Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

5. Conclusions

References

- B. Szyszka et al., “Recent developments in the fi eld of transparent conductive oxide fi lms for spectral selective coatings , electronics and photovoltaics,” vol. 12, pp. 2–11, 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Khlayboonme and W. Thowladda, “Impact of Al-doping on structural , electrical , and optical properties of sol-gel dip coated ZnO : Al thin films Impact of Al-doping on structural , electrical , and optical properties of sol-gel dip coated ZnO : Al thin fi lms.”.

- G. Socol et al., “substrates,” Appl. Surf. Sci., no. November, 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Kim, I. Yun, and H. Kim, “Fabrication of rough Al doped ZnO films deposited by low pressure chemical vapor deposition for high efficiency thin film solar cells,” Curr. Appl. Phys., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. S459–S462, 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Di, M. Cantarella, G. Nicotra, and V. Privitera, “Applied Catalysis B : Environmental Low temperature atomic layer deposition of ZnO : Applications in photocatalysis,” "Applied Catal. B, Environ., vol. 196, pp. 68–76, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Target, “Sprayed Composite Target,” 2021.

- K. Daoudi, B. Canut, M. G. Blanchin, C. S. Sandu, V. S. Teodorescu, and J. A. Roger, “Densification of In 2 O 3 : Sn multilayered films elaborated by the dip-coating sol – gel route,” vol. 445, no. 03, pp. 20–25, 2003. 2003; 25. [CrossRef]

- D. Mendil et al., “US,” 2019.

- B. Stieberova, M. Zilka, M. Ticha, F. Freiberg, and E. Lester, “Application of ZnO nanoparticles in Self-Cleaning Coating on a Metal Panel : An Assessment of Environmental Benefits.”.

- N. P. Patel and K. V Chauhan, “Effect of sputtering power and substrate temperature on structural , optical , wettability and anti-icing characteristics of aluminium doped zinc oxide Effect of sputtering power and substrate temperature on structural , optical , wettability and anti-icing characteristics of aluminium doped zinc oxide.”.

- G. Yu, Y. Liu, D. Hong, D. Li, and J. Zang, “Influence of Sputtering Power and Substrate Temperature on properties of Al 2 O 3 -doped ZnO Films,” vol. 559, pp. 1945–1949, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Brassard, D. K. Sarkar, and J. Perron, “Applied Surface Science Studies of drag on the nanocomposite superhydrophobic surfaces,” Appl. Surf. Sci., vol. 324, pp. 525–531, 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Guo et al., “Superlattices and Microstructures Optimization of oxygen and pressure of ZnO : Al films deposited on PMMA substrates by facing target sputtering,” Superlattices Microstruct., vol. 64, pp. 552–562, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Gurav et al., “Superhydrophobic surface decorated with vertical ZnO nanorods modi fi ed by stearic acid,” Ceram. Int., vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 7151–7160, 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Kim et al., “Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing Effects of oxygen concentration on the properties of Al-doped ZnO transparent conductive films deposited by pulsed DC magnetron sputtering,” Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 997–1001, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Mustapha, M. M. Ndamitso, A. S. Abdulkareem, and J. O. Tijani, “Comparative study of crystallite size using Williamson-Hall and Debye- Comparative study of crystallite size using Williamson-Hall and Debye-Scherrer plots for ZnO nanoparticles,” 2019.

- Q. Shi, K. Zhou, M. Dai, S. Lin, H. Hou, and C. Wei, “Growth of high-quality Ga – F codoped ZnO thin fi lms by mid-frequency sputtering,” Ceram. Int., vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 211–216, 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Zhang, R. Y. Hong, Q. Chen, and W. G. Feng, “On the electrical conductivity and photocatalytic activity of aluminum-doped zinc oxide On the electrical conductivity and photocatalytic activity of aluminum-doped zinc oxide,” Powder Technol., vol. 253, no. April, pp. 360–367, 2022. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Marikkannan, A. Dinesh, J. Mayandi, V. Vishnukanthan, and J. M. Pearce, “Properties of Al-Doped Zinc Oxide and In-Doped Zinc Oxide Bilayer,” Mater. Lett., 2018. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee, B. He, and N. A. Patankar, “A roughness-based wettability switching membrane device for hydrophobic surfaces,” vol. 591. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Rawal, A. Kumar, V. Chawla, R. Jayaganthan, and R. Chandra, “Structural , optical and hydrophobic properties of sputter deposited zirconium oxynitride films,” Mater. Sci. Eng. B, vol. 172, no. 3, pp. 259–266, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Noormohammed, “Nanostructured Titanium Dioxide Coating on Aluminum Alloy for Icephobic Applications,” 2021.

