Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (i)

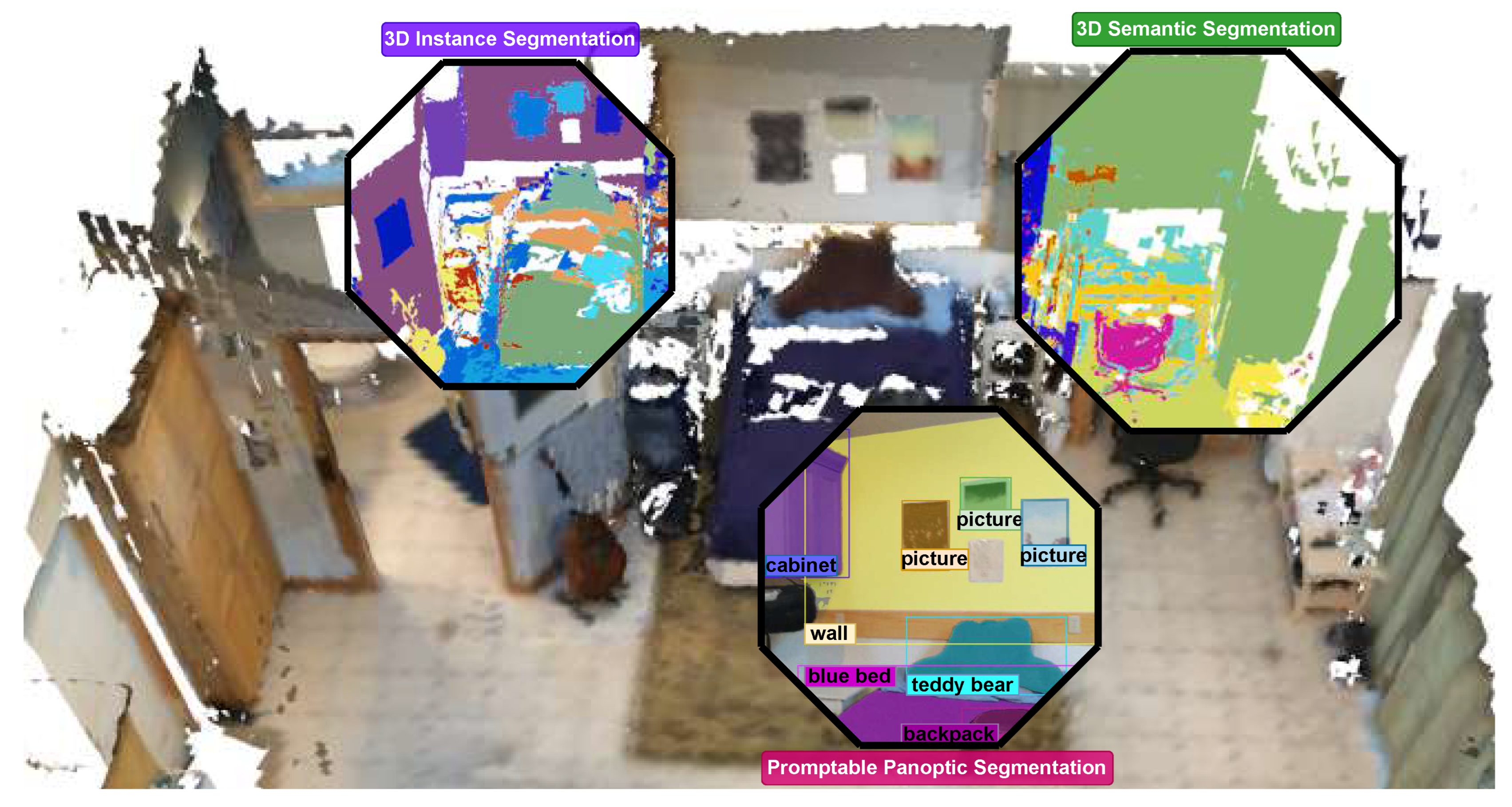

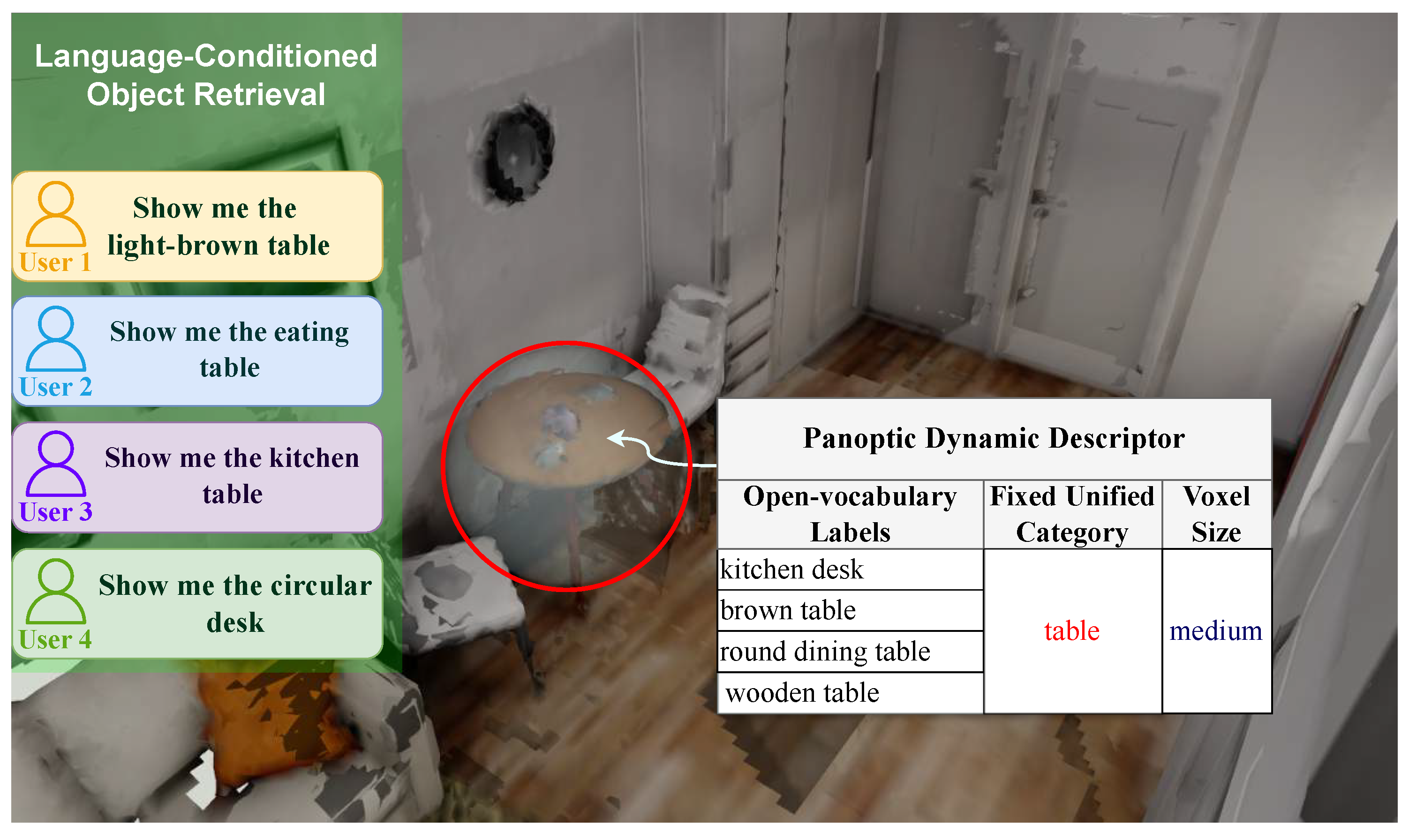

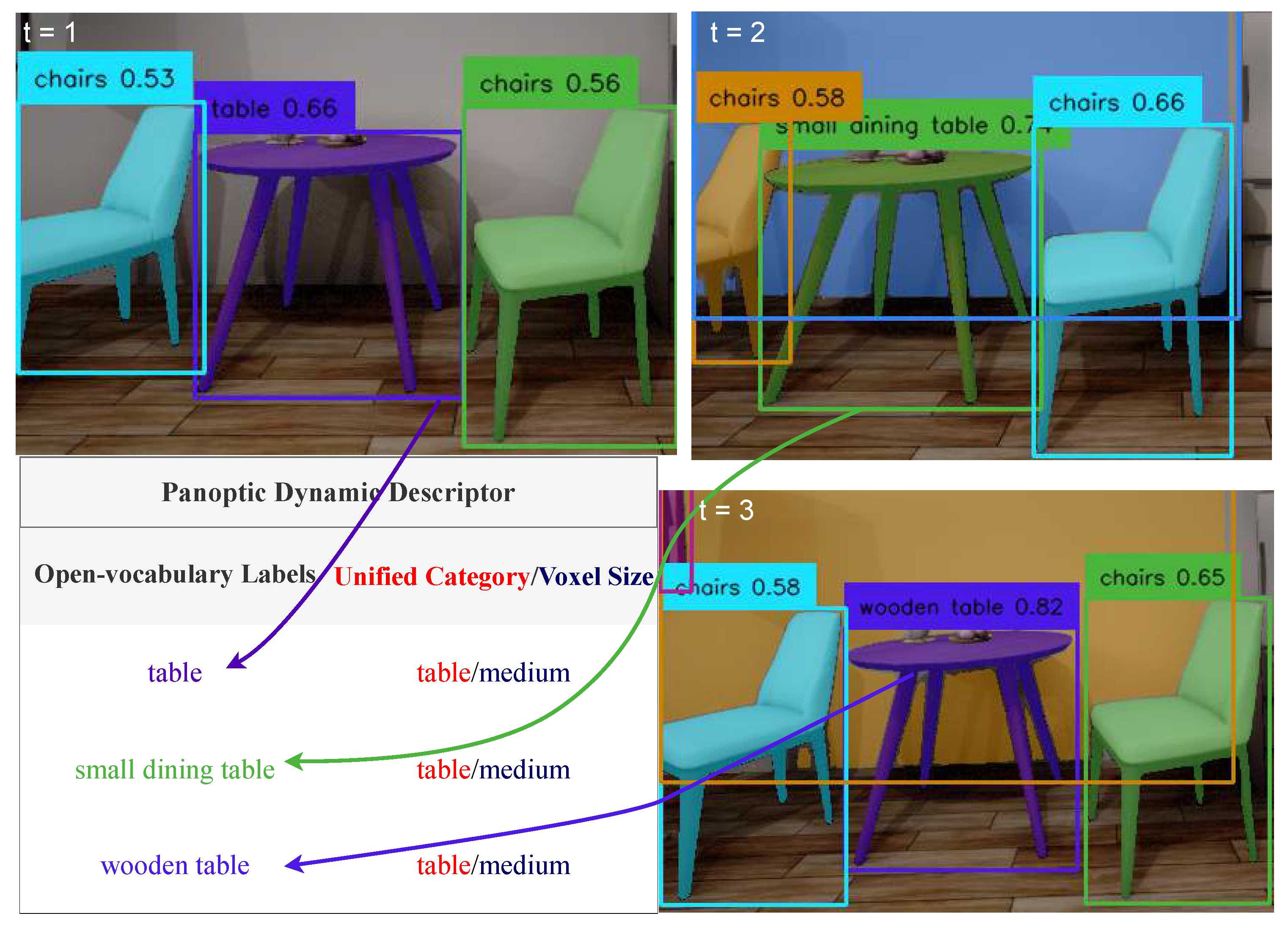

- We introduce a panoptic dynamic descriptor for each unique object that ties together the open-vocabulary elementary descriptors associated with that object across frames. Rather than assigning labels per detection, UPPM aggregates the object open-vocabulary labels produced by vision-language models [22] and post-processed by part-of-speech tagging [23], maps them to a single unified semantic category and size prior, and stores them as the dynamic descriptor (Section 3.2 and Section 3.2.2).

- (ii)

