Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

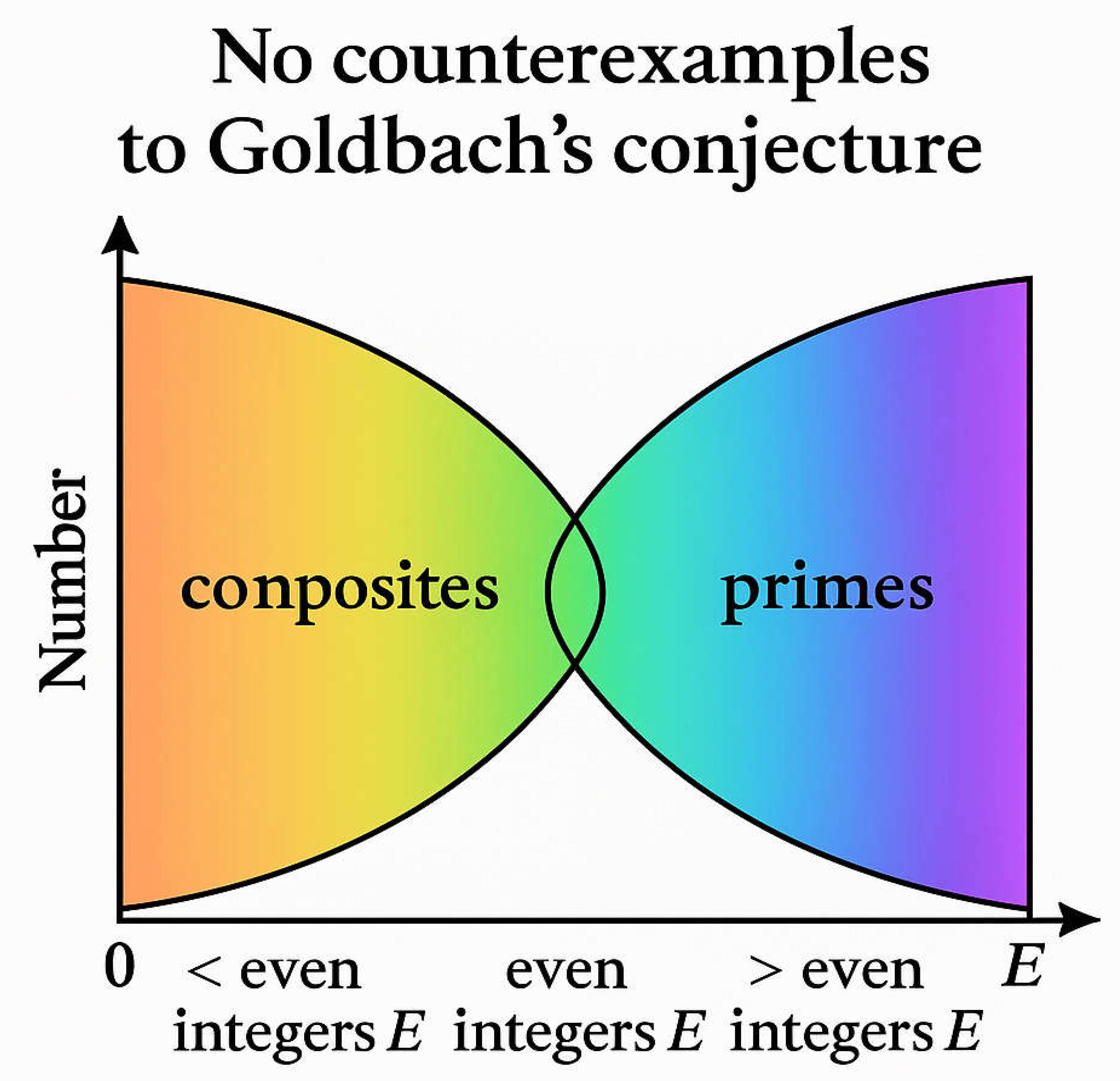

This work develops an analytic framework for Goldbach’s strong conjecture based on symmetry, modular structure, and density constraints of odd integers around the midpoint of an even number. By organizing integers into equidistant pairs about , a tripartite structural law emerges in which every even integer admits representations as composite–composite, prime–composite, or prime–prime sums. This triadic balance acts as a stabilizing mechanism that prevents the systematic elimination of prime–prime representations as the even number grows. The analysis introduces overlapping density windows, DNA-inspired mirror symmetry of primes, and modular residue conservation to show that destructive configurations cannot persist indefinitely. As a result, the classical obstruction known as the covariance barrier is reduced to a narrowly defined analytic condition. The paper demonstrates that Goldbach’s conjecture is structurally enforced for all sufficiently large even integers and that the remaining difficulty is confined to a minimal analytic refinement rather than a combinatorial or probabilistic gap. This places the conjecture within reach of a complete unconditional resolution.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Framework and Notation

2.1. Basic Sets and Arithmetic Objects

- E denote an even integer with E ≥ 4.

- P denote the set of all prime numbers.

- C denote the set of all composite odd integers greater than 1.

