Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

- We present the first comprehensive survey that analyzes generative recommender systems through a tri-dimensional decomposition encompassing tokenization, architectural design, and optimization strategies, within which we organize existing work and trace the evolution of recommender systems from discriminative approaches toward the generative paradigm.

- 2.

- Through a systematic overview and analysis, we identify key trends toward efficient representation with semantic identifiers that balance vocabulary compactness and semantic expressiveness, advances in model architecture that facilitate improved scalability and resource-efficient computation, and multi-dimensional preference alignment aimed at balancing the objectives of users, the platform, and additional stakeholders.

- 3.

- We provide an in-depth discussion of its applications across different stages and scenarios, examine the current challenges, and outline promising future directions. We hope this survey will serve as a practical reference and blueprint for researchers and practitioners in both academia and industry.

2. Background and Preliminary

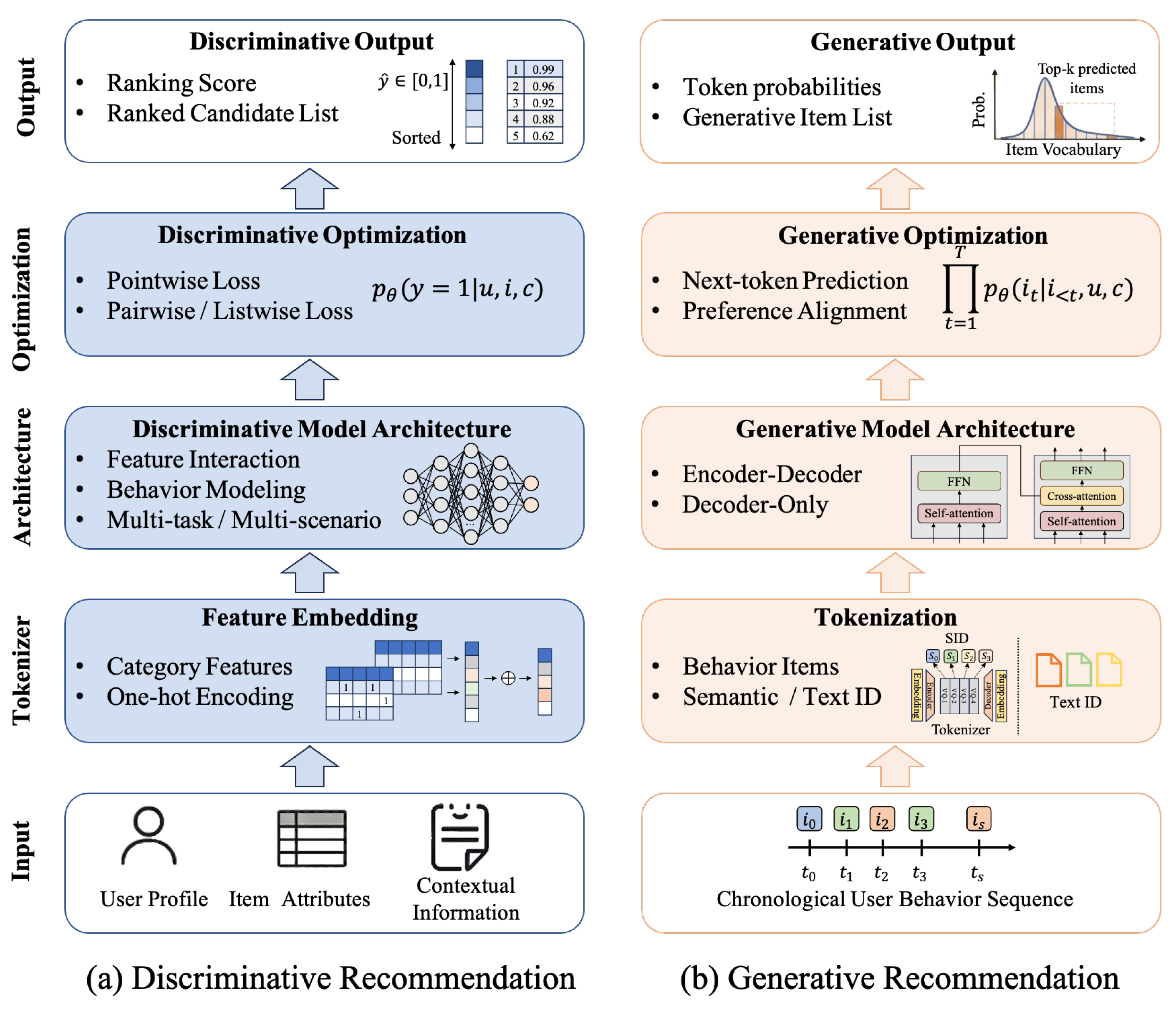

2.1. Discriminative Recommendation

2.2. Generative Recommendation

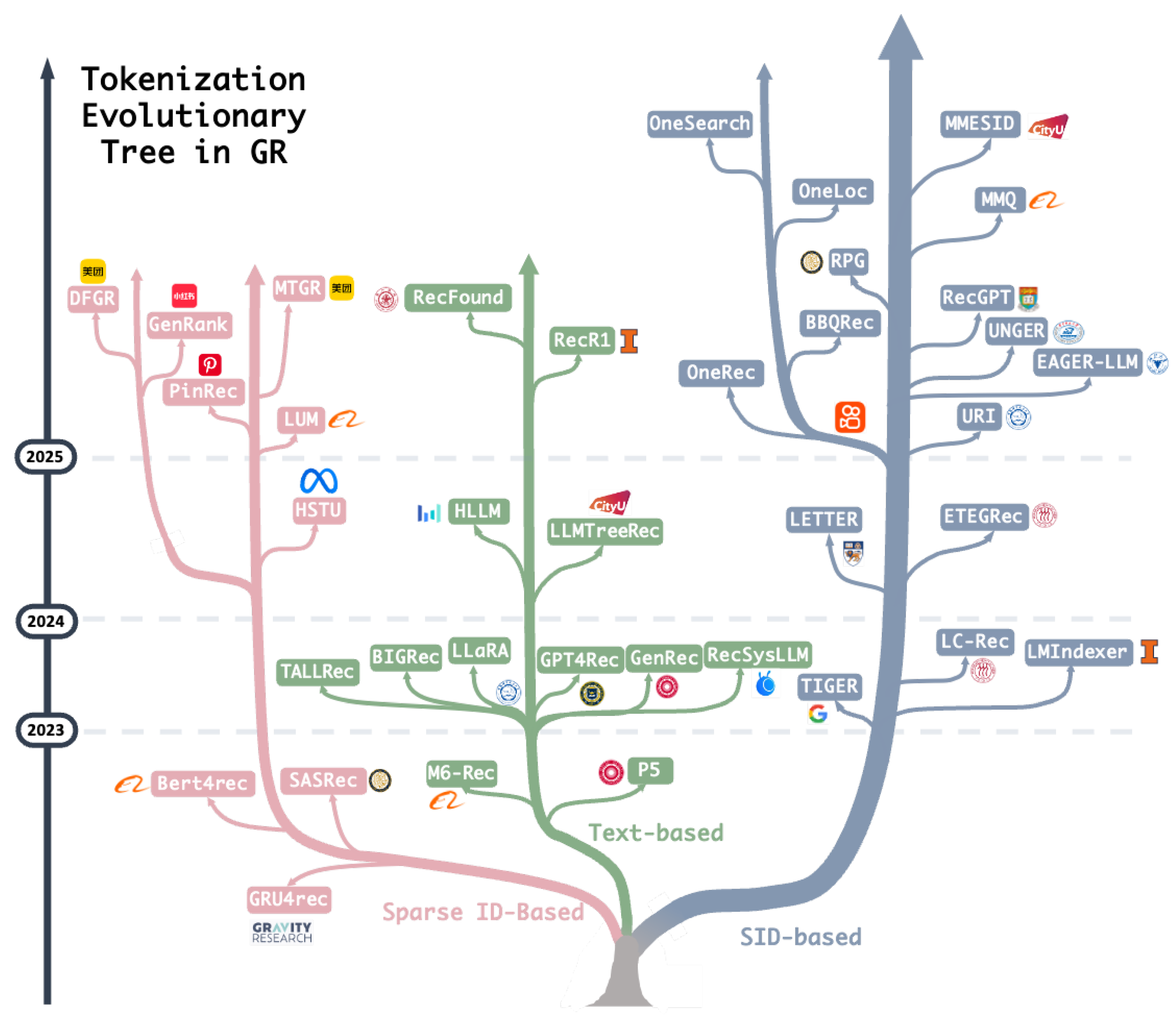

3. Tokenizer

3.1. Sparse ID-Based IDENTIFIERS

3.2. Text-Based Identifiers

3.3. SID-Based Identifiers

3.3.1. Semantic ID Construction

3.3.2. Challenges for Semantic ID

3.4. Summary

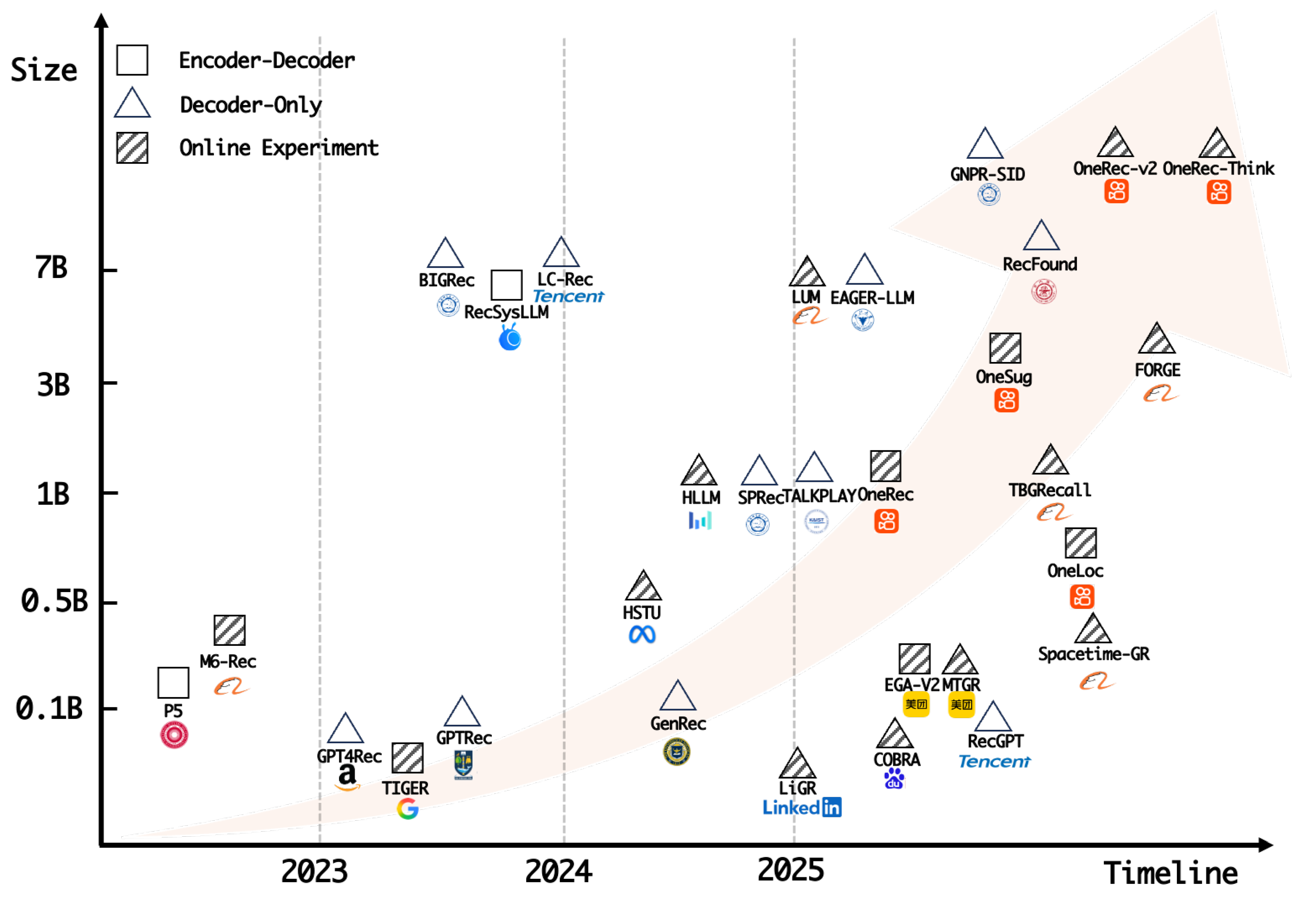

4. Model Architecture

4.1. Encoder-Decoder Architecture

4.2. Decoder-Only Architecture

4.3. Diffusion-Based Architecture

4.4. Summary

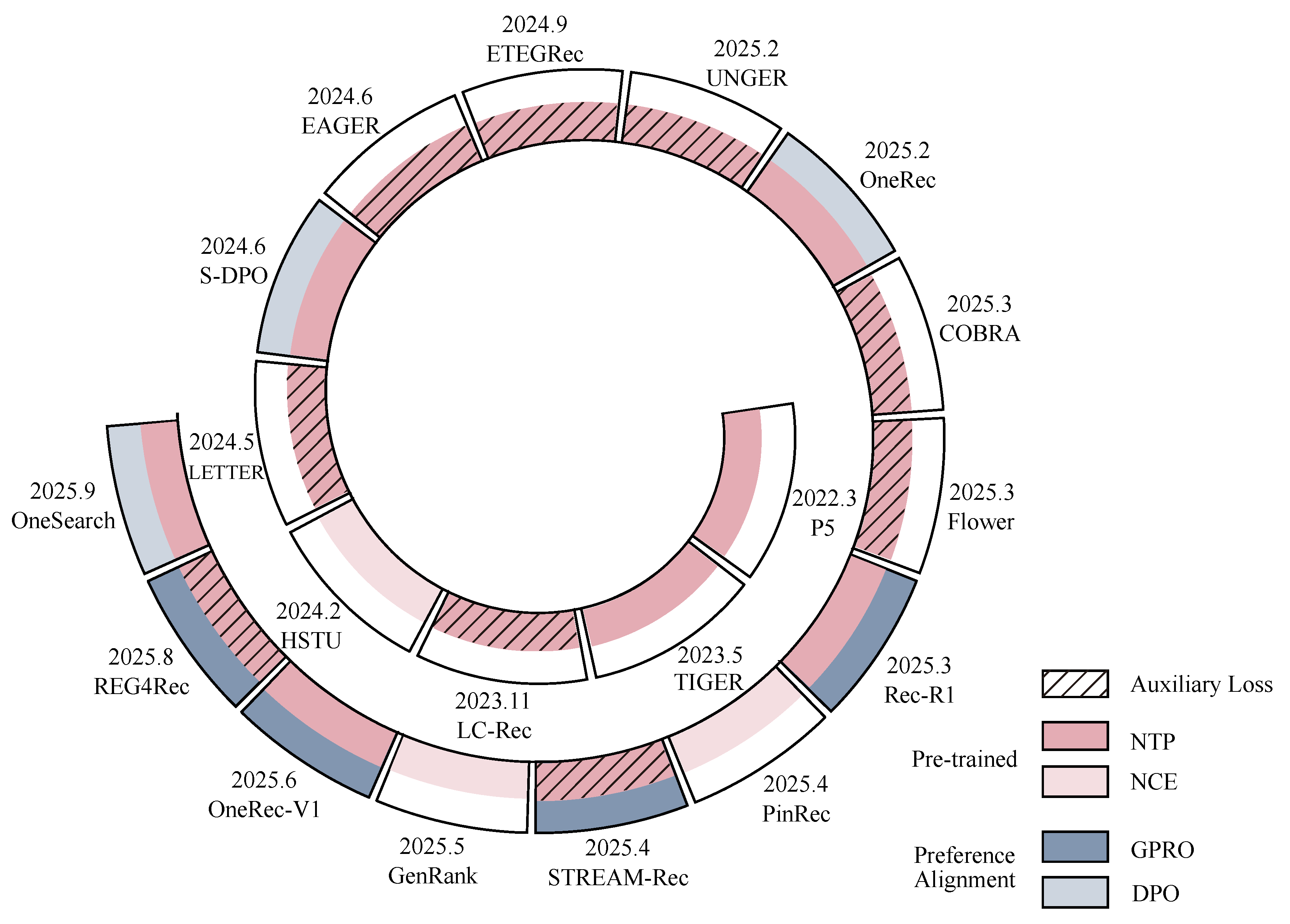

5. Optimization Strategy

5.1. Supervised Learning

5.2. Preference Alignment

5.3. Summary

6. Application

6.1. Generative Recommendation in Cascaded System

6.1.1. Retrieval

6.1.2. Rank

6.1.3. End-to-End

6.2. Generative Recommendation in Various Application Scenarios

6.2.1. Cold Start

6.2.2. Cross Domain

6.2.3. Search

6.2.4. Auto-Bidding

7. Challenges and Future Direction

7.1. End-to-End Modeling

7.2. Efficiency

7.3. Reasoning

7.4. Data Optimization

7.5. Interactive Agent

7.6. From Recommendation to Generation

8. Conclusions

References

- Schafer, J.B.; Konstan, J.A.; Riedl, J. E-commerce recommendation applications. DMKD 2001, pp. 115–153.

- Gomez-Uribe, C.A.; Hunt, N. The netflix recommender system: Algorithms, business value, and innovation. TMIS 2015, pp. 1–19.

- Song, Y.; Dixon, S.; Pearce, M. A survey of music recommendation systems and future perspectives. In Proceedings of the CMMR, 2012, pp. 395–410.

- Konstas, I.; Stathopoulos, V.; Jose, J.M. On social networks and collaborative recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2009, pp. 195–202.

