Submitted:

06 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

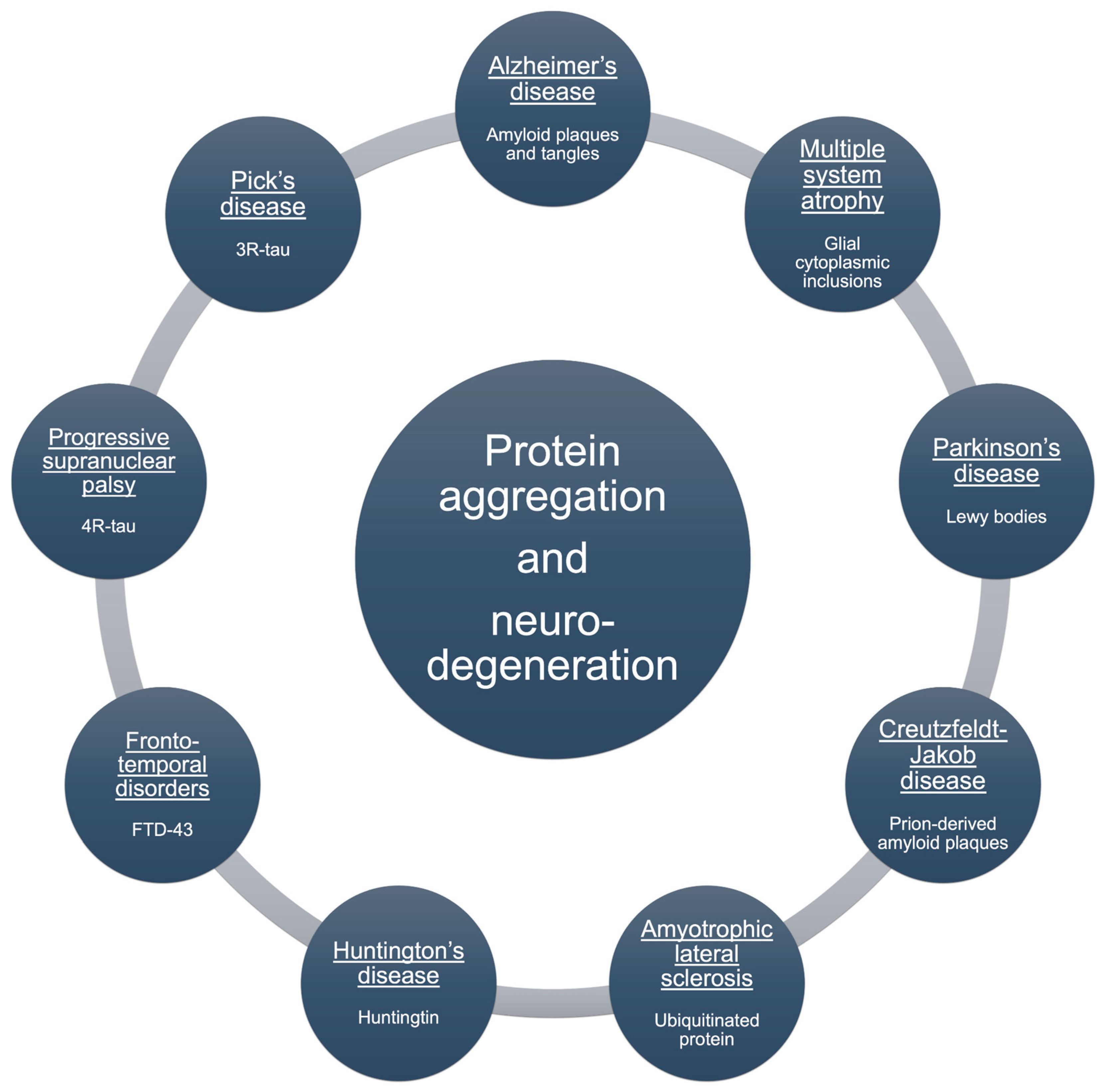

1. Introduction

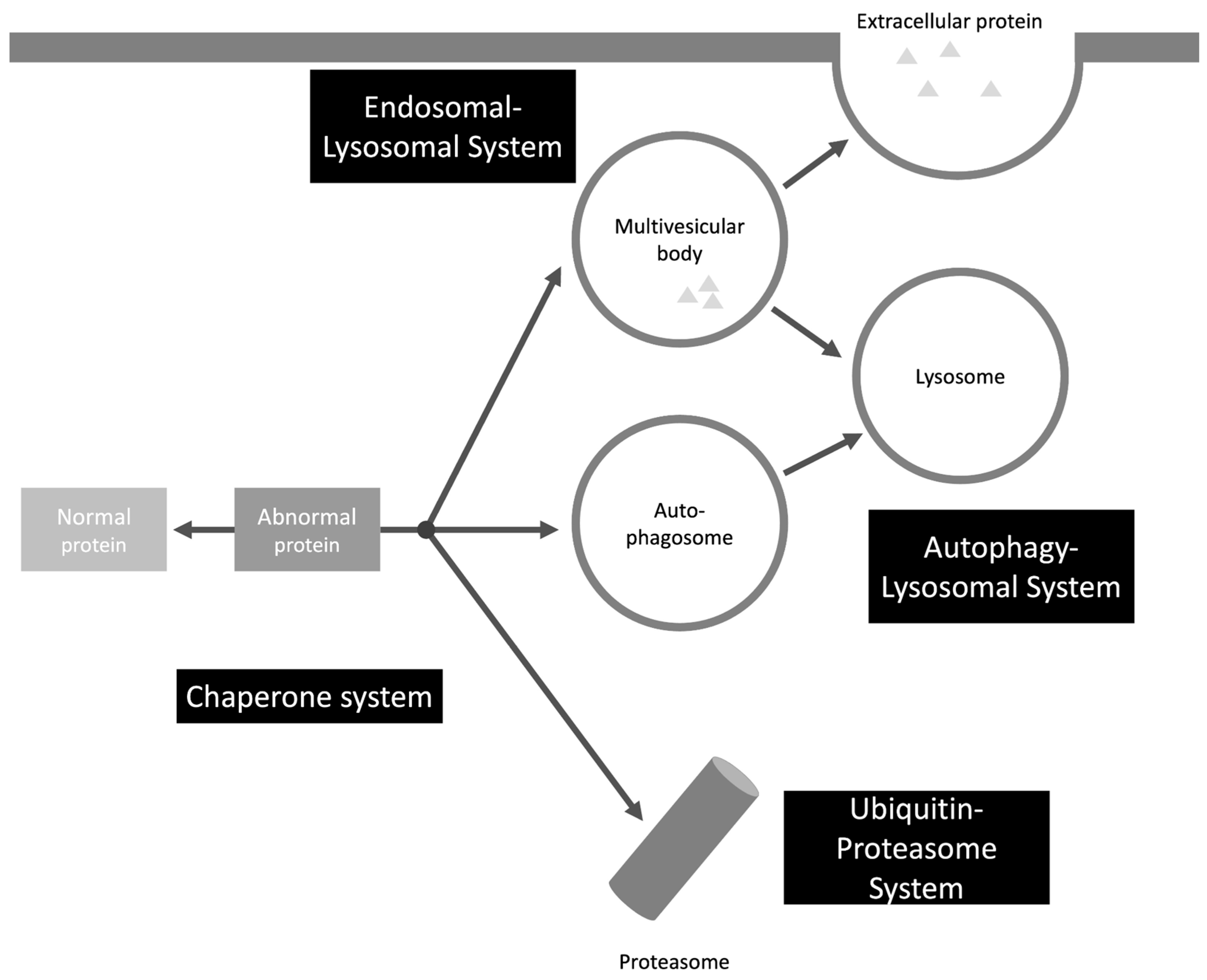

2. Protein Clearance Mechanisms – Intraneuronal

2.1. UPS

2.2. Endosomal-Lysosomal System

2.3. Autophagy-Lysosomal System

2.4. Chaperone System

2.5. Additional Selective Clearance Pathways

3. Protein Clearance Mechanisms - Extraneuronal

3.1. Glymphatic System

3.2. Glial Cells

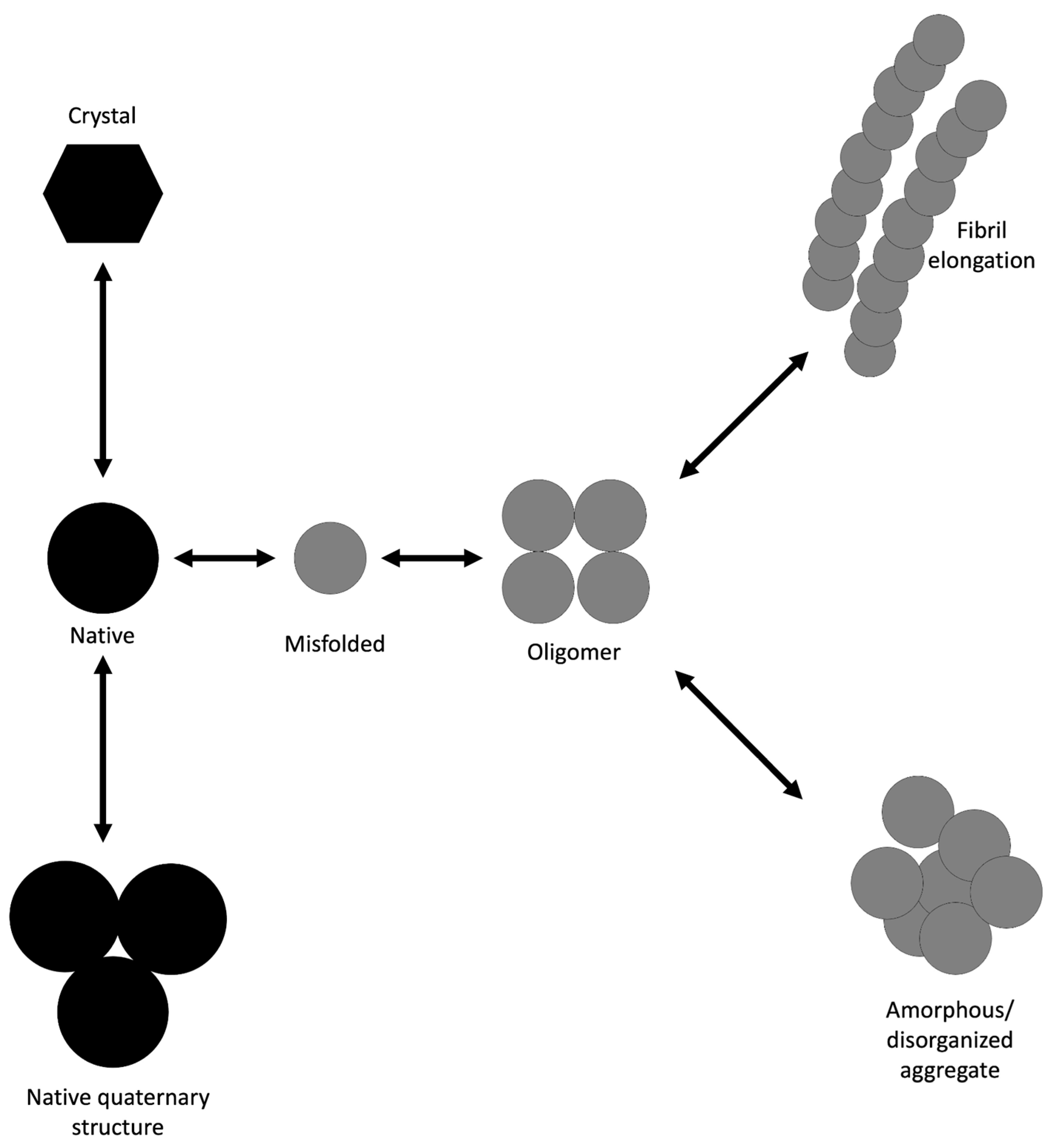

4. Protein Aggregation

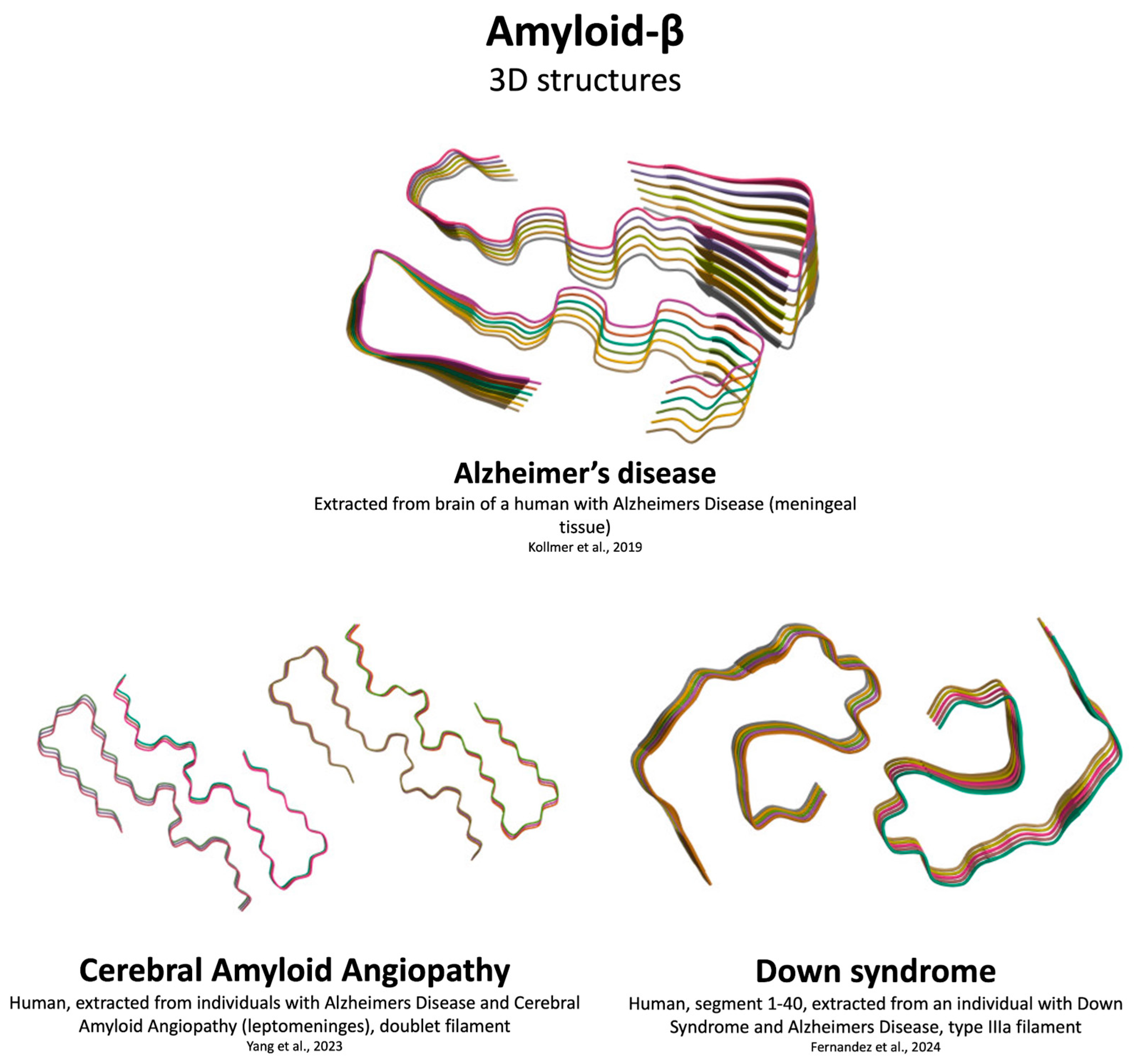

4.1. Aβ Aggregation

4.2. αSyn Aggregation

4.3. Tau Aggregation

4.4. TDP-43 Aggregation

5. Protein-Based Self-Propagation Mechanism

6. Impact of Aging on Protein Aggregation

7. Strategies to Limit Protein Aggregation and Spread

7.1. Immunization

7.2. Natural Compounds

7.3. Small Molecules

7.4. Peptides

7.5. PTMs

7.6. Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras

7.7. Autophagy-Targeting Chimeras

7.8. Activators of Autophagy

7.9. Activators of the Proteasome

8. Contradictory Points

8.1. Neurodegeneration Without Misfolded Protein Aggregates

8.2. LBs: Beyond αSyn Aggregates

8.3. Mixed Pathologies

8.4. Rethinking Protein Aggregation

9. Future Studies

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| Aβ | Amyloid-beta |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| HD | Huntington’s disease |

| LB | Lewy bodies |

| LLPS | Liquid-liquid phase separation |

| MSA | Multiple system atrophy |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PTMs | Post-translational modifications |

| UPS | Ubiquitin-proteasome system |

| αSyn | α-Synuclein |

References

- Soto, C. Unfolding the Role of Protein Misfolding in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003, 4, 49–60. [CrossRef]

- Balch, W.E.; Morimoto, R.I.; Dillin, A.; Kelly, J.W. Adapting Proteostasis for Disease Intervention. Science 2008, 319, 916–919. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Chandran, A.; Raza, F.; Ungureanu, I.-M.; Hilcenko, C.; Stott, K.; Bright, N.A.; Morone, N.; Warren, A.J.; Lautenschläger, J. VAMP2 Regulates Phase Separation of α-Synuclein. Nat Cell Biol 2024, 26, 1296–1308. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sakunthala, A.; Gadhe, L.; Poudyal, M.; Sawner, A.S.; Kadu, P.; Maji, S.K. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of α-Synuclein: A New Mechanistic Insight for α-Synuclein Aggregation Associated with Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. J Mol Biol 2023, 435, 167713. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ortega, E.D.; Wilkaniec, A.; Adamczyk, A. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation and Conformational Strains of α-Synuclein: Implications for Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci 2024, 17, 1494218. [CrossRef]

- Sternke-Hoffmann, R.; Sun, X.; Menzel, A.; Pinto, M.D.S.; Venclovaitė, U.; Wördehoff, M.; Hoyer, W.; Zheng, W.; Luo, J. Phase Separation and Aggregation of α-Synuclein Diverge at Different Salt Conditions. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-S.; Chao, Y.-W.; Liu, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-S.; Chao, H.-W. Dysregulated Proteostasis Network in Neuronal Diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1075215. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, W. Ubiquitination in the Nervous System: From Molecular Mechanisms to Disease Implications. Mol Neurobiol 2025, 62, 15365–15389. [CrossRef]

- Church, T.R.; Margolis, S.S. Mechanisms of Ubiquitin-Independent Proteasomal Degradation and Their Roles in Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1531797. [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.S.; Moreira-de-Carvalho, G.O.A.; Fortes, F.S.A.; de Souza, A.L.F. Autophagy Pathways, Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Scopus Review. Brazilian Journal of Biological Sciences 2025, 12, e149–e149. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carralero, E.; Quinet, G.; Freire, R. ATXN3: A Multifunctional Protein Involved in the Polyglutamine Disease Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3. Expert Rev Mol Med 2024, 26, e19. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Lin, M.-M.; Wang, Y. The Emerging Roles of E3 Ligases and DUBs in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 60, 247–263. [CrossRef]

