2.1. Hardware-Implementable Transformations of Control Systems and System Equivalence

The trajectory-tracking method proposed in this work for a differential-drive wheeled mobile robot is based on a hardware-implementable transformation of the robot’s kinematic model that converts it into an equivalent trivial linear control system. To clarify the precise meaning of the terminology used, let us consider a simple example of a hardware-implementable transformation of a control system

into an equivalent control system

. Let

be a control system with state space

, control space

, and dynamics given by (1), and let

be a control system with state space

, control space

and dynamics given by (2).

Let the state spaces of systems

and

equivalent to each other in the geometric sense of the term; that is, suppose there exists a continuous, invertible mapping

, that establishes a one-to-one correspondence between the points of the state spaces

and

. The control spaces

and

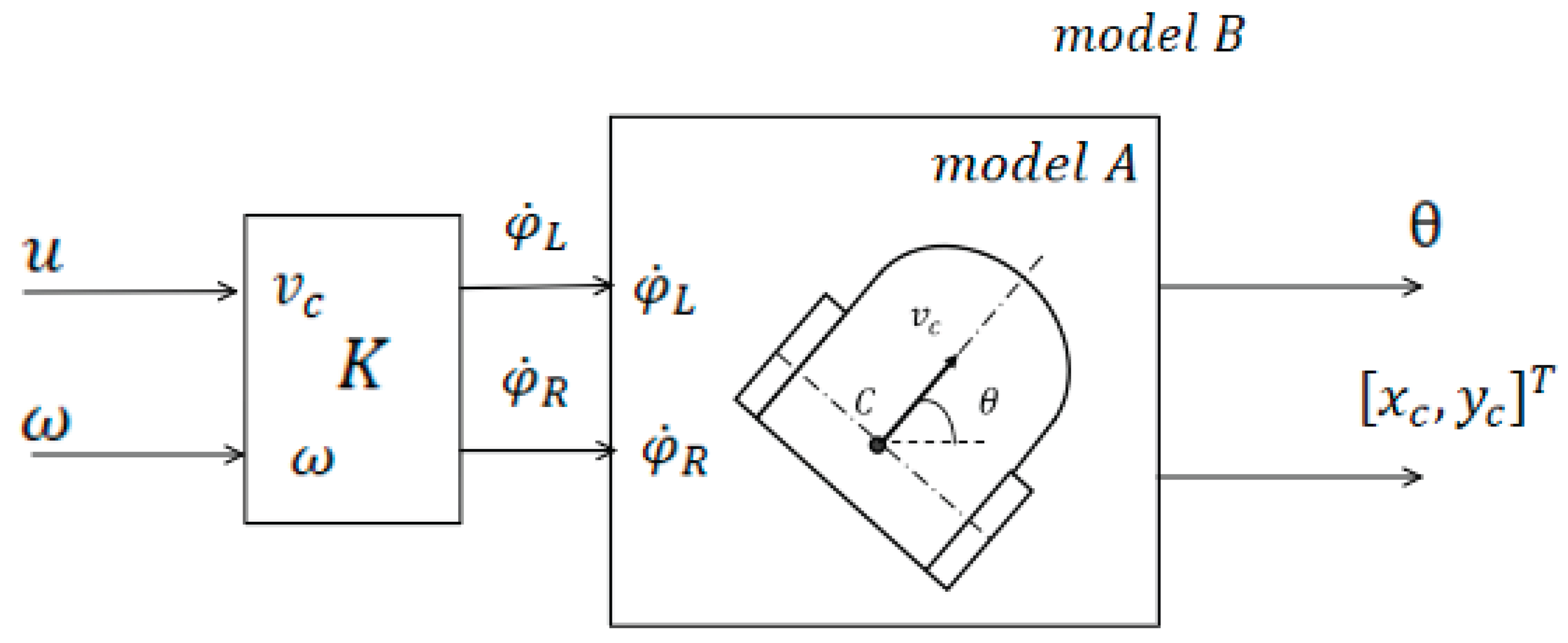

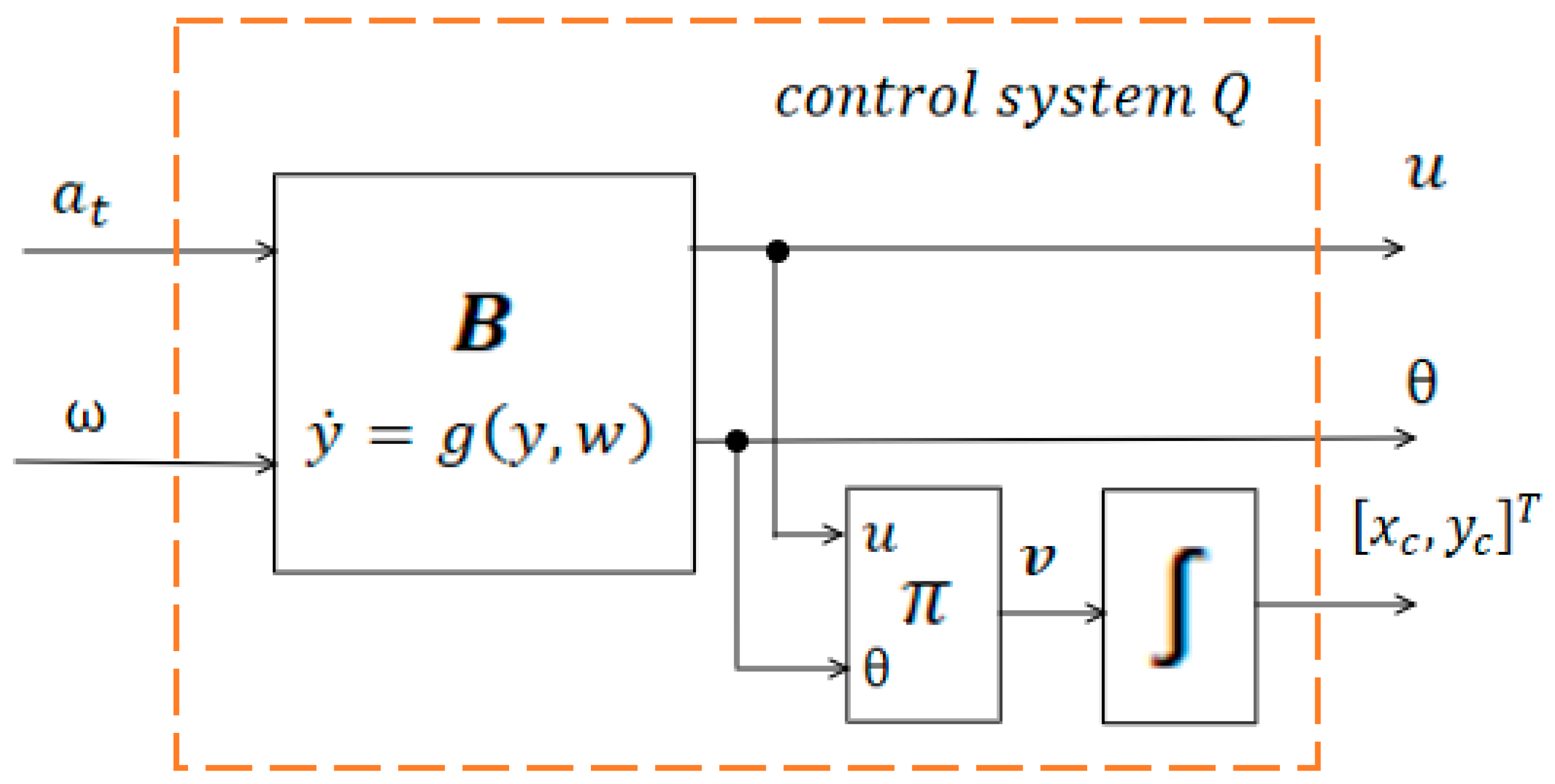

of these systems are likewise assumed to be mutually equivalent. Consider now the scheme of a hardware-implementable transformation of system B, shown in

