1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed neoplasm in women and one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide. In 2020, more than 2.3 million new cases and approximately 685,000 deaths were reported, figures that continue to rise and reflect both population growth and persistent disparities in access to diagnosis and treatment (WHO, 2024; GLOBOCAN, 2020). The disease encompasses a heterogeneous spectrum of molecular subtypes such as luminal A, luminal B, HER2 positive, and triple negative, whose biological differences determine their aggressiveness, therapeutic response, and prognosis (Bianchini et al., 2016). Despite advances in targeted therapies and immunotherapies, access to high-cost drugs remains limited, especially in contexts where economic inequalities restrict the implementation of personalized medicine strategies. This gap between scientific development and clinical availability has created an urgent need for more accessible, reproducible, and versatile tools that can be integrated into early detection and selective treatment programs.

In this context, aptamers have emerged as a promising alternative to conventional antibodies. These are DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected through the SELEX process (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment), capable of folding into specific three-dimensional structures that recognize molecular targets with high affinity and specificity (Tuerk & Gold, 1990; Ellington & Szostak, 1990). Unlike proteins, aptamers can be produced by chemical synthesis, allowing for precise control over their composition, high batch-to-batch reproducibility, and substantially lower costs. Additionally, their chemical modifications—such as 2'-O-methyl substitutions, phosphorothioate linkages, or polymer conjugation—enhance their stability against nucleases and prolong their circulating half-life (Sefah et al., 2010; Amero et al., 2021). These characteristics have driven their exploration as “synthetic antibodies” with diagnostic and therapeutic potential, especially in oncology, where molecular precision and cost-effectiveness are convergent priorities.

The growing body of evidence demonstrates that aptamers can transform clinical practice in breast cancer by combining analytical sensitivity, molecular specificity, and technological scalability. In the diagnostic field, electrochemical, optical, and magneto-spectroscopic biosensors have been developed that can detect tumor biomarkers such as HER2, MUC1, EpCAM, and PD-L1 with high sensitivity and minimal invasiveness (Jo et al., 2015; Su et al., 2025). For prognosis, they enable the identification of aggressive subpopulations and extracellular vesicles associated with recurrence or therapeutic resistance (Huang et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022), while in therapy, aptamer–drug conjugates, aptamer–siRNA conjugates, and theranostic platforms have demonstrated antitumor efficacy with reduced systemic toxicity (Camorani et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2025). Nevertheless, challenges remain: their in vivo half-life is still limited, clinical validation is still incipient, and the transition to controlled studies faces regulatory and economic obstacles. Understanding and overcoming these limitations is essential to establish aptamers as next-generation clinical tools, capable of reducing disparities in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment on a global scale. Within this framework, the present review seeks to integrate and critically analyze the available evidence on the use of aptamers in breast oncology, highlighting both their experimental robustness and the opportunities for translational development that could make them a feasible, economical, and precise strategy for early detection, prognostic monitoring, and targeted therapy of breast cancer.

1.1. Aptamers: Development and Advantages

Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides capable of recognizing a wide range of targets with high affinity and specificity, from small molecules to proteins, cells, and even entire tissues. Their discovery in the early 1990s by Tuerk and Gold, and independently by Ellington and Szostak, marked a milestone in molecular biology by demonstrating that random RNA sequences could acquire molecular recognition functions through an in vitro selection process known as SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment) (Tuerk & Gold, 1990; Ellington & Szostak, 1990). This method, based on iterative cycles of binding, separation, and amplification, allows for the isolation of sequences able to fold into specific three-dimensional structures to interact with their target. Each selection cycle increases the enrichment of higher-affinity sequences, generating an optimized population of nucleotide ligands. Over time, SELEX has diversified into variants that incorporate physiological conditions (cell-SELEX, tissue-SELEX, in vivo-SELEX) or chemically modified libraries that expand the stability and structural diversity of aptamers (Sefah et al., 2010; Maradani et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the overall efficiency of the process remains a technical challenge: comparative studies estimate success rates below 1% from the initial libraries, and effective enrichment critically depends on target purity, selection conditions, and amplification parameters (Blind & Blank, 2015).

