1. Introduction

Quantum mechanics assigns transition amplitudes the form

, making the

phase of the action the operational quantity in every experimentally verified interference phenomenon. Yet neither the de Broglie matter-wave hypothesis [

22] nor Feynman’s path-integral formulation [

28] explains

why physical observables depend only on the modular phase of

S, rather than on its absolute value. In standard formulations this modular dependence is simply postulated.

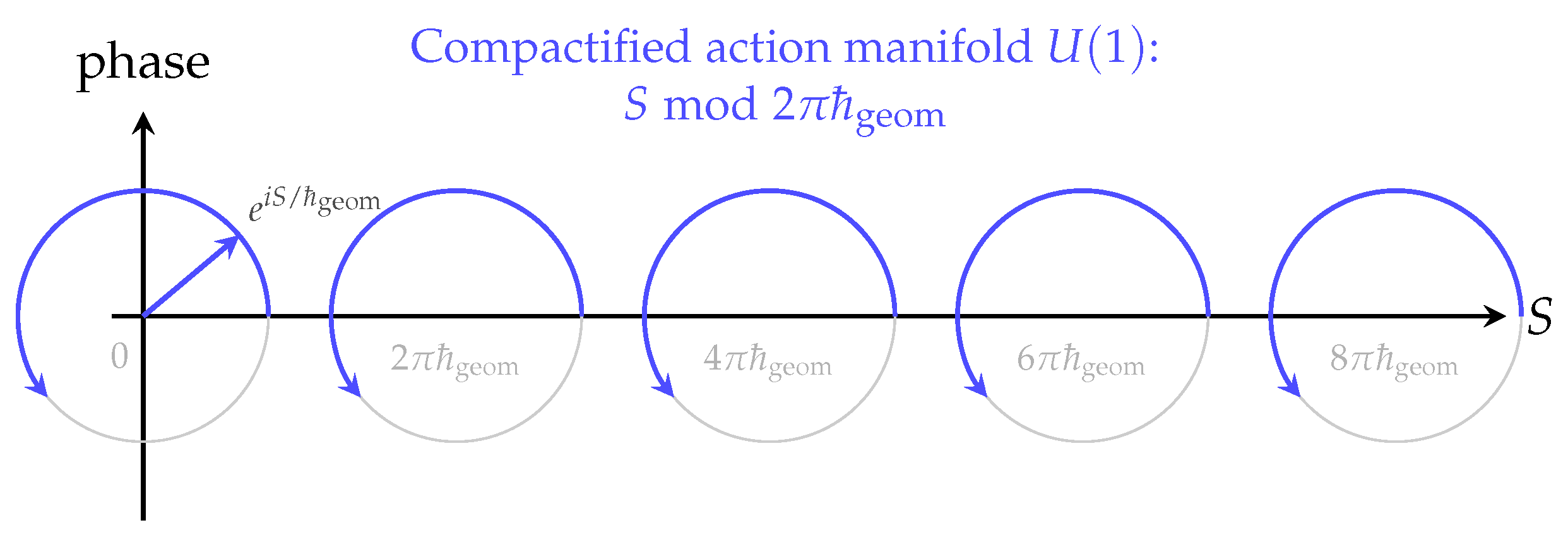

The central observation of this work is that once the action possesses a finite geometric quantum

, its domain is no longer the real line. A quantity identified only up to discrete increments of size

takes values on the compact manifold

so that actions differing by

become physically indistinguishable. On such a compact action manifold, interference is not an added axiom: it is a

mathematical consequence. All observable amplitudes must be class functions on this compact space, and

appears as its natural coordinate map. (See

Appendix H for the geometric origin and decompactification behaviour of the action domain.)

We formulate this as a precise statement (Theorem 4.1):

If the action has a finite quantum , then all transition amplitudes are periodic in S with period , and wave-like interference necessarily follows.

To ground the finite action quantum physically, we draw on Chronon Field Theory (ChFT), a geometric framework in which the fundamental temporal field

carries quantized symplectic twist. The twist two-form

has integral

a topologically protected symplectic flux arising from stabilized chronon solitons (

Appendix C). In this setting, Planck’s constant emerges not as an imposed quantization rule but as the minimal symplectic increment of the underlying causal medium. This aligns with geometric interpretations of quantum phase and holonomy in earlier work on geometric phase and symplectic topology [

11,

31].

A second foundational component is the Real–Now–Front (RNF), the dynamical “alignment front” that converts pre-geometric chronon microstates into the next geometric slice. The RNF operates as a compatibility- and energy-constrained reconstruction map (formal definition in

Appendix B). Its selection of mutually compatible continuations provides the geometric basis for interference, decoherence, and the Born-weighted probability structure developed later in the paper (

Appendix I; cf. decoherence analyses in [

72]).

In this framework, entanglement emerges from global coherence in the internal chronon bundle, carried by vacuum gauge bridges linking the internal states of distant systems.

Taken together, these elements show that quantum interference—often regarded as an irreducible mystery—follows from a single geometric principle: a finite quantum of action equips the action manifold with compact topology, forcing phase periodicity and wave behavior.

The remainder of the paper develops this principle rigorously, connects it to the symplectic structure of ChFT, and explores its physical consequences.

Physical Intuition: Emergent Spacetime, the RNF, and the Geometry of Becoming

The underlying physical picture is not that the universe is filled with a background substance, but that the familiar structures of spacetime and matter arise from the dynamical alignment of a more primitive causal degree of freedom—the chronon field[

41]. In this view, geometry, rods, clocks, and quantum interference emerge from how successive RNF slices are reconstructed. This resonates with broad themes in emergent spacetime research [

9,

51] but introduces two elements typically absent: (i) an operationally defined present, and (ii) a dynamical slice-to-slice reconstruction law.

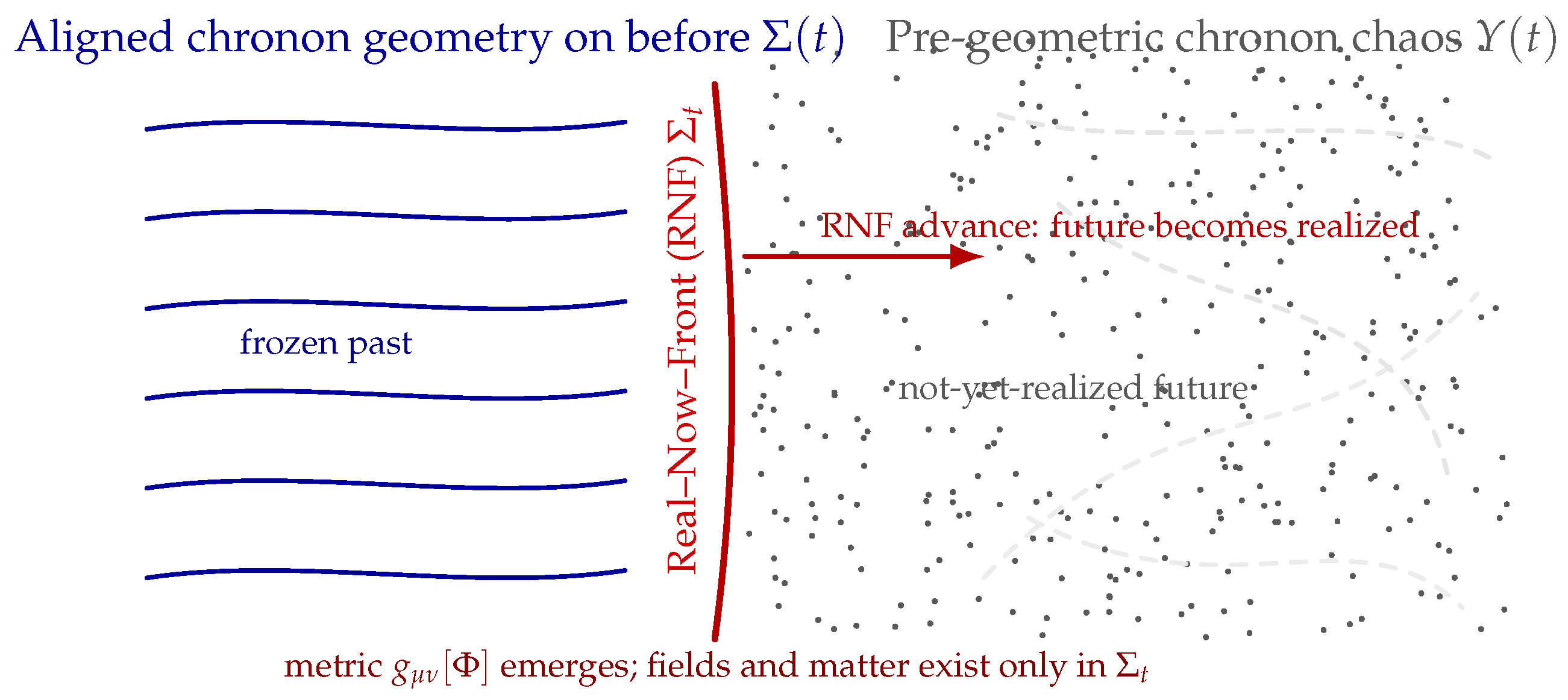

A key point is that the Real–Now–Front (RNF) is not an extra structure inserted into spacetime; rather, the RNF slice is the three–dimensional world we inhabit at each instant. As the RNF advances, it brings the next moment of reality into existence. In the four–dimensional chronon picture, the 3D present is the infinitesimally thin boundary between an aligned geometric past and an unaligned pre–geometric reservoir that has not yet become actual.

This yields a concrete dynamical theory of

Becoming, in contrast to the static block-universe picture criticized in the philosophical and foundations literature [

55,

56]. Instead of a timeless four-dimensional structure, new spacetime is continually generated as the RNF propagates.

A real underlying medium also provides a natural origin for an invariant causal speed. In ChFT, causal disturbances propagate as twist waves of the chronon field, and their velocity is fixed by the material stiffness of the medium, , rather than by kinematic postulate. Photons, massless neutrinos, and gravitational excitations all inherit this same propagation speed, making the universality of c a constitutive property of the medium itself. By contrast, a stage–only spacetime contains no mechanism that enforces a universal causal speed for different probes, even though experiments confirm such universality to extraordinary precision. This gap motivates the search for a dynamical spacetime framework grounded in a physical medium, where the invariance of c emerges from the microscopic structure rather than being imposed by fiat.

Crucially, the Co–moving Concealment Principle (CCP) ensures that the chronon medium’s preferred time direction does

not manifest as observable Lorentz violation. The mechanism is similar in spirit to “emergent Lorentz symmetry” in analogue-gravity models [

9], though implemented here through RNF reconstruction rather than quasi-particle kinematics.

The RNF framework also clarifies several quantum measurement puzzles. Each RNF slice must align chronon–pattern geometries that are compatible with apparatus constraints. Measurement-like selection therefore arises as RNF alignment choosing one compatibility basin during reconstruction, conceptually related to environment-induced selection in decoherence theory [

72]. Nonlocal correlations—including delayed-choice and Bell-type phenomena—admit a natural geometric interpretation when the RNF is treated as a dynamical boundary where pre–geometric degrees of freedom become actual (

Appendix M; cf. [

10]).

The finite quantum of action enters this picture through the chronon medium’s quantized symplectic flux, , which compactifies the action manifold and enforces the universal phase factor . The compact–action theorem proved in this paper is therefore the geometric expression of the chronon medium’s minimal twist.

Importantly the RNF framework yields a concrete mechanism for entanglement: a global internal-bundle coherence structure—an emergent gauge bridge—that enforces nonlocal correlations without violating spacetime locality when the RNF andvances slice by slice.

