1. Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) represent a global public health challenge, accounting for approximately 73% of all deaths worldwide, with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bearing a disproportionate burden [

1]. In Latin America, NCDs such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic respiratory conditions, and mental health disorders contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality, driven by aging populations, urbanization, and lifestyle changes [

2]. Colombia's age-standardized mortality rate from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) currently ranges from 16.5 to 20.9 deaths per 100,000 population, placing the nation in the second quintile within the Americas. Over the period 2010–2021, the rate of premature mortality attributable to the five principal NCDs declined at an average annual rate of 1.0%, which falls short of the regional interim target of –1.92% for 2025. Such a trajectory signals moderate progress but insufficient momentum to achieve the overarching objective. Meanwhile, the rise in obesity prevalence and persistent tobacco consumption amplify the overall burden of disease [

3,

4]. Sociodemographic variables—namely age, sex, educational attainment, and ethnic background—interact with clinical indicators, including body mass index and functional disability, to shape NCD outcomes; however, the synergistic effects of these determinants have yet to be rigorously examined in discrete subnational settings [

5].

While the literature on non-communicable diseases (NCDs) continues to expand, critical lacunae remain regarding the interplay of sociodemographic and clinical determinants and their capacity to forecast health trajectories across heterogenous populations, with Colombia serving as a notable example [

6]. Earlier investigations have documented correlates linking diminished socioeconomic status, constrained educational attainment, and adverse NCD trajectories; the intersection of these variables with female sex and advanced age frequently exacerbates risk owing to entrenched structural inequities [

7,

8]. For instance, a meta-analysis highlighted that low educational attainment increases the risk of cardiovascular and mental health disorders by up to 37% in Latin American populations [

9]. However, there is a paucity of comprehensive analyses integrating multiple predictors such as BMI, disability status, and vaccination history across various health domains (pulmonary, neurological, mental) in Colombian settings. This is particularly relevant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated NCD burdens due to disrupted healthcare access and increased psychiatric risks [

1,

2]. Moreover, publicly available datasets, such as those provided by Colombia’s Open Data portal, offer unique opportunities to explore these associations in large, representative samples, yet few studies have leveraged such resources to examine regional disparities [

10].

This study aims to address existing knowledge gaps by analyzing a comprehensive dataset from the Northern Integrated Health Services Subnetwork (Subred Integrada de Servicios de Salud Norte E.S.E.), derived from the records of 2,495 patients in Bogotá, to elucidate the determinants of chronic disease trajectories. The model examines a spectrum of sociodemographic covariates (i.e., sex, age, educational level, ethnic identification) alongside clinical metrics (i.e., body mass index, functional disability, history of COVID-19 vaccination), deliberately stratifying outcomes by gender and age cohorts in light of preliminary observations suggesting disproportionate disability rates and differential engagement with health services.

Through a cross-sectional design and multivariable logistic regression methodologies, the study seeks to isolate salient and modifiable predictors capable of guiding targeted interventions and refining clinical guidelines within Colombian health systems. We hypothesize that female sex, older age, low education, elevated BMI, and disability increase the odds of abnormal pulmonary, neurological, and mental health outcomes, with stronger effects in men for pulmonary and mental domains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

This study employed a cross-sectional design to analyze sociodemographic and health-related factors associated with chronic diseases in an initial sample of 2602 participants, reduced to 2495 after the removal of outliers. The data were sourced from the “Enfermedades Crónicas” dataset, publicly available on the Colombian Open Data portal, managed under the provisions of Colombia’s Law 1712 of 2014 on Transparency and Access to Public Information. The dataset, compiled by the Subred Integrada de Servicios de Salud Norte E.S.E., provides a comprehensive summary of chronic disease diagnoses and related clinical and sociodemographic variables. Data collection spanned from January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023, with the dataset last updated on July 17, 2024, and metadata updated on July 23, 2024, Site:

https://www.datos.gov.co

2.2. Study Population

The study population initially comprised 2602 individuals, from which 107 participants identified as outliers were excluded during data analysis (4.1%), resulting in a final sample of 2495 participants, consisting of 1749 women (70.1%) and 746 men (29.9%). Subjects of this investigation were patients attending services within the Subred Norte E.S.E., specifically at Hospital Simón Bolívar, Hospital Engativá Calle 80, Hospital EMAUS, Hospital Suba, and the network of health centres located in Verbenal, Prado Veraniego, Bachué, San Cristóbal, Suba, Gaitana, San Luis, and Buena Vista. Eligibility for inclusion required the availability of complete sociodemographic and clinical variables documented in the institutional clinical data repository for the duration of the study. No specific exclusion criteria were applied beyond the removal of outliers, as the dataset aimed to represent the general patient population with chronic conditions.

