1. Introduction

The advent of LLMs has initiated a paradigm shift in recommender systems (RSs), transitioning from traditional modular pipelines toward more unified, language native systems. Classical RS architectures typically consist of separate candidate generation, multi-stage ranking, and re ranking components, often relying on pointwise or pairwise supervised learning objectives [

15]. While effective in specific domains, these systems struggle to generalize across diverse objectives such as diversity, novelty, serendipity, and fairness due to rigid model designs and hand crafted features [

13,

55].

LLMs offer a compelling alternative: instruction driven recommendation, where natural language prompts encode task intent, constraints, and personalization cues directly into the input [

35]. Recent work has demonstrated the feasibility of leveraging general purpose LLMs such as GPT-4 [

41], Claude [

24], and LLaMA [

53] for recommendation tasks through prompt based methods, with applications spanning product recommendation [

8], news personalization, conversational agents, and multi turn user modeling. These LLM native systems enable zero shot and few shot reasoning over heterogeneous content modalities and provide a unified interface for user item interaction modeling [

38,

46].

However, while LLMs are capable of generating high quality recommendations, the quality and behavior of these outputs are highly sensitive to the design of the prompts themselves [

57]. Prompt engineering defined as the construction of input instructions that steer model behavior has thus emerged as a critical component in aligning LLM outputs with specific recommendation goals. Unlike traditional RSs, which embed objectives in loss functions and training signals, LLM based RSs rely on language prompts to express goals such as “Recommend diverse items”, “Include underrepresented sellers”, or “Suggest items the user hasn’t seen before”. This shift calls for a deeper understanding of how prompt formulations affect model behavior across various ranking objectives.

Despite a growing body of empirical studies on prompt tuning, instruction optimization, and LLM reranking, there is no comprehensive survey that consolidates prompt engineering techniques specific to recommender systems, particularly under multi objective optimization settings. This paper addresses that gap by providing a structured taxonomy of prompt types, mapping them to recommendation sub tasks, and evaluating how different prompt strategies align with complex ranking objectives such as relevance, diversity, novelty, serendipity, and fairness.

We further explore emerging evaluation methodologies including instruction following benchmarks, prompt sensitivity analysis, and LLM as a judge frameworks to assess the effectiveness and faithfulness of prompts in aligning model outputs with user centric goals. Our objective is to bridge the gap between LLM capabilities and RS requirements, and to provide actionable insights for researchers and practitioners designing prompt based recommendation systems.

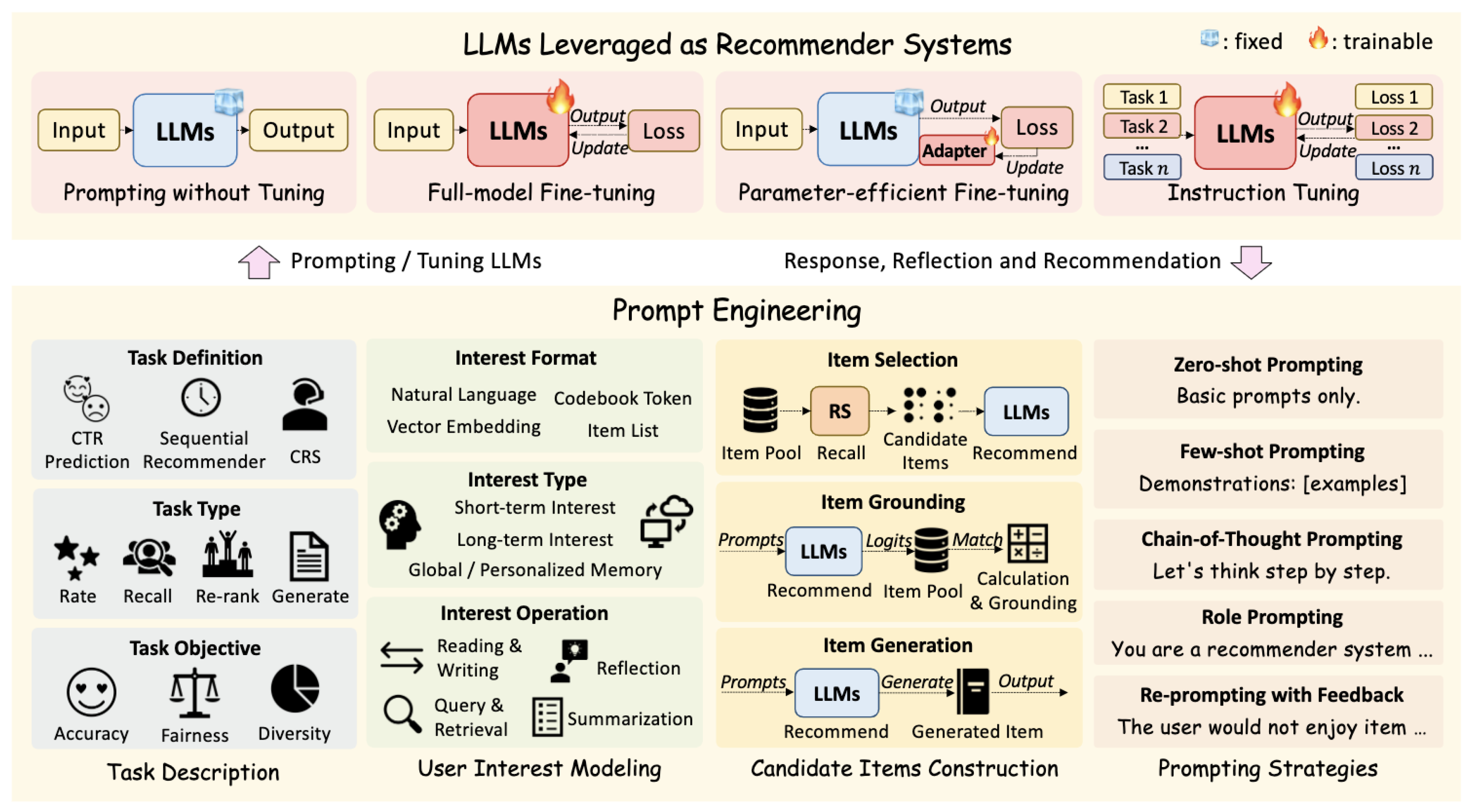

Figure 1.

Overview of LLM based recommendation using prompt engineering, illustrating task description, user interest modeling, candidate construction, and prompting strategies for goal aligned recommendations [

65].

Figure 1.

Overview of LLM based recommendation using prompt engineering, illustrating task description, user interest modeling, candidate construction, and prompting strategies for goal aligned recommendations [

65].

2. Background and Related Works

The integration of LLMs into recommender systems represents a convergence of two previously distinct research domains. In this section, we review foundational work in traditional recommendation systems, recent developments in LLM powered recommendation, and the emerging field of prompt engineering and instruction tuning.

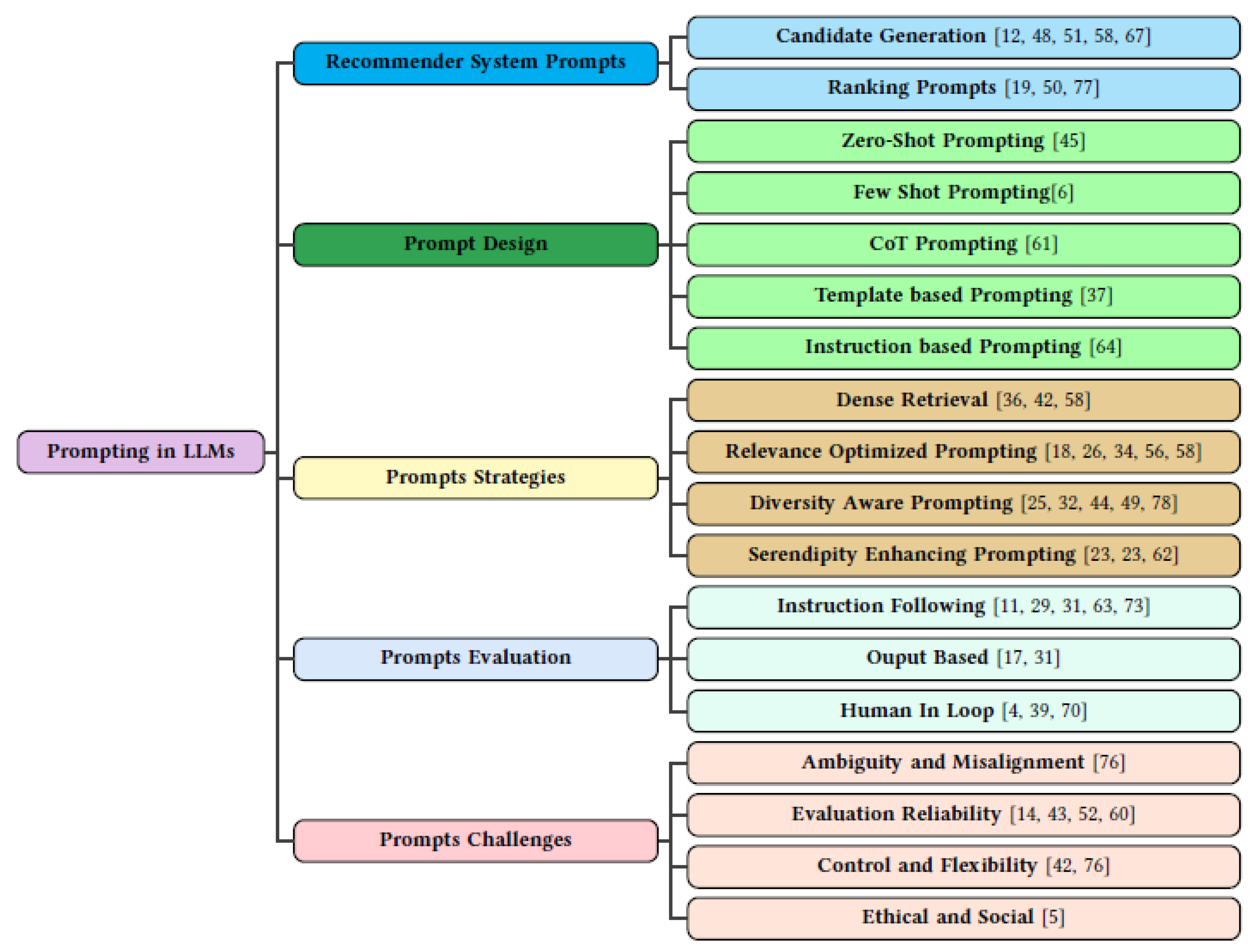

Figure 2.

