Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Mental Health of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

1.2. Mindfulness and Parental Mental Health

1.2. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

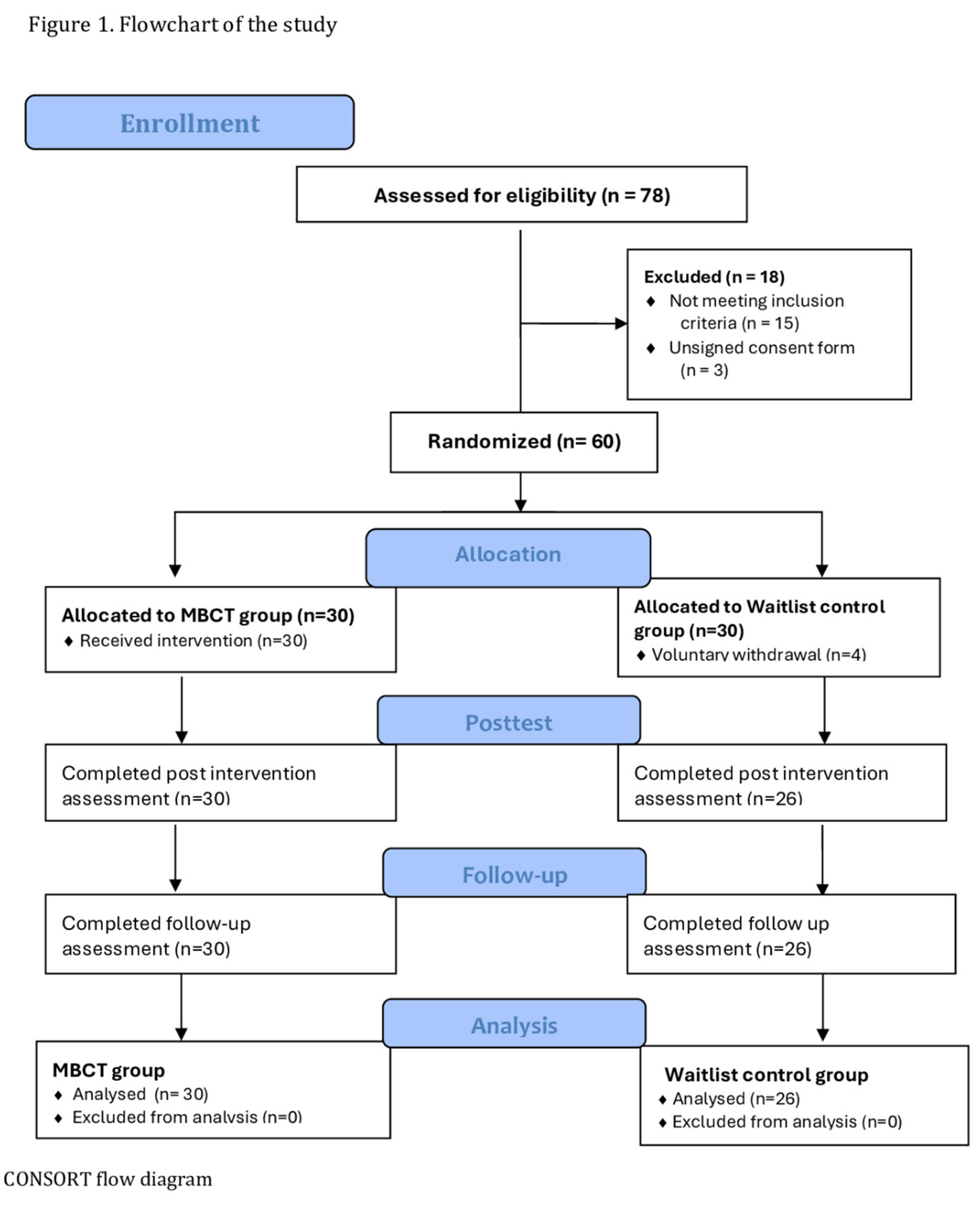

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants and Sample Size

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Psychosocial and Demographic Questionnaire

