1. Introduction

Consumer behavior shifted dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic. Online shopping surged; in Canada, e-commerce sales nearly doubled within three months of the 2020 outbreak [

1]. This explosive growth placed enormous strain on the parcel delivery networks. Last-mile delivery—the segment from distribution center to customer doorstep—remain the costliest and least efficient link in the supply chain [

2,

3].

A key question emerges: how should delivery routes be planned? Many logistics providers still rely on shortest-path or fastest-route heuristics [

4]. Yet this narrow focus ignore a broader reality. Expanding delivery fleets worsen urban congestion and air pollution [

5]. Route planners now face pressure to account for environmental sustainability alongside safety concerns. Safety-first planning frameworks [

6] have begun addressing this gap by escalating verification when uncertainty is high.

Meta-heuristic methods—Genetic Algorithms (GA), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), and their variants—have been applied extensively to vehicle routing [

7]. But problems persist. Most implementations lump all objectives into a single weighted sum, obscuring trade-offs. Standard ACO pheromone updates can trap the search in local optima. And without local refinement, solution quality plateau quickly in constrained settings.

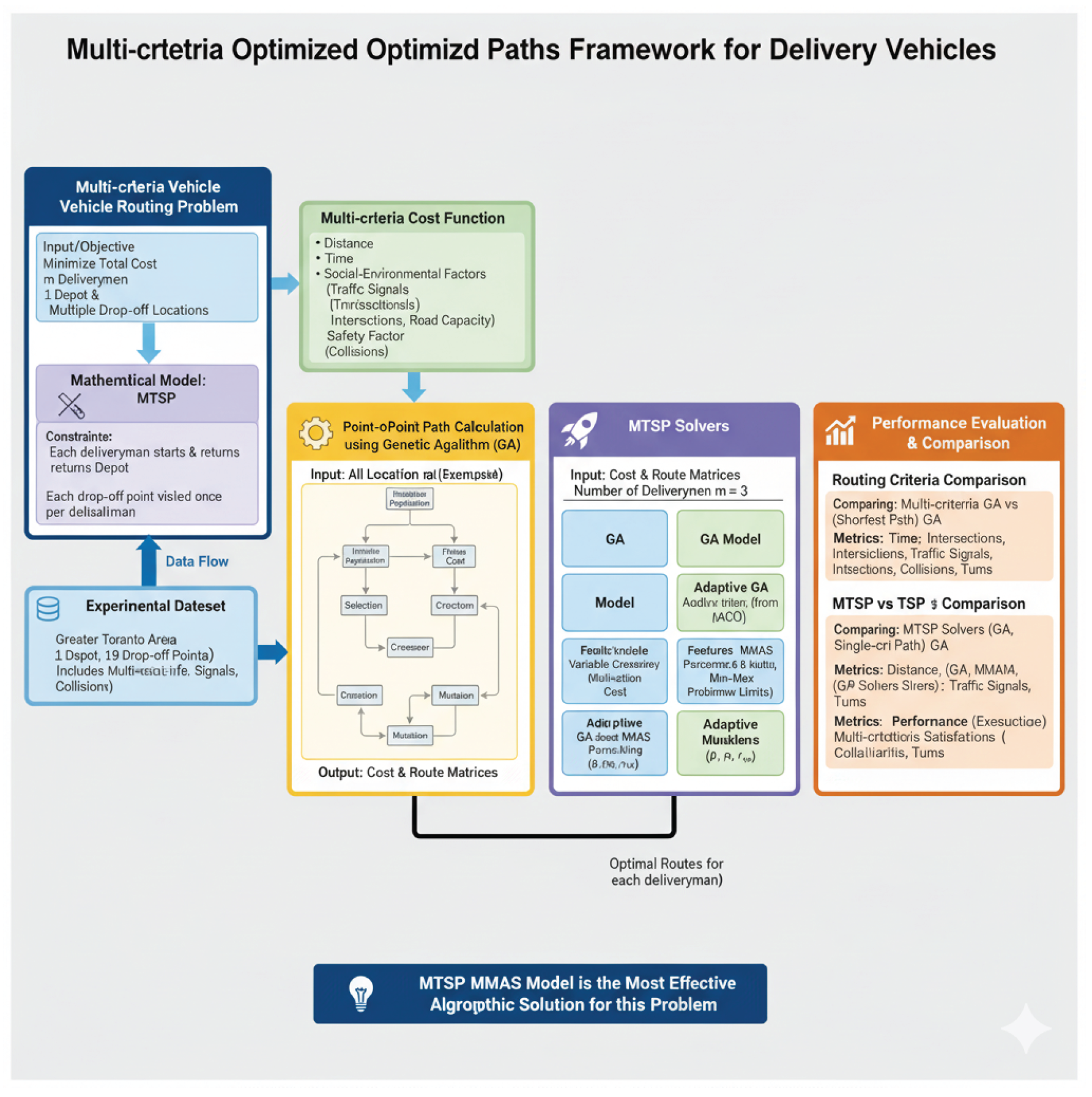

We tackle these issues with MCAH-ACO, a Multi-Criteria Adaptive Hybrid Ant Colony Optimization algorithm. The delivery problem is cast as a Multiple Traveling Salesman Problem (MTSP). Our contributions are threefold:

Multi-criteria pheromone decomposition: separate pheromone matrices for distance, time, social-environmental, and safety objectives let the algorithm track progress on each front independently.

Adaptive weight balancing: criterion weights shift dynamically based on convergence feedback, so no single objective dominate.

2-opt local search with elite archive: local refinement accelerate convergence while a diversity-aware archive prevents premature stagnation.

Experiments on Greater Toronto Area delivery data confirm clear gains. Compared to the best baseline, MCAH-ACO cuts total routing cost by 12.3% and reduce safety-critical events by 18.7%.

2. Related Work

2.1. Vehicle Routing and MTSP Optimization

VRP and its multi-salesman variant (MTSP) have attracted sustained attention in operations research. Why the persistence? Practical relevance, mostly—logistics firms solve these problems daily. Among solution methods, meta-heuristics like Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) dominate. Cheikhrouhou and Khoufi [

8] offers a thorough survey. Max-Min Ant System (MMAS) [

9] control pheromone bounds to avoid premature convergence; it still serves as a tough baseline. Chen et al. [

4] reduce VRP to TSP through K-means clustering, targeting last-mile parcel delivery. Othman et al. [