- Ronnebaum, S.M.; Patterson, C.; Schisler, J.C. Emerging Evidence of Coding Mutations in the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Associated with Cerebellar Ataxias. Hum Genome Var 2014, 1, 14018. [CrossRef]

- Husain, N.; Yuan, Q.; Yen, Y.-C.; Pletnikova, O.; Sally, D.Q.; Worley, P.; Bichler, Z.; Shawn Je, H. TRIAD3/RNF216 Mutations Associated with Gordon Holmes Syndrome Lead to Synaptic and Cognitive Impairments via Arc Misregulation. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 281–292. [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Medico-Salsench, E.; Nikoncuk, A.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Lanko, K.; Kühn, N.A.; van der Linde, H.C.; Lor-Zade, S.; Albuainain, F.; Shi, Y.; et al. AMFR Dysfunction Causes Autosomal Recessive Spastic Paraplegia in Human That Is Amenable to Statin Treatment in a Preclinical Model. Acta Neuropathol 2023, 146, 353–368. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Begum, M.Y.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, J.; Nagraik, R.; Panda, S.P.; Abomughaid, M.M.; Lakhanpal, S.; D, A.; Osmani, R.A.M.; et al. The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in Brain Disorders: Pathogenic Pathways, Post-Translational Tweaks, and Therapeutic Frontiers. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2025, 20, 105. [CrossRef]

- Le Guerroué, F.; Youle, R.J. Ubiquitin Signaling in Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Autophagy and Proteasome Perspective. Cell Death Differ 2021, 28, 439–454. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Biogenesis, Secretion, and Intercellular Interactions of Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2014, 30, 255–289. [CrossRef]

- Vietri, M.; Radulovic, M.; Stenmark, H. The Many Functions of ESCRTs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 25–42. [CrossRef]

- Udayar, V.; Chen, Y.; Sidransky, E.; Jagasia, R. Lysosomal Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration: Emerging Concepts and Methods. Trends Neurosci 2022, 45, 184–199. [CrossRef]

- Nan, H.; Ichinose, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Koh, K.; Ishiura, H.; Mitsui, J.; Mizukami, H.; Morimoto, M.; Hamada, S.; Ohtsuka, T.; et al. UBAP1 Mutations Cause Juvenile-Onset Hereditary Spastic Paraplegias (SPG80) and Impair UBAP1 Targeting to Endosomes. J Hum Genet 2019, 64, 1055–1065. [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, E.K.; Follett, J.; Trinh, J.; Barodia, S.K.; Real, R.; Liu, Z.; Grant-Peters, M.; Fox, J.D.; Appel-Cresswell, S.; Stoessl, A.J.; et al. RAB32 Ser71Arg in Autosomal Dominant Parkinson’s Disease: Linkage, Association, and Functional Analyses. Lancet Neurol 2024, 23, 603–614. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Yan, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yang, J.; Xi, Y.; Zhong, Z. Decoding the Cellular Trafficking of Prion-like Proteins in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurosci Bull 2024, 40, 241–254. [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.-W.; Frost, A.; Moss, F.R. 3rd Organelle Homeostasis Requires ESCRTs. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2025, 93, 102481. [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Mechanisms of Autophagy-Lysosome Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2024, 25, 926–946. [CrossRef]

- Steel, D.; Zech, M.; Zhao, C.; Barwick, K.E.S.; Burke, D.; Demailly, D.; Kumar, K.R.; Zorzi, G.; Nardocci, N.; Kaiyrzhanov, R.; et al. Loss-of-Function Variants in HOPS Complex Genes VPS16 and VPS41 Cause Early Onset Dystonia Associated with Lysosomal Abnormalities. Ann Neurol 2020, 88, 867–877. [CrossRef]

- Monfrini, E.; Zech, M.; Steel, D.; Kurian, M.A.; Winkelmann, J.; Di Fonzo, A. HOPS-Associated Neurological Disorders (HOPSANDs): Linking Endolysosomal Dysfunction to the Pathogenesis of Dystonia. Brain 2021, 144, 2610–2615. [CrossRef]

- Vicinanza, M.; Korolchuk, V.I.; Ashkenazi, A.; Puri, C.; Menzies, F.M.; Clarke, J.H.; Rubinsztein, D.C. PI(5)P Regulates Autophagosome Biogenesis. Mol Cell 2015, 57, 219–234. [CrossRef]

- Boffey, H.K.; Rooney, T.P.C.; Willems, H.M.G.; Edwards, S.; Green, C.; Howard, T.; Ogg, D.; Romero, T.; Scott, D.E.; Winpenny, D.; et al. Development of Selective Phosphatidylinositol 5-Phosphate 4-Kinase γ Inhibitors with a Non-ATP-Competitive, Allosteric Binding Mode. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 3359–3370. [CrossRef]

