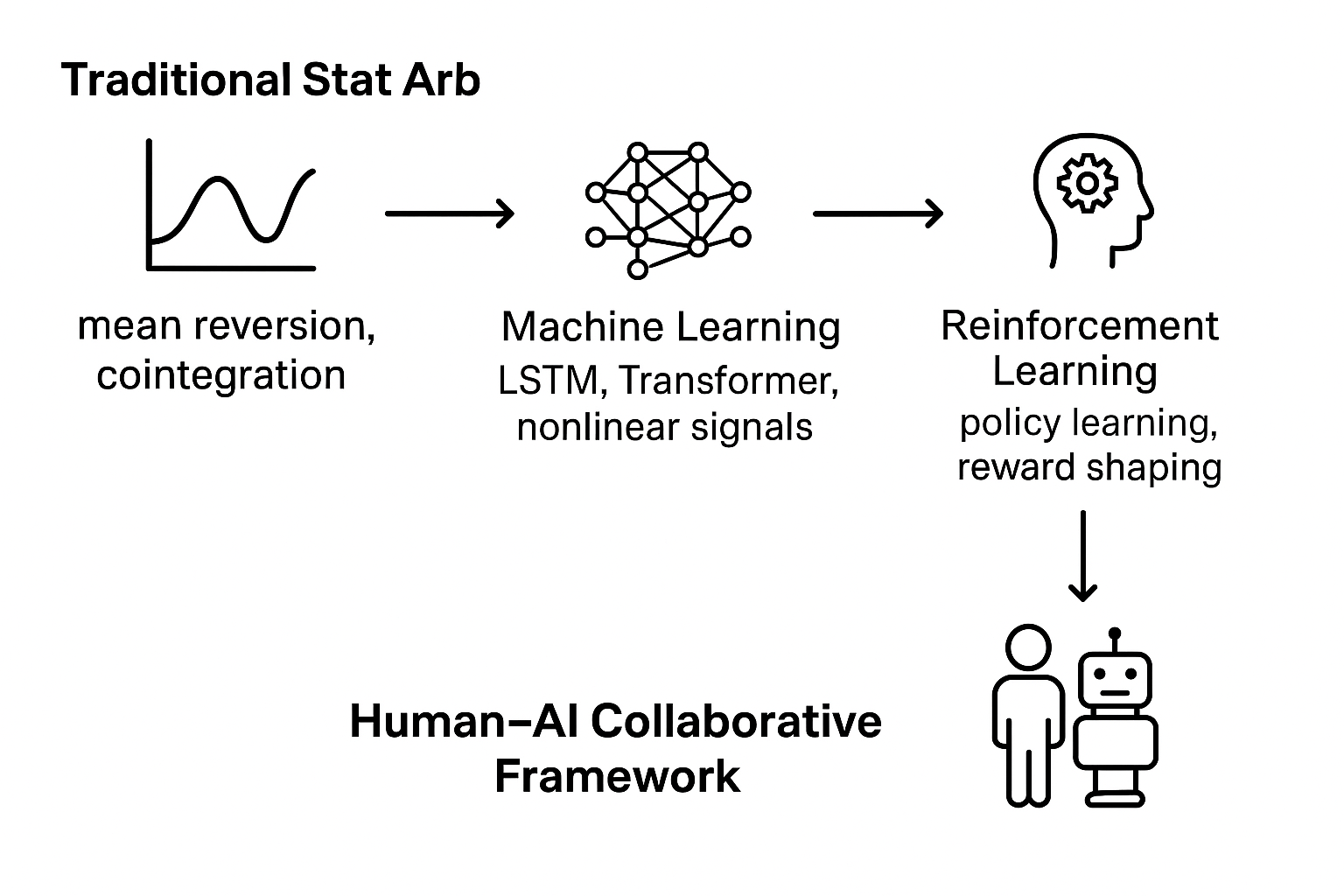

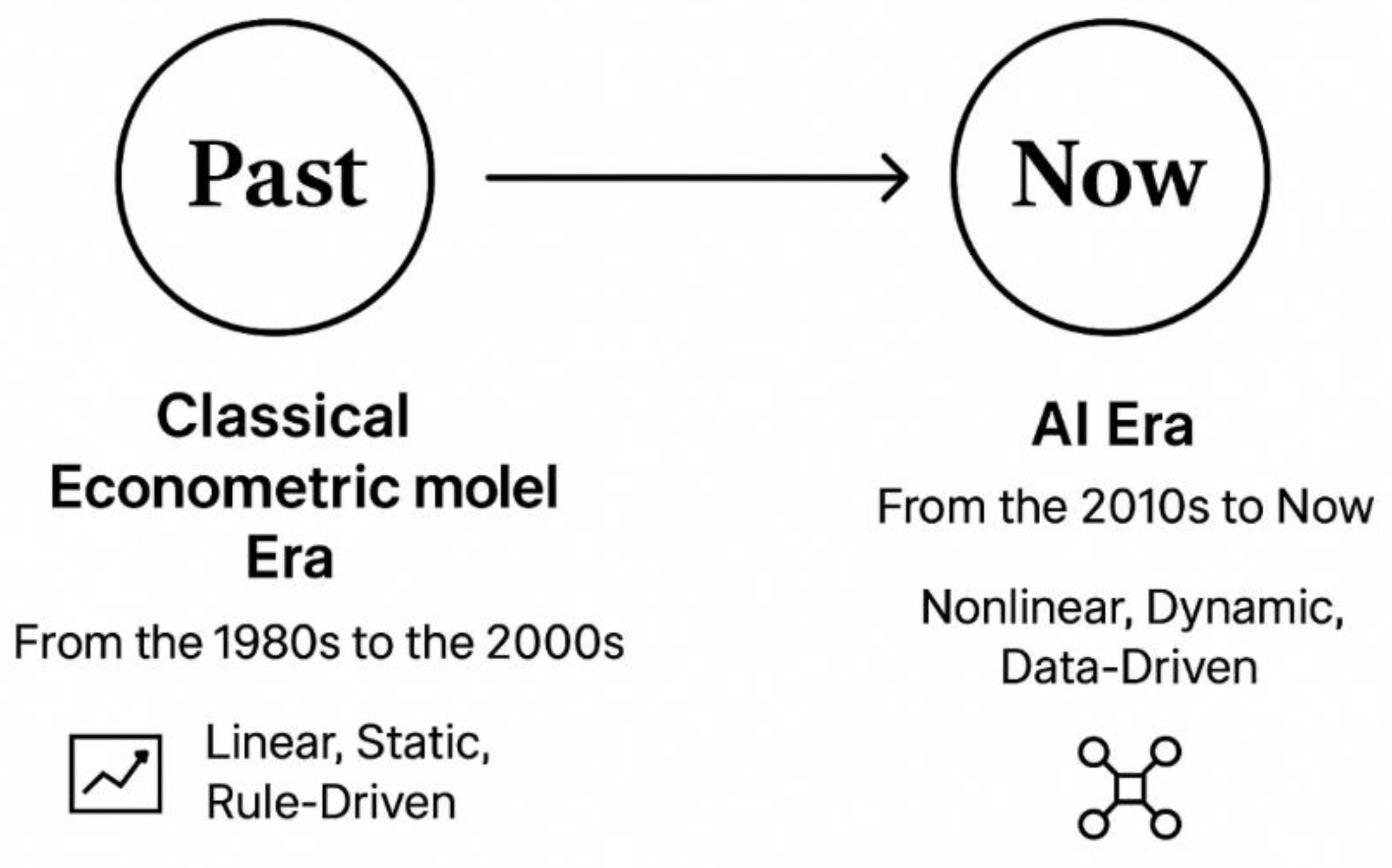

The previous sections thoroughly discussed the theoretical basis and core contradictions of statistical arbitrage. In the long run, these characteristics remain almost unchanged. In recent years, they have changed little and evolved slowly. On the contrary, the iterative development of statistical arbitrage methods is closely related to the transformation of the financial market structure, the breakthrough of measurement technology and the progress of computing power. In this era of rapid artificial intelligence and information technology, its evolution is rapid and change. From a comprehensive academic and practical perspective, this evolution can be clearly divided into two main stages: the era of classical econometric models (1980s-2000s) and the era of artificial intelligence (2010s-now). The era of classical econometric models is based on linear hypotheses and structured modeling frameworks, while the era of artificial intelligence broke the previous technical boundaries through large-scale multi-dimensional data-driven nonlinear learning. These two eras have jointly promoted the return of statistical arbitrage from simple computation to a multi-dimensional intelligent decision-making model.

Exhibits 1.

The evolution of statistical arbitrage across eras.

