Submitted:

30 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

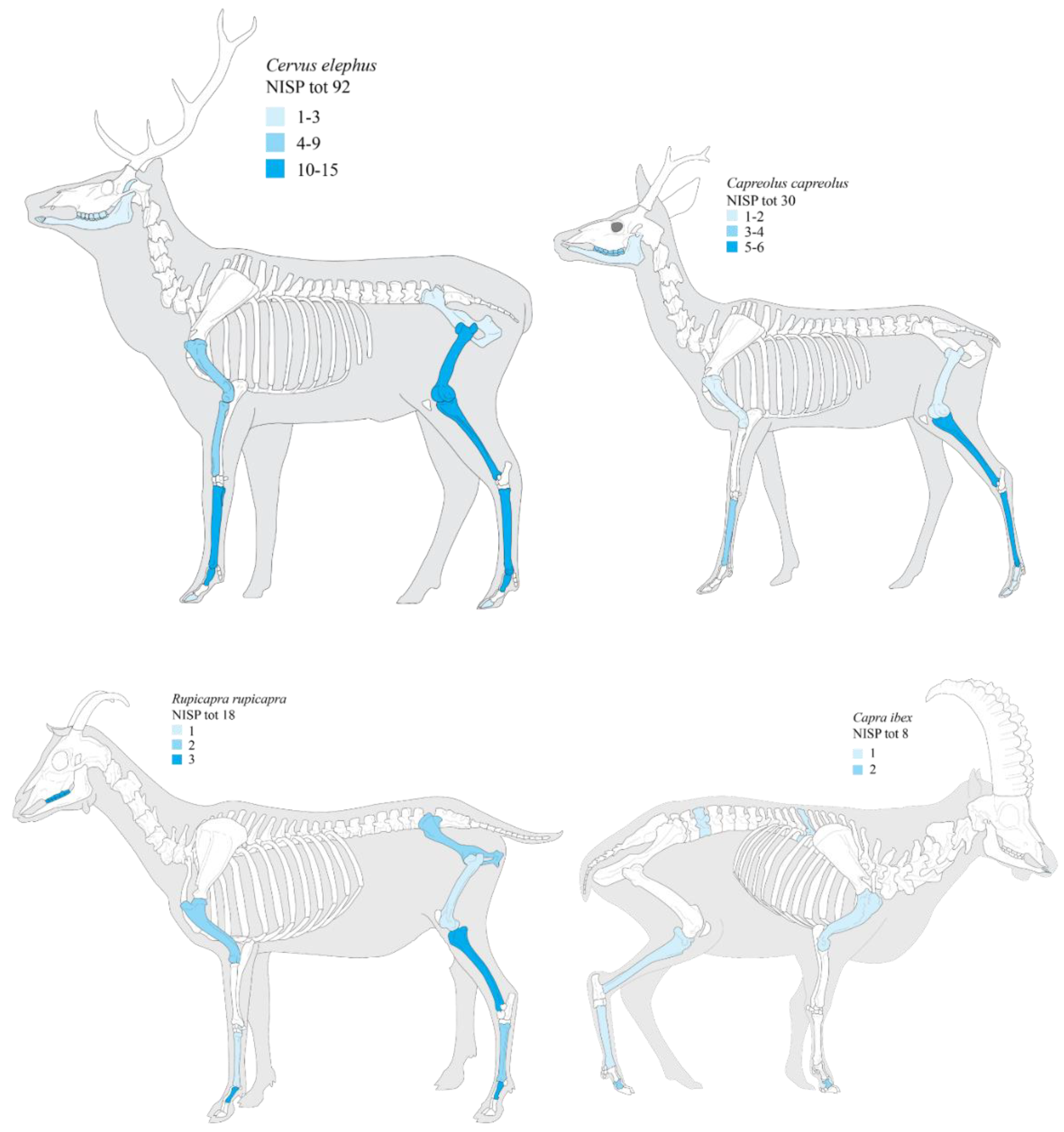

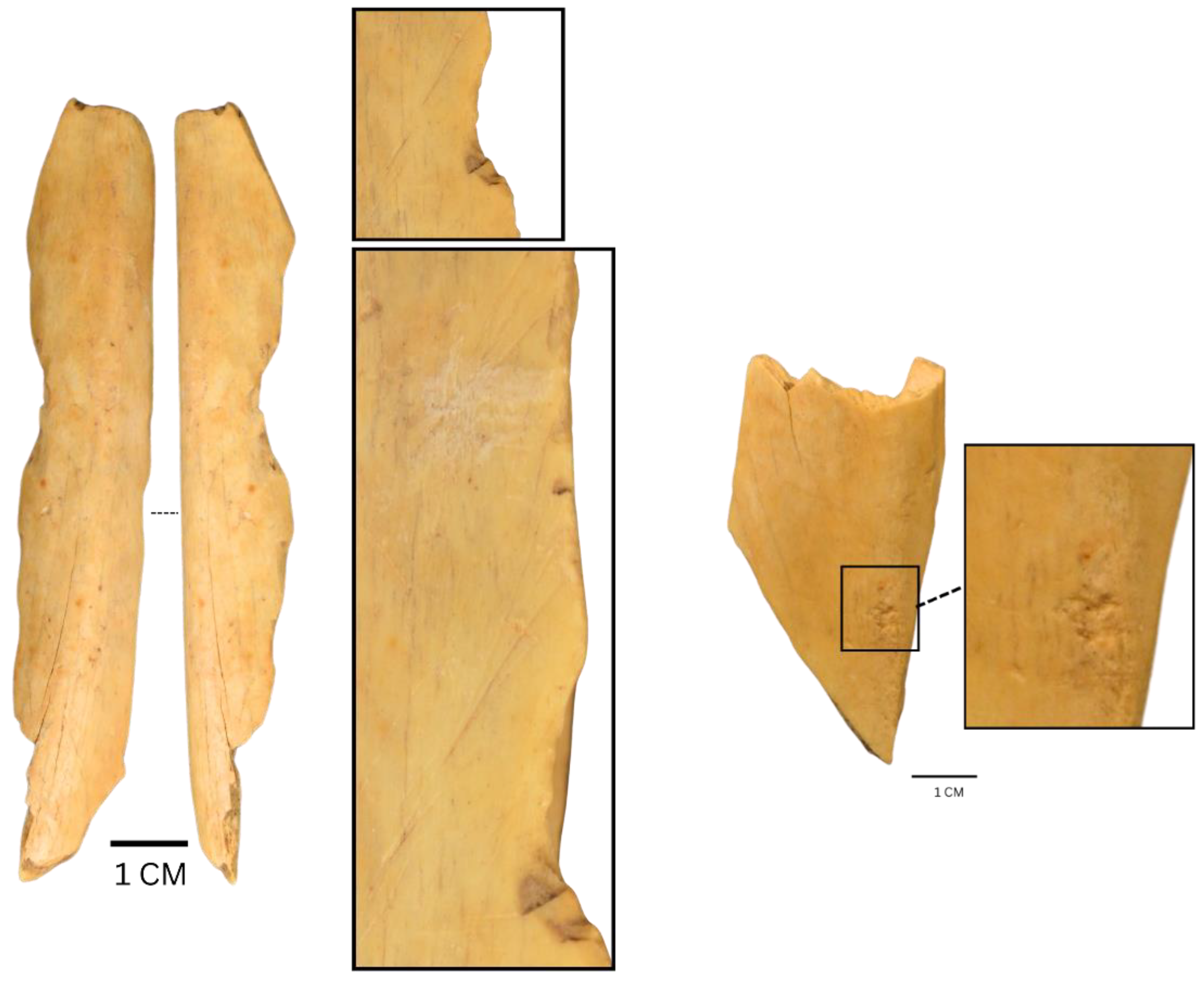

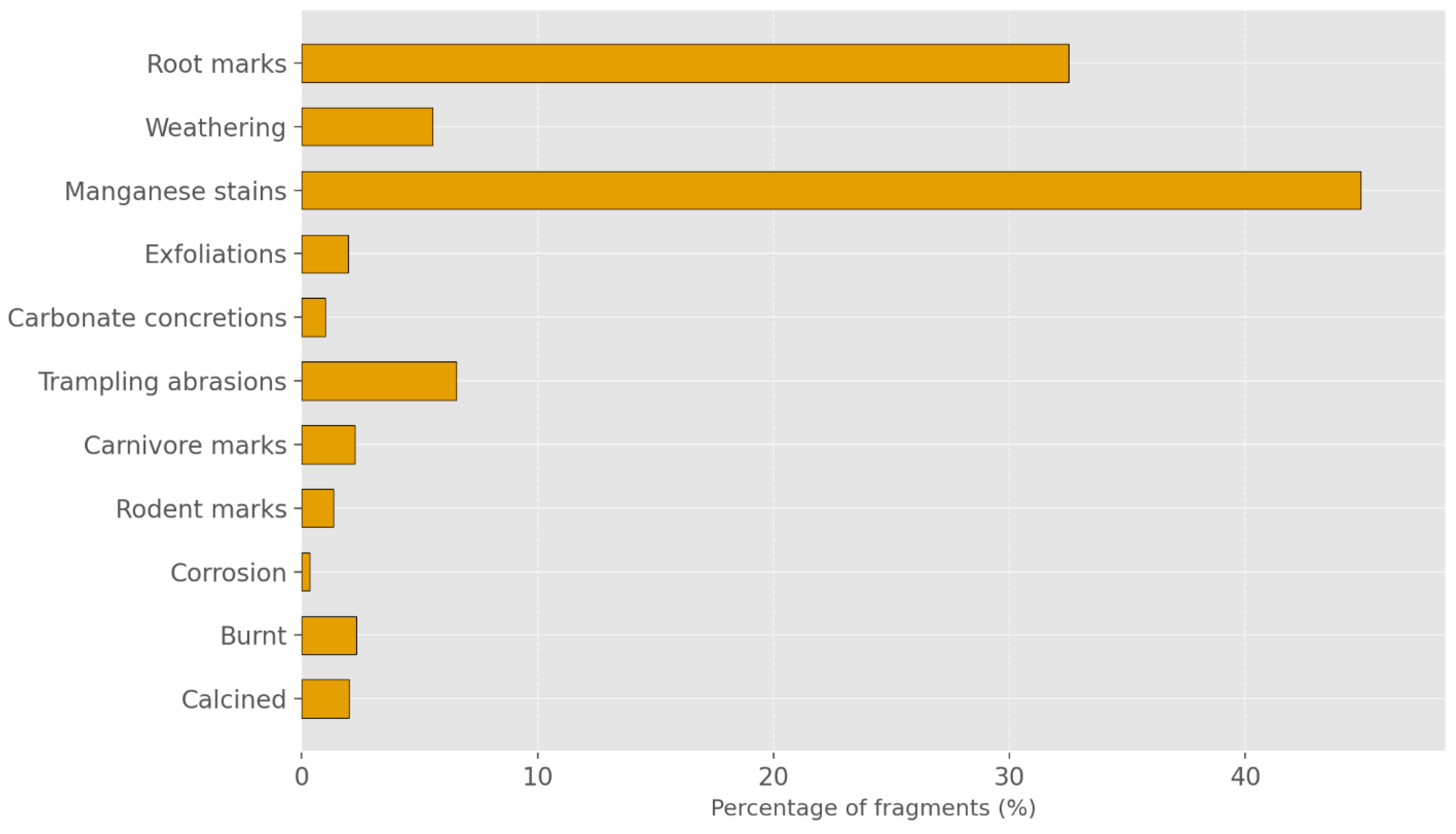

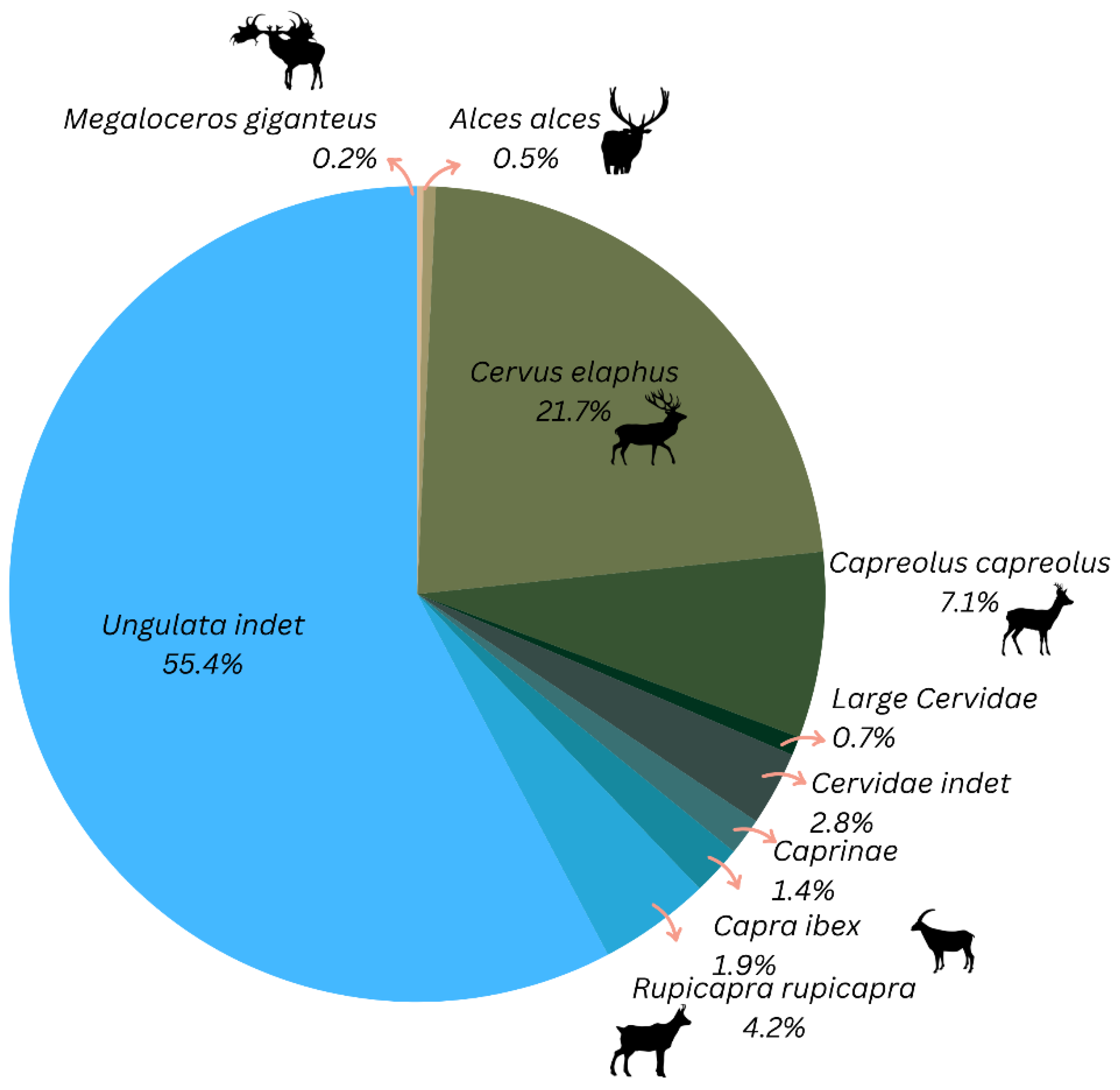

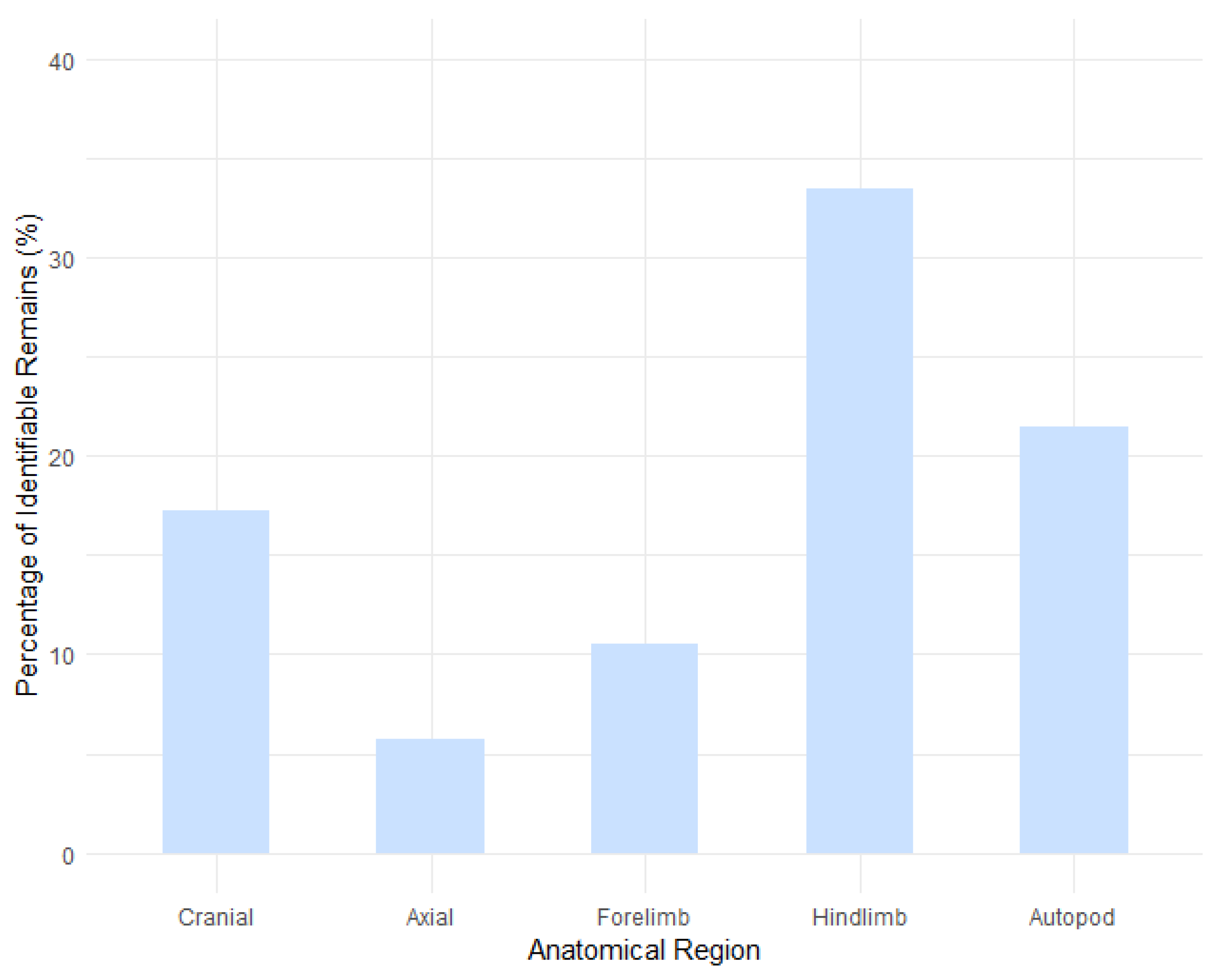

This study presents a zooarchaeological and taphonomic analysis of the remaining portion of the Mousterian faunal assemblage from Unit A9 at Grotta di Fumane (northeastern Italy), offering refined insights into Neanderthal subsistence behaviour during Marine Isotope Stage 3. Building on the previously published analysis