Submitted:

13 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Nerve-Tumor Interaction: A Conceptual Shift

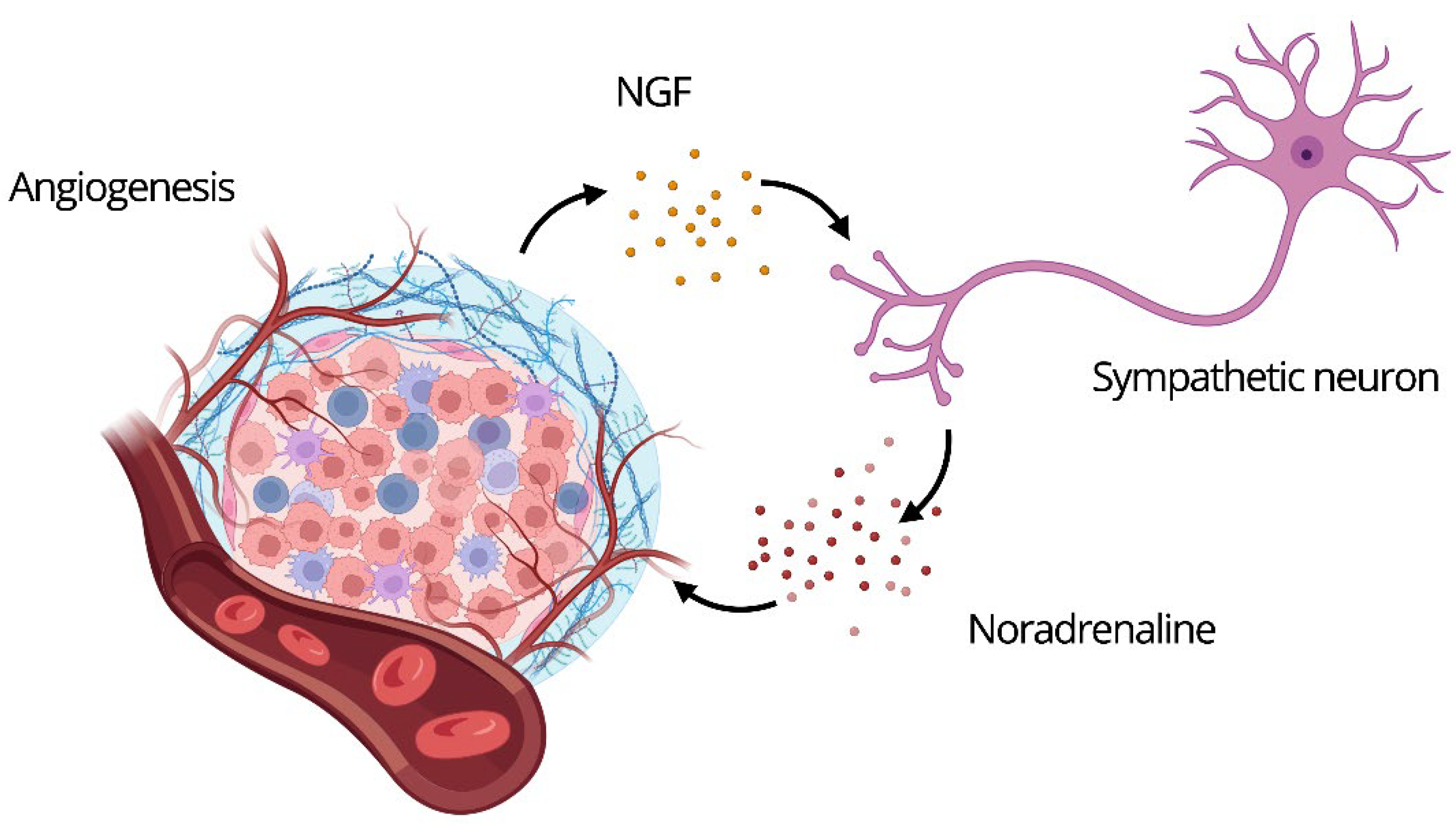

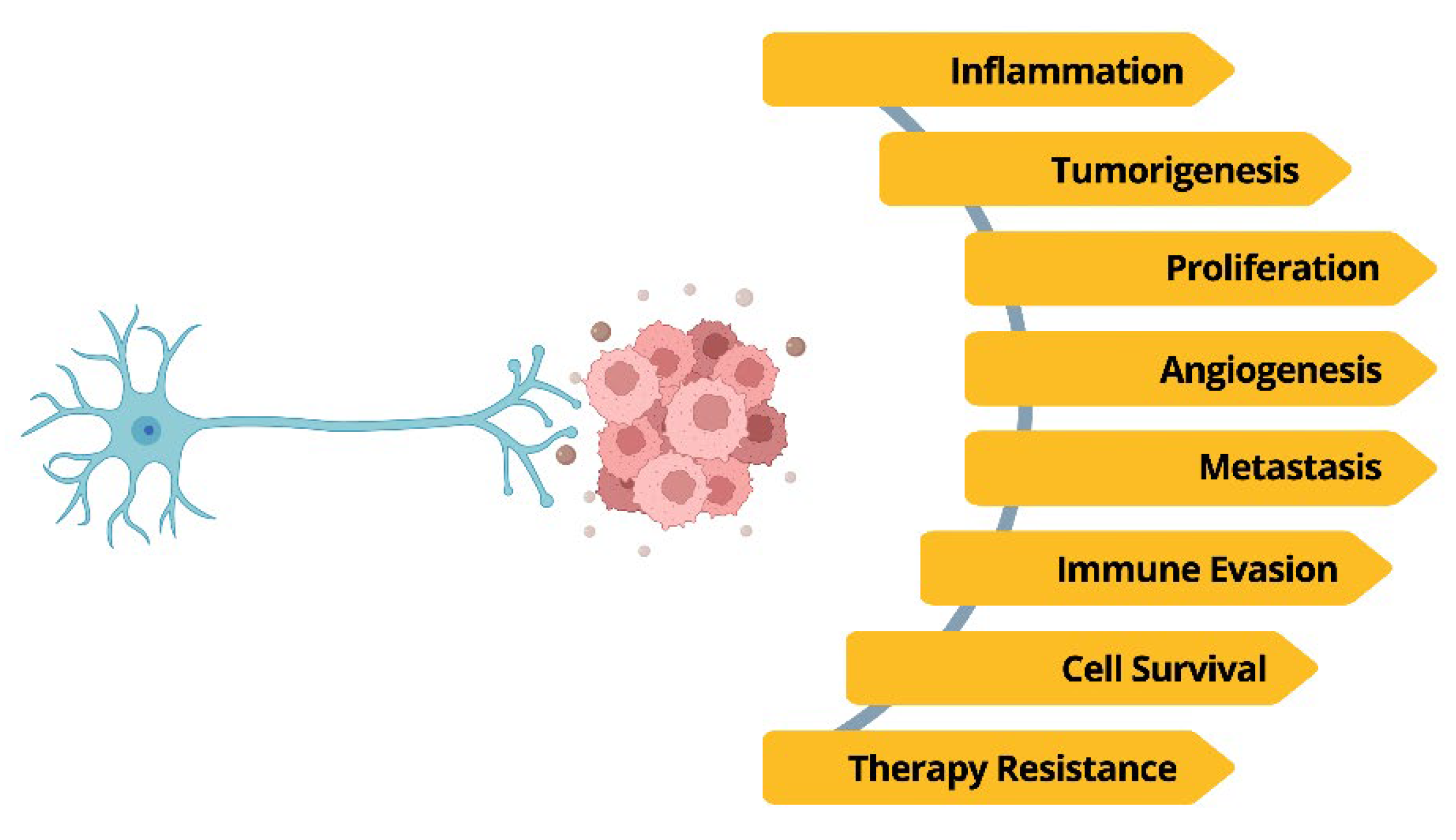

- Neurotransmitter signaling: A shared language of neuroactive molecules (e.g., norepinephrine, acetylcholine) is used by both nerve and tumor cells to control proliferation, angiogenesis, and immunity [7].

- Synaptic-like communication: Direct, functional contacts between neurons and cancer cells enable rapid signal exchange [8]

