Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

14 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: Computational Imperatives for Neuromuscular Diseases

- Computational tools for diagnosis that overcome heterogeneous presentations, integrate multimodal data, resolve phenotypic overlap, and shorten the time to accurate diagnosis.

- Computational tools for disease progression and outcome that measure disease progression more precisely, automate these measurements, and better model clinical outcomes.

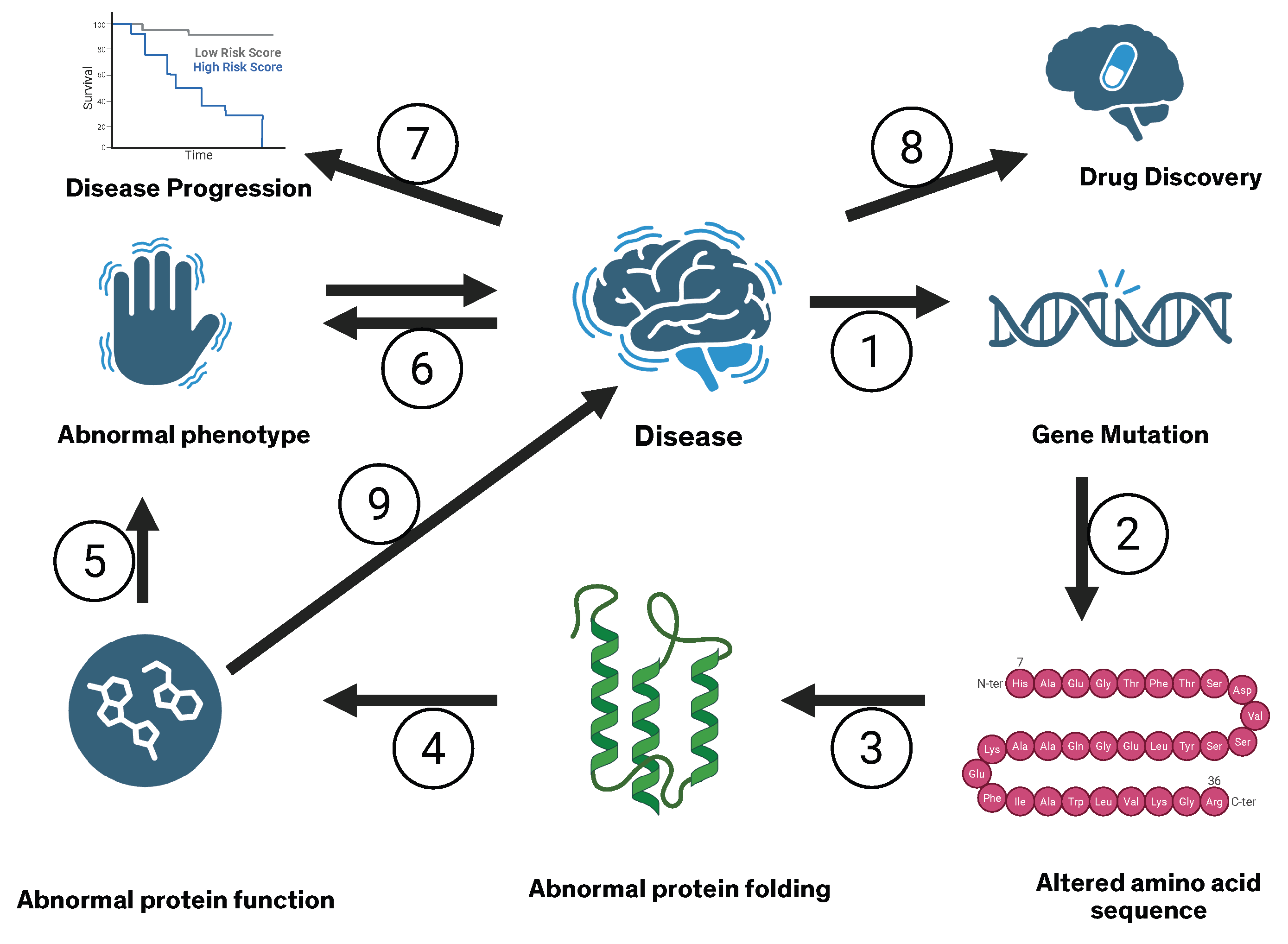

- Computational tools for therapeutics that improve patient stratification for clinical trials, connect gene mutations to protein structure and function, predict phenotype from altered protein structure and function, reduce failure rates in clinical trials, and critically assist in drug discovery and design.