of the principal portion of the assemblage [1], the new data reaffirm a subsistence strategy focused on selective transport and intensive on-site processing of high-utility carcass components. The ungulate assemblage—dominated by Cervus elaphus and Capreolus capreolus, with additional contributions from Rupicapra rupicapra and Capra ibex—characterised by the dominance of hindlimb elements, moderate cranial representation, and a pronounced scarcity of axial remains. These patterns indicate that carcass reduction commenced at kill sites, where low-yield trunk segments were removed, while high-nutritional-value limb portions were preferentially transported to the cave for secondary processing. Taphonomic indicators, including abundant cut marks, percussion notches, and extensive bone fragmentation, demonstrate systematic defleshing, marrow extraction, and possible grease rendering within the cave, activities that were spatially associated with combustion features. Occasional cranial transport suggests targeted acquisition of high-fat tissues such as brains and tongue, behaviour consistent with cold-climate optimisation strategies documented in both ethnographic and experimental contexts. Collectively, the evidence indicates that Unit A9 served as a residential locus embedded within a logistically organised mobility system, where carcass processing, resource exploitation, and lithic activities were closely integrated. These findings reinforce the broader picture of late Neanderthals as adaptable and behaviourally sophisticated foragers capable of strategic planning and efficient exploitation of ungulate prey within the dynamic environments of northern Italy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Zooarchaeological and Taphonomical Frame of Reference

