1. Introduction

Cutaneous wounds, including acute traumatic injuries and chronic ulcers, are common in outpatient practice and contribute substantially to morbidity, disability, and health care expenditures in the United States [

1,

2]. Chronic nonhealing wounds such as venous leg ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers, and pressure injuries affect millions of adults and are associated with impaired quality of life, limb loss, and premature mortality [

1,

3]. Recent economic evaluations estimate that chronic wounds impose tens of billions of dollars in annual costs on the US health care system, largely through outpatient visits, hospitalizations, procedures, and long-term supportive care [

4,

5].

Best practice guidance for wound management emphasizes meticulous local care, pressure relief, optimization of perfusion and glycemic control, and timely debridement, with systemic antibiotics reserved for wounds that show clear clinical signs of infection and are tailored to likely pathogens [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Routine use of systemic antibiotics for clinically uninfected or colonized wounds is discouraged because it offers little benefit and can promote antimicrobial resistance, drug-related adverse events, and Clostridioides difficile infection [

7,

10]. Topical antimicrobials and antiseptics may have a role in selected situations but should also be used judiciously as part of a broader wound hygiene and stewardship strategy [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Despite these recommendations, contemporary national patterns of antimicrobial use for cutaneous wounds in routine outpatient care remain incompletely characterized. It is not well-known which clinician specialties most commonly manage acute and chronic cutaneous wounds in office-based settings, how frequently antimicrobials are used during these visits, and which specific systemic and topical agents dominate prescribing. Understanding these patterns is important to identify high-yield targets for outpatient antimicrobial stewardship and to clarify the potential role of dermatology relative to primary care and surgical specialties.

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) is a long-standing, nationally representative survey of office-based physician visits in the United States conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics using a multistage probability design [

15,

16]. NAMCS captures patient diagnoses, physician specialty, and medications recorded at each sampled visit, which makes it well suited to describe national patterns of cutaneous wound care and associated antimicrobial use.

In this study, we used NAMCS data from 2011 to 2019 to provide a comprehensive description of outpatient cutaneous wound care in the United States. Our objectives were to: (1) estimate the national volume of acute and chronic cutaneous wound visits; (2) describe the specialty distribution of these visits; and (3) characterize antimicrobial prescribing patterns, including the relative use of systemic and topical agents and the most frequently used antimicrobial medications, overall and by wound type. We discuss these patterns in the context of antimicrobial stewardship and potential opportunities for enhanced dermatology involvement in wound care.

2. Results

2.1. Volume and Diagnostic Mix of Cutaneous Wound Visits

Across NAMCS survey years 2011–2019, an estimated 5.76 billion office-based outpatient visits occurred in the United States. Of these, 45.1 million visits (0.78%) had at least one diagnosis code corresponding to a cutaneous wound. Approximately 33 million visits involved acute wounds and 13 million involved chronic wounds. Acute wounds therefore accounted for about two thirds of cutaneous wound visits, with chronic wounds comprising the remaining one third.

The diagnostic mix was concentrated in a relatively small number of codes. The top twenty cutaneous wound diagnoses accounted for 62.7% of all wound diagnoses, 71.9% of acute wound diagnoses, and 89.5% of chronic wound diagnoses (

Supplementary Table S1). Acute wound visits were dominated by traumatic open wounds of the extremities, particularly open wounds of the thumb, lower leg, ear, fingers, and foot. Chronic wound visits were driven by non-pressure ulcers of the foot and lower limb and by pressure injuries, with the top five chronic diagnoses together accounting for 49.7% of chronic wound diagnoses.

In trend analyses of visit volumes, annual frequencies of overall, acute, and chronic cutaneous wound visits did not show statistically significant linear changes over time (all p ≥ 0.05), indicating that the outpatient burden of cutaneous wound visits remained relatively stable from 2011 to 2019.

