1. Introduction

In Cody (2025) [

1], Schwarzschild collapse was analyzed using a curvature-based measure of substrate stress defined by

, where

K is the Kretschmann scalar. Within that framework the classical singularity does not represent a physical endpoint of collapse; instead, the continuum description fails once the invariant

reaches a critical value

, interpreted as a threshold on the curvature that the substrate can sustain. Because the Schwarzschild invariant depends only on the radial coordinate, this condition produces a spherical boundary at a finite radius

, beyond which the geometric description ceases to be physically meaningful. The construction does not modify Einstein’s field equations and requires no exotic matter, since the failure arises from geometric rather than dynamical constraints.

Astrophysical black holes, however, are rotating, and the appropriate exterior solution is the Kerr geometry. Rotation introduces anisotropy into the curvature because the Kerr invariants depend on both

r and

. This raises a natural question about the onset of continuum failure in the rotating case. The invariant

may reach the threshold

first near the equatorial region, near the rotational axis, or at some intermediate latitude, and there is no reason to expect the failure boundary to remain spherical. As will be shown, the anisotropic curvature of the Kerr geometry produces a failure surface that is oblate rather than spherical, with the largest deviation occurring near the equatorial plane. Determining this structure requires the explicit form of the Kerr Kretschmann scalar, which is known in closed form from standard geometric treatments [

2]. The purpose of this paper is to compute

for the Kerr spacetime, to impose the condition

, and to solve for a latitude-dependent radius

that marks the boundary at which the continuum description fails. The resulting surface is compared with the Schwarzschild value

, with the Kerr horizons

, and with the structure of the ring singularity at

on the equatorial plane. The analysis shows how rotation modifies the onset of continuum failure and clarifies the geometric structure expected inside rotating collapse.

2. Kerr Geometry Setup

The rotating vacuum solution of Einstein’s field equations is described by the Kerr metric in Boyer-Lindquist coordinates

, with mass parameter

M and angular momentum per unit mass

a. The metric takes the standard form

where the functions

and

are defined explicitly by

The signature convention is , and units are chosen such that . These quantities appear in all curvature components and determine the geometric structure of the spacetime. The coordinate domain is and , with the azimuthal angle and unrestricted time coordinate t. The invariance of the geometry under the reflection reduces the physically distinct domain to for the curvature analysis that follows. This reduction applies specifically to scalar invariants such as the Kretschmann scalar, since these quantities depend on and therefore remain unchanged under . The full metric is defined on the entire interval , but no loss of generality occurs when restricting scalar curvature computations to the half-interval.

Several geometric structures play a central role in Kerr spacetime. The roots of

determine the horizon radii

which exist only when

. The outer value

is the event horizon and the inner value

is the Cauchy horizon. Both positions correspond to coordinate singularities rather than curvature singularities, and they are identified through the vanishing of

rather than the vanishing of

. The ergosurface is defined by the condition

, which occurs when

. Because

depends on

, the ergosurface is not spherical but bulges outward near the equatorial region. The ergoregion is the domain in which the Killing vector

becomes spacelike, and its boundary depends smoothly on

. This structure is distinct from the event horizon and will not play a direct role in the failure condition, but its geometry reinforces the fact that rotation introduces anisotropy into all curvature quantities. The curvature singularity of the Kerr solution is not pointlike. At

, the quantity

reduces to

, which vanishes only when

. This produces the ring singularity familiar from standard treatments of Kerr geometry. Along the rotation axis, where

or

, the expression

remains nonzero for all

, and the metric components remain finite except at the horizon positions. This property will be relevant when evaluating the curvature invariant, since the vanishing of

governs the divergence structure of the Kretschmann scalar. In particular, the fact that

does not vanish on the axis ensures that the stress invariant

remains finite at

along the axis, whereas it diverges on the equatorial ring. This axial regularity is a geometric feature unique to rotating solutions and distinguishes the Kerr interior structure from the Schwarzschild case.

3. Kerr Kretschmann Scalar

The Kretschmann scalar encodes the local curvature strength of the Kerr spacetime. The expression is algebraically nontrivial but can be factored into explicit polynomial components. The scalar is analyzed here in its canonical form, followed by expansion of numerator polynomials, limiting case evaluations, and sign-structure implications.