2. Methods

3. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Diagnosis of Rare Neuromuscular Diseases

3.1. Advanced Imaging and Radiomics

3.2. Electrophysiology and Signal-Based Diagnosis

3.3. Integration of Multimodal Clinical Data

3.4. Phenotype-Driven and Database-Supported Diagnosis

3.5. Limitations and Gaps in Applying artificial intelligence to Diagnosis of Neuromuscular Diseases

4. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Disease Progression and Outcome Prediction

4.1. Prognostic Modeling in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Rare Meuromuscular diseases

4.2. Digital Biomarkers and Remote Monitoring

4.3. Subtyping, Deep Phenotyping, and Latent Trajectories

4.4. Methodological and Practical Challenges

5. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Therapeutics in Neuromuscular Diseases

5.1. Target Discovery and Drug Repurposing

5.2. Multi-Omics Integration and Mechanistic Modeling

5.3. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Gene and RNA Therapies

5.4. Clinical Trial Design and Patient Stratification

5.5. Ethical, Regulatory, and Practical Considerations

6. Discussion: Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

- Multicenter, interoperable datasets that capture the breadth of rare neuromuscular disease phenotypes.

- Harmonized acquisition and annotation standards for imaging, electrophysiology, and digital signals.

- Extensive and harmonized use of standardized terminologies with machine-readable codes across the biomedical literature and electronic health records (e.g., Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, Human Phenotype Ontology, Orphadata, Gene Ontology).

- Prospective, clinician-in-the-loop deployments of diagnostic and prognostic artificial intelligence tools.

- Integration of biological and clinical modeling across scales, from molecule to motor unit to patient.

- Ethical frameworks that address data governance, algorithmic bias, and equitable access to artificial intelligence-enabled therapies.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jankovic, J.; Mazziotta, J.C.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Newman, N.J. (Eds.) Bradley and Daroff’s Neurology in Clinical Practice, 8 ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2022; p. 2400. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, Z. Development of a deep learning model for automated diagnosis of neuromuscular diseases using ultrasound imaging. Frontiers in Neurology 2025, 16, 1640428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, R. Myasthenia gravis: The changing treatment landscape in the era of molecular therapies. Nature Reviews Neurology 2024, 20, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabally, Y.A. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: Current therapeutic approaches and future outlooks. ImmunoTargets and Therapy 2024, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, G.I.; Hanson, J.E.; Silvestri, N.J. Myasthenia gravis: The evolving therapeutic landscape. eNeurologicalSci 2024, 37, 100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripellino, P.; Fleetwood, T.; Cantello, R.; Comi, C. Treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: From molecular bases to practical considerations. Autoimmune diseases 2014, 2014, 201657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, E.L.; Callaghan, B.C.; Pop-Busui, R.; Zochodne, D.W.; Wright, D.E.; Bennett, D.L.; Bril, V.; Russell, J.W.; Viswanathan, V. Diabetic neuropathy. Nature reviews Disease primers 2019, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.M.; Harris-Adamson, C.; Rempel, D.; Gerr, F.; Hegmann, K.; Silverstein, B.; Burt, S.; Garg, A.; Kapellusch, J.; Merlino, L.; et al. Prevalence and incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in US working populations: Pooled analysis of six prospective studies. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health 2013, 39, 495. [Google Scholar]