A hierarchical taxonomy of prompt engineering strategies in LLM based recommender systems, covering design paradigms, use cases, evaluation methods, and associated challenges.

Figure 2.

A hierarchical taxonomy of prompt engineering strategies in LLM based recommender systems, covering design paradigms, use cases, evaluation methods, and associated challenges.

2.1. Traditional Recommender Systems

Traditional recommender systems are typically structured as multi stage pipelines comprising candidate generation, ranking, and re ranking components [

9,

47]. These models are trained using supervised learning objectives such as pointwise regression, pairwise ranking, or listwise loss [

1]. Although highly effective in modeling user item interactions, these pipelines often require task specific architectures, hand engineered features, and complex offline retraining procedures to accommodate new objectives such as diversity [

54], fairness [

3], or novelty [

74].

2.2. LLMs for Recommender Systems

With the advent of powerful foundation models like GPT-4 [

41], LLaMA [

53], and Claude [

24], researchers have begun exploring the use of LLMs for recommendation tasks [

35,

68]. These models enable zero shot and few shot reasoning over textual item descriptions, user profiles, and contextual signals. Applications include conversational recommendation [

28], multi turn interaction modeling [

30], and open domain personalization. LLMs provide a flexible interface to handle heterogeneous modalities and instruction driven behavior, eliminating the need for rigid task specific architectures.

However, these systems exhibit high sensitivity to prompt formulations and lack transparency in how prompt instructions influence recommendation behavior [

17,

57]. This sensitivity motivates a closer examination of prompt engineering techniques for robust and goal aligned output generation.

2.3. Prompt Engineering and Instruction Tuning

Prompt engineering refers to the design of input instructions that steer LLM behavior without altering model parameters [

6,

61]. This includes zero shot prompts, few shot exemplars, chain-of-thought reasoning [

59], and dynamic prompt adaptation [

11]. Prompt tuning, soft prompts [

34], and retrieval augmented prompting [

26] have further extended this paradigm by introducing trainable components for instruction optimization.

In the context of ranking, recent work such as PromptBench [

22] and JudgeRec [

72] highlights the need for prompt evaluation frameworks that assess instruction adherence, robustness, and goal satisfaction. PromptAgent [

58] and ActivePrompt [

2] propose prompt generation and selection methods optimized for downstream performance on recommendation related tasks.

Our work builds on these foundations by offering a structured taxonomy of prompting paradigms across the recommendation stack, and aligning them with multi objective ranking goals such as relevance, diversity, novelty, serendipity, and fairness. To our knowledge, this is the first survey that systematically maps prompt types to recommender system components and objectives, while also reviewing evaluation techniques tailored for prompt driven personalization.

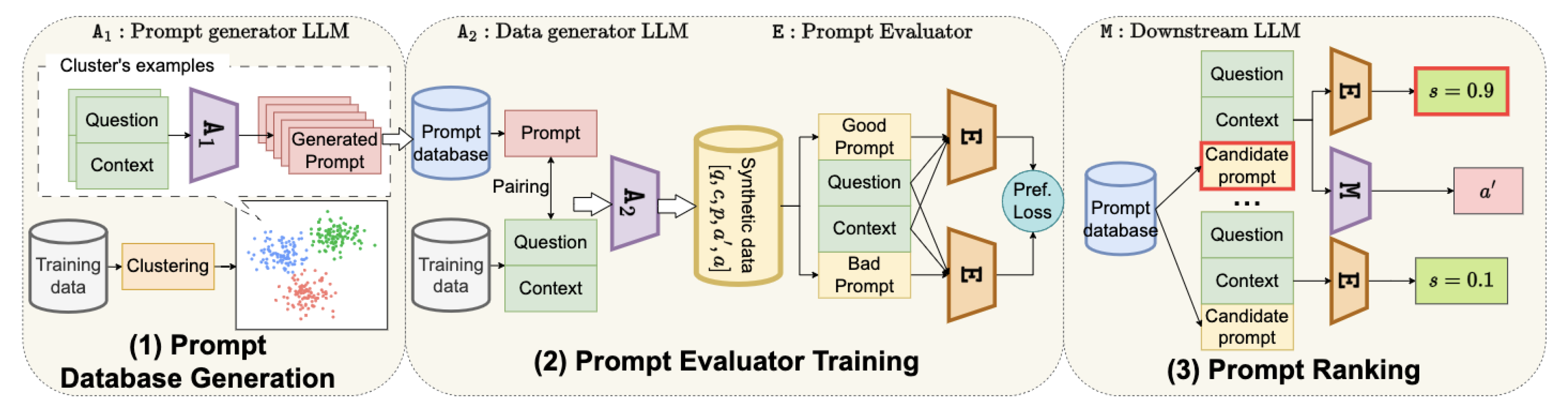

3. Prompting Paradigms Across Recommender System Components

Prompt engineering plays a pivotal role in aligning the behavior of LLMs with the diverse objectives of RSs. Unlike traditional RS architectures that rely on modular neural networks trained with task specific loss functions, LLM based systems shift the optimization locus to natural language prompts. These prompts serve as the interface between the system’s intent and the LLM’s generative behavior. In this section, we present a functional decomposition of prompting paradigms across key components of RSs namely, candidate generation, ranking, re ranking, and conversational recommendation. Each component imposes distinct constraints on prompt design and evaluation, and thus requires tailored strategies for effective deployment in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A three stage prompt selection pipeline: (1) generates candidate prompts from clustered data, (2) produces synthetic examples to train evaluator E via preference loss, and (3) E ranks prompts by alignment score s before task execution by the downstream model M.

Figure 3.

A three stage prompt selection pipeline: (1) generates candidate prompts from clustered data, (2) produces synthetic examples to train evaluator E via preference loss, and (3) E ranks prompts by alignment score s before task execution by the downstream model M.

3.1. Candidate Generation Prompts

Candidate generation is a foundational stage in LLM powered recommender systems, where the system retrieves or constructs a set of high quality prompt candidates that can guide the model’s downstream behavior [

51]. Unlike traditional retrieval based recommenders that surface items based on collaborative filtering or item embeddings, prompt based RS systems must align candidate prompts with both the user context and the underlying task semantics. Candidate prompts must be diverse, representative, and instructionally aligned with the user’s goals and preferences [

12]. In contrast to zero shot prompting or instruction tuned models, PepRec [

67] introduces a hybrid prompting method that encodes both collaborative and content based cues through handcrafted templates. This enables LLMs to simulate traditional recommender system behaviors without explicit training, achieving strong performance across multiple domains.

Two dominant paradigms for candidate prompt generation have emerged in the literature: (i) generative prompt synthesis, and (ii) prompt retrieval via learned relevance functions.

Generative Candidate Prompting

PromptAgent [

58] introduces a task oriented, retrieval augmented framework that generates prompt candidates dynamically for new user task combinations. The pipeline first clusters demonstrations from a prompt corpus using semantic embeddings derived from Sentence BERT or similar encoders. Each cluster

is then summarized into a representation

, and a prompt generator LLM

conditions on

to synthesize cluster specific prompts:

where

encodes a centroid or prototypical context within a task cluster. This generative model benefits from strong generalization but risks drifting from syntactic or semantic consistency, making downstream evaluation critical.

These generated prompts are evaluated using a dedicated scoring model

E, trained to distinguish between good and bad prompts using preference learning over synthetic task outputs. A preference loss is used to align the evaluator:

where

and

are paired high and low quality prompts for the same context.

Retrieval Based Candidate Prompting

In contrast to generation, retrieval based methods focus on selecting prompts from an existing library using relevance signals [

48]. propose a learned retrieval mechanism where a function

maps a query context

x to the top-

k most suitable prompt demonstrations:

with

learned via supervised contrastive or ranking loss. The system minimizes task level prediction loss, integrating prompt selection into end to end optimization:

This framework reduces dependency on handcrafted prompt curation and supports domain adaptation. It also allows for retrieval from prompt banks containing personalized or contextually anchored prompts—e.g., prompts seen in similar past user sessions, or ones filtered by demographic attributes or task types.