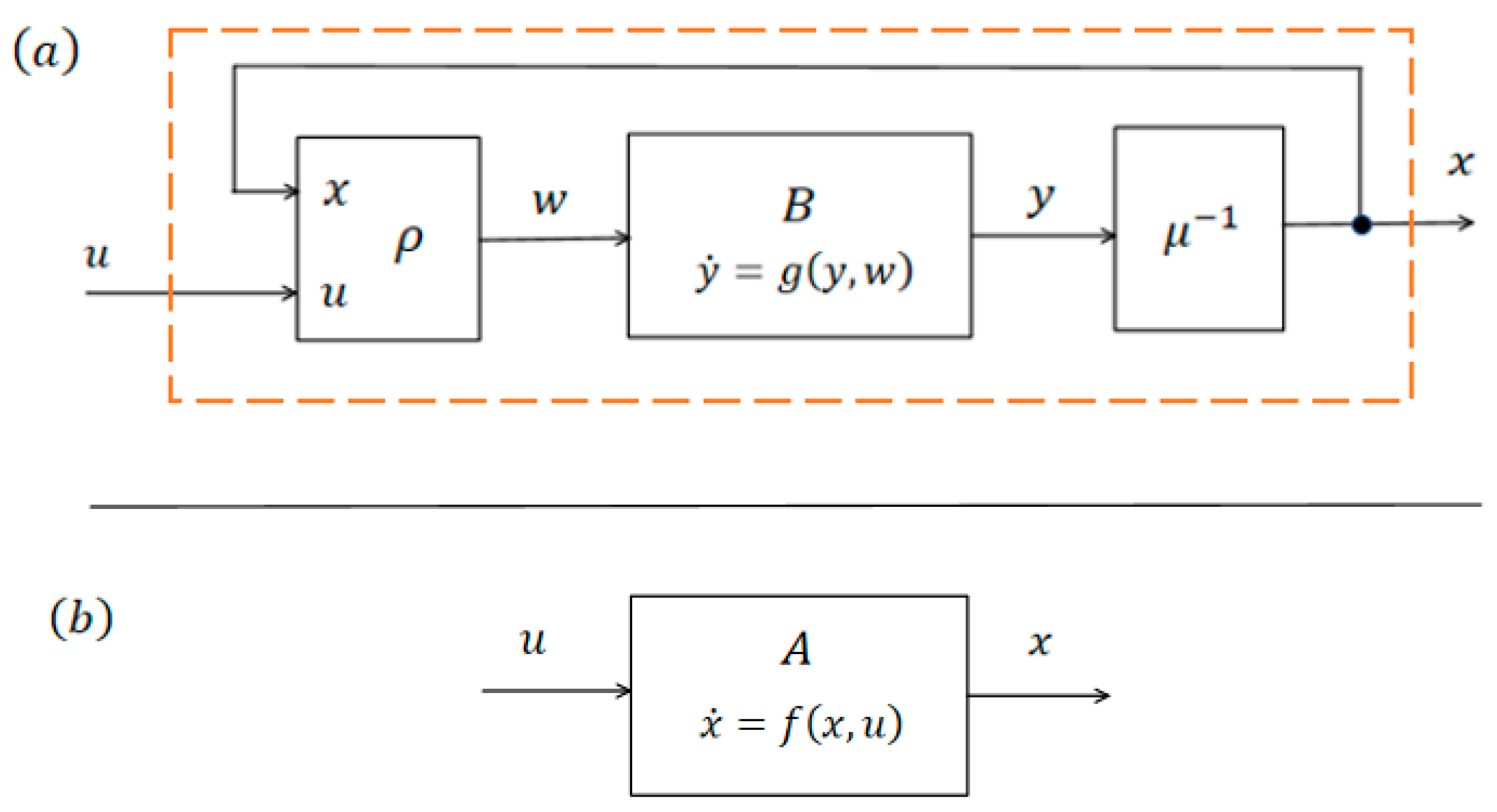

Figure 1. The block

with inputs

and

is a signal processor that physically implements a prescribed algebraic mapping

, while the block

represents the hardware implementation of the inverse mapping

.

Under certain conditions (see Note 1) imposed on the mappings

and

, which define the hardware-implementable transformation, as well as on the functions

and

, that specify the dynamics of control systems

and

, the block diagram inside the “black box” with input

and output

becomes equivalent (in the usual practical sense of the term) to control system

. More precisely, if the initial state of control system

related to the initial state

by the relation

, to to the system input

defined on the time interval

, is applied to the input of system

and to the input of the transformed system B, then the state trajectories of the outputs of these systems, denoted in

Figure 1 by

, will coincide at any moment of time

. Thus, the object inside the “black box” behaves exactly as the control object described by the mathematical model of system

, and we may say that such a hardware-implementable transformation converts control system

into control system

. Throughout the remainder of this work, when referring to the equivalence of control systems, we shall mean a precisely defined mathematical concept associated with the sets of trajectories of control systems. Recall that a trajectory of a control system defined by the state space

, the control space

and the dynamical Equation (1), is an application

, whose components satisfy the system’s dynamical equation.

To denote trajectories of control systems and their components, we will use the notation

, implying that the components of the mapping

and

, called respectively the state trajectory and the control-input trajectory, satisfy condition (3), where

is a finite or infinite time interval.

One may observe that when referring to the equivalence of two control systems, we are in fact speaking about the equivalence of the corresponding sets of trajectories generated by these systems.

Note 1. Under Conditions 1 and 2, the control systems and introduced in the example at the beginning of this section are equivalent.

Condition 1. For any point

the mapping

defined by formula (4), is a diffeomorphism. This requirement ensures the existence of a smooth, bijective correspondence between the admissible control inputs of the two systems.

Condition 2. For the functions

and

and for the mappings under consideration, relation (5) holds.

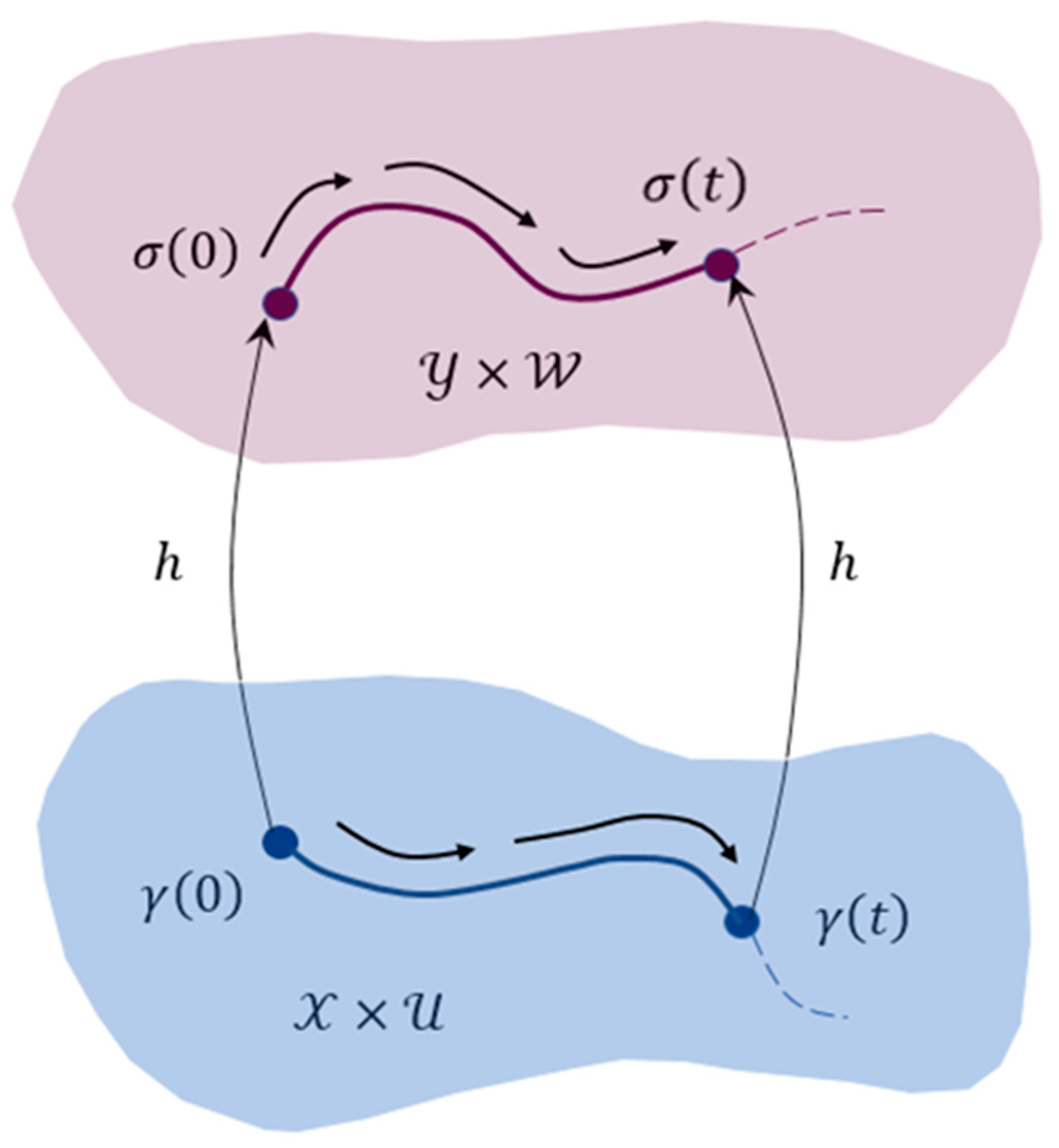

When these conditions are satisfied, the trajectories of control systems

and

are related by the diffeomorphic mapping

, defined by expression (6).

Moreover,

is an arbitrary trajectory of system

and

is the corresponding trajectory of system

, then for any moment of time the equalities given in

and

(see

Figure 2).

There exist several different approaches defining the notion of equivalence between control systems. In this article, we adopt the geometric approach first introduced in [

21], which is based on analogies between control systems and continuous dynamical systems. Both control systems and continuous dynamical systems can be viewed as geometric objects of the same type—so-called systems. A system is defined as a pair

, where

– is a smooth manifold and

is a tangent vector field on

. It is worth noting that the dynamical equation of system (1) corresponds to the infinite system of differential equations given in (7).

where

and

. Thus,

may be regarded as a tangent vector field defined on the infinite-dimensional manifold associated with

., and the control system under consideration may be viewed as the infinite-dimensional dynamical system corresponding to

. In [

21], an approach was first introduced in which control systems are defined as infinite-dimensional systems

, equipped with a Fréchet topology, and a definition was given for an endogenous transformation that relates equivalent control systems represented as such infinite-dimensional systems. Naturally, from a practical standpoint, the cases of greatest interest are those in which a nonlinear control system is equivalent to a linear one. A control system that is equivalent to a so-called trivial linear control system (the definition of this class of linear systems is given below) is referred to as a flat control system.

Definition 1. A linear control system with control space

and state space

, whose state vector

is of the form

, and whose dynamics are given by (8), where

is called a trivial linear control system.