- Xiaojie Zhang; Huan Zhang; Jie Dong; Huaibin Cai; Weidong Le Advances in Autophagy for Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis and Treatment. Ageing and Neurodegenerative Diseases 2025, 5, 6. [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A. The Role of Autophagy in Neurodegenerative Disease. Nat Med 2013, 19, 983–997. [CrossRef]

- Moreau, K.; Fleming, A.; Imarisio, S.; Lopez Ramirez, A.; Mercer, J.L.; Jimenez-Sanchez, M.; Bento, C.F.; Puri, C.; Zavodszky, E.; Siddiqi, F.; et al. PICALM Modulates Autophagy Activity and Tau Accumulation. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 4998. [CrossRef]

- van der Beek, J.; Klumperman, J. Trafficking to the Lysosome: HOPS Paves the Way. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2025, 94, 102515. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Han, S.; Ju, S.; Ranbhise, J.S.; Ha, J.; Yeo, S.G.; Kim, S.S.; Kang, I. Hsp70: A Multifunctional Chaperone in Maintaining Proteostasis and Its Implications in Human Disease. Cells 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Niu, T.; Chatterjee, A.; He, P.; Hou, G. Heat Shock Protein 90: Biological Functions, Diseases, and Therapeutic Targets. MedComm (2020) 2024, 5, e470. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shah, O.P.; Sharma, L.; Gulati, M.; Behl, T.; Khalid, A.; Mohan, S.; Najmi, A.; Zoghebi, K. Molecular Chaperones as Therapeutic Target: Hallmark of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Mol Neurobiol 2024, 61, 4750–4767. [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Wan, Y.; Zhao, R.; Pan, S.; Luan, M.; Wu, W.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wei, L.; et al. Intronic VNTRs Downregulate Expression of HSF1 and Confer Genetic Risk of Essential Tremor. Brain 2025, 148, 4098–4111. [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.K.; Jeganathan, F.; Bictash, M.; Chen, H.-J. Identification of Novel Small Molecule Chaperone Activators for Neurodegenerative Disease Treatment. Biomed Pharmacother 2025, 187, 118049. [CrossRef]

- Rai, P. Conformational Dynamics of Hsp90 and Hsp70 Chaperones in Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases: Insights from the Drosophila Model. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy 2024, 90, 628–637. [CrossRef]

- Pasala, C.; Digwal, C.S.; Sharma, S.; Wang, S.; Bubula, A.; Chiosis, G. Epichaperomes: Redefining Chaperone Biology and Therapeutic Strategies in Complex Diseases. RSC Chem Biol 2025, 6, 678–698. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Joshi, S.; Kalidindi, T.; Digwal, C.S.; Panchal, P.; Lee, S.-G.; Zanzonico, P.; Pillarsetty, N.; Chiosis, G. Unraveling the Mechanism of Epichaperome Modulation by Zelavespib: Biochemical Insights on Target Occupancy and Extended Residence Time at the Site of Action. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Bay, S.; Digwal, C.S.; Rodilla Martín, A.M.; Sharma, S.; Stanisavljevic, A.; Rodina, A.; Attaran, A.; Roychowdhury, T.; Parikh, K.; Toth, E.; et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Click Chemical Probes for Single-Cell Resolution Detection of Epichaperomes in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Inda, M.C.; Joshi, S.; Wang, T.; Bolaender, A.; Gandu, S.; Koren Iii, J.; Che, A.Y.; Taldone, T.; Yan, P.; Sun, W.; et al. The Epichaperome Is a Mediator of Toxic Hippocampal Stress and Leads to Protein Connectivity-Based Dysfunction. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 319. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filimonenko, M.; Isakson, P.; Finley, K.D.; Anderson, M.; Jeong, H.; Melia, T.J.; Bartlett, B.J.; Myers, K.M.; Birkeland, H.C.G.; Lamark, T.; et al. The Selective Macroautophagic Degradation of Aggregated Proteins Requires the PI3P-Binding Protein Alfy. Mol Cell 2010, 38, 265–279. [CrossRef]

- Lystad, A.H.; Ichimura, Y.; Takagi, K.; Yang, Y.; Pankiv, S.; Kanegae, Y.; Kageyama, S.; Suzuki, M.; Saito, I.; Mizushima, T.; et al. Structural Determinants in GABARAP Required for the Selective Binding and Recruitment of ALFY to LC3B-Positive Structures. EMBO Rep 2014, 15, 557–565. [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wei, W.; Duan, W.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Bi, Y.; Li, C. Autophagy-Linked FYVE Protein (Alfy) Promotes Autophagic Removal of Misfolded Proteins Involved in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2015, 51, 249–263. [CrossRef]

- Dragich, J.M.; Kuwajima, T.; Hirose-Ikeda, M.; Yoon, M.S.; Eenjes, E.; Bosco, J.R.; Fox, L.M.; Lystad, A.H.; Oo, T.F.; Yarygina, O.; et al. Autophagy Linked FYVE (Alfy/WDFY3) Is Required for Establishing Neuronal Connectivity in the Mammalian Brain. Elife 2016, 5, e14810. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isakson, P.; Holland, P.; Simonsen, A. The Role of ALFY in Selective Autophagy. Cell Death Differ 2013, 20, 12–20. [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, A.; Birkeland, H.C.G.; Gillooly, D.J.; Mizushima, N.; Kuma, A.; Yoshimori, T.; Slagsvold, T.; Brech, A.; Stenmark, H. Alfy, a Novel FYVE-Domain-Containing Protein Associated with Protein Granules and Autophagic Membranes. J Cell Sci 2004, 117, 4239–4251. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyadevara, S.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Gao, Y.; Yu, L.-R.; Alla, R.; Shmookler Reis, R. Proteins in Aggregates Functionally Impact Multiple Neurodegenerative Disease Models by Forming Proteasome-Blocking Complexes. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 35–48. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, M.; Ayyadevara, S.; Shmookler Reis, R.J. Structural Insights into Pro-Aggregation Effects of C. Elegans CRAM-1 and Its Human Ortholog SERF2. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 14891. [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4, 147ra111. [CrossRef]

- Ciurea, A.V.; Mohan, A.G.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Costin, H.P.; Saceleanu, V.M. The Brain’s Glymphatic System: Drawing New Perspectives in Neuroscience. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hablitz, L.M.; Plá, V.; Giannetto, M.; Vinitsky, H.S.; Stæger, F.F.; Metcalfe, T.; Nguyen, R.; Benrais, A.; Nedergaard, M. Circadian Control of Brain Glymphatic and Lymphatic Fluid Flow. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringstad, G.; Valnes, L.M.; Dale, A.M.; Pripp, A.H.; Vatnehol, S.-A.S.; Emblem, K.E.; Mardal, K.-A.; Eide, P.K. Brain-Wide Glymphatic Enhancement and Clearance in Humans Assessed with MRI. JCI Insight 2018, 3, 121537. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.M.; Llewellyn, S.K.; Bury, S.E.; Wang, J.; Wells, J.A.; Gegg, M.E.; Verona, G.; Lythgoe, M.F.; Harrison, I.F. The Influence of the Glymphatic System on α-Synuclein Propagation: The Role of Aquaporin-4. Brain 2025, awaf255. [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Zhang, Y.; Seegobin, S.P.; Pruvost, M.; Wang, Q.; Purtell, K.; Zhang, B.; Yue, Z. Microglia Clear Neuron-Released α-Synuclein via Selective Autophagy and Prevent Neurodegeneration. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1386. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.-K.; Tao, K.-X.; Wang, X.-B.; Yao, X.-Y.; Pang, M.-Z.; Liu, J.-Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, C.-F. Role of α-Synuclein in Microglia: Autophagy and Phagocytosis Balance Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. Inflamm Res 2023, 72, 443–462. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Q.; Wang, M.; Yin, Y.; Tang, Y. The Specific Mechanism of TREM2 Regulation of Synaptic Clearance in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 845897. [CrossRef]

- Brash-Arias, D.; García, L.I.; Pérez-Estudillo, C.A.; Rojas-Durán, F.; Aranda-Abreu, G.E.; Herrera-Covarrubias, D.; Chi-Castañeda, D. The Role of Astrocytes and Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease: A Review. NeuroSci 2024, 5, 71–86. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Shi, M.; Stewart, T.; Fernagut, P.-O.; Huang, Y.; Tian, C.; Dehay, B.; Atik, A.; Yang, D.; De Giorgi, F.; et al. Reduced Oligodendrocyte Exosome Secretion in Multiple System Atrophy Involves SNARE Dysfunction. Brain 2020, 143, 1780–1797. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, G.; Tsai, L.-H. Mechanisms of DNA Damage-Mediated Neurotoxicity in Neurodegenerative Disease. EMBO Rep 2022, 23, e54217. [CrossRef]

- Saramowicz, K.; Siwecka, N.; Galita, G.; Kucharska-Lusina, A.; Rozpędek-Kamińska, W.; Majsterek, I. Alpha-Synuclein Contribution to Neuronal and Glial Damage in Parkinson’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25. [CrossRef]

- Louros, N.; Schymkowitz, J.; Rousseau, F. Mechanisms and Pathology of Protein Misfolding and Aggregation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023, 24, 912–933. [CrossRef]

- Lurette, O.; Martín-Jiménez, R.; Khan, M.; Sheta, R.; Jean, S.; Schofield, M.; Teixeira, M.; Rodriguez-Aller, R.; Perron, I.; Oueslati, A.; et al. Aggregation of Alpha-Synuclein Disrupts Mitochondrial Metabolism and Induce Mitophagy via Cardiolipin Externalization. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 729. [CrossRef]

- Chand, J.; Fanai, H.L.; Antony, A.; Subramanian, G. Neurotoxicity by Hypoxia an Intermediate Between Alpha-Synuclein and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics 2024, 15, 253–263. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.-Y. Protein Transmission in Neurodegenerative Disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2020, 16, 199–212. [CrossRef]

- Alexandersen, C.G.; Brennan, G.S.; Brynildsen, J.K.; Henderson, M.X.; Iturria-Medina, Y.; Bassett, D.S. Network Models of Neurodegeneration: Bridging Neuronal Dynamics and Disease Progression. arXiv preprint 2025. arXiv:2509.05151.