The Tumor as a Neuro-Integrated Organ

ANS in Oncogenesis: Re-Envisioning a Central Regulator

Sympathetic Overdrive: Fueling the Hallmarks of Cancer

The Vicious Cycle of Adrenergic Dependency

Sympathetic Modulation of Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis

Colorectal Cancer: The Paradox of Sympathetic Signaling

The Adrenergic Axis as a Driver of Liver Cancer Malignancy

Neural Colonizers: The Brain as a Source for Tumor Innervation

“Stress,” What Stress? Redefining Stressors in Cancer Biology

Immune Sabotage: The Sympathetic Hijacking of the Tumor Microenvironment

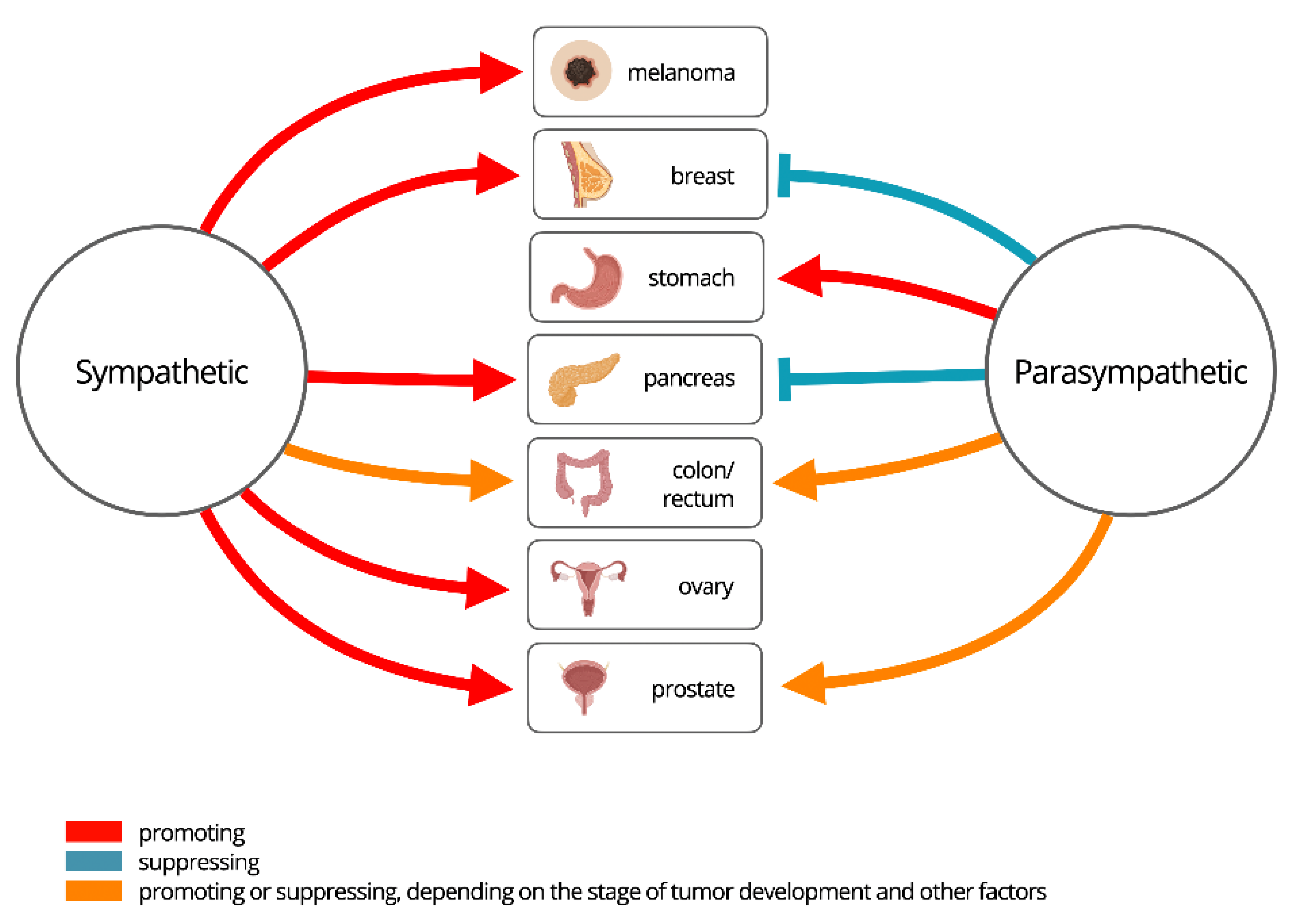

Vagal Duality: The Context-Dependent Role of Parasympathetic Signaling

The Pro-Tumorigenic Face of Parasympathetic Signaling

The Protective Shield: Vagal Tone in Cancer Suppression

Friend or Foe?

| Autonomic branch | Functional Impact on Tumor Biology |

|---|---|

|

Sympathetic (Consistently the "Foe") |

Consistently Pro-Tumorigenic Actions: - Drives tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and metastatic spread. - Orchestrates an immunosuppressive microenvironment and promotes therapy resistance. - Mediates the oncogenic effects of chronic systemic stress. |

|

Parasympathetic (The "Friend and Foe") |

Context-Dependent Duality Pro-Tumorigenic Actions (“Foe”): - Can accelerate proliferation and invasion in specific contexts (e.g., gastric, colon, some pancreatic cancers). Anti-Tumorigenic Actions ("Friend"): - Can inhibit tumor growth and metastasis in other contexts (e.g., breast, certain GI and pancreatic cancers). - Enhances systemic anti-tumor immune responses. |