- Rath, A.; Olry, A.; Dhombres, F.; Brandt, M.M.; Urbero, B.; Ayme, S. Representation of rare diseases in health information systems: The Orphanet approach to serve a wide range of end users. Human mutation 2012, 33, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amberger, J.; Bocchini, C.; Hamosh, A. A new face and new challenges for Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM®). Human mutation 2011, 32, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, U.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Reddy, H.N.; Anil, A.; Iyer, G.R.; Mishra, R.K.; et al. NMPhenogen: A comprehensive database for genotype-phenotype correlation in neuromuscular genetic disorders. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2025, 19, 1696899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.N. Deep phenotyping for precision medicine. Human mutation 2012, 33, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Benson, M.; Brown, G.; Chao, C.; Chitipiralla, S.; Gu, B.; Hart, J.; Hoffman, D.; Hoover, J.; et al. ClinVar: Public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic acids research 2016, 44, D862–D868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenn, M.; Wagner, M.; Zulehner, G.; Weng, R.; Jäger, F.; Keritam, O.; Sener, M.; Brücke, C.; Milenkovic, I.; Langer, A.; et al. Next-generation sequencing and comprehensive data reassessment in 263 adult patients with neuromuscular disorders: Insights into the gray zone of molecular diagnoses. Journal of Neurology 2023, 271, 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.; Chin, H.; Chin, A.; Goh, D. Using gene panels in the diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders: A mini-review. Frontiers in Neurology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.; Tian, C.; He, H.; Ulm, E.; Collins Ruff, K.; B. Nagaraj, C. An evaluation of clinical presentation and genetic testing approaches for patients with neuromuscular disorders. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 2023, 191, 2679–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeros-Fernández, M.C. Artificial intelligence applications in the diagnosis of neuromuscular diseases: A narrative review. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decherchi, S.; Pedrini, E.; Mordenti, M.; Cavalli, A.; Sangiorgi, L. Opportunities and challenges for machine learning in rare diseases. Frontiers in medicine 2021, 8, 747612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsumoto, H.; Brooks, B.R.; Silani, V. Clinical trials in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Why so many negative trials and how can trials be improved? The Lancet Neurology 2014, 13, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, D.; Mansfield, C.; Moussy, A.; Hermine, O. ALS clinical trials review: 20 years of failure. Are we any closer to registering a new treatment? Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcia, P.; Lunetta, C.; Vourc’h, P.; Pradat, P.F.; Blasco, H. Time for optimism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. European Journal of Neurology 2023, 30, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubuisson, N.; Claeys, K.; Schoser, B. Implementing new technologies for neuromuscular disorders. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, S.; Shukla, A. Review on Classification of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Using Ensemble Classifiers. Engineering Proceedings 2025, 82, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scodellaro, R.; Zschüntzsch, J.; Hell, A.K.; Alves, F. A first explainable-AI-based workflow integrating forward-forward and backpropagation-trained networks of label-free multiphoton microscopy images to assess human biopsies of rare neuromuscular disease. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2025, 265, 108733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeros-Fernández, M.C. Artificial intelligence applications in the diagnosis of neuromuscular diseases: A narrative review. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y.; He, W.; Luo, Y.; Wu, Z.; Fang, D.; Sun, L.; Zeng, H.; et al. Machine learning-based radiomics using MRI to differentiate early-stage Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy in children. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2025, 26, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.A.; Morren, J.A. The role of artificial intelligence in electrodiagnostic and neuromuscular medicine: Current state and future directions. Muscle & nerve 2024, 69, 260–272. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Castillo, J.R.; Lopez-Lopez, C.O.; Padilla-Castaneda, M.A. Neuromuscular disorders detection through time-frequency analysis and classification of multi-muscular EMG signals using Hilbert-Huang transform. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 71, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, G.; Nastasi, L.; Motan, D.; Deeb, J. Evaluating paediatric peripheral neuromuscular disorders using deep neural networks on electrodiagnostic data. Clinical Neurophysiology Practice 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hier, D.B.; Munzir, S.I.; Stahlfeld, A.; Obafemi-Ajayi, T.; Carrithers, M.D. High-Throughput Phenotyping of Clinical Text Using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI); IEEE, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi, S.; Hier, D.B.; Wunsch II, D.C. Enhanced neurologic concept recognition using a named entity recognition model based on transformers. Frontiers in Digital Health 2022, 4, 1065581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hier, D.B.; Carrithers, M.A.; Platt, S.K.; Nguyen, A.; Giannopoulos, I.; Obafemi-Ajayi, T. Preprocessing of Physician Notes by LLMs Improves Clinical Concept Extraction Without Information Loss. Information 2025, 16, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzir, S.I.; Hier, D.B.; Oommen, C.; Carrithers, M.D. A large language model outperforms other computational approaches to the high-throughput phenotyping of physician notes. In Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings; 2025; Vol. 2024, p. 838. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Santiago, E.; Claros, M.G.; Yahyaoui, R.; de Diego-Otero, Y.; Calvo, R.; Hoenicka, J.; Palau, F.; Ranea, J.A.; Perkins, J.R. Decoding neuromuscular disorders using phenotypic clusters obtained from co-occurrence networks. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021, 8, 635074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.; Sealfon, R.S.; Theesfeld, C.L.; Troyanskaya, O.G. Decoding disease: From genomes to networks to phenotypes. Nature Reviews Genetics 2021, 22, 774–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hier, D.B.; Yelugam, R.; Carrithers, M.D.; Wunsch III, D.C. The visualization of Orphadata neurology phenotypes. Frontiers in Digital Health 2023, 5, 1064936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Havrilla, J.M.; Fang, L.; Chen, Y.; Peng, J.; Liu, C.; Wu, C.; Sarmady, M.; Botas, P.; Isla, J.; et al. Phen2Gene: Rapid phenotype-driven gene prioritization for rare diseases. NAR genomics and Bioinformatics 2020, 2, lqaa032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanaolivu, R.; Oliver, G.; Jenkinson, G.; Blake, E.; Chen, W.; Chia, N.; Klee, E.W.; Wang, C. A clinical knowledge graph-based framework to prioritize candidate genes for facilitating diagnosis of Mendelian diseases and rare genetic conditions. BMC bioinformatics 2025, 26, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuredini, A.; Savarese, M.; Santorelli, F.M.; Tupler, R.G. Empowering clinicians with artificial intelligence in hereditary neuromuscular disorders: Training the Next Generation through the CoMPaSS-NMD Young Investigator Training program and the CoMPaSS-NMD Autumn School Workshop Report. Acta Myologica 2025, 44, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, J.; Lehne, M.; Schepers, J.; Prasser, F.; Thun, S. The use of machine learning in rare diseases: A scoping review. Orphanet journal of rare diseases 2020, 15, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Taroni, J.N.; Allaway, R.J.; Prasad, D.V.; Guinney, J.; Greene, C. Machine learning in rare disease. Nature Methods 2023, 20, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faviez, C.; Chen, X.; Garcelon, N.; Neuraz, A.; Knebelmann, B.; Salomon, R.; Lyonnet, S.; Saunier, S.; Burgun, A. Diagnosis support systems for rare diseases: A scoping review. Orphanet journal of rare diseases 2020, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groza, T.; Köhler, S.; Doelken, S.; Collier, N.; Oellrich, A.; Smedley, D.; Couto, F.M.; Baynam, G.; Zankl, A.; Robinson, P.N. Automatic concept recognition using the Human Phenotype Ontology reference and test suite corpora. Database: The Journal of Biological Databases and Curation 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groza, T.; Gration, D.; Baynam, G.; Robinson, P.N. FastHPOCR: Pragmatic, fast, and accurate concept recognition using the human phenotype ontology. Bioinformatics 2024, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Wang, L.; Liu, H. Phenotypic Analysis of Clinical Narratives Using Human Phenotype Ontology. Studies in health technology and informatics 2020, 245, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Kury, F.; Li, Z.; Ta, C.N.; Wang, K.; Weng, C. Doc2Hpo: A web application for efficient and accurate HPO concept curation. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, S.; Doelken, S.; Mungall, C.; Bauer, S.; Firth, H.; Bailleul-Forestier, I.; Black, G.; Brown, D.L.; Brudno, M.; Campbell, J.; et al. The Human Phenotype Ontology project: Linking molecular biology and disease through phenotype data. Nucleic acids research 2014, 42 Database issue, D966–D974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, L.; Yao, S.; Huang, X.; Mamitsuka, H.; Zhu, S. HPOAnnotator: Improving large-scale prediction of HPO annotations by low-rank approximation with HPO semantic similarities and multiple PPI networks. BMC Medical Genomics 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Hussain, L.; Liu, Z.; Yan, X.; Awwad, F.A.; Butt, F.M.; Salaria, U.A.; Ismail, E.A. Optimizing deep learning models to combat amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) disease progression. Digital health 2025, 11, 20552076251349719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blemker, S.S.; Riem, L.; DuCharme, O.; Pinette, M.; Costanzo, K.E.; Weatherley, E.; Statland, J.; Tapscott, S.J.; Wang, L.H.; Shaw, D.W.; et al. Multi-scale machine learning model predicts muscle and functional disease progression. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 25339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.S.; Kaplan, B.; Jie, T. A primer on machine learning. Transplantation 2021, 105, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, A.; Latella, D.; Bonanno, M.; Quartarone, A.; Mojdehdehbaher, S.; Celesti, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Towards transforming neurorehabilitation: The impact of artificial intelligence on diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belić, M.; Bobić, V.; Badža, M.; Šolaja, N.; Đurić-Jovičić, M.; Kostić, V.S. Artificial intelligence for assisting diagnostics and assessment of Parkinson’s disease—A review. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 2019, 184, 105442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youn, B.Y.; Ko, Y.; Moon, S.; Lee, J.; Ko, S.G.; Kim, J.Y. Digital biomarkers for neuromuscular disorders: A systematic scoping review. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, M.; Kothare, H.; Ramanarayanan, V. Multimodal speech biomarkers for remote monitoring of ALS disease progression. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 180, 108949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbioso, R.; Spisto, M.; Verde, L.; Iuzzolino, V.V.; Senerchia, G.; Salvatore, E.; De Pietro, G.; De Falco, I.; Sannino, G. Voice signals database of ALS patients with different dysarthria severity and healthy controls. Scientific Data 2024, 11, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolani, S.; Brusa, C.; Rolle, E.; Monforte, M.; De Arcangelis, V.; Ricci, E.; Mongini, T.E.; Tasca, G. Technology outcome measures in neuromuscular disorders: A systematic review. European Journal of Neurology 2022, 29, 1266–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabnichki, P.; Pang, T.Y. Wearable Sensors and Motion Analysis for Neurological Patient Support. Biosensors 2024, 14, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.S.; Patel, S.; Premasiri, A.; Vieira, F. At-home wearables and machine learning sensitively capture disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature communications 2023, 14, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Unnik, J.W.; Meyjes, M.; van Mantgem, M.R.J.; van den Berg, L.H.; van Eijk, R.P. Remote monitoring of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using wearable sensors detects differences in disease progression and survival: A prospective cohort study. EBioMedicine 2024, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izuka, S.; Sen, P.; Komai, T.; Fujio, K.; Knitza, J.; Gupta, L. Digital approaches in myositis. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Torri, F.; Vadi, G.; Meli, A.; Loprieno, S.; Schirinzi, E.; Lopriore, P.; Ricci, G.; Siciliano, G.; Mancuso, M. The use of digital tools in rare neurological diseases towards a new care model: A narrative review. Neurological Sciences 2024, 45, 4657–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmailova, E.S.; Demanuele, C.; McCarthy, M. Digital health technology derived measures: Biomarkers or clinical outcome assessments? Clinical and Translational Science 2023, 16, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Shukla, A. Review on Classification of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Using Ensemble Classifiers. Engineering Proceedings 2025, 82, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing Yeo, C.J.; Ramasamy, S.; Joel Leong, F.; Nag, S.; Simmons, Z. A neuromuscular clinician’s primer on machine learning. Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 2025, 22143602251329240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoenathmisier, K.D.; Gardarsdottir, H.; Mol, P.G.; Pasmooij, A.M. Insights from the European Medicines Agency on digital health technology derived endpoints. Drug Discovery Today 2025, 104388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J.P.; Izmailova, E.S.; Clement, A.; Hoffmann, S.; Leptak, C.; Menetski, J.P.; Wagner, J.A. Regulatory pathways for qualification and acceptance of digital health technology-derived clinical trial endpoints: Considerations for sponsors. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2025, 117, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Xu, J.; Dutta, R.; Trapp, B.; Pieper, A.A.; Cheng, F. Network medicine informed multiomics integration identifies drug targets and repurposable medicines for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. NPJ Systems Biology and Applications 2024, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pun, F.W.; Liu, B.H.M.; Long, X.; Leung, H.W.; Leung, G.H.D.; Mewborne, Q.T.; Gao, J.; Shneyderman, A.; Ozerov, I.V.; Wang, J.; et al. Identification of therapeutic targets for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using PandaOmics–an AI-enabled biological target discovery platform. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2022, 14, 914017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunildutt, N.; Ahmed, F.; Chethikkattuveli Salih, A.R.; Lim, J.H.; Choi, K.H. Integrating transcriptomic and structural insights: Revealing drug repurposing opportunities for sporadic ALS. ACS omega 2024, 9, 3793–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerring, Z.F.; Bhalala, O.G.; Fearnley, L.G.; Oikari, L.E.; White, A.R.; Derks, E.M.; Watson, R.; Yassi, N.; Bahlo, M.; Reay, W.R. Drug repurposing candidates for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using common and rare genetic variants. Brain Communications 2025, 7, fcaf184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoolachan, J.M.; McCallion, E.; Sutton, E.R.; Çetin, Ö.; Pacheco-Torres, P.; Dimitriadi, M.; Sari, S.; Miller, G.J.; Okoh, M.; Walter, L.M.; et al. A transcriptomics-based drug repositioning approach to identify drugs with similar activities for the treatment of muscle pathologies in spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) models. Human molecular genetics 2024, 33, 400–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, S.D.; Basile, M.S.; Ciurleo, R.; Bramanti, A.; Arcidiacono, A.; Mangano, K.; Bramanti, P.; Nicoletti, F.; Fagone, P. A network medicine approach for drug repurposing in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Genes 2021, 12, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, L. CoupleVAE: Coupled variational autoencoders for predicting perturbational single-cell RNA sequencing data. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxi, E.G.; Thompson, T.; Li, J.; Kaye, J.A.; Lim, R.G.; Wu, J.; Ramamoorthy, D.; Lima, L.; Vaibhav, V.; Matlock, A.; et al. Answer ALS, a large-scale resource for sporadic and familial ALS combining clinical and multi-omics data from induced pluripotent cell lines. Nature neuroscience 2022, 25, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkirane, H.; Pradat, Y.; Michiels, S.; Cournède, P.H. CustOmics: A versatile deep-learning based strategy for multi-omics integration. PLOS Computational Biology 2023, 19, e1010921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.B.; Mazli, W.N.A.b.; Hao, L. Multiomics evaluation of human iPSCs and iPSC-derived neurons. Journal of proteome research 2024, 23, 3149–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doncevic, D.; Herrmann, C. Biologically informed variational autoencoders allow predictive modeling of genetic and drug-induced perturbations. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phatnani, H.; Kwan, J.; Sareen, D.; Broach, J.R.; Simmons, Z.; Arcila-Londono, X.; Lee, E.B.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Shneider, N.A.; Fraenkel, E.; et al. An integrated multi-omic analysis of iPSC-derived motor neurons from C9ORF72 ALS patients. Iscience 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckie, J.; Yokota, T. Integrating Machine Learning-Based Approaches into the Design of ASO Therapies. Genes 2025, 16, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, G.; Kwon, M.; Seo, D.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, D.; Lee, K.; Kim, E.; Kang, M.; Ryu, J.H. ASOptimizer: Optimizing antisense oligonucleotides through deep learning for IDO1 gene regulation. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids 2024, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Lee, D.; Hwang, G.; Lee, K.; Kang, M. ASOptimizer: Optimizing chemical diversity of antisense oligonucleotides through deep learning. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, gkaf392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wong, K.C. Off-target predictions in CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing using deep learning. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i656–i663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, S. Integration of artificial intelligence and genome editing system for determining the treatment of genetic disorders. Balkan Medical Journal 2024, 41, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.g.; Go, M.j.; Kang, S.H.; Jeong, S.h.; Lim, K. Revolutionizing CRISPR technology with artificial intelligence. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2025, 57, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoni, E.; Konstantakos, V.; Nentidis, A.; Krithara, A.; Paliouras, G. Modeling the off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9 experiments for the treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 12th Hellenic Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.; Jin, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S. Harnessing artificial intelligence to improve clinical trial design. Communications Medicine 2023, 3, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askin, S.; Burkhalter, D.; Calado, G.; El Dakrouni, S. Artificial intelligence applied to clinical trials: Opportunities and challenges. Health and technology 2023, 13, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refolo, P.; Raimondi, C.; Astratinei, V.; Battaglia, L.; Borràs, J.M.; Closa, P.; Lo Scalzo, A.; Marchetti, M.; Muñoz-López, S.; Sampietro-Colom, L.; et al. Ethical, Legal, and Social Assessment of AI-Based Technologies for Prevention and Diagnosis of Rare Diseases in Health Technology Assessment Processes. Healthcare 2025, 13, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.L.; Sawai, T. Navigating equity in global access to genome therapy expanding access to potentially transformative therapies and benefiting those in need requires global policy changes. Frontiers in Genetics 2024, 15, 1381172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Liu, X.; Rivera, S.C.; Moher, D.; Chan, A.W.; Sydes, M.R.; Calvert, M.J.; Denniston, A.K. Reporting guidelines for clinical trials of artificial intelligence interventions: The SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI guidelines. Trials 2021, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease locus | Abbrev. | Brief description | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor neuron | |||

