1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

In contemporary process-oriented business environments, organizations increasingly rely on well-defined business processes to ensure operational efficiency and achieve strategic objectives. The adoption of Business Process Management (BPM) has become imperative for managing organizational complexity and adapting to dynamic market conditions [

1]. Alongside operational goals, however, organizations face mounting pressure to ensure their processes comply with a growing number of laws, regulations, and internal policies [

2]. Business Process Compliance (BPC), defined as the alignment of business process execution with these prescriptive documents [

3,

4], is crucial for risk management and maintaining stakeholder trust.

Concurrently, the technological landscape is rapidly evolving with the widespread adoption of Microservices Architecture (MSA) [

5] and Cloud Computing. While offering benefits in agility and scalability, these modern environments present significant challenges to traditional BPC approaches. The inherent characteristics of MSA/Cloud—including distribution, dynamism, polyglot persistence, and decentralized control—fundamentally clash with conventional, often centralized, compliance mechanisms. This clash manifests in several critical, unresolved problems:

Complex Cross-Service Auditing: Reconstructing a complete, reliable audit trail for a business process that traverses multiple, often ephemeral, microservices is non-trivial.

Slow Policy Adaptation: Traditional methods for updating compliance rules are too slow for the rapid deployment cycles common in MSA environments.

Impedance Mismatch: Centralized, heavyweight compliance tools create an impedance mismatch with the lightweight, decentralized paradigm of cloud-native microservices.

A systematic review of the state-of-the-art reveals that these issues contribute to persistent and significant research gaps. These include the “Last Mile” Problem of translating ambiguous legal text into executable rules, a “Broken Feedback Loop” between design-time analysis and runtime monitoring, and a prevalent lack of scalable and resilient Automated Verification capabilities in existing solutions. This research confronts the foundational challenge of holistically managing BPC within combined MSA/Cloud environments, a gap explicitly noted in recent literature surveys [

6,

7]

1.2. Research Objectives & Approach

The primary goal of this research is to design, develop, and evaluate a novel framework, BPC4MSA, specifically engineered for holistic Business Process Compliance (BPC) management, spanning the full lifecycle from design-time verification to resilient, asynchronous runtime auditing within integrated Microservices Architecture (MSA) and Cloud environments. This framework aims to address the problem and gap identified in

Section 1.1 by providing capabilities such as scalable compliance checking, runtime monitoring and auditing across distributed services, agile policy management, and seamless integration with cloud-native ecosystems.

To achieve this goal, this research employs a Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) [

8,

9], following a structured process adapted from established DSRM guidelines and exemplified in related works. The research followed the following distinct phases:

Problem Identification and Motivation (

Section 1.1), where we identify the significant challenges traditional BPC approaches face in modern MSA/Cloud settings and motivates the necessity for a new, specialized framework.

Definition of Objectives for a Solution: Stemming from the identified problem and the acknowledged literature gap concerning established BPC practices in MSA/Cloud, the precise objectives for the BPC4MSA framework were defined through a systematic requirements derivation process. This process, detailed in

Section 3, integrates First-Principles Analysis and Constructed Scenario Analysis [

10], resulting in a synthesized set of functional and non-functional requirements that constitute the explicit objectives for the artifact.

Design and Development (

Section 4), which details the architectural design and component development of the BPC4MSA framework artifact. This artifact was created specifically to instantiate a solution meeting the objectives (requirements) defined in

Section 3.

Evaluation (

Section 5 & 6), which presents a dual-method evaluation of the artifacts. First, in Sections 5, we conduct a Design Evaluation, where the conceptual framework artifact is assessed. Following Polyvyanyy et al. [

11], we use a Systematic Literature Review as the method to rigorously validate the framework’s conceptual novelty and its completeness in addressing the identified research gaps. Second, in

Section 6, we conduct a Prototype Evaluation, where the instantiated prototype artifact is assessed via a preliminary, non-functional empirical study.

Communication: This paper serves as the primary vehicle for communicating the entire research process, including the problem context, methodology, artifact design, and findings from both the design and empirical evaluations (DSRM Guideline 7: Communication of Research). Sections 7 (Discussion) and 8 (Conclusion) fulfill this, summarizing findings and outlining future work.

This structured DSRM approach ensures rigor in both the development of the BPC4MSA framework and the evaluation of its contribution to the field.

1.3. Contributions

This research makes the following primary contributions:

We present a systematically derived set of requirements specifically tailored for achieving Business Process Compliance within Microservices, addressing the unique challenges of decentralization and dynamism. Based on these objectives, we detail the conceptual design and description of the BPC4MSA framework artifact, a novel, cloud-native architecture for holistic Business Process Compliance management, spanning from design-time verification to runtime auditing. The conceptual novelty of this design, which theoretically proposes a mechanism to address critical research gaps like the “Broken Feedback Loop”, is rigorously established against the state-of-the-art through a systematic literature review (

Section 5).

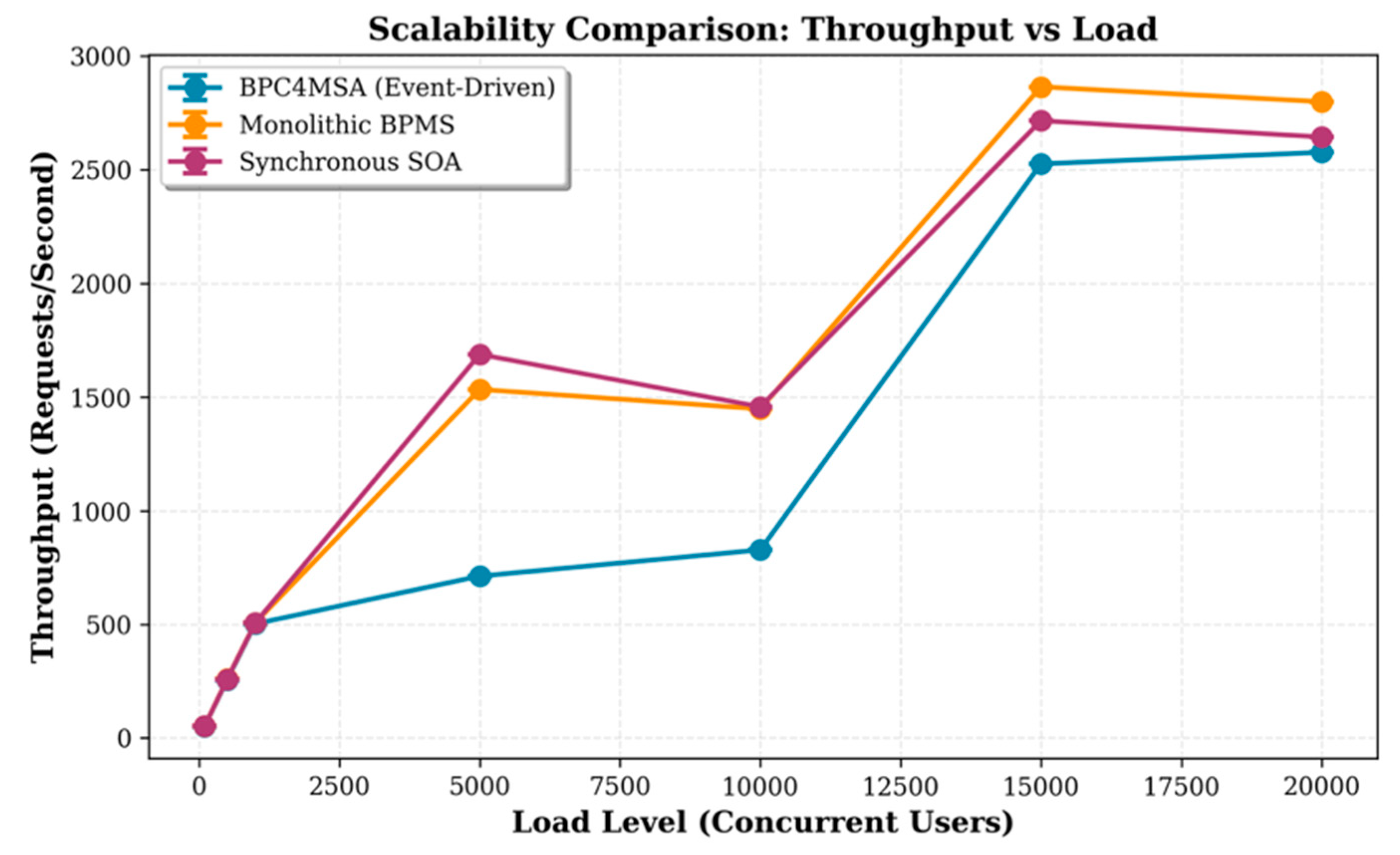

We provide a preliminary feasibility check of the BPC4MSA framework’s event-driven runtime component. This check is not a comparative performance benchmark, but a study of the pattern’s behavior under load. The results confirm the expected architectural trade-offs of an asynchronous, buffered pattern, demonstrating how it transforms a catastrophic “fast-fail” state into a manageable processing queue. This confirms the pattern’s suitability for asynchronous auditing while empirically reinforcing the importance of effective implementation (e.g., consumer scaling) to manage processing latency

1.4. Paper Structure

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides necessary background and establishes formal foundations.