- Jung, R.; Lechler, M.C.; Fernandez-Villegas, A.; Chung, C.W.; Jones, H.C.; Choi, Y.H.; Thompson, M.A.; Rödelsperger, C.; Röseler, W.; Kaminski Schierle, G.S.; et al. A Safety Mechanism Enables Tissue-Specific Resistance to Protein Aggregation during Aging in C. Elegans. PLoS Biol 2023, 21, e3002284. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Gui, X.; Feng, S.; Reif, B. Aggregation Mechanisms and Molecular Structures of Amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s Disease. Chemistry 2024, 30, e202400277. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Nussinov, R.; Ma, B. Coupling of the Non-Amyloid-Component (NAC) Domain and the KTK(E/Q)GV Repeats Stabilize the α-Synuclein Fibrils. Eur J Med Chem 2016, 121, 841–850. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Godínez, F.J.; Vázquez-García, E.R.; Trujillo-Villagrán, M.I.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Palomero-Rivero, M.; Hernández-González, O.; Pérez-Eugenio, F.; Collazo-Navarrete, O.; Arias-Carrión, O.; Guerra-Crespo, M. α-Synuclein and Tau: Interactions, Cross-Seeding, and the Redefinition of Synucleinopathies as Complex Proteinopathies. Front Neurosci 2025, 19, 1570553. [CrossRef]

- Koszła, O.; Sołek, P. Misfolding and Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Protein Quality Control Machinery as Potential Therapeutic Clearance Pathways. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 421. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremer, L.; Schölzel, D.; Schenk, C.; Reinartz, E.; Labahn, J.; Ravelli, R.B.G.; Tusche, M.; Lopez-Iglesias, C.; Hoyer, W.; Heise, H.; et al. Fibril Structure of Amyloid-β(1-42) by Cryo-Electron Microscopy. Science 2017, 358, 116–119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollmer, M.; Close, W.; Funk, L.; Rasmussen, J.; Bsoul, A.; Schierhorn, A.; Schmidt, M.; Sigurdson, C.J.; Jucker, M.; Fändrich, M. Cryo-EM Structure and Polymorphism of Aβ Amyloid Fibrils Purified from Alzheimer’s Brain Tissue. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4760. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Murzin, A.G.; Peak-Chew, S.; Franco, C.; Garringer, H.J.; Newell, K.L.; Ghetti, B.; Goedert, M.; Scheres, S.H.W. Cryo-EM Structures of Aβ40 Filaments from the Leptomeninges of Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease and Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2023, 11, 191. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, A.; Hoq, M.R.; Hallinan, G.I.; Li, D.; Bharath, S.R.; Vago, F.S.; Zhang, X.; Ozcan, K.A.; Newell, K.L.; Garringer, H.J.; et al. Cryo-EM Structures of Amyloid-β and Tau Filaments in Down Syndrome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2024, 31, 903–909. [CrossRef]

- Sehnal, D.; Bittrich, S.; Deshpande, M.; Svobodová, R.; Berka, K.; Bazgier, V.; Velankar, S.; Burley, S.K.; Koča, J.; Rose, A.S. Mol* Viewer: Modern Web App for 3D Visualization and Analysis of Large Biomolecular Structures. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, W431–W437. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Arseni, D.; Zhang, W.; Huang, M.; Lövestam, S.; Schweighauser, M.; Kotecha, A.; Murzin, A.G.; Peak-Chew, S.Y.; Macdonald, J.; et al. Cryo-EM Structures of Amyloid-β 42 Filaments from Human Brains. Science 2022, 375, 167–172. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Yau, W.-M.; Louis, J.M.; Tycko, R. Structures of Brain-Derived 42-Residue Amyloid-β Fibril Polymorphs with Unusual Molecular Conformations and Intermolecular Interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2218831120. [CrossRef]

- Meisl, G.; Yang, X.; Frohm, B.; Knowles, T.P.J.; Linse, S. Quantitative Analysis of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors in the Aggregation Mechanism of Alzheimer-Associated Aβ-Peptide. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 18728. [CrossRef]

- Weiffert, T.; Meisl, G.; Curk, S.; Cukalevski, R.; Šarić, A.; Knowles, T.P.; Linse, S. Influence of Denaturants on Amyloid Β42 Aggregation Kinetics. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2022, 16, 943355. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Viles, J.H. pH Dependence of Amyloid-β Fibril Assembly Kinetics: Unravelling the Microscopic Molecular Processes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2022, 61, e202210675. [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Goswami, S.; Das, D. Cross β Amyloid Assemblies as Complex Catalytic Machinery. Chem Commun (Camb) 2021, 57, 7597–7609. [CrossRef]

- Demuro, A.; Mina, E.; Kayed, R.; Milton, S.C.; Parker, I.; Glabe, C.G. Calcium Dysregulation and Membrane Disruption as a Ubiquitous Neurotoxic Mechanism of Soluble Amyloid Oligomers. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 17294–17300. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Bukhteeva, I.; Potsiluienko, Y.; Leonenko, Z. Amyloid β 1-42 Can Form Ion Channels as Small as Gramicidin in Model Lipid Membranes. Membranes (Basel) 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Ciudad, S.; Puig, E.; Botzanowski, T.; Meigooni, M.; Arango, A.S.; Do, J.; Mayzel, M.; Bayoumi, M.; Chaignepain, S.; Maglia, G.; et al. Aβ(1-42) Tetramer and Octamer Structures Reveal Edge Conductivity Pores as a Mechanism for Membrane Damage. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3014. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Sarangi, N.K.; Keyes, T.E. Role of Phosphatidylserine in Amyloid-Beta Oligomerization at Asymmetric Phospholipid Bilayers. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2023, 25, 7648–7661. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, K.M.; Cleveland, E.M.; Pennington, A.; Fuccello, S.; Brown, A.M. The Influence of POPC as a Coaggregate in Amyloid-β Oligomer Formation. ACS Chem Neurosci 2025, 16, 3886–3898. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadamangudi, S.; Marcatti, M.; Zhang, W.-R.; Fracassi, A.; Kayed, R.; Limon, A.; Taglialatela, G. Amyloid-β Oligomers Increase the Binding and Internalization of Tau Oligomers in Human Synapses. Acta Neuropathol 2024, 149, 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Lin, Y.; Nam, E.; Kang, D.M.; Lim, S.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lim, M.H. Interactions with Tau’s Microtubule-Binding Repeats Modulate Amyloid-β Aggregation and Toxicity. Nat Chem Biol 2025, 21, 1709–1718. [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, F.; Standke, H.G.; Artikis, E.; Schwartz, C.L.; Hansen, B.; Li, K.; Hughson, A.G.; Manca, M.; Thomas, O.R.; Raymond, G.J.; et al. Cryo-EM Structure of Anchorless RML Prion Reveals Variations in Shared Motifs between Distinct Strains. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4005. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.K.; Meisl, G.; Andrzejewska, E.A.; Krainer, G.; Dear, A.J.; Castellana-Cruz, M.; Turi, S.; Edu, I.A.; Vivacqua, G.; Jacquat, R.P.B.; et al. α-Synuclein Oligomers Form by Secondary Nucleation. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 7083. [CrossRef]

- Röntgen, A.; Toprakcioglu, Z.; Morris, O.M.; Vendruscolo, M. Amyloid-β Modulates the Phase Separation and Aggregation of α-Synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025, 122, e2501987122. [CrossRef]

- Hervas, R.; Rau, M.J.; Park, Y.; Zhang, W.; Murzin, A.G.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.J.; Scheres, S.H.W.; Si, K. Cryo-EM Structure of a Neuronal Functional Amyloid Implicated in Memory Persistence in Drosophila. Science 2020, 367, 1230–1234. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Schmidt, M.L.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Jakes, R.; Goedert, M. Alpha-Synuclein in Lewy Bodies. Nature 1997, 388, 839–840. [CrossRef]

- Arias-Carrión, O.; Guerra-Crespo, M.; Padilla-Godínez, F.J.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Manjarrez, E. α-Synuclein Pathology in Synucleinopathies: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Challenges. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, S.; Gadhe, L.; Bera, R.; Sawner, A.S.; Maji, S.K. Structural and Functional Insights into α-Synuclein Fibril Polymorphism. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yu, W.; Tao, Y.; Xia, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Tang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, F.; et al. Conformational Change of α-Synuclein Fibrils in Cerebrospinal Fluid from Different Clinical Phases of Parkinson’s Disease. Structure 2023, 31, 78-87.e5. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ge, P.; Murray, K.A.; Sheth, P.; Zhang, M.; Nair, G.; Sawaya, M.R.; Shin, W.S.; Boyer, D.R.; Ye, S.; et al. Cryo-EM of Full-Length α-Synuclein Reveals Fibril Polymorphs with a Common Structural Kernel. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3609. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, N.L.; Candido, F.; Tse, E.; Melo, A.A.; Prusiner, S.B.; Mordes, D.A.; Southworth, D.R.; Paras, N.A.; Merz, G.E. Cryo-EM Structure of a Novel α-Synuclein Filament Subtype from Multiple System Atrophy. FEBS Lett 2025, 599, 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Sokratian, A.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, E.; Viverette, E.; Dillard, L.; Yuan, Y.; Li, J.Y.; Matarangas, A.; Bouvette, J.; Borgnia, M. Structural and Functional Landscape of α-Synuclein Fibril Conformations Amplified from Cerebrospinal Fluid. BioRxiv 2022, 2022–07.

- Guerrero-Ferreira, R.; Taylor, N.M.; Mona, D.; Ringler, P.; Lauer, M.E.; Riek, R.; Britschgi, M.; Stahlberg, H. Cryo-EM Structure of Alpha-Synuclein Fibrils. Elife 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hou, S.; Zhao, K.; Long, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Su, X.-D.; Li, D.; Liu, C. Cryo-EM Structure of Full-Length α-Synuclein Amyloid Fibril with Parkinson’s Disease Familial A53T Mutation. Cell Res 2020, 30, 360–362. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.C.; Pierson, J.A.; Borcik, C.G.; Rienstra, C.M.; Wright, E.R. High-Resolution Cryo-EM Structure Determination of a-Synuclein-A Prototypical Amyloid Fibril. Bio Protoc 2025, 15, e5171. [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wei, M.; Xu, F.; Niu, Z. Aggregation and Phase Separation of α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease. Chem Commun (Camb) 2024, 60, 6581–6590. [CrossRef]

- Röntgen, A.; Toprakcioglu, Z.; Tomkins, J.E.; Vendruscolo, M. Modulation of α-Synuclein in Vitro Aggregation Kinetics by Its Alternative Splice Isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2313465121. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makasewicz, K.; Linse, S.; Sparr, E. Interplay of α-Synuclein with Lipid Membranes: Cooperative Adsorption, Membrane Remodeling and Coaggregation. JACS Au 2024, 4, 1250–1262. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dear, A.J.; Teng, X.; Ball, S.R.; Lewin, J.; Horne, R.I.; Clow, D.; Stevenson, A.; Harper, N.; Yahya, K.; Yang, X.; et al. Molecular Mechanism of α-Synuclein Aggregation on Lipid Membranes Revealed. Chem Sci 2024, 15, 7229–7242. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvagnion, C.; Barclay, A.; Makasewicz, K.; Marlet, F.R.; Moulin, M.; Devos, J.M.; Linse, S.; Martel, A.; Porcar, L.; Sparr, E.; et al. Structural Characterisation of α-Synuclein-Membrane Interactions and the Resulting Aggregation Using Small Angle Scattering. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2024, 26, 10998–11013. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbuti, P.A.; Guardia-Laguarta, C.; Yun, T.; Chatila, Z.K.; Flowers, X.; Wong, C.; Santos, B.F.R.; Larsen, S.B.; Lotti, J.S.; Hattori, N.; et al. The Role of Alpha-Synuclein in Synucleinopathy: Impact on Lipid Regulation at Mitochondria-ER Membranes. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2025, 11, 103. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, R.; Pan, B.; Xu, H.; Olufemi, M.F.; Gathagan, R.J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, W.; et al. Post-Translational Modifications of Soluble α-Synuclein Regulate the Amplification of Pathological α-Synuclein. Nat Neurosci 2023, 26, 213–225. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasili, E.; König, A.; Al-Azzani, M.; Bosbach, C.; Gatzemeier, L.M.; Thom, S.; Chegão, A.; Miranda, H.V.; Steinem, C.; Erskine, D.; et al. Glycation of Alpha-Synuclein Enhances Aggregation and Neuroinflammatory Responses. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2025, 11, 307. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldensperger, T.; Preissler, M.; Becker, C.F.W. Non-Enzymatic Posttranslational Protein Modifications in Protein Aggregation and Neurodegenerative Diseases. RSC Chem Biol 2025, 6, 129–149. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamage, K.; Wang, B.; Hard, E.R.; Van, T.; Galesic, A.; Phillips, G.R.; Pratt, M.; Lapidus, L.J. Post-Translational Modification of α-Synuclein Modifies Monomer Dynamics and Aggregation Kinetics. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–05.

