1. Introduction

Nauclea officinalis (commonly known as Danmu in China, DM), derived from the dried stems and roots of

Nauclea officinalis Pierre. ex Pitard, is characterized by its intense bitterness and cold nature [

1]. Modern pharmacological studies have identified abundant monoterpene indole alkaloids such as strictosamide and 3-epi-dihydrocorymine, as well as triterpenoids, exhibiting broad-spectrum antibacterial, anti-influenza virus, and immunomodulatory activities. Clinically, traditional DM preparations—including syrups, tablets, and capsules—are widely used for respiratory infections and skin inflammation [

2]; however, adverse gastrointestinal reactions, such as urticaria (0.23%), abdominal discomfort (0.38%), vomiting (1.08%), and diarrhea (1.29%), have been reported, with unclear mechanisms [

3].

The intestinal barrier, the largest immune system in the body, relies on physical, chemical, immune, and biological defenses to maintain homeostasis. Disruption of this barrier can increase permeability, trigger microbial dysbiosis, and induce chronic inflammation, exacerbating gastrointestinal diseases [

4]. Epithelial tight junctions (TJs), composed of occludin, claudins, and ZO-1, are critical for barrier integrity [

5,

6], and inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α can increase paracellular permeability via MLCK-mediated occludin phosphorylation [

7]. The gut microbiota also functions as a dynamic biological barrier, promoting TJ expression and inhibiting zonulin release; dysbiosis, characterized by decreased butyrate-producing bacteria and increased conditional pathogens like

Citrobacter and

Helicobacter, further compromises barrier function [

8,

9].

Bitter taste receptors (T2Rs), G protein-coupled receptors expressed in Paneth and enteroendocrine cells, act as sensors of luminal contents and mediate diet–microbiota–host crosstalk [

10,

11,

12]. Ligand binding activates Gα-gustducin, stimulating Paneth cells to secrete α-defensins and maintain a

Firmicutes and

Bacteroidetes-dominated microbiota [

13,

14,

15]. Disruption of T2R signaling, including downregulation of TAS2R108/TAS2R138 or impaired Gα-gustducin coupling, leads to reduced α-defensin secretion, dysbiosis, and compromised barrier integrity [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Chronic exposure to bitter alkaloids, such as berberine, can exacerbate gastrointestinal dysfunction by overactivating T2Rs [

19].

Given DM’s intense bitterness, it remains unclear whether its components act as agonists or antagonists of T2Rs, potentially disrupting Paneth cell function. We hypothesize that DM interferes with the T2R108/T2R138–Gα-gustducin axis, suppressing α-defensin secretion, altering gut microbiota composition, degrading tight junctions, increasing intestinal permeability, and triggering low-grade inflammation, ultimately causing gastrointestinal adverse effects. This study aims to test this hypothesis through in vivo and in vitro experiments, providing mechanistic insight and a basis for the safe clinical use of DM.

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Short-Term DM Intervention on Intestinal Function in Rats

2.1.1. Effects of Short-Term DM Intervention on Gastrointestinal Motility in Rats

To assess the effects of short-term DM intervention (14 days) on gastrointestinal motility, we measured the small intestinal propulsion rate (

Figure 1A) and gastric retention rate (

Figure 1B). Gastrointestinal motility disorders are typically characterized by reduced intestinal propulsion and delayed gastric emptying, often leading to symptoms such as reflux, diarrhea, and gastric retention [

25]. Compared with the normal diet (ND) group, the low-dose DM (L-DM) group exhibited a significantly decreased small intestinal propulsion rate (

p < 0.05), whereas the high-dose DM (H-DM) group showed a non-significant reduction (

p > 0.05). Similarly, gastric retention was significantly elevated in the L-DM group (

p < 0.05), while the H-DM group displayed a non-significant upward trend (

p > 0.05).

2.1.2. Effects of Short-Term DM Intervention on Inflammatory Levels in Rats

To assess intestinal inflammation following short-term DM intervention (14 days), serum levels of IL-6 (

Figure 1C) and TNF-α (

Figure 1D) were measured, as these are well-established biomarkers of drug-induced inflammatory responses [

26]. Compared with the ND group, the L-DM group showed no significant changes in IL-6 or TNF-α levels. In contrast, the H-DM group exhibited significantly elevated levels of both cytokines (

p < 0.05), indicating that high concentrations of DM may provoke inflammatory responses.

2.1.3. Effects of Short-Term DM Intervention on the Morphology of Ileum and Colon in Rats

As shown in

Figure 1E, H&E staining of the ileum revealed intact villus architecture in the ND group, with well-organized columnar epithelial cells, preserved cellular junctions, and abundant submucosal connective tissue with orderly vasculature. The L-DM group exhibited focal epithelial detachment and reduced crypt numbers, including partial crypt atrophy and fusion. In the H-DM group, scattered inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in the lamina propria, accompanied by distorted villus morphology, cellular degeneration, and necrosis.

H&E staining of the colon (

Figure 1F) showed that the ND group maintained orderly mucosal epithelium, regular crypt architecture, normal goblet cell morphology, and absence of inflammatory infiltration. The L-DM group retained basic mucosal integrity with occasional epithelial exfoliation and mild crypt disorganization without significant edema. In contrast, the H-DM group displayed dense inflammatory cell infiltration—including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages—throughout the lamina propria, with extensive formation of inflammatory foci.

2.2. Effects of Long-Term DM Intervention on the Intestine in Mice

2.2.1. Effects of Long-Term DM Intervention on Intestinal Inflammatory Levels in Mice

To assess intestinal inflammation following a 16-week DM intervention, serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, GSH-Px, SOD, and MDA were measured. Compared with the normal control group, DM-treated animals exhibited significantly elevated levels of all these markers (

p < 0.05;

Figure 2A–G). These results indicate that long-term DM administration triggers systemic inflammatory responses, as evidenced by increased IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ, and induces oxidative stress, reflected by elevated MDA levels accompanied by compensatory changes in SOD and GSH-Px.

2.2.2. Effects of Long-Term DM Intervention on Intestinal Wall Integrity in Mice

To assess intestinal barrier integrity following long-term DM intervention (16 weeks), we determined the relative expression levels of occludin and claudin using Western blot and RT-PCR analyses. The RT-PCR results revealed that compared with the ND group, all DM-treated groups exhibited significantly reduced expression of both occludin (

Figure 2H) and claudin-1 (

Figure 2I) (

p < 0.05). Consistent with these findings, Western blot analysis demonstrated that the protein expression levels of occludin (

Figure 2J and K) and claudin-1 (

Figure 2J and L) were also significantly decreased in all treatment groups compared to the ND group (

p < 0.05).

2.2.3. Effects of Long-Term DM Intervention on the Morphology of Ileum and Colon in Mice

H&E staining revealed dose-dependent intestinal injury (

Figure 2M and N). In the ileum, the ND group showed mild villus shortening with intact crypts; the L-DM group exhibited localized inflammation, partial villus fusion, and crypt disruption; the M-DM group displayed extensive villus loss, severely damaged crypts, mucosal edema, and obscured vasculature; the H-DM group showed diffuse inflammatory infiltration, complete villus destruction, and unrecognizable crypts.

In the colon, the ND group maintained well-organized mucosa with intact crypts and no inflammation; the L-DM group had focal epithelial exfoliation and mild crypt disorganization; the M-DM group exhibited multiple erosions, irregular epithelial morphology, and lamina propria inflammation; the H-DM group showed extensive epithelial necrosis, crypt abscesses, and widespread inflammatory infiltration. These results indicate that DM induces dose-dependent intestinal injury, progressing from mild architectural changes to severe epithelial destruction.

2.3. Effects of Long-Term DM Intervention on Intestinal Flora

2.3.1. Effects of DM on Alpha and Beta Diversity

To investigate the effects of DM on the gut microbiota, we analyzed both α- and β-diversity. The M-DM group was selected for 16S rRNA sequencing. As shown in

Figure 3, compared with the ND group, the DM-treated (DM) group exhibited significantly decreased Chao1 (

Figure 3A), ACE (

Figure 3B), and observed ASVs (

Figure 3C) indices

(p < 0.05). Although the Simpson (

Figure 3D) and Shannon (

Figure 3E) indices also showed a decreasing trend, the differences were not statistically significant

(p > 0.05). In the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot (

Figure 3F), clear separation was observed between the ND and DM groups, indicating that DM treatment reduced microbial species richness and diversity, and altered the overall structure of the gut microbiota in mice.

