1. Introduction

Homocysteine (Hcy) is an amino acid that is produced during the metabolism of methionine in the one-carbon cycle. Its levels are closely regulated by vitamins B

6 (pyridoxine), B

9 (folate), and B

12 (cobalamin), which act as cofactors in the remethylation and transsulfuration pathways that help dispose of Hcy [

1,

2,

3]. Deficiencies or imbalances in any of the B-vitamins can lead to the elevation of Hcy levels.

Previous research has associated B-vitamins with altered Hcy levels and their subsequent effects on health. Ortiz-Salguero et al. [

4] reviewed evidence suggesting that B-vitamins supplementation may exert protective effects, especially among individuals with metabolic or vascular disorders. Similarly, Nieraad et al. [

5] reported that animals consuming diets deficient in vitamins B

6, B

12, or folate exhibited elevated Hcy levels. Elevated Hcy, in turn, has been implicated not only in cardiovascular disease [

6,

7,

8] but also in microvascular and neurovascular dysfunction, including retinal involvement [

9].

The retina has a specialized protective system called the blood retinal barrier (BRB), which regulates the exchange of molecules between the bloodstream and neural retina, thus maintaining retinal homeostasis and ensuring proper neuronal function [

10]. The disruption of the BRB integrity is a key characteristic of major retinal vascular diseases, including Diabetic Retinopathy (DR), that is associated with disruption of the inner BRB and Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD), that is associated with disruption of the outer BRB [

11,

12]. Research has demonstrated that elevated levels of Hcy are linked to retinal vascular occlusive diseases in humans. For example, patients with retinal vein occlusion typically exhibit higher levels of Hcy [

13].

Our laboratory has extensively investigated the harmful effects of elevated Hcy on the integrity of the BRB [

14,

15,

16], using various mouse models. These include genetic models with cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) deficiency and pharmacologically induced models created through Hcy administration intraocular [

17]. We have explored the underlying mechanisms, which involve oxidative stress resulting from the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

18], mitochondrial dysfunction [

19], endoplasmic reticulum stress [

20], and the activation of vascular N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) [

21]. Additionally, as indicated in our previous study, in vitro experiments with human retinal endothelial and retinal epithelial pigmented cells, main components of inner and outer BRB, have shown that exposure to Hcy leads to the disruption of tight junctions, increased permeability, and oxidative stress. These findings suggest that elevated Hcy may have direct harmful effects on the structure and function of the BRB [

17,

18].

In age-related disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and age-associated macular degeneration, impaired methylation and elevated Hcy have been linked to neuronal apoptosis, inflammation, and compromised microvascular perfusion [

6,

8,

9]. Nutritional modulation through adequate dietary intake or supplementation of B- vitamins can therefore help preserve vascular integrity, reduce neuroinflammatory processes, and potentially slow cognitive and retinal decline. This underscores the importance of optimizing B-vitamin levels as a cost-effective and accessible strategy to slow the progression of age-related vascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

In rodent models, dietary manipulations that modify levels of methionine, folate, and vitamins B

6 and B

12 are used to induce elevated Hcy, providing a platform to investigate its vascular effects. For example, a recent systematic review on cognitive dysfunction reported that deficiencies in vitamins B

6, B

12, or folate consistently increase plasma Hcy levels in mice and rats [

5]. Similarly, an in vivo study examining Hcy-induced cognitive impairment established an elevated Hcy level by feeding mice a specialized diet [

22]. Adjusting the dietary concentrations of vitamins B

6, B

9, and B

12 allows for controlled exploration of Hcy-driven vascular changes.

In this study, we used a specially formulated diet with varying levels of vitamins B6, B9, and B12 to induce elevated Hcy in mice and examined its effects on the BRB. Building on evidence that dietary B-vitamin deficiency causes elevated Hcy levels and vascular dysfunction, we assessed tight junction protein expression, capillary permeability, and retinal vascular morphology. Our findings link nutritional modulation of one-carbon metabolism to BRB integrity, suggesting that elevated Hcy contributes to microvascular barrier breakdown. This model provides insight into how B-vitamin deficiencies may promote retinal vascular diseases such as DR and AMD in humans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Treatments

C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) and cystathionine β-synthase heterozygous (cbs+/-) mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were used in this study. Mice were maintained under controlled environmental conditions with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle at a constant temperature of 22–24 °C, with ad libitum access to food and water. To prevent light-induced retinal damage, illumination at the bottom of the cages was maintained at 1.5 foot-candles. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Oakland University (Protocol # 2022-1160) and adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, as well as the Public Health Service Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Department of Health, Education, and Welfare publication, NIH 80-23).

WT Mice were fed a modified AIN-93G diet (Bio-Serv, Inc., USA) formulated with varying levels of vitamins B

6, B

9 (folic acid), and B

12 to create three dietary conditions: (1) a regular diet (catalog #S3156) containing standard B-vitamin levels, (2) a vitamin-deficient diet (B-Vit (-); catalog #F10342) with reduced B

6, B

9, and B

12, and (3) a vitamin-enriched diet (B-Vit (+); catalog #F10341) with elevated B-vitamin content. Initially, mice were assigned to either the regular or deficient diet groups. 12-16 weeks later, blood samples were collected to confirm B-vitamin deficiency and elevated Hcy levels via serum vitamin B

12 ELISA and Hcy assays. A subset of B-Vit (-) mice was then transitioned to the enriched diet for an additional 16 weeks to evaluate recovery (

Figure 1). The entire experimental procedure, including dietary interventions, monitoring, and group transitions, was conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. All animal procedures followed institutional and ethical guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

2.2. Fluorescent Angiography (FA) and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

Retinal imaging was performed in live mice to assess vascular integrity, retinal morphology, and thickness using fluorescein angiography (FA) and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), conducted with the Phoenix Micron IV system (Phoenix Research Laboratories, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Mice were anesthetized with 1.5–2% isoflurane in oxygen, delivered via a nose cone to ensure stable and consistent sedation throughout the procedure. Before imaging, a 1% tropicamide ophthalmic solution was applied topically to induce pupil dilation and enable clear visualization of the retina.

For FA, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 10–20 μL of 10% fluorescein sodium solution (Apollo Ophthalmics, Newport Beach, CA, USA). Sequential angiographic images were captured at various time points post-injection to monitor dye perfusion and vascular leakage. Quantitative analysis of fluorescein intensity and vascular leakage was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). OCT Imaging was performed using the same Phoenix Micron IV OCT system. To maintain corneal hydration and optical clarity during imaging, Goniovisc 2.5% hypromellose solution (Sigma Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Monticello, IA, USA) was applied to the eye surface. Quantitative measurements of retinal layer thickness were obtained using the OCT system’s proprietary software.

2.3. Western Blot Analysis

After perfusion and euthanizing the experimental mice, their eyes were promptly enucleated to isolate the retinas, which were carefully dissected and immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen to preserve protein integrity, then stored at -80 °C until use. To extract protein, the frozen retinal tissues were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher) to prevent degradation and dephosphorylation of proteins.

Concentrations of protein in the lysates were quantified according to the manufacturer’s protocol for the BCA Protein Assay (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Laemmli sample buffer was added to the protein lysate, and then the mixture was boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Equal amounts of protein from each sample were separated using SDS-PAGE with a gradient gel (4% to 20%, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). After the separation, Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) using a wet or semi-dry transfer system. Following transfer, blocking of the membranes was performed using 5% non-fat dry milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. Blocked membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies specific to target proteins, including anti-Albumin (Cell Signaling, catalog # 4929), anti-Occludin (Invitrogen, catalog # 71-1500), and anti-ZO-1 (Thermo Fisher, catalog # 40-2200). After overnight incubation with primary antibodies, membranes were washed thoroughly with TBST and kept at room temperature with species-specific horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling) for 1 h. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (Pico PLUS, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the signals were detected using a digital chemiluminescence imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and values were normalized to β-actin.

