Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Aims and Objectives

1.1.1. Importance of FRAS1 Gene in Fraser Syndrome

2. Materials and Methods

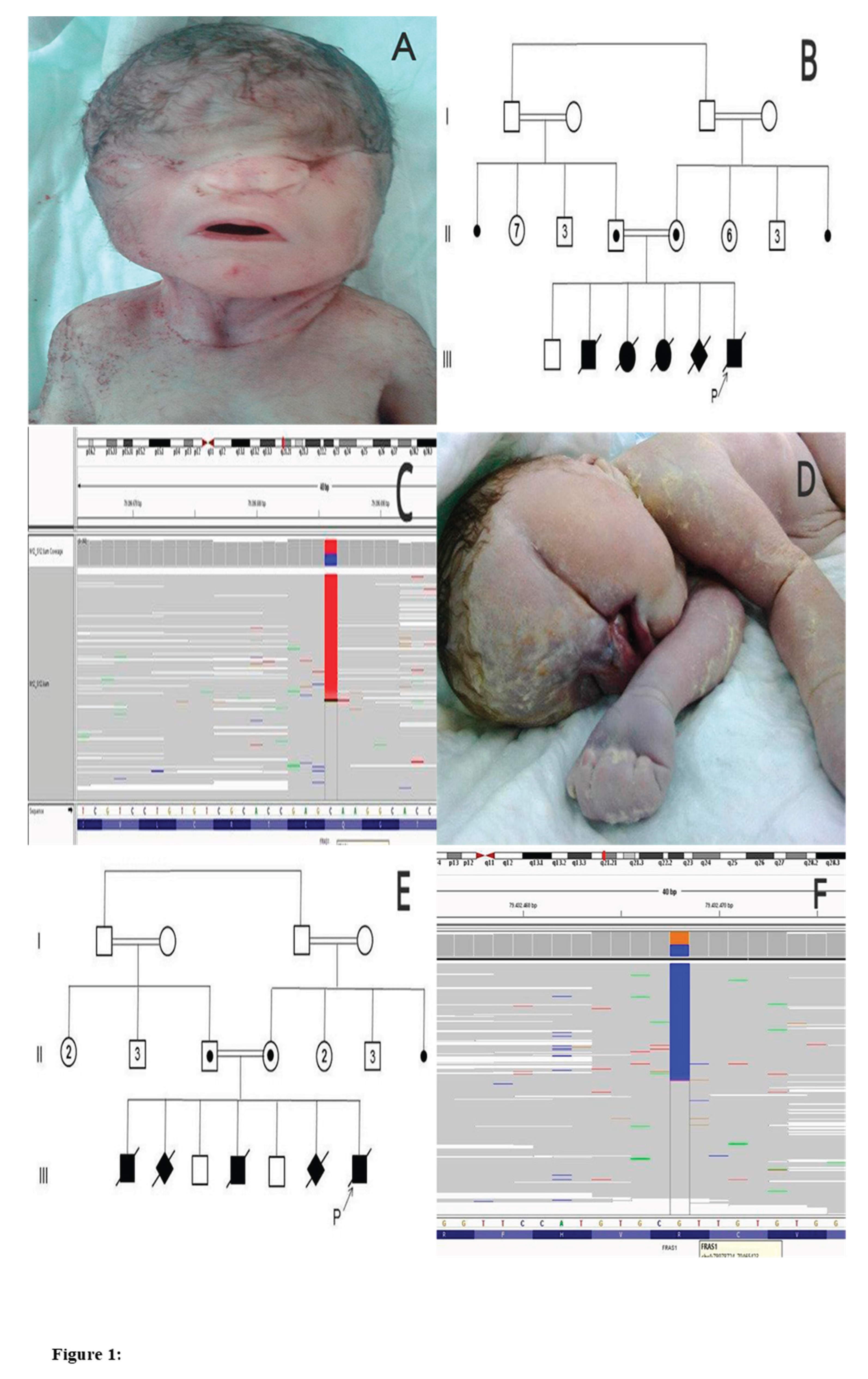

2.1. Case.01

2.1.1. History of Patient

2.1.2. Diagnosis

2.2. Case. 02

2.2.1. History of Patient

2.2.2. Diagnosis

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouaoud J, Olivetto M, Testelin S, Dakpé S, Bettoni J, Devauchelle B. Fraser syndrome: review of the literature illustrated by a historical adult case. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2020, 49(10), 1245-1253.

- Das D, Modaboyina S, Raj S, Agrawal S, Bajaj MS. Clinical features and orbital anomalies in Fraser syndrome and a review of management options. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2022, 70(7), 2559-2563.

- Neri ID, Vela APF, Mendoza RLA, Roa RG, Vizcaino GCR. Prenatal hydrometrocolpos as an unusual finding in Fraser syndrome. Case report. Case Reports in Perinatal Medicine. 2023, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Laminou L, Habou O, Amadou M, Hadjia A K Y, Abdou A. Fraser syndrome: About A Case and Review of the Literature. Journal of Surgery and Research. 2022, 5(4), 585-587.

- Sajoura C, Ech-Chebab M, Ayyad A, Messaoudi S, Amrani R. Fraser Syndrome: A Case Report. Open Journal of Pediatrics. 2024, 14(3), 476-481.

- Felton A. What Is Fraser Syndrome? 2022, WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/ children/what-is-fraser-syndrome.

- Esho T, Kobbe B, Tufa SF, Keene DR, Paulsson M, Wagener R. The Fraser Complex Proteins (Frem1, Frem2, and Fras1) Can Form Anchoring Cords in the Absence of AMACO at the Dermal–Epidermal Junction of Mouse Skin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023, 24(7), 6782.