Section 3 details the requirements derivation for BPC4MSA.

Section 4 describes the proposed framework design.

Section 5 evaluates the conceptual framework via a Systematic Literature Review.

Section 6 details the implementation and preliminary evaluation of a prototype artifact.

Section 7 discusses the combined findings, highlighting the architectural trade-offs between efficiency and resilience. Finally,

Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Background and Related Work

This section establishes the foundational concepts and theoretical context for the BPC4MSA framework. It begins by defining the core domains of Business Process Management (BPM), Business Process Compliance (BPC), Microservices Architecture (MSA), and Cloud Technologies. It then presents a structured review of the related academic literature, tracing its evolution to identify the specific research gap this paper addresses. Finally, it establishes the formal foundations used in the framework’s design.

2.1. Business Process Management

Business Process Management (BPM) is a discipline that uses the methods, techniques, and software used to define, model, manage, and analyze operational business processes throughout their lifecycle [

12,

13]. Its goal is to enhance efficiency, productivity, and cost-effectiveness in processes involving people, organizations, and digital systems [

1]. A business process consists of structured activities designed to deliver a product or service. Modern BPM must address dynamic and decentralized management needs, such as in Business Process as a Service (BPaaS), where cloud-based platforms enable modeling, customization, and distributed execution [

1].

BPM operates through a lifecycle comprising design, execution, and monitoring phases [

14]. Compliance is a fundamental aspect of BPM, ensuring adherence to laws, policies, and standards [

15]. Business Process Compliance (BPC) occurs across three stages: design-time verification, run-time monitoring, and post-execution auditing [

2,

14]. Advanced frameworks increasingly employ semantic repositories—integrating business, domain, and regulatory ontologies—to achieve unified and consistent compliance management [

14].

2.2. Business Process Compliance

Business Process Compliance (BPC) is the discipline of identifying, implementing, and verifying adherence to business-relevant requirements across the process lifecycle [

16]. It ensures that processes align with laws, standards, and internal policies [

17,

18]. Noncompliance can lead to financial penalties, litigation, and reputational loss [

19,

20], underscoring its importance in risk management [

21].

Prominent regulatory frameworks such as GDPR, HIPAA, SOX, and PCI DSS govern data protection, financial accountability, and information security [

7,

22].

BPC operates through design-time, run-time, and post-execution auditing [

23], using techniques like temporal logic, Petri nets, and compliance patterns [

24].

With the rise of cloud computing, traditional centralized methods face scalability limits [

18]. Emerging cloud-native BPC models—such as Security Validation as a Service (SVaaS) [

25] and Compliance Monitoring as a Service (BP-MaaS) [

20]—enable scalable, autonomous, and proactive compliance governance.

2.3. Microservices Architecture

Microservices Architecture (MSA) represents a major evolution from traditional monolithic systems, which bundle all functionalities within a single deployable unit. While monolithic designs were once effective for smaller systems, they become increasingly rigid and inefficient in distributed and rapidly changing environments [

5]. Large monoliths suffer from limited scalability, increased complexity, and tight coupling, making updates or partial redeployments difficult and risky [

26]. These systems often face technology lock-in, as all components must share the same technology stack, and they experience availability issues, since a failure in one part may disrupt the entire application [

27].

To address these limitations, MSA decomposes applications into small, autonomous services, each focused on a single business capability and independently deployable [

28]. It can be viewed as the second generation of Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA)—retaining the service-based concept while eliminating SOA’s central bottlenecks like the Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) [

29]. MSA instead employs lightweight communication through REST APIs or asynchronous message buses, enhancing modularity, cohesion, and system resilience [

30].

Compared to SOA, microservices rely on event-based choreographies rather than orchestrations, enabling decentralized coordination and reducing dependencies between services [

28]. This decoupling empowers autonomous development teams to update, deploy, and scale services independently, leading to improved uptime, continuous delivery, and faster innovation [

5,

27].

However, MSA introduces new challenges, such as complex service decomposition, testing and deployment overhead, and difficulty in coordinating cross-service features [

27]. Despite these drawbacks, its cloud-native orientation makes it ideal for digital transformation and scalable cloud deployment on platforms like AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud [

26].

For Business Process Compliance (BPC), MSA provides strong architectural alignment. Microservices are often deployed as containerized clusters in multicloud environments, supporting fine-grained monitoring and QoS- or regulation-aware compliance checks [

31,

32]. Moreover, MSA’s adaptive and evolvable structure allows organizations to respond dynamically to regulatory or environmental changes through controlled automatic, semi-automatic, or global adaptation mechanisms [

28].

In sum, while microservices introduce new coordination and testing challenges, they remain the preferred paradigm for achieving scalable, resilient, and compliant architectures in modern enterprise systems.

2.4. Cloud Technologies

The rapid growth of organizations and IT applications has dramatically increased both operational and infrastructure workloads, pushing many enterprises—particularly SMEs—to seek scalable, cost-effective alternatives to traditional on-premises systems [

26]. Cloud computing emerged as a transformative solution, offering elastic scalability, reduced capital expenditure, and operational flexibility through a distributed network of virtualized computing resources [

33].

The launch of Amazon Web Services (AWS) in 2006 marked the beginning of the public cloud era, followed by rapid market expansion and global adoption [

26,

34]. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this trend, making cloud infrastructure central to digital transformation and remote operations worldwide [

34].

Cloud computing is fundamentally a distributed, virtualized environment where computational resources—servers, storage, and networking—are shared, reused, and provisioned dynamically on demand [

33]. Its elastic and utility-like model allows organizations to scale up or down efficiently while paying only for consumed resources.

The emergence of cloud-native technologies has extended these principles further. As defined by the Cloud Native Computing Foundation [

35] cloud-native systems are built to exploit the full potential of cloud environments through microservices, containers, service meshes, immutable infrastructure, and declarative APIs. These technologies promote resilience, scalability, and continuous delivery, enabling organizations to respond rapidly to evolving business needs.

Within this paradigm, Microservices Architecture (MSA) naturally complements cloud computing by distributing computing and storage across multiple services and nodes. This model supports deployment across public, private, and hybrid clouds, offering flexibility to migrate or replicate components seamlessly between environments [

26].

In summary, cloud technologies—driven by virtualization, containerization, and microservices—have become foundational to modern enterprise transformation, enabling organizations to achieve agility, efficiency, and compliance in an increasingly dynamic digital landscape.

2.5. Related Work

With the foundational concepts defined, this section presents a systematic review of the related work. The literature on Business Process Compliance reveals a clear and logical progression that can be clustered into three main streams, moving from foundational concepts towards the challenges of modern, decentralized architectures.

2.5.1. Stream 1: Foundational Frameworks and Proactive Assurance

The initial wave of BPC research focused on establishing the need for systematic compliance management in distributed systems like Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) and early Cloud environments. The primary concern was moving beyond manual, ad-hoc checks to more automated, proactive approaches [

21,

36]. This era placed a heavy emphasis on “shift-left” strategies, utilizing formal methods such as model-checking [

25,

37] and Petri nets [

36] to verify compliance at design-time, before deployment.

A key development during this period was the introduction of holistic governance frameworks [

21,

38,

39] that proposed central repositories for policies and a unified view of compliance. This centralized governance model laid the groundwork for the architectural pattern of “Compliance-as-a-Service”, where compliance logic is decoupled into dedicated, reusable services [

20,

25,

37].

2.5.2. Stream 2: Runtime Monitoring, Adaptation, and Lifecycle Management

As cloud environments grew more dynamic and complex, the research focus shifted from static, pre-deployment checks to the challenges of continuous, runtime compliance [

19]. Researchers in this stream began adopting more powerful runtime technologies like Complex Event Processing (CEP) for real-time analysis [

20,

40] and the introduction of semantic, ontology-based models for richer, context-aware monitoring [

14].

Researchers also focused heavily on the management of the entire compliance lifecycle. Researchers began to address the evolution of rules [

41], the impact of process changes [

42], and the need for unifying abstractions like “Compliance Descriptors” to manage this complexity [

43,

44]. This led to the concept of “Adaptive Compliance”, aiming for systems that could dynamically respond to changes and violations, often using control loops like MAPE-K [

19], particularly in architectures for cloud service brokers [

32].

2.5.3. Stream 3: Decentralization, Operational Reality, and Next-Generation Challenges

The most recent research grapples with the challenges posed by highly dynamic, decentralized, and operational-heavy environments, particularly those defined by Microservices Architecture (MSA) and multi-cloud setups. MSA, which decomposes applications into small, independently deployable services [

5], offers agility but exacerbates the difficulties of centralized monitoring and control.