2.4. Vitamin B12 ELISA Assay

To confirm vitamin B deficiency, the concentration of vitamin B12 in serum samples from experimental mice was quantified using a commercial Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit (Aviva Systems Biology, catalog # OKCA00147), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, blood samples were collected from mice and allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min. The samples were then centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain clear serum, which was stored at −20 °C until analysis. For the assay, all reagents, standards, and samples were brought to room temperature before use. Standards of known vitamin B12 concentrations were prepared as specified in the kit instructions to generate a standard curve. A volume of 50 µL of each standard and diluted serum sample was added in duplicate to the wells pre-coated with anti-vitamin B12 antibodies. Then, 50 µL of the biotin-conjugated detection antibody was added to each well, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h.

After incubation, the wells were washed three times with 1X wash buffer to remove unbound materials. Subsequently, 100 µL of HRP-conjugated streptavidin solution was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The wells were then washed again, and 90 µL of TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) substrate solution was added to develop color. The reaction was stopped after 15 min by adding 50 µL of stop solution, and the absorbance was immediately read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA). Vitamin B12 concentrations in serum samples were calculated from the standard curve generated using known concentrations of the vitamin. The results were expressed as pg/mL of serum. All samples were analyzed in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

2.5. Homocysteine Assay (Fluorometric)

Following the establishment of B-vitamin deficiency, serum homocysteine concentrations were measured to confirm its associated elevation. The quantification of homocysteine was performed using a commercial Homocysteine Assay Kit (Abcam, catalog # ab228559) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After the collection of Blood samples, they were allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min, then centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain serum, and were stored at −20 °C until further biochemical analysis. Before the assay, all reagents, standards, and samples were equilibrated to room temperature. Standards with known concentrations of homocysteine were prepared to generate a standard calibration curve. For the fluorometric assay, 170 µL of each serum sample or standard was added to the designated wells of a 96-well microplate. The enzymatic reaction mixture provided in the kit, comprising homocysteine converting enzyme, cofactors, and substrate, was then added to each well according to the protocol.

The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. allowing enzymatic conversion of homocysteine to a detectable product. After incubation, fluorescence was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA) at the appropriate wavelength. Homocysteine concentrations in the serum samples were calculated by interpolating the fluorescence values from the standard curve. The results were expressed as µmol/L of serum. All measurements were performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 9 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between experimental groups were evaluated using either a two-tailed t-test or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When ANOVA indicated significant differences, Tukey’s post hoc test was applied to determine specific group comparisons. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

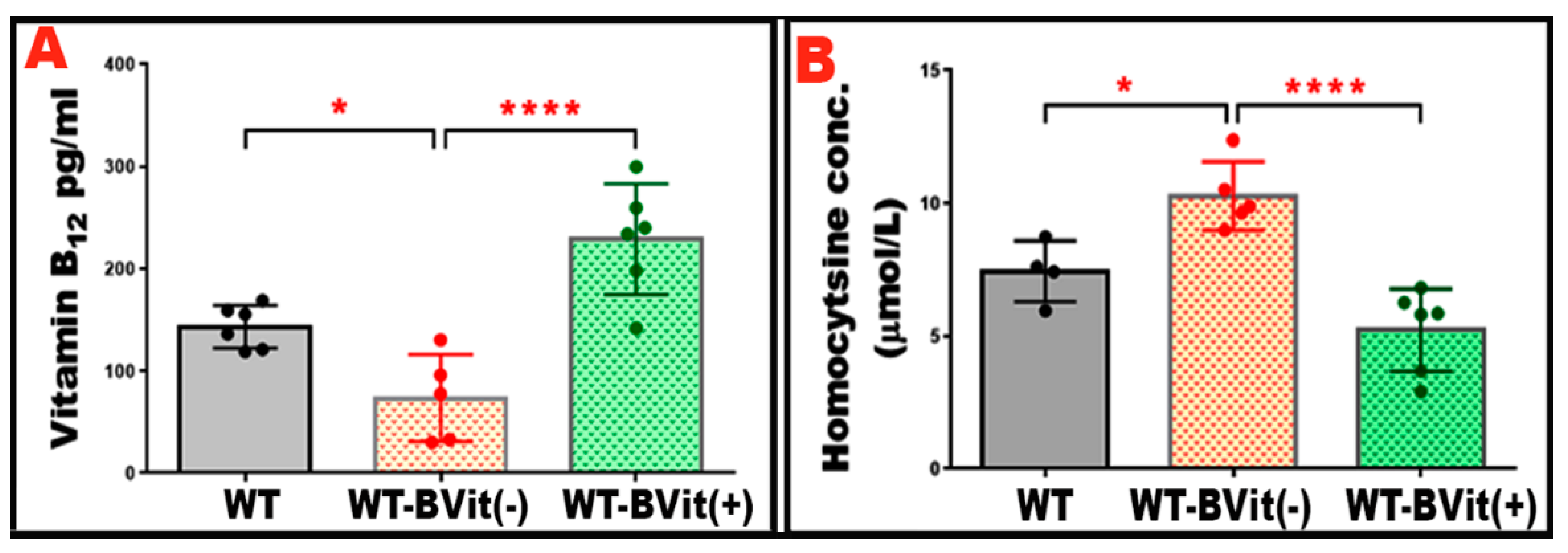

3.1. Dietary B-Vitamin Manipulation Alters Serum Vitamin B12 and Homocysteine in Mice

To evaluate the effects of dietary changes in B-vitamins on systemic vitamin B

12 levels and Hcy metabolism, serum vitamin B

12 and Hcy levels were measured in the experimental groups: WT, WT-B-Vit (-), and WT-B-Vit (+). WT mice on the B-vitamin deficient diet showed a significant decrease in serum vitamin B

12 concentrations compared to those on the regular diet. In contrast, the animals receiving the B-vitamin supplemented diet displayed elevated vitamin B

12 levels when compared to both WT that received the B-deficient diet, confirming the effectiveness of dietary modulation (

Figure 2A).

Serum Hcy concentrations were measured to evaluate the development of elevated Hcy levels. A significant increase in serum Hcy levels was observed in the mice fed the B-vitamin deficient diet. While supplementing with B-vitamins effectively normalized Hcy levels (

Figure 2B), confirming that dietary enrichment reversed the elevated Hcy induced in our nutritional model. These findings demonstrate that deficiency of B-vitamins reliably elevates serum Hcy in mice, consistent with impaired one-carbon metabolism due to insufficient cofactors (vitamin B

12, folate, B

6). Conversely, dietary B-vitamin repletion restores B

12 status and normalizes Hcy, confirming the reversibility of diet-induced metabolic disturbance. This supports the utility of dietary B-vitamin manipulation as a robust model for studying elevated Hcy level and its downstream effects (e.g., vascular, cognitive, epigenetic) in animal studies.

The concept of diet-induced modulation of Hcy via B-vitamin content is well established in the literature. For instance, a review of more than a hundred murine studies found negative correlations between dietary B

12 and other one-carbon vitamins and circulating homocysteine levels [

23].

