1. Introduction

The process of cost estimation anticipates the financial requirements for executing construction activities to achieve the predetermined objectives of a construction project within a specified timeframe [

1]. It holds significance as it provides important financial insights for project decision-making in the initial phases [

2,

3,

4]. Given the high flexibility in project scope, design, specifications, and standards during the early phases of the project, it is essential to conduct construction cost estimation as early as possible [

5]. Inaccurate cost estimation can negatively impact construction project outcomes, as erroneous estimates may lead to failures in meeting budget and schedule targets [

1]. Despite its critical role, the estimation process remains one of the most fragmented and labor-intensive areas in the construction industry [

6,

7]. Construction cost estimation involves labor-intensive processes, including quantifying materials and extracting cost data from different databases, obtaining additional cost information from specifications; mapping building elements to work/cost items; and looking up unit costs to calculate estimates. These tasks currently rely heavily on manual human effort [

8,

9]. Multiple studies in the past have highlighted that estimation is not only time-consuming but also highly prone to errors. Manual quantity take-offs, inconsistent documentation, and siloed cost records contribute to delays and inaccuracies, particularly during early project phases when estimates are most influential [

3,

10,

11]. Although tools such as BIM and cost databases have improved aspects of the process, they have not resolved fundamental issues like fragmented workflows, lack of data standardization, and repetitive evaluation of subcontractor inputs [

12]. In recent years, numerous studies have applied artificial intelligence techniques to support cost estimation in construction. For example, in 2023, a study developed an ANN-based model aiming to overcome the limitations of conventional methods [

13]. Frequently used AI techniques for estimation include case-based reasoning (CBR) [

14], fuzzy logic [

15], regression [

16], support vector machine (SVM) [

17], and hybrid model [

18]. Some studies proposed BIM-based frameworks to reduce manual effort and improve accuracy. However, BIM models at lower levels of detail (LODs) may lack sufficient information for accurate estimation [

8,

19].

While machine learning and AI-based estimation models have shown promise in academic literature [

20], industry implications for industry workflows remain limited. This is often due to misalignment between how estimation is actually practiced in industry and how AI models are designed. Bridging that gap requires a clear understanding of current workflows, the specific burdens estimators face, and where LLMs can add meaningful support[

21]. This study addresses that need by mapping the real-world construction cost estimation workflow, identifying task-level burdens through expert interviews, and proposing a Generative AI-integrated framework specific to those challenges. Rather than treating estimation as a black-box input/output problem, this research takes the ground up, starting with what estimators actually do, what slows them down, and how AI can be designed to help. The goal is to support- not replace- the estimator, offering targeted automation where it’s needed most.

1.1. Problem Statement

While prior studies have explored machine learning (ML) models to support construction cost estimation, most remain disconnected from real-world workflows. What’s missing is a workflow map that reflects how estimation actually operates in industry-one that clearly maps the information exchanged among stakeholders across project phases, identifies the required data inputs, and provides guidance on selecting and embedding AI tools to reduce repetitive, time-consuming tasks. No generative AI-based approach has yet been proposed that maps how estimation is actually practiced, how data flows between stakeholders, what information is needed at each phase, and what the pain points are. The rapid rise of generative AI in recent years offers new opportunities for automation and decision support, but construction has yet to capitalize on it. This gap in the literature is most likely due to the recency of this advancement and the absence of a clear, practice-oriented framework for its integration. Also, the current literature does not provide GenAI-driven solutions that support industry estimation workflow, which is a significant oversight as interest in AI continues to grow. The previous study [

11] confirm that while the industry is still early in its AI adoption, there’s growing demand and the highest priority for cost estimation. Without a structured framework to guide GenAI integration, however, these efforts remain scattered and underutilized. A targeted, GenAI-based framework is needed to align with real estimator needs, improve efficiency, and modernize construction cost estimation practices.

1.2. Research Main Objective

To map the existing cost estimation workflow, identify burdens, and propose a GenAI-integrated framework to reduce cost estimation burdens in the construction industry. To achieve the main objective, the research is structured around several guiding research questions (RQ):

1.3. Research Questions

RQ1. How does the current estimation workflow- data, exchange, and stakeholders- look?

The objective of this research question is to map the industry workflow for cost estimation in construction.

RQ2. What are the burdens of the existing cost estimation process?

The objective of this research question is to identify existing pain points (burdens) in the construction cost estimation workflow.

RQ3. How can we design an LLM-integrated workflow that facilitates extraction, analysis, and assistance throughout the estimation process?

The objective of this research question is to develop a framework for integrating Generative LLM into existing workflows to support cost estimation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Construction Cost Estimation

Construction cost estimation is a multi-stage, collaborative process central to decision-making across the project lifecycle. It begins with broad conceptual estimates during early feasibility and progresses through more detailed, design-informed stages, culminating in final, bid-level estimates before construction commences. Estimating is not only a cost-reporting exercise but also an active financial control mechanism within project planning, design, and procurement [

22]. The availability and quality of project information shape each stage. In the initial phases, owners or their representatives prepare feasibility-level estimates using limited data- project size, function, location, and historical similarities [

6,

9,

20]. These early estimates, often parametric in nature, help assess project viability but carry high levels of uncertainty [

23]. As design matures, architects and engineers contribute detailed drawings and specifications, enabling quantity surveyors or cost estimators to perform systematic quantity take-offs [

24,

25]. The accuracy of estimates improves with each iteration, but only if design data is timely, complete, and structured appropriately.

Modern estimation practices increasingly rely on digital tools- particularly Building Information Modeling (BIM)- to support automation and reduce manual effort. BIM models, when properly developed, allow quantities to be extracted directly from 3D representations, streamlining the take-off process and reducing human error [

26,

27]. However, studies show that manual measurement still dominates, consuming most of an estimator’s time on typical projects [

12,

25,

28]. In many cases, models lack sufficient detail, metadata, or standardization, requiring parallel manual checks to ensure reliability [

24].