We denote a trivial linear control system by

, where the integer index

represents the dimension of the control space, and the index

denotes the number of components of the trivial linear system

. In this article, we propose a linearisation procedure for the kinematic model of a differential-drive wheeled mobile robot, by which the robot’s kinematic model is transformed into the trivial control system

. The linear control system

admits a physical interpretation as the dynamics of a material point moving in the plane under the action of a planar force vector. Thus, the linearisation method described in this work reduces the control problem for a highly nonlinear plant to a simple linear control problem with an efficient solution. The proposed linearisation approach is carried out in two stages, which are presented in

Section 3 and

Section 4.

Section 5 provides a description of the trajectory-tracking control system for the linearised kinematic model of the DDWMR.

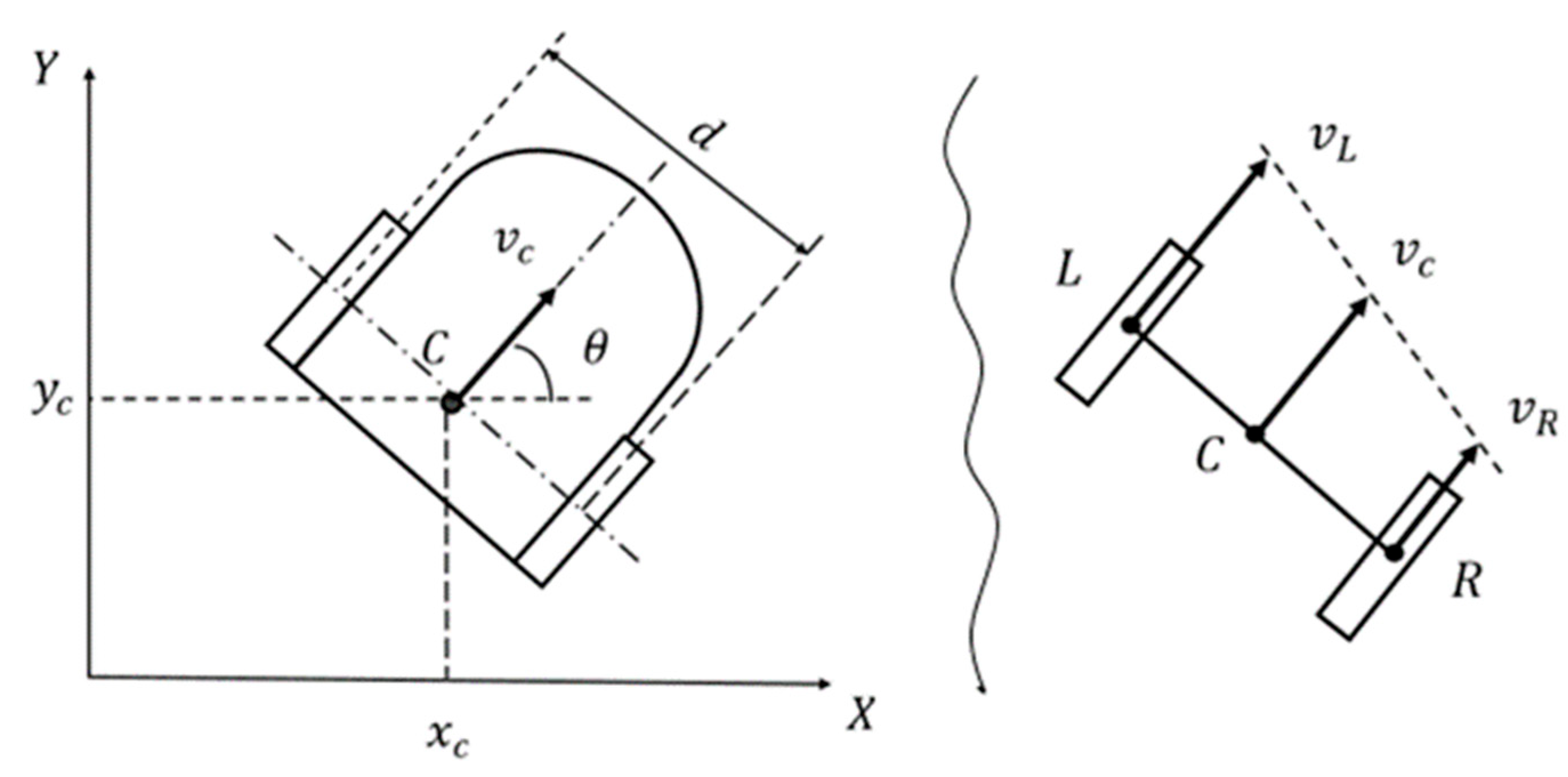

2.2. Kinematic Model of a Differential-Drive Wheeled Mobile Robot and Class I Transformations

Consider the kinematic model of a differential-drive wheeled mobile robot moving on a horizontal plane. As state variables fully describing the robot’s position and orientation, it is convenient to choose the coordinates

of point

in a fixed “world” Cartesian coordinate frame

together with the robot’s heading angle

(see

Figure 3). Let

denote the velocity vector of point

and let

and

denote the velocity vectors of the centers of the left wheel (point

) and the right wheel (point

), respectively.

We may regard points

and

as the endpoints of a rigid, thin rod (the imaginary “rear axle” of the robot), whose midpoint is point

. All three points therefore belong to the same rigid body—the robot chassis. As is well known [

34,

35], for the velocity vectors

and

of any two points

and

of a rigid body, the relation given in (9) holds, where

is the angular velocity vector of the body.

The robot’s angular velocity vector Ω is perpendicular to the floor plane. Accordingly, if we denote by

the unit vector normal to the plane, then the angular velocity vector may be written as

. In what follows, when referring to the angular velocity of the robot, we shall mean the scalar quantity

, whose sign determines the direction of rotation of the robot’s chassis in the horizontal plane. In the absence of lateral slip of the drive wheels, the vectors

and

are perpendicular to the axle

. As follows from Equation (9), applied to points

and

, the projections of

and

onto the axis

satisfy equality (10) at any moment of time.

Using Equation (10), it is straightforward to show that the vector

is parallel to the vectors

and

. Consequently, the velocity of point

can be written as

, where

is the unit vector aligned with the robot’s heading direction. Furthermore, from the general relation (9) applied to points

and

equality (11) follows.

Equations (10) and (11) together imply Equations (12).

The above statement regarding the direction of the vector

together with the fact that the time derivative of the heading angle,

is precisely the angular velocity of the robot’s chassis, leads to the system of differential Equations (13).

Equations (13) can be regarded as the dynamical equations of a control system with state space

and control space

, representing the simplest kinematic model of a differential-drive wheeled mobile robot. The state vector of this model,

, describing the robot’s position and orientation on the plane, is given by

, and the control vector

is

. In what follows, we refer to the above-defined control system as kinematic model

. This simplest DDWMR model is convenient for analytical manipulations; however, for computer simulations we employed a more detailed and realistic kinematic model, denoted as model

, which is described below. In the absence of longitudinal slip, the velocities of the wheel centers

and

satisfy relations (14), where

is the radius of the robot’s wheels, and

and

are the angular velocities of the right and left drive wheels, respectively (with

and

denoting the wheel shaft rotation angles, which may be measured using incremental rotary encoders).

Taking Formulas (14) and (12) into account, system (13) can be rewritten in the form given by (15).

We may regard system (15) as the representation of the coordinate-wise projections of the general dynamical equation of a control system

for the state vector

. The kinematic model of the robot, denoted as model

is transformed into the “advanced’’ robot model

by means of the control-signal transformation specified by formulas (16).

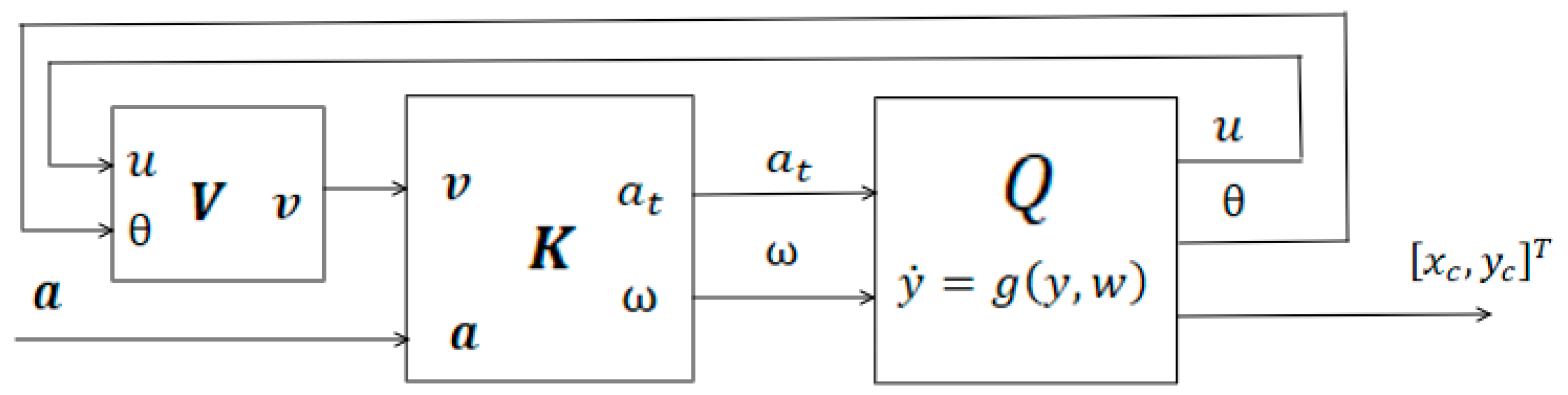

The general scheme of the transformation from system A to system B is shown in

Figure 4.

We transform the kinematic robot model A into a control system

with state space

, where

and control space

whose state vector has the form

, and whose dynamics are given by (17).

