri, “The Role of Cytokines in Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma: A Focus on the State of the Art and Possible Therapeutic Targets,” Cells, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 584, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Pileri et al., “Epidemiology of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: state of the art and a focus on the Italian Marche region,” European Journal of Dermatology, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 360–367, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Scarisbrick et al., “The PROCLIPI international registry of early-stage mycosis fungoides identifies substantial diagnostic delay in most patients,” British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 181, no. 2, pp. 350–357, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Geller et al., “Outcomes and prognostic factors in African American and black patients with mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: Retrospective analysis of 157 patients from a referral cancer center,” J Am Acad Dermatol, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 430–439, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Scarisbrick et al., “Cutaneous Lymphoma International Consortium Study of Outcome in Advanced Stages of Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome: Effect of Specific Prognostic Markers on Survival and Development of a Prognostic Model,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 33, no. 32, pp. 3766–3773, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Scarisbrick et al., “Prognostic factors, prognostic indices and staging in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: where are we now?,” British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 170, no. 6, pp. 1226–1236, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. D’Onghia et al., “Non-Invasive Imaging Including Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography (LC-OCT) for Diagnosis of Cutaneous Lymphomas,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 16, no. 21, p. 3608, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Olsen et al., “Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC),” Blood, vol. 110, no. 6, pp. 1713–1722, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. Latzka et al., “EORTC consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome – Update 2023,” Eur J Cancer, vol. 195, p. 113343, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Giordano and L. Pagano, “THE TREATMENT OF ADVANCED-STAGE MYCOSIS FUNGOIDES AND SEZARY SYNDROME: A HEMATOLOGIST’S POINT OF VIEW.,” Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis, vol. 14, no. 1, p. e2022029, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Mehta-Shah et al., “NCCN Guidelines Insights: Primary Cutaneous Lymphomas, Version 2.2020,” Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 522–536, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Trautinger et al., “EORTC consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome,” Eur J Cancer, vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 1014–1030, May 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Dumont, M. Battistella, C. Ram-Wolff, M. Bagot, and A. de Masson, “Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas: State of the Art and Perspectives,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 6, p. 1497, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Grange et al., “Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type,” Arch Dermatol, vol. 143, no. 9, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Lucioni et al., “Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma: An Update on Pathologic and Molecular Features,” Hemato, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 318–340, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Vitiello, A. Sica, A. Ronchi, S. Caccavale, R. Franco, and G. Argenziano, “Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas: An Update,” Front Oncol, vol. 10, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, T. M. LeWitt, A. Louissaint, J. Guitart, X. A. Zhou, and J. Choi, “Disease-Defining Molecular Features of Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas: Implications for Classification and Treatment,” Journal of Investigative Dermatology, vol. 143, no. 2, pp. 189–196, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Villasenor-Park, J. Chung, and E. J. Kim, “Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas,” Hematol Oncol Clin North Am, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 1111–1131, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Pham-Ledard et al., “High Frequency and Clinical Prognostic Value of MYD88 L265P Mutation in Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg-Type,” JAMA Dermatol, vol. 150, no. 11, p. 1173, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. A. Zhou et al., “Genomic Analyses Identify Recurrent Alterations in Immune Evasion Genes in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type,” Journal of Investigative Dermatology, vol. 138, no. 11, pp. 2365–2376, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Fox et al., “Molecular Mechanisms of Disease Progression in Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type during Ibrutinib Therapy,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 19, no. 6, p. 1758, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Lessin et al., “Topical Chemotherapy in Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma,” JAMA Dermatol, vol. 149, no. 1, p. 25, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. V. Alexander-Savino, C. G. Chung, E. S. Gilmore, S. M. Carroll, and B. Poligone, “Randomized Mechlorethamine/Chlormethine Induced Dermatitis Assessment Study (MIDAS) Establishes Benefit of Topical Triamcinolone 0.1% Ointment Cotreatment in Mycosis Fungoides,” Dermatol Ther (Heidelb), vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 643–654, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Guenova, P. L. Ortiz-Romero, B. Poligone, and C. Querfeld, “Mechanism of action of chlormethine gel in mycosis fungoides,” Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, vol. 37, no. 9, pp. 1739–1748, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Duvic et al., “Bexarotene Is Effective and Safe for Treatment of Refractory Advanced-Stage Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma: Multinational Phase II-III Trial Results,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 2456–2471, May 2001. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Zic et al., “Long-term follow-up of patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma treated with extracorporeal photochemotherapy,” J Am Acad Dermatol, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 935–945, Dec. 1996. [CrossRef]

