Background

Stroke is still the most prevalent neurological disease and is one of appropriate causes of cerebral damage over the world. Although previously predominantly a disease of the elderly, there is an alarming trend towards increased prevalence of stroke in young adults here defined as 18-40 years. Stroke is an important public health problem in Bangladesh which is responsible for 14.7% of all deaths. The causes of stroke in the young are especially heterogeneous, stretching beyond the traditional risk factors to encompass uncommon conditions like inherited thrombophilias (i.e., Protein S deficiency), collagen vascular diseases, and also particular vasculitides for instance Takayasu’s arteritis. But systemic obstacles in resource-poor settings severely limit the ability to diagnose these rare causes. Major barriers include time to diagnosis, restricted availability of sophisticated brain imaging and a paucity of specialists trained in the treatment and management disorder, all factors that contribute directly to reduced opportunities for early intervention with suboptimal outcomes. This diagnostic delay emphasizes the requirement for better clinical vigilance and a more organized approach to gathering data. Aetiology-specific profiles are important in the context of preventive and acute management strategies required to effectively address this major maternal health crisis. Improving diagnostic capability and national guideline for young stroke are, thus, important measures in preventing the increasing trend of this destructive disease in Bangladesh and other similar settings.

Discussion

Spinal nerves extend from the spinal cord, which, together with the brain, composes the central nervous system and the essential blood supply, neurons and neural networks [

1]. Interference with this outflow (either spontaneously or following trauma) results in cerebrovascular disturbances, which include stroke, transient ischaemic attack, intraventricular haemorrhage, etc. The most common neurological disease and principal source of cerebral injury is stroke. It is characterised by the sudden onset of a non-convulsive neurological deficit secondary to cerebral circulation disturbance [

2]. Various ages of one patient are affected, from young kids to seniors. Some trends show that the number of 18- to 50-year-olds admitted into hospitals for stroke is growing. This value will help you determine the total number of instances in your group. [

3].

According to the most recent WHO statistics, which appeared in 2021, the percentage of overall mortality in Bangladesh due to stroke is 14.7 per cent, with an age-adjusted death rate of 160.40 per 100,000 people. [

4]. Furthermore, although the most frequent origins are prevalent, isolated central nervous system angiogenesis, heritable connective tissue disorders, and other genetically specified disorders cause only a minor proportion of ischaemic strokes in youngsters [

5,

6].

According to the risk appraisal of the Framingham Heart Study, more than 75.0% of stroke sufferers had a heart attack, and 36.0% of patients were aged between 41 and 45 years old [

7]. 6. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study found that every year, there were 23 strokes per 100,000 persons aged 20 to 44 years. An additional 45% had an ischaemic stroke, 30% had an intracerebral haemorrhage, and 26% had a subarachnoid haemorrhage [

8,

9]. Patients with a patent foramen ovale’s polymorphisms, including prothrombin, factor V Leiden, and others who cause hereditary and acquired thrombophilias, are more common options. Particularly, young stroke sufferers frequently exhibit these polymorphisms due to their predominantly European ethnic background [

10,

11,

12]. An autosomal dominant deficiency of antithrombin III induces clot formation in veins. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and its immediate family of associated conditions, which belong under antiphospholipid syndrome, quadruple the risk of stroke for younger patients [

13].

Limited resources and systemic barriers worsen outcomes for rare stroke and stroke mimics in low-resource Bangladesh. These obstacles consist of diagnostic delay, absence of infrastructure, limited access and cost to thrombolysis and thrombectomy, lack of access to neuroimaging, and a hard-wearing scarcity of trained personnel that hinders timely actions [

14].

Two cases of hereditary protein S deficiency were identified among the patients seen at Dhaka Medical College (DMC). This condition was previously concealed because of the suppressive effects of oral contraceptives or pregnancy, but when EDPS became more severe, patients experienced Ischaemic Stroke (IS) for it. Both of the patients had hemiplegia and aphasia, which are typical presentations of stroke [

15]. A type of large-vessel granulomatous vasculitis, Takayasu’s arteritis is distinguished by marked intimal fibrosis and vessel narrowing. Commonly involved organs are the aorta, branches, and pulmonary arteries [

16]. In a case report in 2017, a 20-year-old cadet was being treated with antiviral therapy for chickenpox at Combined Military Hospital Chittagong and developed right hemiplegia and decreased level of consciousness secondary to a juvenile stroke due to Takayasu’s disease. After ruling out other causes with routine imaging, a case of chickenpox-associated Takayasu’s arteritis with ischaemic stroke (with right hemiplegia) was diagnosed in the patient [