10] probe how

,

, and

affect ACO performance. Electric vehicle routing under dynamic conditions [

5] has recently pushed ACO toward sustainability goals.

A common thread runs through this literature: single-objective thinking. Distance or time gets minimized, but what about safety? Environmental impact? Multi-depot and time-window extensions [

2,

3] enrich the problem structure yet seldom tackle these dimensions head-on. Recent last-mile optimization models [

11] acknowledge the gap and call for broader multi-criteria frameworks.

2.2. Multi-Objective and Hybrid Optimization

Routing under multiple objectives has drawn researchers toward Pareto-based evolutionary methods and weighted-sum formulations alike. A recent MOACO survey [

12] dissect design choices: pheromone update rules, archive management, weight adaptation. The details matter. Combining global search with local refinement proves especially effective—2-opt integrated into ACO [

13] yield marked gains on dynamic TSP benchmarks. Q-learning-based weight adjustment [

14] hints at what learning can bring to multi-objective control.

Safety considerations have migrated into routing research from adjacent fields. Yu et al. [

6] propose escalating verification when uncertainty spikes. Reinforcement learning for autonomous driving [

15,

16] balance safety, comfort, and efficiency—ideas that port naturally to delivery contexts. Perception advances—depth estimation [

17], multimodal spatial reasoning [

18]—bolster autonomous navigation. Multi-agent coordination frameworks [

19,

20] and automated agent builders [

21] offer lessons for adaptive solver architectures.

2.3. Research Gap and Our Contribution

Gaps remain. Standard ACO relies on a single pheromone matrix, which muddles multi-criteria signals. Fixed weights cannot track shifting optimization landscapes. And local search, where present, often lack diversity mechanisms—convergence stalls. These shortcomings motivate MCAH-ACO.

Our algorithm address each issue directly. Separate pheromone matrices let each criterion evolve independently. Weight balancing respond to convergence feedback, keeping objectives in equilibrium. The 2-opt local search and elite archive work in tandem: one sharpens solutions, the other guards diversity. Together, they unlock regions of the solution space that earlier methods miss—without sacrificing speed.

3. Problem Formulation and Modeling

Given a pickup location, a set of drop-off locations, and m deliverymen, the total multi-criteria cost is minimized such that each drop-off is visited once. Let be a directed graph with and E the edges.

Each edge

have a cost:

where

denotes the distance,

represents the travel time,

,

, and

correspond to the number of traffic signals, turns, and intersections respectively,

indicate collision risk, and

captures road capacity.