- Y. Wu et al., “An extremely chemical and mechanically durable siloxane bearing copolymer coating with self-crosslinkable and anti-icing properties,” Compos. Part B, vol. 195, no. March, p. 108031, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Substrate :- | High Power transmission line (Panther conductor), Corning glass | ||||||

| Target material :- | AZO (99.999% purity) | ||||||

| Base Pressure :- | 1 * 10-3 Pa | ||||||

| Substrate to target distance :- | 50 mm | ||||||

| Substrate temperature :- | Room temperature | ||||||

| Deposition time :- | 30 min | ||||||

| Sputtering gas :- | Ar ( with flow rate of 10 SCCM) | ||||||

|

Target gas symbol |

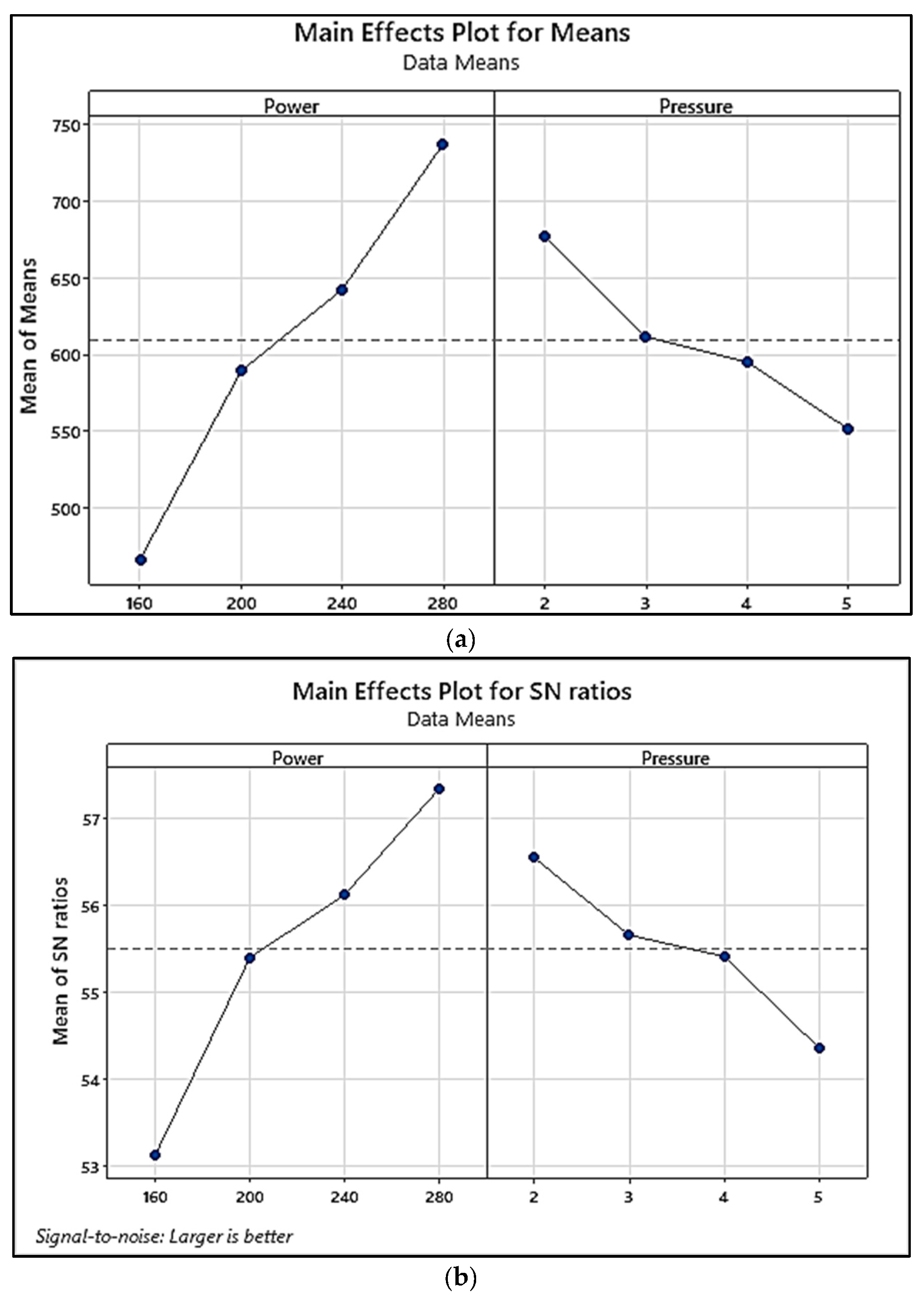

Control factors | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | ||

| A | Deposition Power (W) | 160 | 200 | 240 | 280 | ||

| B | Deposition Pressure (Pa) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Design Summary :- | ||||||||||