3.2. Effects of DM on the Composition of Intestinal Microorganisms

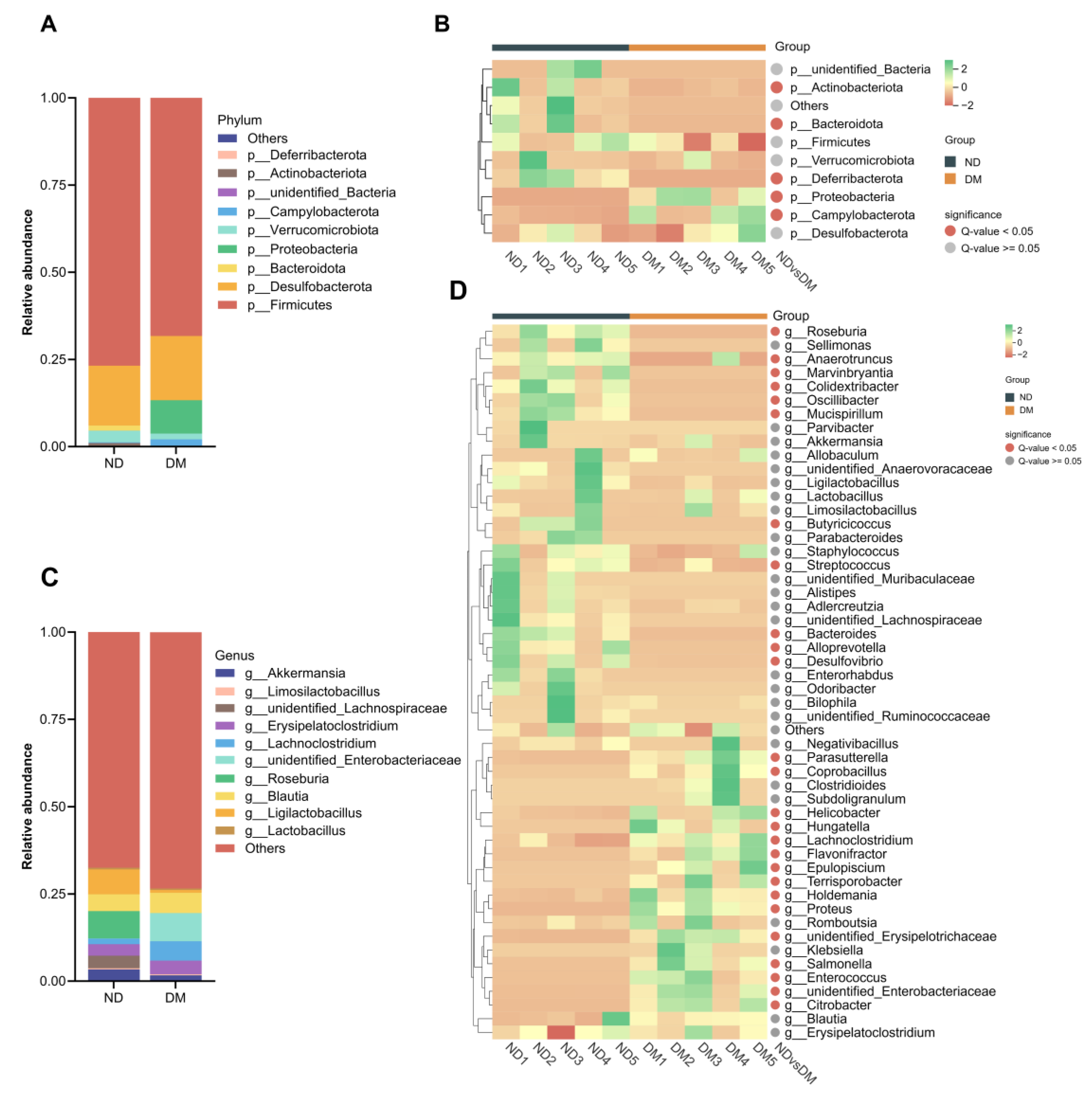

Following DM administration, significant alterations in the gut microbial composition at the phylum level were observed (

Figure 4A, B). Compared with the ND group, the DM group exhibited significantly increased abundances of Proteobacteria and Campylobacterota (

p < 0.05), while the abundances of Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, and Deferribacterota were significantly decreased

(p < 0.05).

At the genus level (

Figure 4C,D), the DM group showed significantly reduced abundances of

Bacteroides,

Alloprevotella,

Anaerotruncus,

Butyricicoccus,

Colidexeribacter,

Desulfovibrio,

Marvinbryantia,

Mucispirillum,

Oscillibacter,

Roseburia, and

Streptococcus (p < 0.05). Conversely, significantly increased abundances were observed for

Citrobacter,

Coprobacillus,

Enterococcus,

Epulopiscium,

Flavonifractor,

Helicobacter,

Holdemania,

Hungatella,

Lachnoclostridium,

Parasutterella,

Proteus,

Salmonella,

Terrisporobacter,

unidentified Enterobacteriaceae, and

unidentified Erysipelotrichaceae (

p < 0.05).