Neuro-Targeted Therapies: A Paradigm Shift in Cancer Treatment

β-Adrenergic Blockade: Countering Sympathetic Overdrive

Vagal Modulation: Restoring the Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Reflex

Surgical and Chemical Denervation: Dismantling Local Neural Circuits

Local Anesthetics: Multi-Modal Neuroimmune Modulation

The Common Challenge: From Preclinical Promise to Clinical Reality

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, S.H.; Zhang, B.Y.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, C.Z.; Xu, L.Z.; Huang, T. Perineural invasion of cancer: a complex crosstalk between cells and molecules in the perineural niche. Am J Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Zhu, J.; Yu, L.; Huang, Y.; Hu, Y. Cancer-nervous system crosstalk: from biological mechanism to therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, Q.; Wen, X.; Fan, J.; Yuan, T.; Tong, X.; et al. Hijacking of the nervous system in cancer: mechanism and therapeutic targets. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Liang, X.; Tang, Y. Neuroscience in peripheral cancers: tumors hijacking nerves and neuroimmune crosstalk. MedComm 2024, 5, e784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnon, C.; Hall, S.J.; Lin, J.; Xue, X.; Gerber, L.; Freedland, S.J.; et al. Autonomic Nerve Development Contributes to Prostate Cancer Progression. Science 2013, 341, 1236361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahalka, A.H.; Frenette, P.S. Nerves in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2020, 20, 143–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.H.; Hu, L.P.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.G. Neurotransmitters: emerging targets in cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 503–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Song, X.; Shen, H.; et al. Cancer neuroscience in head and neck: interactions, modulation, and therapeutic strategies. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D.A.; Martinez, V.K.; Dougherty, P.M.; Myers, J.N.; Calin, G.A.; Amit, M. Cancer-Associated Neurogenesis and Nerve-Cancer Cross-talk. Cancer Research 2021, 81, 1431–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, S.; Evans, B.A. Does the autonomic nervous system contribute to the initiation and progression of prostate cancer? Asian J Androl. 2013, 15, 715–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, M.; Krishnan, A. The autonomic regulation of tumor growth and the missing links. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 566353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Fan, C.; Shangguan, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Shang, Y.; et al. Neurons generated from carcinoma stem cells support cancer progression. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2017, 2, 16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, H.S. The neural regulation of cancer. Science 2019, 366, 965–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes-Villagrana, R.D.; Albores-García, D.; Cervantes-Villagrana, A.R.; Sánchez-Reyes, J. Tumor-induced neurogenesis and immune evasion as targets of innovative anti-cancer therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020, 5, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, I.; Ağaç Çobanoğlu, D.; Xie, T.; Ye, Y.; Amit, M. Advances in understanding cancer-associated neurogenesis and its implications on the neuroimmune axis in cancer. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2022, 239, 108199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanoun, M.; Maryanovich, M.; Arnal-Estapé, A.; Frenette, P.S. Neural regulation of hematopoiesis, inflammation, and cancer. Neuron 2015, 86, 360–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arese, M.; Bussolino, F.; Pergolizzi, M.; Bizzozero, L.; Pascale, A. Tumor progression: the neuronal input. Ann Transl Med. 2018, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, C.; Phillips, J.A.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Nerve input to tumours: Pathophysiological consequences of a dynamic relationship. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2020, 1874, 188411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahalka, A.H.; Arnal-Estapé, A.; Maryanovich, M.; Nakahara, F.; Cruz, C.D.; Finley, L.W.S.; et al. Adrenergic nerves activate an angio-metabolic switch in prostate cancer. Science 2017, 358, 321–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin, N.; Shurin, G.V.; Baraldi, J.H.; Shurin, M.R. Regulation of Carcinogenesis by Sensory Neurons and Neuromediators. Cancers 2022, 14, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, S.; Jobling, P.; March, B.; Jiang, C.C.; Hondermarck, H. Tumor neurobiology and the war of nerves in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 702–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnon, C.; Hondermarck, H. The neural addiction of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2023, 23, 143–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gysler, S.M.; Drapkin, R. Tumor innervation: peripheral nerves take control of the tumor microenvironment. J Clin Invest. 2021, 131, e147276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeo, M.; Colbert, P.L.; Vermeer, D.W.; Lucido, C.T.; Cain, J.T.; Vichaya, E.G.; et al. Cancer exosomes induce tumor innervation. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albo, D.; Akay, C.L.; Marshall, C.L.; Wilks, J.A.; Verstovsek, G.; Liu, H.; et al. Neurogenesis in colorectal cancer is a marker of aggressive tumor behavior and poor outcomes. Cancer 2011, 117, 4834–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloman, J.L.; Albers, K.M.; Li, D.; Hartman, D.J.; Crawford, H.C.; Muha, E.A.; et al. Ablation of sensory neurons in a genetic model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma slows initiation and progression of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016, 113, 3078–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Kodama, Y.; Muthupalani, S.; Westphalen, C.B.; Andersen, G.T.; et al. Denervation suppresses gastric tumorigenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2014, 6, 250ra115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, Y.; Sakitani, K.; Konishi, M.; Asfaha, S.; Niikura, R.; Tomita, H.; et al. Nerve growth factor promotes gastric tumorigenesis through aberrant cholinergic signaling. Cancer Cell. 2017, 31, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.K.; Armaiz-Pena, G.N.; Nagaraja, A.S.; Sadaoui, N.C.; Ortiz, T.; Dood, R.; et al. Sustained adrenergic signaling promotes intratumoral innervation through BDNF induction. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 3233–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilan, J.; Kitlinska, J. Sympathetic neurotransmitters and tumor angiogenesis—link between stress and cancer progression. J Oncol. 2010, 2010, 539706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.V.; Kim, S.J.; Donovan, E.L.; Chen, M.; Gross, A.C.; Webster Marketon, J.I.; et al. Norepinephrine upregulates VEGF, IL-8, and IL-6 expression in human melanoma tumor cell lines: implications for stress-related enhancement of tumor progression. Brain Behav Immun. 