Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

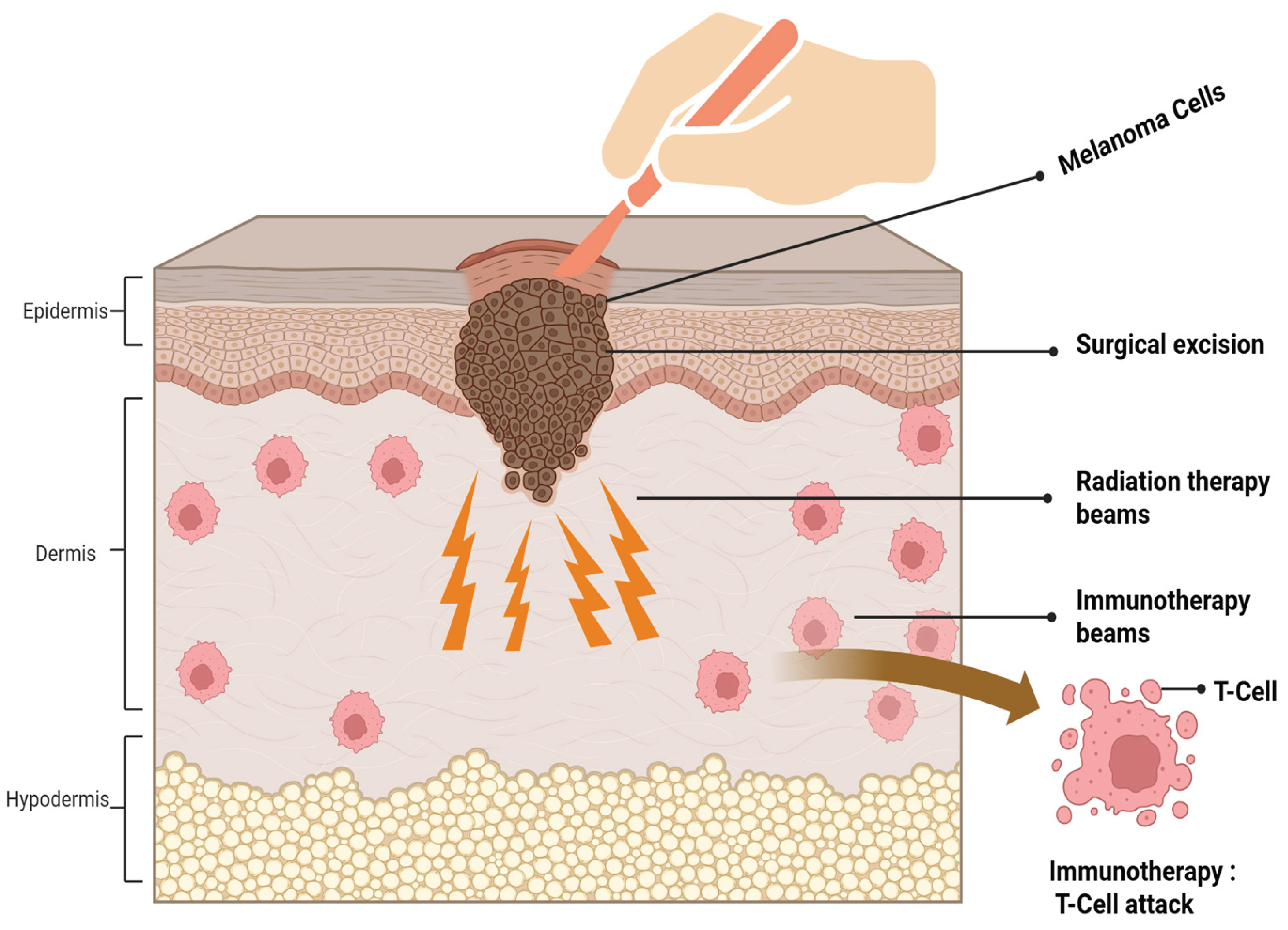

1. Introduction

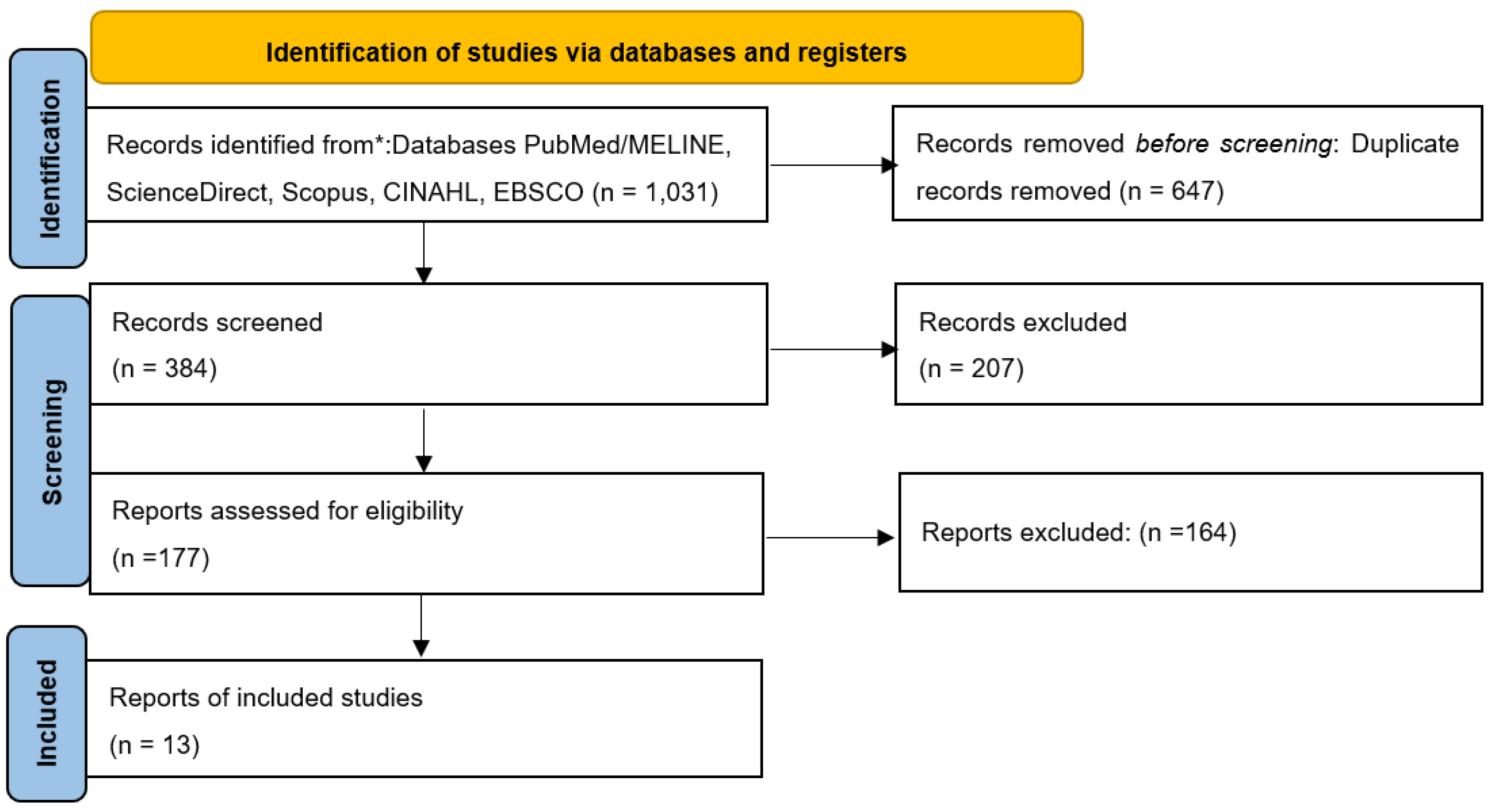

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection and Eligibility

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3.4. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Study

3.2. Quality of Studies

3.3. Clinical Characteristics and Patients’ Demographics of Included Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implication

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | Full term |

| CINAHL | Cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature |

| Covid-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| DM | Desmoplastic melanoma |

| DSS | Disease specific survival |

| EBSCO | Elton B. Stephen company (database) |

| Fr | Fractions |

| Fu | Follow up |

| GRADE | Grading of recommendation assessment development and evaluation |

| Gy | Gray (unit of radiation dose) |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs institute |

| LC | Local control |

| LR | Local recurrence |

| Mos | Months |

| MPR | Major pathological response |

| N/A | Not available |

| NCCN | North central cancer treatment group |

| NF1 | Neurofibromatosis type 1 |

| NO | Number |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PRADO | Personalized response directed surgery and adjuvant therapy (trial) |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SLNB | Sentinel lymph node biopsy |

| WLE | Wide local excision |

References

- Dunne, J.A.; Adigbli, G. The changing landscape in management of desmoplastic melanoma; Wiley Online Library, 2022; pp. 227–228. [Google Scholar]

