Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

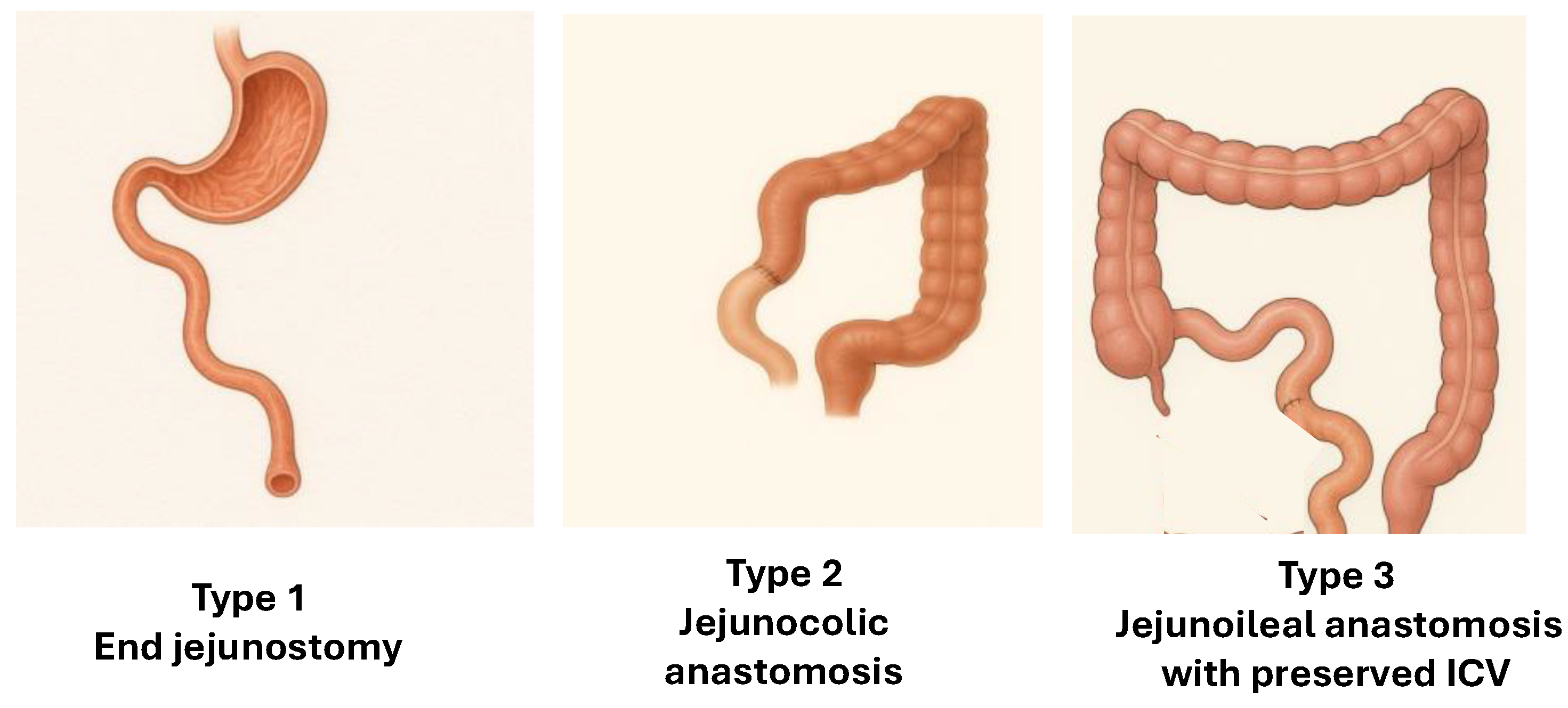

1.1. Anatomical Types of SBS

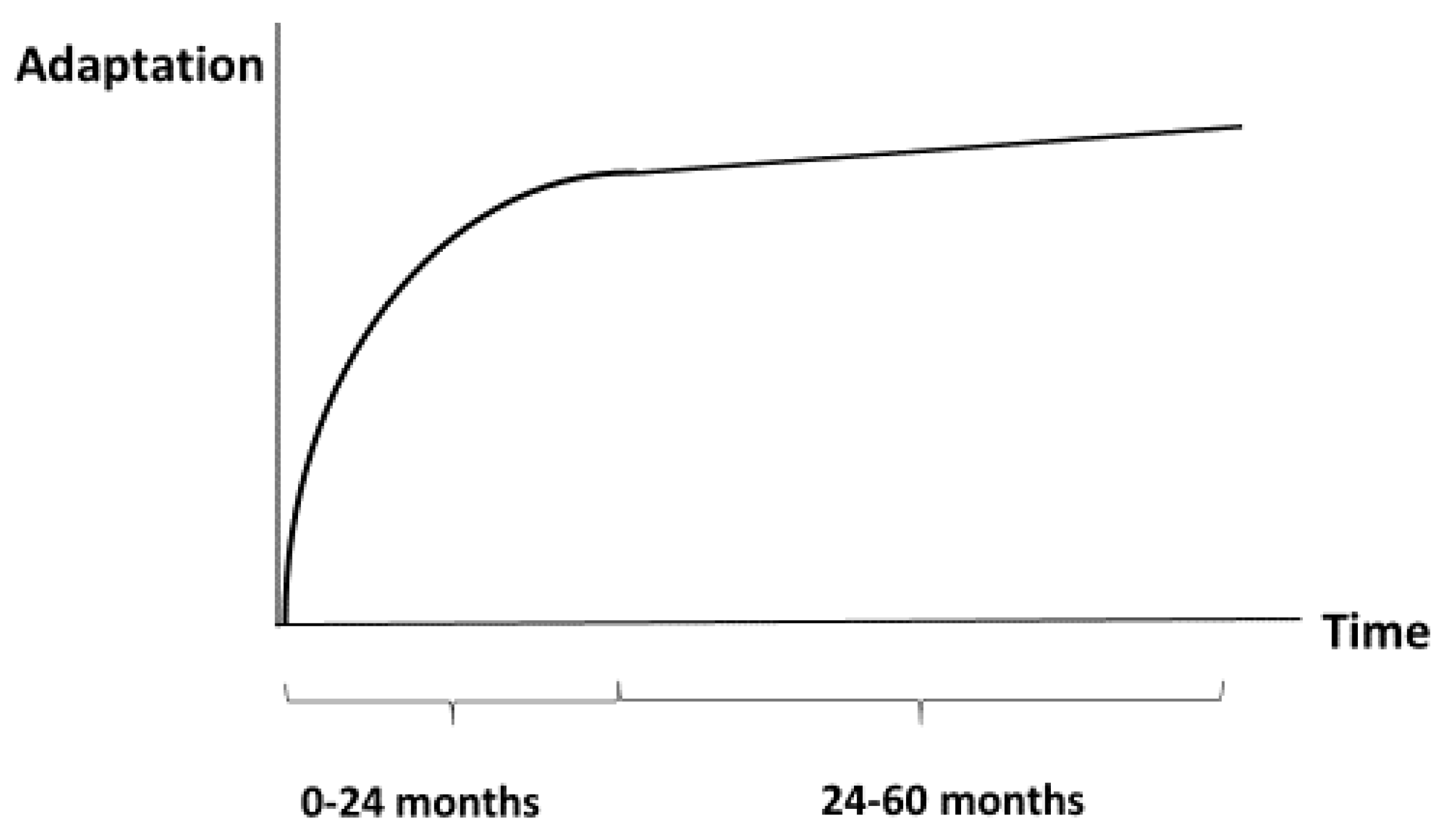

1.2. Intestinal Adaptation: Time Course and Features

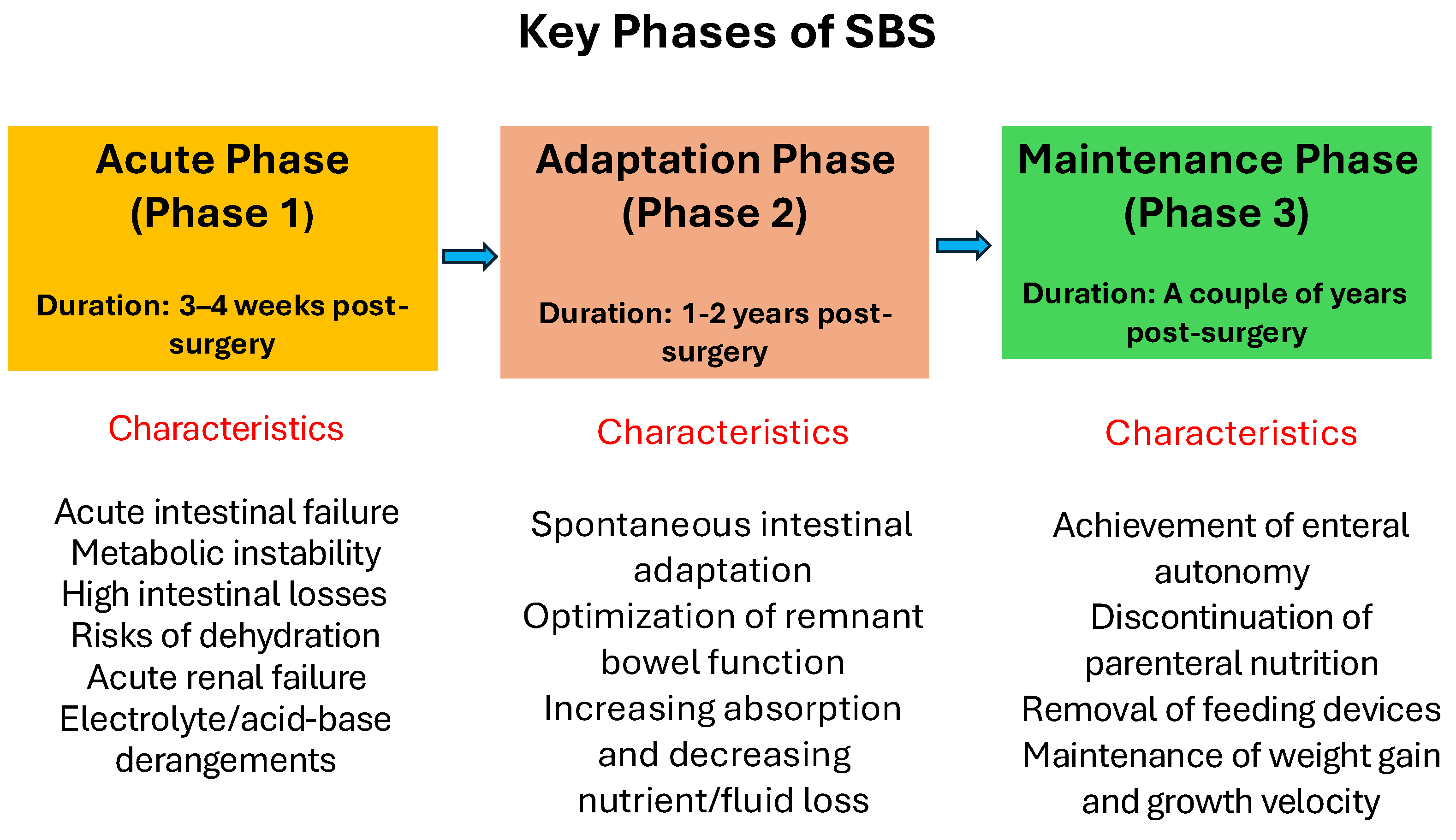

1.3. Postoperative Phases of SBS

- Acute Phase: This phase begins immediately after surgery and typically lasts 3 to 4 weeks. It is characterized by poor absorption of fluids, electrolytes, and nutrients, leading to significant intestinal losses and metabolic disturbances, as well as gastric hypersecretion due to the absence of inhibitory hormones normally released from the terminal ileum.

- Adaptation Phase: Lasting 1 to 2 years, this phase involves adaptive changes in the remaining small bowel to increase both the absorptive surface (structural adaptation) and the absorptive capacity of isolated enterocytes (functional adaptation), ultimately resulting in improved nutrient and micronutrient absorption. These processes are stimulated by the presence of nutrients in the bowel, gastrointestinal secretions, hormones released by the remaining bowel, and the production of peptide growth factors.