Once quantities are determined, pricing involves applying unit rates- drawn from historical data, cost libraries (e.g., RSMeans), or supplier/subcontractor quotes, adjusted for local market conditions, inflation, productivity rates, and project-specific risks [

10,

29]. Cost estimators also generally factor in indirect costs, profit margins, escalation, and contingency allowances. This step often requires interdisciplinary collaboration. Specialized trades such as mechanical, electrical, or façade systems may require input or bids from subcontractors, which are then reconciled and incorporated into the larger estimate [

30,

31]. Estimate review is an iterative, quality control process. Senior estimators, cost managers, or project leads evaluate estimate completeness, compare outputs against benchmarks, and flag inconsistencies. If cost targets are exceeded, value engineering exercises are initiated, which require close coordination with designers to explore alternative materials, construction methods, or scope adjustments [

6,

22]. This stage reinforces that estimating is not a linear process but a feedback-driven loop that informs design and planning decisions in real-time. Finalized estimates are typically documented by the system, the CSI division, or the construction phase and include a basis of estimate report outlining assumptions, exclusions, and contingency logic. These deliverables serve both as internal planning tools and contractual references. In competitive bidding, contractors submit their detailed proposals, which the client team then evaluates for scope coverage, pricing strategy, and compliance with requirements [

32]. A persistent challenge in this workflow is the fragmented nature of information exchange. Traditional reliance on 2D drawings and static documents creates chances of misinterpretation, scope omissions, or outdated quantities, especially when design changes are not effectively communicated [

33]. In contrast, the 5D BIM model links cost data directly to 3D models, which helps with real-time synchronization and helps maintain transparency among estimators, designers, and clients [

26,

27]. For example, if a design team updates the structural grid or window schedule, the linked cost model can immediately reflect the change and update across teams. However, full integration is far from universal; technical barriers, interoperability issues, and partial digital adoption remain widespread [

12].

Stakeholder roles are diverse yet interdependent. The cost estimator or quantity surveyor leads the quantification and pricing effort. The designer provides evolving inputs, while the client defines budget constraints and strategic priorities. In parallel, contractors and subcontractors may engage early under design-build or collaborative delivery models to contribute real-time market pricing and constructability insights [

34,

35]. A good estimate goes beyond just crunching numbers. It depends on collaboration- staying connected, being clear about the role, understanding the risks, and aligning on key assumptions. At its core, cost estimating in construction is a mix of data-driven analysis and practical judgment that only comes from real-world experience. While modern tools, standards, and digital models have improved consistency, much of the workflow is still manually intensive and sequential. The reliance on individual expertise, fragmented tools, and inconsistent data structures has placed a need for emerging technologies- particularly artificial intelligence and generative models- to streamline, augment, and transform how estimates are produced, validated, and used in decision-making.

2.2. Existing Burdens of Construction Cost Estimation

Work-related stress in the construction industry is well-documented, with work overload emerging as one of the most pressing challenges faced by professionals in management roles [

11,

36]. While construction stressors stem from various sources, job-related demands- such as extended working hours and tight timelines- are frequently cited as significant contributors to mental and operational strain [

37]. Although no specific study investigated burden within cost estimation roles, these job characteristics are directly relevant to estimation tasks. Estimators often operate under tight deadlines, juggling large volumes of data with limited support [

38], which mirrors the broader pressures identified across the construction sector. As such, it is reasonable to infer that cost estimation professionals experience similar burdens related to time constraints, workload intensity, and insufficient recovery time- factors that can impair judgment, reduce accuracy, and diminish overall performance. Despite the formalized stages of cost estimation, significant practical burdens persist. A common challenge in the estimation process is the reliance on incomplete and evolving projects. Data during the early stages is limited when the scope and design are not complete [

6]. Therefore, estimators have to make assumptions under data limitations, which cause rough estimates that are prone to error. As design progresses over time, manual rework becomes labor-intensive and error-prone, challenging inefficiencies [

25,

26]. Time constraints further compound this problem. Estimators often work under tight deadlines with limited resources, reducing their ability to cross-check or analyze alternatives [

39]. Quantity take-off alone can consume more than two-thirds of their time, making the process laborious and repetitive [

27].

Manual workflows also introduce data fragmentation and coordination issues. Estimators must reconcile diverse inputs- drawings, specifications, and databases- often formatted inconsistently or using different coding systems [

12]. Lack of standard procedure in the organization, as well as industry-wide standardization, limits automation and knowledge reuse across projects [

3]. Moreover, cost forecasting remains heavily dependent on individual expertise and judgment, which introduces variability and bias[

23,

34]. As senior professionals retire, much tacit knowledge risks being lost without proper documentation [

10]. Meanwhile, cost volatility and external risks- ranging from market inflation to supply disruptions- further limit estimate reliability, yet probabilistic forecasting remains underutilized [

40]. Collectively, these burdens, technical, human, and systemic, indicate the need for an advanced workflow to automate data extraction, enhance analysis, and support estimators in reducing errors, bias, and inefficiencies. To systematically capture the breadth of challenges reported in the literature,

Table 1 synthesizes findings from related studies and authoritative industry sources. Each entry identifies the study’s focus and concisely describes the specific burden or estimation-related task it highlights. This thematic mapping provides a structured overview of the key bottlenecks that continue to hinder construction cost estimation workflows.