System Q is obtained by transforming the control signal

of the robot’s kinematic model (where

are aliases for

) into the control signal

of system Q (where

are aliases for

), analytically defined by equations (18).

This transformation is an example of a Class

control-system transformation, the definition of which is given below. Recall that a control system

,

is equivalent to the system

,

, since both systems are described by the same infinite-dimensional system

, where the tangent vector field is defined by

. Let the control signal of a control system be

-dimensional and written as

, and let

be a linear operator whose action on the signal

is defined by equation (19).

It is evident that the control system , is equivalent to the original control system , . We shall refer to such transformations of control systems as Class transformations.

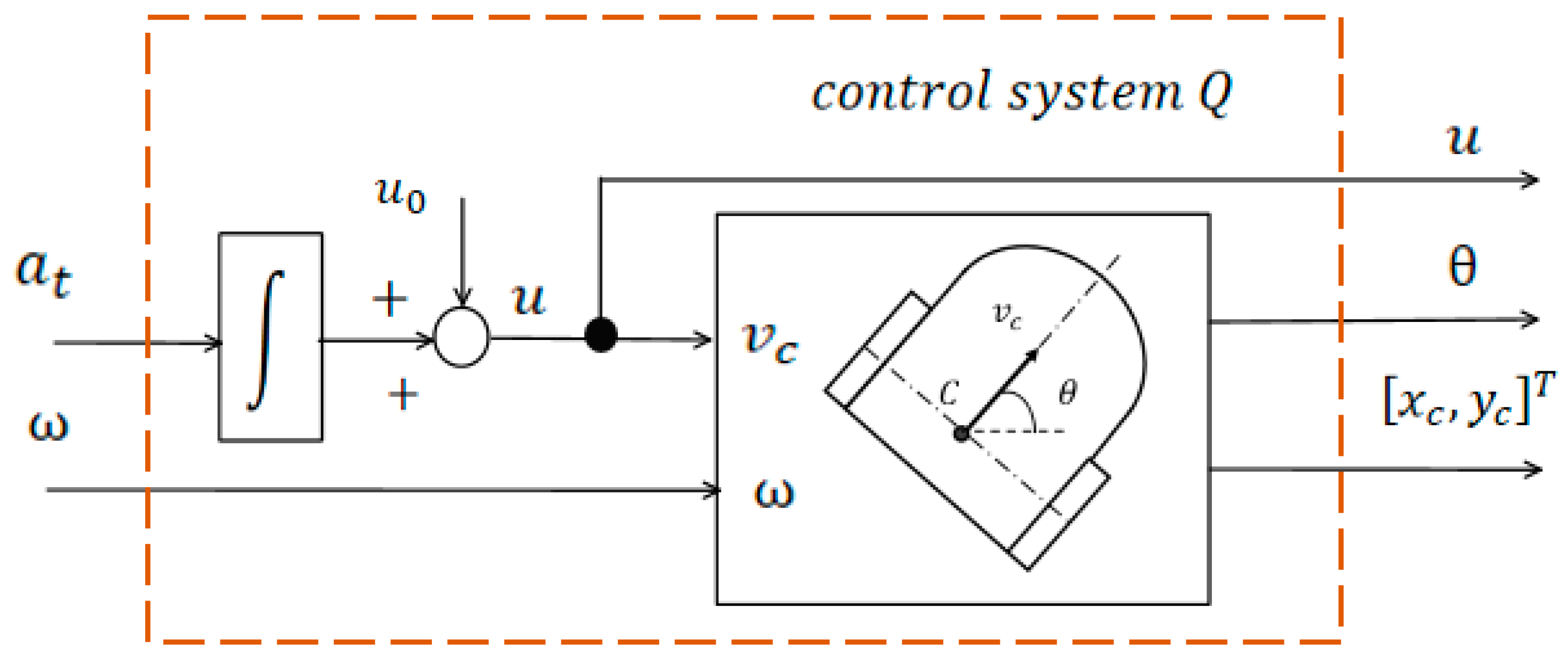

Figure 5.

Hardware-implementable scheme for transforming the DDWMR kinematic model A into the control system

Figure 5.

Hardware-implementable scheme for transforming the DDWMR kinematic model A into the control system

As will be shown in the next section, the control system can be interpreted as a kinematic control system governing the motion of a point in the plane. Accordingly, if we construct a physically implementable transformation that maps this system into the trivial control system , which describes force-based control of a material point moving in the plane, then we will be able to control the motion of the wheeled mobile robot in the same manner as controlling the motion of a point in the plane.

2.3. Linearisation of the DDWMR Kinematic Model

The problem of linearising the control system

, defined in the previous section, reduces—as will be shown below—to the linearisation of a simple control system on the smooth manifold

. Interestingly, the solution to this problem, presented below, leads directly to a hardware-implementable scheme for linearising the kinematic model of the wheeled mobile robot. First, observe that the kinematic equation

, which describes the motion of a point in the plane, may be viewed as the dynamical equation of the trivial linear control system

with state space

and control space

. We assume that the linear space

is equipped with an orthonormal basis

, б whose basis vectors correspond to the coordinate axes of the Cartesian frame

in which the point moves. Any nonzero vector

can be represented in the form (20).

where

,

and the mapping

is defined for any

by

, with

being the angle between the vector

and

. Clearly, for any nonzero vector there exist two possible representations of this form, given by expressions (21) and (22).

Formulas (21) and (22) can be viewed as two coordinate representations of mappings from the Euclidean plane

onto the smooth manifold

, which we denote by

and

. For the coordinates of a vector

expressed in the form un(θ), the identities (4) clearly hold. These identities may be interpreted as defining the mapping

, which serves as the inverse (on their respective domains of definition) to the mappings

and

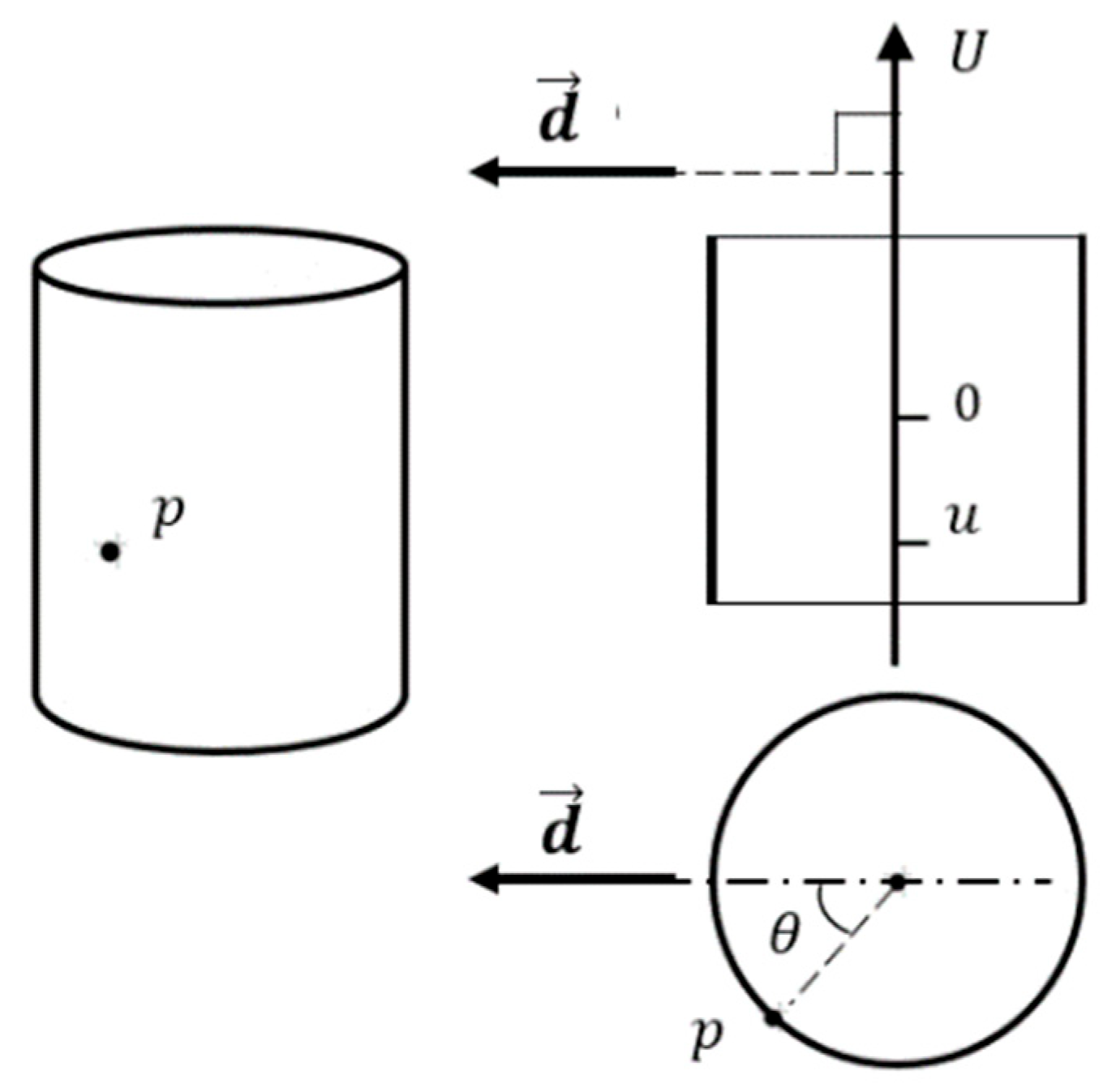

Note that the embedding of the smooth manifold

into the three-dimensional Euclidean space is represented by the lateral surface of an infinite cylinder, on which one can introduce coordinates