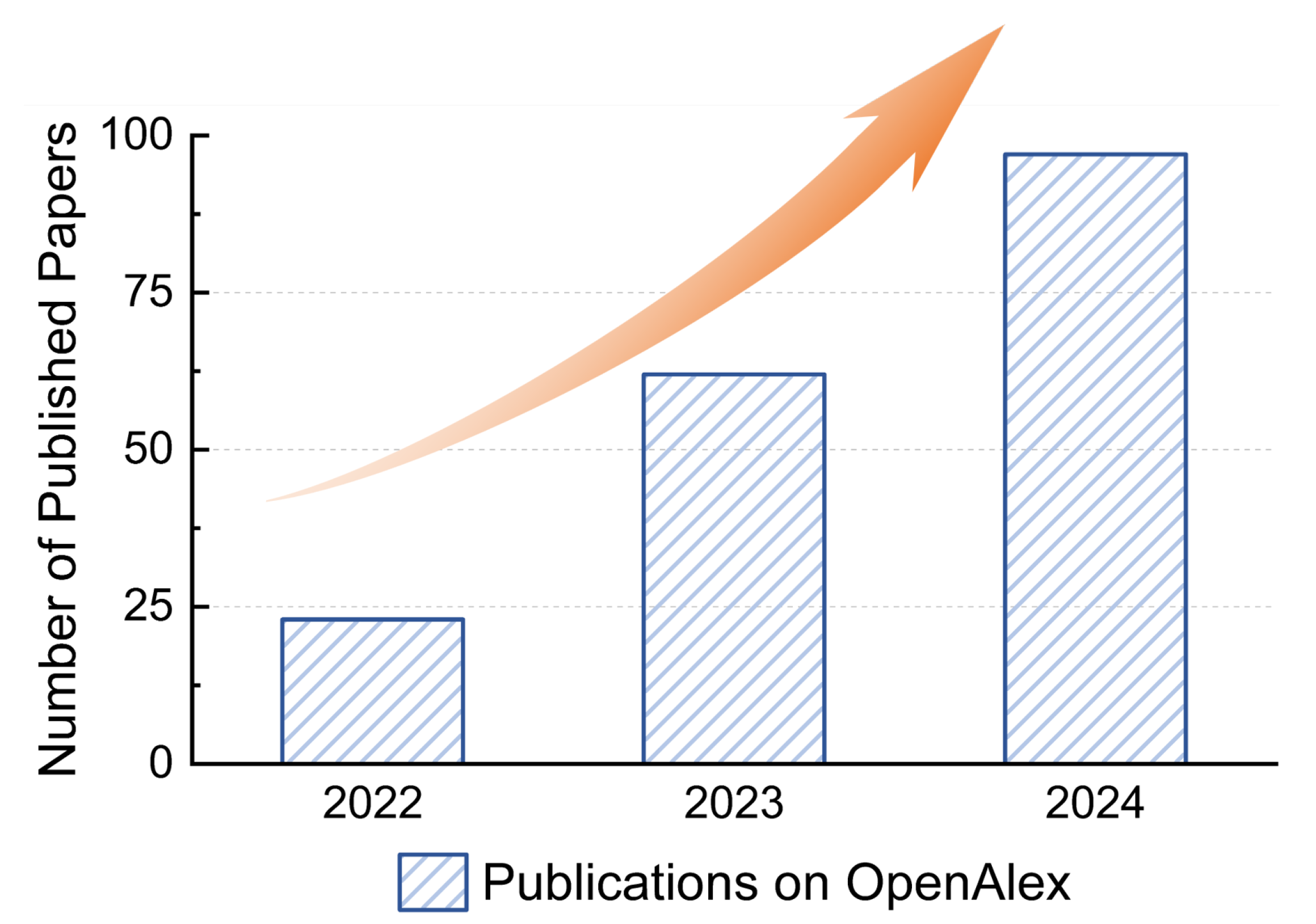

- Priem, J.; Piwowar, H.; Orr, R. OpenAlex: A fully-open index of scholarly works, authors, venues, institutions, and concepts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01833 2022.

- Guo, H.; Chen, B.; Tang, R.; Li, Z.; He, X. Autodis: Automatic discretization for embedding numerical features in CTR prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.08986 2020.

- Guo, H.; Tang, R.; Ye, Y.; Li, Z.; He, X. DeepFM: A factorization-machine based neural network for CTR prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.04247 2017.

- Wang, R.; Fu, B.; Fu, G.; Wang, M. Deep & cross network for ad click predictions. In Proc. of KDD; 2017; pp. 1–7.

- Qin, J.; Zhu, J.; Chen, B.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Tang, R.; Zhang, R.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, W. Rankflow: Joint optimization of multi-stage cascade ranking systems as flows. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2022, pp. 814–824.

- He, R.; McAuley, J. VBPR: Visual bayesian personalized ranking from implicit feedback. In Proceedings of the Proc. of AAAI, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xie, R.; Zhuang, F.; Ge, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lin, L.; Cao, J. Learning to warm up cold item embeddings for cold-start recommendation with meta scaling and shifting networks. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2021, pp. 1167–1176.

- Xu, X.; Dong, H.; Qi, L.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, H.; Xia, X.; Xu, Y.; Dou, W. Cmclrec: Cross-modal contrastive learning for user cold-start sequential recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2024, pp. 1589–1598.

- Zha, D.; Feng, L.; Bhushanam, B.; Choudhary, D.; Nie, J.; Tian, Y.; Chae, J.; Ma, Y.; Kejariwal, A.; Hu, X. Autoshard: Automated embedding table sharding for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2022, pp. 4461–4471.

- Jha, G.K.; Thomas, A.; Jain, N.; Gobriel, S.; Rosing, T.; Iyer, R. Mem-rec: Memory efficient recommendation system using alternative representation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of ACML, 2024, pp. 518–533.

- Zhou, G.; Deng, J.; Zhang, J.; Cai, K.; Ren, L.; Luo, Q.; Wang, Q.; Hu, Q.; Huang, R.; Wang, S.; et al. OneRec Technical Report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.13695 2025.

- Gupta, U.; Wu, C.J.; Wang, X.; Naumov, M.; Reagen, B.; Brooks, D.; Cottel, B.; Hazelwood, K.; Hempstead, M.; Jia, B.; et al. The architectural implications of facebook’s dnn-based personalized recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of HPCA, 2020, pp. 488–501.

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Weng, Q.; Dong, J.; Liu, K.; Zhang, C.; Zi, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; et al. {GPU-Disaggregated} Serving for Deep Learning Recommendation Models at Scale. In Proceedings of the Proc. of NSDI, 2025, pp. 847–863.

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. JMLR 2023, pp. 1–113.

- Wei, J.; Tay, Y.; Bommasani, R.; Raffel, C.; Zoph, B.; Borgeaud, S.; Yogatama, D.; et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07682 2022.

- Burges, C.; Shaked, T.; Renshaw, E.; Lazier, A.; Deeds, M.; Hamilton, N.; Hullender, G. Learning to rank using gradient descent. In Proceedings of the Proc. of ICML, 2005, pp. 89–96.

- Xu, J.; Li, H. Adarank: A boosting algorithm for information retrieval. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2007, pp. 391–398.

- Covington, P.; Adams, J.; Sargin, E. Deep neural networks for youtube recommendations. In Proceedings of the Proc. of RecSys, 2016, pp. 191–198.

- Evnine, A.; Ioannidis, S.; Kalimeris, D.; Kalyanaraman, S.; Li, W.; Nir, I.; Sun, W.; Weinsberg, U. Achieving a better tradeoff in multi-stage recommender systems through personalization. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2024, pp. 4939–4950.

- Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; et al. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12948 2025.

- OpenAI. OpenAI o3 and o4-mini System Card. Technical report, OpenAI, 2025.

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xia, L.; Luo, D.; Lin, K.; Huang, C. RecLM: Recommendation Instruction Tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.19302 2024.

- Xi, Y.; Liu, W.; Lin, J.; Cai, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, J.; Chen, B.; Tang, R.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y. Towards open-world recommendation with knowledge augmentation from large language models. In Proceedings of the Proc. of RecSys, 2024, pp. 12–22.

- Geng, S.; Liu, S.; Fu, Z.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, Y. Recommendation as language processing (rlp): A unified pretrain, personalized prompt & predict paradigm (p5). In Proceedings of the Proc. of RecSys, 2022, pp. 299–315.

- Rajput, S.; Mehta, N.; Singh, A.; Hulikal Keshavan, R.; Vu, T.; Heldt, L.; Hong, L.; Tay, Y.; Tran, V.; Samost, J.; et al. Recommender systems with generative retrieval. Proc. of NeurIPS 2023, pp. 10299–10315.

- Liu, R.; Chen, H.; Bei, Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhong, F.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Fine Tuning Out-of-Vocabulary Item Recommendation with User Sequence Imagination. Proc. of NeurIPS 2024, pp. 8930–8955.

- Hou, Y.; Mu, S.; Zhao, W.X.; Li, Y.; Ding, B.; Wen, J.R. Towards universal sequence representation learning for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2022, pp. 585–593.

- Deng, J.; Wang, S.; Cai, K.; Ren, L.; Hu, Q.; Ding, W.; Luo, Q.; Zhou, G. Onerec: Unifying retrieve and rank with generative recommender and iterative preference alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.18965 2025.