3. Methodology

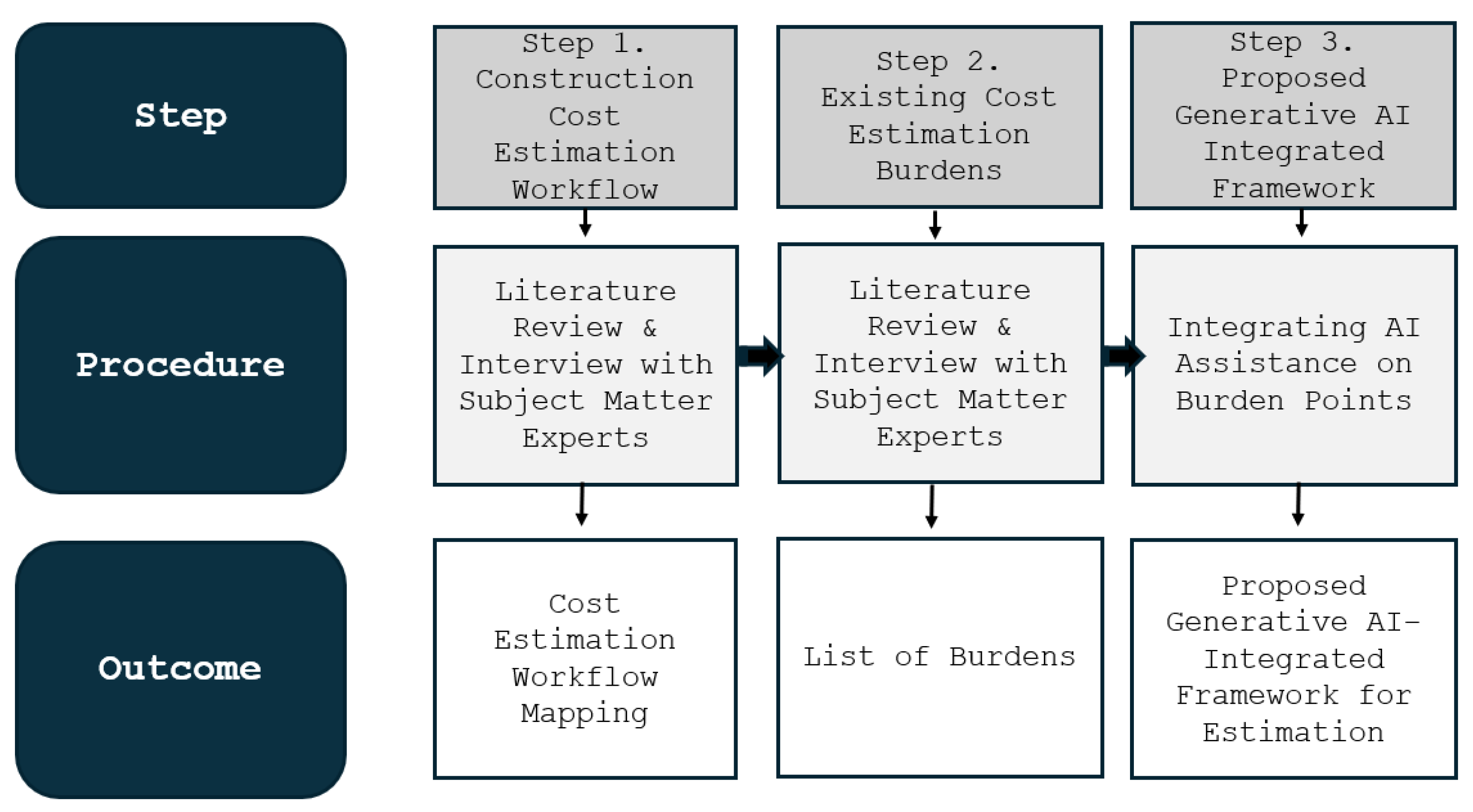

This study followed a qualitative three-step methodology (

Figure 1) to understand the current construction cost estimation practices, existing pain points (burdens) in the process, and an AI-integrated framework to address identified burdens. First, a detailed literature review was conducted to understand existing workflows and burdens. To ground these findings in industry practice, ten semi-structured interviews (30 minutes/interview) were conducted with subject matter experts, including cost estimators, BIM/VDC managers, data analysts, and project managers. The detailed questions outlined in

Section 3.1 were designed to get answers and gain deeper insights through multiple follow-ups and discussions conducted with industry experts. These interviews provided detailed insights into industry workflows, data types, and data exchange mechanisms among stakeholders. Building on this, the second phase focused on identifying and synthesizing burdens that hinder estimation efficiency and accuracy. While the literature highlighted common issues such as labor-intensive or manual data fragmentation, time pressure, and errors, interviews identified the actual tasks that were burdensome. These burdens were listed in order according to the phase of the project, stakeholder type, and data involved. This study’s scope is limited to only general contractors as stakeholders and pre-construction as a phase to develop an AI-integrated framework. In the final phase, a generative AI-integrated estimation framework was developed by aligning AI capabilities with specific burden points- for example, aggregating quantities, referencing external cost data, extracting insights from historical cost data, etc., for all 11 identified burdens. This framework was iteratively refined through expert feedback for further development in our next study.

3.1. Participant & Data Collection Procedure

To understand the existing construction cost estimation workflows in the industry, uncover existing burdens, and identify opportunities for generative AI integration, this study followed a qualitative research approach using semi-structured interviews. The potential participants were initially identified through purposive sampling based on their relevance to cost estimation functions and willingness to be contacted for follow-up, as indicated during a data collection phase of our previous study. Participants were selected to ensure diverse perspectives from key roles directly involved in or influencing the estimation process. These roles included Cost Estimators, responsible for generating estimates at different project phases; BIM/VDC Managers, who provide model-based quantity take-offs used in conceptual estimating; Data Analysts, who support cost breakdowns and are involved in work breakdown structures (WBS), and align cost codes; and Project Managers, who coordinate estimates with field execution and handle change management across project stages. The majority of interviews were conducted virtually, and some were conducted in person. Each session was approximately 30 minutes long, with some participants engaged in multiple rounds to clarify and deepen earlier insights. The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format, combining open-ended main questions with carefully designed follow-up questions and guiding prompts to guide detailed and focused responses. This approach aligns with widely adopted qualitative best practices [

43,

44,

45]. This process allows for consistent coverage of core themes and the flexibility to explore emergent details. The first section of the interview focused on understanding the cost estimation workflow. The interviews were guided by a semi-structured qualitative instrument built around three key sections: (1) cost estimation workflow, (2) estimation burdens, and (3) AI integration opportunities. Each section was designed with a main question to introduce a topic, follow-up questions to probe specific aspects, and guiding prompts to guide focus or to get detailed responses when participants’ answers were vague or too broad. For example, a main question,

“Can you describe the typical cost estimation workflow in your organization?” was followed by a prompt,

“What are the major stages and decision points?”. This process was intended to ensure that responses remained aligned with the objectives and to provide an opportunity for participants to elaborate based on their unique experiences. Follow-ups were applied when participants offered partial information, while prompts were especially useful when participants misunderstood the intent of a question or provided responses that lacked operational detail. The following are the detailed questions asked during the interviews:

-

Can you describe the typical cost estimation workflow in your organization?