2.3. Statistical Arbitrage in the Era of Classical Econometric Model

The core logic of statistical arbitrage in the era of classical econometric models can be generally summarized as: “Identify stable statistical relationships between assets, Model the mean-reversion process of spreads, Design arbitrage signal triggering mechanisms.” Its technical framework centers primarily on these three key breakthroughs. To transform statistical arbitrage from the theoretical premise of “market imperfect efficiency” into an executable quantitative trading strategy, one must follow six progressive steps: Data Preprocessing, Statistical Relationship Identification, Factor and Dimension Optimization, Dynamic Forecasting and Signal Capture, Volatility and Risk Control, and Deepening Multivariate Dependencies. Through ongoing refinement via methodologies such as econometrics and mathematics, the strategy ultimately satisfies three core criteria: statistical significance, out-of-sample robustness, and adaptability to market friction. In the sections that follow, these six steps will be deconstructed in sequence in line with technical logic, elaborating on how robust technical methods boost the rationality and effectiveness of quantitative strategies—thereby facilitating more straightforward implementation and enabling the achievement of meaningful returns.

The rise of classic statistical arbitrage models was no accident, but rather the combined result of the “quantitative revolution” and rapid breakthroughs in econometrics during the 1970s. At that time, the academic groundwork for statistical arbitrage was primarily laid in econometrics laboratories at U.S. universities (led by institutions like MIT and UC San Diego), while its practical application took root in quantitative hedge funds on Wall Street. The U.S. stock market had already developed relatively sophisticated trading mechanisms, yet investor sophistication remained relatively low (primarily relying on fundamental analysis). Coupled with the rapid advancement of computing power, these factors provided crucial conditions for the successful implementation of statistical arbitrage. The development of classic statistical arbitrage models during this period was primarily established by leading econometricians, such as 2003 Nobel laureate Robert F. Engle (University of California, San Diego) and Clive W.J. Granger (University of East Anglia, UK, long-term researcher in the US), along with Danish econometrician Søren Johansen (University of Copenhagen, closely collaborating with US academia). Their research laid the cornerstone for the traditional econometric era.

2.3.1. Data Preprocessing

Data preprocessing is a foundational step in constructing statistical arbitrage strategies, as it addresses critical data quality issues. The priority of data preprocessing lies in systematically addressing the four critical inherent flaws in financial market data: non-stationarity, outlier interference, dimensional heterogeneity, and high-frequency noise pollution. Failing to resolve these flaws will significantly impact the subsequent construction of investment strategies. Therefore, data preprocessing must adhere to principles of statistical rigor and financial market applicability, enhancing data quality through multiple steps. Key methods include data cleaning, stationarity adjustment, normalization, and noise reduction. Collectively, these ensure data authenticity, stability, and signal-to-noise ratio, laying a solid foundation for statistical arbitrage model construction.

Data Cleaning: During the process of collecting financial data, outliers may easily occur due to reasons like liquidity gaps, extreme investor trading behavior, or trading software malfunctions. Missing values may arise from individual stock suspensions or data interface interruptions. Data cleaning adheres to the principle of accurately identifying anomalies and reasonably filling missing values to prevent subsequent statistical models from being compromised by data issues. The most common method for identifying outliers is Median Absolute Deviation (MAD), which measures dispersion based on the median (rather than the mean) of the data. This significantly mitigates the interference from extreme values (Rousseeuw & Croux, 1993). The formula is:

The smaller the MAD value, the lower the degree of data dispersion. For missing data, the most commonly used method is K-Nearest Neighbor Interpolation (Troyanskaya et al., 2001). Its core logic involves using the information from the K most similar “complete samples” to the sample with the missing value to estimate the missing value. This approach significantly resolves the issues caused by data missingness.

Stationarity: As the name suggests, data stationarity addresses the issue of “non-stationarity” in data. Non-stationary sequences can cause spurious regression in traditional econometric models, undermining their reliability. One core method involves using the ADF test to determine whether a time series contains a “unit root,” thereby establishing its stationarity (presence of a unit root indicates non-stationarity, absence indicates stationarity) (Dickey & Fuller, 1979). Its core formula is:

Null hypothesis H₀: γ = 0 (unit root exists → sequence is non-stationary);

If the calculated test statistic (t-value) is less than the critical value, reject H₀ → no unit root, sequence is stationary;

If t-value ≥ critical value, cannot reject H₀ → unit root exists, sequence is non-stationary and requires differencing to achieve stationarity.