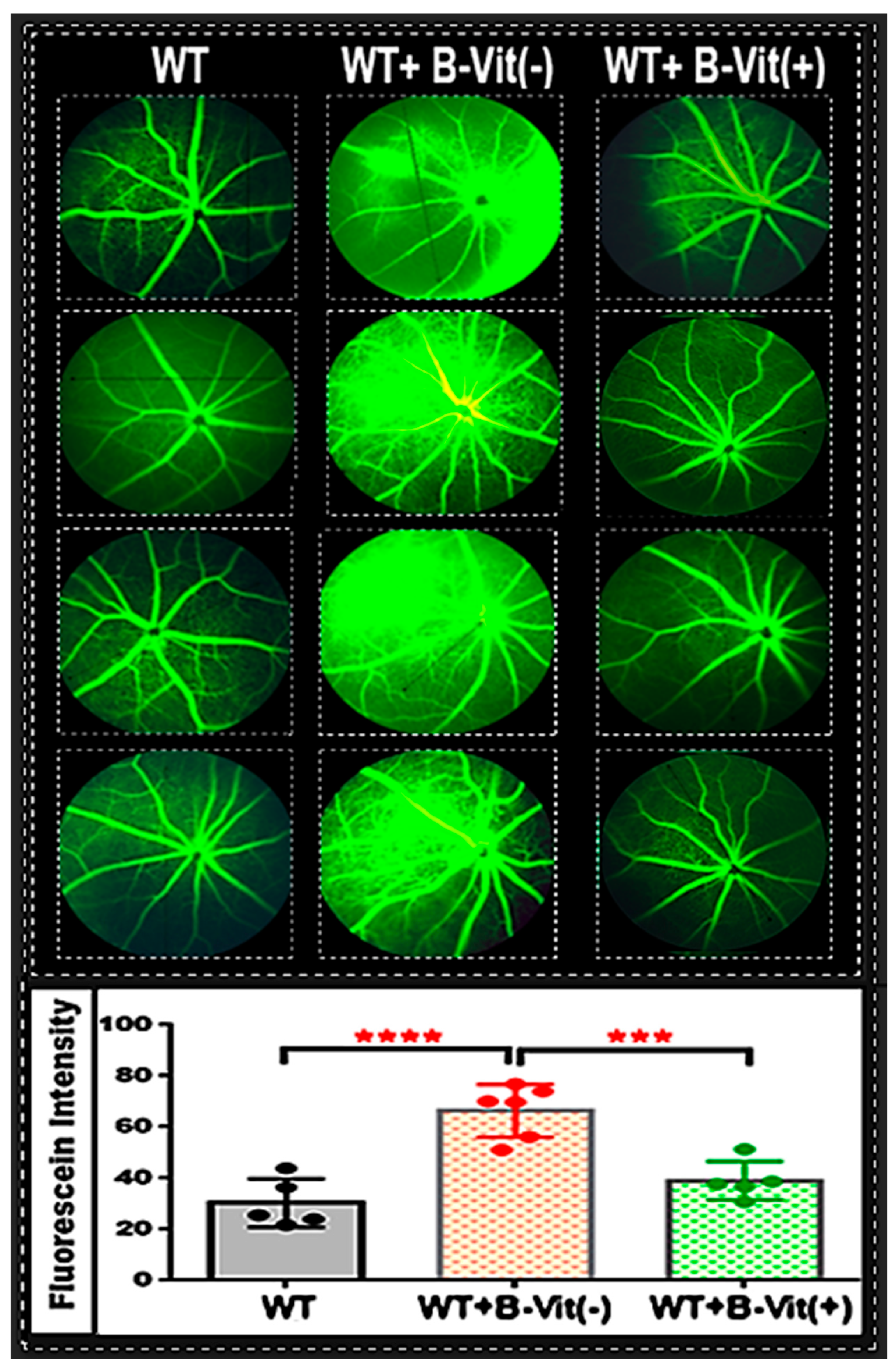

3.2. Dietary B-Vitamin Deficiency Induces Retinal Vascular Leakage via Blood Retina Barrier Disruption in Mice, which is attenuated by Vitamin B Supplementation

The BRB is crucial for maintaining retinal homeostasis and ensuring visual function. Impairment of the BRB, which leads to vascular leakage, is a key characteristic of retinal vascular diseases such as DR and AMD [

12]. After confirming the establishment of our nutritionally induced Hcy model, we evaluated the BRB integrity. As previously reported in our studies, elevated Hcy disrupts both the inner and outer BRB integrity, both in vivo and in vitro. This disruption occurs through mechanisms that involve oxidative stress, inflammation, and the downregulation of tight-junction proteins [

14]. In this context, we investigated whether a dietary deficiency of B-vitamins, which raises systemic Hcy levels, would compromise BRB integrity in the proposed nutritional mouse model. We conducted fundus fluorescein angiography (FA) in living mice to assess retinal vascular leakage under different dietary B-vitamin conditions: deficient, standard, and supplemented.

The FA images showed increased vascular leakage (indicated by diffuse hyperfluorescence, vessel wall staining, and leakage extending into the surrounding retinal tissue).in the retinas of mice on B-vitamin deficient diet (WT-B-Vit (-)) compared to those on a regular diet (

Figure 3), which was successfully mitigated by B-vitamin supplementation. Quantitative analysis of fluorescein intensity confirmed a significant increase in vascular leakage in the B-vitamin deficient group, which was notably reduced in mice that received a B-vitamin supplemented diet (WT-B-Vit (+)). These findings demonstrate that dietary B-vitamin deficiency compromises BRB integrity, resulting in vascular leakage in the retina, an effect that is reversed by B-vitamin supplementation. This strongly supports a mechanistic link between B-vitamin–dependent Hcy metabolism and retinal vascular homeostasis.