, as illustrated in

Figure 6. By expressing vectors of the Euclidean plane in the form (20), we effectively identify each nonzero vector with a point on the surface of this infinite cylinder. Consequently, any state trajectory

of system

(with the exception of the degenerate trajectory of a stationary point) corresponds to two curves μ+ (γ) and μ- (γ) on the cylinder surface. Let us define a control system

with state space

, control space

, and dynamics

As will be shown below, the geometric relationship between trajectories in the phase spaces

and

, determines a correspondence between the trajectories of systems

and

as a whole, thereby inducing a transformation from system

to system

. This transformation is precisely what we refer to as the linearisation of system

. Since system

constructed on top of system

the physically realisable hardware scheme that linearises system

simultaneously linearises system

. The smooth manifold

is not homeomorphic to the plane

, in particular, the cylinder cannot be continuously deformed into the Euclidean plane. For this reason alone, there cannot exist a one-to-one correspondence between the full trajectory sets of systems

and

. However, under the kinematic interpretation of system

it becomes clear that not all trajectories of system

are physically realisable. Therefore, it is meaningful to speak of an equivalence between the trajectory set of system

and the set of physically realisable trajectories of system

. To analyse the geometric relationship between the spaces

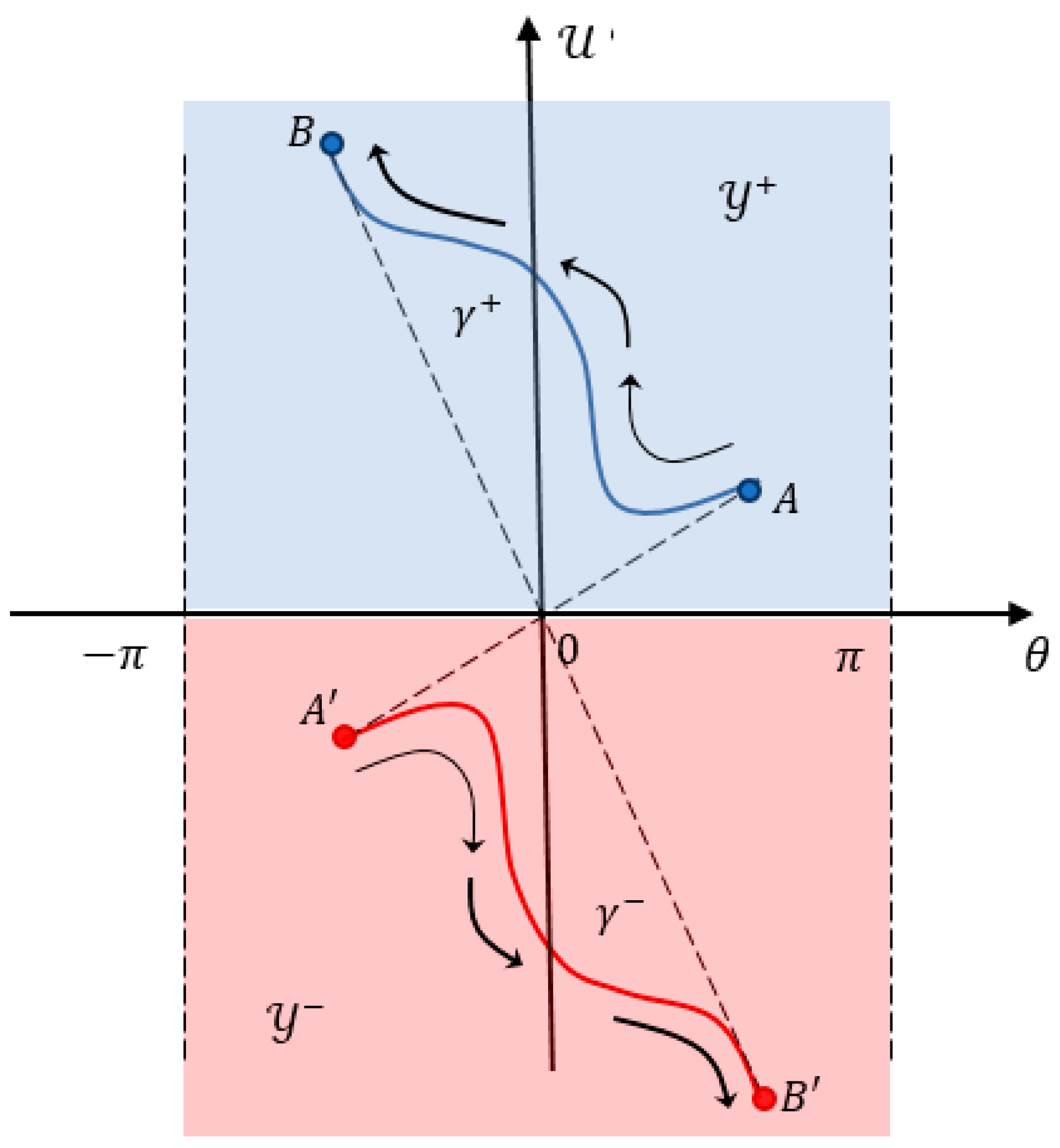

and

, we use the identification of vectors of

with points on the plane

endowed with the Cartesian frame

. Define the region

by the condition

The mapping

may then be visualised as the projection of an infinite cylindrical surface, cut by the plane

, perpendicular to the cylinder axis

, as shown in

Figure 7. Each of the regions

and

, corresponding respectively to the upper and lower halves of the cylinder, is mapped onto the plane with the origin

with coordinates

removed. The intersection of the cylinder with the plane, which forms a one-dimensional manifold

homeomorphic to

, is mapped to the single point

.

Thus, mapping

ends each point of the manifold

to a corresponding point on the Euclidean plane

. Let

denote the subset of the plane that is the image of regions

and

under mapping

. Then the mappings

and

are defined by equations (1) and (2) respectively. Mapping

is a diffeomorphism, and

, as

denotes the restriction of the mapping

to the region

. Similarly, the mappings

and

define a diffeomorphism between the regions

and

. Let

be a parametrically defined curve on the plane

, that does not pass through the point

. Let us denote

the image of the curve

under the diffeomorphism

, this image is a parametrically defined curve on the manifold

given by relation

. Likewise, let

, and as

denote the image

of the curve

under the mapping

. The images of the curves under the mapping π are curves on the plane Х. Moreover, these curves are related by a symmetry transformation defined by an automorphism

, introduced below. Specifically, for every

the following relations

, and

hold (see

Figure 7). The automorphism

is defined by formulas (24), which specify the correspondence between the coordinates

of an arbitrary point

and the coordinates

of its symmetric point

.

To establish the correspondence between the trajectories of control systems

and

, we represent the trajectory in the state space of system

in the form (25).

Differentiating both sides of equation (25) with respect to time yields Equation (26).

where

is the control-input trajectory generating the state-space trajectory

, and the function

is defined by Equation (27).

Obviously, for any

the vector

is a unit vector orthogonal to the unit vector n(θ) n(\theta)

. By taking the scalar product of both sides of equation (26) with the vector

we obtain equation (28).

where

is defined by (29).

The function

, defined by equation (31), computes the projection of a vector

onto the direction specified by a vector

. Accordingly,

represents the tangential component of the acceleration vector

, and equation (29) admits the physical interpretation of being the projection of the vector differential equation

onto the moving orthonormal basis on the plane

, generated by the vectors

and

.

Similarly, by taking the scalar product of both sides of equation (30)

with the vector

which can be conveniently rewritten in the form (31).

where the function

is defined by equation (32).

The function

computes the instantaneous angular velocity of rotation of the velocity vector

. It is straightforward to show that

can equivalently be defined by expression (33), and this alternative definition will be used throughout the remainder of the paper.

where the function

, defined by formulas (34), computes the instantaneous angular velocity

of the velocity vector of a point moving in the plane, based on its instantaneous velocity

and acceleration

.

The two equations (28) and (30) are equivalent to the differential Equation (35) for the trajectory

of system

in the phase space

.

where the function

is defined by equation (36).

For a control-input trajectory of system

prescribed on the time interval

differential equation (26) constitutes an ordinary differential equation for which the corresponding initial value problem

admits a unique solution for any initial condition

. This initial value represents the state-space component of the trajectory

of control system

, while the associated control-input trajectory

is determined by equation

. Moreover, the differential equation (35), parameterized by the control-input trajectory of system

, describes the operation of the hardware-implementable linearization scheme for the plant represented by the control system