- Girmay, Y.; et al. Desmoplastic melanoma in Sweden in 2009–2022: A population--based registry study demonstrating distinctive tumour characteristics, incidence and survival trends. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huayllani, M.T.; et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: clinical characteristics and survival in the US population. Cureus 2019, 11(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlev, J.; Lattes, R.W. Orr, Desmoplastic malignant melanoma (a rare variant of spindle cell melanoma). Cancer 1971, 28(4), 914–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; et al. Joinpoint regression analysis of recent trends in desmoplastic malignant melanoma incidence and mortality: 15-year multicentre retrospective study. Archives of Dermatological Research 2024, 316(6), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; et al. Incidence and survival of desmoplastic melanoma in the United States, 1992–2007. Journal of cutaneous pathology 2011, 38(8), 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, M.J.; et al. Desmoplastic and desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma: experience with 280 patients; Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society: Cancer, 1998; Volume 83, 6, pp. 1128–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, R.; Martin, S. S. McAllister, 1337 A Regional Review of The Epidemiology and Pathological Characteristics of Malignant Melanoma in Northern Ireland (NI), And Correlation with Socio-Economic Status. British Journal of Surgery 2021, 108 Supplement_6, p. znab258. 033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: demographic and clinicopathological features and disease-specific prognostic factors. Oncology Letters 2019, 17(6), 5619–5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydenlund, N.; Mahalingam, M. Desmoplastic melanoma, neurotropism, and neurotrophin receptors—what we know and what we do not. Advances in Anatomic Pathology 2015, 22(4), 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.C.; et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a rare variant with challenging diagnosis. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia 2019, 94(01), 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shain, A.H.; et al. Exome sequencing of desmoplastic melanoma identifies recurrent NFKBIE promoter mutations and diverse activating mutations in the MAPK pathway. Nature genetics 2015, 47(10), 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, S.E.; Moncrieff, M.D. A review of contemporary guidelines and evidence for wide local excision in primary cutaneous melanoma management. Cancers 2024, 16(5), 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszewski, D.E.; et al. The clinical behavior of desmoplastic melanoma. The American journal of surgery 2001, 182(6), 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smithers, B.M.; McLeod, G.R.; Little, J.H. Desmoplastic melanoma: patterns of recurrence. World journal of surgery 1992, 16(2), 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, N.A.; et al. Local recurrence rates after excision of desmoplastic melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatologic Surgery 2023, 49(4), 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busam, K.J.; et al. Cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma: reappraisal of morphologic heterogeneity and prognostic factors. The American journal of surgical pathology 2004, 28(11), 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.A.; Lentsch, E.J. Sentinel node biopsy in head and neck desmoplastic melanoma: an analysis of 244 cases. The Laryngoscope 2012, 122(1), 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; et al. Desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 128 cases. Cancer 2008, 113(10), 2770–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, M.C.; et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: the role of radiotherapy in improving local control. ANZ journal of surgery 2008, 78(4), 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagnolo, B.A.; et al. The role of adjuvant radiotherapy in the local management of desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer 2014, 120(9), 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, T.; et al. Radiotherapy influences local control in patients with desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer 2014, 120(9), 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule, W.G.; et al. Results of NCCTG N0275 (Alliance)–a phase II trial evaluating resection followed by adjuvant radiation therapy for patients with desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer medicine 2016, 5(8), 1890–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coit, D.G.; et al. Melanoma, Version 4.2014. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2014, 12(5), 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, Z.; et al. High response rate to PD-1 blockade in desmoplastic melanomas. Nature 2018, 553(7688), 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendra, K.; et al. Abstract CT009: S1512: High response rate with single agent anti-PD-1 in patients with metastatic desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer Research 2023, 83(8_Supplement). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, C.S.; et al. Adjuvant Radiation Therapy in Desmoplastic Melanoma: A Scoping Review. Cancers 2024, 16(22), 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, D.E.; et al. Roles of adjuvant and salvage radiotherapy for desmoplastic melanoma. Melanoma research 2016, 26(1), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.L.; et al. Comparing survival outcomes in early stage desmoplastic melanoma with or without adjuvant radiation. Melanoma Research 2019, 29(4), 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; et al. Clinicopathologic predictors of survival in patients with desmoplastic melanoma. PloS one 2015, 10(3), e0119716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkham, M.B.; et al. Randomized Trial of Postoperative Radiation Therapy After Wide Excision of Neurotropic Melanoma of the Head and Neck (RTN2 Trial 01.09). Annals of surgical oncology 2024, 31(9), 6088–6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasif, N.; Gray, R.J.; Pockaj, B.A.; et al. Desmoplastic melanoma–the step--child in the melanoma family? Journal of surgical oncology 2011, 103(2), 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj 2021, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Kibel, S.; et al. The Role of Adjuvant Radiotherapy for the Treatment of Resected High-Risk Stage III Cutaneous Melanoma in the Era of Modern Systemic Therapies. Cancers 2023, 15(24), 5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, W.M.; et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for cutaneous melanoma; Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society: Cancer, 2008; Volume 112, 6, pp. 1189–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Vongtama, R.; et al. Efficacy of radiation therapy in the local control of desmoplastic malignant melanoma; Journal for the Sciences and Specialties of the Head and Neck: Head & Neck, 2003; Volume 25, 6, pp. 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: is there a role for sentinel lymph node biopsy? Annals of surgical oncology 2013, 20(7), 2345–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; et al. Wide excision without radiation for desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer 2005, 104(7), 1462–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, W.; et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: A pathologically and clinically distinct form of cutaneous melanoma B. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2004, 11, S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizoguchi, N.; et al. Adjuvant therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors after carbon ion radiotherapy for mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: a case-control study. Cancers 2024, 16(15), 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijers, I.L.; et al. Personalized response-directed surgery and adjuvant therapy after neoadjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab in high-risk stage III melanoma: the PRADO trial. Nature medicine 2022, 28(6), 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Melan oma: Cutaneous. Version 2. 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org (accessed on 2025 Dec 3).

