1. Introduction

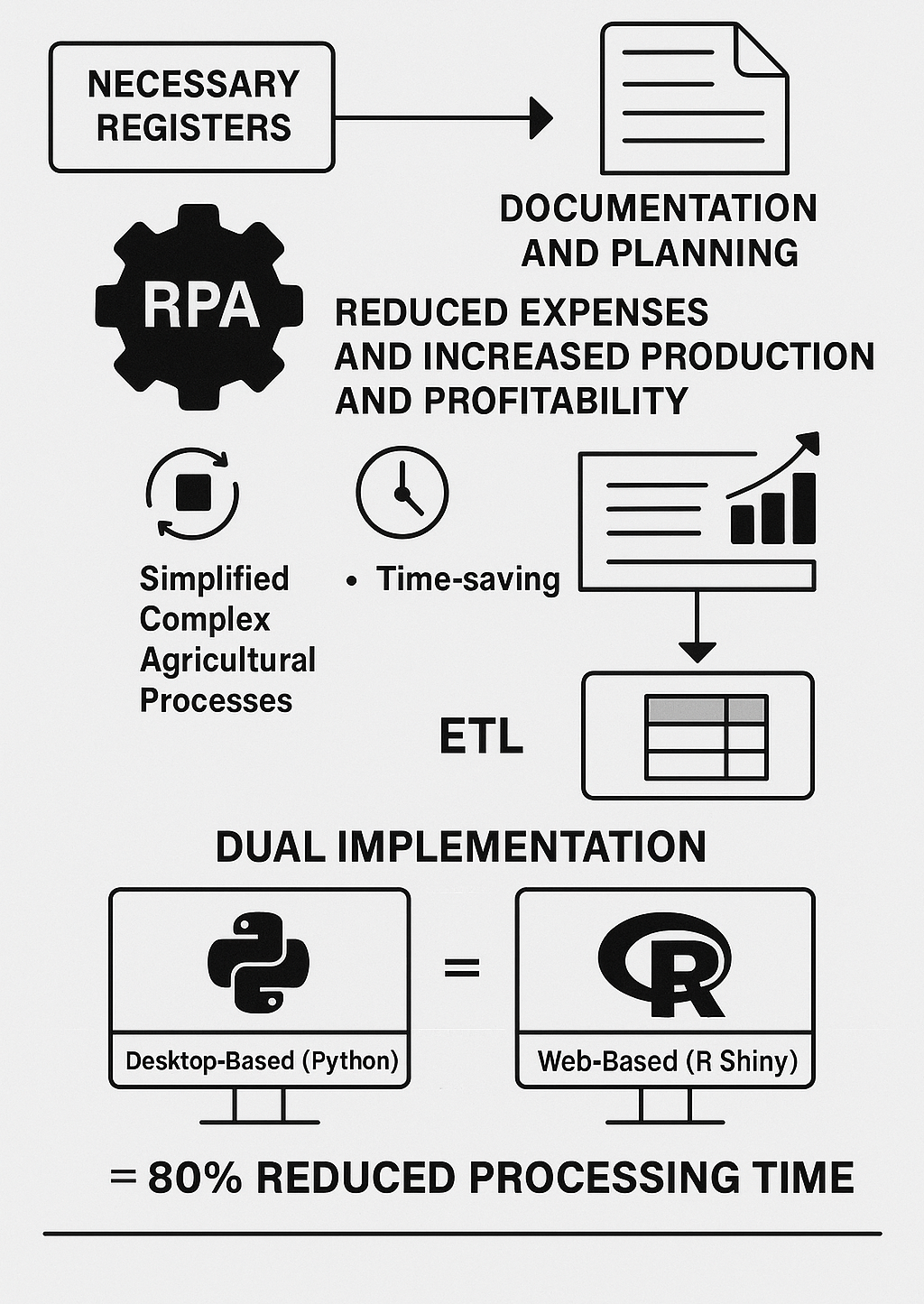

Process Automation (RPA) is activity through which certain repetitive or routine business processes can be performed by "software robots" that algorithmically perform certain tasks [

1,

2,

3,

4] which is based on a robotic program/software with the role of imitating or performing the steps taken by a human user, in an application or in a program. RPA provides the technology that allows us to configure a "robot" to mimic human actions in digital business processes, RPA robots use the user interface to retrieve, enter data and manipulate applications just like humans [

5,

6].

RPA does not require programming skills, but it is essential to know and understand the technology concepts at a high level, which can sometimes be complex or confusing due to the large number of acronyms used in the field and the multitude of algorithms [

7]. Artificial Intelligence AI refers to the processes and functionalities for modeling and analyzing data, although this inspires images of high-performance, human-looking robots taking over the world, AI is not intended to replace humans, its purpose is to significantly enhance functionality and human contributions, in our case for agricultural business processes [

8].

Recent European initiatives, including the Farm to Fork Strategy [

19], emphasize digital transition as a key enabler of sustainability. The proposed automation system supports this transition by integrating data-driven compliance management into daily agricultural workflows.

1.1. Agricultural Holdings in Romania

The agricultural holding is primarily defined by Law no. 37/2015 [

9], which regulates the classification of farms and agricultural holdings based on economic size and type of agricultural activities. This law provides an updated framework that includes family-type holdings, commercial farms, and small farms. According to Law no. 37/2015, the definition of an agricultural holding in Romania is as follows: ”a form of organization consisting of all units used for agricultural activities and managed by a farmer, located within the territory of the same Member State of the European Union”.

Under this law, an agricultural holding is an economic unit that can take various ownership forms and sizes, ranging from small family farms to large commercial operations. An important element introduced by Law no. 37/2015 is the implementation of more detailed criteria for classifying agricultural holdings, enabling more effective monitoring and support for their development. The classification is based on economic size, measured in Economic Size Units (ESU), and the type of activities carried out.

In addition to Law no. 37/2015, European legislation plays a key role in defining and regulating agricultural holdings, especially through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). CAP has been adapted to support the development of agricultural holdings in Romania, particularly through measures aimed at reducing land fragmentation, which is a significant issue for Romanian farmers. Furthermore, EU subsidies are essential in supporting small-scale farmers and modernizing agricultural holdings.

Alongside Law no. 37/2015, Land Fund Law no. 18/1991 [

10] remains a cornerstone regulation governing property rights over agricultural land. This law, enacted shortly after the political changes of 1989, defines ownership rights and conditions for land transfer. Additionally, Law no. 36/1991 [

11] regulates associative forms of agricultural production, encouraging cooperation among farmers to create more competitive holdings and improve access to resources and markets. This law is crucial for the development of modern agricultural cooperatives and better integration into value chains.

At the European Union level, the term "agricultural holding" is used to classify farms based on size, income, and activity type. EU classification criteria include: Physical size (in hectares), Economic size (e.g., European Size Unit - ESU, Standard Gross Margin - SGM, and more recently, Standard Output - SO). The Standard Output (SO) of an agricultural product (crop or livestock) represents: "the average monetary value of the agricultural output at farm-gate price, in euro per hectare or per head of livestock".

These classifications help determine eligibility for CAP subsidies and facilitate modernization and efficiency in farm management. A study by Popescu in [

12] examined the evolution of agricultural holdings in the EU, using economic indicators such as: farm size; income per Annual Work Unit (AWU); distribution by size classes. The study highlights that Romania has a high number of small holdings, many of which fall below the economic viability threshold, thus stressing the need for consolidation and modernization of farms.

According to Sterie & Dumitru [

13], Law no. 37/2015 introduced clear criteria for the classification of Romanian agricultural holdings, considering economic size and types of activities. Classification based on economic size enables farmers to access CAP subsidies and other support mechanisms, making it a key component in rural development strategies. Studies by Eurostat and FADN at the European level have monitored the structure of agricultural holdings and assessed the impact of financial support measures through CAP. These studies emphasize: Improving the economic efficiency of small farms, Promoting modernization and investment. In Romania, agricultural holdings have received significant support through the National Rural Development Program (NRDP), which facilitates infrastructure modernization, mechanization, digitalization of farms.

Such initiatives are crucial for enhancing competitiveness and integrating Romanian agriculture into the EU market. In addition to mechanization, the use of digital technologies (e.g., precision agriculture) is gaining ground, enabling farmers to optimize resources and reduce production costs. These technologies are promoted through both national and European technical and financial support and are essential for increasing the sustainability of Romanian farms. The 2020 General Agricultural Census revealed a significant decline in the number of agricultural holdings in Romania, particularly small ones. Preliminary data shows that the number of holdings decreased by 25.2% compared to 2010, reaching 2,887,000 holdings in 2020. Additionally, the utilized agricultural area declined by 4.1%, down to 12.8 million hectares.

The census also revealed that only one-third of holdings receive subsidies, highlighting the need for more effective policies to support small farmers. The data points to both land consolidation and the disappearance of small farms, many of which lack access to the financial resources needed for development and modernization.

1.2. Agricultural Practices and Registers in Romania

An agricultural holding in Romania is defined as the unit where agricultural activities are carried out under the management of a natural or legal person, regardless of the legal form of ownership or the production purpose. According to Law no. 37/2015, agricultural holdings are classified into several categories based on utilized agricultural area and economic size [

9]. This legislative framework aligns with the European Union’s classification principles for structural agricultural surveys.

From a conceptual standpoint, the Romanian agricultural holding has evolved through a series of agrarian reforms, structural adjustments, and EU integration processes. The work of Glogovetan [

14] outlines these historical transitions, indicating a movement from collectivized forms to privatized, small, and fragmented holdings, which remain characteristic of Romanian agriculture today.

The Farm Register serves as a core component of Romania’s agricultural data infrastructure. It consolidates information about farm structures, land use, livestock, and machinery. This register was significantly updated through the 2010 General Agricultural Census, conducted in accordance with Eurostat methodologies [

15]. The Statistical Farm Register is maintained by the National Institute of Statistics (NIS), yet the [

16] noted inconsistencies and data quality issues due to non-uniform record-keeping practices across regions and delays in data updates.

According to the national requirements for farm management, phytosanitary treatments (plant protection treatments) must be recorded in the farm register. This includes the type of chemical products used, the quantity, the crop targeted, and the date of application [

17]. These practices are regulated under agro-environmental compliance and monitored through inspections from the National Phytosanitary Authority (NPA), ensuring traceability and food safety. Such entries in the farm register serve as legal evidence for Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) and are prerequisites for access to subsidies under EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) measures.

A fertilization plan is a key agricultural document that outlines the nutrient management strategy for crop production, tailored to soil characteristics, crop needs, and environmental considerations. In Romania, fertilization plans are mandatory under both national legislation and EU conditionality for nitrate-sensitive zones [

17]. These plans must include calculations based on soil analysis, nitrogen balance, and crop requirements.

The European Commission Decision 2019/1205 further defines a fertilization plan as the prior planning of nutrient input and expected crop uptake, especially important in the context of nitrate directive compliance [

19].

Farmers are legally obligated to record fertilization activities in their farm registers, detailing the quantities, types, and timing of fertilizer applications. This requirement aims to ensure efficient nutrient use and to reduce the environmental impact of excessive fertilization [

17]. These records are also used in auditing compliance with agro-environmental standards and serve as reference points for land parcel evaluations.

2. Materials and Methods

The primary input material for the automation process described in the study is the Single Payment Application Form SPAF (Cerere Unică de Plată) submitted by Romanian farmers through the APIA IPA-Online platform. Specifically, the case study utilized the 2022 application form of a farmer.

This official agricultural subsidy form includes detailed, structured declarations of agricultural land use and livestock inventory, required annually for subsidy eligibility. The document spans multiple sections and pages, incorporating both textual metadata and tabular data, and serves as the core dataset for the Robotic Process Automation (RPA) system.

Key data elements from the form include:

Farmer Identification Data: Personal identification (CNP), contact information, and bank account details for subsidy transfers.

-

Agricultural Holdings:

- -

Land Declarations: Parcel-specific information including location identifiers (county, locality, SIRUTA code), block and parcel numbers, land use category (e.g., TA – arable land, PP – permanent pasture), surface area (in hectares), altitude zone, and the specific crop cultivated (e.g., corn, lucerne, wheat).

- -

Crop Management: Crop rotation and greening measures, including declarations for successive planting and ecological focus areas (ZIE), with associated parcel-level crop codes and surface areas.

-

Livestock Records:

Inventory of animals classified by species and age group (e.g., bovines over two years, sheep, goats), along with national animal registry IDs (RNE identifiers).

-

Support Measures and Schemes, the farmer opted for multiple EU and national aid schemes, including:

- -

Single Area Payment Scheme (SAPS)

- -

Redistributive Payment

- -

Greening Payment

- -

Coupled Support for lucerne cultivation

- -

Compensatory payments for mountain or constrained areas (Measure 13)

This comprehensive set of structured data provides the foundation for automated extraction, transformation, and analysis workflows. The data includes both numerical fields (e.g., parcel areas, animal counts) and textual labels (e.g., crop types, land use codes), which are parsed using the Python-based ETL system.

Importantly, the document contains several pages of formatted tables with diverse layouts, some of which may originate as scanned images—necessitating the use of Optical Character Recognition (OCR) for reliable text extraction. This variability underscores the value of a robust and flexible data pipeline capable of handling inconsistent and non-uniform document structures.

In essence, the application form functions as both a legal declaration and a dataset, enabling the automation system to simulate administrative workflows, calculate totals for fertilization planning, and support compliance documentation for environmental and agricultural policies.

The automation solution was implemented using two complementary software modules: a desktop application developed in Python and a browser-based interface built with the Shiny framework.

2.1. Python Desktop Application

The desktop application, developed using Python, integrates a graphical interface (via tkinter) with data processing logic aimed at transforming agricultural registration documents. The primary workflow involves uploading a PDF file of the "Cerere Unică de Plată" from the APIA system, which is then processed through the following steps:

Table Extraction: The pdfplumber library extracts structured or semi-structured tables from the PDF, saving them as Excel worksheets using pandas and openpyxl.

Row Parsing: The tool applies regular expressions to identify key data elements such as parcel identifiers, land use categories (e.g., TA, PP), culture types, and declared surface areas.

Data Aggregation: Parsed rows are aggregated by culture type and land category to compute total declared surface areas.

Output Generation: The application generates two main Excel files: output_tables.xlsx raw extracted tables, one worksheet per page; Plan_de_fertilizare.xlsx summarized area calculations per crop and per category, along with a metadata sheet.

3. Results

The purpose of the application is a partial automation of the process for preparing agricultural holding record documents. By automating the preparation of the farm register, treatment records, and the fertilization plan, we can significantly reduce the time required and increase the efficiency of the personnel responsible for these documents. Farmers are required to record the application of phytosanitary treatments in the Register for Plant Protection Product Treatments (PPPT). They must also keep up-to-date records, retain them for a period of 3 years, and present them for inspection. These documents should include information on the farm area, a simplified fertilization plan, and livestock inventory by species and animal category.

The Python application described is designed to assist in processing agricultural data submitted through Romania’s Single Payment Application System (SPAS), commonly known as "Cererea Unică de Plată", which farmers submit annually to APIA.

The UML diagram,

Figure 1 illustrates the modular architecture of the lumber5.py application, highlighting three main components: Helpers (for utility functions), ETLFunctions (responsible for data extraction, transformation, and loading), and GUIApp (the graphical user interface).

The relationships show that the Graphical User Interface (GUI) interacts with the ETL module to execute the automation workflow, while the Extract Transpose and Load (ETL) module, in turn, relies on the helper functions for data normalization and conversion.

These application forms are typically generated in PDF format by the APIA platform,

Figure 2. In order to allow for easier manipulation and analysis, these PDF files must first be converted into MS Excel

TM format (.xlsx). When a PDF document contains scanned pages—such as printed tables or handwritten forms—it typically cannot be read as structured data using traditional tools. These application forms are typically generated in PDF format by the APIA platform,

Figure 2. In order to allow for easier manipulation and analysis, these PDF files must first be converted into MS Excel

TM format (.xlsx). When a PDF document contains scanned pages—such as printed tables or handwritten forms—it typically cannot be read as structured data using traditional tools.

In such cases, Optical Character Recognition (OCR) is used to interpret and extract the text from the image-based content. The process begins with converting each page of the PDF into a high-resolution image using the pdf2image Python library. These images represent the visual content of the document and serve as input for the OCR engine.

Next, each image is passed through pytesseract, a Python wrapper for Google’s Tesseract OCR engine, which scans the image for characters and returns the recognized text. For pages that contain tables, the output might not be perfectly structured but can often be cleaned and reshaped to resemble tabular data using Python [

18]. Each block of extracted text is then parsed into rows and columns, assembled into a Pandas DataFrame, and saved into an MS Excel

TM file. Each page is saved as a separate sheet within the Excel workbook. This automated approach significantly reduces the manual effort required to extract structured information from printed or scanned agricultural documents, like APIA forms.

Each page from the original PDF becomes a separate worksheet in the resulting MS Excel TM workbook. Once converted, the Excel document is processed using a Python application that combines several modules and instructions for data extraction, transformation, and analysis. The core logic of the program is built with the help of the tkinter module, which creates a graphical user interface (GUI), and the openpyxl and pandas libraries, which are used for reading and modifying Excel files and dataframes. Upon launching the application, a window is created using the tkinter.Tk() function. This window includes labeled text boxes and buttons, which guide the user in entering the relevant year for the payment application and in selecting the corresponding Excel file from their local system.

The user begins by inputting the year of the application into a dedicated text box. When the ”Browse” button is pressed, the application uses the filedialog.askopenfilename() method to open a file dialog, allowing the user to locate and select the Excel file that corresponds to the form. Once selected, the application scans all worksheets in the file to identify those that contain specific headers indicating parcel data or information about animal ownership or the applicant’s address. This identification is done by searching for predefined keywords within the cells, and storing the coordinates of relevant cells into global variables.

Following the initial conversion, the application uses pandas and openpyxl to extract, clean, and organize data into separate worksheets corresponding to land parcels, crop types, surface areas, and livestock declarations. Each page from the original PDF is parsed and saved as a separate worksheet named sequentially (e.g., “Table1”, “Table2”, etc.) in the resulting Excel workbook. These sheets contain raw or semi-structured tables extracted via OCR. The application then parses these tables to derive structured values, including computed aggregates such as total surface areas per crop or land use category. This enables quick visualization and inspection by farm managers or consultants.

The application systematically searches through the identified worksheets, extracting and storing relevant values into organized columns. For each entry, it also ensures that numeric values are properly formatted by replacing inconsistent decimal separators and applying conversion logic to produce standardized numerical values, crucial for enabling accurate mathematical operations later in the analysis.

For larger forms spanning multiple sheets, the application continues to analyze subsequent pages by identifying the same keywords and structure in other worksheets, then transferring and formatting the additional data similarly. During this process, lists of all land use categories and culture types encountered are dynamically built, allowing for further aggregation and summary.

The application also includes a calculation function that computes the total area for each culture type and land use category found in the data. For each entry in the list of categories or crops, the program constructs an MS Excel formula that sums the areas of all parcels associated with that category. These formulas are then inserted into the Excel workbook, allowing users to view total surface areas directly within the spreadsheet. This automated generation of formulas simplifies the process of summarizing data for reporting or further analysis.

The user interface is completed with several functional buttons created using the tkinter.Button() class. Each button is linked to a specific function: browsing for files, exporting data, performing calculations, or exiting the application. The layout is arranged using the pack() method, and the interface remains interactive through an infinite loop initiated by mainloop(), which keeps the window active and responsive to user input, see the .

Overall, the application provides an intuitive and efficient solution for transforming and analyzing complex agricultural data submissions, enabling users to extract, clean, organize, and summarize key information from Excel documents originally derived from APIA’s PDF forms.

The UML class diagram of the RPA Shiny application

Figure 3 illustrates a modular architecture that mirrors the ETL logic of the Python-based automation but implemented as a web application. The UI module defines the interface for file uploads, user controls, and visualization panels, while the Server module manages the event-driven logic and data flow between components. The ETLModule performs backend data extraction, cleaning, and aggregation from APIA PDFs, providing structured datasets to the Visualization Module, which generates dynamic tables and plots. RPA_ShinyApp class integrates all modules, launching the complete application as an interactive, browser-accessible data automation platform for agricultural management.

To further support transparency, replicability, and scalability, a web-based version of the application has been developed using the Shiny framework in Python, available at RPA Shiny Repository,

Figure 4. This version allows for browser-based execution of the pipeline, providing remote accessibility, dynamic data visualization, and potential multi-user capabilities.

3.1. Evaluation

To assess the efficiency and accuracy of the proposed RPA-based data processing system, an extensive performance evaluation was carried out using a dataset of 102 PDF files obtained from the APIA platform, representing a diverse set of agricultural holdings differing in surface area, crop variety, and number of declared parcels. The dataset included both natively digital and scanned forms, the latter requiring Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to convert image-based content into machine-readable text. The testing aimed to quantify improvements in processing speed, accuracy, and data consistency relative to the conventional manual workflow used by consultants and farm administrators.

Each file was processed using three approaches: (1) the manual method, which typically involves opening PDF documents, transcribing tables into Excel, and manually verifying surface totals; (2) the Python desktop RPA application, which automates extraction, transformation, and loading (ETL) using the pdf2image, pytesseract, pandas, and openpyxl libraries; and (3) the R Shiny web application, which replicates the same logic through a browser-based interface, allowing multiple users to process data remotely. The evaluation focused on key indicators such as average processing time per file, OCR text recognition accuracy, error rate in numerical fields, and data completeness.

The results, summarized in

Table 1, show a significant reduction in processing time, from an average of 30 minutes manually to 2 minutes using the Python RPA tool and 3 minutes via the Shiny interface. OCR accuracy was maintained at above 91%, with minor deviations caused by low-resolution scans or inconsistent table layouts. The system also achieved 100% completeness in identifying required data fields such as parcel code, crop type, and total declared area. Compared to manual transcription, the automated pipeline reduced data entry errors by more than 85% and standardized Excel outputs to ensure compatibility with further analytical or reporting processes.

Furthermore, the Shiny version demonstrated a slight performance trade-off in execution time, due to web rendering overhead, but compensated with greater accessibility and usability, particularly for remote users or institutions needing centralized data processing. In large-scale testing, the entire batch of 102 forms was processed within 2 person-hours using the Python script in a parallelized mode, compared to an estimated 51 person-hours for manual completion by experienced operators. These results confirm the scalability and robustness of the automation framework, validating its applicability for broader deployment in agricultural record management systems.

4. Discussion

The development and application of the automation platform described in this study demonstrate the transformative potential of Robotic Process Automation (RPA) in streamlining agricultural administrative tasks. The combination of Python-based libraries and an intuitive graphical interface allowed us to create an end-to-end ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) solution for processing farm declarations, particularly the "Cerere Unică de Plată". Starting from scanned PDF documents (often image-based and non-machine-readable), the use of OCR via `pytesseract` and `pdf2image` facilitated data extraction from unstructured formats. The `pdf2excel.py` module effectively converted these documents into structured Excel worksheets, enabling downstream automation processes.

One of the critical innovations of our system lies in the `tkinter`-based application, which guides the user through importing, validating, and transforming agricultural data. This tool not only identifies key tables in the Excel structure based on keywords such as "Cod SIRUTA", "Nr. Parcelă", or "Categorie de folosintă", but also processes multi-sheet documents and dynamically builds lists of encountered culture types and land use categories. These lists are then used to calculate aggregate values using `openpyxl`, which programmatically inserts formulas in Excel cells. This capability bridges the gap between scanned submissions and actionable data for compliance and planning.

The automation of these procedures greatly reduces the time and effort traditionally required by farmers and consultants to prepare treatment records and fertilization plans. The application respects national and European regulatory requirements, including nitrate directive compliance and environmental safety protocols, by ensuring that the relevant parameters (e.g., surface area, fertilization types) are accurately documented and available for audit.

Beyond technical efficiency, the system ensures traceability, transparency, and a high degree of data quality, especially relevant in subsidy applications and agricultural inspections. In the context of Romania’s digital transformation in agriculture, this solution provides an inclusive approach, particularly for small and medium-sized holdings that often lack access to professional digital platforms.

In summary, this approach demonstrates the practical feasibility of low-code RPA in agriculture and offers a replicable framework for similar initiatives in public administration or environmental compliance monitoring. The flexibility of Python, combined with the accessibility of open-source libraries and a user-friendly interface, supports the broader agenda of digital inclusion and sustainable farm management.

5. Conclusions

Our goal was automation of the process of editing of the farm register, the treatments and the fertilization plan by the farmers, which are necessary for the documentation and planning of plant protection works and the proof of prevention of nitrate pollution from agricultural sources. Finally, we developed program that generate a separate Sheet in MS ExcelTM*.xlsx format that contain the necessary data to continue automating of document generating process.

The automation of the farm register, the phytosanitary treatments, and the fertilization plan represents not only a technical innovation but also a strategic transformation in agricultural record-keeping and compliance in Romania. By leveraging Robotic Process Automation (RPA) and modern data processing techniques such as ETL (Extract, Transform, Load), the developed application enables farmers and administrative personnel to streamline previously time-consuming and error-prone manual tasks. This transition contributes directly to increased operational efficiency, transparency, and regulatory compliance.

The implemented solution exemplifies the real-world application of digital agriculture—a concept increasingly promoted at the European level through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and related modernization strategies. The use of OCR-based text extraction from scanned documents addresses one of the major bottlenecks in rural administration: the limited availability of structured, machine-readable data. By converting visual content into Excel spreadsheets that can be parsed and analyzed, the application bridges the gap between traditional paper-based workflows and digital data ecosystems.

Moreover, the system’s architecture, based on Python libraries such as pandas, openpyxl, pdf2image, and pytesseract, ensures flexibility and scalability. It allows for future enhancements, such as integrating a centralized database, expanding to additional agricultural document types (e.g., livestock health records), or incorporating AI-based anomaly detection for subsidy fraud prevention or data validation.

Beyond the technical merits, this application aligns with broader sustainability and environmental goals. Accurate and timely recording of fertilization activities and treatment applications is essential for minimizing nitrate pollution, ensuring food safety, and complying with EU environmental directives. As more Romanian farmers and cooperatives are expected to digitalize their practices in the coming years, such solutions can play a crucial role in easing the transition and ensuring inclusivity—particularly for small and medium-sized holdings that lack access to expensive farm management software.

The results of the current implementation indicate that automation significantly reduces the time required for document preparation, minimizes human errors, and provides a structured output that can be readily used for audits, subsidy applications, or internal planning. These benefits, coupled with the ease of use provided by a graphical interface, support wider adoption among users with limited IT skills.

Future development of the platform could include a web-based dashboard, automated validation rules for anomalies in crop area declarations, integration with national agricultural databases (e.g., APIA or INS), and multilingual support for broader accessibility. Furthermore, deploying the application within a cloud infrastructure could enable remote access and data sharing among stakeholders, thus contributing to the development of smart agricultural ecosystems.

In conclusion, the proposed RPA-based application illustrates a successful example of digital transformation in agriculture, demonstrating how low-code/no-code tools and open-source libraries can empower even resource-constrained organizations and farmers. The solution stands as a practical and replicable model for other sectors within agri-administration, promoting data-driven decision-making, environmental responsibility, and agricultural innovation.

6. Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the RPAlumber repository, at the following address:

https://github.com/calinadriancomes/RPAlumber.

This includes the input source file (1.pdf), the generated output files (output_tables.xlsx and Plan de fertilizare.xlsx), the source code (lumberx.py), as well as illustratives (Fig1.png, Fig2.png, Fig3.png). The Shiny version is available here:

https://github.com/calinadriancomes/RPA_shiny.

All materials are open access and freely available for inspection, reuse, and further development, in accordance with the principles of transparent and reproducible research.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, C.A.C. and M.K.; methodology, V.P.B; software, C.A.C and M.K.; validation, C.C.A, P.P.N and C.A.C; formal analysis, M.K. and V.P.B.; investigation, C.A.C and M.K.; resources, P.P.N.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.C and V.P.B.; writing—review and editing, V.P.B. and M.K.; visualization, M.K. and V.P.B.; supervision, C.A.C; project administration, C.A.C; funding acquisition, P.P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript."

Funding

This work was supported in part by the DECIDE - Digital Services for Circular Economy - a Toolbox for Regional Developers & SME project, https://interreg-danube.eu/projects/decide.

Institutional Review Board Statement

For studies not involving humans or animals.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| APIA |

Agentia de Plati si Interventie in Agricultura |

| AWU |

Annual Work Unit |

| CAP |

Common Agricultural Policy |

| ESU |

European Size Unit |

| ETL |

Extract Transform and Load |

| GAP |

Good Agricultural Practices |

| GUI |

Graphical User Interface |

| NPA |

National Phytosanitary Authority |

| NIS |

National Institute of Statistics |

| NRDP |

National Rural Development Program |

| OCR |

Optical Character Recognition |

| PP |

Pajisti si Pasuni - Meadows and Pastures |

| PPPT |

Plant Protection Product Treatments |

| RPA |

Robotic Process Automation |

| SGM |

Standard Gross Margin |

| SPAF |

Single Payment Application Form |

| SPAS |

Single Payment Application System |

| SO |

Standard Output |

| TA |

Teren Arabil - Arable Land |

References

- Abbate, S., Centobelli, P., and Cerchione, R., “The digital and sustainable transition of the agri-food sector”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2023, 122222, Vol. 187, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ivancic, L., Suša Vugec, D., and Bosilj Vukšić, V., “Robotic Process Automation: Systematic Literature Review,” in Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing Belmont, 2019, 361, pp. 280–-295. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Zhang, J., Shu, A., Chen, Y., Chen, J., Yang, Y., Tang, W., and Zhang, Y., “Study of convolutional neural network-based semantic segmentation methods on edge intelligence devices for field agricultural robot navigation line extraction,” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, vol. ED-11, no. 1, 2023, pp. 34–39, 209, 107811. [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A., Jagtap, S., Trollman, H., Garcia-Garcia, G., Duong, L. N. K., Saxena, P., Bouzembrak, Y., Treiblmaier, H., Para-Lo̧pez, C., Carmona-Torres, C., Dev, K., Mhlanga, D., and and ït-Kaddour, A., “From Food Industry 4.0 to Food Industry 5.0: Identifying technological enablers and potential future applications in the food sector,” Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety., 2024, vol. 23, no. 6, e370040. [CrossRef]

- Rose, D. C., Lyon, J., De Boon, A., Hanheide, M., and Pearson, S. , “Responsible development of autonomous robotics in agriculture,” Nature Food., 2, 2021, pp. 306–309. [CrossRef]

- Wakchaure, M., Patle, B. K., and Mahindrakar, A. K., “Application of AI techniques and robotics in agriculture: A review,” Artificial Intelligence in the Life Sciences, 3, 2023, 100057. [CrossRef]

- Taulli, T., “RPA Foundations,” in The Robotic Process Automation Handbook: A Guide to Implementing RPA Systems,, 2020, pp. 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Jha, K., Doshi, A., Patel, P., and Shah, M., “A comprehensive review on automation in agriculture using artificial intelligence,” Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture, 2, 2019, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Law 37, “Legea nr. 37 din 11 martie 2015 privind clasificarea fermelor si exploatatiilor agricole,” The Parliament of Romania, 2015, [Online]. Available: https://shorturl.at/quBqk Accessed on: September 30, 2025.

- Law 18, “Legea fondului funciar nr. 18/1991,” The Parliament of Romania, 1991, [Online]. Available: https://shorturl.at/kOGeh. Accessed on: September 30, 2025.

- Law 36, “Legea societătilor agricole,” The Parliament of Romania, 1991 [Online]. Available: https://urli.info/1gqfL. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2025.

- Popescu, A., “CONSIDERATIONS ON UTILIZED AGRICULTURAL LAND AND FARM STRUCTURE IN THE EUROPEAN UNION,” Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development,” 13, 2013, pp. 221-226, [Online]. Available: https://shorturl.at/ZOufu. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2025.

- Sterie, C., and Dumitru, E. A., “RESEARCH ON THE EVOLUTION OF THE NUMBER OF AGRICULTURAL HOLDINGS IN THE PERIOD 2002-2016, ” Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development 2020, Vol 20, Issue 3, [Online] Available: https://managementjournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol.20_3/Art63.pdfAccessed on: Dec. 1, 2025.

- O. E. Glogovetan, “Individual farms between 2002-2010 in Romania,” Bulletin of University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca. Horticulture, vol. 70, no. 2, pp. 319–325, Jan. 2013.

- FAO, “Romania - General Agricultural Census,” 2010,https://microdata.fao.org/index.php/catalog/1709, Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2025.

- Dumitrescu I., Lessons Learned from the 2002 General Agricultural Census in Romania,”, National Institute of Statistics., 2002, Romania, [Online] Available:https://shorturl.at/gFjBO Accessed on: Oct. 2, 2025.

- ICPA, “PLANUL DE FERTILIZARE SI REGISTRUL EVIDENTEI UTILIZĂRII FERTILIZANTILOR ÎN EXPLOATATIILE AGRICOLE,” [Online]. Available:https://shorturl.at/LOhPI Accessed on: Nov. 2, 2025.

- Python Software Foundation, “Python (Version 3.11),”, [Computer software], 2025, [Online]. Available: https://www.python.org Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2025.

- European Union, “Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2019/665 of 17 April 2019 amending Decision 2005/270/EC establishing the formats relating to the database system pursuant to European Parliament and Council Directive 94/62/EC on packaging and packaging waste,” 2019, C/2019/2805. [Online]. Available:https://shorturl.at/9M80T Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).