1. Introduction

Nutritional status is a determinant of surgical outcomes, particularly in patients undergoing major abdominal procedures such as laparotomies¹. The prognostic nutritional index (PNI), a simple yet effective tool calculated using serum albumin levels and total lymphocyte count, has emerged as a valuable biomarker for assessing preoperative nutritional status and predicting postoperative morbidity and mortality²˒³. While its prognostic significance has been well established in elective surgical settings⁴, its utility in the context of emergency laparotomies remains underexplored and less well defined.

Nutrition plays a fundamental role in determining surgical outcomes across both elective and emergency settings. Malnutrition, reported in up to 30–50% of hospitalized surgical patients, is independently associated with impaired wound healing, increased infectious complications, prolonged hospitalization, and increased mortality⁵˒⁶˒²². In elective surgery, patients benefit from structured preoperative optimization, including nutritional interventions that have been shown to improve immune competence, reduce complications, and shorten recovery⁷. In contrast, emergency surgical patients often present acutely ill patients, with systemic inflammation or sepsis, limited physiological reserves, and no opportunity for nutritional optimization, rendering even mild nutritional deficits clinically significant⁸˒⁹. Research has consistently shown that poor nutritional status, regardless of the surgical setting, contributes to adverse outcomes and increased postoperative morbidity¹⁰.

Several tools have been developed to assess nutritional risk in surgical patients, including the Body Mass Index (BMI), the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST), the Nutritional Risk Index (NRI), the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI), and the Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score¹–¹³˒¹⁷. While useful in elective care, many of these require subjective inputs, weight history, or complex biochemical data that are often unavailable or unreliable in acute emergencies. BMI, for example, fails to capture muscle wasting or sarcopenic obesity — BMI does not distinguish between lean and fat mass and may overlook sarcopenic obesity, where muscle depletion occurs despite normal or high BMI²¹. Moreover, the MUST and NRI rely on prior weight changes or dietary intake assessments that may not be feasible in urgent settings¹⁴˒¹⁸. The CONUT and GNRI scores incorporate serum albumin and lymphocyte count but also depend on cholesterol or anthropometric data, limiting their practicality in time-sensitive emergency environments¹⁵˒¹⁹.

The prognostic nutritional index (PNI) was therefore chosen for this study because it provides a simple, objective, and reproducible measure based solely on two routinely available laboratory parameters—the serum ALB concentration and total lymphocyte count. PNI integrates both nutritional reserve and immune competence, offering insight into the interplay between metabolic and inflammatory responses to surgical stress²˒³˒¹⁵˒²⁰. It has been validated across diverse surgical populations, including gastrointestinal, hepatobiliary, and oncologic surgeries, and consistently correlates with postoperative morbidity, infectious complications, and long-term survival⁴˒⁶˒⁷. Compared with other indices, the PNI is easier to calculate, more widely studied, and suitable for use in emergency settings, making it an appealing and evidence-based choice for preoperative nutritional risk assessment.

Emergency laparotomy represents one of the most high-risk and resource-intensive emergency general surgical procedures and is often performed in patients with acute intra-abdominal sepsis, bowel obstruction, or perforation. Mortality rates following emergency laparotomy remain substantial, typically ranging from 10–30%, with morbidity rates exceeding 40% in some cohorts⁸˒⁹˒²³. These poor outcomes are attributed to the combination of physiological derangement, advanced age, sepsis, and preexisting comorbidities at presentation¹⁶. Despite advances in perioperative care and the establishment of national quality improvement initiatives such as the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) in the UK, outcome variability persists¹⁰˒¹¹. Nutritional status, often overlooked in emergency settings, may be an important yet modifiable determinant of prognosis in this high-risk population.

This study aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of the PNI in patients undergoing emergency and elective laparotomies by analysing its associations with postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and overall clinical outcomes. By identifying differences in nutritional risk profiles and surgical outcomes between these two groups, we sought to determine whether the PNI should be routinely incorporated into preoperative assessment protocols to enhance surgical planning and optimize patient recovery.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This was a retrospective observational study conducted at a single district general hospital in England. The study analysed patient data over a five-year period, from the 01st of January 2019 to the 31st of December 2023. This study focused on emergency laparotomies performed for upper and lower gastrointestinal tract pathologies.