This stream shows several key trends. First, researchers are the exploration of decentralized trust mechanisms, such as blockchain and distributed ledgers, to create immutable and transparent audit trails [

13,

31]. Second, many are move to address compliance at the operational and infrastructure level, giving rise to the powerful concept of “compliance by default” for infrastructure configuration [

45] and the detection of operator errors [

16]. Finally, there is a growing recognition that compliance is not just a technical problem but an economic one, leading to data-driven, post-mortem analysis using Process Mining [

16] and the development of models for assessing the economic impact of compliance measures [

46].

These streams show a clear evolution toward decentralized and operational-heavy environments. In

Section 5.7, we will evaluate our proposed design against the specific approaches in this state-of-the-art to confirm its novelty and demonstrate how it addresses the field’s persistent challenges.

2.6. Formal Foundations for BPC in MSA/Cloud

To rigorously define the compliance problem in a distributed, process-centric environment, we establish the following formal foundations. These definitions are aligned with established BPM and workflow literature. The “MSA/Cloud” context is explicitly reflected in the distributed nature of these definitions, where data (events) originates from multiple, independent services rather than a single monolithic source. These definitions describe the general artifacts and functions instantiated by our proposed framework in

Section 4.

Let be the universe of case identifiers, be the universe of activity identifiers, be the universe of timestamps, be the universe of attribute names, and be the universe of data values.

Definition 2.6.1 (Event):

An event is a tuple , where:

is the case identifier, linking the event to a specific process instance.

is the activity identifier (e.g., ‘Approve Loan’).

is the timestamp.

is a partial function representing the data payload. In an MSA/Cloud context, this payload is critical for traceability and typically contains attributes like serviceID (identifying the microservice source) and correlationID (linking distributed events).

Let be the universe of all possible events.

Definition 2.6.2 (Trace):

A distributed trace is a finite, non-empty sequence of events where

, and:

(all events belong to the same case). A trace is considered “distributed” as its constituent events may originate from numerous independent services

(events are ordered by timestamp).

In an MSA/Cloud context, a trace represents a reconstruction of a single process instance (a case). While formally defined by a shared case identifier (), this set of events is practically assembled from numerous, independent services by a logging function () using correlation attributes (like correlationID from Def. 2.6.1) found in the event payload ().

Let be the universe of all traces.

Definition 2.6.3 (Event Log):

An event log is a set of distributed traces, .

Definition 2.6.4 (Process Model):

A process model is a tuple , where:

is a set of nodes (model elements).

is a set of control-flow edges.

is a partial labeling function mapping nodes to activity identifiers.

is the set of start nodes.

is the set of end nodes.

Definition 2.6.5 (Regulation and Policy Artifacts): Regulation Source (): An unstructured or semi-structured artifact (e.g., a legal document).

Compliance Rule (): A formal, machine-readable predicate over a distributed trace, .

Compliance Policy (): A finite set of compliance rules, .

Definition 2.6.6 (Policy Formalization Function): A policy formalization function is a function that maps an unstructured regulation source to a formal compliance policy.

Definition 2.6.7 (Compliance Check Function): A compliance check function (a form of conformance checking) is a function that takes a distributed trace and a policy and produces a verdict .

Definition 2.6.8 (Logging Function): A logging function is a function that subscribes to a stream of distributed business events () and assembles them into a structured event log .

Definition 2.6.9 (Reporting Function): A reporting function is an aggregation function that takes an event log and a policy to produce a compliance report .

Definition 2.6.10 (Compliance Event): A compliance event is a specific type of event (generated by ) where and its payload contains .

Definition 2.6.11 (Identity Function): An identity function is a function that maps an incoming request (containing credentials or tokens) to an authenticated principal (a user or service) or to a null principal if authentication fails.

These definitions (2.6.1-2.6.11) establish a precise, formal language for describing the data, artifacts, and functions within a distributed, process-centric compliance ecosystem. They provide the necessary foundation for the subsequent sections. With this formal model in place, we will now proceed to

Section 3 to define the specific objectives for our solution, and then to

Section 4 to introduce the BPC4MSA framework as a concrete architectural instantiation of these formal functions (

etc).

3. BPC4MSA Requirements Elicitation and Definition

This section details the methodology employed to derive the requirements for the BPC4MSA framework and presents the resulting requirements, which constitute the specific objectives for the solution being designed within our Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) approach.

3.1. Overall Research Methodology Context

As outlined in

Section 1.2, this research adheres to a DSRM process [

8,

9]. The work presented in this section fulfills the

Define Objectives of a Solution phase. Due to the significant challenges in achieving effective BPC within modern MSA/Cloud environments, particularly the lack of established reference architectures and patterns specific to this context [

7], we undertook a rigorous requirements elicitation process. This process was informed by a preliminary analysis of the existing literature, which highlighted core problems, stakeholder needs, prevalent challenges, and proposed functionalities relevant to BPC in distributed and cloud settings.

3.2. Requirements Elicitation Context and Approach

The need for a novel BPC framework stems from several factors characterizing contemporary IT landscapes. These include escalating regulatory pressures across various domains, the strategic shift towards MSA to enhance organizational agility [

43], the pervasive adoption of cloud computing platforms [

36], the increasing prevalence of business processes operating across distributed systems and organizational boundaries [

47], and the recognized need for automation to improve the efficiency, scalability, and reliability of compliance activities over manual approaches [

36]. Domain-specific constraints, notably within banking [

48] and healthcare (HIPAA), alongside overarching data privacy mandates such as General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) further compound the complexity.

Our preliminary literature analysis underscored key research thrusts relevant to this context, including efforts in automating compliance certification [

36], adapting compliance management for dynamic cloud environments [

19,

43], leveraging semantics for enhanced compliance reasoning [

14], ensuring compliance throughout the system lifecycle [

49,

50], and addressing cloud adoption challenges for SMEs [

51]. This body of work involves diverse stakeholders whose needs must be considered, prominently including Compliance Officers/Auditors [

48], Business Users/Process Owners [

14], and the Developers/Engineers responsible for building and maintaining the systems, alongside IT experts, end customers [

36], regulators, and potentially cloud service providers [

7].

Given this multifaceted context and the identified gap in comprehensive BPC solutions specifically architected for MSA/Cloud, a direct application of requirements elicitation techniques from more established domains (cf. [

11]) was deemed insufficient. Therefore, we adopted a combined requirements derivation approach integrating:

First-Principles Analysis: To systematically derive functional and non-functional needs from the inherent properties and interactions of MSA, Cloud, and BPC, explicitly informed by the challenges documented in the literature.

Constructed Scenario Analysis: To explore and validate requirements within practical operational contexts, designing scenarios based on the specific stakeholder use cases identified in the literature.

This dual methodology ensures the resulting requirements possess both theoretical soundness and practical relevance necessary to guide the design of an effective BPC framework.

3.3. Derivation via First-Principles Analysis

The first-principles analysis component aimed to understand the fundamental compliance implications arising from the core technical and architectural characteristics of MSA and Cloud environments, independent of specific implementations but deeply informed by the systemic challenges reported in the literature. Our analysis proceeded in three main steps:

3.3.1. Identify Core Characteristics

We first enumerated and defined the salient characteristics of MSA (e.g., decentralization, independent deployability, service granularity, polyglot persistence, ephemerality, network communication reliance) [

5,

27], Cloud Computing (e.g., elasticity, on-demand resources, managed services, API-driven infrastructure, shared responsibility) [

35] and the essential tenets of BPC (e.g., policy enforcement, auditability, non-repudiation, traceability, real-time monitoring) [

4].

3.3.2. Analyze Interactions and Conflicts

Next, we analyzed the pairwise and multi-way interactions among these characteristics to identify inherent conflicts, tensions, or potential synergies impacting compliance. Crucially, this analysis was guided by the challenges highlighted in our literature review (

Section 2.5), particularly the shift to runtime monitoring (Stream 2) and the complexities of decentralized, operational-heavy environments (Stream 3). This analysis focused on interactions relevant to:

The difficulty of managing distributed data consistently across independent microservice databases versus BPC’s need for strong data governance (e.g., privacy, lineage) [

48]

The complexity of monitoring and verifying compliance for complex, potentially asynchronous inter-service communication patterns [

47].

The friction between MSA’s typical lack of centralized control and the need to enforce consistent compliance standards across independently developed services [

52].

The increased overall system complexity inherent in MSA impacting the ability to achieve holistic compliance understanding and verification [

14].

Deficiencies in observability and monitoring capabilities when trying to capture sufficient data for compliance verification across distributed services [

47].

Problems in defining clear boundaries and responsibilities for compliance in processes spanning multiple services or teams, especially in collaborative settings [

53].

The difficulty of maintaining compliance amidst the constantly evolving landscape of frequent microservice updates [

19].

The challenge of formalizing high-level compliance requirements into specific, verifiable rules at the microservice level [

14].

The potential for significant performance overhead when implementing runtime compliance checks [

54].

By systematically exploring the interplay between MSA/Cloud characteristics (like decentralization, network reliance, ephemerality) and BPC needs (like auditability, traceability, policy enforcement) through the lens of these documented challenges, we identified the fundamental points of friction and opportunity.