3. Results

3.1. Zooarchaeology and Taphonomy

3.2. Exploitation of Carcasses

3.3. Carcass Representation Index

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Romandini, M.; Nannini, N.; Tagliacozzo, A.; Peresani, M. The ungulate assemblage from layer A9 at Grotta di Fumane, Italy: A zooarchaeological contribution to the reconstruction of Neanderthal ecology. Quaternary International 2014, 337, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpiano, D.; Zupancich, A.; Peresani, M. Innovative Neanderthals: Results from an integrated analytical approach applied to backed stone tools. Journal of Archaeological Science 2019, 110, 105011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpiano, D.; Heasley, K.; Peresani, M. Assessing Neanderthal land use and lithic raw material management in Discoid technology. Journal of Anthropological Sciences 2018, 96, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcazzani, D.; Miller, C.E.; Ligouis, B.; Duches, R.; Conard, N.J.; Peresani, M. Middle and Upper Paleolithic occupations of Fumane Cave (Italy): A geoarchaeological investigation of the anthropogenic features. Journal of Anthropological Sciences 2023, 101, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpiano, D.; Gravina, B.; Peresani, M. Back(s) to basics: The concept of backing in stone tool technologies for tracing hominin technical innovations. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peresani, M. Inspecting human evolution from a cave. Late Neanderthals and early sapiens at Grotta di Fumane: present state and outlook. Journal of Anthropological Sciences 2022, 100, 71–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, J.M.; dalla Valle, C.; Cremaschi, M.; Peresani, M. Reconstruction of the Neanderthal and Modern Human landscape and climate from the Fumane cave sequence using small-mammal assemblages. Quaternary Science Reviews 2015, 128, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehl, M.; Marcazzan, D.; Miller, C.E.; Falcucci, A.; Duches, R.; Peresani, M. The Upper Sedimentary Sequence of Grotta di Fumane, Northern Italy: A Micromorphological Approach to Study Imprints of Human Occupation and Paleoclimate Change. Geoarchaeology 2025, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Romero, L.; Govoni, M.; Marcazzan, D.; Delpiano, D.; Nannini, N.; Martellotta, E.F.; Duches, R.; Peresani, M. Intra-site Organization of the Repeated Neanderthal Occupation of Unit A9, Grotta di Fumane. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 2025, 32, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazzi, S.; Bailey, S.E.; Peresani, M.; Mannino, M.A.; Romandini, M.; Richards, M.P.; Hublin, J.-J. Middle Paleolithic and Uluzzian human remains from Fumane Cave, Italy. Journal of Human Evolution 2014, 70, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannini, N. Studio archeozoologico del complesso faunistico delle unità musteriane A8 e A9. Approfondimenti tafonomici sulle modalità di sussistenza degli ultimi discoidi di Grotta di Fumane (VR). PhD Thesis, University of Ferrara, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- France, D.L. Human and Nonhuman Bone Identification: A Color Atlas. CRC Press: New York, USA, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J.M. The Archaeology of Animals. Routledge Press: London, UK, 1987. [CrossRef]

- Lyman, R.L. Vertebrate Taphonomy. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 1–524.

- Broughton, J.M. Zooarchaeology. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed, 2015; pp. 849–853.

- Reitz, E.J.; Wing, E.S. Cambridge Manual of Zooarchaeology. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008.

- Bunn, H.T.; Bartram, L.E.; Kroll, E.M. Variability in bone assemblage formation from Hadza hunting, scavenging, and carcass processing. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 1988, 7, 412–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J. Delayed implantation in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). Reproduction 1974, 39, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariezkurrena, K. Contribución al conocimiento del desarrollo de la dentición y el esqueleto postcraneal de Cervus elaphus. Munibe 1983, 149–202. [Google Scholar]

- D’Errico, F.; Vanhaeren, M. Criteria for identifying red deer (Cervus elaphus) age and sex from their canines. Journal of Archaeological Science 2002, 29, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillson, S. Teeth. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005.

- Silver, I. The ageing of domestic animals. In Science in Archaeology: A Survey of Progress and Research; Brothwell, D., Higgs, E., Clark, G., Eds.; Praeger Press: New York, USA, 1969; pp. 250–268. [Google Scholar]

- Bunn, H.T.; Pickering, T.R. Methodological recommendations for ungulate mortality analyses in paleoanthropology. Quaternary Research 2010, 74, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermehl, K.H. Die Altersbestimmung Bei Hausund Labortieren, 1975.

- Grayson, D.K. Quantitative Zooarchaeology: Topics in the Analysis of Archaeological Faunas. Academic Press: Orlando, USA, 1984.

- Bökönyi, S. A New Method for the Determination of the Number of Individuals in Animal Bone Material. American Journal of Archaeology 1970, 74, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrensmeyer, A.K. Taphonomic and ecologic information from bone weathering. Paleobiology 1978, 4, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Jalvo, Y.; Andrews, P. Atlas of Taphonomic Identifications. Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2016.