2.4.2. Parental Mental Health and Wellbeing

2.4.3. Intervention Acceptability

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Intervention

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristic

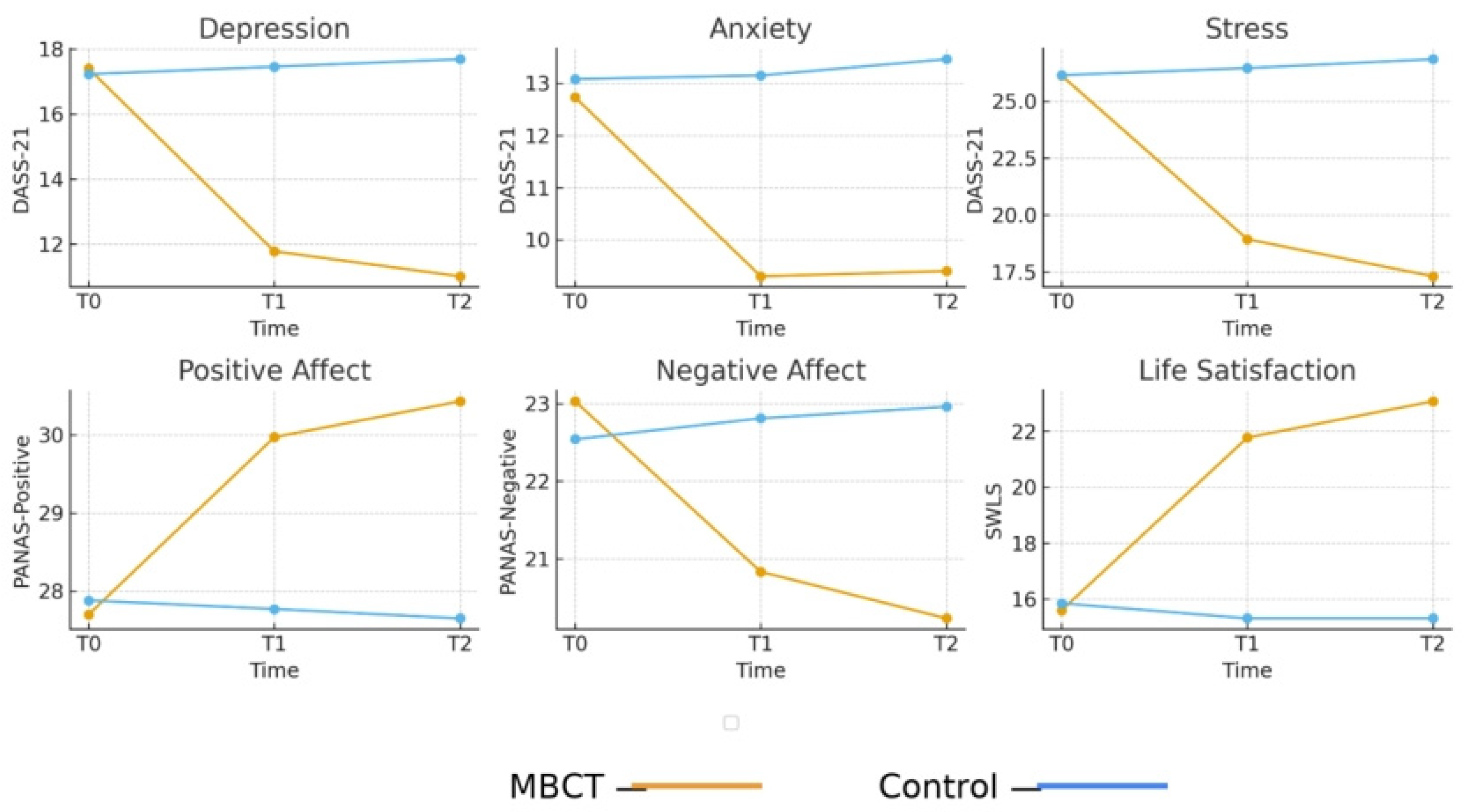

3.2. Effect of the MBCT Program on Parental Mental Health Outcomes

3.2.1. Depression

3.2.2. Anxiety

3.2.3. Stress

3.2.4. Life Satisfaction

3.2.5. Positive and Negative Affect

3.3. Intervention Acceptability

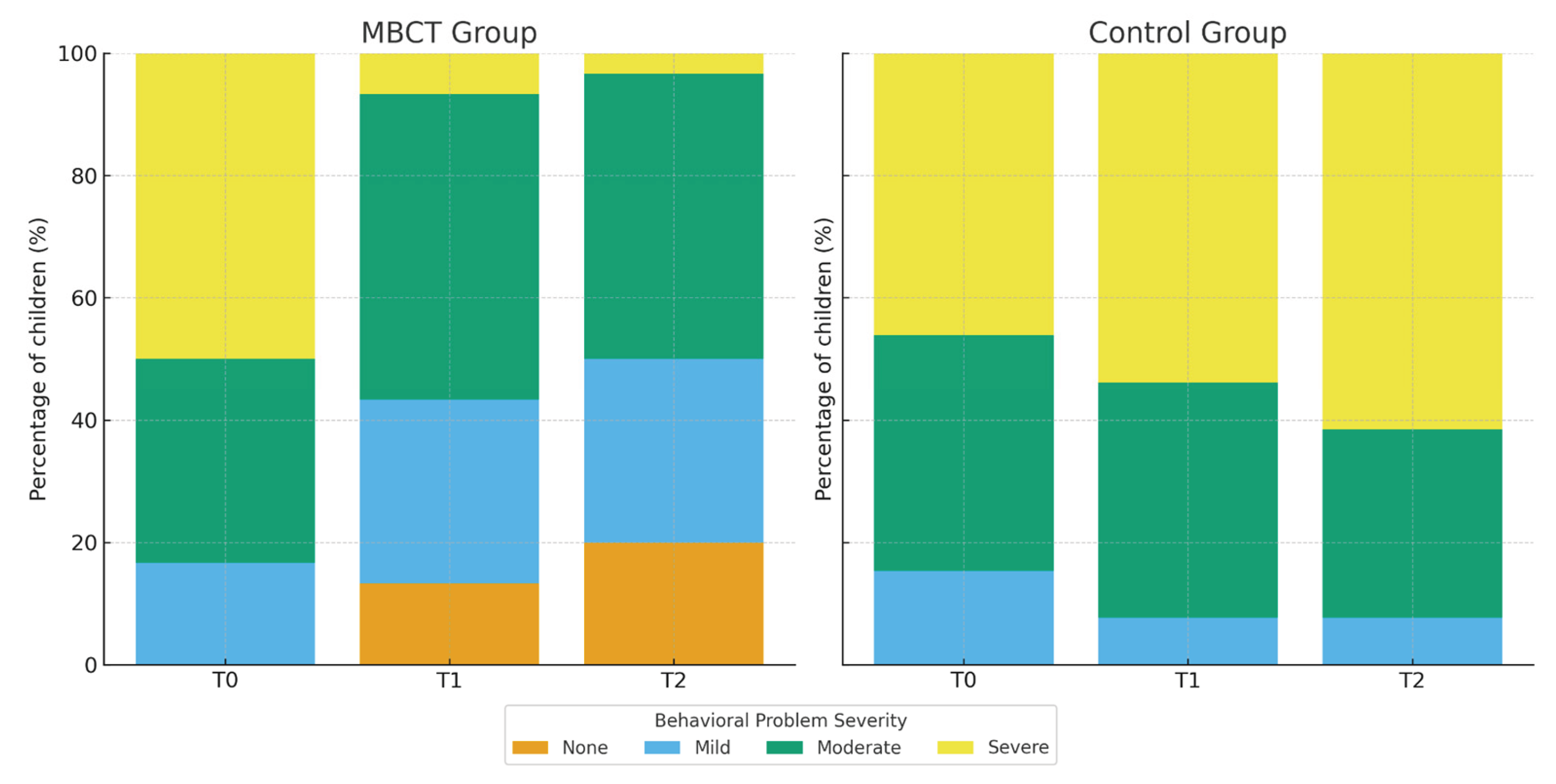

3.4. Child Behavioral Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Preliminary Findings

4.2. Effectiveness of MBCT on Parental Mental Health

4.3. Acceptance of the Intervention

4.4. Indirect Effects on Children’s Behavior

4.5. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marsack-Topolewski, C.N.; Samuel, P.S.; Tarraf, W. Empirical evaluation of the association between daily living skills of adults with autism and parental caregiver burden. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecavalier, L.; Leone, S.; Wiltz, J. The impact of behavior problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Amate, J.J.; Luque de la Rosa, A. The Effect of Autism Spectrum Disorder on Family Mental Health: Challenges, Emotional Impact, and Coping Strategies. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, A.; Olson, E.; Sullivan, K.; Greenson, J.; Winter, J.; Dawson, G.; Munson, J. Parenting-related stress and psychological distress in mothers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Dev. 2013, 35, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, D. Mothers’ experiences and challenges raising a child with autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative study. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bögels, S.; Restifo, K. Mindful Parenting: A Guide for Mental Health Practitioners; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- van der Lubbe, A.; Swaab, H.; Vermeiren, R.; et al. Chronic Parenting Stress in Parents of Children with Autism: Associations with Chronic Stress in Their Child and Parental Mental and Physical Health. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekas, N.V.; Lickenbrock, D.M.; Whitman, T.L. Optimism, social support, and well-being in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetti. Full reference details not provided in the current draft; please complete according to MDPI style. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, N.O.; Carter, A.S. Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.S.; Martínez-Pedraza, F. de L.; Gray, S.A. Stability and individual change in depressive symptoms among mothers raising young children with ASD: Maternal and child correlates. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, M.C.; Graczyk, P.A.; O’Hare, E.; Neuman, G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 20, 561–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladstone, T.R.G.; Beardslee, W.R.; Diehl, A. The impact of parental depression on children. In Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families, 3rd ed.; Reupert, A., Maybery, D., Nicholson, J., Göpfert, M., Seeman, M.V., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman. Full reference details not provided in the current draft; please complete. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B.; Gong, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. The impact of maternal parenting stress on early childhood development: the mediating role of maternal depression and the moderating effect of family resilience. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chad-Friedman, S.; Zhang, I.; Donohue, K.; Chad-Friedman, E.; Rich, B.A. Reciprocal associations between parental depression and child cognition: Pathways to children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Dev. Psychopathol. 2025, 37, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbeduto. Full reference details not provided in the current draft; please complete. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska, A.; Pisula, E. Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of preschool children with autism and Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.A.; Watson, S.L. The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesilkaya, M.; Magallón-Neri, E. Parental Stress Related to Caring for a Child With Autism Spectrum Disorder and the Benefit of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Parental Stress: A Systematic Review. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra-de Neijs, L.; Swaab, H.; van Berckelaer-Onnes, I.A.; et al. Resilience Within Families of Young Children with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Q.; Chen, S.-D.; Li, X.