| Taguchi Array :- L16 (4^2) | ||||||||||

| Factors :- 2 | ||||||||||

| Runes :- 16 | ||||||||||

| Columns of L16 (4^2) array : 1 2 | ||||||||||

| Deposition temperature :- Room temperature | ||||||||||

| Deposition time :- 30 min | ||||||||||

| Sputtering gas :- Ar with gas flowrate of 10SCCM | ||||||||||

| Sample name | Encoded factors | Decoded factors | ||||||||

| A (W) | B (Pa) | Power (W) | Pressure (Pa) | |||||||

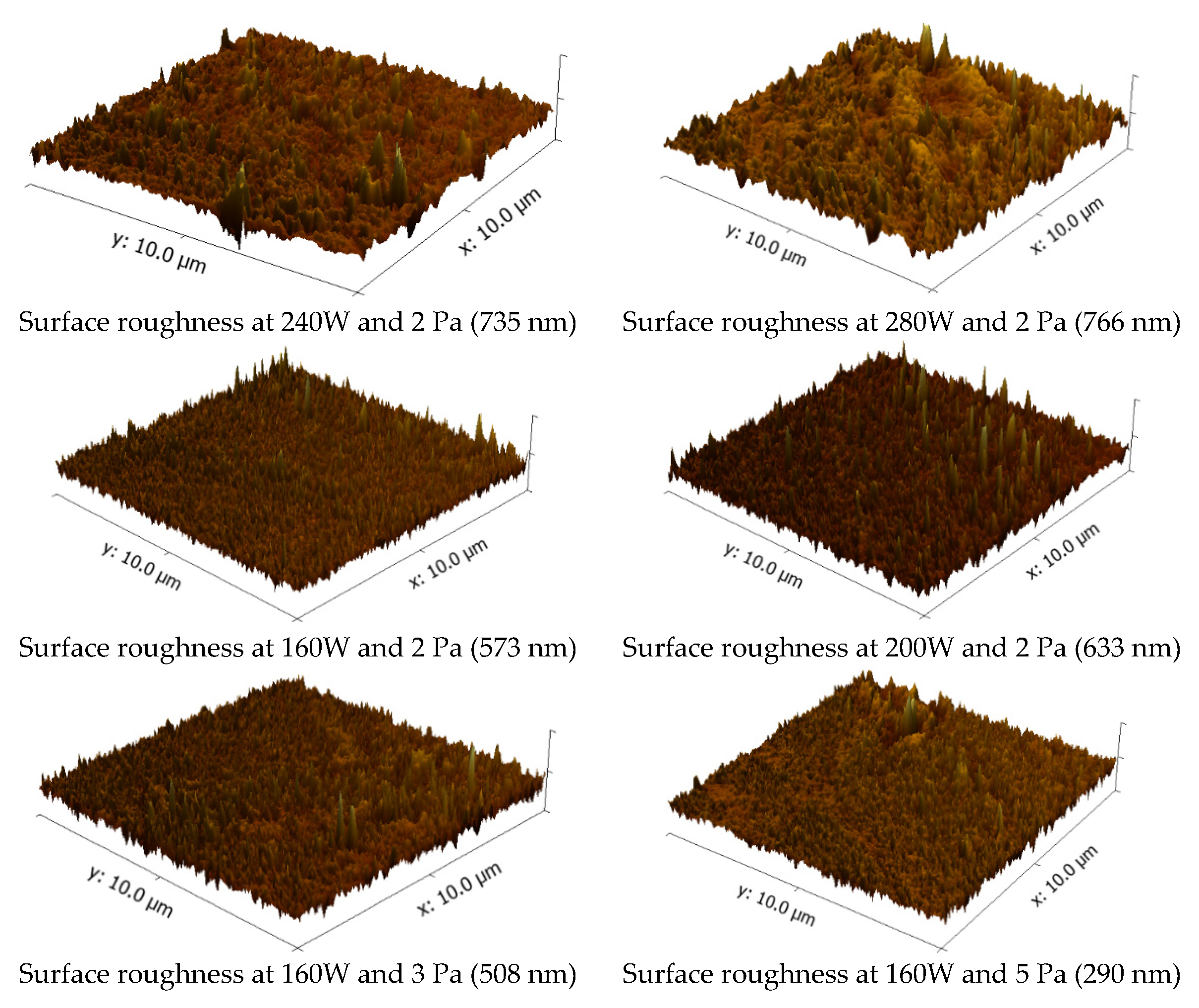

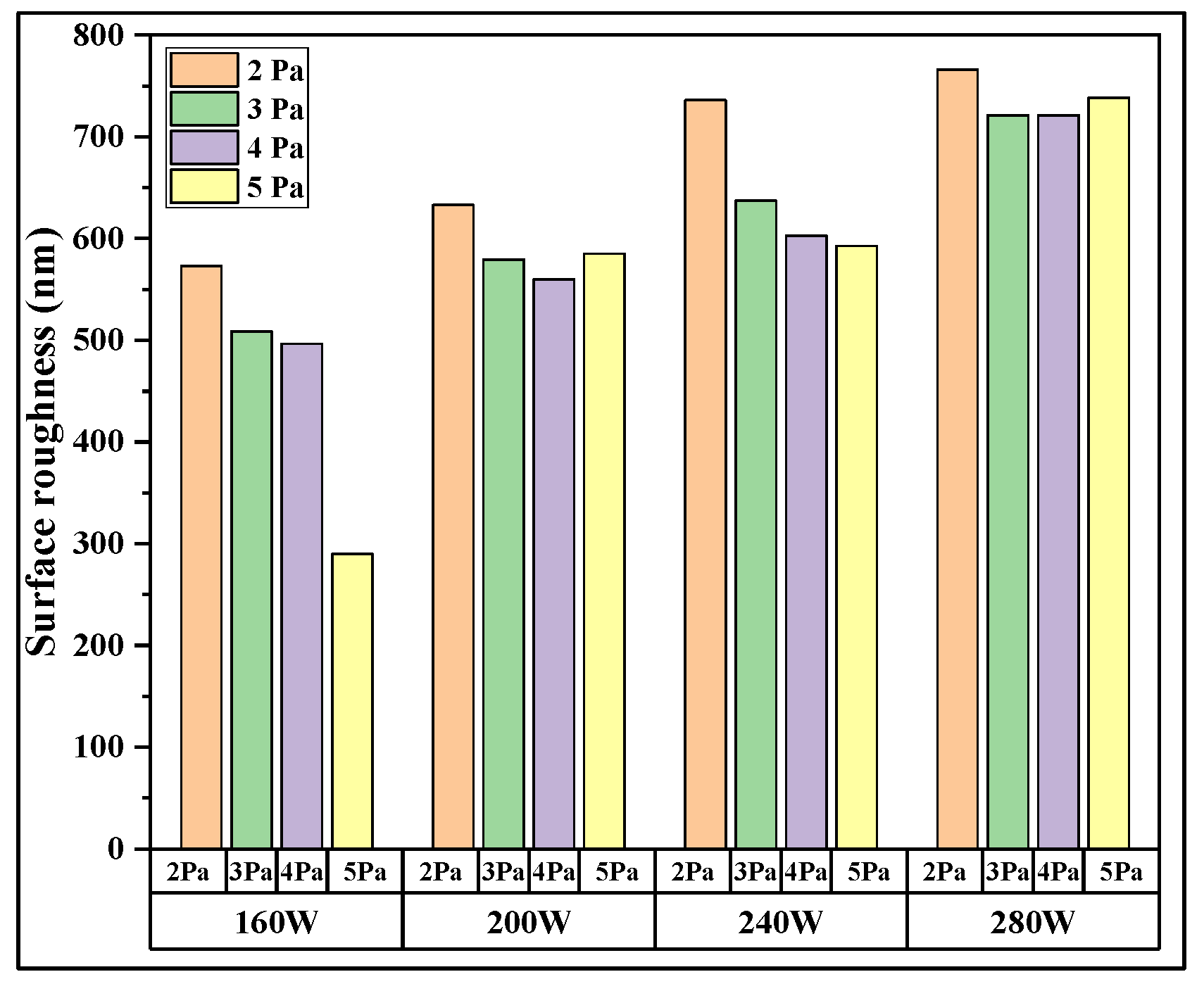

| Sample 1 | 1 | 1 | 160 | 2 | ||||||

| Sample 2 | 1 | 2 | 160 | 3 | ||||||