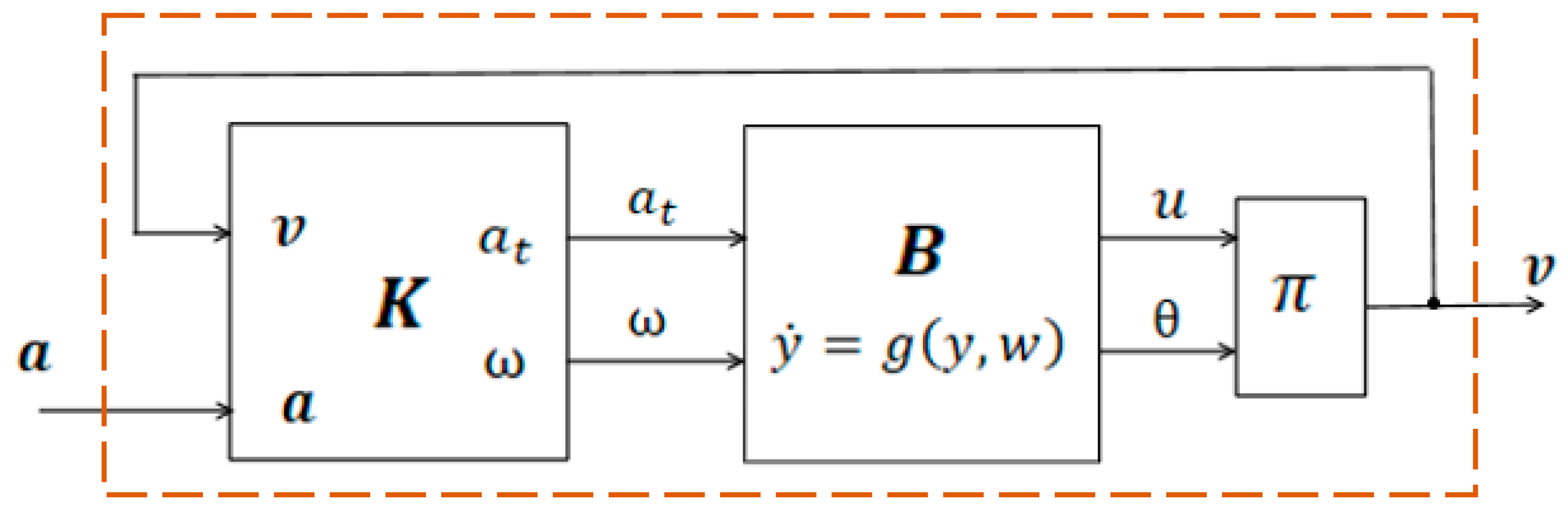

, shown in

Figure 8. The relationship between the output

of block and the input signals

and

are given by formula (30), while the functional dependence between the output signal

and

– is defined by Formula (34).

As noted above, the control system

can be viewed as a superstructure built on top of system

or more precisely, system

is structurally equivalent to the interconnection of system B with an integrator (see

Figure 9).

It follows that the hardware-implementable linearisation scheme developed for the control system

(see

Figure 10) is also applicable to the control system

. Since, after linearisation, system

becomes equivalent to an integrator, the control system

is a flat control system which flat output is

. It should be emphasised that not all trajectories of system

admit a physical interpretation as trajectories of a material point moving in the plane; only those trajectories for which a corresponding trajectory of the control system

, exists are physically realisable. Accordingly, the trajectories of system

(and their counterparts in system

) for which no corresponding trajectory of system

exists will be referred to as physically unrealizable trajectories.

The corresponding linearisation scheme for the simplest kinematic model of the robot

, as follows from the results presented in the previous section, is shown in

Figure 11.

The linearised kinematic model of the DDWMR is equivalent to the trivial linear control system , which can be interpreted as a force-control system governing the motion of a point in the plane. Consequently, the problem of controlling a nonlinear system is reduced to a simple linear trajectory-tracking problem with a clear physical interpretation. This linear problem admits a straightforward and efficient solution, which is described in the following section.

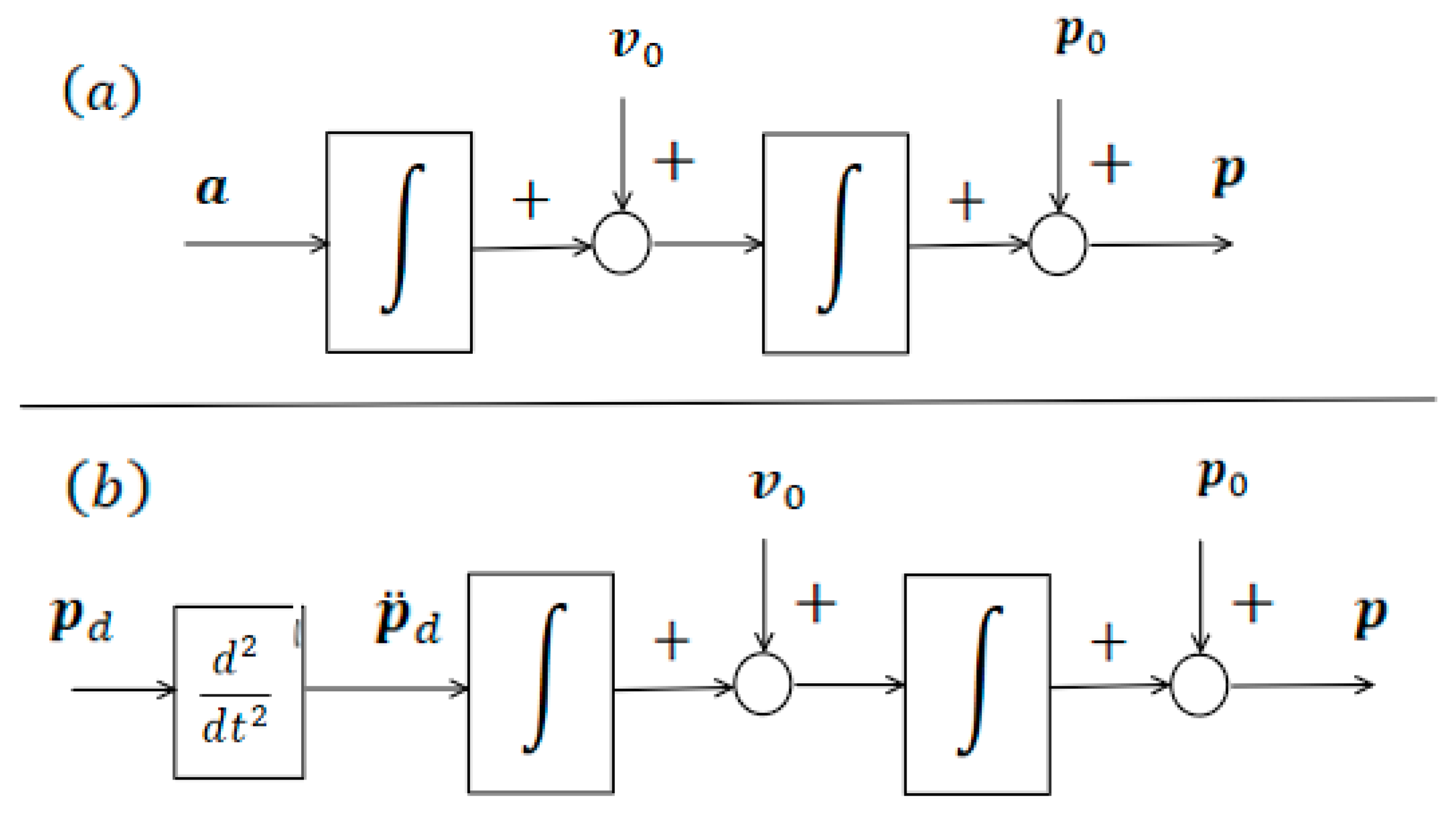

2.4. Trajectory-Tracking Control System for the Linearised Kinematic Model of the DDWMR

The linearised kinematic model of the DDWMR is equivalent to the trivial linear control system

Recall that this linear system can be interpreted as a force-control system governing the motion of a unit-mass point moving in the plane. Accordingly, the feedforward trajectory-tracking problem for the DDWMR may be formulated as follows: given a reference signal

, representing the desired time evolution of the point’s position in the plane, how can one transform it into a control signal

, that ensures that the linearised system (and therefore the original DDWMR) follows the prescribed trajectory? Since for a unit-mass point the relation

, holds at every instant of time, the answer becomes immediate. By setting

we ensure that, for any

along the trajectory, the actual acceleration

coincides with the prescribed reference signal

. Thus, the point mass follows the desired trajectory exactly, provided that the initial conditions match and no disturbances are present. Of course, the actual trajectory of the point

is determined not only by the control signal

, but also by the initial position

and the initial velocity

. The relationship between the actual trajectory and the reference signal of the trajectory-tracking control system is given by (37).

In the ideal case, when the initial state of the system exactly matches the initial state implied by the desired trajectory and when no disturbances are present, the actual trajectory coincides exactly with the desired trajectory defined by the reference signal . However, in the presence of any mismatch between the initial conditions of the plant and those associated with the reference trajectory, the tracking error will inevitably grow over time. Likewise, the purely feedforward trajectory-tracking scheme is highly sensitive to external disturbances and therefore unsuitable for practical use due to its inherent open-loop instability.