- We build the UPPM pipeline around these dynamic descriptors to produce 3D panoptic maps that are geometrically accurate, semantically consistent, and naturally queryable in language (Section 3).

- (iii)

- We extensively evaluate UPPM across Segmentation-to-Map, Map-to-Map, and Segmentation-to-Segmentation regimes on three different datasets (ScanNet v2, RIO, and Flat), and perform ablations of unified semantics, custom NMS, blurry-frame filtering, and tag usage (Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3, Section 4.5, Section 4.5.1 and Section 4.5.2). Together, these experiments show that dynamic descriptors improve both geometric reconstruction and panoptic quality while enabling downstream language-conditioned tasks such as object retrieval.

2. Related Work

2.1. Open-Vocabulary 3D Mapping

2.2. Open-Set Scene Graphs and Feature Maps

2.3. Foundation Vision-Language Models

3. Method

3.1. Problem Formulation

- Geometric Reconstruction: Generate an accurate 3D reconstruction of the environment represented as a multi-resolution multi-TSDF map .

- Dynamic Labeling with Unified Semantics: Construct the set of dynamic descriptors by first generating elementary descriptors from open-vocabulary cues and then, during the unified panoptic fusion stage, aggregating all elementary descriptors that refer to the same object across frames into a single dynamic descriptor.