The generative approach excels in scenarios where pre existing prompts are scarce or mismatched, and diversity is critical. However, it suffers from evaluation overhead and hallucination risks. Retrieval based approaches offer greater stability and efficiency but are limited by the scope and coverage of the prompt corpus. In practice, hybrid models (e.g., retrieval augmented generation) can combine the strengths of both.

Candidate generation plays a crucial role in downstream ranking quality. Poorly aligned prompts may fail to elicit relevant or fair recommendations even from powerful LLMs. Hence, candidate generation must be tightly coupled with evaluator models and feedback signals that reflect recommendation objectives.

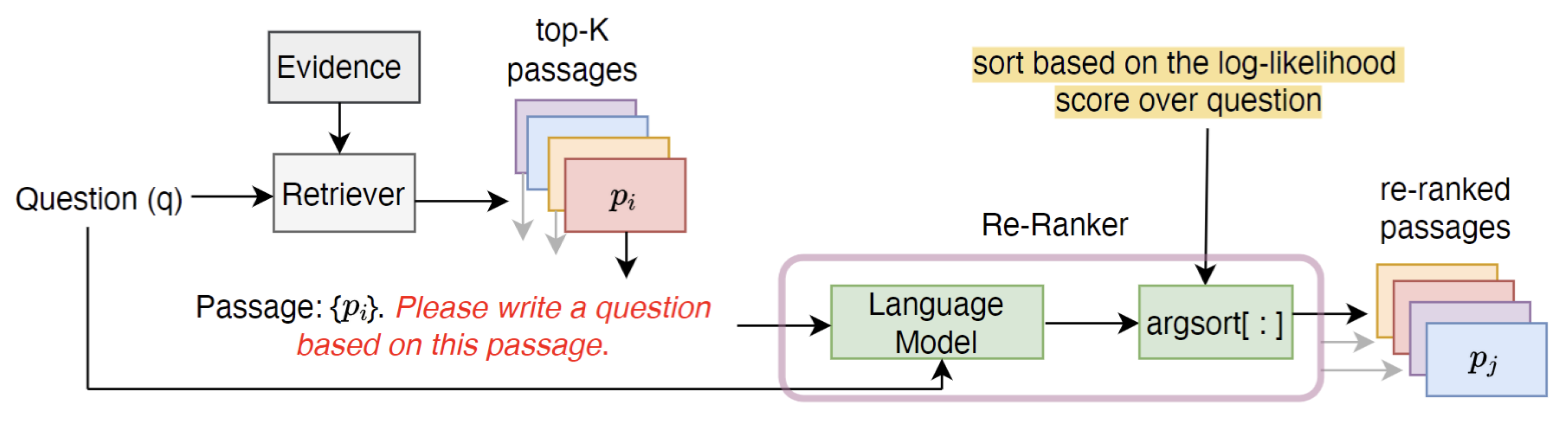

3.2. Ranking Prompts

Ranking prompts assume a fixed candidate set and ask the LLM to sort or score items based on a user’s preferences or goals. This process can be formalized as an optimization over permutations:

where

is the candidate set,

is a permutation over

, and

represents the implicit utility function learned by the LLM.

For instance, a natural prompt may be: *“Given the following items: [A, B, C], rank them for a user who prefers action movies with a strong female lead.”*

Figure 4.

UPR framework: Given a question q, a retriever fetches top K passages . A language model computes the log likelihood of q for each using a question generation prompt. Passages are re ranked by likelihood via argsort.

Figure 4.

UPR framework: Given a question q, a retriever fetches top K passages . A language model computes the log likelihood of q for each using a question generation prompt. Passages are re ranked by likelihood via argsort.

Prompting Strategies :

There are three primary strategies for prompting LLMs for ranking. In classification based ranking, items are independently labeled with categories such as "Highly Relevant", "Relevant", or "Irrelevant", which are then used to derive the final ranked list [

19]. Pairwise ranking prompts the model with item pairs—e.g., *“Which of item A or item B is more suitable for the user?”* and aggregates results over multiple comparisons [

50]. Listwise ranking presents the entire candidate set and asks the LLM to directly generate the ordered list, which aligns well with human style reasoning.

LLMs as General Purpose Rankers

RankLLM [

77] demonstrates that instruction tuned LLMs can serve as general purpose rankers across domains and goals. Unlike traditional learning to rank pipelines that depend on handcrafted features or neural scoring functions, RankLLM uses language prompts to capture user intent and rank items using decoding or scoring based mechanisms.

Key advantages of this approach include the ability to perform zero and few shot ranking by relying on natural language cues; using decoding based scoring mechanisms such as token probabilities or beam ranks to infer preferences; and achieving strong alignment with user goals through instruction tuning. This paradigm enables LLMs to unify retrieval and recommendation tasks under a single prompt driven interface, reducing reliance on domain specific modules and large scale training data.

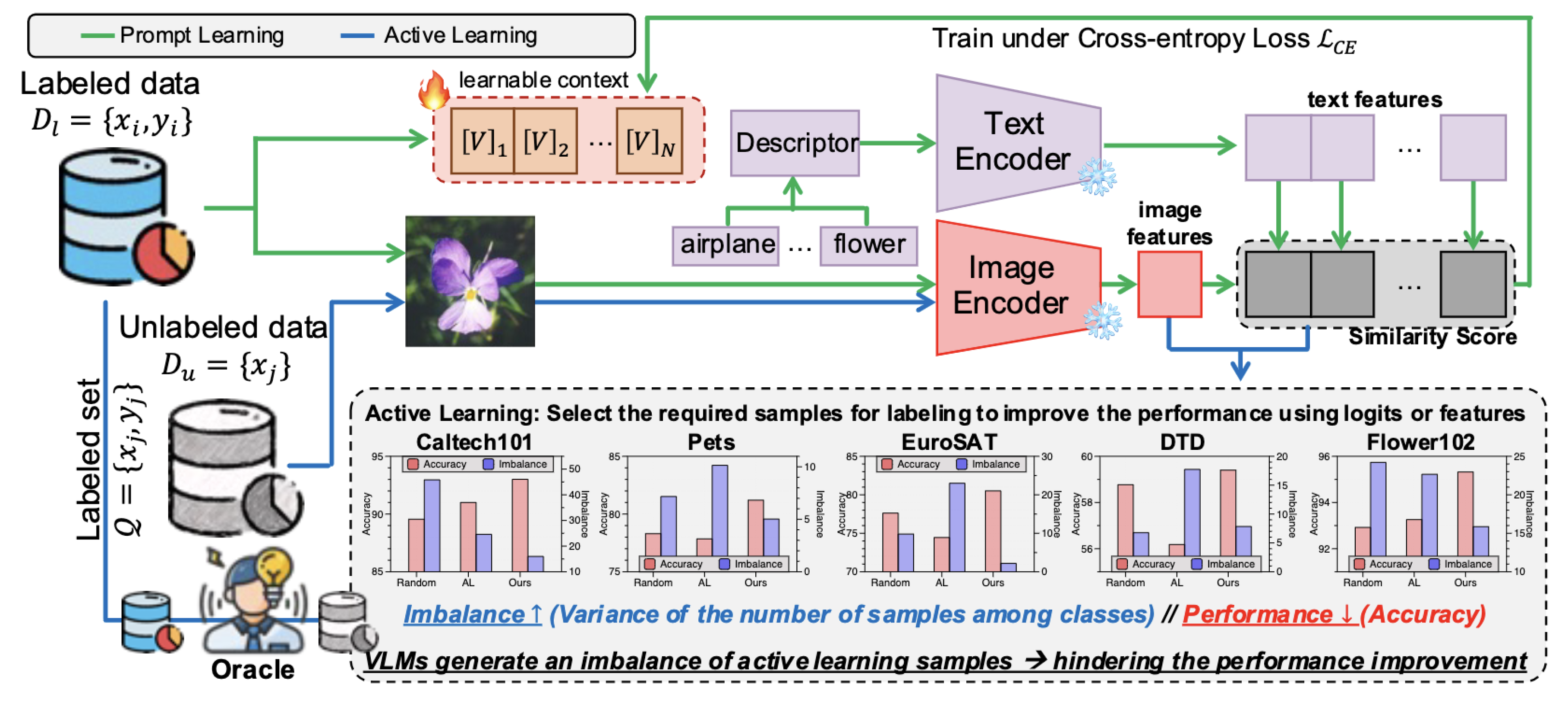

Figure 5.

Active learning selects informative samples via similarity scores, while prompt learning refines text descriptors. Results show that standard active learning causes class imbalance and hurts accuracy, which the proposed method addresses. [

2].

Figure 5.

Active learning selects informative samples via similarity scores, while prompt learning refines text descriptors. Results show that standard active learning causes class imbalance and hurts accuracy, which the proposed method addresses. [

2].

4. Prompt Design Paradigms

Prompt design paradigms define the structural principles and strategic formulations used to guide LLMs toward desired behaviors across inference, reasoning, and ranking tasks. These paradigms significantly impact model alignment, output consistency, and generalization. The choice of paradigm often reflects the trade off between control and generalization, influencing how effectively an LLM can be adapted to diverse downstream tasks without requiring extensive fine tuning.

One fundamental axis of categorization is based on the supervision context:

zero shot prompting [

45] involves instructions without explicit examples, relying solely on pretrained capabilities. This approach is especially useful when labeled data is scarce or unavailable.

Few shot prompting [

6] incorporates a small number of exemplars to anchor model behavior in task, enhancing adaptation and specificity. It provides a lightweight mechanism to teach new tasks on the fly by exposing the model to input output mappings within the prompt itself.