17]. Antiretroviral medicines generate oxidative tension and disrupt the regulation of nitric acid that could induce endothelial dysfunction and accelerate the initiation of TA [

18]. In 2019, the authors reported another case of a young woman who developed sudden-onset motor aphasia, right-sided hemiplegia and dysphagia upon awakening following a nocturnal fall to the floor. The patient used injectable contraceptives for ten years and was known to have hypertension (HTN). The subsequent cerebral angiograms revealed occlusion of the distal MCA and extensive proximal stenosis of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA). She was diagnosed with ischaemic stroke, rectus sheath haematoma, HTN and moyamoya disease [

17].

There are so many and other diseases such as moyamoya disease are regularly ignored in our country because here we have no facilities for orientation and research. More efficient imaging, for instance, creates a cycle of referral by postponing diagnosis and treatment in rural or semi-urban areas [

19].

Conclusions from this conversation, that is, each of these diagnoses, highlight the importance of raising awareness about aetiologies of stroke in young people and early treatment. What’s more, there are no national standards for maintaining registries or conducting research on strokes in young people. As disease increases with change due to genetic or acquired factors, here we need an up-to-date database of young stroke statistics and individual versus national guidelines.

To improve long-term outcomes, a prospective cohort follow-up is required that will include the details of risk factors and clinical and subclinical vascular diseases.

One such project is the Norwegian Stroke in the Young Study, which is a method to increase awareness of heredity and the development of arterial vascular disease. The Norwegian Stroke in the Young Study was started in 2010. The optimisation of stroke detection, prevention and early intervention is also targeted to decrease death, physical disability, cognitive impairment, stroke recurrence and other clinical vascular incidences [

20]. In a subgroup analysis of this ongoing study, ischaemic stroke was associated with increased carotid intima–media thickness in patients younger than 45 years and young/middle-aged individuals who suffered from stroke also had a very high prevalence of family history for cardiovascular disease [

6,

21]. The author of one study recommended a more widespread dissemination of information to enable the development of easily utilised risk assessment and molecular research tools [

21].

To promote awareness on the building of family history on cardiovascular events and its intervening measures to minimize disease inheritance, Bangladesh can replicate this study for initiation at the household level.

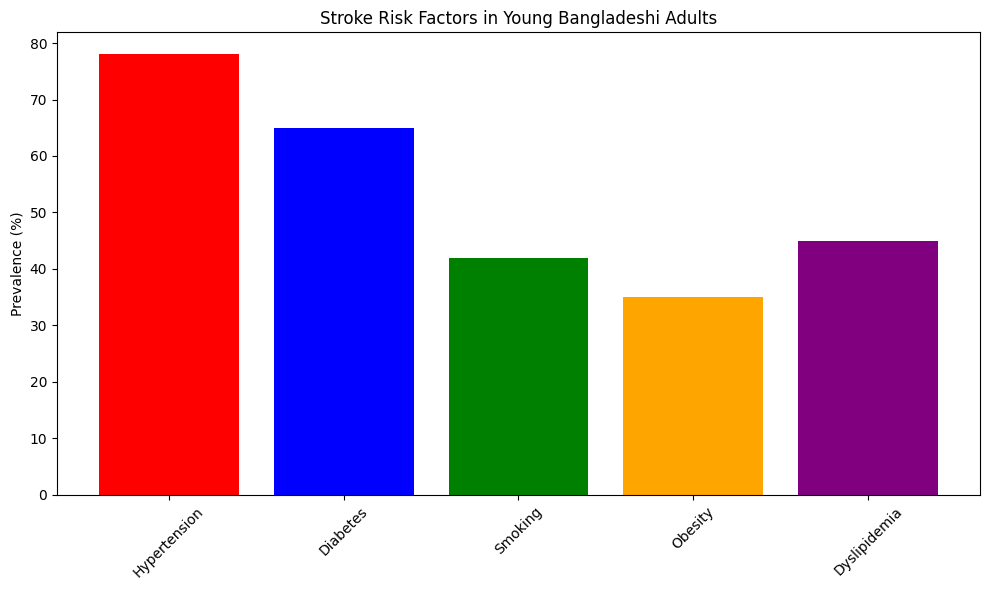

By concentrating on the teaching of hereditary hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes and atherosclerotic diseases to younger populations in low-resource areas, we can influence them against sedentary behavior. In addition, results of this study could be utilized to underscore age-specific profiles for stroke risk factors, prevention and more focused genetic research.