Standardization and Noise Reduction: In statistical arbitrage data preprocessing, “standardization” and “noise reduction” are two inseparable and closely interconnected processes, hence they are introduced together here. Standardization primarily addresses weighting biases caused by inconsistent units of measurement, while noise reduction eliminates interference from high-frequency data. Together, they ensure the accuracy of subsequent modeling steps (e.g., factor screening, similarity calculations). The core of standardization is transforming all features into a distribution with “mean 0 and standard deviation 1.” The most typical method is Z-score standardization. The Z-score standardization formula is:

For high-frequency data denoising, the most commonly used method is the Kalman filter for dynamically estimating true prices (De Moura et al., 2016). Its core logic involves dynamically iterating to estimate the optimal true price through “state equations” and “observation equations.” In short, it combines two equations to derive a third, achieving a synergistic effect where 1+1 > 2.

2.3.2. Statistical Relationship Identification

The core of statistical arbitrage lies in recognizing quantifiable mean-reversion asset correlations, that is to identify the possible statistical relationships between assets. Only assets exhibiting these characteristics can ensure a strategy’s sustainable profitability. Simultaneously, statistical relationships must undergo rigorous validity testing to prevent overfitting or in-sample coincidental strategies that could cause the strategy to collapse in actual trading. In the era of classical models, we often capture the linear relationships between assets.

Classic Linear Relationship (Cointegration): To test whether two assets exhibit a long-term cointegration relationship, the Engle-Granger two-step method (R. F. Engle & Granger, 1987) is typically employed. It is broadly divided into two steps:

Step 1: Dual-asset cointegration regression, with the basic formula as follows:

Step 2: Residual Stationarity Test (ADF Test Core Formula (0)), whose basic formula is:

To examine the cointegration relationship among two or more assets, the Johansen maximum likelihood method (Johansen, 1988) is typically employed. Its fundamental VAR model is:

2.3.3. Factor and Dimension Optimization

After completing the basic works, the next step is naturally to customize and optimize the model. In statistical arbitrage, this step corresponds to optimizing factors and dimensions. In this phase, we focus on two core directions: “screening effective factors” and “streamlining dimensions.” This approach allows us to extract strong, uncorrupted core signals from messy data, enabling subsequent models to operate with greater precision and deliver more reliable outcomes.

Factor Screening: Grinold and Kahn (2000) proposed using the Information Content (IC) to screen high-information factors (Vergara & Kristjanpoller, 2024), with the formula defined as:

Among these, |IC| > 0.1 and p < 0.05 indicate a high-information factor.

Dimension Reduction: In the dimension reduction process, PCA (Caneo & Kristjanpoller, 2021) is commonly used for linear relationships. The core of PCA dimension reduction involves calculating the covariance matrix of the data, solving for its eigenvalues and eigenvectors, then selecting principal components that collectively explain over 80% of the cumulative variance. These principal components replace the original high-dimensional data, achieving dimension reduction while preserving key information. For non-linear relationships, t-SNE is frequently employed. Its primary steps involve mapping the “similarity” (often expressed probabilistically) of data points in high-dimensional space to a low-dimensional space. This ensures similar data points cluster closely together in the low-dimensional space, while dissimilar points remain distant. Consequently, this achieves dimensionality reduction for high-dimensional non-linear data.

2.3.4. Dynamic Forecasting and Signal Capture

After completing the preliminary work, dynamic forecasting and signal capture constitute the subsequent analytical phase based on optimized core features. This represents the critical stage for strategy implementation, achieving the core transition from “static rules” to “intelligent decision-making.” The following sections will break down this crucial phase in detail.

In classical static signal components, cointegration spreads form their core foundation. The specific methodology generally involves first identifying financial assets with long-term correlations, then calculating the price spreads between them. The spread formula is:

Then, based on the mean and volatility of the spread, a fixed threshold is set (typically 1.5 times the standard deviation above or below the mean). When the spread breaches this threshold, an arbitrage signal is triggered (Elliott et al., 2005). This approach implements relatively stable static rule-based trading based on the core principle that “spreads will eventually revert to the mean.”

2.3.5. Volatility and Risk Control

For a quantitative strategy to be valuable, its profitability must be sustainable. Precise assessment of market volatility and effective mitigation of extreme risks are central to achieving this sustained profitability. As a critical step for stable returns in quantitative strategies, this process provides robust assurance for strategy implementation through quantitative risk measurement and dynamic portfolio rebalancing. Regarding quantitative risk and risk management, this section will delve into two key aspects: risk measurement and dynamic control.

Risk Measurement: In the process of quantifying risk, volatility modeling is a commonly used approach. The most typical methods involve characterizing volatility through GARCH models and SV models. The GARCH model equation is:

The SV model is often used as a supplement to the GARCH model. When combined into a GARCH-SV model, it retains the GARCH model’s ability to capture volatility clustering while incorporating the SV model’s description of random changes in volatility, enabling the calculation of a more accurate asset volatility.