- Yoo, J.M.; Lin, Y.; Heo, Y.; Lee, Y.-H. Polymorphism in Alpha-Synuclein Oligomers and Its Implications in Toxicity under Disease Conditions. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9, 959425. [CrossRef]

- Du, X.-Y.; Xie, X.-X.; Liu, R.-T. The Role of α-Synuclein Oligomers in Parkinson’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Dolui, S.; Dhabal, S.; Kundu, S.; Das, L.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Maiti, N.C. Structure Specific Neuro-Toxicity of α-Synuclein Oligomer. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 253, 126683. [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, J.A.; Halliday, G.M.; Dieriks, B.V. Neuronal α-Synuclein Toxicity Is the Key Driver of Neurodegeneration in Multiple System Atrophy. Brain 2025, 148, 2306–2319. [CrossRef]

- Zampar, S.; Di Gregorio, S.E.; Grimmer, G.; Watts, J.C.; Ingelsson, M. “Prion-like” Seeding and Propagation of Oligomeric Protein Assemblies in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front Neurosci 2024, 18, 1436262. [CrossRef]

- Khedmatgozar, C.R.; Holec, S.A.M.; Woerman, A.L. The Role of α-Synuclein Prion Strains in Parkinson’s Disease and Multiple System Atrophy. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1011920. [CrossRef]

- Tullo, S.; Park, J.S.; Rahayel, S.; Gallino, D.; Park, M.; Mar, K.; Zheng, Y.-Q.; del Cid-Pellitero, E.; Fon, E.A.; Luo, W. In Vivo and in Silico Alpha-Synuclein Propagation Dynamics: The Role of Genotype, Epicentre, and Connectivity. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–07. [CrossRef]

- Wojewska, M.J.; Otero-Jimenez, M.; Guijarro-Nuez, J.; Alegre-Abarrategui, J. Beyond Strains: Molecular Diversity in Alpha-Synuclein at the Center of Disease Heterogeneity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Yamakado, H.; Uemura, N.; Taguchi, T.; Ueda, J. The Gut-Brain Axis Based on α-Synuclein Propagation-Clinical, Neuropathological, and Experimental Evidence. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, P.J.; Civitelli, L.; Hu, M.T. The Gut-Brain Axis in Early Parkinson’s Disease: From Prodrome to Prevention. J Neurol 2025, 272, 413. [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Caprara, A.L. A Narrative Review on Biochemical Markers and Emerging Treatments in Prodromal Synucleinopathies. Clinics and Practice 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; An, K.; Wang, D.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Min, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Xue, Z.; Mao, Z. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Aggregates Alpha-Synuclein Accumulation and Neuroinflammation via GPR43-NLRP3 Signaling Pathway in a Model Parkinson’s Disease. Mol Neurobiol 2025, 62, 6612–6625. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahbub, N.U.; Islam, M.M.; Hong, S.-T.; Chung, H.-J. Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiota and Its Effect on α-Synuclein and Prion Protein Misfolding: Consequences for Neurodegeneration. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14, 1348279. [CrossRef]

- von Bergen, M.; Barghorn, S.; Biernat, J.; Mandelkow, E.-M.; Mandelkow, E. Tau Aggregation Is Driven by a Transition from Random Coil to Beta Sheet Structure. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005, 1739, 158–166. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeganathan, S.; von Bergen, M.; Mandelkow, E.-M.; Mandelkow, E. The Natively Unfolded Character of Tau and Its Aggregation to Alzheimer-like Paired Helical Filaments. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 10526–10539. [CrossRef]

- Barghorn, S.; Zheng-Fischhöfer, Q.; Ackmann, M.; Biernat, J.; von Bergen, M.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E. Structure, Microtubule Interactions, and Paired Helical Filament Aggregation by Tau Mutants of Frontotemporal Dementias. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 11714–11721. [CrossRef]

- Schweers, O.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Biernat, J.; Mandelkow, E. Oxidation of Cysteine-322 in the Repeat Domain of Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau Controls the in Vitro Assembly of Paired Helical Filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 8463–8467. [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.W.; Hwo, S.Y.; Kirschner, M.W. Physical and Chemical Properties of Purified Tau Factor and the Role of Tau in Microtubule Assembly. J Mol Biol 1977, 116, 227–247. [CrossRef]

- Mukrasch, M.D.; Bibow, S.; Korukottu, J.; Jeganathan, S.; Biernat, J.; Griesinger, C.; Mandelkow, E.; Zweckstetter, M. Structural Polymorphism of 441-Residue Tau at Single Residue Resolution. PLoS Biol 2009, 7, e34. [CrossRef]

- Hernández Pérez, F.; Ferrer, I.; Pérez Martínez, M.M.; Zabala, J.C.; del Rio, J.A.; Ávila, J. Tau Aggregation. Neuroscience 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, A.W.P.; Falcon, B.; He, S.; Murzin, A.G.; Murshudov, G.; Garringer, H.J.; Crowther, R.A.; Ghetti, B.; Goedert, M.; Scheres, S.H.W. Cryo-EM Structures of Tau Filaments from Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2017, 547, 185–190. [CrossRef]

- Jeganathan, S.; von Bergen, M.; Brutlach, H.; Steinhoff, H.-J.; Mandelkow, E. Global Hairpin Folding of Tau in Solution. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 2283–2293. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T.; Cheng, J.-T.; Liang, L.-C.; Ko, C.-Y.; Lo, Y.-K.; Lu, P.-J. The Binding and Phosphorylation of Thr231 Is Critical for Tau’s Hyperphosphorylation and Functional Regulation by Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3beta. J Neurochem 2007, 103, 802–813. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibille, N.; Huvent, I.; Fauquant, C.; Verdegem, D.; Amniai, L.; Leroy, A.; Wieruszeski, J.-M.; Lippens, G.; Landrieu, I. Structural Characterization by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance of the Impact of Phosphorylation in the Proline-Rich Region of the Disordered Tau Protein. Proteins 2012, 80, 454–462. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Murzin, A.G.; Falcon, B.; Epstein, A.; Machin, J.; Tempest, P.; Newell, K.L.; Vidal, R.; Garringer, H.J.; Sahara, N.; et al. Cryo-EM Structures of Tau Filaments from Alzheimer’s Disease with PET Ligand APN-1607. Acta Neuropathol 2021, 141, 697–708. [CrossRef]

- Hallinan, G.I.; Hoq, M.R.; Ghosh, M.; Vago, F.S.; Fernandez, A.; Garringer, H.J.; Vidal, R.; Jiang, W.; Ghetti, B. Structure of Tau Filaments in Prion Protein Amyloidoses. Acta Neuropathol 2021, 142, 227–241. [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Lövestam, S.; Murzin, A.; Peak-Chew, S.; Franco, C.; Bogdani, M.; Latimer, C.; Murrell, J.; Cullinane, P.; Jaunmuktane, Z. Tau Filaments with the Alzheimer Fold in Cases withMAPTmutations V337M and R406W. 2024.

- Scheres, S.H.; Zhang, W.; Falcon, B.; Goedert, M. Cryo-EM Structures of Tau Filaments. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2020, 64, 17–25. [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M.; Jakes, R.; Spillantini, M.G.; Hasegawa, M.; Smith, M.J.; Crowther, R.A. Assembly of Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau into Alzheimer-like Filaments Induced by Sulphated Glycosaminoglycans. Nature 1996, 383, 550–553. [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M.; Spillantini, M.G. Propagation of Tau Aggregates. Mol Brain 2017, 10, 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, S.; Sahara, N.; Saito, Y.; Murayama, S.; Ikai, A.; Takashima, A. Increased Levels of Granular Tau Oligomers: An Early Sign of Brain Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurosci Res 2006, 54, 197–201. [CrossRef]

- Kampers, T.; Friedhoff, P.; Biernat, J.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E. RNA Stimulates Aggregation of Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau into Alzheimer-like Paired Helical Filaments. FEBS Lett 1996, 399, 344–349. [CrossRef]

- von Bergen, M.; Friedhoff, P.; Biernat, J.; Heberle, J.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E. Assembly of Tau Protein into Alzheimer Paired Helical Filaments Depends on a Local Sequence Motif ((306)VQIVYK(311)) Forming Beta Structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 5129–5134. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.J.; Guo, J.L.; Hurtado, D.E.; Kwong, L.K.; Mills, I.P.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.Y. The Acetylation of Tau Inhibits Its Function and Promotes Pathological Tau Aggregation. Nat Commun 2011, 2, 252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöll, M.; Vrillon, A.; Ikeuchi, T.; Quevenco, F.C.; Iaccarino, L.; Vasileva-Metodiev, S.Z.; Burnham, S.C.; Hendrix, J.; Epelbaum, S.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Cutting through the Noise: A Narrative Review of Alzheimer’s Disease Plasma Biomarkers for Routine Clinical Use. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2025, 12, 100056. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, D.F.; Smirnov, D.S.; Coughlin, D.G.; Peng, I.; Standke, H.G.; Kim, Y.; Pizzo, D.P.; Unapanta, A.; Andreasson, T.; Hiniker, A.; et al. Early Alzheimer’s Disease with Frequent Neuritic Plaques Harbors Neocortical Tau Seeds Distinct from Primary Age-Related Tauopathy. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 1851. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulic, B.; Pickhardt, M.; Mandelkow, E.-M.; Mandelkow, E. Tau Protein and Tau Aggregation Inhibitors. Neuropharmacology 2010, 59, 276–289. [CrossRef]

- Pickhardt, M.; Larbig, G.; Khlistunova, I.; Coksezen, A.; Meyer, B.; Mandelkow, E.-M.; Schmidt, B.; Mandelkow, E. Phenylthiazolyl-Hydrazide and Its Derivatives Are Potent Inhibitors of Tau Aggregation and Toxicity in Vitro and in Cells. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 10016–10023. [CrossRef]

- Berrocal, M.; Caballero-Bermejo, M.; Gutierrez-Merino, C.; Mata, A.M. Methylene Blue Blocks and Reverses the Inhibitory Effect of Tau on PMCA Function. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Lovchykova, A.; Akiyama, T.; Rayner, S.L.; Maheswari Jawahar, V.; Liu, C.; Sianto, O.; Guo, C.; Calliari, A.; Prudencio, M. TDP-43 Nuclear Loss in FTD/ALS Causes Widespread Alternative Polyadenylation Changes. Nature Neuroscience 2025, 1–10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongrácová, E.; Buratti, E.; Romano, M. Prion-like Spreading of Disease in TDP-43 Proteinopathies. Brain Sciences 2024, 14, 1132. [CrossRef]

- Arseni, D.; Hasegawa, M.; Murzin, A.G.; Kametani, F.; Arai, M.; Yoshida, M.; Ryskeldi-Falcon, B. Structure of Pathological TDP-43 Filaments from ALS with FTLD. Nature 2022, 601, 139–143. [CrossRef]

- Guenther, E.L.; Ge, P.; Trinh, H.; Sawaya, M.R.; Cascio, D.; Boyer, D.R.; Gonen, T.; Zhou, Z.H.; Eisenberg, D.S. Atomic-Level Evidence for Packing and Positional Amyloid Polymorphism by Segment from TDP-43 RRM2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2018, 25, 311–319. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arseni, D.; Chen, R.; Murzin, A.G.; Peak-Chew, S.Y.; Garringer, H.J.; Newell, K.L.; Kametani, F.; Robinson, A.C.; Vidal, R.; Ghetti, B.; et al. TDP-43 Forms Amyloid Filaments with a Distinct Fold in Type A FTLD-TDP. Nature 2023, 620, 898–903. [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, J.; Lends, A.; Berbon, M.; Bilal, M.; El Mammeri, N.; Bertoni, M.; Saad, A.; Morvan, E.; Grélard, A.; Lecomte, S.; et al. Structural Polymorphism of the Low-Complexity C-Terminal Domain of TDP-43 Amyloid Aggregates Revealed by Solid-State NMR. Front Mol Biosci 2023, 10, 1148302. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.S.; Sharpe, P.C.; Singh, Y.; Fairlie, D.P. Amyloid Peptides and Proteins in Review. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 2007, 159, 1–77. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiang, J.; Gong, H.; Yu, T.; Gao, M.; Huang, Y. The Regulation of TDP-43 Structure and Phase Transitions: A Review. Protein J 2025, 44, 113–132. [CrossRef]

- Pirie, E.; Oh, C.-K.; Zhang, X.; Han, X.; Cieplak, P.; Scott, H.R.; Deal, A.K.; Ghatak, S.; Martinez, F.J.; Yeo, G.W.; et al. S-Nitrosylated TDP-43 Triggers Aggregation, Cell-to-Cell Spread, and Neurotoxicity in hiPSCs and in Vivo Models of ALS/FTD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.P.-W.; Lee, C.-C.; He, R.-Y.; Huang, A.-C.; Huang, J.-R.; Chan, J.C.C.; Huang, J.J.-T. Amyloidogenic Oligomers Derived from TDP-43 LCD Promote the Condensation and Phosphorylation of TDP-43. Chem Sci 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mosna, S.; Dormann, D. TDP-43 Phosphorylation: Pathological Modification or Protective Factor Antagonizing TDP-43 Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases? Bioessays 2025, e70084. [CrossRef]

- Kellett, E.A.; Bademosi, A.T.; Walker, A.K. Molecular Mechanisms and Consequences of TDP-43 Phosphorylation in Neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener 2025, 20, 53. [CrossRef]

- Verde, E.M.; Antoniani, F.; Mediani, L.; Secco, V.; Crotti, S.; Ferrara, M.C.; Vinet, J.; Sergeeva, A.; Yan, X.; Hoege, C.; et al. SUMO2/3 Conjugation of TDP-43 Protects against Aggregation. Sci Adv 2025, 11, eadq2475. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C.; Rocha-Rangel, P.; Desai, R.; Quadri, Z.; Lui, H.; Hunt Jr, J.B.; Liang, H.; Rogers, C.; Nash, K.; Tsoi, P.S. Citrullination of TDP-43 Is a Key Post-Translation Modification Associated with Structural and Functional Changes and Progressive Pathology in TDP-43 Mouse Models and Human Proteinopathies. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–02. [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.; Lee, S.; Jeon, Y.-M.; Kim, S.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, H.-J. The Role of TDP-43 Propagation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Integrating Insights from Clinical and Experimental Studies. Experimental & molecular medicine 2020, 52, 1652–1662.