Also, the Stroke Awareness and Support Association (in the USA, a non-profit organization focused on raising awareness) provides support for young stroke victims and their families. There is parent help for the occasional day-in-day-out challenges of parents and carers with children who have post-stroke hemiplegia with therapy, clothes, school and general support [

22].

Bangladesh has a population of more than 173.6 million, with 5816 hospitals, 140,000 registered doctors, and only 142 neurologists who have completed training. Fortunately, in addition to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka Medical College Hospital and Mymensingh Medical College (MMC) Hospital, various divisional and super-specialized hospitals have also started neurology training programs. In Bangladesh, only 2153 technologists perform 250 CT scans and 92 MRIs using this technology [

23].

Suggestions

1. Strengthening the capacity for diagnosing and managing cases

The availability of specialized care for stroke varies across Bangladesh, especially in rural regions. Cutting-Edge Diagnostic Capacity The government needs to provide district and sub-district hospitals with state-of-the-art imaging equipment — MRIs, CT scans, and carotid ultrasounds. It is also important to establish standardized clinical standards needed for diagnosis and treatment of juvenile stroke patients amongst medical professionals in order to ensure consistent care.

2. Rise in data acquisition and monitoring for strokes

To understand the epidemiology of stroke among the young Bangladeshi population, a robust system for identifying and reporting cases is required. A National Stroke Registry would facilitate collecting these data in an organized fashion on treatment outcomes, risk factors, and prevalence. This register should be integrated into existing public health information systems to inform evidence-based resource allocation and policy developments.

3. Capacity building and training of the health workforce

Primary care physicians frequently lack adequate experience to diagnose and treat young stroke patients. Stroke training programs should be included in medical, nursing and paramedical schools to attenuate this problem. Curricula for continuing medical education programs should also be developed to provide emergency room personnel and family practitioners with the knowledge and skills they require to manage paediatric stroke.

4. Enhancing Strategies for Risk Reduction and Prevention

Implementing a statewide screening program through local healthcare centres is important considering the high prevalence of modifiable risk factors, including diabetes, hypertension, and smoking in young adults. These initiatives should focus on the early identification and modification of CVRFs, which will also provide specific interventions such as smoking suspension programs, dietary consultation, or campaigns to modify unhealthy habits.

5. Integrating policies and funding healthcare

Access to care for juvenile stroke victims is frequently limited due to financial reasons in Bangladesh. Providing public health insurance for stroke-related diagnostic visits, including emergency care and rehabilitation, would be important in the redistribution of this financial burden. In addition, the long-term outcome of young stroke survivors may be improved thanks to government allocation for critical stroke medications and rehabilitation services.

Table 1.

Strategies for Addressing Juvenile Stroke in Bangladesh.

Table 1.

Strategies for Addressing Juvenile Stroke in Bangladesh.

| Serial No |

Focus Area |

Key Actions Needed |

| 1 |

Diagnosis & Case Management |

Equip hospitals with advanced imaging (CT, MRI). Establish standardized clinical guidelines for consistent care. |

| 2 |

Data Acquisition & Monitoring |

Create a National Stroke Registry to track treatment, risk factors, and prevalence for informed policy |

| 3 |

Workforce Training |

Integrate stroke training into medical/nursing schools and provide continuing education for primary care and emergency staff |

| 4 |

Risk Reduction & Prevention |

Implement statewide screening for risk factors (e.g., hypertension) and promote cessation programs and healthy lifestyle campaigns |

| 5 |

Policy & Funding |

Provide public health insurance for stroke care and increase government funding for essential medications and rehabilitation services |

Conclusions

In order to tackle increased Young stroke incidence, there is a need for comprehensive multilevel preventive approach covering monitoring, infrastructure development, preventive initiatives, capacity building and financial support. Implementing these policy- and health system-oriented measures could result in a great deal of change in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of stroke in young people in Bangladesh.

Author Contributions

HKB: Concept, data collection, write the manuscript, data collection and statistical analysis. RB: review the manuscript, visualization, supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This study is a literature-based analysis and did not involve the collection of any primary patient data from Square Hospitals Ltd. Therefore, in accordance with the policies of the Ethical Committee of Square Hospitals Ltd., formal ethical approval and patient consent were not required for this work.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data & Materials

All the required information is available in the manuscript itself.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the patient for consenting to the publication of his case report.