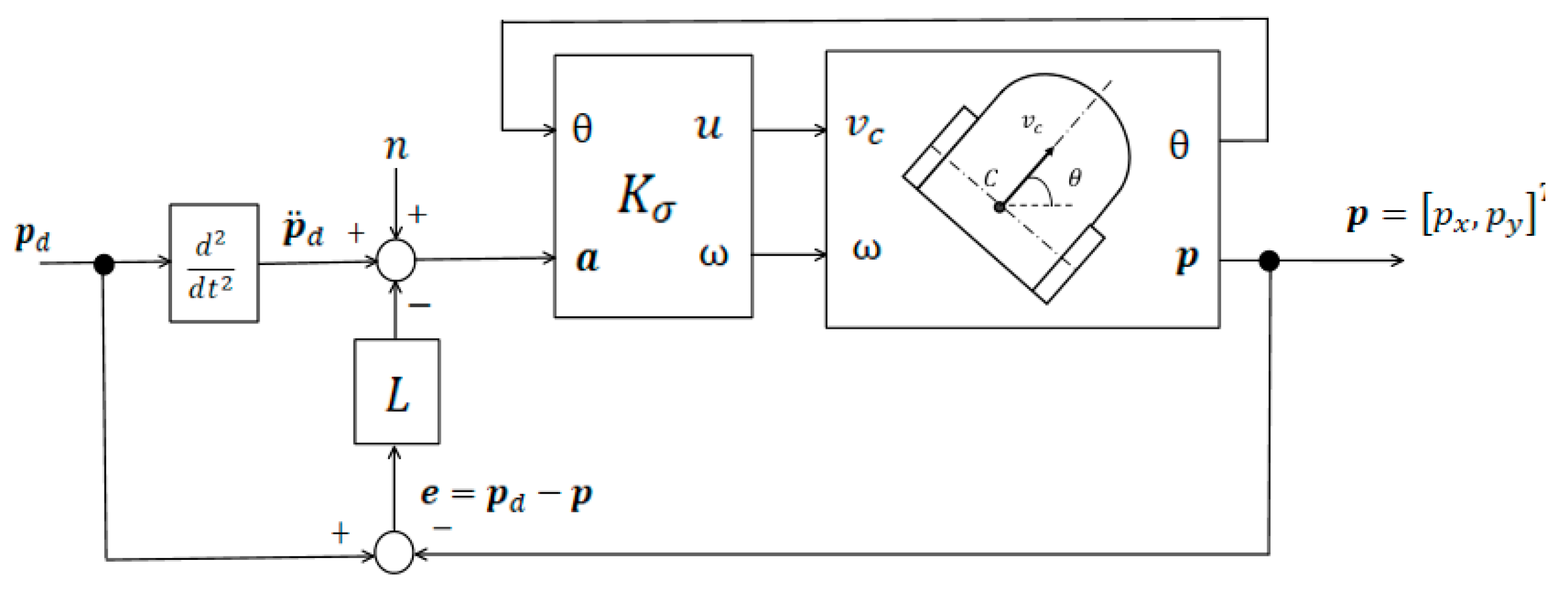

To overcome these limitations, the trajectory-tracking system can be modified by introducing a feedback loop with a linear controller that stabilises the closed-loop dynamics. The resulting structure ensures robustness with respect to initial-condition mismatches and perturbations.