3.2. Dynamic Labeling and Segmentation

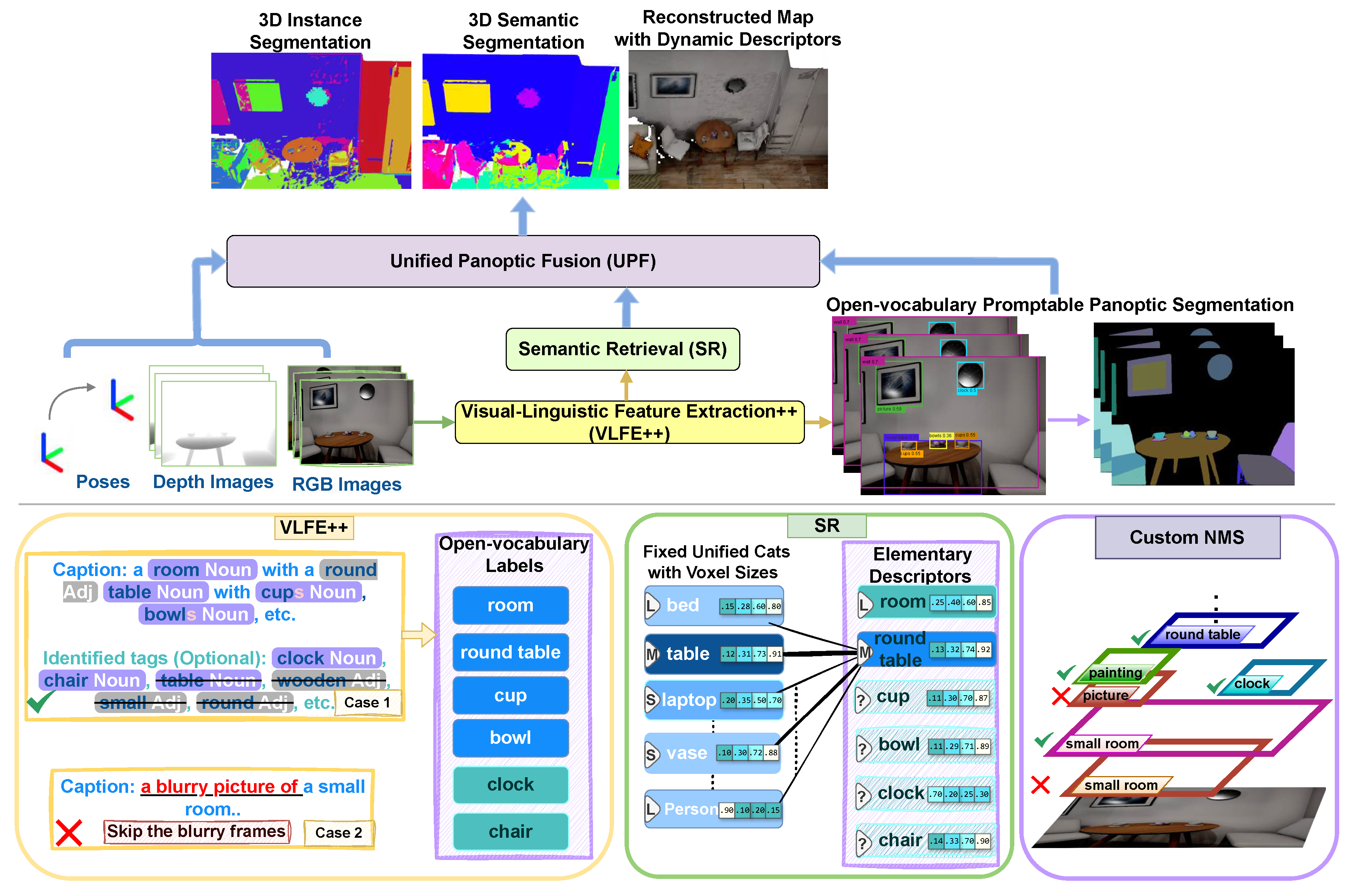

3.2.1. Visual-Linguistic Feature Extraction++ (VLFE++)

- Visual Linguistic Features Extraction (VLFE): a pre-trained vision-language model [22] is employed to produce captions and tags that cover rich semantic descriptions for subsequent processing steps.

- Part-Of-Speech (POS) Tagging: A single-layer perceptron network [23] is applied to extract nouns, noun phrases, and modifiers. The resulting candidate list is passed to the next step.

- Lemmatization: Lemmatization [50] is used to map the derived forms from the candidate list to their normalized base forms (e.g., `apples’ → `apple’), providing canonical labels for retrieval.