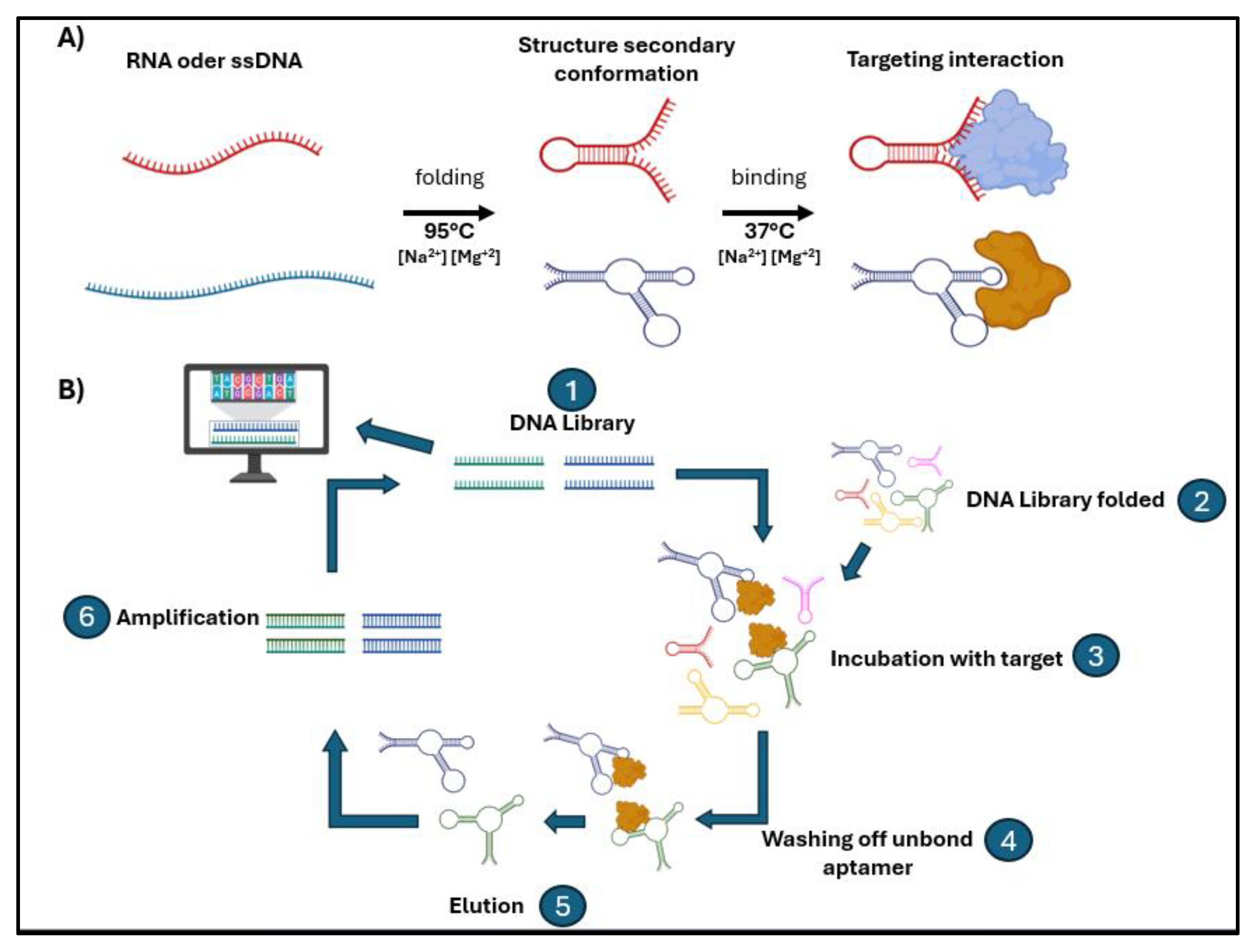

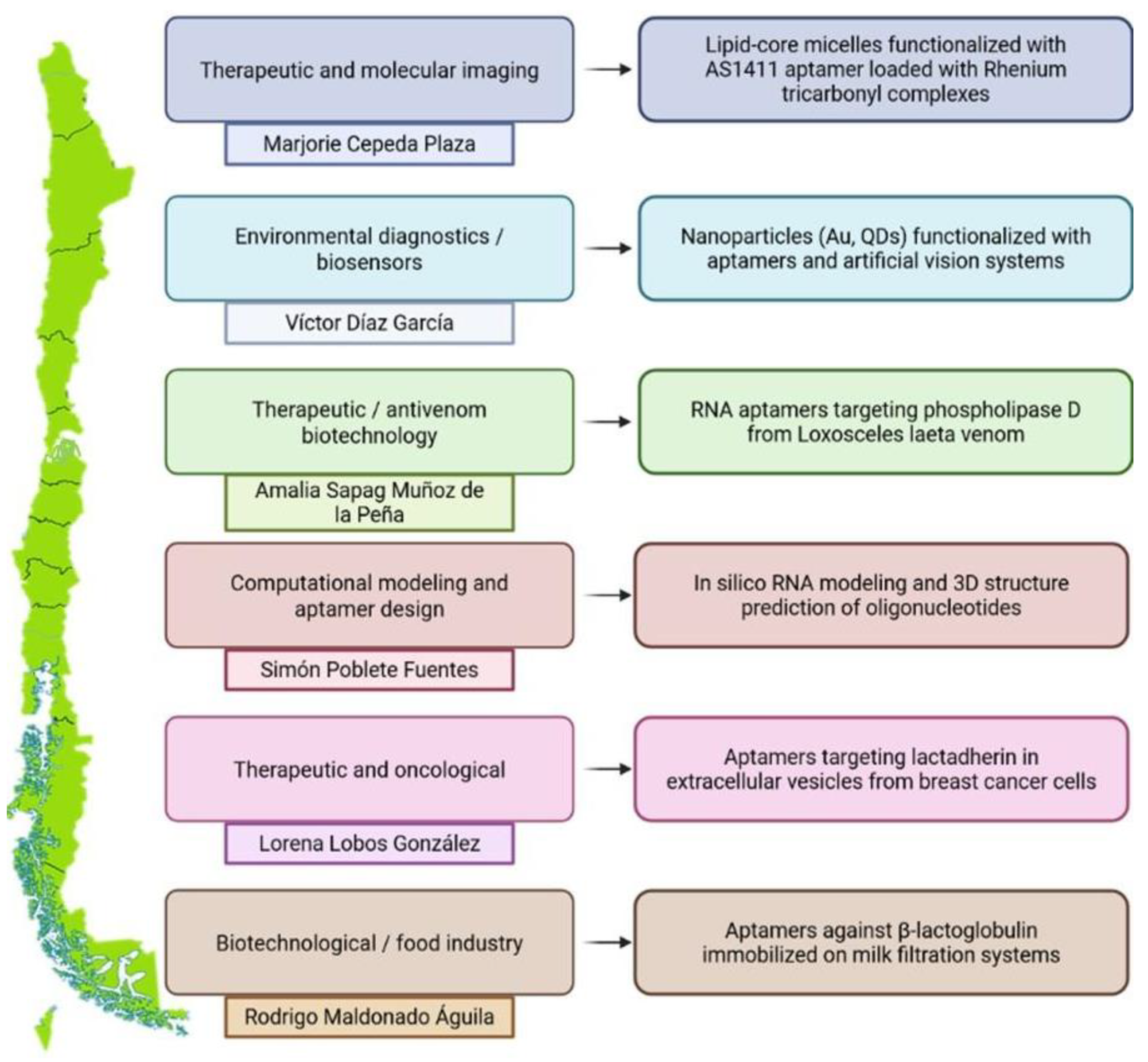

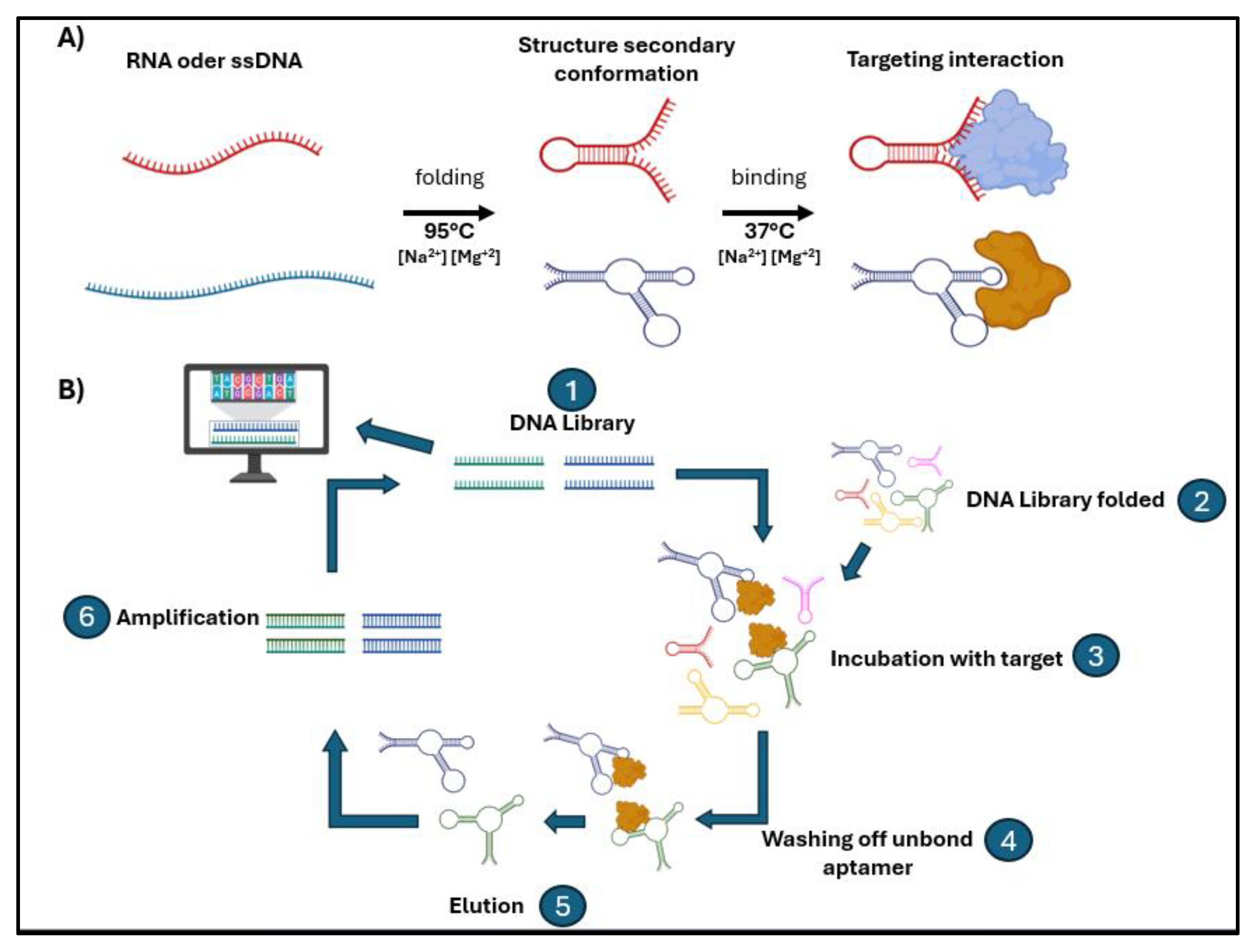

Figure 1.

Functionality aptamer and diagram of selection aptamer SELEX mediated system. (A) The general mechanism of action of aptamers, which can be single-stranded RNA or DNA (ssDNA) molecules, is shown. When subjected to appropriate conditions, these sequences adopt secondary and tertiary structures defined by intramolecular folding processes, forming loops, hairpins, and double-stranded regions. These three-dimensional conformations allow them to be recognized and bind specifically to a target molecule, which can be a protein, a peptide, a whole cell, or even a small metabolite. (B) The systematic selection of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) process, used to isolate aptamers with high affinity for a target molecule, is outlined. The procedure begins with a library of random DNA or RNA sequences, which is folded and incubated with the target molecule. Aptamers that do not show affinity are eliminated during the washing off stage, while aptamers bound to the target are eluted and subsequently amplified by PCR to generate a new enriched population. This cycle of selection, binding, washing, elution, and amplification is repeated multiple times until aptamers with high specificity and affinity are obtained, which can then be characterized and synthesized using bioinformatics tools.

Figure 1.

Functionality aptamer and diagram of selection aptamer SELEX mediated system. (A) The general mechanism of action of aptamers, which can be single-stranded RNA or DNA (ssDNA) molecules, is shown. When subjected to appropriate conditions, these sequences adopt secondary and tertiary structures defined by intramolecular folding processes, forming loops, hairpins, and double-stranded regions. These three-dimensional conformations allow them to be recognized and bind specifically to a target molecule, which can be a protein, a peptide, a whole cell, or even a small metabolite. (B) The systematic selection of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) process, used to isolate aptamers with high affinity for a target molecule, is outlined. The procedure begins with a library of random DNA or RNA sequences, which is folded and incubated with the target molecule. Aptamers that do not show affinity are eliminated during the washing off stage, while aptamers bound to the target are eluted and subsequently amplified by PCR to generate a new enriched population. This cycle of selection, binding, washing, elution, and amplification is repeated multiple times until aptamers with high specificity and affinity are obtained, which can then be characterized and synthesized using bioinformatics tools.

1.2. Advantage of Using Aptamers as Clinical Tools

The molecular recognition of an aptamer is based on its three-dimensional architecture. These molecules can adopt stable secondary and tertiary structures—such as hairpins, pseudoknots, i-motifs, or G-quadruplexes—that generate specific cavities and contact surfaces. The interactions with the target include hydrogen bonds, base stacking, electrostatic and hydrophobic forces, allowing discrimination between isoforms or even variants with a single amino acid change (Shraim et al., 2022; Edwards et al., 2024). Critically, this structural specificity does not depend on an immune response, which distinguishes aptamers from conventional antibodies and grants them low immunogenicity. Added to this are chemical modifications at the nucleotides or at the 3’ and 5’ ends—such as 2’-O-methyl substitutions, phosphorothioate linkages, PEG conjugation, or metal anchoring—that increase nuclease resistance and prolong plasma half-life up to eight hours in animal models, enhancing structural stability without compromising affinity or selectivity (Amero et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2022). These adaptations confer aptamers with functional versatility that goes beyond their role as experimental probes, allowing their integration into advanced diagnostic and therapeutic platforms.

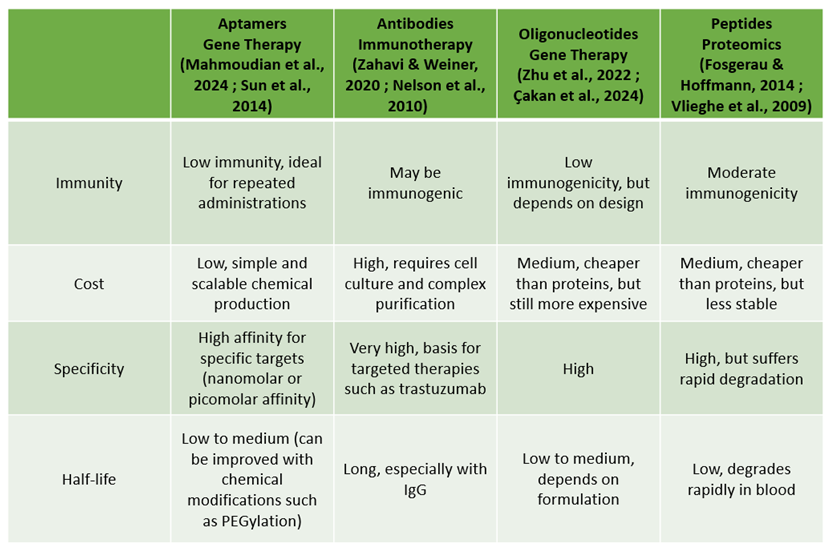

Table 1.

General comparison between aptamers and therapeutic platforms against breast cancer.

Table 1.

General comparison between aptamers and therapeutic platforms against breast cancer.

Compared to monoclonal antibodies or other protein-based therapeutic platforms, aptamers offer substantial advantages. Their smaller molecular size (10–30 kDa versus ~150 kDa for an IgG) facilitates tissue penetration and access to sterically restricted epitopes (Domsicova et al., 2024). Chemical synthesis eliminates the need for cell cultures, reduces batch-to-batch variability, and simplifies large-scale production, lowering costs and development times (Agnello et al., 2021). Additionally, their thermal stability and ability to regenerate after denaturation allow for their reuse in detection platforms and repeated assays without loss of activity. Typical binding affinities range from nanomolar to even picomolar, comparable to or greater than those of monoclonal antibodies, which strengthens their potential for high-precision clinical applications (Blind & Blank, 2015; Shraim et al., 2022). However, their limitations should be recognized: rapid renal clearance of small molecules (<30 kDa), susceptibility to degradation in complex biological matrices, and limited comparative validation in clinical trials still restrict their routine implementation. In summary, advances in SELEX selection and chemical engineering have transformed aptamers into a robust molecular platform capable of combining the specificity of antibodies with the synthetic flexibility of oligonucleotides. Their development marks a convergence between structural biology and applied nanotechnology, offering a solid foundation for strategies of early diagnosis, prognosis, and targeted therapy in breast cancer. Nonetheless, full clinical translation of this technology will rely on optimizing their stability in vivo, standardizing selection protocols, and validating their performance in comparative clinical models that demonstrate tangible advantages over protein-based therapies.