3.3.3. Deduce Necessary Capabilities

Based on the specific conflicts and tensions identified in the previous step – which correspond to the literature challenges – we then deduced the fundamental system capabilities required for any BPC framework to effectively function within this context. These capabilities represent necessary architectural responses:

To address the conflicts arising from decentralization and the lack of centralized control impacting auditability, the capability for reliable, distributed event correlation and aggregation was deduced as essential [

38,

55].

To manage data governance across distributed data management complexities [

48], capabilities for policy definition applicable to data handling and mechanisms to trace data flow across services were identified as necessary.

To ensure traceability despite complex inter-service communication patterns and potential observability gaps [

47], the capability for robust context propagation and comprehensive event logging across service boundaries was deemed fundamental.

To counter the challenge of cloud ephemerality impacting audit trail continuity (related to the evolving landscape discussed by [

19], capabilities for decoupled, persistent, and potentially immutable logging services were identified as critical.

To mitigate performance overhead concerns, the analysis suggested that compliance checking mechanisms should ideally be lightweight, distributable, and potentially operate asynchronously where feasible [

56].

To address the difficulty in formalizing requirements and managing complexity, capabilities supporting expressive yet processable policy languages, potentially leveraging semantic representations, were seen as necessary [

14].

To manage the evolving landscape and issues with defining boundaries, capabilities related to dynamic policy updates and clear association of rules with services/processes were deduced [

19].

These deduced capabilities, arising directly from the interplay of core architectural principles and known compliance difficulties documented in the literature, formed the initial, theoretically grounded set of requirements for BPC4MSA.

In summary, the first-principles analysis allowed us to move beyond surface-level problems and identify a core set of essential capabilities mandated by the fundamental nature of MSA, Cloud, and BPC interactions, explicitly informed by and responding to the systemic challenges reported in the literature, thus providing a foundational layer for the requirements definition process.

3.4. Derivation via Constructed Scenario Analysis

To complement the theoretical deductions and ensure practical relevance, we designed and analyzed a set of realistic operational scenarios.

3.4.1. Scenario Design

We developed five distinct scenarios, each illustrating plausible yet challenging BPC situations grounded in common MSA/Cloud patterns and regulatory contexts (e.g., finance, healthcare data processing). These scenarios were designed to reflect specific stakeholder goals identified in the literature:

Scenario 1 - High-Volume Asynchronous Transaction Auditing (Compliance Officer Goal): This scenario detailed a process involving a customer initiating an online payment that triggered interactions across an Order Service, a Payment Gateway Service, a Fraud Detection Service, and an Account Service. The compliance requirement is not to block the transaction, but to ensure that a complete, verifiable audit trail is generated and checked for every transaction within a guaranteed time window (e.g., 5 minutes). The core challenge is ensuring this auditing system can handle peak transactional loads (e.g., Black Friday) without crashing, dropping events, or impacting the performance of the core transaction services. The audit must be guaranteed and eventual, even if processed seconds or minutes after the transaction completes. This reflects the need for resilient, high-throughput auditing rather than brittle, synchronous enforcement [

22,

47].

Scenario 2 - Auditing GDPR Right-to-Erasure Across Services (Auditor Goal): This scenario depicted an automated process triggered by a user’s request to be forgotten under GDPR. It required coordinating deletion or anonymization tasks across a Customer Profile Service, an Order History Service, and a Marketing Preferences Service, potentially involving asynchronous communication. The core challenge was ensuring complete removal across all services and generating an immutable, verifiable audit trail proving compliant execution for the auditor [

48,

53].

Scenario 3 - Pre-deployment Compliance Check in CI/CD (Developer Goal): This scenario focused on a developer committing code for a new version of a Shipping Service. The CI/CD pipeline needed to automatically check the service’s configuration and dependencies against organizational security policies (e.g., allowed base images, secret management) and data handling rules (e.g., ensuring no Personally Identifiable Information (PII) is logged) before deploying to a staging or production environment [

48,

55,

57,

58]

Scenario 4 - Dynamic Policy Update for Data Residency (Compliance Officer Goal): This scenario addressed the need to update a data residency policy (e.g., requiring data for European customers to remain within EU zones [

59] due to a regulatory change. The challenge involved propagating this updated policy to multiple services (e.g., User Profile Service, Data Analytics Service) dynamically and verifying that subsequent processing adhered to the new constraint without service interruptions [

19].

Scenario 5 - Business User Compliance Dashboard Interaction (Business User Goal): This scenario described a Business Process Owner for ‘Order Fulfillment’ reviewing a compliance dashboard. An alert indicated unusual delays violating an internal SLA policy within the process, traced to a specific interaction between the Inventory and Shipping services. The scenario detailed how the user navigated the dashboard to understand the violation context and initiated a pre-defined escalation workflow [

48,

60,

61,

62].

Each scenario explicitly defined the context, actors, triggers, sequence of operations (including potential parallel or asynchronous steps typical of MSA), data involved, specific compliance rules derived from regulations or internal policy, and explicitly identified potential points where compliance could fail.

3.4.2. Scenario Analysis

We systematically analyzed each constructed scenario using a combination of techniques:

Walkthroughs: We conducted detailed walkthroughs of each scenario, tracing the flow of control and data between microservices, identifying decision points, and mapping interactions against the specified compliance constraints.

Capability Gap Analysis: For each step, particularly potential failure points, we assessed the capabilities of typical MSA/Cloud infrastructure elements (e.g., API gateways, service meshes, standard logging libraries, orchestrators) and common operational practices. We identified where these standard capabilities would be insufficient to automatically detect or prevent the specific compliance violation described in the scenario. This highlighted gaps related to, for instance, lack of cross-service context propagation, inadequate granularity in logging, difficulty in enforcing complex temporal rules at runtime, or absence of integrated policy checking points.

Requirements Elicitation: The identified capability gaps directly informed the elicitation of concrete requirements for the BPC4MSA framework. For example, the gap in tracing data across asynchronous communication in Scenario 2 led to a requirement for robust event correlation mechanisms (FR3). The inability of standard CI/CD tools to perform deep policy checks in Scenario 3 led to requirements for design-time validation capabilities (FR2) and integration interfaces (FR10). The need for business-level visibility in Scenario 5 drove requirements for user-centric reporting and dashboards (FR7) and potentially low-code configuration (FR12). This process ensured that elicited requirements were directly tied to addressing specific, practical compliance challenges within the target environment.

3.5. Synthesized BPC4MSA Requirements

3.5.1. Overview

The analyses from the preceding sections, integrating first-principles reasoning with insights from constructed scenarios grounded in the literature, led to on a set of core functional capabilities and essential non-functional qualities required for the BPC4MSA framework. These synthesized requirements, refined from the deduced needs and practical challenges, became the design objectives for the artifact. They are formulated to address the unique complexities of achieving BPC within MSA/Cloud architectures, informed by the challenges and potential solutions identified in the literature. This section outlines these objectives, first describing the core functional capabilities the framework must possess, and second, the essential non-functional qualities it must exhibit. Within each description, the specific underlying requirements (FRs/NFRs) derived from the analysis are highlighted. Acknowledging the evolving technological landscape, forward-looking considerations regarding AI integration are also included.

3.5.2. Core Functional Capabilities

The BPC4MSA framework must provide the following fundamental capabilities:

C1 - Comprehensive Policy Lifecycle Management: Addressing the challenge of consistently defining, updating, and applying compliance rules across numerous, independently deployed, and potentially heterogeneous microservices, this capability encompasses the end-to-end management of policies within the MSA/Cloud contex. It requires mechanisms for Formal Policy Specification (FR1) using machine-readable formats, potentially enhanced by Semantic Representation Support (FR11) using ontologies or similar structures to handle complexity and ambiguity [

14,

48]. It must also include robust Compliance Change Management (FR8) features to handle policy evolution, impact assessment, and dynamic propagation of updates across distributed services [

19]. To facilitate reuse and standardization, support for a Compliance Pattern Library (FR13) is necessary [

58,

63].

C2 - Proactive Compliance Assurance: To prevent compliance violations from entering the dynamic microservices environment via frequent, independent service deployments, the framework must enable verification before execution. This capability is primarily realized through Design-Time Compliance Validation (FR2), allowing analysis of service designs, configurations, or code against policies, often integrated with development tools or CI/CD pipelines [

48,

57].

C3 - Runtime Compliance Monitoring and Auditing: Given that business processes in microservices execute across distributed services, often involving complex and asynchronous communication patterns, this capability addresses the need for continuous compliance oversight during execution. It necessitates Distributed Event Collection & Correlation (FR3) mechanisms to capture relevant activities across microservices and reconstruct process instances ([

47]). Building on this, Runtime Compliance Monitoring & Auditing (FR4) is required to evaluate behavior against rules in a decoupled, asynchronous manner and trigger verification actions (e.g., logging for post-hoc review). This capability focuses on detecting and recording violations for post-execution analysis, rather than synchronous, real-time prevention.