3.2.2. Semantic Retrieval (SR)

3.2.3. Open-vocabulary Panoptic Segmentation

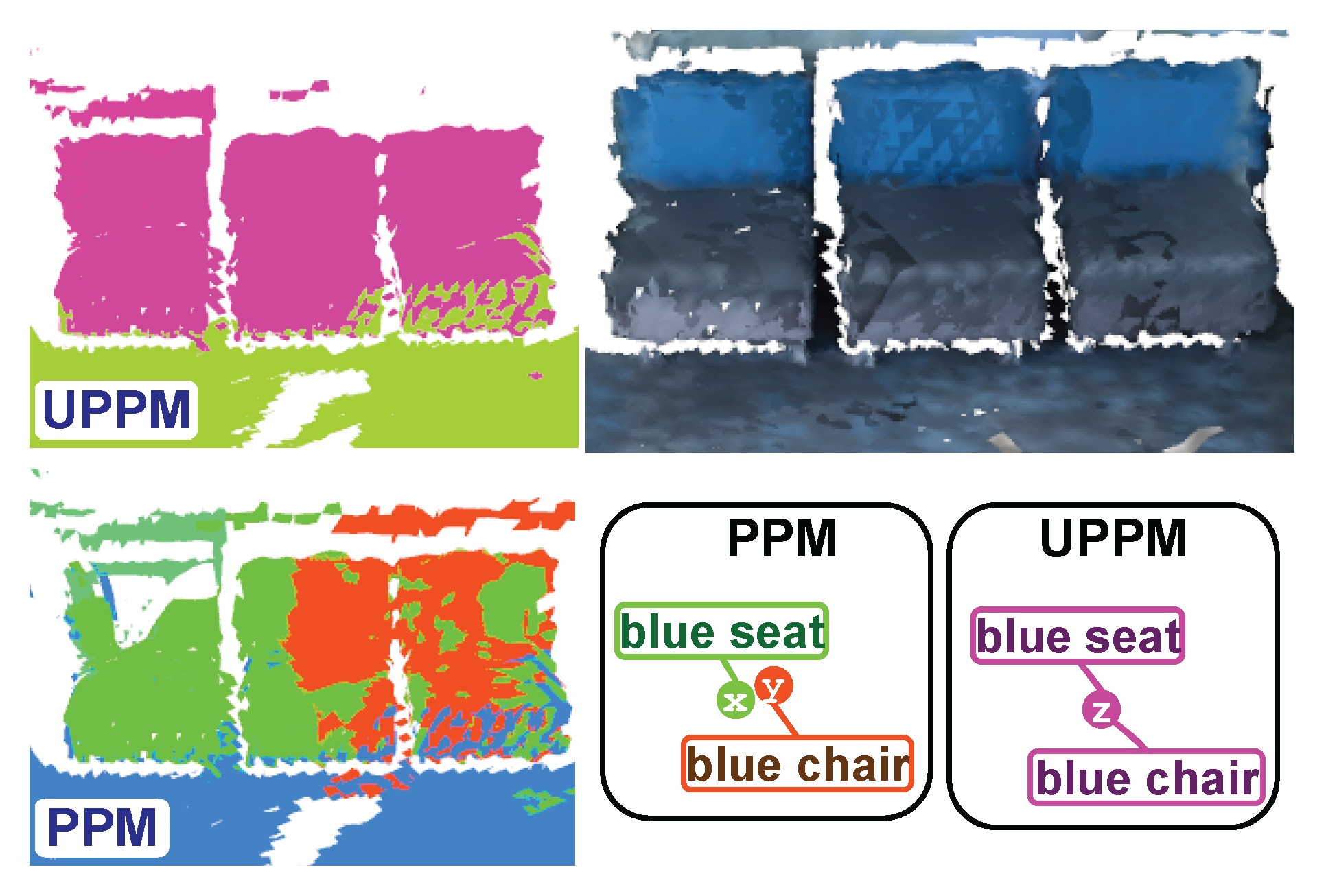

- Prioritizing caption-derived labels: When overlapping bounding boxes have different labels but belong to the same unified category, we prioritize the box whose label originates from the image caption over those derived from the identified tags, as shown in Figure 3. This context-aware selection leverages the richer semantic information provided by captions compared to identified tags [22].

- Standard duplicate removal: For overlapping bounding boxes with identical labels where , we apply conventional suppression based on confidence scores, retaining the box with higher detection confidence.