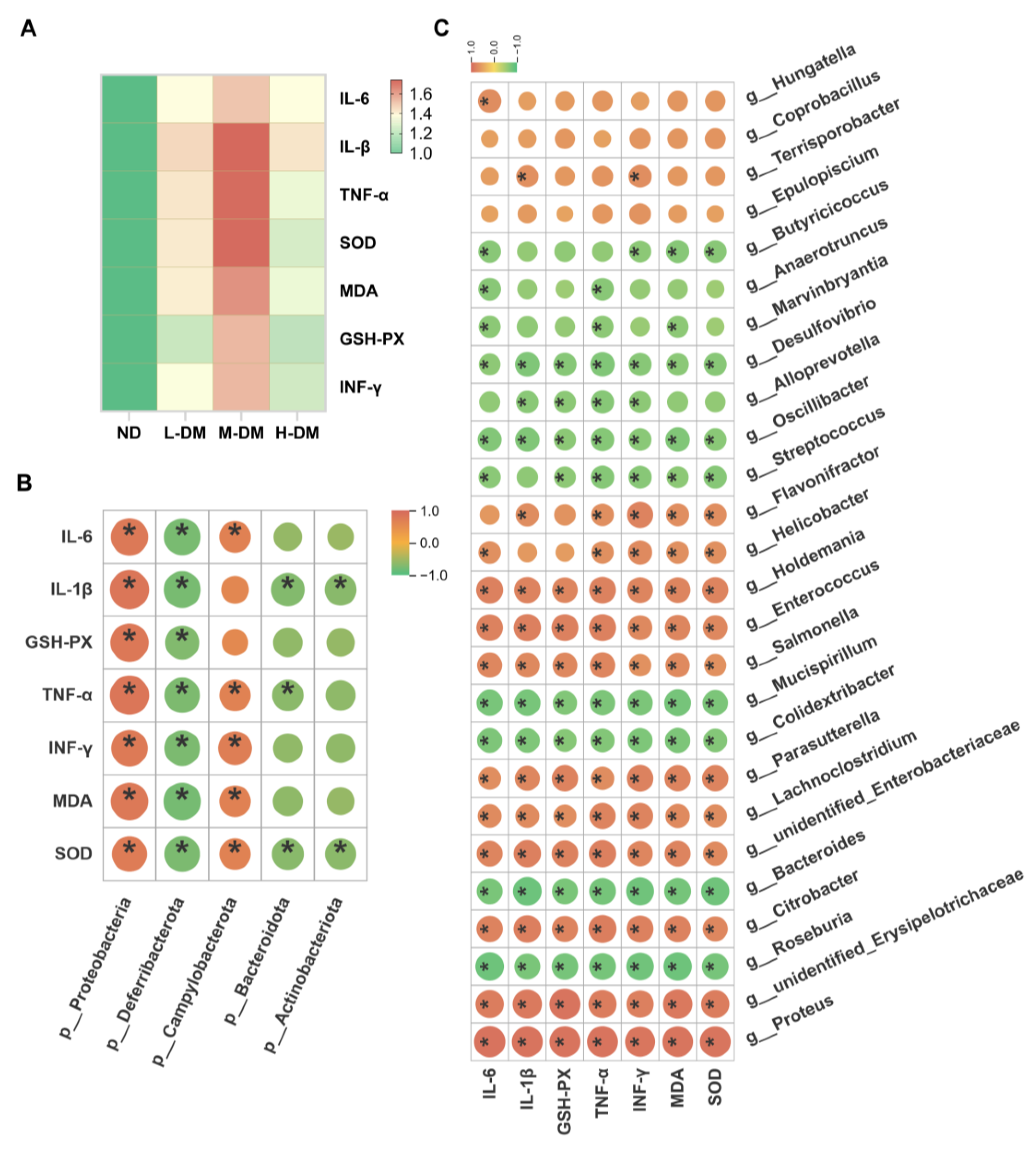

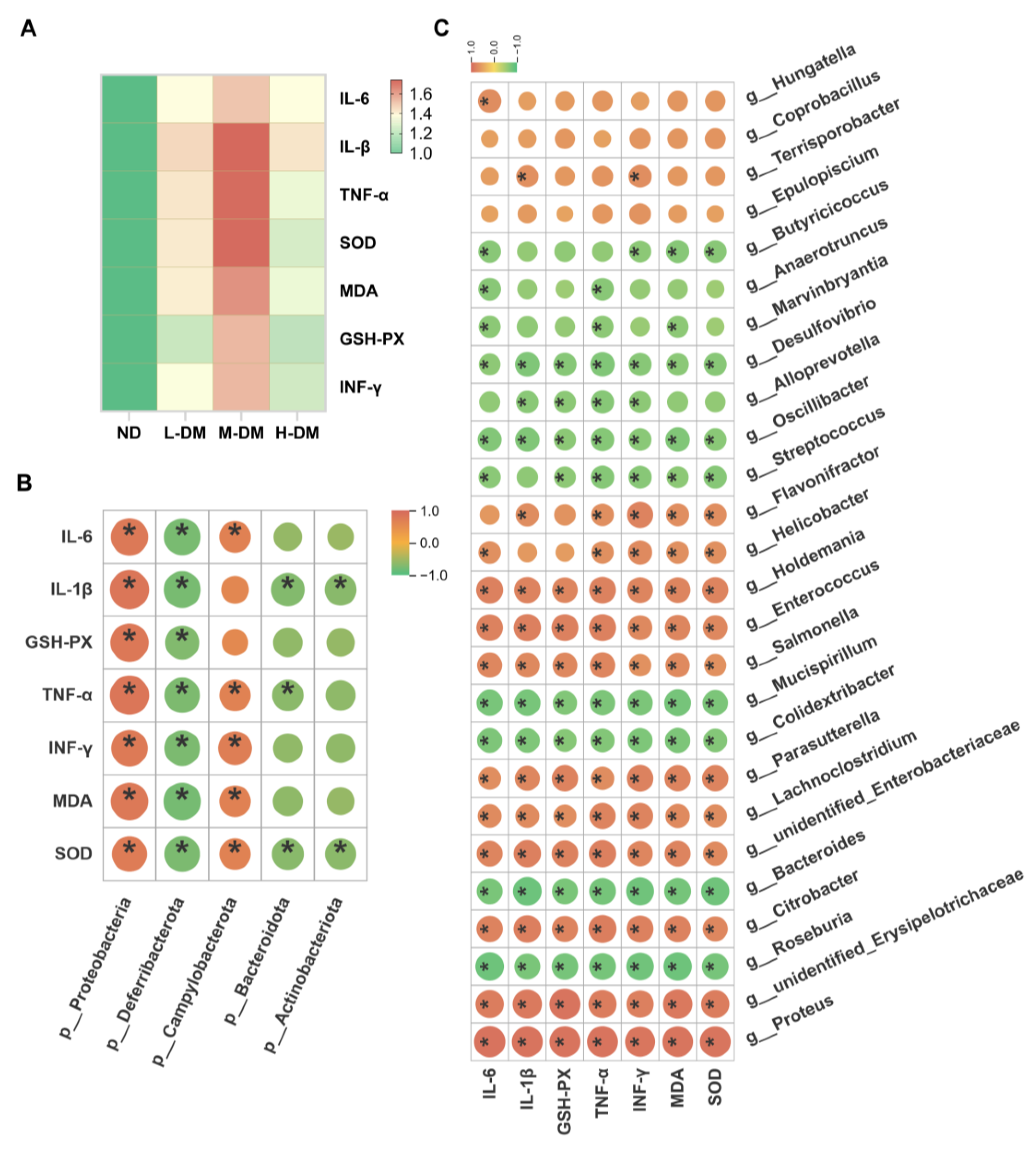

3.3. Correlation Analysis Between Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory/Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

To investigate the correlation between gut microbiota alterations and inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarkers, we performed correlation analyses of microbial changes at both phylum and genus levels with these host factors in a mouse model. As illustrated in

Figure 5, all DM-treated groups exhibited significantly elevated levels of inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarkers compared to the normal control group (

Figure 5A). Analysis at the phylum level (

Figure 5B) revealed positive correlations between these biomarkers and the abundances of

Proteobacteria and

Campylobacterota, while negative correlations were observed with

Bacteroidota,

Actinobacteriota, and

Deferribacterota. At the genus level (

Figure 5C), the biomarkers showed significant negative correlations with several commensal and beneficial genera, including

Bacteroides,

Alloprevotella,

Butyricicoccus,

Roseburia, and

Oscillibacter, but positive correlations with multiple opportunistic or pathogenic taxa such as

Helicobacter,

Salmonella,

Citrobacter,

Enterococcus, and

Lachnoclostridium. These results indicate that the pro-inflammatory effects induced by DM are closely associated with gut microbial dysbiosis.

