Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

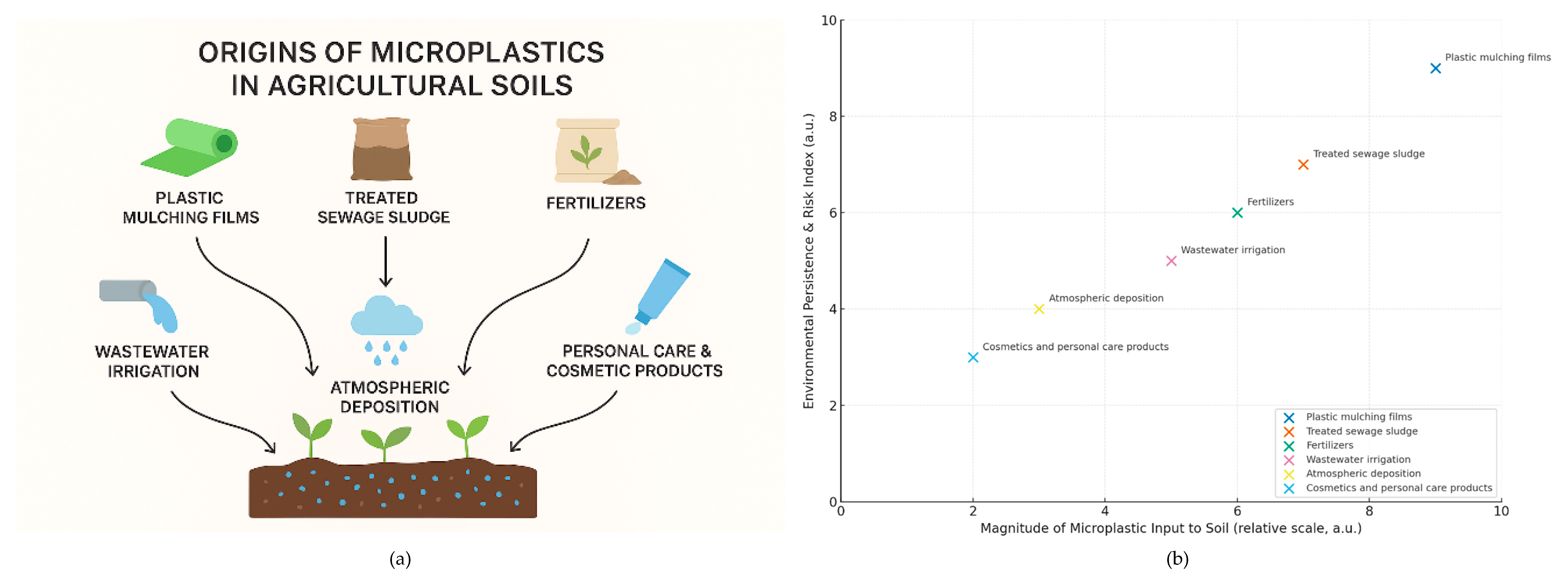

2. Origins of Microplastics in Agricultural Soils

2.1. Plastic Mulching Films

2.2. Treated Sewage Sludge (Biosolids)

2.3. Fertilizers

2.4. Wastewater Irrigation

2.5. Atmospheric Deposition

2.6. Personal Care and Cosmetic Products

3. Occurrences of Microplastics in Agricultural Soils

3.1. Microplastic Particle Size

3.2. Microplastic Shape

3.3. Microplastic Color

3.4. Microplastic Polymer Type

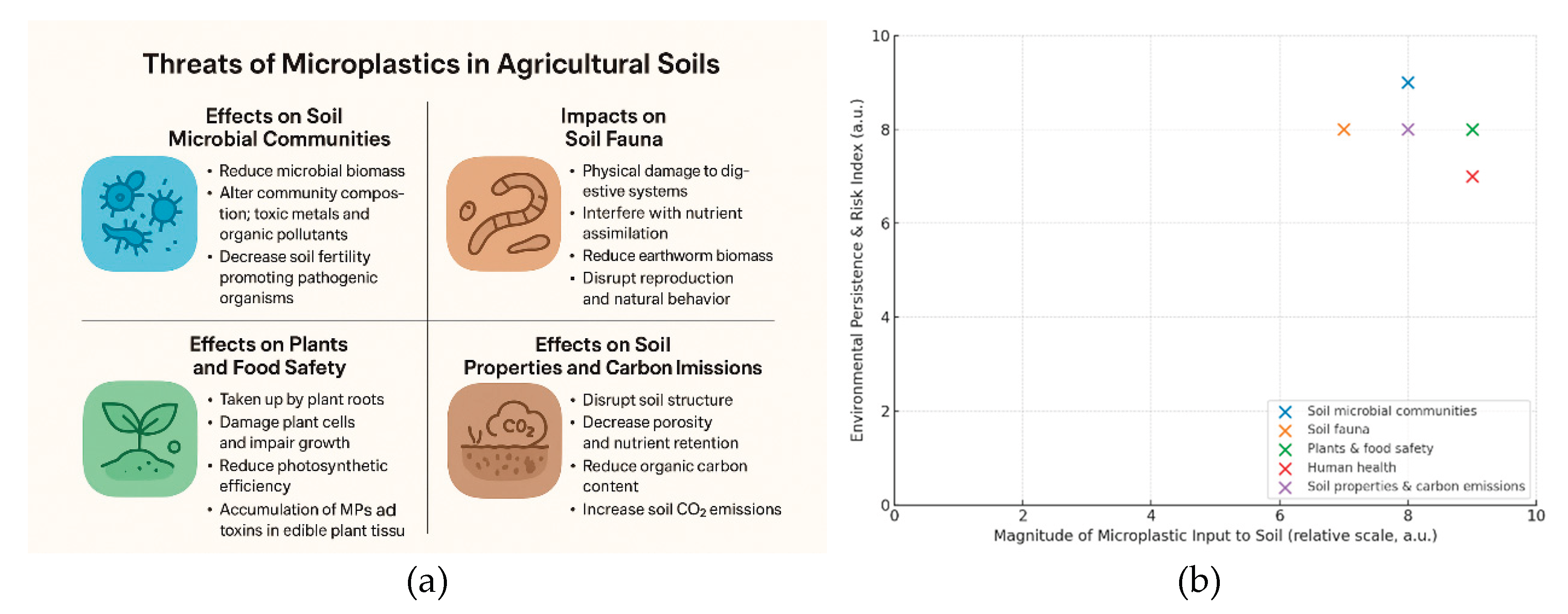

4. Threats of Microplastics in Agricultural Soils

4.1. Effects on Soil Microbial Communities

4.2. Impact on Soil Fauna

4.3. Effects on Plants and Food Safety

4.4. Risks to Human Health

4.5. Effects on Soil Properties and Carbon Emissions

4.6. Combined Toxicity of Microplastics and Co-Occurring Contaminants

4.7. Summary of the Potential Impacts of Soil Microplastics

5. Management Strategies and Future Perspectives

5.1. Remediation and Mitigation Strategies

Biocatalytic and Photocatalytic Degradation:

Soil Amendment with Biochar:

Thermal Treatment Technologies:

Phytoremediation:

Microbial Degradation:

5.2. Physical and Chemical Remediation Methods

- Density Separation and Centrifugation:

- Chemical Digestion and Filtration:

- Oil-Based Extraction:

- Flotation:

5.3. Agricultural Management and Policy Measures

- Reduction in Plastic Film Use:

- Adoption of Biodegradable Alternatives:

- Legislation and Awareness:

5.4. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Key challenges include:

- The complex nature of terrestrial ecosystems, which hinders effective monitoring of MP transport and transformation.

- Laboratory simulations often fail to replicate real-world soil dynamics, leading to inaccurate risk assessments.

- The lack of long-term, standardized experimental designs limits understanding of MP impacts over time.

Future research should:

- Develop ecological indicators strongly correlated with MP impacts.

- Implement tiered ecological risk assessment models incorporating these indicators.

- Improve understanding of MP degradation pathways and interactions with soil biota.

- Explore scalable and sustainable remediation technologies adapted to field conditions.

6. Conclusions

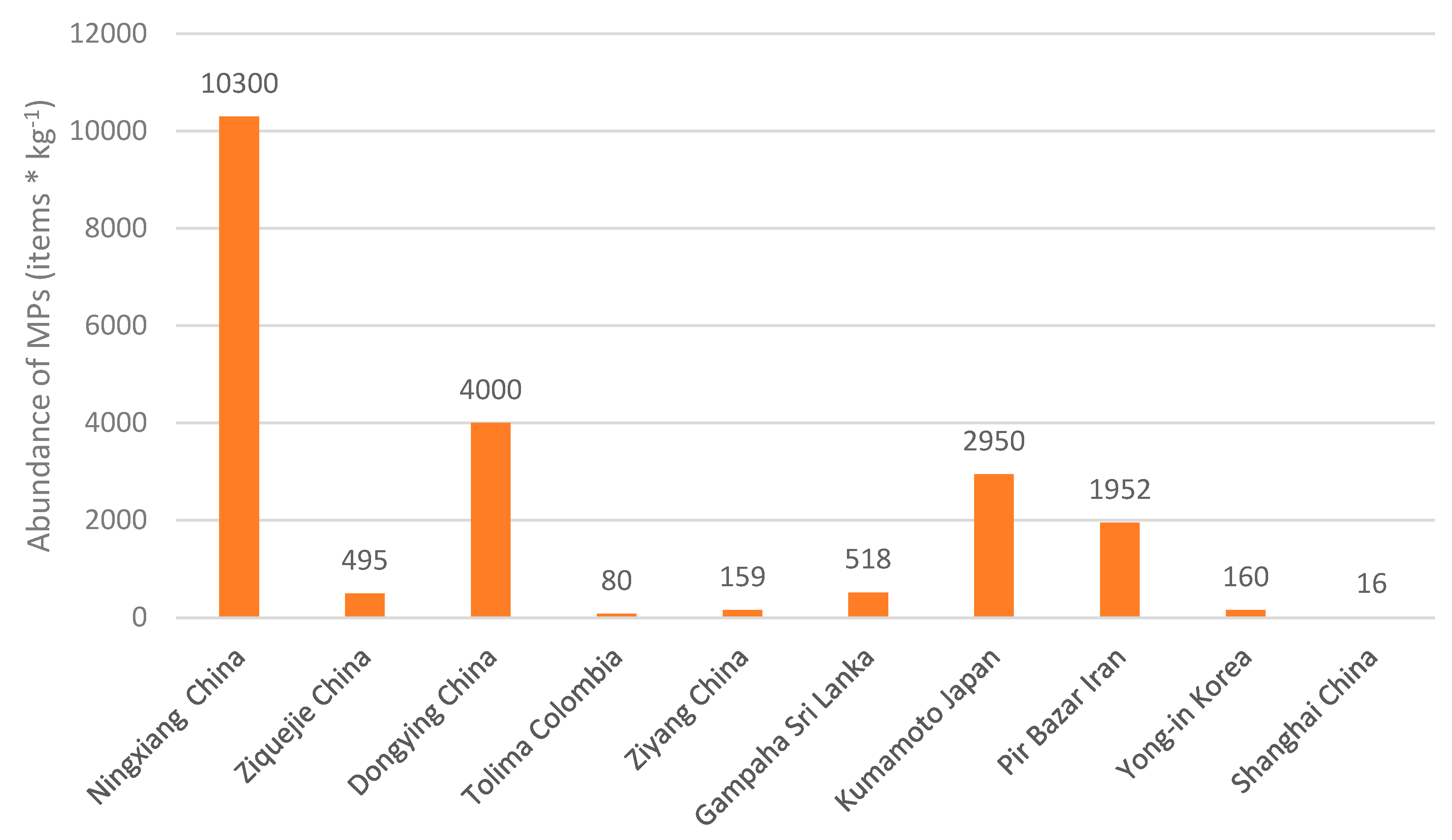

- The abundance of microplastics (MPs) in paddy soils varies significantly across different study areas worldwide (ranging from 16 to 10,300 items/kg). This variation may be attributed to several factors, including irrigation water transport, improper plastic waste management, weather conditions, application of coated fertilizers and atmospheric deposition, among others.

- Mulching film is considered the primary source of microplastic pollution in agricultural soils worldwide.

- Facility agriculture (e.g., greenhouses and vegetable cultivation) and perennial crops (such as orchards and vineyards) are linked to elevated levels of soil microplastic pollution across various crop types.

- Fibers are the most commonly detected microplastic shape in agricultural soils, primarily originating from plastic mulching films and the application of sewage sludge.

- Black, blue, and transparent are the predominant microplastic colors reported in agricultural soils.

- Polyethylene (PE) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) are the predominant microplastic polymer types identified in agricultural soils.

- Polystyrene (PS) is frequently identified as the most common polymer type associated with the potential risks of soil microplastic pollution.

- Oxidative stress and the release of chemical additives through leaching represent the most commonly reported mechanisms underlying the toxicity of soil MPs across a wide range of exposed biological targets.