Prompt: What are the major stages and decision points?

-

What are the key responsibilities of a cost estimator during the pre-construction and construction phases?

Follow-up: Which internal or external parties are typically involved at each stage?

-

What types of documents or information are exchanged between project stakeholders during the estimation process?

Follow-up 1: What specific information does the estimator need to perform an accurate estimate?

Follow-up 2: From which stakeholders is this information typically obtained?

-

How is information typically exchanged with subcontractors during the estimation process?

Prompt: Project timeline, information type

-

What information is typically included in an initial or conceptual estimate?

Follow-up 1: How is the estimate refined over time? What are the next steps after the initial estimate?

Follow-up 2: How does the estimate evolve or change prior to and during construction?

Prompt: What types of updates occur, what information drives those changes, and who is involved?

-

Do you follow any specific estimation templates or standards?

Prompt: For example, UNIFORMAT II, MasterFormat, or custom formats.

- 7.

-

What are the main burdens or challenges you face in the current estimation workflow?

Prompt: Consider repetitive, manual, time-consuming, or error-prone tasks.

Follow-up 1: Who is typically involved in these burdened tasks?

Follow-up 2: Can you describe these burdens in detail?

Guiding prompt: Why do you consider this task or process burdensome? What factors contribute to its complexity or inefficiency?

- 8.

-

What specific support during the estimation process could benefit from AI-integrated assistance?

Prompt: Where do you believe AI could reduce burden, improve automation, accuracy, or support overall decision-making?

4. Results

4.1. Existing Cost Estimation Workflow

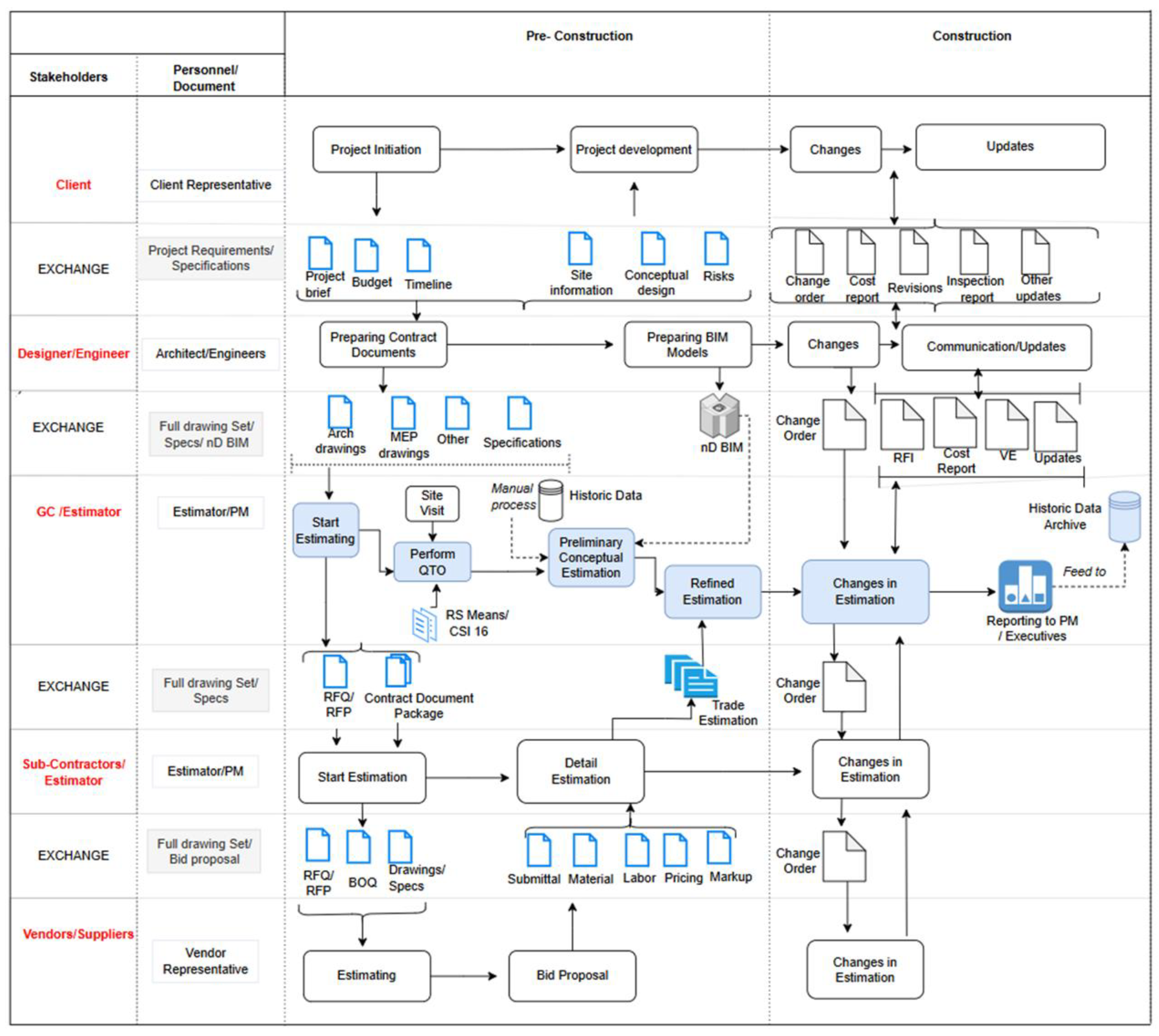

Interview responses from industry professionals and literature combined provided detailed insights into the construction cost estimation workflow, sequence, and stakeholder responsibilities within the process, which were synthesized into the comprehensive workflow map shown in