- Maintenance Phase: This final phase lasts several years. The goals for managing children with SBS during this phase include achieving enteral autonomy, discontinuing parenteral nutrition, and removing feeding devices while ensuring continued weight gain and growth velocity.

2. Methods

- At what time should enteral nutrition (EN) be initiated? How should EN be advanced and administered?

- What type of EN should be used (focusing on specific macronutrients and micronutrients) during each post-surgical phase?

- What are the features of nutritional management depending on the type of SBS (e.g., site of resection, colon-in-continuity)?

Definitions

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Enteral Nutrition at the First Phase of SBS (Acute Phase, Typically Lasts Weeks to Months).

4.2. Enteral Nutrition at the Second Phase of SBS (Acute phase, Typically Lasts Weeks to 18 Months).

4.3. Enteral Nutrition at the Third Phase of SBS (Maintenance phase, Typically Lasts from 18 -24 Months to Several Years).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Financial disclosure

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Modi, B.P.; Galloway, D.P.; Gura, K.; Nucci, A.; Plogsted, S.; Tucker, A.; Wales, P.W. ASPEN definitions in pediatric intestinal failure. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2022, 46, 42–59. [CrossRef]

- Duggan, C.P.; Jaksic, T. Pediatric intestinal failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 666–675.

- Diamond, I.R.; de Silva, N.; Pencharz, P.B.; Kim, J.H.; Wales, P.W.; Group for the Improvement of Intestinal Function and Treatment. Neonatal short bowel syndrome outcomes after the establishment of the first Canadian multidisciplinary program. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2007, 42, 806–811.

- Premkumar, M.H.; Soraisham, A.; Bagga, N.; Massieu, L.A.; Maheshwari, A. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome. Clin. Perinatol. 2022, 49, 557–572. [CrossRef]

- Lönnerdal, B. Bioactive proteins in human milk—Potential benefits for preterm infants. Clin. Perinatol. 2017, 44, 179–191. [CrossRef]

- Jaksic, T. Current short bowel syndrome management: An era of improved outcomes and continued challenges. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2023, 58, 789–798. [CrossRef]

- Scolapio, J.S.; Fleming, C.R. Short bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 1998, 27, 467–479.

