1. Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD; formerly NAFLD) is extremely common affecting about 38% of adults worldwide and tightly linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [

1]. Despite the vast literature, the conceptual rationale for interdisciplinary care remains fragmented, and limited consensus model currently bridges mechanistic evidence with real-world pathways.

MASLD spans simple steatosis to metabolic steatohepatitis (MASH), fibrosis and cirrhosis, and is an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic CVD [

1,

2,

3]. Indeed, cardiovascular complications are now the leading cause of death in MASLD, underscoring the need to manage liver and cardiometabolic disorders together [

1,

2].

Previous studies Explains the necessity of an interdisciplinary approach, drawing on hepatology, cardiology, endocrinology, and internal medicine specialists to understand the intricate interplay between MASLD and coronary artery disease (CAD) [

1]. However, describing necessity is not equivalent to demonstrating clinical value, and existing reports rarely define measurable endpoints or quality benchmarks for integration. The present review therefore advances a central thesis: interdisciplinary integration should not be viewed as a logistical convenience but as a disease-modifier. Recent studies in the literature show that the interdisciplinary framework aims to delineate the intricate relationship between MASLD and CAD, which are strongly linked by shared cardiometabolic risk factors and potentially a causal relationship [

1,

4]. Yet most available literature stops at mapping associations rather than interrogating how integrated models can modify risk trajectories.

The scientific problem underpinning this review is therefore to determine whether a structured, multispecialty approach meaningfully alters detection, stratification, or treatment of cardiometabolic risk in MASLD. By reframing MASLD as a multisystem disorder, we propose a clinically actionable framework that connects pathophysiology to implementation pathways.

Studies also suggest that synthesizing the available evidence through this integrated approach offers unique insights into

novel opportunities for targeted interventions and personalized management strategies for both diseases [

1].

A recently proposed Cardiovascular–Renal–Hepatic–Metabolic (CRHM) syndrome, had beend defined as a holistic framework that integrates the liver to address the global burden of cardiometabolic disorders more effectively [

5].

Cusi et al. [

6] recommended the development of interprofessional teams, including endocrinologists, hepatologists, and other specialists, to manage both the hepatic and extrahepatic conditions associated with diabetes and MASLD. They also define MASLD as steatotic liver disease in the presence of at least one cardiometabolic risk factor, directly linking the liver condition with cardiometabolic pathways.

However, despite extensive descriptive epidemiology, a central unanswered question persists: why does integrating cardiometabolic and hepatic care materially change patient outcomes beyond conventional single-organ management? This review addresses this gap by examining the mechanistic, diagnostic, and clinical rationale for treating MASLD not as an isolated liver disease but as a systemic cardiometabolic disorder.

This review surveys recent developments in the interdisciplinary clinical care of MASLD, with emphasis on integrated care models, novel diagnostics, and emerging therapies bridging hepatology, endocrinology, cardiology and primary care. Building on these findings, we propose that MASLD care must adopt a phenotype-driven approach rather than a single unified pathway. Phenotypes such as metabolic-dominant, fibrosis-dominant, cardiac-dominant, and mixed-risk could guide referral thresholds. This framework more closely aligns with known mechanistic heterogeneity and provides actionable stratification.

Accordingly, the goal is not to summarize MASLD broadly but to interrogate the rationale, evidence quality, and practical models that support or challenge integrated care. This focus enables a shift from descriptive epidemiology toward a hypothesis-driven synthesis. In doing so, this review identifies conceptual gaps that currently prevent MASLD from being incorporated into standard cardiometabolic care pathways. The remainder of the review is structured to progressively move from rationale to mechanisms, evidence appraisal, and implementation models to support a unified framework.

2. Epidemiology and Burden of MASLD and Cardiometabolic Comorbidities

To understand why integrated care is justified, the epidemiology must be linked to actionable clinical failures rather than described in isolation. MASLD is now the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide. From 2010 to 2021, the number of cases grew by 25%, affecting about 38% of adults in some regions. This rise is tied to the obesity epidemic and metabolic syndrome [

7]. Yet rising prevalence alone does not explain the persistently high rates of missed diagnosis, which is where interdisciplinary pathways become relevant. However, much of the global burden data is retrospective and sensitive to diagnostic coding variability, reducing certainty regarding true incidence trajectories.