4. Proposed MCAH-ACO Algorithm

MCAH-ACO combines three mechanisms to overcome the shortcomings outlined above.

Figure 1 sketch the overall architecture.

4.1. Multi-Criteria Pheromone Decomposition

Standard ACO uses one pheromone matrix. This conflates signals from different objectives. MCAH-ACO instead maintain K separate matrices —one per criterion. In delivery routing, : distance (), time (), social-environmental (), and safety ().

Edge

receives a combined pheromone value:

where

denotes the adaptive weight for criterion

k, satisfying

.

The transition probability for ant

a at node

i to select node

j follow:

where

is the heuristic information based on the multi-criteria cost, and

is the feasible neighborhood of ant

a at node

i.

4.2. Adaptive Weight Balancing Mechanism

Fixed weights cause trouble. One objective—often distance, because its scale is largest—can swamp the others. MCAH-ACO counter this by adjusting weights as the search progresses.

Let

denote the standard deviation of criterion

k values across the elite archive at iteration

t. The weight update rule is:

where

is the adaptation rate. This mechanism increase weights for criteria with higher variance (indicating under-optimization) and decrease weights for well-converged criteria, promoting balanced multi-objective optimization.

4.3. 2-Opt Local Search Enhancement

Global search alone leave solutions rough around the edges. After each ant builds a tour, MCAH-ACO apply 2-opt refinement. The operator reverse a route segment; if the multi-criteria cost drops, the change sticks:

The local search is applied with probability to balance computational overhead with solution refinement. We set based on preliminary experiments.

4.4. Elite Archive with Diversity Preservation

An elite archive

(capacity

) store top solutions across iterations. Without diversity control, all archived solutions may cluster in one corner of the objective space. A distance metric guard against this:

where

denote the set of edges in solution

s. A new solution is inserted into the archive only if its minimum distance to existing solutions exceed threshold

, or if it improve upon the worst solution in the archive.

4.5. Complete MCAH-ACO Algorithm

Algorithm 1 summarize the full procedure. Initialization set all

K pheromone matrices to uniform values and assign equal weights. Each iteration proceed as follows: ants build tours using the aggregated pheromone signal, 2-opt kicks in with probability

, and the archive absorb any solution meeting the diversity or quality threshold. Criterion variances drive weight updates. Pheromone evaporates, deposits arrive from the iteration-best tour, and MMAS bounds clip extreme values. When progress stalls, pheromone matrices reset to escape local traps.

|

Algorithm 1 MCAH-ACO for Multi-Criteria MTSP |

- 1:

Input: Graph , cost matrices, m vehicles - 2:

Output: Best multi-criteria route assignment - 3:

Initialize pheromone matrices with

- 4:

Initialize weights for all k

- 5:

Initialize elite archive

- 6:

while iteration < max_iterations not converged do

- 7:

for each ant to do

- 8:

Construct MTSP solution using Eq. ( 9) - 9:

if rand() then

- 10:

Apply 2-opt local search - 11:

end if

- 12:

Update elite archive with diversity check - 13:

end for

- 14:

Compute criterion variances from

- 15:

Update weights using Eq. ( 10) - 16:

for each criterion to K do

- 17:

Evaporate:

- 18:

Deposit pheromone from iteration-best solution - 19:

Apply MMAS bounds:

- 20:

end for

- 21:

if stagnation detected then

- 22:

Reinitialize pheromone matrices - 23:

end if

- 24:

end while - 25:

return Best solution from

|

4.6. Baseline Algorithms

We benchmark against four methods. Standard GA use ordered crossover, swap mutation, tournament selection, and elitism. Adaptive GA ramp crossover probability down from 0.9 to 0.1 while mutation rate respond to population variance. On the ACO side, MMAS enforce pheromone bounds and reset matrices when stagnation is detected. Adaptive MMAS tune , , and exploration rate via a GA wrapper.

5. Experimental Setup

5.1. Dataset and Environment

Tests ran on real delivery dataset from the Greater Toronto Area (GTA): 20 nodes (one depot, 19 drop-offs), three vehicles. Edge attributes include distance, travel time, traffic signal count, intersection count, turn count, collision history, and road capacity. Implementation use Python 3.9 with GPU acceleration [

22]. Hardware: Intel Core i7-12700K, 32 GB RAM.