- Gattini, D.; Roberts, A.J.; Wales, P.W.; et al. Trends in pediatric intestinal failure: A multicenter, multinational study. J. Pediatr. 2021, 237, 16–23.e4. [CrossRef]

- Bines, J.E.; Taylor, R.G.; Justice, F.; et al. Influence of diet complexity on intestinal adaptation. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2002, 17, 1170–1179. [CrossRef]

- Arai, Y.; Kinoshita, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; et al. A rare case of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders with short bowel syndrome after strangulated obstruction. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 8, 168. [CrossRef]

- Goulet, O.; Abi Nader, E.; Pigneur, B.; Lambe, C. Short bowel syndrome as the leading cause of intestinal failure in early life. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2019, 22, 303–329. [CrossRef]

- Bines, J.; Francis, D.; Hill, D. Reducing parenteral requirement with amino acid–based formula. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1998, 26, 123–128.

- Ksiazyk, J.; Piena, M.; Kierkus, J.; Lyszkowska, M. Hydrolyzed versus nonhydrolyzed protein diet in children with short bowel syndrome. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2002, 35, 615–618.

- Shores, D.R.; Bullard, J.E.; Aucott, S.W.; et al. Implementation of feeding guidelines in infants at risk of intestinal failure. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 941–948. [CrossRef]

- De Greef, E.; Mahler, T.; Janssen, A.; et al. Influence of Neocate in pediatric short bowel syndrome on PN weaning. J. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 2010, 297575. [CrossRef]

- Andorsky, D.J.; Lund, D.P.; Lillehei, C.W.; Jaksic, T.; Dicanzio, J.; Richardson, D.S.; Collier, S.B.; Lo, C.; Duggan, C. Nutritional and Other Postoperative Management of Neonates with Short Bowel Syndrome Correlates with Clinical Outcomes. J. Pediatr. 2001, 139, 27–33. [CrossRef]

- van Goudoever, J.B.; Carnielli, V.; Darmaun, D.; et al. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition: Amino acids. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 2315–2323. [CrossRef]

- Capriati, T.; Nobili, V.; Stronati, L.; Cucchiara, S.; Laureti, F.; Liguori, A.; Tyndall, E.; Diamanti, A. Enteral nutrition in pediatric intestinal failure: impact of initial feeding on adaptation. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 11, 741–748.

- Tappenden, K.A. Anatomical and physiological considerations in short bowel syndrome. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2023, 38(Suppl. 1), S27–S34. [CrossRef]

- Le Beyec, J.; Billiauws, L.; Bado, A.; Joly, F.; Le Gall, M. Short bowel syndrome: A paradigm for intestinal adaptation. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2020, 40, 299–321. [CrossRef]

- Venick, R.S. Predictors of intestinal adaptation in children. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2019, 48, 499–511. [CrossRef]

- Tappenden, K.A. Mechanisms of enteral nutrient-enhanced intestinal adaptation. Gastroenterology 2006, 130(Suppl. 1), S93–S99. [CrossRef]

- Sukhotnik, I.; Siplovich, L.; Shiloni, E.; et al. Intestinal adaptation in infants and children with SBS. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2002, 18, 258–263.

- Pironi, L. Definition, classification, and causes of short bowel syndrome. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2023, 38(Suppl. 1), S9–S16. [CrossRef]

- Pironi, L. Definitions of intestinal failure and short bowel syndrome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 173–185. [CrossRef]

- Muto, M.; Kaji, T.; Onishi, S.; et al. Current management of pediatric short-bowel syndrome. Surg. Today 2022, 52, 12–21.

- Puoti, M.G.; Köglmeier, J. Nutritional management of intestinal failure due to short bowel syndrome in children. Nutrients 2023, 15, 62. [CrossRef]

- Sondheimer, J.M.; Cadnapaphornchai, M.; Sontag, M.; Zerbe, G.O. Predicting PN duration after neonatal intestinal resection. J. Pediatr. 1998, 132, 80–84.

- Tappenden, K.A. Intestinal adaptation following resection. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2014, 38(Suppl. 1), 23S–31S. [CrossRef]

- Eshel Fuhrer, A.; Sukhotnik, S.; Moran-Lev, H.; et al. Motility disorders in children with intestinal failure. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2022, 38, 1737–1743. [CrossRef]

- Hukkinen, M.; Mutanen, A.; Pakarinen, M.P. Small bowel dilation and risk of mucosal injury in SBS. Surgery 2017, 162, 670–679.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; et al. PRISMA-ScR extension. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473.