2.2. Specialty Distribution of Wound Visits

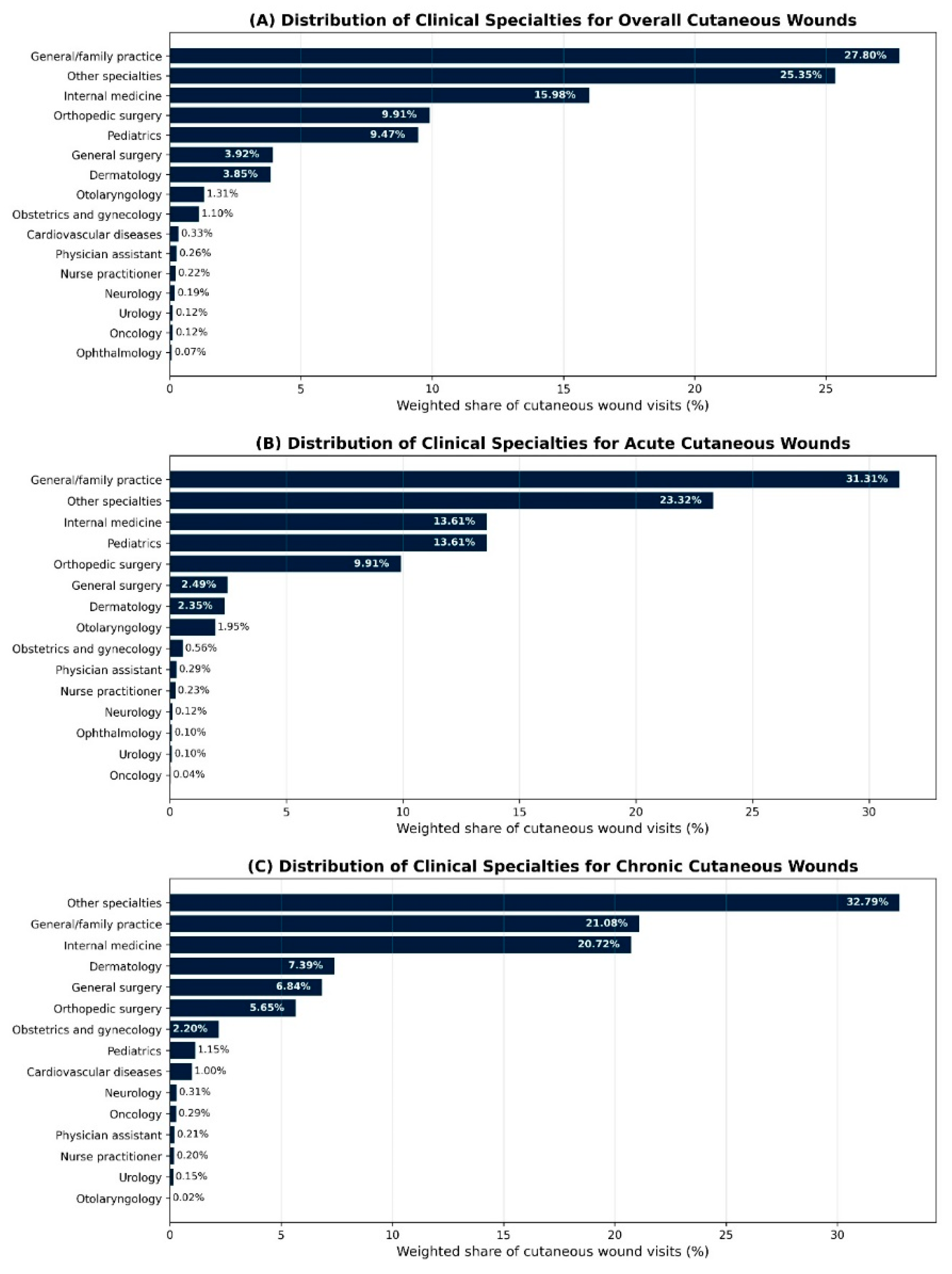

Detailed physician specialty information was available in NAMCS public-use files for 2011 and 2013–2016. In these years, primary care alone accounted for about half of cutaneous wound visits, and together with surgical specialties represented the majority of wound care. For overall cutaneous wound visits, general or family practice represented 27.8%, internal medicine 16.0%, pediatrics 9.5%, orthopedic surgery 9.9%, and general surgery 3.9%, with “other specialties” contributing 25.4% (

Table 2). “Other specialties” aggregates office-based physician subspecialties not listed separately in NAMCS (for example, rheumatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, nephrology, pulmonology, allergy and immunology, geriatrics, and physical medicine and rehabilitation). Dermatology managed 3.85% of all cutaneous wound visits, while otolaryngology, obstetrics and gynecology, cardiovascular diseases, and other subspecialties each accounted for smaller fractions.

Dermatology’s contribution differed by wound type. Dermatologists managed an estimated 2.35% of acute wound visits and 7.39% of chronic wound visits, indicating a relatively larger role in chronic wound care despite a small share of overall wound visits.