Canonical form. The expression for the Kretschmann scalar in Kerr geometry is given by Henry (2000) [

3] as

with

. Notation follows Carroll (2004) [

4] and Poisson (2004) [

5].

Polynomial expansion. The squared term expands directly:

Substituting into the bracket yields

The numerator becomes

The denominator remains factored for singularity structure analysis.

Limiting cases. The following limiting behaviors verify the expression’s physical consistency:

Schwarzschild limit (

):

matching the Schwarzschild scalar curvature [

6].

Equatorial plane (

): At

,

recovering the Schwarzschild form since the equatorial plane exhibits no frame-dragging contribution to radial curvature.

Polar axis (

): At

,

, and the numerator remains finite:

Ring singularity (

): At

,

, the function

, and

confirming scalar curvature divergence at the ring singularity [

2].

Sign-change surfaces. The Kretschmann scalar is not sign-definite in Lorentzian signature. The numerator vanishes when either of the following conditions is met:

These surfaces define transitions between

and

regions. The sign structure follows directly from the factorized form of the numerator [

7].

Physical implications. Negative values of

K require using the modulus:

Numerical schemes must detect and track zero-crossings of

K to ensure proper root-finding for curvature divergence thresholds and failure conditions.

4. Substrate Stress Field

The stress field is defined as the local curvature magnitude extracted from the Kretschmann scalar. It acts as a diagnostic for continuum-level failure in the relativistic substrate model and encodes directional dependence from the Kerr geometry.

Definition. The field is defined pointwise in terms of the Kretschmann scalar:

This expression ensures that

remains real-valued even when

K is negative, as occurs in certain angular regions of Kerr spacetime [

7].

Interpretation. The function

encodes the intrinsic curvature stress induced by the gravitational field. The quantity has units of inverse length squared:

A critical stress threshold

is used to indicate continuum failure, consistent with substrate stress models [

1,

8].

Contrast with Schwarzschild. In the Schwarzschild solution, the Kretschmann scalar depends only on the radial coordinate, yielding

This function is monotonic in

r, and the condition

yields a unique failure radius

. In contrast, the Kerr geometry produces an angularly anisotropic curvature field

, and the failure condition

defines a surface in spacetime rather than a single radial value. Anisotropy is a direct result of spin-coupled curvature distortion [

2].

Behavior near special directions. The stress field exhibits qualitatively distinct behavior along principal directions of the geometry:

5. Failure Condition:

Failure is defined to occur when the local stress field exceeds a critical threshold:

This yields an equation that locates the failure surface implicitly in the Kerr spacetime.

Core equation. By squaring both sides, the failure condition becomes:

This defines a hypersurface in the

plane where curvature stress reaches the failure threshold.

Explicit substitution. Using the expanded expression for

from

Section 3, the equation becomes:

This step retains the full polynomial structure in both numerator and denominator. No compression or factor cancellation is applied, as the full functional form is required for numerical root detection.

The failure equation is a sixth-order rational expression in r, with angular dependence through and . The absolute value introduces a piecewise structure based on the sign of the original curvature scalar. The equation is strongly nonlinear and cannot be solved analytically for . Numerical root-finding is therefore necessary at each value of . The equation is nonlinear in both numerator and denominator, and no algebraic inversion is available.

The equation is only evaluated within the physically meaningful region:

The lower hemisphere is excluded by symmetry. The singular ring region, where

, must be avoided, as the curvature diverges there and the equation becomes ill-defined. This expression for

was introduced in

Section 3. The singularity occurs precisely at

,

.

Root structure. Because the equation includes an absolute value, valid solutions for

r may occur on either side of the zero sets of the Kretschmann scalar. From

Section 3, these zero sets occur when:

Numerical solvers must detect crossings of these surfaces to properly bracket roots. Root isolation requires careful domain scanning and piecewise evaluation to ensure that both positive and negative regions of

K are included. The absolute value enforces continuity in

, but the underlying rational function is sign-sensitive. Bracketing methods must be robust to this discontinuity in the sign of the numerator. In addition, regions near the singularity at

may require exclusion or adaptive resolution to prevent divergence in numerical evaluation.

6. Numerical Reconstruction of Failure Surface

The critical radius function defines the locus at which the local stress reaches the failure threshold . This section describes the reconstruction of this failure surface using direct numerical evaluation of the curvature field.