- Limited plant growth is the most frequently reported effect of soil microplastic pollution, attributed to factors such as reduced root colonization by mycorrhizal fungi, cellular toxicity in roots, decreased photosynthetic activity, and lower soil pH.

- Quantitative evaluations of fungal-driven microplastic biodegradation under laboratory and soil-relevant conditions have reported mean degradation efficiencies of the MPs at around 7.5% after a 50-day incubation period, while other studies have documented total mass losses of around 24% after 30 days and 35–38% after 90 days of incubation.

Author Contributions

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista Research Department (S.R.D.). Annual production of plastics worldwide from 1950 to 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/282732/global-production-of-plastics-since-1950/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Napper, I.E.; Thompson, R.C. (2020). Plastic debris in the marine environment: history and future challenges. Glob. Chall. 2020, 4, 1900081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y. The occurrence of microplastics in farmland and grassland soils in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau: different land use and mulching time in facility agriculture. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 279, 116939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Fang, W.; Liang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q. A critical review on interaction of microplastics with organic contaminants in soil and their ecological risks on soil organisms. Chemosphere 2022, 306, 135573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, F.; Sun, Q. Behavior and mechanism of atrazine adsorption on pristine and aged microplastics in the aquatic environment: kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Chemosphere 2022, 292, 133425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Y.; Gao, J. M.; Pei, Y. Z.; Luo , K. Y.; Yang, W.H.; Wu, J. C.; Yue, X. H.; Jiong Wen, J.; Luo, Y. Microplastics in agricultural soils: A comprehensive perspective on occurrence, environmental behaviors and effects. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151328. [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.; Jho, E.H. Current research trends on the effects of microplastics in soil environment using earthworms: mini-review. J. Korean Soc. Environ. Eng. 2021, 43(4), 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhong, S.; Qian, Y.; Gao, P. An overlooked entry pathway of microplastics into agricultural soils from application of sludge-based fertilizers. Environ. Sci. & Technol. 2020, 54(7), 4248–4255. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, S.; Gautam, A. A procedure for measuring microplastics using pressurized fluid extraction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5774–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ding, F.; Flury, M.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L.; Li, S.; Jones, D.L.; Wang, J. Macro- and microplastic accumulation in soil after 32 years of plastic film mulching. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 300, 118945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Ye, Y.; Qi, K. Effects of agricultural land types on microplastic abundance: A nationwide meta-analysis in China. Sci.Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, V.-H.; Nguyen, M.-K.; Hoang, T.-D.; Ha, M. C.; Huyen, N. T. T.; Bui, V. K. H.; Pham, M.-T.; Nguyen, C.-M.; Chang, S. W.; Nguyen, D. D. Sources, environmental fate, and impacts of microplastic contamination in agricultural soils: A comprehensive review Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, A.E.; Köper, I. Microplastics in biosolids: a review of ecological implications and methods for identification, enumeration, and characterization. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Qi, R.; Xu, W.; Yan, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Jones, D. L.; Chadwick, D. R. (2023). Potential sources and occurrence of macro-plastics and microplastics pollution in farmland soils: A typical case of China. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 54(7), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Machado, A. A.; Lau, C. W.; Till, J.; Kloas, W.; Lehmann, A.; Becker, R.; Rillig, M. C. Impacts of microplastics on the soil biophysical environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9656–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza Machado, A. A.; Lau, C. W.; Kloas, W.; Bergmann, J.; Bachelier, J. B.; Faltin, E.; Becker, R.; Görlich, A. S.; Rillig, M. C. Microplastics can change soil properties and affect plant performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6044–6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Υ.; Hou, P.; Liu, Κ.; Hayat, Κ.; Liu, W. Depth distribution of nano- and microplastics and their contribution to carbon storage in Chinese agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Wang, X.; Yin, L.; Chen, S.; Tao, J.; Zhou, W.; Chen, H.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, R. Research progress of microplastics in soil-plant system: ecological effects and potential risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 812, 151487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, R.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, F. Uptake and translocation of nano/microplastics by rice seedlings: evidence from a hydroponic experiment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, G.O.; Ferrante, M.; Banni, M.; Favara, C.; Nicolosi, I.; Cristaldi, A.; Fiore, M.; Zuccarello, P. Micro- and nano-plastics in edible fruit and vegetables. The first diet risks assessment for the general population. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 109677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusza, H.M.; van Boxel, J.; van Duursen, M.B.M.; Forsberg, M.M.; Legler, J.; Vahakangas, K.H. Experimental human placental models for studying uptake, transport and toxicity of micro- and nanoplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 860, 160403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boughattas, I.; Hattab, S.; Zitouni, N.; Mkhinini, M.; Missawi, O. Assessing the presence of microplastic particles in and their potential toxicity effects using Eisenia andrei as bioindicator. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, B.; Zhao, T.; Yin, W.; Zhao, X.; Xie, Q.; Khan, K.Y.; Zhao, X.; Nazar, M.; Li, G.; Du, D. Impacts of soil microplastics on crops: a review. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 181, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Shi, R.; Fu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, C.; Liu, W. Impact of microplastics on plant physiology: A meta-analysis of dose, particle size, and crop type interactions in agricultural ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 177245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.G.; You, X.Y. Recent progress of microplastic toxicity on human exposure base on in vitro and in vivo studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Han, J. The factors affecting microplastic pollution in farmland soil for different agricultural uses: A case study of China. Catena 2024, 239, 107972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q.; Yang, B.; Jiao, J.; Ma, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, X. Response of microplastic occurrence and migration to heavy rainstorm in agricultural catchment on the Loess plateau. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Bian, P.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, W. Effects of irrigation on the fate of microplastics in typical agricultural soil and freshwater environments in the upper irrigation area of the Yellow River. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 447, 130766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M. M.; Tarannum, M. N. Adverse impacts of microplastics on soil physicochemical properties and crop health in agricultural systems. J. Hazard. Mater. Advances 2024, 17, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jia, W.; Yan, C.; Wang, J. Agricultural plastic mulching as a source of microplastics in the terrestrial environment. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 114096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanayaka, S.; Zhang, H.; Semple, K. T. Environmental fate of microplastics and common polymer additives in non-biodegradable plastic mulch applied agricultural soils. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonsong, P.; Ussawarujikulchai, A.; Prapagdee, B.; Pansak, W. Contamination of microplastics in greenhouse soil subjected to plastic mulching. Environ. Technol. & Innov. 2024, 37, 103991. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yan, C.; Chadwick, D.; Jones, D.L.; Liu, E.; Liu, Q.; Bai, R.; He, W. Kinetics of microplastic generation from different types of mulch films in agricultural soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 152572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wufuer, R.; Duo, J.; Wang, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Pan, X. Microplastics in agricultural soils: Extraction and characterization after different periods of polythene film mulching in an arid region. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harley-Nyang, D.; Ali Memon, F.; Baquero, A. O.; Galloway, T. Variation in microplastic concentration, characteristics and distribution in sewage sludge & biosolids around the world. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164068. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, M.; Gutow, L.; Klages, M. Marine anthropogenic litter, first ed.; Springer: New York, USA, 2015; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Heinze, W. M.; Steinmetz, Z.; Klemmensen, N. D. R.; Vollertsen, J.; Cornelis, G. Vertical distribution of microplastics in an agricultural soil after long-term treatment with sewage sludge and mineral fertilizer. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 356, 124343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, W.; An, L.; Zhang, S.; Feng, J.; Sun, D.; Yao, Y.; Shen, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M. The long-term effects of microplastics on soil organomineral complexes and bacterial communities from controlled-release fertilizer residual coating. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 304, 114193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, L.; Gopakumar, A. N.; Beheshtimaal, A.; Farhad Jazaei, F.; Ccanccapa-Cartagena, A.; Salehi, M. Mechanisms of microplastic generation from polymer-coated controlled-release fertilizers (PC-CRFs). J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 486, 137082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumi, N.; Kusube, T.; Nagao, S.; Okochi, H. Accumulation of microcapsules derived from coated fertilizer in paddy fields. Chemosphere 2021, 267, 129185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xiao, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Ru, S.; Zhao, M. Unraveling the characteristics of microplastics in agricultural soils upon long-term organic fertilizer application: A comprehensive study using diversity indices. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang,X.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Xiaoqi Yin, X.; Zhang, X. Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in organic fertilizers in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 157061. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, W.; Xing, Z. From organic fertilizer to the soils: What happens to the microplastics? A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.; Nan, Z. Exploring the safe utilization strategy of calcareous agricultural land irrigated with wastewater for over 50 years. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Ewins, C.; Carbonnier, F.; Quinn, B. Wastewater treatment works (WwTW) as a source of microplastics in the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. & Technol. 2016, 50, 5800–5808. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayaturrahman, H.; Lee, T.G. A study on characteristics of microplastic in wastewater of South Korea: identification, quantification, and fate of microplasticsduring treatment process. Mar.Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Reverón, R.; González-Sálamo, J.; Hernández-Sánchez, C.; González-Pleiter, M.; Hernández-Borges, J.; Díaz-Peña, F. J. Recycled wastewater as a potential source of microplastics in irrigated soils from an arid-insular territory (Fuerteventura, Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragoobur, D.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Somaroo, G. D. Microplastics in agricultural soils, wastewater effluents and sewage sludge in Mauritius. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.-J.; Hanun, J.N.; Chen, K.-Y.; Hassan, F.; Liu, K.-T.; Hung, Y.-H.; Chang, T.-W. Current levels and composition profiles of microplastics in irrigation water. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Y.; Chen, R.; Xue, S.; Liu, M.; Tang, D.; Yang, X.; Giessen, V. Irrigation-facilitated low-density polyethylene microplastic vertical transport along soil profile: an empirical model developed by column experiment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 247, 114232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, G.; Nie, Z.; Liu, G.; Huang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Meng, Y. Microplastic pollution in the qinghai-tibet plateau: current state and future perspectives. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2023, 261, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.; Fischer, E.K. Microplastic abundance in atmospheric deposition within the Metropolitan area of Hamburg, Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhai, J.; Cong, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C. Comparison of dry and wet deposition of particulate matter in near-surface waters during summer. PLoS One 2018, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Pearce, C.I.; Sanguinet, K.A.; Bary, A.I.; Chowdhury, I.; Eggleston, I.; Xing, B.; Flury, M. Accumulation of microplastics in soil after long-term application of biosolids and atmospheric deposition. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R.; Le Roux, G.; Jimenez, P.D.; Simonneau, A.; Binet, S.; Galop, D. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Alirezazadeh, M.; Razeghi, N.; Rezaei, M.; Pourmahmood, H.; Dehbandi, R.; Mehr, M.R.; Ashayeri, S.Y.; Oleszczuk, P.; Turner, A. Microplastics captured by snowfall: a study in Northern Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Zou, X.; Wang, C.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Q.; Chen, H. The abundance and characteristics of atmospheric microplastic deposition in the northwestern South China Sea in the fall. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 253, 11838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Peng, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Fu, W.; Dai, X.; Ni, B. The atmospheric microplastics deposition contributes to microplastic pollution in urban waters. Water Res. 2022, 225, 119116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Sun, C.; He, C.; Zheng, L.; Dai, D.; Li, F. Atmospheric microplastics in the northwestern Pacific Ocean: distribution, source, and deposition. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukkola, A.; Chetwynd, A. J.; Stefan Krause, S.; Lynch, I. Beyond microbeads: Examining the role of cosmetics in microplastic pollution and spotlighting unanswered questions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitko, V.; Hanlon, M. Another source of pollution by plastics skin cleaners with plastic scrubbers. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1991, 22, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.R. Plastic ‘scrubbers’ in hand cleansers: a further (and minor) source for marine pollution identified. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1996, 32(12), 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Shoaib, N.; Pan, Z.; Pan, K.; Sun, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L. Occurrence characteristics and ecological impact of agricultural soil microplastics in the Qinghai Tibetan Plateau, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Feng, W.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Occurrence, sources, and risks of microplastics in agricultural soils of Weishan Irrigation District in the lower reaches of the Yellow River, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 491, 137849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Min, W.; Flury, M.; Gunina, A.; Lv, J.; Li, Q.; Jiang, R. Impact of long-term conventional and biodegradable film mulching on microplastic abundance, soil structure and organic carbon in a cotton field. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 356, 124367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athavuda, S.; Weerasinghe, T.; Pathirana, K.; Dabare, P.; Rathnayake, N.; Samarakoon, T.; Hemachandra, C. K. Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in agricultural lands in the Gampaha district of Sri Lanka: Insights from selected paddy fields, vegetable plots, and coconut cultivations. Next Res. 2024, 2, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lu, S.; Song, Y.; Lei, L.; Hu, J.; Lv, W.; Zhou, W.; Cao, C.; Shi, H.; Yang, X.; He, D. Microplastic and mesoplastic pollution in farmland soils in suburbs of Shanghai, China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, W.; Wang, S.; Ha, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhao, M.; Zou, G.; Chen, Y. Pollution characteristics of microplastics in greenhouse soil profiles with the long-term application of organic compost. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 17, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Riksen, M.; Sirjani, E.; Sameni, A.; Geissen, V. Wind erosion as a driver for transport of light density microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beriot, N.; Peek, J.; Zornoza, R.; Geissen, V.; Huerta-Lwanga, E. Low density- microplastics detected in sheep faeces and soil: a case study from the intensive vegetable farming in Southeast Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaus, J.; Seeger, M.; Bigalke, M.; Weber, C. J. Microplastics in vineyard soils: First insights from plastic-intensive viticulture systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, L.; Gong, L.; Li, G.; Xiu, W.; Yang, X.; Tan, B.; Jianning Zhao, J.; Zhang, G. Differences, links, and roles of microbial and stoichiometric factors in microplastic distribution: A case study of five typical rice cropping regions in China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 985239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, X.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Yuan, Y.; You, P.; Yingxing Liu, Y.; Lingshi Yin, L. Retention and migration of microplastics in stepped paddy fields: A study on microplastic dynamics in the special irrigation system. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120909. [CrossRef]