Figure 2. The workflow is segmented into two primary phases, i) pre-construction and ii) construction, with differences in tasks, document flows, and stakeholder roles. In construction, the project generally starts with the project initiation from the client, where key inputs, such as the project brief, budget, timeline, site information, conceptual design, and risk assessment, are developed and shared with the design team. Architects and engineers then prepare contract documents and generate BIM models, which are the foundational input for downstream estimation activities. During pre-construction, the general contractor (GC) estimator initiates the estimation process using site information, design documents (architectural, MEP, and other specifications), and historical cost data as well as external cost data. A preliminary conceptual estimate is prepared, typically informed by resources like RS Means and in a format such as Uniformat II, and supported by quantity take-offs (QTO) derived either manually from 2D take-off or 3D take-off from BIM. This estimate is refined as the design evolves and more detailed drawings become available, resulting in progressive estimation cycles. Subcontractor estimators and material suppliers, at the same time, create trade-level estimates, typically from RFP or contract plans received from the general contractor. They deliver their inputs in material, labor, markup, and price breakdown, which are eventually forwarded to the more detailed estimates of the GC. The workflow includes frequent exchanges of information across all levels, from project drawings and bid packages to submittals and bills of quantities (BOQs), all shared through iterative exchanges involving contractors, designers, and vendors. During construction, the estimation process continues as change orders, RFIs, cost reports, and value engineering updates are issued. These changes are repetitive and require further revisions to the estimate, which are tracked and reported to project managers and executives and eventually archived for future use after the project is completed. Multiple stakeholders- clients, designers, general contractor, and their estimators, subcontractors, and suppliers- play distinct roles at each step, and their collaboration is facilitated through digital tools and shared documents in digital platforms. Participants emphasized that estimators are central in integrating fragmented inputs from BIM models, drawings, subcontractor pricing, and historical databases to maintain alignment between evolving scope and cost projections. The comprehensive workflow diagram below clearly shows this integration, showing how estimation is not a linear process but a dynamic, feedback-driven process shaped by both internal coordination and external inputs throughout the project lifecycle.

4.2. Burdens in Construction Cost Estimation

To identify burdens in the current construction cost estimation process, this study analyzed responses from expert interviews using the structured questions in sections 2 and 3 of the qualitative instrument. Participants were asked to describe the most repetitive, time-consuming, or error-prone tasks they regularly encounter (“What are the main burdens or challenges you face in the current estimation workflow?”), followed by prompts to explore specific roles involved and to elaborate on why such tasks are burdensome. To collect deeper insights, participants were asked follow-up questions about specific task-level challenges across various estimation stages. Additionally, they were asked to articulate where they envisioned AI providing practical support in relieving those burdens. The analysis process began by collecting all key points in responses into discrete estimation activities aligned with the previously mapped workflow stages (

Section 4.1). Each burden was mapped in order according to when it typically occurs in the estimation timeline, ensuring that identified challenges were grounded in the actual sequence of tasks. Tasks such as quantity aggregation, subcontractor bid evaluation, and change tracking were highlighted as particularly problematic due to their manual nature and data inconsistency. This study then triangulated interview insights with known burden types documented in the literature to describe the nature of each, whether rooted in fragmentation, standardization issues, cognitive overload, or tool limitations. The descriptions for each burden in the final table were synthesized by combining direct participant inputs with thematic patterns identified from the interview analysis. For example, participants commonly described the aggregation of quantities as difficult due to inconsistent formats from 2D and 3D take-offs. This was identified as a burden related to data formatting and manual verification. Similarly, the underutilization of historical enterprise data in current practice was frequently discussed as a missed opportunity. This is due to some factors such as decentralized storage, lack of indexing, and reliance on estimator memory. The burden of cross-referencing project specifications, described as “inefficient and disconnected from estimation platforms,” was identified as a major pain point during the creation of conceptual estimates. Also, tasks such as bid comparison, completeness checks, version control, and managing changes were also described as complex and time-intensive.

To understand the practical relevance of these findings, participants were also asked to describe what kind of AI support could directly help reduce each burden. Their suggestions formed the final column of the result table. These included assistance from AI that could help reduce existing burdens, for example, formatting of quantity data, automated bid evaluation based on standard metrics, conceptual estimate generation based on integrated data sources, change tracking through templated updates, and intelligent version control. These proposed AI interventions were not hypothetical but emerged naturally from the practitioners’ lived experiences and expressed needs. In summary, the burdens listed in

Table 2 were systematically derived by aligning participants’ burden narratives with their position in the workflow, combining participant descriptions with burden characteristics from the literature, and extracting AI-support points directly from interview responses. This method provided a detailed understanding of where current estimation workflows are most challenged and how generative AI could meaningfully intervene.