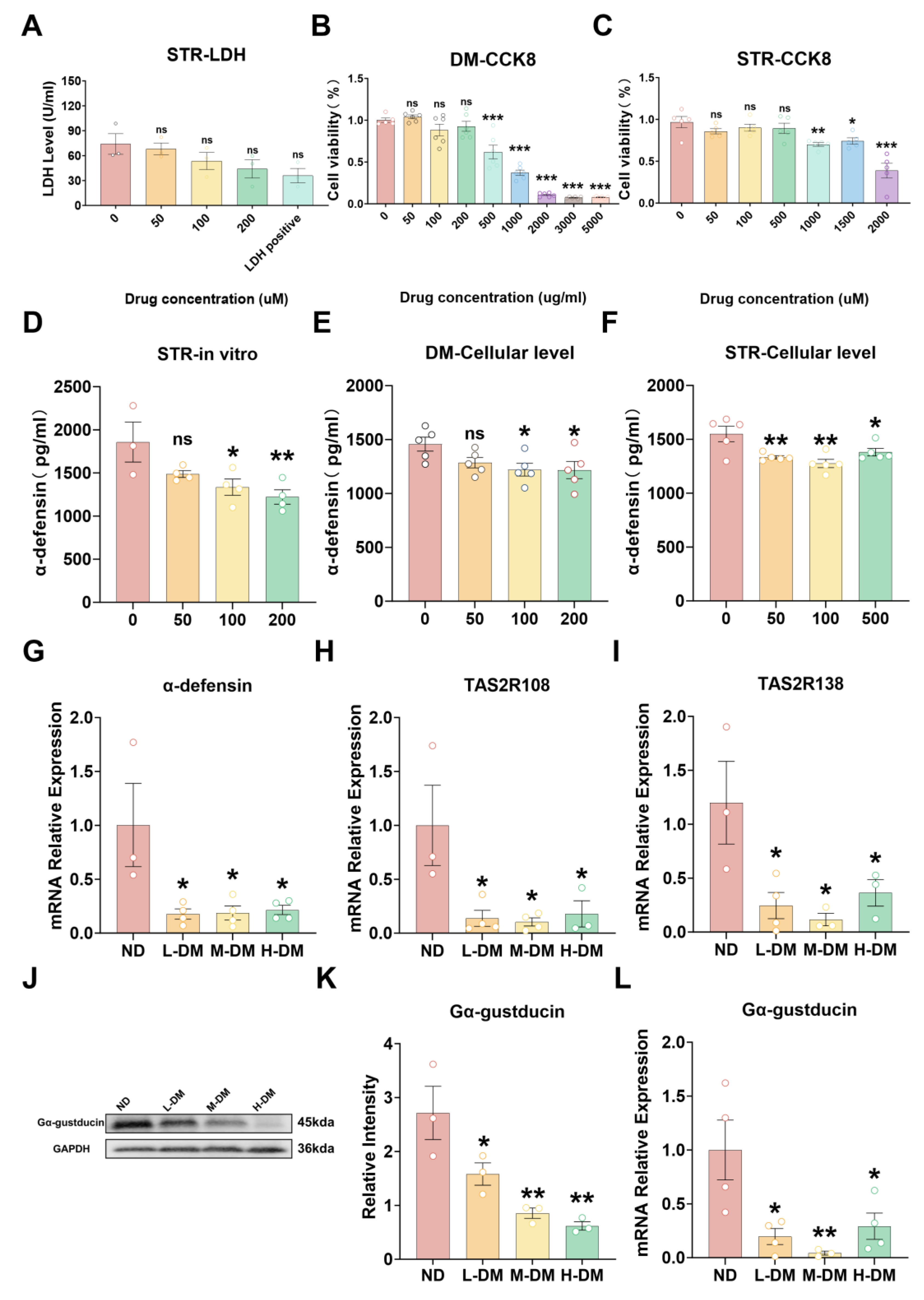

2.4. Effects of DM on Cell/Tissue Viability and T2R/α-Defensin Expression

2.4.1. Effects of DM on Viability in STC-1 Cells and Ileal Ex Vivo Tissue

To assess the effects of DM on STC-1 cell viability and intestinal tissue integrity, we employed the CCK-8 assay for STC-1 proliferation and metabolic activity, and the LDH release assay for ex vivo ileal tissue viability. While strictosamide induced a concentration-dependent decrease in LDH release, the effect was not statistically significant (

Figure 6A,

p > 0.05). In contrast, DM extract caused a dose-dependent reduction in STC-1 viability over 48 hours. Specifically, exposure to 1000 μg/mL DM extract or 1500 μM strictosamide reduced cell viability below 80% (

Figure 6B,C,

p < 0.05), commonly accompanied by compromised membrane integrity, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and activation of apoptotic/necrotic pathways. subsequent in vitro experiments were conducted using sub-cytotoxic concentrations of DM extract (0–200 μg/mL) and strictosamide (0–500 μM) to avoid confounding effects from overt cytotoxicity.

2.4.2. Effects of DM on the Expression of Antimicrobial Peptides

To assess the impact of DM on antimicrobial peptide secretion, α-defensin expression and release were evaluated in vivo, in vitro, and ex vivo. Ex vivo, ELISA demonstrated that strictosamide at 100 and 200 μM markedly suppressed α-defensin secretion relative to controls (

Figure 6D). In STC-1 cells, both DM extract and strictosamide inhibited α-defensin release: 100 and 200 μg/mL DM extract significantly reduced secretion (

Figure 6E), and all tested concentrations of strictosamide produced significant decreases compared with controls (

Figure 7F).In RT-qPCR showed that DM treatment significantly reduced α-defensin mRNA expression compared with the ND group (

Figure 6G).

2.4.3. Effects of DM on the Expression of Bitter Taste Receptors

To investigate the effects of DM on bitter taste receptor expression, we analyzed the relative expression levels of intestinal TAS2R108 (

Figure 6H), TAS2R138 (

Figure 6I), and Gα-gustducin (

Figure 6L) by RT-qPCR, and detected the protein expression of Gα-gustducin by Western blot (

Figure 6J, K). The RT-qPCR results demonstrated that compared with the normal control group, DM-treated groups showed significantly lower relative expression levels of TAS2R108, TAS2R138, and Gα-gustducin (

p < 0.05). Consistent with these findings, Western blot analysis revealed that the protein expression of Gα-gustducin was also significantly downregulated in all treatment groups compared to the normal control group (

p < 0.05;

Figure 6J, K). Our results demonstrate that DM treatment significantly suppressed the expression of intestinal TAS2R108, TAS2R138, and Gα-gustducin in mice (

Figure 6).

3. Discussion

This study provides a systematic and mechanistic framework for understanding the gastrointestinal toxicity associated with Nauclea officinalis (DM), addressing a long-standing gap in the toxicological evaluation of traditional medicinal plants. Although DM has demonstrated therapeutic potential, accumulating clinical observations have reported gastrointestinal adverse reactions [

3,

27], yet the initiating molecular events and downstream pathogenic pathways remain largely undefined. Our findings reveal that DM induces gastrointestinal injury through distinct mechanisms under short-term and long-term exposure, ultimately converging on impairment of intestinal motility, disruption of mucosal barrier integrity, innate immune suppression, and dysregulation of bitter taste receptor–mediated signaling.

Short-term toxicity evaluations demonstrated a concentration-dependent effect of DM. In vitro assays indicated that the threshold concentration for reducing cell viability below 80% was approximately 1000 μg/mL for DM extract and 1500 μM for strictosamide; however, the ex vivo ileum model showed limited sensitivity, likely due to complex tissue-level compensatory factors. In vivo, low-dose DM impaired gastrointestinal motility, consistent with characteristics of motility disorders implicated in IBS [

28], IBD [

29], and peptic ulcer disease [

30]. In contrast, high-dose exposure elicited robust systemic inflammation, evidenced by elevated IL-6 and TNF-α levels and early mucosal damage in both the ileum and colon—findings aligned with previous reports that high-dose plant extracts can induce inflammatory cascades leading to intestinal injury [

31,

32].

To explore whether these acute perturbations progress toward chronic gastrointestinal dysfunction, we extended our investigation to long-term exposure models. Chronic DM administration resulted in a marked deterioration of intestinal barrier integrity, characterized by significant downregulation of the tight junction proteins Occludin and Claudin-1 [

33,

34,

35,

36]. This structural and functional impairment of the tight junction complex mechanistically explains the dysregulated osmotic balance observed in our model [

37,

38].

A major discovery of this study is the profound effect of long-term DM intervention on the gut microbial ecosystem. DM induced an expansion of

Proteobacteria and other opportunistic pathogens [

39,

41,

42], accompanied by depletion of beneficial taxa such as

Bacteroidetes [

40],

Actinobacteria [

43,

44], and butyrate-producing genera including

Roseburia and

Faecalibacterium. Given that butyrate regulates epithelial energy metabolism, junctional protein expression, and mucus secretion [

45,

46], its decline likely contributes to DM-induced barrier dysfunction.

Consistent with these observations, long-term DM exposure induced systemic inflammation (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ) and oxidative stress (altered SOD, GSH-Px, and elevated MDA) [

47]. This supports a progressive pathological model in which gut dysbiosis and barrier disruption trigger systemic inflammatory and oxidative responses that further damage the intestinal epithelium—processes known to involve lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation [

48], as well as NF-κB–mediated MLCK activation leading to tight junction destabilization [

49]. Correlation analyses reinforced this model, revealing positive associations between pathogenic taxa and inflammatory/oxidative markers, and negative associations with beneficial microbes. These findings align with the “dysbiosis→barrier impairment→systemic inflammation/oxidative stress→ worsened barrier dysfunction” hypothesis [

50].

Beyond microbiota-mediated pathways, this study highlights the crucial role of innate immunity, particularly α-defensins, in DM-induced gastrointestinal toxicity. Through in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro models, we confirmed that DM suppresses α-defensin expression and secretion [

15,

51]. Since α-defensins inhibit opportunistic pathogens and maintain microbial homeostasis, their reduction provides a mechanistic explanation for the observed dysbiosis and tight junction impairment.

Importantly, we identified suppression of the bitter taste receptor signaling axis (TAS2R108/TAS2R138–Gα-gustducin) as a central mechanistic driver of long-term DM toxicity. Dysfunction of T2R signaling has been linked to reduced defensin secretion [

52], microbial dysbiosis, and worsened colitis in DSS-induced models [

53]. TAS2R138 deficiency has also been associated with impaired immune function and defensin regulation [

54]. Notably, unlike other bitter phytochemicals such as constituents of Coptis chinensis that act via T2R activation, DM uniquely inhibits T2R signaling [

19], highlighting a mechanistic divergence in bitter herb–induced enterotoxicity.

While DM has reported anti-infective activity [

55], our findings emphasize its dual nature—therapeutic at appropriate doses but potentially harmful with long-term or excessive use. This underscores the importance of dose, duration, and safety evaluation in clinical applications of herbal medicines. Identification of the T2R pathway as a key regulatory node suggests potential therapeutic avenues; T2R agonists may restore defensin production and intestinal homeostasis and may serve as promising candidates for inflammatory bowel disease therapy.