2009, 23, 267–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, A.; Hiyama, T.; Fujimura, A.; Yoshikawa, S. Sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation in cancer: therapeutic implications. Clin Auton Res. 2021, 31, 165–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amit, M.; Baruch, E.; Nagarajan, P.; Gleber-Netto, F.; Rao, X.; Xie, T.; et al. Inflammation induced by tumor-associated nerves promotes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in cancer patients and is targetable by IL-6 blockade. PREPRINT 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, G.; Chen, M.; Bucsek, M.J.; Repasky, E.A.; Hylander, B.L. Adrenergic Signaling: A Targetable Checkpoint Limiting Development of the Antitumor Immune Response. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.F.; Jin, F.J.; Li, N.; Guan, H.T.; Lan, L.; Ni, H.; et al. Adrenergic receptor β2 activation by stress promotes breast cancer progression through macrophages M2 polarization in tumor microenvironment. BMB Reports 2015, 48, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizil, B.; De Virgiliis, F.; Scheiermann, C. Neural control of tumor immunity. The FEBS Journal. 2024, 291, 4670–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, X.; Yang, S.; Wei, S.; Fan, Q.; Liu, J.; et al. Targeting tumor innervation: premises, promises, and challenges. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huo, R.; He, K.; Li, W.; Gao, Y.; He, W.; et al. Increased nerve density adversely affects outcome in colorectal cancer and denervation suppresses tumor growth. J Transl Med. 2025, 23, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Pacheco, C.; Schmitd, L.B.; Furgal, A.; Bellile, E.L.; Liu, M.; Fattah, A.; et al. Increased Nerve Density Adversely Affects Outcome in Oral Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2023, 29, 2501–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.R.; Jordan, M.; Nagarajan, P.; Amit, M. Nerve Density and Neuronal Biomarkers in Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitd, L.B.; Perez-Pacheco, C.; D’Silva, N.J. Nerve density in cancer: Less is better. FASEB BioAdvances 2021, 3, 773–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, G.A.; Shiralkar, J.; Suciu, D.; Covarrubias, G.; Yu, J.S.; Karathanasis, E.; et al. Chronic neural activity recorded within breast tumors. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 14824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z.; Yin, K.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; et al. Chronic stress promotes gastric cancer progression and metastasis: an essential role for ADRB2. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Yan, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, E.K.; Priceman, S.J.; Cox, B.F.; Yu, S.; Pimentel, M.A.; Tangkanangnukul, V.; et al. The sympathetic nervous system induces a metastatic switch in primary breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 7042–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, J.T.; Moussa, M.; Corwin, W.L.; Mandoiu, I.I.; Srivastava, P.K. Sympathetic nervous tone limits the development of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Sci Immunol. 2020, 5, eaay9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, S. Vagus nerve stimulation: Novel concept for the treatment of glioblastoma and solid cancers by cytokine (interleukin-6) reduction, attenuating the SASP, enhancing tumor immunity. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health 2024, 42, 100859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.P.; Calaf, G.M. Acetylcholine, Another Factor in Breast Cancer. Biology 2023, 12, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbro, D.S. Do neuro-humoral signaling molecules participate in colorectal carcinogenesis/cancer progression? Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2012, 24, 96–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Liang, X.; Du, G.; Liu, L.; Lu, L.; et al. The clinicopathological significance of neurogenesis in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, K.; Wittels, H.L.; Wishon, M.J.; Lee, S.J.; McDonald, S.M.; Wittels, Howard S. Tracking Cancer: Exploring Heart Rate Variability Patterns by Cancer Location and Progression. Cancers 2024, 16, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.R.; Jordan, M.; Nagarajan, P.; Amit, M. Nerve density and neuronal biomarkers in cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mravec, B.; Dubravicky, J.; Tibensky, M.; Horvathova, L. Effect of the nervous system on cancer: Analysis of clinical studies. BLL 2019, 120, 119–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonkeren, S.L.; Thijssen, M.S.; Vaes, N.; Boesmans, W.; Melotte, V. The Emerging Role of Nerves and Glia in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, A.; Wong, T.W.L.; Ng, S.S.M. Putative role of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in cancer pathology and immunotherapy: Can this be a hidden treasure, especially for the elderly? Cancer Medicine 2023, 12, 19081–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurin, M.R.; Shurin, G.V.; Zlotnikov, S.B.; Bunimovich, Y.L. The neuroimmune axis in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol. 2020, 204, 280–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Smith, M.; Lutgendorf, S.K.; Sood, A.K. Impact of stress on cancer metastasis. Future Oncol. 2010, 6, 1863–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.K.; Bhatty, R.; Kamat, A.A.; Landen, C.N.; Han, L.; Thaker, P.H.; et al. Stress Hormone–Mediated Invasion of Ovarian Cancer Cells. Clinical Cancer Research 2006, 12, 369–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaker, P.H.; Han, L.Y.; Kamat, A.A.; Arevalo, J.M.; Takahashi, R.; Lu, C.; et al. Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat Med. 2006, 12, 939–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, B.; Liao, Q.; Zhou, M.; et al. Chronic stress promotes cancer development. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Karpova, Y.; Baiz, D.; Yancey, D.; Pullikuth, A.; Flores, A.; et al. Behavioral stress accelerates prostate cancer development in mice. J Clin Invest. 2013, 123, 874–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, S.L.; Benlloch, M.; Rodriguez, M.L.; Mena, S.; Pellicer, J.A.; Asensi, M.; et al. Stress hormones promote growth of B16-F10 melanoma metastases: an interleukin 6- and glutathione-dependent mechanism. J Transl Med. 2013, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, S.W.; Nagaraja, A.S.; Lutgendorf, S.K.; Green, P.A.; Sood, A.K. Sympathetic nervous system regulation of the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer 2015, 15, 563–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, J.W.L.; Kokolus, K.M.; Reed, C.B.; Hylander, B.L.; Ma, W.W.; Repasky, E.A. A nervous tumor microenvironment: the impact of adrenergic stress on cancer cells, immunosuppression, and immunotherapeutic response. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014, 63, 1115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnon, C. Role of the autonomic nervous system in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Molecular & Cellular Oncology 2015, 2, e975643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, G.E.; Dai, H.; Powell, M.; Li, R.; Ding, Y.; Wheeler, T.M.; et al. Cancer-related axonogenesis and neurogenesis in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 7593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.W.; Sood, A.K. Molecular pathways: beta-adrenergic signaling in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 1201–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cao, R.; Ma, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Beta-adrenergic signaling on neuroendocrine differentiation, angiogenesis, and metastasis in prostate cancer progression. Asian J Androl. 2019, 21, 253–9. [Google Scholar]