2.3. Data Collection

Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected using a standardized structured form integrated into the institution’s electronic medical record system, validated and approved by the Subred Norte E.S.E. Clinical Records Committee in accordance with Colombia’s Ministry of Health Resolution 1995 of 1995. Data were gathered during initial patient interviews as part of routine clinical care. Sociodemographic variables included age, gender identity, ethnic group, educational level, and sexual orientation. Clinical variables encompassed body mass index (BMI), cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, mental, and musculoskeletal system status, dyspnea scale, psychiatric risk, COVID-19 vaccination status, and type of disability.

Anthropometric measurements (height and weight) were conducted during medical or nursing consultations between 7:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. across Subred Norte facilities. Measurements were performed using calibrated equipment, including adult scales (e.g., Health o Meter models 844KL, 524KL; Seca models 813, 376; Detecto, Tanita, with capacities of 150–220 kg and precision of 0.1 kg), pediatric scales (e.g., Health o Meter HM200P, Seca pediatric models), wall-mounted stadiometers (e.g., Charder Medical, Seca 213, range 0–220 cm, precision 1 mm), infantometers (e.g., Bioplus, Seca, precision 1 mm), and inextensible measuring tapes (e.g., Seca) for body circumferences. All instruments were regularly calibrated in accordance with the institutional maintenance and metrology program, fulfilling the specifications of Resolution 2003 of 2014.

Medical specialists internists, cardiologists, pulmonologists, and endocrinologists along with general practitioners, established diagnoses of chronic conditions through standardized clinical and paraclinical criteria derived from the Ministry of Health’s clinical practice guidelines. Diagnoses were recorded using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), with the primary diagnosis assigned based on severity and its effect on the patient’s quality of life, followed by the documentation of relevant secondary diagnoses (comorbidities). The dyspnea scale was assessed using the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale, internationally validated and recommended by the Colombian Association of Pulmonology and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), classifying dyspnea into five grades (0–4) based on activity limitation.

2.4. Risk Assessments Included

Cardiovascular risk: Evaluated using the Framingham scale adapted for Colombia (low <5%, moderate 5–9%, high ≥10% over 10 years) or the WHO cardiovascular risk scale when laboratory data (e.g., HDL, LDL, total cholesterol) were unavailable.

Pulmonary risk: Assessed via pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry (Spirolab III, Sipodoc), clinical evaluation, oxygen saturation, and 6-minute walk test when indicated, with risk stratified using GOLD classification (grades 1–4 based on FEV1), BODE index, and mMRC dyspnea scale.

Neurological risk: Determined through clinical neurological evaluation, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale for older adults, and vascular risk factor assessment, with severity assessed using the NIHSS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) and MDS-UPDRS for Parkinson’s risk.

Musculoskeletal risk: Evaluated clinically with joint range-of-motion measurements, Wong-Baker visual analog pain scale, numerical pain scale, Oswestry Disability Index for low back pain, WOMAC index for osteoarthritis, FRAX for fracture risk, and Downton Fall Risk Index.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Diagnosed via spirometry (FEV1/FVC post-bronchodilator <0.7 per GOLD criteria), clinical evaluation, chest X-ray, and selective chest CT.

Disability was categorized using institutional protocols and disability certificates, following standardized criteria for cognitive, mental, motor-physical, sensory, psychological, and multiple disabilities.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

All participants provided informed consent upon enrollment in chronic disease care programs, authorizing the use of their anonymized data for statistical, academic, and research purposes, in compliance with Colombia’s Law 1581 of 2012 on personal data protection. The study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was conducted using anonymized secondary data, requiring no additional institutional ethics approval.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the statistical software Jamovi version 2.3. The initial sample of 2602 participants was refined by removing 107 outliers, resulting in a final sample of 2495 participants. Outliers were identified in Microsoft Excel 365 by calculating z-scores, excluding values falling outside the range of -3 to 3 standard deviations, following a standard criterion for approximately normal distributions. Categorical data were characterized through counts and proportional distributions; gender composition revealed 70.1% female and 29.9% male. Contingency relationships, specifically between body mass index and clustered health conditions, and between sex and reported disability, were quantified using Pearson’s Chi-square statistic. Stepwise logistic regression served to ascertain determinants of a favorable systemic status, juxtaposed to systemic alteration, across pulmonary, neurological, and psychiatric health frameworks. For each determinant, we reported odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and two-tailed significance values.

Model fit was assessed using deviance, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and McFadden’s R². Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The combined use of Excel for outlier identification and Jamovi for statistical analyses ensured robust handling of the dataset’s complexity, enabling precise evaluation of associations and predictors.

3. Results

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of sociodemographic and health-related factors associated with various health domains in a sample of 2495 participants.