Several limitations warrant consideration. Although strictosamide was identified as a primary active component, synergistic or antagonistic effects of other constituents cannot be excluded. Moreover, the causal role of α-defensins in DM-induced dysbiosis requires further validation using gene knockout models. Future studies employing targeted metabolomics, single-cell transcriptomics, and T2R-deficient animals may refine the mechanistic framework proposed here.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study systematically delineates the mechanistic basis of the gastrointestinal toxicity induced by both short-term and long-term exposure to Nauclea officinalis. Short-term administration predominantly resulted in gastrointestinal motility disturbances at low doses, while high-dose exposure provoked acute enteritis through the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α. In contrast, long-term toxicity was driven by the inhibition of intestinal bitter taste receptors (TAS2R108/TAS2R138) and the downstream Gα-gustducin signaling pathway, leading to marked suppression of enteric α-defensin secretion, gut microbiota dysbiosis, impairment of the mucosal barrier, and subsequent systemic inflammation. These findings, for the first time, identify the bitter taste receptor signaling axis as a central mediator of the chronic intestinal toxicity of this traditional medicinal herb, offering a new conceptual framework for understanding the potential enterotoxicity of bitter-cold herbal medicines and providing an important theoretical basis for the safe clinical use of Nauclea officinalis.

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanism of Nauclea officinalis-induced gastrointestinal toxicity.

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanism of Nauclea officinalis-induced gastrointestinal toxicity.

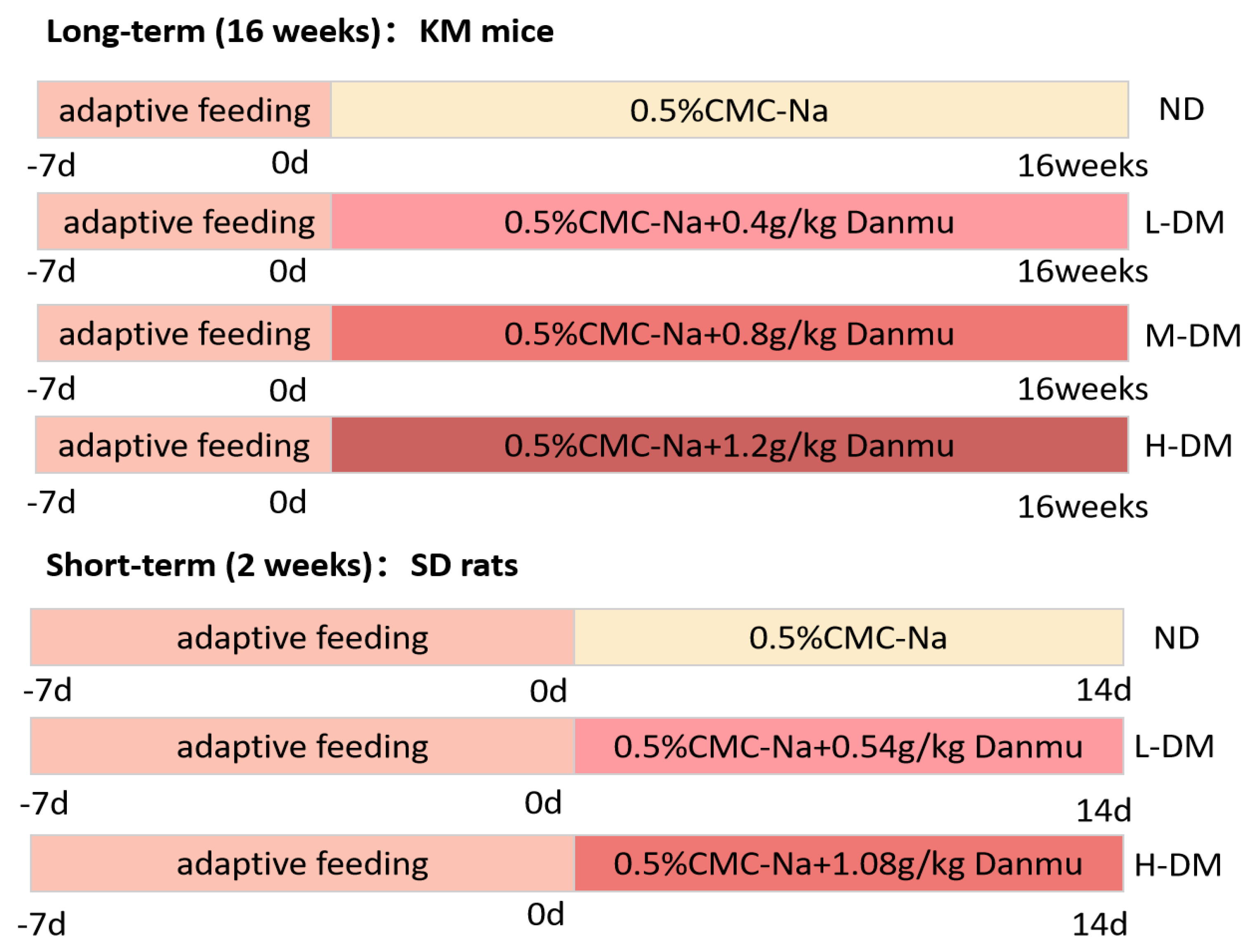

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Materials

A total of five kilograms of dried DM stems were pulverized into coarse powder. The powder was extracted three times with distilled water under reflux conditions, each extraction lasting 3 hours. The combined aqueous extracts were filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator (RE-2010). The concentrated extract was subsequently freeze-dried at 60 ℃ using a freeze dryer (FD-1A-50, Beijing BoMedicom Experimental Instrument Co.; Ltd.) to obtain the DM water extract. For animal experiments, the DM extract powder was suspended in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose sodium (CMC-Na) solution and administered orally

5.2. Animals and Ethics Statement

Six to eight-week-old male KM mice were purchased from Sibefu (Beijing) Biotechnology Co.; Ltd.; and five- to six-week-old male SD rats were obtained from Changsha Tianqin Biotechnology Co.; Ltd. All animals were acclimated for one week prior to experiments with free access to water and food. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hainan Medical University and complied with the Guideline on the Humane Treatment of Laboratory Animals issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China.

5.3. Grouping and DM Treatment

Forty KM mice were randomly selected, with 8 used for in vitro intestinal experiments; the remaining 32 were randomly divided into 4 groups (n=8 per group): normal group (ND group), low-dose DM group (L-DM) (0.4 g/kg), medium-dose DM group (M-DM) (0.8 g/kg), and high-dose DM group (H-DM) (1.2 g/kg). Thirty SD rats were randomly divided into 3 groups (n=8 per group): normal group (ND group), low-dose DM group (L-DM) (0.54 g/kg), and high-dose DM group (H-DM) (1.08 g/kg). The administration method was intragastric gavage, once a day. KM mice were gavaged continuously for 16 weeks, and SD rats were gavaged continuously for 2 weeks. Details are as follows (

Figure 8):

5.4. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MDA, SOD, IFN-γ, GSH-Px,and α-defensin were determined using commercial assay kits (Fankewei, China) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

5.5. Intestinal Flora Diversity

After euthanasia, cecal contents were collected into cryovials and subjected to 16S rRNA sequencing for gut microbiota analysis. This sequencing service was commissioned to Wuhan Metware Technology Co.; Ltd. In short, cecal fecal samples were collected and immediately stored at −80 ℃. Genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method. The V3–V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with primers 341F (5’-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3′). PCR products were pooled, purified, and used for library construction with the TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Kit. After quantification by Qubit 2.0 and qPCR, libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Metware Technology Co.; Ltd.; Wuhan, China). Raw reads were demultiplexed and trimmed to remove barcode and primer sequences, and paired-end reads were merged using FLASH (v1.2.7). Quality filtering and chimera removal were performed in QIIME (v1.9.1) to obtain high-quality effective tags. OTU clustering was conducted using Uparse (v7.0.1001) at 97% similarity. Taxonomic assignment was performed with the Silva SSU rRNA database using the Mothur classifier. Alpha and beta diversity analyses were completed in QIIME, and community composition at different taxonomic levels was analyzed and visualized in R (v2.15.3).