2. The Use of Aptamers in Breast Cancer Diagnostics

Early detection of tumor biomarkers is one of the most effective strategies to reduce mortality associated with breast cancer. Aptamers, thanks to their high affinity, molecular specificity, and ease of chemical modification, have established themselves as versatile tools in the development of diagnostic platforms capable of identifying proteins, cells, and tumor vesicles with sensitivity comparable to that of monoclonal antibodies. Their thermal stability, low cost, and ability to be regenerated after multiple cycles of use make them ideal candidates for reusable and low-cost clinical devices. In the oncology field, aptamers have been designed to recognize clinically relevant biomarkers such as HER2, MUC1, EpCAM, PD-L1, and nucleolin, and have been integrated into biosensors, liquid biopsy techniques, and even high-resolution molecular imaging systems (Jo et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2012; Chinnappan et al., 2020; Su et al., 2025).

2.1. Aptamer Sensors in Solid Matrix

The ability of aptamers to recognize biologically relevant molecules with high affinity and specificity makes them central elements in a new generation of biosensors applied to breast cancer diagnostics. These DNA or RNA molecules are designed to bind to key targets such as the HER2 receptor (Hosseine et al., 2024), the AIB1 protein amplified in breast cancer (An et al., 2015), and the adhesion molecule EpCAM, used to capture and visualize circulating tumor cells (Song et al., 2013). In recent years, selection strategies based on genomic analysis and artificial intelligence have made it possible to identify aptamers against complex targets, optimizing their secondary structure and affinity using predictive models (Albanese et al., 2023). These advances have strengthened the sensitivity and specificity of aptameric biosensors, which can detect biomarker concentrations in the pico- or femtomolar range, surpassing the detection limits of conventional techniques like ELISA or immunohistochemistry.

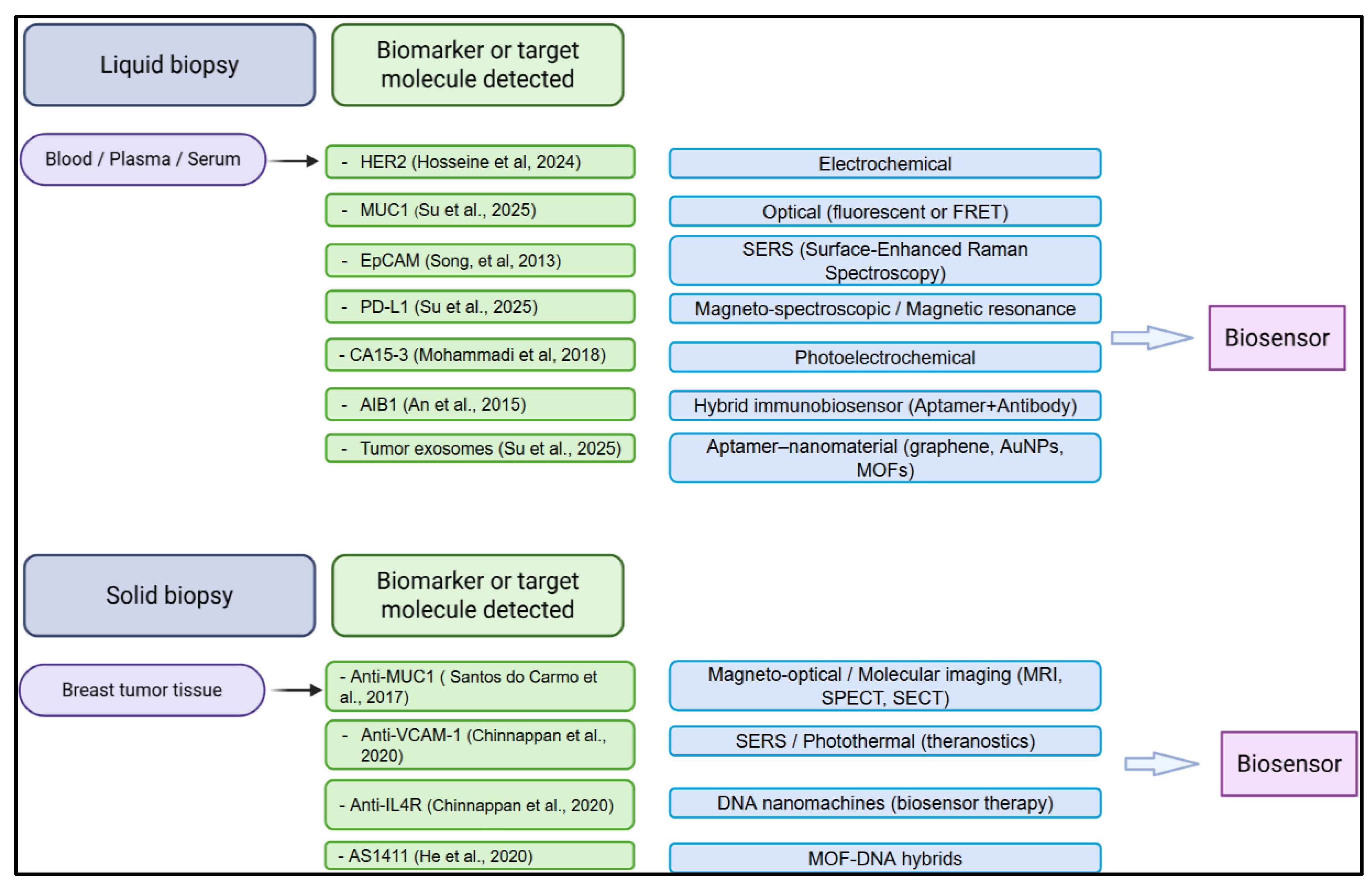

Figure 2.

Aptamer-based biosensing platforms for biomarker detection in liquid and solid biopsies of breast cancer. Overview of aptamer-guided biosensors classified according to the biological source and the detection principle. In liquid biopsies (blood, plasma, or serum), aptamers are used to identify circulating biomarkers such as HER2, MUC1, EpCAM, PD-L1, CA15-3, AIB1, and tumor-derived exosomes through electrochemical, optical, SERS, magneto-spectroscopic, or hybrid aptamer–nanomaterial systems. In solid biopsies (tumor tissue), aptamer-conjugated platforms enable highly specific imaging and theranostic approaches targeting molecules such as MUC1, VCAM-1, IL4R, and nucleolin (AS1411), employing magneto-optical, photothermal, DNA nanomachine, or MOF–DNA hybrid technologies. Collectively, these strategies exemplify the versatility of aptamers as molecular recognition elements in diagnostic and therapeutic biosensing for breast cancer.

Figure 2.

Aptamer-based biosensing platforms for biomarker detection in liquid and solid biopsies of breast cancer. Overview of aptamer-guided biosensors classified according to the biological source and the detection principle. In liquid biopsies (blood, plasma, or serum), aptamers are used to identify circulating biomarkers such as HER2, MUC1, EpCAM, PD-L1, CA15-3, AIB1, and tumor-derived exosomes through electrochemical, optical, SERS, magneto-spectroscopic, or hybrid aptamer–nanomaterial systems. In solid biopsies (tumor tissue), aptamer-conjugated platforms enable highly specific imaging and theranostic approaches targeting molecules such as MUC1, VCAM-1, IL4R, and nucleolin (AS1411), employing magneto-optical, photothermal, DNA nanomachine, or MOF–DNA hybrid technologies. Collectively, these strategies exemplify the versatility of aptamers as molecular recognition elements in diagnostic and therapeutic biosensing for breast cancer.

The incorporation of nanomaterials and noble metals has significantly enhanced the analytical performance of biosensors. The conjugation of aptamers with superparamagnetic nanoparticles, silver-gold hybrids, or graphene-based systems has made it possible to amplify signals and obtain high-resolution images through magnetic resonance imaging or surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) (Chinnappan et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2012). These devices combine precise molecular recognition with advanced optical and magnetic properties, enabling the simultaneous detection and quantification of multiple biomarkers in a single test. Hybrid biosensors with structures such as Fe₃O₄@Au–graphene demonstrate high conductivity, improved stability, and reduced interference from serum components, which increases reliability in complex biological samples (Zhou et al., 2021). This technological integration has given rise to theranostic platforms, capable not only of diagnosing but also of guiding or activating localized treatments under optical or magnetic stimuli.

Beyond passive detection, some advanced design systems have demonstrated the possibility of coupling molecular recognition with active immunological modulation. For example, the Aptamer–Biotin–Streptavidin–C1q complex can induce complement activation, paving the way for immunodiagnostic strategies with simultaneous therapeutic effects (Xu et al., 2022). However, progress toward clinical application requires addressing limitations related to in vivo stability, variability in biological matrices, and inter-laboratory reproducibility, all of which are essential factors for standardizing sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy compared to conventional immunological methods.

Taken together, aptamer-based biosensors represent a significant evolution in the molecular detection of breast cancer by integrating highly specific recognition, multifunctional response, and compatibility with emerging technologies. Their development marks a transition from analytical diagnostics toward intelligent systems capable of combining detection, monitoring, and therapeutic response in a single platform.

2.2. Aptasensor-Based Approaches for Liquid Biopsy and Early Detection of Breast Cancer

Liquid biopsies, which analyze tumor components in blood and other body fluids, have advanced significantly thanks to the use of aptamers, establishing themselves as a minimally invasive method for the diagnosis and monitoring of breast cancer. Due to their high affinity and specificity, aptamers are ideal tools for capturing circulating tumor cells (CTCs), exosomes, and serum biomarkers associated with metastatic progression. Strategies combining aptamers with magnetic beads or quantum dots enable the detection and quantification of CTCs in MCF-7 lines with high sensitivity and a reduction in false positives (Hua et al., 2013), while techniques like dual rolling circle amplification and multiplexed electrochemical biosensors further improve the detection limit (Sun et al., 2020; Shen, 2019). These platforms achieve levels comparable to conventional immunoassays, although clinical validation remains limited and outcomes depend on the aptamer's stability and serum composition.