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | ALS | Progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons; usually sporadic, with a minority of familial cases involving C9orf72, SOD1, TARDBP, or FUS. | Rare |

| Proximal spinal muscular atrophy | SMA | Childhood-onset hereditary lower motor neuron disease most often caused by SMN1. | Rare |

| Axon | |||

| Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (axonal) | CMT2 | Axonal neuropathy due to pathogenic variants in multiple genes. | Rare |

| Diabetic distal symmetric polyneuropathy | DSPN | Length-dependent axonal polyneuropathy due to chronic hyperglycemia and metabolic and vascular factors. | Common |

| Myelin | |||

| Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (demyelinating) | CMT1A | Hereditary demyelinating neuropathy caused by PMP22 gene duplication. | Uncommon |

| Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy | CIDP | Immune-mediated demyelinating neuropathy affecting peripheral nerves and roots. | Rare |

| Neuromuscular junction | |||

| Myasthenia gravis | MG | Autoimmune postsynaptic neuromuscular junction disorder, most commonly mediated by antibodies to acetylcholine receptors. | Uncommon |

| Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome | LEMS | Autoimmune presynaptic neuromuscular junction disorder caused by antibodies to P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels, often paraneoplastic. | Ultra-rare |

| Muscle | |||

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD | X-linked recessive dystrophinopathy due to pathogenic variants in DMD. | Rare |

| Myotonic dystrophy type 1 | DM1 | Autosomal dominant CTG-repeat expansion in DMPK, causing a multisystem distal myopathy with myotonia. | Rare |

| Context | CMT is a neurogenetic neuropathy with both motor and sensory features. |

|---|---|

| Canonical symptoms | Distal weakness, sensory loss, hyporeflexia, and muscle atrophy. |

| Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man phenotypes | Over 100 phenotypically distinct CMT entities in Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, including CMT1, CMT2, CMT4, dominant intermediate CMT (DI-CMT), X-linked CMT, and intermediate forms. |

| Genes implicated in CMT | Over 120 genes associated with hereditary neuropathies. Examples include PMP22, MPZ, GJB1, MFN2, NEFL, SH3TC2, and GDAP1. |

| Example gene: NEFL | |

| Gene-level complexity | NEFL is associated with three CMT phenotypes: CMT1F, CMT2E, and DI-CMT. ClinVar lists 786 NEFL variants, of which 28 are associated with CMT. |

| Protein-level complexity | These 786 NEFL variants correspond to many possible amino acid substitutions or truncations, each potentially altering neurofilament assembly, axonal transport, protein stability, and molecular interactions in distinct ways. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).