- Ikeda S, Akamatsu C, Ijuin A, Nagashima A, Sasaki M, Mochizuki A, Nagase H, Enomoto Y, Kuroda Y, Kurosawa K. Prenatal diagnosis of Fraser syndrome caused by novel variants of FREM2. Human genome variation. 2020, 7(1), 32.

- Arcot Sadagopan K. Genetics in Oculoplastics. Smith and Nesi’s Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2021, 1115-1143.

- Wang G, Wang Z, Lu H, Zhao Z, Guo L, Kong F, Wang A, Zhao S. Comprehensive analysis of FRAS1/FREM family as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in renal clear cell carcinoma. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2022, 13, 972934.

- Ou T-Y, Tsai M-C, Kuo P-L, Lee N-C, Chou Y-Y. Whole exome sequencing identifies a novel FRAS1 mutation and aids in vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic diagnosis in Fraser syndrome. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022, 61(3), 521-524.

- Tsuji Y, Yamamura T, Horinouchi T, Sakakibara N, Ishiko S, Aoto Y, Rossanti R, Okada E, Tanaka E, Tsugawa K. Systematic review of genotype- phenotype correlations in Frasier syndrome. Kidney International Reports. 2021, 6(10), 2585-2593.

- Chańska W. The principle of nondirectiveness in genetic counseling. Different meanings and various postulates of normative nature. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy. 2022, 25(3), 383-393.

- Landau-Prat D, Kim DH, Bautista S, Strong A, Revere KE, Katowitz WR, Katowitz JA. Cryptophthalmos: associated syndromes and genetic disorders. Ophthalmic Genetics. 2023, 44(6), 547-552.

- Murali S, Almahmoudi FH, Traboulsi EI. SECTION IV Systematic Pediatric Ophthalmology. Taylor and Hoyt’s Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2022, 179.

- Skalniak A, Trofimiuk-Müldner M, Surmiak M, Totoń-Żurańska J, Jabrocka-Hybel A, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A. Whole-exome screening and analysis of signaling pathways in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 patients with different outcomes: insights into cellular mechanisms and possible functional implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024, 25(2), 1065.

- Kumaran K, Abirami S, Ajeesh A, Hemarangan J, Vasanth Kanth T, Shriya P, Aruljothi K. Prenatal Screening and Counseling for Rare Genetic Disorders. In Rare Genetic Disorders: Advancements in Diagnosis and Treatment. 2024, (pp.61-76). Springer.

- Lamandé S R, Bateman JF. Genetic disorders of the extracellular matrix. The anatomical record. 2020, 303(6), 1527-1542.

- Sahin E, İnciser Paşalak Ş, Seven M. Consanguineous marriage and its effect on reproductive behavior and uptake of prenatal screening. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2020, 29(5), 849-856.

- Camats N, Flück CE, Audí L. Oligogenic origin of differences of sex development in humans. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020, 21(5), 1809.

- Koprulu M, Kumare A, Bibi A, Malik S, Tolun A. The first adolescent case of Fraser syndrome 3, with a novel nonsense variant in GRIP1. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2021,185(6), 1858-1863.

- Shrestha S, Thani KP, Keshari M, Shrestha A. Fraser Syndrome: A Rare Case Report. Journal of Karnali Academy of Health Sciences. 2022, 5(3).

- Fortin O, Mulkey SB, Fraser JL. Advancing fetal diagnosis and prognostication using comprehensive prenatal phenotyping and genetic testing. Pediatric Research. 2024, 1-11.

- Ryan CE, Schust DJ. Recurrent pregnancy loss. Clinical Maternal-Fetal Medicine, 2021, 4.1-4.13.

- Elmugadam FM, Ahmed H, Karamelghani M, Ali A, Ali I, Ahmed A, Salman M, Mohamed W, Ahmed EA, Ahmed KAHM. Awareness of consanguineous marriage burden and willingness towards premarital genetic testing in Sudan: a national cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2024, 86(7), 3959-3971.

- Provenzano A, Palazzo V, Reho P, Pagliazzi A, Marozza A, Farina A, Zuffardi O, Giglio S. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis in a family at risk for Fraser syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2020, 40(7): 905-908.

- Zhu L, Shen S, Pan C, Lan X, Li J. Bovine FRAS1: mRNA Expression Profile, Genetic Variations, and Significant Correlations with Ovarian Morphological Traits, Mature Mature Follicle, and Corpus Luteum. Animals (Basel). 2024, 14(4):597. [CrossRef]

- Maksiutenko EM, Barbitoff YA, Nasykhova YA, Pachuliia OV, Lazareva TE, Bespalova ON, Glotov AS. The Landscape of Point Mutations in Human Protein Coding Genes Leading to Pregnancy Loss. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023, 24(24), 17572.

- Al-Hamed MH, Sayer JA, Alsahan N, Tulbah M, Kurdi W, Ambusaidi Q, Ali W, Imtiaz F. Novel loss of function variants in FRAS1 AND FREM2 underlie renal agenesis in consanguineous families. Journal of nephrology. 2021, 34, 893-900.

- Kunz F, Kayserili H, Midro A, de Silva D, Basnayake S, Güven Y, Borys J, Schanze D, Stellzig-Eisenhauer A, Bloch-Zupan A. Characteristic dental pattern with hypodontia and short roots in Fraser syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2020, 182(7), 1681-1689.

- Borgio JF. Heterogeneity in biomarkers, mitogenome and genetic disorders of the Arab population with special emphasis on large-scale whole-exome sequencing. Archives of Medical Science: AMS. 2023, 19(3), 765.

- Garrison Jr LP, Lo AW, Finkel RS, Deverka PA. A review of economic issues for gene-targeted therapies: Value, affordability, and access. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2023, 193(1):64-76.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).