Cardiometabolic diseases are often concurrent with MASLD, making the overall burden heavier [

8]. For instance, up to 70% of MASLD patients have T2D or high cholesterol [

9]. These estimates are derived largely from tertiary-center cohorts, which may inflate comorbidity rates compared with population-based registries.

While hepatic-related diseases are important in these patients, cardiometabolic diseases are the top causes of mortality[

8]. A recent global study found that metabolic risks led to over 200,000 liver cancer cases in 2021, many linked to MASLD [

10]. Nevertheless, attributing causality to MASLD remains challenging because confounders such as metabolic syndrome severity are incompletely adjusted in most analyses. Moreover, regional heterogeneity in diagnostic access introduces ascertainment bias that limits the generalizability of epidemiologic projections. This variability underscores the need to interpret global burden estimates with caution and highlights the importance of standardized screening frameworks.

These cancers are more common in people with diabetes and obesity[

10]. In developed countries, MASLD-related cardiovascular diseases cost billions in treatments. Women and certain ethnic groups, like Hispanics, face higher risks [

7].

The disease starts silently but can lead to cirrhosis in 20-30% of cases[

9]. When combined with heart failure, survival drops significantly [

8]. Recent data show that MASLD increases heart failure risk by 1.5 times [

8]. This is because liver fat affects blood flow and causes inflammation in arteries [

8]. In Asia and Europe, surveys reveal poor coding for MASLD in medical records, leading to underdiagnosis. Better classification codes could help track the cardiometabolic links. For instance, using ICD codes for metabolic fatty liver would improve data on heart comorbidities [

11]. The burden is not just physical; it affects mental health and daily life. Patients often have fatigue and depression from both liver and heart strain [

12].

Global estimates predict a 50% increase in MASLD by 2030, with cardiometabolic deaths rising too [

7]. This calls for urgent interdisciplinary screening [

1]. In low-income areas, access to care is limited, worsening outcomes [

10]. Studies highlight that integrated programs could cut complications by 30% [

13]. Overall, the dual burden of liver and heart disease in MASLD demands a team-based response [

1].

3. Pathophysiological Links Between MASLD and Cardiometabolic Diseases

Mechanisms provide the bridge between epidemiology and clinical decision-making. MASLD and cardiometabolic diseases share common pathways that explain their connection [

8]. Notably, many mechanistic pathways remain hypothesized rather than experimentally validated in humans in large cohorts. Insulin resistance is a key player, where cells do not respond to the insulin, leading to high blood glucose, gluconeogenesis, and

de novo Lipogenesis [

8]. In the liver tissue, these process causes steatosis, which is fat accumulation and could lead to steatotic liver disease [

9].

Sebastiani et al. [

14] in their study proposed that integrating Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR) into MASLD care to address the shared metabolic and inflammatory drivers of both hepatic and cardiovascular conditions. Their study suggests that CR, viewed as a multidisciplinary framework, is uniquely positioned to manage the complex needs of MASLD patients by incorporating structured lifestyle modification, pharmacologic interventions, and patient education.

Excessive hepatic fat accumulation leads to the secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, which induce systemic inflammation and contribute to endothelial dysfunction in blood vessels as well as adverse cardiac remodeling in the heart [

8]. However, these links are predominantly derived from cross-sectional designs and small mechanistic studies lacking temporal resolution.

Oxidative stress, from unbalanced free radicals, damages liver cells and promotes atherosclerosis in arteries. Galectin-3 is higher in MASLD and worsens liver fibrosis while also affecting heart function. It binds to cells and triggers scarring in both organs [

15]. Galectin domains are important in heart diseases like heart failure [

16,

17]. Yet galectin-3 levels are influenced by renal function, age, and adiposity, complicating its interpretation as a MASLD-specific biomarker.