C4 - Robust Compliance Auditing and Analysis: To overcome the inherent fragmentation of execution logs and data across decentralized microservices and reconstruct reliable evidence for verification and learning, the framework must provide comprehensive post-execution capabilities. This includes Automated Conformance Checking (FR5) to compare actual execution traces against expected models or rules [

53], supported by Immutable Audit Trail Management (FR6) ensuring secure, reliable, and tamper-evident logging, potentially using technologies like blockchain [

53,

64]. To understand deviations, Root Cause Analysis Support (FR9) features are needed [

48]. Findings must be communicated effectively through Compliance Reporting and Visualization (FR7) via dashboards [

60,

61], which should ideally offer Low-Code/No-Code Configuration (FR12) options for usability [

62].

C5 - Seamless Ecosystem Integration: To function effectively within the complex and interconnected MSA/Cloud ecosystem (including diverse PAIS, observability tools, and CI/CD platforms), the framework cannot operate in isolation; therefore, it requires capabilities for Integration Interface (FR10) provision. This involves well-defined APIs and mechanisms to connect with external regulatory sources, PAIS, CI/CD platforms, observability tools, service meshes, and potentially identity management systems [

31,

65,

66,

67].

3.5.3. Essential Non-Functional Qualities

The practical success of BPC4MSA hinges on exhibiting key non-functional qualities:

NQ1 - Performance and Resource Efficiency: The framework must operate efficiently within the demanding MSA/Cloud context. This primarily requires high Scalability (NFR1) to handle dynamic loads and Performance Efficiency (NFR2) to ensure compliance checks impose minimal overhead on business processes. Managing latency, especially from potential AI integrations (NFR9), is also encompassed here [

27].

NQ2 - Trustworthiness and Security: As a system underpinning compliance, trustworthiness is paramount. This fundamentally demands robust Security (NFR4) measures protecting the framework and its sensitive data [

59] and ensuring High Availability & Resilience (NFR3) against failures [

27]. Aspects like the reliability of potential AI outputs (NFR10), data privacy (NFR11), and the explainability of compliance decisions (NFR8) are critical sub-dimensions contributing to overall trustworthiness.

NQ3 - Adaptability and Usability: The framework must be practical to deploy, use, and evolve over time. Key aspects include Extensibility (NFR6) to accommodate new regulations and technologies [

19] and Usability (NFR5) for diverse stakeholders, potentially enhanced by Low-code interfaces (FR12). Maintainability (NFR7) is also crucial for long-term viability in agile environments [

27].

3.5.4. Summary of Core Objectives

In essence, the primary objective defined by these requirements is to create a BPC framework (BPC4MSA) that delivers the core functional capabilities (C1-C5) while exhibiting the essential non-functional qualities related to performance/efficiency (NQ1), trustworthiness/security (NQ2), and adaptability/usability (NQ3) necessary for effective operation within complex, dynamic, and distributed MSA/Cloud environments. The framework must address the unique challenges posed by these modern architectures while delivering actionable compliance insights and controls, with considerations for future AI integration.

Section 4 will now detail the design of this framework, showing how it instantiates the formal functions (e.g.,

) defined in

Section 2.6 to meet these objectives.

4. The BPC4MSA Framework Design

This section presents the design of the BPC4MSA framework, the primary artifact developed in this research. The design directly addresses the core functional capabilities (C1-C5) and essential non-functional qualities (NQ1-NQ3) identified as objectives in

Section 3. Furthermore, this architecture serves as a concrete instantiation of the formal functions (

, etc.) and data artifacts (

,

,

) defined in

Section 2.6.

4.1. Overview and Design Principles

BPC4MSA is conceived as a cloud-native, microservices-based framework designed for agility, scalability, and comprehensive compliance management. Key design principles include:

Decentralization: Aligning with MSA principles, core compliance functionalities are decomposed into independent microservices.

Event-Driven Communication: An event bus facilitates asynchronous communication and loose coupling between services, enhancing resilience and scalability.

Separation of Concerns: Services are grouped logically based on their primary function (e.g., BPC Automation, System Management, Integration).

API-Centricity: An API Gateway manages external communication, providing a unified interface for various client applications.

Extensibility: The architecture is designed to accommodate future requirements, including potential integration with advanced AI capabilities.

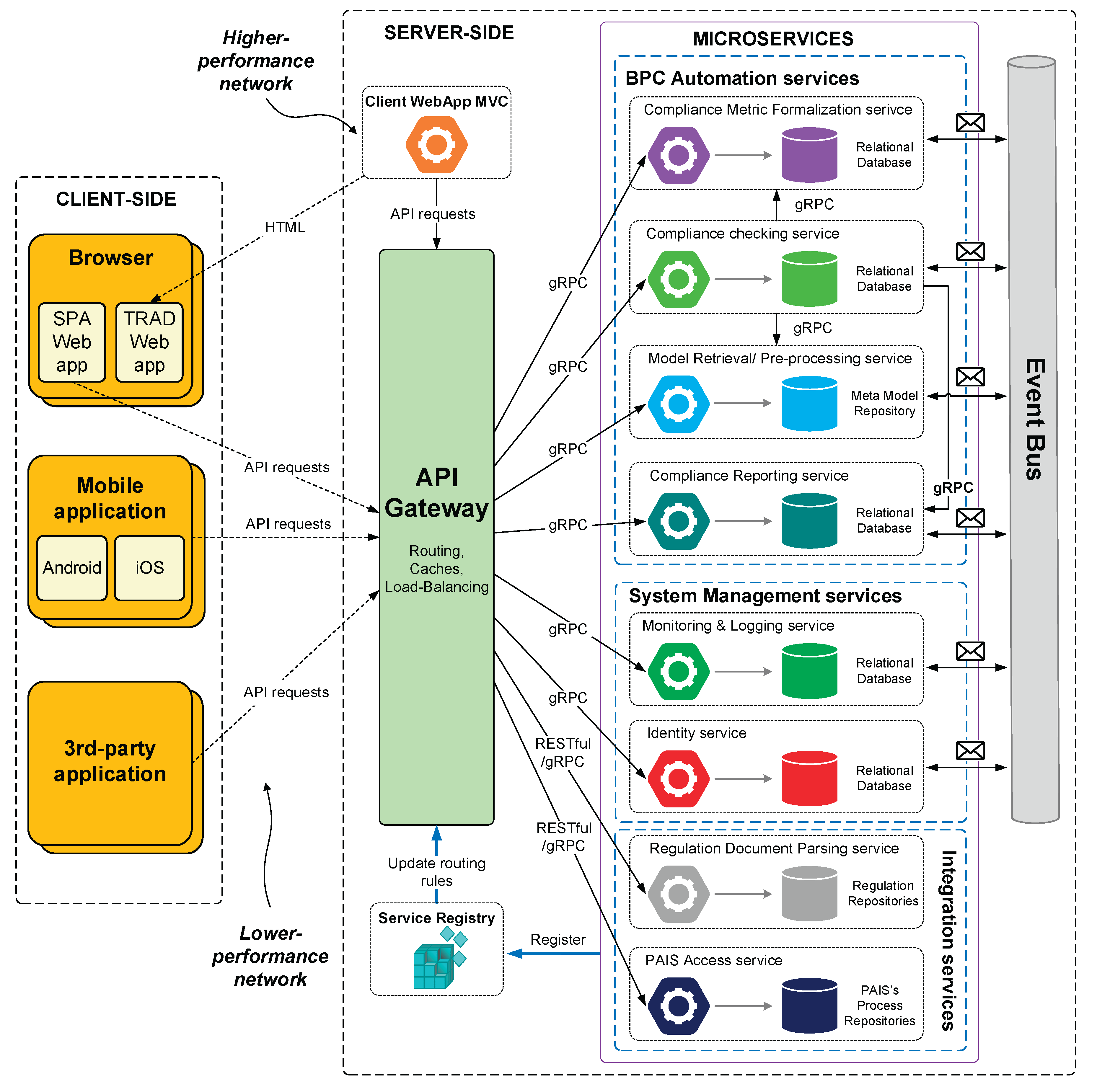

The overall architecture, illustrated in

Figure 1, depicts the relationships between client applications, infrastructure components, and the core microservice clusters.

4.2. Architecture and Components

The BPC4MSA framework comprises several interacting components, organized into logical clusters deployed server-side, interacting via an API Gateway and an Event Bus, and serving various client applications.

Formally, the BPC4MSA framework (

) is a concrete instantiation of the concepts defined in

Section 2.6. We define the framework as a tuple:

where:

is the set of BPC Automation services, which instantiate the core compliance functions ().

is the set of System Management services, which instantiate the operational functions ().

is the set of Integration services, which provide access to external artifacts (, ).

is the Event Bus, the mechanism for handling the event stream ().

is the API Gateway, the unified interface to the framework’s functions.

The components of this framework are detailed below and illustrated in

Figure 1.

4.2.1. Client-Side Applications

These represent the consumers of the framework’s functionalities and interact with the server-side via the API Gateway using standard protocols like RESTful APIs. Examples include:

Web Applications (SPA/TRAD): Providing interfaces for compliance officers, auditors, business users, and potentially developers to define policies, monitor status, view reports, and manage violations.