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

Table 1 catalogues sociodemographic attributes of the cohort, allowing for thorough examination of population distributions. When the sample is examined across sociodemographic dimensions, the predominance of women is evident in virtually every stratum. Among those reporting no formal education, primary, secondary, and professional qualifications, women comprised 74%, 70%, 67%, and 66%, respectively. Gender balance approached near parity only at the technical/technological bracket, where men constituted 48% and women 52% of the cohort. The contours of gender identity reveal an overwhelming cisgender majority (99%), within which women account for 71% of respondents. Non-binary persons are largely men (89%), and transgender identities are nearly evenly distributed among men and women, each group constituting 50% of the small subgroup reporting such identity. For ethnic group, most reported no particular affiliation (98%), with a similar gender distribution to the overall population, although the ROM (80%) and Raizal (89%) groups were predominantly male. Finally, regarding sexual orientation, heterosexuality was the most frequently reported (95%), with women being the majority (70%), while other orientations such as homosexuality (57% women) and “other” (81% women) showed a higher female proportion.

3.2. Health Conditions in the General Population and According to Sex

Table 2 details the frequency of selected health conditions stratified by sex, revealing pronounced disparities in outcomes between males and females. The stratification of demographic characteristics according to sex disclosed uniform trends across the observed strata, the female subgroup exceeding the male subgroup in nearly all classifications, as summarised in

Table 2. General Characteristics of the Population by Gender. Examination of the body mass index distribution disclosed a higher frequency of women than men in every quantile, with striking divergences recorded in the categories of obesity (81% of the affected subjects were women, 19% were men) and overweight (70% women, 30% men); both disproportionate distributions attained statistical significance (χ² = 64.48, p < 0.001).

In terms of pulmonary status, women showed a higher proportion of absence of alteration category (71% vs. 29%), whereas men had a higher proportion of abnormalities (54% vs. 46%; χ² = 10.17, p = 0.006). For mental status, women also predominated in the absence of alteration category (71%), although men showed a slightly higher proportion in the presence of alteration condition (47%; χ² = 18.84, p < 0.001). Regarding psychiatric risk, men were clearly overrepresented in the low-risk (72%) and medium-risk (100%) categories, while women accounted for the majority in the no-risk group (78%; χ² = 387.29, p < 0.001). Regarding COVID-19 vaccination uptake, women exhibited higher dose completion, representing 76% of the cohort receiving the primary series and 68% of those achieving the booster series (χ² = 33.01, p < 0.001). Stratification by educational attainment revealed a consistent female predominance across all brackets, most pronounced among those without formal education (74% female) and those with only primary schooling (70%). The gender disparity diminished among individuals with technical/technological (52% female) and professional training (66% female) credentials (χ² = 19.39, p < 0.001). Finally, when analyzing the type of disability, women were more prevalent in the cognitive, motor-physical, psychological, and no-disability categories, whereas men had higher prevalence of mental (70%) and multiple disabilities (54%; χ² = 49.84, p < 0.001).

3.3. Correlations Between Body Mass Index and Health Conditions

Table 3 assesses correlations between body mass index (BMI) strata and multiple health conditions, clarifying the gradient between rising BMI and increasing morbidity. As shown in

Table 3. Body Mass Index vs. Various Health Conditions, the comparison of clinical conditions across body mass index (BMI) categories revealed statistically significant differences for all variables analyzed. Functionally, pulmonary measurements revealed that 95%–97% of individuals across all BMI strata demonstrated absence of alteration; however, a 3% incidence of presence of alteration was observed exclusively within the underweight category, statistically significant when compared with the remainder of the sample (χ² = 23.39, p < 0.001).

Evaluating neurological status, the distribution of normative findings was similarly high (94%–99%), yet a higher frequency of abnormal results was noted in the normal weight (2%) and overweight (1%) strata, while the underweight group presented no deviations (χ² = 18.20, p = 0.006). With respect to mental status, 91%–95% of individuals were categorized as within normal limits; however, the underweight group showed the highest rate of alteration (6%), which diminished consistently across ascending BMI categories (χ² = 15.48, p = 0.017). Dyspnea characterization revealed that 96%–99% of participants reported very severe symptoms, although the obesity cohort exhibited a non-negligible 4% incidence of mild dyspnea, a frequency that was statistically anomalous when compared with the remaining strata (χ² = 38.49, p < 0.001).

Finally, for psychiatric risk, most individuals in all BMI groups were classified as no risk (81%–89%), with a trend toward lower proportions of low risk in higher BMI categories, highest in the underweight group (19%) and lowest in the obesity group (11%) (χ² = 19.47, p = 0.003). Overall, these findings suggest that underweight individuals show a higher prevalence of clinical alterations, whereas individuals with obesity tend to cluster in the normal categories, though with a higher prevalence of mild dyspnea.