| Radiation dose regimen | No. of studies (%) | References |

|---|---|---|

| 30 Gy/5 fr | 4 (21%) | Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Strom (2014) [22], Rule (2016) [23] , Kibel (2023) [34] |

| 48 -50 Gy/20-25 fr | 3 (23%) | Chen (2008) [19], Foote(2008) [20], Mendenhall (2008) [35]. |

| 50-68 Gy (1.8-2 Gy/day) | 2 (15%) | Strom(2014) [22] , Mendenhall(2008)[35]. |

| 44-66 Gy (various fr) | 2 (15%) | Vongtama (2003) [36], Han (2013) [37] . |

| LR rate WITH RT | ||

| 0-10% (excellent LC) | 3 (23%) | Rule (2016) [23], Oliver (2016) [28], vangtama (2003) [36]. |

| 7-10% (very good LC) | 3 (23%) | Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Strom (2014) [22], Chen (2008)[19] . |

| 21% (moderate LC) | 1 (8%) | Foote (2008) [20]. |

| LR WITHOUT RT | ||

| 17% recurrence rate | 3 (23%) | Strom (2014), Han (2013) [37], Kibel (2023) [34]. |

| 24% recurrence rate | 3 (23%) | Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Vongtama (2003) [36], Pinkham (2024) [31]. |

| ˃50% historical rates | 2 (15%) | Vongtama (2003) [36],Arora (2005) [38]. |

| Primary site | ||

| Head & neck (55-68%) | 11 (85%) | Strom (2014) [22] , Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Vongtama (2003) [36] , rule (2016) [23], Chen(2008) [19] ,Foote (2008) [20] , Mendenhall (2008) [35] , Pinkham (2024) [31], Oliver(2016) [28] ,Han (2013) [37], Kibel (2023) [34]. |

| Extremities | 3 (23%) | Rule (2016) [23] , Strom (2014) [22], Pinkham (2024) [31]. |

| Trunk | 3 (23%) | Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Rule (2016) [23], Strom (2014) [22]. |

| Tumor histology | ||

| Pure desmoplastic (≥90%) | 4 (31%) | Strom (2014) [22], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Hawkins (2004) [39], Chen (2008) [19]. |

