Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

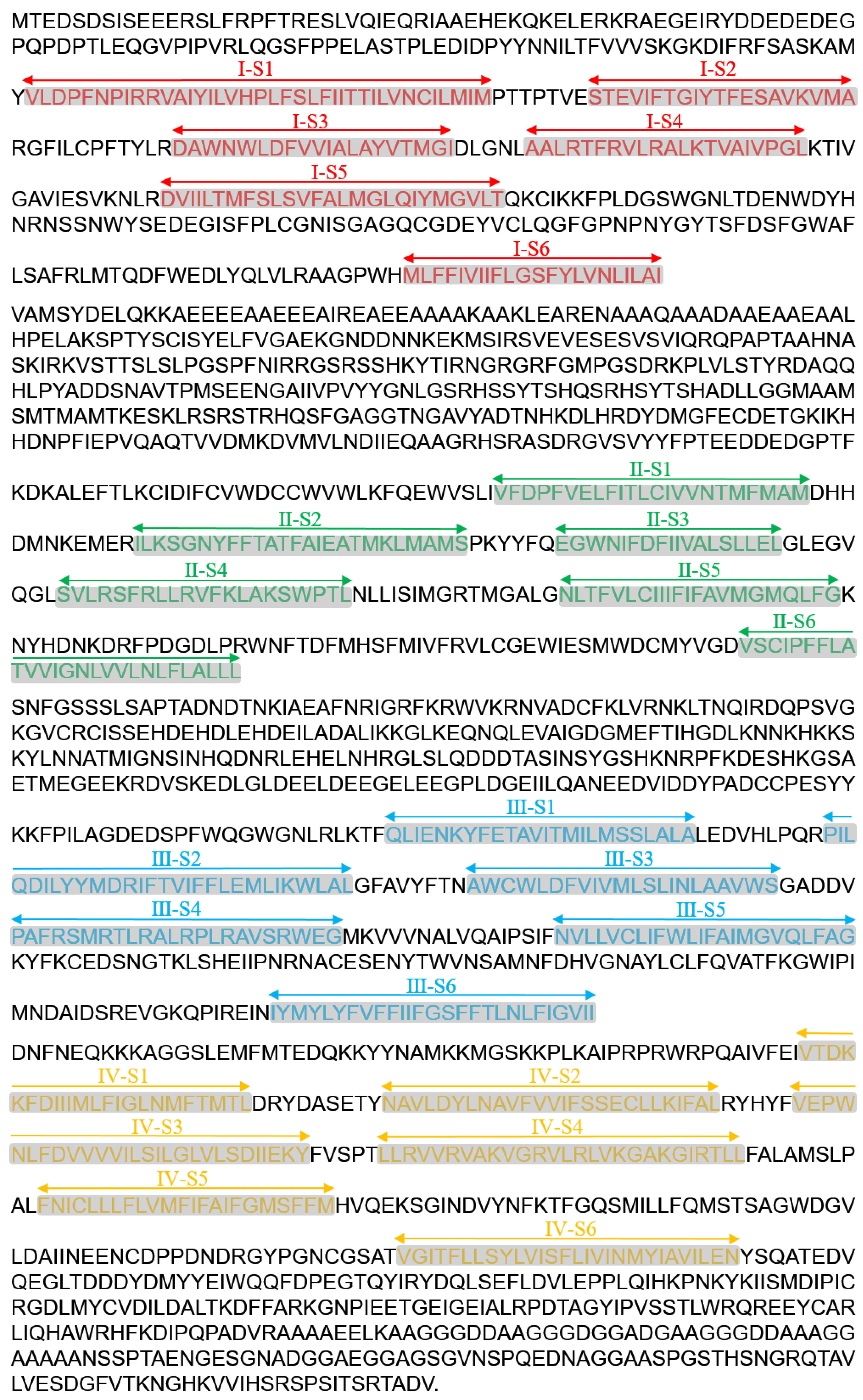

2.1. Complete Genomic Information of VGSC in L. trifolii

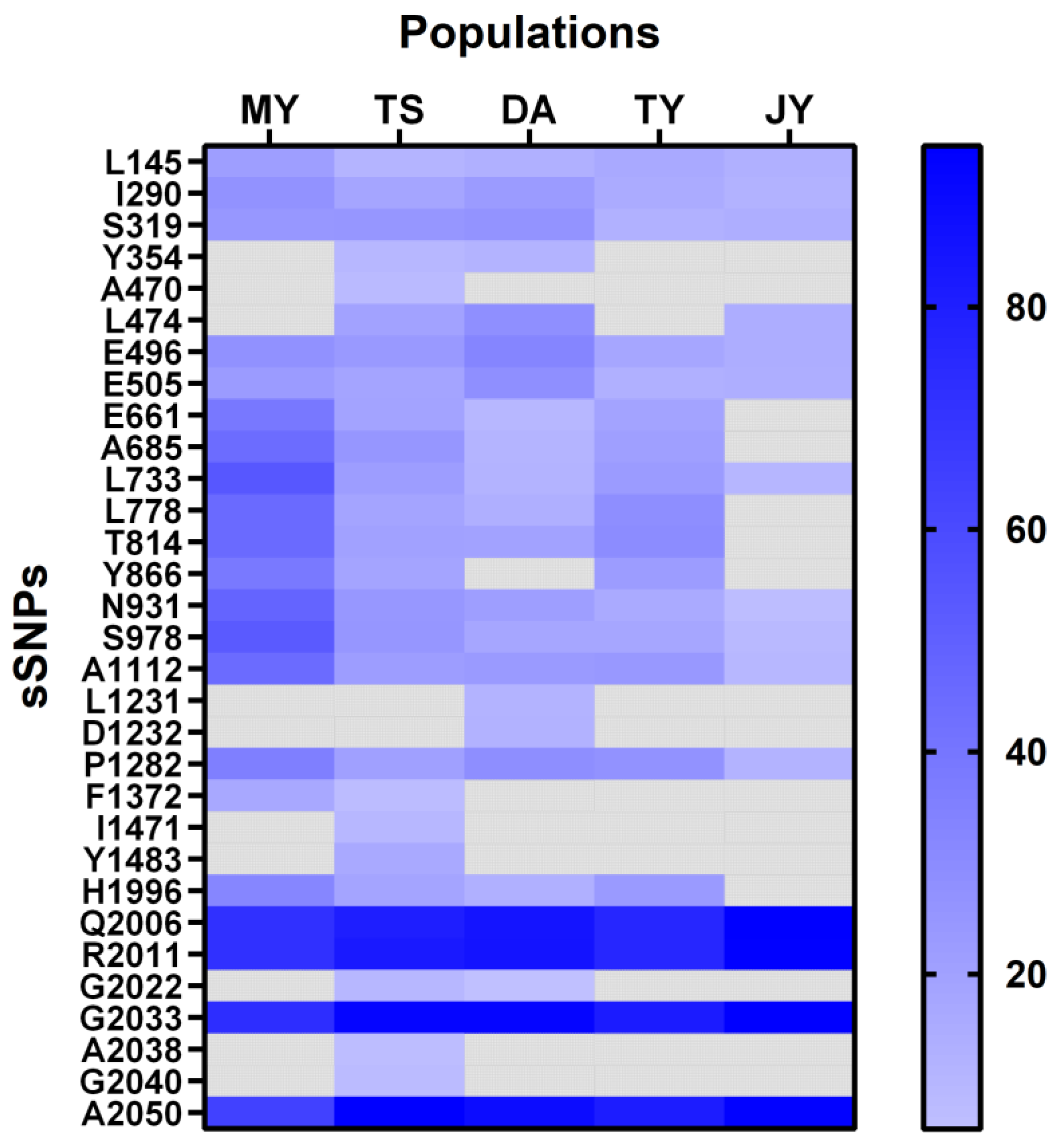

2.2. Information of Exonic Synonymous sSNP in L. trifolii

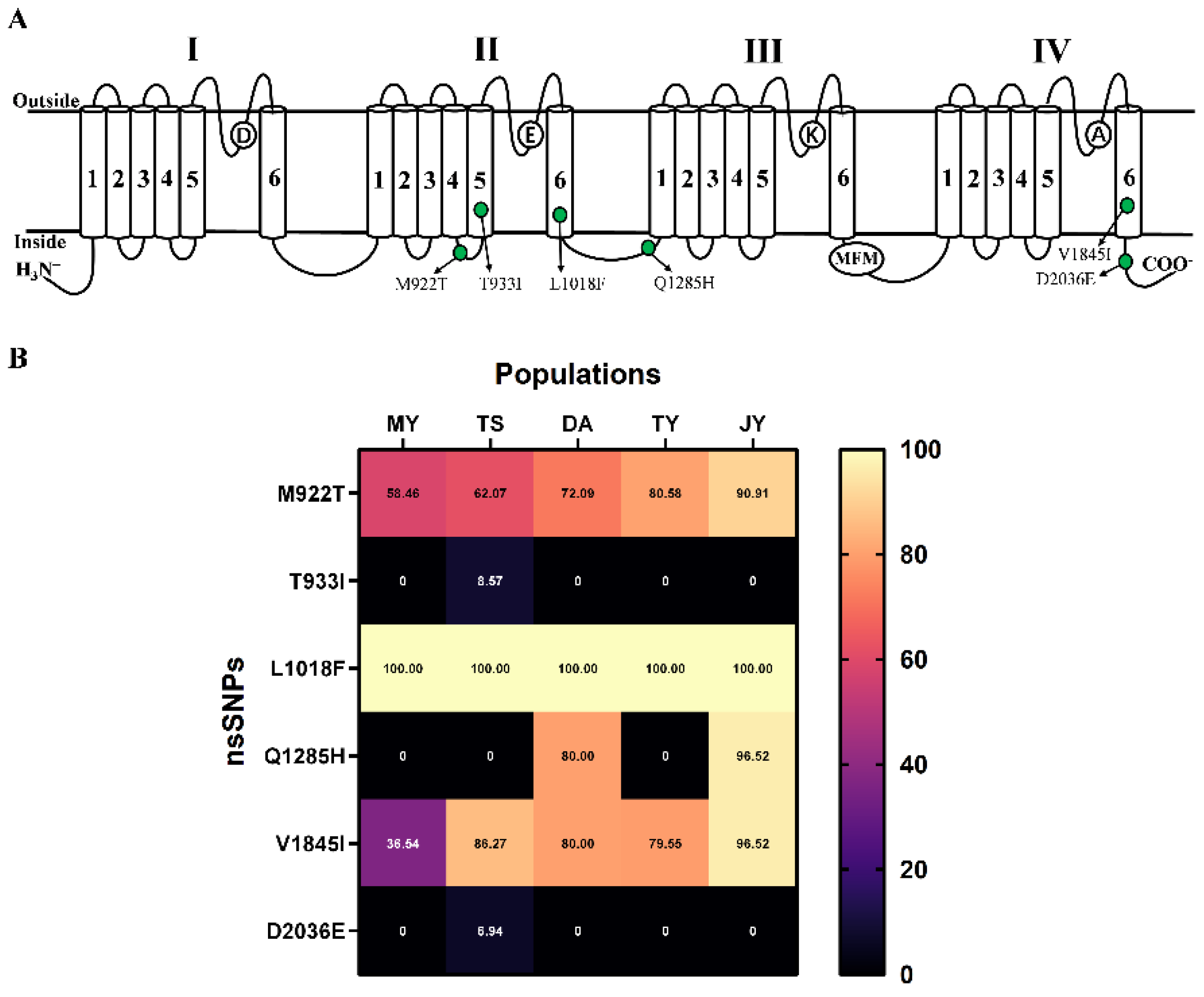

2.3. Information of Exonic nsSNP in L. trifolii

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

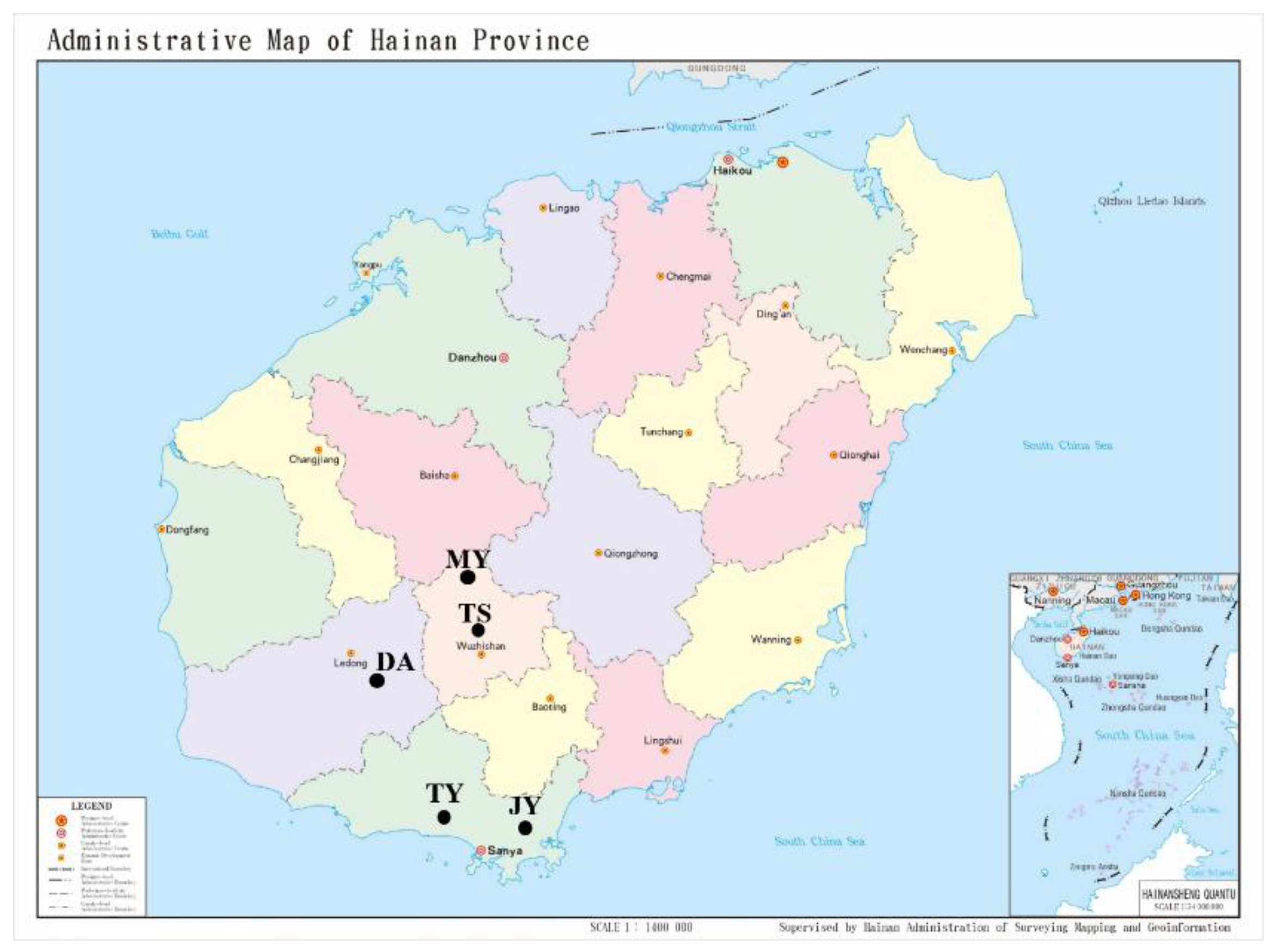

4.1. Insects Collection

4.2. Acquisition of Complete Genomic of VGSC in L. trifolii and Sequencing WGS

4.3. Analysis and Acquisition of sSNP and nsSNP in VGSC of the L. trifolii

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scheffer, S.J.; Lewis, M.L. Mitochondrial Phylogeography of the Vegetable Pest Liriomyza Trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae): Diverged Clades and Invasive Populations. Ann Entomol. Soc. Am 2006, 99, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, K.A. Agromyzidae (Diptera) of Economic Importance; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1973; ISBN 978-90-481-8513-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.L.; Reitz, S.; Xing, Zhen Long; Ferguson, S.; Lei, Z.R. A Decade of Leafminer Invasion in China: Lessons Learned. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, Y.; Tokumaru, S. Displacement in Two Invasive Species of Leafminer Fly in Different Localities. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 951–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurer, B. Pyrethrum Flowers. Production, Chemistry, Toxicology, and Uses. Brittonia 1996, 48, 613–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.G.E.; Field, L.M.; Usherwood, P.N.R.; Williamson, M.S. DDT, Pyrethrins, Pyrethroids and Insect Sodium Channels. IUBMB Life 2007, 59, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Du, Y.Z.; Rinkevich, F.; Nomura, Y.; Xu, P.; Wang, L.; Silver, K.; Zhorov, B.S. Molecular Biology of Insect Sodium Channels and Pyrethroid Resistance. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, K. Insect Sodium Channels and Insecticide Resistance. Invert Neurosci. 2007, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soderlund, D.M.; Bloomquist, J.R. Molecular Mechanisms of Insecticide Resistance. In Pesticide Resistance in Arthropods; Roush, R.T., Tabashnik, B.E., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1990; pp. 58–96. ISBN 978-1-4684-6431-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.X.; Du, Y.Z.; Nomura, Y.; Wang, X.L.; Wu, Y.D.; Zhorov, B.S.; Dong, K. Mutations in the Transmembrane Helix S6 of Domain IV Confer Cockroach Sodium Channel Resistance to Sodium Channel Blocker Insecticides and Local Anesthetics. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 66, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roditakis, E.; Mavridis, K.; Riga, M.; Vasakis, E.; Morou, E.; Rison, J.L.; Vontas, J. Identification and Detection of Indoxacarb Resistance Mutations in the Para Sodium Channel of the Tomato Leafminer, Tuta Absoluta. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Su, W.; Zhang, J.H.; Yang, Y.H.; Dong, K.; Wu, Y.D. Two Novel Sodium Channel Mutations Associated with Resistance to Indoxacarb and Metaflumizone in the Diamondback Moth, Plutella Xylostella. Insect Sci. 2016, 23, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Du, Y.Z.; Jiang, D.X.; Behnke, C.; Nomura, Y.; Zhorov, B.S.; Dong, K. The Receptor Site and Mechanism of Action of Sodium Channel Blocker Insecticides. J Biological Chem. 2016, 291, 20113–20124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A. From Ionic Currents to Molecular Mechanisms: The Structure and Function of Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. Neuron 2000, 26, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, A.O.; Khambay, B.P.S.; Williamson, M.S.; Field, L.M.; WAllace, B.A.; Davies, T.G.E. Modelling Insecticide-Binding Sites in the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel. Biochem. J 2006, 396, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.Z.; Nomura, Y.; Satar, G.; Hu, Z.N.; Nauen, R.; He, S.Y.; Zhorov, B.S.; Dong, K. Molecular Evidence for Dual Pyrethroid-Receptor Sites on a Mosquito Sodium Channel. P Natl. A. Sci. 2013, 110, 11785–11790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şulea, T.A.; Draga, S.; Mernea, M.; Corlan, A.D.; Radu, B.M.; Petrescu, A.-J.; Amuzescu, B. Differential Inhibition by Cenobamate of Canonical Human Nav1.5 Ion Channels and Several Point Mutants. IJMS 2025, 26, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosme, L.V.; Lima, J.B.P.; Powell, J.R.; Martins, A.J. Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals New Loci Associated with Pyrethroid Resistance in Aedes Aegypti. Front. Genet. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Fu, P.; Chen, Y.; Wan, F.; Hu, G.; Gui, F. Employing Genome-Wide Association Studies and Machine Learning to Accurately Identify Eastern and Western Migratory Pathways of Spodoptera Frugiperda in China via Key Molecular Markers. Ecol. Inf. 2025, 92, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Lei, Z.R.; Abe, Y.; Reitz, S.R. Species Displacements Are Common to Two Invasive Species of Leafminer Fly in China, Japan, and the United States. J Econ Entomol 2011, 104, 1771–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeeluck, D.; Dunhawoor, C.; Unmole, L. Development and Implementation of Integrated Pest Management in Mauritius an Overview. University of Mauritius Research Journal 