2.2. Ethical Approval and Consent

This audit was registered with the Clinical Governance Team at the George Eliot NHS Trust, UK (ID: 1343). In accordance with national guidance, formal Research Ethics Committee approval was not required for this retrospective observational audit. This was confirmed using the UK Health Research Authority’s

“Is my study research?” online decision tool (

http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research).

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patient data were anonymised prior to analysis to ensure confidentiality. Given the retrospective nature of the study, individual patient consent was not required, and institutional approval was obtained in line with local governance protocols.

2.3. Study Participation

The study included patients over eighteen years of age who underwent either emergency open or laparoscopic conversion to open abdominal surgery within the specified timeframe. Patients who underwent laparoscopic procedures without conversion to open surgery or whose records were incomplete were excluded from the analysis.

2.4. Data Collection

The prospectively maintained local copy of the NELA database was queried to identify the patient sample and relevant data. Demographic data, such as age and sex, and preoperative baseline patient characteristic data, such as American Society of Anaesthesiologist (ASA) grade, clinical frailty score and comorbidities, were collated. Preoperative NELA mortality scores, hemodynamic parameters (tachycardia and hypotension) and the presence of sepsis were also recorded. Intraoperative details, such as the name of the procedure and stoma formation, were obtained. Data on postoperative outcomes were also obtained. The date of discharge and date of admission were used to calculate the length of stay. Inpatient complications were categorized on the basis of the Clavien–Dindo system and summarized as the presence or absence of complications. Thirty-day readmissions, inpatient mortality rates and three-year all-cause mortality rates were also identified. Utilization of critical care was identified, including both planned and unplanned admissions to level 2 or 3 care. The most recent preoperative serum ALB and lymphocyte count data were obtained from electronic patient records. The prognostic nutritional index (PNI) was calculated according to the formula described by Pinato et al.; serum albumin, g/L) + (0.005 × blood lymphocyte count, unit/µL) (3). Patients were categorized as malnourished (PNI <50) or not malnourished (PNI ≥50). All the data were collated and tabulated via Excel (Microsoft, Washington, USA).

2.5. Data Analysis

Comparative analyses were performed to evaluate the associations between nutritional status (malnourished vs. not malnourished) and surgical outcomes. Statistical analyses were conducted via IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were tested for normality and are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Differences between groups were assessed via the Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric continuous variables. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and comparisons were made via the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to identify independent perioperative predictors of the four major postoperative outcomes: stoma formation, prolonged hospital stay (≥12 days), 30-day readmission, and mortality (in-hospital or during follow-up). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to assess three-year all-cause mortality, with differences between nutritional groups compared via the log-rank test.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 482 patients who underwent emergency laparotomy between January 2019 and December 2023 were included. The cohort comprised 57% males, with a median age of 68 years (IQR 54–76). On the basis of the prognostic nutritional index (PNI), 318 patients (66%) were classified as malnourished (PNI < 50), and 164 (34%) were classified as not malnourished (PNI ≥ 50). The baseline characteristics were comparable in terms of age and sex distribution (p = 0.489 and 0.110, respectively). However, malnourished patients had significantly higher ASA grades (3–5) (p < 0.001), greater frailty (≥5) (p = 0.028), and a greater comorbidity burden (70% vs 30%, p < 0.001) (

Table 1).

Baseline characteristics were compared between malnourished and non-malnourished patients via the chi-square test. ASA = American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification. PNI = Prognostic nutritional index

3.2. Perioperative Characteristics and Patient Outcomes

Preoperative factors revealed that malnourished patients were more likely to present with hypotension (p = 0.010), although no significant associations were observed for tachycardia, sepsis, or predicted NELA mortality (all p > 0.05) (

Table 2). Surgical interventions, including colorectal resection, small bowel resection, and adhesiolysis, were similarly distributed across groups (p = 0.873). However, malnourished patients were significantly more likely to require stoma formation (81% vs 19%, p = 0.002) (

Table 3).

Postoperative outcomes revealed a significantly longer hospital stay among malnourished patients. The median length of stay for patients with a PNI < 50 was 14 days (IQR 9–21), whereas it was 8 days (IQR 5–13) for those with a PNI ≥ 50; this difference was statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U = 17 892.0, p < 0.001). Overall, 75% of the malnourished patients experienced prolonged hospitalization (≥12 days), whereas 25% of the non-malnourished patients experienced prolonged hospitalization (p < 0.001).