- Mamede, L.D.; Hu, M.; Titus, A.R.; Vaquer-Alicea, J.; French, R.L.; Diamond, M.I.; Miller, T.M.; Ayala, Y.M. TDP-43 Aggregate Seeding Impairs Autoregulation and Causes TDP-43 Dysfunction. 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lépine, S.; Nauleau-Javaudin, A.; Deneault, E.; Chen, C.X.-Q.; Abdian, N.; Franco-Flores, A.K.; Haghi, G.; Castellanos-Montiel, M.J.; Maussion, G.; Chaineau, M.; et al. Homozygous ALS-Linked Mutations in TARDBP/TDP-43 Lead to Hypoactivity and Synaptic Abnormalities in Human iPSC-Derived Motor Neurons. iScience 2024, 27, 109166. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Qiang, Y.; Shan, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Song, M.; Zhao, X.; Song, F. Aberrant Mitochondrial Aggregation of TDP-43 Activated Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response and Contributed to Recovery of Acetaminophen Induced Acute Liver Injury. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2024, 13, tfae008. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Wyant, C.E.; George, H.E.; Morgan, S.E.; Rangachari, V. Prion-like C-Terminal Domain of TDP-43 and α-Synuclein Interact Synergistically to Generate Neurotoxic Hybrid Fibrils. J Mol Biol 2021, 433, 166953. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prusiner, S.B.; Scott, M.R.; DeArmond, S.J.; Cohen, F.E. Prion Protein Biology. Cell 1998, 93, 337–348. [CrossRef]

- Schweighauser, M.; Shi, Y.; Tarutani, A.; Kametani, F.; Murzin, A.G.; Ghetti, B.; Matsubara, T.; Tomita, T.; Ando, T.; Hasegawa, K.; et al. Structures of α-Synuclein Filaments from Multiple System Atrophy. Nature 2020, 585, 464–469. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitton Rissardo, J.; McGarry, A.; Shi, Y.; Fornari Caprara, A.L.; Kannarkat, G.T. Alpha-Synuclein Neurobiology in Parkinson’s Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Its Role, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Brain Sciences 2025, 15, 1260. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Schekman, R.W. Intercellular Transmission of Alpha-Synuclein. Front Mol Neurosci 2024, 17, 1470171. [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.; Gonçalves, N.P.; Vaegter, C.B.; Jensen, P.H.; Ferreira, N. The Prion-Like Spreading of Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease: Update on Models and Hypotheses. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Del Tredici, K.; Rüb, U.; de Vos, R.A.I.; Jansen Steur, E.N.H.; Braak, E. Staging of Brain Pathology Related to Sporadic Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003, 24, 197–211. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.; Candelise, N.; Canaslan, S.; Altmeppen, H.C.; Matschke, J.; Glatzel, M.; Younas, N.; Zafar, S.; Hermann, P.; Zerr, I. α-Synuclein Conformers Reveal Link to Clinical Heterogeneity of α-Synucleinopathies. Transl Neurodegener 2023, 12, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.; So, R.W.L.; Lau, H.H.C.; Sang, J.C.; Ruiz-Riquelme, A.; Fleck, S.C.; Stuart, E.; Menon, S.; Visanji, N.P.; Meisl, G.; et al. α-Synuclein Strains Target Distinct Brain Regions and Cell Types. Nat Neurosci 2020, 23, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Holec, S.A.M.; Khedmatgozar, C.R.; Schure, S.J.; Pham, T.; Woerman, A.L. A-Synuclein Prion Strains Differentially Adapt after Passage in Mice. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1012746. [CrossRef]

- Okuzumi, A.; Hatano, T.; Matsumoto, G.; Nojiri, S.; Ueno, S.-I.; Imamichi-Tatano, Y.; Kimura, H.; Kakuta, S.; Kondo, A.; Fukuhara, T.; et al. Propagative α-Synuclein Seeds as Serum Biomarkers for Synucleinopathies. Nat Med 2023, 29, 1448–1455. [CrossRef]

- Bsoul, R.; Simonsen, A.H.; Frederiksen, K.S.; Svenstrup, K.; Bech, S.; Salvesen, L.; Hejl, A.-M.; Rossi, M.; Parchi, P.; Lund, E.L.; et al. Seeding Amplification Assay with Universal Control Fluid: Standardized Detection of α-Synucleinopathies. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0326568. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Fornari Caprara, A.L. Alpha-Synuclein Seed Amplification Assays in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Clin Pract 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Voicu, V.; Toader, C.; Șerban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V. Systemic Neurodegeneration and Brain Aging: Multi-Omics Disintegration, Proteostatic Collapse, and Network Failure Across the CNS. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Song, D.-Y.; Li, J.-Y. Revisiting the Advance of Age-Dependent α-Synuclein Propagation and Aggregation. Ageing and Neurodegenerative Diseases 2025, 5, N-A. [CrossRef]

- Yaribash, S.; Mohammadi, K.; Sani, M.A. Alpha-Synuclein Pathophysiology in Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Review Focusing on Molecular Mechanisms and Treatment Advances in Parkinson’s Disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2025, 45, 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.F.; Brignull, H.R.; Weyers, J.J.; Morimoto, R.I. The Threshold for Polyglutamine-Expansion Protein Aggregation and Cellular Toxicity Is Dynamic and Influenced by Aging in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 10417–10422. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamazaki, J.; Murata, S. Relationships between Protein Degradation, Cellular Senescence, and Organismal Aging. J Biochem 2024, 175, 473–480. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Carosi, J.M.; Dang, L.; Sargeant, T.J. Autophagy Does Not Always Decline with Ageing. Nat Cell Biol 2025, 27, 712–715. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrancx, C.; Annaert, W. Lysosome Repair Fails in Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat Cell Biol 2025, 27, 553–555. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fan, Y.; Ahmadpoor, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.A.; Zhu, W.; Lin, H. Targeting Lysosomal Quality Control as a Therapeutic Strategy against Aging and Diseases. Med Res Rev 2024, 44, 2472–2509. [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, K.; Jiao, B.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lou, M.; Bai, R. Age- and Time-of-Day Dependence of Glymphatic Function in the Human Brain Measured via Two Diffusion MRI Methods. Front Aging Neurosci 2023, 15, 1173221. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zheng, W.; Zhuang, Z.; Liao, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Lin, D.; Wu, X.; et al. The Aging of Glymphatic System in Human Brain and Its Correlation with Brain Charts and Neuropsychological Functioning. Cereb Cortex 2023, 33, 7896–7903. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, A.; Zhu, Y.D.; Albuhwailah, B.; Maillard, P.; DeCarli, C.; Fan, A.P. Multimodal MRI Insights into Glymphatic Clearance and Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity in Healthy Aging. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–11. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berge, N.; Ferreira, N.; Mikkelsen, T.W.; Alstrup, A.K.O.; Tamgüney, G.; Karlsson, P.; Terkelsen, A.J.; Nyengaard, J.R.; Jensen, P.H.; Borghammer, P. Ageing Promotes Pathological Alpha-Synuclein Propagation and Autonomic Dysfunction in Wild-Type Rats. Brain 2021, 144, 1853–1868. [CrossRef]

- Stoker, T.B.; Torsney, K.M.; Barker, R.A. Emerging Treatment Approaches for Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurosci 2018, 12, 693. [CrossRef]

- Henriquez, G.; Narayan, M. Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregation with Immunotherapy: A Promising Therapeutic Approach for Parkinson’s Disease. Exploration of Neuroprotective Therapy 2023, 3, 207–234. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, G.; Taylor, K.I.; Anzures-Cabrera, J.; Marchesi, M.; Simuni, T.; Marek, K.; Postuma, R.B.; Pavese, N.; Stocchi, F.; Azulay, J.-P.; et al. Trial of Prasinezumab in Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 421–432. [CrossRef]

- Lang Anthony E.; Siderowf Andrew D.; Macklin Eric A.; Poewe Werner; Brooks David J.; Fernandez Hubert H.; Rascol Olivier; Giladi Nir; Stocchi Fabrizio; Tanner Caroline M.; et al. Trial of Cinpanemab in Early Parkinson’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387, 408–420. [CrossRef]

- Shering, C.; Pomfret, M.; kubiak, R.; Pouliquen, I.; Yin, W.; Simen, A.; Ratti, E.; Perkinton, M.; Tan, K.; Chessell, I. Reducing α-Synuclein in Human CSF; an Evaluation of Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of MEDI1341, an α-Synuclein-Specific Antibody, in Healthy Volunteers and Parkinson’s Disease Patients (P1-11.007). Neurology 2023, 100, 2469. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, J.; Ratti, E.; Khudyakov, P.; Yin, W.; Zicha, S.; Golonzhka, O.; Kangarloo, T.; Harel, B.; Goodman, N.; Magueur, E.; et al. Study Design of TAK-341-2001: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of TAK-341 in Subjects With Multiple System Atrophy (P9-9.003). Neurology 2023, 100, 0247. [CrossRef]

- Buur, L.; Wiedemann, J.; Larsen, F.; Ben Alaya-Fourati, F.; Kallunki, P.; Ditlevsen, D.K.; Sørensen, M.H.; Meulien, D. Randomized Phase I Trial of the α-Synuclein Antibody Lu AF82422. Mov Disord 2024, 39, 936–944. [CrossRef]

- Boström, E.; Bachhav, S.S.; Xiong, H.; Zadikoff, C.; Li, Q.; Cohen, E.; Dreher, I.; Torrång, A.; Osswald, G.; Moge, M.; et al. Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Single Doses of Exidavnemab (BAN0805), an Anti-α-Synuclein Antibody, in Healthy Western, Caucasian, Japanese, and Han Chinese Adults. J Clin Pharmacol 2024, 64, 1432–1442. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.T.; Chung, C.H.-Y.; Iba, M.; Zhang, B.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Luk, K.C.; Lee, V.M.Y. A-Synuclein Immunotherapy Blocks Uptake and Templated Propagation of Misfolded α-Synuclein and Neurodegeneration. Cell Rep 2014, 7, 2054–2065. [CrossRef]

- Butler, Y.R.; Liu, Y.; Kumbhar, R.; Zhao, P.; Gadhave, K.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Mao, X.; Wang, W. α-Synuclein Fibril-Specific Nanobody Reduces Prion-like α-Synuclein Spreading in Mice. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4060. [CrossRef]