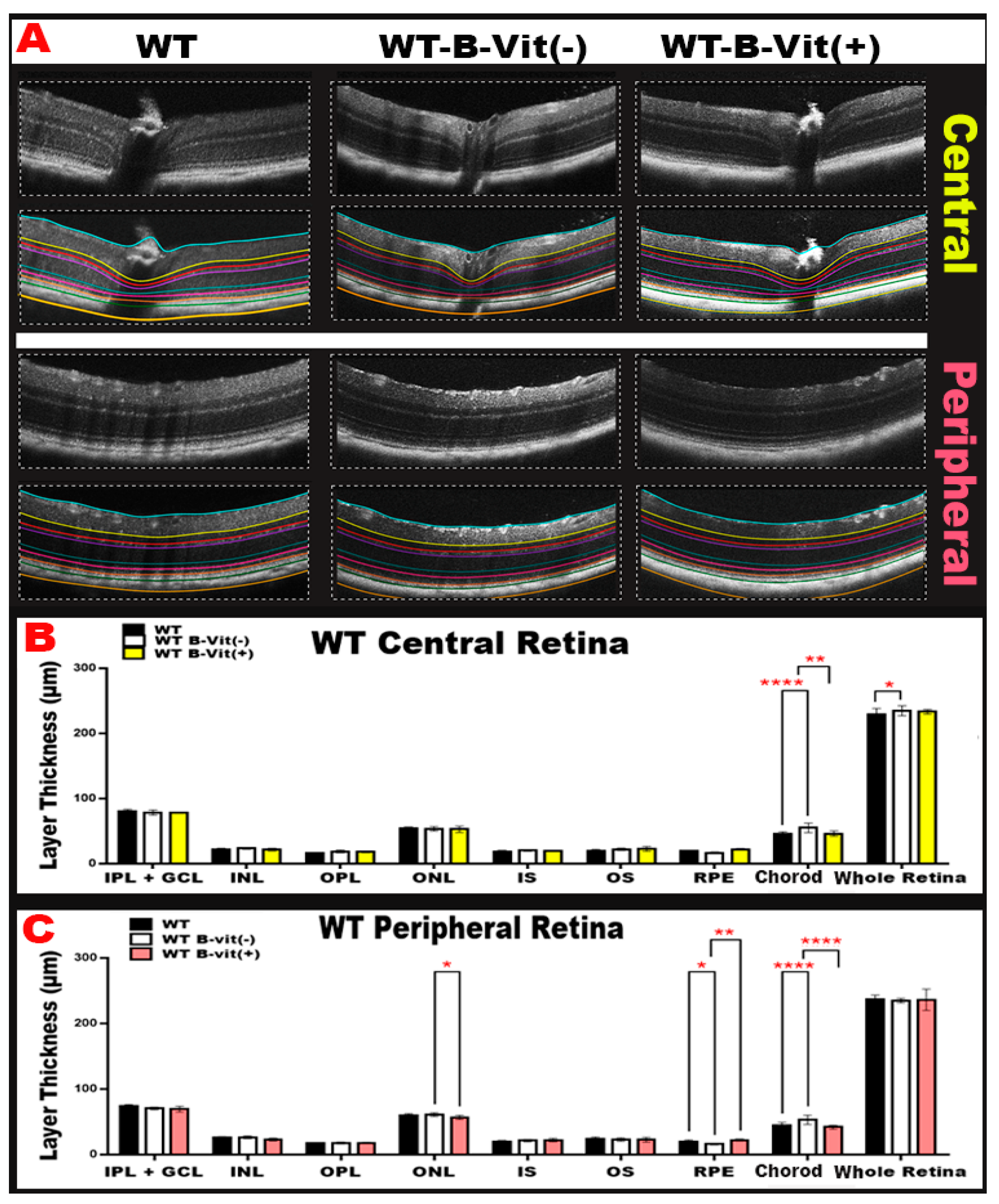

3.3. Dietary B-Vitamin Deficiency Induces Structural Retinal Alterations and Choroidal Neovascular Changes, which are prevented by vitamin B supplementation.

To determine how B-vitamin status affects retinal morphology, we performed optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging across diet-modified WT groups. OCT imaging revealed structural changes in the retinas of mice deficient in B-vitamins. These changes included alterations in retinal thickness, localized inflammation, and areas of neovascularization (

Figure 4B). Quantitative analysis of OCT images (

Figure 4B,C). reflected these findings by showing significant changes in the thickness of different retinal layers in the B-vitamin deficient group compared to the WT controls (mainly in the RPE/choroid). A deficiency in B vitamins significantly increased choroidal thickness, indicating the presence of neovascularization, when compared to a regular diet group. However, this condition was restored to normal with B-vitamin supplementation in both the peripheral and central retina. Additionally, B vitamin deficiency led to a significant decrease in RPE thickness, suggesting cell death, compared to the regular diet. This thickness was also restored to normal levels with a diet rich in B-vitamins, particularly in the peripheral retina (

Figure 4C). Furthermore, B-vitamin supplementation protected the retina from the damaging effects of elevated Hcy, which is induced by B-vitamin deficiency, by restoring RPE thickness and reducing choroidal neovascularization. Collectively, these findings indicate that dietary B-vitamin deficiency drives structural retinal damage, including RPE loss and choroidal neovascular remodeling, while B-vitamin supplementation protects the retina by normalizing layer thickness and mitigating Hcy-induced injury.

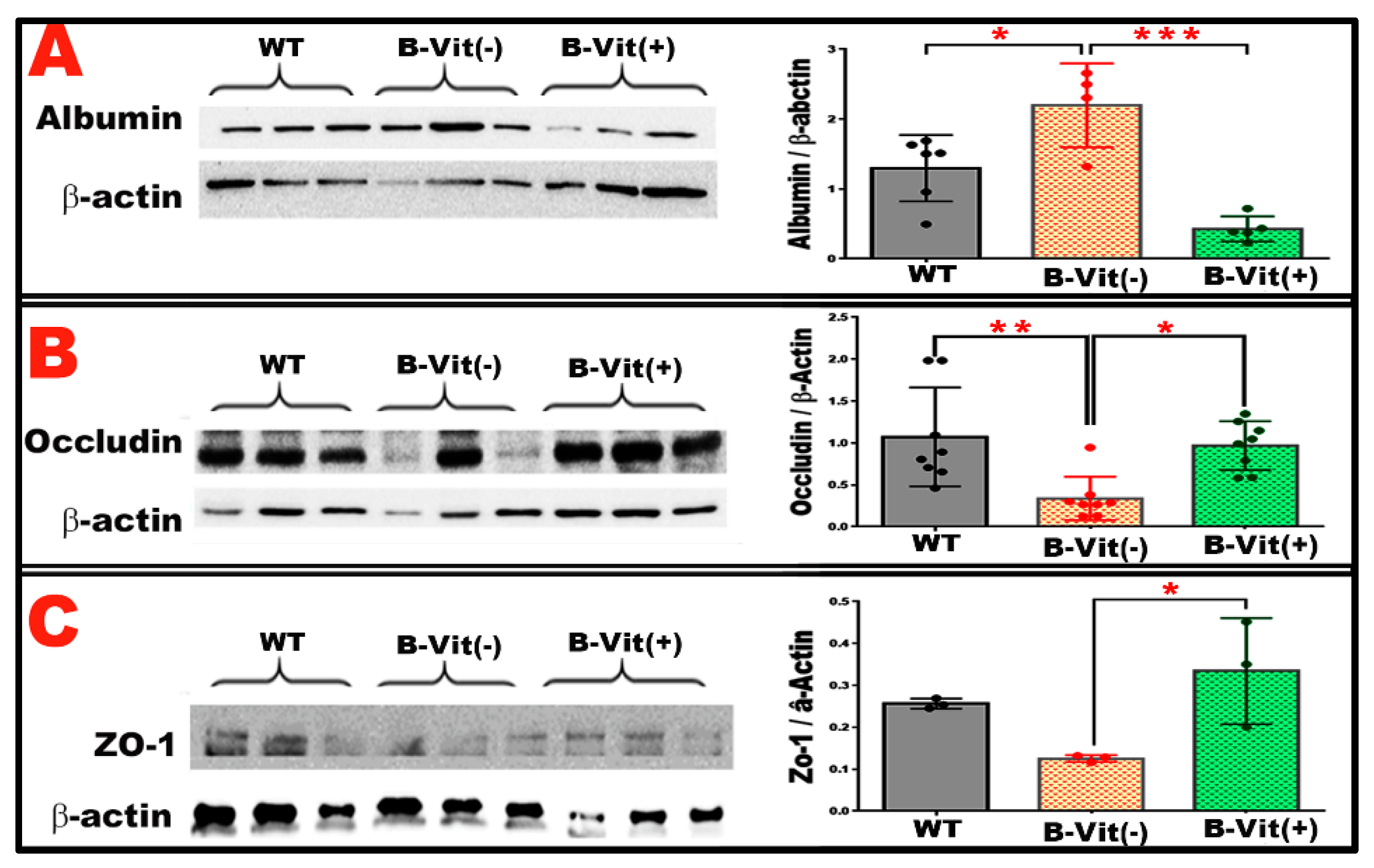

3.4. B-Vitamin Deficiency Disrupts Tight Junction Integrity and Increases Retinal Albumin Leakage Through Homocysteine-Mediated BRB Breakdown

The BRB depends on tight junction proteins such as occludin and ZO-1 to maintain vascular integrity and prevent the extravasation of serum proteins into retinal tissue. Elevated Hcy, which arises from impaired one-carbon metabolism during B-vitamin deficiency, has been shown to destabilize tight junctions, increase endothelial permeability, and promote retinal barrier breakdown [

14]. Given these established effects of elevated Hcy, we wanted to determine whether dietary B-vitamin deficiency disrupts BRB molecular components and whether B-vitamin supplementation can reverse these changes.