While the incidence of postoperative complications was not significantly different between the groups (p = 0.992), malnourished patients had higher rates of 30-day readmission (88% vs 13%, p = 0.026) and three-year all-cause mortality (74% vs 26%, p = 0.044) (

Table 4).

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

The overall multivariate model was statistically significant (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.080, F = 1.13, p = 0.040), indicating that the collective influence of demographic, physiological, and nutritional factors was meaningful. The model showed a moderate effect size (Partial η² = 0.396) and excellent statistical power (1 − β = 1.000). After adjustment for potential confounders, a low prognostic nutritional index (PNI < 50) was the strongest independent predictor of adverse outcomes. Malnourished patients were significantly more likely to undergo stoma formation (p = 0.002) and have a prolonged hospital stay (p < 0.001). Higher ASA grades (3–5) were independently associated with both stoma formation (p = 0.031) and mortality (p = 0.048), whereas comorbidities were related to extended hospitalization (p = 0.008). Frailty (≥5) was a significant predictor of 30-day readmission (p = 0.041), and hypotension at presentation (SBP < 100 mmHg) was associated with increased mortality (p = 0.010). Roy’s largest root test supported the overall robustness of the model (F = 1.57, p = 0.002, partial η² = 0.473). These results suggest that nutritional impairment is associated with frailty, physiological instability, and operative stress, leading to poorer recovery and an increased risk of death following emergency laparotomy. (

Table 5)