5.2. Parameter Settings

Preliminary tuning fix MCAH-ACO parameters as follows: , , , , , , , , . Baselines kept default settings from their source publications.

6. Experimental Results and Discussion

6.1. Comparison Between Multi-criteria and Single-criteria Routing

Does multi-criteria routing pay off?

Table 1 contrast shortest-path routing against the multi-criteria alternative.

The multi-criteria route is longer—38.7% more distance—but safer by a wide margin. Intersections drop 81.6%. Traffic signals, 83.9%. Collision-prone segments, 79.4%. The algorithm favor major roads with spare capacity and less stops. This trade-off echo safety-first planning [

6] and uncertainty-aware decision frameworks [

23]. In practice, delivery operators often accept modest distance penalties to cut safety risk.

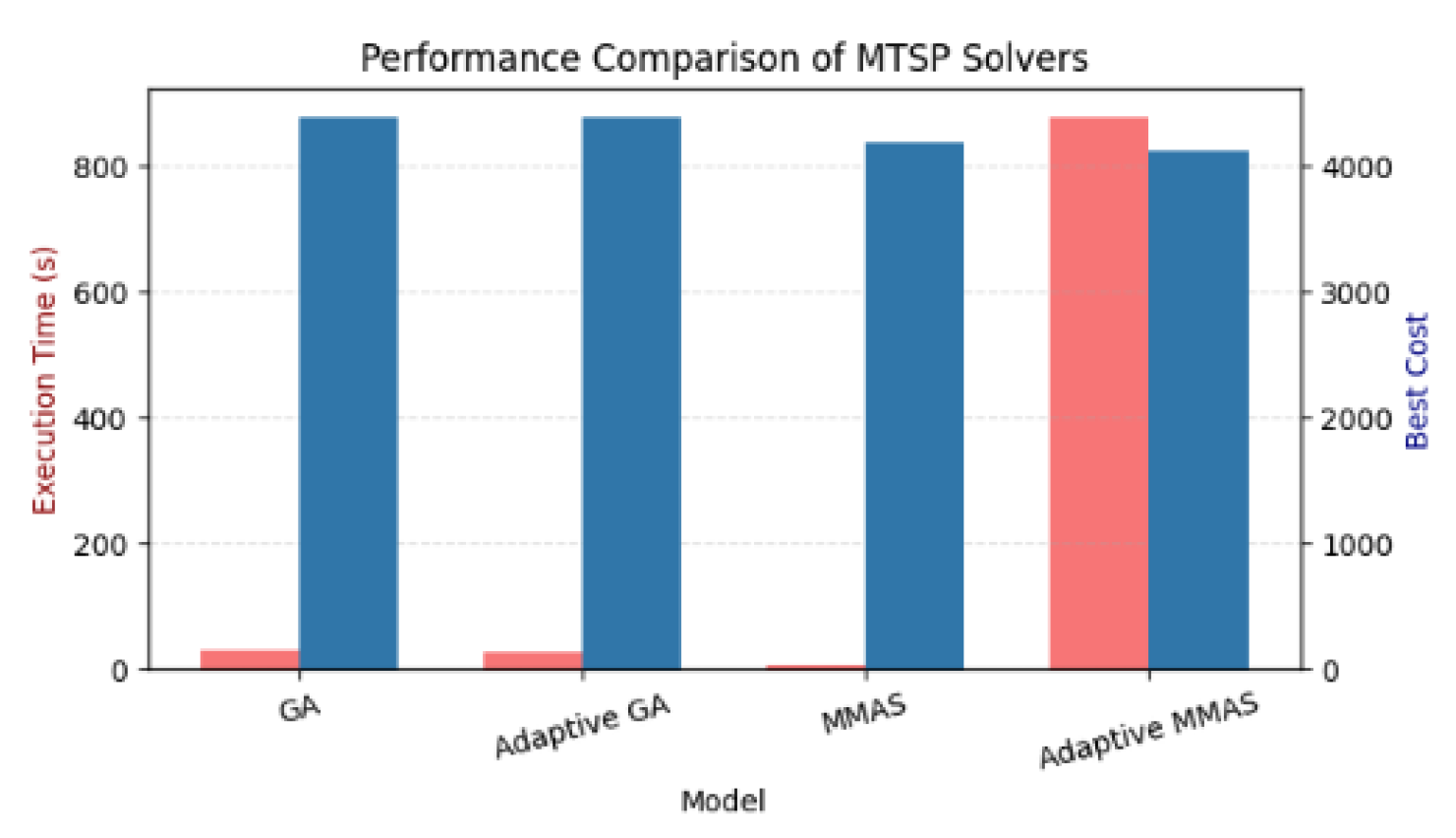

6.2. Performance Comparison of MTSP Solvers

Table tell the story. MCAH-ACO lands at 3672.94—12.3% below MMAS, 16.4% below GA. Runtime? Just 12.83 seconds, versus 879 seconds for Adaptive MMAS. That is a 68× speedup with a better answer. Decomposed pheromone matrices let the algorithm explore multiple objectives without explicit Pareto sorting. Probabilistic 2-opt refine tours cheaply.