Consistent with the angiographic and OCT findings, we investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying BRB dysfunction caused by B-vitamin deficiency and elevated Hcy. Following euthanasia and perfusion, retinas were collected for Western blot analysis (WB) of albumin accumulation and the tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 (

Figure 5). As shown in

Figure 5A, leaked retinal albumin levels were significantly elevated in mice fed the B-vitamin deficient diet, indicating increased vascular permeability and BRB breakdown. However, this albumin accumulation was markedly reduced in mice receiving B-vitamin supplementation, demonstrating a restoration of barrier integrity.

Analysis of tight junction protein expression revealed that both occludin and ZO-1 were significantly decreased in the B-vitamin deficient group compared with WT controls (

Figure 5B,C). B-vitamin supplementation effectively restored the expression levels of both proteins to near-normal levels. Together, these findings show that dietary B-vitamin deficiency compromises BRB integrity by reducing tight junction protein expression and increasing vascular leakage. Conversely, dietary B-vitamin supplementation mitigates these pathological effects, restoring tight junction organization and maintaining the structural and functional integrity of the BRB.

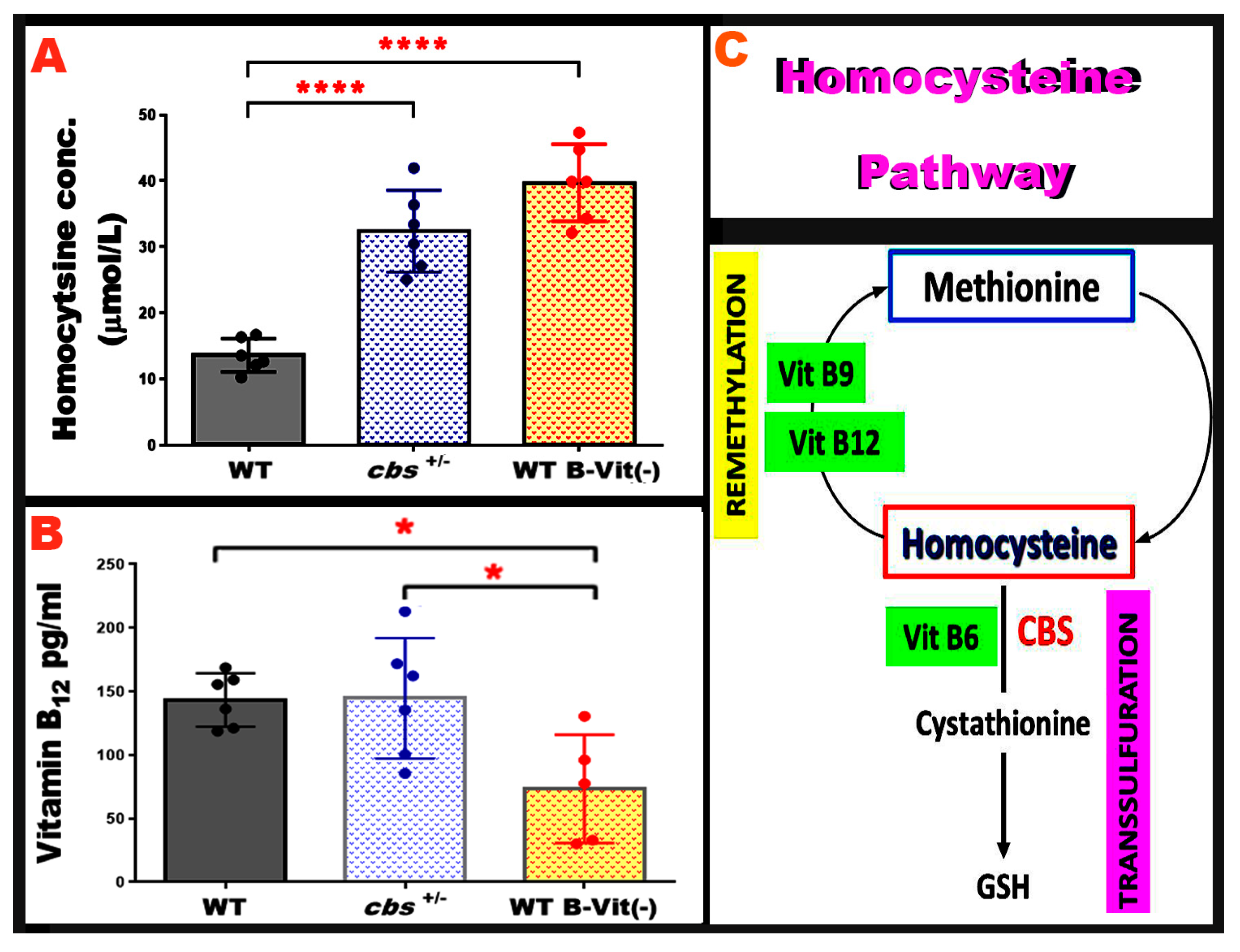

3.5. Nutritional B-Vitamin Deficiency Elevates Homocysteine to Levels Comparable to the Genetic cbs+/- Model

Elevated Hcy levels can be induced through genetic or nutritional disruption of homocysteine metabolism. The heterozygous cystathionine β-synthase deficient mouse (

cbs+/-) is a well-established genetic model of moderately elevated Hcy and has been extensively used to study the vascular and neurodegenerative consequences of elevated Hcy [

21]. However, dietary B-vitamin deficiency provides a non-genetic approach that elevates Hcy by impairing the remethylation and transsulfuration pathways. To validate the strength of our nutritional HHcy model, we directly compared plasma Hcy levels across both models.

Hcy concentrations were contrasted in mice fed the B-vitamin deficient diet with those in our genetically induced elevated Hcy model (

cbs+/-). As expected,

cbs+/- mice showed significantly elevated Hcy levels relative to WT controls, consistent with previous reports. Remarkably, mice on the B-vitamin deficient diet exhibited a comparable magnitude of Hcy elevation, demonstrating that nutritional restriction of B-vitamins is equally effective in inducing elevated Hcy (

Figure 6A). Furthermore, serum vitamin B

12 level was compared across both models, and results showed that it is markedly lowered in the nutritionally induced model when compared to WT and

cbs+/-, as shown in

Figure 6B. Together, these data confirm that the dietary B-vitamin deficiency model effectively induces elevated Hcy to levels similar to the genetic

cbs+/- model.

4. Discussion

In this study, we implemented a long-term dietary approach using C57BL/6 WT mice to examine varying levels of B-vitamins intake (B6, B9, B12) over a period of 32 weeks. We confirmed vitamin B12 deficiency using ELISA and subsequently measured serum Hcy levels and retinal vascular endpoints. Our findings revealed that: (1) a dietary deficiency of B-vitamins consistently led to elevated serum Hcy levels, and that supplementation with B-vitamins reversed this elevation; (2) elevated Hcy was linked to increased retinal vascular leakage, as assessed by FA and OCT, along with structural changes in the retina; and (3) vitamin B supplementation alleviated indicators of BRB dysfunction, such as elevated retinal albumin levels and decreased expression of the tight junction proteins, occludin and ZO-1. These results support the notion that one-carbon metabolism, facilitated by B-vitamins, plays a critical role in maintaining the integrity of the retinal vascular barrier. Additionally, nutritional adjustments of B-vitamins and Hcy levels can influence the function of the blood-retinal barrier.