5.6. Gastrointestinal Motility Assessment: Small Intestinal Propulsion and Gastric Retention Rate

On the final day of modeling and drug administration, rats were fasted for 12 hours with free access to water. Subsequently, each rat received a 10 mL·kg⁻¹ dose of semi-solid paste via oral gavage. The semi-solid paste was prepared as follows: 10 g of carboxymethyl cellulose sodium was dissolved in 250 mL distilled water, followed by the addition of 16 g milk powder, 8 g sugar, 8 g starch, and 3 g activated carbon. The mixture was stirred uniformly to form 300 mL (approximately 300 g) of semi-solid paste, stored at 4°C, and allowed to reach room temperature 2 hours before use. Thirty minutes after gavage, rats were anesthetized for sample collection. Blood was drawn from the abdominal aorta, and the abdominal cavity was opened. The pylorus and cardia were ligated with surgical sutures, and the stomach was excised. After removing residual blood with filter paper, the total stomach weight was recorded. The stomach was then opened along the greater curvature, and the contents were rinsed with physiological saline. The empty stomach was blotted dry with filter paper and weighed again to obtain the net weight. Gastric retention rate was calculated as: (Total stomach weight - Net stomach weight) / Mass of administered semi-solid paste × 100%*; Gastric emptying rate was derived as: [1 - (Total stomach weight - Net stomach weight) / Mass of administered semi-solid paste] × 100%; Following stomach collection, the intestine was isolated. The segment from the pylorus to the ileocecal junction was carefully separated and measured to determine the total small intestinal length. The distance from the pylorus to the farthest point of charcoal advancement was measured to assess propulsion. Small intestinal propulsion rate was calculated as: (Distance from pylorus to charcoal forefront / Total small intestinal length) × 100% [

56].

5.7. RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse ileum tissues using the Eastep® Super Total RNA Extraction Kit, and its concentration was measured with a BIO-RAD spectrophotometer. The RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the Hifair® III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR (gDNA digester plus). The resulting cDNA products were used as templates for quantitative PCR (qPCR), which was performed on a BIO-RAD qPCR detection system with Hifair® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Low Rox Plus). Relative gene expression was analyzed using the 2^(-ΔΔCT) method, with β-actin serving as the internal reference gene. Primer sequences are listed in the table below.

Table 1.

List of primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR.

Table 1.

List of primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR.

| Primer Name |

Primer Name |

| Actb-1R |

GACCCATTCCCACCATC |

| Actb-1F |

TCTTTGCAGCTCCTTCGT |

| Defa-5-R |

GCAGCCTCTTATTCTACAATAGCA |

| Defa-5-F |

CTAATACTGAGGAGCAGCCAGG |

| Ocln-1F |

CTGCCTGCACGATGTCT |

| Ocln-1R |

GAGTGTTCAGCCCAGTCAA |

| Cldn11-2F |

CAGGTGGTGGGTTTCGT |

| Cldn11-2R |

CAGGTGGGGATGGTGTAG |

| Tas2r108-2F |

AACAGGACCAGCTTTTGGAATC |

| Tas2r108-2R |

GAGGAAACAGATCATCAGCCTCAT |

| Tas2r138-1F |

CACAACTACCAAGCCATCC |

| Tas2r138-1R |

TGTGAGAGAAGCGGACAA |

| Gnat3-1F |

CCCAGCCACTAACATCAAA |

| Gnat3-1R |

TTCACAGTTCTTGCATCCCT |

5.8. Western Blot Assay

Total protein was extracted from ileal tissues using RIPA lysis buffer (strong) supplemented with 1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). The protein concentration was measured using a protein assay kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. The samples were then diluted to equal concentrations and denatured with 5× SDS loading buffer at 90°C for 10 min. The proteins were separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Subsequently, the membranes were blocked by incubation in Rapid Blocking Buffer at room temperature for 1 hour, followed by incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with Tris-buffered saline containing Tween-20 (TBST), the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 hours. All information regarding the primary and secondary antibodies is listed in Table 3. The protein bands were visualized using an ECL Plus kit and the signals were captured using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS+ molecular imager system. The intensity of each band was analyzed using Image Lab software (version 5.2.1, Bio-Rad). GAPDH protein was used as a reference for normalizing the results of the target proteins. The final results for each target protein are expressed as its abundance relative to that of GAPDH.

Table 2.

Details of antibodies used in western blot and immunohistochemistry analyses.

Table 2.

Details of antibodies used in western blot and immunohistochemistry analyses.

| Antibody |

Product code |

Manufacturer |

Dilution ratio |

| GAPDH |

AG8015 |

Beyotime |

1:2000 |

| Occludin |

AF7644 |

Beyotime |

1:500 |

| Claudin-1 |

AF6504 |

Beyotime |

1:500 |

| Gα-gustducin |

sc-518163 |

SANTA |

1:100 |

5.9. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

The terminal ileum and proximal colon were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 hours. After paraffin embedding performed by Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.; Ltd.; the samples were sectioned into 3 μm thick slices using a microtome. Intestinal damage was evaluated following hematoxylin and eosin staining.

5.10. Cells and Treatment

The enteroendocrine STC-1 cell line was purchased from iCell Bioscience (Shanghai) Inc. Cells were maintained in culture medium supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin‒streptomycin solution, and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂.

5.11. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

After counting, STC-1 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 7.5 × 10⁴ cells per well. Each well received 100 μL of culture medium, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere for 24 hours. The original culture medium was then discarded, and treatments were administered to the respective groups: Nauclea officinalis extract (5 mg/mL) and streptomycin (STR, 1 mg/mL). Following 48 hours of stimulation, the medium was removed and the CCK-8 working solution was diluted 10-fold. A volume of 100 μL of the diluted CCK-8 solution was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 2 hours at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ incubator. Finally, the absorbance of each well was measured at a single wavelength of 450 nm.

5.12. Primary Intestinal Cell Culture

After one week of acclimatization feeding, Kunming mice were euthanized. The ileum (5 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve) was collected and intestinal segments were stored in ice-cold KRB/HEPES buffer bubbled with O₂/CO₂ (95%/5%). For primary cell culture, the intestinal segments were longitudinally opened and cleared of debris using buffered KRB/HEPES. Each segment was then trimmed into 1 cm pieces. The circular tissue specimens were transferred to 12-well plates containing 1 mL of ice-cold KRB/HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) and maintained at room temperature for 30 minutes, followed by incubation in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% (v/v) CO₂. After 1 hour of pre-incubation, the buffer was replaced with pre-warmed drug-containing KRB/HEPES buffer, and incubation was continued for an additional hour [

57,

58].

5.13. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release Assay

LDH release was measured using an LDH assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after drug treatment, the isolated intestinal tissues were homogenized and centrifuged at 8,500 rpm and 4°C for 10 minutes. The tissue was then collected for analysis. The subsequent detection procedures were performed following the manufacturer's protocol (Puyinte, China) [

59].

5.14. Statistic Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.5). Data were presented as mean ± Standard Error of the Mean. All quantitative data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for intergroup comparisons when homogeneity of variance was satisfied. When the assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated, the rank transformation test was employed. A p-value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization,L.X.; Y.Y and F.M.; methodology,L.X.; software, S.T.; validation, H.Z.; L.X. and W.L.; formal analysis, L.X. and Y.Y; investigation, L.X. and Y.Y; resources,B.X.; data curation, L.X.; writing—original draft preparation,L.X; writing—review and editing, J.X. and F.M; visualization, J.J.; supervision, B.S.; project administration, F.M.; funding acquisition, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation High-Level Talent Project (825RC770) and Hainan Medical University Undergraduate Training Program for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (X202511810149).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Hainan Medical University (protocol code HYLL-2024-530).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to privacy protection and ethical requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the editors and peer reviewers for their critical reading and insightful comments, which are helpful to improve our manuscript substantially.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DM |