| Sample 3 | 1 | 3 | 160 | 4 | ||||||

| Sample 4 | 1 | 4 | 160 | 5 | ||||||

| Sample 5 | 2 | 1 | 200 | 2 | ||||||

| Sample 6 | 2 | 2 | 200 | 3 | ||||||

| Sample 7 | 2 | 3 | 200 | 4 | ||||||

| Sample 8 | 2 | 4 | 200 | 5 | ||||||

| Sample 9 | 3 | 1 | 240 | 2 | ||||||

| Sample 10 | 3 | 2 | 240 | 3 | ||||||

| Sample 11 | 3 | 3 | 240 | 4 | ||||||

| Sample 12 | 3 | 4 | 240 | 5 | ||||||

| Sample 13 | 4 | 1 | 280 | 2 | ||||||

| Sample 14 | 4 | 2 | 280 | 3 | ||||||

| Sample 15 | 4 | 3 | 280 | 4 | ||||||

| Sample 16 | 4 | 4 | 280 | 5 | ||||||

| Sample name | Decoded factors | Results | ||

| Power (W) | Pressure (Pa) | Average grain size (nm) | SN ratio | |

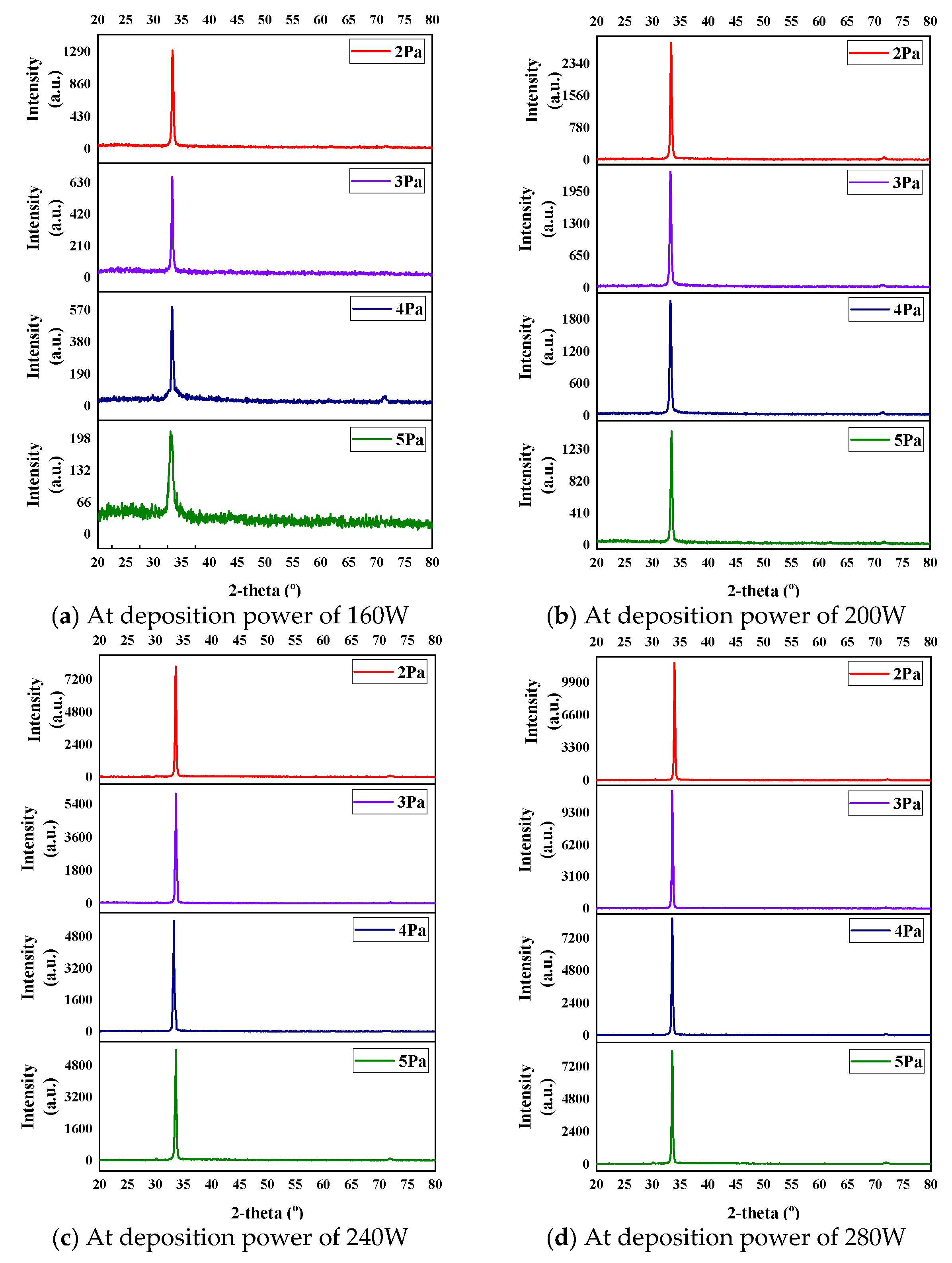

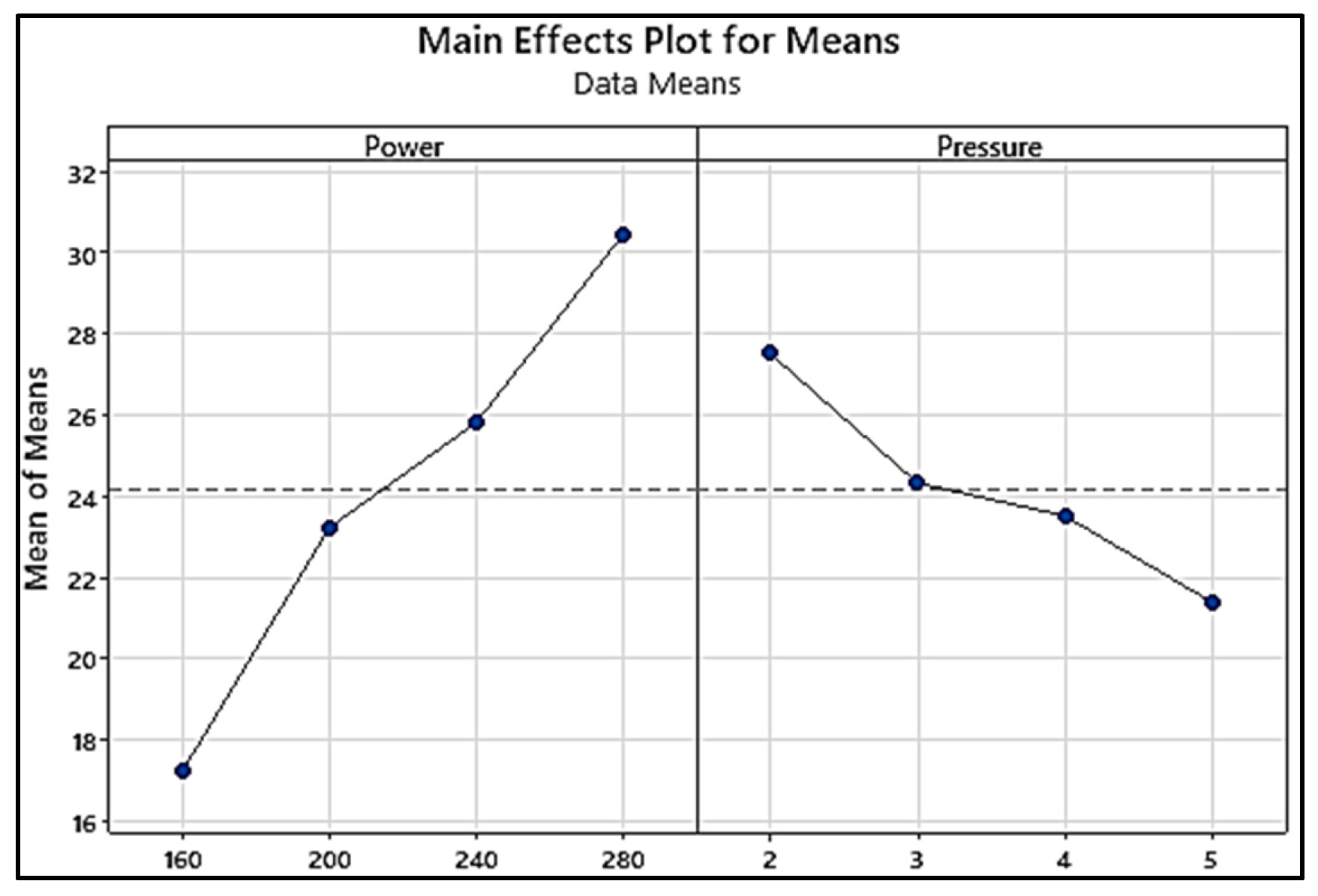

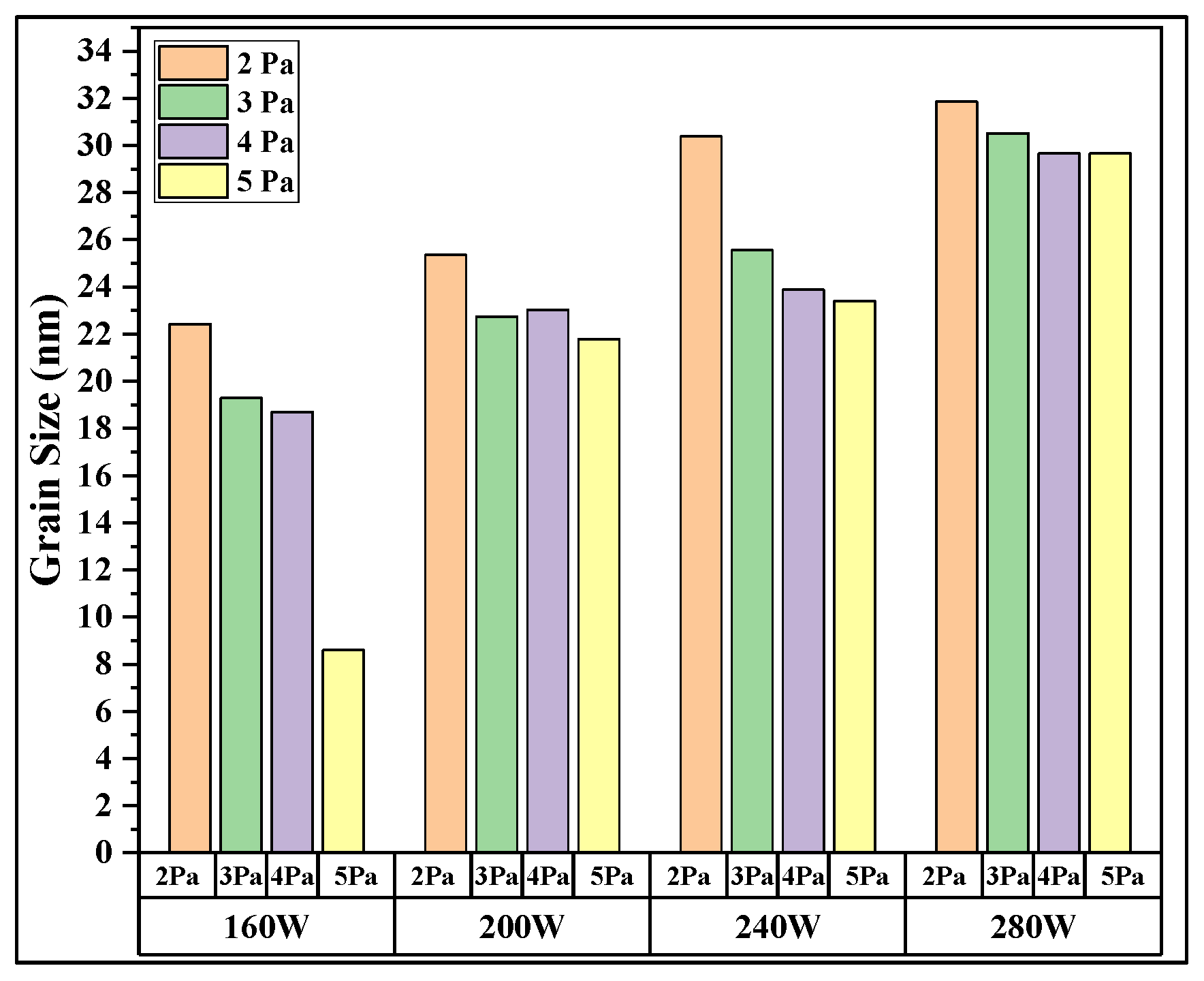

| Sample 1 | 160 | 2 | 22.4289 | 27.0162 |

| Sample 2 | 160 | 3 | 19.2921 | 25.7076 |

| Sample 3 | 160 | 4 | 18.699 | 25.4364 |

| Sample 4 | 160 | 5 | 8.6039 | 18.694 |

| Sample 5 | 200 | 2 | 25.3631 | 28.084 |

| Sample 6 | 200 | 3 | 22.7393 | 27.1356 |

| Sample 7 | 200 | 4 | 21.7846 | 26.763 |

| Sample 8 | 200 | 5 | 23.0297 | 27.2458 |

| Sample 9 | 240 | 2 | 30.3812 | 29.6521 |