- Braadland, P.R.; Ramberg, H.; Grytli, H.H.; Taskén, K.A. β-adrenergic receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Front Oncol. 2015, 4, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, B.W.; Takahashi, R.; Tanaka, T.; Macchini, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Datta, M.; et al. β2 adrenergic-neurotrophin feedforward loop promotes pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018, 33, 75–90.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdoushi, A.; Griffin, N.; Marsland, M.; Xu, X.; Faulkner, S.; Gao, F.; et al. Tumor innervation and clinical outcome in pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.F.; Bretes, L.; Furtado, I. Correlation of beta-2 adrenergic receptor expression in tumor-free surgical margin and at the invasive front of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oncol. 2016, 2016, 1651467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makale, M.T.; Kesari, S.; Wrasidlo, W. The autonomic nervous system and cancer. J Drug Target. 2017, 25, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüthy, I.A.; Bruzzone, A.; Piñero, C.P.; Castillo, L.F.; Chiesa, I.J.; Vázquez, S.M.; et al. Adrenoceptors: non conventional target for breast cancer? Curr Med Chem. 2009, 16, 1850–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creed, S.J.; Le, C.P.; Hassan, M.; Pon, C.K.; Albold, S.; Chan, K.T.; et al. β2-adrenoceptor signaling regulates invadopodia formation to enhance tumor cell invasion. Breast Cancer Res. 2015, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, F.; Sousa, D.M.; Loessberg-Zahl, J.; Neto, E.; Porcino, C.; Salgado, A.; et al. Sympathetic activity in breast cancer and metastasis: partners in crime. Bone Res. 2021, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauffrey, P.; Tchitchek, N.; Barroca, V.; Mallavialle, A.; Castagné, R.; Goulard, M.; et al. Neural progenitors from the central nervous system infiltrate prostate tumors to promote development and metastasis. Nat Cancer 2019, 1, 167–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Fuchs, C.; Le, C.P.; Pimentel, M.A.; Shackleford, D.; Ferrari, D.; Angst, E.; et al. Chronic stress accelerates pancreatic cancer growth and invasion. Gut 2014, 63, 1313–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nissen, M.D.; Sloan, E.K.; Mattarollo, S.R. β-adrenergic signaling impairs antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses to B-cell lymphoma immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018, 6, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuol, N.; Stojanovska, V.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Nurgali, K. Crosstalk between cancer and the neuro-immune system. J Neuroimmunol. 2018, 315, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xia, H.; Tang, Q.; Xu, H.; Wei, G.; Chen, Y.; et al. Acetylcholine acts through M3 muscarinic receptor to activate the EGFR signaling and promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 40802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schledwitz, A.; Xie, G.; Raufman, J.P. Differential actions of muscarinic receptor subtypes in gastric, pancreatic, and colon cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 13153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.; Samimi, R.; Xie, G.; Shant, J.; Drachenberg, C.; Wade, M.; et al. Acetylcholine release by human colon cancer cells mediates autocrine stimulation of cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008, 295, G591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renz, B.W.; Tanaka, T.; Sunagawa, M.; Takahashi, R.; Jiang, Z.; Macchini, M.; et al. Cholinergic signaling via muscarinic receptors directly and indirectly suppresses pancreatic tumorigenesis and cancer stemness. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1458–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partecke, L.I.; Käding, A.; Trung, D.N.; Diedrich, S.; Sendler, M.; Weiss, F.; et al. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy promotes tumor growth and reduces survival via TNFα in a murine pancreatic cancer model. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 22501–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang WB, Lai H zhou, Long J, Ma Q, Fu X, You FM; et al. Vagal nerve activity and cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin, N.; Barkan, T.; Akcan, G.; Yorukoglu, K. Activation of vagus nerve by semapimod alters substance P levels and decreases breast cancer metastasis. Regul Pept. 2012, 179(1-3), 101–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, R.; Bunimovich, Y.L. The nervous system: a new target in the fight against cancer. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2018, 29, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fæstad, A.A.; Galván, J.A.; Schürch, C.M.; Seifert, B.; Zlobec, I.; Krebs, P.; et al. Blockade of beta-adrenergic receptors reduces cancer growth and enhances the response to anti-CTLA4 therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Oncogene 2022, 41, 1364–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, D.; Winklewski, P.J.; Gruszecka, A.; Rudzinska, M.; Kucharska, A.; Markuszewski, L.; et al. Blockage of cholinergic signaling via muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 3 inhibits tumor growth in human colorectal adenocarcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 12358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Moz, M.; Correia, G.; Teixeira, A.; Medeiros, R.; Ribeiro, L. β-adrenergic modulation of cancer cell proliferation: available evidence and clinical perspectives. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017, 143, 275–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumaria, A.; Ashkan, K.; Powell, M.P.; Solo, A.; Hanrahan, J.G.; Bhangoo, R.; et al. Neuromodulation as an anticancer strategy. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1264619. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Lu, X.; Yan, C. Neuro-immune-cancer interactions: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications for tumor modulation. Brain Behavior and Immunity Integrative 2025, 10, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloman, J.L.; Albers, K.M.; Rhim, A.D.; Davis, B.M. Can stopping nerves, stop cancer? Trends Neurosci. 2016, 39, 880–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsou, G.; Burke, O.; Ashok, D.; Hewage, S.; Jobling, P.; Chuah, P.; et al. Radical tumor denervation activates potent local and global cancer treatment. Cancers 2023, 9, eadi8236. [Google Scholar]