Nauclea officinalis |

| T2R |

bitter taste receptor |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin-1 beta |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon-gamma |

| SOD |

Superoxide Dismutase |

| MDA |

Malondialdehyde |

| GSH-PX |

Glutathione Peroxidase |

References

- Wu, MH; Li, NX; Zhang, Y.; et al. Textual research on the origin of Nauclea officinalis used as medicine. Journal of Chinese Medicinal Materials 2019, 42, 2709–2714. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, J.H.; Sun, L.X. Research progress on Nauclea officinalis and its preparations. Asia-Pacific Traditional Medicine 2018, 14, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L; Miao, HQ; Su, X.J.; et al. Construction of a signal mining model for serious adverse drug reactions based on real-world data: an empirical study using Nauclea officinalis preparations as an example. China Food & Drug Administration Magazine 2024, 10, 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- Okumura, R.; Takeda, K. The role of the mucosal barrier system in maintaining gut symbiosis to prevent intestinal inflammation. Seminars in Immunopathology 2024, 47, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F.; Artis, D.; Becker, C. The intestinal barrier: a pivotal role in health, inflammation, and cancer. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2025, 10, 573–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieryńska, M.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Struzik, J.; et al. Integrity of the Intestinal Barrier: The Involvement of Epithelial Cells and Microbiota—A Mutual Relationship. Animals 2022, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Graham, W.V.; Wang, Y.; et al. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergize to induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by up-regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am J Pathol 2005, 166, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P; Ishimoto, T; Fu, L.; et al. The Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 733992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Probiotics in reducing obesity by reconfiguring the gut microbiota. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2024, 49, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sternini, C.; Rozengurt, E. Bitter taste receptors as sensors of gut luminal contents. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2024, 22, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, NH; Hung, K; Haribhai, D.; et al. Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nature Immunology 2009, 11, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howitt, MR; Lavoie, S; Michaud, M.; et al. Tuft cells, taste-chemosensory cells, orchestrate parasite type 2 immunity in the gut. Science 2016, 351, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevins, C.L.; Salzman, N.H. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011, 9, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnava, S; Behrendt, CL; Ismail, A.S.; et al. Paneth cells directly sense gut commensals and maintain homeostasis at the intestinal host-microbial interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 20858–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, NH; Hung, K; Haribhai, D.; et al. Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nat Immunol 2010, 11, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y; Li, W; Sun, K.; et al. Berberine ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium -induced colitis through tuft cells and bitter taste signalling. BMC Biology 2024, 22, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P; Chai, J; Yi, H.; et al. Aggravated gut inflammation in mice lacking the taste signaling protein α-gustducin. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2018, 71, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, RH; Lee, GE; Lee, K.; et al. Anti-inflammatory activities of black raspberry seed ellagitannins and their structural effects on the stimulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion and intestinal bitter taste receptors. Food Funct 2023, 14, 4049–4064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z; Yang, W; Wu, T.; et al. Long term Coptidis Rhizoma intake induce gastrointestinal emptying inhibition and colon barrier weaken via bitter taste receptors activation in mice. Phytomedicine 2025, 136, 156292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, YY; Xi, RH; Zheng, X.; et al. Signal transduction mechanisms of taste receptors and their regulation on microorganisms. West China Journal of Stomatology 2017, 35, 549–554. [Google Scholar]

- Thangaiyan, R; Sakwe, AM; Hawkins, A.T.; et al. Functional characterization of novel anti-DEFA5 monoclonal antibody clones 1A8 and 4F5 in inflammatory bowel disease colitis tissues. Inflammation Research 2025, 74, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzman, N.H. Paneth cell defensins and the regulation of the microbiome. Gut Microbes 2014, 1, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, L.R.; Knosp, C.; Yeretssian, G. Intestinal antimicrobial peptides during homeostasis, infection, and disease. Frontiers in Immunology 2012, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y; Lian, H; Zhong, X.S.; et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 7 contributes to intestinal barrier dysfunction by degrading tight junction protein Claudin-7. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 131020902–1020902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S; Singh, PP; Singh, A.G.; et al. Anti-diabetic medications and risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013, 108, 510–9; quiz 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, R; Lacour, S; Gautier, J.-C.; et al. Cytokines as potential biomarkers of liver toxicity. Cancer Biomarkers 2005, 1, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, YY; Lu, H; Cui, X.Y.; et al. Interpretation and Discussion on Guiding Principles for Real-World Study Design and Statistical Analysis of Medical Devices. China Food & Drug Administration Magazine 2024, 10, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, AC; Sperber, AD; Corsetti, M.; et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 2020, 396, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.L.; Farias, A.Q.; Rezaie, A. Gastrointestinal motility and absorptive disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: Prevalence, diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2019, 25, 4414–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S; Laskar, JA; Bhowmick, B.; et al. Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease: pathogenesis, gastric microbiome, and innovative therapies. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2025, 49, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Song, F; Yang, M.; et al. Gastrointestinal Dysmotility Predisposes to Colitis through Regulation of Gut Microbial Composition and Linoleic Acid Metabolism. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2306297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Britza, SM; Musgrave, IF; Farrington, R.; et al. Intestinal epithelial damage due to herbal compounds - an in vitro study. Drug Chem Toxicol 2023, 46, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chelakkot, C.; Ghim, J.; Ryu, S.H. Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Exp Mol Med 2018, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T. Regulation of intestinal epithelial permeability by tight junctions. Cell Mol Life Sci 2013, 70, 631–659. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, G.J.; Mullin, J.M.; Ryan, M.P. Occludin: structure, function and regulation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2005, 57, 883–917. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukita, S.; Furuse, M. Occludin and claudins in tight-junction strands: leading or supporting players? Trends Cell Biol 1999, 9, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivinus-Nébot, M; Frin-Mathy, G; Bzioueche, H.; et al. Functional bowel symptoms in quiescent inflammatory bowel diseases: role of epithelial barrier disruption and low-grade inflammation. Gut 2014, 63, 744–752. [Google Scholar]

- Michielan, A.; D'incà, R. Intestinal Permeability in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenesis, Clinical Evaluation, and Therapy of Leaky Gut. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 2015, 628157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, G; Sun, K; Yin, S.; et al. Burn Injury Leads to Increase in Relative Abundance of Opportunistic Pathogens in the Rat Gastrointestinal Microbiome. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, SN; Momeni, N; Chiti, H.; et al. Higher gut Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria population in early pregnancy is associated with lower risk of gestational diabetes in the second trimester. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025, 25, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkovicsné Pézsa, N; Kovács, D; Gálfi, P.; et al. Effect of Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 10415 on Gut Barrier Function, Internal Redox State, Proinflammatory Response and Pathogen Inhibition Properties in Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Patlan, D; Solis-Cruz, B; Pontin, K.P.; et al. Impact of a Bacillus Direct-Fed Microbial on Growth Performance, Intestinal Barrier Integrity, Necrotic Enteritis Lesions, and Ileal Microbiota in Broiler Chickens Using a Laboratory Challenge Model. Front Vet Sci 2019, 6108. [Google Scholar]

- Chavoya-Guardado, MA; Vasquez-Garibay, EM; Ruiz-Quezada, S.L.; et al. Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria in Human Milk and Maternal Adiposity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L; Chai, M; Wang, J.; et al. Bifidobacterium longum relieves constipation by regulating the intestinal barrier of mice. Food Funct 2022, 13, 5037–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, K; Ma, K; Luo, W.; et al. Roseburia intestinalis: A Beneficial Gut Organism From the Discoveries in Genus and Species. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 757718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, XQ; Liu, D; Liu, H.Y.; et al. Prevention of Ulcerative Colitis in Mice by Sweet Tea (Lithocarpus litseifolius) via the Regulation of Gut Microbiota and Butyric-Acid-Mediated Anti-Inflammatory Signaling. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgonje, AR; Feelisch, M; Faber, K.N.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Redox-Modulating Therapeutics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2020, 26, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z; He, Z; Emara, A.M.; et al. Effects of malondialdehyde as a byproduct of lipid oxidation on protein oxidation in rabbit meat. Food Chem 2019, 288, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mandal, M; Mamun, MAA; Rakib, A.; et al. Modulation of occludin, NF-κB, p-STAT3, and Th17 response by DJ-X-025 decreases inflammation and ameliorates experimental colitis. Biomed Pharmacother 2025, 185, 117939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Zhou, J.R. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Epigenetic Alterations in Metabolic Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 985. [Google Scholar]

- Salzman, N.H.; Underwood, M.A.; Bevins, C.L. Paneth cells, defensins, and the commensal microbiota: a hypothesis on intimate interplay at the intestinal mucosa. Semin Immunol 2007, 19, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liszt, KI; Wang, Q; Farhadipour, M.; et al. Human intestinal bitter taste receptors regulate innate immune responses and metabolic regulators in obesity. J Clin Invest 2022, 132, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y; Li, W; Sun, K.; et al. Berberine ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium -induced colitis through tuft cells and bitter taste signalling. BMC Biol 2024, 22, 280. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, RJ; Xiong, G; Kofonow, J.M.; et al. T2R38 taste receptor polymorphisms underlie susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 4145–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, XT; Peng, L; Zeng, J.K.; et al. Research progress on chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Nauclea officinalis and predictive analysis of its quality markers. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica 2024, 49, 2047–2063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, R; Hao, YT; Liu, X.R.; et al. Effect of walnut oligopeptides on digestive function. Chinese Journal of Public Health 2024, 40, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M; Van Liefferinge, E; Navarro, M.; et al. CCK and GLP-1 release in response to proteinogenic amino acids using a small intestine ex vivo model in pigs. J Anim Sci 2022, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M; Xu, C; Navarro, M.; et al. Leucine (and lysine) increased plasma levels of the satiety hormone cholecystokinin (CCK), and phenylalanine of the incretin glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) after oral gavages in pigs. J Anim Sci 2023, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, MA; Patil, K; Ettayebi, K.; et al. Divergent responses of human intestinal organoid monolayers using commercial in vitro cytotoxicity assays. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effects of short-term DM intervention on intestinal morphology and function in rats. (A) Small intestinal propulsion rate, (B) Gastric retention rate, (C) Serum IL-6 levels, (D) Serum TNF-α levels, (E) Representative H&E-stained images of ileal morphology (scale bar = 200 μm), and (F) Representative H&E-stained images of colonic morphology (scale bar = 500 μm). Data are means ± SEM; ns, not significant; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

Figure 1.