| Sample 10 | 240 | 3 | 25.5565 | 28.15 |

| Sample 11 | 240 | 4 | 23.8829 | 27.5617 |

| Sample 12 | 240 | 5 | 23.394 | 27.3821 |

| Sample 13 | 280 | 2 | 31.8523 | 30.0628 |

| Sample 14 | 280 | 3 | 29.667 | 29.4455 |

| Sample 15 | 280 | 4 | 29.6698 | 29.4463 |

| Sample 16 | 280 | 5 | 30.5163 | 29.6906 |

| Deposition temperature :- Room temperature | |||||||||

| Deposition time :- 30 min | |||||||||

| Sputtering gas :- Ar with gas flowrate of 10SCCM | |||||||||

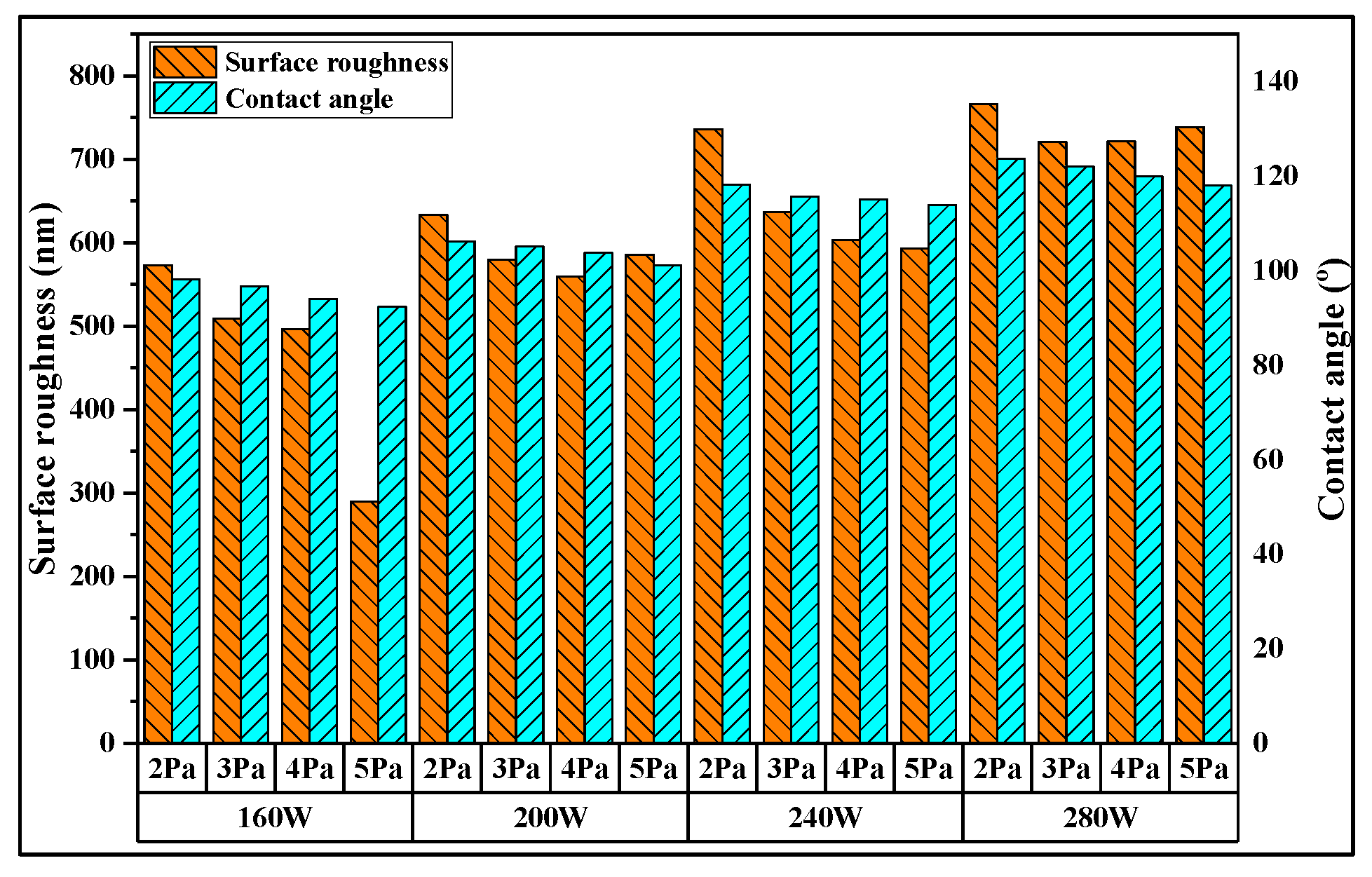

| Sample name | Factors | Results | |||||||

| Power (W) | Pressure (Pa) | Contact angle (o) | SNR | ||||||