- Eijsvogel, P.; Misra, P.; Concha-Marambio, L.; Boyd, J.D.; Ding, S.; Fedor, L.; Hsieh, Y.-T.; Sun, Y.S.; Vroom, M.M.; Farris, C.M.; et al. Target Engagement and Immunogenicity of an Active Immunotherapeutic Targeting Pathological α-Synuclein: A Phase 1 Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nature Medicine 2024, 30, 2631–2640. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meissner, W.G.; Traon, A.P.-L.; Foubert-Samier, A.; Galabova, G.; Galitzky, M.; Kutzelnigg, A.; Laurens, B.; Lührs, P.; Medori, R.; Péran, P.; et al. A Phase 1 Randomized Trial of Specific Active α-Synuclein Immunotherapies PD01A and PD03A in Multiple System Atrophy. Mov Disord 2020, 35, 1957–1965. [CrossRef]

- Björklund, A.; Mattsson, B. The AAV-α-Synuclein Model of Parkinson’s Disease: An Update. J Parkinsons Dis 2024, 14, 1077–1094. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, B.; Jin, X.; Cao, X. Targeting Protein Aggregates with Natural Products: An Optional Strategy for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Emani, L.S.; Rao, J.K.; Kumar Dasappa, J.; Pecchio, M.; Lakey-Beitia, J.; Rodriguez, H.; Cruz-Mora, J.; Narayan, P.; Anand, N.; Mullur, G.; et al. Studies on Curcumin-Glucoside in the Prevention of Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 2025, 9, 25424823251347260. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.; Subramanian, T.; Pagan, F.; Isaacson, S.; Gil, R.; Hauser, R.A.; Feldman, M.; Goldstein, M.; Kumar, R.; Truong, D.; et al. Oral ENT-01 Targets Enteric Neurons to Treat Constipation in Parkinson Disease : A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med 2022, 175, 1666–1674. [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.; Sing, N.; Melbourne, S.; Morgan, A.; Mariner, C.; Spillantini, M.G.; Wegrzynowicz, M.; Dalley, J.W.; Langer, S.; Ryazanov, S.; et al. Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of the Oligomer Modulator Anle138b with Exposure Levels Sufficient for Therapeutic Efficacy in a Murine Parkinson Model: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 1a Trial. EBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104021. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.K.; Clark, W.; Kosman, D.J. The Iron Chelator, PBT434, Modulates Transcellular Iron Trafficking in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0254794. [CrossRef]

- Mercier, J.; Bani, M.; Colson, A.-O.; Germani, M.; Lalla, M.; Plisson, C.; Huiban, M.; Searle, G.; Mathy, F.-X.; Nicholl, R.; et al. Evaluation and Application of a PET Tracer in Preclinical and Phase 1 Studies to Determine the Brain Biodistribution of Minzasolmin (UCB0599). Mol Imaging Biol 2024, 26, 310–321. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Díaz, S.; Pujols, J.; Vasili, E.; Pinheiro, F.; Santos, J.; Manglano-Artuñedo, Z.; Outeiro, T.F.; Ventura, S. The Small Aromatic Compound SynuClean-D Inhibits the Aggregation and Seeded Polymerization of Multiple α-Synuclein Strains. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, 101902. [CrossRef]

- Borah, P.; Mattaparthi, V.S. Investigation into the Interaction Sites of the K84s and K102s Peptides with α-Synuclein for Understanding the Anti-Aggregation Mechanism: An In Silico Study. Current Biotechnology 2023, 12, 103–117.

- Popova, B.; Wang, D.; Rajavel, A.; Dhamotharan, K.; Lázaro, D.F.; Gerke, J.; Uhrig, J.F.; Hoppert, M.; Outeiro, T.F.; Braus, G.H. Identification of Two Novel Peptides That Inhibit α-Synuclein Toxicity and Aggregation. Front Mol Neurosci 2021, 14, 659926. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikenoue, T.; Oono, M.; So, M.; Yamakado, H.; Arata, T.; Takahashi, R.; Kawata, Y.; Suga, H. A RaPID Macrocyclic Peptide That Inhibits the Formation of α-Synuclein Amyloid Fibrils. Chembiochem 2023, 24, e202300320. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemerovski-Glikman, M.; Rozentur-Shkop, E.; Richman, M.; Grupi, A.; Getler, A.; Cohen, H.Y.; Shaked, H.; Wallin, C.; Wärmländer, S.K.T.S.; Haas, E.; et al. Self-Assembled Cyclic d,l-α-Peptides as Generic Conformational Inhibitors of the α-Synuclein Aggregation and Toxicity: In Vitro and Mechanistic Studies. Chemistry 2016, 22, 14236–14246. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornung, S.; Vogl, D.P.; Naltsas, D.; Volta, B.D.; Ballmann, M.; Marcon, B.; Syed, M.M.K.; Wu, Y.; Spanopoulou, A.; Feederle, R.; et al. Multi-Targeting Macrocyclic Peptides as Nanomolar Inhibitors of Self- and Cross-Seeded Amyloid Self-Assembly of α-Synuclein. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2025, 64, e202422834. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.C.; Gorecki, A.M.; Pesce, S.R.; Bagda, V.; Anderton, R.S.; Meloni, B.P. Novel Poly-Arginine Peptide R18D Reduces α-Synuclein Aggregation and Uptake of α-Synuclein Seeds in Cortical Neurons. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Lim, D.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, S.J.; Kim, Y.-H.; Im, H. Beta-Sheet-Breaking Peptides Inhibit the Fibrillation of Human Alpha-Synuclein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009, 387, 682–687. [CrossRef]

- Horsley, J.R.; Jovcevski, B.; Pukala, T.L.; Abell, A.D. Designer D-Peptides Targeting the N-Terminal Region of α-Synuclein to Prevent Parkinsonian-Associated Fibrilization and Cytotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 2022, 1870, 140826. [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, S.C.C.; Aina, A.; Roman, A.Y.; Cashman, N.R.; Peng, X.; Plotkin, S.S. Optimizing Epitope Conformational Ensembles Using α-Synuclein Cyclic Peptide “Glycindel” Scaffolds: A Customized Immunogen Method for Generating Oligomer-Selective Antibodies for Parkinson’s Disease. ACS Chem Neurosci 2022, 13, 2261–2280. [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.G.; Meade, R.M.; White Stenner, L.L.; Mason, J.M. Peptide-Based Approaches to Directly Target Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease. Mol Neurodegener 2023, 18, 80. [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Ren, X.; Xue, F.; He, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J. Specific Knockdown of α-Synuclein by Peptide-Directed Proteasome Degradation Rescued Its Associated Neurotoxicity. Cell Chem Biol 2020, 27, 751-762.e4. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.W.; Fan, X.; Del Cid-Pellitero, E.; Liu, X.-X.; Zhou, L.; Dai, C.; Gibbs, E.; He, W.; Li, H.; Wu, X.; et al. Development of an α-Synuclein Knockdown Peptide and Evaluation of Its Efficacy in Parkinson’s Disease Models. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 232. [CrossRef]

- Rott, R.; Szargel, R.; Haskin, J.; Shani, V.; Shainskaya, A.; Manov, I.; Liani, E.; Avraham, E.; Engelender, S. Monoubiquitylation of Alpha-Synuclein by Seven in Absentia Homolog (SIAH) Promotes Its Aggregation in Dopaminergic Cells. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 3316–3328. [CrossRef]

- Rott, R.; Szargel, R.; Haskin, J.; Bandopadhyay, R.; Lees, A.J.; Shani, V.; Engelender, S. α-Synuclein Fate Is Determined by USP9X-Regulated Monoubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 18666–18671. [CrossRef]

- Rott, R.; Szargel, R.; Shani, V.; Hamza, H.; Savyon, M.; Abd Elghani, F.; Bandopadhyay, R.; Engelender, S. SUMOylation and Ubiquitination Reciprocally Regulate α-Synuclein Degradation and Pathological Aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 13176–13181. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelender, S.; Stefanis, L.; Oddo, S.; Bellucci, A. Can We Treat Neurodegenerative Proteinopathies by Enhancing Protein Degradation? Mov Disord 2022, 37, 1346–1359. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cui, S.; Rao, H. Targeted Degradation of α-Synuclein by Arginine-Based PROTACs. J Biol Chem 2025, 301, 110449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kargbo, R.B. PROTAC Compounds Targeting α-Synuclein Protein for Treating Neurogenerative Disorders: Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. ACS Med Chem Lett 2020, 11, 1086–1087. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Thakur, V.; Sardana, S.; Tiwari, V.; Sharma, D.; Kumar, A. Contemporary Trends in Targeted Protein Degradation for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Eur J Med Chem 2025, 300, 118110. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Sung, K.W.; Bae, E.-J.; Yoon, D.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.S.; Park, D.-H.; Park, D.Y.; Mun, S.R.; Kwon, S.C.; et al. Targeted Degradation of ⍺-Synuclein Aggregates in Parkinson’s Disease Using the AUTOTAC Technology. Mol Neurodegener 2023, 18, 41. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, D.; Sung, K.W.; Bae, E.-J.; Park, D.-H.; Suh, Y.H.; Kwon, Y.T. Targeted Degradation of SNCA/α-Synuclein Aggregates in Neurodegeneration Using the AUTOTAC Chemical Platform. Autophagy 2024, 20, 463–465. [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.H.; Kwon, Y.; Huh, Y.E.; Choi, H.J. Trehalose Ameliorates Prodromal Non-Motor Deficits and Aberrant Protein Accumulation in a Rotenone-Induced Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Arch Pharm Res 2022, 45, 417–432. [CrossRef]

- AlRasheed, H.A.; Bahaa, M.M.; Elmasry, T.A.; Elberri, E.I.; Kotkata, F.A.; El Sabaa, R.M.; Elmorsi, Y.M.; Kamel, M.M.; Negm, W.A.; Hamouda, A.O.; et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study of Metformin as an Adjunctive Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1497261. [CrossRef]

- Ping, F.; Jiang, N.; Li, Y. Association between Metformin and Neurodegenerative Diseases of Observational Studies: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yin, L.; Luo, Z.; Chen, X.; He, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, M.; Tian, F.; Luo, H. Effects and Potential Mechanisms of Rapamycin on MPTP-Induced Acute Parkinson’s Disease in Mice. Ann Palliat Med 2021, 10, 2889–2897. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttuso, T.J.; Russak, E.; De Blanco, M.T.; Ramanathan, M. Could High Lithium Levels in Tobacco Contribute to Reduced Risk of Parkinson’s Disease in Smokers? J Neurol Sci 2019, 397, 179–180. [CrossRef]

- Guttuso, T.J.; Shepherd, R.; Frick, L.; Feltri, M.L.; Frerichs, V.; Ramanathan, M.; Zivadinov, R.; Bergsland, N. Lithium’s Effects on Therapeutic Targets and MRI Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease: A Pilot Clinical Trial. IBRO Neurosci Rep 2023, 14, 429–434. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truedson, P.; Ott, M.; Lindmark, K.; Ström, M.; Maripuu, M.; Lundqvist, R.; Werneke, U. Effects of Toxic Lithium Levels on ECG-Findings from the LiSIE Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Khurana, V.; Lindquist, S. Modelling Neurodegeneration in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae: Why Cook with Baker’s Yeast? Nat Rev Neurosci 2010, 11, 436–449. [CrossRef]

- Sorrenti, V.; Benedetti, F.; Buriani, A.; Fortinguerra, S.; Caudullo, G.; Davinelli, S.; Zella, D.; Scapagnini, G. Immunomodulatory and Antiaging Mechanisms of Resveratrol, Rapamycin, and Metformin: Focus on mTOR and AMPK Signaling Networks. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desouky, M.A.; George, M.Y.; Michel, H.E.; Elsherbiny, D.A. Roflumilast Escalates α-Synuclein Aggregate Degradation in Rotenone-Induced Parkinson’s Disease in Rats: Modulation of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Chem Biol Interact 2023, 379, 110491. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shao, M.; Guo, B.; Li, C.; Lu, Y.; Yang, X.; ShengnanLi; Li, H.; Zhu, Q.; Zhong, H.; et al. Tetramethylpyrazine Analogue T-006 Promotes the Clearance of Alpha-Synuclein by Enhancing Proteasome Activity in Parkinson’s Disease Models. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 1225–1236. [CrossRef]

- Fiolek, T.J.; Keel, K.L.; Tepe, J.J. Fluspirilene Analogs Activate the 20S Proteasome and Overcome Proteasome Impairment by Intrinsically Disordered Protein Oligomers. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2021, 12, 1438–1448. [CrossRef]

- Staerz, S.D. Discovery and Design of Novel 20S Proteasome Activators for Targeted Protein Degradation and Their Evaluation in Neurodegeneration Models; Michigan State University, 2024; ISBN 979-8-3822-4002-2.