To align with the broader NAMCS physician category variable, which groups clinicians into primary care, surgical specialties, and medical specialties modeled on American Medical Association categories, we further collapsed individual specialties into these three groups. In this classification, general or family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics are grouped as primary care; orthopedic surgery, general surgery, otolaryngology, obstetrics and gynecology, urology, and related procedural fields are grouped as surgical specialties; and dermatology along with other internal medicine subspecialties are grouped as medical specialties. Using these categories, primary care clinicians were the most frequent providers of cutaneous wound care (

Table 3). Primary care accounted for 43.5% of acute wound visits, 51.3% of chronic wound visits, and 46.1% of all cutaneous wound visits. Surgical specialties accounted for 24.1% of acute, 29.9% of chronic, and 25.7% of overall wound visits, while medical specialties (including dermatology) accounted for 32.4%, 18.7%, and 28.1%, respectively.

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of cutaneous wound visits by specialty and by wound type.

2.3. Antimicrobial Use Among Medications at Wound Visits

Across all cutaneous wound visits, clinicians recorded an estimated 156.6 million medications. Of these, antimicrobials (antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals) represented 13.1% of all medications at wound visits, with antimicrobials accounting for 14.9% of medications in acute wound visits and 10.2% in chronic wound visits (

Table 1). This corresponded to approximately 20.5 million antimicrobial medications recorded at cutaneous wound visits over the study period.

Most medications used at wound visits were prescription products. Overall, 73.1% of medications were prescription-only, 22.1% could be provided as either prescription or over-the-counter, and only 2.2% were nonprescription drugs, a pattern that was similar for acute and chronic wounds (

Supplementary Table S2). Thus, more than 95% of medications used in wound visits were prescription-capable, suggesting that stewardship efforts in cutaneous wound care will primarily involve prescribed therapies

Among antimicrobial medications, systemic agents comprised 52.8% overall, including 60.5% of antimicrobials in acute wound visits and 42.6% in chronic wound visits, with the remainder being topical agents (values derived from NAMCS-weighted antimicrobial counts;

Supplementary Figure S2).