- Brain, C.K. Bone weathering and the problem of bone pseudo-tools. South African Journal of Science 1967, 63, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Shipman, P. Life History of a Fossil: An Introduction to Taphonomy and Paleoecology. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, USA, 1981.

- Fisher, J.W. Bone surface modifications in zooarchaeology. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 1995, 2, 7–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binford, L.R. Bones: Ancient Men and Modern Myth. Academic Press: New York, USA, 1981.

- Brain, C.K. The Hunters or the Hunted? An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA, 1981.

- Blumenschine, R.J.; Selvaggio, M.M. Percussion marks on bone surfaces as a new diagnostic of hominid behaviour. Nature 1988, 333, 763–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldo, S.D.; Blumenschine, R.J. A Quantitative Diagnosis of Notches Made by Hammerstone Percussion and Carnivore Gnawing on Bovid Long Bones. American Antiquity 1994, 59, 724–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenschine, R.J. Percussion marks, tooth marks, and experimental determinations of the timing of hominid and carnivore access to long bones at FLK Zinjanthropus, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Journal of Human Evolution 1995, 27, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Piqueras, A. The use of tooth pits to identify carnivore taxa in tooth-marked archaeofaunas and their relevance to reconstruct hominid carcass processing behaviours. Journal of Archaeological Science 2003, 30, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, R.; Shipman, P. Cutmarks made by stone tools on bones from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Nature 1981, 291, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipman, P.; Rose, J. Early hominid hunting, butchering, and carcass-processing behaviors: Approaches to the fossil record. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 1983, 2, 57–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, R.L. Quantitative Paleozoology. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008.

- Costamagno, S.; Soulier, M.-C.; Val, A.; Chong, S. The reference collection of cutmarks. Palethnologie 2019, 1, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenschine, R.J.; Selvaggio, M.M. On the marks of marrow bone processing by hammerstones and hyaenas: their anatomical patterning and archaeological implications. In Cultural Beginnings: Approaches to Understanding Early Hominid Life-Ways in the African Savanna; Clark, J.D., Ed.; Dr Rudolf Habelt GmbH: Bonn, Germany, 1991; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Blasco, R.; Rosell, J.; Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Lozano, S.; Pastó, I.; Riba, D.; Vaquero, M.; Peris, J.F.; Arsuaga, J.L.; de Castro, J.M.B.; Carbonell, E. Learning by Heart: Cultural patterns in the faunal processing sequence during the Middle Pleistocene. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettese, D.; Daujeard, C.; Blasco, R.; Borel, A.; Caceres, I.; Moncel, M.H. Neanderthal long bone breakage process: Standardized or random patterns? The example of Abri du Maras (Southeastern France, MIS 3). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2017, 13, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, P.; Mahieu, E. Breakage patterns of human long bones. Journal of Human Evolution 1991, 21, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outram, A.K. A new approach to identifying bone marrow and grease exploitation: Why the “indeterminate” fragments should not be ignored. Journal of Archaeological Science 2001, 28, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunwald, A.M. Analysis of fracture patterns from experimentally marrow-cracked frozen and thawed cattle bones. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2016, 8, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coil, R.; Tappen, M.; Yezzi-Woodley, K. New analytical methods for comparing bone fracture angles: A controlled study of hammerstone and hyena (Crocuta crocuta) long bone breakage. Archaeometry 2017, 59, 900–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiner, M.C.; Kuhn, S.L.; Weiner, S.; Bar-Yosef, O. Differential burning, recrystallization, and fragmentation of archaeological bone. Journal of Archaeological Science 1995, 22, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.L. Caribou. In Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation; Feldhamer, G.A., Thompson, B.C., Chapman, J.A., Eds.; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, USA, 2003; pp. 965–997. [Google Scholar]