- Munoz Yustres, J.L.; Zapata-Restrepo, L.M.; Garcia-Chaves, M.C.; Gomez-Mendez, L.D. Microplastics in rice-based farming systems and their connection to plastic waste management in the Chicoral district of Espinal-Tolima. Chemosphere 2025, 378, 144423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, K.; Tu, C.; Li, L.; Feng, Y.; Li, R.; Xu, H.; Luo, Y. Distribution and weathering characteristics of microplastics in paddy soils following long-term mulching: A field study in Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 858, 159774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Hirota, Y.; Tsukayama, K.; Ikejima, K.; Katsutoshi Sakurai. K. Separation and Measurement of Microplastics in Paddy Soil. J. Environ. Prot. 2024, 15, 1016–1021. [CrossRef]

- Amirhosseini, K.; Haghani, Z.; Alikhani, H.A. Microplastics pollution in rice fields: a case study of Pir Bazar rural district of Gilan, Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Kim, J.-S.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.-J. Abundance and characteristics of microplastics in soils with different agricultural practices: Importance of sources with internal origin and environmental fate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 403, 123997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Zhou, W.; Lu, S.; Huang, W.; Yuan, Q.; Tian, M.; Lv, W.; He, D. Microplastic pollution in rice-fish co-culture system: A report of three farmland stations in Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 652, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yulan Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Wang, S.; Gao, T.; Wang, Z.; Luo, X.; Kang, Q.; Sajjad, W. Characteristics of microplastics and their abundance impacts on microbial structure and function in agricultural soils of remote areas in west China. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 360, 124630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, F.; Meza, P.; Eguiluz, R.; Casado, F.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Geissen, V. Evidence of microplastic accumulation in agricultural soils from sewage sludge disposal. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Li, L.; Li, R.; Xu, L.; Shen, Y.; Li, S.; Tu, C.; Wu, L.; Christie, P.; Luo, Y. Microplastics in an agricultural soil following repeated application of three types of sewage sludge: A field study. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, P.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Corradini, F.; Geissen, V. Sewage sludge application as a vehicle for microplastics in eastern Spanish agricultural soils. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 261, 114198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Xu, J.; Fu, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Han, J.; Kong, J.; Ma, Y. Microplastic accumulation and transport in agricultural soils with long-term sewage sludge amendments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.F.; He, G.; Jiang, X.L.; Yao, L.G.; Ouyang, L.; Liu, X.Y.; Liu, W.Z.; Liu, Y. Microplastic contamination is ubiquitous in riparian soils and strongly related to elevation, precipitation and population density. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 411, 125178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, S.T.; Li, H.Y.; Chen, X.C.; Peng, C.; Zhang, P.P.; Liu, X.H. Distinct microplastic distributions in soils of different land-use types: a case study of Chinese farmlands. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, J.D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.Y.; Tao, S.; Liu, W.X. Distribution characteristics of microplastics in agricultural soils from the largest vegetable production base in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Jiang, J.; Mo, A.; He, D. Size/shape-dependent migration of microplastics in agricultural soil under simulative and natural rainfall. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, D.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ke, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, W.; Luo, Y.; Peter Christie, P.; Wu, L. Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in coastal plain soils under three land-use types. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 855, 159023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Cai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xing, S.; Liao, X. Occurrence of microplastic in livestock and poultry manure in South China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 277, 116790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Muhammad, I.; Yin, C.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Zheng, L. Significant influence of land use types and anthropogenic activities on the distribution of microplastics in soil: A case from a typical mining-agricultural city. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zeng, A.; Jiang, X.; Gu, X. Are microplastics correlated to phthalates in facility agriculture soil? J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Ding, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.; Yao, H.; Zhu, Z.; Chadwick, D. R.; Jones, D.; Chen, J.; Ge, T. Microplastics shape microbial communities affecting soil organic matter decomposition in paddy soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 431, 128589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza Machado, A.A.; Kloas, W.; Zarfl, C.; Hempel, S.; Rillig, M.C. Microplastics as an emerging threat to terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24(4), 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, H.; Tong, Y.; Wen, D.; Xia, X.; Wang, H.; Luo, Y.; Barcelo, D. Response of soil enzyme activities and bacterial communities to the accumulation of microplastics in an acid cropped soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Q. Effects of microplastics on greenhouse gas emissions and the microbial community in fertilized soil. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Diao, C.; Cui, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Hu, M.; Xu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Haider, G.; DongYang, D.; ShengdaoShan, S.; Chen, H. Unravelling the influence of microplastics with/without additives on radish (Raphanus sativus) and microbiota in two agricultural soils differing in pH. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, P.; Tan, W.; Yu, H. Effects of different concentrations and types of microplastics on bacteria and fungi in alkaline soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 229, 113045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Wang, X.; Luo, X.; Liu, G.; Zheng, H. Effects of polystyrene microplastics on the fitness of earthworms in an agricultural soil. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 61, 012148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, B.; Russell, C.W.; Green, D.S. Effects of microplastics in soil ecosystems: above and below ground. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11496–11506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Qiao, Y.; Klobucar, G.; Li, M. Toxicological effects of polystyrene microplastics on earthworm (Eisenia fetida). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Tang, R.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ei-Naggar, A.; Du, J.; Bu, A.; Yan, Y.; Lu, X.; Cai, Y.; Chang, S.X. Transcriptomic and metabolic responses of earthworms to contaminated soil with polypropylene and polyethylene microplastics at environmentally relevant concentrations. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 128176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; Song, X.; Li, M.; Yu, Y. Size effects of microplastics on accumulation and elimination of phenanthrene in earthworms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Ge, Y.; Yue, S.; Zhao, L.; Qiao, Y. Microplastics aggravate the joint toxicity to earthworm Eisenia fetida with cadmium by altering its availability. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 142042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Lu, S.; Hu, J.; Cao, C.; Xie, B.; Shi, H.; He, D. Polystyrene (nano)microplastics cause size-dependent neurotoxicity, oxidative damage and other adverse effects in Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5((8)), 2009–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. W.; Waldman, W. R.; Kim, T.-Y.; M.C.; Rillig, M. C. Effects of different microplastics on nematodes in the soil environment: Tracking the extractable additives using an ecotoxicological approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54((21)), 13868–13878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, D.; Jeong, S.W.; An, Y.J. Size-dependent effects of polystyrene plastic particles on the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as related to soil physicochemical properties. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. W.; An, Y.-J. Edible size of polyethylene microplastics and their effects oningtail behavior. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Zhu, D.; Qiao, M. Effects of polyethylene microplastics on the gut microbial community, reproduction and avoidance behaviors of the soil springtail, Folsomia candida. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 247, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. W.; An, Y.-J. Soil microplastics inhibit the movement of springtail species. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Xu, M.; Wang, L. Cyto–genotoxic effect causing potential of polystyrene micro-plastics in terrestrial plants. Nanomaterials 2022, 12((12)), 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Yang, X.; Riksen, M.; Xu, M.; Geissen, V. Response of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) growth to soil contaminated with microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Aqeel, M.; Khalid, N.; Nazir, A.; Alzuaibr, F.M.; Al-Mushhin, A.A.M.; Hakami, O.; Iqbal, M.F.; Chen, F.; Alamri, S.; Hashem, M.; Noman, A. Effects of microplastics on growth and metabolism of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Tang, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, Q. Microplastics in soil-plant system: effects of nano/microplastics on plant photosynthesis, rhizosphere microbes and soil properties in soil with different residues. Plant Soil 2021, 462, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, R.; Zhao, Y.; Geng, J.; Wang, G. Physiological responses of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) to microplastic pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 30306–30314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Gao, M.; Qiu, W.; Song, Z. Uptake of microplastics by carrots in presence of As (III): combined toxic effects. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 411, 125055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Pearce, C.I.; Sanguinet, K.A.; Hu, D.; Chrisler, W.B.; Kim, Y.-M.; Wang, Z.; Flury, M. Polystyrene nano-and microplastic accumulation at Arabidopsis and wheat root cap cells, but no evidence for uptake into roots. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 1942–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.P. Microplastics in freshwater systems: a review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfella, R.; Prattichizzo, F.; Sardu, C.; et al. Microplastics and nanoplastics in atheromas and cardiovascular events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, E. S.; Okoye, C. O.; Atakpa, E.O.; Ita, R. E.; Nyaruaba, R.; Mgbechidinma, C. L.; Akan, O. D. Microplastics in Agroecosystems-Impacts on Ecosystem Functions and Food Chain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 177, 105961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Machado, A.A.; Horton, A.A.; Davis, T.; Maaß, S. Microplastics and their effects on soil function as a life-supporting system. In Microplastics in Terrestrial Environments. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; He, D., Luo, Y., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Berlin, Germany, 2020; Volume 95, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, S.; Rathikannu, S.; Katharine, S. P.; Lindsay Kimdesa, R.; Marak, L. K. R.; Alshehri, M. Beyond the surface: Microplastic pollution its hidden impact on insects and agriculture. Phy. Chem. Earth 2024, 135, 103663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-Z.; Zhu, D.; Lindhardt, J.H.; Lin, S.-M.; Ke, X.; Cui, L. Long-term fertilization history alters effects of microplastics on soil properties, microbial communities, and functions in diverse farmland ecosystem. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55((8)), 4658–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Q.; Shen, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, S.-C; Li, Y. Effects of different microplastic types on soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, and bacterial communities. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 286, 117219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xing, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Guo, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Jiang, B. The effect of polyvinyl chloride microplastics on soil properties, greenhouse gas emission, and element cycling-related genes: Roles of soil bacterial communities and correlation analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, H.; Zhou, J.; Marshall, M.R.; Chadwick, D.R.; Wen, Y.; Jones, D.L. Microplastics in the agroecosystem: are they an emerging threat to the plant-soil system? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 107926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, K.; Xu, D.; Gao, B. Microplastics alter CO2 emissions in the soils of the water fluctuation belt of the Three Gorges Reservoir in China. Cell Rep. Sustain. 2025, 2, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, A.; Meyer, N.; Jakobs, A.; Bartnick, R.; Lueders, T.; Lehndorff, E. Biodegradable microplastic increases CO 2 emission and alters microbial biomass and bacterial community composition in different soil types. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 182, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Bu, N.; Liu, X.; Sun, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, T.; Chu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, X.; Li, Z. Stimulated soil CO2 and CH4 emissions by microplastics: A hierarchical perspective. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 194, 109425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zha, S.; Qiu, T.; Cuia, Q.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Huang, M.; Zhan, A.; Fang, L. Interaction of microplastics with heavy metals in soil: Mechanisms, influencing factors and biological effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. Characterization of microplastics and the association of heavy metals with microplastics in suburban soil of central China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Biswas, C.; Banerjee, S.; Guchhait, R.; Adhikari, M.; Chatterjee, A.; Pramanick, K. Interaction of plastic particles with heavy metals and the resulting toxicological impacts: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 60291–60307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Yang, W.; Cheng, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Jiao, W.; Sun, Y. Adsorption characteristics of cadmium onto microplastics from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Ma, X.; Song, Y.; Zuo, S.; Li, H.; Deng, W. A critical review on the interactions of microplastics with heavy metals: Mechanism and their combined effect on organisms and humans. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 788, 147620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Xia, Y.; Jin, X.; Sun, D.; Luo, D.; Wei, W.; Yang, Q.; Ding, J.; Lv, M.; Chen, L. Influence of microplastics on the availability of antibiotics in soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, H.; Valverde, M. G.; Morales, M.M.; Hernando, M.D.; Aguilera del Real, A.M.; Fernandez- Alba, A.R. Exploring sorption of pesticides and PAHs in microplastics derived from plastic mulch films used in modern agriculture. Chemosphere 2023, 333, 138959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Jeyakumar, P.; Wang, Z.; Sun, S.; Qiu, T.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, M.; Wang, H.; Fang, L. Unveiling the impacts of microplastics on cadmium transfer in the soil-plant-human system: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rong, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yuan, C.; Wang, L.; Sun, H. LDPE microplastics affect soil microbial communities and nitrogen cycling. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgetti, L.; Spanò, C.; Muccifora, S.; Bottega, S.; Barbieri, F.; Bellani, L.; Castiglione, M. R. Exploring the interaction between polystyrene nanoplastics and Allium cepa during germination: Internalization in root cells, induction of toxicity and oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Yan, Y.; Doyle, E.; Zhu, C.; Jin, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, C.; He, H.; Zhou, D.; Gu, C. Microplastics altered soil microbiome and nitrogen cycling: The role of phthalate plasticizer. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 427, 127944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aralappanavar, V.K.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Bhatnagar, A.; Praveena, M.S.; Li, Y.; Paller, M.; Adyel, T.M.; Rinklebe, J.; Bolan, N.S.; Sarkar, B. Effects of microplastics on soil microorganisms and microbial functions in nutrients and carbon cycling – A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smídova, K.; Selonen, S.; van Gestel, C.A.M.; Fleissig, P.; Hofman, S. Microplastics originated from agricultural mulching films affect enchytraeid multigeneration reproduction and soil properties. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, H.; Bello, U.; IbrahimTafida, U.; Garba, Z. N.; Galadima, A.; Lawan, M. M.; Abba, S. I.; Qamar, M. Harnessing bio and (Photo)catalysts for microplastics degradation and remediation in soil environment. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 370, 122543. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Ma, Y.; Shan, Y.; Song, X.; Wang, D.; Ren, X.; Hu, H.; Cui, J.; Yan Ma, Y. Exploring the potential of biochar for the remediation of microbial communities and element cycling in microplastic-contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2024, 362, 142698. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.Q.; Xiao, M.R.; Zhang, G.S. The persistent impacts of polyester microfibers on soil bio-physical properties following thermal treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, B.-J.; Zhu, Z.-R; Li, W.-H.; Yan, X.; Wei, W.; Xu, Q.; Xia, Z.; Dai, X.; Su, J. Microplastics mitigation in sewage sludge through pyrolysis: the role of pyrolysis temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, 7, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, J. Microplastics in soils during the COVID-19 pandemic: Sources, migration and transformations, and remediation technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883, 163700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekanayaka, A. H.; Tibpromma, S.; Dai, D.; Xu, R.; Suwannarach, N.; Stephenson, S. L.; Dao, C.; Karunarathna, S. C. A review of the fungi that degrade plastic. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidoyin, K.C.; Hwang, S,K; Hong, J-K.; Jho, E.H. Biodegradation of low-density polyethylene microplastics by Fusarium and Penicillium strains isolated from agricultural soil mulched with polyethylene film. J. Environ. Manage. 2025, 394, 127477. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Wan, C.; Wang, Y.; Zou, L.; Peng, L.; Ye, L..; Li, Q. Study on the degradation efficiency and mechanism of polystyrene microplastics by five kinds of edible fungi. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Kolvenbach, B.; Corvini, N.; Wang, S.; Tavanaie, N.; Wang, L.; Ma, Y.; Scheu, S.; Corvini, P. F.-X.; Ji, R. Mineralisation of 14C-labelled polystyrene plastics by Penicillium variabile after ozonation pre-treatment. New Biotechnol. 2016, 38, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Harrat, R.; Bourzama, G.; Sadrati, N.; Zerroug, A.; Burgaud, G.; Ouled-Haddar, H.; Soumati, B. A comparative study on biodegradation of low density polyethylene bags by a Rhizopus arrhizus SLNEA1 strain in batch and continuous cultures. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 3449–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyabama, M.; Boomija, R.V. Sathiyamoorthy, T.; Mathivanan, N.; Balaji, R. Mycodegradation of low-density polyethylene by Cladosporium sphaerospermum, isolated from platisphere. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8351. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Yin, Y.; Ni, Z.; Liu, J.; Gui, H.; Wu, D.; Wu, X.; Wang, L. The effective and green biodegradation of polyethylene microplastics by the screening of a strain with its degrading enzymes. Biochem. Eng. J. 2024, 210, 109429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Luz, J. M.R.; Paes, S.A.; Ribeiro, K.V.G.; Mendes, I.R.; Kasuya, M.C.M. Degradation of Green Polyethylene by Pleurotus ostreatus. PLoS ONE 2015, 10(6), e0126047. [Google Scholar]