Our results are consistent with previous studies indicating that elevated Hcy contributes to microvascular dysfunction [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], and tight junction disruption [

30,

31]. Furthermore, genetic animal models of elevated Hcy, such as those deficient in the CBS enzyme or knockout models, show retinal vascular leakage and disruption of the blood-retinal barrier [

32]. Our findings build upon this research by demonstrating that a dietary deficiency in B-vitamins produces similar outcomes. Additionally, we found that enriching the diet with B-vitamins can largely reverse these effects, thereby linking diet-driven one-carbon metabolism to the integrity of retinal microvasculature.

In our previous studies, we reported that the BRB is dysfunctional in

cbs+/- mice. We observed harmful effects of elevated Hcy levels on the integrity of both the inner and outer BRB. These effects were noted both in vivo, using

cbs+/- and

cbs-/- mice, and in vitro, using cultured retinal cells [

17,

33]. Additionally, we explored different possible underlying mechanisms that disrupt the BRB [

15]. Our current study confirms these mechanisms through observed decreases in tight junction protein levels and increased albumin leakage.

The dietary intervention demonstrates that the levels of vitamins B

6, B

9, and B

12 are crucial factors influencing systemic Hcy levels, consistent with human studies showing that low levels of B-vitamins are associated with elevated Hcy and increased vascular risk [

34], Clinical studies have shown similar results regarding the beneficial effects of B vitamins, especially folic acid, in maintaining vascular health and reducing the incidence of microvascular disorders, including AMD [

35]. Notably, our supplementation group reveals that higher B-vitamin intake can lower Hcy levels and improve vascular changes in the retina, indicating that nutritional interventions may help prevent or reverse microvascular barrier damage linked to elevated Hcy.

Our results demonstrated that elevated vascular leakage shown by FA, altered retinal thickness, and structural changes observed through OCT in vitamin B-deficient groups indicate that elevated Hcy is not just a biomarker; it has direct effects on the retina. These findings align with our previous reports of retinal ganglion cell loss, retinal thinning, and capillary dropout in models of elevated Hcy level [

14]. The partial restoration of retinal thickness and the reduced leakage observed in the groups supplemented with B-vitamins suggest that some of these changes may be reversible when the underlying metabolic issue is addressed. Furthermore, the Western blot results indicated an increase in albumin levels and a decrease in tight junction proteins in the retinas of B-vitamin-deficient mice, which normalizes with supplementation. This provides molecular evidence of a compromised barrier. The current data strongly suggest that the endothelial tight junction complex is a significant site of damage, consistent with previous research [

21].

Retinal vascular leakage and BRB impairment are key factors in major retinal diseases like DR and AMD. Our data may be clinically relevant, as studies have linked elevated Hcy levels to retinal vascular diseases [

14,

15,

21,

36,

37,

38]. The current study indicates that ensuring adequate B-vitamin levels may serve as a preventive or supportive strategy for promoting retinal vascular health, especially in populations at risk of elevated Hcy, such as the elderly, individuals with renal disease, and those with vitamin B deficiencies. The finding that supplementation reduced damage in our model reinforces the idea that this is a nutritional risk factor that can be modified.

In this study, we propose a safe nutritional model of elevated Hcy and BRB disruption, an important pathological feature shared across many retinal diseases, particularly those associated with aging. Aging populations are especially vulnerable to B-vitamin deficiency due to multiple factors, including inadequate dietary intake, malabsorption, drug interactions, and comorbid age-related conditions that impair B-vitamin absorption.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our data provide considerable experimental evidence that a dietary deficiency of vitamins B6, B9, and B12 can lead to higher Hcy levels, which subsequently cause disruptions in the BRB and increase retinal vascular leakage in mice. However, supplementation with B-vitamins can reverse these harmful changes. These findings underscore the critical role of one-carbon metabolism and adequate B-vitamin availability in maintaining retinal vascular health and suggest that nutritional interventions may represent a practical strategy to preserve BRB integrity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.; methodology, O.E., N.P., H.A., and L.S.; software, O.E., and N.P.; formal analysis, A.T., and H.A.; resources, A.T.; data curation, O.E., N.P., H.A., and L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing, A.T; visualization, A.T.; supervision, A.T.; project administration, A.T.; funding acquisition, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NIH-1R01EY029751.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures were conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and performed according to the Public Health Service Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Department of Health, Education, and Welfare publication, NIH 80-23) and Oakland University guidelines, and followed the ARVO Statement for Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMD |

Age-related Macular Degeneration |

| BRB |

Blood retinal barrier |

| CBS |

Cystathionine β-synthase |

| DR |

Diabetic Retinopathy |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FA |

Fluorescein angiography |

| GCL |

Ganglion cell layer |

| Hcy |

Homocysteine |

| INL |

Inner nuclear layer |

| IPL |

Inner plexiform layer |

| IS |

Inner segment |

| NMDARs |

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors |

| OCT |

Optical coherence tomography |

| ONL |

Outer nuclear layer |

| OPL |

Outer plexiform layer |

| OS |

Outer segment |

| RPE |

Retinal pigment epithelium |

| WB |

Western blot analysis |

| WT |

Wild-type |

References

- Wu, D.F.; Yin, R.X.; Deng, J.L. Homocysteine, hyperhomocysteinemia, and H-type hypertension. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2024, 31, 1092-1103. [CrossRef]

- Zaric, B.L.; Obradovic, M.; Bajic, V.; Haidara, M.A.; Jovanovic, M.; Isenovic, E.R. Homocysteine and Hyperhomocysteinaemia. Curr Med Chem 2019, 26, 2948-2961. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Palfrey, H.A.; Pathak, R.; Kadowitz, P.J.; Gettys, T.W.; Murthy, S.N. The metabolism and significance of homocysteine in nutrition and health. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2017, 14, 78. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Salguero, C.; Romero-Bernal, M.; Gonzalez-Diaz, A.; Doush, E.S.; Del Rio, C.; Echevarria, M.; Montaner, J. Hyperhomocysteinemia: Underlying Links to Stroke and Hydrocephalus, with a Focus on Polyphenol-Based Therapeutic Approaches. Nutrients 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Nieraad, H.; Pannwitz, N.; Bruin, N.; Geisslinger, G.; Till, U. Hyperhomocysteinemia: Metabolic Role and Animal Studies with a Focus on Cognitive Performance and Decline-A Review. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, T.; Mu, G.; Chen, Y.; Xiang, B.; Zhu, J.; Shen, Z. Dysregulated homocysteine metabolism and cardiovascular disease and clinical treatments. Mol Cell Biochem 2025, 480, 4907-4920. [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, H.; Witucki, L. Homocysteine Metabolites, Endothelial Dysfunction, and Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Esse, R.; Barroso, M.; Tavares de Almeida, I.; Castro, R. The Contribution of Homocysteine Metabolism Disruption to Endothelial Dysfunction: State-of-the-Art. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Weekman, E.M.; Rogers, C.B.; Sudduth, T.L.; Wilcock, D.M. Hyperhomocysteinemia-induced VCID results in visual deficits, reduced neuroinflammation and vascular alterations in the retina. J Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 23. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Ma, J.J.; Li, X.; Yan, H.Q.; Gui, Y.K.; Yan, Z.X.; You, M.F.; Zhang, P. The role of transcytosis in the blood-retina barrier: from pathophysiological functions to drug delivery. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1565382. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, F.; Campbell, M. The blood-retina barrier in health and disease. FEBS J 2023, 290, 878-891. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yu, X.W.; Zhang, D.D.; Fan, Z.G. Blood-retinal barrier as a converging pivot in understanding the initiation and development of retinal diseases. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133, 2586-2594. [CrossRef]

