1. Introduction

The global burden of childhood cancer continues to rise. In 2022, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) estimated approximately 275,000 new cancer cases among children and adolescents aged 0–19 years worldwide [

1]. In Saudi Arabia, the 2014 Saudi Cancer Registry reported 822 new pediatric cancer cases, and more recent national data indicate an incidence of 15.3 per 100,000 among individuals under 20 years of age [

2]. Over recent decades, survival outcomes have markedly improved, with overall 5-year survival rising from approximately 40% in the 1970s to more than 80% in 2017 [

3]. Despite these advances, major global disparities remain: more than 90% of children with cancer in high-income countries achieve long-term cure, compared with less than 30% in low- and middle-income countries [

4].

Improvements in chemotherapy, multimodal treatment, and supportive care have significantly enhanced outcomes for pediatric oncology patients [

5]. However, the treatment course remains highly intensive, and affected children are vulnerable to life-threatening complications. Immunosuppression from both underlying disease and therapy contributes to severe infections, respiratory compromise, and organ dysfunction, often necessitating critical care support. Up to 38% of pediatric oncology patients require at least one pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission during their treatment course, most commonly within the first three years after diagnosis [

6,

7].

PICU admission in this population is typically precipitated by respiratory failure, sepsis, multiorgan dysfunction, or disease-specific complications. Hematologic malignancies, in particular, carry a higher risk due to greater degrees of immunosuppression and treatment intensity [

8,

9,

10]. The need for mechanical ventilation or vasoactive support is consistently associated with worse outcomes and higher mortality [

10,

11,

12]. In low- and middle-income countries, PICU mortality among pediatric oncology patients ranges from 27.8% to over 51% [

11,

12,

13], whereas high-resource settings report significantly lower mortality rates. For example, a recent multicenter Italian cohort described a mortality rate of 15%, illustrating the impact of resource availability and critical care capacity [

14]. Severity-of-illness scoring tools such as the Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) score correlate with observed mortality and are widely used to assess physiologic derangement at PICU admission [

7,

8].

Despite the expansion of pediatric oncology services in Saudi Arabia and increasing numbers of newly diagnosed childhood cancer cases, the outcomes of pediatric oncology patients requiring PICU admission have not been systematically examined. Published data remain scarce, and the burden of critical illness, patterns of PICU utilization, and predictors of mortality in this population are not well characterized at the national level.

To address this gap, we evaluated PICU admission rates, clinical characteristics, critical care interventions, and mortality outcomes among pediatric oncology patients admitted to a tertiary care PICU in Saudi Arabia between 2015 and 2021. Our objective is to delineate the burden of critical illness in this population and identify predictors of mortality to inform improvements in supportive and critical care delivery.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) of King Abdullah Specialized Children’s Hospital (KASCH), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. KASCH is a tertiary referral center that provides healthcare services to approximately 1.15 million eligible Saudi National Guard personnel, employees, and their families (9). Electronic medical records from January 2015 to December 2021 were reviewed for data extraction.

Study Population

Pediatric oncology patients aged <14 years admitted to the PICU during the study period were eligible for inclusion. Oncology patients were defined as those with a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of hematologic malignancy or solid tumor. Patients admitted solely for postoperative monitoring were excluded.

Data Collection and Study Variables

Demographic and clinical variables included age at PICU admission, sex, source of admission (oncology ward, emergency department, or other), presence of comorbidities, prior oncologic therapies, and type of treatment received before PICU admission.

Underlying malignancies were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of childhood cancers and grouped into hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. Hematologic malignancies included B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Solid tumors included neuroblastoma, intracranial solid tumors such as medulloblastoma and astrocytoma, bone tumors including osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma, kidney tumors such as Wilms tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, and other solid tumors.PICU-related variables included reason for admission, requirement and duration of mechanical ventilation, inotropic support, renal replacement therapy, and Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) score (7,8).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were PICU and post-PICU mortality and length of PICU stay.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics. Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), depending on their distribution, assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Comparisons between groups (survivors vs. non-survivors; hematologic vs. solid malignancies) were performed using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression was conducted to identify predictors of PICU mortality. Variables with p < 0.05 were entered into a multivariable Cox model with clustered standard errors to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using log–log plots and the “estat phtest” command in STATA.