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; et al. STROBE statement. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499.

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; et al. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020.

- Tyson, J.E.; Kennedy, K.A. Minimal enteral feeding for feeding tolerance. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1997, CD000504.

- Bobo, E.; King, L.M. Techniques for advancing feeds in pediatric intestinal failure. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2025, 40, 1000–1012.

- Goulet, O.; Olieman, J.; Ksiazyk, J.; et al. Neonatal short bowel syndrome as a model of intestinal failure. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 162–171. [CrossRef]

- Moltu, S.J.; Bronsky, J.; Embleton, N.; et al. Nutritional management of the critically ill neonate. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 73, 274–289. [CrossRef]

- Norsa, L.; Goulet, O.; Alberti, D.; et al. Nutrition and intestinal rehabilitation of children with SBS: Part 1. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2023, 77, 281–297.

- Iyer, K.; DiBaise, J.K.; Rubio-Tapia, A. AGA clinical practice update on SBS. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2185–2194.e2.

- Olieman, J.; Kastelijn, W. Nutritional feeding strategies in pediatric intestinal failure. Nutrients 2020, 12, 177. [CrossRef]

- Olieman, J.F.; Penning, C.; IJsselstijn, H.; et al. Enteral nutrition in children with short-bowel syndrome. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 420–426. [CrossRef]

- Verlato, G.; Hill, S.; Jonkers-Schuitema, C.; et al. International survey on feeding in infants with SBS. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 73, 647–653.

- Avitzur, Y.; Courtney-Martin, G. Enteral approaches in malabsorption. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 295–307. [CrossRef]

- Parvadia, J.K.; Keswani, S.G.; Vaikunth, S.; et al. VEGF and bowel adaptation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007, 293, G591–G598.

- Micic, D.; Martin, J.A.; Fang, J. AGA clinical update on endoscopic enteral access. Gastroenterology 2025, 168, 164–168.

- Channabasappa, N.; Girouard, S.; Nguyen, V.; Piper, H. Enteral Nutrition in Pediatric Short-Bowel Syndrome. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 2020, 35, 848–854. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.M.; Skillman, H.E.; Irving, S.Y.; et al. Nutrition support in pediatric critical illness. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 706–742.

- Michaud, L.; Coopman, S.; Guimber, D.; et al. Percutaneous gastrojejunostomy in children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012, 97, 733–734. [CrossRef]

- Braegger, C.; Decsi, T.; Dias, J.A.; et al. ESPGHAN comment on pediatric enteral nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010, 51, 110–122.

- Parker, P.; Stroop, S.; Greene, H. Continuous vs intermittent feeding in infants with intestinal disease. J. Pediatr. 1981, 99, 360–364.

- Levy, E.; Frileux, P.; Sandrucci, S.; et al. Continuous enteral nutrition during early adaptation in SBS. Br. J. Surg. 1988, 75, 549–553.

- Weizman, Z.; Schmueli, A.; Deckelbaum, R.J. Continuous nasogastric elemental feeding for prolonged diarrhea. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1983, 137, 253–255.

- Joly, F.; Dray, X.; Corcos, O.; Barbot, L.; Kapel, N.; Messing, B. Tube Feeding Improves Intestinal Absorption in Short Bowel Syndrome Patients. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 824–831. [CrossRef]

- Schanler, R.J.; Shulman, R.J.; Lau, C.; Smith, E.O.; Heitkemper, M.M. Feeding strategies for premature infants: randomized trial of GI priming and tube-feeding method. Pediatrics 1999, 103, 434–439.

- Premji, S.S.; Chessell, L. Continuous nasogastric milk feeding versus intermittent bolus feeding for premature infants <1500 g. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002, CD001819.

- Parker, M.G.; Stellwagen, L.M.; Noble, L.; Kim, J.H.; Poindexter, B.B.; Puopolo, K.M. Promoting human milk and breastfeeding for the very low birth weight infant. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021054272. [CrossRef]

- Manea, A.; Boia, M.; Iacob, D.; Dima, M.; Iacob, R.E. Benefits of early enteral nutrition in extremely low birth weight infants. Singapore Med. J. 2016, 57, 616–618. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Mercado, V.; Rios, M.; Arboleda, R.; Gomara, R.; Muinos, W.; Reeves-Garcia, J.; Hernandez, E. Breast milk vs formula in preventing PN-associated liver disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 57, 383–388.

- Quigley, M.; Embleton, N.D.; Meader, N.; McGuire, W. Donor human milk for preventing NEC in very preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, CD002971.