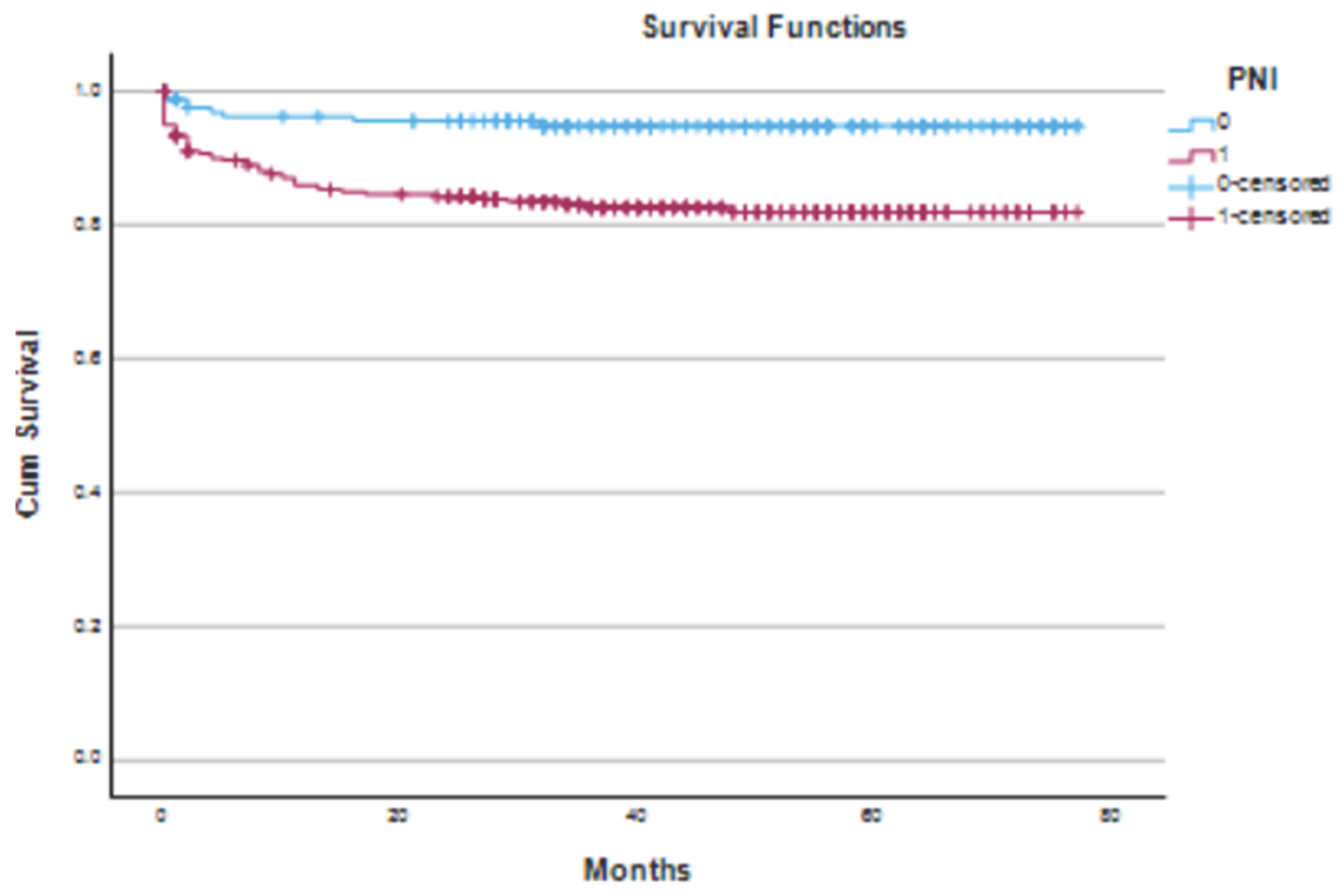

3.4. Survival Analysis

The median follow-up was 43 months (IQR 28–60). During this period, 61 deaths (12.7%) occurred. Mortality was greater in the malnourished group (74% vs. 26%; χ² = 4.01; p = 0.04). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis confirmed that patients with a PNI < 50 had significantly lower cumulative survival than those with a PNI ≥ 50 (log-rank χ² = 13.55, p < 0.01) (

Figure 1).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing cumulative survival between malnourished (PNI < 50) and non-malnourished (PNI ≥ 50) patients following emergency laparotomy. The blue curve represents patients with a normal PNI, whereas the red curve represents malnourished patients. Censored observations are marked with “+”. A statistically significant difference in survival was observed between the groups (log-rank χ² = 13.55, p < 0.01).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that malnutrition, as assessed by the prognostic nutritional index (PNI), was highly prevalent in patients undergoing emergency laparotomy and was significantly associated with adverse short- and long-term clinical outcomes. Notably, malnourished patients experienced longer hospital stays and were more likely to require stoma formation. Although unadjusted analyses indicated higher 30-day readmission rates and 3-year all-cause mortality rates in the malnourished cohort, these associations did not persist after multivariate adjustment, suggesting that malnutrition is a key but not isolated determinant of poor outcomes in this high-risk population.

This study underscores the critical prognostic relevance of the prognostic nutritional index (PNI) in patients undergoing emergency laparotomy, revealing a strikingly high prevalence of malnutrition (66%) within this cohort. Malnourished patients, as defined by a PNI <50, presented a markedly elevated burden of physiological compromise, as evidenced by significantly higher ASA and frailty scores, increased comorbidities, and more frequent hypotensive presentations. These factors collectively reflect the intricate interplay between nutritional deficiency and systemic vulnerability in the emergency surgical setting.

Our findings align with previous evidence underscoring the predictive value of the PNI in surgical patients. Originally described by Onodera et al., the PNI integrates the serum ALB concentration and lymphocyte count to provide a reliable surrogate of both nutritional and immune status¹. Numerous studies have validated its prognostic utility in elective colorectal, gastric, and hepatobiliary surgeries, where a lower PNI is correlated with increased postoperative morbidity and mortality²˒³. However, few studies have examined its role in emergency surgical settings, which are typified by acute physiological derangement and lack preoperative optimization. Lee et al. reported a similar association between a low PNI and an increased risk of postoperative complications in emergency abdominal surgery⁴, reinforcing the findings of the present study.

The current study builds on this limited body of work by evaluating a large, unselected cohort of emergency laparotomy patients over five years. The significant association between a low PNI and prolonged hospitalization observed here likely reflects both the physiological burden of malnutrition and the complexity of managing surgical complications in nutritionally depleted individuals. Moreover, the strong association between malnutrition and increased stoma formation may suggest a more cautious surgical approach in high-risk patients or reflect intraoperative findings such as bowel ischemia or contamination, which are more common in compromised hosts.

From a mechanistic perspective, malnutrition impairs collagen synthesis, delays wound healing, compromises immune defense, and reduces physiological reserves—factors critical in the postoperative period⁶. Emergency surgery patients often present in catabolic states with underlying sepsis or organ dysfunction, making even marginal nutritional deficits clinically significant. Despite these risks, current emergency surgical pathways often overlook routine nutritional screening, a gap highlighted by our data.

Interestingly, while malnourished patients presented increased unadjusted mortality and readmission rates, these outcomes were not independently associated with the PNI after controlling for confounders. This finding is consistent with studies demonstrating that, while the PNI is a valuable marker of perioperative vulnerability, it must be interpreted alongside clinical indicators such as the ASA score, frailty, and comorbid burden⁵. Notably, frailty and ASA score were also significantly associated with malnutrition in our cohort, underscoring the interconnected nature of these risk factors.