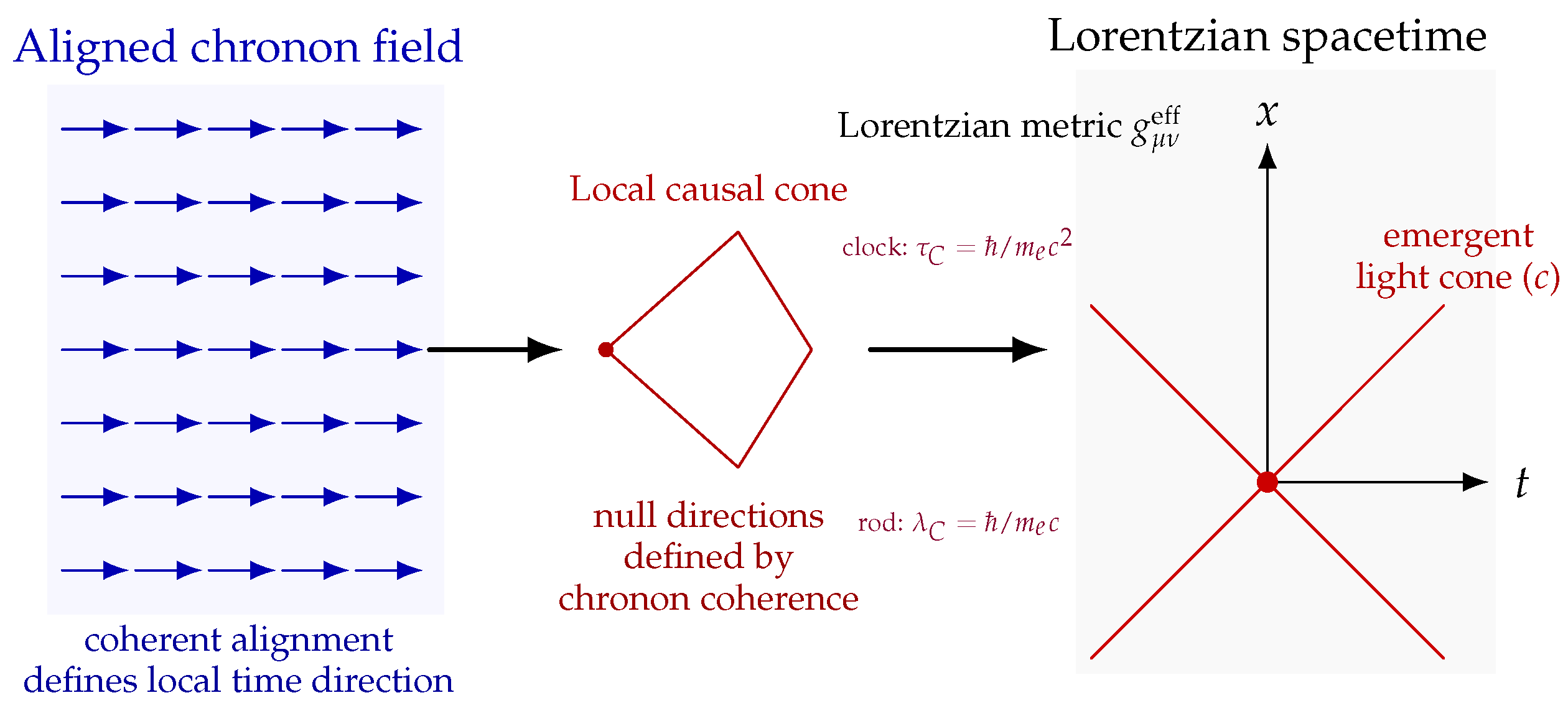

A key phenomenological step in this work is the identification of the electron with the minimal chronon soliton. Its invariant quantum numbers

endow it with a universal Compton wavelength and period [

46], thereby providing intrinsic “rod” and “clock” scales that render the emergent Lorentzian metric operationally meaningful on each RNF slice.

Finally, we discuss the RNF implication for quantum computation and suggests new design principles that may lead to significant improvements.

Taken together, these features—emergent rods and clocks, an invariant causal speed, operational Lorentz symmetry, a dynamical present, and a geometric view of quantum measurement—position the compact–action/RNF framework as a coherent alternative to both block-universe models and standard quantum foundations.

Summary of contributions.

This work develops a single geometric framework in which spacetime, quantum behaviour, and particle phenomenology emerge from the dynamics of a chronon medium and its advancing Real–Now Front (RNF). Our main contributions are: (i) a compact–action formulation showing that quantum phases, the path–integral structure, and Schrödinger dynamics follow from RNF compatibility; (ii) a reconstruction-based account of measurement yielding the Born rule and macroscopic definiteness without external collapse postulates; (iii) a topological soliton sector in which twist defects realize fermionic degrees of freedom and curvature integrals determine particle masses and charges; and (iv) a horizon-alignment mechanism demonstrating exponential suppression of Hawking-like emission together with fully information-preserving black–hole evolution.

2. Foundations of Chronon Field Theory and the Temporal Coherence Principle

Chronon Field Theory (ChFT) supplies the physical substrate and mathematical structures from which the compact–action geometry developed in this paper arises[

41,

42]. Only the minimal ingredients required for the main results are summarized here. Detailed derivations and the full TCP formalism appear in the appendices: the configuration space and twist structure in

Appendix A, the symplectic quantization mechanism in

Appendix C, and the RNF reconstruction map in

Appendix B.

ChFT is built on a single dynamical variable: a smooth, unit timelike covector

interpreted as the local orientation of physical time. No background metric is assumed microscopically; spacetime geometry appears only after sufficient alignment of

, in line with broader ideas in emergent-gravity and analogue-gravity frameworks [

9,

51].

2.1. The Temporal Coherence Principle

The dynamics of are governed by the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP):

The chronon field evolves so as to maximize local temporal alignment while suppressing incoherent twist and curvature.

The TCP is implemented by the action summarized in

Appendix A, consisting of (i) a quadratic alignment term, (ii) an antisymmetric “twist’’ term measuring non-integrability (analogous to vorticity and spin-connection curvature [

31]), (iii) a quartic stabilization term that prevents Derrick collapse and ensures finite–energy solitons [

23,

46], and (iv) a norm constraint enforcing

.

Variation of this action yields the unified TCP field equation,

where the nonlinear term

collects contributions from quartic gradients and enforces soliton stability.

In regions of low twist and curvature, these equations admit aligned solutions for which

defines a coherent time direction and an effective Lorentzian metric emerges from the induced polarization frame. Thus the fundamental structure of ChFT is not a pre-existing metric but a dynamical causal field whose coherence properties

generate geometry, echoing themes in hydrodynamic and analogue-emergent metrics [

9,

64].

2.2. Emergent Metric and Causal Structure

A spacetime metric appears only on sufficiently aligned regions, typically those already reconstructed by the RNF[

41]. On such slices,

determines parallel and transverse directions. The spatial projector

is therefore not a background structure but an artifact of successful alignment.

Linearizing the TCP equation around a coherent background yields, at long wavelengths, an effective Lorentzian metric

which governs the characteristics of small perturbations. Such emergent causal cones are standard in analogue-gravity systems and effective-field-theory treatments of Lorentz symmetry [

43].

Matter excitations correspond to finite–energy solitons stabilized by the quartic term, and both solitons and polarization waves propagate according to (

3). Thus relativity appears as a hydrodynamic limit of chronon coherence, not a microscopic postulate. See

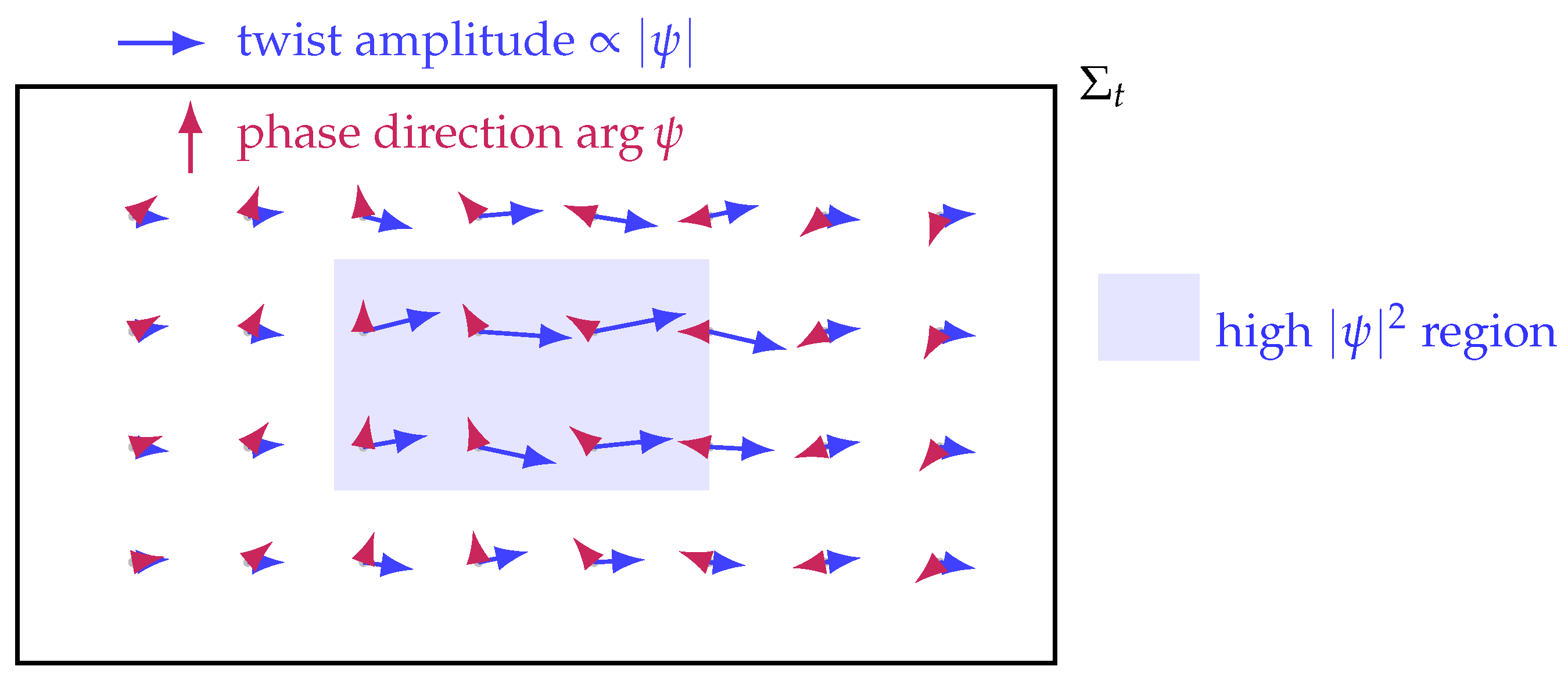

Figure 1 for an illustration.

2.3. Gauge Sectors from Polarization Holonomy

The polarization directions transverse to

form a naturally symplectic two–dimensional bundle. Parallel transport of polarization along aligned chronon trajectories induces a connection

where

projects onto directions orthogonal to

. Connections arising from internal frame transport are standard in geometric and gauge–theoretic formulations [

31,

48].

In the geometric limit (

Appendix D), the curvature of this connection obeys equations with the same structural form as Yang–Mills dynamics, with the effective gauge group determined by the topology of the polarization fibers. The appearance of abelian and nonabelian sectors through bundle holonomy parallels familiar mechanisms in fiber–bundle gauge theory [

13,

48]. The abelian component yields electromagnetism; higher–rank sectors arise naturally from nontrivial holonomy of the polarization bundle.

Thus gauge interactions appear as emergent geometric effects of polarization twist, not as independent microscopic fields to be quantized[

42].