Precomputed subexpressions. The following auxiliary functions are defined to simplify repeated evaluation of the stress field:

The function

is strictly positive for all

,

, except at the singular ring

,

, where it vanishes and the curvature diverges. The Kretschmann scalar and derived stress field are:

Failure function. The failure condition is formulated as the root of the scalar function:

The critical radius

is defined implicitly as the solution to

for fixed

. This is equivalent to:

Numerical method. The reconstruction proceeds as follows:

Select a uniform angular grid in the range .

For each , define a radial search interval , where the lower bound excludes the singular ring (), and the upper bound extends beyond both Kerr horizons.

Evaluate at discretized points within this interval. Identify adjacent pairs where F changes sign, indicating a root bracket. The function F is continuous in r across this domain (except at the singularity), and therefore standard bracketing methods such as bisection are applicable.

Apply a root-finding method (e.g., bisection or Ridder’s algorithm) to solve to desired precision.

In cases where the sign change occurs near known curvature zero sets (

Section 3), ensure numerical continuity across regions where the sign of

flips. Discontinuities in the numerator sign structure require robust bracketing.

The result is a discrete set of angular-radius pairs forming a sampled representation of the failure surface. This data can be used for both quantitative and geometric comparisons:

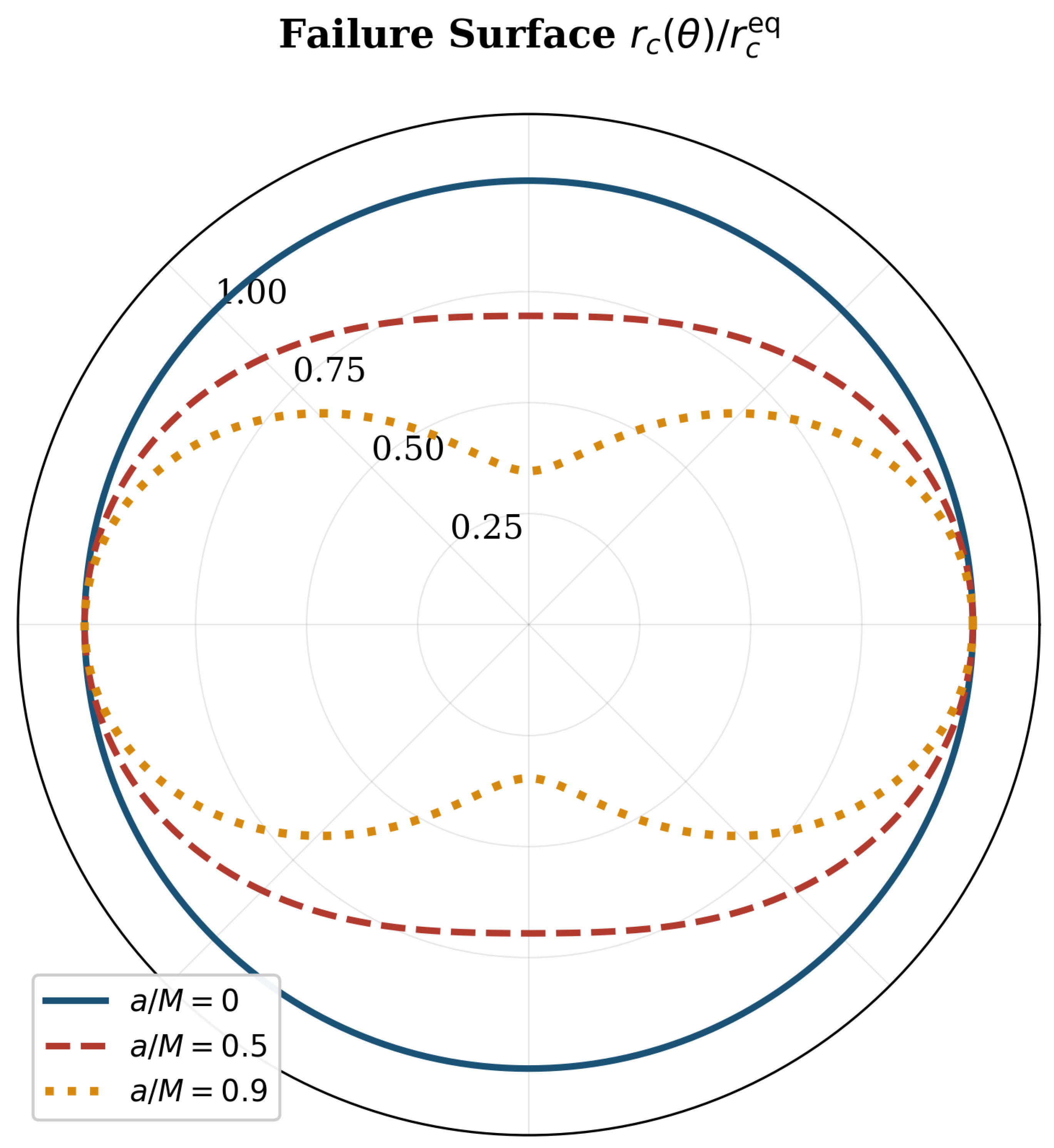

A polar plot of visualizes the anisotropic structure of the failure surface.

-

The surface may be compared directly to the Kerr horizons:

These are shown for reference only; the failure surface is determined independently by the curvature field and does not coincide with causal boundaries.

7. Geometry of the Failure Surface

The failure surface defined by exhibits distinct geometric structure due to the anisotropic curvature distribution in Kerr spacetime. This section characterizes its shape, topology, and relation to known features of the Kerr geometry.

Overall topology. The surface

is rotationally symmetric about the spin axis of the black hole. It does not form a sphere unless the spin parameter vanishes

, in which case the spacetime reduces to Schwarzschild and the failure surface becomes a sphere of radius

. For all

, the surface remains simply connected and continuous, not toroidal or self-intersecting. Its anisotropic geometry reflects the spin-induced curvature distortion described in [

7,

9].

Equatorial behavior. At the equator

, the Kretschmann scalar diverges at the ring singularity (

), and stress magnitudes are maximized. This results in the failure surface extending furthest outward near the equator:

This agrees with curvature-driven stress peaking along the plane of rotation, consistent with analyses of curvature invariants in spinning spacetimes [

3,

10].

Axial behavior. Along the polar axis

, the curvature scalar remains finite even as

, and the stress field

remains bounded. This causes the failure radius to be minimized along the spin axis:

This behavior contrasts with isotropic models and highlights the axis-protecting structure of Kerr curvature. A result consistent with differential behavior of scalar invariants noted in [

8,

10].

Shape characterization. The resulting failure surface is oblate: the radius at the equator exceeds that at the pole. Define the polar compression ratio:

This provides a coordinate-invariant measure of axial flattening due to spin-induced curvature distortion. Note that this differs from the standard geodetic flattening convention, which typically uses the equatorial radius in the denominator. The shape resembles that of isocurvature contours in Kerr-Newman geometry, though it is not directly tied to horizons or ergosurfaces [

4,

5].

Extremal limit behavior. As the spin approaches extremality , the anisotropy of the curvature field increases significantly:

The equatorial region experiences sharply increasing curvature, pushing the failure surface further outward.

The axis remains regular and curvature-limited, preserving the protected behavior at .

The failure surface may approach or intersect the outer horizon , depending on the threshold . In extremal cases, partial overlap may occur.

These effects parallel the known amplification of frame-dragging and equatorial curvature in the extremal Kerr geometry [

2,

11].

Comparison to Kerr horizons. The reconstructed surface

can be compared against the Kerr horizons:

Three distinct regimes are possible:

: failure surface lies entirely outside the event horizon.

: failure occurs inside the ergoregion but outside the Cauchy horizon.

: failure occurs in a deeply sub-horizon region, not causally accessible from outside.

These comparisons provide geometric constraints on where the continuum description may break down and are consistent with the stress-based failure threshold model introduced earlier [

1].

Taken together, these features establish that the condition defines a smooth, closed surface whose shape is determined entirely by the anisotropic curvature distribution of the Kerr geometry. While the analytic expressions clarify how the stress field behaves along principal directions, the global structure of the failure surface is most transparently illustrated in a meridional cross–section. The figure below visualizes for several spin parameters, emphasizing the transition from the spherical Schwarzschild case to the increasingly oblate geometry that emerges as the rotation approaches extremality.

Figure 1.