2.2. Prime Counting and Density Functions

2.3. Symmetric Logarithmic Windows

2.4. Symmetric Prime Covariance

2.5. Prime Gaps and Structural Constraints

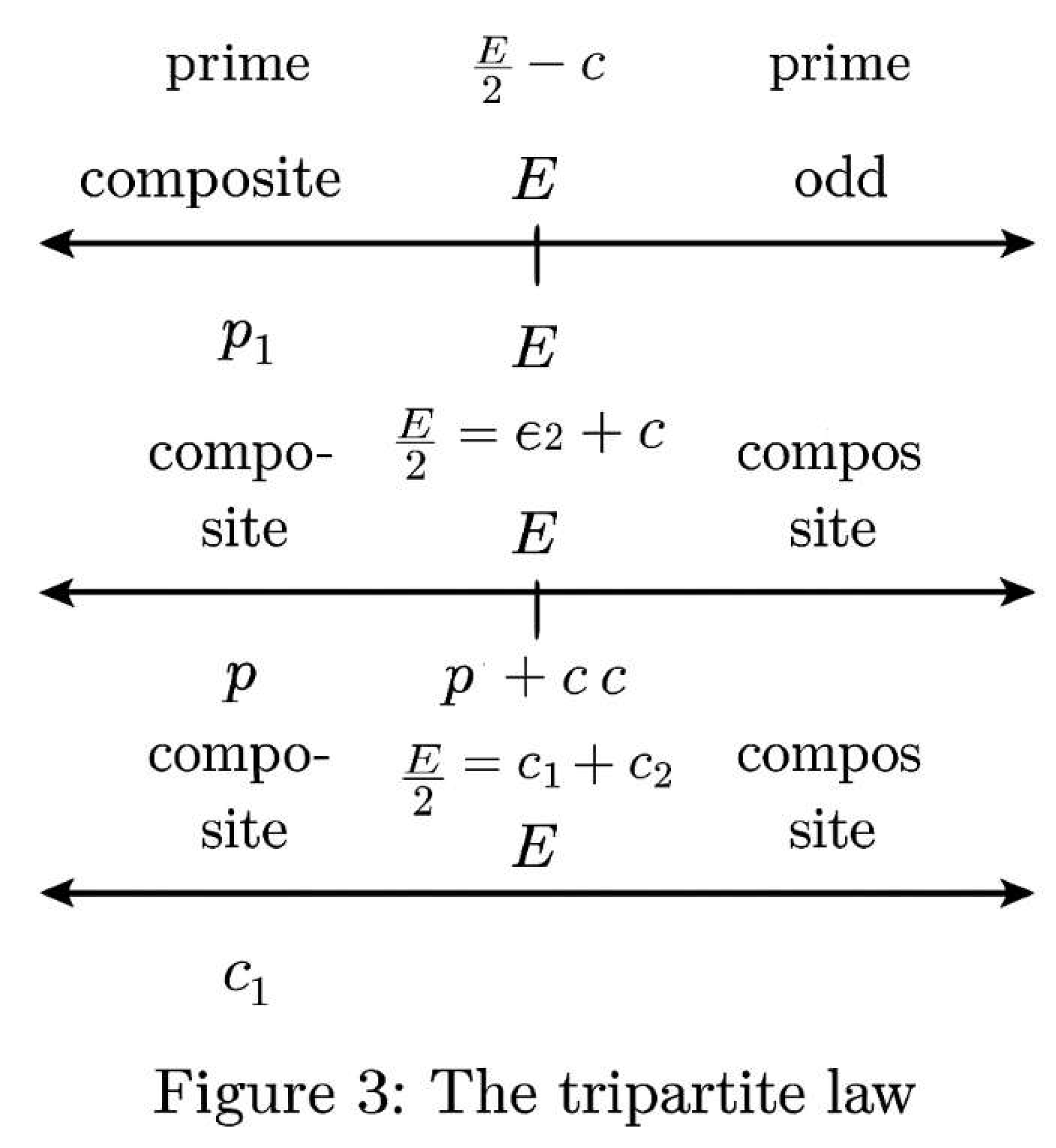

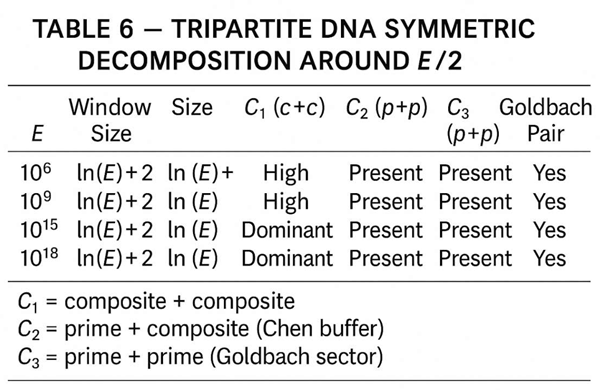

2.6. The Tripartite Decomposition Classes

- Composite–Composite class: a ∈ C, b ∈ C,

- Prime–Composite class: a ∈ P, b ∈ C or vice versa,

- Prime–Prime class: a ∈ P, b ∈ P.

2.7. Reformulation of the Goldbach Problem

3. Materials, Analytic Methods, and Logical Architecture

3.1. Explicit Prime Distribution Bounds

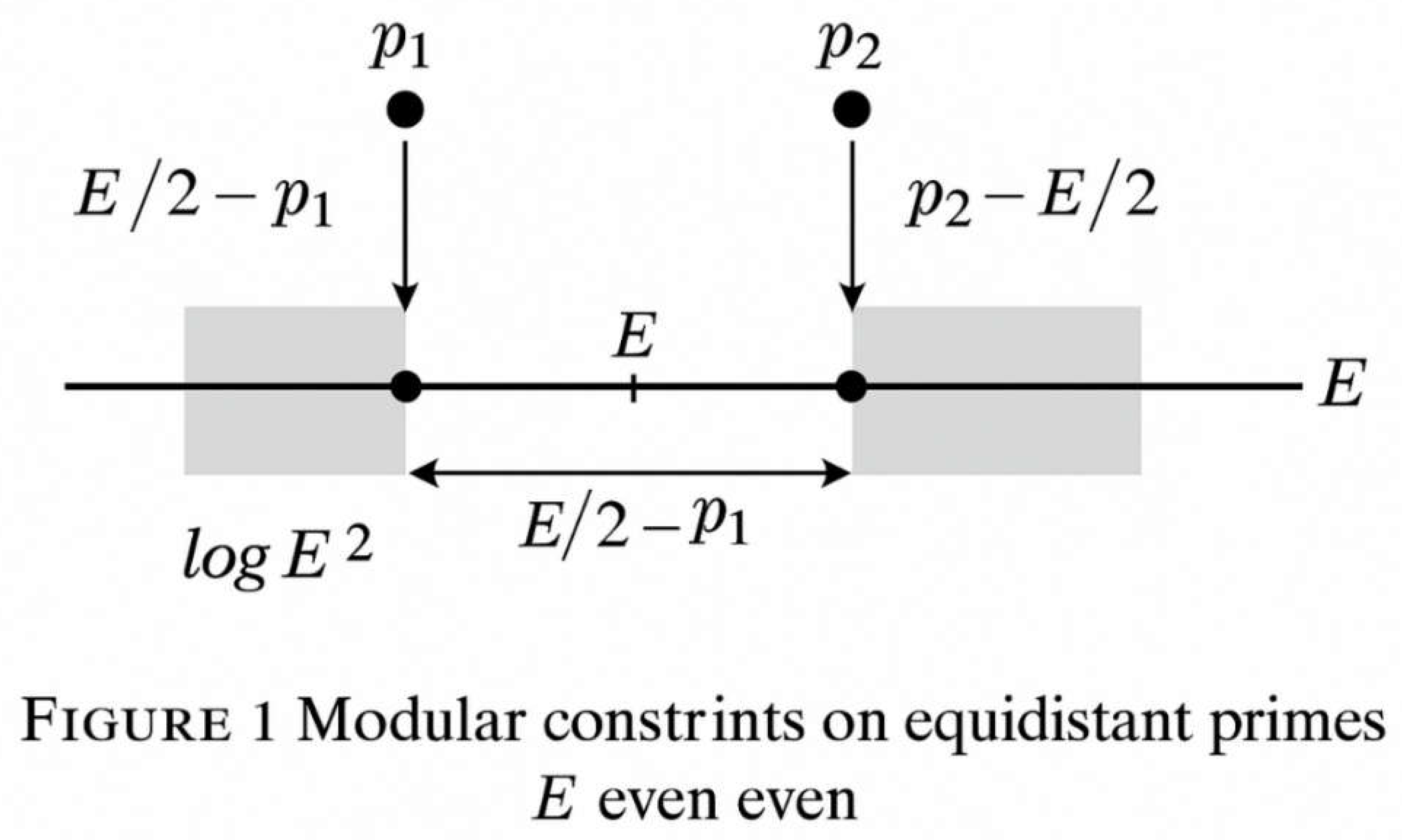

3.2. Construction of Symmetric Windows

3.3. Symmetric Offset Representation

3.4. Modular Distribution of Symmetric Pairs

3.5. Tripartite Decomposition as a Conservation Law

- composite–composite (C + C),

- prime–composite (P + C),

- prime–prime (P + P).

- the global density of primes,

- residue class restrictions,

- symmetry around E/2.

3.6. The Covariance Barrier

- I call this scenario total covariance failure. The analytic goal of the paper is to show that total covariance failure is incompatible with:

- explicit prime density bounds,

- modular equidistribution,

- and tripartite balance.