4.3. Proposed Framework for Generative AI-Based Cost Estimation

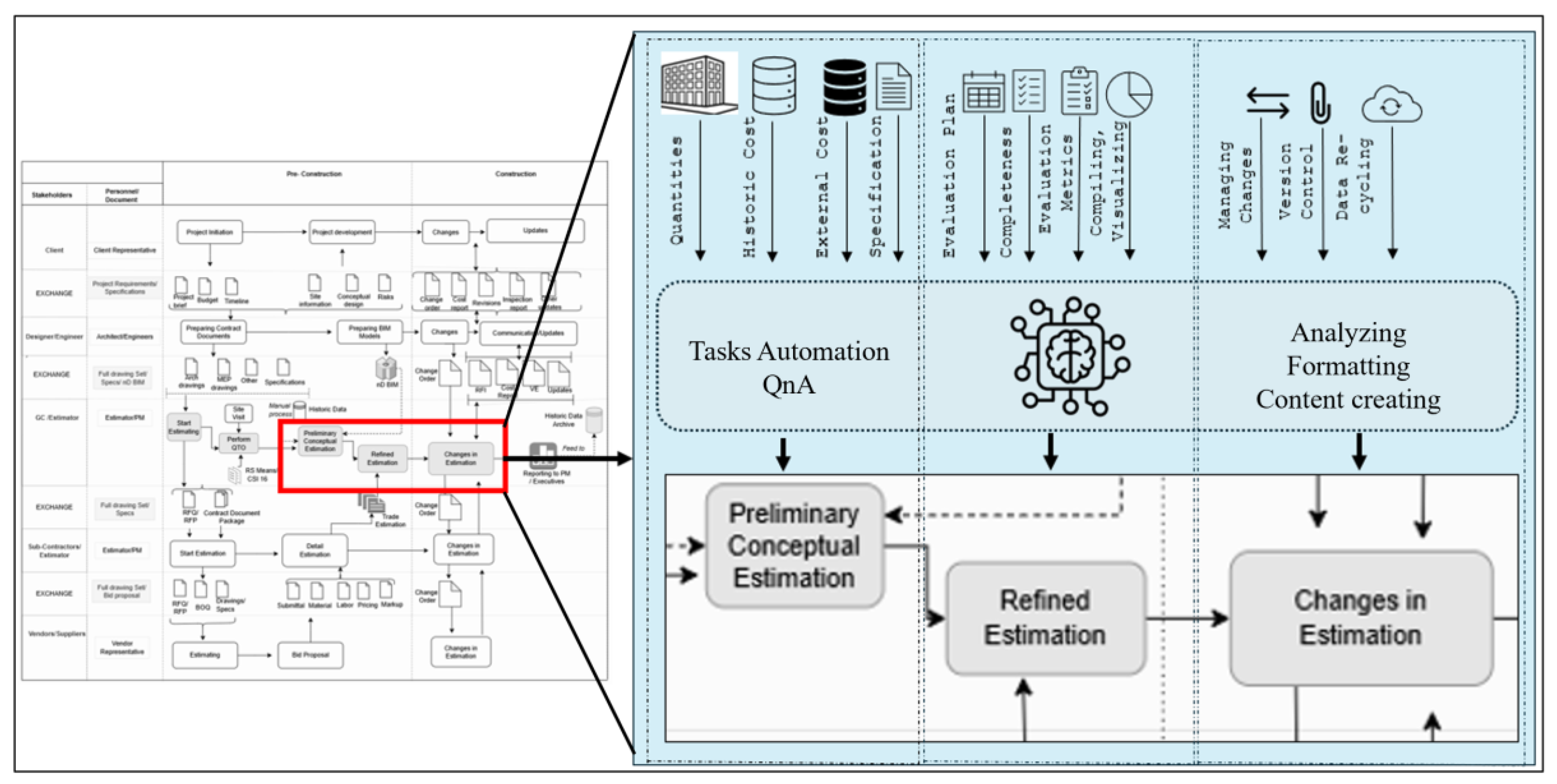

Based on the workflow mapping in

Section 4.1 and the burden points identified in

Section 4.2, this study developed a Generative AI-integrated framework to assist in key burdens during construction cost estimation. The framework was designed by overlaying AI support directly onto the estimation tasks most frequently reported as burdensome by participants. As revealed in the interviews, the majority of burdens occur during the pre-construction phase, with a smaller but essential part emerging during the construction-phase change management. To structure the framework logically, these burden points were grouped into three clusters aligned with the workflow: (1) preliminary conceptual estimation, (2) refined estimation and subcontractor evaluation, and (3) change management and version control. The preliminary conceptual estimation stage involves recurring challenges such as inconsistent quantity formats from 2D/3D sources, underused historical cost data, and manual matching of items in external databases. In this phase, AI assists the estimator by extracting and merging quantity data, verifying it with estimators, and cross-referencing both internal and external cost sources. It can also help interpret item descriptions and generate early estimates based on templates. When historical costs are missing, AI can suggest the closest matches from databases like RS Means, streamlining lookup and improving pricing consistency.

The refined estimation and subcontractor evaluation phase is burdened by inconsistent bid formats, incomplete scopes, and labor-intensive comparisons. AI addresses this by translating diverse inputs into a unified structure, identifying missing items, and checking bid completeness. It can also rank bids using weighted metrics- cost, completeness, past performance, and relationship history- and generate summaries to support faster, more objective decision-making.

During change management and version control, AI supports standardizing change inputs, updating master estimate files, and managing version histories. Estimators complete structured templates, while AI handles file updates, logs modifications, compares versions, and pushes final estimates into enterprise archives- reducing errors and enabling long-term data reuse. As shown in

Figure 3, the framework integrates AI at high-burden points at the center of the workflow-conceptual estimating, bid evaluation, and change tracking. Rather than replacing estimators, it augments their work by automating repetitive and fragmented tasks, aligning AI strengths with industry needs, and laying the groundwork for practical validation.

5. Discussion

This study mapped the construction cost estimation workflow, identified key pain points, and developed a targeted generative AI-integrated framework to address those challenges. The estimation workflow mapped in this study confirms the phased nature of cost estimation-from conceptual estimating to refined estimates and construction-phase updates. However, interviews revealed that despite this structured process, much of the work remains manual, fragmented, and highly dependent on individual estimator expertise-aligning with prior findings that the industry continues to rely on traditional, labor-intensive practices [

3,

25].

The burden themes identified in this study- data fragmentation, inconsistent formats, time pressure, and manual evaluation- support widely reported issues in the literature. For example, underused historical cost data was noted both by interviewees and by researchers such as [

42], who emphasized the inefficiency of scattered legacy cost files. These burdens are not only time-consuming but also risk-prone, reinforcing prior findings that cost estimates are frequently inaccurate due to incomplete or inconsistent input data [

6,

23]. In this study, the proposed GenAI-integrated framework embeds AI precisely where these challenges occur. Unlike generic AI applications, the framework was developed with burden-location- grouping tasks into conceptual estimation, subcontractor evaluation, and change management. This supports the previous literature findings for a “data management system” approach that integrates AI tools within clearly defined estimating stages rather than treating estimation as a monolithic task [

3,

41].