Optical and electrochemical biosensors integrating aptamers with silver nanorods, graphene or Fe₃O₄ have demonstrated rapid and reproducible detection of tumor cells in blood, offering high conductivity and low interference (Mohammadi et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). Similarly, electrochemiluminescent and photoelectrochemical technologies identify SK-BR-3 and MCF-7 cells with great specificity, expanding the potential of molecular diagnostics in portable and microfluidic systems (Luo et al., 2020).

For extracellular vesicles, magnetic nanocomposites functionalized with aptamers have been developed to isolate PD-L1⁺ exosomes, analyzed via surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), enabling precise discrimination between tumor samples and controls (Su et al., 2025). Likewise, an RNA aptamer targeting breast cancer exosomes has demonstrated high-resolution optical and electrochemical applications (Esposito, 2021). In parallel, aptamer-based immunosensors combined with metallic or carbon nanoparticles simultaneously quantify CA15-3, HER2, and MUC1, showing significant correlation with clinical levels (Su et al., 2025; Hosseine et al., 2024). Specific sensors for MUC1 coupled to AuNPs or graphene-Fe₃O₄ hybrid materials improve stability and sensitivity (Mohammadi et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018).

Altogether, these approaches establish aptamers as pillars of next-generation liquid biopsy, capable of integrating capture, detection, and molecular analysis into a single system. Nonetheless, their clinical translation requires standardizing protocols, evaluating biological interferences and confirming sensitivity and specificity in longitudinal studies—necessary conditions for establishing their routine use in early breast cancer diagnosis.

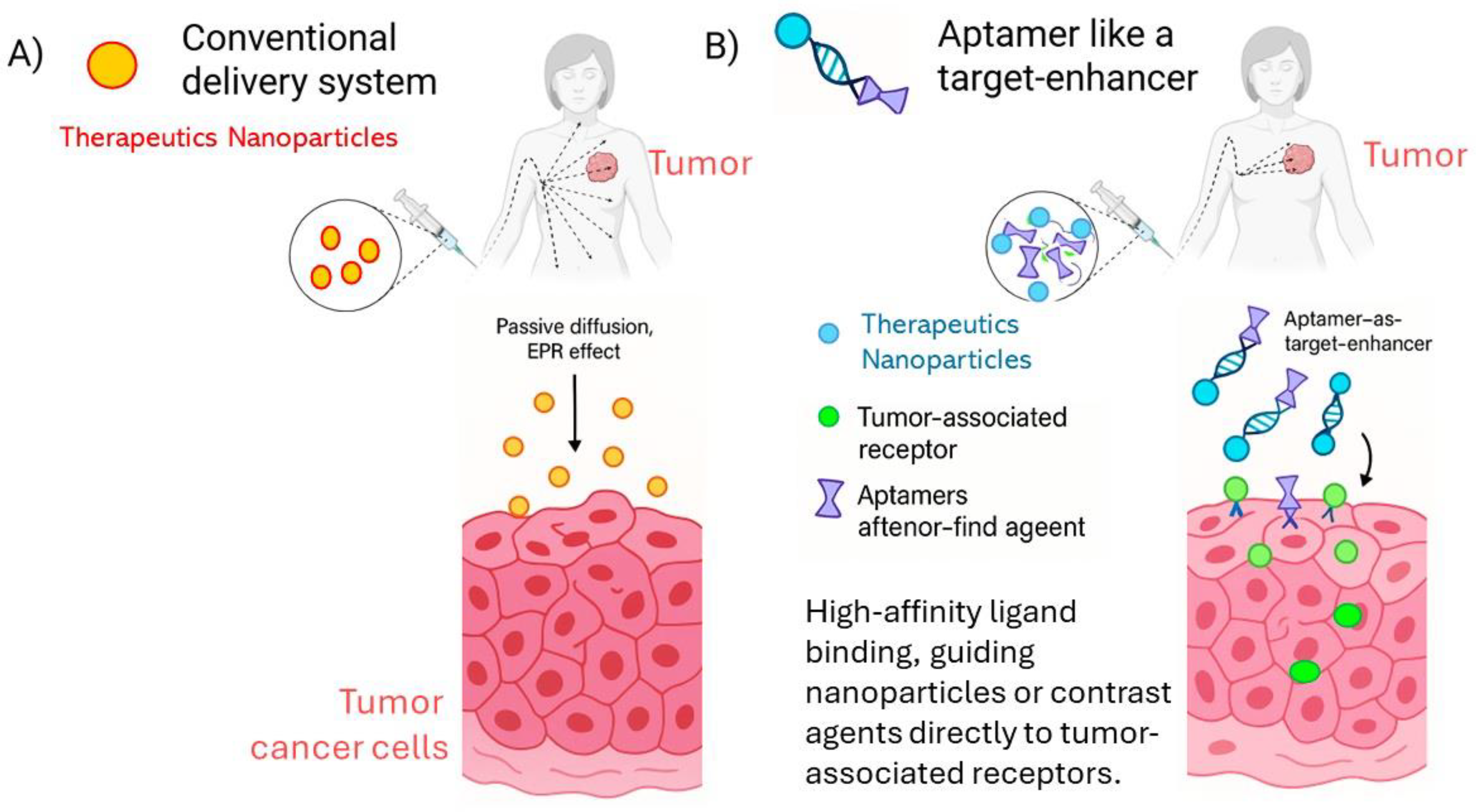

2.3. Aptamer Like a Target-Enhancer Imaging in Tumor

In molecular imaging and targeted drug delivery, the addition of aptamers to conventional nanosystems transforms their performance from passive accumulation to active, ligand-guided targeting. While traditional delivery systems rely mainly on the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, aptamer-functionalized constructs actively recognize tumor-associated receptors, guiding imaging probes or therapeutic cargos directly to malignant cells. This molecular precision enhances contrast resolution, reduces off-target distribution, and enables the development of theranostic platforms capable of simultaneous diagnosis and therapy. As illustrated in Figure X, aptamers act as targeting enhancers, improving the specificity and efficiency of nanoparticle-based imaging and treatment strategies in breast cancer compared to conventional non-targeted systems.

Figure 3.

Comparative schematic of targeting strategies in molecular imaging and therapy.(A) Conventional delivery systems rely mainly on passive diffusion and the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, resulting in non-specific accumulation of imaging or therapeutic agents within tumor tissue. (B) Aptamer-functionalized systems provide active molecular recognition through high-affinity ligand binding, guiding nanoparticles or contrast agents directly to tumor-associated receptors. This “aptamer-as-a-target-enhancer” strategy improves localization, imaging contrast, and therapeutic precision, exemplifying the transition from passive to actively targeted nanomedicine in breast cancer. (Part of the image is obtained in BIORENDER).

Figure 3.

Comparative schematic of targeting strategies in molecular imaging and therapy.(A) Conventional delivery systems rely mainly on passive diffusion and the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, resulting in non-specific accumulation of imaging or therapeutic agents within tumor tissue. (B) Aptamer-functionalized systems provide active molecular recognition through high-affinity ligand binding, guiding nanoparticles or contrast agents directly to tumor-associated receptors. This “aptamer-as-a-target-enhancer” strategy improves localization, imaging contrast, and therapeutic precision, exemplifying the transition from passive to actively targeted nanomedicine in breast cancer. (Part of the image is obtained in BIORENDER).

In the field of molecular imaging applied to breast cancer, aptamers are used as highly selective ligands capable of directing contrast agents toward tumor cells, increasing spatial resolution and diagnostic specificity. The conjugation of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with anti-VCAM-1 and anti-IL4R aptamers has enabled high-definition imaging via magnetic resonance, in addition to enabling a theranostic approach that combines diagnostics and targeted treatment (Chinnappan et al., 2020). Complementarily, perfluoropolyether nanoparticles enriched with fluorine-19 have been designed to generate dual images through magnetic resonance and optical imaging, while anti-MUC1 aptamers have demonstrated efficacy in single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in triple-negative breast cancer models, expanding the clinical applicability of these hybrid platforms (Zhang et al., 2018; Santos do Carmo et al., 2017). These strategies highlight the ability of aptamers to selectively direct molecular contrast agents and improve tumor delineation without the need for conventional radioactive markers.

In the area of photoinduced imaging and photothermal therapy, aptamers conjugated with bimetallic silver and gold structures have enabled specific detection via surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) and at the same time facilitated localized destruction of tumor cells under infrared irradiation (Wu et al., 2012). Similarly, nanocomplexes functionalized with the AS1411 aptamer have been evaluated as dual-imaging and photothermal treatment platforms, demonstrating significant reduction in tumor growth and high cellular specificity (He et al., 2020). These systems represent an example of effective theranostics, in which the same molecule acts as sensor, guide, and therapeutic agent, minimizing off-target toxicity.

The most advanced approaches incorporate DNA nanomachines conjugated with gold, activated by endogenous mRNA, allowing in situ imaging along with a highly precise synergistic therapeutic response (Yu, 2021). Likewise, aptamers are being explored for photoelectrochemical detection of cancer cells and for imaging via sequential emission computed tomography (SECT) in animal models of aggressive breast cancer (Luo, 2020; Santos do Carmo et al., 2017). Although these systems show significant progress towards integrating diagnosis and therapy in a single vector, their clinical translation still requires validation of parameters such as biodistribution, in vivo stability, and long-term biocompatibility.

Overall, the incorporation of aptamers into molecular imaging technologies represents a decisive advance toward precision medicine, allowing the specific localization of lesions, non-invasive monitoring of therapeutic response, and the possibility of combining diagnosis and treatment within a single construct. However, most developments remain in the preclinical phase, and clinical implementation will depend on optimizing the pharmacokinetics of the conjugates and establishing standardized protocols that ensure sensitivity and safety equal to or surpassing those of conventional imaging platforms.

3. Aptamers Used in the Prognosis of Breast Cancer

Accurate prediction of breast cancer progression is fundamental for guiding therapeutic decisions and optimizing clinical management. In this context, aptamers have emerged as powerful prognostic tools capable of detecting biomarkers associated with tumor aggressiveness, recurrence risk, and therapeutic resistance. By specifically recognizing molecular targets implicated in oncogenic signaling, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and metastatic dissemination, aptamers provide both qualitative and quantitative information that supports patient stratification and personalized treatment planning. Their ability to discriminate subtle molecular variations in functional proteins, cell surface receptors, or extracellular vesicle cargos positions them as promising analytical and translational instruments for improving prognostic precision in breast cancer management

3.1. Biomarkers for Quantifiable Prognosis

A prominent example is the CA15-3 antigen, a classic serum marker whose ultrasensitive quantification using an aptamer-based FRET immunosensor has enabled dynamic monitoring of tumor burden and therapeutic response (Mohammadi et al., 2018). Similarly, electrochemical biosensors targeting HER2 identify SK-BR-3 cells with great precision (Hosseine et al., 2024).