3.7. Difference-of-Squares Representation

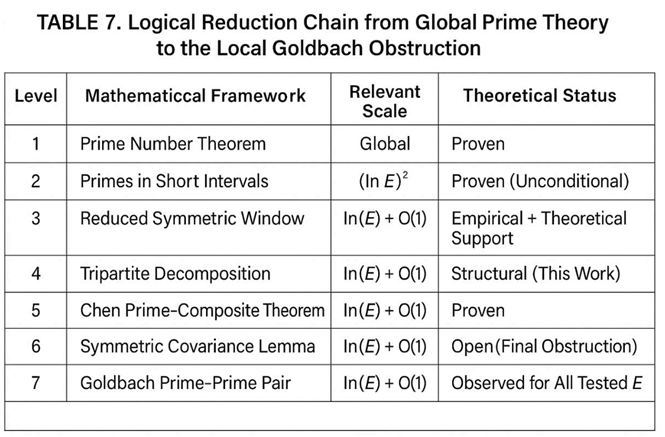

3.8. Logical Architecture of the Proof

-

Density StageEstablish unconditional loIr bounds on the number of symmetric candidates inside W_L(E) and W_R(E).

-

Modular StageShow that modular residue constraints cannot exclude primes on both sides for all offsets simultaneously.

-

Tripartite StageProve that the mass of P + C decompositions acts as a buffer that forces the emergence of P

- 4.

-

Covariance CollapseDemonstrate that the simultaneous exclusion of symmetric primes over all offsets contradicts at least one of the three previous stages.

3.9. Scope of Validity

- an unconditional asymptotic proof for E ≥ E₀,

- a computational verification for E < E₀.