These findings have important clinical and policy implications. First, they suggest that simple preoperative metrics such as the PNI should be incorporated into early risk stratification tools such as the NELA calculator, which currently emphasizes physiological and operative factors but lacks nutritional parameters⁷. Second, the results argue for the incorporation of prompt nutritional interventions—such as early enteral feeding or targeted immunonutrition—into perioperative pathways, even in acute surgical settings. Several randomized studies on elective surgery have shown that such interventions reduce infectious complications and shorten the length of stay⁸˒⁹.

Finally, this study contributes to the growing consensus that malnutrition is not merely a consequence of chronic illness but also a modifiable risk factor in surgical care. As emphasized in recent enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) guidelines, routine nutritional assessment and optimization should be standard even in emergent settings where feasible¹⁰. Malnutrition not only affects physiological resilience but also contributes to increased length of stay, postoperative complications, and healthcare costs²⁴. Hospital malnutrition remains a pervasive issue globally, emphasizing the need for systematic nutritional screening and intervention in all surgical pathways²⁵.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design and single-center scope, which may limit its generalizability. Additionally, while the PNI is simple and reproducible, it does not capture all dimensions of malnutrition, such as micronutrient status, sarcopenia, or caloric intake. Prospective, multicentre trials incorporating comprehensive nutritional assessments are needed to validate and extend these findings.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes the prognostic nutritional index (PNI) as a powerful predictor of outcome in patients undergoing emergency laparotomy, revealing that malnutrition—present in nearly two-thirds of this cohort—is both common and clinically consequential. Patients with a low PNI (<50) presented greater physiological compromise, reflected by higher ASA and frailty scores, more frequent hypotensive presentations, and increased comorbidity burden. These findings highlight the intrinsic link between poor nutritional status and reduced physiological resilience in acute surgical illness. Although operative strategies are similar across nutritional groups, malnourished patients face significantly longer hospital stays and are more likely to require stoma formation, underscoring the tangible impact of malnutrition on recovery and surgical complexity. While increased readmission and mortality rates did not remain statistically significant after adjustment, the PNI nevertheless emerged as a sensitive marker of overall clinical deterioration rather than an independent predictor of poor outcome.

Importantly, these results demonstrate that a simple, readily available blood-based metric can meaningfully inform perioperative risk assessment in emergency surgery, a field traditionally limited by the inability to optimize patients preoperatively. Integrating the PNI into existing frameworks, such as the NELA calculator, could enhance early decision-making, guide intraoperative caution, and prompt timely nutritional interventions. In an era emphasizing precision medicine and value-based care, the identification of malnutrition as a modifiable determinant of surgical risk is both a clinical and ethical priority. Future prospective studies should assess whether PNI-guided perioperative nutrition strategies can reduce complications, shorten hospitalization, and improve survival. Until such evidence is available, routine incorporation of PNI assessment into emergency laparotomy pathways offers a low-cost, high-yield opportunity to recognize nutritional vulnerability early and tailor management accordingly. By doing so, we can shift the paradigm of emergency surgical care from reactive to proactive, addressing malnutrition not as an inevitable consequence of illness but as a critical, modifiable target for improving outcomes.

Author Contributions

SR and KW led and designed this project. SR and SV conducted the literature review, collated the data and drafted the manuscript. KW performed the data analysis and edited and finalized the manuscript. He is the corresponding author. SR and LA were instrumental in data collection. SY, CK, BP, AN, AH, MIA and KM assisted with data interpretation and reviewed and edited the manuscript. As the clinical lead and head of department, KM provided overall leadership, guidance and supervision for this project. He oversaw and provided valuable input during all stages of this project.

Funding

Institute of Biomedical Research, College of Medical and Dental Science, University of Birmingham, Vincent Drive, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT.

Ethical Approval

This audit was registered and approved by the clinical governance team at George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust (ID: 1343). Research ethics committee approval was not required for this audit, and this was confirmed via the UK, Health Research Authority “Is my study research?” online decision tool (

http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research).