Beyond static detection, colocalization-activated DNA assemblies allow visualization of HER2 dimerization, a phenomenon that reflects receptor activation and correlates with an unfavorable prognosis (Yu et al., 2021). Additionally, photo-crosslinkable aptamers against ERBB3 detect its association states, which are implicated in therapeutic resistance (Kim et al., 2020). These approaches provide a superior level of molecular and temporal resolution compared to immunohistochemistry (IHC) or qPCR, which require fixed tissue and do not report on the functional activity of receptors, thus offering a more dynamic readout of tumor biology.

These advances show how aptamers make it possible not only to measure the presence of biomarkers, but also to assess their functional activity, providing a comprehensive diagnostic tool that can guide risk stratification and inform treatment in breast cancer patients.

3.2. Aggressive Subpopulations and Cancer Stem Cells

A major breakthrough is the ability of aptamers to identify aggressive subpopulations and cancer stem cells (CSCs), which are responsible for recurrence and chemoresistance. The cell-SELEX technology has enabled the generation of specific aptamers against CD133 and CD49c, which are used to detect and isolate CSCs in breast cancer (Lu et al., 2015; Yin et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2022). In triple-negative breast cancer models, nanoparticles guided by anti-CD133 aptamers have been used to deliver therapeutic anti-miRNAs, reducing proliferation and invasiveness, thereby validating CD133 as a prognostic marker and functional therapeutic target (Yin et al., 2019). Similarly, aptamers against CD49c can identify highly invasive phenotypes associated with lower survival rates (Huang et al., 2022). These discoveries integrate the detection and modulation of high-risk subpopulations, going beyond the descriptive approach of conventional proteomics, though their clinical validation still requires direct comparisons with cytometric and histological assays in large cohorts.

The molecular detection and characterization of these aggressive subpopulations with aptamers enables more precise and personalized prognostic stratification. This advanced approach contributes to improving clinical prognosis, as it identifies patients at greater risk of progression and paves the way for targeted therapies that effectively attack cancer stem cells—crucial for preventing treatment resistance and tumor recurrence.

3.3. Multiligand Signatures and Prediction of Clinical Outcomes

Beyond individual biomarkers, aptamers facilitate the creation of multiligand molecular signatures with high prognostic value. The poly-ligand profiling technique uses aptamer libraries to assess multiple interactions and distinguish patients treated with trastuzumab according to their clinical course (Domenyuk et al., 2018). In parallel, mechanistic studies have identified nucleolin (NCL) as a key modulator of tumor aggressiveness. Targeting NCL with aptamers regulates oncogenic microRNAs involved in cell proliferation and migration, showing that blocking NCL serves not only for diagnosis but also modulates functional pathways related to prognosis (Pichiorri et al., 2013). Similarly, aptamers against the kinases MNK1b and VRK1 suppress protein translation and tumor proliferation, proposing these enzymes as indicators of poor prognosis and potential therapeutic targets (He et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2020). These findings show how aptamers can causally determine the function of their targets, unifying detection and functional validation within the same experiment.

3.4. Oncogenes and Kinases with Prognostic Relevance

Finally, the role of the tumor microenvironment (TME) as a prognostic determinant has also been explored using aptamers. Quantification of PD-L1⁺ exosomes via aptamer-functionalized SERS platforms has enabled correlation of immunosuppressive burden with clinical progression (Su et al., 2025). Likewise, aptamers targeting PDGFRβ, which is overexpressed in triple-negative tumors, reduce the migration of mesenchymal cells and the formation of the metastatic niche, modulating the tumor environment and improving survival (Wang et al., 2021). Complementarily, aptamers that block the recruitment of CD4⁺ T lymphocytes reverse immunosuppression and enhance the antitumor response, correlating with better prognosis (Li et al., 2023). In this sense, the connection between diagnosis and prognosis is clear: biomarkers such as HER2 or PDGFRβ, initially detected for diagnostic purposes, acquire prognostic significance when their activation or modulation by aptamers directly alters metastatic or immunological pathways.

On the other hand, the PDGFRβ receptor, which is highly elevated in triple-negative tumors, has been identified as a relevant target for aptamers, whose inhibition has been shown to reduce lung metastasis and alter tumor-stroma interaction—factors related to increased patient survival (Wang et al., 2021). Furthermore, an aptamer with affinity for the β subunit of ATP synthase located on the plasma membrane has been reported, proposed as an early marker of aggressive tumor phenotype with potential for therapeutic applications (Yu et al., 2021).

These findings underscore the ability of aptamers not only to detect and characterize proteins involved in oncogenesis and tumor progression but also to modulate their activity, opening new avenues for more precise prognosis and the development of personalized therapies in breast cancer.

3.5. Tumor Microenvironment and Immunosuppression

Finally, the role of the tumor microenvironment (TME) as a prognostic determinant has also been explored using aptamers. The quantification of PD-L1⁺ exosomes through SERS platforms functionalized with aptamers has enabled the correlation of immunosuppressive load with clinical progression (Su et al., 2025). Similarly, aptamers against PDGFRβ, which is overexpressed in triple-negative tumors, reduce the migration of mesenchymal cells and the formation of the metastatic niche, thereby modulating the tumor environment and improving survival (Wang et al., 2021). Complementarily, aptamers that block the recruitment of CD4⁺ T lymphocytes reverse immunosuppression and enhance the antitumor response, correlating with a better prognosis (Li et al., 2023). In this regard, the connection between diagnosis and prognosis is evident: biomarkers such as HER2 or PDGFRβ, initially detected for diagnostic purposes, acquire prognostic significance when their activation or modulation with aptamers directly alters metastatic or immunological pathways.

Taken together, current evidence shows that aptamers provide a mechanistic perspective on breast cancer prognosis by integrating molecular detection, biological function, and therapeutic response. While many results remain at the preclinical stage, their ability to combine specificity, sensitivity, and functional analysis positions them as promising tools for prognostic stratification and precision medicine, complementing and even surpassing the potential of conventional tumor assessment methods.

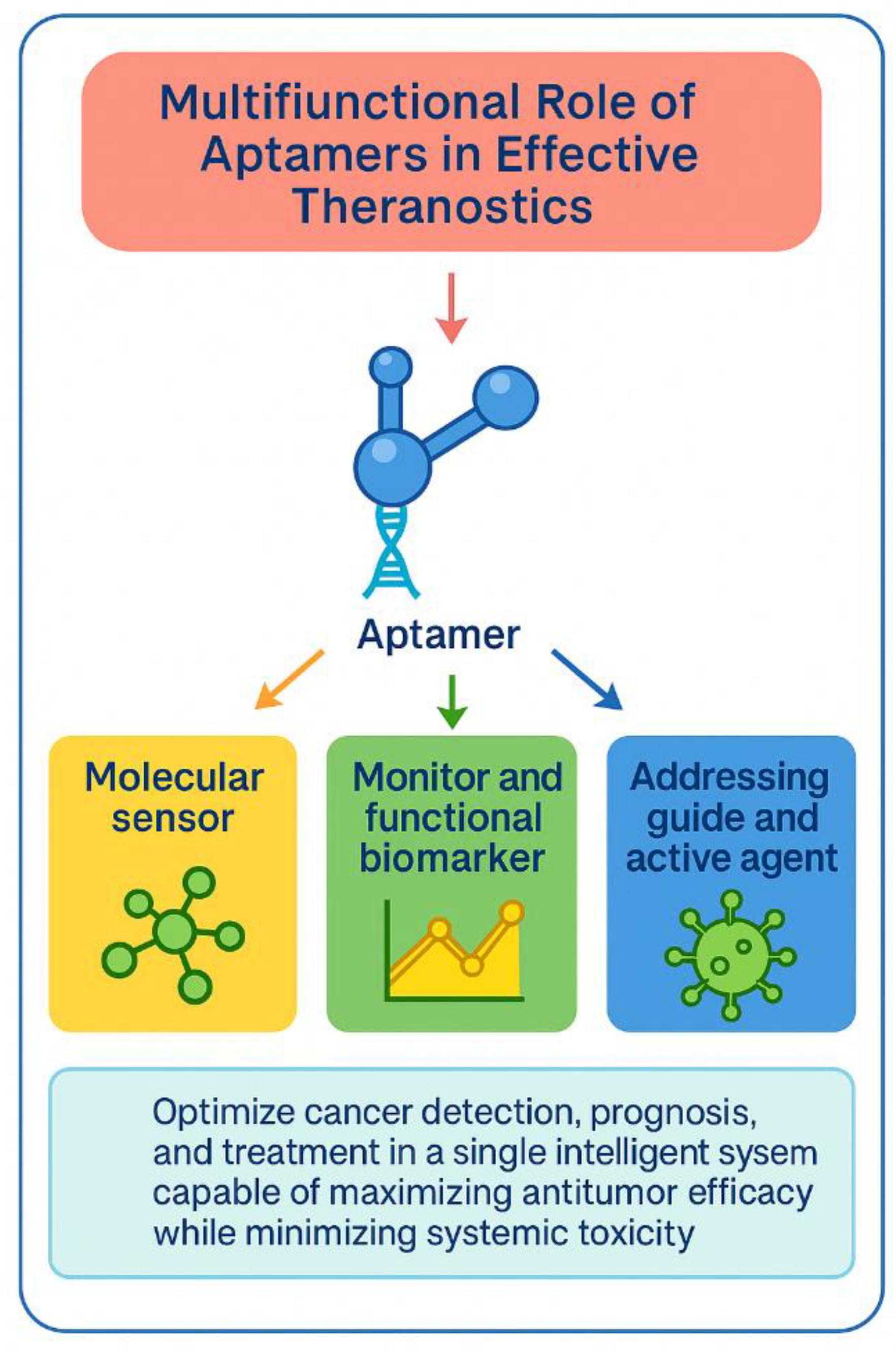

4. Aptamers Used in Breast Cancer Therapy

In breast cancer therapy, aptamers have established themselves as highly precise therapeutic tools owing to their ability to act as antagonists of target molecules or as vehicles for ligand-directed targeting—that is, the selective delivery of therapeutic agents to tumor cells. This principle is based on the affinity and specificity of aptamers for proteins or receptors overexpressed in malignant cells, guiding drugs, nucleic acids, or nano-cargos directly to the tumor site and reducing systemic exposure (Zhou et al., 2021). Through SELEX technologies, aptamers have been developed against relevant targets such as HER2, EpCAM, NCL, and receptors associated with tumor stem cells, allowing for the blockage of oncogenic signaling pathways or serving as delivery vectors for chemotherapeutics, interfering RNAs, nanoparticles, or photosensitizers. These strategies combine direct molecular inhibition with modulation of the tumor and immune microenvironment, advancing towards more precise, personalized therapies with lower toxicity.