With volatility

available, risk can be measured using Value at Risk (VaR) and Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) methods.

In this method, F is the distribution function of asset returns, and this equation represents a 95% probability that losses will not exceed this value (this equation measures the maximum potential loss).

This method measures the average level of extreme losses (at a confidence level σ) that occur when losses exceed VaR.

In short, the GARCH-SV model calculates more precise volatility, while methods using VaR and CVaR quantify the maximum possible loss of an investment and the average level of loss under extreme conditions.

Dynamic Control: After obtaining the aforementioned risk quantification results, we directly link the quantified risk to actual positions using a specific formula, providing a clear basis for dynamic position control. This formula is:

The target risk here essentially refers to the predetermined maximum risk an investor can tolerate. Dividing this by the current asset volatility yields the position size, which represents the actual capital allocation ratio. Using this approach, we can adjust holdings through quantitative strategies based on our risk tolerance (Bollerslev, 1986).

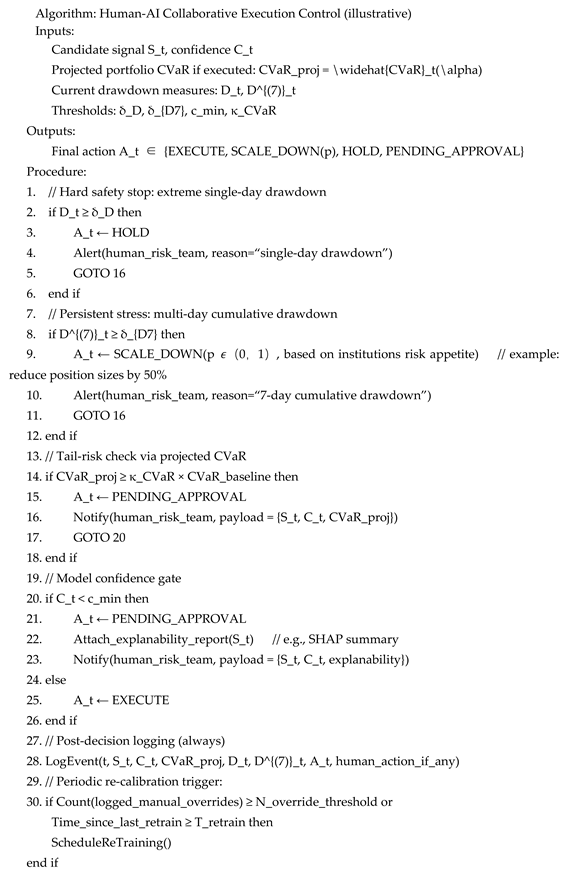

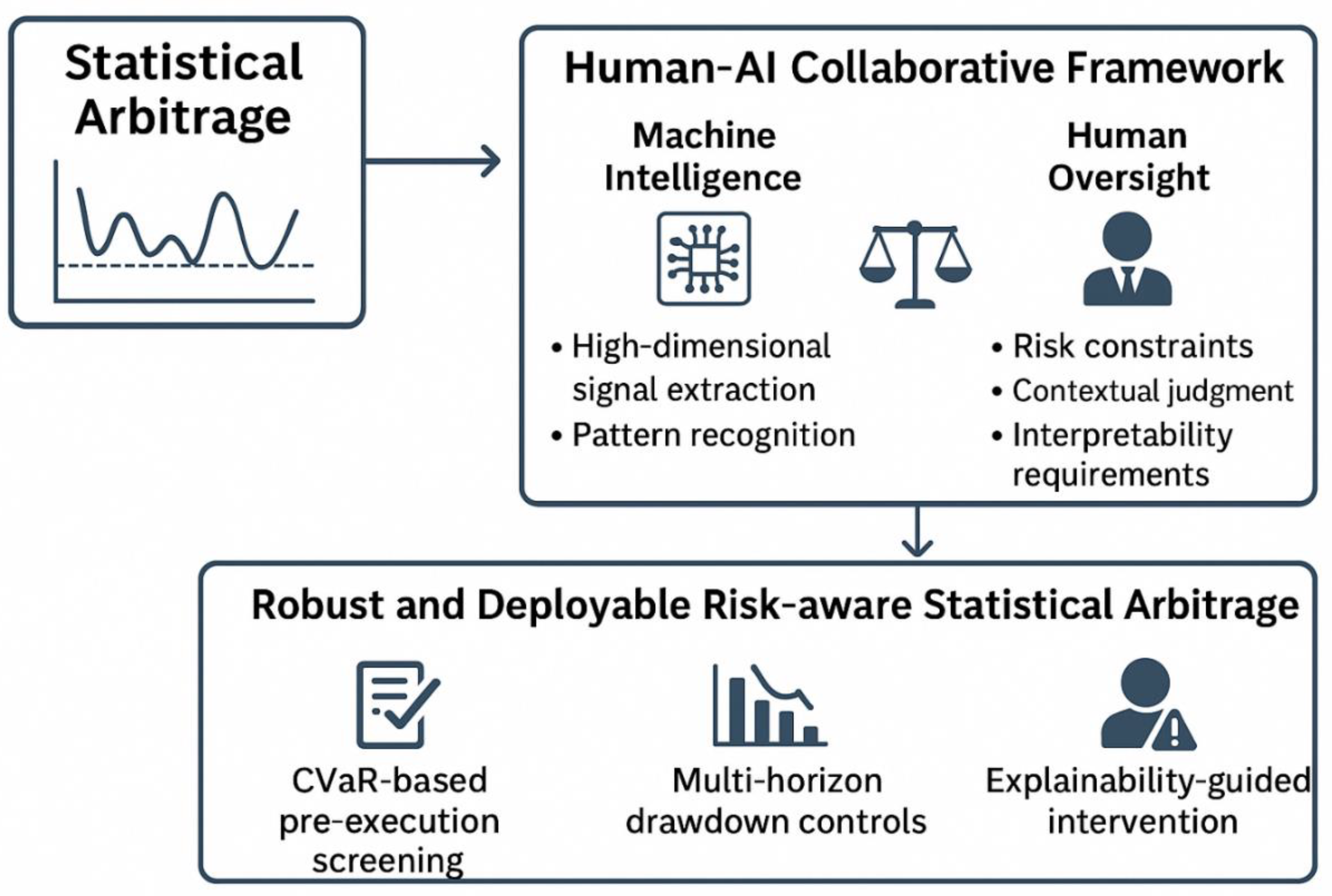

In the proposed framework, CVaR is used both as a performance metric and as an operational constraint: trading signals that imply a projected portfolio CVaR above institutional limits are suppressed or flagged for manual approval. Embedding CVaR in optimization or as a hard constraint reduces tail exposure at execution.

For any machine-learning-based statistical arbitrage implementation, we recommend a minimum set of robustness checks to mitigate overfitting and selection bias. These include: (a) nested cross-validation for hyperparameter tuning and unbiased performance evaluation; (b) rolling-window re-estimation (e.g., a three-year window with a monthly step) to assess stability across different market regimes; (c) block bootstrap procedures (for example, 20-day blocks with at least 1,000 resamples) to construct confidence intervals under serial