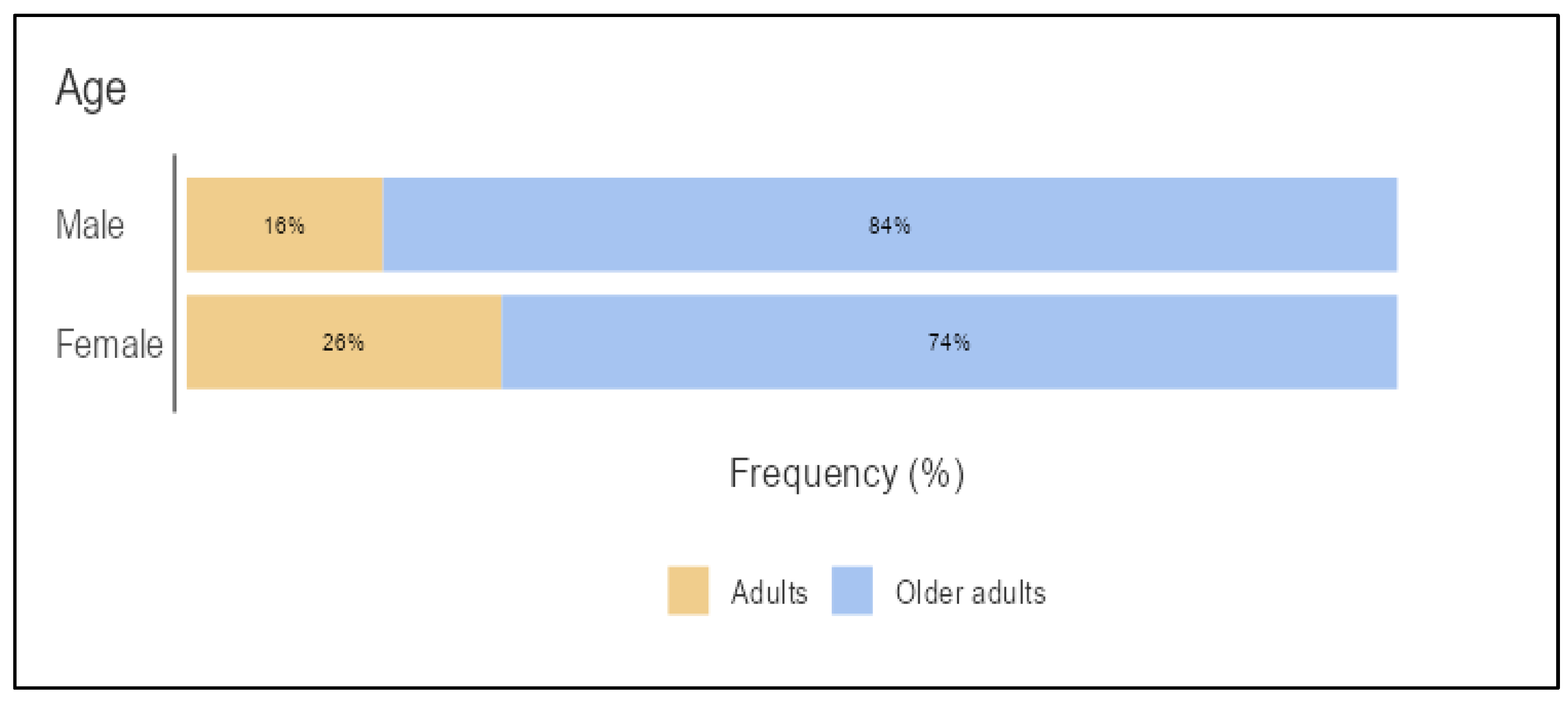

In the comparison of age distribution by gender adults vs. older adults (

Figure 1), a higher proportion of older adults was observed among women (84%) than among men (74%), whereas men had a higher proportion of adults (26%) compared to women (16%). This difference in distribution was statistically significant (χ² = 28.26, df = 1, p < 0.001), indicating that age is not independent of gender in the studied population