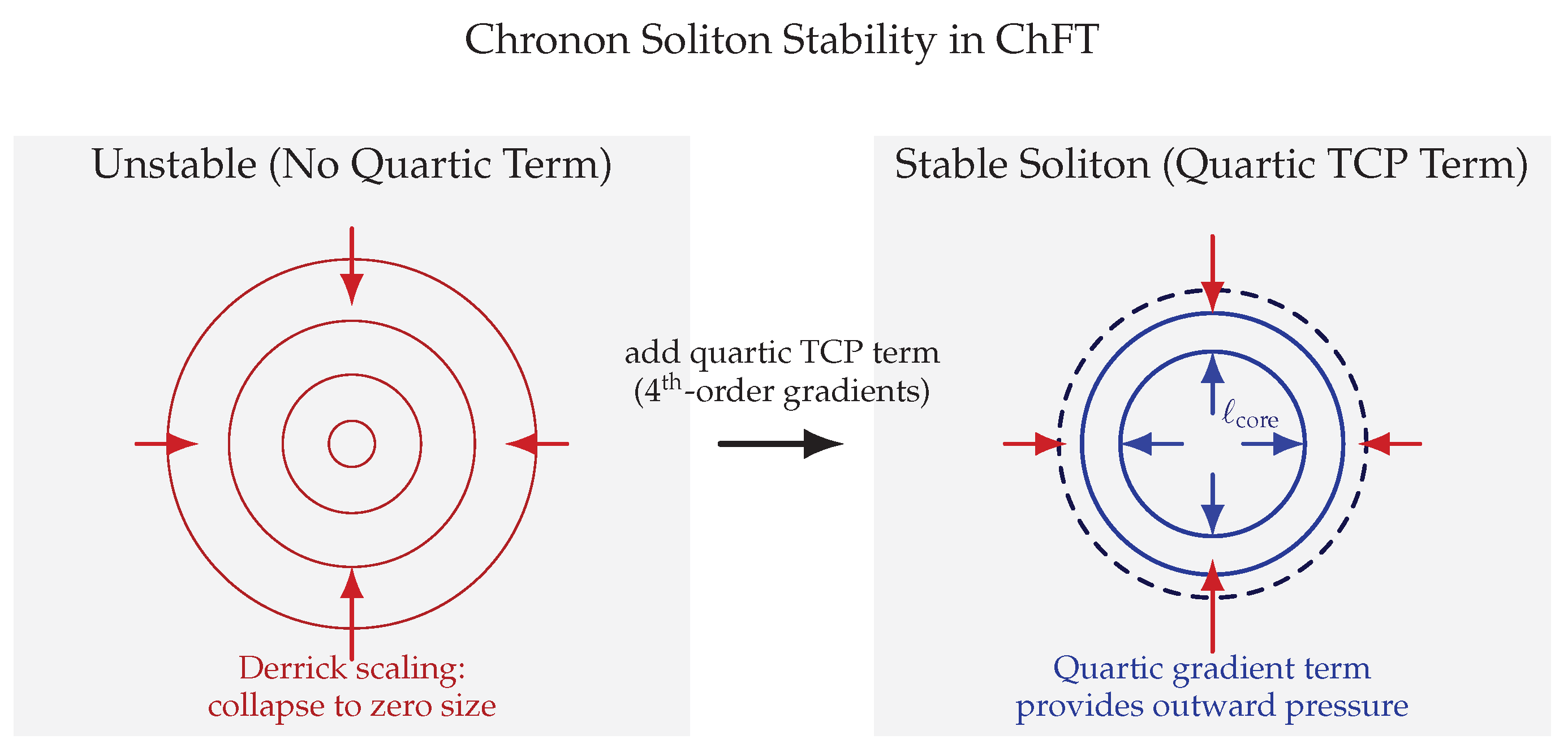

2.4. Solitons, Finite Energy, and Symplectic Quantization

Chronon Field Theory admits localized, finite–energy excitations of the temporal field

, which play the role of particle–like entities in the emergent spacetime. These configurations—chronon solitons—arise because the TCP action contains both quadratic alignment terms and quartic stabilizing terms. As shown in

Appendix F, the quartic terms prevent Derrick collapse [

23] and fix a preferred soliton core size

ensuring that finite-energy, finite-radius solutions exist and remain stable, as in standard topological–soliton models [

46].

A central geometric feature of these solitons is the antisymmetric gradient of the causal field,

which encodes the twist of the polarization frame. Finite-energy boundary conditions compactify spatial infinity to

, so the soliton defines a map

whose degree is an integer, as in classic examples of topological charge [

46,

48]. This leads to a quantized symplectic flux,

derived in

Appendix C. The integer

n is the soliton’s topological charge, and the flux unit

is a geometric invariant fixed by the chronon medium.

Thus solitons provide a natural candidate for the microscopic origin of a finite quantum of action.

Their conserved, quantized flux is what compactifies the action manifold, enables the phase rule

, and ultimately gives rise to interference and the quantum behavior developed in

Section 4,

Section 5,

Section 6 and

Section 7.

2.5. Mass in Chronon Field Theory: Localization, Curvature, and Energy

In Chronon Field Theory (ChFT), “mass’’ is not a fundamental parameter but a derived property of how excitations of the chronon medium are supported. The theory distinguishes sharply between delocalized twist waves (intrinsically massless) and localized defects of the polarization bundle (intrinsically massive).

Three structural principles determine the ChFT notion of mass.

(1) Mass originates from the energy needed to localize an excitation.

To maintain a static, finite-size chronon defect, the polarization field must sustain both curvature and vorticity. The rest energy of a stationary soliton

is the curvature functional

where the quadratic term measures alignment stiffness and the quartic Skyrme-like term provides stabilization against collapse. The soliton’s rest mass is the usual ratio

with

the universal causal speed of twist waves. Thus mass in ChFT is the

energy cost of localization: only excitations that require bounded curvature to remain finite carry mass.

(2) Linear twist waves are intrinsically massless.

Small-amplitude distortions of the chronon polarization frame satisfy the linear dispersion relation

admitting no static configuration and no curvature core. Such excitations neither localize nor store curvature energy, and so their rest mass vanishes. The photon (and any other pure transverse twist wave) is massless for this reason—not due to symmetry breaking, but because it is delocalized.

(3) Massive bosons correspond to localized polarization defects.

Any excitation of the polarization bundle that cannot propagate as a delocalized wave necessarily forms a localized core and therefore acquires mass through the same curvature functional as fermionic solitons. This yields a geometric reinterpretation of the electroweak sector:

the photon is a pure twist wave () and massless;

the correspond to charged () vector solitons with internal SU(2) curvature;

the is a neutral () but topologically nontrivial SU(2) polarization soliton.

Their masses are the curvature energies of their respective localized cores. Thus the Higgs mass term of the Standard Model is re-interpreted in ChFT by the geometry and stability of localized polarization defects.

Our approach is in a manner analogous to other geometric derivations based on envariance [

53].

(4) Boosted solitons reproduce the standard relativistic mass–energy relation.

A moving soliton corresponds to its localized curvature profile following the RNF advance. Because RNF reconstruction induces an emergent Lorentz metric with causal speed

, the energy of a boosted soliton satisfies

with no additional postulates required. The usual relativistic mass–energy structure therefore follows from the covariant form of the TCP action and the RNF geometry.

Unified picture. In ChFT, mass is a

localization energy: only excitations that require bounded curvature to remain finite acquire mass. Linear twist waves are massless; localized solitons (fermionic or bosonic) are massive; and boosted solitons follow standard relativistic mass–energy scaling. The electron, as discussed in

Section 8, as the minimal

soliton, is the simplest such massive defect.

Limitations and future work. A complete quantitative treatment of the bosonic soliton sector, including the detailed SU(2) polarization geometry and mass hierarchy, requires solving the full nonlinear TCP equations with internal gauge structure. This lies beyond the scope of the present work and will be developed in future studies.

2.6. Lorentz Invariance and the Co–Moving Concealment Principle

All observable excitations—solitons, photons, and polarization waves—are built from perturbations of itself. Thus they co-move with the chronon field, making any microscopic anisotropies dynamically unobservable. This yields the Co–Moving Concealment Principle (CCP):

Local observers constructed from chronon excitations can access only the emergent metric , not the underlying microstructure of .

Since all rods, clocks, and signals use the same chronon-based internal structure, they share the same limiting speed , guaranteeing operational Lorentz invariance. Short-scale deviations are washed out by co-moving concealment and remain experimentally invisible.

Thus Lorentz symmetry is not fundamental; it is the universal hydrodynamic limit of chronon coherence.

3. The Real–Now–Front as the Generator of Spacetime

Chronon Field Theory (ChFT) distinguishes two layers of structure: (i) a pre-geometric chronon medium with no metric, spatial relations, or propagating fields, and (ii) an aligned geometric domain in which spacetime, rods, clocks, solitons, and field excitations exist. The boundary between these regimes is the Real–Now–Front (RNF), a dynamical surface across which the chronon field first achieves alignment. The RNF is therefore the locus at which each new moment of physical reality is constructed.

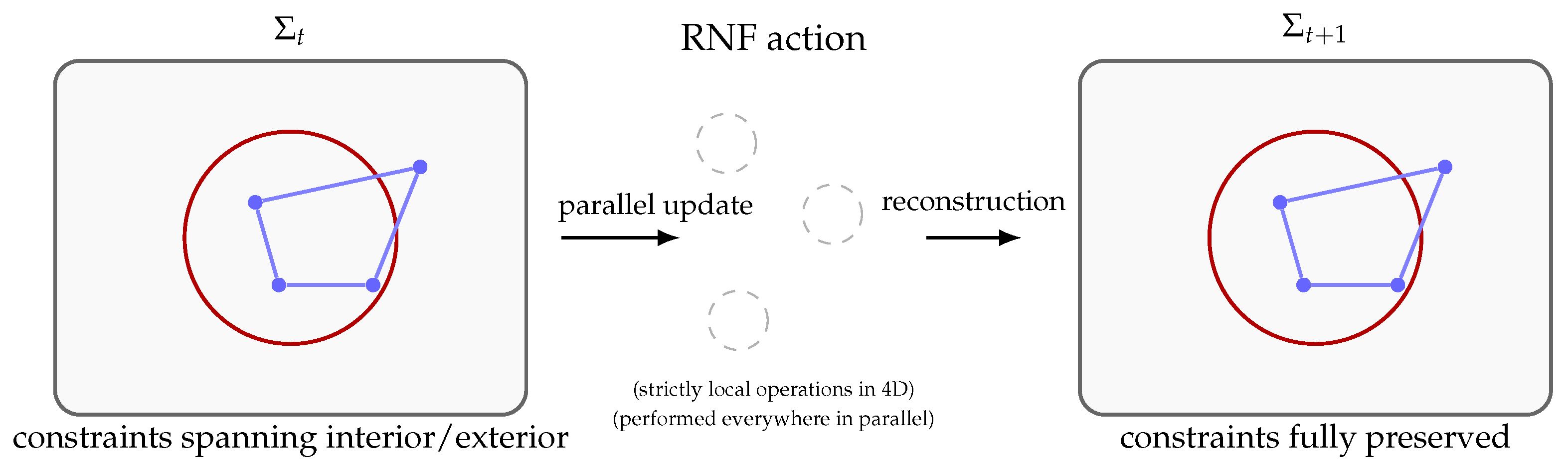

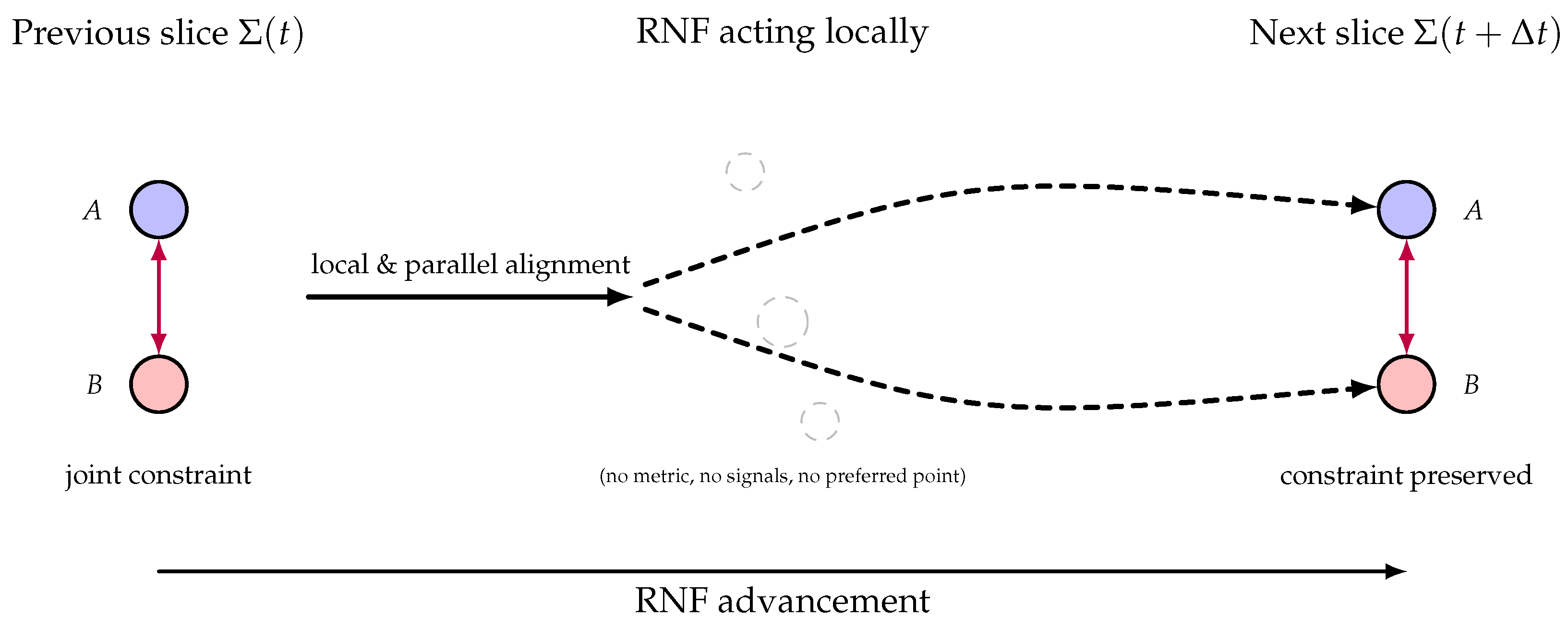

This section develops the RNF as a purely geometric reconstruction dynamics. The RNF converts pre-geometric microstates into an aligned metric slice, propagates matter and fields, and implements the selection of compatible pattern continuations. Its action is strictly local but applied everywhere in parallel, giving it the capacity to preserve global structures such as entanglement without requiring additional nonlocal mechanisms.