# destacar Raros

4.1. Aptamers as Therapeutic Agents and Specific Target Modulators

Aptamers can act as direct antagonists of proteins critical for tumor survival and progression. The AS1411 aptamer, directed against nucleolin (NCL), inhibits cell proliferation and enhances radiosensitivity when combined with gold nanoparticles, being one of the first aptamers evaluated clinically (Mehrnia et al., 2021; Reyes-Reyes et al., 2010). Likewise, Axl-148b blocks tumor progression in breast cancer and melanoma (Quirico et al., 2020), while an RNA aptamer against osteopontin (OPN) suppresses growth and metastasis in MDA-MB-231 cells (Mi et al., 2009). At the cutting edge, Aptamer–PROTAC conjugates facilitate the selective degradation of oncogenic proteins via targeted ubiquitination (He et al., 2021), and the Q10 aptamer, obtained by Exo-SELEX from metastatic exosomes, reduces angiogenesis and pulmonary metastasis without systemic toxicity (Wang et al., 2025). Aptamers targeting VRK1 and PAI-1 inhibit proliferation and migration (Kim et al., 2020; Mi et al., 2009), and apMNKQ2 against kinase MNK1b blocks protein translation linked to invasive phenotypes (He et al., 2021). Blocking NCL also modulates oncogenic microRNAs, reducing tumor aggressiveness (Pichiorri et al., 2013). These results, although mostly preclinical, consolidate the value of aptamers as direct agents with high specificity, low immunogenicity, and excellent chemical reproducibility. However, their in vivo half-life is usually short (minutes to a few hours), and rapid renal clearance (<30 kDa) limits their therapeutic efficacy, necessitating PEGylation or nanoparticle formulations to prolong circulation and biodistribution.

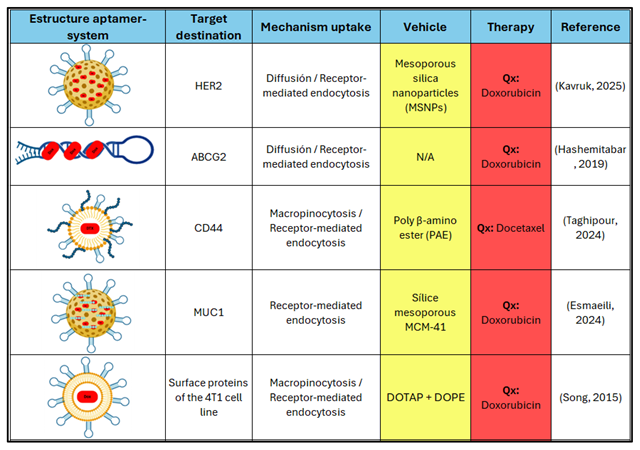

4.2. Aptamers in Chemotherapeutic Drug Delivery Systems

Aptamers are widely used in targeted delivery systems for chemotherapeutic agents, increasing efficacy and reducing systemic toxicity. They have been coupled to liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, micelles, and functionalized mesoporous silica structures targeting MUC1, HER2, EGFR, or NCL, to transport drugs such as doxorubicin, docetaxel, paclitaxel, or cisplatin (Song et al., 2015; Esmaeili et al., 2024; Taghipour et al., 2024). Notable examples include dual polymeric micelles (SRL2–TA1) with docetaxel, which induce apoptosis and an antimetastatic effect (Taghipour et al., 2024), and anti-MUC1–DOX mesoporous nanoparticles with controlled release in MCF7 cells (Alibolandi et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2012). Combinations with paclitaxel, epirubicin, gemcitabine, or triptolide have produced multifunctional systems that overcome drug resistance, such as magnetic nanoparticles loaded with paclitaxel or selenium with epirubicin and the NAS-24 aptamer (Camorani et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2018). Anti-EGFR polymeric nanocarriers enhance tumor accumulation of cisplatin (Esmaeili et al., 2024). Finally, self-assembled DNA structures like nanotrenes and nanobarrels conjugated with AS1411 enable multiple payloads and synergistic intracellular release (Xu et al., 2019). Collectively, these systems exhibit a clear relationship between molecular design and therapeutic benefit, though clinical parameters such as biodistribution, maximum tolerated dose, and tumor retention still need to be evaluated (TRL 4–5).

Table 2.

Classification of aptamer system used in therapy.

Table 2.

Classification of aptamer system used in therapy.

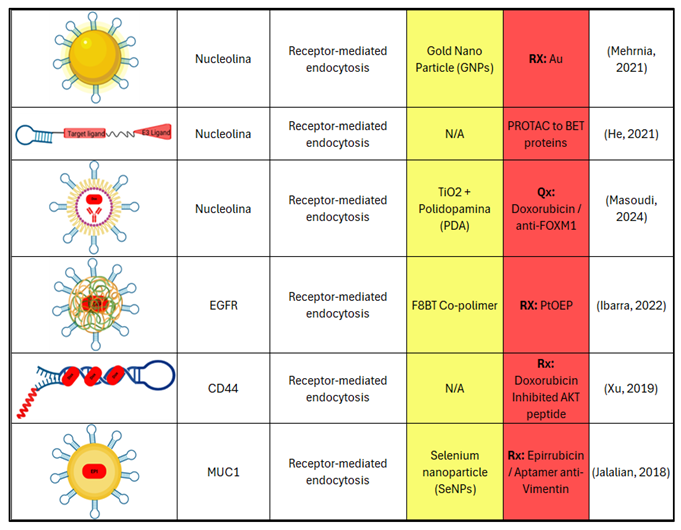

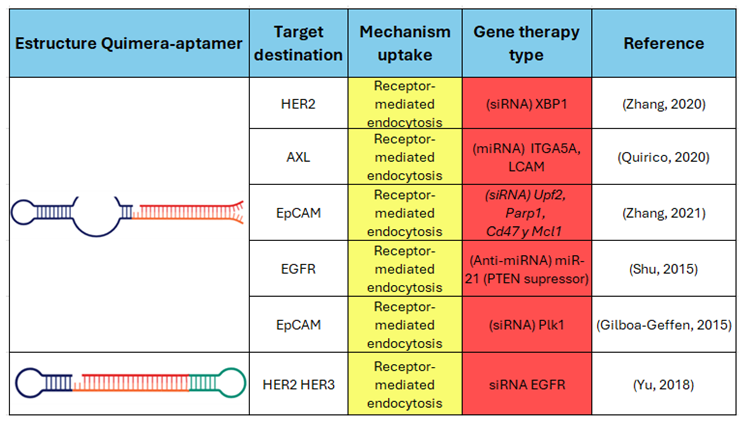

4.3. Combined Therapies with Chemotherapy, Radiotherapy, and Immunotherapy

Combined therapies integrating aptamers with traditional modalities seek therapeutic synergies and toxicity reduction. In chemotherapy, aptamer–siRNA conjugates allow simultaneous co-delivery of agents like doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and cisplatin, highlighting chimeras targeting EGFR/HER2/HER3 or EpCAM–siRNA, which reduce survivin expression and tumor stem cells (Yu et al., 2018). Cationic liposomes functionalized with aptamers that co-deliver paclitaxel and anti-PLK1 siRNA synergistically inhibit tumor growth in vivo (Li et al., 2020). In radiotherapy, the conjugation of AS1411 with gold nanoparticles increases the nuclear deposition of radiation, intensifying tumor damage (Mehrnia et al., 2021), while anti-PD-L1 hafnium oxide nanoparticles combine radiosensitization and near-infrared imaging (Wei et al., 2023). In immunotherapy, anti-PD-L1 aptamers produce dual effects of immunosuppressive blockade and cytotoxicity when combined with chemotherapy; others, coupled to NK cells, increase selective cytotoxicity in triple-negative breast cancer (Camorani et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022). Aptamer–PROTAC conjugates expand the selective degradation of immunosuppressive proteins (He et al., 2021). Clinically, only a few aptamers (pegaptanib, NOX-A12) have reached early clinical stages in other tumors, highlighting the need for comparative trials to validate efficacy and safety in breast cancer (TRL 5–6).

4.4. Other Therapeutic Modalities

Aptamers are also applied in physical therapies such as photothermal and photodynamic therapy, directing photoactive agents with high specificity and minimal toxicity (Yang et al., 2015; Ibarra et al., 2022).

Table 3.

Quimera Aptamer system to gene therapy target-ligand.

Table 3.

Quimera Aptamer system to gene therapy target-ligand.

Biomimetic platforms based on DNA and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) conjugated with aptamers respond to physiological stimuli such as pH, ATP, or microRNAs, releasing their cargo in the tumor microenvironment (Wang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022; Taghipour et al., 2024). These include pH and miRNA-sensitive DNA-MOF systems, dual ATP/pH nanoparticles, and targeted micelles that release doxorubicin at metastatic sites. Moreover, self-assembled structures like aptamer–DOX nanotrenes achieve efficient and selective drug delivery in tumor stem cells (Xu et al., 2019). These platforms attain high levels of spatial and temporal control (TRL 4-5), though challenges in tissue penetration and thermal dissipation remain.

Overall, aptamer-based therapies integrate molecular specificity, chemical modularity, and compatibility with nanotechnology, positioning them as cornerstones of precision medicine. However, the lack of clinical studies, pharmacokinetic limitations, and variability of in vivo response require caution before their widespread therapeutic adoption. Their future will depend on optimizing stability, biodistribution, and comparative validation against antibodies and existing biological platforms.

Figure 4.

Multifunctional role of aptamers in effective theranostics. Schematic representation of aptamers as central components of intelligent theranostic systems. Acting simultaneously as molecular sensors, monitoring biomarkers, and active targeting agents, aptamers bridge diagnostic and therapeutic functions within a single construct. This multifunctionality enables real-time monitoring, precise tumor localization, and controlled therapeutic delivery, optimizing cancer detection, prognosis, and treatment while minimizing systemic toxicity and off-target effects.

Figure 4.

Multifunctional role of aptamers in effective theranostics. Schematic representation of aptamers as central components of intelligent theranostic systems. Acting simultaneously as molecular sensors, monitoring biomarkers, and active targeting agents, aptamers bridge diagnostic and therapeutic functions within a single construct. This multifunctionality enables real-time monitoring, precise tumor localization, and controlled therapeutic delivery, optimizing cancer detection, prognosis, and treatment while minimizing systemic toxicity and off-target effects.