- Prata, J. C.; da Costa, J. P.; Lopes, I.; Duarte, A. C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: an overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134455. [Google Scholar]

- Barai, D. P.; Gajbhiye, S. L.; Bhongade, Y. M.; Kanhere, H. S.; Kokare, D. M.; Raut, N. A.; Bhanvase, B. A.; Dhoble, S. J. Performance evaluation of existing and advanced processes for remediation of microplastics: A comprehensive review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, I. S.; Cheema, P. P. S. Microplastics—a review of sources, separation, analysis and removal strategies. In: Singh, H.; Singh Cheema, P.P.; Garg, P. (eds) Sustainable Development Through Engineering Innovations. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, vol 113. Springer, Singapore, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Gertsen, H.; Peters, P.; Salanki, T.; V. Geissen, V. A simple method for the extraction and identification of light density microplastics from soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 1056–1065. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hu, X.; Wang, S.; Guan, Z.; Yuan, C.; Tian, C.; Luo, S. Biodegradable mulch films drive microbial divergence and heighten environmental risks. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 217, 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Chang, N.; Li, W.; Qu, Z.; Hao, T.; Arvola, L.; Graco-Roza, C.; Wang, Z. Impacts of polyglycolic acid (PGA) biodegradable mulch films on agricultural soils: Integrated responses of physicochemical properties, enzyme activities and microbial diversity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayana, K.V.; Vishwanath, T. Development and characterization of biodegradable PVA-Starch electrospun films for potential mulch applications. Chem. Data Collect. 2025, 60, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Zhao, R.; Ning, R.; Shang, X.; Zhang, B.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, P.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Xie, J.; Xu, J. PBAT/PPCP biodegradable mulching films with enhanced weatherability and water barrier properties for increased cotton yields. Adv, Agrochem. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, M.; Kazmi, S. S. H.; Pastorino, P.; Saqib, H. S. S.; Yaseen, Z. M.; Hanif, M. S.; Islam, W. Microplastics in agroecosystems: Soil-plant dynamics and effective remediation approaches. Chemosphere 2024, 362, 142641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | Source | Crop type | Polymer type | Abundance | Color | Shape | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chengguan, China | Mulching films | Greenhouse crops | PE | 611,11 items/kg | Black | Fiber | (Bai et al., 2024) |

| Liaocheng, China | Plastic inputs, organic fertilizers and irrigation water | Vegetable crops | PE | 900 items/kg | Transparent | Fiber | (Xu et al., 2025) |