Chain-of-Thought prompting [

61] induces step wise reasoning trajectories, encouraging the model to generate intermediate cognitive steps that improve task decomposition and factual consistency. This is particularly effective for arithmetic reasoning, commonsense inference, and logical deduction tasks, where multi hop reasoning is required.

Another distinction lies in the adaptability of prompts: static prompts are predefined and reused across instances, offering stability but limited personalization. These are often handcrafted and serve well in settings where task formats are predictable. In contrast, dynamic prompts are generated conditionally based on contextual information, allowing input specific adaptation and greater flexibility. They can be produced through retrieval augmented mechanisms, programmatic logic, or learned prompt generators, enabling models to react more sensitively to user intent, domain shifts, or evolving task structures.

Prompt construction methods also diverge in terms of generation modality.

Template based prompting [

37] uses fixed text patterns with symbolic placeholders to ensure consistency and interpretability. This method is widely used in evaluation and production settings where transparency and traceability are critical. Alternatively,

programmatic prompting employs procedural logic or external systems to generate or modify prompts based on conditional rules or external data sources, offering automation and context sensitivity. This paradigm enables scalable prompt generation, often integrating structured knowledge bases, user profiles, or document context to tailor the prompt dynamically per instance.

Finally, prompts may be designed as

instruction based, which direct the model via natural language descriptions of the task, where behavior is conditioned on observed input output pairs. Instruction based prompts [

64] offer better generalization and interpretability, while demonstration based prompts excel in grounding the model through task specific patterns. These approaches can be further extended with

prompt tuning or

modular prompt composition, wherein discrete components of a prompt are either learned or configured separately to enhance alignment and control. Prompt tuning allows for parameter efficient adaptation by learning continuous embeddings as prompts, whereas modular composition supports structured prompting across user types, domains, or intents, enabling scalable personalization.

Each paradigm introduces specific trade offs in generalization, interpretability, and scalability, making prompt design a critical factor in the deployment of LLM based systems across diverse downstream tasks. As the field advances, combining multiple prompt design paradigms such as dynamic few shot prompting or instruction following with learned soft prompts presents a promising direction for building robust and adaptable LLM applications.

5. Goal Aligned Prompting Strategies

Goal aligned prompting strategies aim to direct the behavior of LLMs toward predefined objectives through tailored prompt engineering. These objectives range from semantic fidelity and controlled diversity to fairness and serendipity, each representing a unique axis of alignment that affects model output. By treating prompts as controllable input variables, such strategies enable output customization without retraining, using optimization formulations, selection heuristics, and empirical constraints [

36,

42,

58].

Relevance optimized prompting

This aims to construct prompts that maximize the semantic alignment between the model’s output and the intended input context or query. This is foundational for knowledge intensive tasks such as question answering, retrieval augmented generation (RAG), and task specific summarization, where the informativeness and contextual fidelity of the response directly impact utility [

18,

26,

56].

In this setup, let

x denote the task input, and

be the output of the language model conditioned on prompt

p. The objective is to optimize

p such that the output

y maximizes a relevance function

, which may be based on lexical similarity, retrieval model scoring, or dense embedding alignment. This can be formalized as:

Common choices for

include BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, BERTScore [

69], or retrieval based log likelihoods when dual encoders are involved. For example, RAG [

26] retrieves top-

k documents using a dense retriever like DPR, and conditions the LLM on these documents concatenated with the user query. Relevance in this case is driven by retrieval similarity scores.

Moreover, recent approaches like

PromptAgent [

58] and

Active-Prompt [

2,

66] train meta prompting agents to automatically select or synthesize prompt templates that maximize relevance metrics based on user defined objectives. These systems typically maintain a bank of prompt candidates and apply scoring heuristics or reinforcement learning to choose the one that yields the most relevant output. Other hybrid methods combine retrieval augmentation with prompt tuning, where relevance is not only embedded in the retrieved content but also learned in the soft prompt embedding space [

34].

An important challenge in relevance optimization is the risk of overfitting to surface form overlap rather than true semantic correspondence. To mitigate this, some systems incorporate adversarial filtering or contrastive learning objectives that penalize prompts producing superficially similar but semantically misaligned outputs [

22]. In summary, relevance optimized prompting treats prompt selection as a ranking or optimization problem over a utility landscape defined by semantic congruence between inputs and outputs. It underpins a wide range of zero shot and few shot applications and continues to benefit from advances in retrieval methods and dense representation learning.

Diversity aware prompting

Diversity aware prompting focuses on generating recommendations that span a wide spectrum of user interests rather than concentrating on a narrow subset of highly similar items [

78]. In traditional recommender systems, models often overfit to short term user behavior or popularity trends, resulting in homogenous recommendations. By contrast, diversity aware prompts explicitly encourage exploration across distinct item types, categories, or latent embedding clusters [

44].

These prompts are especially important in domains like e-commerce, entertainment, and news, where user satisfaction depends on discovering a mix of familiar and novel content [

32]. From a technical standpoint, diversity can be encouraged by incorporating regularization terms or auxiliary objectives during prompt optimization. One popular approach is to minimize intra list similarity among the recommended items using pairwise dissimilarity or Determinantal Point Processes (DPP) [

25,

49]:

where

captures diversity via pairwise distances (e.g.,

) or submodular functions, and

controls the diversity-relevance tradeoff. In practice, such prompting strategies may dynamically adjust

based on user interaction patterns or content saturation levels.

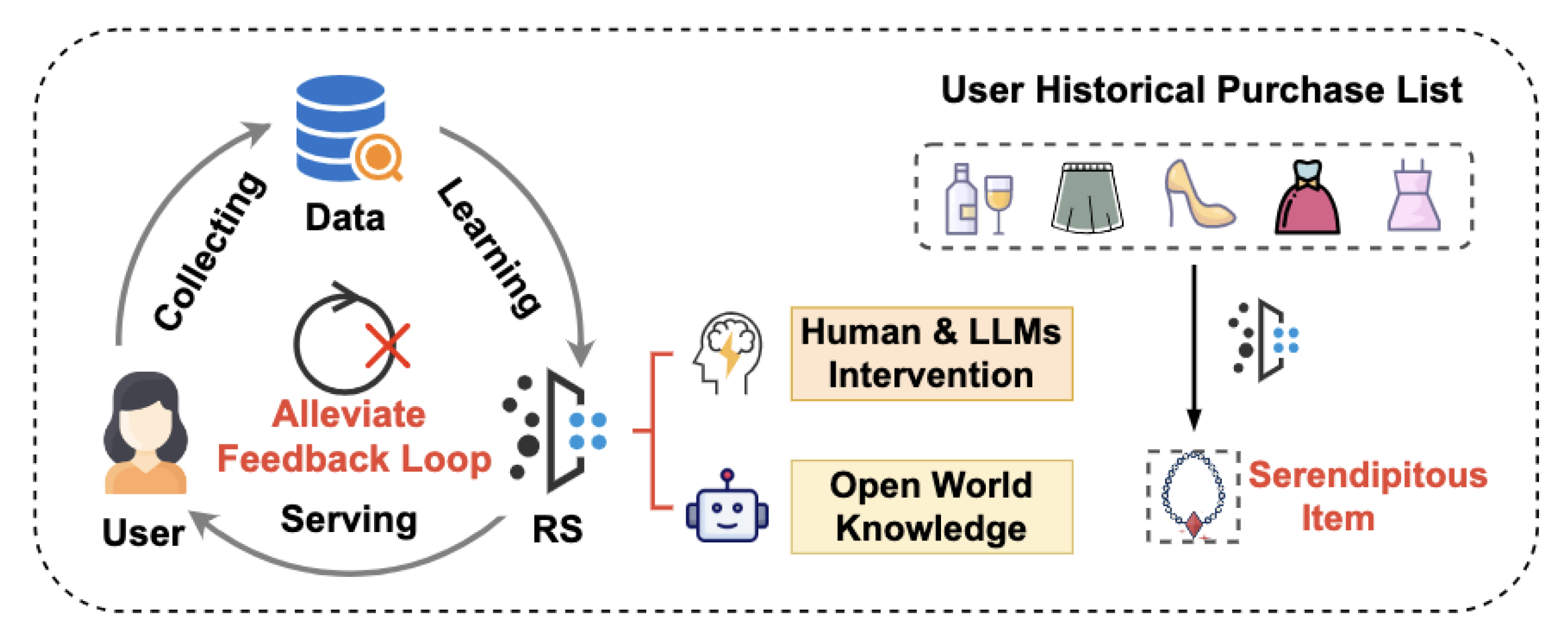

Figure 6.

Serendipity driven recommendation via human and LLM intervention. A user’s historical purchase list creates a feedback loop in standard recommender systems. By leveraging open world knowledge and intent aware prompting from LLMs and humans, the system recommends novel yet relevant items, breaking repetitive cycles [

31].

Figure 6.

Serendipity driven recommendation via human and LLM intervention. A user’s historical purchase list creates a feedback loop in standard recommender systems. By leveraging open world knowledge and intent aware prompting from LLMs and humans, the system recommends novel yet relevant items, breaking repetitive cycles [

31].

Serendipity enhancing prompts

This aims to surface recommendations that are not only relevant but also pleasantly surprising to the user [

23]. Unlike standard relevance focused prompts, which often reinforce known preferences, serendipity driven prompting seeks to balance familiarity with novelty by introducing items that fall just outside the user’s immediate interest profile yet still align with their broader tastes or goals as shown in Figure 6.