- Li, Y.; Chi, C.; Li, C.; Song, J.; Song, Z.; Wang, W.; Sun, J. Efficacy of donated milk in early nutrition of preterm infants: A meta-analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1724. [CrossRef]

- Hoban, R.; Khatri, S.; Patel, A.; Unger, S.L. Supplementation of mother’s own milk with donor milk in infants with gastroschisis or intestinal atresia. Nutrients 2020, 12, 589. [CrossRef]

- Roskes, L.; Chamzas, A.; Ma, B.; Medina, A.E.; Gopalakrishnan, M.; Viscardi, R.M.; Sundararajan, S. Early human milk feeding: intestinal barrier maturation and growth. Pediatr. Res. 2025, 97, 2065–2073.

- Parra-Llorca, A.; Gormaz, M.; Alcántara, C.; Cernada, M.; Nuñez-Ramiro, A.; Vento, M.; Collado, M.C. Preterm gut microbiome depending on feeding type: significance of donor milk. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1376. [CrossRef]

- Mezoff, E.A.; Hawkins, J.A.; Ollberding, N.J.; Karns, R.; Morrow, A.L.; Helmrath, M.A. 2’-Fucosyllactose augments adaptive response to intestinal resection. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2016, 310, G427–G438.

- Burge, K.; Vieira, F.; Eckert, J.; Chaaban, H. Lipid composition and absorption differences among neonatal feeding strategies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1–19.

- Peila, C.; Moro, G.E.; Bertino, E.; et al. Effect of Holder pasteurization on donor human milk nutrients and bioactive components. Nutrients 2016, 8, 477.

- Colaizy, T.T. Effects of milk banking procedures on donor human milk components. Semin. Perinatol. 2021, 45, 151382.

- Cheng, L.; Akkerman, R.; Kong, C.; Walvoort, M.T.C.; de Vos, P. Human milk oligosaccharides as essential bioactive molecules. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1184–1200. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; van der Molen, J.; Kuipers, F.; van Leeuwen, S.S. Quantitation of bioactive components in infant formulas. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113589.

- Clifford, V.; Klein, L.D.; Brown, R.; et al. Donor and recipient safety in human milk banking. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2022, 58, 1629–1634. [CrossRef]

- Coutsoudis, I.; Adhikari, M.; Nair, N.; Coutsoudis, A. Feasibility of donor breastmilk bank in resource-limited neonatal units. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 356.

- Adhisivam, B., Vishnu Bhat, B., Rao, K., Kingsley, S.M., Plakkal, N., Palanivel, C. Effect of Holder pasteurization on macronutrients and immunoglobulin profile of pooled donor human milk. J, Matern, Fetal, Neonatal, Med. 2019,32(18):3016-3019. [CrossRef]

- Piemontese, P., Mallardi, D., Liotto, N., Tabasso, C., Menis, C., Perrone, M., Roggero, P., Mosca, F. Macronutrient content of pooled donor human milk before and after Holder pasteurization. BMC. Pediatr. 2019, 19(1):58. [CrossRef]

- Kreissl, A.; Zwiauer, V.; Repa, A.; et al. Effect of fortifiers and protein on human milk osmolarity. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 57, 432–437.

- Chinnappan, A.; Sharma, A.; Agarwal, R.; Thukral, A.; Deorari, A.; Sankar, M.J. Breast milk fortification with preterm formula vs HMF. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 790.

- Herranz Barbero, A.; Rico, N.; Oller-Salvia, B.; et al. Fortifier selection and dosage enables control of breast milk osmolarity. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0233924. [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Turner, J.M.; Mager, D.R.; et al. Polymeric vs elemental formula in neonatal piglets with SBS. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2014, 38, 498–506.

- El Hassani, A.; Michaud, L.; Chartier, A.; et al. Cow’s milk protein allergy after neonatal intestinal surgery. Arch. Pediatr. 2005, 12, 134–139.

- Diamanti, A.; Fiocchi, A.G.; Capriati, T.; et al. Cow’s milk allergy and neonatal SBS. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 102–106.

- Stamm, D.A.; Hait, E.; Litman, H.J.; Mitchell, P.D.; Duggan, C. High prevalence of eosinophilic GI disease in intestinal failure. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 63, 336–339.

- Masumoto, K.; Esumi, G.; Teshiba, R.; et al. Cow’s milk allergy in extremely short bowel syndrome. e-SPEN 2008, 3, e147–e150.

- Neelis, E.G.; Olieman, J.F.; Hulst, J.M.; et al. Promoting intestinal adaptation by nutrition and medication. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 249–261. [CrossRef]

- Matarese, L.E. Nutrition and fluid optimization for short bowel syndrome. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 161–170.

- Arrigoni, E.; Marteau, P.; Briet, F.; et al. Lactose tolerance and absorption in short bowel syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 60, 926–929.

- Marteau, P.; Messing, B.; Arrigoni, E.; et al. Do SBS patients need a lactose-free diet? Nutrition 1997, 13, 13–16.