-K.; Ren, J. Mental health of parents of special needs children in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, D. Impact of child and family factors on caregivers’ mental health and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. Children 2023, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, B.; Wetherell, M.A. Child behaviour problems mediate the association between coping and perceived stress in caregivers of children with autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2015, 20, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soke, G.N.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Rosenberg, C.R.; Vasa, R.A.; Lee, L.C.; DiGuiseppi, C. Brief Report: Self-injurious Behaviors in Preschool Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Compared to Other Developmental Delays and Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48(7), 2558–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Ekas, N.V.; Hock, R. Associations between child behavior problems, family management, and depressive symptoms for mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2016, 26, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postorino, V.; Sanges, V.; Giovagnoli, G.; Fatta, L.M.; De Peppo, L.; Armando, M.; Vicari, S.; Mazzone, L. Clinical differences in children with autism spectrum disorder with and without food selectivity. Appetite 2015, 92, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, J.S.; Van Hecke, A.V. Parent and family impact of autism spectrum disorders: A review and proposed model for intervention evaluation. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 15(3), 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, S.L.; Barker, E.T.; Seltzer, M.M.; Floyd, F.; Greenberg, J.; Orsmond, G.; Bolt, D. The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.K.S.; Leung, D.C.K. The Impact of Child Autistic Symptoms on Parental Marital Relationship: Parenting and Coparenting Processes as Mediating Mechanisms. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, M.; Stoddart, K.P.; Gibson, M.; Morris, R.; Barrett, D.; Muskat, B.; Nicholas, D.; Rampton, G.; Zwaigenbaum, L. Couple relationships among parents of children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Findings from a scoping review of the literature. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2015, 17, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitlauf, A.S.; McPheeters, M.L.; Peters, B.; Sathe, N.; Travis, R.; Aiello, R.; Williamson, E.; Veenstra-VanderWeele, J.; Krishnaswami, S.; Jerome, R.; Warren, Z. Report No. 14-EHC036-EF; Therapies for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Behavioral Interventions Update. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [PubMed]