dependence; (d) Deflated Sharpe Ratio adjustments to correct for multiple testing and potential non-Gaussian return distributions; and (e) explanability and feature-sanity checks (such as SHAP or permutation importance), whereby signals are considered reliable only when their primary drivers have plausible economic interpretations.

Together, these procedures provide a structured approach for improving the reliability and practical credibility of machine learning-based trading strategies.

2.3.6. Deepening Multivariate Dependencies

In the preceding steps, we identified relationships among assets and completed optimization. In this step, we will further refine the characterization of the nonlinear, dynamic, and networked complex relationships among multiple assets. This enables us to depict the interconnections between assets more realistically, thereby enhancing the accuracy of our strategies. We will analyze this process in two distinct parts: classical dynamic dependencies and modern network dependencies.

Classic Dynamic Dependencies: In classic dynamic dependencies, we commonly employ the two-step DCC-GARCH method (R. Engle, 2002) to obtain real-time correlation coefficients between assets. The process primarily consists of these two steps:

Firstly, for each asset, analyze its own volatility using a GARCH model. Through this step, we can isolate the pure shock signal (i.e., standardized residual) for each asset—that is, remove the influence of the asset’s own volatility to extract the external shocks it experiences. Finally, aggregate all these “standardized residuals” into a single vector.

Secondly, constructing a pseudo-variance matrix by integrating “long-term average covariance,” “residual impact from the previous period,” and “the pseudo-variance matrix from the previous period.” Set two parameters to control the weighting of new information versus historical data, enabling the matrix to dynamically adjust over time. Subsequently, standardize this pseudo-variance matrix to obtain a dynamic correlation coefficient matrix. Each element within this matrix represents the correlation coefficient between the corresponding two assets at the current time step.