Meridional cross-section of the failure surface for several Kerr spin parameters, normalized to the equatorial value. The Schwarzschild case () produces a spherical boundary. Increasing spin introduces oblateness: the failure radius is largest at the equator and smallest along the rotation axis, reflecting the anisotropic curvature distribution of the Kerr geometry.

Figure 1.

Meridional cross-section of the failure surface for several Kerr spin parameters, normalized to the equatorial value. The Schwarzschild case () produces a spherical boundary. Increasing spin introduces oblateness: the failure radius is largest at the equator and smallest along the rotation axis, reflecting the anisotropic curvature distribution of the Kerr geometry.

8. Physical Interpretation

The existence of a stress-limited surface

implies that classical gravitational collapse in a rotating configuration may terminate at a finite, anisotropic boundary. Below this surface, the curvature stress exceeds the critical threshold

, and the continuum description of the spacetime ceases to be valid. The internal geometry can no longer be described by the Kerr solution, and the evolution of the system may require a discrete or quantum extension of the underlying degrees of freedom [

8,

12]. The traditional Kerr ring singularity occurs at

, corresponding to

,

. In the presence of a finite failure threshold, the stress field

diverges before this point is reached. As a result, no region of spacetime reaches

, and the ring singularity is never physically realized. The failure surface thus functions as a natural regulator that prevents access to classically pathological zones, without invoking exotic energy conditions.

The rotation-induced curvature anisotropy causes collapse to terminate at different radii depending on direction. Near the equator, curvature invariants diverge more strongly, and the failure radius

is largest. Near the poles, curvature remains bounded and collapse proceeds deeper. This produces an oblate failure geometry, compressed along the spin axis and extended along the equatorial plane. This anisotropic internal structure is a direct consequence of the spin-coupled curvature distribution encoded in the Kerr geometry [

2,

9,

10].

If the critical stress corresponds to a curvature scale attainable in realistic gravitational collapse, the presence of a finite failure surface may have observable consequences:

These implications remain speculative and depend on the value of

, which may be set by quantum gravity or sub-continuum physics. No definite astrophysical predictions are made here. Beyond these phenomenological considerations, several approaches in quantum gravity have proposed mechanisms to avoid singularities inside black holes. These include fuzzball geometries in string theory [

15], gravastar models with phase transitions [

16], and polymer quantization in loop quantum gravity [

17]. The present model differs in that it does not introduce exotic matter, boundary matching, or fundamental discretization by hand. Instead, singularity avoidance emerges from a classical geometric failure condition defined within the continuum itself, rooted in the divergence of the curvature stress field.

9. Towards Deriving the Stress Threshold

The curvature stress threshold introduced in this framework defines the limit beyond which the continuum description of spacetime ceases to be valid. While this paper treats as a phenomenological parameter, it is natural to ask whether its value can be estimated or motivated from quantum gravitational considerations. This section outlines candidate approaches that may constrain or motivate based on known quantum geometry models.

One natural assumption is that the breakdown of the continuum occurs when curvature invariants reach the Planck scale. The Kretschmann scalar

K has units of inverse length to the fourth power, i.e.,

which implies that

has units

By dimensional analysis, a natural quantum gravity curvature scale is set by the Planck length:

The associated Planck-scale stress threshold is then:

This provides a baseline estimate. The corresponding Kretschmann scalar at failure would be:

This value is not derived from any specific quantum gravity model, but it is consistent with upper bounds on curvature inferred in polymer quantized spacetimes [

17,

18].

An alternative motivation comes from entropy density. The Bekenstein-Hawking entropy for a black hole is:

and the area

A scales with

. A local entropy density

then scales as:

while the stress invariant scales as:

This suggests a correspondence between local entropy density and the magnitude of the stress invariant near gravitational collapse, though this is not a formal derivation. Similar ideas appear in holographic bounds on curvature from black hole thermodynamics [

19]. Another route involves the observation that several quantum gravity proposals, including loop quantum gravity and causal set theory, posit that the Riemann tensor components or curvature invariants cannot exceed a maximal value [

20,

21]. In these models, there exists a maximum curvature scale

of order:

where

is the fundamental length scale of the theory. If the failure threshold coincides with this limit, then:

aligning with the phenomenological model adopted here. This again provides a dimensional scaffold rather than a unique derivation.