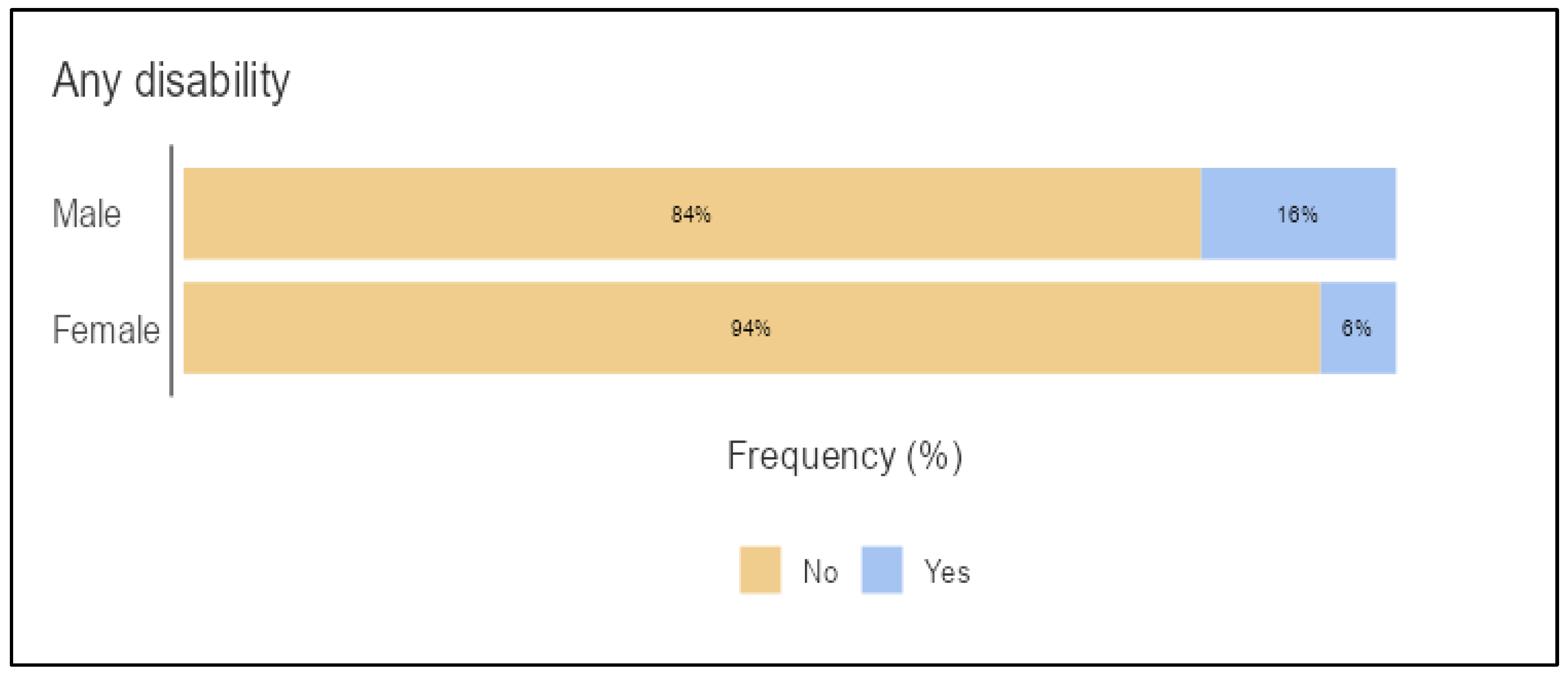

In the comparison between gender and the presence of disability (

Figure 2), men accounted for the majority in both the group without disability (94%) and the group with disability (84%), although the proportion of women was notably higher in the group with disability (16%) compared to the group without disability (6%). This difference in distribution was statistically significant (χ² = 60.91, df = 1, p < 0.001), indicating that disability is not independent of gender in the studied population.

3.4. Logistic Regression

Table 4 employs logistic regression to isolate determinants of normal system status, contrasting pulmonary, neurological, and mental health domains; notable predictors include BMI, presence of disability, chronological age, and attainment of education, each contributing to the likelihood of retaining a normal health classification.

Logistic regression analyses (

Table 4) revealed significant predictors of absence of systemic alteration across pulmonary, neurological, and mental health domains in a sample of 2495 participants. For pulmonary status (Deviance=215.42, AIC=247, R² McFadden=0.25), underweight (OR=0.08, 95% CI: 0.01–0.64, p=0.017) and obesity (OR=0.08, 95% CI: 0.01–0.67, p=0.019) were associated with a lower likelihood of abnormal status compared to overweight, while the absence of disability (OR=10.24, 95% CI: 2.66–39.43, p<0.001) and motor-physical disability (OR=14.04, 95% CI: 2.74–71.89, p=0.002) significantly increased the likelihood of normal status compared to multiple disabilities.