2.4. Composition of Specific Antimicrobial Agents

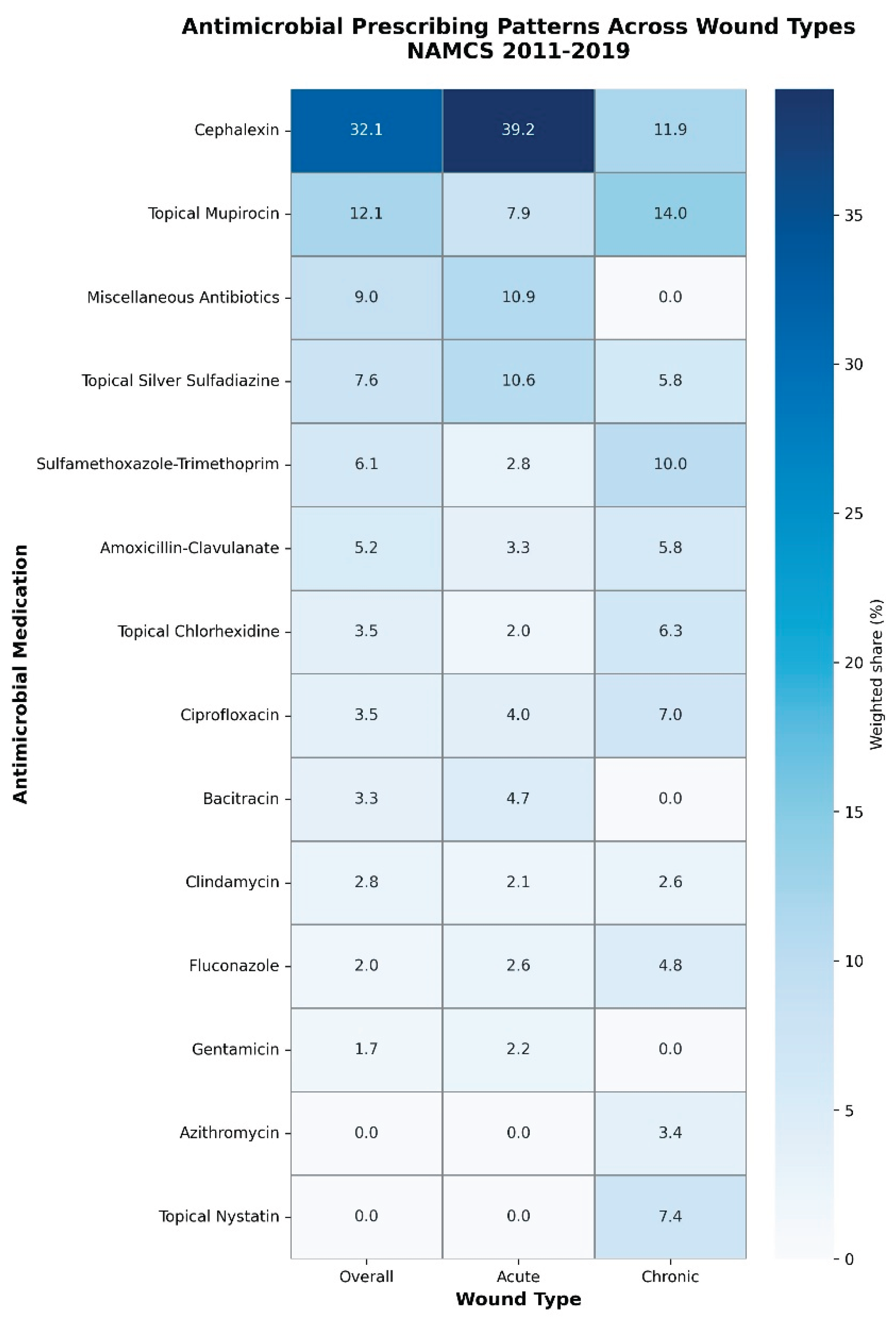

Antimicrobial use during cutaneous wound visits relied heavily on a small number of core agents (

Table 1;

Supplementary Figure S1). Using antimicrobial medications as the denominator, the first-generation cephalosporin cephalexin was the most commonly used agent overall, accounting for 32.1% of all antimicrobial medications and 4.22% of all medications recorded at cutaneous wound visits. Topical mupirocin was the second most frequently used antimicrobial (12.1% of antimicrobial medications; 1.59% of all medications), followed by a grouped “miscellaneous antibiotic” category.

In acute wound visits, cephalexin was even more dominant, representing 39.2% of antimicrobial medications and 5.84% of all medications, with topical mupirocin and silver sulfadiazine also commonly used (

Table 1). In chronic wound visits, the antimicrobial profile was more heterogeneous. Topical mupirocin (14.0% of antimicrobial medications), cephalexin (11.9%), trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (10.0%), topical nystatin (7.4%), topical chlorhexidine (6.3%), and fluconazole (4.8%) were among the most frequently used agents, reflecting a mix of systemic antibiotics, topical antibacterials, and topical antifungals (

Table 1;

Supplementary Figure S3).

Across all wound visits, the top three antimicrobial agents (cephalexin, topical mupirocin, and miscellaneous antibiotics) accounted for 53.3% of all antimicrobial medications, the top five agents for 67.0%, and the top ten for 85.3%. Concentration was strongest in acute wounds, where the top three agents accounted for 60.7% and the top ten for 88.0% of antimicrobial medications. In chronic wounds, the top three and top five agents represented 35.9% and 50.4% of antimicrobial medications, respectively, and the top ten accounted for 76.5%, consistent with a more diffuse antimicrobial profile (

Table 1). These patterns are illustrated in

Figure 2, which presents a heatmap of the most commonly used antimicrobial agents overall and stratified by wound type.

2.5. Time Trends in Antimicrobials and Specialty Mix

In trend analyses, the proportions of antimicrobials, antibiotics, and antifungals among medications at cutaneous wound visits did not show statistically significant linear changes over time (all p ≥ 0.09). The only significant temporal pattern was a modest increase in the proportion of antiviral agents among antimicrobial medications in chronic wound visits (p = 0.037), while antiviral use in acute wound visits remained low and stable (

Supplementary Table S3).

Similarly, there were no statistically significant linear trends in the relative contributions of primary care, surgical, or medical specialties to acute, chronic, or overall cutaneous wound visits during the study period (all p > 0.05;

Supplementary Table S4). The specialty mix of outpatient cutaneous wound care therefore appeared stable over time.

3. Discussion

In this nationally representative analysis of US office-based visits, cutaneous wound care occupied a small but stable share of ambulatory practice, with approximately one in 120 visits involving an acute or chronic cutaneous wound. Acute wounds accounted for about two thirds of visits and were dominated by traumatic open injuries of the extremities, whereas chronic wounds comprised about one third and were largely lower-extremity ulcers and pressure injuries. These patterns are consistent with prior work showing that chronic wounds, particularly lower-limb ulcers, account for a disproportionate share of morbidity and costs despite representing a minority of encounters [

4,

17,

18].