- R. Knobler et al., “Long-term follow-up and survival of cutaneous T -cell lymphoma patients treated with extracorporeal photopheresis,” Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 250–257, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. Quaglino et al., “Extracorporeal photopheresis for the treatment of erythrodermic cutaneous T -cell lymphoma: a single center clinical experience with long-term follow-up data and a brief overview of the literature,” Int J Dermatol, vol. 52, no. 11, pp. 1308–1318, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Cho, C. Jantschitsch, and R. Knobler, “Extracorporeal Photopheresis—An Overview,” Front Med (Lausanne), vol. 5, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Duvic et al., “Phase 2 trial of oral vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, SAHA) for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL),” Blood, vol. 109, no. 1, pp. 31–39, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Whittaker et al., “Final Results From a Multicenter, International, Pivotal Study of Romidepsin in Refractory Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 28, no. 29, pp. 4485–4491, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Piekarz et al., “Phase II Multi-Institutional Trial of the Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Romidepsin As Monotherapy for Patients With Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 27, no. 32, pp. 5410–5417, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Olsen et al., “Phase IIB Multicenter Trial of Vorinostat in Patients With Persistent, Progressive, or Treatment Refractory Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 25, no. 21, pp. 3109–3115, Jul. 2007. [CrossRef]

- B. S. Mann, J. R. Johnson, M. H. Cohen, R. Justice, and R. Pazdur, “FDA Approval Summary: Vorinostat for Treatment of Advanced Primary Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma,” Oncologist, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 1247–1252, Oct. 2007. [CrossRef]

- A. Huen et al., “Phase I/Ib Study of Tenalisib (RP6530), a Dual PI3K δ/γ Inhibitor in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory T-Cell Lymphoma,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 8, p. 2293, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Carlo-Stella et al., “A First-in-human Study of Tenalisib (RP6530), a Dual PI3K δ/γ Inhibitor, in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Hematologic Malignancies: Results From the European Study,” Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 78–86, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Iyer et al., “Safety and efficacy of tenalisib in combination with romidepsin in patients with relapsed/refractory T-cell lymphoma: results from a phase I/II open-label multicenter study,” Haematologica, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Horwitz et al., “Activity of the PI3K-δ,γ inhibitor duvelisib in a phase 1 trial and preclinical models of T-cell lymphoma,” Blood, vol. 131, no. 8, pp. 888–898, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Ford et al., “Real-world evidence of duvelisib and romidepsin in relapsed/refractory peripheral and cutaneous T-cell lymphomas,” Blood Adv, vol. 9, no. 16, pp. 4286–4305, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Duvic, M. T. Tetzlaff, P. Gangar, A. L. Clos, D. Sui, and R. Talpur, “Results of a Phase II Trial of Brentuximab Vedotin for CD30 + Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma and Lymphomatoid Papulosis,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 33, no. 32, pp. 3759–3765, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Ferreira, I. Fernandes, R. Cabral, and M. Lima, “Tratamento do Linfoma Cutâneo Primário de Células Grandes Anaplásicas com Brentuximab Vedotina: A Propósito de Dois Casos Clínicos,” Journal of the Portuguese Society of Dermatology and Venereology, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 53–56, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Prince et al., “Brentuximab vedotin or physician’s choice in CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (ALCANZA): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, multicentre trial,” The Lancet, vol. 390, no. 10094, pp. 555–566, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Horwitz et al., “Randomized phase 3 ALCANZA study of brentuximab vedotin vs physician’s choice in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: final data,” Blood Adv, vol. 5, no. 23, pp. 5098–5106, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Phillips et al., “Immune cell topography predicts response to PD-1 blockade in cutaneous T cell lymphoma,” Nat Commun, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 6726, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Khodadoust et al., “Pembrolizumab in Relapsed and Refractory Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome: A Multicenter Phase II Study,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 20–28, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Walker et al., “Pembrolizumab and palliative radiotherapy in 2 cases of refractory mycosis fungoides,” JAAD Case Rep, vol. 7, pp. 87–90, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Kim et al., “Mogamulizumab versus vorinostat in previously treated cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (MAVORIC): an international, open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial,” Lancet Oncol, vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 1192–1204, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Cowan et al., “Efficacy and safety of mogamulizumab by patient baseline blood tumour burden: a post hoc analysis of the MAVORIC trial,” Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, vol. 35, no. 11, pp. 2225–2238, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Fernández-Guarino, P. Ortiz, F. Gallardo, and M. Llamas-Velasco, “Clinical and Real-World Effectiveness of Mogamulizumab: A Narrative Review,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 4, p. 2203, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Beylot-Barry et al., “A Single-Arm Phase II Trial of Lenalidomide in Relapsing or Refractory Primary Cutaneous Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type,” Journal of Investigative Dermatology, vol. 138, no. 9, pp. 1982–1989, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Di Raimondo, F. R. Abdulla, J. Zain, C. Querfeld, and S. T. Rosen, “Rituximab, lenalidomide and pembrolizumab in refractory primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type,” Br J Haematol, vol. 187, no. 3, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Moore et al., “Rituximab, lenalidomide, and ibrutinib in relapsed/refractory primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type,” Br J Haematol, vol. 196, no. 4, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Al Dhafiri et al., “Effectiveness of lenalidomide in relapsed primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type,” Clin Case Rep, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 964–967, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Pulitzer, “Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma,” Clin Lab Med, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 527–546, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Kempf et al., “EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma*,” Blood, vol. 118, no. 15, pp. 4024–4035, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Pang, R. Au-Yeung, R. Y. Y. Leung, and Y.-L. Kwong, “Addictive response of primary cutaneous diffuse large B cell lymphoma leg type to low-dose ibrutinib,” Ann Hematol, vol. 98, no. 10, pp. 2433–2436, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).