2009, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, C.B.; Parrella, M.P.; Morse, J.G. Method for Monitoring and Establishing Baseline Data for Resistance to Permethrin by Liriomyza Trifolii (Burgess). J Econ Entomol 1985, 78, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, G.A.; Johnson, M.W.; Tabashnik, B.E. Susceptibility of Liriomyza Sativae and L. Trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae) to Permethrin and Fenvalerate. J Econ Entomol 1987, 80, 1262–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, O.C. Responses of the Alien Leaf Miners Liriomyza Trifolii and Liriomyza Huidobrensis (Diptera: Agromyzidae) to Some Pesticides Scheduled for Their Control in the UK. Crop Prot. 1991, 10, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrella, M.P.; Trumble, J.T. Decline of Resistance in Liriomyza Trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae) in the Absence of Insecticide Selection Pressure. J Econ Entomol 1989, 82, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, T.C.; Nauen, R. IRAC: Mode of Action Classification and Insecticide Resistance Management. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 121, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Gong, X.Y.; Yuan, L.L.; Pan, X.L.; Jin, H.F.; Lu, R.C.; Wu, S.Y. Indoxacarb Resistance-Associated Mutation of Liriomyza Trifolii in Hainan, China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 183, 105054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vais, H.; Atkinson, S.; Eldursi, N.; Devonshire, A.L.; Williamson, M.S.; Usherwood, P.N.R. A Single Amino Acid Change Makes a Rat Neuronal Sodium Channel Highly Sensitive to Pyrethroid Insecticides. FEBS Letters 2000, 470, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.M.; Symington, S.B. Advances in the Mode of Action of Pyrethroids. Pyrethroids: From Chrysanthemum to Modern Industrial Insecticide 2012, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, D.P.; Poynton, H.C.; Wellborn, G.A.; Lydy, M.J.; Blalock, B.J.; Sepulveda, M.S.; Colbourne, J.K. Multiple Origins of Pyrethroid Insecticide Resistance across the Species Complex of a Nontarget Aquatic Crustacean, Hyalella Azteca. P Natl. A. Sci. 2013, 110, 16532–16537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, S.; Williamson, M.S.; Goodson, S.J.; Brown, J.K.; Tabashnik, B.E.; Dennehy, T.J. Mutations in the Bemisia Tabaci Para Sodium Channel Gene Associated with Resistance to a Pyrethroid plus Organophosphate Mixture. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002, 32, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinkevich, F.D.; Du, Y.Z.; Dong, K. Diversity and Convergence of Sodium Channel Mutations Involved in Resistance to Pyrethroids. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2013, 106, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.J.; Mellor, I.R.; Duce, I.R.; Davies, T.G.E.; Field, L.M.; Williamson, M.S. Differential Resistance of Insect Sodium Channels with Kdr Mutations to Deltamethrin, Permethrin and DDT. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 41, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayati, A.A.; Vatandoost, H.; Ladonni, H.; Townson, H.; Hemingway, J. Molecular Evidence for a Kdr-like Pyrethroid Resistance Mechanism in the Malaria Vector Mosquito Anopheles Stephensi. Med Vet Entomol 2003, 17, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, M.; Ohyama, K.; Dunlap, D.Y.; Matsumura, F. Cloning and Sequencing of Thepara-Type Sodium Channel Gene from Susceptible Andkdr-Resistant German Cockroaches (Blattella Germanica) and House Fly (Musca Domestica). Molec. Gen. Genet. 1996, 252, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, C.; Schroeder, I.; Turberg, A.; M Field, L.; S Williamson, M. Identification of Mutations Associated with Pyrethroid Resistance in the Para-Type Sodium Channel of the Cat Flea, Ctenocephalides Felis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 34, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun-Barale, A.; Bouvier, J.-C.; Pauron, D.; Bergé, J.-B.; Sauphanor, B. Involvement of a Sodium Channel Mutation in Pyrethroid Resistance in Cydia Pomonella L, and Development of a Diagnostic Test. Pest Manag. Sci. 2005, 61, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forcioli, D.; Frey, B.; Frey, J.E. High Nucleotide Diversity in the Para-like Voltage-Sensitive Sodium Channel Gene Sequence in the Western Flower Thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). J Econ Entomol 2002, 95, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyeock Lee, S.; Smith, T.; C. Knipple, D.; Soderlund, D. Mutations in the House Fly Vssc1 Sodium Channel Gene Associated with Super-Kdr Resistance Abolish the Pyrethroid Sensitivity of Vssc1/tipE Sodium Channels Expressed in Xenopus Oocytes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999, 29, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.G.E.; Field, L.M.; Usherwood, P.N.R.; Williamson, M.S. A Comparative Study of Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels in the Insecta: Implications for Pyrethroid Resistance in Anopheline and Other Neopteran Species. Insect Mol. Biol. 2007, 16, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauen, R.; Zimmer, C.T.; Andrews, M.; Slater, R.; Bass, C.; Ekbom, B.; Gustafsson, G.; Hansen, L.M.; Kristensen, M.; Zebitz, C.P.W. Target-Site Resistance to Pyrethroids in European Populations of Pollen Beetle, Meligethes Aeneus F. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 103, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingles, P.J.; Adams, P.M.; Knipple, D.C.; Soderlund, D.M. Characterization of Voltage-Sensitive Sodium Channel Gene Coding Sequences from Insecticide-Susceptible and Knockdown-Resistant House Fly Strains. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1996, 26, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.S.; Martinez-Torres, D.; Hick, C.A.; Devonshire, A.L. Identification of Mutations in the Housefly Para-Type Sodium Channel Gene Associated with Knockdown Resistance (Kdr) to Pyrethroid Insecticides. Molec. Gen. Genet. 1996, 252, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.P.; Paul, V.L.; Slater, R.; Warren, A.; Denholm, I.; Field, L.M.; Williamson, M.S. A Mutation (L1014F) in the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel of the Grain Aphid, Sitobion Avenae, Is Associated with Resistance to Pyrethroid Insecticides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 1249–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabro, J.; Sterkel, M.; Capriotti, N.; Mougabure-Cueto, G.; Germano, M.; Rivera-Pomar, R.; Ons, S. Identification of a Point Mutation Associated with Pyrethroid Resistance in the Para-Type Sodium Channel of Triatoma Infestans, a Vector of Chagas’ Disease. Infect Genet Evol. 2012, 12, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghen, K.; Van Bortel, W.; Trung, H.D.; Sochantha, T.; Keokenchanh, K.; Coosemans, M. Knockdown Resistance in “Anopheles Vagus”, “An. Sinensis”, “An. Paraliae” and “An. Peditaeniatus” Populations of the Mekong Region. Parasites Vectors 2010, 3, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lol, J.C.; Castellanos, M.E.; Liebman, K.A.; Lenhart, A.; Pennington, P.M.; Padilla, N.R. Molecular Evidence for Historical Presence of Knock-down Resistance in Anopheles Albimanus, a Key Malaria Vector in Latin America. Parasites Vectors 2013, 6, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.X.; Sonoda, S. Resistance to Cypermethrin in Melon Thrips, Thrips Palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), Is Conferred by Reduced Sensitivity of the Sodium Channel and CYP450-Mediated Detoxification. Appl. Entomol. Zool 2012, 47, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatolos, N.; Gorman, K.; Williamson, M.S.; Denholm, I. Mutations in the Sodium Channel Associated with Pyrethroid Resistance in the Greenhouse Whitefly, Trialeurodes Vaporariorum. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinkevich, F.D.; Su, C.; Lazo, T.A.; Hawthorne, D.J.; Tingey, W.M.; Naimov, S.; Scott, J.G. Multiple Evolutionary Origins of Knockdown Resistance (Kdr) in Pyrethroid-Resistant Colorado Potato Beetle, Leptinotarsa Decemlineata. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 104, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, S.; Morishita, M. Identification of Three Point Mutations on the Sodium Channel Gene in Pyrethroid-Resistant Thrips Tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). J Econ Entomol 2009, 102, 2296–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Chang, Y.W.; Gong, W.R.; Hu, J.; Du, Y.Z. The Development of Abamectin Resistance in Liriomyza Trifolii and Its Contribution to Thermotolerance. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 2053–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.Y.; Chen, Y.; Dong, W.B.; Li, F.; Wu, S.Y. Toxicity of Indoxacarb to the Population of Liriomyza Trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae) in Sanya (China), and the Effects of Temperature and Food on Its Biological Characteristics. Tropical Plants 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantsidis, G.; O’Reilly, A.O.; Douris, V.; Vontas, J. Functional Validation of Target-Site Resistance Mutations against Sodium Channel Blocker Insecticides (SCBIs) via Molecular Modeling and Genome Engineering in Drosophila. Insect Mol. Biol. 2019, 104, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.; Jónsson, H.; Chang, D.; Der Sarkissian, C.; Ermini, L.; Ginolhac, A.; Albrechtsen, A.; Dupanloup, I.; Foucal, A.; Petersen, B.; et al. Prehistoric Genomes Reveal the Genetic Foundation and Cost of Horse Domestication. P Natl. A. Sci. 2014, 111, 5661–5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsden, C.D.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, D.; O’Brien, D.P.; Taylor, J.F.; Ramirez, O.; Vilà, C.; Marques-Bonet, T.; Schnabel, R.D.; Wayne, R.K.; Lohmueller, K.E. Bottlenecks and Selective Sweeps during Domestication Have Increased Deleterious Genetic Variation in Dogs. P Natl. A. Sci. 2016, 113, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henn, B.M.; Botigué, L.R.; Peischl, S.; Dupanloup, I.; Lipatov, M.; Maples, B.K.; Martin, A.R.; Musharoff, S.; Cann, H.; Snyder, M.P.; et al. Distance from Sub-Saharan Africa Predicts Mutational Load in Diverse Human Genomes. P Natl. A. Sci. 2016, 113, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, M. Preponderance of Synonymous Changes as Evidence for the Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution. Nature 1977, 267, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Bielawski, J.P. Statistical Methods for Detecting Molecular Adaptation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2000, 15, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.; Yang, Z.H. Estimating the Distribution of Selection Coefficients from Phylogenetic Data with Applications to Mitochondrial and Viral DNA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003, 20, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Position d | sSNPs | Nucleotide alteration | Frequency/ %e (f, g) | ||||