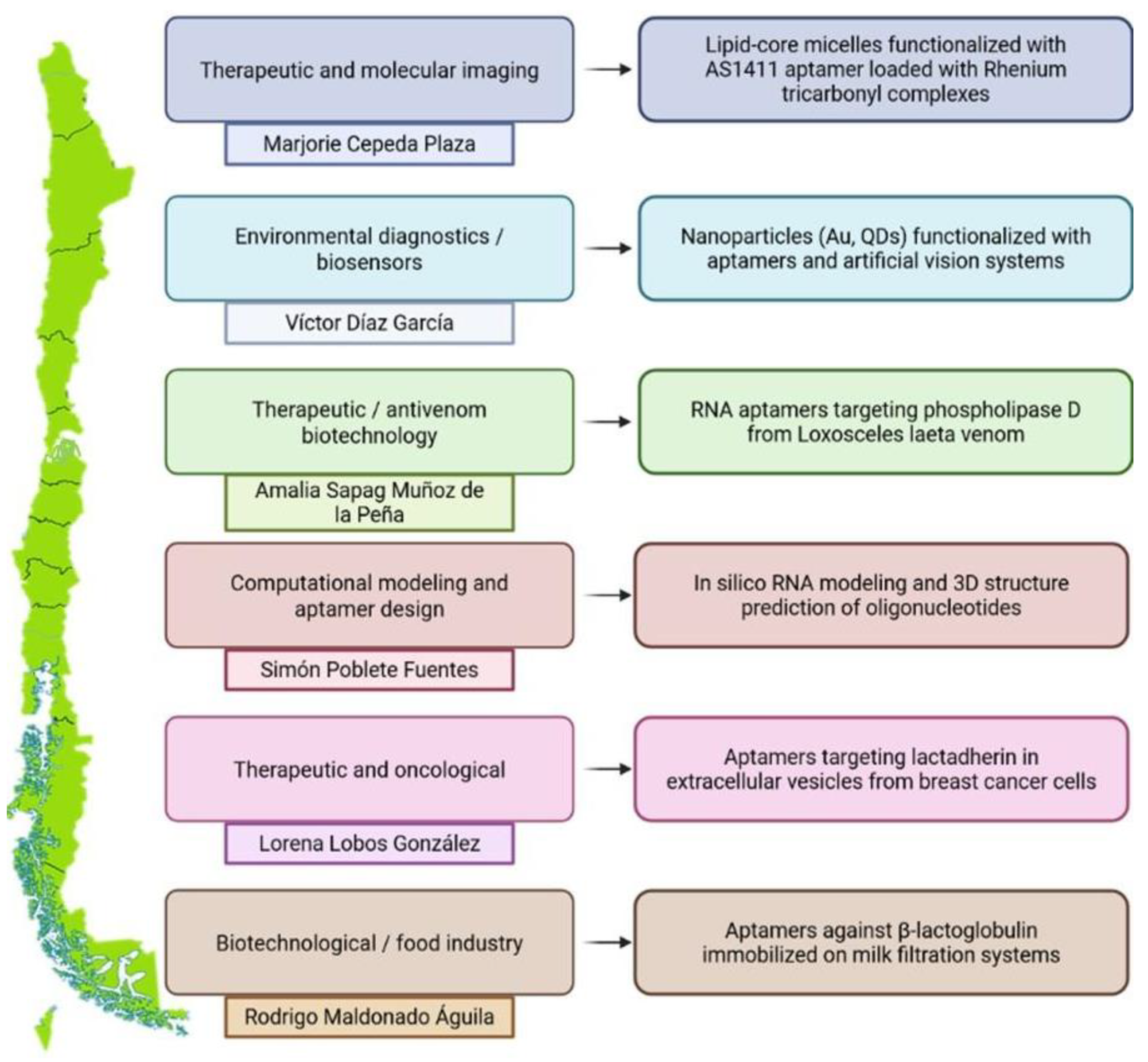

5. Perspectives and Challenges in Latin America

Research on aptamers has grown steadily in Latin America, with Chile, Argentina, and Mexico serving as key centers for development in the diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy of breast cancer and other diseases. In Chile, the First “Aptamers in Chile 2024” Meeting (organized by Dr. Amalia Sapag, University of Chile) showcased a well-established scientific community. Notable contributions include the work of Dr. Marjorie Cepeda (UNAB/U. de Chile) on lipid micelles with the AS1411 aptamer for imaging and targeted therapy; Dr. Víctor Díaz (USS) on biosensors with nanoparticles; Dr. Simón Poblete (Ciencia & Vida Foundation) on RNA structural modeling; and the “Apta-TumorStop” project (Dr. Lorena Lobos González, U. de Chile/ACCDiS), which managed to reduce tumorigenesis by blocking lactadherin in extracellular vesicles. Additionally, Dr. Rodrigo Maldonado (USS/CECs) demonstrated food applications through aptamers designed to eliminate β-lactoglobulin, reflecting the technological versatility of the Chilean ecosystem.

In Argentina, collaboration between CONICET and national universities has spurred the development of aptasensors and nano-aptamer platforms. Dr. Laura Raiger’s group (CONICET-UBA) has designed electrochemical and optical biosensors for contaminants and clinical biomarkers, while the NanoBioSensors-INQUIMAE team led by Dr. Michael López works on the conjugation of aptamers with nanomaterials such as graphene, gold, and zinc oxide, applicable to molecular diagnosis and personalized medicine.

Mexico has strengthened its work on structural design and nanobiotechnology applied to aptamers. CICESE has modeled the interaction of the anti-MUC1 aptamer with its epitope; CINVESTAV leads SELEX selection programs; UNAM develops G-quadruplex aptamers with anti-angiogenic potential and metal conjugates for molecular detection; and UANL works on nanosystems targeting HER2, aimed at precision medicine. Despite these advances, the region faces translational gaps: intermittent funding, uneven infrastructure, lack of clinical trials, and regulatory frameworks adapted to oligonucleotide-based therapies. There is also an ongoing need to standardize analytical parameters - sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility - to compare prototypes with international platforms.

Taken together, the progress in Chile, Argentina, and Mexico demonstrates that the region has the scientific capacity to join precision medicine based on aptamers. The immediate challenge is to transform experimental advances into robust clinical evidence through multicenter consortia, shared biobanks, and joint validation and regulatory strategies, propelling Latin America toward an active role in translational biotechnology.

6. Conclusion

Aptamers have emerged as key tools in contemporary biomedicine, especially in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Their nature as DNA or RNA oligonucleotides gives them unique advantages over monoclonal antibodies, including low synthesis cost, high specificity, chemical reproducibility, and ease of structural modification. These properties, along with advancements in SELEX technologies and the ability to incorporate stabilizing chemical modifications, have propelled their development as versatile molecular platforms capable of integration into biosensors, imaging systems, targeted therapies, and theranostic nanodevices.

In diagnosis and prognosis, aptamers have enabled the detection of relevant biomarkers such as HER2, MUC1, EpCAM, PD-L1, and nucleolin through biosensors, liquid biopsies, and high-resolution optical technologies. These strategies make early disease identification and molecular stratification of patients possible, improving clinical precision and the monitoring of therapeutic response. In therapy, aptamers act both as direct inhibitors of oncogenic pathways and as components in controlled delivery systems for drugs and nucleic acids. Conjugates such as aptamer–drug, aptamer–siRNA, and nano-aptamer structures have demonstrated preclinical efficacy in aggressive subtypes like triple-negative breast cancer, validating their potential in personalized medicine.

Despite these advances, challenges remain that limit their clinical translation: short half-life, rapid renal clearance, potential immunogenicity, and lack of multicenter validation. In this context, Latin America - with Chile, Argentina, and Mexico as leaders - has driven significant growth in translational research, biosensors, and structural design of aptamers, although regulatory and infrastructure gaps persist. The future of the field will depend on integrating artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and systems pharmacology to optimize in vivo stability and efficacy. Overcoming these challenges will enable aptamers to be established as clinically approved agents and leading figures in 21st-century precision medicine.

Figure 5.

Overview of Chilean scientific contributions to aptamer-based research. Representation of leading research lines in Chile focused on aptamer technology and its multidisciplinary applications. The figure highlights key investigators and thematic areas that exemplify the regional development of aptamer science. Marjorie Cepeda Plaza explores therapeutic micellar systems functionalized with the AS1411 aptamer for molecular imaging and targeted delivery. Víctor Díaz García advances environmental diagnostics through nanoparticle-based biosensors. Amalia Sapag Muñoz de la Peña pioneers RNA aptamers with antivenom and biomedical potential, while Simón Poblete Fuentes applies computational modeling and in silico structure prediction to rational aptamer design. Lorena Lobos González leads oncological research targeting lactadherin in extracellular vesicles from breast cancer cells, and Rodrigo Maldonado Águila develops aptamer-functionalized systems for biotechnological and food industry applications. Together, these initiatives demonstrate Chile’s growing leadership in translational biotechnology, bridging molecular design, nanotechnology, and clinical innovation to position Latin America as a relevant contributor to the global aptamer field.

Figure 5.

Overview of Chilean scientific contributions to aptamer-based research. Representation of leading research lines in Chile focused on aptamer technology and its multidisciplinary applications. The figure highlights key investigators and thematic areas that exemplify the regional development of aptamer science. Marjorie Cepeda Plaza explores therapeutic micellar systems functionalized with the AS1411 aptamer for molecular imaging and targeted delivery. Víctor Díaz García advances environmental diagnostics through nanoparticle-based biosensors. Amalia Sapag Muñoz de la Peña pioneers RNA aptamers with antivenom and biomedical potential, while Simón Poblete Fuentes applies computational modeling and in silico structure prediction to rational aptamer design. Lorena Lobos González leads oncological research targeting lactadherin in extracellular vesicles from breast cancer cells, and Rodrigo Maldonado Águila develops aptamer-functionalized systems for biotechnological and food industry applications. Together, these initiatives demonstrate Chile’s growing leadership in translational biotechnology, bridging molecular design, nanotechnology, and clinical innovation to position Latin America as a relevant contributor to the global aptamer field.