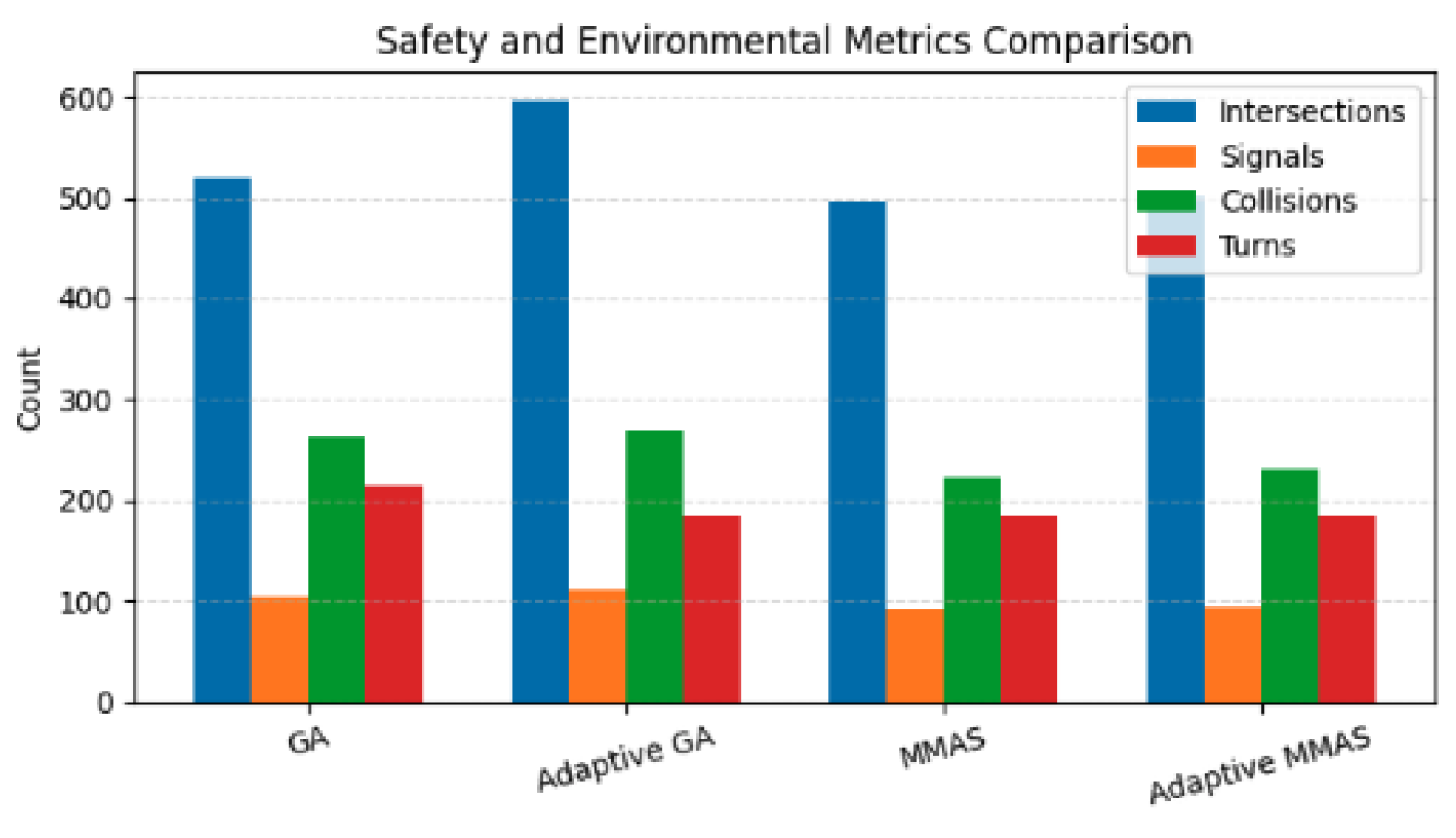

6.3. Safety and Environmental Performance

MCAH-ACO lead on every safety and environmental metric (

Table 3). Collisions: 181 versus 223 for MMAS, an 18.8% drop. Intersections: 412 versus 496, down 16.9%. Signals: 76 versus 92, down 17.4%. Turns: 156 versus 185, down 15.7%. Why the consistency? Adaptive weight balancing keep distance from hogging attention, so safety criteria get their due.