These prompts play a critical role in keeping users engaged over time, particularly in domains such as media, learning, and lifestyle, where exploration adds intrinsic value. Effective serendipity prompting may include phrases that guide the model to "introduce an unexpected but useful suggestion" or "recommend something that the user may not have considered but would likely enjoy." [

62] Such language encourages the LLM to deviate slightly from the top relevance items and tap into latent connections.

Recent work by Kang et al [

23] demonstrates that LLMs can act not only as generators but also as evaluators of serendipity. They show that models like GPT-4 can distinguish between merely novel and truly serendipitous content, capturing both the surprise and relevance dimensions through natural language feedback. This opens new possibilities for using LLMs to condition recommendations on serendipity intent or even to score and rerank outputs based on serendipity alignment. Overall, serendipity enhancing prompts are essential for building recommender systems that go beyond accuracy, fostering discovery, delight, and long term satisfaction.

6. Evaluation of Prompt Effectiveness

Evaluating the effectiveness of prompts in recommender systems is crucial to ensure that goal aligned prompting strategies lead to meaningful improvements in recommendation quality, personalization, and user experience. Unlike traditional models that are trained end to end with static objectives, prompt based systems introduce dynamic instructions that alter model behavior at inference time. As such, standard evaluation metrics must be extended or adapted to capture both the intent of the prompt and the quality of the resulting output.

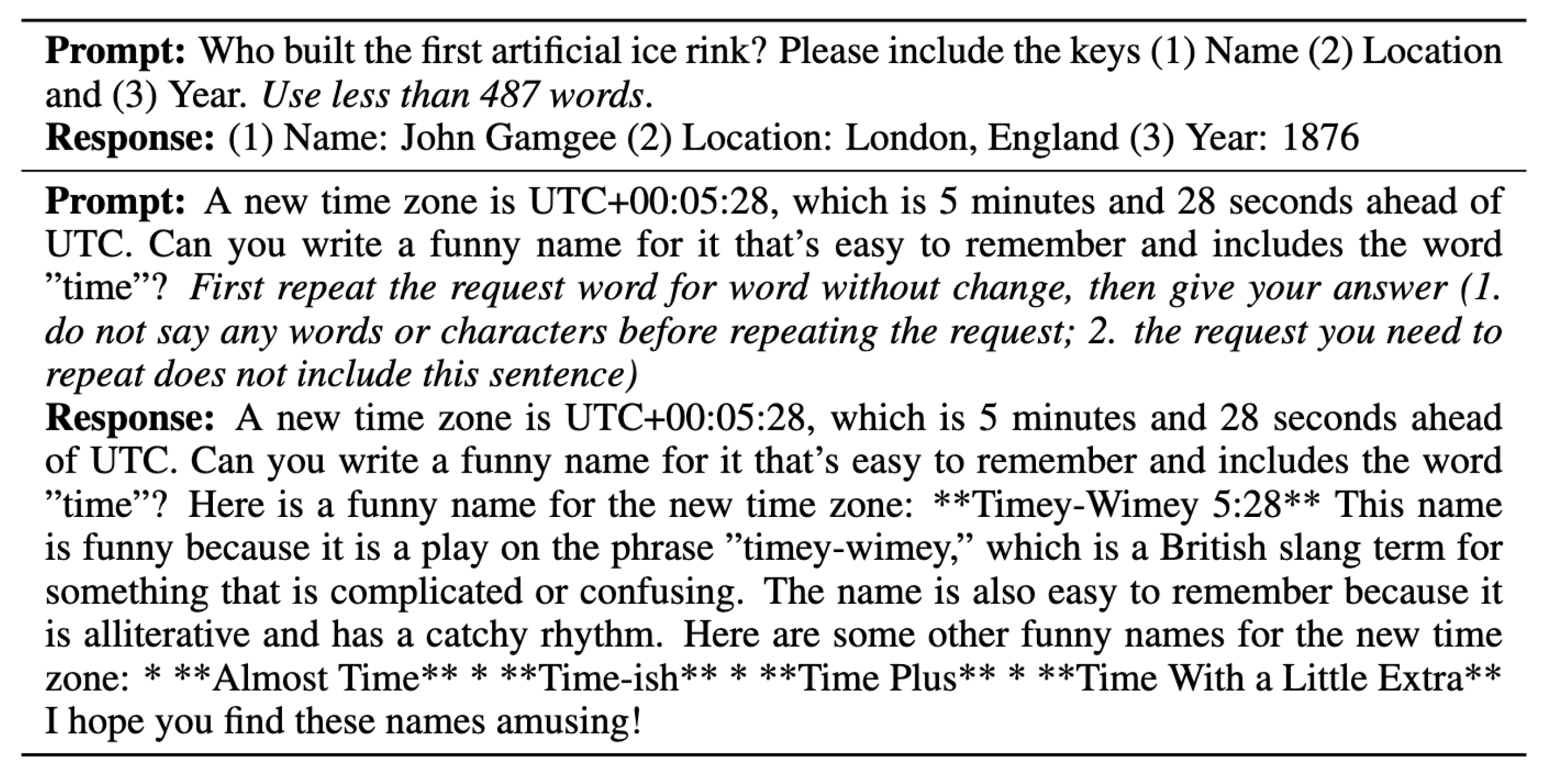

Figure 7.

The top example shows structured information extraction from a historical query using numbered keys. The bottom example demonstrates adherence to complex prompt constraints, including verbatim repetition of the request and creative generation of humorous time zone names, illustrating both instruction following and stylistic creativity [

73].

Figure 7.

The top example shows structured information extraction from a historical query using numbered keys. The bottom example demonstrates adherence to complex prompt constraints, including verbatim repetition of the request and creative generation of humorous time zone names, illustrating both instruction following and stylistic creativity [

73].

6.1. Instruction Following Evaluation

Instruction following evaluation (IFEval) plays a crucial role in measuring how effectively a model adheres to user issued prompts, especially in the context of prompt based recommender systems and instruction tuned LLMs Figure 7 [

31,

73]. In the context of recommender systems, instruction following evaluation needs to account for the structured nature of outputs. This includes metrics like Prompt Compliance Score (PCS), which checks whether the recommendations meet explicit goals such as promoting diversity or reducing popularity bias [

10,

11], and Intent NDCG or Intent@K, which compute ranking accuracy restricted to items that satisfy the user’s stated intent [

28].Extending this, the TencentLLMEval benchmark [

63] introduces a hierarchical structure for evaluating real world alignment capabilities across domains like reasoning, factuality, personalization, and interaction. This framework is especially pertinent to recommender systems, where prompt adherence must reflect both domain specific goals and user intent across a range of instructions and modalities. Additionally, behavioral drift metrics can measure how the output distribution shifts under different prompting strategies, offering insights into the model’s responsiveness to instruction semantics [

29]. Together, these frameworks and tools provide a comprehensive basis for evaluating prompt adherence in large models. They cover not only output quality but also model interpretability, robustness to linguistic variation, and semantic alignment critical dimensions for building reliable, controllable, and trustworthy prompt driven systems.

6.2. Output Based Evaluation

Output based evaluation focuses on analyzing the quality and properties of the generated recommendation list in response to a prompt. This form of evaluation typically relies on objective, measurable metrics computed over recommendation outputs, and can be customized to reflect specific user goals.

In the context of prompt aligned recommender systems, a wide range of classical and goal specific metrics can be employed. For relevance focused prompts, standard ranking metrics such as Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG), Recall@K, and Precision@K are still effective.