| Liaocheng, China | Plastic inputs, organic fertilizers and irrigation water | Orchard crops | PE | 615 items/kg | Transparent | Fiber | (Xu et al., 2025) |

| Gampaha, Sri Lanka | Irrigation water, mulching materials, organic fertilizers, inputs from air drift | Paddy fields | PET | 518 items/kg | Blue | Fiber | (Athavuda et al., 2024) |

| Gampaha, Sri Lanka | Irrigation water, mulching materials, organic fertilizers, inputs from air drift | Vegetable crops | PET | 433 items/kg | Black | Fiber | (Athavuda et al., 2024) |

| Gampaha, Sri Lanka | Irrigation water, mulching materials, organic fertilizers, inputs from air drift | Coconut crops | PET | 57 items/kg | Blue | Fiber | (Athavuda et al., 2024) |

| Nakhom Pathom, Thailand | Mulching films | Greenhouse crops | PDVF1 | 620 items/kg | NA2 | NA | (Boonsong, et al., 2024) |

| Murcia, Spain | Mulching films | Vegetable crops | Light density polyethylene | 2116 items/kg | NA | NA | (Beriot et al., 2021) |

| Mellipilla, Chile | Sewage sludge application | Corn | NA | 4.38 mg/kg | NA | Fiber | (Corradini et al., 2019) |

| Jiangsu, China | Sewage sludge application | NA | Polystyrene acrylate | 149.2 items/kg | NA | Fiber | (Yang et al., 2021) |

| Valencia, Spain | Sewage sludge application | Cereals | Light density polyethylene | 2130 items/kg | NA | Fragment | (Van den Berg et al., 2020) |

| Moselle, Germany | Mulching film, grape protection nets, pheromone traps | Vineyard | PP | 4200 items/kg | NA | Fragment | (Klaus et al., 2024) |

| Study area | Polymer type | Potential effects | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hangzhou China | PE | Decline of Sphingomonadaceae and Xanthobacteraceae (soil bacterial communities) | Inhibition of the biodegradation of soil organic pollutants. | [96] |

| Berlin, Germany | PET | Limited plant growth | Reduced root colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, non arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal structures and mycorrhizal fungal coils | [17] |

| Langfang, China | LDPE | Inhibition of the abundance of Bacteroidetes | Limited degradation of complex organic matter in soil biosphere | [139] |

| Jinling, China | PS | Increased mortality of earthworms | Inhibition of organic matter decomposition and maintenance of soil structure | [100] |

| Kaifeng, China | PS | Cellular root toxicity | Inhibition of the absorption of water and nutrients by plants | [112] |

| Beichen, China | PS | Reduced photosynthetic activity of plants | Limited plant growth | [115] |

| Tianjin, China | PS | Human health risks | The migration of PS-MP particles in carrot roots (grown in hydroponic systems) is facilitated by the presence of arsenic (As) in the hydroponic solution | [117] |

| Salerno, Italy | PE, PVC | High risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, | These findings are based on clinical observations | [120] |

| Sanming,, China | LDPE | Reduction of soil pH | MPs alter cation exchange capacity | [125] |

| Pinggu, China | PVC | Disruption of soil GHG emissions | Enhanced CH4 emissions and soil CO2 emissions | [126] |

| Toxicity Mechanism | Polymer type | MP size | Exposed biological target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative stress | PS | 10μm | Rice plants | [114] |

| Oxidative stress | PVC | 10μm | Rice plants | [114] |

| Oxidative stress | PS | >100nm | Earthworms | [102] |

| DNA damage | PS | >100nm | Earthworms | [102] |

| Histopathological damage | PS | 1300nm | Earthworms | [102] |

| Disruption of cell division | PS | 100nm | Allium cepa | [112] |

| Cytotoxicity (reduction of mitotic index) | PS | 50nm | Allium cepa | [140] |

| Genotoxicity (induction of cytogenetic anomalies | PS | 50nm | Allium cepa | [140] |

| Leaching of additives | PVC | 150μm | Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus | [141] |

| Leaching of additives | PA, PP | 30μm | Xanthobacteraceae | [58] |

| Reactive oxygen species (ROS) | PS | 5 µm | Root carrots | [117] |

| Reference | Polymer | Fungus (strain if available) | Assay type | Main methods | Main quantitative result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [152] | Polystyrene (PS) films (¹⁴C-labelled) | Penicillium variabile | Laboratory (liquid/solid culture, radiotracer mineralization) | ¹⁴C radiotracer mineralization (measure ¹⁴CO₂), ozonation pre-treatment tested | Measured mineralization of ¹⁴C-PS by P. variabile; ozonation pretreatment significantly enhanced mineralization (quantitative ¹⁴C mineralization values reported in paper). |

| [151] | Polystyrene (PS) microplastics | Edible fungi tested, Pleurotus ostreatus highest performer (and others) | Lab assays (liquid and soil-like tests) | SEM, FT-IR, enzyme assays, CO₂ measurement | Average degradation ~7.49% after 50 days; Pleurotus ostreatus highest ~16.17 ± 8.87% (50 d). |

| [153] | LDPE films | Rhizopus arrhizus SLNEA1 and other fungi | Batch / continuous culture (liquid / film exposure) | Weight loss measurements, SEM, chemical characterization | ~23.8% weight loss after 30 days (R. arrhizus SLNEA1, batch culture); continuous culture >23% after 90 days (paper reports time course and comparative data). |

| [154] | LDPE films | Cladosporium sphaerospermum and other isolates | Laboratory (solid film exposure in culture) | Weight loss, SEM, FT-IR, CO₂ evolution | Reported rapid weight loss in some isolates (examples in paper: some isolates produced measurable weight loss within days; literature comparisons include 35–38% in 90 days for some fungi). Exact per-isolate numbers in text/figures. |

| [155] | Polyethylene (PE) microplastics | Strain DL-1 (fungal isolate described in paper) | Lab incubation (microplastic suspension/solid assay) | Weight-loss method, electron microscopy, growth on PE as C source | Verified that strain degraded PE MPs by measurable weight loss (paper reports % weight loss and structural evidence). |

| [156] | Green polyethylene (GP) — bio-based PE | Pleurotus ostreatus (PLO6) | Solid substrate / fungal culture (soil-relevant substrate with GP) | Weight (dry mass) loss of substrate, FT-IR, mechanical property changes | Reported surface oxidation and loss of dry mass of GP after fungal treatment; quantitative mass-loss and changes in mechanical properties presented in the paper (examples: significant substrate mass reduction and evidence of polymer oxidation). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).