- Jeppesen, P.B.; Mortensen, P.B. Influence of preserved colon on medium-chain fat absorption. Gut 1998, 43, 478–483.

- Vanderhoof, J.A.; Grandjean, C.J.; Kaufman, S.S.; et al. High–medium-chain triglyceride diet and mucosal adaptation. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 1984, 8, 685–689.

- Fewtrell, M.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; et al. Complementary feeding: ESPGHAN guidelines. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 119–132.

- Sukhotnik, I.; Mor-Vaknin, N.; Drongowski, R.A.; et al. Effect of dietary fat on intestinal adaptation in SBS rats. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2004, 20, 419–424.

- Choi, P.M.; Sun, R.C.; Guo, J.; Erwin, C.R.; Warner, B.W. High-fat diet enhances villus growth after massive resection. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014, 18, 286–294.

- Sukhotnik, I.; Shiloni, E.; Krausz, M.M.; et al. Low-fat diet impairs postresection adaptation. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2003, 38, 1182–1187.

- Sukhotnik, I.; Gork, A.S.; Chen, M.; et al. Low-fat diet and fatty-acid transport after resection. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2001, 17, 259–264.

- Ovesen, L.; Chu, R.; Howard, L. Influence of dietary fat on jejunostomy output in severe SBS. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1983, 38, 270–277.

- Schaefer, J.T.; Schulz-Heise, S.; Rueckel, A.; et al. Enteric hyperoxaluria in pediatric SBS. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1157696.

- Atia, A.; Girard-Pipau, F.; Hébuterne, X.; et al. Macronutrient absorption in SBS with jejunocolonic anastomosis. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2011, 35, 229–240.

- Drenckpohl, D.; Hocker, J.; Shareef, M.; et al. Green beans resolving diarrhea after neonatal bowel surgery: case study. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2005, 20, 674–677.

- Brindle, M.E.; McDiarmid, C.; Short, K.; et al. ERAS guidelines for neonatal intestinal surgery. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 2482–2492.

- O’Neil, M.; Teitelbaum, D.H.; Harris, M.B. Sodium depletion and poor weight gain in ileostomy patients. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2014, 29, 397–401.

- Schwarz, K.B.; Ternberg, J.L.; Bell, M.J.; Keating, J.P. Sodium needs in infants with ileostomy. J. Pediatr. 1983, 102, 509–513.

- Hoppe, B.; Leumann, E.; von Unruh, G.; et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in secondary hyperoxaluria. Front. Biosci. 2003, 8, e437–e443.

- Adler, M.; Millar, E.C.; Deans, K.A.; Torreggiani, M.; Moroni, F. Nutrition and CKD-related hyperoxaluria in SBS. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3441.

- Sundaram, A.; Koutkia, P.; Apovian, C.M. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2002, 5, 267–275. [CrossRef]

- Weston, S.; Algotar, A.; Karjoo, S.; et al. State-of-the-art review of blenderized diets. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2025, 81, 376–386.

- Zong, W.; Troutt, R.; Merves, J. Blenderized enteral nutrition in pediatric short gut syndrome. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2022, 37, 913–920. [CrossRef]

- DePaula, B.; Mitchell, P.D.; Reese, E.; Gray, M.; Duggan, C.P. Parenteral nutrition dependence and growth in pediatric intestinal failure after transition to blenderized feeds: case series. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2025, 40, 188–194.

- Samela, K.; Mokha, J.; Emerick, K.; Davidovics, Z.H. Transition to real-food ingredient tube formulas in pediatric intestinal failure. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2017, 32, 277–281.

- Gutierrez, I.M.; Kang, K.H.; Jaksic, T. Neonatal short bowel syndrome. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011, 16, 157–163. [CrossRef]

- Hill, S. Practical management of home parenteral nutrition in infancy. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 138, 104876. [CrossRef]

- Enman, M.A.; Wilkinson, L.T.; Meloni, K.B.; Shroyer, M.C.; Jackson, T.F.; Aban, I.; Dimmitt, R.A.; Martin, C.A.; Galloway, D.P. Determinants of enteral autonomy and reduced PN exposure in pediatric intestinal failure. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2020, 44, 1263–1270.

- Norsa, L.; Goulet, O.; Alberti, D.; et al. Nutrition and intestinal rehabilitation in children with SBS: Part 2, long-term follow-up on home PN. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2023, 77, 298–314.

- Khan, F.A.; Squires, R.H.; Litman, H.J.; et al. Predictors of enteral autonomy in pediatric intestinal failure: multicenter cohort. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 29–34.e1.

- Schofield, W.N. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Human Nutrition: Clinical Nutrition.1985, 39 Suppl 1: 5–41.