Mobile Applications: Offering potentially optimized views and interactions for on-the-go monitoring or approvals.

Third-Party Applications: Allowing external systems (e.g., Governance, Risk, and Compliance (GRC) platforms, external auditing tools) to integrate with BPC4MSA via public APIs.

4.2.2. Infrastructure Components:

These provide essential cross-cutting concerns for managing and operating the microservices:

API Gateway: Acts as the single entry point for all client requests. It handles routing, load balancing, caching, and potentially initial authentication/authorization, abstracting the underlying microservice structure from clients.

Service Registry: Enables dynamic service discovery, allowing services and the API gateway to locate instances of other services in the potentially dynamic cloud environment. Services register themselves upon startup.

Event Bus: Facilitates asynchronous, publish-subscribe communication between microservices. This decouples services, allowing them to react to events (e.g., policy updates, detected violations, process milestones) without direct dependencies, enhancing resilience and scalability.

4.2.3. Microservice Clusters

The core logic resides in distinct microservices grouped by function:

BPC Automation Services (): These services implement the primary compliance logic:

Compliance Metric Formalization Service: (Instantiates ) Responsible for translating compliance requirements (potentially received from the Regulation Document Parsing service or user input via client apps) into the formal representation used by the checking engine (e.g., BhR, PCL). This service could potentially interface with AI models in the future to assist in translating natural language policies (related to C1).

Model Retrieval/Pre-processing Service: (Retrieves ) Fetches business process models and related metadata from external sources (via the PAIS Access service) and prepares them for compliance analysis (related to C1, C5).

Compliance Checking Service: (Instantiates ) The core engine that performs compliance verification. It takes formalized rules/metrics and process models/traces as input and evaluates compliance, potentially supporting both design-time checks (C2) and runtime/post-execution analysis (C3, C4) based on events from the Event Bus or data from the Monitoring & Logging service.

Compliance Reporting Service: (Instantiates ) Aggregates compliance results, generates reports, and provides data for dashboards presented via client applications. It could potentially leverage AI in the future for generating natural language summaries or explanations of compliance status or violations (related to C4).

System Management Services (): These provide operational support:

Monitoring & Logging Service: (Instantiates ) Collects operational logs and metrics from all microservices for health monitoring and performance analysis. Crucially, it also aggregates and stores the compliance audit trail data (events, check results) generated by other services, potentially via the Event Bus, ensuring data is available for auditing (related to C3, C4).

Identity Service: (Instantiates ) Manages authentication and authorization for users and potentially services interacting with the framework, ensuring secure access control (related to NQ2).

Integration Services (): These handle communication with external systems:

Regulation Document Parsing Service: (Retrieves ) Interfaces with external repositories or tools to retrieve and potentially parse regulatory documents or external policy sources, feeding information to the Formalization service (related to C1, C5).

PAIS Access Service: (Retrieves or from external systems) Provides a dedicated interface for interacting with various Process-Aware Information Systems (PAIS) to retrieve process models and execution data (related to C5).

Each microservice typically manages its own dedicated database (e.g., Relational, NoSQL, Meta Model Repository, Regulation Repositories) to maintain loose coupling and allow for technology choices optimized for the service’s specific needs. Communication between microservices often utilizes efficient protocols like gRPC for synchronous requests where needed, while leveraging the Event Bus for asynchronous notifications and data propagation.

4.3. Addressing Requirements

We now demonstrate how the BPC4MSA architecture and its components fulfill the core functional capabilities (C1-C5) and address the essential non-functional qualities (NQ1-NQ3) defined as objectives in

Section 3.5. This analysis provides the explicit link between the requirements (

Section 3), the formal foundations (

Section 2.6), and the artifact design (

Section 4).

4.3.1. Mapping Functional Capabilities

C1 (Policy Lifecycle Management): This capability is primarily realized through the interplay of the Compliance Metric Formalization Service and the Regulation Document Parsing Service. These services jointly instantiate the Policy Formalization Function (), which transforms an unstructured Regulation Source () into a formal Compliance Policy () (FR1, FR11). This service would also manage a Compliance Pattern Library (FR13) to support reusable rule definitions. Policy evolution (FR8) is managed through updates to these services, with changes propagated via the Event Bus to the Compliance Checking Service.

C2 (Proactive Compliance Assurance): This is enabled by configuring the Compliance Checking Service to operate in a design-time mode. In this mode, it instantiates the Compliance Check Function (), but applies it to a Process Model () (retrieved by the Model Retrieval Service) rather than a runtime trace (FR2).

C3 (Runtime Monitoring and Auditing): This is the core runtime capability. The Monitoring & Logging Service instantiates the Logging Function , subscribing to the Event Bus to consume the stream of distributed Events () and assemble them into a persistent Event Log (). The Compliance Checking Service then instantiates the Compliance Check Function (), applying a Policy () to a Distributed Trace () from the log (FR3, FR4). Violations trigger a Compliance Event () to be published back to the Event Bus for logging and reporting services.

C4 (Auditing & Analysis): This capability is built upon the outputs of C3. The Event Log (

) managed by the Monitoring & Logging Service serves as the immutable audit trail (FR6). The Compliance Reporting Service instantiates the Reporting Function (

), which aggregates data from the log to generate reports and dashboards (FR5, FR7, FR9, FR12). This architecture, by connecting the Compliance Reporting Service (C4) and the Compliance Metric Formalization Service (C1) via the Event Bus, theoretically proposes the mechanism to close the “Broken Feedback Loop” (GAP-2) mentioned in

Section 1.1 and

Section 5.7. It enables runtime insights from

to programmatically inform and update the policies managed by

. The empirical validation of this specific feedback loop mechanism is outside the scope of our preliminary prototype and is a key area for future work.

C5 (Ecosystem Integration): This is directly addressed by the dedicated Integration Services (PAIS Access, Regulation Document Parsing) and the API Gateway, which provide the necessary interfaces (FR10) to connect with external systems and data sources

4.3.2. Addressing Non-Functional Qualities

NQ1 (Performance and Resource Efficiency): The microservices architecture inherently supports Scalability (NFR1) by allowing independent scaling of high-load services (e.g., Compliance Checking Service, Monitoring & Logging Service). Performance Efficiency (NFR2) is addressed through asynchronous, non-blocking communication via the Event Bus, a design choice whose trade-offs are empirically evaluated in

Section 6. The management of potential AI-related latency (NFR9) would be localized to the specific services that integrate them, such as the Compliance Metric Formalization Service.

NQ2 (Trustworthiness and Security): Security (NFR4) is addressed through the dedicated Identity Service, secure communication protocols (e.g., TLS), network policies in the deployment environment, and secure data storage practices. High Availability & Resilience (NFR3) are achieved through the redundancy inherent in MSA deployments on platforms like Kubernetes and the decoupling provided by the Event Bus . Trustworthiness is further enhanced by immutable logging approaches (FR6) and the requirement for explainable outputs (NFR8), while AI integrations would necessitate specific validation (NFR10) and privacy measures (NFR11).

NQ3 (Adaptability and Usability): The modular microservice design promotes Extensibility (NFR6) and Maintainability (NFR7). For example, a new compliance rule can be added by updating the Compliance Metric Formalization Service without redeploying the entire system. Usability (NFR5) is addressed through the API Gateway, which provides a stable interface for user-facing client applications, including those offering low-code configuration (FR12)

4.4. Technology Stack

The microservices architecture allows for technology heterogeneity. However, a potential, coherent technology stack aligned with the requirements could include:

Orchestration: Kubernetes (for deployment, scaling (NFR1), resilience (NFR3)).

Event Bus: Apache Kafka or RabbitMQ (for scalable (NFR1), resilient (NFR3) asynchronous communication).

API Gateway: Kong, Traefik, or cloud provider gateways (for managing external access, routing).

Service Registry: Consul, etcd, or Kubernetes-native discovery (for dynamic discovery).

Databases: PostgreSQL (for relational data, e.g., Identity, Reporting), Cassandra/MongoDB (for high-volume logs/events, supporting NQ1), Graph Database (potentially for policy/model relationships supporting C1/FR11).

Monitoring/Logging: Elasticsearch/Fluentd/Kibana (EFK) stack or Prometheus/Grafana (for observability, supporting C4, NQ3).

Service Implementation: Go, Java (Spring Boot), Python (FastAPI) - chosen based on team expertise and specific service needs (contributing to NQ3/NFR7).

Communication: gRPC (for efficient internal synchronous calls), RESTful APIs (for external interaction).

The choice of specific technologies should be driven by detailed performance (NQ1/NFR2), security (NQ2/NFR4), maintainability (NQ3/NFR7), and extensibility (NQ3/NFR6) requirements.

4.5. Deployment Considerations

BPC4MSA is designed for cloud deployment, leveraging cloud-native principles:

Deployment Models: Can be deployed on managed Kubernetes services (e.g., EKS, GKE, AKS), self-managed Kubernetes clusters, or potentially adapted for serverless platforms where applicable. Hybrid deployments (part cloud, part on-premise) are feasible but increase complexity.