Modern Network Dependencies: When modeling the nonlinear, asymmetric, and network-based dependencies between assets that are influenced by other assets, we often employ the Pair-Copula method. Through Pair-Copula decomposition, we ultimately derive a joint distribution model for multiple assets—that is, a complete mathematical model capturing the collective fluctuations of all assets. Simultaneously, we can uncover specific dependency details—such as identifying core nodes and determining which assets influence the correlation between any two assets. This yields a clear, traceable network. Therefore, we can precisely calculate extreme risk probabilities better, quantify conditional correlation impacts and optimize the complex portfolios to achieve more effective and more profitable investment outcomes.

2.3.7. Summary of This Era

The era of classical econometric models for statistical arbitrage provided systematic tools for identifying arbitrage opportunities through its rich and rigorous modeling techniques. However, constrained by its ability to capture nonlinear complex relationships, many aspects have gradually been replaced by faster and more efficient machine learning methods. But we can never ignore the approaches from this period. They lay the foundation for the long-term development of statistical arbitrage and offer abundant insights for future generations, which proves to be really useful in future research.

2.4. The Extension in the Era of AI

In the past two decades, the breakthrough development of artificial intelligence technology has profoundly changed the operating logic of the financial market. Driven by the double exponential growth of computing power and the breakthrough of machine learning algorithms, the statistical arbitrage strategy has completed the leapfrog transformation from a traditional measurement model to an intelligent system. Early statistical arbitrage relies on artificially defined variables and linear hypothetical frameworks, just like measuring winding rivers with a straight ruler, it is difficult to capture nonlinear fluctuations in the market; while AI technology realizes the autonomous mining of multi-dimensional data integration and nonlinear relationships through neural networks and deep learning architecture, so that arbitrage strategies can break through traditional boundaries.

The current AI-driven statistical arbitrage system shows three core advantages: first, when processing high-dimensional financial data, AI models show pattern recognition capabilities far beyond traditional linear methods. Through algorithms such as neural networks, gradient boosting trees and random forests, the system can automatically capture nonlinear interactions and potential structures between variables, so as to find arbitrage signals with predictive value in massive asset data. Krauss, Do and Huck (2017) compared the performance of deep neural networks, gradient boosting trees and random forests in statistical arbitrage with S&P 500 stocks as a sample. The results show that the deep learning model is significantly better than the traditional strategy in terms of revenue forecasting accuracy and economic performance. This discovery proves the effectiveness of AI in complex market signal recognition and provides a new technical path for the signal construction of statistical arbitrage.

Secondly, in statistical arbitrage, the dynamism and timing characteristics of signals are particularly critical. Traditional methods usually assume the linear regression or static mean regression relationship between returns and spreads, while deep learning models based on structures such as long- and short-term memory networks (LSTM) and Transformer can better capture the nonlinear dynamics and delay effects of time series. The revolutionary aspect of LSTM lies in its Memory Cell and three core Gates—Forget Gate, Input Gate, and Output Gate. These Gates work collaboratively to achieve the “filtering, updating, and outputting” of historical information, ultimately capturing nonlinear dependencies. The main functions of the three Gates are as follows:

Forget Gate: Deciding which historical information to discard, sifting through history like organizing a drawer.

First screening new information (Input Gate decision):

Then generate candidate information (candidate memory cell):

At last update Memory Cell (Core Step):

Output Gate: Determines which information to output to the next frame.

Filter output information:

Generate the current hidden state:

Flori and Regoli (2021) found that after embedding the LSTM model into the paired trading framework, the profitability and stability of the strategy are significantly improved, especially under the condition of controlling transaction costs and risk exposure. This study verifies the advantages of the deep sequence network in predicting the dynamics of asset spreads and optimizing the timing of entry and exit, and provides important methodological support for the construction of a dynamic statistical arbitrage system. It directly shows that relying on artificial intelligence to capture nonlinear complex relationships has a significant effect on improving the profitability of statistical arbitrage models.

Moreover, with the expansion of the scale and dimension of financial market data, the parallel computing power of AI algorithms enables statistical arbitrage to expand from single asset pairing to multi-asset and even cross-market combination strategies. Huck (2019) shows the feasibility of applying machine learning models to large-scale data sets for arbitrage signal screening and combination optimization. The study pointed out that the use of machine learning algorithms for feature screening and nonlinear mapping not only improves the scalability of strategies, but also significantly enhances the ability to identify arbitrage opportunities in high-dimensional space. This means that the AI-driven statistical arbitrage system can maintain robustness under large sample conditions, laying the foundation for institutional investors to achieve systematic and large-scale deployment.