Each of these approaches remains speculative. No complete derivation of from first principles currently exists. However, the convergence of different lines of reasoning dimensional analysis, entropy scaling, and maximum curvature arguments supports the plausibility of treating as a fundamental cutoff parameter linked to the microstructure of spacetime. A rigorous derivation would require embedding the substrate stress framework into a specific quantum gravitational formalism. In future work, this direction could be pursued by examining how discrete structures in loop quantum gravity, causal sets, or string theory respond to increasing curvature. If the continuum limit of such a theory yields a stress field matching in the weak-field limit but breaks down at a consistent threshold, this would provide the desired derivation. Until then, the present framework provides a testable, covariant model for how classical geometry may fail in high-curvature regimes.

Having outlined the conceptual and quantum-geometric motivations for treating as a fundamental curvature threshold, it is natural to ask whether such a failure surface can produce observable consequences. In particular, if the region behaves as a reflective or non-geometric interior, then gravitational waves interacting with this boundary may generate time-delayed echoes in the post-merger signal of rotating black hole binaries. The remainder of this section examines the observational implications of this possibility. The curvature-based failure surface defined by the condition introduces several potential observational and conceptual implications. One such implication arises from the possibility that gravitational waves encountering the failure surface may reflect, giving rise to time-delayed echoes in the post-merger signal of black hole coalescence events.

To estimate the echo delay time, recall that the substrate model predicts the scalar curvature stress invariant scales as

Equating

to the critical threshold

yields

Here

M is understood to be expressed in geometric units, where

. In conventional SI/CGS units the corresponding expression is

which reduces to the form used above once geometric units are adopted. Because the echo delay depends only logarithmically on the ratio

, the numerical estimate below is insensitive to this conversion.

For a black hole of mass

and Planck length

, the failure radius is approximately

Taking the outer Kerr horizon to be at

, the round-trip delay time between the horizon and the failure surface is estimated as

Using

, and the conversion factor

, the delay time is

This timescale lies within the observable band of current interferometers such as LIGO and Virgo. Unlike other exotic compact object (ECO) models that assume a spherically symmetric reflective surface [

13,

22,

23], the failure surface in this framework is anisotropic, with

taking an oblate form in the Kerr geometry. As a result, different angular modes particularly those with large

reflect from deeper radii and exhibit longer delays, while polar modes reflect earlier. This angular structure implies a measurable spin-dependent spread in the echo signal, providing a unique falsifiable signature of the failure surface model. Beyond observational consequences, the presence of a finite-curvature failure surface alters the conceptual structure of the interior. In classical general relativity, curvature diverges at

and geodesics terminate at the singularity. Here, the breakdown occurs at

, providing a finite-curvature surface at which the continuum approximation fails. The region beyond

lacks a well-defined metric and may correspond to a non-geometric or discrete regime. While no specific microphysical model is proposed, this construction reframes the endpoint of classical evolution as a physical information boundary, rather than a mathematical divergence [

1,

11]. Such a boundary may provide a new conceptual handle on the black hole information problem, though quantitative resolution requires further development.

For astrophysical Kerr black holes, the maximum attainable curvature along the spin axis remains many orders of magnitude below any reasonable value of the critical stress . Explicitly, the axial stress satisfies for stellar-mass and supermassive black holes, whereas a Planck-scale threshold corresponds to . Thus the condition always admits a finite solution for every latitude, ensuring that the failure surface forms a fully closed oblate surface rather than an open equatorial shell. This removes any ambiguity regarding the global topology of the surface and guarantees that the continuum termination encloses the would-be ring singularity at all spins.

10. Conclusions

The analysis presented here extends the curvature-based substrate stress framework from the Schwarzschild solution to the Kerr geometry. Using the exact Kerr Kretschmann scalar, the local stress invariant was evaluated and used to determine the locus at which the continuum description reaches a critical stress threshold . The resulting failure surface is intrinsically anisotropic: it reaches its maximal radius in the equatorial plane, where curvature diverges most strongly, and its minimal radius along the rotation axis, where the stress remains finite even at . Within this framework, the classical ring singularity at is never approached, as the curvature-stress threshold is encountered at a finite radius that functions as an internal geometric boundary. The structure obtained here reduces smoothly to the spherical failure radius derived in the Schwarzschild case, demonstrating that the substrate stress model behaves consistently across static and rotating spacetimes. The anisotropic surface also shows that rotation modifies the internal curvature landscape independently of the horizon structure, since its location need not coincide with either Kerr horizon.