| MY | TS | DA | TY | JY | |||

| D Ⅰ-S1 | L145 | TTA>TTG | 21.33 (59, 16) | 11.36 (78, 10) | 13.11 (53, 8) | 16.22 (62, 12) | 13.11 (53, 8) |

| D Ⅰ-L-S56 | I290 | ATT>ATC | 27.05 (89, 33) | 18.03 (100, 22) | 23.08 (60, 18) | 15.65 (97, 18) | 12.07 (102,14) |

| S319 | TCT>TCA | 24.77 (82, 27) | 25.00 (72, 24) | 26.47 (50, 18) | 12.90 (81, 12) | 14.00 (86, 14) | |

| Y354 | TAT>TAC | - | 9.89 (82, 9) | 11.96 (81, 11) | - | - | |

| L-D Ⅰ-Ⅱ | A470 | GCG>GCT | - | 8.57 (64, 6) | - | - | - |

| L474 | TTA>TTG | - | 19.70 (53, 13) | 28.24 (61, 24) | - | 14.55 (94, 16) | |

| E496 | GAG>GAA | 27.27 (48, 18) | 23.91 (35, 11) | 32.94 (57, 28) | 17.72 (65, 14) | 14.46 (71, 12) | |

| E505 | GAA>GAG | 22.95 (47, 14) | 18.75 (39, 9) | 28.57 (55, 22) | 13.33 (52, 8) | 14.08 (61, 10) | |

| E661 | GAG>GAA | 39.18 (59, 38) | 19.18 (59, 14) | 10.00 (81, 9) | 18.95 (77, 18) | - | |

| A685 | GCC>GCA | 44.33 (54, 43) | 25.00 (51, 17) | 11.24 (79, 10) | 20.93 (68, 18) | - | |

| L733 | TTG>TTA | 54.22 (38, 45) | 21.95 (64, 18) | 11.59 (61, 8) | 22.69 (92, 27) | 10.24 (114, 13) | |

| L778 | CTC>CTT | 45.53 (67, 56) | 18.63 (83, 19) | 13.49 (109, 17) | 28.91 (91, 37) | - | |

| D Ⅱ-S1 | T814 | ACA>ACG | 45.28 (58, 48) | 20.00 (80, 20) | 19.82 (89, 22) | 29.91 (75, 32) | - |

| D Ⅱ-L-S23 | Y866 | TAC>TAT | 38.46 (56, 35) | 18.68 (74, 17) | - | 22.23 (70, 20) | - |

| D Ⅱ-S5 | N931 | AAC>AAT | 48.00 (39, 36) | 24.64 (52, 17) | 21.43 (66, 18) | 16.16 (83, 16) | 7.08 (105, 8) |

| D Ⅱ-L-S56 | S978 | TCT>TCG | 52.87 (41, 46) | 25.00 (54, 18) | 17.71 (79, 17) | 18.00 (82, 18) | 9.16 (119, 12) |

| L-D Ⅱ-Ⅲ | A1112 | GCT>GCA | 44.87 (43, 35) | 21.88 (50, 14) | 23.38 (59, 18) | 24.44 (68, 22) | 9.76 (74, 8) |

| L1231 | CTA>CTT | - | - | 11.76 (90, 12) | - | - | |

| D1232 | GAT>GAC | - | - | 12.24 (86, 12) | - | - | |

| P1282 | CCT>CCG | 35.71 (72, 40) | 20.72 (88, 23) | 28.70 (77, 31) | 27.17 (67, 25) | 11.72 (113, 15) | |

| D Ⅲ-S3 | F1372 | TTT>TTC | 16.67 (30, 6) | 7.50 (37, 3) | - | - | - |

| D Ⅲ-L-S56 | I1471 | ATC>ATT | - | 10.10 (89, 10) | - | - | - |

| Y1483 | TAT>TAC | - | 16.19 (88, 17) | - | - | - | |

| L-D Ⅳ < | H1996 | CAC>CAT | 32.43 (75, 36) | 18.52 (66, 15) | 13.21 (92, 14) | 23.15 (83, 25) | - |

| Q2006 | CAA>CAG | 72.32 (31, 81) | 80.28 (14, 57) | 85.15 (15, 86) | 76.77 (23, 76) | 94.31 (7, 116) | |

| R2011 | CGA>CGT | 72.22 (30, 78) | 82.54 (11, 52) | 85.29 (15, 87) | 76.84 (22, 73) | 93.97 (7, 109) | |