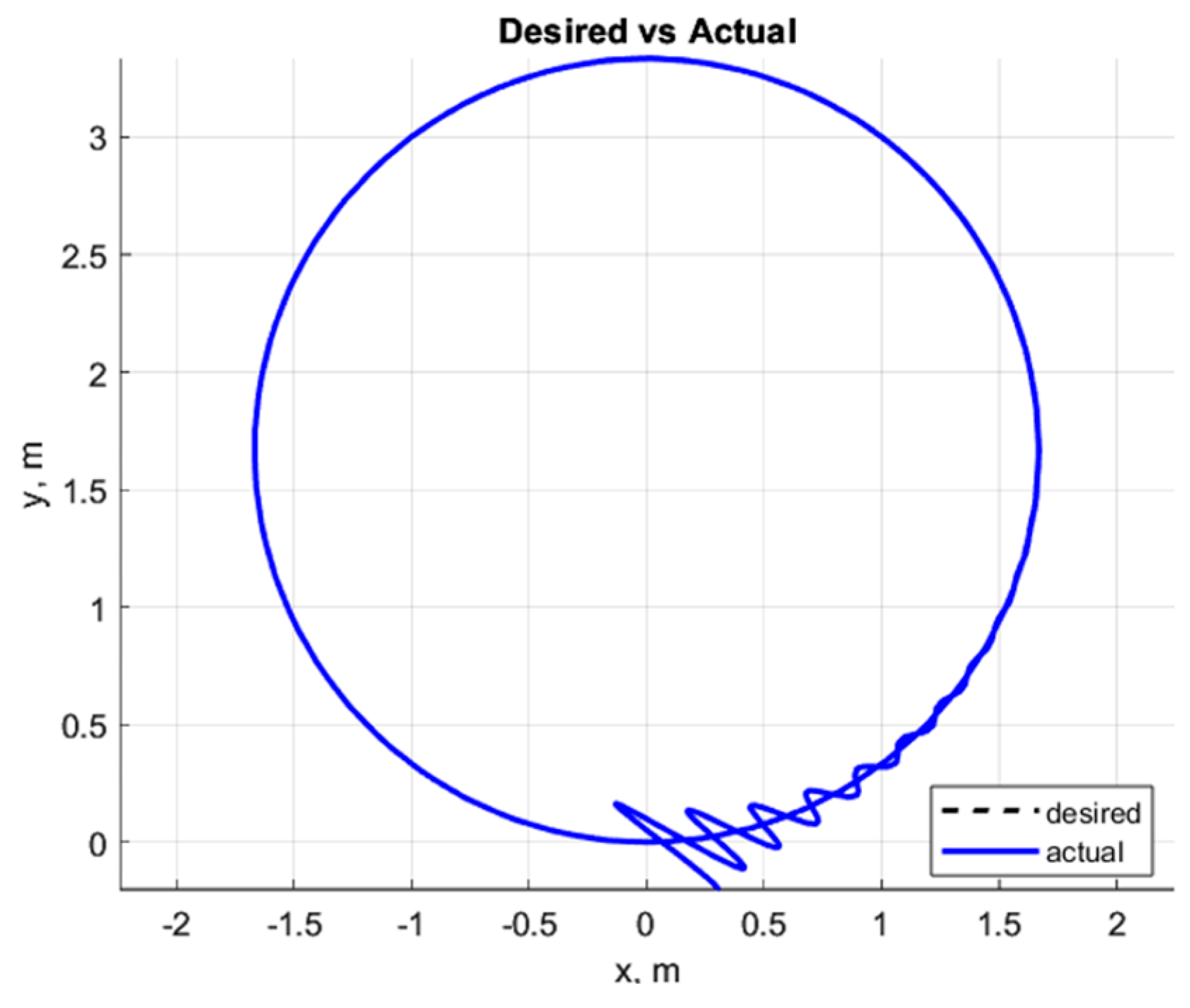

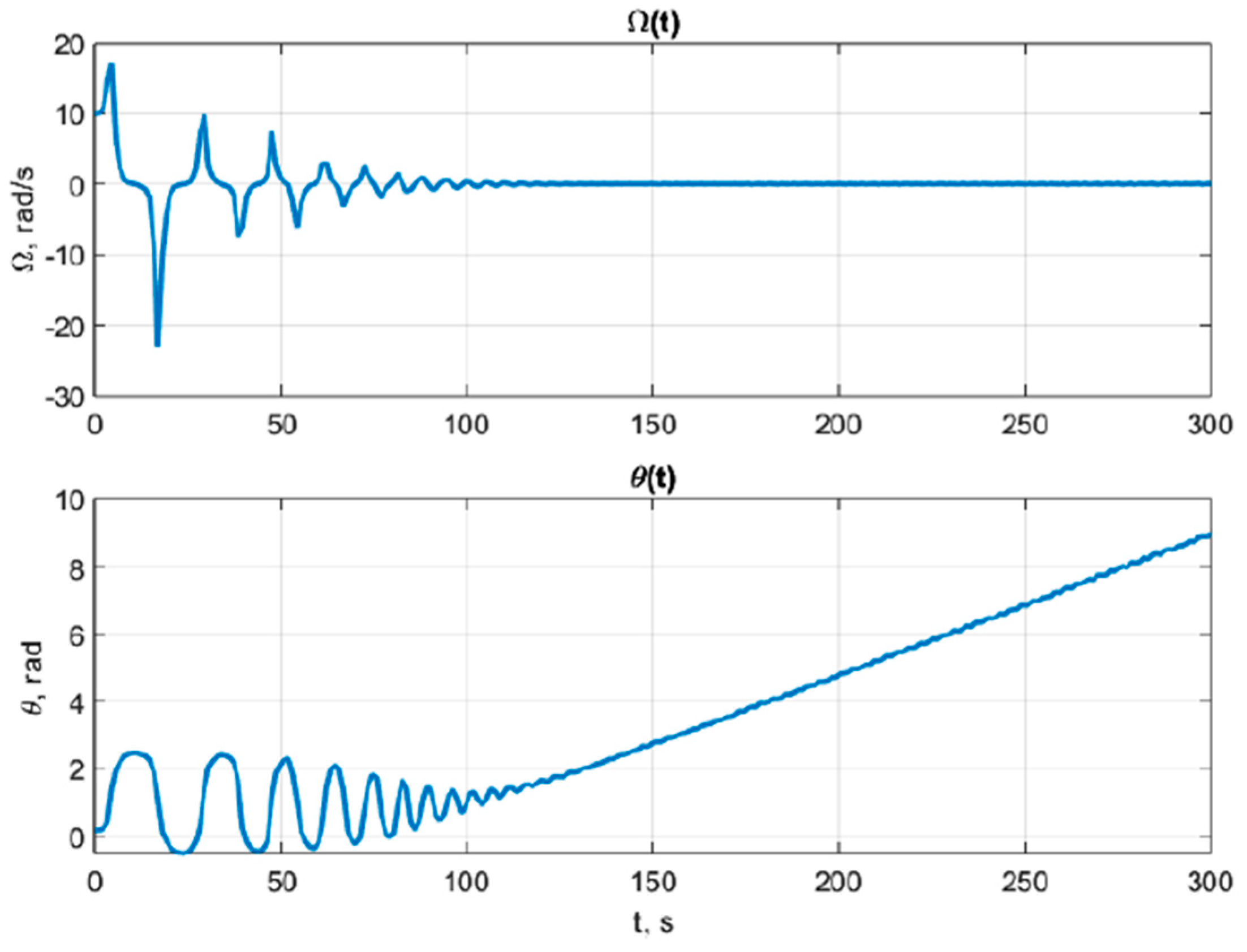

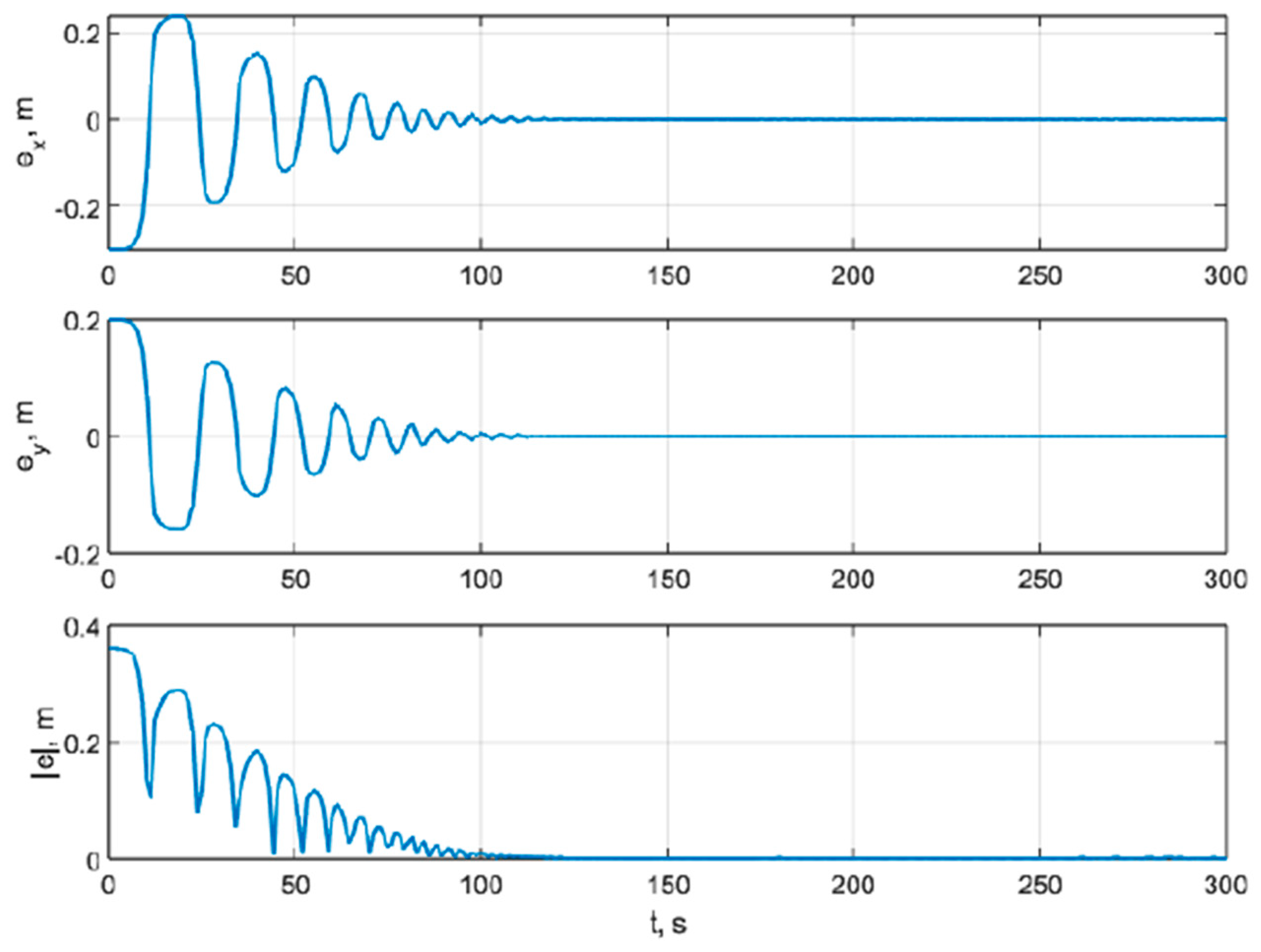

Figure 12 shows the block diagram of the modified trajectory-tracking system for the differential-drive mobile robot.

Disturbances are modelled by adding a noise term

to the sum of the signals applied to the input

of the linearising transformation block

The linear signal transformer

consists of two parallel, identical linear subsystems

and

. Consequently, the linear system equivalent to the modified trajectory-tracking scheme of the mobile robot can be viewed as the combination of two independent, identical one-dimensional linear subsystems.

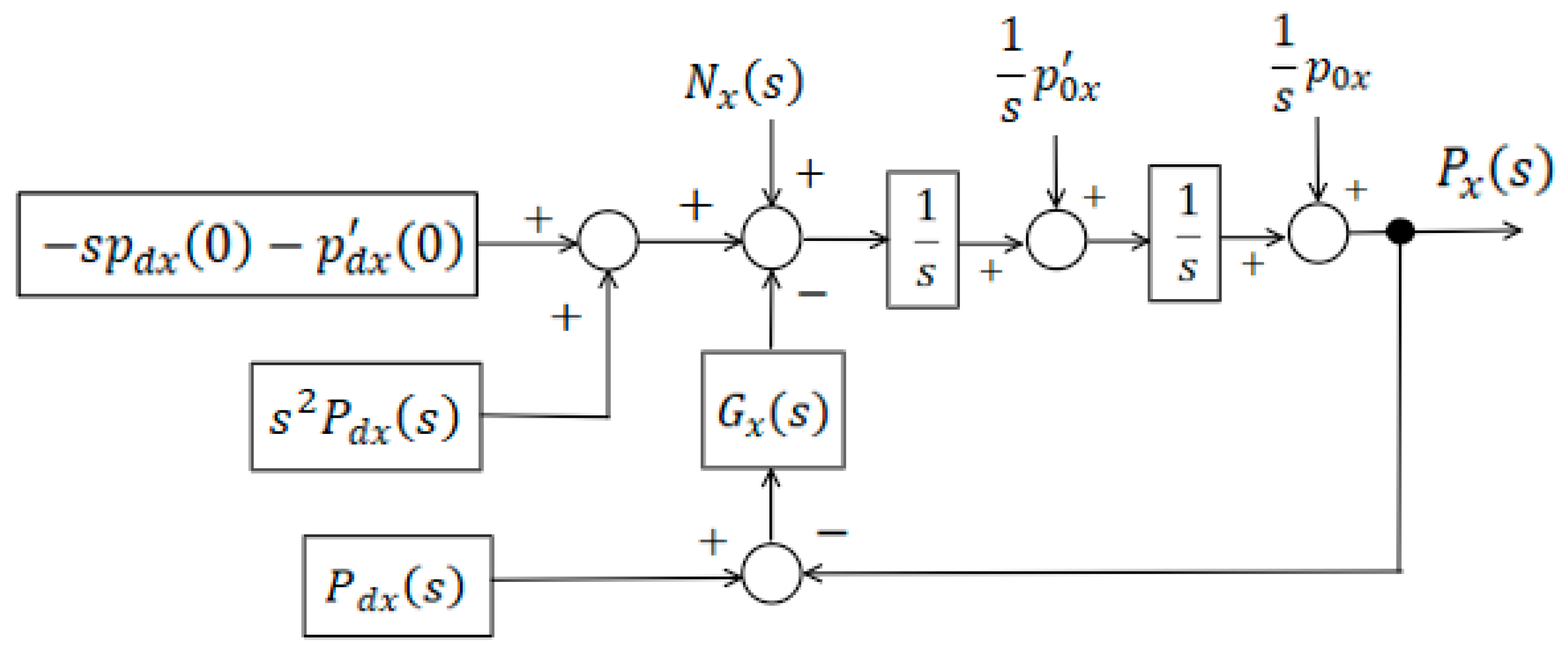

Figure 13 presents the block diagram of the

-channel.

-channel of the trajectory-tracking control system for the linearised kinematic model of the DDWMR.

To analyse the behaviour of such a one-dimensional linear system, representing each channel of the trajectory-tracking scheme, it is convenient to employ the Laplace transform. In this framework, constant functions of the form

are represented as

, where

denotes the Heaviside step function. We denote by

the transfer function describing the linear signal transformers

and

. In addition, we introduce the notations

and

. Taking into account that

and

we obtain, for the Laplace-domain representations of the signals, the block structure describing the behaviour of each one-dimensional channel of the robot’s trajectory-tracking system, as shown in

Figure 14.

–channel of the trajectory-tracking control system for the differential-drive mobile robot.

The analysis of the one–dimensional linear trajectory–tracking subsystem in the Laplace domain leads to expression (38), which describes the relationship between the Laplace transform

of the system output component

and the transform

of the corresponding reference component.

where the complex-variable function

is defined by expression (39).

Naturally, the function

can be interpreted as the Laplace transform of the time-domain function

. As follows from the definition of

in (39), the function

is the solution of the initial value problem for the differential equation (40) with the initial conditions given in (41).

In the differential equation (40), the symbol

denotes the linear operator representing the action of the linear signal transformer defined by the transfer function

. Term

in Equation (38) represents the Laplace transform of the disturbance signal

, passed through a linear filter described by the transfer function

, defined in expression (42).

Thus, the output of the trajectory-tracking subsystem

is a linear superposition of the three functions of the form (42).

As follows from a straightforward analysis of expression (43), the stability of the trajectory-tracking system is guaranteed provided that the linear signal transformers and satisfy Criterion 1, formulated below. It is also evident that, in order to minimise the influence of disturbances represented by the term the superposition (43)—the transfer function of the identical signal transformers and must satisfy Criterion 2.

Criterion 1. The linear operator

, corresponding to the identical linear signal transformers

and

must stabilise the differential Equation (44).

Criterion 2. The transfer function

of the linear signal transformers

and

must satisfy the disturbance-rejection condition (45).

As a result, the two linearisation criteria, achievability of the required dynamic form and satisfaction of the disturbance-rejection condition, ensure the correctness of the constructed transformation and form the foundation for designing the outer trajectory-tracking control loop, to be presented in the next section.