3.1. RNF Slices and the Structure of Becoming

Aligned configurations of the chronon field

define an effective Lorentzian metric

so any hypersurface on which

is aligned constitutes a geometric slice

: a three-dimensional “present’’ endowed with spatial structure.

Ahead of

lies the pre-geometric reservoir

: an unrealized domain of chronon microstates with no metric, adjacency, or curvature. Behind the slice lies the frozen aligned past. The RNF is the infinitesimal boundary separating these domains:

The step is not evolution within a pre-existing spacetime. It is the construction of a new slice by local alignment of chronon microstates. The RNF thereby provides a fully dynamical account of Becoming: physical reality is continually generated slice by slice.

3.2. Local RNF reconstruction

For each point

x on the next slice

, the RNF applies a local reconstruction map

where

is the portion of the pre-geometric reservoir that influences alignment at

x.

Two structural principles determine :

Local TCP minimization. Among all candidate microstates in , the RNF aligns the one that minimizes the local TCP energy density.

Compatibility with the existing pattern. A microstate can be aligned at x only if it consistently extends the twist, polarization, and curvature data of the configuration on . Microstates that cannot be made compatible with by any local deformation are excluded.

These rules preserve structure entirely through local chronon dynamics, without any propagation of amplitudes or signals across the slice.

Simultaneous local reconstruction in 4D.

Because the RNF is a four-dimensional alignment boundary, it has no preferred reconstruction point. All maps act simultaneously across the advancing hypersurface, each using only its own local pre-geometric data. From within a 3D perspective this appears miraculous, but in 4D it is simply a parallel update rule acting on the entire RNF. The new geometric slice therefore emerges in a single step: locally reconstructed at every point, yet globally restoring all correlations “in one act.’’

3.3. Transport: How Patterns Move Across Slices

The reconstruction rules above determine

which microstates may be aligned, but do not yet specify

where each part of the pattern reappears. Motion and wave propagation arise from a transport map

obtained by minimizing the incremental TCP energy subject to compatibility with

.

A pattern element at

x is reconstructed at

where

is the emergent shift vector. Transport and reconstruction are tightly coupled: the RNF aligns

using the microstates near

and the local compatibility inherited from

via

.

This yields:

Soliton motion. A moving soliton is simply a localized curvature pattern translated by .

Wave propagation. Linear twist excitations correspond to coherent regions of the shift vector, producing the usual dispersion .

Constraint preservation. Global constraints—entanglement, holonomy, topological flux—are preserved because the entire constraint structure on

is locally encoded (

Section 6 and

Appendix B) and reconstructed everywhere in parallel.

is already a local representation of its own global constraint structure.

3.4. The RNF Entanglement Preservation Theorem

The local and parallel nature of RNF reconstruction gives rise to a powerful structural result:

Theorem 3.1 (RNF Entanglement Preservation).

Let be an aligned slice containing a pattern with a global constraint structure Γ (such as entanglement relations, polarization holonomy, or topological flux). Let be the RNF reconstruction operator and the transport map. Then the RNF update preserves Γ exactly:

Sketch of proof. Global constraints are locally encoded in the structure of . RNF reconstruction is (i) strictly local, (ii) applied in parallel to all x, and (iii) restricted to microstates compatible with . Thus each constraint in is re-imposed at every point, yielding exact preservation even across horizons or disconnected regions of the emergent metric.

3.5. RNF as a Primitive Selection Mechanism

The RNF provides a physical mechanism for pattern persistence and pattern elimination without invoking collapse or decoherence postulates:

Persistence. A soliton or field pattern persists only if every local RNF update admits compatible microstates; otherwise the pattern cannot be reconstructed.

Environmental selection. Macroscopic apparatus patterns impose strong compatibility constraints: if an incoming pattern is compatible with only one macroscopic continuation, all others are excluded.

Suppression of incompatible alternatives. If two candidate continuations have disjoint compatibility sets, the RNF cannot reconstruct both. Incompatible alternatives are eliminated geometrically.

These effects arise from the chronon dynamics and the TCP energy, not from Hilbert-space projection or observer-dependent collapse.

3.6. Summary

The RNF is the dynamic boundary where pre-geometric chronon microstates are converted into coherent geometric structure.

Local reconstruction and parallel application across the slice generate the entire next moment of spacetime in a single step.

A transport map governs motion, wave propagation, and the location of reconstructed structures.

Global constraints—including entanglement—are preserved automatically by the RNF Entanglement Preservation Theorem.

Compatibility-driven reconstruction provides a geometric origin for pattern persistence, selection, and macroscopic definiteness.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the RNF is therefore the fundamental generative mechanism of ChFT: the process that builds spacetime, transports matter and fields, preserves global correlations, and selects the patterns that constitute physical reality.

4. Finite Quantum of Action: Compact Geometry and Wave Interference

A defining prediction of ChFT is the quantization of symplectic flux carried by any finite–energy chronon configuration. As shown in

Appendix F, the twist two-form

satisfies the quantization condition

for every closed loop

lying in an aligned region. The quartic term in the TCP action prevents continuous untwisting, forcing the flux to take discrete values. This is the same geometric mechanism underlying Dirac charge quantization [

24] and the topological quantization of winding in nonlinear sigma models [

46].

The existence of this minimal symplectic quantum has a profound and unavoidable consequence: the classical action becomes a

compact variable. Configurations whose actions differ by

cannot be distinguished by any geometric or dynamical process. The action thus lives on a

manifold, and interference follows as the unique geometric law governing the composition of compact phases, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

4.1. Compactification of the Action Manifold

In conventional mechanics the action

S takes values in

. In ChFT, a deformation that adds one unit of symplectic twist changes the action by

The two configurations differ by a topological sector of the chronon field, but all their geometric and dynamical properties coincide. They belong to the same compatibility class and cannot be distinguished by any physical measurement or any RNF reconstruction process.

Therefore the physical action takes values in the compact space

The natural coordinate on this circle is the unitary phase

the same object that appears in the Feynman path integral [

28,

57]. Here it is not postulated but

forced by the geometry of the underlying chronon field.

4.2. The Finite–Action Interference Theorem

The compact action manifold (

7) leads to a unique interference law.

Theorem 4.1 (Finite Action Implies Interference).

Let physically distinguishable histories be labeled by their action modulo . Then the detected intensity for two alternatives with actions must take the form

for apparatus-dependent constants .

Sketch.

The compact group

has only the characters

. Smoothness and normalization restrict physical weights to

. Thus for two histories,

No other interference form is compatible with the compact geometry.

Interpretation.

Wave behaviour is a geometric necessity, not a postulate. Distinct trajectories correspond to points on , and their combined effect is determined by angle addition on a circle.

4.3. RNF Interpretation: Modular Action and Compatible Histories

The RNF does not use the absolute action

S but only its compactified class

. Actions that differ by an integer multiple of

belong to the same compatibility set:

Thus the RNF propagates every geometrically compatible pattern continuation, each weighted by the phase (

8). Summing these contributions gives the RNF analogue of the Feynman sum-over-histories:

Interference is therefore not a property of waves but the geometric consequence of compact action combined with RNF compatibility.

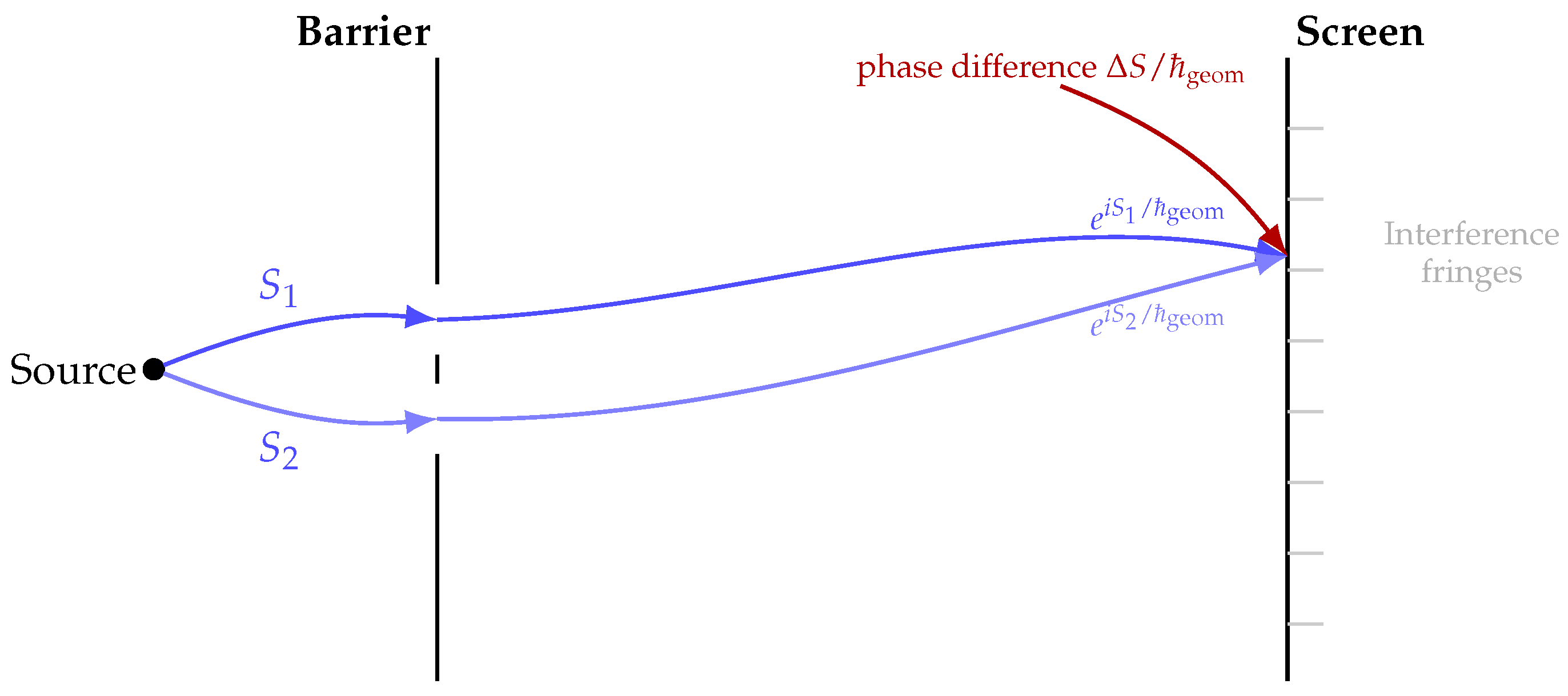

4.4. Double–Slit Interference as Compact Action Geometry

In the double–slit configuration the post-slit domain admits two compatible pattern classes

and

. They contribute phases

and

, so the RNF reconstructs the combined pattern

The detected intensity is

When which-path information is imposed, apparatus alignment constraints eliminate the overlap of compatibility sets, leaving only one admissible continuation. The interference term disappears automatically, without any collapse axiom, as demonstrated in

Figure 4.