Antimicrobial use during wound visits was substantial and concentrated in a limited repertoire of agents. Across all wound visits, more than one in eight medications was an antimicrobial, and just a few drugs accounted for most antimicrobial use. Cephalexin alone represented roughly one third of antimicrobial medications overall and nearly 40% in acute wound visits, while topical mupirocin was the second most frequently used agent. Cephalexin dominates acute wound prescribing because it is an oral, inexpensive, first-generation cephalosporin with good activity against common gram-positive skin pathogens, is widely recommended as a first-line oral option for uncomplicated nonpurulent cellulitis and other skin and soft tissue infections and is deeply familiar to outpatient prescribers. In chronic wound visits, antimicrobial selection was more heterogeneous but still centered on a small group of systemic antibiotics and topical antibacterials and antifungals.

Antimicrobial stewardship and wound care guidelines emphasize that systemic antibiotics should be reserved for clinically infected wounds and that colonized or noninfected wounds should be managed with local wound care, debridement, offloading, and optimized perfusion rather than routine systemic therapy [

7,

9,

19,

20,

21]. The predominance of systemic agents among antimicrobials in our analysis, particularly for acute wounds, may be appropriate in many high-risk traumatic injuries but also suggests persistent opportunities for stewardship. In the absence of clinical details regarding infection status, culture results, or systemic signs, we cannot determine the appropriateness of individual prescriptions. However, the stability of antimicrobial shares over nearly a decade, despite increasing attention to antimicrobial stewardship in wound care, supports the need for targeted outpatient interventions. These might include decision support for distinguishing infection from colonization, clearer recommendations on when systemic therapy adds value beyond local care, and more consistent use of narrow-spectrum or topical options when indicated by wound characteristics and microbiologic risk.

The heavy and sustained use of topical antimicrobials, particularly mupirocin, also warrants attention. Mupirocin is an important agent for decolonization and treatment of localized

Staphylococcus aureus (

S. aureus) infections, yet repeated or widespread use has been associated with increased resistance in

S. aureus and coagulase-negative

staphylococci [

22,

23,

24]. Our findings that mupirocin is one of the most frequently used agents in both acute and chronic wound care highlight the potential value of wound-specific stewardship guidance that addresses not only systemic antibiotics but also topical agents and antiseptics. Aligning topical antimicrobial use with guideline-supported indications could help preserve efficacy while minimizing selection pressure for resistance.

In chronic wound care, the more diverse antimicrobial profile that includes topical nystatin, systemic antifungals, and broad-spectrum antibiotics raises questions about how consistently treatment aligns with evidence-based recommendations. Chronic lower-limb ulcers and pressure injuries are frequently colonized by polymicrobial flora rather than overtly infected [

25,

26,

27], and antimicrobial therapy that is not targeted to clearly defined infection may not improve healing while increasing the risks of resistance, drug toxicity, and

Clostridioides difficile infection. Stewardship efforts in chronic wound care therefore need to address not only the volume of systemic antibiotics but also the indications for antifungal and broad-spectrum antibacterial agents, and to reinforce the central role of local wound care, debridement, and optimization of perfusion and comorbid conditions.

The specialty distribution of wound visits underscores that primary care clinicians and surgical specialties are the principal providers of ambulatory wound care in the United States. Primary care accounted for nearly half of acute, chronic, and overall wound visits, and surgical specialties contributed an additional quarter to one third. Dermatology managed fewer than 4% of overall wound visits but a relatively larger share of chronic wound visits, approaching 7% of chronic encounters. This pattern suggests that dermatologists are more often involved when wounds are complex or refractory, yet they remain responsible for only a small fraction of chronic wound care nationally. Survey data from US dermatology residents indicate that most trainees do not feel adequately prepared to manage acute or chronic wounds and that fewer than half intend to incorporate wound care into their future practice, which suggests that gaps in residency training may contribute to dermatology’s limited role in this area [

28]. Other factors, such as competing procedural priorities and financial or organizational incentives may also play a role, although these have not been systematically studied. Given dermatology’s expertise in skin biology, inflammation, and cutaneous infection, expanding dermatology involvement through multidisciplinary wound clinics, structured referral pathways, and teledermatology consultation could help support more precise diagnosis, biopsy and culture when indicated, and evidence-based antimicrobial selection.

Our results also show that visit volumes, specialty mix, and antimicrobial shares remained statistically stable from 2011 to 2019, with the exception of a modest increase in antiviral use for chronic wounds. The stability of wound visit frequency suggests that the outpatient burden of cutaneous wounds has not diminished over time, despite advances in preventive care and chronic disease management. The absence of major shifts in specialty mix indicates that primary care and surgical specialists have continued to shoulder most wound care responsibilities, without a measurable increase in dermatology’s contribution. Similarly, the lack of clear downward trends in antimicrobial shares implies that outpatient stewardship efforts have not yet translated into detectable reductions in overall antimicrobial use for wounds at the national level. These findings provide a useful pre–COVID-19 benchmark against which future changes in practice, including those driven by evolving stewardship initiatives and post-pandemic care models, can be assessed.