- Kersh, J.; Hedvat, T.T.; Hauser-Cram, P.; Warfield, M.E. The contribution of marital quality to the well-being of parents of children with developmental disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50(12), 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brobst, J.B.; Clopton, J.R.; Hendrick, S.S. Parenting children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: The couple’s relationship. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2009, 24(1), 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, A.J. The Transactional Model of Development: How Children and Contexts Shape Each Other; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.K. Full reference details not provided in the current draft; please complete. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neece, C.L.; Green, S.A.; Baker, B.L. Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 117, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neece, C.L. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for parents of young children with developmental delays: Implications for parental mental health and child behavior problems. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2014, 27, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neece, C.L.; Baker, B. Predicting maternal parenting stress in middle childhood: The roles of child intellectual status, behavior problems, and social skills. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2008, 52, 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.K.; Messinger, D.S.; Lyons, K.K.; Grantz, C.J. A pilot study of maternal sensitivity in the context of emergent autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, T. Personality Characteristics and Neurocognitive Functions in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2017, 29, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S.; Narayan, S.; Moyes, B. Personality characteristics of parents of autistic children: A controlled study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1988, 29, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie, C.G.; Ingram, K.M. Daily stress, coping, and wellbeing in parents of children with autism: A multilevel modeling approach. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.R.; Karlof, K.L. Anger, stress proliferation, and depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: A longitudinal replication. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Tooley, E.M.; Christopher, P.J.; Kay, V.S. Resilience as the ability to bounce back from stress: A neglected personal resource? J. Posit. Psychol. 2010, 5, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, K.W.; McCammon, S.L.; Wuensch, K.L.; Golden, J.A. Enrichment, stress, and growth from parenting an individual with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 34, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddock, L.R. Third-wave cognitive behavioral theories with mindfulness-based interventions. In Counseling and Psychotherapy: Theories and Interventions, 7th ed.; Capuzzi, D., Stauffer, M.D., Eds.; American Counseling Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2022; pp. 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Hofmann, S.G. “Third-wave” cognitive and behavioral therapies and the emergence of a process-based approach to intervention in psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, K. Parents of children with disabilities, mindfulness and acceptance: A review and a call for research. Mindfulness 2014, 5, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt, G.A.; Kristeller, J.L. Mindfulness and meditation. In Integrating Spirituality into Treatment: Resources for Practitioners; Miller, W.R., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.J.; Kabat-Zinn, J.; Schumacher, J.; Rosenkranz, M.; Muller, D.; Santorelli, S.F.; Urbanowski, F.; Harrington, A.; Bonus, K.; Sheridan, J.F. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom. Med. 2003, 65, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.P.; Stanley, E.A.; Kiyonaga, A.; Wong, L.; Gelfand, L. Examining the protective effects of mindfulness training on working memory capacity and affective experience. Emotion 2010, 10, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögels, S.; Hoogsteder, A.; van Tadjen, L. Mindful parenting to reduce parenting stress: Results from a pilot study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2008, 17, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.N.; Lancioni, G.E.; Winton, A.S.; Singh, J. Mindfulness training for parents and their children with ADHD increases the children’s compliance. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2006, 15, 302–315. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Z.V.; Williams, J.M.G.; Teasdale, J.D. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Z.V.; Williams, J.M.G.; Teasdale, J.D. The Mindful Way Workbook: An 8-Week Program to Free Yourself from Depression and Emotional Distress; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bailie, C.; Smith, S.; Garbutt, J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A qualitative evaluation. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2011, 20, 347–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J.; Kabat-Zinn, M. Everyday Blessings: The Inner Work of Mindful Parenting; (Original work published 1997); Hachette Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bögels, S.; Hellemans, J.; van Deursen, S.; Römer, M.; van der Meulen, R. Mindful parenting in mental health care: Effects on parental and child psychopathology, parental stress, parenting, co-parenting, and marital functioning. Mindfulness 2010, 1, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bögels. Full reference details not provided in the current draft; please complete. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- van der Oord, S.; Bögels, S.M.; Peijnenburg, D. The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 21, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, J.; Fernández, S.; Slusarchuk, C. Mindful parenting and maternal well-being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Mindfulness 2013, 4, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, C.M.; White, S.W. Parenting stress among parents of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: The roles of child characteristics and parental emotional functioning. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 1862–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanington, L.; Ramchandani, P.; Stein, A. Parental depression and child temperament: Assessing child-to-parent effects in a longitudinal population study. Infant Behav. Dev. 2010, 33, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rayan, A.; Ahmad, M. Mindfulness and parenting distress among parents of children with disabilities: The mediating role of parental self-efficacy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 69, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen, C.L.; Sanders, M.R. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a brief parenting program with children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrakos, G.N.; Arvaniti, C.; Smyrnioti, M.; Kostopanagiotou, G. Translation and validation study of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale in the Greek general population and in a psychiatric patient’s sample. Eur. Psychiatry 2011, 26(S2), 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrakos. Greek adaptation of SWLS—full bibliographic details not provided; please complete. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, R.; Akiva, T.; Arel, S.; Roeser, R.W. Mindfulness training effects for parents and educators of children with special needs. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1476–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalou, V.; Sigkollitou, E. Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS). In Psychometric Instruments in Greece, 2nd ed.; Stalikas, A., Triliva, S., Roussi, P., Eds.; Pedio: Athens, Greece, 2012; p. 526. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, L.G.; Coatsworth, J.D.; Greenberg, M.T. A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 12, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 10th ed.; Pearson/Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Andover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cengiz, Kılıç. RCT in mindfulness literature—full reference details not provided; please complete. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alibekova, R.; Chan, C.K.; Crape, B.; Kadyrzhanuly, K.; Gusmanov, A.; An, S.; Bulekbayeva, S.; Akhmetzhanova, Z.; Ainabekova, A.; Yerubayev, Z.; et al. Stress, anxiety and depression in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders in Kazakhstan: Prevalence and associated factors. Global Ment. Health 2022, 9, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzano, A.; Wolfe, C.; Zylowska, L.; Wang, S.; Schuster, E.; Barrett, C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for parents and caregivers of individuals with developmental disabilities: A community-based approach. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunsky, Y.; Albaum, C.; Baskin, A.; Hastings, R.P.; Hutton, S.; Steel, L.; Wang, W.; Weiss, J. Group Virtual Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Parents of Autistic Adolescents and Adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 3959–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, M.; Sanaat, Z.; Jafarnejad, F.; Dadkhah, F. Increasing the tolerance of mothers with children with autism: The effectiveness of cognitive therapy based on mindfulness—experimental research. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 86, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.; Reiner, K.; Meiran, N. “Mind the trap”: Mindfulness practice reduces cognitive rigidity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, J.D.; Segal, Z.V.; Williams, J.M.G.; Ridgeway, V.A.; Soulsby, J.M.; Lau, M.A. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.H.; Teasdale, J.D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: Replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerhoff, A.; Ehring, T.; Takano, K. Effects of induced mindfulness at night on repetitive negative thinking: Ecological momentary assessment study. JMIR Ment. Health 2023, 10, e44365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hick, S.F.; Chan, L. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: Effectiveness and Limitations. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2010, 8, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachia, R.L.; Anderson, A.; Moore, D.W. Mindfulness, stress and well-being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluth, K.; Wahler, R.G. Does effort matter in mindful parenting? Mindfulness 2011, 2, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn. Mindfulness-based program for parents—full reference details not provided; please complete. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf, W.; Szabó, M.; Abbott, M.J. Mindful parenting: A meta-analytic review of effects on parents, children, and parenting. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 75, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.N.; Lancioni, G.E.; Karazsia, B.T.; Myers, R.E.; Hwang, Y.S.; Anālayo, B. Effects of mindfulness-based positive behavior support training are equally beneficial for mothers and their children with autism spectrum disorder or with intellectual disabilities. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitlauf, A.S.; Vehorn, A.C.; Taylor, J.L.; Hampton, L.H. A pilot study of a remote parent-mediated early intervention for children with autism. Autism 2020, 24, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R.Y.M.; Chan, S.K.C.; Chui, H.; et al. Enhancing parental well-being: Initial efficacy of a 21-day online self-help mindfulness-based intervention for parents. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 2812–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Farb, N.A.; Goldin, P.R.; Fredrickson, B.L. The mindfulness-to-meaning theory: Extensions, applications, and challenges at the attention–appraisal–emotion interface. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunimatsu, M.M.; Marsee, M.A. Examining the presence of anxiety in aggressive individuals: The illuminating role of fight-or-flight mechanisms. Child Youth Care Forum 2012, 41, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnett, P.H.; Whittingham, K.; Puhakka, E.; Hodges, J.; Spry, C.; Dob, R. The short-term impact of a brief group-based mindfulness therapy program on depression and life satisfaction. Mindfulness 2010, 1, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Mindfulness-based interventions and life satisfaction among parents of children with developmental disorders: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-García, P.A.A.; Soto-Vásquez, M.R.; Infantes Gomez, F.M.; Guzman Rodriguez, N.M.; Castro-Paniagua, W.G. Effect of a mindfulness program on stress, anxiety, depression, sleep quality, social support, and life satisfaction: A quasi-experimental study in college students. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1508934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, L.; Li, Q. How mindfulness affects life satisfaction: Based on the mindfulness-to-meaning theory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 887940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N.; Rey, L. Ability emotional intelligence and life satisfaction: Positive and negative affect as mediators. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 102, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, B.K.; Carmody, J.; Vangel, M.; Congleton, C.; Yerramsetti, S.M.; Gard, T.; Lazar, S.W. Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2011, 191, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Hong, T.; Zhou, H.; Garland, E.L.; Hu, Y. The acute effect of mindfulness-based regulation on neural indices of cue-induced craving in smokers. Addict. Behav. 2024, 159, 108134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, H.K.; Duncan, L.G.; Lightcap, A.; Khan, F. Mindful parenting predicts mothers’ and infants’ hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal activity during a dyadic stressor. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen-Cico, D.; Possemato, K.; Pigeon, W. Reductions in cortisol associated with primary care brief mindfulness program for veterans with PTSD. Med. Care 2014, 52 Suppl. 5, S25–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín. Mindfulness and cortisol—full reference details not provided; please complete. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Robledillo, N.; Moya-Albiol, L. Emotional intelligence modulates cortisol awakening response and self-reported health in caregivers of people with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014, 8, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.N.; Raj, S.P. Self-compassion intervention for parents of children with developmental disabilities: A feasibility study. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2023, 7, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraioli, S.; Harris, S.L. The impact of mindfulness-based interventions on the well-being of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2013, 7, 1318–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, N.; Neece, C.L. Parenting stress and emotion dysregulation among children with developmental delays: The role of parenting behaviors. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 4071–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, K.S.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Mokrysz, C.; Nosek, B.A.; Flint, J.; Robinson, E.S.; Munafo, M.R. Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Lei, Z.; Chen, M.; Deng, H.; Liang, R.; Yu, M.; Huang, H. Effects of self-help mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on mindfulness, symptom change, and suicidal ideation in patients with depression: A randomized controlled study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1287891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los Reyes, A.; Kazdin, A.E. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 483–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlthau, K.; Payakachat, N.; Delahaye, J.; Hurson, J.; Pyne, J.M.; Kovacs, E.; Tilford, J.M. Quality of life for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014, 8, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J.; Kabat-Zinn, M. Mindful Parenting: Guide to Raising Compassionate Kids; Piatkus: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Instruments | Items/Subscales | Scoring and Interpretation |

