Submitted:

13 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

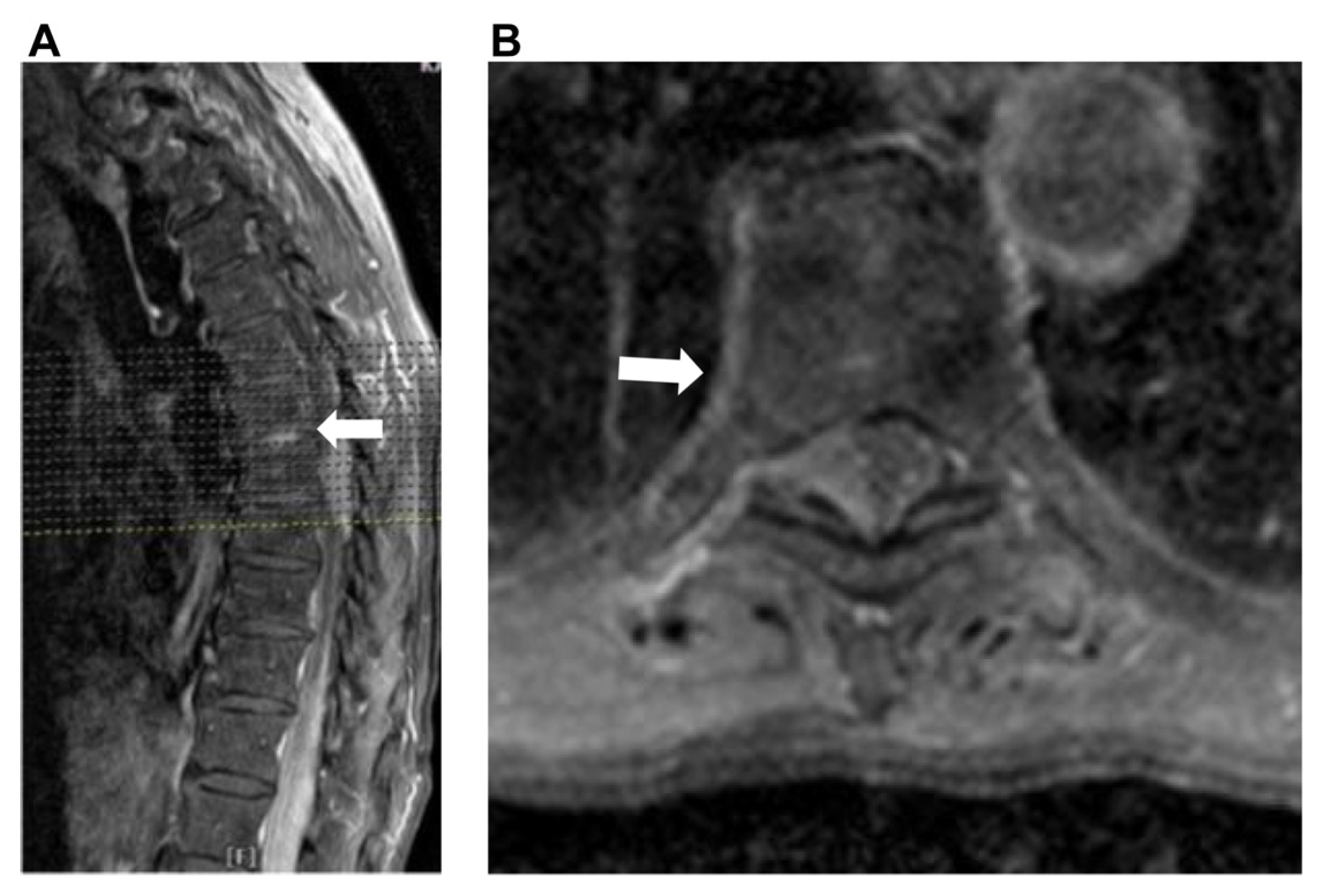

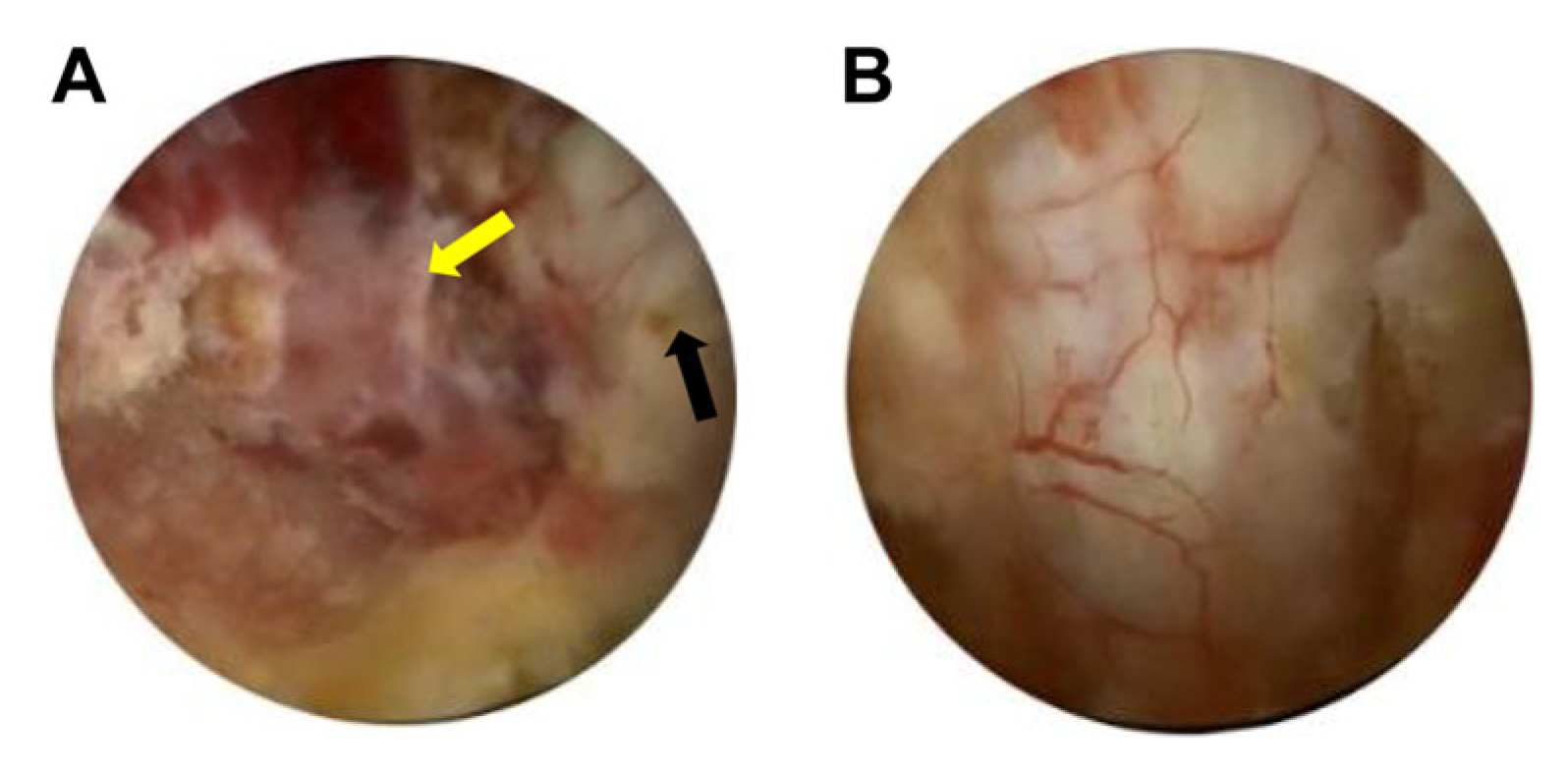

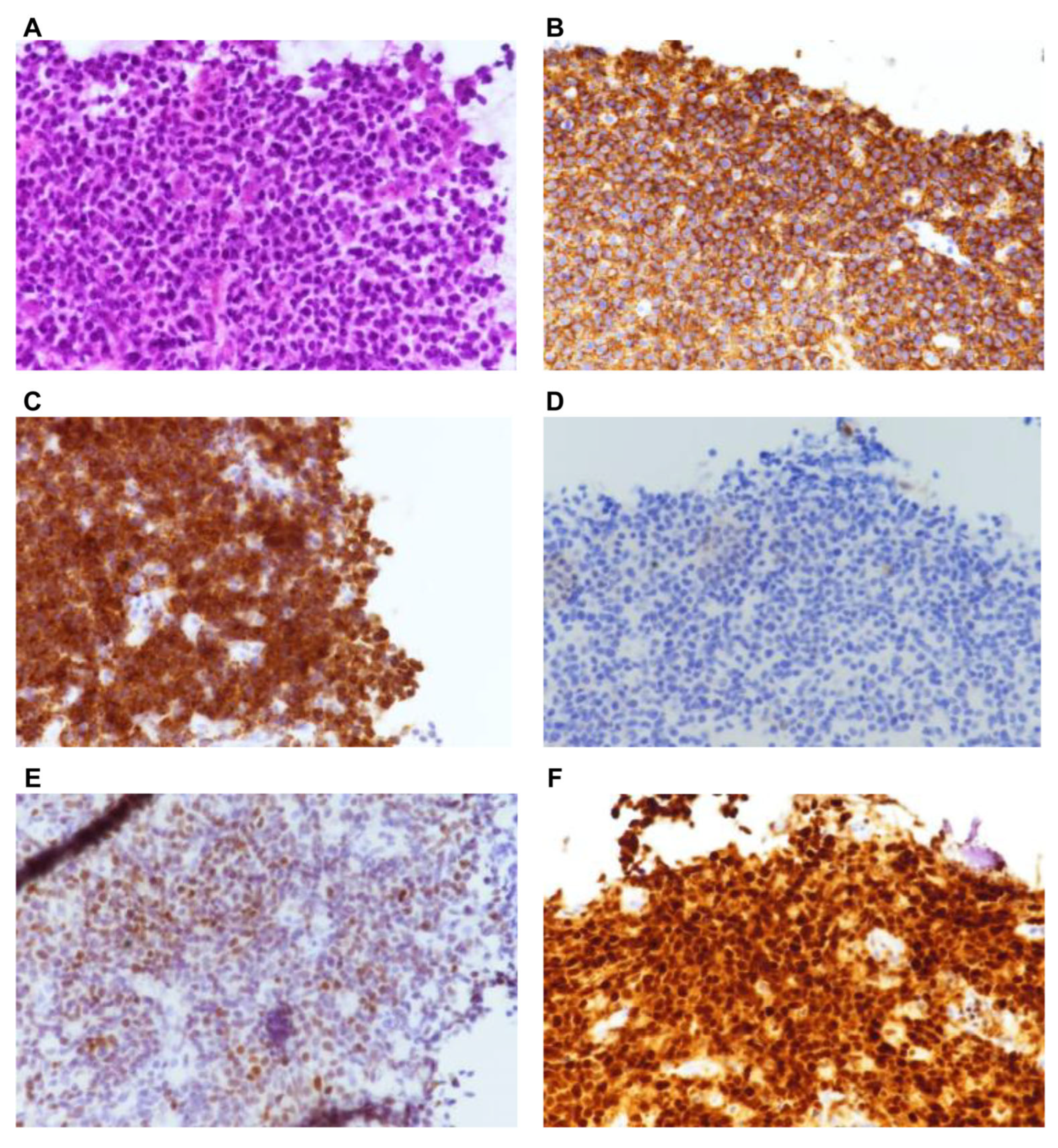

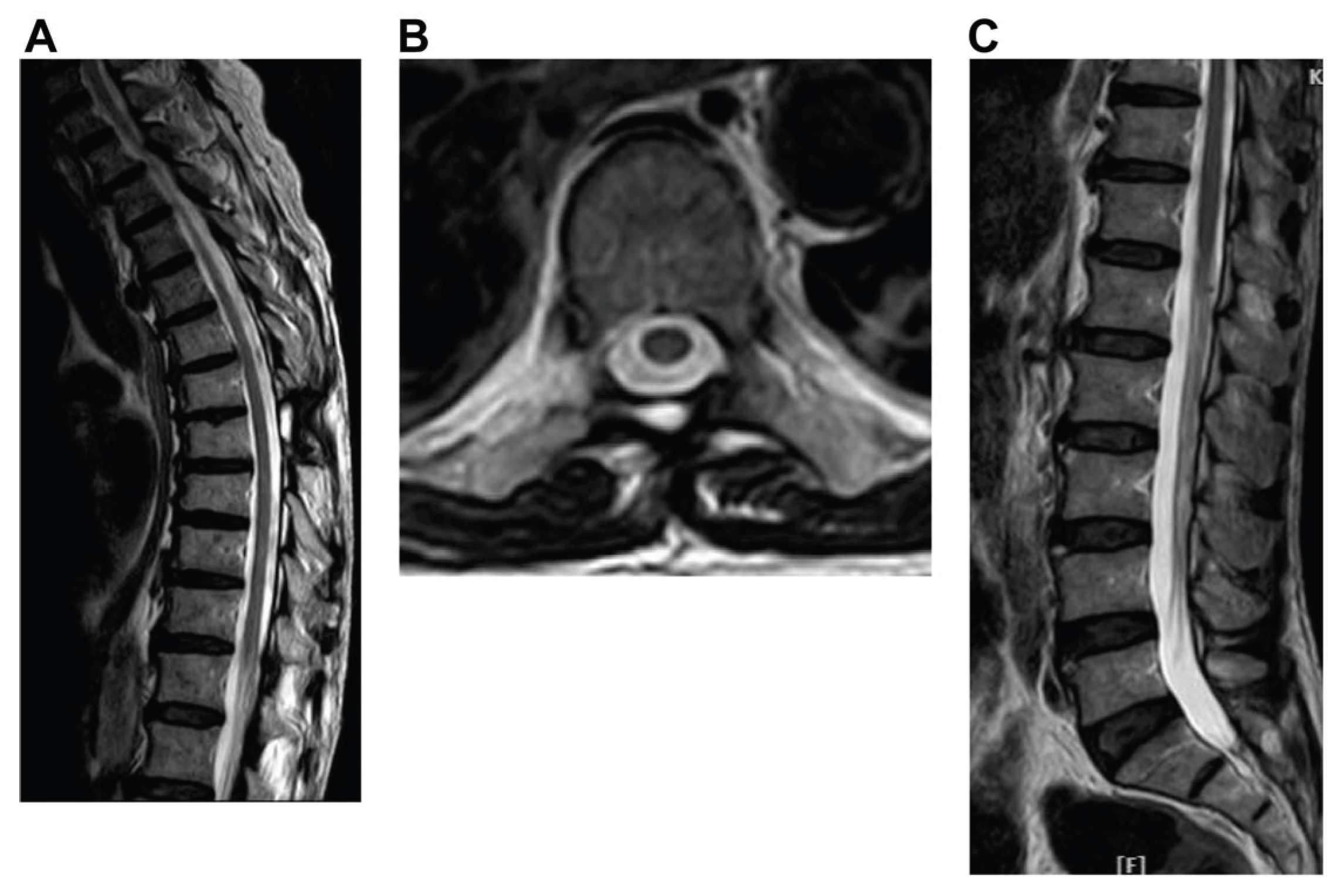

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCNSL | Primary central nervous system lymphoma |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DLBCL | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| PDLBCL | Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| NL | Neurolymphomatosis |

| PCEL | Primary cauda equina lymphoma |

| UBE | Uniportal biportal endoscopic |