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data and results included in this article have been published along with the article and its supplementary information files.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the consultant body of the colorectal surgery department at the Geroge Eliot Hospital NHS Trust (SWFT). We are grateful for the support from our local National Emergency Laparotomy Audit team for their support in identifying patients.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Mohri Y, Inoue Y, Tanaka K, Hiro J, Uchida K, Kusunoki M. Prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative outcome in colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37(11):2688-92. [CrossRef]

- Sun K, Chen S, Xu J, Li G, He Y. The prognostic significance of the prognostic nutritional index in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(9):1537-49. [CrossRef]

- Pinato DJ, North BV, Sharma R. A novel, externally validated inflammation-based prognostic algorithm in hepatocellular carcinoma: the prognostic nutritional index (PNI). Br J Cancer. 2012;106(8):1439-45. [CrossRef]

- Lee JY, Kim HI, Kim YN, et al. Clinical significance of the prognostic nutritional index for predicting short- and long-term surgical outcomes after gastrectomy: a retrospective analysis of 7,781 gastric cancer patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(18):e3539. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Gao P, Chen X, et al. The prognostic nutritional index is a predictive indicator of prognosis and postoperative complications in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(8):1176-82. [CrossRef]

- Chan AWH, Chan SL, Wong GLH, et al. Prognostic Nutritional Index predicts tumor recurrence of very early/early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(13):4138-48. [CrossRef]

- Ke M, Xu T, Li N, Ren Y, Shi A, Lv Y. Prognostic nutritional index predicts short-term outcomes after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. Oncotarget. 2016;7(49):81611-20. [CrossRef]

- Saunders DI, Murray D, Pichel AC, Varley S, Peden CJ; UK Emergency Laparotomy Network. Variations in mortality after emergency laparotomy: first report of the UK Emergency Laparotomy Network. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109(3):368-75. [CrossRef]

- Vester-Andersen M, Lundstrøm LH, Møller MH, et al. Mortality and postoperative care pathways after emergency gastrointestinal surgery: a population-based cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112(5):860-70. [CrossRef]

- Oliver CM, Walker E, Giannaris S, Grocott MPW, Moonesinghe SR; NELA Investigators. Organisational factors and mortality after an emergency laparotomy: multilevel analysis of 39,903 NELA patients. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121(6):1346-56. [CrossRef]

- NELA Project Team. Eighth Patient Report of the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (Dec 2020–Nov 2021). London: Royal College of Anaesthetists; 2023.

- Kudou K, Kajiwara S, Motomura T, et al. Risk factors of postoperative complication and hospital mortality after colorectal perforation surgery. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2024;8(2):118-25. [CrossRef]

- Ashmore DL, Dowswell G, Shingler G, et al. Identifying malnutrition in emergency general surgery: a scoping review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2023;36(6):2383-97. [CrossRef]

- Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS): a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):292-8. [CrossRef]

- Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, et al. ESPEN guideline: clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(3):623-50. [CrossRef]

- Cederholm T, Jensen GL, Correia MITD, et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition: a consensus report. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, Stanga Z; ESPEN Working Group. Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on analysis of controlled trials. Clin Nutr. 2003;22(3):321-36. [CrossRef]

- Elia M; Malnutrition Advisory Group (MAG) of BAPEN. The MUST Report: Nutritional Screening of Adults – A Multidisciplinary Responsibility. Redditch (UK): BAPEN; 2003. Available at: https://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/must/must-report.pdf.

- Bouillanne O, Morineau G, Dupont C, et al. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI): a new index for at-risk elderly medical patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(4):777-83. [CrossRef]

- Levitt DG, Levitt MD. Human serum albumin homeostasis: a new look at synthesis, catabolism, excretion, and clinical value. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:229-55. [CrossRef]

- Prado CMM, Heymsfield SB. Lean tissue imaging: a new era for nutritional assessment and intervention. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(8):940-53. [CrossRef]

- Hiesmayr M, Schindler K, Pernicka E, et al. Decreased food intake is a risk factor for mortality in hospitalised patients: the NutritionDay survey 2006. Clin Nutr. 2009;28(5):484-91. [CrossRef]

- Aitken RM, Partridge JSL, Oliver CM, et al. Older patients undergoing emergency laparotomy: observations from the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) years 1–4. Age Ageing. 2020;49(4):656-63. [CrossRef]

- Correia MITD, Waitzberg DL. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs: multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr. 2003;22(3):235-9. [CrossRef]

- Barker LA, Gout BS, Crowe TC. Hospital malnutrition: prevalence, identification and impact on patients and the healthcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(2):514-27. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).