Survival probability was assessed using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical Approval

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) (Approval No.: RC18.334R). All patient data were de-identified to maintain confidentiality.

3. Results

Incidence and Characteristics of PICU Admission

During the study period, 126 pediatric oncology patients were admitted to the PICU, representing an overall PICU admission incidence of 42.1% among newly diagnosed oncology patients. Of these, 100 patients (79%) were admitted once, while 26 patients (21%) required multiple admissions.

The median age at PICU admission was 6 years (IQR 3–11), and 59% were female. Most admissions originated from the oncology ward (57%), followed by the emergency department (26.1%). Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

Approximately one-third (33%) of patients had preexisting comorbidities, most commonly genetic disorders (23%). Prior to PICU admission, 70% of patients had received therapeutic interventions, with chemotherapy (71%) being the most frequent modality.

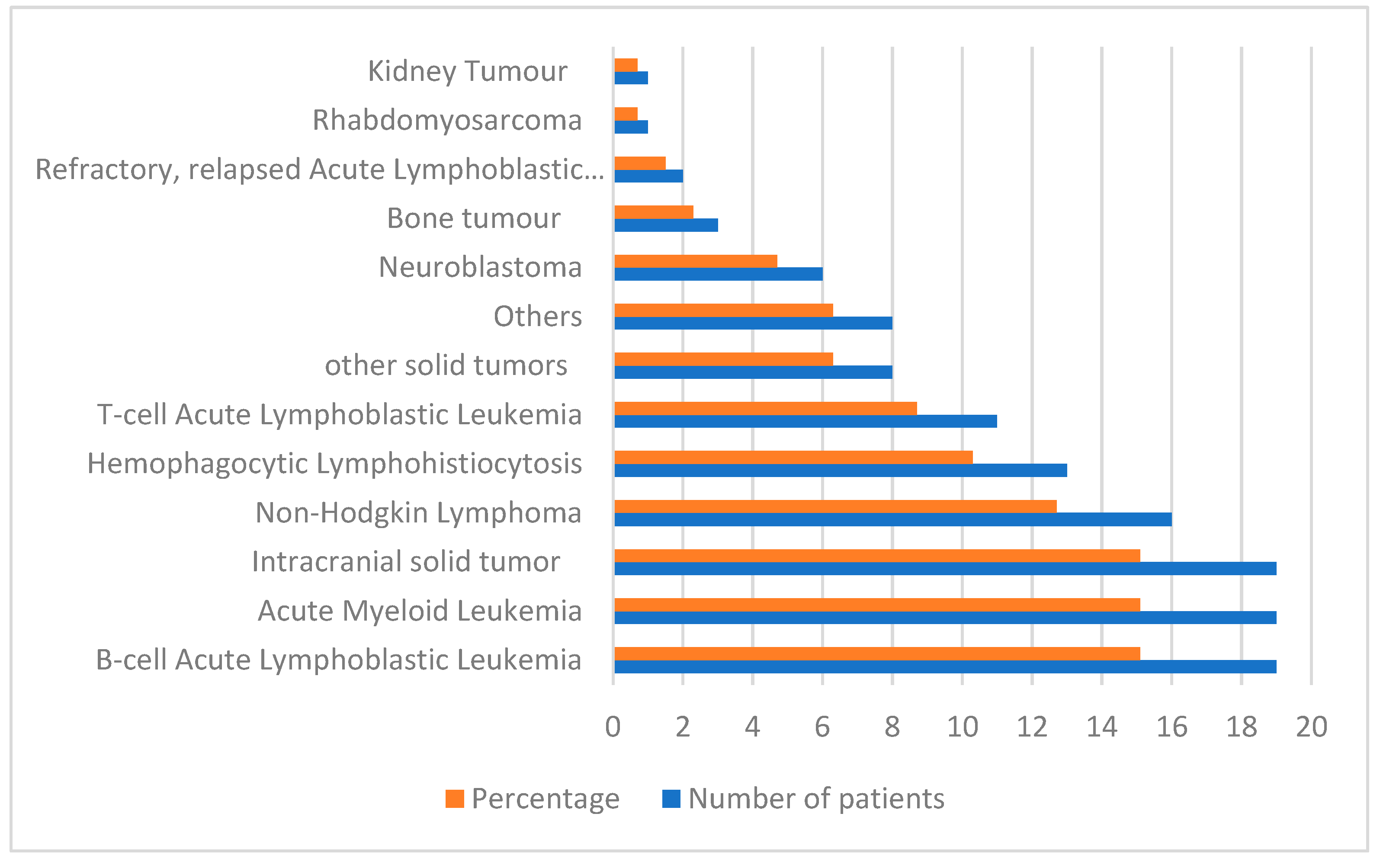

The leading reasons for PICU admission were sepsis (41%) and respiratory failure (21%). Hematologic malignancies accounted for 63% of all admissions (

Figure 1), with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) representing 15% of PICU admissions.

PICU Interventions and Organ Dysfunction

A total of 50 patients (39%) developed organ dysfunction during their PICU stay. Among them, 68% experienced single-organ failure, whereas 32% developed multiorgan failure.

In terms of intensive care interventions:

Mechanical ventilation was required in 35% of patients.

Inotropic support was administered to 30% of patients.

A smaller proportion required renal replacement therapy.

Details of all PICU interventions and outcomes are presented in

Table 2.

Study Outcomes

Overall, 25 patients (19%) died during the study period. Among these, 13 deaths (52%) occurred during the PICU admission, while 12 deaths (48%) occurred after PICU discharge. Survival outcomes according to baseline characteristics are shown in

Table 3.

Compared with survivors, non-survivors had:

A higher prevalence of comorbidities (48% vs. 26%; p = 0.039)

Greater need for mechanical ventilation (76% vs. 25%; p < 0.001)

Increased use of inotropic support (52% vs. 24%; p = 0.008)