Cronbach’s α (Present Study) |

| DASS-21 [67] (Depression, Anxiety, Stress) |

21 3 subscales (7 items each) |

4-point Likert scale (0–3); subscale scores multiplied by 2; higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. |

Depression=0.75, Anxiety=0.64, Stress=0.82 |

| PANAS [71] (Positive–Negative Affect) |

20; 2 subscales (10 items each) |

5-point Likert scale (1–5); higher PA = greater positive affect, higher NA = greater distress. |

Pos.=0.63 Neg.=0.77 |

| SWLS [73] (Satisfaction with Life) |

5 | 7-point Likert scale (1–7); higher total scores reflect greater life satisfaction. |

Life satisfaction = 0.82 |

| Week / Session | Core Theme | Primary Mindfulness Practices | MBCT / Mindful Parenting Components |

| Week 1 | Awareness and Autopilot | Mindful eating (raisins task); Introduction to body scan | Recognizing automatic parenting reactions; introducing the program structure and group guidelines |

| Week 2 | Facing Obstacles / A Different Way of Knowing | Body scan; Short mindful breathing | Distinguishing “doing” vs. “being” mode; observing difficult parenting thoughts/emotions as mental events |

| Week 3 | Focusing the Scattered Mind | Extended mindful breathing; Mindful movement; 3-minute breathing space | Applying attentional focus before/after challenging parent–child interactions |

| Week 4 | Responding to Experience / Recognizing Aversion | Sitting meditation (breath, body, sounds, thoughts) | Noticing pleasant and unpleasant events in parenting; cultivating nonjudgmental awareness toward the child |

| Week 5 | Allowing and Letting Be | Acceptance-focused meditation (observing difficult emotions) | Allowing parental emotions (guilt, frustration, sadness) to arise without avoidance or suppression |

| Week 6 | Thoughts Are Not Facts | Sitting meditation emphasizing thought awareness | Decentering from self-critical thoughts (e.g., “I am not a good parent”); reframing automatic interpretations |

| Week 7 | Self-Care and Relapse Prevention | Extended sitting meditation | Identifying personal stress triggers; developing a self-care and mindful parenting maintenance plan |

| Week 8 | Maintaining and Extending New Learning | Review of core practices; Choice of preferred meditation | Creating individualized mindful parenting plans; integrating mindfulness into daily routines |

| Variables |

Total participants (n=56) |

MBCT group (n=30) |

Waitlist Control group (n=26) |

χ2/T | P |

| Parental characteristics | |||||

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 19 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Female | 37 | 21 | 16 | .445 | .505 |

| Age in years (M/SD) | 40.67 | 40.52 | 40.85 | -.194 | .846 |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||

| Married | 42 | 22 | 20 (76.9%) | ||

| Divorced | 9 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Single parent | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | .421 |