3.3. Unified Panoptic Fusion (UPF)

4. Results

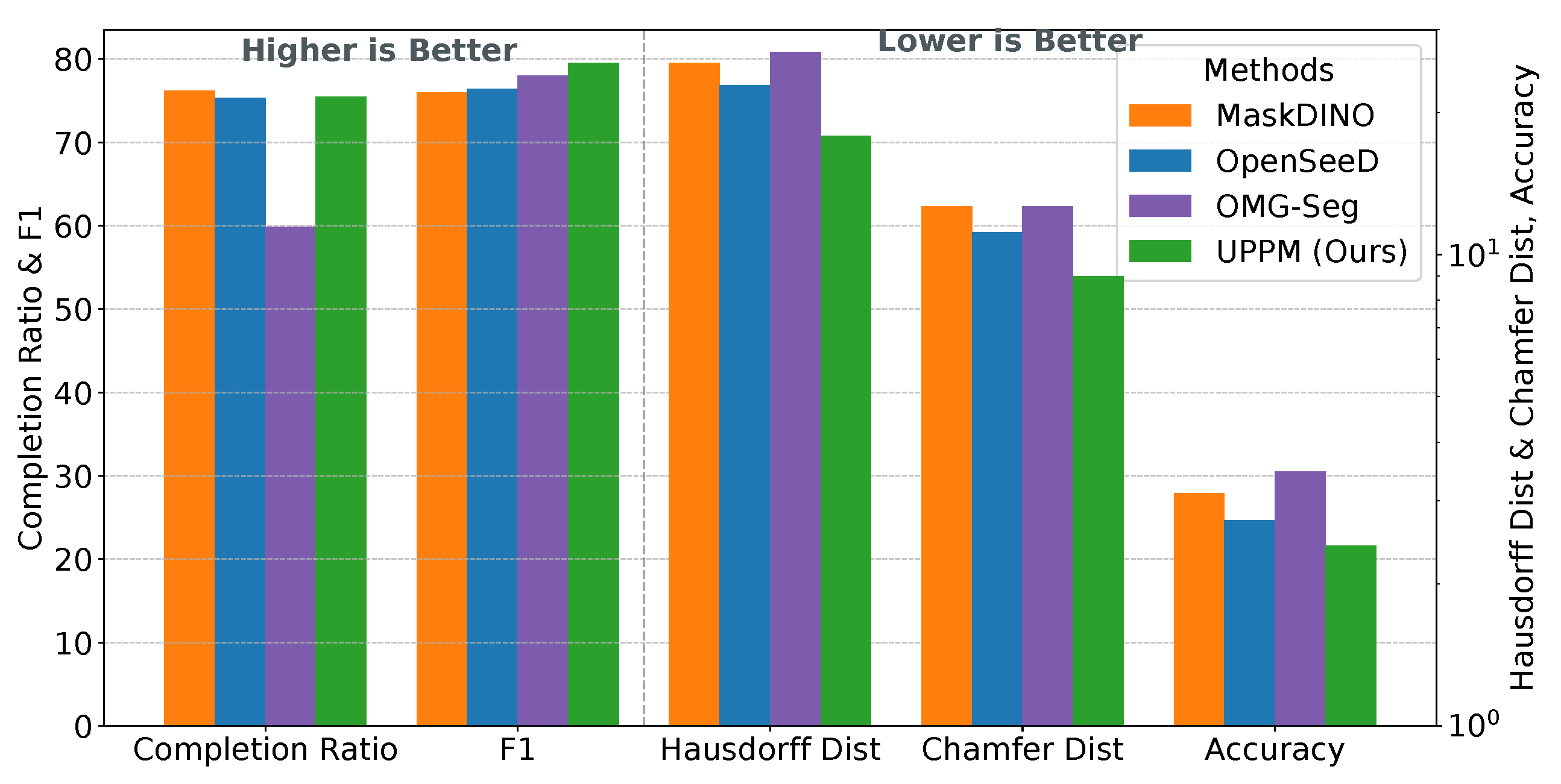

4.1. Segmentation-to-Map Evaluation

| Method | ScanNet v2 | RIO | Flat | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. [cm](↓) |

Acc. [cm](↓) |

Chamf. [cm](↓) |

Haus. [cm](↓) |

C.R. [%](↑) |

Comp. [cm](↓) |

Acc. [cm](↓) |

Chamf. [cm](↓) |

Haus. [cm](↓) |

C.R. [%](↑) |

Comp. [cm](↓) |

Acc. [cm](↓) |

Chamf. [cm](↓) |

Haus. [cm](↓) |

C.R. [%](↑) |

F1 (↑) |

FPS (↑) |

|

| GTS | 1.38 | 2.80 | 9.46 | 18.53 | 82.5 | 1.23 | 1.91 | 10.25 | 21.43 | 77.09 | 1.27 | 0.66 | 3.05 | 5.60 | 71.30 | - | - |

| MaskDINO | 1.81 | 4.40 | 16.76 | 35.65 | 81.21 | 1.28 | 1.97 | 9.16 | 18.55 | 76.63 | 1.26 | 0.68 | 3.08 | 5.58 | 71.69 | 76.01 | 5.95 |

| OpenSeeD | 1.64 | 3.64 | 13.8 | 28.95 | 80.95 | 1.15 | 1.89 | 8.91 | 18.50 | 74.39 | 1.18 | 0.653 | 2.71 | 4.78 | 66.5 | 76.43 | 1.43 |

| OMG-Seg | 1.54 | 4.67 | 16.46 | 36.00 | 76.01 | 0.92 | 2.95 | 9.86 | 21.60 | 34.54 | 1.14 | 0.67 | 2.62 | 4.53 | 68.03 | 77.99 | 1.33 |

| UPPM (Ours) | 1.78 | 3.30 | 12.64 | 25.53 | 81.42 | 1.19 | 1.55 | 5.65 | 10.05 | 74.14 | 1.1 | 0.61 | 2.64 | 4.75 | 70.76 | 79.54 | 2.27 |

4.2. Map-to-Map Evaluation

4.3. Segmentation-to-Segmentation Evaluation

4.4. Ablation Studies

4.5. Unified Semantics

4.5.1. Non-Maximum Suppression

| Method | Precision [%](↑) | Recall [%](↑) | F1-Score [%](↑) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMS [52] | 91.3 | 63.64 | 75.0 |

| Custom NMS (Ours) | 94.6 | 100.0 | 97.22 |

| Method | Chamfer dist. [cm](↓) | Comp. Ratio [<5cm %](↑) |

|---|---|---|

| PPM | 2.79 | 70.38 |

| PPM w/o NMS | 2.79 | 62.11 |

| Enhancement | 0.00 | +8.27 % |

4.5.2. Blurry Frames Filtering

4.5.3. Identified Tags

5. Conclusions

References

- McCormac, J.; Handa, A.; Davison, A.; Leutenegger, S. Semanticfusion: Dense 3d semantic mapping with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2017, pp. 4628–4635. [CrossRef]

- Salas-Moreno, R.F.; Newcombe, R.A.; Strasdat, H.; Kelly, P.H.; Davison, A.J. Slam++: Simultaneous localisation and mapping at the level of objects. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2013, pp. 1352–1359. [CrossRef]

- Narita, G.; Seno, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Kaji, Y. Panopticfusion: Online volumetric semantic mapping at the level of stuff and things. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2019, pp. 4205–4212.

- Sun, Q.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, F. DKB-SLAM: Dynamic RGB-D Visual SLAM with Efficient Keyframe Selection and Local Bundle Adjustment. Robotics 2025, 14, 134.

- Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Ni, L.M.; Shum, H.Y. Mask dino: Towards a unified transformer-based framework for object detection and segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 3041–3050.