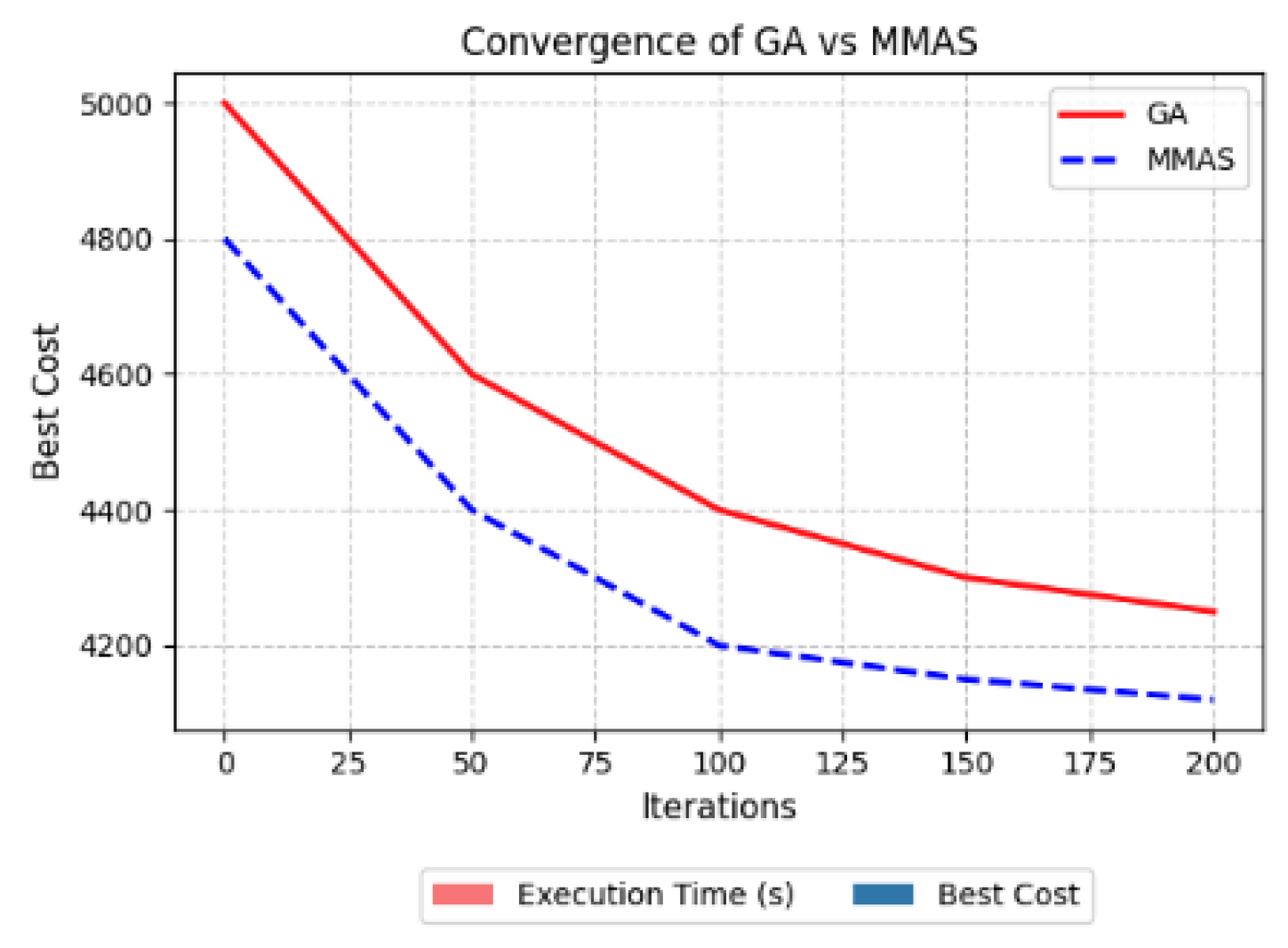

6.4. Convergence Analysis

Figure 2 track cost over iterations. Early on, 2-opt push MCAH-ACO ahead of the pack. Later, weight balancing sustain progress while baselines plateau. The diversity-aware archive resist premature stagnation, leaving room for late-stage gains.