- Piegeler, T.; Votta-Velis, E.G.; Bakhshi, F.R.; Mao, M.; Carnegie, G.; Bonini, M.G.; et al. Do amide local anesthetics play a therapeutic role in the perioperative management of cancer patients? Int Anesth Res Soc. 2016, 122, 1994–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M.; Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Yang, L.; Fan, Q.; Wang, Z.; et al. Regional anesthesia might reduce recurrence and metastasis rates in adult patients with cancers after surgery: a meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Rodriguez, S.; Dono, A.; Bonnin, D.; Nunez-Castilla, J.; Sheth, S.A.; Esquenazi, Y. Local anesthetics, regional anesthesia and cancer biology. J Neurooncol 2025, 166, 209–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cassinello, F.; Prieto, I.; del Olmo, M.; Rivas, S.; Strichartz, G.R. Cancer surgery: how may anesthesia influence outcome? J Clin Anesth. 2015, 27, 262–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, C. Local Anesthetics as…Cancer Therapy? Anesthesia & Analgesia 2018, 127, 601–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krömer, A.; Farag, M.; Birkenhauer, U.; Stadler, A.; Mueller, J.E.; Zeman, F.; et al. Local anesthetics affect tumor biology in an ex vivo tissue model of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5594. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Jing, Y.; Pan, R.; Ding, K.; Chen, R.; Meng, Q. Mechanisms of Cancer Inhibition by Local Anesthetics. Front Pharmacol 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezu, L.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G. Immunogenic stress induced by local anesthetics injected into neoplastic lesions. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2043672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezu, L.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G. Local anesthetics elicit immune-dependent anticancer effects. J Immunother Cancer 2022, 10, e004607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezu, L.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G. Impact of local anesthetics on epigenetics in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 15583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, B.; Jia, Y.; Qiu, G.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; et al. Expression and significance of autonomic nerves and α9 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in colorectal cancer. Molecular Medicine Reports 2018, 17, 8423–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Kong, X.; Sun, X. Nervous system in hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation, mechanisms, therapeutic implications, and future perspectives. BBA Rev Cancer 2025, 1880, 189345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaatti, A.; Buggy, D.J.; Wall, T.P. Local anaesthetics and chemotherapeutic agents: a systematic review of preclinical evidence of interactions and cancer biology. BJA Open. 2024, 10, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa, A.L.; Ciocan, A.; Zaharie, F.; Valean, D.; Sargarovschi, S.; Breazu, C.; Al Hajjar, N.; Ionescu, D. The Influence of Intravenous Lidocaine Infusion on Postoperative Outcome and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Colorectal Cancer Patients. A Pilot Study. JGLD [Internet] cited. 2023, 32, 156–61. [Google Scholar]