- Mysterud, A. Diet overlap among ruminants in Fennoscandia. Oecologia 2000, 124, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yravedra, J.; Cobo-Sánchez, L. Neanderthal exploitation of ibex and chamois in southwestern Europe. Journal of Human Evolution 2015, 78, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Haws, J.A.; Jones, E.L. Late Neanderthal subsistence and foraging mobility at Lapa do Picareiro: a zooarchaeological and taphonomic analysis of Level JJ. Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendu, W.; Costamagno, S.; Meignen, L.; Soulier, M.-C. Monospecific faunal spectra in Mousterian contexts: Implications for social behavior. Quaternary International 2012, 247, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal-García, H.; Rey-Rodríguez, I.; de Lombera-Hermida, A.; Díaz-Rodríguez, M.; Fernández-Rodríguez, C.; Rodríguez-Álvarez, X.P.; Valcarce, R.F. Landscape and subsistence in NW Iberia during the Middle Palaeolithic (MIS3): Faunal analysis of Cova Eirós (Triacastela, Galicia, Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2025, 64, 105149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yravedra, J.; Estaca-Gómez, V.; Grandal-d’Anglade, A.; Pinto-Llona, A.C. Neanderthal subsistence strategies: new evidence from the Mousterian Level XV of the Sopeña rock shelter (Asturias, northern Spain). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 2024, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peresani, M.; Chrzavzez, J.; Danti, A.; De March, M.; Duches, R.; Gurioli, F.; Muratori, S.; Romandini, M.; Trombino, L.; Tagliacozzo, A. Fire-places, frequentations and the environmental setting of the final Mousterian at Grotta di Fumane: a report from the 2006–2008 research. In Quartär: International Yearbook for Ice Age and Stone Age Research; Müller, W., Valentin Eriksen, B., Street, M., Weniger, G.-C., Eds.; Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH: Rahden, Germany, 2011; pp. 131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Romandini, M. Analisi archeozoologica, tafonomica, paleontologica e spaziale dei livelli Uluzziani e tardo-Musteriani della Grotta di Fumane (VR). Variazioni e continuità strategico-comportamentali umane in Italia Nord Orientale: i casi di Grotta del Col della Stria (VI) e Grotta del Rio Secco (PN). PhD Thesis, University of Ferarra, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thun Hohenstein, U.; Caffarelli, L.; Arnetta, G.; Rivals, F.; Pozzobon, P.; Gialanella, S.; Delpiano, D.; Peresani, M. Taphonomy of the fauna and chert assemblages from the Middle Palaeolithic site of Vajo Salsone, Eastern Italian Alps. Quaternary Science Advances 2024, 14, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modolo, M.; Rosell Ardèvol, J.; Blasco, R.; Turrini, M.; Hohenstein, U. Bone refits at Abric Romaní (Barcelona, Spain) and Riparo Tagliente (Verona, Italy): Testing Neanderthal use of space and post-depositional disturbances. In Archaeological, Biological and Historical Approaches in Archaeozoological Research; Pişkin, BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thun-Hohenstein, U.; Parere, V.; Sala, B.; Giunti, P.; Longo, L. Large mammals from Mezzena rockshelter: new biocronological and palaeoecological hypotheses and preliminary data on subsistence strategies. Quaternary International 2012, 259, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, I.; Gala, M.; Romandini, M.; Cocca, E.; Tagliacozzo, A.; Peresani, M. From feathers to food: Reconstructing the complete exploitation of avifaunal resources by Neanderthals at Fumane cave, unit A9. Quaternary International 2016, 421, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romandini, M.; Hohenstein, U.T.; Fiore, I.; Tagliacozzo, A.; Perez, A.; Lubrano, V.; Terlato, G.; Peresani, M. Late neandertals and the exploitation of small mammals in northern Italy: fortuity, necessity or hunting variability? Quaternaire 2018, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlato, G.; Livraghi, A.; Romandini, M.; Peresani, M. Large bovids on the Neanderthal menu: Exploitation of Bison priscus and Bos primigenius in northeastern Italy. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2019, 25, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binford, L.R. Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeology. Academic Press: New York, USA, 1978.

- Binford, L.R. In Pursuit of the Past: Decoding the Archaeological Record. University of California Press: Berkeley, USA, 1983.

- Chang, C.-Y.; Ke, D.-S.; Chen, J.-Y. Essential fatty acids and human brain. Acta Neurologica Taiwanica 2009, 18, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Agam, A.; Barkai, R. Not the brain alone: The nutritional potential of elephant heads in Paleolithic sites. Quaternary International 2016, 406, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougier, H.; Crevecoeur, I.; Beauval, C.; Posth, C.; Flas, D.; Wißing, C.; Furtwängler, A.; Germonpré, M.; Gómez-Olivencia, A.; Semal, P.; van der Plicht, J.; Bocherens, H.; Krause, J. Neandertal cannibalism and Neandertal bones used as tools in Northern Europe. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 29005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Pickering, T.R.; Semaw, S.; Rogers, M.J. Cutmarked bones from Pliocene archaeological sites at Gona, Afar, Ethiopia: implications for the function of the world’s oldest stone tools. Journal of Human Evolution 2005, 48, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, R.; Fernández Peris, J. A uniquely broad spectrum diet during the Middle Pleistocene at Bolomor Cave (Valencia, Spain). Quaternary International 2012, 252, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, J.; Daujeard, C.; Saladié, P.; Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A.; Vettese, D.; Rivals, F.; Boulbes, N.; Crégut-Bonnoure, E.; Lateur, N.; Gallotti, R.; Arbez, L.; Puaud, S.; Moncel, M.-H. Neanderthal faunal exploitation and settlement dynamics at the Abri du Maras, level 5 (south-eastern France). Quaternary Science Reviews 2020, 243, 106472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, P.G. The Hunters of Combe-Grenal: Approaches to Middle Paleolithic Subsistence in Europe. BAR International Series S286; British Archaeological Reports: Oxford, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Romandini, M.; Terlato, G.; Nannini, N.; Tagliacozzo, A.; Benazzi, S.; Peresani, M. Bears and humans, a Neanderthal tale. Reconstructing uncommon behaviors from zooarchaeological evidence in southern Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science 2018, 90, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livraghi, A.; Fanfarillo, G.; Colle, M.D.; Romandini, M.; Peresani, M. Neanderthal ecology and the exploitation of cervids and bovids at the onset of MIS4: A study on De Nadale cave, Italy. Quaternary International 2021, 586, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romandini, M.; Silvestrini, S.; Real, C.; Lugli, F.; Tassoni, L.; Carrera, L.; Badino, F.; Bortolini, E.; Marciani, G.; Delpiano, D.; Piperno, M.; Collina, C.; Peresani, M.; Benazzi, S. Late Neanderthal “menu” from northern to southern Italy: freshwater and terrestrial animal resources. Quaternary Science Reviews 2023, 315, 108233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudzinski, S. A matter of high resolution? The Eemian Interglacial (OIS 5e) in north-central Europe and Middle Palaeolithic subsistence. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 2004, 14, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, D.S.; Bar-Oz, G.; Belfer-Cohen, A.; Bar-Yosef, O. Ahead of the Game. Current Anthropology 2006, 47, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiner, M.C.; Munro, N.D.; Surovell, T.A. The Tortoise and the Hare: Small-Game Use, the Broad-Spectrum Revolution, and Paleolithic Demography. Current Anthropology 2000, 41, 39–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunidis, A.; Blasco, R.; Brugal, J.-P.; Fourcade, T.; Ochando, J.; Rosell, J.; Roussel, A.; Rufà, A.; Sánchez Goñi, M.F.; Texier, P.-J.; Rivals, F. Neanderthal hunting grounds: The case of Teixoneres Cave (Spain) and Pié Lombard rockshelter (France). Journal of Archaeological Science 2024, 168, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Taxa | NISP | NISP% | MNI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rodentia indet. | 4 | 0.9 | 1 |