This study has several strengths. We used a large, nationally representative dataset with complex survey weights that captures office-based care across multiple specialties over nearly a decade. We applied consistent case definitions to distinguish acute from chronic wounds and mapped medications to clinically meaningful antimicrobial categories, which allowed us to characterize not only whether antimicrobials were used but also which specific agents and classes predominated. The integration of specialty, diagnosis, and medication information within a single dataset provided a comprehensive view of who delivers cutaneous wound care and how antimicrobials are deployed in routine outpatient practice.

Important limitations should be noted. NAMCS is a visit-based survey, so repeated visits by the same patient cannot be linked and we cannot evaluate longitudinal outcomes, treatment duration, or time to healing. The dataset lacks detailed clinical information on wound severity, microbiologic results, and presence of systemic signs of infection, which precludes assessment of whether antimicrobial prescribing was clinically appropriate. Diagnosis coding may be incomplete or heterogeneous, especially for specific chronic wound subtypes such as diabetic foot ulcers, and some complex wounds may be underrepresented if they are preferentially managed in hospital-based or non–office settings. Specialty information is available only for selected years and is aggregated into broad categories that may mask variation within specialties. Finally, our estimates describe the share of antimicrobial medications among all medications recorded, not the proportion of visits in which at least one antimicrobial was prescribed, and therefore should be interpreted as patterns of drug selection rather than visit-level prescribing rates.

Despite these limitations, this analysis provides a national overview of outpatient cutaneous wound care in the pre COVID-19 era and highlights several opportunities to improve practice. For antimicrobial stewardship, priorities include refining criteria for systemic therapy, encouraging judicious use of high-volume agents such as cephalexin and mupirocin, and developing wound-focused stewardship tools that are usable in primary care and surgical settings where most wound care occurs. For specialty allocation, there is a rationale for increasing dermatology’s participation in chronic wound management through collaborative care models that integrate dermatologists with primary care, surgery, vascular medicine, podiatry, and infectious diseases. Future research should examine how specific stewardship interventions and multidisciplinary models influence antimicrobial use, resistance patterns, and patient-centered outcomes in both acute and chronic cutaneous wounds.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source and Study Design

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) public use files from 2011 to 2019. NAMCS is an annual, nationally representative survey of visits to non-federal, office-based physicians in the United States conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics using a multistage probability design with visit weights, strata, and primary sampling units. NAMCS samples non-federal, office-based physicians; visits to hospital-based outpatient clinics, emergency departments, and settings where nonphysician clinicians are the primary providers are not captured in this survey and were therefore outside the scope of our analysis.

4.2. Case Definitions for Cutaneous Wounds

Cutaneous wound visits were identified using all available diagnosis fields. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD 9 CM) codes were used before October 2015 and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD 10 CM) codes thereafter.

We defined cutaneous wounds as diagnoses representing an acute or chronic break in skin integrity. Acute wounds included traumatic open or complex wounds and thermal injuries of the skin and extremities. Chronic wounds included pressure injuries and non-pressure lower extremity ulcers such as venous, arterial, and diabetic ulcers. Visits with at least one acute wound code were classified as acute. Visits with at least one chronic wound code were classified as chronic. The full code lists are provided in Supplementary Methods

Table S1.

4.3. Medications and Antimicrobial Classification

NAMCS records medications prescribed, provided, or continued at each visit (up to eight medications per visit in 2011–2013 and up to thirty thereafter). All medications recorded at cutaneous wound visits were abstracted. Antimicrobial medications were defined as systemic or topical antibiotics, antifungals, or antivirals based on NAMCS therapeutic classes and generic names. Topical antiseptics, dressings, advanced wound products, biologic agents, and other non-antimicrobial therapies were not counted as antimicrobials. Antimicrobials were classified by route (systemic or topical) and by class (antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral). Mapping details are provided in Supplementary Methods

Table S2.

Medication analyses used individual drug mentions as the unit of analysis and described the proportion of antimicrobial medications among all medications recorded at wound visits.