4.5. Summary

A finite quantum of action compactifies the action manifold into . This compact geometry forces:

modular equivalence of actions differing by ,

representation of trajectories by unitary characters,

coherent sums of compatible RNF histories, and

interference with period .

Wave behaviour is therefore the geometric manifestation of finite action, not an added axiom. Compact action makes interference inevitable, and the RNF supplies the local mechanism by which compatible modular histories combine.

5. Interference, Measurement, and Compatibility Collapse

With the compact action geometry established in

Section 4, RNF reconstruction naturally produces two distinct behaviours:

1. Coherent combination of compatible modular histories (interference), and

2. Elimination of incompatible histories (collapse / measurement).

Both arise from a single mechanism: the RNF propagates all and only those chronon-pattern continuations whose microstates remain jointly compatible with the existing aligned pattern and any apparatus-imposed constraints. This section unifies interference and measurement under this single compatibility principle.

5.1. Modular Action and Compatible Pattern Continuations

Let

be a chronon-pattern continuation from an initial point to a point

x on the next RNF slice, with TCP action

. Compactification of the action (

Section 4) yields the equivalence relation

whenever the two patterns differ by one unit of symplectic twist. Patterns in the same modular class correspond to windings on the same

action circle.

Let

denote the pattern associated with

. The RNF can propagate all of them precisely when their compatibility sets overlap:

When this overlap is nonempty, the RNF treats all such patterns as admissible continuations of the aligned slice.

Thus the familiar sum-over-histories expression,

is not a postulate but a compact description of RNF dynamics acting on modular action classes.

5.2. Interference From Multiple RNF-Allowed Histories

Suppose two pattern continuations

and

both satisfy (

11). Their RNF-aligned contributions differ only by the modular action

Because the action lives on , the RNF cannot eliminate either continuation; both are propagated with relative phase .

The resulting field on the next slice is

and the intensity depends on the cosine of the modular phase difference, exactly as derived in the finite-action interference theorem (

Section 4).

Wave-like behaviour is therefore not a separate ontological mode but the RNF’s geometric response to multiple simultaneously compatible pattern continuations on a compact action manifold.

5.3. Measurement as Compatibility Filtering

A measurement apparatus is a macroscopic chronon configuration with a highly rigid alignment structure and well-defined coherence domains. Let

denote the incoming soliton pattern and

the apparatus pattern. The RNF alignment map

(

Appendix B) is defined only on microstates belonging to the joint compatibility set

If several pattern continuations lie in this intersection, the RNF propagates all of them coherently (interference). If the intersection contains exactly one pattern class (up to modular phase), the RNF has no freedom: it must propagate that class. This is compatibility collapse. No additional collapse postulate is needed.

5.4. Decoherence and the Elimination of Incompatible Histories

Environmental interactions impose further alignment constraints that reduce the overlap of compatibility sets. For two competing patterns

, coherence is possible only if

If environmental or apparatus structure drives this overlap to zero,

then the RNF cannot reconstruct both patterns on the same slice: one survives and the other becomes unreconstructible. This geometric elimination corresponds to decoherence-induced collapse in the standard formalism.

Thus decoherence is the process that shrinks compatibility overlap, while RNF compatibility provides the sharp condition that determines when interference must cease.

5.5. Born Weights and the Classical Limit

When many compatible histories contribute, the RNF-aligned field carries relative weights proportional to the stability volumes of their compatibility sets. In the continuum limit these volumes reproduce the standard Born weights, as shown in

Appendix I (Theorem S1), where

In the macroscopic limit, apparatus constraints sharply localize these volumes, leaving exactly one dominant compatibility basin. The RNF then propagates a single classical trajectory, recovering definite outcomes and classical behaviour.

5.6. Summary

Compact action forces patterns with modularly equivalent action to coexist as admissible continuations.

RNF propagation combines all pattern continuations that remain jointly compatible with the existing aligned slice.

Interference arises from RNF-aligned contributions of multiple compatible histories with relative modular phases.

Measurement corresponds to additional apparatus constraints that restrict compatibility to a single pattern class.

Decoherence occurs when environmental structure eliminates the overlap of compatibility sets.

Collapse, definiteness, and the Born weights emerge from the geometry of compatibility, not from extra dynamical axioms.

Interference, measurement, and classical definiteness therefore share the same geometric origin: RNF reconstruction acting on chronon patterns with compact action and quantized symplectic structure.

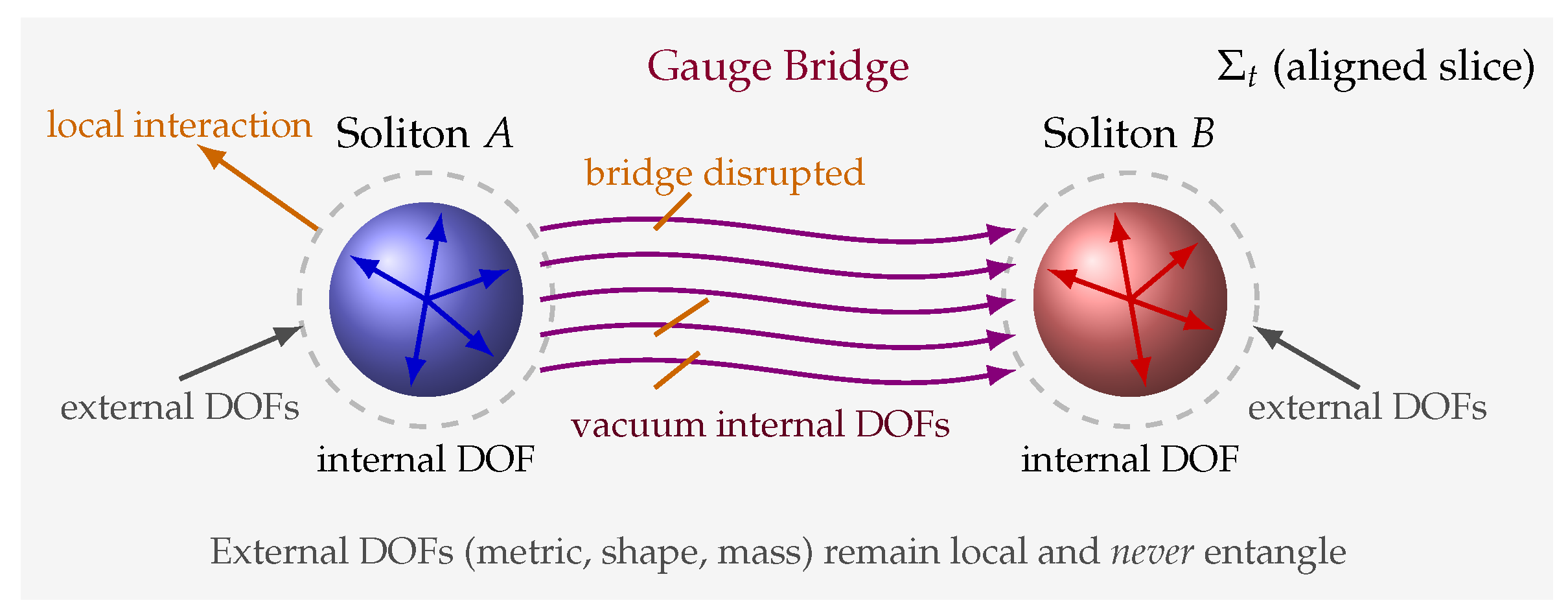

6. Entanglement as Internal-Bundle Gauge Bridges

The RNF/ChFT framework offers a natural resolution to the longstanding question of how entangled systems separated by spacelike intervals can retain perfectly correlated behavior without violating emergent spacetime locality. The key insight is that the chronon field carries internal degrees of freedom—polarization, twist, modular-action phase, and gauge-like orientation—which are distinct from the external degrees of freedom associated with the emergent metric, soliton geometry, and classical field content. These internal DOFs form a gauge-like fiber bundle over each RNF slice , with local frames determined by the polarization and phase structure of the chronon medium.

A crucial empirical fact motivates this identification. Across more than eight decades of experimental quantum physics,

all observed entanglement phenomena involve internal degrees of freedom—most famously spin and polarization in Bell tests [

7,

71], internal atomic levels in Rydberg and trapped-ion experiments [

47], and flavor or mode indices in optical and particle settings.

No experiment has ever demonstrated robust entanglement of external classical properties such as mass, spatial size, geometric shape, classical energy, classical frequency, or curvature. This sharp separation between “entangleable” and “non-entangleable” quantities—recognized since Schrödinger’s original analysis of non-separable internal-state correlations [

59]—mirrors exactly the RNF distinction between internal and external chronon DOFs. The RNF framework explains this otherwise puzzling empirical dichotomy: only internal DOFs live in a global bundle structure that can support the nonlocal coherence patterns characteristic of entanglement.

In this section we show that quantum entanglement corresponds to a global constraint pattern in the internal chronon bundle, which we call an internal-bundle gauge bridge (or simply a gauge bridge). Unlike solitons, which are topologically protected excitations in the external configuration of the chronon field, gauge bridges are non-topological, global defects in the internal bundle geometry. They carry no energy, produce no curvature, and do not modify the external metric structure. However, they impose strict constraints on the RNF reconstruction of internal chronon DOFs across , thereby enforcing the correlations characteristic of entangled states.

6.1. External vs. Internal Degrees of Freedom

Each chronon carries two classes of DOFs:

External DOFs: the alignment and curvature data that give rise to the emergent Lorentzian metric, soliton cores, and macroscopic fields. These DOFs obey emergent locality and are governed by the coherence of the temporal field . No experiment has ever observed entanglement of purely external DOFs such as mass, size, classical energy, position shape, or curvature, reflecting the fact that external DOFs cannot support nonlocal compatibility constraints in RNF.

Internal DOFs: the polarization, twist, and compact-action phase associated with each chronon. These form a local gauge-like fiber (typically an or -type internal space) above each point of . They are invisible to classical observables but essential for modular-action interference and RNF compatibility reconstruction. All experimentally confirmed instances of entanglement occur exclusively within this class of DOFs.

The distinction parallels—but is more physically grounded than—the separation between base-space geometry and internal gauge spaces in Yang–Mills theory. In RNF/ChFT, however, these internal bundle structures determine not only the long-wavelength gauge interactions but also the global coherence patterns responsible for quantum entanglement.

6.2. Definition of a Gauge Bridge

Consider two solitons A and B supported on disjoint regions of . We define a gauge bridge between A and B as a global constraint on the internal chronon bundle satisfying:

The bridge imposes a non-factorizable relation between the internal DOFs of A and B, matching the empirical fact that only internal DOFs are observed to entangle.

The constraint is encoded in the internal DOFs of the vacuum chronons spanning the region between A and B.

No topological charge protects the bridge; it is stabilized purely by internal-bundle coherence.

The constraint is preserved by the RNF update if and only if the local compatibility sets of the internal DOFs remain jointly consistent.

A spin singlet provides a canonical example. On

the internal-bundle polarization fields encode the antisymmetric constraint

where

are the internal polarization vectors in the fiber above the soliton cores. This relation is implemented not by a physical “string” or flux tube connecting the solitons, but by a synchronized internal-bundle polarization pattern extending throughout the vacuum region. Although energetically trivial, the pattern places global restrictions on allowed chronon microstates and therefore on RNF-compatible reconstruction paths.

6.3. Preservation and Destruction of Gauge Bridges

Gauge bridges are inherently non-topological. Unlike solitons, whose topological winding protects their identity, gauge bridges rely entirely on global coherence of the internal chronon bundle. As a result, they are fragile: any local interaction that enforces an incompatible alignment of internal DOFs destroys the global pattern.