- Zong, Z.; Song, G.; Liu, Y. Detrs with collaborative hybrid assignments training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 6748–6758.

- Zhu, Y.; Xiao, N. Simple Scalable Multimodal Semantic Segmentation Model. Sensors 2024, 24.

- Zhou, F.; Shi, H. HyPiDecoder: Hybrid Pixel Decoder for Efficient Segmentation and Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2025, pp. 22100–22109.

- Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Zou, X.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L. A simple framework for open-vocabulary segmentation and detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 1020–1031.

- Li, X.; Yuan, H.; Li, W.; Ding, H.; Wu, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Loy, C.C. OMG-Seg: Is one model good enough for all segmentation? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 27948–27959.

- Ghiasi, G.; Gu, X.; Cui, Y.; Hartwig, A.; He, Z.; Khademi, M.; Le, Q.V.; Lin, T.Y.; Susskind, J.; et al. Open-vocabulary Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 20645–20655.

- Liu, M.; Ji, J.; Zheng, Z.; Han, K.; Shan, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Gao, P.; Zhang, H.; et al. OpenSeg: Panoramic Open-Vocabulary Scene Parsing with Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 17006–17016.

- Li, J.; Ding, H.; Tian, X.; Li, X.; Long, X.; Yuan, Z.; Li, J. OVSeg: Label-Free Open-Vocabulary Training for Text-to-Region Recitation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023.

- Chen, H.; Blomqvist, K.; Milano, F.; Siegwart, R. Panoptic Vision-Language Feature Fields. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 2144–2151. [CrossRef]

- OpenVox Authors. OpenVox: Real-time Instance-level Open-Vocabulary Probabilistic Voxel Representation. arXiv preprint 2024. Available online: arXiv (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Jatavallabhula, K.M.; Kuwajerwala, A.; Gu, Q.; Omama, M.; Chen, T.; Maalouf, A.; Li, S.; Iyer, G.S.; Keetha, N.V.; Tewari, A.; et al. ConceptFusion: Open-set Multimodal 3D Mapping. In Proceedings of the ICRA2023 Workshop on Pretraining for Robotics (PT4R), 2023.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 8748–8763.

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 9650–9660.

- Gu, Q.; Kuwajerwala, A.; Morin, S.; Jatavallabhula, K.M.; Sen, B.; Agarwal, A.; Rivera, C.; Paul, W.; Ellis, K.; Chellappa, R.; et al. Conceptgraphs: Open-vocabulary 3d scene graphs for perception and planning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 5021–5028.

- Clio Authors. Clio: Language-Guided Object Discovery in 3D Scenes. arXiv preprint 2024. Available online: arXiv (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Peng, S.; Genova, K.; Jiang, C.; Tagliasacchi, A.; Pollefeys, M.; Funkhouser, T.; et al. Openscene: 3d scene understanding with open vocabularies. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 815–824.

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Tian, W.; Feng, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L. Tag2Text: Guiding Vision-Language Model via Image Tagging. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2024.

- Honnibal, M. A Good Part-of-Speech Tagger in about 200 Lines of Python. https://explosion.ai/blog/part-of-speech-pos-tagger-in-python, 2013.

- Schmid, L.; Delmerico, J.; Schönberger, J.L.; Nieto, J.; Pollefeys, M.; Siegwart, R.; Cadena, C. Panoptic multi-tsdfs: a flexible representation for online multi-resolution volumetric mapping and long-term dynamic scene consistency. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 8018–8024.

- Hu, T.; Jiao, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, M. Dhp-mapping: A dense panoptic mapping system with hierarchical world representation and label optimization techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1101–1107.

- McCormac, J.; Clark, R.; Bloesch, M.; Davison, A.; Leutenegger, S. Fusion++: Volumetric object-level slam. In Proceedings of the 2018 international conference on 3D vision (3DV). IEEE, 2018, pp. 32–41.

- Rosinol, A.; Abate, M.; Chang, Y.; Carlone, L. Kimera: an open-source library for real-time metric-semantic localization and mapping. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1689–1696.

- Mahmoud, A.; Atia, M. Improved visual SLAM using semantic segmentation and layout estimation. Robotics 2022, 11, 91. [CrossRef]

- Laina, S.B.; Boche, S.; Papatheodorou, S.; Schaefer, S.; Jung, J.; Leutenegger, S. FindAnything: Open-Vocabulary and Object-Centric Mapping for Robot Exploration in Any Environment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.08603 2025.

- Martins, T.B.; Oswald, M.R.; Civera, J. Open-vocabulary online semantic mapping for SLAM. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2025. [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Khorrami, F. RAZER: Robust Accelerated Zero-Shot 3D Open-Vocabulary Panoptic Reconstruction with Spatio-Temporal Aggregation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.15373 2025.

- Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, S.; Ren, B.; Yue, Y.; Yang, Y. OpenGS-Fusion: Open-Vocabulary Dense Mapping with Hybrid 3D Gaussian Splatting for Refined Object-Level Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.01150 2025.