Several avenues for future investigation follow. A full numerical reconstruction of across the parameter space would allow systematic comparison with other curvature scalars and with properties of geodesic motion. Extending the failure analysis to Kerr–Newman and Kerr–de Sitter geometries would test whether similar oblate structures arise in charged or cosmological settings. A more refined treatment of may be obtained by embedding the substrate model into quantum-gravity frameworks that posit upper bounds on curvature. Finally, the observational implications of anisotropic failure surfaces-including potential modifications to echo delays, mode-dependent reflection radii, and near-horizon propagation-justify dedicated time-domain simulations in nearly-Kerr backgrounds. Such signatures also provide a direct means by which future gravitational-wave observations could place empirical constraints on .

The results presented here indicate that the introduction of a finite curvature-stress threshold yields a coherent and covariant mechanism by which classical singularity formation in rotating collapse may be avoided. Further development of this framework may offer new insight into the internal structure of astrophysical black holes and the onset of non-classical geometric behavior at extreme curvature.

Author Contributions

This article is the sole work of the author.

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cody, M. A. Black Hole Singularities and the Limits of the Spacetime Continuum. Preprint.org

. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar, S. The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes; Oxford University Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, R. C. Kretschmann Scalar for a Kerr-Newman Black Hole. The Astrophysical Journal

. 2000, 535(1), 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S. M. Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity; Addison-Wesley, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Poisson, E. A Relativist’s Toolkit: The Mathematics of Black-Hole Mechanics; Cambridge University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, R. M. General Relativity; University of Chicago Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini, C.; Bini, D.; Capozziello, S.; Ruffini, R. Second Order Scalar Invariants of the Riemann Tensor: Applications to Black Hole Spacetimes

. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2002, 11, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenev, T.; Horstemeyer, M. F. The elastic nature of spacetime

. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2018, 27(12), 1850114. [Google Scholar]

- Bini, D.; Cherubini, C.; Jantzen, R. T.; Ruffini, R. Massless fields and scalar invariants of the Riemann tensor

. Progress of Theoretical Physics 2002, 107(5), 967–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D. N. Kerr–de Sitter black holes with scalar curvature invariants

. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2006, 23(18), 6239–6252. [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen, J. M.; Press, W. H.; Teukolsky, S. A. Rotating black holes: Locally nonrotating frames, energy extraction, and scalar synchrotron radiation

. The Astrophysical Journal 1972, 178, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, C.; Liberati, S.; Sonego, S.; Visser, M. Fate of gravitational collapse in semiclassical gravity

. Physical Review D 2011, 83(4), 041501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V.; Franzin, E.; Pani, P. Black holes and fundamental fields: Hair, echoes and shadows

. Living Reviews in Relativity 2019, 22(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarov, S. S.; Barkov, M. V.; Vlahakis, N.; Königl, A. Magnetic acceleration of ultrarelativistic jets in gamma-ray burst sources

. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2007, 380(1), 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S. D. The fuzzball proposal for black holes: An elementary review

. Fortschritte der Physik 2005, 53(7), 793–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, P. O.; Mottola, E. Gravitational vacuum condensate stars

. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101(26), 9545–9550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashtekar, A.; Pawlowski, T.; Singh, P. Quantum Nature of the Big Bang: Improved Dynamics

. Physical Review D 2006, 74(8), 084003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesto, L. Loop quantum black hole

. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2006, 23(18), 5587–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. The holographic principle

. Reviews of Modern Physics 2000, 74(3), 825–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. Minimal Length Scale Scenarios for Quantum Gravity

. Living Reviews in Relativity 2013, 16(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovelli, C.; Vidotto, F. Covariant Loop Quantum Gravity; Cambridge University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abedi, J.; Dykaar, H.; Afshordi, N. Echoes from the abyss: Evidence for Planck-scale structure at black hole horizons

. Physical Review D 2017, 96(8), 082004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V.; Hopper, S.; Macedo, C. F. B.; Palenzuela, C.; Pani, P. Gravitational-wave signatures of exotic compact objects and of quantum corrections at the horizon scale

. Physical Review D 2016, 94(8), 084031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).