| Tot. Rodentia | 4 | 0.9 | 1 |

| Aves | 1 | 0.2 | 1 |

| Tot. Aves | 1 | 0.2 | 1 |

| Vulpes vulpes | 1 | 0.2 | 1 |

| Ursus arctos | 3 | 0.7 | 3 |

| Ursus spelaeus | 2 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Ursus sp. | 3 | 0.7 | 3 |

| Meles meles | 2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Carnivora indet | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Tot. Carnivora | 12 | 2.8 | 10 |

| Megaloceros giganteus | 1 | 0.2 | 1 |

| Alces alces | 2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Cervus elaphus | 92 | 21.7 | 8 |

| Capreolus capreolus | 30 | 7.1 | 3 |

| Large Cervidae | 3 | 0.7 | 2 |

| Cervidae indet. | 12 | 2.8 | 5 |

| Caprine | 6 | 1.4 | 1 |

| Capra ibex | 8 | 1.9 | 3 |

| Rupicapra rupicapra | 18 | 4.2 | 2 |

| Ungulata indet. | 235 | 55.4 | |

| Tot. Ungulata | 407 | 96 | 26 |

| TOT. NISP | 424 | 100.00 | 38 |

| Undetermined Specimens | |||

| Small size mammals | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Medium size mammals | 18 | 2.6 | |

| Medium-Big size mammals | 27 | 3.9 | |

| Big size mammals | 8 | 1.2 | |

| Undetermined | 214 | 30.9 | |

| TOT. UNDETERMINED | 268 | 38.7 | |

| TOT. NR | 692 | 100.00 | |

| Taxa | NISP | CM | PM | CM+PM | Tot. BM | % BM | R | B | C | GM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Megaloceros gigantieus | 1 | |||||||||

| Alces alces | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50.00 | 1 | |||||

| Cervus elaphus | 92 | 28 | 4 | 1 | 33 | 35.87 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Capreolus capreolus | 30 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 36.67 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Large Cervidae | 3 | |||||||||

| Cervidae indet. | 12 | 1 | 1 | 8.33 | ||||||

| Caprine | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 66.67 | ||||

| Capra ibex | 8 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 37.50 | |||||

| Rupicapra rupicapra | 18 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 27.78 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Ungulata indet. | 235 | 65 | 2 | 2 | 69 | 29.36 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 5 |

| TOTAL | 407 | 111 | 10 | 6 | 127 | 31.20 | 4 | 13 | 12 | 12 |

| Anatomical Element | NISP | CM | PM | CM+PM | Tot. BM | % BM | R | B | C | GM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cranium | ||||||||||

| Hemimandible | 5 | 1 | 1 | 20.0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Tooth | 4 | |||||||||

| Hyoid | ||||||||||

| Total cranium | 9 | 1 | 1 | 11.1 | ||||||

| Atlas-axis | ||||||||||

| Vertebra | ||||||||||

| Rib | ||||||||||

| Total axial skeleton | ||||||||||

| Scapula | ||||||||||

| Humerus | 6 | 2 | 2 | 33.3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Radius | 5 | 3 | 3 | 60.0 | ||||||

| Ulna | ||||||||||

| Metacarpal | 14 | 4 | 4 | 28.6 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Total forelimb | 25 | 9 | 9 | 36.0 | ||||||

| Coxal | 1 | |||||||||

| Femur | 12 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 58.3 | 1 | |||

| Tibia | 13 | 4 | 4 | 30.8 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Metatarsal | 12 | 6 | 6 | 50.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total hindlimb | 38 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 17 | 44.7 | ||||

| Metapodials | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 50.0 | |||||

| First phal. | 7 | 2 | 2 | 28.6 | ||||||

| Second phal. | ||||||||||

| Third phal. | 2 | |||||||||

| First phal. rudim. | ||||||||||

| Second phal. rudim. | 1 | |||||||||

| Third phal. rudim. | 1 | |||||||||

| Sesamoid | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50.0 | ||||||

| Diaphysis | 1 | |||||||||

| Total indet. Limb | 20 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 30.0 | |||||

| TOTAL | 92 | 28 | 4 | 1 | 33 | 35.9 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).