4.4. Clinician Specialty and Provider Categories

Physician specialty was described using both detailed specialty codes (available for 2011 and 2013–2016) and a broader NAMCS physician category variable that groups specialties as primary care, surgical specialties, or medical specialties. General or family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics were classified as primary care. Orthopedic surgery, general surgery, otolaryngology, obstetrics and gynecology, urology, and related fields were classified as surgical specialties. Dermatology and other internal medicine subspecialties were classified as medical specialties. Dermatology specific estimates were also reported when detailed codes were available. The specialty mapping is shown in Supplementary Methods

Table S3.

4.5. Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

Primary outcomes were: (1) nationally weighted counts and proportions of acute, chronic, and overall cutaneous wound visits among all office-based physician visits; (2) the distribution of wound visits across specialties; and (3) the proportion and composition of antimicrobial medications at wound visits. Survey procedures that incorporate NAMCS visit weights, strata, and primary sampling units were used to generate national estimates. All weighted counts represent survey weighted national estimates of visits or medication mentions. Linear trends over time were evaluated by fitting survey-weighted linear regression models with calendar year as a continuous predictor. Two-sided p values for trend were obtained from the coefficient for calendar year, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Following National Center for Health Statistics guidance, estimates based on fewer than 30 unweighted observations or with a relative standard error greater than thirty percent were considered unreliable and were suppressed or combined. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). NAMCS public use files contain de identified data, and secondary analyses are considered exempt from additional institutional review board review.

5. Conclusions

In this nationally representative analysis, cutaneous wound visits accounted for a small but stable share of US office-based care and were managed largely in primary care and surgical settings. Antimicrobials made up a substantial proportion of medications at these visits and were dominated by a few systemic and topical agents, with little evidence of change over time. These patterns highlight opportunities to strengthen outpatient antimicrobial stewardship for acute and chronic wounds and to expand dermatology’s role within multidisciplinary wound care models, and they provide a pre COVID 19 benchmark against which the impact of future stewardship and care delivery initiatives can be assessed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AG; methodology, AG, SRF; formal analysis, RJC, JP; writing original draft preparation, AG, RJC, JP, SRF; writing—review and editing, AG; visualization, AG, RJC; supervision, AG, SRF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study used deidentified public-use data from NAMCS and did not involve direct interaction with human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

NAMCS public-use data files and documentation for 2011–2019 are available from the National Center for Health Statistics website (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Center for Health Statistics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for making NAMCS data publicly available. Additional colleagues who contributed to data cleaning or figure preparation can be acknowledged here.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Grada reports unpaid service as Senior Collaborator for the Global Burden of Disease Study/Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; editorial roles as Associate Editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology and the International Journal of Dermatology; service as Physician Editor for VisualDx; membership on the Board of Directors for the Biology of Skin Foundation; and employment as Medical Director at AbbVie, outside the submitted work. Dr. Feldman reports research support, consulting fees, and/or speaking honoraria from Galderma; GSK/Stiefel; Almirall; LEO Pharma; Boehringer Ingelheim; Mylan; Celgene; Pfizer; Valeant; AbbVie; Samsung; Janssen; Eli Lilly; Menlo; Merck; Novartis; Regeneron; Sanofi; Novan; Qurient; National Biological Corporation; Caremark; Advance Medical; Sun Pharma; Suncare Research; Informa; UpToDate; and the National Psoriasis Foundation; he is founder and majority owner of DrScore.com and founder and part owner of Causa Research, outside the submitted work. The other authors report no disclosures.