| G2022 | GGT>GGC | - | 10.00 (54, 6) | 6.06 (93, 6) | - | - | |

| G2033 | GGG>GGT | 73.63 (24, 67) | 91.94 (5, 57) | 91.86 (7, 79) | 81.94 (13, 59) | 94.44 (6, 102) | |

| A2038 | GCG>GCT | - | 7.04 (66, 5) | - | - | - | |

| G2040 | GGA>GGT | - | 8.33 (66, 6) | - | - | - | |

| A2050 | GCC>GCT | 64.41 (21, 38) | 94.29 (4, 66) | 88.57 (8, 62) | 81.36 (11, 48) | 93.40 (7, 99) | |

| Position d | nsSNPs | Nucleotide alteration | Frequency/ % h (i, j) | ||||

| MY | TS | DA | TY | JY | |||

| D Ⅱ-L-S45 | M922T | ATG>ACG | 58.46 (27, 38) | 62.07 (22, 36) | 72.09 (24, 62) | 80.58 (20, 83) | 90.91 (11, 110) |

| D Ⅱ-S5 | T933I | ACA>ATA | - | 8.57 (64, 6) | - | - | - |

| D Ⅱ-S6 | L1018F | CTT>TTT | 100.00 (0, 64) | 100.00 (0, 71) | 100.00 (0, 90) | 100.00 (0, 102) | 100.00 (0, 126) |

| L-D Ⅱ-Ⅲ | Q1285H | CAA>CAC | - | - | 80.00 (18,72) | - | 96.52 (4,111) |

| D Ⅳ-S6 | V1845I | GTT>ATA | 36.54 (99,57) | 86.27 (14,88) | 80.00 (18,72) | 79.55 (18,70) | 96.52 (4,111) |

| L-D Ⅳ < | D2036E | GAC>GAA | - | 6.94 (67,5) | - | - | - |

| Primers | Sequence | Product length a (b, c) (bp) |

Annealing Temperature ( ℃) |

| LT-1F | ATGACAGAAGATTCCGACTCGA | 288 (215, 73) | 47.5 |

| LT-1R | TTCCGGCGGGAAGCTGCCCTGCAAT | ||

| LT-2F | GGTCCACAACCGGATCCTAC | 1671 (188, 1483) | 39.0 |

| LT-2R | TGGCTACACGACGTATTGGA | ||

| LT-3F | TCCAATACGTCGTGTAGCCA | 2811 (236, 2575) | 41.5 |

| LT-3R | AAGTCCAGCCAATTCCATGCA | ||

| LT-4F | GTGATGGCACGAGGTTTCAT | 1982 (713, 1269) | 40.0 |

| LT-4R | TCGTCATACGACATGGCAAC | ||

| LT-5F | CGAATTGCAAAAGAAAGCCGA | 3701 (565, 3136) | 41.5 |

| LT-5R | TTCAGACATCGGTGTGACGG | ||

| LT-6F | CCGTCACACCGATGTCTGAA | 4563 (610, 3953) | 44.5 |

| LT-6R | TCGAAGACAATTAATGACACCCA | ||

| LT-7F | TGGGTGTCATTAATTGTCTTCGA | 1898 (697, 1201) | 45.0 |

| LT-7R | TGGACAAAAGCAAGGCCAAG | ||

| LT-8F | TGGCCTTGCTTTTGTCCAATT | 4357 (796, 3561) | 42.0 |

| LT-8R | AAATTGCCCCATCCTTGCCA | ||

| LT-9F | GGCAATTTACGACTGAAAACTTTTCA | 1008 (225, 783) | 49.0 |

| LT-9R | ATACACCGCAAACCCGAGAG | ||

| LT-10F | CTGCCGCAAAGACCCATACT | 4363 (301, 4062) | 39.0 |

| LT-10R | GAACCAGCGCATTAACGACG | ||

| LT-11F | CGTCGTTAATGCGCTGGTTC | 4544 (584, 3960) | 39.5 |

| LT-11R | ACTATTGCTTGTGGTCGCCA | ||

| LT-12F | CGACCACAAGCAATAGTTTTTGA | 3583 (327, 3256) | 44.5 |

| LT-12R | CAGCACACGACCGACTTTTG | ||

| LT-13F | GTGTGGTACGTGTGGCAAAA | 2247 (1274, 973) | 38.5 |

| LT-13R | TCAGACATCCGCCGTGCGTG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).