- Abi Nader, E.; Lambe, C.; Talbotec, C.; Acramel, A.; Pigneur, B.; Goulet, O. Metabolic bone disease in pediatric intestinal failure is not associated with PN dependency. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1974–1982.

- Proli, F.; Faragalli, A.; Talbotec, C.; Bucci, A.; Zemrani, B.; Chardot, C.; Abi Nader, E.; Goulet, O.; Lambe, C. Plasma citrulline variation predicts PN-weaning in neonatal short bowel syndrome. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4941–4947.

- Belza, C.; Fitzgerald, K.; de Silva, N.; Avitzur, Y.; Wales, P.W. Early predictors of enteral autonomy in pediatric intestinal failure: development of a severity scoring tool. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2019, 43, 961–969.

- Roggero, P.; Liotto, N.; Piemontese, P.; Menis, C.; Perrone, M.; Tabasso, C.; et al. Neonatal intestinal failure: growth pattern and nutrition during PN weaning. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2023, 47, 236–244.

- Worthington, P.; Balint, J.; Bechtold, M.; Bingham, A.; Chan, L.N.; Durfee, S.; Jevenn, A.K.; Malone, A.; Mascarenhas, M.; Robinson, D.T.; et al. When is parenteral nutrition appropriate? JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 324–377.

- Tannuri, U.; Barros, F. de; Tannuri, A.C.A. Treatment of short bowel syndrome in children: value of intestinal rehabilitation program. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2016, 62, 575–583. [CrossRef]

- Puntis, J.W.L.; Hojsak, I.; Ksiazyk, J.; Braegger, C.; Bronsky, J.; Cai, W.; Carnielli, V.; Darmaun, D.; Decsi, T.; et al. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition: organizational aspects. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 2392–2400. [CrossRef]

- Stanner, H.; Zelig, R.; Rigassio Radler, D. Impact of infusion frequency on quality of life in home PN patients. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2022, 46, 757–770.

- Dibaise, J.K.; Matarese, L.E.; Messing, B.; Steiger, E. Strategies for PN weaning in adult SBS. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006, 40(Suppl. 2), S94–S98.

- Kaenkumchorn, T.K.; Lampone, O.; Huebner, K.; Cramer, J.; Karls, C. When PN is the answer: pediatric intestinal rehabilitation case series. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2024, 39, 991–1002.

- Hopkins, J.; Cermak, S.A.; Merritt, R.J. Oral feeding difficulties in children with short bowel syndrome: narrative review. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2018, 33, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Boctor, D.L.; Jutteau, W.H.; Fenton, T.R.; Shourounis, J.; Galante, G.J.; Eicher, I.; Goulet, O.; Lambe, C. Feeding difficulties and risk factors in pediatric intestinal failure. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5399–5406.

- Ubesie, A.C.; Kocoshis, S.A.; Mezoff, A.G.; Henderson, C.J.; Helmrath, M.A.; Cole, C.R. Multiple micronutrient deficiencies during and after transition to enteral nutrition. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 1692–1696.

- Neelis, E.; Olieman, J.; Rizopoulos, D.; Wijnen, R.; Rings, E.; de Koning, B.; Hulst, J. Growth, body composition, and micronutrient abnormalities after weaning off home PN. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 67, e95–e100.

- Tuokkola, J.; Olkkonen, E.; Gunnar, R.; Pakarinen, M.; Merras-Salmio, L. Vitamin and trace element status in children with SBS being weaned off PN. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2025, 80, 318–325.

- Gunnar, R.; Lumia, M.; Pakarinen, M.; Merras-Salmio, L. Essential fatty acid deficiency risk during intestinal rehabilitation. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2018, 42, 1203–1210.

- Durfee, S.M.; Adams, S.C.; Arthur, E.; Corrigan, M.L.; Hammond, K.; Kovacevich, D.S.; McNamara, K.; Pasquale, J.A. A.S.P.E.N. standards for nutrition support: home and alternate site care. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2014, 29, 542–555.

| PICOS Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| P (Population) | Neonates, infants, and older children with SBS | Children with intestinal failure due to motility disorders; children with SBS >5 years of follow-up |

| I (Intervention) | Full-text papers, including RCTs, prospective cohort, analytical cross-sectional, case–control, longitudinal, case series, and retrospective cross-sectional studies | Studies using incompatible virtual methods; studies primarily focused on medical or surgical management of SBS |

| C (Comparators) | Studies comparing outcomes of nutritional management during different SBS phases or between anatomical SBS types | Studies comparing nutritional management in children vs. adults with SBS |

| O (Outcomes) | Survival, achievement of EA (weaning off PN), and complication rates | Incomplete results |

| S (Study Design) | Studies published in English between January 1974 and December 2024, indexed in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, CENTRAL, SciELO, and Google Scholar | Duplicates, conference papers, abstracts, and non-English case reports |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).