Scalability & Resilience: Achieved via Kubernetes auto-scaling based on resource utilization (CPU, memory) or custom metrics (e.g., queue length for the Event Bus), fulfilling NQ1/NFR1. Redundancy across multiple availability zones addresses NQ2/NFR3.

Security: Relies on cloud provider security features (network policies, IAM), secure configurations (e.g., secrets management), authentication/authorization via the Identity Service, and secure communication protocols (TLS), addressing NQ2/NFR4. Data encryption at rest and in transit is essential.

Data Management: Strategies for managing distributed data persistence, backups, and potential cross-region replication need careful consideration based on specific compliance requirements (e.g., GDPR data residency).

The deployment strategy must ensure that the non-functional qualities (NQ1-NQ3) identified in

Section 3.5 are met within the chosen cloud environment.

5. Design Evaluation: Systematic Literature Review

This section presents the evaluation of the BPC4MSA framework design artifact (detailed in

Section 4). Following established Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) guidelines for artifact evaluation [

8,

9] and drawing methodological inspiration from [

11], we employ a Systematic Literature Review (SLR). This method is specifically chosen as our design evaluation to validate the framework’s conceptual novelty against the state-of-the-art, and is distinct from the prototype’s preliminary evaluation presented in

Section 6. The primary goal of this evaluation SLR is to rigorously analyze the relevant state-of-the-art in Business Process Compliance (BPC) for Microservices Architecture (MSA) and Cloud environments, positioning the BPC4MSA design against existing approaches, identifying its potential contributions, and assessing the extent to which its design addresses the requirements (Capabilities C1-C5, Qualities NQ1-NQ3) defined in

Section 3.5 relative to prior work.

5.1. Methodology

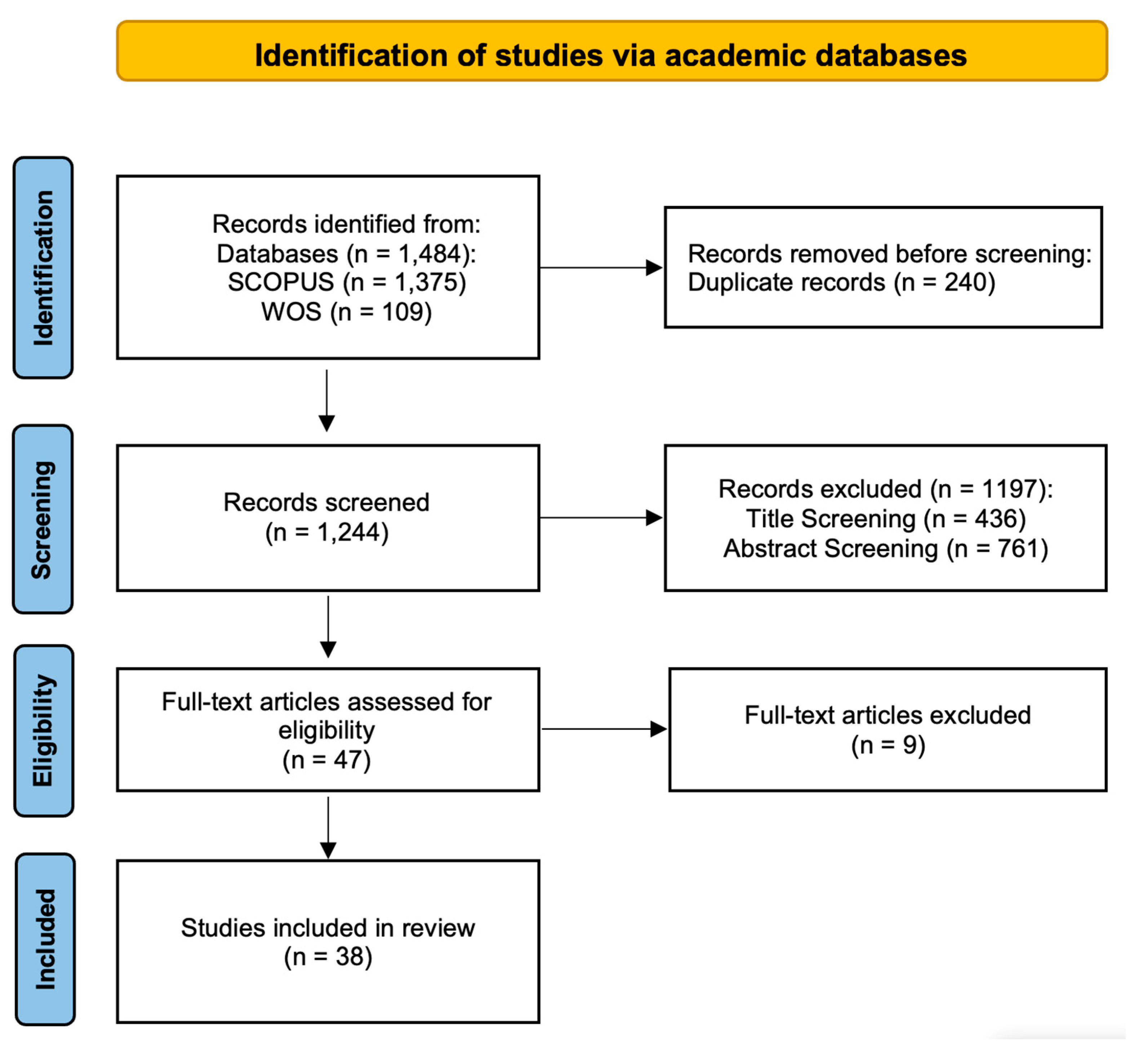

The SLR was conducted following established guidelines to ensure rigor and transparency. The process involved defining research questions, executing a systematic search, applying a multi-stage screening protocol based on predefined criteria, extracting relevant data, and synthesizing the findings. The overall flow of study selection is depicted in the PRISMA diagram (see

Figure 2)

5.2. Research Questions (RQs) for SLR

The SLR aimed to answer the following specific evaluation-focused research questions:

RQ-SE1: What existing frameworks, architectures, methods, or tools specifically address BPC (including aspects like policy management, monitoring, auditing, enforcement) within MSA, Cloud-native, or closely related Cloud/SOA contexts?

RQ-SE2: How do these existing approaches address the core functional capabilities (C1-C5) and non-functional qualities (NQ1-NQ3) identified as requirements for BPC4MSA in

Section 3.5?

RQ-SE3: What are the primary limitations or gaps in the current state-of-the-art concerning BPC for MSA/Cloud environments, based on the reviewed literature?

RQ-SE4: How does the proposed design of BPC4MSA compare to existing approaches, and what are its potential novel contributions towards addressing the identified gaps (RQ-SE3) and requirements (RQ-SE2)?

5.3. Search Strategy

A systematic search was performed across major academic databases relevant to computer science and information systems, including Scopus and Web of Science (WOS). Searches were primarily conducted within titles, abstracts, and keywords, limited to publications in English. The search strategy involved constructing search strings based on keywords related to the core concepts: BPC, Frameworks/Architectures, and MSA/Cloud/SOA environments. To ensure comprehensive coverage, several variations were employed, combining core terms with optional refinements. Key search term variations included:

Search Term 1 - Platforms Focus: (“business process compliance” OR “process compliance” OR “workflow compliance”) AND (“framework” OR “architecture” OR “system” OR “model” OR “approach” OR “method” OR “tool” OR “platform” OR “solution”) AND (“microservice architecture” OR “microservices” OR “cloud-native” OR “cloud computing” OR “cloud environments” OR “cloud services” OR “SOA” OR “service-oriented architecture”)

Search Term 2 - Requirements Focus: (“business process compliance” OR “process compliance” OR “workflow compliance”) AND (“framework” OR “architecture” OR “system” OR “model” OR “approach” OR “method” OR “tool” OR “platform” OR “solution”) AND (“requirements” OR “functional requirements” OR “non-functional requirements” OR “compliance requirements”)

5.4. Study Selection and Screening Process

A multi-stage screening process, guided by the PRISMA methodology (see

Figure 2), was employed to systematically identify relevant studies. After removing 240 duplicates from the initial 1,484 records, the titles and abstracts of 1,244 unique articles were screened. This screening excluded 1,197 records (436 by title and 761 by abstract), resulting in 47 articles for full-text analysis. After this analysis, 9 full-text articles were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria. This resulted in the final inclusion of 38 articles deemed most relevant for the evaluation synthesis.

5.5. Data Extraction

A predefined data extraction form was used to systematically collect information from each of the 38 included studies. To ensure consistency and rigor, the form was designed to capture key data points necessary to answer the evaluation research questions. These data points included: publication details (authors, year, title, venue), the stated problem or motivation, details of the proposed solution (e.g., framework name, architectural approach, key components), specific BPC aspects addressed (e.g., policy, monitoring, audit, enforcement), the explicit or implicit handling of requirements corresponding to BPC4MSA’s capabilities (C1-C5) and qualities (NQ1-NQ3), the underlying technologies or formalisms used, the evaluation methods employed within the study, and any limitations or future work identified by the authors.