6.5. Ablation Study

Which pieces matter?

Table 4 strip components one at a time.

Multi-criteria pheromone decomposition make the biggest difference—5.9% cost reduction when removed. Separate matrices clearly help. Adaptive weights rank second at 3.8%; without them, distance dominate. The 2-opt local search and archive diversity each shave off smaller but still meaningful margins. All four components pull their weight.

Figure 2.

Convergence curves for MCAH-ACO and baselines. The 2-opt component drives rapid early progress; weight balancing sustains improvement and yields a markedly lower final cost. Archive diversity guards against stagnation.

Figure 2.

Convergence curves for MCAH-ACO and baselines. The 2-opt component drives rapid early progress; weight balancing sustains improvement and yields a markedly lower final cost. Archive diversity guards against stagnation.

Figure 3.

MTSP solver comparison: runtime versus solution cost. MCAH-ACO hits the lowest cost at moderate runtime. Adaptive MMAS takes 68× longer yet returns a worse answer. Standard MMAS runs fastest but at higher cost.

Figure 3.

MTSP solver comparison: runtime versus solution cost. MCAH-ACO hits the lowest cost at moderate runtime. Adaptive MMAS takes 68× longer yet returns a worse answer. Standard MMAS runs fastest but at higher cost.

Figure 4.

Safety and environmental metrics by solver. MCAH-ACO tops every category: collisions down 18.8%, intersections down 16.9%, signals down 17.4% relative to MMAS. Multi-criteria pheromone decomposition drives these gains.

Figure 4.

Safety and environmental metrics by solver. MCAH-ACO tops every category: collisions down 18.8%, intersections down 16.9%, signals down 17.4% relative to MMAS. Multi-criteria pheromone decomposition drives these gains.

7. Conclusions

Delivery routing demand more than shortest-path calculation. Balancing distance, time, safety, and environmental impact call for a genuinely multi-criteria solver. MCAH-ACO answer this need through three interlocking mechanisms: decomposed pheromone matrices (one per objective), adaptive weight balancing driven by convergence feedback, and 2-opt local search paired with a diversity-preserving elite archive.

What do the experiments tell us? On Greater Toronto Area delivery data, MCAH-ACO reduce total cost by 12.3% relative to Max–Min Ant System while running in 12.83 seconds—far faster than Adaptive MMAS at 879 seconds. Collision-prone segments drop by 18.8%. Intersections fall 16.9%; traffic signals, 17.4%. The ablation study pinpoint multi-criteria pheromone decomposition as the largest contributor (5.9% cost reduction), though every component matters.

Several avenues remain open. Time-window constraints and real-time traffic data could push the algorithm toward live deployment. Scaling tests with hundred of nodes will clarify practical limits. Machine-learned parameter control may replace manual tuning. Heterogeneous fleets—vehicles with differing capacities—pose another natural extension. Explainable AI methods [

24] could make route recommendations more transparent to dispatchers. And ensuring equitable service across demographic groups [

25,

26,

27] is an ethical dimension worth pursuing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-F.L. and X.-Y.C.; methodology, D.-T.C.; validation, D.-T.C. and X.-Y.C.; investigation, D.-T.C. and K.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-F.L. and D.-T.C.; writing—review and editing, D.-T.C. and X.-Y.C.; visualization, D.-T.C.; project administration, H.-F.L.; funding acquisition, H.-F.L.; data curation, Z.-M.H.; formal analysis, H.-T.Z. and L.-Y.B.; resources, X.-Y.C.; software, X.-Y.C.; supervision, W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62372148.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used gpt5 for the purposes of proofread. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr.Zhimo Han, Dr.Kong Wang, Mr.Wei Knag and Mr.Haitao Zhang for their valuable work, which have greatly improved this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aston, O. V. Jason. Retail e-commerce and COVID-19; Statistics Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Baldacci, R.; Vigo, D.; Wang, X. A Multi-Depot Two-Echelon Vehicle Routing Problem. European Journal of Operational Research 2020, vol. 284(no. 3), 818–833. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas, S.; Marathe, R. Moving towards `mobile warehouse’: Last-mile logistics during COVID-19 and beyond. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 2021, vol. 10, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Khamis, A. Multi-criteria Optimal Routing for Last-mile Parcel Delivery with Autonomous Robots. IEEE Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Magazine 2022, vol. 8(no. 4), 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiadou, M. N.; Mavrovouniotis, M.; Hadjimitsis, D. Ant Colony Optimization for the Dynamic Electric Vehicle Routing Problem. In Proc. International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature; Springer, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, T.; Zou, J. Adaptive bidirectional planning framework for enhanced safety and robust decision-making in autonomous navigation systems. The Journal of Supercomputing 2025, vol. 81(no. 8), 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Chen, K.; Bi, Z.; Niu, Q.; Liu, J.; Peng, B.; Zhang, S.; Liu, M.; Li, M.; Pan, X. Mastering Reinforcement Learning: Foundations, Algorithms, and Real-World Applications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.00001. [Google Scholar]