Formally, let denote the internal-bundle constraint defining the gauge bridge. The RNF update from to preserves if and only if the local compatibility sets at every point admit a continuation that satisfies the global constraint. A measurement, scattering event, or environmental coupling introduces new local alignment constraints that may render the global pattern incompatible. In this case, the RNF update cannot reconstruct , and the gauge bridge collapses in a single step.

This mechanism provides a physically concrete account of decoherence: entanglement decays when environmental interactions disrupt the coherent internal-bundle polarization pattern of the vacuum, eliminating the conditions required for RNF to reconstruct the global constraint.

6.4. Entanglement as a Gauge-Theoretic Phenomenon

Gauge bridges reveal entanglement as a fundamentally gauge-theoretic phenomenon. The nonlocal correlations originate not from the geometry of emergent spacetime but from the global coherence of the internal DOFs of the chronon field. The RNF propagates these correlations because the internal bundle over carries a global constraint pattern that restricts how internal DOFs can be reconstructed across the slice. When the pattern is intact, entanglement persists; when the pattern is disrupted, the RNF must select a locally compatible continuation and the bridge disappears.

Thus, entanglement is neither mysterious nor fundamentally spacetime nonlocal: it is a

global internal-bundle constraint enforced by RNF reconstruction, closely analogous to parallel-transport constraints and holonomy structures in gauge theory but realized in a spacetime-emergent medium. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the empirical restriction of entanglement to internal DOFs is therefore not accidental but reflects the fundamental structure of the chronon field: only internal DOFs inhabit the bundle geometry capable of supporting gauge bridges, while external DOFs remain strictly local and classically reconstructible.

6.5. Vacuum Capacity of the Internal Bundle

Mathematically, the distinction between external and internal DOFs can be encoded as a splitting of the chronon configuration space on each RNF slice

. Let

denote, respectively, the spaces of external and internal field configurations, where

is the internal (gauge-like) bundle and

its space of smooth sections. A full RNF configuration can then be represented as a pair

The

vacuum external sector is defined by fixing a background metric and soliton content,

so that all remaining dynamical freedom resides in the internal configuration

. Since

has fiber dimension

at each

, the space

is an infinite-dimensional function space even when

is held fixed. In particular, the subset corresponding to a fixed finite collection of solitons,

still forms an infinite-dimensional manifold of sections that agree with the required internal data near

A and

B but remain unconstrained on the surrounding vacuum region.

A

gauge bridge between

A and

B can then be represented as a nontrivial constraint submanifold

defined, for example, by a functional relation

that links the internal DOFs of

A and

B via their continuation through the vacuum. Because

is infinite-dimensional while

is specified by finitely many global constraints, the vacuum internal bundle has ample capacity to support such global patterns without exhausting its available DOFs.

In this sense, the aligned vacuum possesses a large reservoir of internal-bundle degrees of freedom: fixing the external configuration and a finite set of solitons places only mild constraints on , leaving an infinite-dimensional family of internal configurations available to realize gauge bridges. Entanglement corresponds precisely to the RNF selection of configurations within such constraint manifolds .

Consequently, the RNF/ChFT framework predicts the complete absence of gravitational entanglement, since the external metric sector cannot support internal-bundle gauge bridges.

7. Beyond Schrödinger Dynamics: RNF Quantum Mechanics

A viable reformulation of quantum theory must recover standard quantum mechanics in the experimentally tested regime while offering deeper explanatory structure. In the RNF/Chronon Field Theory (ChFT) framework, this recovery is not imposed but follows from two geometric facts:

(1) a finite quantum of action

compactifies the action manifold and enforces phases of the form

, the same structure that underlies the Feynman path-integral phase rule [

28];

(2) RNF reconstruction restricts propagation to families of chronon configurations whose actions lie in the same modular class, paralleling the topological equivalence classes in action-based formulations [

57].

Measurement, entanglement, and macroscopic definiteness arise from the geometry of compatibility basins and the structure of the pre-geometric domain. Where tested, the RNF predictions agree with standard quantum mechanics; where standard QM provides no mechanism, the RNF supplies geometric explanations.

7.1. Compact Action and the Quantum Phase

Section 4 and

Appendix C establish that a finite symplectic flux quantum carried by chronon solitons identifies action values modulo

, as in topologically restricted path integrals [

57]. The only continuous characters on the compact action manifold

are

precisely the quantum phase structure found in geometric formulations of interference [

11]. Thus the phase rule of quantum mechanics arises naturally from compact action.

7.2. RNF-Compatible Families and the Path Integral

The RNF advances by reconstructing the chronon field in a thin shell ahead of the aligned region. Only pattern geometries whose actions fall within the same modular class remain RNF-compatible:

The reconstructed field at

is therefore

matching the Feynman sum-over-histories restricted to RNF-admissible trajectories [

28]. The RNF composition law produces the usual propagator convolution.

7.3. Recovery of the Schrödinger Equation and RNF Corrections

Appendix J shows that, for slowly varying potentials and long-wavelength solitons, the RNF composition law reduces to Schrödinger evolution:

The RNF framework predicts small corrections arising from:

nonlocality of RNF reconstruction on soliton-core scales;

quartic TCP terms modifying dispersion;

higher-order curvature of the compact action manifold.

All corrections are suppressed by the alignment scale , leaving standard QM an excellent low-energy limit.

7.4. Wave Function as a Twist–Phase Field on

Once the RNF kernel is shown to reduce to the Schrödinger equation (

Appendix J), it is natural to ask:

what is the wave function in this framework?

At a fixed RNF time

t, the slice

is a three-dimensional space on which the chronon field is aligned. The wave function

may still be viewed as a complex scalar field on

, but its components acquire a geometric meaning:

is the density of RNF-compatible microcontinuations through , i.e. the local alignment volume for the next slice.

is the compactified action phase accumulated by RNF histories ending at .

Geometrically, one can think of each point

as carrying two pieces of structure: (i) a local chronon polarization/twist direction in the transverse bundle, and (ii) a

phase angle on the action circle.

Figure 6 represents this as a lattice of points, each decorated by a “twist arrow” (underlying chronon orientation) and a “phase arrow” (action phase). The overall

density and intensity of the arrows in a region encode

, while the phase arrows encode

.

7.5. Measurement as Compatibility Selection and the Born Rule

Measurement devices impose rigid boundary conditions on the RNF, defining discrete compatibility basins

for possible outcomes. Let

denote the RNF-compatible families associated with outcome

i.

Appendix I shows that the reconstruction probability is

which reduces under general regularity assumptions to the Born rule

, the standard quantum prescription [

15]. Probability weights therefore arise from geometric compatibility, not axiomatic postulates.

Collapse corresponds to incompatibility: if , only one basin can be propagated by the RNF.

7.6. Resolution of Standard Quantum Paradoxes

Wave–particle duality and the unified pattern ontology.

In the RNF picture a chronon soliton never ceases to be reconstructed: at each advance the front regenerates a coherent pattern that preserves all compatible twist and curvature constraints. As long as a family of continuations remains mutually compatible, all of its members persist slice by slice; none are eliminated until a macroscopic apparatus forces the RNF dynamics to select a single compatibility basin. In this sense, the standard intuition of wave–particle duality remains valid but gains a deeper foundation: the “particle” is the persistent soliton reconstructed on each slice, while the “wave” is the structured family of all RNF–compatible continuations carrying action phase relations.

The result is a unified ontology: everything that appears as a “wave” or a “particle’’ is, in fact, a chronon pattern undergoing RNF reconstruction. The supposed duality dissolves; only patterns and their compatibility relations remain fundamental.

Collapse and decoherence.

Collapse is geometric incompatibility (

Section 5). Decoherence corresponds to environmental constraints reducing overlap of compatibility sets.

Uncertainty.

Minimal symplectic flux implies that a chronon soliton cannot simultaneously maintain sharply localized twist and perfectly smooth polarization. Localizing the twist within a region of size forces large gradients in the polarization frame, which contribute a curvature energy bounded below by the fixed action quantum . Conversely, reducing polarization gradients to improve smoothness necessarily spreads the twist over a larger region. The product of spatial width and phase–gradient width therefore obeys a geometric lower bound of order , so the familiar uncertainty relation arises not from operator algebra but from the intrinsic twist–smoothness tradeoff enforced by the chronon medium’s finite symplectic flux.

Double-slit and delayed choice.

Interference arises whenever more than one compatibility family survives; which-path constraints remove overlap. Delayed-choice experiments modify the constraints on the slice where reconstruction occurs but do not retroactively change past geometry.

Macroscopic definiteness (Schrödinger’s cat resolved).

The real paradox in Schrödinger’s cat is not that “alive’’ and “dead’’ are incompatible macroscopic states—everyone agrees they are. The issue is that in standard quantum mechanics the composite wavefunction must evolve unitarily until an external measurement occurs. Nothing inside the formalism selects one macroscopic alternative before the box is opened, so the theory predicts an evolving superposition of an alive–cat configuration and a dead–cat configuration with no physical mechanism for when or how one branch becomes real. In the RNF framework, the advancing front must realize a single macroscopic compatibility basin on each slice. Rigid basins such as “alive’’ or “dead’’ are mutually exclusive and only one can be reconstructed. Thus macroscopic definiteness is enforced during RNF alignment, not by external observers.

7.7. Entanglement as a Joint Internal-Bundle Constraint Preserved by RNF Reconstruction

In ChFT, quantum entanglement is not a mysterious nonlocal influence but a

single global constraint in the

internal chronon bundle encoded directly in the aligned pattern on each RNF slice. An entangled configuration is a pattern

whose allowed continuations are restricted by an internal-bundle relation such as

for a spin singlet. This constraint is not carried by spacetime geometry or external soliton structure; rather, it is encoded in the coherent polarization and phase alignment of the vacuum chronons forming an internal-bundle

gauge bridge linking the two systems.

When the RNF advances to , reconstruction proceeds in parallel at all points with no preferred update location. Each point samples the pre-geometric reservoir only from those microstates consistent with the full internal-bundle pattern on . Because the gauge-bridge constraint is represented throughout the vacuum region connecting A and B, RNF reconstruction automatically re-imposes the same internal relation on the next slice. No information or influence needs to be “transmitted” across the emergent metric; the global constraint is simply part of the local compatibility structure used in reconstruction.

Spatial separation does not weaken or modify the constraint because distance, causality, and geometric locality are

products of the same RNF reconstruction process that also enforces the internal-bundle constraint. During each RNF update, every point of

applies the same local compatibility rule in parallel, with no preferred update location: the external positions of

A and

B and the internal-bundle relation linking them are all fixed through this uniform, slice-wide alignment step. This yields the familiar quantum correlations—including those violating Bell inequalities [

10]—without any nonlocal signaling.

7.8. Horizon Alignment, Hawking Suppression, and Stable Micro Black Holes

In semiclassical gravity, Hawking radiation arises from trans-horizon mode mixing of quantum fields near the horizon [

34,

35,

63]. This calculation assumes a fluctuating quantum vacuum with arbitrarily short-wavelength degrees of freedom and a horizon that efficiently mixes modes across an exponentially stretched coordinate transformation.

In the RNF/ChFT framework none of these assumptions hold. The quantum vacuum is a fully aligned chronon configuration rather than a sea of fluctuating field modes; excitations are twist and curvature waves with a built-in ultraviolet cutoff . The horizon therefore acts not as a particle amplifier but as a one-sided geometric boundary: geometric signals cannot propagate outward from inside, but RNF reconstruction still uses the global pre-geometric constraint structure when generating each new slice.

Attempting to extend curvature-alignment waves across the near-horizon layer requires a TCP misalignment cost. As shown in

Appendix L, this cost scales at least as

leading to an exponentially small upper bound on the reconstruction probability,

with

an order-unity stiffness parameter. Multiplying this suppression by the dimensional leakage scale

yields an emission upper bound that is many orders of magnitude smaller than the Hawking rate for any macroscopic horizon.

For astrophysical black holes the ratio is so large that the RNF emission bound is effectively zero, rendering such objects non-radiative in practice. For horizon radii near the alignment scale, , the bound weakens and long-lived compact objects become possible. This provides a natural RNF mechanism for stable micro black holes and chronon-core condensates, with potential implications for dark-matter phenomenology.