| Topic | Traditional View | New Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Role of the ANS in oncogenesis | The ANS was considered irrelevant to oncogenesis; cancer was thought to result solely from genetic mutations and environmental factors. | Modern techniques reveal dense sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation in various tumors, influencing tumor initiation and progression.[25,52,29,33,17,53,54] |

| Role of nerve fibers in tumors | Nerve fibers were seen as passive targets of tumor invasion (perineural invasion). | PNI is now recognized as an active mechanism of tumor dissemination, with nerve-derived signals enhancing cancer cell migration.[55,25,52,29,33] |

| Neurogenesis in the tumor context | Neurogenesis was thought to occur exclusively in the CNS and was unrelated to tumors. | Tumor stem cells can differentiate into functional neurons and contribute to neoneurogenesis within the tumor microenvironment.[12] |

| Origin of tumor-associated nerve fibers | Nerve fibers in tumors were believed to originate only from adjacent tissues. | Human CSCs produce functional autonomic neurons that integrate into the tumor stroma and modulate cancer progression.[12] |

| Impact of the ANS on antitumor immunity | Immunity was believed to be regulated exclusively by the immune system, with no neuronal contribution. | The vagus nerve modulates immune response via cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathways; adrenergic signaling affects myeloid-derived cells.[55,29,33,46,56] |

| Neurotransmitters and cancer | Neurotransmitters were viewed solely as synaptic messengers with no role in cancer biology. | Dopamine, GABA, glutamate, and serotonin directly influence tumor proliferation, immune evasion, and vascular remodeling.[7] |

| Psycho-emotional influence on cancer | Stress and emotional states were considered psychosocial factors without biological relevance in cancer progression. | Chronic stress activates the sympathetic system, increasing norepinephrine and promoting tumor growth and metastasis.[43,57,58,59,60,61,35,62] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).