Abbreviations

| Breast cancer subtypes & clinical markers |

| TNBC |

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

| HER2 |

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| |

|

| |

|

| ER |

Estrogen Receptor |

| PR |

Progesterone Receptor |

| Liquid biopsy, vesicles & imaging |

| CTC(s) |

Circulating Tumor Cell(s) |

| EV(s) |

Extracellular Vesicle(s) |

| SERS |

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy |

| SECT |

Sequential Emission Computed Tomography |

| SPECT |

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| Tumor biomarkers & receptors |

| MUC1 |

Mucin 1 |

| EpCAM |

Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| PD-L1 |

Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PDGFRβ |

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor Beta |

| AIB1 |

Amplified in Breast Cancer 1 |

| NCL |

Nucleolin |

| OPN |

Osteopontin |

| VRK1 |

Vaccinia-Related Kinase 1 |

| MNK1b |

MAP Kinase-Interacting Kinase 1b |

| Aptamer platforms & molecular tools |

| SELEX |

Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment |

| Cell-SELEX |

Cell-based SELEX |

| Exo-SELEX |

Exosome-guided SELEX |

| AS1411 |

Nucleolin-Binding Aptamer |

| Q10 |

Anti-metastatic Exo-SELEX Aptamer |

| Axl-148b |

Anti-Axl Aptamer |

Therapeutic systems & nanotechnology

|

| siRNA |

Small Interfering RNA |

| PROTAC |

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimera |

| APC |

Aptamer–PROTAC Conjugate |

| DOX |

Doxorubicin |

| PTX |

Paclitaxel |

| DOC |

Docetaxel |

| PEG |

Polyethylene Glycol |

| MOF |

Metal–Organic Framework |

| ATP |

Adenosine Triphosphate |

| NIR |

Near-Infrared |

| Cell lines |

| MCF-7 |

Human Breast Adenocarcinoma Cells |

| SK-BR-3 |

HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Cells |

| MDA-MB-231 |

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells |

| Nanomaterials |

| Fe₃O₄ |

Magnetite Nanoparticles |

| AuNPs |

Gold Nanoparticles |

| Ag–Au |

Silver–Gold Nanostructures |

| QDs |

Quantum Dots |

| DNA-Au |

DNA–Gold Nanomachine |

| Others |

| miRNA |

MicroRNA |

| TME |

Tumor Microenvironment |

| EPR |

Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO); World Health Organization. Breast Cancer: Key Facts – Updated 2024; Geneva, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, H.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021, 71(3), 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, G.; et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: Challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2016, 13(11), 674–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, A. D.; Szostak, J. W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346(6287), 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J. Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: Current potential and challenges. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2017, 16(3), 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; et al. Recent advances in aptamer-based targeted drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10, 972933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.; et al. Nucleic acid aptamers: Clinical applications and promising new horizons. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2011, 18(27), 4206–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Ban, C. Aptamer-nanoparticle complexes as powerful diagnostic and therapeutic tools. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2016, 48(5), e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Novel HER2 aptamer selectively delivers cytotoxic drug to HER2-positive breast cancer cells in vitro. Journal of Translational Medicine 2012, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; et al. Polydopamine-based surface modification of novel nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for in vivo breast cancer targeting and enhanced therapeutic effects. Theranostics 2016, 6(4), 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; et al. EpCAM Aptamer-mediated survivin silencing sensitized cancer stem cells to doxorubicin in a breast cancer model. Theranostics 2015, 5(12), 1456–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, E. M.; et al. Aptamers: Promising tools for the detection of circulating tumor cells. Nucleic Acid Therapeutics 2016, 26(6), 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhumashev, D.; et al. Quantum dot-based screening identifies F3 peptide and reveals cell surface nucleolin as a therapeutic target for rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers 2022, 14(20), 5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; et al. Targeted immunotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer by aptamer-engineered NK cells. Biomaterials 2022, 280, 121259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camorani, S.; et al. Aptamer targeted therapy potentiates immune checkpoint blockade in triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2020, 39(1), 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249(4968), 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sefah, K.; et al. Development of DNA aptamers using Cell-SELEX. Nature Protocols 2010, 5(6), 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradani, B. S.; et al. Development and characterization of DNA aptamer against retinoblastoma by cell-SELEX and high-throughput sequencing. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 20660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amero, P.; et al. Conversion of RNA aptamer into modified DNA aptamers provides for prolonged stability and enhanced antitumor activity. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2021, 143(20), 7655–7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shraim, A. S.; et al. Therapeutic potential of aptamer–protein interactions. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 2022, 5(10), 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A. N.; et al. G-Quadruplex structure in the ATP-binding DNA aptamer strongly modulates ligand-binding activity. ACS Omega 2024, 9(2), 2105–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; et al. Oligonucleotide aptamers: New tools for targeted cancer therapy. Molecular Therapy – Nucleic Acids 2014, 3, e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudian, F.; et al. Aptamers as an approach to targeted cancer therapy. Cancer Cell International 2024, 24(1), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, D.; Weiner, L. Monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy. Antibodies 2020, 9(3), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A. L.; et al. Development trends for human monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2010, 9(10), 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; et al. RNA-based therapeutics: An overview and prospectus. Cell Death and Disease 2022, 13(7), 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakan, E.; et al. Therapeutic antisense oligonucleotides in oncology: From bench to bedside. Cancers 2024, 16(17), 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosgerau, K.; Hoffmann, T. Peptide therapeutics: Current status and future directions. Drug Discovery Today 2014, 20(1), 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlieghe, P.; et al. Synthetic therapeutic peptides: Science and market. Drug Discovery Today 2009, 15(1-2), 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domsicova, M.; et al. New insights into aptamers: An alternative to antibodies in the detection of molecular biomarkers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(13), 6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnello, L.; et al. Aptamers and antibodies: Rivals or allies in cancer targeted therapy? Exploration of Targeted Anti-Tumor Therapy 2021, 2(1), 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseine, M.; et al. Label-free electrochemical biosensor based on green-synthesized reduced graphene oxide/Fe3O4/nafion/polyaniline for ultrasensitive detection of SKBR3 cell line of HER2 breast cancer biomarker. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 11928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; et al. Selection and application of DNA aptamer against oncogene amplified in breast cancer 1. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2015, 81(5-6), 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; et al. Selection of DNA aptamers against epithelial cell adhesion molecule for cancer cell imaging and circulating tumor cell capture. Analytical Chemistry 2013, 85(8), 4141–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, C. M.; et al. A genome-inspired, reverse selection approach to aptamer discovery. Talanta 2018, 177, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnappan, R.; et al. Anti-VCAM-1 and anti-IL4Rα aptamer-conjugated super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for enhanced breast cancer diagnosis and therapy. Molecules 2020, 25(15), 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; et al. Aptamer-guided silver-gold bimetallic nanostructures with highly active surface-enhanced Raman scattering for specific detection and near-infrared photothermal therapy of human breast cancer cells. Analytical Chemistry 2012, 84(18), 7692–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; et al. Iron(II) phthalocyanine loaded and AS1411 aptamer targeting nanoparticles: A nanocomplex for dual modal imaging and photothermal therapy of breast cancer. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 5927–5949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; et al. Endogenous mRNA triggered DNA-Au nanomachine for in situ imaging and targeted multimodal synergistic cancer therapy. Angewandte Chemie 2021, 60(11), 5948–5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; et al. Aptamer-based photoelectrochemical assay for the determination of MCF-7. Mikrochimica Acta 2020, 187(5), 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos do Carmo, F.; et al. Anti-MUC1 nano-aptamers for triple-negative breast cancer imaging by single-photon emission computed tomography in inducted animals: initial considerations. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; et al. Aptamer-PROTAC conjugates (APCs) for tumor-specific targeting in breast cancer. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2021, 60(43), 23299–23305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Discovery of a novel DNA aptamer for impeding tumor metastasis by blocking the functional activity of target protein on exosome. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 522, 167253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H.; et al. DNA aptamers against Vaccinia-Related Kinase 1 block proliferation in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Biochemical Pharmacology 2020, 175, 113862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichiorri, F.; et al. In vivo NCL targeting affects breast cancer aggressiveness through miRNA regulation. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2013, 210(5), 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; et al. Targeted delivery of doxorubicin to breast cancer cells by aptamer functionalized DOTAP/DOPE liposomes. Oncology Reports 2015, 34(4), 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, Y.; et al. Smart co-delivery of plasmid DNA and doxorubicin using MCM-chitosan-PEG polymerization functionalized with MUC-1 aptamer against breast cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 173, 116465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, Y. D.; et al. Enhanced docetaxel therapeutic effect using dual targeted SRL-2 and TA1 aptamer conjugated micelles in inhibition Balb/c mice breast cancer model. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 24603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibolandi, M.; et al. MUC1 aptamer-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles effectively target breast cancer cells. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2015, 12(8), 2576–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; et al. PEGylated anti-MUC1 aptamer–doxorubicin complex for targeted drug delivery to MCF7 breast cancer cells. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2012, 47(1), 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camorani, S.; et al. Aptamer-targeted therapy potentiates immune checkpoint blockade in triple-negative breast cancer. Molecular Therapy – Nucleic Acids 2020, 22, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; et al. Targeting EGFR/HER2/HER3 with a three-in-one aptamer–siRNA chimera confers superior activity against HER2+ breast cancer. Molecular Therapy – Nucleic Acids 2018, 13, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; et al. Co-delivery of paclitaxel and PLK1-targeted siRNA using aptamer-functionalized cationic liposome for synergistic anti-breast cancer effects in vivo. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrnia, M.; et al. AS1411 aptamer-targeted gold nanoclusters enhance the efficacy of radiation therapy in breast tumor-bearing mice. Nanomedicine 2021, 16(18), 1501–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; et al. PD-L1 aptamer-functionalized degradable hafnium oxide nanoparticles for near infrared-II diagnostic imaging and radiosensitization. Advanced Science 2023, 10(5), 2204568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; et al. Targeted immunotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer by aptamer-engineered NK cells. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2022, 6(2), 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; et al. Photothermal therapeutic response of cancer cells to aptamer-gold nanoparticle-hybridized graphene oxide under NIR illumination. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2015, 7(9), 5097–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, L. E.; et al. Selective photo-assisted eradication of triple-negative breast cancer cells through aptamer decoration of doped conjugated polymer nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14(3), 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. pH- and miRNA-responsive DNA-tetrahedra/metal–organic framework conjugates: Functional sense-and-treat carriers. ACS Nano 2021, 15(4), 7896–7909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. ATP/pH dual responsive nanoparticle with d-[des-Arg10] Kallidin mediated efficient in vivo targeting drug delivery. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nano(bio)sensores electrouímicos y plasmónicos para la cuantificación de biomarcadores de relevancia clínica - CONICET. Available online: https://bicyt.conicet.gov.ar/fichas/produccion/11834746.

- López Santini, B. P. Estudio in silico de la interacción entre el aptámero anti-MUC1 y el epítope de la Mucina 1 (Tesis de Maestría). Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE); 2018; Available online: https://cicese.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/bitstream/1007/2081/1/tesis_L%C3%B3pez_Santini_Brianda_Paola_07_mayo_2018B.pdf.

- Salgado, H.; et al. RegulonDB v12.0: a comprehensive resource of transcriptional regulation in E. coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 52(D1), D255–D264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).