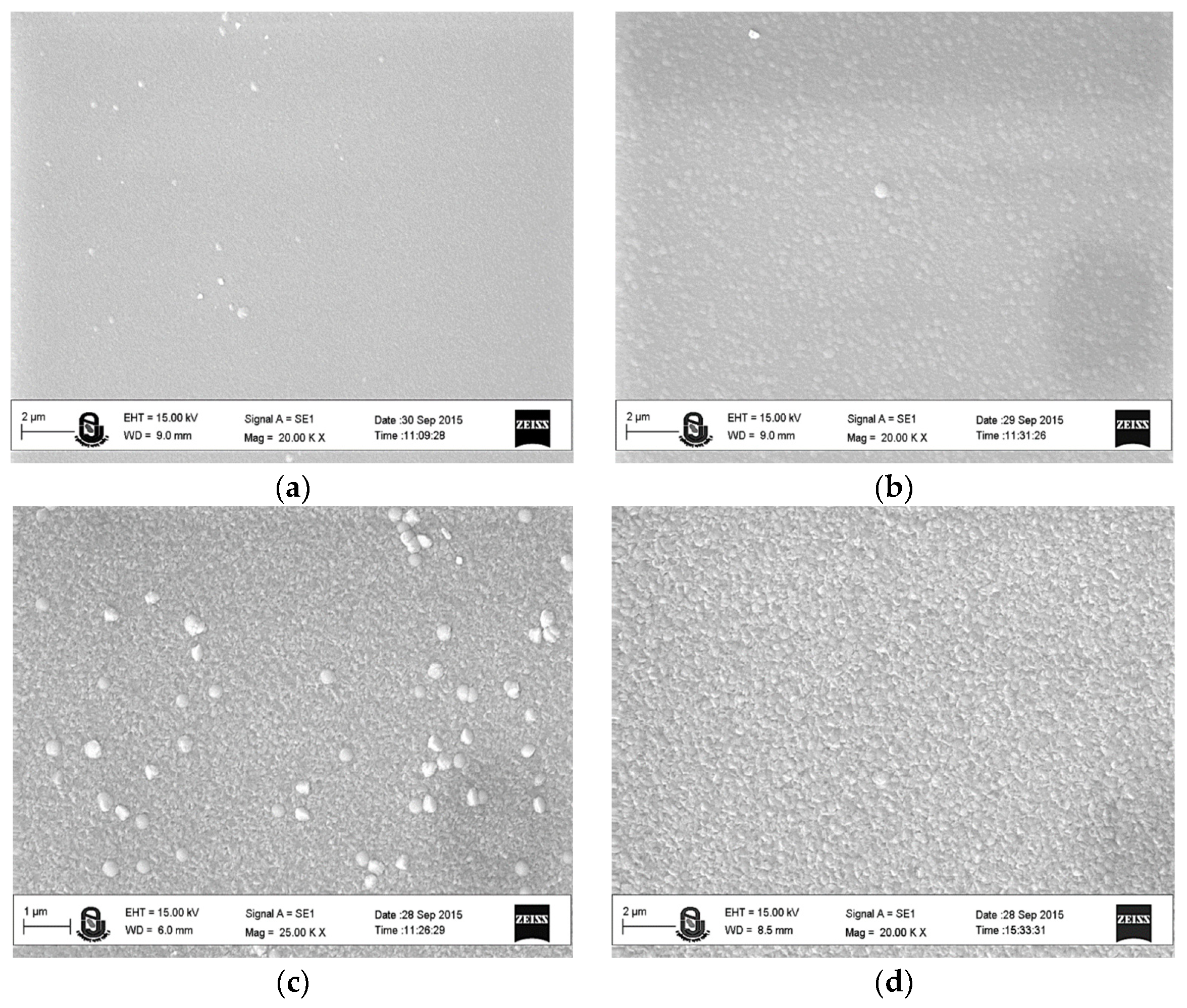

| Sample 1 | 160 | 2 | 98.2 | 39.84223 | |||||

| Sample 2 | 160 | 3 | 96.7 | 39.70853 | |||||

| Sample 3 | 160 | 4 | 94 | 39.46256 | |||||

| Sample 4 | 160 | 5 | 92.3 | 39.30403 | |||||

| Sample 5 | 200 | 2 | 106.2 | 40.52249 | |||||

| Sample 6 | 200 | 3 | 105.1 | 40.43205 | |||||

| Sample 7 | 200 | 4 | 103.7 | 40.31558 | |||||

| Sample 8 | 200 | 5 | 101.1 | 40.09502 | |||||

| Sample 9 | 240 | 2 | 118.2 | 41.45235 | |||||

| Sample 10 | 240 | 3 | 115.6 | 41.25916 | |||||

| Sample 11 | 240 | 4 | 115 | 41.21396 | |||||

| Sample 12 | 240 | 5 | 113.8 | 41.12285 | |||||

| Sample 13 | 280 | 2 | 123.6 | 41.84037 | |||||

| Sample 14 | 280 | 3 | 122 | 41.7272 | |||||

| Sample 15 | 280 | 4 | 120 | 41.58362 | |||||

| Sample 16 | 280 | 5 | 118 | 41.43764 | |||||

| Response table Signal to Noise ratio | |||||||||

| Larger is Better | |||||||||

| Level | Power | Pressure | |||||||

| 1 | 39.58 | 40.91 | |||||||

| 2 | 40.34 | 40.78 | |||||||

| 3 | 41.26 | 40.64 | |||||||

| 4 | 41.65 | 40.49 | |||||||

| Delta | 2.07 | 0.42 | |||||||

| Rank | 1 | 2 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).