- Zhou, G.; Hu, H.; Cheng, H.; Wang, H.; Deng, J.; Zhang, J.; Cai, K.; Ren, L.; Ren, L.; Yu, L.; et al. Onerec-v2 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.20900 2025.

- Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Deng, J.; Bao, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Zheng, P.; Wu, X.; et al. OneRec-Think: In-Text Reasoning for Generative Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.11639 2025.

- Zhai, J.; Liao, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Cao, X.; Gao, L.; Gong, Z.; Gu, F.; He, M.; et al. Actions speak louder than words: Trillion-parameter sequential transducers for generative recommendations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.17152 2024.

- Zhu, J.; Fan, Z.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, H.; Han, X.; Ding, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Gong, Z.; et al. RankMixer: Scaling Up Ranking Models in Industrial Recommenders. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.15551 2025.

- Wang, W.; Bao, H.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, F.; Ng, S.K.; Chua, T.S. Learnable item tokenization for generative recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of CIKM, 2024, pp. 2400–2409.

- Chen, Y.; Tan, J.; Zhang, A.; Yang, Z.; Sheng, L.; Zhang, E.; Wang, X.; Chua, T.S. On softmax direct preference optimization for recommendation. Proc. of NeurIPS 2024, pp. 27463–27489.

- Lin, J.; Dai, X.; Xi, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, B.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, X.; Zhu, C.; et al. How can recommender systems benefit from large language models: A survey. TOIS 2025, pp. 1–47.

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Jia, P.; Chen, C.; et al. Large Language Model Enhanced Recommender Systems: A Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.13432 2024.

- Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Xing, Q.; et al. Towards next-generation llm-based recommender systems: A survey and beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.19744 2024.

- Hou, M.; Wu, L.; Liao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Wu, H.; Hong, R. A Survey on Generative Recommendation: Data, Model, and Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.27157 2025.

- Deldjoo, Y.; He, Z.; McAuley, J.; Korikov, A.; Sanner, S.; Ramisa, A.; Vidal, R.; Sathiamoorthy, M.; Kasirzadeh, A.; Milano, S. A review of modern recommender systems using generative models (gen-recsys). In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2024, pp. 6448–6458.

- Li, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, W.; Feng, F.; Pang, L.; Li, W.; Nie, L.; He, X.; Chua, T.S. A survey of generative search and recommendation in the era of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.16924 2024.

- Wei, T.R.; Fang, Y. Diffusion Models in Recommendation Systems: A Survey. arXiv arXiv:2501.10548 2025.

- Yang, Z.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Gr-llms: Recent advances in generative recommendation based on large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.06507 2025.

- Zhao, Y.; Tan, C.; Shi, L.; Zhong, Y.; Kou, F.; Zhang, P.; Chen, W.; Ma, C. Generative Recommender Systems: A Comprehensive Survey on Model, Framework, and Application. Information Fusion 2025, p. 103919. [CrossRef]

- Resnick, P.; Iacovou, N.; Suchak, M.; Bergstrom, P.; Riedl, J. Grouplens: An open architecture for collaborative filtering of netnews. In Proceedings of the CSCW, 1994, pp. 175–186.

- Sarwar, B.; Karypis, G.; Konstan, J.; Riedl, J. Item-based collaborative filtering recommendation algorithms. In Proceedings of the Proc. of WWW, 2001, pp. 285–295.

- Koren, Y.; Bell, R.; Volinsky, C. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer 2009, pp. 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. An introduction to matrix factorization and factorization machines in recommendation system, and beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.11026 2022.

- Zhou, G.; Zhu, X.; Song, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, H.; Ma, X.; Yan, Y.; Jin, J.; Li, H.; Gai, K. Deep interest network for click-through rate prediction. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2018, pp. 1059–1068.

- Ma, J.; Zhao, Z.; Yi, X.; Chen, J.; Hong, L.; Chi, E.H. Modeling task relationships in multi-task learning with multi-gate mixture-of-experts. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2018, pp. 1930–1939.

- Sheng, X.R.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, G.; Ding, X.; Dai, B.; Luo, Q.; Yang, S.; Lv, J.; Zhang, C.; Deng, H.; et al. One model to serve all: Star topology adaptive recommender for multi-domain ctr prediction. In Proceedings of the Proc. of CIKM, 2021, pp. 4104–4113.

- Wang, B.; Liu, F.; Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Lou, X.; Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; Chen, C.; et al. LLM4DSR: Leveraging Large Language Model for Denoising Sequential Recommendation. TOIS 2025, pp. 1–32.

- Huang, F.; Bei, Y.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Chen, H.; Shen, Q.; Wang, S.; Karray, F.; Yu, P.S. Large Language Model Simulator for Cold-Start Recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of WSDM, 2025, pp. 261–270.

- Li, X.; Chen, B.; Hou, L.; Tang, R. Ctrl: Connect tabular and language model for ctr prediction. CoRR 2023.

- Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Tian, F.; Zheng, Y. Llmemb: Large language model can be a good embedding generator for sequential recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of AAAI, 2025, pp. 12183–12191. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.; Xiong, G.; Lu, A.; Medioni, G. GPT4Rec: A generative framework for personalized recommendation and user interests interpretation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.03879 2023.

- Jiang, Y.; Ren, X.; Xia, L.; Luo, D.; Lin, K.; Huang, C. RecGPT: A Foundation Model for Sequential Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.06270 2025.

- Ngo, H.; Nguyen, D.Q. Recgpt: Generative pre-training for text-based recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.12715 2024.

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cao, X.; Yang, R.; Qi, M.; Zhu, Y.; Han, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yao, X.; et al. Towards Large-scale Generative Ranking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.04180 2025.

- Chen, B.; Guo, X.; Wang, S.; Liang, Z.; Lv, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, X.; Xue, B.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Onesearch: A preliminary exploration of the unified end-to-end generative framework for e-commerce search. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.03236 2025.

- Kong, X.; Jiang, J.; Liu, B.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Xu, J.; Zheng, B.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. Think before Recommendation: Autonomous Reasoning-enhanced Recommender. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.23077 2025.

- Han, R.; Yin, B.; Chen, S.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, F.; Li, X.; Ma, C.; Huang, M.; Li, X.; Jing, C.; et al. MTGR: Industrial-Scale Generative Recommendation Framework in Meituan. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.18654 2025.

- Badrinath, A.; Agarwal, P.; Bhasin, L.; Yang, J.; Xu, J.; Rosenberg, C. PinRec: Outcome-Conditioned, Multi-Token Generative Retrieval for Industry-Scale Recommendation Systems. arXiv arXiv:2504.10507 2025.

- Yan, B.; Liu, S.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Su, W.; et al. Unlocking Scaling Law in Industrial Recommendation Systems with a Three-step Paradigm based Large User Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.08309 2025.

- Guo, H.; Xue, E.; Huang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. Action is All You Need: Dual-Flow Generative Ranking Network for Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.16752 2025.

- Cui, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J.; Yang, H. M6-rec: Generative pretrained language models are open-ended recommender systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.08084 2022.