Although AI has improved the intelligence of strategy generation, its strong fitting ability also brings a serious risk of backtesting overfitting and selective bias. AI models often perform large-scale parameter search and feature optimization in historical data. This kind of “data mining” training is very likely to lead to a significant attenuation of strategies out-of-sample. The “Deflated Sharpe Ratio” proposed by Bailey and López de Prado (2014) provides a correction framework for quantitative strategy performance evaluation to correct the exaggerated returns caused by multiple tests and non-normal yield distribution. They pointed out that without statistical correction of the overfitting, the model may be completely invalid in actual investment. This challenge is particularly critical to AI-driven statistical arbitrage, because the higher the complexity of the model, the greater the risk of overfitting. Therefore, future research needs to introduce stricter cross-verification mechanisms, rolling sample testing and robustness testing in the model training stage to ensure the mobility and stability of strategies in the real market. Below, we are going to talk about the most commonly used four machine learning methods, analyzing how machine learning contribute to the development of statistical arbitrage.

2.4.1. Supervised Learning and Unsupervised Learning

Supervised learning employs labeled datasets to train models, enabling them to learn the mapping relationship between inputs and outputs (Krauss et al., 2017). In the research and practice of statistical arbitrage, the core value of supervised learning is reflected in capturing complex nonlinear patterns, thus improving the accuracy of arbitrage signals. Supervised learning model such as random forest and deep neural networks, can not only effectively make up for the limitations of traditional simple linear models, but also identify more complex price dynamic characteristics. By improving the ability to identify nonlinear price movements, this kind of machine learning method enhances the accuracy of the signals and reduces the noise interference significantly, which makes the strategy much more robust. Moreover, supervised learning methods can also maintain good generalization capabilities in the continuous updated data flow. Different from supervised learning, unsupervised learning almost doesn’t rely on pre-existing labeled information. Instead, it could uncover latent structures and relationships without external guidance on its own (Han et al., 2023). When constructing a multi-asset arbitrage strategy, unsupervised learning is proved to be effective in uncovering hidden interdependencies across large scopes of assets. It provides basic evidence of correlations which do support the statistical arbitrage. In fact, this machine learning method helps us save a lot of human resources. With the supplementary methods provided by this, the process of constructing a strategy will be even more accurate.

2.4.2. Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning primarily operates through constructing an “environment-agent-reward” interaction framework, which enables agents to continuously optimize decision strategies through ongoing interaction with dynamic environments (Coache et al., 2023; Jaimungal et al., 2022). In machine learning-based statistical arbitrage, reinforcement learning enables real-time position adjustments and adaptive optimization of profit-taking and stop-loss thresholds. It allows strategies to better adapt to market fluctuations and will undoubtedly perform a more stable investment.

2.4.3. Deep Learning

In the artificial intelligence-driven statistical arbitrage system, deep learning models (especially LSTM) are widely used to predict spread changes and potential mean return opportunities between assets. Unlike traditional linear regression, LSTM can capture nonlinear dynamic relationships in the time dimension. Its core idea is to retain or forget historical information through the gate structure, thus forming a nonlinear mapping of future price trends. A simplified prediction function can represent:

In the function,

is the input feature (such as spread, yield, turnover),

and b are model parameters, and

is the nonlinear activation function (commonly used as sigmoid or tanh). The function learns the mapping relationship through the training sample, so that the output

is used as a prediction of the direction or magnitude of the next spread. The training target of the model is usually in the form of minimized mean square error (MSE):

Among them, is the real observed value. By continuously optimizing , the model learns potential arbitrage signals in historical data and uses them for strategy execution on off-sample data.

Fischer and Krauss (2018) verified the effectiveness of this method in the empirical study of the European Journal of Operational Research. They found that the statistical arbitrage strategy built by LSTM’s directional prediction of S&P 500 stocks has significantly higher risk-adjusted returns than traditional methods, which shows that deep learning has outstanding application value in capturing nonlinear market structure and timing dependencies.

2.4.4. Summary of the Extension in This Era

We can briefly conclude the development of this era with three “from” and three “to”, that is from linear to nonlinear approaches, from rule-driven to data-driven methodologies and from single-asset analysis to multi-market coordination. If looking ahead, the future trajectory of statistical arbitrage may focus on three key areas: leveraging multimodal data fusion to transcend the limitations of traditional financial data dimensions, establishing cross-market coordination mechanisms, and most critically, enhancing the interpretability of AI-driven statistical arbitrage to meet regulatory requirements. Advancements in these domains will empower future statistical arbitrage strategies with heightened profitability and market compliance, making it more competitive in financial market.