Electromagnetic silence of black holes. Both in standard GR and in RNF/ChFT a neutral black hole emits no electromagnetic radiation: classically the horizon hides all internal gauge structure, and in ChFT the interior chronon core is a maximally aligned phase in which all gauge and matter degrees of freedom are frozen. Thus EM emission is identically zero in both pictures; the only possible radiative channel is the gravitational (or curvature–alignment) sector. The key difference is therefore not electromagnetic behaviour but the near total suppression of Hawking-like graviton emission in the RNF framework.

Comparison with ordinary thermal emission. A proton-scale black hole has radius . In standard Hawking theory it would radiate violently, , owing to its enormous temperature .

For intuition, a cold body of the same geometric size placed in a background would emit only .

In RNF/ChFT the emission rate acquires an exponential suppression

; with

this yields

far below even the

scale of ordinary cold-body radiation. Thus a proton-scale RNF black hole would be

colder than any naturally occurring object, with emission suppressed beyond any observational reach.

7.9. Entanglement, Horizons, and Information Preservation in RNF/ChFT

The RNF reconstruction rule provides a simple and structurally clean resolution of the black–hole information problem. In ChFT, evolution does not occur by geometric propagation of fields through an existing spacetime. Instead, the RNF generates each new slice by local, parallel copying of the chronon pattern encoded on , selecting only those microstates compatible with that pattern. No external memory, nonlocal mediator, or additional structure is required: the pattern on the slice itself already embeds all the constraints and correlations needed for reconstruction.

Horizons limit geometric signals, not RNF reconstruction.

A black–hole horizon prevents causal influences in the emergent metric, but it does not impede the RNF. Reconstruction does not rely on communication across the slice; it occurs locally and simultaneously at all points. Because the constraint network—including entanglement relations, holonomy, and topological flux—is already encoded on , the RNF simply reproduces that pattern when building . Interior and exterior constraints are treated on equal footing. Thus, entanglement across a horizon is automatically preserved without any need for geometric transport.

The black–hole interior is continuously rebuilt.

The interior never becomes an isolated or forgotten region. Every RNF step reconstructs the entire chronon pattern, including the interior, using the same local copying rule as everywhere else. The geometric horizon appears only after alignment, as a feature of the emergent metric, and does not affect the underlying pattern that the RNF uses as its input.

Information is never lost.

All correlations—including those that appear nonlocal in the emergent geometry—are preserved because they are encoded in the aligned pattern of each slice and re-imposed by RNF reconstruction. Since Hawking-type emission is exponentially suppressed in ChFT (see Sec.

Appendix L), no thermal flux of mixed states is produced. The evolution remains fully deterministic, slice by slice, and no information is lost. The firewall paradox [

5] arises only if one assumes that entanglement must be transferred geometrically across the horizon, an assumption that ChFT does not require.

Consequences.

This framework avoids all of the standard semiclassical difficulties: there are no firewalls, remnants, nonunitary processes, or exotic entanglement-transfer mechanisms. An entangled pair remains entangled even when one partner crosses the horizon, because the entanglement is a constraint built into the pattern and replicated on each new slice. RNF/ChFT therefore provides a simple, robust, and locality-preserving mechanism through which black holes remain fully information preserving.

In summary: RNF reconstruction preserves the entire constraint network across slices, reconstructing both exterior and interior regions simultaneously. The horizon restricts only geometric propagation, not the RNF itself. As a result, black holes do not lose information in ChFT.

Figure 8.

RNF reconstruction across a black–hole horizon. Left: On slice , the constraint network—including entanglement links and topological flux—spans both interior and exterior regions. Middle: As the RNF advances, reconstruction proceeds through strictly local alignment rules applied simultaneously at all points. No geometric communication or nonlocal mechanism is required. Right: On , the entire pattern is faithfully reconstructed, including all constraints that cross the geometric horizon. Thus information is preserved slice by slice despite geometric causal barriers.

Figure 8.

RNF reconstruction across a black–hole horizon. Left: On slice , the constraint network—including entanglement links and topological flux—spans both interior and exterior regions. Middle: As the RNF advances, reconstruction proceeds through strictly local alignment rules applied simultaneously at all points. No geometric communication or nonlocal mechanism is required. Right: On , the entire pattern is faithfully reconstructed, including all constraints that cross the geometric horizon. Thus information is preserved slice by slice despite geometric causal barriers.

8. Phenomenology: The Electron as the Minimal Chronon Soliton

The compact–action/RNF framework by itself does not specify which excitations of the chronon medium correspond to the known particles. Once the soliton sector of Chronon Field Theory (CFT) is included, a highly constraining identification emerges: the electron is the minimal, topologically complete chronon soliton. This section summarizes why this identification is essentially forced by the theory and how it is consistent with existing experimental bounds.

8.1. Theoretical Motivation

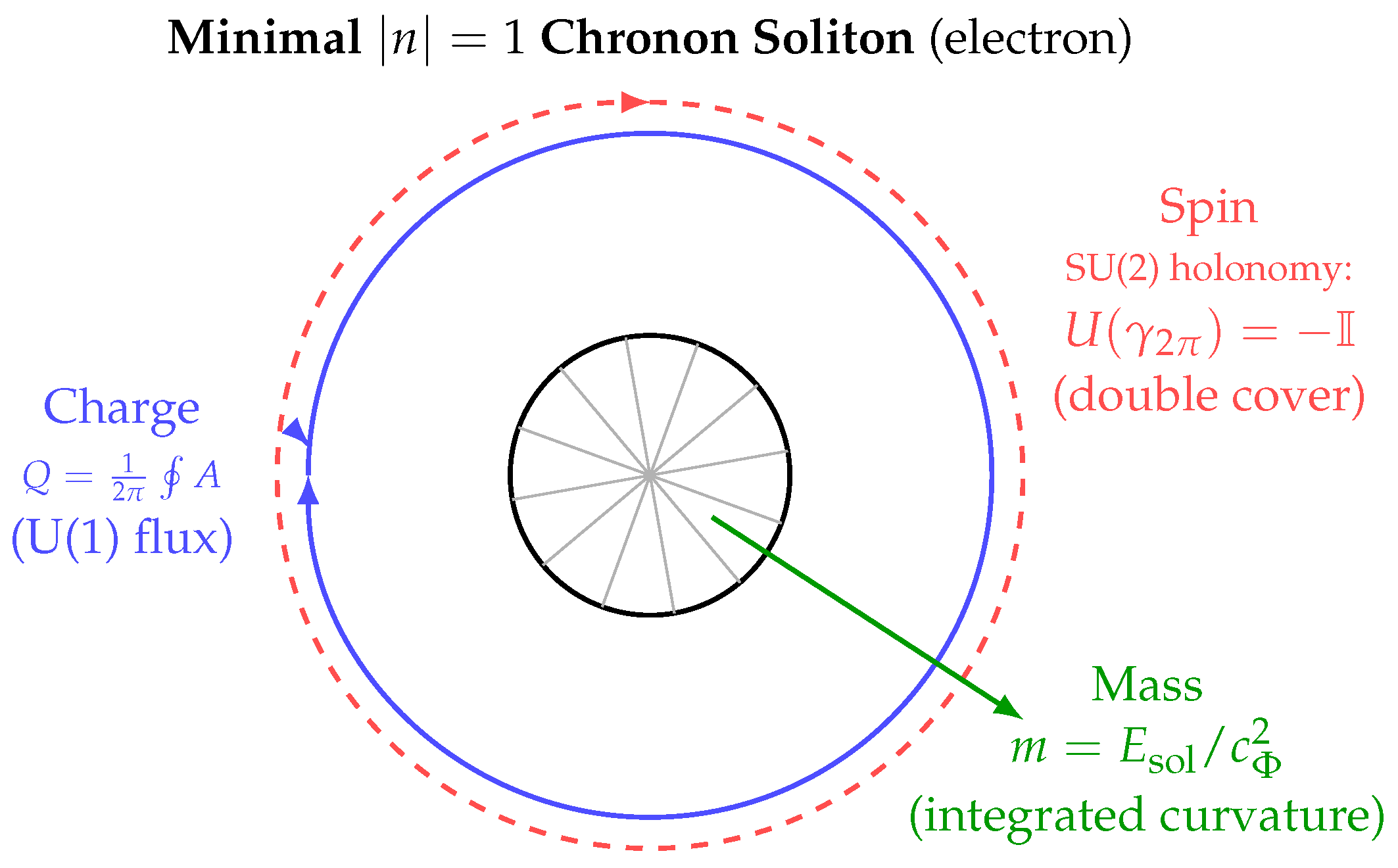

In CFT the chronon vorticity defines a conserved topological flux. Finite–energy configurations are labeled by an integer winding number n, and the quartic TCP terms stabilize localized solitons carrying this flux. The minimal nontrivial configuration has and constitutes a single, topologically complete chronon vortex. Higher- solitons necessarily carry larger emergent charge.

Because the emergent Abelian gauge sector assigns electric charge directly to the winding number, a configuration with n units of flux carries electric charge n in electromagnetic units. Thus a particle with unit electric charge must correspond to the minimal soliton; composites would carry or require an internal pair of opposite-charge solitons.

Spin supplies an independent constraint. The chronon polarization bundle has a nontrivial double-cover structure, so that a rotation acts as the nontrivial element of the cover. A single vortex coupled to this bundle acquires spin in the emergent low-energy description. Multisoliton composites would generically yield higher or mixed spin representations and could not robustly produce an exactly -spin pointlike excitation with no multiplet structure.

Thus:

minimal topological flux (),

unit electric charge,

and the double-cover spin structure,

collectively force the identification of the electron with the single minimal chronon soliton. The soliton core radius is naturally of order the chronon scale and therefore Planck-like, consistent with the electron’s apparent pointlikeness at all accessible energies.

8.2. Consistency with Electron Size and Compositeness Bounds

A soliton solution sounds “extended,” yet high-energy scattering shows the electron to be pointlike down to extremely short distances. In the chronon picture this is explained by the hierarchy

where

is the soliton core,

the shortest experimentally probed distance in scattering, and

the Compton wavelength.

Current collider bounds on electron compositeness [

4,

49] require any internal structure to lie above the multi-TeV scale, consistent with the chronon prediction that

is many orders of magnitude larger.

In addition:

Thus all current “pointlike electron’’ data constrain the chronon scale but remain fully compatible with the minimal-soliton identification.

8.3. Electron Quantum Numbers as Soliton Invariants

In ChFT the electron corresponds to the minimal finite-energy soliton carrying one unit of the fundamental symplectic flux. Its observed quantum numbers arise as geometric invariants:

Electric charge.

The Abelian polarization connection yields a gauge potential

, and the electric charge is

The minimal soliton corresponds to .

Spin.

Spin arises from the holonomy of the

polarization frame around a loop linking the core:

Thus the soliton transforms as a doublet and carries .

Mass.

As explained in

Section 2.5, the soliton mass is the rest energy of the static

chronon configuration. For a stationary solution

the TCP energy functional reduces to the curvature–alignment integral

which contains the quadratic (alignment) and quartic (stability) curvature invariants of the chronon field. The second term is the Skyrme-like stabilizer required by Derrick scaling [

23].

The electron mass is then defined by the usual rest–energy relation

Because

depends only on the stiffness parameters

and the fundamental alignment length

, matching the observed value of

fixes a

single dimensionful combination of these parameters—equivalently, the effective curvature scale of the soliton core. Thus the electron’s mass, charge, and spin emerge together as geometric invariants of the

soliton, endowing it with its operational role as the metrological rod and clock that defines the emergent Lorentz metric on each RNF slice. A schematic illustration is shown in

Figure 9.

8.4. Existing Experimental Constraints

Three empirical domains already constrain the minimal-soliton picture:

Scattering and compositeness.

LEP and subsequent scattering experiments [

4,

49] place strong bounds on deviations of the electron form factor from unity, requiring any structure to lie well above TeV scales, consistent with

.

Anomalous magnetic moment.

The precision of the electron

[

6] implies that any soliton-induced correction must be minminuscule. This is naturally satisfied since chronon corrections scale as

with

.

Absence of excited electrons.

Collider limits on excited leptons [

8,

21] place strong constraints on internal substructure. In ChFT this is expected: the next stable excitations of the

sector correspond to much heavier solitons, plausibly related to the muon and tau rather than to “electron excitations.”