- Zhang, W.; Wu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, K.; Wang, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhao, X.; Guo, H.; Tang, R. Llmtreerec: Unleashing the power of large language models for cold-start recommendations. In Proceedings of the Proc. of COLING, 2025, pp. 886–896.

- Bao, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Feng, F.; He, X. Tallrec: An effective and efficient tuning framework to align large language model with recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of RecSys, 2023, pp. 1007–1014.

- Bao, K.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Chen, C.; Feng, F.; Tian, Q. A bi-step grounding paradigm for large language models in recommendation systems. TORS 2025, pp. 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Karra, S.R.; Tulabandhula, T. Interarec: Interactive recommendations using multimodal large language models. In Proceedings of the Proc. of PAKDD, 2024, pp. 32–43.

- Chu, Z.; Hao, H.; Ouyang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Gu, J.; Cui, Q.; Li, L.; Xue, S.; et al. Leveraging large language models for pre-trained recommender systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.10837 2023.

- Liao, J.; Li, S.; Yang, Z.; Wu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X.; He, X. Llara: Large language-recommendation assistant. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2024, pp. 1785–1795.

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, p. 3.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proc. of NAACL, 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the Proc. of ICML, 2021, pp. 8748–8763.

- Mentzer, F.; Minnen, D.; Agustsson, E.; Tschannen, M. Finite scalar quantization: Vq-vae made simple. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.15505 2023.

- Lee, D.; Kim, C.; Kim, S.; Cho, M.; Han, W.S. Autoregressive image generation using residual quantization. In Proceedings of the Proc. of CVPR, 2022, pp. 11523–11532.

- Jegou, H.; Douze, M.; Schmid, C. Product quantization for nearest neighbor search. IEEE PAMI 2010, pp. 117–128. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Hou, Y.; Lu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, W.X.; Chen, M.; Wen, J.R. Adapting large language models by integrating collaborative semantics for recommendation. In Proceedings of the ICDE, 2024, pp. 1435–1448.

- Wang, Y.; Xun, J.; Hong, M.; Zhu, J.; Jin, T.; Lin, W.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Eager: Two-stream generative recommender with behavior-semantic collaboration. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2024, pp. 3245–3254.

- Xiao, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Ji, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, R.; Li, R. UNGER: Generative Recommendation with A Unified Code via Semantic and Collaborative Integration. TOIS 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Cai, K.; She, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Zeng, Y.; Luo, Q.; Zeng, W.; Tang, R.; Gai, K.; et al. OneLoc: Geo-Aware Generative Recommender Systems for Local Life Service. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.14646 2025.

- Wang, D.; Huang, Y.; Gao, S.; Wang, Y.; Huang, C.; Shang, S. Generative Next POI Recommendation with Semantic ID. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2025, pp. 2904–2914.

- Qu, H.; Fan, W.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Q. Tokenrec: Learning to tokenize id for llm-based generative recommendations. IEEE TKDE 2025. [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, F.; Gori, M.; Tsoi, A.C.; Hagenbuchner, M.; Monfardini, G. The graph neural network model. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2008.

- Yang, Y.; Ji, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Mo, Z.; Ding, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Li, S.; et al. Sparse meets dense: Unified generative recommendations with cascaded sparse-dense representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.02453 2025.

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Lu, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, F.; Wang, P.; Xu, J.; Zheng, B.; et al. GFlowGR: Fine-tuning Generative Recommendation Frameworks with Generative Flow Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.16114 2025.

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Sun, W.; Lu, H.; Zhao, W.X.; Chen, Y.; Wen, J.R. Slow Thinking for Sequential Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.09627 2025.

- Lin, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Du, C.; Feng, F.; Ng, S.K.; Chua, T.S. Efficient inference for large language model-based generative recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.05165 2024.

- Ding, Y.; Hou, Y.; Li, J.; McAuley, J. Inductive generative recommendation via retrieval-based speculation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.02939 2024.

- Zhou, S.; Gan, W.; Liu, Q.; Lei, K.; Zhu, J.; Huang, H.; Xia, Y.; Tang, R.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, Z. RecBase: Generative Foundation Model Pretraining for Zero-Shot Recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of EMNLP, 2025, pp. 15598–15610.

- Yin, X.; Chen, S.; Hu, E. Regularized soft K-means for discriminant analysis. Neurocomputing 2013, pp. 29–42. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, R.; Lian, D.; Chen, E. Breaking determinism: Fuzzy modeling of sequential recommendation using discrete state space diffusion model. Proc. of NeurIPS 2024, pp. 22720–22744.

- Hou, Y.; Li, J.; Shin, A.; Jeon, J.; Santhanam, A.; Shao, W.; Hassani, K.; Yao, N.; McAuley, J. Generating long semantic ids in parallel for recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2025, pp. 956–966.

- Jin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, F.; He, X. Generative Multi-Target Cross-Domain Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.12871 2025.

- Wang, Y.; Gan, W.; Xiao, L.; Zhu, J.; Chang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Dong, Z.; Tang, R.; Li, R. Act-With-Think: Chunk Auto-Regressive Modeling for Generative Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.23643 2025.

- Yao, Y.; Li, Z.; Xiao, S.; Du, B.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, J.; Kong, X.; Jiang, Y. SaviorRec: Semantic-Behavior Alignment for Cold-Start Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.01375 2025.

- Cuturi, M. Sinkhorn distances: Lightspeed computation of optimal transport. Proc. of NeurIPS 2013.

- Jin, B.; Zeng, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, X.; Wei, T.; Li, R.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Lu, H.; et al. Language models as semantic indexers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07815 2023.

- Li, W.; Zheng, K.; Lian, D.; Liu, Q.; Bao, W.; Yu, Y.E.; Song, Y.; Li, H.; Gai, K. Making Transformer Decoders Better Differentiable Indexers. In Proceedings of the Proc. of ICLR, 2025.

- Liu, E.; Zheng, B.; Ling, C.; Hu, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, W.X. Generative recommender with end-to-end learnable item tokenization. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2025, pp. 729–739.

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Liao, Z.; Xing, H.; Deng, H.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, J. MMQ: Multimodal Mixture-of-Quantization Tokenization for Semantic ID Generation and User Behavioral Adaptation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.15281 2025.

- Luo, X.; Cao, J.; Sun, T.; Yu, J.; Huang, R.; Yuan, W.; Lin, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, Q.; et al. Qarm: Quantitative alignment multi-modal recommendation at kuaishou. In Proceedings of the Proc. of CIKM, 2025, pp. 5915–5922.

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, F.; Fan, J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Ega-v2: An end-to-end generative framework for industrial advertising. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.17549 2025.

- Wang, Y.; Pan, J.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, X. Empowering Large Language Model for Sequential Recommendation via Multimodal Embeddings and Semantic IDs. In Proceedings of the Proc. of CIKM, 2025, pp. 3209–3219.