| Education level, n (%) | |||||

| Secondary | 10 | 3 | 7 | ||

| Technical/Technological | 24 | 15 | 9 | ||

| University | 22 | 12 | 10 | 3,011 | .222 |

| Employment status, n (%) |

|||||

| Public employee | 16 | 7 | 9 | ||

| Private employee | 27 | 15 | 12 | ||

| Self-employed | 13 | 8 | 5 | .995 | .608 |

| Child characteristics | |||||

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Boy | 45 | 24 | 21 | ||

| Girl | 11 | 6 | 5 | .005 | .942 |

| Age in years (M/SD) | 10.54 | 10.51 | 10.59 | .072 | .942 |

| Duration since diagnosis (M/SD) |

5.84 | 5.78 | 5.9 | -.129 | .897 |

| Severity of child’s behavior problem, n (%) |

|||||

| Mild | 9(16.1%) | 5(16.7%) | 4(15.4%) | ||

| Moderate | 20(35.7%) | 10(33.3%) | 10(38.5%) | ||

| Severe | 27(48.2%) | 15(50%) | 12(46.2%) | .160 | .923 |

| Indicators | Total Participants (n=56) | MBCT Group (n=30) |

Control Group (n=26) |

t | p |

| M/SD | M/SD | M/SD | |||

| DASS-21 | |||||

| Depression | 17.32±4.29 | 17.4±4.85 | 17.23±3.63 | 3.573 | .168 |

| Anxiety | 13±2.7 | 12.93±3.27 | 13.08±1.90 | 3.098 | .377 |

| Stress | 26.14±4.73 | 26.13±5.01 | 26.15±4.49 | .219 | .896 |

| PANAS | |||||

| Positive Affect | 27.79±2.10 | 27.70±2.45 | 27.88±1.65 | -.334 | .740 |

| Negative Affect | 22.80±2.70 | 23.03±3.35 | 22.54±1.70 | .711 | .481 |

| SWLS | |||||

| Life satisfaction | 15.71±2.81 | 15.6±3.16 | 15.85±2.41 | 1.811 | .770 |

| Indicator | Group |

Μ. ± S.D. (T0) |

Μ. ± S.D. (T1) |

Μ. ± S.D. (T2) |

T0 vs T1 | T0 vs T2 | T1 vs T2 |

Group x Time Interaction (F, p, ) |

| Depression | MBCT | 17.40 ± 4.85 | 11.77 ± 2.67 | 11.00 ± 2.39 | t(29)=10.37,p=<.001, d=1.89 | t(29)=8.52, p=<.001, d=1.56 |

t(29)=2.37, p=0.02, d=0.43 |

F=64.126, p<.001, η²p=0.543 |

| Control | 17.23 ± 3.63 | 17.46 ± 3.28 | 17.69 ± 3.47 | t(25)=−1.14,p=0.265, d=−0.22 | t(25)=−1.54,p=0.136, d=−0.30 |

t(25)=−0.90,p=0.376, d=−0.18 |

||

| Anxiety | MBCT | 12.73 ± 3.50 | 9.40 ± 2.24 | 9.30 ± 2.09 | t(29)=7.53, p=<.001, d=1.37 |

t(29)=6.72, p=<.001, d=1.23 |

t(29)=0.4. p=0.687, d=0.07 |

F=29.298, p< .001, η²p=0.352 |

| Control | 12.92 ± 2.05 | 13.15 ± 2.05 | 13.46 ± 2.16 | t(25) =-1.14, p = 0.265 d=-0.22 |

t(25)=−1.54,p=0.136, d=−0.30 |

t(25)=−0.90, p=0.376, d=−0.18 |

||

| Stress | MBCT | 26.13 ± 5.01 | 18.93 ± 4.48 | 17.30 ± 4.09 | t(29)=16.96,p=<.001, d=3.10 | t(29)=17.56,p=<.001, d=3.21 |

t(29)=4.18, p=<.001, d=0.76 |

F=188.515, p< .001, η²p=0.777 |

| Control | 26.15 ± 4.09 | 26.46 ± 4.09 | 26.85 ± 3.76 | t(25)=-0.39, p=.80, d=-0.047 |

t(25)=−1.17,p=0.025, d=−0.23 | t(25)=−0.65, p=0.50, d=−0.13 |

||

|

Positive Affect |

MBCT | 27.70 ± 2.45 | 29.97 ± 2.34 | 30.43 ± 2.39 | t(29)=−6.38,p=<.001, d=−1.16 |

t(29)=−6.46,p=<.00, d=−1.18 |

t(29)=−2.45,p=0.020, d=−0.45 |

F= 32.066, p < .001, η²p = 0.373 |

| Control | 26.69 ± 3.96 | 27.88 ± 1.66 | 27.65 ± 1.65 | t(25)=−1.28,p=0.211, d=−0.25 | t(25)=−1.01,p=0.323, d=−0.20 |

t(25)=1.19, p=0.247, d=0.23 |

||

| Negative Affect | MBCT | 23.03 ± 3.35 | 20.83 ± 1.72 | 20.23 ± 1.92 | t(29)=4.41, p=<.001, d=0.80 |

t(29)=5.34, p=<.001, d=0.98 |

t(29)=3.67, p=0.001, d=0.67 |

F= 25.267, p < .001, η²p = 0.319 |

| Control | 22.54 ± 1.70 | 22.81 ± 1.90 | 22.96 ± 1.97 | t(25)=0.97, p=0.341, d=-0.19 |

t(25)=−1.53,p=0.139, d=−0.30 | t(25)=−1.69,p=0.103, d=−0.33 |

||

| Life Satisfaction | MBCT | 15.60 ± 3.16 | 21.77 ± 2.97 | 23.07 ± 2.49 | t(29)=−12.5,p=<.001, d=−2.29 | t(29)=−14.8,p=<.001, d=−2.71 |

t(29)=−4.71,p=<.001, d=−0.86 |

F=132.156, p<.001, η²p=0.710 |

| Control | 15.31 ± 1.69 | 15.12 ± 1.53 | 15.04 ± 1.93 | t(25)=0.48, p=0.638, d=0.09 |

t(25)=1.32, p=0.199, d=0.26 |

t(25)=0.20, p=0.844, d=0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).