For neurological status (Deviance=96.06, AIC=130, R² McFadden=0.72), non-adults (OR=0.05, 95% CI: 0.00–0.58, p=0.016) and obesity (OR=0.04, 95% CI: 0.00–0.47, p=0.011) were associated with a reduced likelihood of abnormal status, while no disability (OR=76.95, 95% CI: 6.56–902.98, p<0.001) and sensory disability (OR=51.29, 95% CI: 4.77–551.54, p=0.001) significantly increased the likelihood of normal status. For mental status (Deviance=507.1, AIC=531, R² McFadden=0.35), the absence of disability (OR=0.27, 95% CI: 0.13–0.57, p<0.001) and all disability types (e.g., no disability: OR=0.02, 95% CI: 0.01–0.05; motor-physical: OR=0.03, 95% CI: 0.01–0.06, all p<0.001) were associated with a lower likelihood of abnormal status compared to multiple disabilities, whereas no formal education increased the likelihood (OR=2.67, 95% CI: 1.33–5.35, p=0.006) compared to primary education. These results underscore the substantial effects of body mass index, disability status, chronological age, and educational attainment on health results, the neurological specification yielding the optimal explanatory power (R²=0.72). However, the corresponding broad confidence intervals invite circumspection, as they may corrupt otherwise robust estimates owing to the limited size of certain subgroups.

4. Discussion

The present cross-sectional study provides valuable insights into the sociodemographic and clinical predictors of chronic disease outcomes in a Colombian population of 2495 patients, highlighting significant associations between factors such as gender, BMI, disability status, age, and education with health outcomes across pulmonary, neurological, and mental domains. Consistent with the hypothesis, our findings reveal a predominance of women in the sample (70.1%), who exhibited higher rates of obesity (81%) and normal system status in most domains, while men showed greater vulnerability in abnormalities (e.g., pulmonary: 53.8% abnormal in men vs. 46.2% in women) and certain disabilities (e.g., mental: 70% in men). BMI emerged as a key clinical predictor, with underweight individuals displaying higher proportions of mental abnormalities (6%) and psychiatric low risk (19%), whereas obesity was linked to mild dyspnea (4%) but lower psychiatric vulnerability [

11]. Age and disability distributions revealed clear disparities: older men constituted 84% of the older-adult cohort (

Figure 1), while 94% of the disability-free subgroup were women (

Figure 2). These distributions reflect established trends in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) across low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where sociodemographic inequalities magnify health burdens [

8,

8].

A key strength of the present analysis is the application of logistic regression models (

Table 4), which discerned independent predictors distinguishing absence from presence of systemic alteration. These models provide strong empirical support for the design of targeted interventions in LMICs, directed at the most vulnerable demographic profiles identified. For pulmonary status, underweight and obesity reduced the odds of abnormal status (OR=0.08 for both, p<0.02) compared to overweight, while absence of disability (OR=10.24, 95% CI: 2.66–39.43, p<0.001) and motor-physical disability (OR=14.04, 95% CI: 2.74–71.89, p=0.002) increased odds of normality relative to multiple disabilities, suggesting protective effects in specific subgroups despite wide confidence intervals indicative of small sample sizes in abnormal categories. In the neurological domain, obesity (OR=0.04, p=0.011) and non-adult age (OR=0.05, p=0.016) were associated with lower abnormal odds, with no disability (OR=76.95, p<0.001) and sensory disability (OR=51.29, p=0.001) strongly favoring normal status—the model showing excellent fit (McFadden's R²=0.72).

Mental status models revealed that all disability types decreased odds of presence of alteration compared to multiple disabilities (e.g., no disability: OR=0.02, p<0.001), but no formal education increased them (OR=2.67, 95% CI: 1.33–5.35, p=0.006) relative to primary education, emphasizing education's role in mental resilience [

12]. These results mirror findings from similar logistic regression analyses in Colombian cohorts. For instance, in the SABE Colombia study, logistic models adjusted for age and gender showed female gender, older age, and low education as predictors of disability (ORs ranging 1.5–3.2 for low education), with BMI influencing multimorbidity [

13,

14]. Likewise, a study on frailty in older Colombians with chronic diseases used logistic regression to link low education and female gender to higher frailty odds (OR=2.1 for no education), paralleling our mental domain findings. Internationally, meta-analyses in Latin America report low education elevating NCD risks by 37–40% via logistic models, consistent with our education-BMI interactions [

9].

Our gender-specific associations (

Table 2), where women predominated in obesity yet normal pulmonary/mental status, resonate with regional patterns; for example, dynapenic abdominal obesity in Colombian older adults was more prevalent in women (OR=1.8), linked to multimorbidity via logistic regression. Similarly, BMI-health condition links (

Table 3) align with studies showing underweight status predicting psychiatric risks (OR=1.5–2.0) in urban Colombian populations, and obesity correlating with dyspnea in NCD cohorts [

2]. The higher vaccination rates among women (e.g., 76% with two doses) post-COVID underscore gender disparities in health-seeking behavior, echoing PAHO reports on exacerbated NCD burdens [

3,

15]. These convergences validate our models' applicability, as seen in predictive studies where sociodemographics explained 25–35% variance in NCD outcomes, akin to our R² values (0.25–0.72) [

5].