- Li, K.; Xiang, R.; Bai, Y.; Tang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, P.; Gai, K. Bbqrec: Behavior-bind quantization for multi-modal sequential recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.06636 2025.

- Doh, S.; Choi, K.; Nam, J. TALKPLAY: Multimodal Music Recommendation with Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13713 2025.

- Hong, M.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, S.; Yang, X.; Dai, Q.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; et al. EAGER-LLM: Enhancing Large Language Models as Recommenders through Exogenous Behavior-Semantic Integration. In Proceedings of the WWW, 2025, pp. 2754–2762.

- He, R.; Heldt, L.; Hong, L.; Keshavan, R.; Mao, S.; Mehta, N.; Su, Z.; Tsai, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.C.; et al. PLUM: Adapting Pre-trained Language Models for Industrial-scale Generative Recommendations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.07784 2025.

- Guo, H.; Chen, B.; Tang, R.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; He, X. An embedding learning framework for numerical features in ctr prediction. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2021, pp. 2910–2918.

- Lian, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Z.; Xie, X.; Sun, G. xdeepfm: Combining explicit and implicit feature interactions for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2018, pp. 1754–1763.

- Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Li, K.; Han, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhu, W. Diff4rec: Sequential recommendation with curriculum-scheduled diffusion augmentation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of ACM MM, 2023, pp. 9329–9335.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. JMLR 2020, pp. 1–67.

- Lin, J.; Men, R.; Yang, A.; Zhou, C.; Ding, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, A.; Jiang, L.; Jia, X.; et al. M6: A chinese multimodal pretrainer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.00823 2021.

- Du, Z.; Qian, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, M.; Qiu, J.; Yang, Z.; Tang, J. Glm: General language model pretraining with autoregressive blank infilling. In Proceedings of the Proc. of ACL, 2022, pp. 320–335.

- Guo, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Lei, C.; Ding, Y.; Li, H. OneSug: The Unified End-to-End Generative Framework for E-commerce Query Suggestion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.06913 2025.

- Liu, A.; Feng, B.; Xue, B.; Wang, B.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Zhao, C.; Deng, C.; Zhang, C.; Ruan, C.; et al. Deepseek-v3 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.19437 2024.

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.16609 2023.

- Ji, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Hua, W.; Ge, Y.; Tan, J.; Zhang, Y. Genrec: Large language model for generative recommendation. In Proceedings of the ECIR, 2024, pp. 494–502.

- Lin, J.; Wang, T.; Qian, K. Rec-r1: Bridging generative large language models and user-centric recommendation systems via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.24289 2025.

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, C.; Lin, J.; Chen, B.; Tang, R.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y. Generative Representational Learning of Foundation Models for Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.11999 2025.

- Luo, S.; Yao, Y.; He, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhan, M.; Song, L. Integrating large language models into recommendation via mutual augmentation and adaptive aggregation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.13870 2024.

- Lin, H.; Yang, Z.; Xue, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Gu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, X. Spacetime-GR: A Spacetime-Aware Generative Model for Large Scale Online POI Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.16126 2025.

- Fu, K.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; et al. FORGE: Forming Semantic Identifiers for Generative Retrieval in Industrial Datasets. arXiv arXiv:2509.20904 2025.

- Gao, V.R.; Xue, C.; Versage, M.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Seonwoo, Y.; Chen, N.; Ge, Z.; Kundu, G.; et al. SynerGen: Contextualized Generative Recommender for Unified Search and Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.21777 2025.

- Zheng, B.; Liu, E.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, W.X.; Wen, J.R. Pre-training Generative Recommender with Multi-Identifier Item Tokenization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.04400 2025.

- Yan, H.; Xu, L.; Sun, J.; Ou, N.; Luo, W.; Tan, X.; Cheng, R.; Liu, K.; Chu, X. IntSR: An Integrated Generative Framework for Search and Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.21179 2025.

- Borisyuk, F.; Hertel, L.; Parameswaran, G.; Srivastava, G.; Ramanujam, S.S.; Ocejo, B.; Du, P.; Akterskii, A.; Daftary, N.; Tang, S.; et al. From Features to Transformers: Redefining Ranking for Scalable Impact. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.03417 2025.

- Cui, Z.; Wu, H.; He, B.; Cheng, J.; Ma, C. Diffusion-based Contrastive Learning for Sequential Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.09369 2024.

- Li, Z.; Xia, L.; Huang, C. Recdiff: Diffusion model for social recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of CIKM, 2024, pp. 1346–1355.

- Zhao, J.; Wenjie, W.; Xu, Y.; Sun, T.; Feng, F.; Chua, T.S. Denoising diffusion recommender model. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2024, pp. 1370–1379.

- Song, Q.; Hu, J.; Xiao, L.; Sun, B.; Gao, X.; Li, S. Diffcl: A diffusion-based contrastive learning framework with semantic alignment for multimodal recommendations. IEEE TNNLS 2025. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, R.; Zhao, H.; Liu, C.; Zheng, K.; Liu, Q.; et al. DimeRec: A unified framework for enhanced sequential recommendation via generative diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proc. of WSDM, 2025, pp. 726–734.

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tang, G.; Huang, R.; Luo, Q.; Lv, X.; Tang, R.; Gai, K.; Zhou, G. DiffGRM: Diffusion-based Generative Recommendation Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.21805 2025.

- Xie, Y.; Ren, X.; Qi, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shan, L. RecLLM-R1: A Two-Stage Training Paradigm with Reinforcement Learning and Chain-of-Thought v1. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.19235 2025.

- Xing, H.; Deng, H.; Mao, Y.; Hu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, X.; et al. REG4Rec: Reasoning-Enhanced Generative Model for Large-Scale Recommendation Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.15308 2025.

- Huang, L.; Guo, H.; Peng, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, D.; et al. SessionRec: Next Session Prediction Paradigm For Generative Sequential Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.10157 2025.

- Afsar, M.M.; Crump, T.; Far, B. Reinforcement learning based recommender systems: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, pp. 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Dai, S.; Yu, W.; Xu, J. Reinforcing Long-Term Performance in Recommender Systems with User-Oriented Exploration Policy. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2024, pp. 1850–1860.

- Sharma, A.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Jiao, J. Optimizing novelty of top-k recommendations using large language models and reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2024, pp. 5669–5679.

- Rafailov, R.; Sharma, A.; Mitchell, E.; Manning, C.D.; Ermon, S.; Finn, C. Direct preference optimization: Your language model is secretly a reward model. Proc. of NeurIPS 2023, pp. 53728–53741.

- Shao, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, R.; Song, J.; Bi, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of mathematical reasoning in open language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03300 2024.

- Liao, J.; He, X.; Xie, R.; Wu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, X.; Kang, Z.; Wang, X. Rosepo: Aligning llm-based recommenders with human values. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.12519 2024.