The proposed AI capabilities- standardizing QTO outputs, auto matching cost data, translating bid formats, flagging missing scope, ranking subcontractor bids, and versioning changes- directly reflect support points suggested by practitioners. These functionalities also align with current research trends on intelligent automation in cost workflows. For example, [

8] demonstrated NLP-based tools to extract spec-driven cost items, while Hegazy & Ayed (1998) and Jung et al. (2020) showed that hybrid AI models can outperform traditional methods in capturing complex cost interactions. This study builds on those findings by not only proposing technical features but also embedding them into a real-world workflow validated by industry insights. And more importantly, the proposed framework doesn’t attempt to replace human estimators. Like Smith (2014), this study emphasizes that AI is most effective as a support layer, offloading tedious tasks so human estimators can focus on strategic, interpretive, and decision-making roles. The framework also supports the human-in-the-loop approach recommended by Castro Miranda et al. (2022), ensuring that final estimates remain informed by professional judgment.

In summary, the findings confirm a core issue: construction cost estimation is still constrained by manual effort, dispersed data, and limited reuse of historical knowledge. Although previous research has repeatedly highlighted these burdens, this study contributes by directly tying them to specific tasks and phases and proposing a supporting AI framework. The GenAI-integrated framework provides a practical pathway forward, improving speed, consistency, and scalability while ensuring estimators remain central to the process.

6. Limitations & Future Directions

This study offers multiple contributions by mapping how cost estimation is done in practice, identifying where the biggest pain points (burdens) are, and proposing a generative AI-integrated framework to help address them. However, there are a few limitations to note. Most of the participants came from general contractor backgrounds, which means the perspectives may not fully reflect those of designers, subcontractors, or owners. Including a broader group in future studies would help validate and strengthen the findings. Also, while the framework was carefully built from real-world input and industry experience, it hasn’t yet been tested in practice. The next phase of our study will explore each identified burden deeper, break them down into detailed tasks, and validate their relevance. Also, the proposed AI framework will be further detailed out, refined, and tested using LLMs. The next step will help refine and validate the framework for its potential in assisting estimation tasks and practical usefulness in the construction industry.

7. Conclusion

This study aimed to understand the current workflow of construction cost estimation in the industry and identify the key burdens faced by professionals in practice. And further, explore how generative LLMs could be meaningfully integrated into this process. To achieve this, the research began by mapping the actual estimation workflow through interviews and follow-up discussions with experienced industry professionals, followed by a detailed analysis of task-level challenges encountered across different phases, particularly in the pre-construction stage. Using semi-structured interviews with estimators, project managers, and BIM/VDC experts, the study identified recurring inefficiencies such as fragmented data, repetitive manual work, inconsistent subcontractor inputs, and lack of standardized change management. These findings were then organized into a burden-driven structure that directly informed the design of a proposed GenAI-integrated framework. This framework targets three key components in estimation: preliminary conceptual estimation, subcontractor evaluation, and construction-phase change tracking. AI is positioned not as a replacement but as a supportive layer to assist with quantity extraction, cost referencing, evaluation standardization, and update, ultimately freeing up human estimators to focus on high-value decisions.

While the study provides a clear structure and direction for AI integration in cost estimation, it has some limitations. The participants were primarily from general contracting firms, and the framework, grounded in industry insights, has yet to be formally tested. The next phase of our study will build on this foundation and implement the framework using LLMs.

References

- M. T. Hatamleh, M. Hiyassat, G. J. Sweis, and R. J. Sweis, “Factors affecting the accuracy of cost estimate: case of Jordan,” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 113–131, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Xiao, F. Wang, H. Li, and M. Skitmore, “Modelling the stochastic dependence underlying construction cost and duration,” Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, vol. 24, no. 6, Art. no. 6, 2018.

- H. H. Elmousalami, “Artificial Intelligence and Parametric Construction Cost Estimate Modeling: State-of-the-Art Review,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 146, no. 1, p. 03119008, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghimire, S. Pokharel, K. Kim, and P. Barutha, “Machine learning-based prediction models for budget forecast in capital construction,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Construction, Energy, Environment & Sustainability, Funchal, Portugal, 2023, pp. 27–30.

- X. Xiao, M. Skitmore, W. Yao, and Y. Ali, “Improving robustness of case-based reasoning for early-stage construction cost estimation,” Automation in Construction, vol. 151, p. 104777, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Doloi, “Understanding stakeholders’ perspective of cost estimation in project management,” International Journal of Project Management, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 622–636, July 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghimire, K. Kim, T. Stentz, and T. Roy, “State-of-the-Art Pre-Trained LLMs for Construction Cost Estimation Tasks: A Conceptual Estimation Scenario Using a Modular Chain of Thought (CoT) Approach,” Oct. 15, 2025, Preprints: 2025101060. [CrossRef]

- T. Akanbi and J. Zhang, “Design information extraction from construction specifications to support cost estimation,” Automation in Construction, vol. 131, p. 103835, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Black, A. Akintoye, and E. Fitzgerald, “An analysis of success factors and benefits of partnering in construction,” International Journal of Project Management, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 423–434, Dec. 2000. [CrossRef]

- A. Aibinu and T. and Pasco, “The accuracy of pre-tender building cost estimates in Australia,” Construction Management and Economics, vol. 26, no. 12, pp. 1257–1269, Dec. 2008. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghimire, “Framework for Integrating Industry Knowledge into a Large Language Model to Assist Construction Cost Estimation,” Ph.D., The University of Nebraska - Lincoln, United States -- Nebraska, 2025. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.proquest.com/docview/3198872319/abstract/D556793967F749FCPQ/1.