8.5. Possible Future Tests

Although direct access to the chronon scale is infeasible, the minimal-soliton identification makes several robust predictions:

Exact pointlikeness at accessible energies. A soliton radius – implies no deviations from pointlike behaviour for . Any observed deviation at lower energies would falsify the model.

-

Cross-sector consistency. The same chronon stiffness parameters

determine

Future precision comparisons between QED running and QCD spectroscopy therefore serve as cross-sector tests of the chronon medium.

Ultra-precision spectroscopy. Corrections to atomic energy levels scale as

far below foreseeable sensitivities, ensuring consistency with current atomic physics.

Thus the key phenomenological signal is not a directly measurable electron radius, but the uniqueness of the electron as the minimal chronon soliton. Its conserved flux, intrinsic twist, and Planck-scale core tie together particle quantum numbers, quantum phase structure, and emergent spacetime geometry within a single medium.

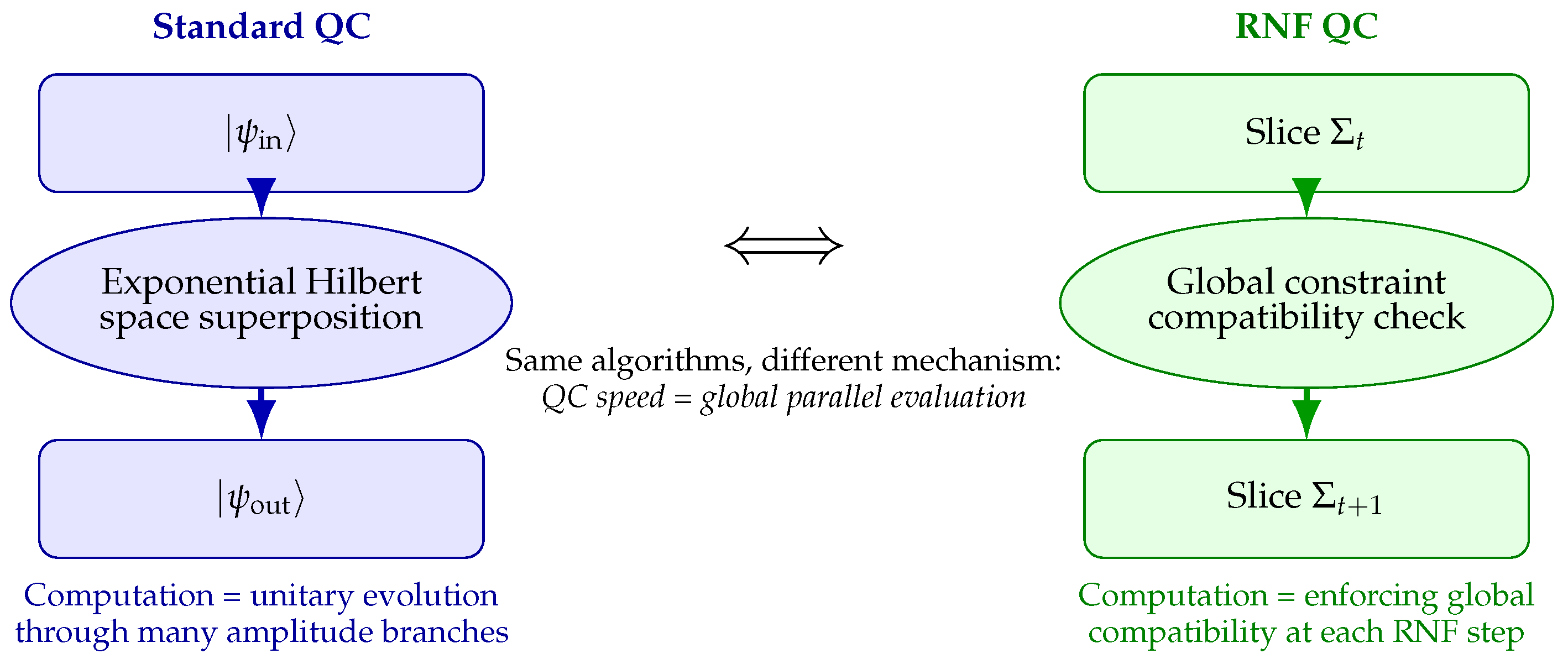

Figure 10.

Comparison of standard quantum computation (QC) with the RNF view. Standard QC interprets speedup as evolution through an exponentially large superposition. In contrast, RNF QC interprets speedup as a single act of global constraint enforcement in 4D at each reconstruction step.

Figure 10.

Comparison of standard quantum computation (QC) with the RNF view. Standard QC interprets speedup as evolution through an exponentially large superposition. In contrast, RNF QC interprets speedup as a single act of global constraint enforcement in 4D at each reconstruction step.

9. Historical Context and Comparison with Standard Approaches

Since the birth of quantum theory, the phase factor

has been accepted as a primitive rule rather than as the consequence of a deeper structure. Planck’s quantum of action

h [

54], Bohr’s quantized orbits [

14], de Broglie’s matter waves [

22], and Feynman’s path integral formulation [

28,

29] all rely on this phase. Yet none answered the structural question:

why should nature assign probabilities through complex action–dependent phases?

The compact–action framework developed here provides such an answer. Once the action is intrinsically periodic—taking values on a compact domain rather than on —interference and phase addition arise as geometric necessities rather than postulates. Chronon Field Theory supplies the microscopic origin of this periodicity: the chronon medium carries a finite, topologically protected unit of symplectic twist, which endows the action with its compact structure. In this view, Planck’s constant reflects a geometric property of the underlying field, and the familiar quantum phase rules follow directly from the topology of the chronon medium rather than from ad hoc quantization assumptions.

9.1. Relation to Standard Quantum Mechanics

Standard quantum mechanics is structured around four elements: (i) complex state vectors, (ii) phase factors , (iii) unitary evolution, (iv) Born probabilities.

In the compact–action/RNF framework these arise from the geometry:

The path integral emerges from RNF summation over modular-equivalent families (

Section 7).

The Schrödinger equation appears in the long-wavelength, slowly-varying limit of RNF locality (

Appendix J).

The Born rule is recovered as a compatibility-basin measure during RNF alignment (

Appendix I).

Thus standard quantum mechanics is not assumed but recovered as the effective description of compact action and RNF propagation.

9.2. Relation to Quantum Field Theory

Quantum field theory (QFT) quantizes classical fields on a fixed spacetime background and treats ℏ as externally supplied. In ChFT:

arises from quantized symplectic flux;

the spacetime metric is generated by RNF alignment of ;

gauge interactions originate from holonomy of the polarization bundle.

In the appropriate geometric limit—large alignment scale and small curvature—aligned chronon configurations reproduce Einstein–Yang–Mills–type dynamics [

42]. QFT is therefore obtained as an effective field theory whose fundamental parameters (action quantum, metric structure, and gauge couplings) have geometric origins in the chronon medium.

9.3. Why This Is Not an “Interpretation” of Quantum Mechanics

Interpretations of quantum mechanics retain the standard formalism and reinterpret its meaning. The compact–action/RNF/ChFT framework modifies the underlying structure:

the phase is derived from compact geometry;

interference arises from finite symplectic flux, not from wave duality;

measurement corresponds to RNF compatibility selection, not a postulated collapse;

spacetime, gauge fields, and matter solitons emerge from a common chronon dynamics.

The framework is therefore a geometric extension of quantum mechanics rather than a reinterpretation of its existing axioms.

9.4. Summary

The compact–action/RNF framework recovers all experimentally established predictions of quantum mechanics and quantum field theory while providing structural elements absent from the standard formalisms: a geometric origin of ℏ, an explanation for complex phases, a physical mechanism for measurement, and a unified emergence of spacetime, matter, and gauge structure from a single causal medium. It fits within the established theoretical landscape while completing elements that previously functioned only as axioms.

10. Conclusions

We have shown that a finite quantum of action , arising from the quantized symplectic flux of the chronon field, compactifies the action manifold from to and thereby enforces the phase structure underlying all quantum interference. Within this compact–action geometry, the Real–Now–Front (RNF) provides a local reconstruction rule that propagates only chronon-pattern trajectories lying in the same modular action class, recovering the structural forms of the Feynman path integral, the Schrödinger equation, and the Born rule. Interference, measurement, and entanglement arise from compatibility constraints during RNF alignment rather than from additional axioms.

A central feature is that each RNF slice represents the actual three-dimensional present—the advancing boundary at which new spacetime, matter patterns, and causal relations are brought into existence. This provides a concrete mechanism for Becoming, avoids the static block-universe picture, and supplies a physical selection rule ensuring macroscopic definiteness without invoking external observers. Because all observable excitations are emergent patterns on the RNF slice, the preferred direction of the chronon medium remains operationally concealed, yielding effective Lorentz invariance at all accessible energies.

In this sense, the compact–action/RNF framework functions not as an interpretation of quantum mechanics but as a geometric completion of it: Planck’s constant, quantum phases, causal structure, measurement, and the emergence of classical spacetime follow from the same underlying principles of symplectic quantization and RNF compatibility. The same reconstruction principle also ensures that information is preserved across horizons, eliminating the black–hole information paradox without additional hypotheses.

Future work will develop quantitative predictions of RNF quantum dynamics at high curvature and short distances, refine the soliton description of matter—including the minimal-soliton identification of the electron—and explore phenomenological consequences in mesoscopic interferometry, horizon physics, and possible chronon-scale effects.

Falsifiability. Although many chronon–scale effects lie beyond present technology, the framework makes several sharp and experimentally meaningful predictions. (1) ChFT implies an exponential suppression of Hawking-like emission; a clear detection of the standard Hawking spectrum or rapid evaporation of sub-stellar black holes would contradict this mechanism. (2) If collider or scattering experiments establish an electron compositeness radius much larger than the predicted chronon-scale value , the minimal-soliton identification would be ruled out. (3) If Lorentz invariance were found to fail at scales far above the chronon length , this would contradict the Co-moving Concealment Principle, which predicts effective Lorentz symmetry on all RNF slices. (4) If gravitational degrees of freedom were ever shown to become entangled, this would falsify the RNF prediction that only internal chronon-bundle modes can support quantum entanglement.

Any one of these observations would falsify core components of the chronon framework. Together they outline clear and testable criteria for assessing the viability of the compact–action/RNF program.

Author Contributions

Bin Li is the sole author

Funding

This research received no external funding

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ChFT |

Chronon Field Theory |

| TCP |

Temporal Coherence Principle |

| CCP |

Co-moving Concealment Principle |

| RNF |

Real Now Front |

Appendix A. TCP Mathematical Framework

This appendix summarizes the minimal mathematical structures of the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP) needed for the compact–action geometry, the emergence of , and the RNF-based reconstruction rules used in the main text. We focus on configuration space, compatibility sets, and the symplectic twist structure; detailed topology, soliton stability, and RNF dynamics appear in later appendices.

Appendix A.1. Configuration Space of Chronon Fields

Let

be a smooth four-dimensional manifold. A

chronon field is a smooth unit timelike covector

and the configuration space is

A chronon pattern on is a map , whose spatial gradients encode twist, alignment, and curvature. A pattern is called aligned when is small in an appropriate norm, enabling the construction of an emergent metric.

Appendix A.2. Compatibility Sets

To each pattern

the TCP dynamics assigns a

compatibility set

Two patterns are

compatible when

This structural notion underlies the distinctions between interference (overlapping compatibility), decoherence (environmental elimination of overlap), measurement (selection of a single surviving class), and entanglement (joint constraints). No Hilbert-space or probabilistic assumptions are needed at this stage.

Appendix A.3. Symplectic Twist and the Emergence of ℏgeom

The TCP dynamics includes the universal antisymmetric two-form

whose flux around closed loops defines the

symplectic twist

Quantization follows from three structural features:

- (i)

finite-energy configurations compactify spatial infinity, placing chronon fields into homotopy classes labeled by n;

- (ii)

the twist bundle associated with has compact topology;

- (iii)

quartic TCP terms prevent continuous unwinding of twist.

Thus is the minimal symplectic increment of , determined by the stabilized core structure of TCP solitons. Its later appearance in compact action and RNF propagation requires no Hilbert space: it follows from the topology and stabilization properties of .