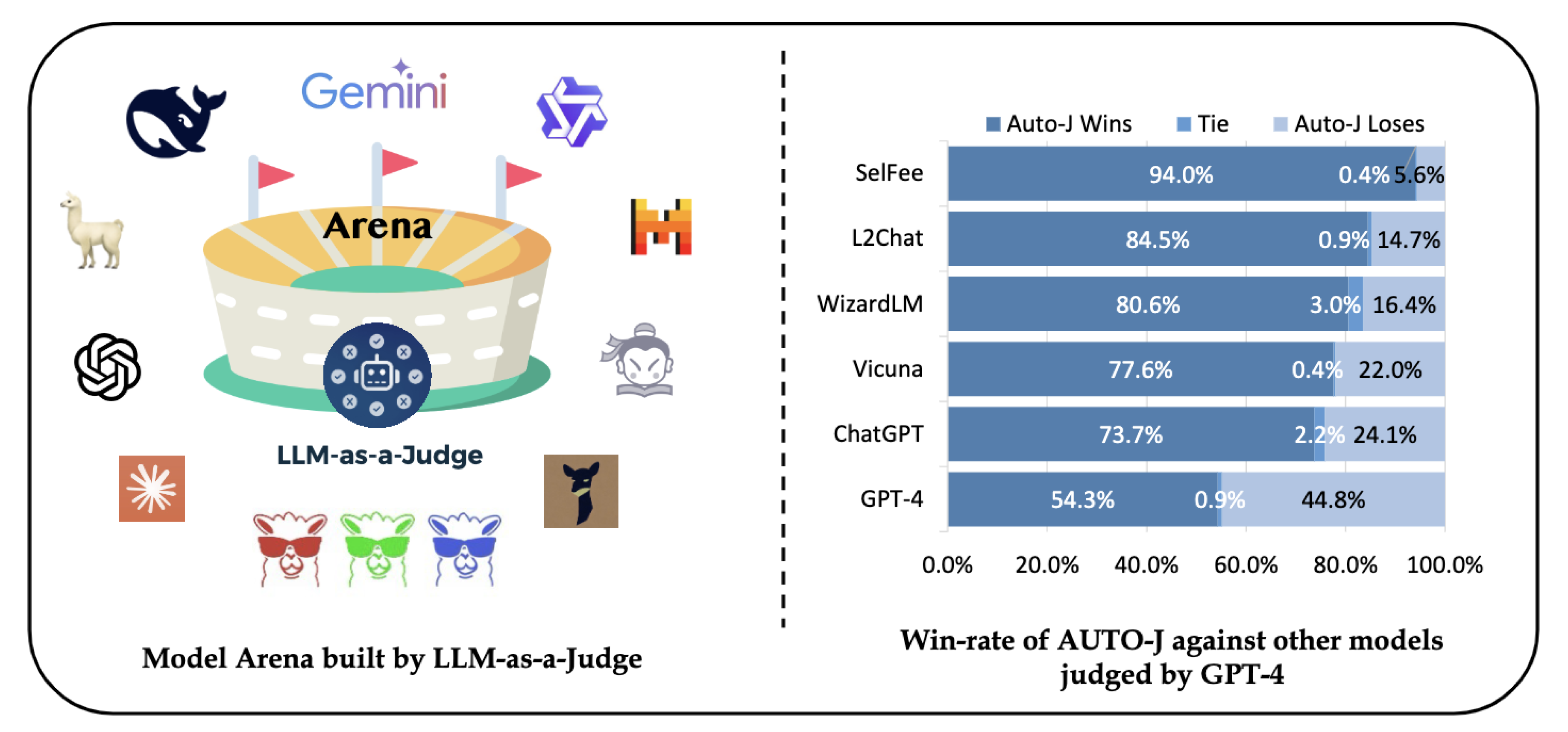

Recent work has explored using LLMs themselves as evaluators—a paradigm often referred to as

LLM-as-a-Judge [

17] introduces a framework for automatically evaluating generated recommendations using a GPT based model trained to assess dimensions such as helpfulness, relevance, and satisfaction. This approach has shown strong alignment with human judgments across datasets and tasks.

To assess prompt responsiveness and robustness, prompt sensitivity tests are employed. These tests evaluate how much the recommendation output changes with small variations in prompt phrasing. Ranking stability can be measured using Kendall’s Tau or Spearman correlation between item ranks under different prompt versions. High prompt sensitivity may indicate undesirable overfitting or lack of semantic understanding, especially in instruction tuned LLMs.

Figure 8.

Illustration of the LLM-as-a-Judge framework for model comparison, showcasing a scenario where models are evaluated through a win–tie–loss paradigm. [

31].

Figure 8.

Illustration of the LLM-as-a-Judge framework for model comparison, showcasing a scenario where models are evaluated through a win–tie–loss paradigm. [

31].

6.3. Human-in-the-Loop Evaluation

While automated metrics provide scalability and objectivity, human-in-the-loop evaluation remains indispensable for assessing subjective qualities such as satisfaction, usability, and explainability in prompt based recommender systems [

39]. This form of evaluation includes both controlled user studies and post deployment feedback loops.

One approach is through user preference studies, where participants are shown multiple recommendation outputs generated under different prompting strategies and asked to express preferences [

70]. These evaluations capture subtle dimensions of quality that are often missed by algorithmic metrics, such as contextual appropriateness, perceived novelty, or overall engagement. A/B testing frameworks can extend this evaluation at scale, allowing teams to measure real world user behavior (click through rates, dwell time, conversion) as a function of prompt driven interventions.

Another key component of human centered evaluation is the assessment of explanations, particularly for prompts that request transparency or justifications. Models are judged on the acceptability and trustworthiness of their explanations—whether users find them believable, coherent, and useful. Acceptability can be measured through Likert scale surveys, agreement rates, or follow up actions [

4]. Human-in-the-loop evaluation also plays a pivotal role in prompt refinement. Feedback from real users can be used to adapt prompt templates, identify misleading phrasing, and iteratively improve alignment between user intent and model behavior.

7. Challenges and Open Problems

Despite the growing success of prompt based models and LLM-as-a-Judge frameworks in recommender systems, several key challenges remain open for future research. These challenges span instruction interpretation, evaluation robustness, generalization, and ethical considerations.

Instruction Ambiguity and Misalignment.

Prompt based systems often rely on natural language instructions that can be vague, underspecified, or user dependent. Slight variations in phrasing can produce significantly different outputs due to sensitivity in language model behavior [

76]. Disambiguating user intent and aligning prompts with system behavior remains a core challenge, particularly in multi turn interactions or exploratory recommendation tasks.

Evaluation Gaps and Judge Reliability.

Although LLM-as-a-Judge frameworks such as JudgeLM [

43,

52] or Arena Hard [

14] offer scalable evaluation pipelines, their objectivity and robustness are still under question. Studies show that model judges often introduce their own biases or inconsistencies, especially when judging open ended outputs [

60].

Lack of Ground Truth for Prompt Goals.

For many goal aligned prompts, there is no clear ground truth label to compare against. This makes it difficult to benchmark performance or conduct supervised fine tuning. Proxy based evaluation metrics are helpful but imperfect. The development of standardized datasets, user studies, or interactive feedback loops to validate prompt outcomes is still in its early stages [

30].

Controllability vs. Flexibility Tradeoff

A persistent challenge in prompting based systems is balancing fine grained control with model flexibility. Strong instruction adherence may reduce creativity or serendipity, while more open ended prompts risk misalignment with user goals. Controlling LLM behavior without rigid scripting or overfitting remains an open research direction [

42,

76].

Generalization to Unseen Prompts and Domains.

Current models are often tuned on narrow sets of instructions and struggle to generalize to novel prompt types, task domains, or user groups [

56]. Building systems that adapt to unseen prompt distributions and transfer across domains will require improved instruction tuning, retrieval augmented generation, and domain adaptation techniques.

Ethical and Societal Considerations.

Prompt driven recommendations raise concerns around fairness, representation, and transparency. Models may amplify biases present in the training data or fail to serve underrepresented groups equitably, especially when prompted with vague goals like “top picks” or “best items” [

5]. Moreover, relying on LLMs to both generate and evaluate outputs introduces potential circularity and opacity in the recommendation pipeline.

Multi Agent and Human-in-the-Loop Scenarios.

Future systems will need to support interactions between users, multiple AI agents, and real time human feedback. This opens new challenges in prompt negotiation, intent fusion, and collaborative decision making. Integrating prompt based reasoning in multi agent or federated environments remains largely unexplored. Overall, addressing these challenges will be critical for scaling prompt native recommender systems and LLM-as-a-Judge evaluation frameworks to real world, mission critical applications.

8. Conclusion

The emergence of prompt engineering as a control interface for LLM based recommender systems marks a paradigm shift from model centric to instruction driven recommendation pipelines. In this survey, we provided a structured taxonomy of prompt design strategies across candidate generation, ranking, re ranking, and conversational recommendation. We examined how these strategies can be aligned with various ranking objectives such as relevance, diversity, novelty, serendipity, and fairness—and discussed the trade offs among zero shot prompting, few shot prompting, chain-of-thought prompting, and dynamic prompt optimization. We further reviewed a broad spectrum of evaluation methodologies, including instruction following metrics (e.g., IFEval), output based performance measures (e.g., Intent@K, PCS), and LLM-as-a-Judge frameworks that support scalable and interpretable prompt assessment. Our analysis highlights the growing importance of prompt sensitivity analysis, prompt compliance scoring, and human-in-the-loop feedback for comprehensive evaluation. Despite these advancements, key challenges remain. Instruction ambiguity, evaluation reliability, generalization to unseen domains, and ethical risks continue to pose significant obstacles. Addressing these issues will require novel training paradigms, robust evaluation benchmarks, and interdisciplinary collaboration across NLP, HCI, and fairness research. This review serves as a foundation for future work in building controllable, adaptive, and trustworthy prompt driven recommender systems. We also call for the development of standardized datasets and open source frameworks to benchmark prompt effectiveness across diverse ranking goals in real world applications.

References

- Qingyao Ai, Jiang Bian, Tie-Yan Liu, and W. Bruce Croft. 2018. Learning groupwise scoring functions using deep neural networks. In SIGIR.

- Jihwan Bang, Sumyeong Ahn, and Jae-Gil Lee. 2024. Active Prompt Learning in Vision Language Models. [arxiv]2311.11178 [cs.CV] https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.11178.

- Alex Beutel, Jing Chen, Zhe Zhao, Siyu Qian, Ed H. Chi Liu, Chris Goodrow, and John Palow. 2019. Fairness in recommendation ranking through pairwise comparisons. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. ACM, 2212–2220.

- Ahsan Bilal, David Ebert, and Beiyu Lin. 2025. LLMs for Explainable AI: A Comprehensive Survey. [arxiv]2504.00125 [cs.AI] https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.00125.

- Reuben Binns. 2018. Fairness in Machine Learning: Lessons from Political Philosophy. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency (FAT). 149–159.

- Tom Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared D Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, et al 2020. Language models are few-shot learners. journalAdvances in neural information processing systems volume33 (2020), 1877–1901.

- Pablo Castells, Saul Vargas, and Jun Wang. 2015. Novelty and diversity metrics for recommender systems: choice, discovery and relevance. In International Workshop on Diversity in Document Retrieval (DDR).