Abbreviations

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019

ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

ICD-10-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

NAMCS: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

SAS: Statistical Analysis System

References

- Falanga, V.; Isseroff, R.R.; Soulika, A.M.; Romanelli, M.; Margolis, D.; Kapp, S.; Granick, M.; Harding, K. Chronic wounds. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2022, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.; Knusel, K.D.; Ezaldein, H.H.; Honaker, J.S.; Bordeaux, J.S.; Scott, J.F. Incremental health care expenditure of chronic cutaneous ulcers in the United States. JAMA dermatology 2019, 155, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, N.; Phillips, C.; Harding, K. A narrative review of the epidemiology and economics of chronic wounds. British Journal of Dermatology 2022, 187, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, C.K. Human Wound and Its Burden: Updated 2025 Compendium of Estimates. Advances in Wound Care 2025, 14, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queen, D.; Harding, K. Estimating the cost of wounds both nationally and regionally within the top 10 highest spenders. International wound journal 2024, 21, e14709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizing, E.; Schreve, M.A.; Stuart, J.W.C.; de Vries, J.-P.P.; Çağdaş, Ü. Treatment of clinically uninfected diabetic foot ulcers, with and without antibiotics. Journal of Wound Care 2024, 33, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J.; Ousey, K.; Rippon, M.; Rogers, A.; Pastar, I.; Lev-Tov, H. Applying Antimicrobial Strategies in Wound Care Practice: A Review of the Evidence. International wound journal 2025, 22, e70684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, P.J.; Barreto, R.T.; Barrois, B.M.; Gryson, L.G.; Meaume, S.; Monstrey, S.J. Update on the role of antiseptics in the management of chronic wounds with critical colonisation and/or biofilm. International wound journal 2021, 18, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, D.L.; Bisno, A.L.; Chambers, H.F.; Dellinger, E.P.; Goldstein, E.J.; Gorbach, S.L.; Hirschmann, J.V.; Kaplan, S.L.; Montoya, J.G.; Wade, J.C. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases 2014, 59, e10–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlam, T.F.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Abbo, L.M.; MacDougall, C.; Schuetz, A.N.; Septimus, E.J.; Srinivasan, A.; Dellit, T.H.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T.; Fishman, N.O. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clinical infectious diseases 2016, 62, e51–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefian, F.; Hesari, R.; Jensen, T.; Obagi, S.; Rgeai, A.; Damiani, G.; Bunick, C.G.; Grada, A. Antimicrobial wound dressings: a concise review for clinicians. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsky, B.A.; Hoey, C. Topical antimicrobial therapy for treating chronic wounds. Clinical infectious diseases 2009, 49, 1541–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.D.; Leaper, D.J.; Assadian, O. The role of topical antiseptic agents within antimicrobial stewardship strategies for prevention and treatment of surgical site and chronic open wound infection. Advances in wound care 2017, 6, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Kelly, S.; Farah, B.; Singh, S.; Chen, L.; Hsieh, S.; Kaunelis, D. Context and Policy Issues. In Drugs for Chronic Hepatitis C Infection: Clinical Review [Internet]; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aparasu, R.R.; Rege, S. Use of national databases and surveys to evaluate prescribing patterns and medication use. In Contemporary Research Methods in Pharmacy and Health Services; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 527–539. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, A.S.; Ranpariya, V.; Fleischer, A.B., Jr.; Feldman, S.R. How the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey has been used to identify health disparities in the care of patients in the United States. Journal of the National Medical Association 2021, 113, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, S.R.; Carter, M.J.; Fife, C.E.; DaVanzo, J.; Haught, R.; Nusgart, M.; Cartwright, D. An economic evaluation of the impact, cost, and medicare policy implications of chronic nonhealing wounds. Value in health 2018, 21, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frykberg, R.G.; Banks, J. Challenges in the treatment of chronic wounds. Advances in wound care 2015, 4, 560–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Excellence, N.I.f.C. Leg ulcer infection: antimicrobial prescribing. NG152-NICE Guideline 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, P.; Duerden, B.; Armstrong, D.G. Wound microbiology and associated approaches to wound management. Clinical microbiology reviews 2001, 14, 244–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutting, K.; Harding, K. Criteria for identifying wound infection. Journal of Wound Care 1994, 3, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poovelikunnel, T.; Gethin, G.; Humphreys, H. Mupirocin resistance: clinical implications and potential alternatives for the eradication of MRSA. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2015, 70, 2681–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashi, M.; Hajikhani, B.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D.; van Belkum, A.; Goudarzi, M. Mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of global antimicrobial resistance 2020, 20, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefzy, E.M.; Radwan, T.E.; Hozayen, B.M.; Mahmoud, E.E.; Khalil, M.A. Antiseptics and mupirocin resistance in clinical, environmental, and colonizing coagulase negative Staphylococcus isolates. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control 2023, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjødsbøl, K.; Christensen, J.J.; Karlsmark, T.; Jørgensen, B.; Klein, B.M.; Krogfelt, K.A. Multiple bacterial species reside in chronic wounds: a longitudinal study. International wound journal 2006, 3, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versey, Z.; da Cruz Nizer, W.S.; Russell, E.; Zigic, S.; DeZeeuw, K.G.; Marek, J.E.; Overhage, J.; Cassol, E. Biofilm-innate immune interface: contribution to chronic wound formation. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 648554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; De Angelis, B.; Pea, F.; Scalise, A.; Stefani, S.; Tasinato, R.; Zanetti, O.; Dalla Paola, L. Challenges in the management of chronic wound infections. Journal of global antimicrobial resistance 2021, 26, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, E.S.; Ingram, A.; Landriscina, A.; Tian, J.; Kirsner, R.S.; Friedman, A. Identifying an Education Gap in Wound Care Training in United States Dermatology. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD 2015, 14, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).