| R-CHOP | Chemotherapy regimen (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) |

References

- Li, S.; Young, K.H.; Medeiros, L.J. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Pathology 2018, 50, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, F.; Shoumal, N.; Obeid, B.; Alkhoder, A. Primary Diffuse Large B-Cell Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma of the Thoracic Spine Presented Initially as an Epigastric Pain. Asian J Neurosurg 2020, 15, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Gu, W.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, X. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett 2016, 11, 3085–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, E.R.; Batchelor, T.T. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Arch Neurol 2010, 67, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoa Pinheiro, J.; Rato, J.; Rebelo, O.; Costa, G. Primary spinal epidural lymphoma: a rare entity with an ambiguous management. BMJ Case Rep 2020, 13, e233442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, N.; Kohara, M.; Ikeda, J.; Hori, Y.; Fujita, S.; Okada, M.; Ogawa, H.; Sugiyama, H.; Fukuhara, S.; Kanamaru, A.; Hino, M.; Kanakura, Y.; Morii, E.; Aozasa, K. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the spinal epidural space: A study of the Osaka Lymphoma Study Group. Pathol Res Pract 2010, 206, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, F.H.; Miller, D.C. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurosurg 1988, 68, 835–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, H.; Imagama, S.; Ito, Z.; Ando, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Ukai, J.; Muramoto, A.; Shinjyo, R.; Matsumoto, T.; Yamauchi, I.; Satou, A.; Ishiguro, N. Primary cauda equina lymphoma: case report and literature review. Nagoya J Med Sci 2014, 76, 349–354. [Google Scholar]

- Broen, M.; Draak, T.; Riedl, R.G.; Weber, W.E. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the cauda equina. BMJ Case Rep 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, C.P.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Greiner, T.C.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Delabie, J.; Ott, G.; Müller-Hermelink, H.K.; Campo, E.; Braziel, R.M.; Jaffe, E.S.; Pan, Z.; Farinha, P.; Smith, L.M.; Falini, B.; Banham, A.H.; Rosenwald, A.; Staudt, L.M.; Connors, J.M.; Armitage, J.O.; Chan, W.C. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004, 103, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, J.S.; Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Kruchko, C.; DeAngelis, L.M.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Grommes, C. The elderly left behind-changes in survival trends of primary central nervous system lymphoma over the past 4 decades. Neuro Oncol 2018, 20, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckert, P.W.; Kluin, P.M.; Ferry, J.A. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the CNS. In WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, 4th ed.; Louis, D.N., Wiestler, O.D., Cavenee, W.K., Eds.; IARC Press: Lyon, 2016; pp. 272–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lauw, M.I.S.; Lucas, C.G.; Ohgami, R.S.; Wen, K.W. Primary central nervous system lymphomas: a diagnostic overview of key histomorphologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic features. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Liao, L.M.; Ding, J.W.; Zhang, Z.L.; Liu, A.W.; Huang, L. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic factors for primary spinal epidural lymphoma: report on 36 Chinese patients and review of the literature. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisariu, S.; Avni, B.; Batchelor, T.T.; van den Bent, M.J.; Bokstein, F.; Schiff, D.; Kuittinen, O.; Chamberlain, M.C.; Roth, P.; Nemets, A.; Shalom, E.; Ben-Yehuda, D.; Siegal, T. Neurolymphomatosis: an International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group report. Blood 2010, 115, 5005–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, P.; Pitham, T.; Owler, B. Isolated neurolymphomatosis of the cauda equina and filum terminale: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008, 33, E807–E811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baehring, J.M.; Batchelor, T.T. Diagnosis and management of neurolymphomatosis. Cancer J 2012, 18, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baehring, J.M.; Damek, D.; Martin, E.C.; Betensky, R.A.; Hochberg, F.H. Neurolymphomatosis. Neuro Oncol 2003, 5, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarde, S.; Tabouret, E.; Matta, M.; Franques, J.; Attarian, S.; Pouget, J.; Maues De Paula, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Dory-Lautrec, P.; Chinot, O.; Barrié, M. Primary neurolymphomatosis diagnosis and treatment: a retrospective study. J Neurol Sci 2014, 342, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Yasuda, T.; Hiraiwa, T.; Kanamori, M.; Kimura, T.; Kawaguchi, Y. Primary cauda equina lymphoma diagnosed by nerve biopsy: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett 2018, 16, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlman, J.J.; Alhaj Moustafa, M.; Gupta, V.; Jiang, L.; Tun, H.W. Primary cauda equina lymphoma treated with CNS-centric approach: a case report and literature review. J Blood Med 2021, 12, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Dyck, P.J. Hypertrophy of the nerve roots of the cauda equina as a paraneoplastic manifestation of lymphoma. Arch Neurol 2005, 62, 1776–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreri, A.J.M.; Calimeri, T.; Cwynarski, K.; Dietrich, J.; Grommes, C.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Hu, L.S.; Illerhaus, G.; Nayak, L.; Ponzoni, M.; Batchelor, T.T. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Fan, B.; Sun, Q.; Chen, J.; Song, X.; Yin, W. Comparison of the effect of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy on the survival of patients with primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the spine: A SEER-Based Study. World Neurosurg 2023, 175, e940–e949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milgrom, S.A.; Pinnix, C.C.; Chi, T.L.; Vu, T.H.; Gunther, J.R.; Sheu, T.; Fowler, N.; Westin, J.R.; Nastoupil, L.J.; Oki, Y.; Fayad, L.E.; Neelapu, S.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Hagemeister, F.B.; Fanale, M.A.; Lee, H.J.; Hosing, C.; Ahmed, S.; Nieto, Y.; Shpall, E.J.; Dabaja, B.S. Radiation therapy as an effective salvage strategy for secondary CNS lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018, 100, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mally, R.; Sharma, M.; Khan, S.; Velho, V. Primary lumbo-sacral spinal epidural non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a case report and review of literature. Asian Spine J 2011, 5, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnard, V.; Sun, A.; Epelbaum, R.; Poortmans, P.; Miller, R.C.; Verschueren, T.; Scandolaro, L.; Villa, S.B.; Majno, S.O.; Ozsahin, M.; Mirimanoff, R.O. Primary spinal epidural lymphoma: patients' profile, outcome, and prognostic factors: a multicenter Rare Cancer Network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006, 65, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Cho, D.C.; Sung, J.K.; Kim, K.T. Primary malignant lymphoma in a spinal cord presenting as an epidural mass with myelopathy: a case report. Korean J Spine 2012, 9, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, T.; Ohno, T.; Tsuji, K.; Kita, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Deguchi, K.; Shirakawa, S. Primary epidural non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in clinical stage IEA presenting with paraplegia and showing complete recovery after combination therapy. Intern Med 1992, 31, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, P.; Thaell, J.F.; Kiely, J.M.; Harrison, E.G.; Miller, R.H. Lymphoma of the spinal extradural space. Cancer 1976, 38, 1862–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sita-Lumsden, A.; Harris, P.; Bower, M. Lymphoma in the immunocompromised. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2010, 71, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieblemont, C.; Coiffier, B. Lymphoma in older patients. J Clin Oncol 2007, 25, 1916–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Antoni, D.J.; Claro, M.L.; Poehling, G.G.; Hughes, S.S. Translaminar lumbar epidural endoscopy: anatomy, technique, and indications. Arthroscopy 1996, 12, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.X.; Huang, P.; Kotheeranurak, V.; Park, C.W.; Heo, D.H.; Park, C.K.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.S. A systematic review of unilateral biportal endoscopic spinal surgery: preliminary clinical results and complications. World Neurosurg 2019, 125, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, D.H.; Quillo-Olvera, J.; Park, C.K. Can percutaneous biportal endoscopic surgery achieve enough canal decompression for degenerative lumbar stenosis? Prospective case-control study. World Neurosurg 2018, 120, e684–e689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.S.; Heo, D.H.; Kim, H.B.; Chung, H.T. Biportal endoscopic technique for transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: review of current research. Int J Spine Surg 2021, 15, S84–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, D.H.; Son, S.K.; Eum, J.H.; Park, C.K. Fully endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion using a percutaneous unilateral biportal endoscopic technique: technical note and preliminary clinical results. Neurosurg Focus 2017, 43, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Jun, S.G.; Jung, J.T.; Lee, S.J. Posterior percutaneous endoscopic cervical foraminotomy and diskectomy with unilateral biportal endoscopy. Orthopedics 2017, 40, e779–e783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Heo, D.H.; Lee, D.C.; Chung, H.T. Biportal endoscopic unilateral laminotomy with bilateral decompression for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2021, 163, 2537–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Gong, Z.; Qiu, X.; Zhong, Z.; Ping, Z.; Hu, Q. Cave-in" decompression under unilateral biportal endoscopy in a patient with upper thoracic ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament: Case report. Front Surg 2022, 9, 1030999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Ha, J.S.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, C.K.; Hong, H.J.; Choi, S.Y.; Park, C.K. Biportal endoscopic posterior thoracic laminectomy for thoracic spondylotic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum: technical developments and outcomes. Neurospine 2023, 20, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Bendardaf, R.; Ali, M.; Kim, H.A.; Heo, E.J.; Lee, S.C. Unilateral biportal endoscopic tumor removal and percutaneous stabilization for extradural tumors: technical case report and literature review. Front Surg 2022, 9, 863931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Cui, W.; Chen, W.; Chu, R.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, S. Unilateral biportal endoscopy for the resection of thoracic intradural extramedullary tumors: technique case report and literature review. Int Med Case Rep J 2024, 17, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).