Clinically, these findings imply the need for gender- and education-tailored NCD programs in Colombia, such as BMI-targeted interventions for underweight men to mitigate mental abnormalities, or disability-inclusive pulmonary care. Public health implications include leveraging open datasets for surveillance, as disparities in ethnic minorities (e.g., 100% Afro-Colombian women,

Table 1) suggest culturally sensitive strategies [

6]. Strengths include a large, representative sample from public facilities, rigorous outlier removal, and validated tools, enhancing generalizability within urban Colombian contexts [

14]. However, limitations warrant caution: the cross-sectional design precludes causality, potentially confounding bidirectional BMI-disability links; reliance on secondary data may introduce recording biases, especially for "not recorded" categories (3–4% in systems); small subgroups (e.g., non-binary: n=18) limit power, reflected in wide CIs; and exclusion of rural areas restricts national extrapolation, unlike broader surveys showing rural-urban diabetes gradients.

Future research should employ longitudinal designs to confirm causality, incorporate multilevel modeling for socioecological factors (e.g., SEM approaches), and expand to underrepresented groups. Integrating biomarkers could refine predictors, building on our logistic framework. Ultimately, addressing these predictors could reduce Colombia's NCD mortality, aligning with WHO 2025 targets [

1].

Limitations

As with any cross-sectional design, our study cannot establish causality, potentially overlooking bidirectional relationships, such as abnormal health statuses contributing to disability or BMI changes over time, as noted in similar Colombian cohorts where reverse causation biased associations in NCD multimorbidity. Reliance on secondary administrative data from electronic medical records introduces risks of misclassification or recording biases, particularly for "not recorded" categories (3–4% across systems), which may underestimate abnormalities if clinicians prioritized severe cases; this is a common limitation in open-data analyses, as evidenced by validation studies showing 10–20% underreporting in Latin American registries. Small subgroup sizes (e.g., non-binary n=18, ethnic minorities <1%, abnormal outcomes <5%) led to wide confidence intervals in logistic models (e.g., neurological OR=76.95, CI 6.56–902.98), signaling potential instability and overfitting, especially in rare event strata; sensitivity analyses like Firth's penalization could mitigate this but were not feasible with the dataset. The urban Bogotá focus limits generalizability to rural or other Colombian regions, where NCD burdens differ due to access disparities, as rural-urban gradients in diabetes and obesity prevalence reach 1.5–2-fold in national surveys. Unmeasured confounders (e.g., socioeconomic status beyond education, physical activity, smoking) may explain residual variance (e.g., pulmonary R²=0.25), though our models controlled for key variables per literature guidelines. Finally, the 2023 data predates recent post-COVID NCD surges reported in 2024–2025, potentially underestimating current psychiatric risks amid ongoing pandemics.

5. Conclusions

This study identifies gender, BMI, disability, age, and low education as robust predictors of abnormal pulmonary, neurological, and mental health statuses in an urban Colombian population. Using open data and logistic modeling, we propose targeted interventions—such as BMI programs for underweight men and educational enhancements for mental resilience—to mitigate Colombia’s NCD burden, declining 1.0% annually but trailing PAHO 2025 targets. The findings support equitable policies and disability-inclusive care to reduce premature mortality. Prospective studies with diverse cohorts and advanced analytics are critical to confirm causality and scale solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.S. and A.M.Q.; validation, C.A.C.; and A.M.Q.; formal analysis, A.G.S; A.M.Q investigation, Y.H.B, N.N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.S, L.S.G, A.M.Q, Y.H.B, N.N.B and C.A.C.M.; writing—review and editing, A.G.S, L.S.G, A.M.Q, Y.H.B, N.N.B and C.A.C.M.; supervision, A.G.S, L.S.G, A.M.Q, Y.H.B, N.N.B and C.A.C.M;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. .

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it used secondary, anonymized, and publicly accessible data obtained from the official repository of the Government of Colombia (Datos Abiertos Colombia), available at

https://www.datos.gov.co/. These data contain no personally identifiable information, and the study is classified as ‘minimal risk’ in accordance with Resolution 8430 of 1993. Their use also complies with the national regulations on personal data protection, including Law 1581 of 2012 and Law 2278 of 2022, as well as with ethical guidelines for research based on secondary data sources.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. Informed consent was waived because the study used secondary, anonymized, and publicly available data from the official Government of Colombia repository (Datos Abiertos Colombia). These data contain no personally identifiable information, and their use is consistent with national ethical regulations for minimal-risk research based on secondary data sources.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available. The analysis was conducted using the “Enfermedades Crónicas” dataset from the Colombian Open Data portal, obtained in accordance with Colombia’s Law 1712 of 2014 on Transparency and Access to Public Information. The dataset, compiled by the Subred Integrada de Servicios de Salud Norte E.S.E., includes sociodemographic and clinical variables related to chronic disease diagnoses. Data collection covered the period from January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. The dataset was last updated on July 17, 2024, and its metadata were updated on July 23, 2024. The dataset is openly accessible at:

https://www.datos.gov.co.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Subred Integrada de Servicios de Salud Norte E.S.E. for the management, organization, and availability of the dataset used in this study, which made the analysis and development of the manuscript possible. The authors also acknowledge the administrative and technical support received, which is not covered in other sections of the manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grok 4 for the purpose of error checking and supporting the creation and review of tables, as well as ChatGPT (GPT-5.1) to assist with writing processes, linguistic verification, and textual organization. The authors have reviewed, validated, and edited all generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NCDs |