- Abu El-Asrar, A.M.; Abdel Gader, A.G.; Al-Amro, S.A.; Al-Attas, O.S. Hyperhomocysteinemia and retinal vascular occlusive disease. Eur J Ophthalmol 2002, 12, 495-500. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.; Samra, Y.A.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; Al-Shabrawey, M. Implication of Hyperhomocysteinemia in Blood Retinal Barrier (BRB) Dysfunction. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Elsherbiny, N.M.; Sharma, I.; Kira, D.; Alhusban, S.; Samra, Y.A.; Jadeja, R.; Martin, P.; Al-Shabrawey, M.; Tawfik, A. Homocysteine Induces Inflammation in Retina and Brain. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.; Mohamed, R.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; DeAngelis, M.M.; Bartoli, M.; Al-Shabrawey, M. Homocysteine: A Potential Biomarker for Diabetic Retinopathy. J Clin Med 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.S.; Mander, S.; Hussein, K.A.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; Smith, S.B.; Al-Shabrawey, M.; Tawfik, A. Hyperhomocysteinemia disrupts retinal pigment epithelial structure and function with features of age-related macular degeneration. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 8532-8545. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.; Sharma, I.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Saleh, H.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; Fulzele, S.; Elmasry, K.; Smith, S.B.; Al-Shabrawey, M.; Tawfik, A. Hyperhomocysteinemia Alters Retinal Endothelial Cells Barrier Function and Angiogenic Potential via Activation of Oxidative Stress. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11952. [CrossRef]

- Samra, Y.A.; Zaidi, Y.; Rajpurohit, P.; Raghavan, R.; Cai, L.; Kaddour-Djebbar, I.; Tawfik, A. Warburg Effect as a Novel Mechanism for Homocysteine-Induced Features of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Elmasry, K.; Mohamed, R.; Sharma, I.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; Liu, Y.; Al-Shabrawey, M.; Tawfik, A. Epigenetic modifications in hyperhomocysteinemia: potential role in diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 12562-12590. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.; Mohamed, R.; Kira, D.; Alhusban, S.; Al-Shabrawey, M. N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation, novel mechanism of homocysteine-induced blood-retinal barrier dysfunction. J Mol Med (Berl) 2021, 99, 119-130. [CrossRef]

- Troen, A.M.; Shea-Budgell, M.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Smith, D.E.; Selhub, J.; Rosenberg, I.H. B-vitamin deficiency causes hyperhomocysteinemia and vascular cognitive impairment in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 12474-12479. [CrossRef]

- Brutting, C.; Hildebrand, P.; Brandsch, C.; Stangl, G.I. Ability of dietary factors to affect homocysteine levels in mice: a review. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2021, 18, 68. [CrossRef]

- Waithe, O.Y.; Anderson, A.; Muthusamy, S.; Seplovich, G.M.; Tharakan, B. Homocysteine Induces Brain and Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cell Barrier Damage and Hyperpermeability via NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway Differentially. Microcirculation 2025, 32, e70019. [CrossRef]

- Hurjui, L.L.; Tarniceriu, C.C.; Serban, D.N.; Lozneanu, L.; Bordeianu, G.; Nedelcu, A.H.; Panzariu, A.C.; Jipu, R.; Hurjui, R.M.; Tanase, D.M.; et al. Homocysteine Attack on Vascular Endothelium-Old and New Features. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B.; Fatima, F.; Seth, S.; Sinha Roy, S. Moderate Elevation of Homocysteine Induces Endothelial Dysfunction through Adaptive UPR Activation and Metabolic Rewiring. Cells 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Chu, J.; Lin, H.; Zhu, G.; Qian, J.; Yu, Y.; Yao, T.; Ping, F.; Chen, F.; Liu, X. Mechanism of homocysteine-mediated endothelial injury and its consequences for atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 1109445. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Wang, Q.S.; Yang, X.; Zhu, D.; Sun, Y.; Niu, N.; Yao, J.; Dong, B.H.; Jiang, S.; Tang, L.L.; et al. Homocysteine Causes Endothelial Dysfunction via Inflammatory Factor-Mediated Activation of Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC). Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 672335. [CrossRef]

- Pushpakumar, S.; Kundu, S.; Sen, U. Endothelial dysfunction: the link between homocysteine and hydrogen sulfide. Curr Med Chem 2014, 21, 3662-3672. [CrossRef]

- Gagat, M.; Grzanka, D.; Izdebska, M.; Grzanka, A. Effect of L-homocysteine on endothelial cell-cell junctions following F-actin stabilization through tropomyosin-1 overexpression. Int J Mol Med 2013, 32, 115-129. [CrossRef]

- Beard, R.S., Jr.; Reynolds, J.J.; Bearden, S.E. Hyperhomocysteinemia increases permeability of the blood-brain barrier by NMDA receptor-dependent regulation of adherens and tight junctions. Blood 2011, 118, 2007-2014. [CrossRef]

- Dayal, S.; Lentz, S.R. Murine models of hyperhomocysteinemia and their vascular phenotypes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008, 28, 1596-1605. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.; Markand, S.; Al-Shabrawey, M.; Mayo, J.N.; Reynolds, J.; Bearden, S.E.; Ganapathy, V.; Smith, S.B. Alterations of retinal vasculature in cystathionine-beta-synthase heterozygous mice: a model of mild to moderate hyperhomocysteinemia. Am J Pathol 2014, 184, 2573-2585. [CrossRef]

- Koklesova, L.; Mazurakova, A.; Samec, M.; Biringer, K.; Samuel, S.M.; Busselberg, D.; Kubatka, P.; Golubnitschaja, O. Homocysteine metabolism as the target for predictive medical approach, disease prevention, prognosis, and treatments tailored to the person. EPMA J 2021, 12, 477-505. [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, G. Vitamins, Vascular Health and Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Devi, V.L.J.; Panigrahi, P.K.; Minj, A.; Hanisha, D. Clinical profile of patients with retinal vein occlusion and its correlation with serum homocysteine levels. BMC Ophthalmol 2025, 25, 458. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Wang, J.; Barwick, S.R.; Yoon, Y.; Smith, S.B. Effect of long-term chronic hyperhomocysteinemia on retinal structure and function in the cystathionine-beta-synthase mutant mouse. Exp Eye Res 2022, 214, 108894. [CrossRef]

- Navneet, S.; Cui, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Kaidery, N.A.; Thomas, B.; Bollinger, K.E.; Yoon, Y.; Smith, S.B. Excess homocysteine upregulates the NRF2-antioxidant pathway in retinal Muller glial cells. Exp Eye Res 2019, 178, 228-237. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experimental timeline for dietary modulation and outcome assessments in mice. Mice were initially placed on either a regular diet or a B-vitamin deficient diet. After 12–16 weeks on the assigned diet, blood samples were collected for vitamin B12 and Hcy assays. A subgroup of animals on the deficient diet was subsequently switched to a B vitamin-rich diet. 16 weeks later, mice underwent imaging assessments, followed by euthanasia for tissue collection and further analysis.

Figure 1.

Experimental timeline for dietary modulation and outcome assessments in mice. Mice were initially placed on either a regular diet or a B-vitamin deficient diet. After 12–16 weeks on the assigned diet, blood samples were collected for vitamin B12 and Hcy assays. A subgroup of animals on the deficient diet was subsequently switched to a B vitamin-rich diet. 16 weeks later, mice underwent imaging assessments, followed by euthanasia for tissue collection and further analysis.

Figure 2.