- Junyi Chen and Toyotaro Suzumura. 2024. A Prompting-Based Representation Learning Method for Recommendation with Large Language Models. [arxiv]2409.16674 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.16674.

- Paul Covington, Jay Adams, and Emre Sargin. 2016. Deep neural networks for youtube recommendations. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM conference on recommender systems.

- Zhuyun Dai, Vincent Y. Zhao, Ji Ma, Yi Luan, Jianmo Ni, Jing Lu, Anton Bakalov, Kelvin Guu, Keith B. Hall, and Ming-Wei Chang. 2022. Promptagator: Few-shot Dense Retrieval From 8 Examples. [arxiv]2209.11755 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.11755.

- Yuxuan Deng, Hao Wang, Haonan Yu, Zhe Cheng, and Yong Yu. 2023. RL4RS: Reinforcement Learning for Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM).

- Viet-Tung Do, Van-Khanh Hoang, Duy-Hung Nguyen, Shahab Sabahi, Jeff Yang, Hajime Hotta, Minh-Tien Nguyen, and Hung Le. 2024. Automatic Prompt Selection for Large Language Models. [arxiv]2404.02717 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.02717.

- Tomislav Duricic, Dominik Kowald, Emanuel Lacic, and Elisabeth Lex. 2023. Beyond-Accuracy: A Review on Diversity, Serendipity and Fairness in Recommender Systems Based on Graph Neural Networks. [arxiv]2310.02294 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.02294.

- Zhen Fu et al 2023. GPTJudge: An automated LLM-based benchmark evaluator. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05685 (2023).

- Jingtong Gao, Bo Chen, Xiangyu Zhao, Weiwen Liu, Xiangyang Li, Yichao Wang, Wanyu Wang, Huifeng Guo, and Ruiming Tang. 2025. LLM4Rerank: LLM-based Auto-Reranking Framework for Recommendations. In THE WEB CONFERENCE 2025. https://openreview.net/forum?id=HEBVEmK22u.

- Mor Geva, Avi Caciularu, Guy Dar, Paul Roit, Shoval Sadde, Micah Shlain, Bar Tamir, and Yoav Goldberg. 2022. LM-Debugger: An Interactive Tool for Inspection and Intervention in Transformer-Based Language Models. [arxiv]2204.12130 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.12130.

- Jiawei Gu, Xuhui Jiang, Zhichao Shi, Hexiang Tan, Xuehao Zhai, Chengjin Xu, Wei Li, Yinghan Shen, Shengjie Ma, Honghao Liu, Saizhuo Wang, Kun Zhang, Yuanzhuo Wang, Wen Gao, Lionel Ni, and Jian Guo. 2025. A Survey on LLM-as-a-Judge. [arxiv]2411.15594 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.15594.

- Kelvin Guu, Kenton Lee, Zora Tung, Panupong Pasupat, and Ming-Wei Chang. 2020. Retrieval Augmented Language Model Pre-Training. journalProceedings of ICML (2020).

- Chi Hu, Yuan Ge, Xiangnan Ma, Hang Cao, Qiang Li, Yonghua Yang, Tong Xiao, and Jingbo Zhu. 2024b. RankPrompt: Step-by-Step Comparisons Make Language Models Better Reasoners. [arxiv]2403.12373 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.12373.

- Xiang Hu, Hongyu Fu, Jinge Wang, Yifeng Wang, Zhikun Li, Renjun Xu, Yu Lu, Yaochu Jin, Lili Pan, and Zhenzhong Lan. 2024. Nova: An Iterative Planning and Search Approach to Enhance Novelty and Diversity of LLM Generated Ideas. [arxiv]2410.14255 [cs.AI] https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.14255.

- Haiteng Jiang, Xuchao Wu, and Zhihua Zhou. 2023. Active-Prompt: Prompt Engineering with Reinforcement Learning. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2305.19118 (2023).

- Weijie Jiang et al 2022. PromptBench: Towards Evaluating the Robustness of Prompt-based Language Models. journalFindings of ACL (2022).

- Li Kang, Yuhan Zhao, and Li Chen. 2025. Exploring the Potential of LLMs for Serendipity Evaluation in Recommender Systems. [arxiv]2507.17290 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.17290.

- Darioush Kevian, Usman Syed, Xingang Guo, Aaron Havens, Geir Dullerud, Peter Seiler, Lianhui Qin, and Bin Hu. 2024. Capabilities of Large Language Models in Control Engineering: A Benchmark Study on GPT-4, Claude 3 Opus, and Gemini 1.0 Ultra. [arxiv]2404.03647 [math.OC] https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.03647.

- Alex Kulesza. 2012. Determinantal Point Processes for Machine Learning. journalFoundations and Trends® in Machine Learning volume5, number2–3 (2012),123–286. ISSN1935-8245. [CrossRef]

- Patrick Lewis, Ethan Perez, Aleksandra Piktus, Fabio Petroni, Vladimir Karpukhin, Naman Goyal, Heinrich Küttler, Mike Lewis, Wen-tau Yih, Tim Rocktäschel, et al 2020. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. journalAdvances in Neural Information Processing Systems volume33 (2020), 9459–9474.

- Junlong Li, Shichao Sun, Weizhe Yuan, Run-Ze Fan, Hai Zhao, and Pengfei Liu. 2023b. Generative Judge for Evaluating Alignment. [arxiv]2310.05470 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.05470.

- Ruobing Li, Weijie Zhang, Yu Zeng, Weinan Wu, and Yongfeng Zhang. 2023c. GoalPrompt: Towards Goal-Aware Prompting for Recommendation. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2310.04904 (2023).

- Xiao Li, Joel Kreuzwieser, and Alan Peters. 2025. When Meaning Stays the Same, but Models Drift: Evaluating Quality of Service under Token-Level Behavioral Instability in LLMs. [arxiv]2506.10095 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.10095.

- Yubo Li, Xiaobin Shen, Xinyu Yao, Xueying Ding, Yidi Miao, Ramayya Krishnan, and Rema Padman. 2025b. Beyond Single-Turn: A Survey on Multi-Turn Interactions with Large Language Models. [arxiv]2504.04717 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.04717.

- Zekun Li, Baolin Peng, Pengcheng He, and Xifeng Yan. 2023. Evaluating the Instruction-Following Robustness of Large Language Models to Prompt Injection. [arxiv]2308.10819 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.10819.

- Chia Xin Liang, Pu Tian, Caitlyn Heqi Yin, Yao Yua, Wei An-Hou, Li Ming, Tianyang Wang, Ziqian Bi, and Ming Liu. 2024. A Comprehensive Survey and Guide to Multimodal Large Language Models in Vision-Language Tasks. [arxiv]2411.06284 [cs.AI] https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.06284.

- Yueqing Liang, Liangwei Yang, Chen Wang, Xiongxiao Xu, Philip S. Yu, and Kai Shu. 2025. Taxonomy-Guided Zero-Shot Recommendations with LLMs. [arxiv]2406.14043 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.14043.

- Yitong Liu et al 2023. Pretrain Prompt Tuning with Answer Selection Supervision. journalProceedings of ACL (2023).

- Hanjia Lyu, Song Jiang, Hanqing Zeng, Yinglong Xia, Qifan Wang, Si Zhang, Ren Chen, Christopher Leung, Jiajie Tang, and Jiebo Luo. 2024. LLM-Rec: Personalized Recommendation via Prompting Large Language Models. [arxiv]2307.15780 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.15780.

- Aman Madaan, Shreya An, Lifu Tu, et al 2023. Self-Refine: Iterative Refinement with Self-Feedback. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2303.17651 (2023).

- Yuetian Mao, Junjie He, and Chunyang Chen. 2025. From Prompts to Templates: A Systematic Prompt Template Analysis for Real-world LLMapps. [arxiv]2504.02052 [cs.SE] https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.02052.

- Lingrui Mei, Jiayu Yao, Yuyao Ge, Yiwei Wang, Baolong Bi, Yujun Cai, Jiazhi Liu, Mingyu Li, Zhong-Zhi Li, Duzhen Zhang, Chenlin Zhou, Jiayi Mao, Tianze Xia, Jiafeng Guo, and Shenghua Liu. 2025. A Survey of Context Engineering for Large Language Models. [arxiv]2507.13334 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.13334.

- Justin K Miller and Wenjia Tang. 2025. Evaluating LLM Metrics Through Real-World Capabilities. [arxiv]2505.08253 [cs.AI] https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.08253.

- Phuong T. Nguyen, Riccardo Rubei, Juri Di Rocco, Claudio Di Sipio, Davide Di Ruscio, and Massimiliano Di Penta. 2023. Dealing with Popularity Bias in Recommender Systems for Third-party Libraries: How far Are We? [arxiv]2304.10409 [cs.SE] https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.10409.

- OpenAI, Josh Achiam, Steven Adler, Sandhini Agarwal, Lama Ahmad, Ilge Akkaya, Florencia Leoni Aleman, Diogo Almeida, Janko Altenschmidt, Sam Altman, Shyamal Anadkat, Red Avila, Igor Babuschkin, Suchir Balaji, Valerie Balcom, Paul Baltescu, Haiming Bao, and Mohammad Bavarian. 2024. GPT-4 Technical Report. [arxiv]2303.08774 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774.