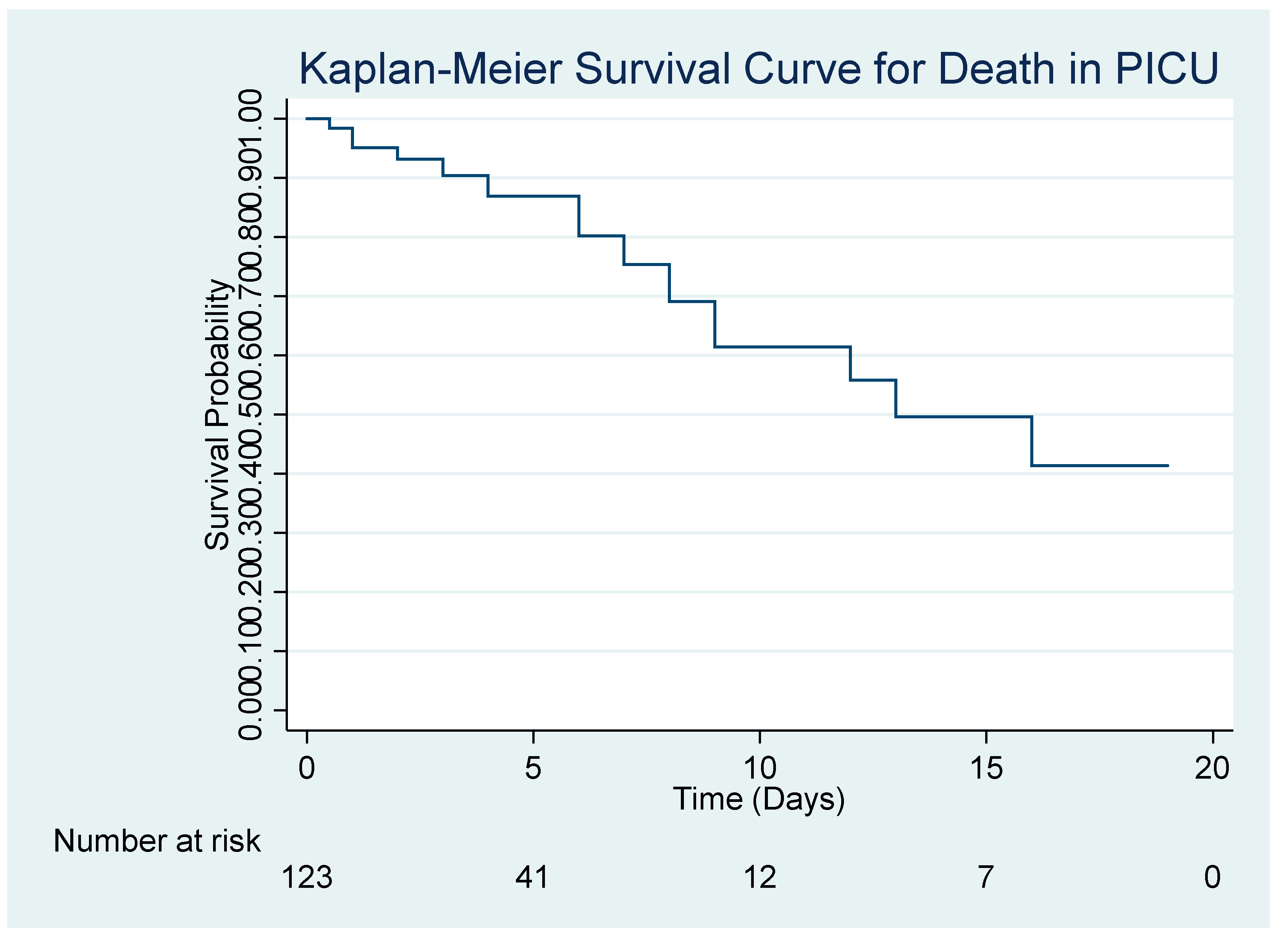

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve demonstrating survival probability over time is presented in

Figure 2.

Predictors of Mortality

Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards analyses are shown in

Table 4. Factors significantly associated with mortality included:

Comorbidities (HR: 2.10; 95% CI: 1.00–4.40)

Prior therapeutic interventions before PICU admission (HR: 2.70; 95% CI: 1.04–6.9)

Mechanical ventilation (HR: 3.0; 95% CI: 1.22–7.39)

*Adjusted for significant variables in univariate analysis.

After multivariable adjustment:

Prior therapeutic interventions remained a strong independent predictor of mortality (HR: 3.19; 95% CI: 1.24–8.19).

Mechanical ventilation also remained independently associated with increased mortality (HR: 3.02; 95% CI: 1.16–7.60).

PRISM score was not independently associated with mortality.

