Submitted:

30 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Socio-Demographic Data, Vaccinations, and Illnesses

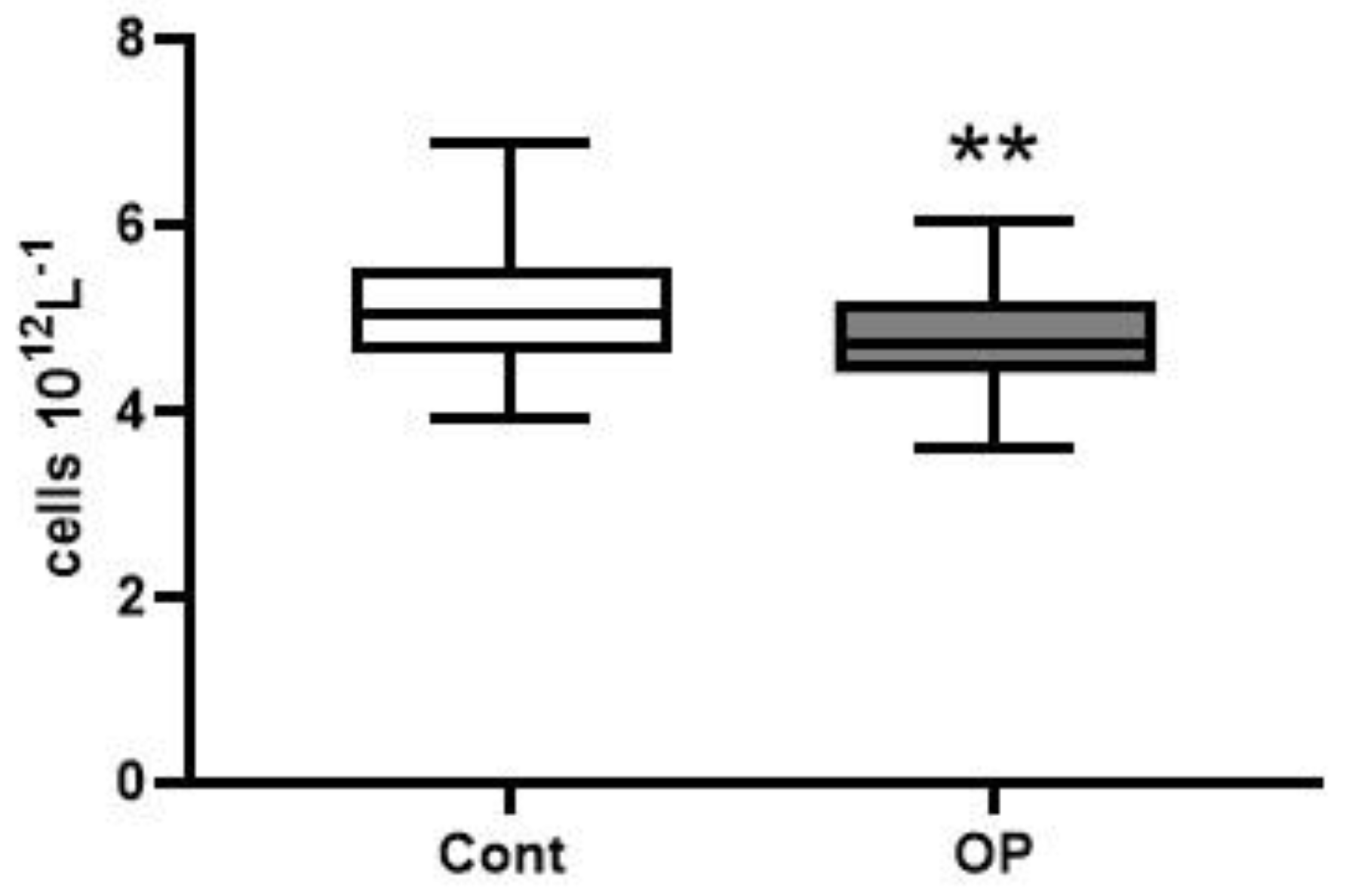

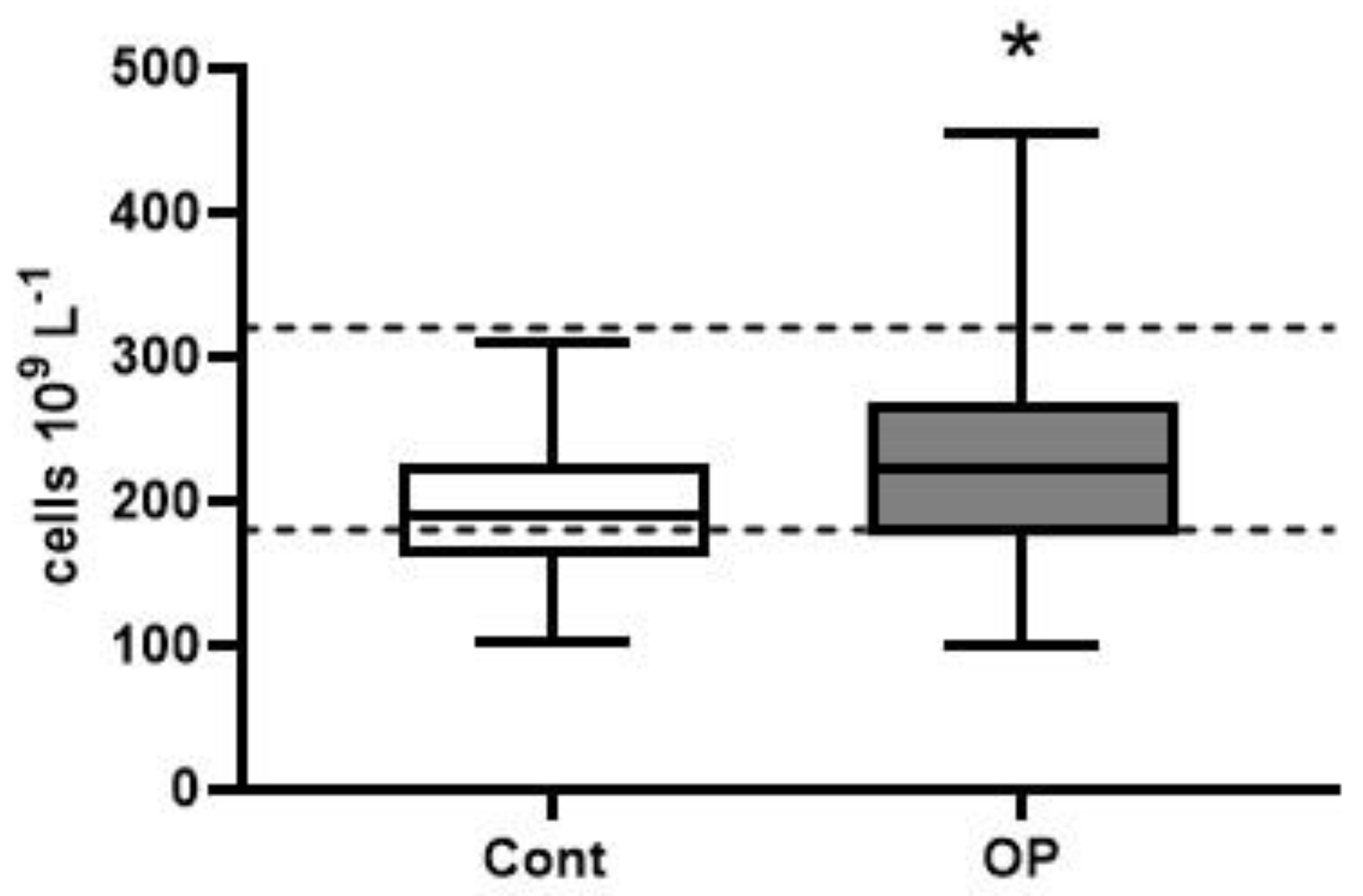

2.2. Hematological Parameters

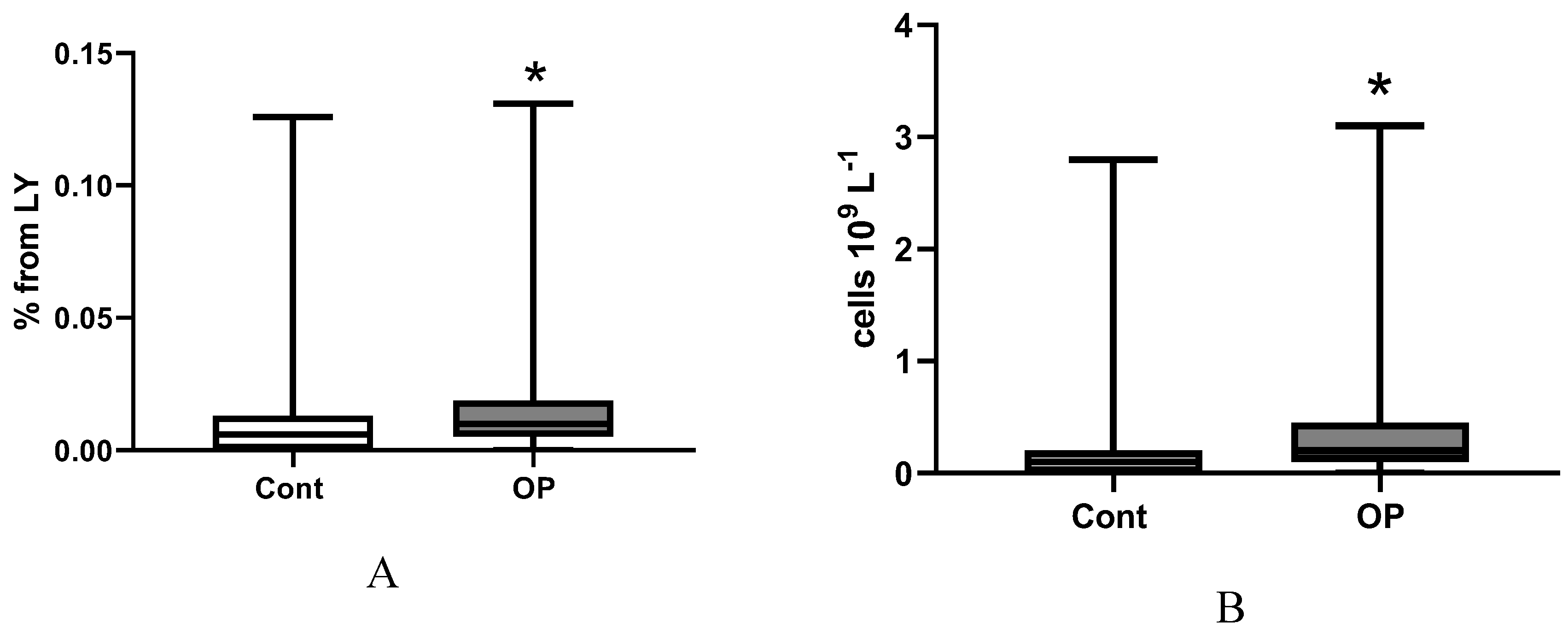

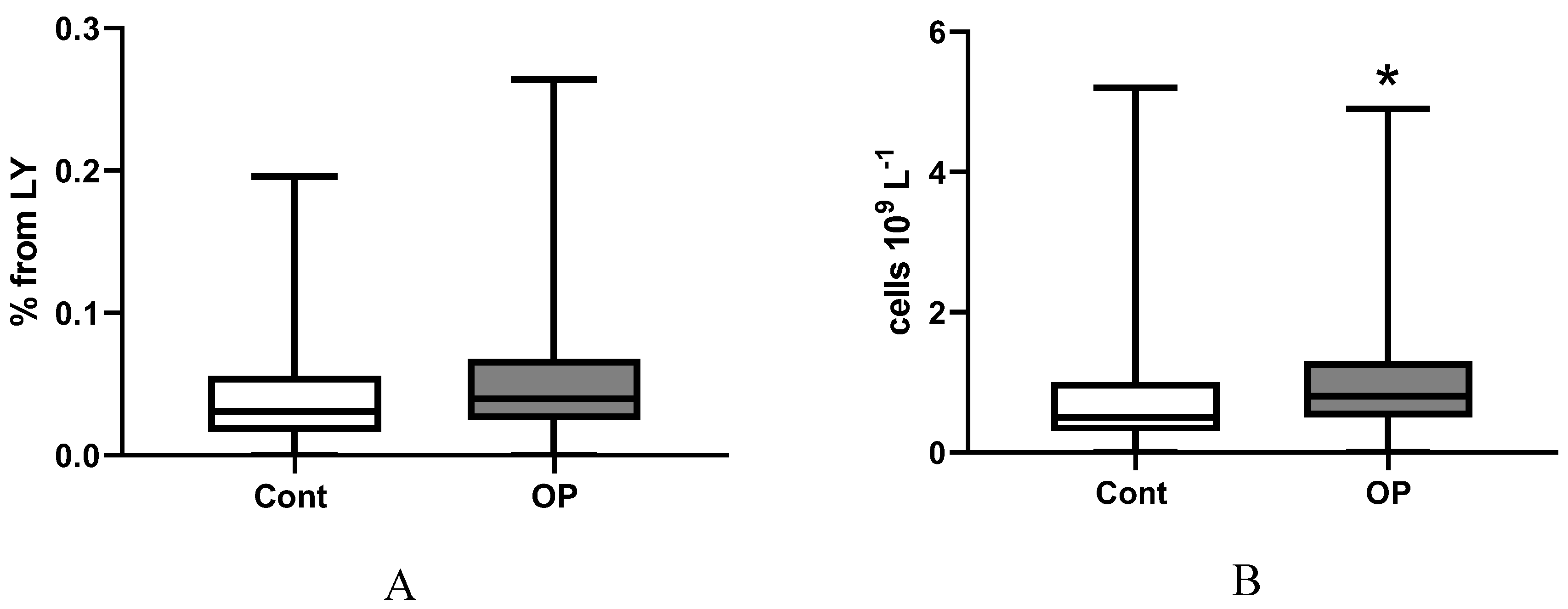

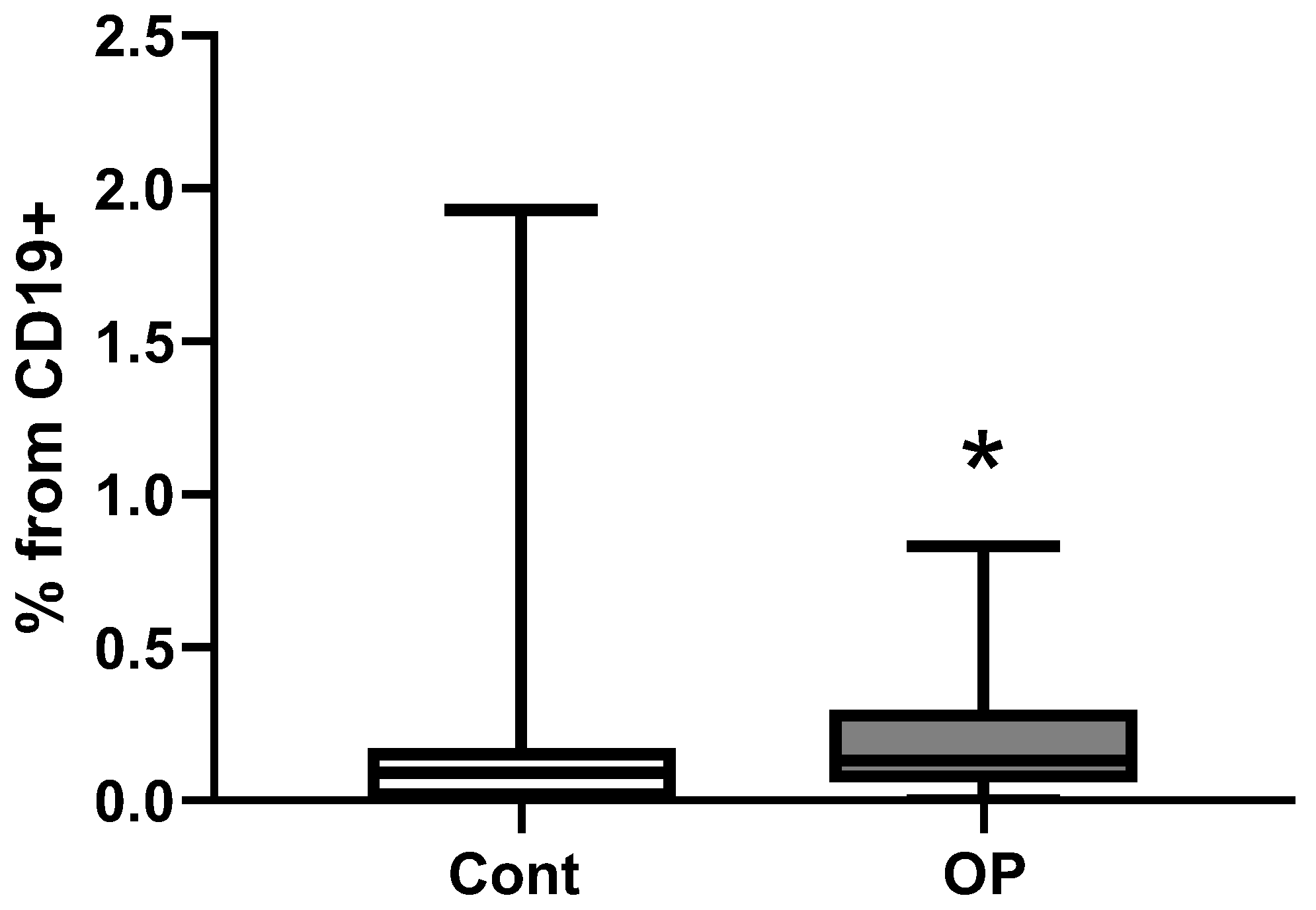

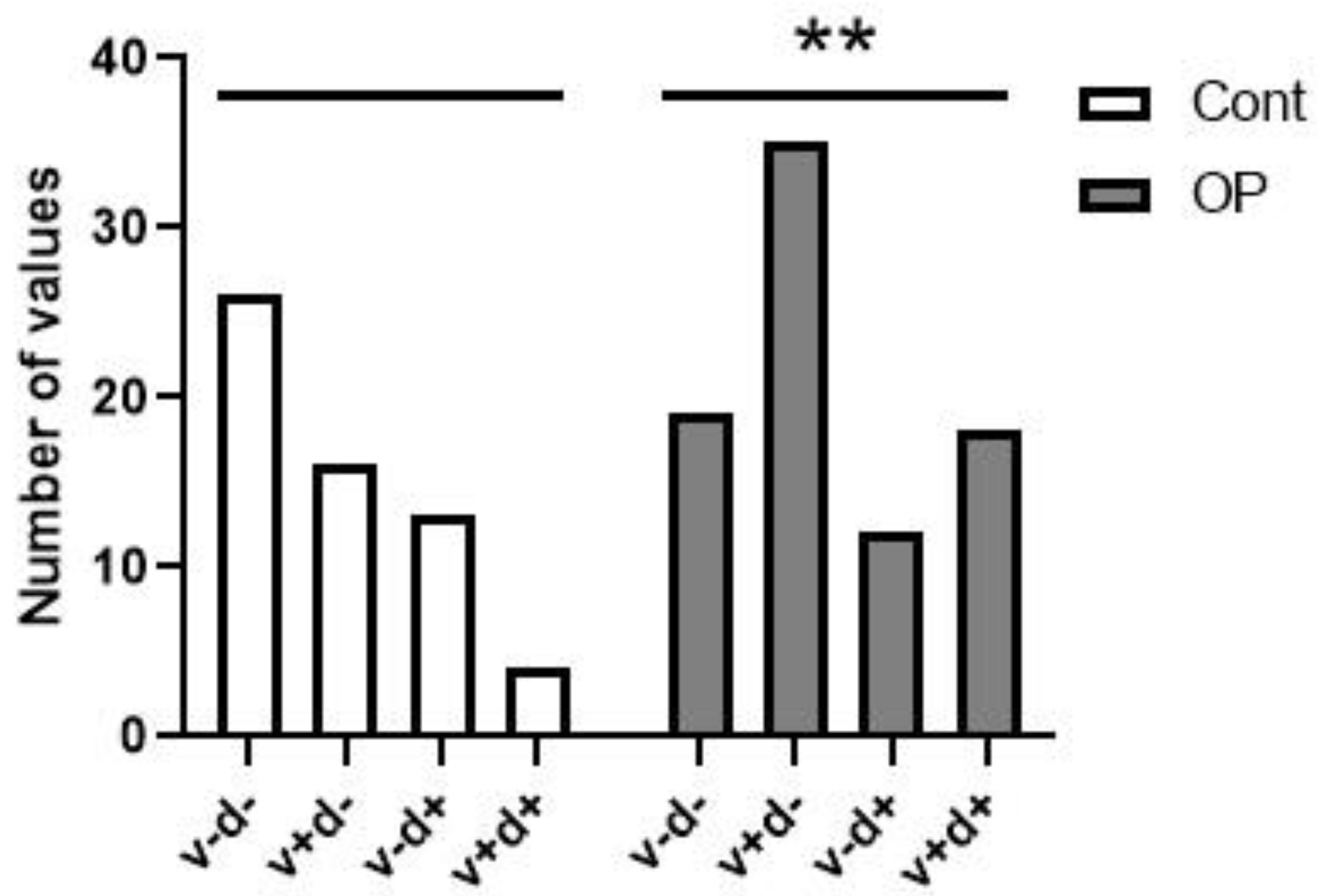

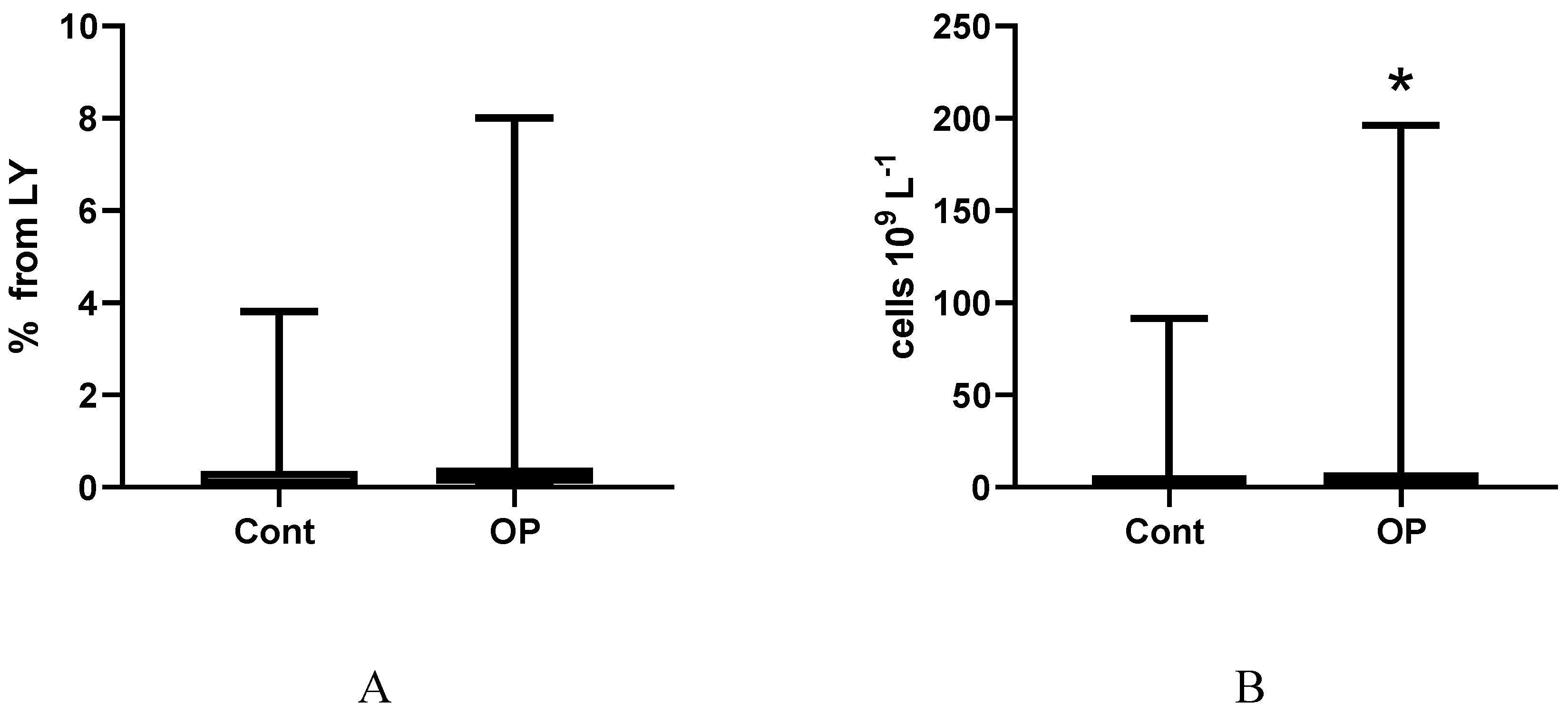

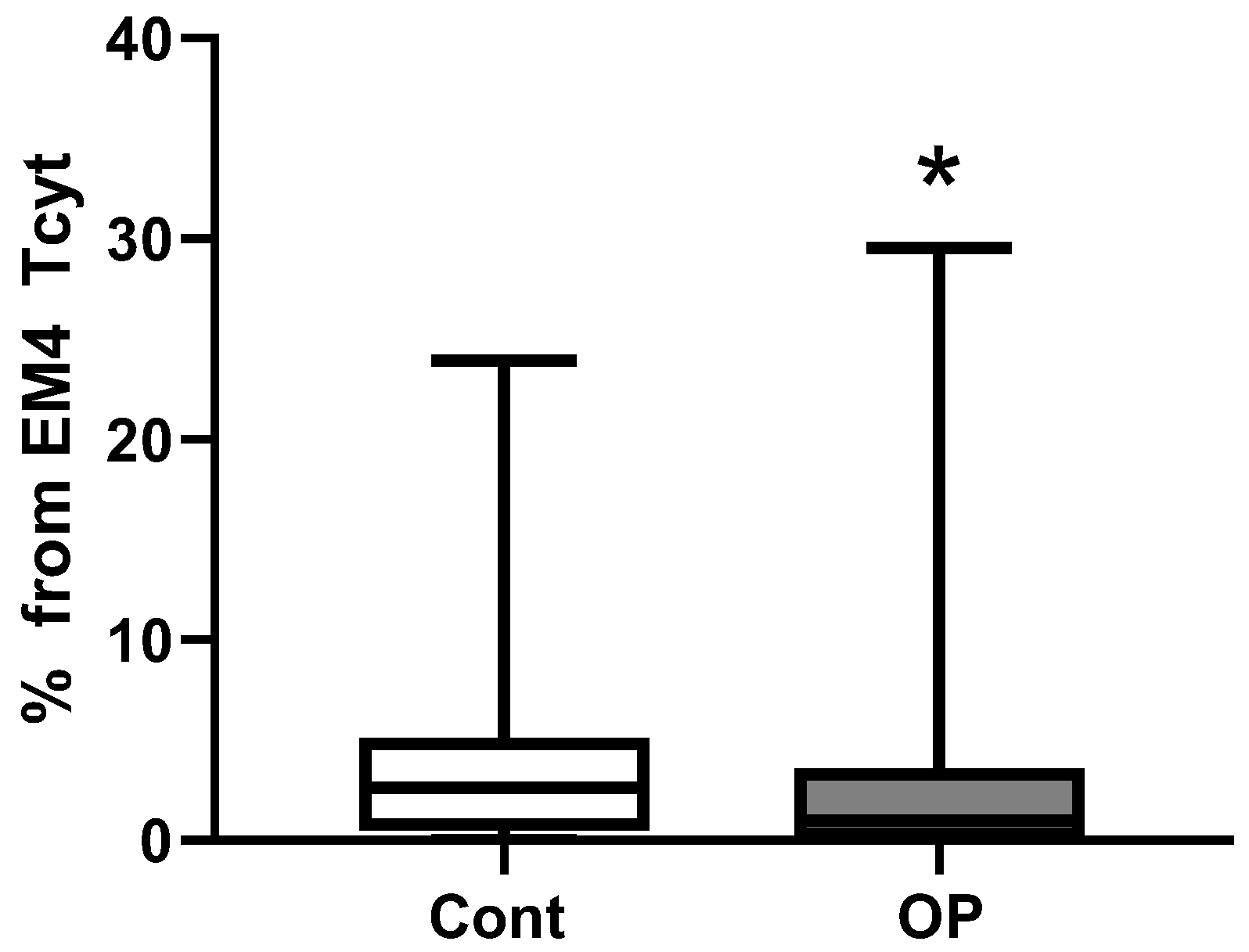

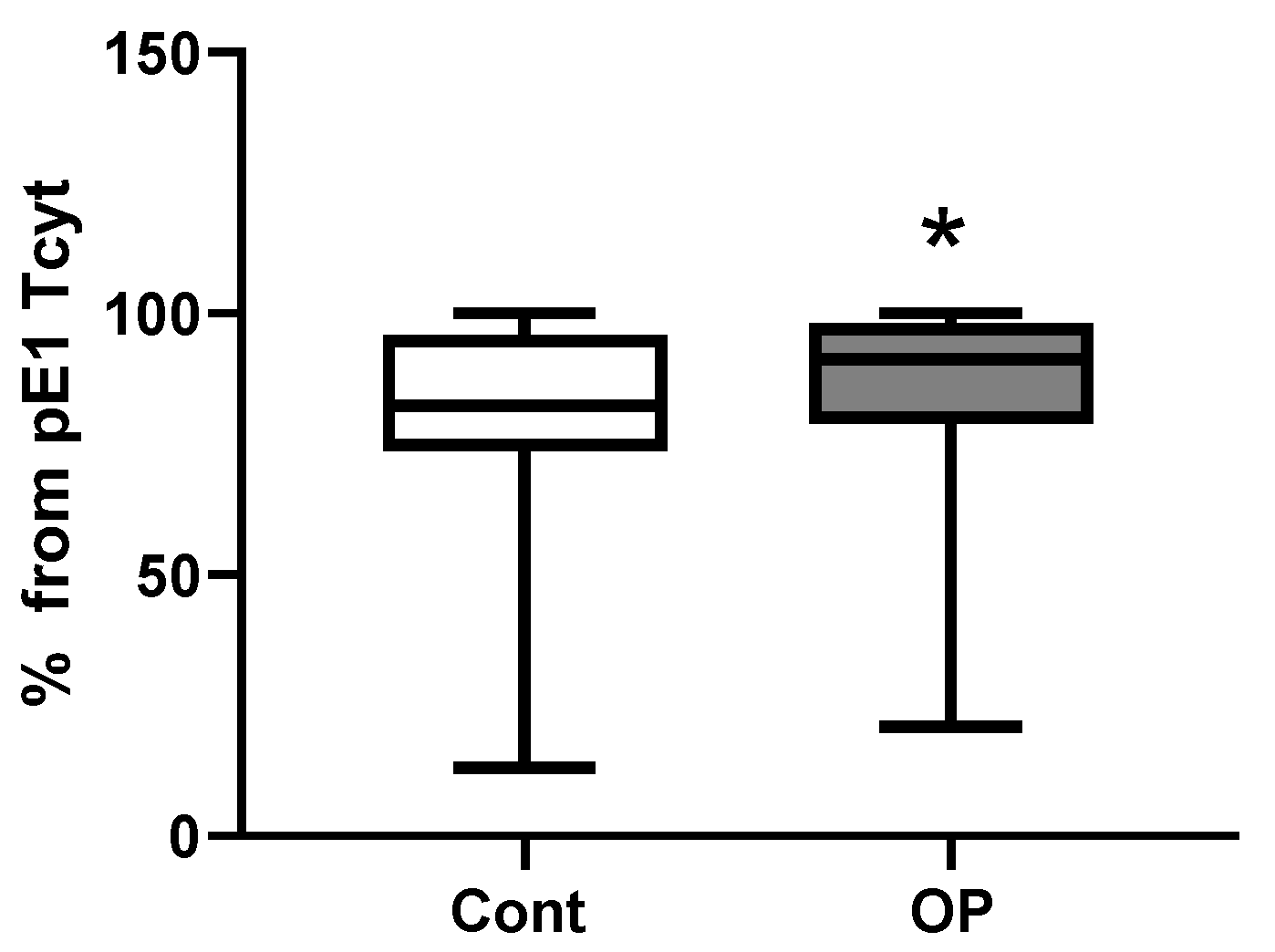

2.3. Immunological Parameters

3. Limitations of the Research

4. Discussion

5. Methodology

5.1. Study Participants

5.2. Blood Collection

5.3. Hematological Analysis

5.4. Immunological Analysis

5.4.1. Flow Cytometry B-Cell Immunophenotyping

5.4.2. T-Cell Immunophenotype by Flow Cytometry

5.4.3. Statistical Analysis

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AML | acute myeloid leukemia; |

| BMI | body mass index; |

| CM | central memory; |

| COIND | chronic organophosphate-induced neuropsychiatric disorder; |

| CVA | acute cerebrovascular accident; |

| CVD | cerebrovascular disease; |

| DM | type II diabetes mellitus; |

| EM | effector memory; |

| GID | gastrointestinal diseases; |

| IHD | ischemic heart disease; |

| MCH | mean corpuscular hemoglobin; |

| MCHC | mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; |

| MCV | mean corpuscular volume; |

| MMSE | Mini Mental State Examination; |

| MSSD | musculoskeletal system diseases; |

| NK | natural killer; |

| NLR | neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; |

| OP | occupational pathology; |

| OPIDP | organophosphates-induced delayed polyneuropathy; |

| PKC | protein kinase C; |

| PNP | polyneuropathy; |

| SAGE | Self-Administered Gerocognitive Exam; |

| TEMRA | terminal effector memory re-expressing CD45RA; |

| vWF | von Willebrand factor. |

References

- Lehman, P.C.; Cady, N.; Ghimire, S.; Shahi, S.K.; Shrode, R.L.; Lehmler, H.J.; Mangalam, A.K. Low-dose glyphosate exposure alters gut microbiota composition and modulates gut homeostasis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 100, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; AlHussaini, K.I. Pesticides: Unintended Impact on the Hidden World of Gut Microbiota. Metabolites 2024, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, X.; Lei, Y.; Jiang, X.; Kannan, K.; Li, M. Health Risks of Low-Dose Dietary Exposure to Triphenyl Phosphate and Diphenyl Phosphate in Mice: Insights from the Gut-Liver Axis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 8960–8971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokanović, M. Neurotoxic effects of organophosphorus pesticides and possible association with neurodegenerative diseases in man: A review. Toxicology 2018, 410, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.X. Pyridostigmine bromide and Gulf War syndrome. Med. Hypotheses 1998, 51, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Belinskaia, D.A.; Avdonin, P.V. Organophospate-Induced Pathology: Mechanisms of Development, Principles of Therapy and Features of Experimental Studies. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 59, 1756–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, C.; Li, H.S. [Effect of organophosphate pesticides poisoning on cognitive impairment]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi 2021, 39, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neylon, J.; Fuller, J.N.; van der Poel, C.; Church, J.E.; Dworkin, S. Organophosphate Insecticide Toxicity in Neural Development, Cognition, Behaviour and Degeneration: Insights from Zebrafish. J. Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, K. An Alternative Explanation for Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Initiation from Specific Antibiotics, Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Neurotoxins. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokanović, M.; Oleksak, P.; Kuca, K. Multiple neurological effects associated with exposure to organophosphorus pesticides in man. Toxicology 2023, 484, 153407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Popova, P.I.; Kudryavtsev, I.V.; Golovkin, A.S.; Savitskaya, I.V.; Avdonin, P.P.; Korf, E.A.; Voitenko, N.G.; Belinskaia, D.A.; Serebryakova, M.K.; Matveeva, N.V.; Gerlakh, N.O.; Anikievich, N.E.; Gubatenko, M.A.; Dobrylko, I.A.; Trulioff, A.S.; Aquino, A.D.; Jenkins, R.O.; Avdonin, P.V. Immunological Profile and Markers of Endothelial Dysfunction in Elderly Patients with Cognitive Impairments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Popova, P.I.; Nadeev, А.D.; Belinskaia, D.A.; Korf, E.A.; Avdonin, P.V. Endothelium, Aging, and Vascular Diseases. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 60, 2191–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Zhao, Z.; Montagne, A.; Nelson, A.R.; Zlokovic, B.V. Blood-Brain Barrier: From Physiology to Disease and Back. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 21–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ke, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Pu, J. Decoding immune aging at single-cell resolution. Trends Immunol. 2025, S1471-4906(25)00220-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, D.A. Ageing, Nutrition, and Infection: The Forgotten Triad. Br. J. Hosp. Med. (Lond). 2025, 86, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunas-Rangel, F.A. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in aging: Trends and clinical implications. Exp. Gerontol. 2025, 211, 112908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Mallat, Z.; Weyand, C. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms mediate cardiovascular diseases from head to toe. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 2503–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, E.L.; Weir, T.L.; Gentile, C.L. Exploring the Impact of Intermittent Fasting on Vascular Function and the Immune System: A Narrative Review and Novel Perspective. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2025, 45, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnhorst, J.Ø.; Bjørgan, M.B.; Thoen, J.E.; Natvig, J.B.; Thompson, K.M. Bm1-Bm5 classification of peripheral blood B cells reveals circulating germinal center founder cells in healthy individuals and disturbance in the B cell subpopulations in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 3610–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, I.; Wei, C.; Lee, F.E.; Anolik, J. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of human memory B cells. Semin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, P.; Sutter, J.A.; Goodman, N.G.; Du, Y.; Sekiguchi, D.R.; Meng, W.; Rickels, M.R.; Naji, A.; Luning Prak, E.T. Circulating B cells in type 1 diabetics exhibit fewer maturation-associated phenotypes. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 183, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liu, X.; Su, X. The role of TEMRA cell-mediated immune senescence in the development and treatment of HIV disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1284293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidrawar, S.M.; Khan, N.; Chan, Y.L.; Nayak, L.; Moss, P.A. Ageing is associated with a decline in peripheral blood CD56bright NK cells. Immun Ageing. 2006, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domaica, C.I.; Fuertes, M.B.; Uriarte, I.; Girart, M.V.; Sardañons, J.; Comas, D.I.; Di Giovanni, D.; Gaillard, M.I.; Bezrodnik, L.; Zwirner, N.W. Human natural killer cell maturation defect supports in vivo CD56(bright) to CD56(dim) lineage development. PLoS One 2012, 7, e51677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, C.M.; White, M.J.; Goodier, M.R.; Riley, EM. Functional Significance of CD57 Expression on Human NK Cells and Relevance to Disease. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtsev, I.V.; Arsentieva, N.A.; Korobova, Z.R.; Isakov, D.V.; Rubinstein, A.A.; Batsunov, O.K.; Khamitova, I.V.; Kuznetsova, R.N.; Savin, T.V.; Akisheva, T.V.; Stanevich, O.V.; Lebedeva, A.A.; Vorobyov, E.A.; Vorobyova, S.V.; Kulikov, A.N.; Sharapova, M.A.; Pevtsov, D.E.; Totolian, A.A. Heterogenous CD8+ T Cell Maturation and ‘Polarization’ in Acute and Convalescent COVID-19 Patients. Viruses 2022, 14, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazan, V.P.; Rodrigues Filho, O.A.; Jordão, C.E.; Moore, K.C. Phrenic nerve diabetic neuropathy in rats: unmyelinated fibers morphometry. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2009, 14, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Nadeev, A.D.; Jenkins, R.O.; Avdonin, P.V. Markers and Biomarkers of Endothelium: When Something Is Rotten in the State. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 9759735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musial, D.C.; Ajita, M.E.; Bomfim, G.H.S. Benefits of Cilostazol’s Effect on Vascular and Neuropathic Complications Caused by Diabetes. Med. Sci. (Basel) 2024, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, S.; Bilan, P.J.; Jaldin-Fincati, J.R.; Pang, J.; Ceban, F.; Saran, E.; Brumell, J.H.; Freeman, S.A.; Klip, A. Dynamic glucose uptake, storage, and release by human microvascular endothelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2022, 33, ar106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gu, L.; Xie, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, P.; Zhang, J.; Luo, D.; Zhang, J. Glucose transport, transporters and metabolism in diabetic retinopathy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 166995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, C. Oxidative Stress: A Culprit in the Progression of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.S.; Seo, J.W.; Han, N.J.; Choi, J.; Lee, K.U.; Ahn, H.; Lee, S.K.; Park, S.K. High glucose-induced NF-kappaB activation occurs via tyrosine phosphorylation of IkappaBalpha in human glomerular endothelial cells: Involvement of Syk tyrosine kinase. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2008, 294, F1065–F1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahwa, R.; Nallasamy, P.; Jialal, I. Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 mediate hyperglycemia induced macrovascular aortic endothelial cell inflammation and perturbation of the endothelial glycocalyx. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2016, 30, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, J.D.; Chen, C.; Nguyen, J.; Milbauer, L.; Abdulla, F.; Alayash, A.I.; Smith, A.; Nath, K.A.; Hebbel, R.P.; Vercellotti, G.M. Heme triggers TLR4 signaling leading to endothelial cell activation and vaso-occlusion in murine sickle cell disease. Blood 2014, 123, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcholski, M.E.; Khurshudyan, A.; Shamskhou, E.A.; Yuan, K.; Chen, I.Y.; Kodani, S.D.; Morisseau, C.; Hammock, B.D.; Hong, E.M.; Alexandrova, L.; Alastalo, T.P.; Berry, G.; Zamanian, R.T.; de Jesus Perez, V.A. Reduced carboxylesterase 1 is associated with endothelial injury in methamphetamine-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2017, 313, L252–L266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Kuwana, M. Pathogenesis of vasculopathy in systemic sclerosis and its contribution to fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2023, 35, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.N.C.; da Silva, C.C.B.M.; Pinto, R.M.C.; da Silva Duarte, A.J.; Benard, G.; Fernandes, J.R. Tobacco exposure, but not aging, shifts the frequency of peripheral blood B cell subpopulations. Geroscience 2024, 46, 2729–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, M.I.; Yokota, T.; Medina, K.L.; Garrett, K.P.; Comp, P.C.; Schipul, A.H. Jr.; Kincade, P.W. B lymphopoiesis is active throughout human life, but there are developmental age-related changes. Blood 2003, 101, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Diaz, A.; Romero, M.; Blomberg, B.B. Human peripheral late/exhausted memory B cells express a senescent-associated secretory phenotype and preferentially utilize metabolic signaling pathways. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 87(Pt A), 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Diaz, A.; Romero, M.; D’Eramo, F.; Blomberg, B.B. Aging effects on T-bet expression in human B cell subsets. Cell Immunol. 2017, 321, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Okubo, Y.; Uehara, Y.; Sugane, K.; Agematsu, K. Regulation of aged humoral immune defense against pneumococcal bacteria by IgM memory B cell. J Immunol. 2005, 175, 3262–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffa, S.; Bulati, M.; Pellicanò, M.; Dunn-Walters, D.K.; Wu, Y.C.; Candore, G.; Vitello, S.; Caruso, C.; Colonna-Romano, G. B cell immunosenescence: different features of naive and memory B cells in elderly. Biogerontology 2011, 12, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Yang, K.; Ozen, Z.; Peng, W.; Marinova, E.; Kelsoe, G.; Zheng, B. Enhanced differentiation of splenic plasma cells but diminished long-lived high-affinity bone marrow plasma cells in aged mice. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morbach, H.; Eichhorn, E.M.; Liese, J.G.; Girschick, H.J. Reference values for B cell subpopulations from infancy to adulthood. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010, 162, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraux, A.; Klein, B.; Paiva, B.; Bret, C.; Schmitz, A.; Fuhler, G.M.; Bos, N.A.; Johnsen, H.E.; Orfao, A.; Perez-Andres, M.; Myeloma Stem Cell, Network. Circulating human B and plasma cells. Age-associated changes in counts and detailed characterization of circulating normal CD138- and CD138+ plasma cells. Haematologica 2010, 95, 1016–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.T.; Jackson, K.J.; Roskin, K.M.; Pham, T.D.; Laserson, J.; Marshall, E.L.; Seo, K.; Lee, J.Y.; Furman, D.; Koller, D.; Dekker, C.L.; Davis, M.M.; Fire, A.Z.; Boyd, S.D. Effects of aging, cytomegalovirus infection, and EBV infection on human B cell repertoires. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Blomberg, B.B. Obesity Accelerates Age Defects in Mouse and Human B Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bourcy, C.F.; Angel, C.J.; Vollmers, C.; Dekker, C.L.; Davis, M.M.; Quake, S.R. Phylogenetic analysis of the human antibody repertoire reveals quantitative signatures of immune senescence and aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islas-Vazquez, L.; Alvarado-Alvarado, Y.C.; Cruz-Aguilar, M.; Velazquez-Soto, H.; Villalobos-Gonzalez, E.; Ornelas-Hall, G.; Perez-Tapia, S.M.; Jimenez-Martinez, M.C. Evaluation of the Abdala Vaccine: Antibody and Cellular Response to the RBD Domain of SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrezenmeier, E.; Rincon-Arevalo, H.; Jens, A.; Stefanski, A.L.; Hammett, C.; Osmanodja, B.; Koch, N.; Zukunft, B.; Beck, J.; Oellerich, M.; Proß, V.; Stahl, C.; Choi, M.; Bachmann, F.; Liefeldt, L.; Glander, P.; Schütz, E.; Bornemann-Kolatzki, K.; López Del Moral, C.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Ludwig, C.; Jahrsdörfer, B.; Eckardt, K.U.; Lachmann, N.; Kotsch, K.; Dörner, T.; Halleck, F.; Sattler, A.; Budde, K. Temporary antimetabolite treatment hold boosts SARS-CoV-2 vaccination-specific humoral and cellular immunity in kidney transplant recipients. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e157836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildner, N.H.; Ahmadi, P.; Schulte, S.; Brauneck, F.; Kohsar, M.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Beisel, C.; Addo, M.M.; Haag, F.; Schulze Zur Wiesch, J. B cell analysis in SARS-CoV-2 versus malaria: Increased frequencies of plasmablasts and atypical memory B cells in COVID-19. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021, 109, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarbati, S.; Benfaremo, D.; Viola, N.; Paolini, C.; Svegliati Baroni, S.; Funaro, A.; Moroncini, G.; Malavasi, F.; Gabrielli, A. Increased expression of the ectoenzyme CD38 in peripheral blood plasmablasts and plasma cells of patients with systemic sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1072462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qu, Z.; Chen, H.; Sun, W.; Jiang, Y. Increased levels of circulating class-switched memory B cells and plasmablasts are associated with serum immunoglobulin G in primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 98, 107839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šlisere, B.; Arisova, M.; Aizbalte, O.; Salmiņa, M.M.; Zolovs, M.; Levenšteins, M.; Mukāns, M.; Troickis, I.; Meija, L.; Lejnieks, A.; Bīlande, G.; Rosser, E.C.; Oļeiņika, K. Distinct B cell profiles characterise healthy weight and obesity pre- and post-bariatric surgery. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 2023, 47, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Lei, C.; Yu, Q.; Qiu, L. The response of CD27+CD38+ plasmablasts, CD24hiCD38hi transitional B cells, CXCR5-ICOS+PD-1+ Tph, Tph2 and Tfh2 subtypes to allergens in children with allergic asthma. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, T.; Nakaseko, C.; Nishiwaki, K.; Yoshida, C.; Ohashi, K.; Takezako, N.; Takano, H.; Kouzai, Y.; Murase, T.; Matsue, K.; Morita, S.; Sakamoto, J.; Wakita, H.; Sakamaki, H.; Inokuchi, K.; Kanto CML and Shimousa Hematology Study Groups. Silent NK/T cell reactions to dasatinib during sustained deep molecular response before cessation are associated with longer treatment-free remission. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 2923–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dizaji Asl, K.; Rafat, A.; Movassaghpour, A.A.; Nozad Charoudeh, H.; Tayefi Nasrabadi, H. The Effect of -Telomerase Inhibition on NK Cell Activity in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 13, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán, M.; Vigón, L.; Fuertes, D.; Murciano-Antón, M.A.; Casado-Fernández, G.; Domínguez-Mateos, S.; Mateos, E.; Ramos-Martín, F.; Planelles, V.; Torres, M.; Rodríguez-Mora, S.; López-Huertas, M.R.; Coiras, M. Persistent Overactive Cytotoxic Immune Response in a Spanish Cohort of Individuals With Long-COVID: Identification of Diagnostic Biomarkers. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 848886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.W.; Mcfadden, S.L.; Machin, S.J.; Simson, E.; International Consensus Group for Hematology. The international consensus group for hematology review: Suggested criteria for action following automated CBC and WBC differential analysis. Lab. Hematol. 2005, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtsev, I.V.; Arsentieva, N.A.; Batsunov, O.K.; Korobova, Z.R.; Khamitova, I.V.; Isakov, D.V.; Kuznetsova, R.N.; Rubinstein, A.A.; Stanevich, O.V.; Lebedeva, A.A.; Vorobyov, E.A.; Vorobyova, S.V.; Kulikov, A.N.; Sharapova, M.A.; Pevtcov, D.E.; Totolian, A.A. Alterations in B Cell and Follicular T-Helper Cell Subsets in Patients with Acute COVID-19 and COVID-19 Convalescents. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 44, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudryavtsev, I.; Zinchenko, Y.; Serebriakova, M.; Akisheva, T.; Rubinstein, A.; Savchenko, A.; Borisov, A.; Belenjuk, V.; Malkova, A.; Yablonskiy, P.; Kudlay, D.; Starshinova, A. A Key Role of CD8+ T Cells in Controlling of Tuberculosis Infection. Diagnostics, 2023, 13, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control | ОР | |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic data | ||

| Number of people examined | 59 | 84 |

| Men | 17 (29%) | 24 (29%) |

| Women | 42 (71%) | 60 (71%) |

| Age, m±SD | 73±4 | 74±4 |

| BMI, m±SD | 28.4±4.1 n=59 |

30.0±4.6 * n=81 |

| BMI within normal range (18.5-25) | 13 (22.0%) | 13 (16.1%) |

| Overweight (BMI 25-30) | 27 (45.8%) | 28 (34.5%) |

| Obesity grade 1 (BMI 30-35) | 14 (23.7%) | 29 (35.8%) |

| Obesity grade 2 (BMI 35-40) | 4 (6.8%) | 9 (11.1%) |

| Obesity grade 3 (BMI 40 and more) |

1 (1.7%) | 2 (2.5%) |

| Proportion of smokers | 2 (3.4%) | 12 (14.6%) * |

| Education (higher) | 8 (14.5%) | 8 (10.4%) |

| Education (secondary specialized) | 33 (60.0%) | 56 (72.7%) |

| Education (secondary) | 14 (25.5%) | 13 (16.9%) |

| Vaccination | ||

| Non-recovered COVID-19 patients, not vaccinated | 26 (44.1%) | 19 (22.6%) |

| Vaccinated | 16 (27.1%) | 35 (41.7%) |

| Recovered | 13 (22.0%) | 12 (14.3%) |

| Recovered before or after vaccination, % | 4 (6.8%) | 18 (21.4%) |

| Grouped by “vaccinated” | 20 (34%) | 53 (63%) *** |

| Grouped by “recovered” | 17 (29%) | 30 (36%) |

| Drug load | 4 (3; 5) 0-20 n=58 |

5 (3; 8) *** 2-12 n=82 |

| Diseases | ||

| Ischemic heart disease (IHD) | 20 (34%) | 38 (46%) |

| Hypertention | 55 (95%) | 75 (91%) |

| Gastrointestinal diseases (GID), including hepatitis |

19 (32%) 4 (7%) |

45 (54%) * 27 (33%) *** |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | 10 (17%) | 19 (23%) |

| Oncological diseases | 3 (5%) | 4 (5%) |

| Musculoskeletal system diseases (MSSD) | 54 (92%) | 78 (95%) |

| Acute cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or chronic cerebrovascular disease (CVD) | 54 (92%) | 78 (95%) |

| Total with diagnosis of polyneuropathy (PNP), including DM |

39 (66%) | 71 (87%) ** |

| 8 (21%) | 16 (23%) | |

| PNP of the upper and lower extremities | 7 (12%) | 24 (29%) * |

| Response | Control | OP | |

| Self-assessment of memory and thinking problems | Yes | 23 (41.8%) | 45 (56.2%) |

| Sometimes | 25 (45.5%) | 31 (38.8%) | |

| No | 7 (12.7%) | 4 (5.0%) | |

| Self-assessment of balance problems | Yes | 38 (69%) | 66 (84%) * |

| No | 17 (31%) | 13 (16%) | |

| Self-assessment of feelings of anxiety, melancholy, depression | Yes | 24 (43.6%) | 45 (56.3%) |

| Sometimes | 25 (43.6%) | 25 (31.2%) | |

| No | 7 (12.8%) | 10 (12.5%) | |

| Self-assessment of personality change | Yes | 28 (50.9%) | 39 (48.8%) |

| No | 2 (3.6%) | 8 (10.0%) | |

| Do not know | 25 (45.5%) | 33 (41.2%) | |

| Self-assessment of difficulty in performing daily activities | Yes | 27 (49%) | 59 (75%) ** |

| No | 28 (51%) | 20 (25%) | |

| Data after grouping | |||

| There are problems with memory and thinking | 48 (87%) | 76 (95%) | |

| There is a feeling of anxiety, melancholy and depression | 48 (87%) | 70 (87%) | |

| There are personality changes | 28 (53%) | 39 (54%) | |

| Control | OP | |

| MMSE | 27 (26; 28) 21-30 |

27 (26; 28) 13-31 |

| SAGE | 16 (12; 18) 6-21 |

16 (12; 18) 5-21 |

| “Clock” test | 9 (8; 10) 4-10 |

8 (7; 9) 4-10 |

| Total score for three tests | 51 (47; 54) 39-60 |

50 (46; 55) 24-61 |

| Control (n=59) | OP (n=82) | |

| Subjective symptoms (0 to 9) | 8 (6; 9) 1-9 |

8 (7; 9) * 3-9 |

| Presence of pathological foot reflexes | 4 (7%) | 6 (7%) |

| Presence of pathological wrist reflexes | 1 (2%) | 10 (12%) * |

| Impaired coordination (0 to 3 signs) | 2 (2; 2) 0-3 |

2 (2; 3) 1-3 |

| Cranial changes (0 to 6 signs) | 2 (1; 2) 0-4 |

2 (1; 3) *** 0-5 |

| Vibration sensitivity disorder | 47 (80%) | 77 (94%) * |

| Impaired distal sensitivity | 33 (56%) | 68 (83%) *** |

| Depression/absence of abdominal reflexes | 39 (66%) 15 (25%) |

55 (67%) 21 (26%) |

| Depression/absence of Achilles reflexes | 20 (34%) 24 (41%) |

34 (41%) 22 (27%) |

| Depression/absence of plantar reflexes | 28 (47%) 21 (36%) |

30 (37%) 30 (37%) |

| Hypothermia of the extremities | 4 (7%) | 5 (6%) |

| Hyperhidrosis of the extremities | 26 (44%) | 31 (38%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).