Serum Vitamin B12 and Hcy levels. Serum concentrations of vitamin B12 and Hcy were measured to assess B-vitamin status in the experimental groups. (A) shows that WT mice fed a vitamin B-deficient diet (WT-B-Vit (-)) exhibited significantly reduced serum vitamin B12 levels, confirming the presence of B-vitamin deficiency. This deficiency was restored through B-vitamin supplementation, as demonstrated in the WT-B-Vit (+) groups. (B) The graph illustrates serum Hcy levels across the three groups (WT, WT-B-Vit (-), and WT-B-Vit (+)). It reveals that Hcy levels were significantly higher in the WT-B-Vit (-) group compared to the WT group. This elevation was notably reduced when shifting to a B-vitamin-enriched diet. * p < 0.05, n = 6.

Figure 2.

Serum Vitamin B12 and Hcy levels. Serum concentrations of vitamin B12 and Hcy were measured to assess B-vitamin status in the experimental groups. (A) shows that WT mice fed a vitamin B-deficient diet (WT-B-Vit (-)) exhibited significantly reduced serum vitamin B12 levels, confirming the presence of B-vitamin deficiency. This deficiency was restored through B-vitamin supplementation, as demonstrated in the WT-B-Vit (+) groups. (B) The graph illustrates serum Hcy levels across the three groups (WT, WT-B-Vit (-), and WT-B-Vit (+)). It reveals that Hcy levels were significantly higher in the WT-B-Vit (-) group compared to the WT group. This elevation was notably reduced when shifting to a B-vitamin-enriched diet. * p < 0.05, n = 6.

Figure 3.

Dietary B-Vitamin Deficiency Induces Retinal Vascular Leakage. Representative fundus FA images of mouse retinas, which were used to evaluate the integrity of the BRB. Mice fed the B-vitamin deficient diet (WT-B-Vit (-)) exhibited significant vascular leakage (areas of hyperfluorescence and dye leakage beyond the vessel borders) compared to the control WT mice. However, this leakage was markedly reduced following B-vitamin supplementation (WT-B-Vit (+)). The accompanying graph displays the quantification of fluorescein intensity as measured using ImageJ. It reveals that mice on the B-vitamin deficient diet had a significantly higher fluorescein intensity compared to those on a regular diet. Conversely, vitamin supplementation effectively repaired the BRB and substantially decreased fluorescein leakage. * p < 0.05, n = 6.

Figure 3.

Dietary B-Vitamin Deficiency Induces Retinal Vascular Leakage. Representative fundus FA images of mouse retinas, which were used to evaluate the integrity of the BRB. Mice fed the B-vitamin deficient diet (WT-B-Vit (-)) exhibited significant vascular leakage (areas of hyperfluorescence and dye leakage beyond the vessel borders) compared to the control WT mice. However, this leakage was markedly reduced following B-vitamin supplementation (WT-B-Vit (+)). The accompanying graph displays the quantification of fluorescein intensity as measured using ImageJ. It reveals that mice on the B-vitamin deficient diet had a significantly higher fluorescein intensity compared to those on a regular diet. Conversely, vitamin supplementation effectively repaired the BRB and substantially decreased fluorescein leakage. * p < 0.05, n = 6.

Figure 4.

(A) Representative OCT images from each WT group under the customized B-vitamin regimen (WT, WT-B-Vit (-), and WT-B-Vit (+)) showing central and peripheral retinal structural changes. (B,C) The graphical representations of retinal thickness quantification for both central and peripheral retina reveal significant alterations primarily in the RPE/choroid. B-vitamin deficiency caused increased choroidal thickness (suggestive of choroidal neovascularization) and reduced RPE thickness, both of which were restored by B-vitamin supplementation. (IPL/GCL, inner plexiform layer/ganglion cell layer, INL inner nuclear layer, OPL outer plexiform layer, ONL outer nuclear layer, IS inner segment, OS outer segment, RPE retinal pigment epithelium). * p < 0.05, n = 24.

Figure 4.

(A) Representative OCT images from each WT group under the customized B-vitamin regimen (WT, WT-B-Vit (-), and WT-B-Vit (+)) showing central and peripheral retinal structural changes. (B,C) The graphical representations of retinal thickness quantification for both central and peripheral retina reveal significant alterations primarily in the RPE/choroid. B-vitamin deficiency caused increased choroidal thickness (suggestive of choroidal neovascularization) and reduced RPE thickness, both of which were restored by B-vitamin supplementation. (IPL/GCL, inner plexiform layer/ganglion cell layer, INL inner nuclear layer, OPL outer plexiform layer, ONL outer nuclear layer, IS inner segment, OS outer segment, RPE retinal pigment epithelium). * p < 0.05, n = 24.

Figure 5.

(A) Representative WB and quantitative analysis of retinal albumin levels in WT, WT-B-Vit (-), and WT-B-Vit (+). reveals a significant increase in albumin levels in mice fed B-vitamin deficient diet (WT-B-Vit (-)) compared to WT controls. This elevation was attenuated by B-vitamin supplementation in the WT-B-Vit (+) group. (B,C): WB analyses of the tight junction proteins, occludin (B) and ZO-1 (C), in retinal tissue show a significant reduction in occludin expression in the WT-B-Vit (-) group compared to the WT group. Similarly, the ZO-1 levels were also reduced. Both protein expressions were restored in the B-vitamin supplemented group (WT-B-Vit (+)), as indicated in the accompanying graphs of their densitometric quantifications. Densitometry values were normalized to β-actin. * p < 0.05, n = 6.

Figure 5.

(A) Representative WB and quantitative analysis of retinal albumin levels in WT, WT-B-Vit (-), and WT-B-Vit (+). reveals a significant increase in albumin levels in mice fed B-vitamin deficient diet (WT-B-Vit (-)) compared to WT controls. This elevation was attenuated by B-vitamin supplementation in the WT-B-Vit (+) group. (B,C): WB analyses of the tight junction proteins, occludin (B) and ZO-1 (C), in retinal tissue show a significant reduction in occludin expression in the WT-B-Vit (-) group compared to the WT group. Similarly, the ZO-1 levels were also reduced. Both protein expressions were restored in the B-vitamin supplemented group (WT-B-Vit (+)), as indicated in the accompanying graphs of their densitometric quantifications. Densitometry values were normalized to β-actin. * p < 0.05, n = 6.

Figure 6.

Serum Hcy level in in both genetic and nutritional elevated Hcy models. (A) The graph shows serum Hcy levels in WT, cbs+/-, and WT mice fed a B-vitamin deficient diet (WT-B-Vit (-)). The nutritional model, WT-B-Vit (-) produces a significant elevation in Hcy comparable to that observed in the genetic model cbs+/- compared to the WT. (B) Graph displays the serum vitamin B12 levels measured in WT, cbs+/-, and WT-B-Vit (-) groups, with a significant decrease in WT-B-Vit (-) as compared to WT control and the genetic model of elevated Hcy, cbs+/-. C. Simplified Schematic of the Hcy metabolic pathway illustrating the role of vitamins B6, B9, and B12 in the remethylation and transsulfuration cycles. * p < 0.05, n = 6.

Figure 6.

Serum Hcy level in in both genetic and nutritional elevated Hcy models. (A) The graph shows serum Hcy levels in WT, cbs+/-, and WT mice fed a B-vitamin deficient diet (WT-B-Vit (-)). The nutritional model, WT-B-Vit (-) produces a significant elevation in Hcy comparable to that observed in the genetic model cbs+/- compared to the WT. (B) Graph displays the serum vitamin B12 levels measured in WT, cbs+/-, and WT-B-Vit (-) groups, with a significant decrease in WT-B-Vit (-) as compared to WT control and the genetic model of elevated Hcy, cbs+/-. C. Simplified Schematic of the Hcy metabolic pathway illustrating the role of vitamins B6, B9, and B12 in the remethylation and transsulfuration cycles. * p < 0.05, n = 6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).