| Mixed desmoplastic (˂90%) | 5 (38%) | Strom (2014) [22], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Han (2013) [37], Pinkham (2024) [31], Arora (2005) [38]. |

| Resection margin | ||

| Negative | 9 (69%) | Strom (2014) [22], Guadagnolo (2014) [21]; Rule (2016) , Chen (2008) ; Foote (2008) [20] , Mendenhall (2008) [35],Pinkham (2024) [31], Oliver (2016) [28], Han (2013) [37], Hawkins (2004) [39]. |

| Positive/uncertain | 2 (15%) | Strom (2014) [22], Guadagnolo (2014) [21]. |

| Perineural invasion | ||

| Present | 5 (38%) | Strom (2014) [22], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Chen (2008) [19], Pinkham (2024) [31] , Kibel ( 2023) [34]. |

| Absent | 5 (38%) | Foote (2008) [20], Mendenhall (2008) [35], Rule (2016) [23], Oliver (2016) [28], Vongtama (2003) [36]. |

| Clark level | ||

| Clark level IV (reticular dermis) | 7 (54%) | Strom (2014) [22], Rule (2016) [23], Chen (2008) [19] , Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Pinkham (2024) [31], Han (2013) [37] , Kibel ( 2023) [34]. |

| Clark level V (subcutaneous) | 8 (62%) | Strom (2014) [22], Rule (2016) [23], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Chen (2008) [19], Foote (2008)[20], Oliver (2016) [28], Vongtama (2003) [36], Kibel ( 2023)[34]. |

| Breslow depth ˃4 mm | 5 (38%) | Strom (2014) [22], Rule (2016) [23], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Chen (2008) [19], Pinkham (2024)[31] . |

| LC outcomes | ||

| LC ˃90% at 5 years | 5 (38%) | Strom (2014) [22], Rule (2016) [23], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Pinkham (2024) [31], Kibel ( 2023) [34]. |

| LC 80-90% at 5 years | 4 (31%) | Vongtama (2003) [36], Foote (2008) [20], Chen (2008) [19], Oliver (2016) [28]. |

| ≥10% absolute improvement with RT | 4 (31%) | Strom (2014) [22], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Rule(2016) [23] ,Chen (2008) [19]. |

| Survival outcomes | ||

| OS ˃75% at 5 years | 6 (46%) | Rule (2016) [23], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Strom (2014) [22], Chen (2008) [19], Pinkham (2024)[31], Kibel ( 2023)[34]. |

| DSS ˃80% at 5 years | 5 (38%) | Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Strom (2014) [22], Chen (2008) [19], Rule (2016) [23], Kibel ( 2023) [34]. |

| OS/DSS ˂75% without RT | 3 (23%) | Kibel (2023) [34], Arora (2005) [38], Han (2013) [37]. |

| FU duration | ||

| Median 40-65 months | 7 (54%) | Strom (2014) [22] ,Rule (2016) [23],Guadagnolo (2014) [21],Chen (2008)[19], Han (2013) [37],Oliver (2016) [28], Kibel ( 2023) [34]. |

| 3-6 years FU | 5 (38%) | Foote (2008) [20], Mendenhall (2008) [35],Vongtama (2003) [36] ,Pinkham (2024) [31], Arora (2005) [22]. |

| ˃6 years long term FU | 3 (23%) | Guadagnolo (2014)[21], Strom (2014) [22], Kibel ( 2023) [34]. |

| Characteristics/study design | No. of studies | Author name |

|---|---|---|

| Retrospective cohort studies | 10 (77%) | Strom (2014) [22], Guadagnolo (2014)[21], Chen(2008) [19], Foote (2008)[20], Han (2013)[37], Oliver (2016) [28], Vongtama (2003) [36], Mendenhall (2008) [35], Arora (2005) [38], Mizoguchi (2024) [40]. |

| Prospective/clinical trials | 3(23%) | Rule (2016) [23], Pinkham (2024) [31], Reijers (2022) [41]. |

| Geographic locations | ||

| North America | 8(62%) | Strom (2014) [22], Rule (2016) [23], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Mendenhall (2008) [35], Han (2013) [37], Oliver (2016) [28], Arora (2005) [38], Vongtama (2003) [36]. |

| Australia | 3 (23%) | Chen (2008) [19], Foote (2008)[20], Pinkham (2024) [31]. |