5.6. Synthesis Method

The extracted data was synthesized using a combination of thematic and comparative analysis. Thematic analysis was employed to identify, analyze, and report patterns (themes) within the data, which enabled a qualitative understanding of the state-of-the-art and the identification of research trends and persistent challenges (addressing RQ-SE1 and RQ-SE3). Subsequently, a comparative analysis was conducted to systematically map the features, contributions, and limitations of the approaches described in the selected literature against the design principles, architecture, and intended capabilities of the BPC4MSA framework. This direct comparison was instrumental in positioning BPC4MSA, assessing its novelty, and formulating the comparative matrix (see

Table 1), thereby answering RQ-SE2 and RQ-SE4.

5.7. Literature Analysis & Framework Positioning

With the state-of-the-art established, we now evaluate the BPC4MSA framework’s design (from

Section 4) against the 38 selected papers. This comparative analysis begins by synthesizing the findings from the literature to answer RQ-SE1 (What existing approaches exist?) and RQ-SE2 (How do they address the defined requirements?). This synthesis reveals significant patterns in the focus of the BPC research community and provides the baseline against which we evaluate our artifact’s novelty.

The following quantitative analysis (addressing RQ-SE1 and RQ-SE2) is based on the 38 papers of the comparative matrix (see

Table 1):

Core Capabilities are Widely Addressed: A vast majority of the analyzed literature addresses the core tenets of compliance management. Policy Lifecycle Management (C1) is considered in 89% of papers (34 out of 38), and Adaptability (NQ3) is a key concern in 89% (34 out of 38), indicating these are foundational research topics.

Proactive and Reactive Measures are Prevalent: Both “shift-left” and “shift-right” approaches are very common. Proactive Compliance Assurance (C2) is addressed by 84% of papers (32 out of 38), and an equal percentage, 84% (32 out of 38), address Compliance Auditing & Analysis (C4).

Runtime Monitoring is a key, but not universal, Focus: While still a majority concern, Runtime Monitoring & Enforcement (C3) is the least frequently addressed of the core capabilities, appearing in 63% of papers (24 out of 38). A qualitative look confirms the finding from GAP-3: most of these works focus on monitoring and detection, with true automated enforcement remaining rare.

Qualitatively, several patterns emerged:

The Proactive vs. Reactive Divide: There is a clear pattern of mutual exclusivity between papers strong in Proactive Assurance (C2) and those strong in Compliance Auditing & Analysis (C4). Papers proposing formal, design-time verification methods [

16,

36,

37] rarely include sophisticated post-mortem analysis, and vice-versa for papers focused on BI or process mining [

16,

68]. This further supports the “Broken Feedback Loop” (GAP-2).

The Rise of Holistic Frameworks: A noticeable trend in later years (post-2015) is the emergence of more comprehensive frameworks that attempt to address three or more of the core capabilities simultaneously [

32,

39,

43,

44,

55,

69,

70]. This indicates a growing maturity in the field and a recognition that a holistic approach is necessary.

Architectural Drivers: The architectural approach is a strong predictor of focus. Papers based on formal methods (Petri nets, model checking) are almost exclusively focused on C2. Papers based on CEP and event-driven architectures are focused on C3. Papers based on data warehousing and BI are focused on C4. This specialization contributes to the siloing of research and the identified gaps.

This analysis of the state-of-the-art (answering RQ-SE1 and RQ-SE2) allows us to evaluate the BPC4MSA framework’s novelty (addressing RQ-SE4) and identify the specific gaps it addresses (RQ-SE3). We find that while many solutions address individual requirements, the literature lacks holistic frameworks that target the specific interplay of challenges in MSA/Cloud environments. Our evaluation confirms that the BPC4MSA design is novelly architected to address what we identify as five persistent research gaps, which the reviewed literature fails to resolve in an integrated manner:

GAP-1: The “Last Mile” Problem: The process of translating ambiguous legal text into precise, machine-readable rules remains a largely manual, error-prone bottleneck, limiting the agility of the entire compliance lifecycle.

GAP-2: The Broken Feedback Loop: There is a clear disconnect between proactive design-time tools, reactive runtime monitoring systems, and post-mortem analysis platforms, with no automated mechanism to feed insights back into design-time models.

GAP-3: Weak or Absent Automated Enforcement: The vast majority of research focuses on monitoring and detection. True automated enforcement—actively preventing or correcting violations at runtime without human intervention—is rarely addressed.

GAP-4: Integrating Internal (Architectural) and External (Regulatory) Compliance: The literature largely treats architectural integrity and regulatory compliance as separate problems, lacking a holistic framework that manages both simultaneously.

GAP-5: Scalability and Practicality of Advanced Solutions: Many proposed solutions based on formal methods, semantic ontologies, or blockchain face significant practical hurdles, including high modeling overhead and performance bottlenecks.

The BPC4MSA framework is explicitly designed to address these consolidated gaps (addressing RQ-SE4). Its core design centers on a unified Policy Lifecycle Management (C1) to address GAP-1 and GAP-2. The Runtime Monitoring & Auditing (C3) capability is designed for active asynchronous verification (GAP-3). The Proactive Compliance Assurance (C2) validates both internal and external rules (GAP-4). Finally, by using a scalable architecture, its design confronts the challenges in GAP-5.

Table 1 provides a detailed comparative analysis of the reviewed literature against the BPC4MSA framework’s capabilities.

Table 1.

Comparative Matrix of BPC Literature.

Table 1.

Comparative Matrix of BPC Literature.

| ID |

Citation |

Architectural Approach |

C1 |

C2 |

C3 |

C4 |

C5 |

NQ1 |

NQ2 |

NQ3 |

| 1 |

[71] |

Remote auditing, trusted computing, secure logging |

- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| 2 |

[36] |

Petri nets, formal patterns |

+/- |

+ |

- |

+/- |

- |

+/- |

+ |

- |

| 3 |

[31] |

Blockchain, smart contracts |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

| 4 |

[20] |

Service-based, Complex Event Processing (CEP) |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

| 5 |

[22] |

Self-monitoring, process rewriting |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 6 |

[38] |

SOA, CEP, DSLs |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| 7 |

[37] |

Cloud-based service, model-checking |

+/- |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| 8 |

[32] |

Cloud service broker, legal/QoS framework |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

| 9 |

[69] |

Cloud service broker, autonomic computing (MAPE-K) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

| 10 |

[25] |

Cloud-based service, model-checking |

+/- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

| 11 |

[14] |

Semantically-enabled, ontologies, COaaS |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

| 12 |

[44] |

Model-Driven Architecture (MDA), Compliance Descriptors |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 13 |

[45] |

Configuration management (Chef), experience report |

+/- |

- |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

| 14 |

[19] |

Adaptive process (MAPE-K loop) |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 15 |

[72] |

Goal-oriented Requirement Language (GRL), MCDA |

+/- |

+/- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+/- |

- |

| 16 |

[41] |

ISC evolution, RETE algorithm |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

- |

- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

| 17 |

[23] |

Variability Descriptors, Compliance Descriptors |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 18 |

[43] |

Model-Driven Architecture (MDA), Compliance Descriptors |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 19 |

[16] |

Process Mining, XES, economic assessment |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

| 20 |

[73] |

Timed Automata, TCTL, UPPAAL model checker |

+/- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| 21 |

[51] |

Model-based, SPIN model checker, LTL |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

- |

- |

+/- |

+/- |

| 22 |

[74] |

DSL, Model-Driven Development (MDD), CEP |

+/- |

- |

+ |

- |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

| 23 |

[18] |

User-centered, SPIN model checker, extended patterns |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 24 |

[21] |

SOA, knowledge-based, BPCL |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

| 25 |

[55] |

SOA, Deming cycle, KCIs, data warehouse |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

| 26 |

[75] |

Integrated compliance graph, decision support |

+/- |

+ |

- |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 27 |

[42] |

Integrated graph, interaction analysis |

+/- |

+ |

- |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 28 |

[76] |

Integrated graph, process adaptation tool (BCIT) |

+/- |

+ |

- |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 29 |

[70] |

State-aware, ROP ontology, Drools |

+/- |

- |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 30 |

[77] |

MTL, rule elicitation, graphical representation |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

| 31 |

[78] |

Semantic (OWL/SWRL), ontologies, Drools |

+ |

+/- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 32 |

[39] |

End-to-end framework, VbMF, DSLs, CEP |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

- |

+ |

| 33 |

[66] |

DevSecOps, security checklist methodology |

+ |

+ |

- |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

| 34 |

[40] |

TOSCA, XML nets, CEP, anti-patterns |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

| 35 |

[79] |

TOSCA, XML nets, CEP, anti-patterns |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/- |

| 36 |

[46] |

Economic assessment, Workflow Patterns, Cost-Benefit Analysis |

- |

+/- |

- |

+/- |

- |

+/- |

+/- |

+/- |

| 37 |

[68] |

Business Intelligence, Data Warehouse, OLAP |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+/- |

| 38 |

[50] |

Adaptive SOA, AOP, CEP |

+/- |

- |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |