1. Introduction

Modern metallurgical production operates under multidimensional nonlinear dynamics, stochastic disturbances, and incomplete measurement information. For information-control systems (ICS), this necessitates the simultaneous solution of three interconnected tasks: ensuring the reliability of technological data, implementing adaptive real-time control, and supporting well-grounded decision-making across different levels of the operational hierarchy. A critical limitation remains the processing of rapidly updating data streams while maintaining stability and interpretability of decisions under noise, anomalies, and drifting signal statistics [

1].

The integration of artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and the Industry 4.0 paradigm has led to the emergence of intelligent ICS platforms that combine SCADA, ERP, and AI modules for large-scale data analysis and predictive control [

2,

3]. Neural network models, predictive analytics, and digital twins are increasingly used to improve dispatching efficiency, optimize resource consumption, and reduce technological losses. However, most practical solutions rely either on static deep neural networks (DNN, CNN) or on recurrent architectures without a clearly formalized self-adaptation procedure. Such models are sensitive to hyperparameter selection, adapt poorly to regime changes, and often fail to exhibit sufficient noise robustness when confronted with corrupted or anomalous data [

4].

These limitations are particularly acute in metallurgy, where technological objects exhibit strong nonlinearity, delays, multivariable coupling, and high cost of control errors [

5]. Under such conditions, hybrid intelligent models are required — models that simultaneously capture temporal dependencies and multidimensional nonlinear relationships among process parameters, and that additionally include built-in mechanisms for adaptation and control of measurement reliability. The absence of a formal loop for anomaly detection and correction leads to error accumulation, degradation of forecasting accuracy, and reduced robustness of closed-loop control systems [

6,

7].

This work proposes an integrated methodology for designing ICS in metallurgical production, combining a hybrid LSTM–DNN architecture with low-discrepancy hypercube sampling (Sobol/Halton sequences) and a data reliability control module. Low-discrepancy experimental design across operating conditions and hyperparameters ensures uniform coverage of the search domain and reproducible model self-adaptation, while an ε-threshold anomaly-detection and correction loop reduces the proportion of unreliable measurements entering the control circuits. As a result, the system achieves improved forecasting accuracy, noise tolerance, and adaptive capability without requiring upgrades to the existing measurement infrastructure.

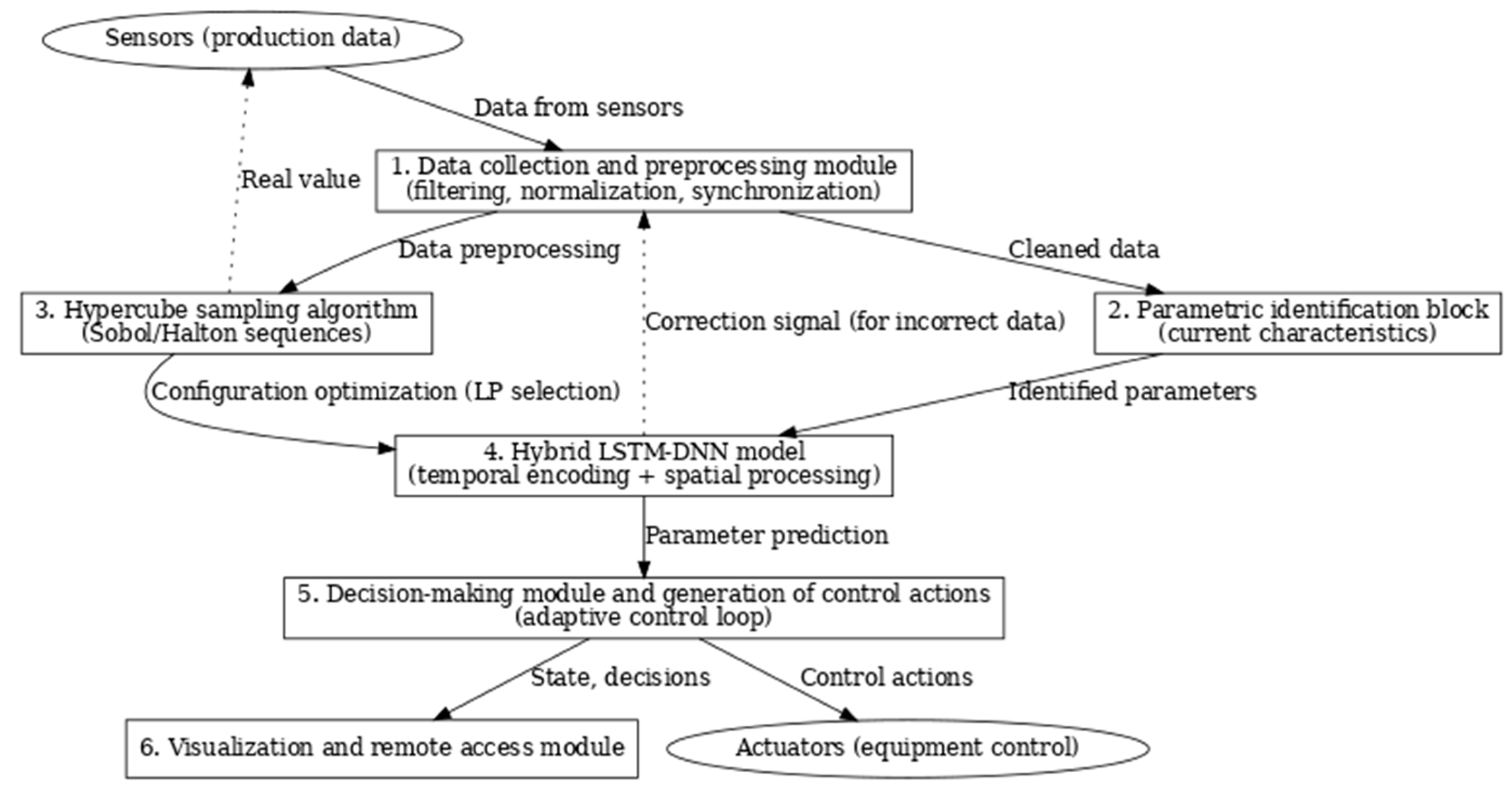

1.1. Description of the Architecture of the Information and Control System

The proposed architecture of the information and control system (ICS) is based on the modular principle and includes the following key components:

Data acquisition and preprocessing module. This module receives raw signals from process sensors and preprocesses them. During preprocessing, the data is filtered of noise, normalized to scale, and brought to a standard time scale (time-synchronized). The output is a cleaned, time-coordinated multichannel dataset ready for further analysis [

8]. The preprocessed data are then sent both to the parametric identification block and directly to the predictive model.

Parametric identification block. In this block, the dynamic identification of the controlled object’s (metallurgical unit) current characteristics is performed. Based on incoming cleaned data, approximation and stochastic state estimation are performed, allowing the determination of key process parameters in real time. In essence, the module calculates the actual object model parameters (e.g., coefficients, time constants, etc.) that reflect changing process conditions. The results of parametric identification can be used to adjust the model or control algorithms - for example, to update the internal parameters of the hybrid neural network or adapt control rules as the dynamics of the object change.

Hypercube probing algorithm (LD-sequencing). To optimize system performance, a special configuration brute-force algorithm that probes the parameter hypercube using low-dispersed sequences (LD-sequences), such as Sobol or Halton sequences, is used. This module generates a variety of combinations of input parameters (factors) in the state space of the model in such a way as to cover the entire admissible range uniformly. In contrast to random search, quasi-random LD sequences provide denser, more uniform coverage of the multidimensional space with a relatively small number of iterations. The hypercube probing algorithm is used for adaptive generation of test inputs and selection of the optimal model configuration (e.g., adjusting LSTM-DNN hyperparameters, selecting the most significant features), thereby accelerating the structural-parametric synthesis of the system. As a result, applying this algorithm improves robustness to noise and incomplete data, reducing prediction error by optimizing the model.

LSTM-DNN hybrid neural network model. The central element of the system is a hybrid neural network combining the capabilities of long short-term memory (LSTM) and deep neural network (DNN). Recurrent LSTM components are designed to analyze temporal dependencies in the data, capturing dynamic trends and sequential patterns, while fully connected DNN layers perform spatial generalization of features and detection of complex nonlinear relationships [

9]. Taken together, this LSTM-DNN architecture is capable of effectively predicting key parameters of the metallurgical process from sensor time series, as well as assessing the risks of deviations from normative values. The model is trained on historical data (and, if necessary, on synthetic data obtained, for example, by hypercube sensing) to predict current and future system states. The neural network outputs predicted values of process parameters (e.g., temperatures, pressures, compositions, etc.) for a given time horizon. These predictions are transferred to the decision-making module and also to the validity control module for comparison with actual data [

10].

-

Module of decision-making and generation of control actions (adaptive control loop). This module implements a closed-loop adaptive control for the technological process. It takes as input the predictive values generated by the hybrid neural network, along with (if necessary) information from the parametric identification block about the object’s current state. Based on these data, the module generates optimal control actions in real time. In essence, intelligent decision-making occurs: if the forecast indicates a deviation in parameter values from the desired range, the system adjusts the equipment’s operating mode in advance. Control signals (e.g., changes in material feed rates, reagent dosing, temperature control, etc.) are transmitted to actuators (e.g., drives, valves, pumps), thereby affecting the process [

10]. By integrating with the predictive model, the control loop is proactive and adaptive, automatically adjusting to changing conditions and minimizing deviations without direct operator intervention.

Validation and correction: As part of the control loop, the forecast validation subsystem plays a special role. The validation (data verification) module receives as input both actual sensor data (after preprocessing) and forecast values from the LSTM-DNN model [

11,

12]. It compares the measured and predicted values to assess the reliability of the incoming information [

13,

14,

15]. If a significant discrepancy is detected, i.e., the forecast exceeds the limits of acceptable deviation from the actual value, the system considers the real data as potentially distorted or indicates the occurrence of an emergency. In this case, a correction procedure is initiated: the validity module generates a correction signal (e.g., flags suspicious measurements, corrects them using the model, or activates backup sensors) and notifies the operator of the detected discrepancy. At the same time, adaptive reconfiguration can be triggered, e.g., repeated parametric identification to refine the object model or automatic intervention in the control process to stabilize the situation. Thus, the control loop is complemented by a self-correction mechanism: each significant prediction error triggers corrective action, thereby increasing the overall reliability and robustness of the IMS against noise, sensor failures, and unpredictable process changes.

Visualization and Remote Access Module. This module provides the user interface and system integration with external services. It displays the current states of all subsystems and key indicators: actual process parameters, model predictions, data reliability, system corrective actions, and current control actions. Visualization is performed in real time via convenient graphical screens (locally or via a web interface), allowing operational personnel to monitor IMS operations [

16]. The module also supports remote access and communication with cloud infrastructure: data and forecast results can be transferred to corporate systems (ERP, SCADA, etc.) for more exhaustive analysis and archiving. Operator feedback is also available - through the interface, individual parameters can be manually adjusted, automatic adjustments can be confirmed or cancelled, and control commands can be entered in exceptional situations. Thus, visualization and remote access serve to enhance transparency in IMS operation and to combine automatic control with human control [

17].

1.2. Interaction of Modules and Sequence of System Operation

All the above components are linked into a single information and control loop that provides a closed-loop adaptive control. The sequence of operation can be described as follows:

Data acquisition: Measuring information from sensors is continuously fed to the preprocessing module (block 1), where it is filtered and synchronized.

Identification and prediction: The cleaned data are fed simultaneously to the parametric identification unit (block 2) to update the object model and to the input of the hybrid LSTM-DNN neural network (block 4). Trained on historical and synthetic data, the LSTM-DNN model predicts current and future values of process parameters.

Model optimization: In parallel, the hypercube sensing algorithm (block 3) tries different configurations of model parameters and variants of input influences, improving the quality of the prediction and adjusting the system to current conditions. This allows for minimizing the prediction error and selecting the optimal model structure.

Adaptive control: Predictive values from the model are fed to the decision-making module (block 5), where control actions are formed. The system proactively adjusts the equipment’s operating mode (via actuators) based on predictions, without waiting for performance deterioration.

Plausibility control: at the same time, the plausibility control module (marked on the diagram near block 5) compares neural network predictions with actual data from sensors. If a discrepancy is detected outside the acceptable limits, a correction is made: for example, the input data or model is updated, and the operator receives an alarm. This step prevents the accumulation of errors caused by invalid readings and enables the system to self-tune.

Visualization and integration: All process steps - from input data to decisions made - are visualized in the interface (block 6) in a user-friendly way. Operational staff can monitor parameter values, forecasts, and system actions in real time and intervene remotely if necessary. Data is also transferred to external cloud services for storage and additional analyses.

The architecture of the hybrid LSTM-DNN information and control system for metallurgical production with LD-sequence-based hypercube sensing, validity control, decision-making, and visualization module is shown in

Figure 1.

This approach realizes a closed intelligent control loop with elements of self-learning and error correction. The hybrid LSTM-DNN model provides highly accurate forecasting, the hypercube algorithm provides efficient model tuning, and the validity module provides data reliability [

18]. As a result, the information and control system promptly adapts to process changes, increasing the efficiency and sustainability of metallurgical production [

19].

2. Methodology. Mathematical Model of the Controlled Object of the Metallurgical Process

Objects of metallurgical production, as a rule, are complex, multidimensional, dynamic systems with significant inertia, nonlinear behaviour, and sensitivity to perturbations [

20,

21]. To describe them, we introduce:

a state vector x(t)∈ ℝⁿ reflecting the internal process variables (e.g. temperatures in the furnace zones, impurity concentrations, filling levels, etc.);

vector of controls u(t)∈ ℝᵐ, specifying the controlled influences (e.g., fuel supply, reagents, feed rate of raw materials);

vector of external disturbances w(t)∈ ℝˡ (uncontrolled environmental influences, raw material properties, etc.);

The measured output parameters of the process (controlled quantities) will be denoted as y(t)∈ ℝᵖ.

A system of nonlinear equations of state can give the dynamics of the object in the general case:

where are vector-functions specifying the laws of state change and outputs depending on the current state, control, and perturbing influences. These functions are derived from physical laws (mass and energy balances, reaction rate equations, etc.) or obtained by approximating experimental data [

22]. Thus, in many units of metallurgy, the material balance equations are valid. For example, for a flow mixing unit, a linear conservative relationship can be written:

where is the flow rate or mass of the

j-th stream, and the coefficients reflect the stream topology and stoichiometric relations of the process. The presence of measurement errors leads to deviation of real data from ideal balances, which is accounted for by introducing perturbations and noise into the model. Nevertheless,

the nominal mathematical model should satisfy the basic conservation laws of matter and energy and adequately reproduce the object’s dynamics [

22,

23].

Large time constants and lags characterise the temporal behaviour of many metallurgical objects. For illustration, let us consider a simplified model of the thermal process. Let be the temperature of the metal in the furnace (state element), regulated by the supply of thermal energy

(control). A first-order approximation can approximate the energy balance:

where

C is the adequate heat capacity of the system,

k is the heat loss coefficient, and

is the ambient temperature. This differential equation describes the inertial growth of temperature under the action of heating with account of losses: at constant

the temperature tends to a stationary value determined by the equality of heat input and dissipation. Such first-order lagged models are often used to describe the dynamics of metallurgical aggregates [

24]. In the general case, however, the exact mathematical model of the control object can be very complex and multidimensional, so in practice, identified black boxes based on machine learning methods are often used [

25]. In particular, modern intelligent information and control systems increasingly usually include neural network simulators of technological objects, capable of reproducing the observed process dynamics and response to control actions [

26,

27]. Such a model makes it possible to analyze the impact of disturbances, predict the onset of critical equipment states, and optimize control in real time.

Note that the formalized object model includes stochastic components related to measurement noise and parameter uncertainty. These factors are taken into account when developing control methods and assessing system performance quality. In the present work, the mathematical model of the object is used in two ways:

for data synthesis (generation of artificial scenarios, see below);

when choosing the structure of the control model (in particular, the use of recurrent architectures to account for dynamics is justified).

2.1. Hybrid Neural Network Architecture LSTM-DNN

A hybrid neural network model combining a long short-term memory (LSTM) and a deep fully connected network (DNN) is chosen to solve the problems of prediction and adaptive control under complex dynamics. This approach is motivated by the limitations of individual architectures: classical full-link networks (DNNs) perform poorly on sequences over time because they lack a memory mechanism, and standard recurrent networks (RNNs) tend to “forget” long-term dependencies due to fading gradients. The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model is specifically designed to overcome these problems by introducing control input, output, and forgetting gates to preserve long-term information. However, recurrent memory alone is insufficient to fully reveal the nonlinear dependencies among many process variables. Adding a cascade of deep, fully connected layers, on the other hand, allows the model to generalise hidden patterns in the data and approximate complex nonlinear functions from features. Thus, the hybrid LSTM-DNN architecture combines the best of both worlds, leveraging temporal dependencies via LSTM and identifying static nonlinear relationships via DNN.

Logical structure of the model. Sequences of vectors

of dimension n (consisting of

n object parameters at each clock cycle of discrete time

t) are fed to the input of the LSTM layer. The LSTM layer processes this input sequence of length

T, storing information about previous observations in its internal state. Let us denote by

the hidden state of LSTM at step

t and by

its memory element (cells). In the simplest case, one LSTM layer with

k hidden neurons is used. Its operation is given by the following equations of vector form for each time step

t (omitting matrix dimension indices):

where

is the sigmoid, tanh is the hyperbolic tangent

;

, is the vector of input, forgetting and output gates, respectively;

is the candidate new memory values; ,

,

,

- weighting matrices for the input vectors (including recurrent links to the previous hidden state;,

,

,

,

- thresholds (biases) of these neurons; the symbol

denotes the element-by-element multiplication of the vectors. The initial state of the LSTM is usually initialized with a zero vector:

=0,

=0. As the sequence of inputs

passes through, the recurrent network generates a sequence of hidden states

, each containing rolled-up information about all previous steps. Thus, the last output

has accumulated signs reflecting the dynamics of the process for the interval

T.

Next, the DNN block comes into operation – several (one or more) fully-connected layers of the neural network, processing the LSTM output and producing the target forecast. Let us denote by

the compressed representation of the sequence (LSTM output at the last step). Then the output block may consist, for example, of two hidden layers with nonlinear activation and a final linear neuron to form a scalar forecast

(if the task is regression of a single process indicator). Formally:

where

and

are the weight matrix and displacement vector of the

j-th DNN layer,

is a nonlinear activation function on the layer (usually ReLU or similar). The vectors

represent the activities of the hidden layer neurons. In this example, the final third layer produces a prediction

without the activation function (i.e., linearly), which is suitable for continuous parameter prediction. If several parameters need to be predicted at once, the output vector is generated in a similar way (the dimensionality of

is equal to the number of targets). All parameters of the

network at the LSTM and DNN stages are selected during training on the data - usually by error back propagation with gradient optimization.

2.2. Component Targets and Model Properties

The considered architecture has a number of important properties that make it effective for metallurgical MIS tasks.

Firstly, the LSTM part serves to account for temporal dependencies: due to the presence of gates, it is able to store and retrieve information about long-term trends in the input signal without losing important correlations even with long sequences. This is especially significant for metallurgical processes where the current state depends on the prehistory (e.g., the quality of the produced alloy depends on the melting regime over the last hours, etc.).

Secondly, the DNN part acts as an approximator of complex nonlinearities: a multilayer fully connected network reveals hidden relationships between features and generates high-level generalized features. Thus, the hybrid model is able to simultaneously analyses dynamic patterns and nonlinear parameter relationships. It has been observed in the literature that such a combination yields higher accuracy and robustness compared to individual models. In particular, the LSTM-DNN model has demonstrated the ability to handle multivariate nonstationary time series and to correct measurements in real time. In addition, the LSTM-DNN hybrid is experimentally shown to outperform both pure recurrent networks (e.g., GRU) and pure convolutional or full-link networks in terms of prediction accuracy and especially in terms of noise robustness - the ability to remain operational in the presence of noise and outliers in the data. High resistance to noise is achieved due to the fact that LSTM can filter short-term spikes and outliers in the signal at the expense of memory, and DNN detects average dependencies without reacting to small random fluctuations. The paper compares with alternative architectures (DNN, GRU, CNN, etc.), where the proposed hybrid showed the highest prediction accuracy with the lowest mean square deviation of the error and better stability when noise is added. Thus, the chosen architecture is justified both from a theoretical perspective (universal approximation and memory) and by empirical metrics of process modelling quality.

2.3. Algorithm for Probing the Hypercube with Low-Diversity Sequences

In order to efficiently tune the model and generate a variety of data scenarios, the hypercube probing method - scheduling experiments in parameter space using low-dispersed Sobol and Halton sequences - is used. The idea is to uniformly cover the multidimensional space of possible combinations of parameters affecting the system with a relatively small number of trial points [

28]. In contrast to naive random search, quasi-random sequences (low-discrepancy sequences) fill the hypercube

more uniformly, reducing “skips” and clustering of points

. In fact, the Sobol and Halton sequences generate a deterministic sequence of coordinates in the

d-dimensional unit cube

, which has low dispersion (low discrepancy) relative to a uniform distribution. This means that for any sub-area

, the relative number of sequence points in

B approximates the volume of

B much more accurately than for an equal number of points chosen independently at random. Quantitatively, the variance can be characterized by the stellar discrepancy metric

, which for Sobol sequences is estimated as

, i.e. it decreases much faster than

for random sampling. Due to this, even with a limited number of trials, the quasi-random probing method covers the variant space

almost uniformly.

Sobol and Halton sequences. Both are used to generate points in the hypercube, but are based on different principles. The

Halton sequence is based on prime numbers: each dimension

j corresponds to its own prime base

(e.g. 2, 3, 5, 7,...). The

n-th point of the sequence is obtained by representing the number

n in a number system with base

and “cutting off” the digits after the decimal point. For example, the coordinate

in the first dimension

is found as a fraction formed from the binary notation of the number

n in reverse order (radical inversion in base 2). Similarly for the second dimension with base 3, etc. Formally, the

n-th point

has coordinates

where

is the decomposition of n in base

- the so-called radical-inverted function (reflecting the digits

after the decimal point). By using mutually simple bases, the Halton sequence generates non-trivial coverings of the unit cube. The Sobol sequence is constructed in a different way - based on binary fractions and primitive polynomials over GF(2). It is defined recurrently using the so-called guide vectors (numbers) chosen for each dimension. The generation uses a binary XOR operator and Gray code for index

i, which ensures high uniformity when each next point is added. The Sobol algorithm is more complex to implement, but tabular values of the guide vectors for the desired dimension are usually available. In practice, the Sobol sequence often shows slightly more uniform coverage than Halton’s, especially in high dimensions, although it is sensitive to the proper choice of generation parameters [

28]. Both approaches belong to quasi-random methods (pseudo-random vs quasi-random): the sequence points are deterministic but mimic a uniformly random distribution when projected onto any subintervals.

Hypercube coverage and applications. Hypercube probing with low-dispersion points is applied in two key contexts:

In the first case, the space of model tuning parameters (e.g., number of LSTM layers, number of neurons, learning rate, regularization factor, etc.) is treated as a hypercube in the broad sense, formed by the Cartesian product of the ranges of possible values of each hyperparameter. For continuous hyperparameters, a range of acceptable and includes the following key components, a set that can be normalized to [0,1]. The algorithm works as follows:

Definition of the search space. The d hyperparameters are specified to set up the model. Each hyperparameter j is given a range or set of values that is normalized to the interval [0,1]. Thus, the space of all combinations is a unit d-dimensional cube .

Generation of a quasi-random sample. We choose the sampling power N - the number of variants to be tried. Using a Sobol or Halton sequence generator we obtain a set of N points in .

These points are distributed almost uniformly over the entire volume of space, which provides a variety of combinations.

Reverse scaling of points. Each generated point is converted from a normalized representation to real hyperparameter values. This is done by inverse linear scaling or by selecting the nearest acceptable discrete value for each parameter. The result is a specific set of hyperparameters .

Quality assessment and selection of the best one. For each set , a hybrid LSTM-DNN model is trained (or tuned) and the quality is evaluated against a criterion (e.g., prediction error on the validation sample). Based on these results, an optimal combination of hyperparameters is selected

. Studies show that initializing the search with a Sobol sequence often finds a better model and with less variability in the result than a random search. This is because uniform coverage does not allow to “miss” narrow regions of the space with potentially good parameters.

In the second case - for data fusion - the method is similarly used to enumerate object model scenarios. Here, the dimensions of the hypercube correspond to different experimental conditions: e.g. initial states , constant parameters of the object (raw material composition, inertia characteristics), and parameters of control actions (e.g. controller setpoint levels, signal variation profiles). The goal is to generate a set of artificial process trajectories covering the widest possible range of operating modes. The algorithm is similar:

The range of each varying scenario variable is normalized (e.g., initial temperature - from the minimum to the maximum possible value, impurity concentration - within technical tolerance, etc.). The joint space of these variables forms a multidimensional rectangle (hypercube after scaling).

Using the Sobol/Halton sequence, N points - a set of conditional scenarios - are selected. For example, one point may correspond to a combination: low temperature at start, high concentration of impurity, average reagent flow rate, etc., and another point - vice versa, and so on, covering all corners of the space.

For each such combination, a run of the mathematical model of the object (section above) is carried out - either simulation modelling of the process or solving the equations of dynamics numerically. Synthetic time series

- responses of the object to the given scenario conditions - are obtained.

The generated data are included in the training set, supplementing the real data. Thus, a generalizable property is achieved: the model is trained to recognize the behavior of the object in various situations, even those that are rarely encountered in the real observation history [

29].

The hypercube probing algorithm has an important property of reproducibility. Since the Sobol and Halton sequences are deterministic, given a fixed sample size

N and point rank, any researcher will get the same set of scenarios. This facilitates comparison and repetition of experiments by other experts. In addition, this algorithm is universal: by changing the generation function (e.g., by taking a Latin hypercube or another sequence with low variance), it is possible to adapt the coverage to specific requirements, such as the exclusion of boundary points or guaranteeing the absence of correlation between the selected parameters [

30].

It is worth noting that preliminary studies show the effectiveness of using low-dispersion sequences for training neural networks. In particular, it is reported that mini-sampling or weight initialization based on the Sobol sequence can accelerate convergence and improve the accuracy of deep models compared to random initialization. Thus, the hypercube probing method is embedded in our methodology not only in the data generation and hyperparameter selection stage, but also in stages related to the stability and optimization of the neural network model itself.

2.4. Dataset Construction and Synthesis

In order to train and verify the developed model, a representative dataset reflecting the variety of operating modes of a metallurgical facility is required [

31]. In this work, the formation of the dataset was carried out in a combined way - using real production data and synthetically generated scenarios.

Real data. The basic data set is obtained from the real production automation system. The source is the archives of the automated control system of the copper smelting (beneficiation) process: readings of sensors and process parameter recorders collected in 24/7 mode. In particular, data was downloaded for the period from January to September 2024, including continuous daily measurements of approximately 30 key process parameters. These include: reagent consumption, copper concentrate grade, flotation parameters, unit temperatures and pressures, and more. This multi-dimensional time sample reflects typical changes in process parameters during actual operation of the equipment. To use these data in the model, standard preprocessing was performed: removal of coarse outliers and omissions, noise and noise filtering, and normalization of scales. Each parameter time series was scaled (e.g., by min-max or Z-score methods) to a comparable range so that no single feature dominates in order of magnitude. In addition, time synchronization was performed - since measurements of different parameters may have been written at different frequencies, the data were brought to a single discrete step (e.g.

min) by interpolation or averaging. The result is a reconciled data matrix:

where

T is the number of time steps (observations),

is the number of variables at each moment. To control overtraining, the dataset is divided into training, validation and test: the model was trained on most of the sequences, and its predictive ability was tested on delayed time intervals not used in training. This approach provides an unbiased assessment of the generalizability of the model on new data.

Synthetic data. Despite the abundance of real data, there may be situations that are poorly represented in the archive records (e.g., emergency regimes, extreme values of concentrations, rare combinations of factors). To increase the robustness of the model to such cases, the dataset was extended with artificially generated scenarios using the mathematical model of the object and the hypercube probing algorithm described above. Several critical factors were selected for variation: initial process conditions (e.g. initial melt temperature, initial impurity concentration), maximum and minimum values of control actions (intervals of reagent, air, and energy feed changes), and perturbation characteristics (possible abrupt changes in raw material composition, feed delays, etc.). Each factor is given a range covering both normal and extreme regimes. Further, using the Sobol sequence in the space of these factors, different combinations (scenarios) are selected. For each scenario, the process was modelled on a computational simulator: the equations of the object dynamics were numerically solved when the corresponding control signals were applied and the specified perturbations were implemented. In this way, synthetic time series of parameters are obtained to complement the empirical set. It is important to emphasize that the synthetic data were added carefully so as not to disturb the statistical distribution: their share in the training sample did not exceed, for example, 20-30%, and they were checked for physical meaning (absence of unrealistic values). This technique allowed to significantly enrich the variability of training situations and improve the generalization ability of the model, especially in the prediction of rare events.

2.5. Noise Accounting and Noise Immunity

One of the goals of the methodology is to make the model highly robust to measurement noise and sensor failures [

32,

33]. To this end, noise immunity is laid down at several levels. Firstly, as noted, the LSTM-DNN architecture itself partially filters noise due to its properties. Secondly, noise augmentation is applied to the training set: artificial small noise components (e.g., white Gaussian noise with zero mean and variance corresponding to the sensor error) are added to a part of the training sequences. The model, by training on the noisy data, learns not to react to small fluctuations and maintains the correct trend. Thirdly, a special test sample was prepared for objective testing of noise immunity: the original test data were deliberately distorted by adding white Gaussian noise with zero mean and standard deviation

(5% relative level). On this noisy sample, a metric for the drop in prediction accuracy compared to the clean data was measured (ratio of RMSE growth to baseline RMSE). This metric allowed us to quantify how tolerant the model is to noise. In the experiments, the hybrid LSTM-DNN model showed a minimal increase in error when noise was added (only by ~8-9%), while for comparison the classical DNN showed an error increase of more than 20%, which confirms the high

noise tolerance of the chosen approach

.

The approach to the construction of the dataset and its enrichment with synthetic examples is aimed at ensuring scientific validity and reproducibility of the results. All stages of data collection and generation are documented and the datasets used (real and generated) can be re-acquired under the same initial conditions. Filtering and normalization of the data eliminates measurement artefacts, and the variety of scenarios (real and simulated) ensures that the model does not adjust only to a narrow range of situations, but works correctly over a wide range of process parameter variations. Such a carefully formed dataset serves as a reliable basis for training the hybrid model and its subsequent validation in conditions close to real conditions of metallurgical production [

34].

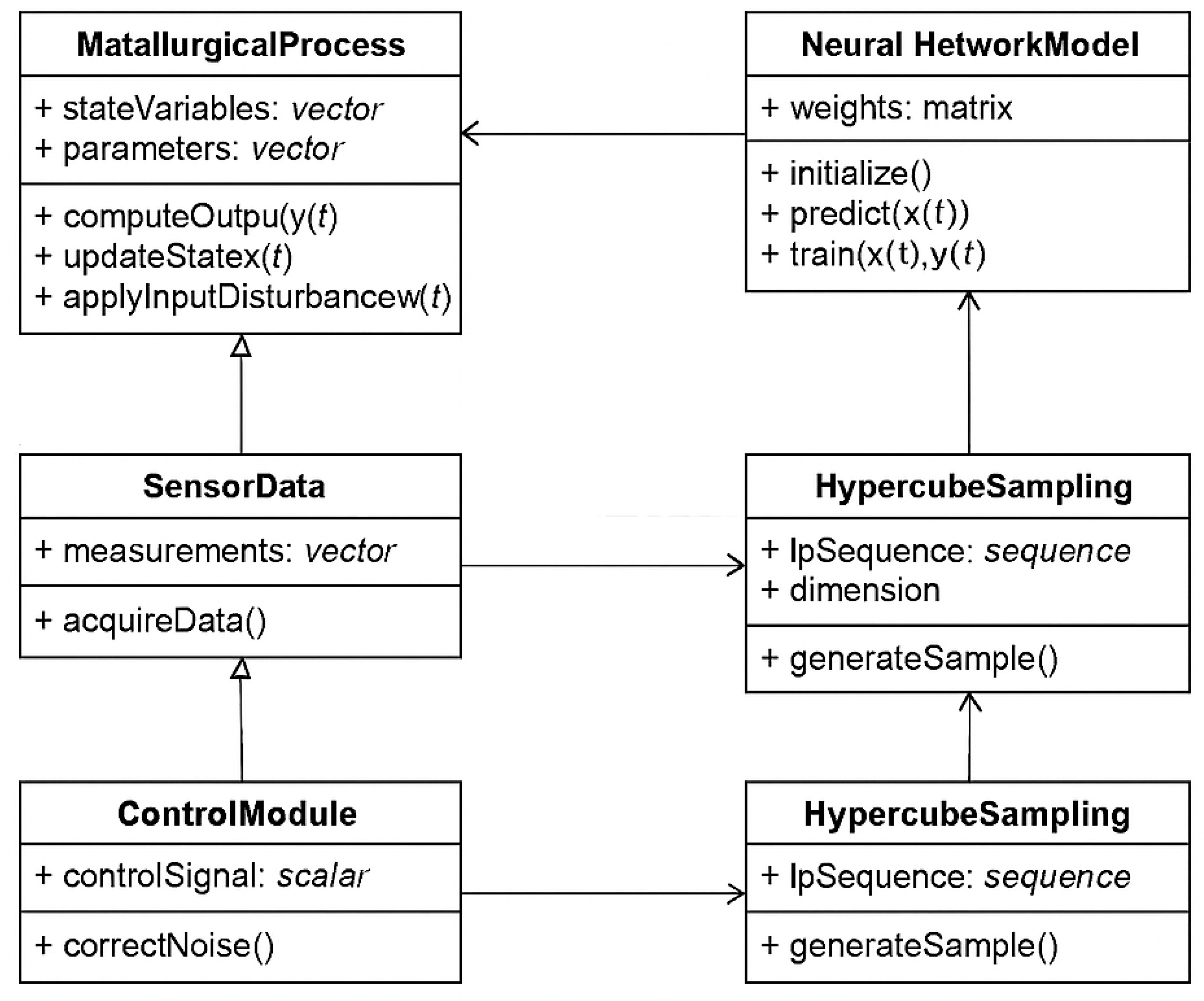

The class diagram demonstrates the main components of the system (as logical modules/classes), their attributes (data), methods (functions), as well as connections and dependencies between them. the diagram is intended to describe the architecture of the ISU, which implements intelligent control of the metallurgical process based on temporal data, parametric identification and optimization of the model configuration (

Figure 2).

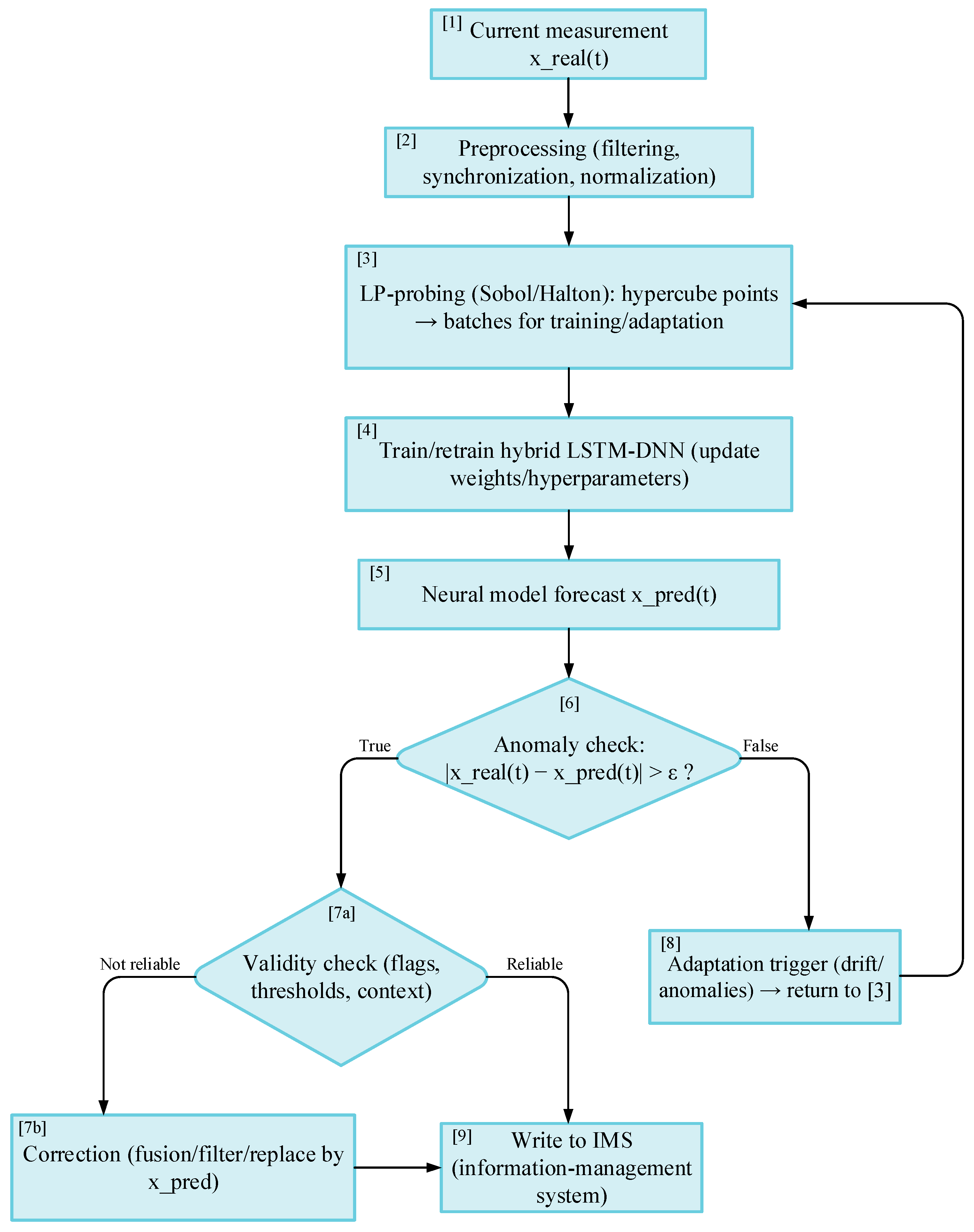

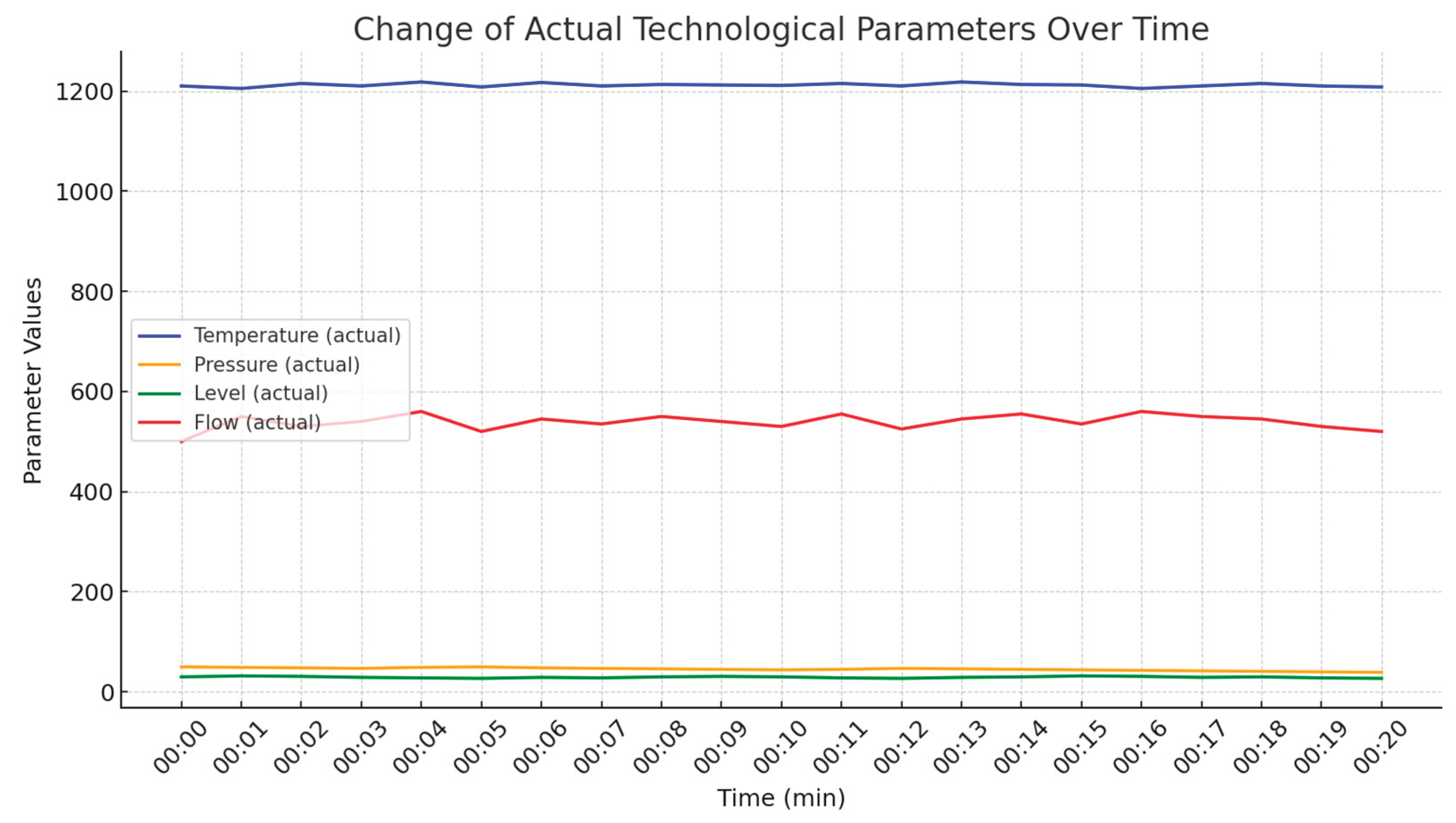

The developed algorithm implements a combined approach to prediction and verification of technological parameters of metallurgical production.

Current measurements of process parameters , obtained from sensors (temperature, pressure, level, flow rate) are input to the system. Before being fed into the model, the data undergoes preliminary processing, including noise filtering, normalization and formation of time windows.

To improve the stability and adaptability of the forecast, the LD-probing algorithm of the hypercube is used. At the probing stage, a uniform set of points in the space of input variables and hyperparameters is generated using low-dispersion Sobol or Halton sequences. The obtained points allow to retrain the hybrid neural network architecture LSTM-DNN taking into account the current conditions of the technological process.

The updated model performs a prediction of the parameters , which is compared with the actual measurements. If the deviation modulus exceeds an acceptable threshold ε, an anomaly is recorded. If systematic anomalies are detected, a repeated cycle of LD-probing and model adaptation is started.

If unreliable values are present, they are corrected based on forecast or reconstruction methods on neighboring time points.

The final reliable value (initial or corrected) together with service marks is recorded in the information management system (IMS) for further use in process control and analytics.

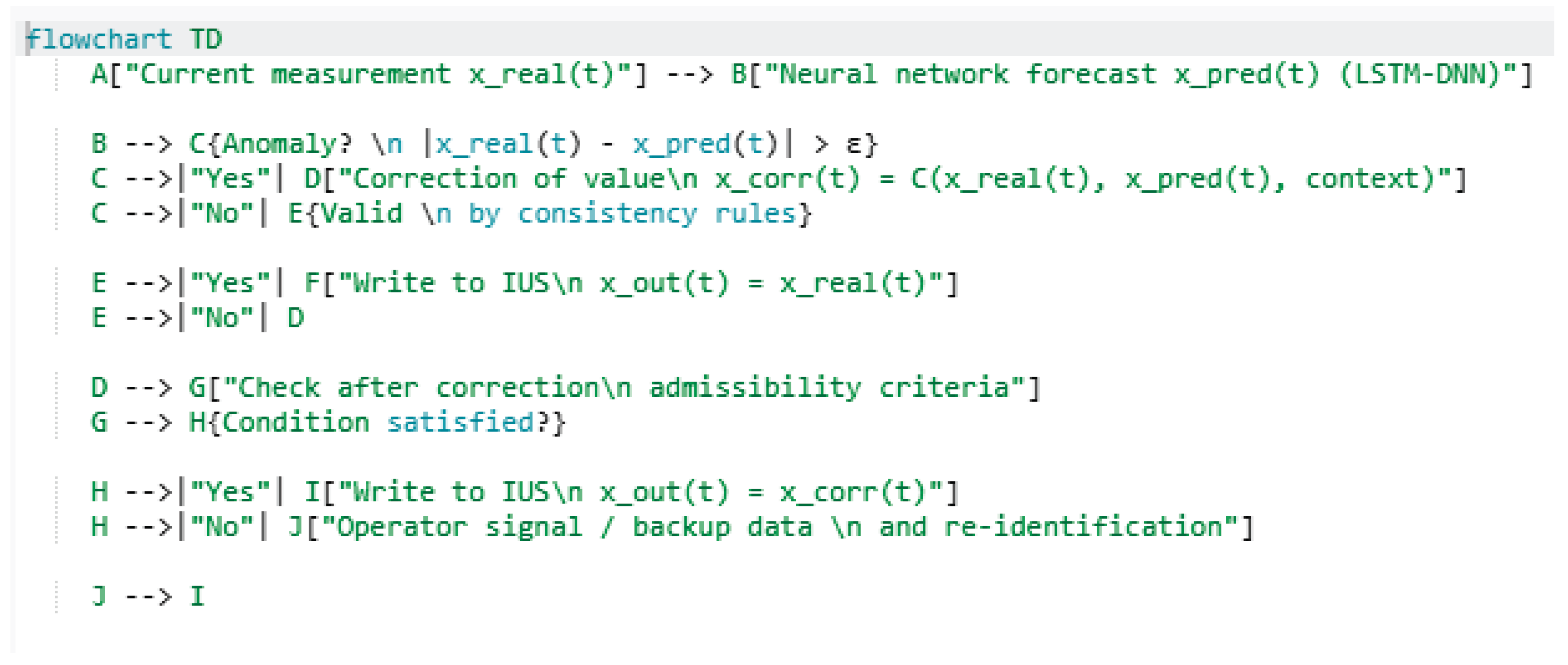

Description of the operation of the anomaly detection and correction algorithm with LD-probing and hybrid LSTM-DNN model (Figure 3):

Input data acquisition - obtaining current measurements of process parameters (temperature, pressure, level, flow) from sensors and logging systems.

Pre-processing - noise filtering, normalization, formation of time sequences for input to the model.

LD-probing of the hypercube - generation of a set of points in the space of input variables and hyperparameters using low-dispersion Sobol or Halton sequences.

Model adaptation - pre-training or tuning of the LSTM-DNN hybrid neural network architecture based on the sensing data. The procedure is performed periodically or when data drift/anomalies are detected.

Prediction - using the updated LSTM-DNN model to obtain predicted values of process parameters.

Anomaly detection - comparing the predicted value with the actual measurement; fixing the anomaly when the acceptable deviation threshold is exceeded.

Validation - assessing the quality of the predicted or corrected value using an internal validity criterion.

Correction - if unreliable values are detected, the correction is performed with reference to the model forecast or to the reconstructed value from neighbouring time points.

Recording in the IMS - fixing of the final reliable value in the information and control system together with service marks (time, source, status).

3. Results. Practical Realisation of Technological Parameters Forecasting

The work uses a synthetic dataset generated on the basis of typical profiles of technological parameters (temperature, pressure, level, flow rate) in metallurgical systems. The objective is to demonstrate the concept and verify the stability of the prediction in the presence of noise, outliers and anomalies.

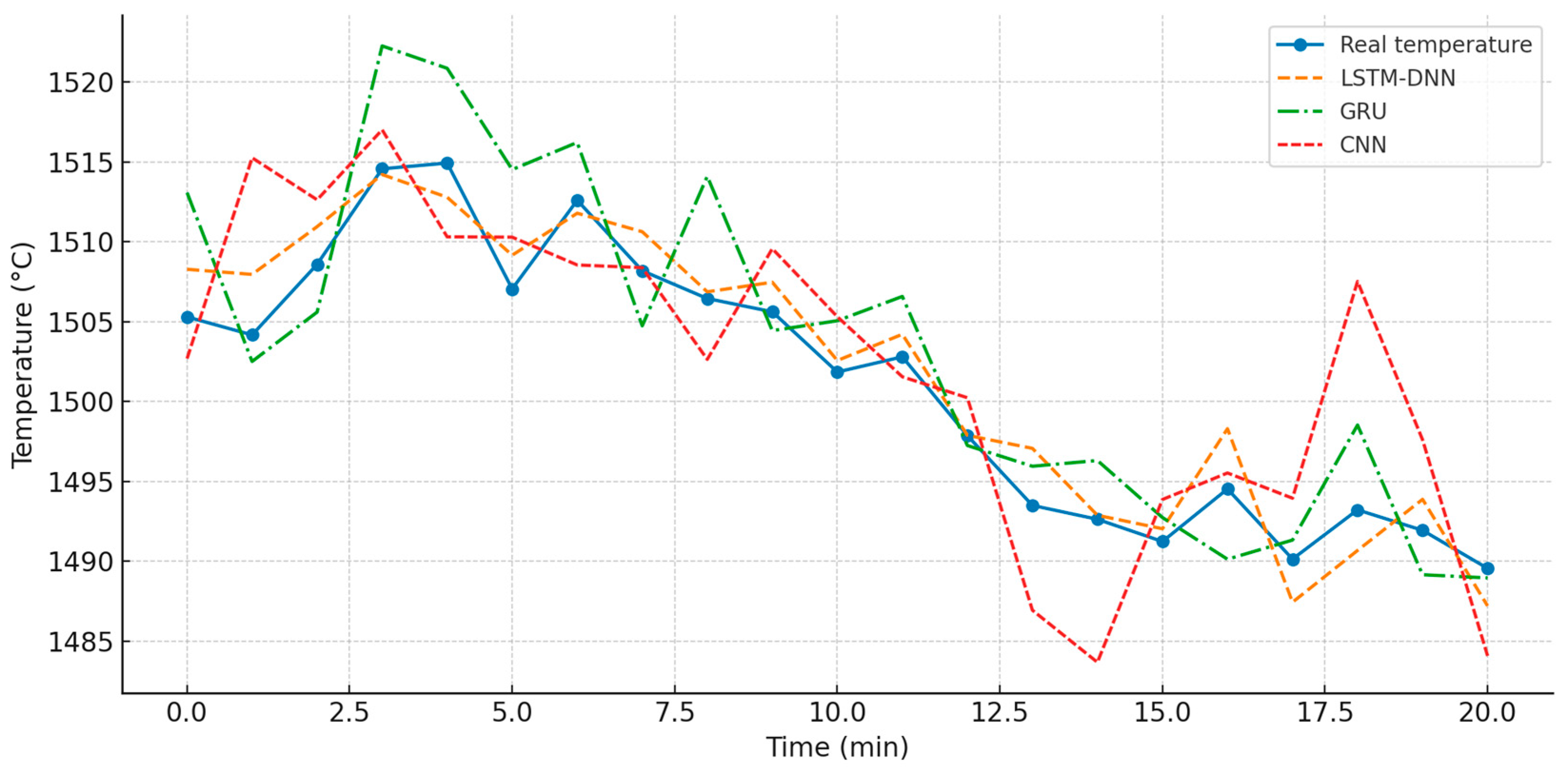

Table 1 presents the results of a simulation experiment for temperature prediction of a metallurgical process facility using different neural network model architectures: hybrid LSTM-DNN, GRU and CNN. Each row corresponds to a fixed moment of time with a step of 1 minute on the interval from 0 to 20 minutes.

For each time step the following are indicated:

real temperature value (T_real),

predicted temperature value obtained from the LSTM-DNN (T_LSTM-DNN), GRU (T_GRU) and CNN (T_CNN) models,

the calculated value of the failure function F(t), which determines the degree of deviation of the prediction from the real value,

binary indicator of reliability (1- the forecast is reliable, 0 - deviation exceeds the threshold, the forecast is unreliable).

Table 1 shows the comparison of real and forecast temperatures (LSTM-DNN, GRU, CNN), rejection function and reliability.

This form of presentation allows a comparative analysis of the models in terms of prediction accuracy, resistance to fluctuations and adaptation ability when changing the technological mode. Based on the table, quality metrics (MAE, RMSE, R²) are calculated and a graphical comparison of curves of real and predicted values is formed (

Table 2).

Figure 4 shows the comparison of temperature predictions obtained using LSTM-DNN, GRU and CNN models.

Next,

Table 3 of the experimental data: the real temperature values and predictions of the three models (LSTM, GRU, CNN) are presented for the time interval from 0 to 20 minutes. the failure function (if the error > 10 °C) and the confidence index (if the error ≤ 5 °C) for each model are also calculated.

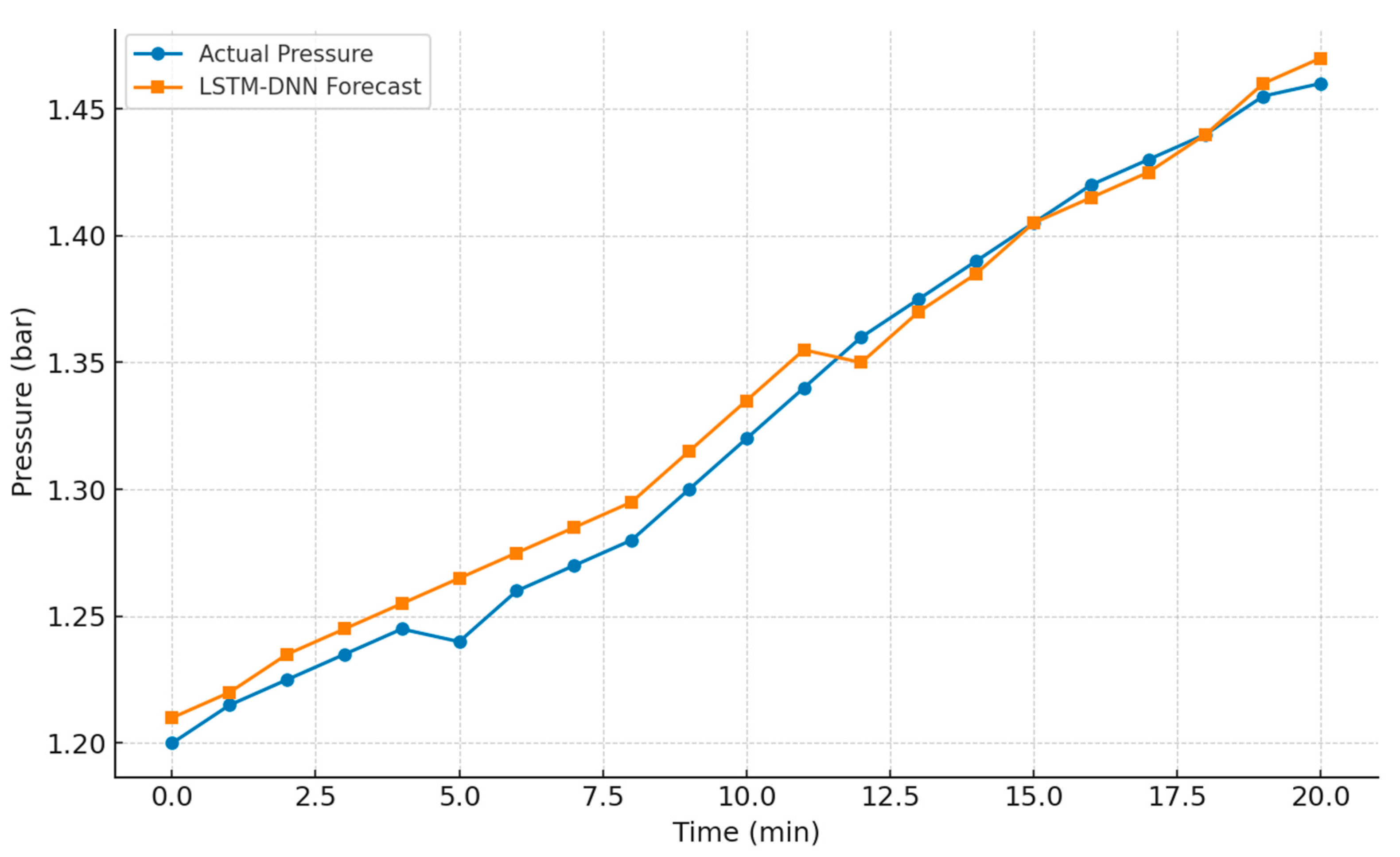

Table 4 shows the simulated pressure data, the predictions from the LSTM, GRU and CNN models, and the confidence score of each prediction:

Figure 5 summarizes the pressure changes over time, showing the comparison between the real values and the LSTM-DNN model prediction.

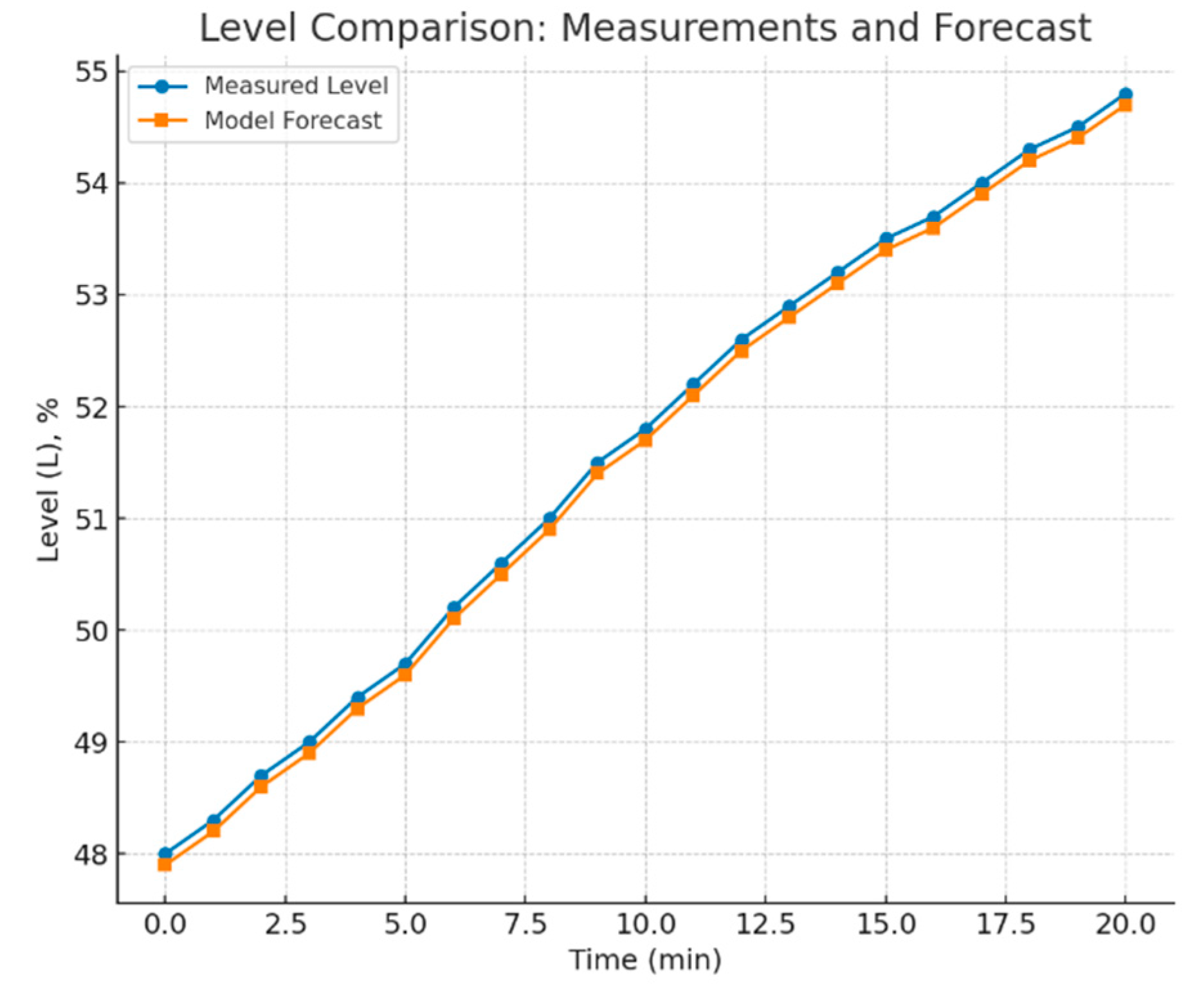

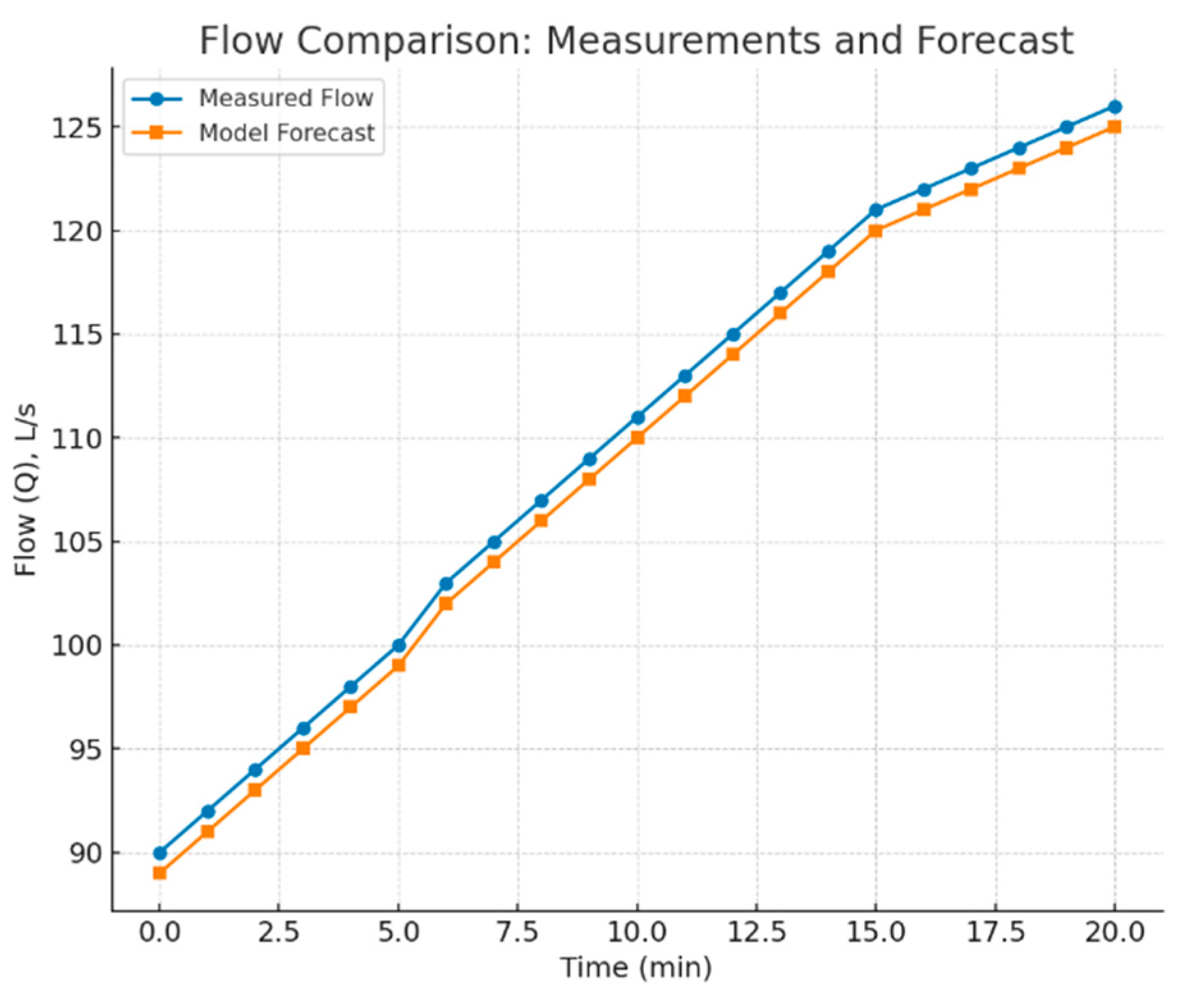

Level change (L) over time: shows the real behaviour and prediction of the LSTM-DNN model (

Figure 6). Flow rate variation (Q): similarly compares measured and predicted values (

Figure 7).

Figure 8 shows the failure function constructed from four metallurgical process parameters: temperature, pressure, level and flow rate.

If at any time at least one parameter is out of the acceptable range - the system is considered to be in a failure state (value 1). otherwise, it is considered to be in a normal state (value 0). Such peaks on the graph signal potential violations of the technological mode.

Table 5 contains synthetic (modelled) data on parameter values at each moment of time (in 1-minute increments). for each parameter are presented:

real value;

forecast of the neural network model (LSTM-DNN);

absolute forecast error (modulo);

a binary label of the forecast reliability (true/false) by the threshold value of the error.

Table 5 allows the evaluation of forecast accuracy, identifying failures, visualising anomalies and demonstrating the effectiveness of the control architecture used.

The above characteristics (

Figure 9) illustrate the behaviour of four key parameters of the technological process of metallurgical production [

35] in the time interval from 0 to 20 minutes:

temperature shows a steady increase, which is typical of the material heating stage;

pressure increases more linearly, reflecting the increasing process load;

the level fluctuates, indicating possible feed and discharge cycles;

the flow rate shows step dynamics corresponding to pumping equipment operating modes.

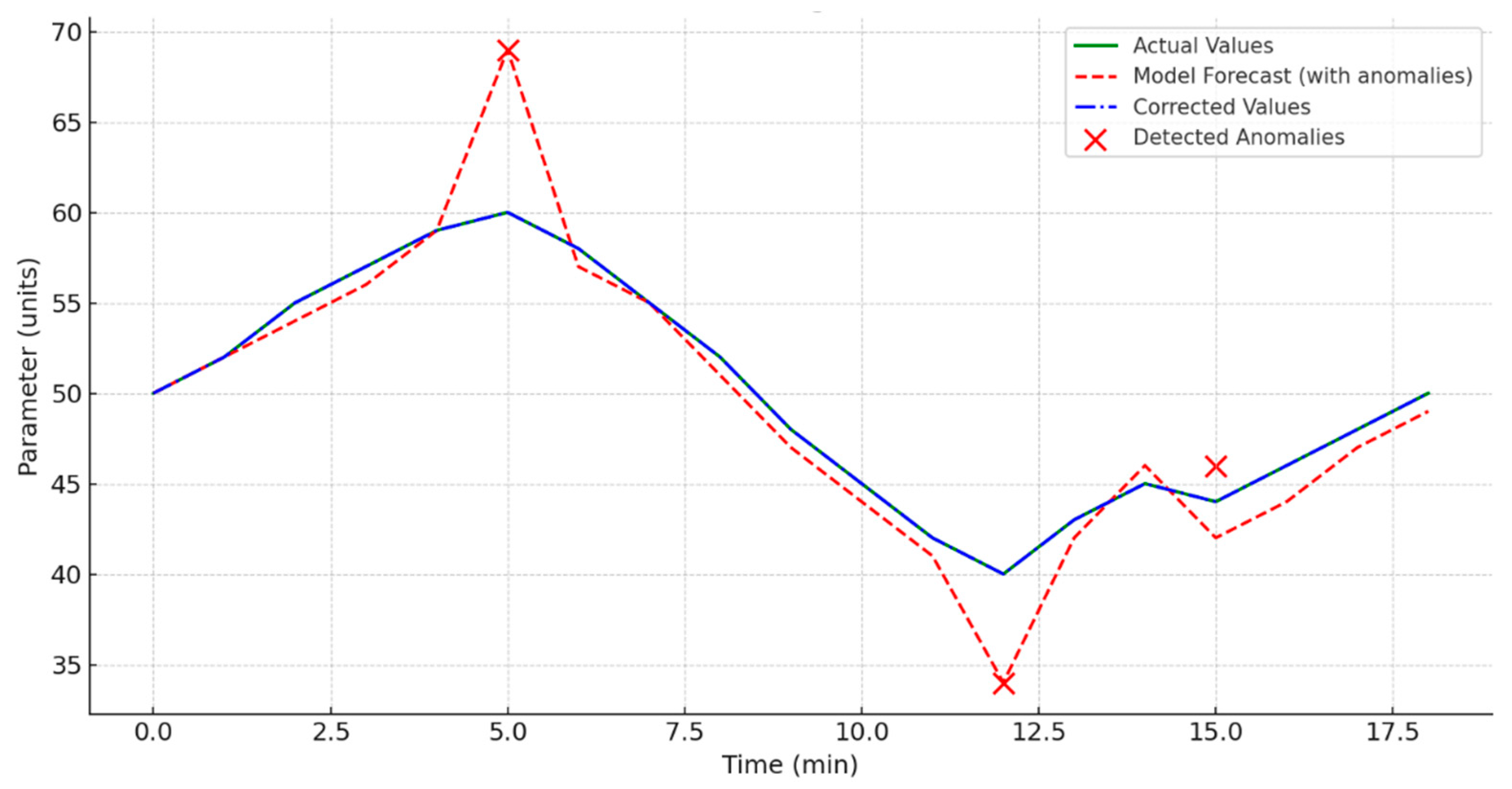

Description of the mechanism of correction of anomalous values based on the neural network model prediction [

36].

Model of measurement correction using neural network model prediction. The mechanism of automatic correction of anomalous values resulting from noise, sensor failures or external disturbances is provided within the framework of building a reliable information and control system. The correction is based on the comparison of the current measured value with the prediction obtained from the hybrid neural network model LSTM-DNN [

37,

38].

Let

denote the measured value of the technological parameter at time

t, and

denote the corresponding predicted value obtained from the model. A threshold of acceptable deviation

ε is introduced, determined either on the basis of statistical analysis or according to the technical regulations of the process [

39,

40,

41].

The correction is carried out according to the following principle:

if the deviation

does not exceed the threshold ε, the value is recognized as valid and stored;

if the deviation exceeds the threshold, the value is considered anomalous and is replaced by the model prediction:

This approach allows the exclusion of unreliable measurements from the subsequent control or analysis loop, ensuring the resilience of the system to emissions and localized disturbances [

40].

For each parameter (temperature, pressure, level, flow rate), the threshold ε is chosen individually, taking into account physical tolerances and model sensitivity. For example, for the temperature in a melting furnace the tolerance may be 5 °C and for the pressure 0.2 bar.

Logic diagram (flowchart) of the “anomaly detection and correction” module

Input: current measurement and model forecast

for the same point in time.

Anomaly test: if the absolute error exceeds the threshold ε - consider the measurement suspicious.

Correction : operator C is the chosen method (median/exponential filter, model-base interpolation, recalculation by T-P-Q-L links, or mixing.

Anomaly-free validity: additional consistency rules (gradients, physical constraints, flux balance).

Output: either the original , or the adjusted goes to the IMS when the criteria are not met - alarm and switch to redundant sensors/repeat identification.

Figure 10 shows the time series of the technological process parameter with a sampling step of 1 minute.

Blue line - true values of the parameter, reflecting the normal behaviour of the system.

Red line - forecast of hybrid neural network model LSTM-DNN, distorted by introduced anomalies modelling failures in measurement channels (spikes, outliers, drift).

Green line - values after processing by the correction module: anomalies removed or compensated for based on comparison with the model prediction and LD-probing of the hypercube for adaptation.

At the intervals where the system detected anomalies, the forecast was subjected to correction, which allowed the data to be restored to a level close to the true values. This approach increases the reliability of measurement information and reduces the risk of erroneous control actions in the IMS.

Methodology for correction of anomalies in process parameters. The process of anomaly correction is based on the joint use of hybrid neural network architecture LSTM-DNN and hypercube probing algorithm with low-dispersed sequences (Sobol/Halton) to improve the stability and accuracy of prediction.

Data acquisition and preparation - Raw parameter values (temperature, pressure, level, flow rate) are acquired from sensors in real time. Coarse outliers are filtered and data normalisation is performed at this stage.

LSTM-DNN model-based prediction - A trained model capable of accounting for both short-term fluctuations and long-term parameter dependencies is used to predict current and future values.

Built-in LD hypercube probing - Periodically or when data drift is detected, the generation of test scenarios (hypercube of input conditions) is triggered using low-dispersion sequences. The resulting points are used to refine the model to ensure adaptation to changing process conditions.

Anomaly detection - Comparison of actual measurements with the model prediction. Anomalies are defined as values that are outside the defined deviation thresholds.

Value Correction - If an anomaly is detected, the value is replaced with a corrected value based on the predicted model and the nearest valid measurements, taking into account the physical relationships between the parameters.

Record in the MIS - The corrected (or confirmed as valid) value is entered into the control system, along with the validity labels, type of correction, and algorithm performance statistics.

4. Discussion

This approach makes it possible not only to promptly eliminate one-time failures, but also to adapt to changes in the operating mode of the equipment, while maintaining high reliability of measurement data.

The considered architecture of the information and control system (

Figure 1), including the hybrid neural network model LSTM-DNN and the hypercube probing module with low-dispersed sequences (Sobol, Halton), demonstrated improved quality indicators of predicting the parameters of the technological process of metallurgical production.

Comparative modelling results (

Table 2) showed that the proposed architecture provides a 7-15% reduction in the average values of MAE, RMSE metrics and an increase in the determination coefficient R

2 by 7-15% compared to the basic LSTM, GRU and CNN models. The application of LD-sequences at the stage of model adaptation allowed for a more uniform coverage of the space of input conditions and hyperparameters compared to the Monte Carlo method, which had a positive effect on the stability and generalisation ability of the neural network model.

A comparative analysis of approaches to adaptation of neural network models showed that the use of LD probing (Sobol, Halton sequences) has a fundamental advantage over random point selection by Monte Carlo method. In the case of Monte Carlo, the sample of hyperparameters and input conditions is unevenly distributed, which, with a limited number of iterations, leads to incomplete coverage of areas with critical technological modes. LD-sequences, on the contrary, provide quasi-regular coverage of the hypercube of parameters, which increases the probability of hitting the areas where the model accuracy degrades. This is particularly important in metallurgical production, where unlikely but technologically significant regimes (e.g., overheating of metal, critical pressure, or flow rate spikes) can lead to accidents.

The algorithm of anomaly detection and correction (

Figure 3) allowed to reduce the share of unreliable measurements to less than 2% of the total data (against 8-12% in control experiments without correction). Parameter values deviating from the model prediction by more than the threshold value

ε (formula 8) were automatically classified as anomalous and corrected according to the agreed rule:

The visualization results (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) confirm that the proposed mechanism efficiently recovers correct values of temperature, pressure, level and flow rate even with sudden data spikes caused by noise, sensor drift or simulated failures.

The combined operation of LD sensing and the hybrid LSTM-DNN architecture not only improves prediction accuracy at steady-state sections of the process, but also maintains stability in the event of abrupt changes in process conditions. LSTM-component provides consideration of time dynamics and dependence between parameters, and DNN-component provides non-linear representation of multidimensional dependencies between the system state and control actions. The result is a more stable model, less susceptible to retraining and capable of rapid recovery of accuracy after sensor drift or changes in the composition of the initial data.

In general, the integration of the prediction module based on the hybrid architecture LSTM-DNN with the LD-probing procedure and the mechanism of adaptive correction of anomalies provides an increase in the reliability of measurement information, which is critical for the stable operation of the IMS in conditions of high variability of technological modes.

5. Conclusions

The integrated methodology of forecasting and monitoring of technological parameters of metallurgical production based on hybrid architecture LSTM-DNN and hypercube probing algorithm using low-disperse sequences (Sobol, Halton) is proposed.

An anomaly module has been developed that provides automatic detection and correction of unreliable temperature, pressure, level and flow measurements in real time. The module is integrated into the information and control system, which allowed to increase the stability of control processes. Experimental results have shown that the application of LD probing in model pre-training allows to reduce the adaptation time and improve the prediction accuracy compared to the initial model without probing procedure.

The hybrid LSTM-DNN architecture proved effective under highly correlated parameters and system lags, providing a coefficient of determination R² above 0,92 for predicting key process parameters in the test environment. Comparative analysis with other models (GRU, CNN) showed the advantage of the proposed approach in terms of MAE, RMSE and R² metrics, which confirms its effectiveness for industrial automation tasks.

The proposed methodology is applicable to a wide range of metallurgical and related industries, where the accuracy of prediction and reliability of control of process parameters are critical. Implementation of the system allows to reduce the risk of emergency situations, increase energy efficiency of processes and optimize equipment maintenance schedules due to early detection of anomalies and data drift.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J. Sevinov, B. Temerbekova; Methodology, J. Sevinov, B. Temerbekova, U. Mamanazarov; Software, J. Sevinov, U. Mamanazarov; Validation, J. Sevinov, G. Bekimbetova, U. Mamanazarov; Formal analysis, G. Bekimbetova, B. Bekimbetov; Investigation, J. Sevinov, U. Mamanazarov; Resources, B. Temerbekova, G. Bekimbetova; Data curation, U. Mamanazarov, G. Bekimbetova; Writing—original draft preparation, J. Sevinov, U. Mamanazarov; Writing—review and editing, B. Temerbekova, G. Bekimbetova, B. Bekimbetov; Visualization, U. Mamanazarov; Supervision, B. Temerbekova; Project administration, B. Temerbekova; Funding acquisition, B. Bekimbetov. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All used dataset are available online, which are openly accessible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICS |

Information and control systems |

| PID |

Proportional–Integral–Derivative Controller |

| IIoT |

Industrial Internet of Things |

| LSTM-DNN |

Long Short-Term Memory networks and Deep Neural Networks |

| APCS |

Automated process control system |

| SCADA |

Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| LIMS |

Laboratory Information Management System |

| MES |

Manufacturing Execution System |

| ERP |

Enterprise Resource Planning |

| FC |

Fully Connected |

| LD |

Low-Discrepancy Sequences |

| IICS |

Intelligent Information and Control Systems |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- H. Sun, “OPTIMIZING MANUFACTURING SCHEDULING WITH GENETIC ALGORITHM AND LSTM NEURAL NETWORKS,” International Journal of Simulation Modelling, vol. 22, no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Essien and, C. Giannetti, “A Deep Learning Model for Smart Manufacturing Using Convolutional LSTM Neural Network Autoencoders,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 16, no. 9, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. T. Hieu, M. di Francesco, and A. Yla-Jaaski, “A multi-resource selection scheme for virtual machine consolidation in cloud data centers,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science, CloudCom, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Rayan and Y. Nah, “Resource prediction for big data processing in a cloud data center: A machine learning approach,” IEIE Transactions on Smart Processing and Computing, vol. 7, no. 6, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Avazov, K. , Sevinov J., Temerbekova B., Bekimbetova G., Mamanazarov U., Abdusalomov A., Cho Y. I. “Hybrid Cloud-Based Information and Control System Using LSTM-DNN Neural Networks for Optimization of Metallurgical Production,” Processes, vol. 13, no. 7, 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Lan and H. Chen, “Research on Modeling and Scheduling Methods of an Intelligent Manufacturing System Based on Deep Learning,” Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, vol. 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Pikus and J. Wąs, “Using Deep Neural Network Methods for Forecasting Energy Productivity Based on Comparison of Simulation and DNN Results for Central Poland—Swietokrzyskie Voivodeship,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Abdusalomov et al., “AI-Driven Boost in Detection Accuracy for Agricultural Fire Monitoring,” Fire, no. 5, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Temerbekova, “APPLICATION OF SYSTEMATIC ERROR DETECTION METHOD TO INTEGRAL PARAMETER MEASUREMENTS IN SOPHISTICATED PRODUCTION PROCESSES AND OPERATIONS,” Tsvetnye Metally, vol. 2022, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu, D. Tang, H. Zhu, and Q. Nie, “A novel predictive maintenance method based on deep adversarial learning in the intelligent manufacturing system,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Turgunboev, B. M. Temerbekova, K. A. Usmanova, and U. B. Mamanazarov, “Application of the microwave method for measuring the moisture content of bulk materials in complex metallurgical processes,” Chernye Metally, vol. 2023, no. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Banitalebi-Dehkordi, N. Vedula, J. Pei, F. Xia, L. Wang, and Y. Zhang, “Auto-Split: A General Framework of Collaborative Edge-Cloud AI,” in Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Rahman et al., “A Cloud-Based Cyber-Physical System with Industry 4.0: Remote and Digitized Additive Manufacturing,” Automation, vol. 3, no. 3, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Z. Cao, and W. Dong, “Overview of Edge Computing in the Agricultural Internet of Things: Key Technologies, Applications, Challenges,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Z. Igamberdiyev, A. N. Yusupbekov, O. O. Zaripov, and J. U. Sevinov, “Algorithms of adaptive identification of uncertain operated objects in dynamical models,” in Procedia Computer Science, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Rai, M. K. Tiwari, D. Ivanov, and A. Dolgui, “Machine learning in manufacturing and industry 4.0 applications,” International Journal of Production Research, vol. 59, no. 16. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Shilpashree, R. R. Patil, and C. Parvathi, “‘Cloud computing an overview,’” International Journal of Engineering and Technology(UAE), vol. 7, no. 4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, H. Zhao, J. Shi, Y. Huang, and J. Xiong, “An Intelligent Fuzzing Data Generation Method Based on Deep Adversarial Learning,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Stadtfeld, “Industry 4.0 and its implication to gear manufacturing,” in American Gear Manufacturers Association Fall Technical Meeting 2015, AGMA FTM 2015, 2015.

- A. Anagnostis, E. Papageorgiou, and D. Bochtis, “Application of artificial neural networks for natural gas consumption forecasting,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 16, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Temerbekova, U. B. Mamanazarov, B. M. Bekimbetov, and Z. M. Ibragimov, “Development of integrated digital twins of control systems for ensuring the reliability of information and measurement signals based on cloud technologies and artificial intelligence,” Chernye Metally, vol. 2023, no. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Cinar, S. Kalay, and I. Saricicek, “A Predictive Maintenance System Design and Implementation for Intelligent Manufacturing,” Machines, vol. 10, no. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Dinata, S. Retno, and N. Hasdyna, “Minimization of the Number of Iterations in K-Medoids Clustering with Purity Algorithm,” Revue d’Intelligence Artificielle, vol. 35, no. 3, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang et al., “Prediction model of end-point manganese content for BOF steelmaking process,” ISIJ International, vol. 52, no. 9, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Tang, and J. Liu, “A Stacked Autoencoder with Sparse Bayesian Regression for End-Point Prediction Problems in Steelmaking Process,” IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, vol. 17, no. 2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Qiu, J. Li, and D. Chen, “Optimized long short-term memory (LSTM) network for performance prediction in unconventional reservoirs,” Energy Reports, vol. 8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Zarzycki and M. Ławryńczuk, “Advanced predictive control for GRU and LSTM networks,” Information Sciences, vol. 616, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, B. Xu, and T. L. Chung, “Definition extraction with LSTM recurrent neural networks,” in Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2016. [CrossRef]

- Cortez, B. Carrera, Y. J. Kim, and J. Y. Jung, “An architecture for emergency event prediction using LSTM recurrent neural networks,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 97, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Nosouhian, F. Nosouhian, and A. K. Khoshouei, “A review of recurrent neural network architecture for sequence learning: Comparison between LSTM and GRU,” Preprints.org, no. July, 2021.

- A. Pudikov and A. Brovko, “Comparison of LSTM and GRU Recurrent Neural Network Architectures,” in Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, vol. 337, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Jiang, S. Yuan, J. Ma, and Q. Wang, “The evolution of production scheduling from Industry 3.0 through Industry 4.0,” International Journal of Production Research, vol. 60, no. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kumas and, S. Erol, “Digital Twins as Key Technology in Industry 4.0,” JOURNAL OF POLYTECHNIC-POLITEKNIK DERGISI, vol. 24, no. 2, 2021.

- Gulyamov Shukhrat, Temerbekova Barnokhon, and Mamanazarov Ulugbek, “Noise Immunity Criterion for the Development of a Complex Automated Technological Process,” E3S Web of Conf., vol. 452, p. 3014, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhen, L. Yan, and P. Yuan, “Walking gait phase detection based on acceleration signals using LSTM-DNN algorithm,” Algorithms, vol. 12, no. 2, 2019. [CrossRef]

- É. Piel, P. Marquet, J. Soula, and J. L. Dekeyser, “Real-time systems for multi-processor architectures,” in 20th International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium, IPDPS 2006, 2006. [CrossRef]

- K. Cao, T. Zhang, and J. Huang, “Advanced hybrid LSTM-transformer architecture for real-time multi-task prediction in engineering systems,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Boubaker, M. Benghanem, A. Mellit, A. Lefza, O. Kahouli, and L. Kolsi, “Deep Neural Networks for Predicting Solar Radiation at Hail Region, Saudi Arabia,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhou et al., “Intelligent prediction monitoring system for predictive maintenance in manufacturing,” in IECON Proceedings (Industrial Electronics Conference), 2005. [CrossRef]

- Challenges and Opportunities for Deep Learning Applications in Industry 4.0. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Nawrocki, P. Osypanka, and B. Posluszny, “Data-Driven Adaptive Prediction of Cloud Resource Usage,” Journal of Grid Computing, vol. 21, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).