| Europe | 1(8%) | Rejiers (2022) [41]. |

| Asia | 1(8%) | Mizoguchi (2024) [40]. |

| Study settings | ||

| Academic centers | 9 (69%) | Strom(2014)[22],guag gnolo (2014)[21],Chen (2008) [19] ,Foote (2008) [20] , Mendenhall(2008) [35], Pinkham (2024) [31], Reijers (2022) [41], Mizoguchi (2024) [40], Arora (2005) [38]. |

| Specialized melanoma/cancer clinic | 4(31%) | Rule (2016) [23], Han (2013) [37], Oliver (2016) [28],vongtama (2003) [36] |

| Publications period | ||

| 2000-2010 | 4(31%) | Vongtama (2003) [36], Arora (2005) [38], Chen (2008) [19], Foote (2008) [20]. |

| 2011-2018 | 5(38%) | Strom (2014) [22], Guadagnolo (2014) [21], Han (2013) [37], Rule (2016) [23], Oliver (2016) [28]. |

| 2019-2025 | 4(31%) | Mendenhall (2008) [35], Mizoguchi (2024) [40], Reijers (2022) [41], Pinkham (2024) [31]. |

| Study | Study Type | Assessment Tool | Quality Score | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strom (2014) [22] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | ≥80% | High |

| Guadagnolo (2014) [21] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | ≥80% | High |

| Rule (2016) [23] | Phase II Trial | JBI Experimental | 95% | High |

| Vongtama (2003)[36] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | 50-79% | Moderate |

| Chen (2008) [19] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | ≥80% | High |

| Foote (2008) [20] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | 50-79% | Moderate |

| Mendenhall (2008) [35] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | ≥80% | High |

| Pinkham (2024) [31] | Randomized Trial | JBI Experimental | 89% | High |

| Arora (2005) [38] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | 50-79% | Moderate |

| Han (2013) [37] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | ≥80% | High |

| Oliver (2016) [28] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | 50-79% | Moderate |

| Mizoguchi (2025) [40] | Retrospective Cohort | JBI Cohort | ≥80% | High |

| Reijers (PRADO) (2022) [41] | Prospective Trial | JBI Experimental | 92% | High |

| Study Author | Study Design | PatientNo. | RT Dose (Gy) | LR WITH RT (%) | LR WITHOUT RT (%) | FU (mos) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strom (2014) [22] | Retrospective Cohort | 277 | 30 (5#) | 7% | 17% | 48-60 | Improved local control with adjuvant RT |

| Guadagnolo (2014) [21] | Retrospective Cohort | 130 | 30 (5#) | 7% | 24% | 50-65 | Significant LR reduction with RT |

| Rule (2016) [23] | Phase II Trial | 20 | 30 (5#) | 10% | N/A | 36 | Adjuvant RT efficacious & well tolerated |

| Vongtama (2003) [36] | Retrospective | 31 | 44-66 | 0-10% | >50% | 40-60 | RT beneficial for DM with high recurrence risk |

| Chen (2008) [19] | Retrospective | 128 | 50-68 | 7-10% | 17% | 50-65 | Reduced LR with adjuvant RT |

| Foote (2008) [20] | Retrospective | 27 | 48-50 | 21% | 17% | 36-72 | RT improves LC outcomes |

| Mendenhall (2008) [35] | Retrospective | 189 | 50-68 | 8% | 18% | 48-60 | Stage T3-4: recommend adjuvant RT |

| Pinkham (2024) [31] | Randomized Trial | 50 | 20-48 | 4% (3-yr) | N/A | 36 | RTN2 Trial: RT reduces neurotropic melanoma recurrence |

| Arora (2005) [38] | Retrospective | 43 | None | N/A | >50% | 48-60 | Wide excision alone insufficient |

| Han (2013) [37] | Retrospective | 128 | 44-66 | 9% | 17% | 48-72 | SLNB accuracy affected by desmoplasia |

| Oliver (2016) [28] | Retrospective | 58 | 30-50 | 8% | 14% | 40-60 | Adjuvant and salvage RT roles |

| Mizoguchi (2024) [40] | Retrospective | 87 | Carbon ion RT | 5% | 15% | 50-60 | Carbon ion RT effective for mucosal melanoma |

| Reijers (2022) [41] | Prospective Trial | 99 | Neoadjuvant ICI | 6% (MPR 24-mo) | N/A | 24 | Response-directed therapy improves outcomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).