- Krzysztof Zima and Agnieszka Leśniak, “Limitations of Cost Estimation Using Building Information Modeling in Poland,” JCEA, vol. 7, no. 5, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. Shehab, N. Blampied, E. Nasr, and L. Sindhu, “ANN-based estimation model for the preconstruction cost of pavement rehabilitation projects,” International Journal of Construction Management, vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–8, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S.-H. Ji, J. Ahn, E.-B. Lee, and Y. Kim, “Learning method for knowledge retention in CBR cost models,” Automation in Construction, vol. 96, pp. 65–74, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Karatas and F. Ince, “Fuzzy expert tool for small satellite cost estimation,” IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 28–35, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, R. E. Minchin, and D. Agdas, “Forecasting Completed Cost of Highway Construction Projects Using LASSO Regularized Regression,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 143, no. 10, p. 04017071, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Petruseva, P. Sherrod, V. Zileska Pancovska, and A. Petrovski, “Predicting Bidding Price in Construction using Support Vector Machine,” TEM Journal, pp. 143–151, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- Z. H. Ali and A. M. Burhan, “Hybrid machine learning approach for construction cost estimation: an evaluation of extreme gradient boosting model,” Asian J Civ Eng, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 2427–2442, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Clark, “A Framework for BIM Model-Based Construction Cost Estimation,” California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, California, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Hegazy and A. Ayed, “Neural Network Model for Parametric Cost Estimation of Highway Projects,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 124, no. 3, pp. 210–218, May 1998. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghimire, K. Kim, and M. Acharya, “Opportunities and Challenges of Generative AI in Construction Industry: Focusing on Adoption of Text-Based Models,” Buildings, vol. 14, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Castro Miranda, E. Del Rey Castillo, V. Gonzalez, and J. Adafin, “Predictive Analytics for Early-Stage Construction Costs Estimation,” Buildings, vol. 12, no. 7, Art. no. 7, July 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Flyvbjerg, Holm ,Mette Skamris, and S. and Buhl, “Underestimating Costs in Public Works Projects: Error or Lie?,” Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 279–295, Sept. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro and J. Poças Martins, “A survey on modeling guidelines for quantity takeoff-oriented BIM-based design,” Automation in Construction, vol. 35, pp. 238–253, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Olatunji, W. Sher, and N. Gu, “BUILDING INFORMATION MODELING AND QUANTITY SURVEYING PRACTICE,” vol. 15, no. 1, 2010.

- D. Forgues, I. Iordanova, F. Valdivesio, and S. Staub-French, “Rethinking the Cost Estimating Process through 5D BIM: A Case Study,” pp. 778–786, July 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. Smith, “BIM & the 5D Project Cost Manager,” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 119, pp. 475–484, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghimire, S. Pokharel, K. Kim, and P. Barutha, MACHINE LEARNING-BASED PREDICTION MODELS FOR BUDGET FORECAST IN CAPITAL CONSTRUCTION. 2023.

- M. Barakchi, O. Torp, and A. M. Belay, “Cost Estimation Methods for Transport Infrastructure: A Systematic Literature Review,” Procedia Engineering, vol. 196, pp. 270–277, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Fazil, C. K. Lee, and P. F. M. Tamyez, “COST ESTIMATION PERFORMANCE IN THE CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS,” International Journal of Industrial Management, vol. 11, pp. 217–234, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Zani, B. T. Adey, and S. Carroll, “An approach to support reference class forecasting when adequate project data are unavailable,” Results in Engineering, vol. 22, p. 102333, June 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Tayefeh Hashemi, O. M. Ebadati, and H. Kaur, “Cost estimation and prediction in construction projects: a systematic review on machine learning techniques,” SN Appl. Sci., vol. 2, no. 10, p. 1703, Sept. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Fortune and O. Cox, “Current practices in building project contract price forecasting in the UK,” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 446–457, Jan. 2005. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Ahiaga-Dagbui and S. D. Smith, “Rethinking construction cost overruns: cognition, learning and estimation,” Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 38–54, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Woodhead, T. Davis, and R. Walker, “Collaborative Construction Contracts,” Alta. L. Rev., vol. 61, p. 307, 2024 2023.

- P. E. D. Love, D. J. Edwards, and Z. Irani, “Work Stress, Support, and Mental Health in Construction,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 136, no. 6, pp. 650–658, June 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y. Brenda and R. and Steve, “Coping Strategies among Construction Professionals: Cognitive and Behavioural Efforts to Manage Job Stressors,” Journal for Education in the Built Environment, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 70–79, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Bilal et al., “Big Data in the construction industry: A review of present status, opportunities, and future trends,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 500–521, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Akintoye and E. and Fitzgerald, “A survey of current cost estimating practices in the UK,” Construction Management and Economics, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 161–172, Mar. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Swei, J. Gregory, and R. Kirchain, “Construction cost estimation: A parametric approach for better estimates of expected cost and variation,” Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, vol. 101, pp. 295–305, July 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Emmanuel, “A Systematic Literature Review on Cost Forecasting Techniques for Improving Estimates Accuracy in Construction Projects,” Environmental Technology and Science Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Adanza Dopazo, L. Mahdjoubi, and B. Gething, “A Method to Enable Automatic Extraction of Cost and Quantity Data from Hierarchical Construction Information Documents to Enable Rapid Digital Comparison and Analysis,” Buildings, vol. 13, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Creswell and V. L. P. Clark, Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. SAGE Publications, 2017.

- Lauterbach, “Hermeneutic Phenomenological Interviewing: Going Beyond Semi-Structured Formats to Help Participants Revisit Experience,” TQR, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Yeong, R. Ismail, N. H. Ismail, and Mohd. I. Hamzah, “Interview Protocol Refinement: Fine-Tuning Qualitative Research Interview Questions for Multi-Racial Populations in Malaysia,” TQR, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Jung, J. Pyeon, H.-S. Lee, M. Park, I. Yoon, and J. Rho, “Construction Cost Estimation Using a Case-Based Reasoning Hybrid Genetic Algorithm Based on Local Search Method,” Sustainability, vol. 12, p. 7920, Sept. 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).