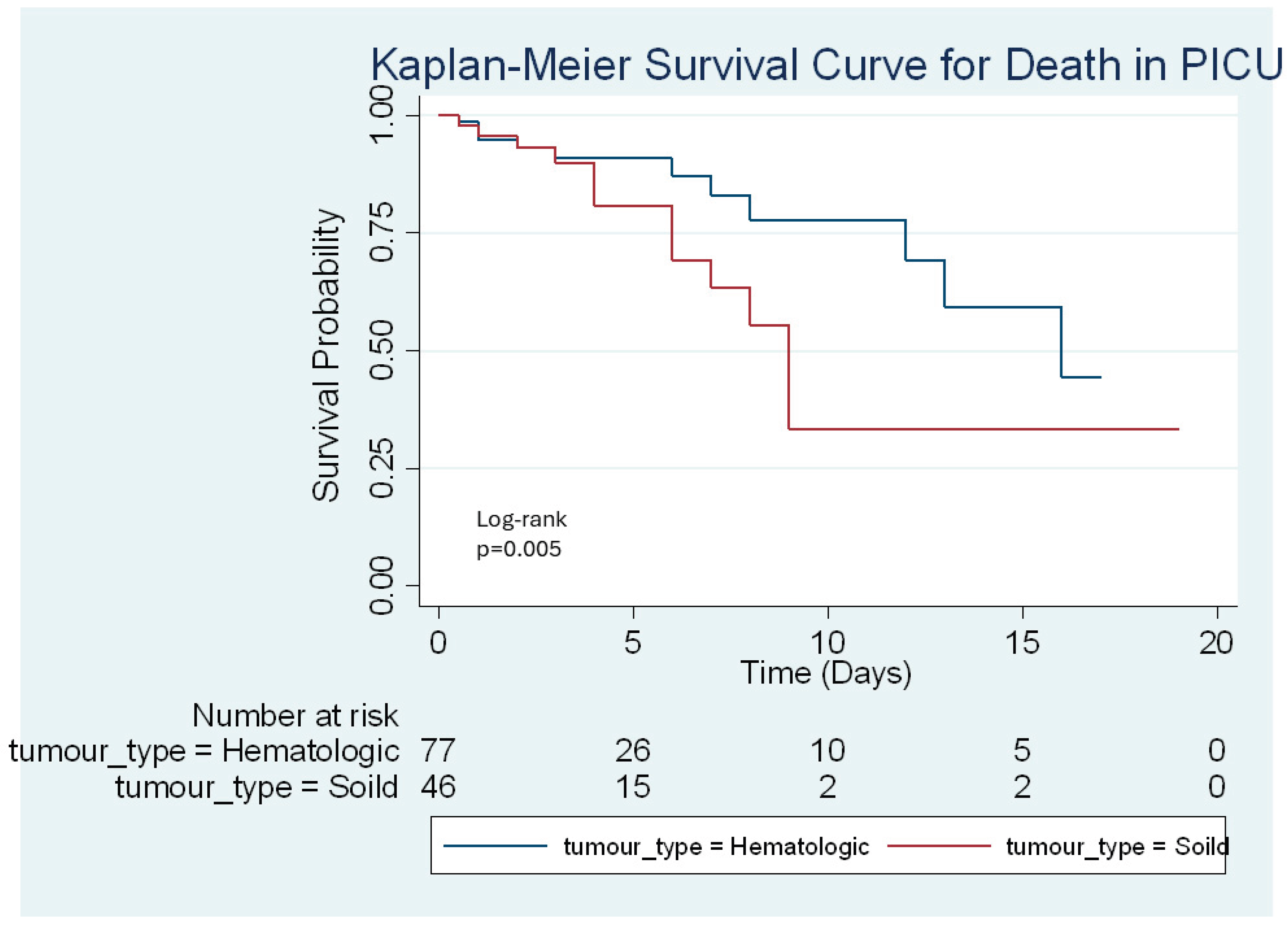

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates stratified by tumor type (hematologic vs. solid) showed no significant difference in mortality (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the clinical characteristics, PICU interventions, and outcomes of pediatric oncology patients admitted to a tertiary care PICU in Saudi Arabia. Sepsis and respiratory failure were the most frequent indications for PICU admission, consistent with international findings that identify infection-related complications as leading drivers of critical illness in immunocompromised children (1,2). Hematologic malignancies constituted the majority of cases, mirroring global patterns where these diagnoses are associated with greater treatment intensity and vulnerability to severe complications (3,4).

Nearly 40% of patients in this cohort experienced organ dysfunction, and more than one-third required mechanical ventilation or inotropic support—rates comparable to previously reported hemato-oncology PICU cohorts (5,6). The overall mortality rate of 19% was lower than the pooled global estimate of 27.8% but higher than the 15% reported in high-income multicenter cohorts (10,14). Local data in Saudi Arabia remain limited; however, findings from regional HSCT populations show substantially higher mortality rates (41%), with mechanical ventilation and inotropic support strongly associated with death (11).

In this study, non-survivors were more likely to have comorbidities, require intensive organ support, and have therapeutic exposure prior to PICU admission. Both mechanical ventilation and prior therapeutic interventions independently predicted mortality, increasing the hazard of death three-fold. These findings align with multiple prior studies identifying mechanical ventilation, cumulative treatment burden, and the need for organ-support therapies as central predictors of mortality among critically ill oncology patients (7,8,12,13,15–17).

In contrast to earlier studies demonstrating higher mortality among patients with hematologic malignancies (14), our results did not show significant mortality differences based on tumor type. Nevertheless, infections—particularly sepsis—remained major contributors to clinical deterioration, reinforcing the need for robust infection-prevention strategies, early antimicrobial therapy, and rapid sepsis management.

Although PRISM III scores were higher among non-survivors, the score did not remain an independent predictor of mortality in multivariable analysis. This finding reflects ongoing debate about the predictive accuracy of general severity scoring tools in pediatric oncology populations, suggesting that oncology-specific risk stratification tools may be needed (11,12).