- Gao, C.; Chen, R.; Yuan, S.; Huang, K.; Yu, Y.; He, X. SPRec: Leveraging self-play to debias preference alignment for large language model-based recommendations. arXiv e-prints 2024, pp. arXiv–2412.

- Chen, S.; Chen, B.; Yu, C.; Luo, Y.; Yi, O.; Cheng, L.; Zhuo, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y. VRAgent-R1: Boosting Video Recommendation with MLLM-based Agents via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv arXiv:2507.02626 2025.

- Huang, P.S.; He, X.; Gao, J.; Deng, L.; Acero, A.; Heck, L. Learning deep structured semantic models for web search using clickthrough data. In Proceedings of the Proc. of CIKM, 2013, pp. 2333–2338.

- Liang, Z.; Wu, C.; Huang, D.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Chen, K.; et al. Tbgrecall: A generative retrieval model for e-commerce recommendation scenarios. arXiv arXiv:2508.11977 2025.

- Liu, C.; Cao, J.; Huang, R.; Zheng, K.; Luo, Q.; Gai, K.; Zhou, G. KuaiFormer: Transformer-Based Retrieval at Kuaishou. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10057 2024.

- Chen, J.; Chi, L.; Peng, B.; Yuan, Z. Hllm: Enhancing sequential recommendations via hierarchical large language models for item and user modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.12740 2024.

- Coburn, J.; Tang, C.; Asal, S.A.; Agrawal, N.; Chinta, R.; Dixit, H.; Dodds, B.; Dwarakapuram, S.; Firoozshahian, A.; Gao, C.; et al. Meta’s Second Generation AI Chip: Model-Chip Co-Design and Productionization Experiences. In Proceedings of the Proc. of ISCA, 2025, pp. 1689–1702.

- Xi, Y.; Liu, W.; Dai, X.; Tang, R.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; He, X.; Yu, Y. Context-aware reranking with utility maximization for recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.09059 2021.

- Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Hu, L.; Li, H.; Cao, Q.; Sun, F.; Gai, K. GoalRank: Group-Relative Optimization for a Large Ranking Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.22046 2025.

- Meng, Y.; Guo, C.; Cao, Y.; Liu, T.; Zheng, B. A generative re-ranking model for list-level multi-objective optimization at taobao. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2025, pp. 4213–4218.

- Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Huang, Z.; Li, D.; Yang, D.; Lu, X. Kc-genre: A knowledge-constrained generative re-ranking method based on large language models for knowledge graph completion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.17532 2024.

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Z.; Lu, H.; Xie, R.; McAuley, J.; Zhao, W.X. Large language models are zero-shot rankers for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the ECIR, 2024, pp. 364–381.

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Yu, J.; Cai, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, H.; Hu, L.; et al. M3oe: Multi-domain multi-task mixture-of experts recommendation framework. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2024, pp. 893–902.

- Chang, J.; Zhang, C.; Hui, Y.; Leng, D.; et al. Pepnet: Parameter and embedding personalized network for infusing with personalized prior information. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2023, pp. 3795–3804.

- Li, X.; Yan, F.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Guo, H.; Tang, R. Hamur: Hyper adapter for multi-domain recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of CIKM, 2023, pp. 1268–1277.

- Hu, P.; Lu, W.; Wang, J. From IDs to Semantics: A Generative Framework for Cross-Domain Recommendation with Adaptive Semantic Tokenization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.08006 2025.

- Pang, M.; Yuan, C.; He, X.; Fang, Z.; Xie, D.; Qu, F.; Jiang, X.; Peng, C.; Lin, Z.; Luo, Z.; et al. Generative Retrieval and Alignment Model: A New Paradigm for E-commerce Retrieval. In Proceedings of the WWW, 2025, pp. 413–421.

- Shi, T.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zang, X.; Zheng, K.; Song, Y.; Yu, E. Unified Generative Search and Recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.05730 2025.

- Chen, Y.; Berkhin, P.; Anderson, B.; Devanur, N.R. Real-time bidding algorithms for performance-based display ad allocation. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2011, pp. 1307–1315.

- Fujimoto, S.; Meger, D.; Precup, D. Off-policy deep reinforcement learning without exploration. In Proceedings of the Proc. of ICML, 2019, pp. 2052–2062.

- Guo, J.; Huo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Yu, C.; Xu, J.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y. Generative auto-bidding via conditional diffusion modeling. In Proceedings of the Proc. of KDD, 2024, pp. 5038–5049.

- Li, Y.; Mao, S.; Gao, J.; Jiang, N.; Xu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Pan, F.; Jiang, P.; An, B. GAS: Generative Auto-bidding with Post-training Search. In Proceedings of the WWW, 2025, pp. 315–324.

- Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Mao, S.; Jiang, P.; Jiang, N.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Q.; Pan, F.; Jiang, P.; Gai, K.; et al. Generative auto-bidding with value-guided explorations. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2025, pp. 244–254.

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361 2020.

- Li, J.; Xu, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Lian, Y.; Pan, J.; et al. Large language model inference acceleration: A comprehensive hardware perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.04466 2024.

- Miao, X.; Oliaro, G.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Jin, H.; Chen, T.; Jia, Z. Towards efficient generative large language model serving: A survey from algorithms to systems. ACM Computing Surveys 2025, pp. 1–37. [CrossRef]

- Catania, F.; Spitale, M.; Garzotto, F. Conversational agents in therapeutic interventions for neurodevelopmental disorders: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, pp. 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Shan, R.; Zhu, C.; Du, K.; Chen, B.; Quan, S.; Tang, R.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, W. Rella: Retrieval-enhanced large language models for lifelong sequential behavior comprehension in recommendation. In Proceedings of the WWW, 2024, pp. 3497–3508.

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Lai, Y.; Dong, X.; Fan, L.; Bian, Z.; Dong, Z.; Wu, X.M. Evaluating recabilities of foundation models: A multi-domain, multi-dataset benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.21354 2025.

- Zhang, Y.; Qiao, S.; Zhang, J.; Lin, T.H.; Gao, C.; Li, Y. A survey of large language model empowered agents for recommendation and search: Towards next-generation information retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.05659 2025.

- Zhu, Y.; Steck, H.; Liang, D.; He, Y.; Kallus, N.; Li, J. LLM-based Conversational Recommendation Agents with Collaborative Verbalized Experience. In Proceedings of the Proc. of EMNLP Findings, 2025, pp. 2207–2220.

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Tang, W.; Wang, D.; De Rijke, M. Let me do it for you: Towards llm empowered recommendation via tool learning. In Proceedings of the Proc. of SIGIR, 2024, pp. 1796–1806.

- Kuaishou Technology. Kuaishou Unveils Proprietary Video Generation Model “Kling”, 2024.

- OpenAI. Sora: Creating video from text, 2024.

| Universality | Semantics | Vocabulary | Item Grounding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sparse ID | × | × | Large | ✓ |

| Text | ✓ | ✓ | Moderate | × |

| Semantic ID | × | ✓ | Moderate | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).