- Smirnov, D.S.; Galasko, D.; Hansen, L.A.; Edland, S.D.; Brewer, J.B.; Salmon, D.P. Trajectories of Cognitive Decline Differ in Hippocampal Sclerosis and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging 2019, 75, 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Leverenz, J.B.; Umar, I.; Wang, Q.; Montine, T.J.; McMillan, P.J.; Tsuang, D.W.; Jin, J.; Pan, C.; Shin, J.; Zhu, D.; et al. Proteomic Identification of Novel Proteins in Cortical Lewy Bodies. Brain Pathol 2007, 17, 139–145. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Liao, L.; Cheng, D.; Duong, D.M.; Gearing, M.; Lah, J.J.; Levey, A.I.; Peng, J. Proteomic Identification of Novel Proteins Associated with Lewy Bodies. Front Biosci 2008, 13, 3850–3856. [CrossRef]

- Licker, V.; Turck, N.; Kövari, E.; Burkhardt, K.; Côte, M.; Surini-Demiri, M.; Lobrinus, J.A.; Sanchez, J.-C.; Burkhard, P.R. Proteomic Analysis of Human Substantia Nigra Identifies Novel Candidates Involved in Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. Proteomics 2014, 14, 784–794. [CrossRef]

- Shahmoradian, S.H.; Lewis, A.J.; Genoud, C.; Hench, J.; Moors, T.E.; Navarro, P.P.; Castaño-Díez, D.; Schweighauser, G.; Graff-Meyer, A.; Goldie, K.N.; et al. Lewy Pathology in Parkinson’s Disease Consists of Crowded Organelles and Lipid Membranes. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22, 1099–1109. [CrossRef]

- Mahul-Mellier, A.-L.; Burtscher, J.; Maharjan, N.; Weerens, L.; Croisier, M.; Kuttler, F.; Leleu, M.; Knott, G.W.; Lashuel, H.A. The Process of Lewy Body Formation, Rather than Simply α-Synuclein Fibrillization, Is One of the Major Drivers of Neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 4971–4982. [CrossRef]

- Lau, V.Z.; Awogbindin, I.O.; Frenkel, D.; Whitehead, S.N.; Tremblay, M.-È. A Hypothesis Explaining Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Dementia with Lewy Bodies Overlap. Alzheimers Dement 2025, 21, e70363. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.L.; Lee, E.B.; Xie, S.X.; Rennert, L.; Suh, E.; Bredenberg, C.; Caswell, C.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Yan, N.; Yousef, A.; et al. Neurodegenerative Disease Concomitant Proteinopathies Are Prevalent, Age-Related and APOE4-Associated. Brain 2018, 141, 2181–2193. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, D.J.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Parkinson’s Disease Dementia: Convergence of α-Synuclein, Tau and Amyloid-β Pathologies. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 626–636. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, J.B.; Gopal, P.; Raible, K.; Irwin, D.J.; Brettschneider, J.; Sedor, S.; Waits, K.; Boluda, S.; Grossman, M.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; et al. Pathological α-Synuclein Distribution in Subjects with Coincident Alzheimer’s and Lewy Body Pathology. Acta Neuropathol 2016, 131, 393–409. [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.; Stefanis, L.; Attems, J. Clinical and Neuropathological Differences between Parkinson’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease Dementia and Dementia with Lewy Bodies - Current Issues and Future Directions. J Neurochem 2019, 150, 467–474. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fein, J.A.; Sokolow, S.; Miller, C.A.; Vinters, H.V.; Yang, F.; Cole, G.M.; Gylys, K.H. Co-Localization of Amyloid Beta and Tau Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Synaptosomes. Am J Pathol 2008, 172, 1683–1692. [CrossRef]

- Aksman, L.M.; Oxtoby, N.P.; Scelsi, M.A.; Wijeratne, P.A.; Young, A.L.; Alves, I.L.; Collij, L.E.; Vogel, J.W.; Barkhof, F.; Alexander, D.C.; et al. A Data-Driven Study of Alzheimer’s Disease Related Amyloid and Tau Pathology Progression. Brain 2023, 146, 4935–4948. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manca, M.; Standke, H.G.; Browne, D.F.; Huntley, M.L.; Thomas, O.R.; Orrú, C.D.; Hughson, A.G.; Kim, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tatsuoka, C.; et al. Tau Seeds Occur before Earliest Alzheimer’s Changes and Are Prevalent across Neurodegenerative Diseases. Acta Neuropathol 2023, 146, 31–50. [CrossRef]

- Lashuel, H.A. Rethinking Protein Aggregation and Drug Discovery in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Why We Need to Embrace Complexity? Curr Opin Chem Biol 2021, 64, 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Murzin, A.G.; Falcon, B.; Kotecha, A.; van Beers, M.; Tarutani, A.; Kametani, F.; Garringer, H.J.; et al. Structure-Based Classification of Tauopathies. Nature 2021, 598, 359–363. [CrossRef]

- Limorenko, G.; Lashuel, H.A. Revisiting the Grammar of Tau Aggregation and Pathology Formation: How New Insights from Brain Pathology Are Shaping How We Study and Target Tauopathies. Chem Soc Rev 2022, 51, 513–565. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcon, B.; Zhang, W.; Schweighauser, M.; Murzin, A.G.; Vidal, R.; Garringer, H.J.; Ghetti, B.; Scheres, S.H.W.; Goedert, M. Tau Filaments from Multiple Cases of Sporadic and Inherited Alzheimer’s Disease Adopt a Common Fold. Acta Neuropathol 2018, 136, 699–708. [CrossRef]

- So, R.W.L.; Watts, J.C. α-Synuclein Conformational Strains as Drivers of Phenotypic Heterogeneity in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J Mol Biol 2023, 435, 168011. [CrossRef]

- Lashuel, H.A.; Overk, C.R.; Oueslati, A.; Masliah, E. The Many Faces of α-Synuclein: From Structure and Toxicity to Therapeutic Target. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 38–48. [CrossRef]

- Kuzu, O.F.; Granerud, L.J.T.; Saatcioglu, F. Navigating the Landscape of Protein Folding and Proteostasis: From Molecular Chaperones to Therapeutic Innovations. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 358. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kametani, F.; Tahira, M.; Takao, M.; Matsubara, T.; Hasegawa, K.; Yoshida, M.; Saito, Y.; Murayama, S.; Hasegawa, M. Analysis and Comparison of Post-Translational Modifications of α-Synuclein Filaments in Multiple System Atrophy and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 22892. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Escudero, V.; Ruiz-Gabarre, D.; Gargini, R.; Pérez, M.; García, E.; Cuadros, R.; Hernández, I.H.; Cabrera, J.R.; García-Escudero, R.; Lucas, J.J. A New Non-Aggregative Splicing Isoform of Human Tau Is Decreased in Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Neuropathologica 2021, 142, 159–177. [CrossRef]

- Yefroyev, D.A.; Jin, S. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells for Treatment of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Aβ | αSyn | Tau | TDP-43 |

| Primary aggregation domain | Full-length (Aβ40/42), hydrophobic core (residues 17–21, 30–42) | NAC region (61–95) critical for fibrillization | Microtubule-binding repeats (R2, R3; VQIINK, VQIVYK motifs) | Low-complexity domain (LCD; residues 282–360) |

| Architecture | Canonical cross-β fibrils; cryo-EM shows S-shaped, ν-shaped polymorphs | Cross-β fibrils; multiple polymorphs (MSA vs PD) | Paired helical filaments (PHFs) and straight filaments; disease-specific folds | Amyloid-like but non-classical cross-β; short β-strands, spiral folds |

| Nucleation mechanism | Primary nucleation + secondary nucleation dominates oligomer formation | Primary nucleation; secondary nucleation accelerates oligomer growth | Heparin-induced nucleation in vitro; secondary nucleation less defined | LLPS precedes solidification; oligomeric seeds nucleate fibrils |

| Polymorphism | High; Aβ40 vs Aβ42 differ; multiple brain-derived folds | High; strain-specific folds linked to disease phenotype | High; AD vs PiD vs CBD folds differ by isoform composition (3R vs 4R) | Present; LCD truncations yield distinct fibril cores |

| Cellular localization | Extracellular plaques (parenchyma, vasculature) | Cytoplasmic inclusions (LBs, neurites) | Cytoplasmic neurofibrillary tangles; axonal threads | Cytoplasmic inclusions; nuclear clearance |

| PTMs influencing aggregation | N-terminal truncation, oxidation | Phosphorylation, nitration | Hyperphosphorylation, acetylation | Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, citrullination |

| Propagation | Prion-like seeding; extracellular spread | Prion-like; vesicle-mediated transmission | Prion-like; templated misfolding | Prion-like; LLPS-driven seeding and spread |

| Toxic species | Soluble oligomers (membrane pore formation) | Oligomers; disrupt vesicle trafficking | Oligomers; impair microtubule stability | Oligomers; RNA sequestration, splicing defects |

| Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid-beta; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; EM, electron microscopy; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; LCD, low-complexity domain; LLPS, liquid–liquid phase separation; MSA, multiple system atrophy; PHF, paired helical filament; PTM, post-translational modification; SSNMR, solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. | ||||

| Strategy | Mechanism of action | Representative agents | Current Status / Limitations |

| Passive Immunotherapy | Monoclonal antibodies bind aggregated αSyn to block propagation and promote clearance | Prasinezumab (C-terminal epitope), Cinpanemab (N-terminal epitope), MEDI1341/TAK-341, LuAF82422, Exidavemab | Phase II trials; limited efficacy, poor BBB penetration |

| Active Immunotherapy | Vaccines induce endogenous antibodies against aggregated αSyn | UB-312, PD01A, PD03A | Phase I–II; risk of neuroinflammation, variable immunogenicity |

| Small Molecule Aggregation Inhibitors | Block oligomerization or fibril elongation | Anle138b, NPT200-11, PBT434 | Phase I–II; off-target effects, CNS penetration issues |

| Natural Compounds | Polyphenols disrupt hydrophobic interactions and reduce oxidative stress | EGCG, Curcumin, Squalamine/ENT-01 | Preclinical/Phase II; poor bioavailability |

| Peptide-Based Inhibitors | Target NAC domain or fibril ends to prevent nucleation and elongation | K84s, TO2, TO5, macrocyclic peptides (BD1), poly-arginine peptides (R18D) | Preclinical; short half-life, BBB limitations |

| Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) | Recruit E3 ligases to ubiquitinate αSyn for proteasomal degradation | Arginine-based PROTACs | Preclinical; limited aggregate clearance, BBB penetration |

| Autophagy-Targeting Chimeras (AUTOTACs) | Redirect aggregates to autophagosomes for lysosomal degradation | ATC161 | Phase I; BBB penetration remains a challenge |

| Autophagy Activators | Enhance autophagic flux to clear aggregates | Trehalose, Metformin, Rapamycin, Lithium | Phase I–II; systemic toxicity, non-selective degradation |

| Proteasome Activators | Stimulate proteasomal activity to degrade misfolded proteins | Roflumilast, modified tetramethylpyrazine | Preclinical; insufficient potency, poor CNS penetration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).