This study also addresses an important gap in regional literature, providing one of the first descriptions of PICU outcomes among pediatric oncology patients in Saudi Arabia. Early identification of high-risk patients, timely escalation of respiratory and hemodynamic support, and aggressive sepsis management are essential to improving outcomes in this vulnerable group.

Key limitations include the retrospective, single-center design, which may limit generalizability, as well as potential residual confounding and lack of long-term follow-up. Future multicenter, prospective studies are needed to refine prognostic indicators, validate severity scoring tools in pediatric oncology, and inform the development of standardized, evidence-based care pathways for critically ill pediatric cancer patients.

5. Conclusions

Pediatric oncology patients requiring PICU admission experience substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly those with prior therapeutic exposure or who require invasive organ support such as mechanical ventilation and inotropes. Sepsis and respiratory failure remain the primary drivers of critical illness. Early recognition of clinical deterioration, aggressive infection prevention and management, and timely initiation of supportive therapies are essential to improving outcomes. Incorporating validated severity scoring tools may support early risk stratification and guide clinical decision-making. Multicenter, prospective studies with long-term follow-up are needed to refine prognostic indicators and optimize care pathways for critically ill pediatric oncology patients.

Author Contributions

Wafaa Aljizani: Led the conception and design of the study, coordinated and contributed with data collection, interpreted the findings, and drafted the background of manuscript, reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, Supervised the overall project, provided expert guidance throughout data interpretation, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Fatmah Othman: Performed the initial data analysis, assisted with data acquisition and data verification, wrote the methodology and result part and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. Faisal Alrashed: Contributed with data collection, drafted the discussion part of manuscript. Faisal Althaqeel: Contributed with data collection, drafted the discussion part of manuscript. Obaid Alfuraydi: Contributed with data collection, drafted the discussion part of manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) (Approval No.: RC18.334R, date 25 October 2018). All patient data were de-identified to maintain confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy and institutional regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with appropriate ethical approvals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALL |

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| AML |

Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

ED

HLH

HR

IQR

KASCH

KM

NHL

PRISM

WHO |

Emergency Department

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis

Hazard Ratio

Interquartile Range

King Abdullah Specialized Children’s Hospital

Kaplan-Meier

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Pediatric Risk of Mortality

World Health Organization |

References

- Saudi Cancer Registry. Cancer Incidence Report Saudi Arabia. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- SEER Program Research Data, 1973–2017.

- Dalton, H.J.; Slonim, A.D.; Pollack, M.M. Multicenter outcome of pediatric oncology patients requiring intensive care. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2003, 20, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenman, M.B.; Vik, T.; Hui, S.L.; Breitfeld, P.P. Hospital resource utilization in childhood cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2005, 27, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaret, P.; Pettersen, G.; Hubert, P.; Teira, P.; Emeriaud, G. Critically ill pediatric hemato-oncology patients: epidemiology and PICU transfer strategy. Ann. Intensive Care 2012, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinter, M.S.; DuBois, S.G.; Spicer, A.; Matthay, K.; Sapru, A. Pediatric cancer type predicts critical care needs and mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2014, 40, 1536–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollack, M.M.; et al. The ideal time interval for severity-of-illness assessment. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 14, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wösten-van Asperen, R.M.; et al. PICU mortality of children with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019, 142, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlAbdullah, H.; et al. Post-HSCT outcomes in PICU: Saudi experience. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Ther. 2024, 17, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschke, A.; et al. Clinical pathways for high-risk pediatric oncology patients. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1033993. [Google Scholar]

- Hallahan, A.R.; et al. Improved outcomes of children with malignancy in PICU. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 28, 3718–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, J.H.; et al. Mortality risk factors in hematologic neoplasms admitted to ICU. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Abraham, R.; et al. Predictors of outcome in PICU patients with malignancy. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2002, 24, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburro, R.F.; et al. Outcomes for oncology and HSCT patients requiring ventilation. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 9, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabdulsalam, M.K.; et al. Clinical profiles and mortality risk factors in pediatric pulmonary hemorrhage. Ann. Saudi Med. 2025, 45, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).