Abbreviations

| WHO- World Health Organization |

| SLE- Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| DMC- Dhaka Medical College |

| MMC- Mymensingh Medical College |

| EDPS- Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale |

| IS- Ischaemic Stroke |

| HTN- Hypertension |

| MCA- Middle cerebral artery |

| MRI- Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CT- Computer tomography |

References

- L. Thau, V. Reddy, and P. Singh, “Anatomy, Central Nervous System,” in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. Accessed: Oct. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542179/.

- K. Gururangan, R. Kozak, and P. J. Dorriz, “Time is brain: detection of nonconvulsive seizures and status epilepticus during acute stroke evaluation using point-of-care electroencephalography,” J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis., vol. 34, no. 1, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Stack and J. W. Cole, “The Clinical Approach to Stroke in Young Adults,” in Stroke, S. Dehkharghani, Ed., Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications, 2021. Accessed: Oct. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572000/.

- “Bangladesh,” datadot. Accessed: Oct. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://data.who.int/countries/050.

- W. S. Smith, S. C. Johnston, and I. Hemphill J. Claude, “Cerebrovascular Diseases,” in Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 20th ed., J. L. Jameson, A. S. Fauci, D. L. Kasper, S. L. Hauser, D. L. Longo, and J. Loscalzo, Eds., New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education, 2018. Accessed: Oct. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=1160862264.

- M. G. George, “Risk Factors for Ischemic Stroke in Younger Adults: A Focused Update,” Stroke, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 729–735, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Islam et al., “Association of Cardiac Risk Factors with Socio Demographic Profile in Young Stroke Patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Bangladesh. An Observation Study of 100 Patients.,” Bangladesh Heart J., vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 81–87, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. S. Jacobs, B. Boden-Albala, I.-F. Lin, and R. L. Sacco, “Stroke in the young in the northern Manhattan stroke study,” Stroke, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 2789–2793, Dec. 2002. [CrossRef]

- T. Zakaria et al., “Age accounts for racial differences in ischemic stroke volume in a population-based study,” Cerebrovasc. Dis. Basel Switz., vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 376–380, 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Kujovich, “Factor V Leiden thrombophilia,” Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–16, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Wintzer-Wehekind et al., “Long-Term Follow-Up After Closure of Patent Foramen Ovale in Patients With Cryptogenic Embolism,” J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 278–287, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Jiang et al., “Prothrombin G20210A mutation is associated with young-onset stroke: the genetics of early-onset stroke study and meta-analysis,” Stroke, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 961–967, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Holmqvist, J. F. Simard, K. Asplund, and E. V. Arkema, “Stroke in systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies,” RMD Open, vol. 1, no. 1, p. e000168, 2015. [CrossRef]

- V. L. Feigin et al., “Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010,” The Lancet, vol. 383, no. 9913, pp. 245–255, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Hasan, “‘Risk Factors Analysis for Patients with Hemorrhagic Stroke: A Single Centre Study of Bangladesh,’” ResearchGate, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Numano, M. Okawara, H. Inomata, and Y. Kobayashi, “Takayasu’s arteritis,” Lancet Lond. Engl., vol. 356, no. 9234, pp. 1023–1025, Sept. 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Razzak, G. Kawnayn, F. Naznin, and Q. A. A. Rahman, “A case of Young Stroke due to Moyamoya Disease,” J. Armed Forces Med. Coll. Bangladesh, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 110–113, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Marincowitz, A. Genis, N. Goswami, P. De Boever, T. S. Nawrot, and H. Strijdom, “Vascular endothelial dysfunction in the wake of HIV and ART,” FEBS J., vol. 286, no. 7, pp. 1256–1270, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Saha and G. Banik, “Moyamoya Disease: A Rare Entity Report Of One Case,” J. Bangladesh Coll.

Physicians Surg., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 114–115, July 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Fromm et al., “The Norwegian Stroke in the Young Study (NOR-SYS): Rationale and design,” BMC

Neurol., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 89, July 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Øygarden et al., “Stroke patients’ knowledge about cardiovascular family history - the Norwegian Stroke in the Young Study (NOR-SYS),” BMC Neurol., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 30, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Singhal et al., “Recognition and management of stroke in young adults and adolescents,” Neurology,

vol. 81, no. 12, pp. 1089–1097, Sept. 2013. [CrossRef]

- https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290209478, “WHO Bangladesh Country Cooperation Strategy: 2020–2025.” Accessed: Oct. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290209478.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).