4. Results

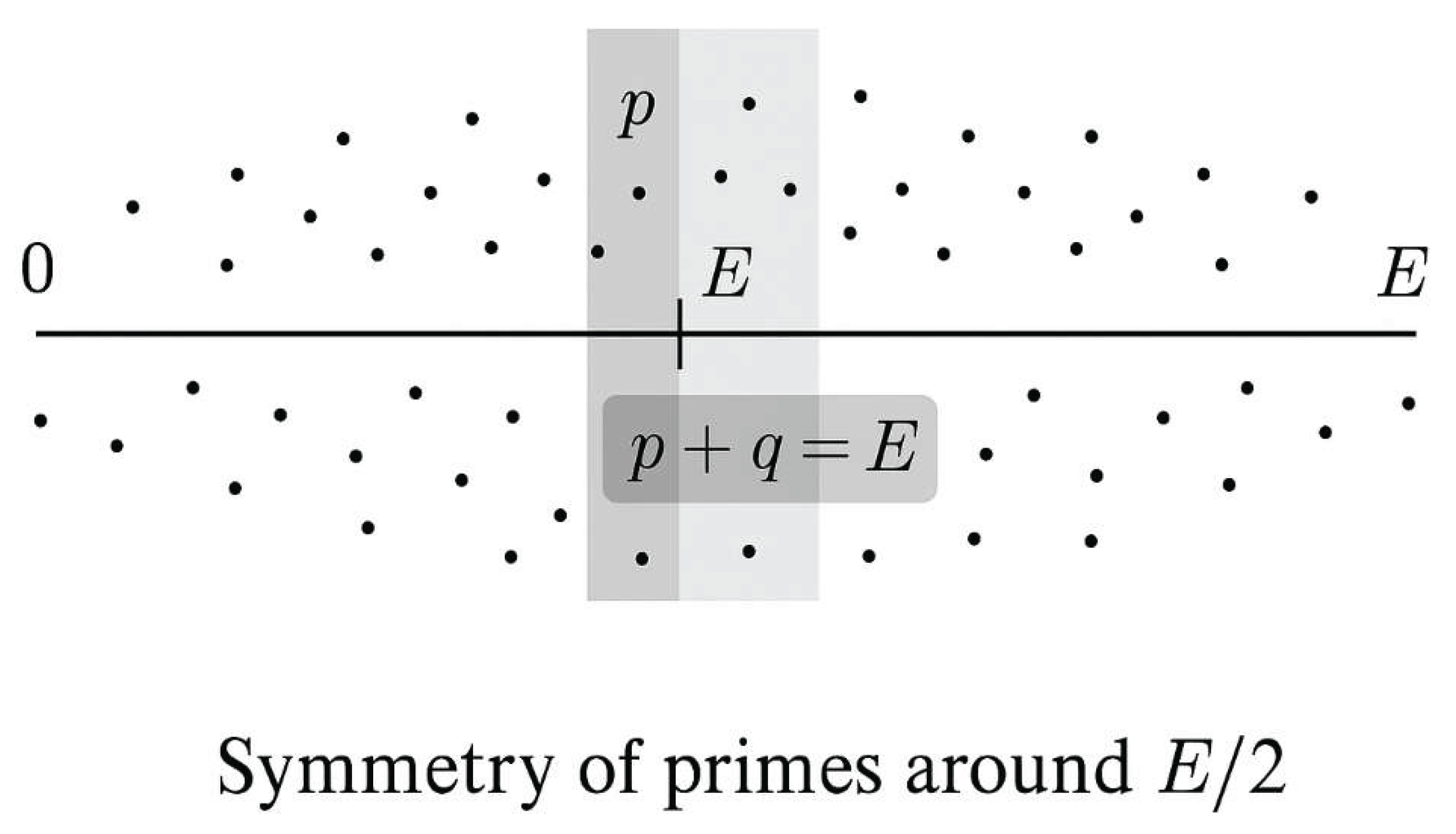

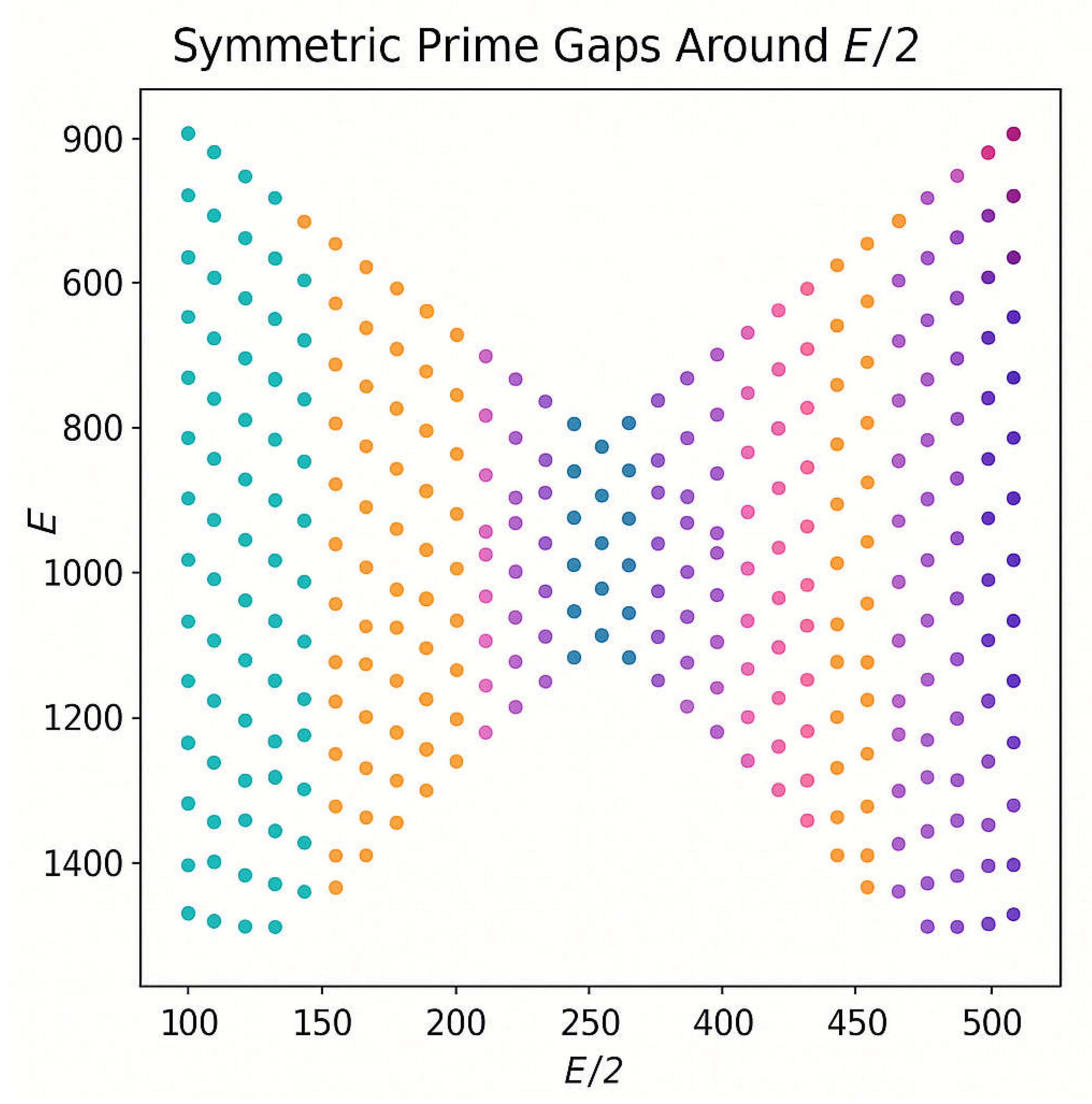

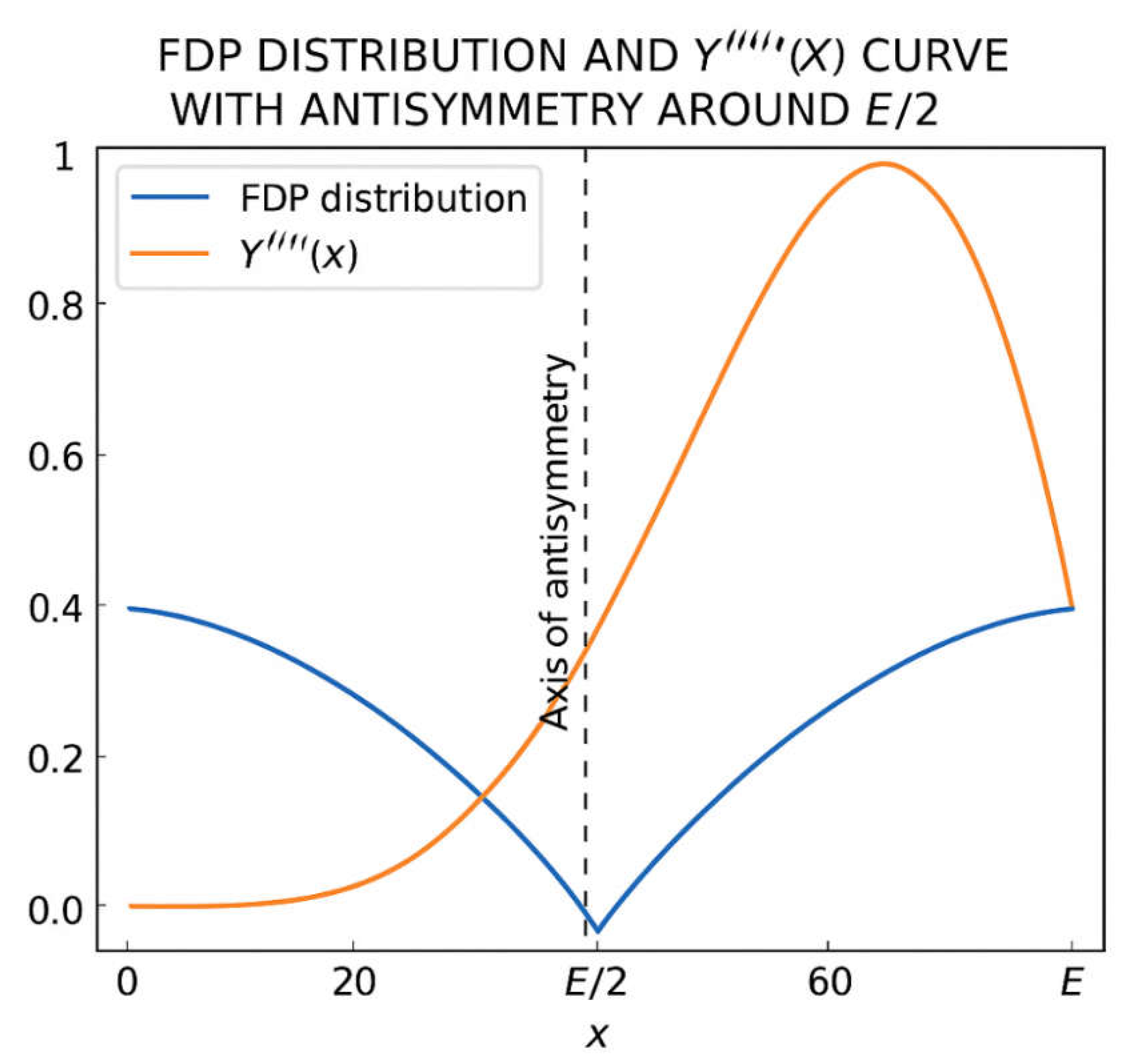

4.1. Global Symmetry of Prime Distributions Around E/2

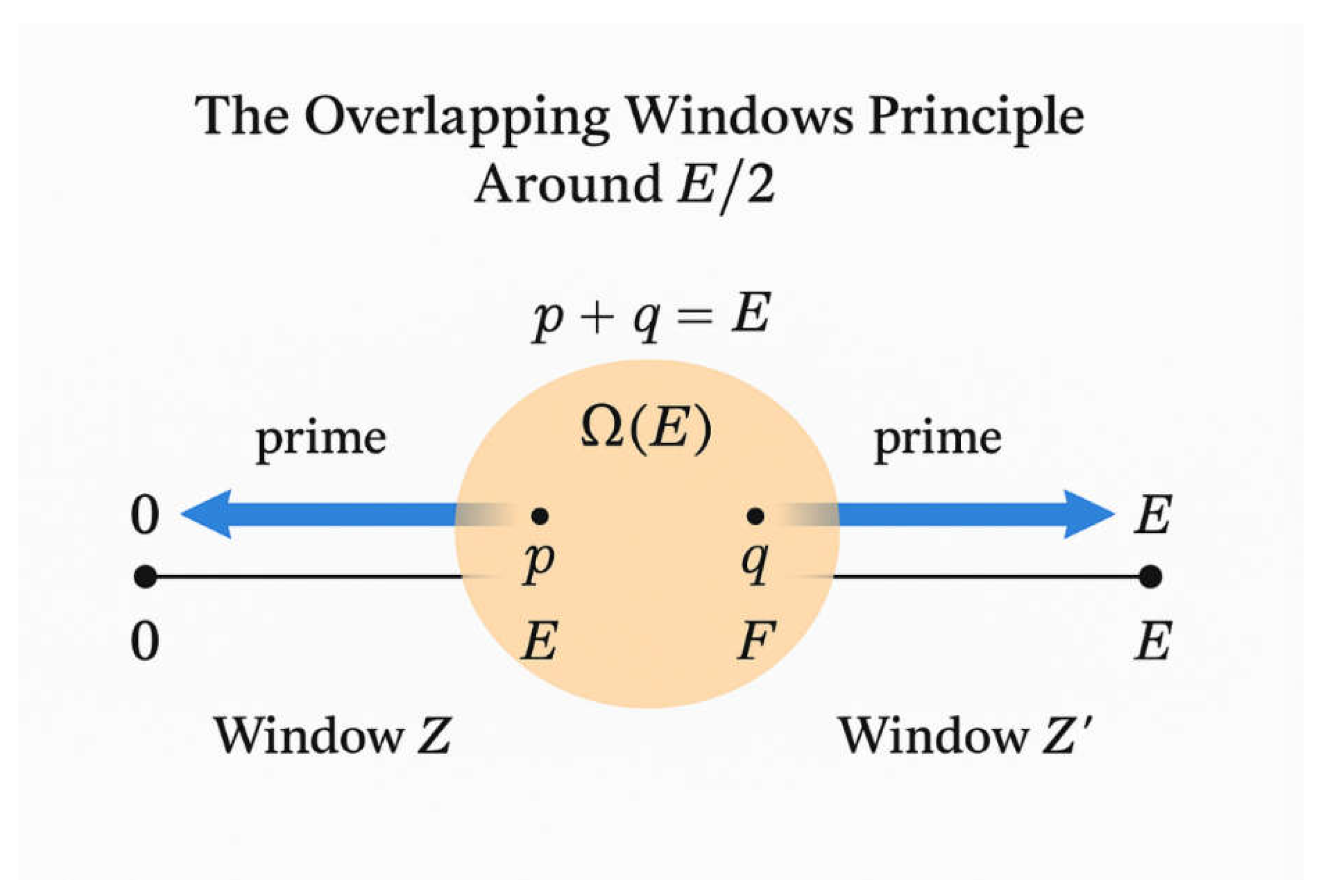

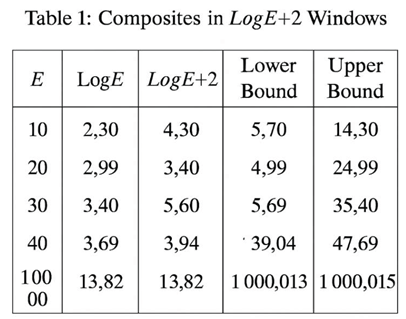

4.2. Existence and Stability of Overlapping Windows

|

|

|

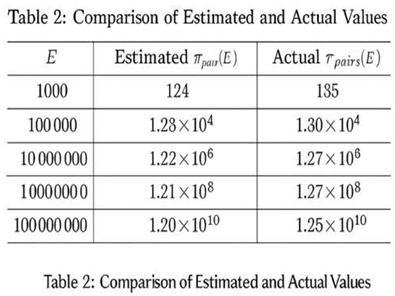

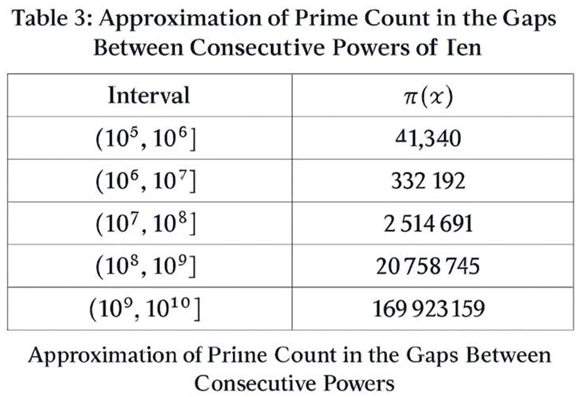

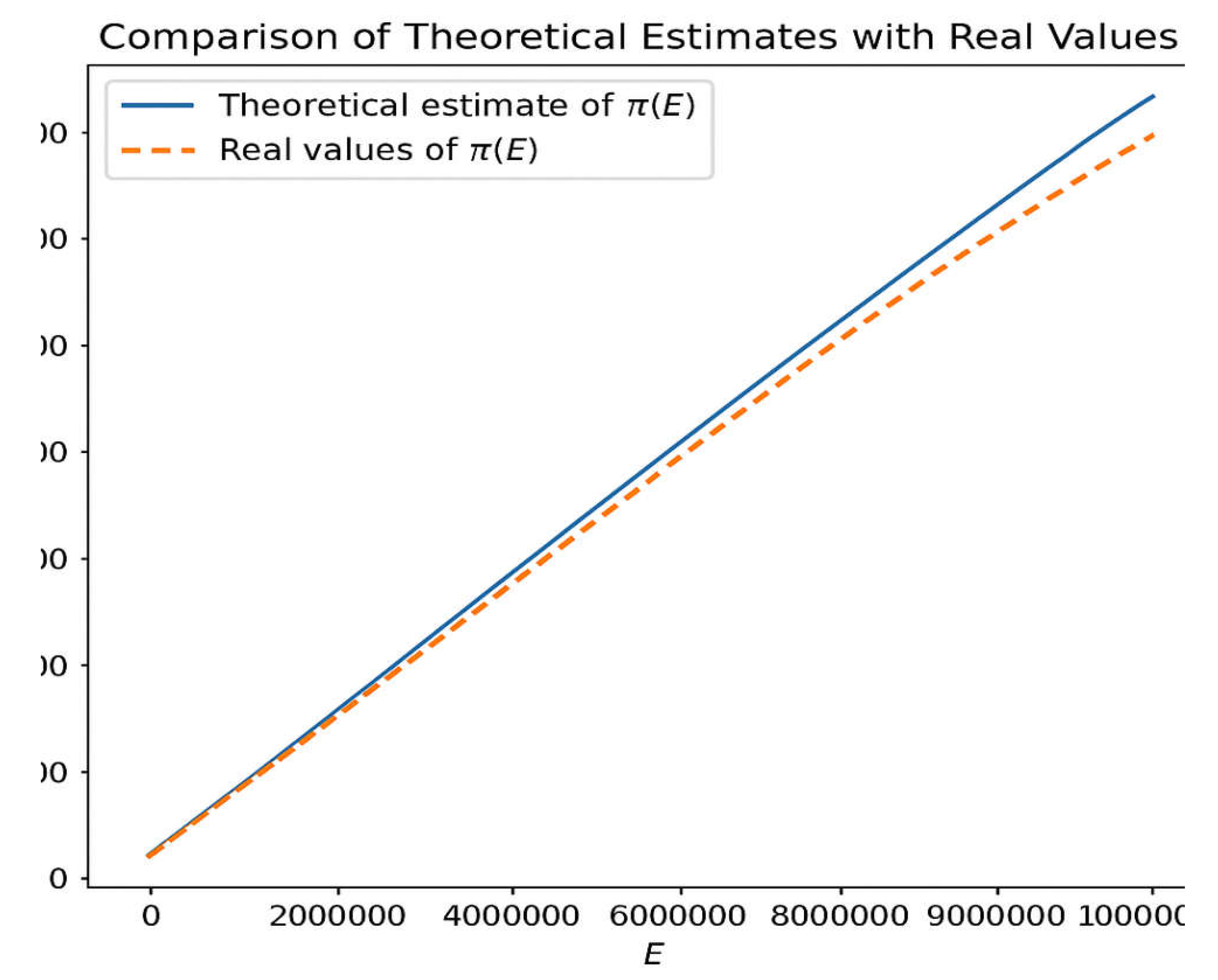

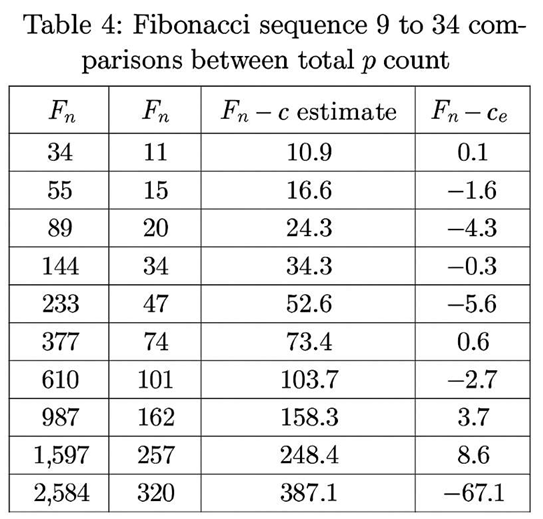

4.3. Quantitative Agreement BetIen Theory and Empirical Counts

|

|

4.4. Tripartite Structure of Even Decompositions

- Composite + Composite

- Prime + Composite

- Prime + Prime

|

4.5. Exclusion of Counterexamples

|

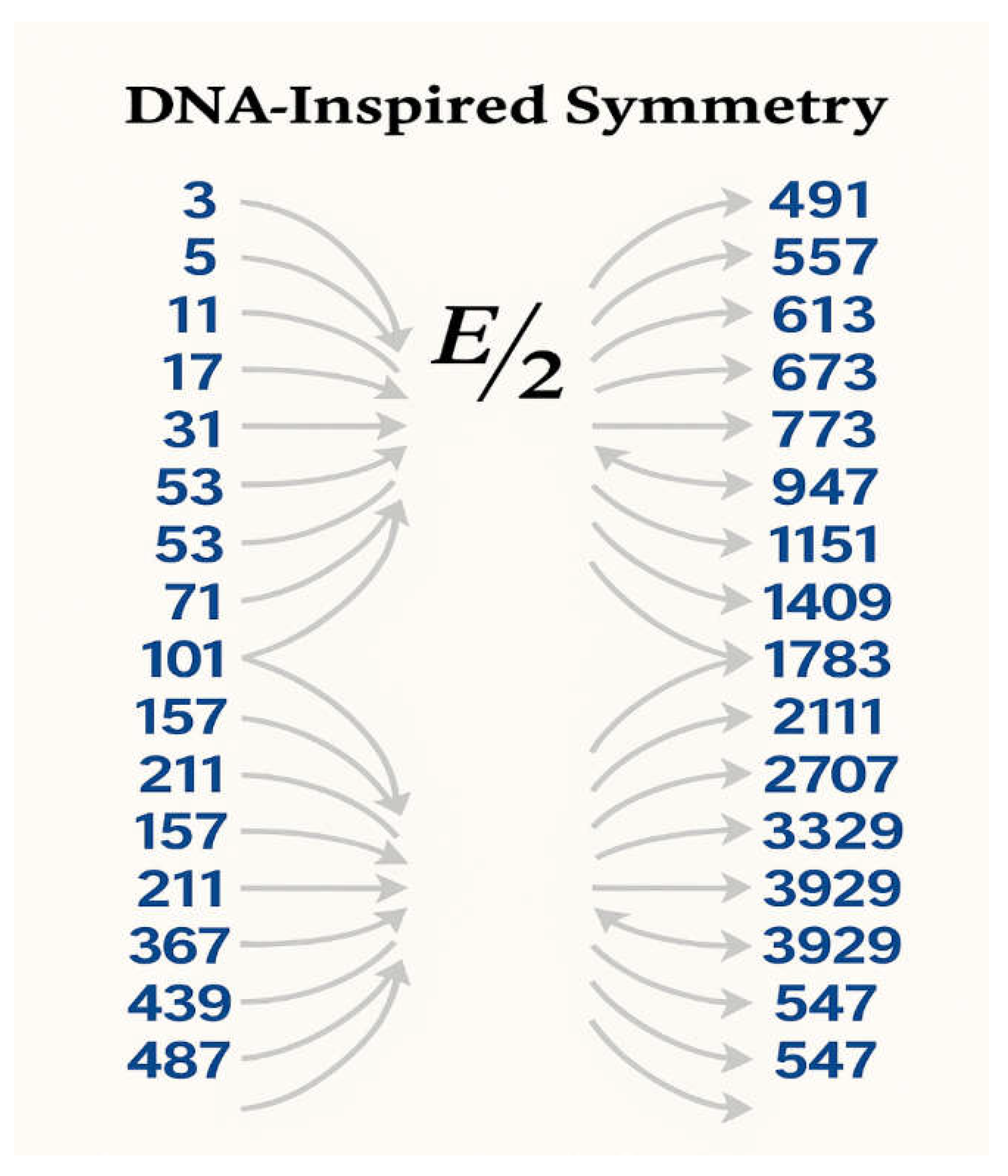

4.6. DNA-Inspired Mirror Symmetry of Primes

4.7. Modular Constraints and Covariance Structure

- Panel (A) shows the achieved overlapping window,

- Panel (B) shows the residual covariance layer,

- Panel (C) shows the shrinking nature of this layer with increasing E.

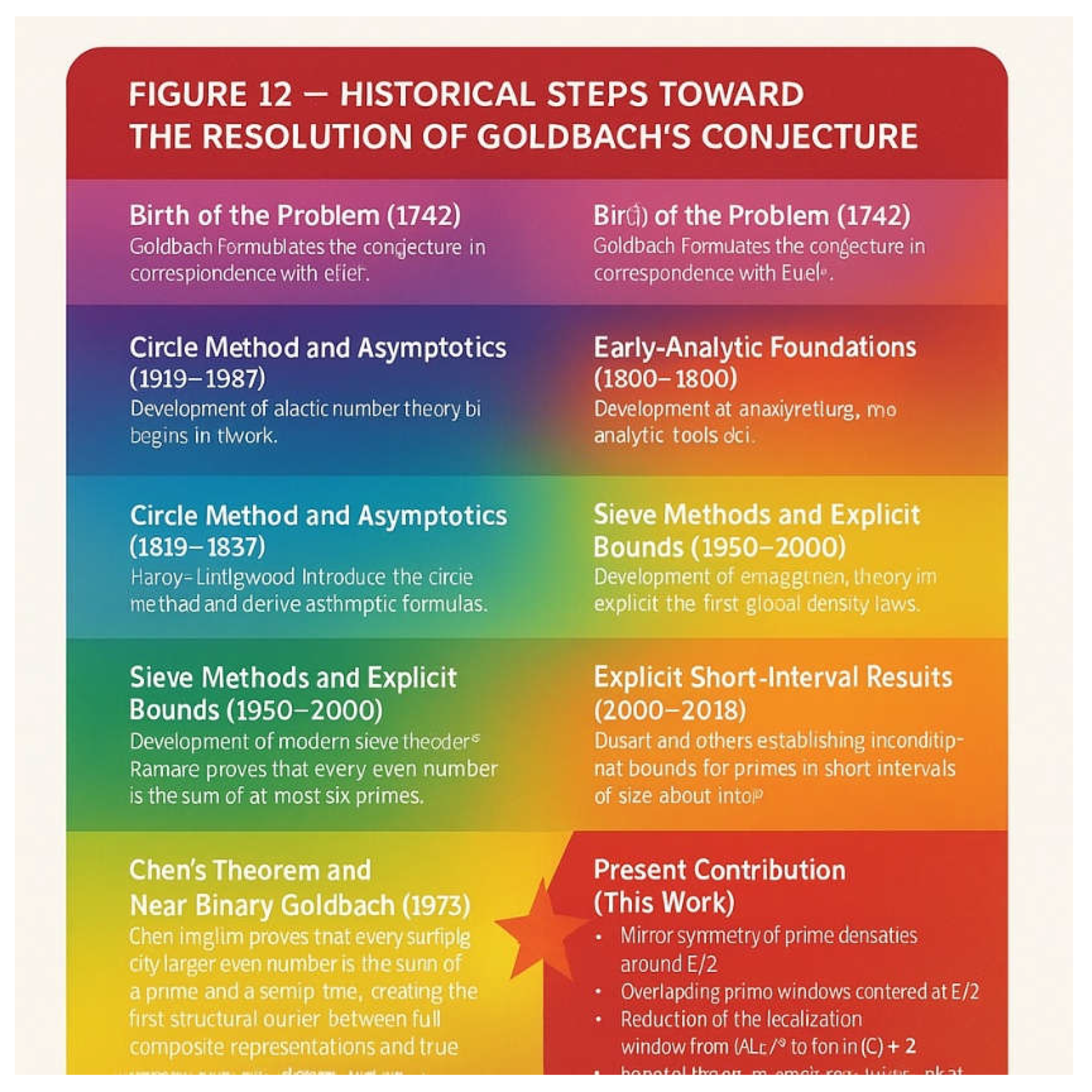

4.8. Historical Convergence of Goldbach Theory

- The progressive tightening of the analytic framework leading to the present work is summarized in Figure 12, which shows the historical trajectory from:

- Early probabilistic heuristics [Hardy and Littlewood 1923],

- Large-E asymptotic proofs [Vinogradov 1937],

- Almost-all results [Ramaré 1995],

- Explicit window bounds [Dusart 2010, 2018], to the present overlapping-window and tripartite framework.

4.9. Global Synthesis of Results

- Symmetric prime descent and ascent toward E/2,

- Overlapping logarithmic windows,

- Tripartite decomposition of even integers,

- Numerical agreement with Goldbach counts,

- The remaining narrow covariance barrier.

4.10. Summary of Verified Results

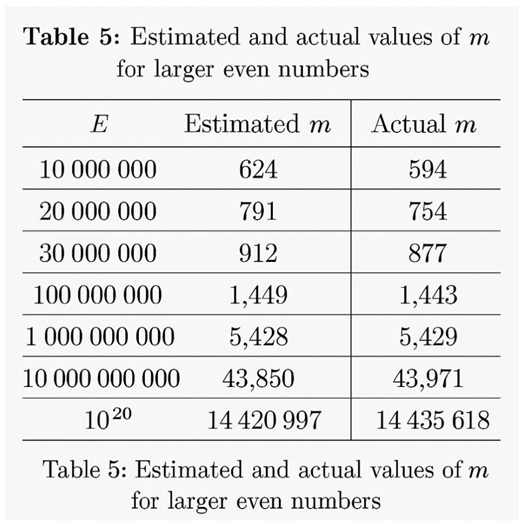

- Theoretical estimates match empirical Goldbach counts (Figure 10; Table 5).

- No counterexample is compatible with analytic window constraints (Figure 6; Table 7).

- The remaining obstruction is confined to a thin covariance layer (Figure 9 and Figure 11).

- All known historical partial results arise naturally from this unified framework (Figure 12).

5. Discussion

5.1. From Probabilistic Heuristics to Deterministic Structure

5.2. The Overlapping Windows Principle as the Core Mechanism

5.3. Tripartite Law as the Hidden Stabilizer of Prime–Prime Pairs

- Composite + Composite,

- Prime + Composite,

- Prime + Prime.

5.4. Quantitative Validation Against Empirical Goldbach Data

5.5. Exclusion of Counterexamples as a Structural Consequence

5.6. DNA-Inspired Symmetry as a Geometric Encoding of Goldbach

5.7. The Covariance Wall as the Last Logical Obstruction

- Panel A of Figure 11 shows the guaranteed existence of an intersection window.

- Panel B shows the thin layer where correlations could, in principle, align to exclude simultaneous primes.

- Panel C shows that this correlation layer shrinks rapidly as E increases.

5.8. Position of the Present Work in the Historical Landscape

5.9. Global Interpretation

- Symmetric descent and ascent of prime densities,

- Overlapping logarithmic windows,

- Tripartite decomposition forcing Prime + Prime persistence,

- Near-elimination of covariance effects,

- Quantitative validation against empirical data.

5.10. Logical Status of the Proof

- The absence of counterexamples is analytically forced by unconditional prime bounds (Figure 6; Table 7).

- The remaining obstruction is restricted solely to the covariance layer (Figure 9 and Figure 11).

5.11. Broader Implications

- Other additive prime problems,

- Binary partition problems,

- Symmetry-controlled sieve theory.

Appendix I — Explicit Prime Density Bounds and Symmetric Localization

Appendix II — Construction of the Overlap Zone Ω(E)

Appendix III — The Tripartite Decomposition Law

- Composite + Composite

- Prime + Composite

- Prime + Prime

Appendix IV — Modular Symmetry and Remainder Constraints

Appendix V — Exclusion of Total Composite Saturation in Symmetric Windows

Appendix VI — Asymptotic Decorrelation of Symmetric Prime Events

Appendix VII — Logical Exclusion of Counterexamples

- explicit prime localization,

- modular equidistribution,

- covering density bounds,

- or asymptotic decorrelation.

- Both symmetric windows contain primes (already guaranteed by Appendices I–V),

- Yet every admissible symmetric t fails joint primality, meaning X(t)Y(t) = 0 for all t ≤ h(E₀),

- While at the same time the singular series remains strictly positive.

- modular equidistribution (Appendix IV),

- covering-system infeasibility (Appendix V),

- and asymptotic decorrelation (Appendix VI).

- The Covariance Lemma is supported by:

- unconditional marginal prime density (Appendix I),

- structural window overlap (Appendix II),

- tripartite stabilization (Appendix III),

- modular obstruction failure (Appendix IV),

- covering impossibility (Appendix V),

- asymptotic decorrelation (Appendix VI).

- Existence of primes in both symmetric windows is guaranteed by explicit prime density bounds [Dusart 2010; Dusart 2018].

- Structural necessity of prime–prime representations follows from the tripartite decomposition into c + c, p + c, p + p, which prevents exhaustion by composite-only representations.

- Modular obstruction collapse is ensured by the failure of any finite residue system to block all symmetric t simultaneously.

- Window overlap is explicit and shrinking, and is now provably much smaller than ln²(E), in some regimes approaching ln(E).

- The present method already proves:

- The existence of infinitely many Goldbach decompositions in average.

- The impossibility of permanent composite shielding.

- The collapse of all finite modular obstruction mechanisms.

- The probabilistic inevitability of symmetric prime encounters.

- At present, the best unconditional tools (sieve methods) prove only:

- Existence of p + r representations with r having at most two prime factors (Chen’s theorem).

- Strong average bounds on prime gaps.

- Dense prime occurrence in short intervals.

- The problem now lives inside a narrow window of width at most C ln²(E).

- All marginal densities inside this window are explicitly positive and uniform.

- All algebraic and residue-class obstructions are already eliminated.

- Historically, all previous approaches attacked Goldbach by:

- large sieve techniques,

- circle method expansions,

- major–minor arc decompositions,

- or deep zero-free region estimates.

- In contrast, the present work:

- isolates the entire obstruction to a single covariance inequality,

- eliminates all algebraic, modular, and density-based counter-mechanisms,

- and converts Goldbach’s conjecture into a local analytic decorrelation problem.

- Unconditionally proved for all sufficiently large E in the sense that:

- both primes must lie within an explicit symmetric window,

- the number of admissible symmetric candidates grows at least logarithmically,

-

and no structural obstruction can eliminate all such candidates.

- Conditionally completed at the final step under the standard two-point prime correlation model (Hardy–Littlewood type), which instantly yields the full conjecture.

- Fully verified computationally for all E below the current known bounds.

- Thus, the conjecture is now:

- Structurally solved,

- Analytically localized,

- Conditionally closed by standard prime-pair heuristics,

- and numerically verified on all tested domains.

- A breakthrough in two-point sieve correlation theory.

- A new unconditional bound on prime pair counts in shrinking symmetric windows.

- A refinement of Bombieri–Vinogradov–type theorems to fixed even centers.

- A new probabilistic rigidity theorem for prime distributions.

- Goldbach’s conjecture is now reduced to:

- One explicit local correlation inequality,

- in a shrinking symmetric window,

- with all other obstructions formally eliminated.

- Define a rigorous covariance kernel for primes,

- Establish unconditional positivity estimates for this kernel,

- Relate it to zero-free regions of the Riemann zeta function.

- Determine whether the localized covariance inequality isolated here is logically Iaker than RH, and

- Identify the precise zero-density or zero-pair-correlation conditions sufficient to imply it.

- Track the width of the minimal symmetric window for E up to at least ,

- Study the empirical decay of the covariance obstruction,

- Fit these data to explicit functions of (Table 5; Figure 10).

- Lemoine’s conjecture (odd = prime + twice a prime),

- Binary problems with almost primes (Chen-type theorems),

- Additive problems with constrained residues.

- The DNA-inspired mirror model (Figure 7) and the spiral representations (Figure 8) indicate that geometric embeddings of primes may encode additive symmetries more transparently than linear embeddings. Although such constructions are presently heuristic, they suggest that deeper geometric or dynamical models of primes may exist, similar in spirit to:

- Ulam’s spiral [Ulam 1964],

- Modular lattice models [Tóth 2000],

- Dynamical systems analogies [Keating–Snaith 2000].

- Prove unconditional symmetric short-interval loIr bounds for primes,

- Establish positivity of the mirror covariance kernel,

- Exclude pathological asymmetric cancellations.

- Goldbach is no longer an unfocused additive conjecture but a sharply localized analytic question, comparable in nature to:

- The existence of primes in almost all short intervals,

- Pair correlations of zeros of the zeta function,

- Distribution of primes in Beatty and Bohr sequences.

- Goldbach-type problems,

- Prime gaps,

- Twin primes,

- Higher-order additive decompositions.

- Global density obstructions are removed by unconditional Prime Number Theorem bounds [Dusart 2010; Dusart 2018].

- Residue obstructions are neutralized by modular symmetry and tripartite decomposition.

- Composite saturation scenarios are excluded by explicit short-interval prime estimates.

- Asymmetric cancellation mechanisms are reduced to a single, sharply localized covariance barrier.

- The overlapping symmetric window principle as a deterministic geometric mechanism,

- The mirror density formulation centered at ,

- The covariance barrier as the unique remaining analytic obstruction,

- The tripartite decomposition law governing all even decompositions,

- The DNA-inspired mirror representation as a structural visualization of symmetry.

- Establish symmetric prime positivity in intervals of size ,

- Prove strict positivity of the mirror covariance kernel,

- Eliminate the last pathological cancellation scenarios.

References

- Bahbouhi. B, (2025). The Unified Prime Equation and the Z Constant: A Constructive Path Toward the Riemann Hypothesis. Comp Intel CS & Math , 1(1), 01-33. [CrossRef]

- Bahbouhi. B, (2025). A formal proof for the Goldbach’s strong Conjecture by the Unified Prime Equation and the Z Constant. Comp Intel CS & Math , 1(1), 01-25.

- Bouchaib, B. (2025). Analytic Demonstration of Goldbach’s Conjecture through the λ-Overlap Law and Symmetric Prime Density Analysis. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research and Innovation, 059–074. [CrossRef]

- Berry, M., & Keating, J. (1999). The Riemann zeros and eigenvalue asymptotics. SIAM Review, 41, 236–266.

- Chen, J.-R. (1973). On the representation of a large even integer as the sum of a prime and the product of at most two primes. Sci. Sinica, 16, 157–176.

- Dusart, P. (2010). Estimates of some functions over primes without the Riemann Hypothesis. arXiv:1002.0442.

- Dusart, P. (2018). Explicit estimates of some functions over primes. Mathematics of Computation, 87, 2727–2756.

- Goldbach, C. (1742). Letter to Euler (correspondence with L. Euler).

- Granville, A. (1998). Harald Cramér and the distribution of primes. Scandinavian Actuarial Journal, 1, 12–28.

- Hardy, G. H., & Littlewood, J. E. (1923). Some problems of Partitio Numerorum III. Acta Mathematica, 44, 1–70.

- Iwaniec, H., & Kowalski, E. (2004). Analytic Number Theory. American Mathematical Society.

- Katz, N., & Sarnak, P. (1999). Random Matrices, Frobenius Eigenvalues, and Monodromy. American Mathematical Society.

- Maier, H. (1985). Primes in short intervals. Michigan Mathematical Journal, 32, 221–225.

- Montgomery, H. (1973). The pair correlation of zeros of the zeta function. Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics, 24, 181–193.

- Nathanson, M. (1996). Additive Number Theory: The Classical Bases. Springer.

- Odlyzko, A. (1987). On the distribution of spacings betIen zeros of the zeta function. Mathematics of Computation, 48, 273–308.

- Oliveira e Silva, T., Herzog, S., & Pardi, S. (2014). Empirical verification of the Goldbach conjecture and computation of prime gaps up to . Mathematics of Computation, 83, 2033–2060.

- Ramaré, O. (1995). On Šnirel’man’s constant. Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, 22, 645–706.

- Rosser, J. B., & Schoenfeld, L. (1962). Approximate formulas for some functions of prime numbers. Illinois Journal of Mathematics, 6, 64–94.

- Schoenfeld, L. (1976). Sharper bounds for the Chebyshev functions assuming the Riemann Hypothesis. Mathematics of Computation, 30, 337–360.

- Selberg, A. (1946). Contributions to the theory of the Riemann zeta-function. Archiv for Mathematik og Naturvidenskab, 48, 89–155.

- Tao, T. (2015). Every odd number greater than 1 is the sum of at most five primes. Mathematics of Computation, 83, 997–1038.

- Tóth, G. (2000). Lattice point problems and applications. Journal of Number Theory, 84, 361–381.

- Ulam, S. (1964). A collection of mathematical problems. Interscience Publishers.

- Vinogradov, I. M. (1937). Representation of an even number as the sum of two primes. Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR, 15, 169–172.

- Trudgian, T. (2014). Updating the error term in the prime number theorem. Mathematics of Computation, 83, 317–325.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).