Effects of short-term DM intervention on intestinal morphology and function in rats. (A) Small intestinal propulsion rate, (B) Gastric retention rate, (C) Serum IL-6 levels, (D) Serum TNF-α levels, (E) Representative H&E-stained images of ileal morphology (scale bar = 200 μm), and (F) Representative H&E-stained images of colonic morphology (scale bar = 500 μm). Data are means ± SEM; ns, not significant; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

Figure 2.

Effects of long-term DM intervention on the intestinal tract in mice. (A) Serum TNF-α levels. (B) Serum IL-6 levels. (C) Serum IL-1β levels. (D) Serum SOD levels. (E) Serum GSH-Px levels.(F) Serum IFN-γ levels. (G) Serum MDA levels. (H) Relative mRNA expression of Occludin in ileal tissues. (I) Relative mRNA expression of Claudin-1 in ileal tissues.(J) Western blot analysis of Occludin and Claudin-1 protein levels in ileal tissue extracts. (K) Relative protein abundance of Occludin in ileal tissues, normalized to GAPDH. (L) Relative protein abundance of Claudin-1 in ileal tissues, normalized to GAPDH. (M) Representative H&E-stained images of ileal morphology (scale bar = 100 μm).(N) Representative H&E-stained images of colonic morphology (scale bar = 500 μm). Data are means ± SEM; ns, not significant; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

Figure 2.

Effects of long-term DM intervention on the intestinal tract in mice. (A) Serum TNF-α levels. (B) Serum IL-6 levels. (C) Serum IL-1β levels. (D) Serum SOD levels. (E) Serum GSH-Px levels.(F) Serum IFN-γ levels. (G) Serum MDA levels. (H) Relative mRNA expression of Occludin in ileal tissues. (I) Relative mRNA expression of Claudin-1 in ileal tissues.(J) Western blot analysis of Occludin and Claudin-1 protein levels in ileal tissue extracts. (K) Relative protein abundance of Occludin in ileal tissues, normalized to GAPDH. (L) Relative protein abundance of Claudin-1 in ileal tissues, normalized to GAPDH. (M) Representative H&E-stained images of ileal morphology (scale bar = 100 μm).(N) Representative H&E-stained images of colonic morphology (scale bar = 500 μm). Data are means ± SEM; ns, not significant; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

Figure 3.

Effects of long-term DM intervention on α- and β-diversity of gut microbiota in mice. parameters of α-diversity: (A) ACE index, (B) Chao1 index, (C) observed ASVs, (D) Shannon index, (E) Simpson index; (F) principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot of gut microbiota. Data are means ± SEM; ns, not significant; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

Figure 3.

Effects of long-term DM intervention on α- and β-diversity of gut microbiota in mice. parameters of α-diversity: (A) ACE index, (B) Chao1 index, (C) observed ASVs, (D) Shannon index, (E) Simpson index; (F) principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot of gut microbiota. Data are means ± SEM; ns, not significant; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

Figure 4.

Effects of long-term DM intervention on gut microbial composition. (A) Histogram of species composition at the phylum level. (B) Heatmap of species composition at the phylum level. (C) Histogram of species composition at the genus level. (D) Heatmap of species composition at the genus level.

Figure 4.

Effects of long-term DM intervention on gut microbial composition. (A) Histogram of species composition at the phylum level. (B) Heatmap of species composition at the phylum level. (C) Histogram of species composition at the genus level. (D) Heatmap of species composition at the genus level.

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis between gut microbiota alterations and inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarkers. (A) Heatmap of inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarker profiles. Normalization was performed using the ND group as the reference (set to 1). Values >1 indicate upregulation, with increasingly dusty red hues representing stronger upregulation.(B) Correlation analysis between inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarkers and gut microbiota at the phylum level. In the figure legend, colors represent the magnitude of Spearman rank correlation coefficients: ρ = 1 (dusty red) indicates a perfect positive correlation, ρ = -1 (mint green) represents a perfect negative correlation, and ρ = 0 (sandy yellow) denotes no correlation.(C) Correlation analysis between inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarkers and gut microbiota at the genus level. In the figure legend, colors represent the magnitude of Spearman rank correlation coefficients: ρ = 1 (dusty red) indicates a perfect positive correlation, ρ = -1 (mint green) represents a perfect negative correlation, and ρ = 0 (sandy yellow) denotes no correlation. Statistical annotations: ns, not significant; *p< 0.05.

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis between gut microbiota alterations and inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarkers. (A) Heatmap of inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarker profiles. Normalization was performed using the ND group as the reference (set to 1). Values >1 indicate upregulation, with increasingly dusty red hues representing stronger upregulation.(B) Correlation analysis between inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarkers and gut microbiota at the phylum level. In the figure legend, colors represent the magnitude of Spearman rank correlation coefficients: ρ = 1 (dusty red) indicates a perfect positive correlation, ρ = -1 (mint green) represents a perfect negative correlation, and ρ = 0 (sandy yellow) denotes no correlation.(C) Correlation analysis between inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarkers and gut microbiota at the genus level. In the figure legend, colors represent the magnitude of Spearman rank correlation coefficients: ρ = 1 (dusty red) indicates a perfect positive correlation, ρ = -1 (mint green) represents a perfect negative correlation, and ρ = 0 (sandy yellow) denotes no correlation. Statistical annotations: ns, not significant; *p< 0.05.

Figure 6.

Effects of DM on Cell/Tissue Viability and T2R/α-Defensin Expression.(A) Impact of strictosamide on the viability of ex vivo ileal tissues.(B) Effect of DM extract on STC-1 cell viability.(C) Influence of strictosamide on STC-1 cell viability.(D) α-defensin secretion level in ex vivo ileal tissues.(E) α-defensin secretion level in STC-1 cells after treatment with DM extract. (F) α-defensin secretion level in STC-1 cells after treatment with strictosamide.(G) Relative mRNA expression of α-defensin in ileal tissues. (H) Relative mRNA expression of TAS2R108 in ileal tissues. (I) Relative mRNA expression of TAS2R138 in ileal tissues. (J) Western blot analysis of Gα-gustducin protein levels in ileal tissue extracts.(K) Relative protein abundance of Gα-gustducin in ileal tissues normalized to GAPDH. (L) Relative mRNA expression of Gα-gustducin in ileal tissues. Data are means ± SEM; ns, not significant; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01; ***p< 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

Figure 6.

Effects of DM on Cell/Tissue Viability and T2R/α-Defensin Expression.(A) Impact of strictosamide on the viability of ex vivo ileal tissues.(B) Effect of DM extract on STC-1 cell viability.(C) Influence of strictosamide on STC-1 cell viability.(D) α-defensin secretion level in ex vivo ileal tissues.(E) α-defensin secretion level in STC-1 cells after treatment with DM extract. (F) α-defensin secretion level in STC-1 cells after treatment with strictosamide.(G) Relative mRNA expression of α-defensin in ileal tissues. (H) Relative mRNA expression of TAS2R108 in ileal tissues. (I) Relative mRNA expression of TAS2R138 in ileal tissues. (J) Western blot analysis of Gα-gustducin protein levels in ileal tissue extracts.(K) Relative protein abundance of Gα-gustducin in ileal tissues normalized to GAPDH. (L) Relative mRNA expression of Gα-gustducin in ileal tissues. Data are means ± SEM; ns, not significant; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01; ***p< 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

Figure 8.

Schematic experimental design.

Figure 8.

Schematic experimental design.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).