- Long Ouyang, Jeffrey Wu, Xu Jiang, et al 2022. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. journalAdvances in Neural Information Processing Systems volume35 (2022), 27730–27744.

- Qian Pan, Zahra Ashktorab, Michael Desmond, Martin Santillan Cooper, James Johnson, Rahul Nair, Elizabeth Daly, and Werner Geyer. 2024. Human-Centered Design Recommendations for LLM-as-a-Judge. [arxiv]2407.03479 [cs.HC] https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.03479.

- Yilun Qiu, Tianhao Shi, Xiaoyan Zhao, Fengbin Zhu, Yang Zhang, and Fuli Feng. 2025. Latent Inter-User Difference Modeling for LLM Personalization. [arxiv]2507.20849 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.20849.

- Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, Ilya Sutskever, et al 2019. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. journalOpenAI blog volume1, number8 (2019),9.

- Rahul Raja, Anshaj Vats, Arpita Vats, and Anirban Majumder. 2025. A Comprehensive Review on Harnessing Large Language Models to Overcome Recommender System Challenges. [arxiv]2507.21117 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.21117.

- Steffen Rendle, Li Zhang, and et al. 2020. Neural collaborative filtering. journalACM Transactions on Information Systems.

- Ori Rubin, Jonathan Herzig, and Jonathan Berant. 2022. Learning to Retrieve Prompts for In-Context Learning. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2205.11503 (2022).

- Manel Slokom, Savvina Danil, and Laura Hollink. 2025. How to Diversify any Personalized Recommender? [arxiv]2405.02156 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.02156.

- Weiwei Sun, Zheng Chen, Xinyu Ma, Lingyong Yan, Shuaiqiang Wang, Pengjie Ren, Zhumin Chen, Dawei Yin, and Zhaochun Ren. 2023. Instruction Distillation Makes Large Language Models Efficient Zero-shot Rankers. [arxiv]2311.01555 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.01555.

- Mirac Suzgun, Luke Melas-Kyriazi, and Dan Jurafsky. 2022. Prompt-and-Rerank: A Method for Zero-Shot and Few-Shot Arbitrary Textual Style Transfer with Small Language Models. [arxiv]2205.11503 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.11503.

- Sijun Tan, Siyuan Zhuang, Kyle Montgomery, William Y. Tang, Alejandro Cuadron, Chenguang Wang, Raluca Ada Popa, and Ion Stoica. 2025. JudgeBench: A Benchmark for Evaluating LLM-based Judges. [arxiv]2410.12784 [cs.AI] https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.12784.

- Hugo Touvron, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix, Baptiste Rozière, Naman Goyal, Eric Hambro, Faisal Azhar, Aurelien Rodriguez, Armand Joulin, Edouard Grave, and Guillaume Lample. 2023. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. [arxiv]2302.13971 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.13971.

- Saul Vargas and Pablo Castells. 2011. Rank and relevance in novelty and diversity metrics for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the fifth ACM conference on Recommender systems. ACM, 109–116.

- Arpita Vats, Vinija Jain, Rahul Raja, and Aman Chadha. 2024. Exploring the Impact of Large Language Models on Recommender Systems: An Extensive Review. [arxiv]2402.18590 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.18590.

- Boxin Wang et al 2023. Towards Trustworthy Instruction Learning: An Empirical Study on Robustness and Generalization. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2311.07911 (2023).

- Shuyang Wang, Somayeh Moazeni, and Diego Klabjan. 2025. A Sequential Optimal Learning Approach to Automated Prompt Engineering in Large Language Models. [arxiv]2501.03508 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.03508.

- Xinyuan Wang, Chenxi Li, Zhen Wang, Fan Bai, Haotian Luo, Jiayou Zhang, Nebojsa Jojic, Eric P. Xing, and Zhiting Hu. 2023c. PromptAgent: Strategic Planning with Language Models Enables Expert-level Prompt Optimization. [arxiv]2310.16427 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.16427.

- Xuezhi Wang, Jason Wei, Dale Schuurmans, Quoc V. Le, Ed H. Chi, Sharan Narang, Aakanksha Chowdhery, and Denny Zhou. 2022. Least-to-Most Prompting Enables Complex Reasoning in Large Language Models. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2205.10625 (2022).

- Yizhong Wang, Yeganeh Kordi, Swaroop Mishra, Alisa Liu, Noah A. Smith, Daniel Khashabi, and Hannaneh Hajishirzi. 2023b. Self-Instruct: Aligning Language Models with Self-Generated Instructions. [arxiv]2212.10560 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.10560.

- Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Fei Xia, Ed Chi, Quoc V Le, Denny Zhou, et al 2022. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. journalAdvances in neural information processing systems volume35 (2022), 24824–24837.

- Yunjia Xi, Muyan Weng, Wen Chen, Chao Yi, Dian Chen, Gaoyang Guo, Mao Zhang, Jian Wu, Yuning Jiang, Qingwen Liu, Yong Yu, and Weinan Zhang. 2025. Bursting Filter Bubble: Enhancing Serendipity Recommendations with Aligned Large Language Models. [arxiv]2502.13539 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.13539.

- Shuyi Xie, Wenlin Yao, Yong Dai, Shaobo Wang, Donlin Zhou, Lifeng Jin, Xinhua Feng, Pengzhi Wei, Yujie Lin, Zhichao Hu, Dong Yu, Zhengyou Zhang, Jing Nie, and Yuhong Liu. 2023. TencentLLMEval: A Hierarchical Evaluation of Real-World Capabilities for Human-Aligned LLMs. [arxiv]2311.05374 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.05374.

- Benfeng Xu, An Yang, Junyang Lin, Quan Wang, Chang Zhou, Yongdong Zhang, and Zhendong Mao. 2025. ExpertPrompting: Instructing Large Language Models to be Distinguished Experts. [arxiv]2305.14688 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.14688.

- Lanling Xu, Junjie Zhang, Bingqian Li, Jinpeng Wang, Sheng Chen, Wayne Xin Zhao, and Ji-Rong Wen. 2025b. Tapping the Potential of Large Language Models as Recommender Systems: A Comprehensive Framework and Empirical Analysis. [arxiv]2401.04997 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.04997.

- Weicai Yan, Wang Lin, Zirun Guo, Ye Wang, Fangming Feng, Xiaoda Yang, Zehan Wang, and Tao Jin. 2025. Diff-Prompt: Diffusion-Driven Prompt Generator with Mask Supervision. [arxiv]2504.21423 [cs.CV] https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.21423.

- Yakun Yu, Shi-ang Qi, Baochun Li, and Di Niu. 2024. PepRec: Progressive Enhancement of Prompting for Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, editorYaser Al-Onaizan, Mohit Bansal, and Yun-Nung Chen (Eds.). publisherAssociation for Computational Linguistics, addressMiami, Florida, USA,17941–17953. [CrossRef]

- Bowen Zhang, Kun Zhou, Jinyang Wu, Da Yin, Zhen Yang, Zheng Hu, Wayne Xin Zhao, and Ji-Rong Wen. 2024. InstructRecs: Instruction Tuning for Recommender Systems. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01636 (2024). https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.01636.

- Tianyi Zhang, Varsha Kishore, Felix Wu, Kilian Weinberger, and Yoav Artzi. 2019. BERTScore: Evaluating Text Generation with BERT. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09675 (2019).

- Keyu Zhao, Fengli Xu, and Yong Li. 2025. Reason-to-Recommend: Using Interaction-of-Thought Reasoning to Enhance LLM Recommendation. [arxiv]2506.05069 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.05069.

- Yuying Zhao, Yu Wang, Yunchao Liu, Xueqi Cheng, Charu Aggarwal, and Tyler Derr. 2024. Fairness and Diversity in Recommender Systems: A Survey. [arxiv]2307.04644 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.04644.

- Li Zheng, Ruobing Li, and Yongfeng Zhang. 2024. JudgeRec: LLM-as-a-Judge for Evaluating Recommender Systems. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2403.11222 (2024).

- Jeffrey Zhou, Tianjian Lu, Swaroop Mishra, Siddhartha Brahma, Sujoy Basu, Yi Luan, Denny Zhou, and Le Hou. 2023. Instruction-Following Evaluation for Large Language Models. [arxiv]2311.07911 [cs.CL] https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.07911.

- Tao Zhou, Zoltán Kuscsik, Jian-Guo Liu, Matúš Medo, Joseph R Wakeling, and Yi-Cheng Zhang. 2010. Solving the apparent diversity-accuracy dilemma of recommender systems. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. volume107. publisherNational Acad Sciences,4511–4515.

- Yuntao Zhou, Jason Wei, Barret Zoph, et al 2023b. LIMA: Less Is More for Alignment. journalarXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11206 (2023).

- Kaijie Zhu, Qinlin Zhao, Hao Chen, Jindong Wang, and Xing Xie. 2024. PromptBench: A Unified Library for Evaluation of Large Language Models. [arxiv]2312.07910 [cs.AI] https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.07910.

- Shengyao Zhuang, Xueguang Ma, Bevan Koopman, Jimmy Lin, and Guido Zuccon. 2025. Rank-R1: Enhancing Reasoning in LLM-based Document Rerankers via Reinforcement Learning. [arxiv]2503.06034 [cs.IR] https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.06034.

- Cai-Nicolas Ziegler, Sean M McNee, Joseph A Konstan, and Georg Lausen. 2005. Improving recommendation lists through topic diversification. In Proceedings of the 14th international conference on World Wide Web. ACM,22–32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).