- Cheikhrouhou, O.; Khoufi, I. A comprehensive survey on the Multiple Traveling Salesman Problem: Applications, approaches and taxonomy. Computer Science Review 2021, vol. 40, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stützle, T.; Hoos, H. H. MAX-MIN Ant System. Future Generation Computer Systems 2000, vol. 16(no. 8), 889–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, W. A. Solving Vehicle Routing Problem using Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm. International Journal of Recent Engineering Research 2018, vol. 3(no. 5), 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, R.; Singh, S. An optimization model for vehicle routing problem in last-mile delivery. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, vol. 225, 119978. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Mohamed, R.; Abouhawwash, M. Multi-objective Ant Colony Optimization: Review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2024, vol. 31, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. A Scheme Library-Based Ant Colony Optimization with 2-Opt Local Search for Dynamic Traveling Salesman Problem. Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2023, vol. 135(no. 2), 1417–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Deb, K. MOEA/D with adaptive weight vector adjustment and parameter selection based on Q-learning. Applied Intelligence 2024, vol. 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, T.; Chen, D.; Chen, K.; Li, Z. Offline Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving with Safety and Exploration Enhancement. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.07067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Ai, Y.; ElSamadisy, O.; Abdulhai, B. Bilateral Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach for Better-than-human Car Following Model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.04749. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhu, Z. DiffusionDepth: Diffusion Denoising Approach for Monocular Depth Estimation. In Proc. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, R.; Duan, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Chen, L. DriveMLLM: A Benchmark for Spatial Understanding with Multimodal Large Language Models in Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.13112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fang, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, S.; Jiao, J.; Shi, T. A Cascading Cooperative Multi-agent Framework for On-ramp Merging Control Integrating Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.08199. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, T.; ElSamadisy, O.; Abdulhai, B. "CoopSECRM2D-MM: Safe, Efficient, and Comfortable Multi-Agent RL for On-Ramp Merging," SSRN 5295761, 2025.

- Tang, W.; Zhang, H. W.; Huang, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, F.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y. AgentBuilder: Automating agent creation via large language model-driven systems. Neurocomputing 2025, vol. 646, 130476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Bi, Z.; Wang, T.; Wen, Y.; Niu, Q.; Liu, J.; Peng, B.; Zhang, S.; Pan, X.; Xu, J. Deep learning and machine learning with GPGPU and CUDA: Unlocking the power of parallel computing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.05686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Peng, B.; Song, X.; Zhang, C.; Sun, X.; Niu, Q.; Liu, J.; Chen, S. From aleatoric to epistemic: Exploring uncertainty quantification techniques in artificial intelligence. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.03282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, W.; Bi, Z.; Jiang, C.; Liu, J.; Peng, B.; Zhang, S.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, K. A comprehensive guide to explainable AI: From classical models to LLMs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.00800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Baldwin, T.; Cohn, T. Multi-EuP: The Multilingual European Parliament Dataset for Analysis of Bias in Information Retrieval. In Proc. 3rd Workshop on Multi-lingual Representation Learning (MRL); 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, F.; Baldwin, T. Language Bias in Multilingual Information Retrieval: The Nature of the Beast and Mitigation Methods. In Proc. Fourth Workshop on Multilingual Representation Learning (MRL); 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Han, X.; Baldwin, T. Demographics and Democracy: Benchmarking LLMs’ Gender Bias and Political Leaning in European Parliament. In Proc. 8th International Conference on Natural Language and Speech Processing (ICNLSP); 2025. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).