- Jiang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Song, J. DualMap: Online Open-Vocabulary Semantic Mapping for Natural Language Navigation in Dynamic Changing Scenes. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2025, 10, 12612–12619. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Ye, Z.; Yu, J.; Tang, J.; Yi, T.; Dong, Y.; Wang, J.; Cui, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. MR-COGraphs: Communication-Efficient Multi-Robot Open-Vocabulary Mapping System via 3D Scene Graphs. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2025, 10, 5713–5720. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Ülger, O.; Nejadasl, F.K.; Gevers, T.; Oswald, M.R. 3D-AVS: LiDAR-based 3D Auto-Vocabulary Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2025, pp. 8910–8920.

- Zhang, C.; Delitzas, A.; Wang, F.; Zhang, R.; Ji, X.; Pollefeys, M.; Engelmann, F. Open-vocabulary functional 3d scene graphs for real-world indoor spaces. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, 2025, pp. 19401–19413.

- LangSplat Authors. LangSplat: Language-Conditioned 3D Gaussian Splatting. arXiv preprint 2024. Available online: arXiv (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Bayesian-Fields Authors. Bayesian-Fields: Probabilistic 3D Scene Understanding with Open-Vocabulary Queries. arXiv preprint 2023. Available online: arXiv (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- OpenGaussian Authors. OpenGaussian: Open-Vocabulary 3D Gaussian Splatting. arXiv preprint 2024. Available online: arXiv (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Werby, A.; Huang, C.; Büchner, M.; Valada, A.; Burgard, W. Hierarchical open-vocabulary 3d scene graphs for language-grounded robot navigation. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Vision-Language Models for Navigation and Manipulation at ICRA 2024, 2024.

- Awais, M.; Naseer, M.; Khan, S.; Anwer, R.M.; Cholakkal, H.; Shah, M.; Yang, M.H.; Khan, F.S. Foundation models defining a new era in vision: a survey and outlook. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2023, pp. 4015–4026.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08485 2023.

- Lu, S.; Chang, H.; Jing, E.P.; Boularias, A.; Bekris, K. Ovir-3d: Open-vocabulary 3d instance retrieval without training on 3d data. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 1610–1620.

- Takmaz, A.; Fedele, E.; Sumner, R.W.; Pollefeys, M.; Tombari, F.; Engelmann, F. OpenMask3D: Open-Vocabulary 3D Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2023.

- Liu, S.; Zeng, Z.; Ren, T.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Jiang, Q.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Su, H.; et al. Grounding dino: Marrying dino with grounded pre-training for open-set object detection. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2024, pp. 38–55.

- Song, K.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Lu, J.; Liu, T.Y. Mpnet: Masked and permuted pre-training for language understanding. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 16857–16867.

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Ma, J.; Li, Z.; Luo, Z.; Xie, Y.; Qin, Y.; Luo, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; et al. Recognize anything: A strong image tagging model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 1724–1732.

- Caesar, H.; Uijlings, J.; Ferrari, V. Coco-stuff: Thing and stuff classes in context. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 1209–1218.

- Fellbaum, C. WordNet. In Theory and applications of ontology: computer applications; Springer, 2010; pp. 231–243.

- Johnson, J.; Douze, M.; Jégou, H. Billion-scale similarity search with gpus. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2019, 7, 535–547. [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2014, pp. 580–587.

- Dai, A.; Chang, A.X.; Savva, M.; Halber, M.; Funkhouser, T.; Nießner, M. Scannet: Richly-annotated 3d reconstructions of indoor scenes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 5828–5839.

- Wald, J.; Avetisyan, A.; Navab, N.; Tombari, F.; Nießner, M. Rio: 3d object instance re-localization in changing indoor environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2019, pp. 7658–7667.

| Method | Acc. [cm]↓ | Comp. [cm]↓ | Chamfer-L1 [cm]↓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kimera | 0.76 | 6.48 | 3.62 |

| Panmap | 0.86 | 7.63 | 4.24 |

| DHP | 0.73 | 6.58 | 3.65 |

| UPPM (Ours) | 0.61 | 1.1 | 1.71 |

| Method | PQ ↑ | RQ ↑ | SQ ↑ | mAP-(0.3) ↑ | mAP-(0.4) ↑ | mAP-(0.5) ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaskDINO | 0.406 | 0.470 | 0.851 | 0.546 | 0.516 | 0.470 |

| OMG-Seg | 0.164 | 0.200 | 0.498 | 0.287 | 0.244 | 0.200 |

| Detectron2 | 0.343 | 0.432 | 0.787 | 0.499 | 0.473 | 0.432 |

| UPPM (Ours) | 0.414 | 0.475 | 0.845 | 0.549 | 0.521 | 0.475 |

| Method | Comp. | Acc. | Chamf. |

|---|---|---|---|

| [cm](↓) | [cm](↓) | [cm](↓) | |

| UPPM | 1.1 | 0.61 | 2.64 |

| UPPM with tags | 1.2 | 0.63 | 2.77 |

| PPM | 1.18 | 0.65 | 2.79 |

| PPM with tags | 1.22 | 0.66 | 2.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).