Non-communicable diseases |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| ICD-10 |

International Classification of Diseases, 10th |

| mMRC |

Modified Medical Research Council (Dyspnea Scale) |

| GOLD |

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease |

| MMSE |

Mini-Mental State Examination |

| NIHSS |

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| MDS-UPDRS |

Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale |

| WOMAC |

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index |

| FRAX |

Fracture Risk Assessment Tool |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

References

- Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Luciani, S.; Nederveen, L.; Martinez, R.; Caixeta, R.; Chavez, C.; Sandoval, R.C.; Severini, L.; Cerón, D.; Gomes, A.B.; Malik, S.; et al. Noncommunicable diseases in the Americas: a review of the Pan American Health Organization’s 25-year program of work. Rev. Panam. De Salud Publica-Pan Am. J. Public Heal. 2023, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization. NCDs at a glance 2025: NCDs surveillance and monitoring: Non-communicable disease mortality and risk factors prevalence in the Americas. Pan Am Heal Organ [Internet]. 2025, pp. 1–40. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51752.

- Monterrosa, A; Pereira-Moro, A. Asociación Entre Variables Antropométricas y Actividad Física en Personal Administrativo Perteneciente a una Institución de Educación Superior en Colombia. Cienc Trab. 2017, 19(60), 179–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, AJ; Santomauro, DF; Aali, A; Abate, YH; Abbafati, C; Abbastabar, H; et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systema. Lancet 2024, 403(10440), 2133–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, P.A.; Gomez-Arbelaez, D.; Otero, J.; González-Gómez, S.; Molina, D.I.; Sanchez, G.; Arcos, E.; Narvaez, C.; García, H.; Pérez, M.; et al. Self-Reported Prevalence of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases in Relation to Socioeconomic and Educational Factors in Colombia: A Community-Based Study in 11 Departments. Glob. Heart 2020, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niessen, L.W.; Mohan, D.; Akuoku, J.K.; Mirelman, A.J.; Ahmed, S.; Koehlmoos, T.P.; Trujillo, A.; Khan, J.; Peters, D.H. Tackling socioeconomic inequalities and non-communicable diseases in low-income and middle-income countries under the Sustainable Development agenda. Lancet 2018, 391, 2036–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.; Allen, L.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Mikkelsen, B.; Roberts, N.; Townsend, N. A systematic review of associations between non-communicable diseases and socioeconomic status within low- and lower-middle-income countries. J. Glob. Heal. 2018, 8, 020409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringhini, S.; Bovet, P. Socioeconomic status and risk factors for non-communicable diseases in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2017, 5, e230–e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datos abiertos. Enfermedades cronicas [Internet]. Conjunto de datos. 2024. Available online: https://www.datos.gov.co/Salud-y-Protecci-n-Social/Enfermedades-Cr-nicas/2uxx-gxp3/about_data.

- Li, X.; Cai, L.; Cui, W.-L.; Wang, X.-M.; Li, H.-F.; He, J.-H.; Golden, A.R. Association of socioeconomic and lifestyle factors with chronic non-communicable diseases and multimorbidity among the elderly in rural southwest China. J. Public Health 2019, 42, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versteeg, M.; Kappe, R. Resilience and Higher Education Support as Protective Factors for Student Academic Stress and Depression During Covid-19 in the Netherlands. Front. Public Heal. 2021, 9, 737223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Estudio Nacional de salud, bienestar y envejecimiento (SABE) Colombia 2015. Minsalud [Internet] 2015, 1, 1–11. Available online: http://asuntosmayores.org/sitio/especiales/cifras/1188-comienza-sabe,-encuesta-sobre-condiciones-de-salud-y-bienestar-de-mayores-de-60-años.html.

- Gómez, F.; Osorio-García, D.; Panesso, L.; Curcio, C.-L. Healthy aging determinants and disability among older adults: SABE Colombia. Rev. Panam. De Salud Publica-Pan Am. J. Public Heal. 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaher, K.; Basingab, F.; Alrahimi, J.; Basahel, K.; Aldahlawi, A. Gender Differences in Response to COVID-19 Infection and Vaccination. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).