Inflammation from the liver reaches the cardiomyocytes via cytokines, like TNF-alpha, causing cardiomyocytes' defects. This leads to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, common in MASLD patients [

8,

18]. Dyslipidemia in combination with MASLD make plaques and blocks arteries while the cholesterol raises [

9]. Moreover, lipid metabolism and intake could be associated with liver fibrosis [

19]. Hypertension often joins in, as liver issues disrupt salt balance [

8].

Gut microbiome changes in MASLD leak toxins into the blood, regulating systemic inflammation [

1,

20]. Still, microbiome studies often suffer from batch effects, limited reproducibility, and geographic biases. However, despite extensive mechanistic insights, there is a paucity of longitudinal clinical studies validating how targeting these pathways translates into improved cardiometabolic outcomes in MASLD patients, highlighting a critical gap in evidence-based interdisciplinary strategies. These links mean treating one disease affects the other [

14]. For example, there is a piece of evidence that shows liver steatosis affects cardiomyocytes [

8]. Biomarkers like Mac-2 binding protein help measure fibrosis in liver and predict heart risks. It rises in advanced MASLD and correlates with cardiac events [

21].

Polyphenols from diet can activate AMPK, a pathway that fights inflammation in both liver and heart [

22,

23]. Resveratrol, a compound, reduces liver fat and improves heart health by lowering oxidative stress. In mouse models, it enhanced statin effects on NAFLD, showing metabolic benefits [

24,

25]. Concurrent viral hepatitis, including Hepatitis C, can worsen MASLD, but agents like oleuropein protect the liver during infection [

22]. These pathways highlight why isolated care and tunnel vision fail [

1]. However, translating these mechanistic insights into clinical algorithms requires prospective validation, which remains scarce. Recent reviews confirm that MASLD acts as a "hepatic manifestation" of metabolic syndrome [

8]. Understanding this helps design better treatments [

26].

Besides, liver-heart communication integrates hepatokines and cardiokines. Considering such pathways provides a holistic insight into the cross-talk between these organs in cardiometabolic disease [

27].

Although the mechanistic links between MASLD and cardiometabolic diseases are increasingly well-characterized, most available studies rely on observational or cross-sectional designs, limiting causal inference. Many frequently cited biomarkers such as galectin-3 and M2BPGi are supported by small studies, often lacking adjustment for crucial confounders including visceral adiposity, genetic polymorphisms, or medications that influence metabolic pathways [

15,

21].

Moreover, animal models demonstrating benefits of polyphenols or agents like resveratrol frequently fail to replicate the heterogeneous phenotypes seen in real-world MASLD, where patients present with overlapping endocrine, vascular, and hepatic dysregulation.

Current literature tends to overstate mechanistic certainty despite substantial between-study variability, highlighting a need for rigorously standardized methodology, multi-omics validation, and prospective interdisciplinary trials before these pathways can reliably inform clinical decision-making.

4. Interdisciplinary Care Models and Programs

Clinical models operationalize these mechanisms into real workflows, forming the translational step lacking in many MASLD pathways. Optimal MASLD care requires multidisciplinary collaboration between hepatologists, diabetologists, endocrinologists, cardiologists and primary care [

2,

12]. However, awareness of MASLD among non-liver specialists remains low [

12]. For example, Canadian experts note that until recently Canada had no national MASLD guidelines and only patchy diagnostic access, hampering integrated care [

12].

Similarly, in the US only about 30% of academic centers have dedicated multidisciplinary MASLD clinics [

28]. Nonetheless, several models have been trialed. Stine et al. established a “one-stop” MASLD clinic in Pennsylvania that co-locates hepatology, endocrinology, nutrition and other specialists in a single visit [

28].

In patients followed several months, significant improvements were seen in liver enzymes, glycemic control, lipids and blood pressure [

28]. Similarly, integrating MASLD management into cardiac rehabilitation has been proposed to leverage exercise or diet programs for dual liver and heart benefit [

14]. In heart failure care, recent guidance emphasizes co-management of MASLD by cardiologists and hepatologists, noting shared pathophysiology and the need for coordinated treatment plans [

2].

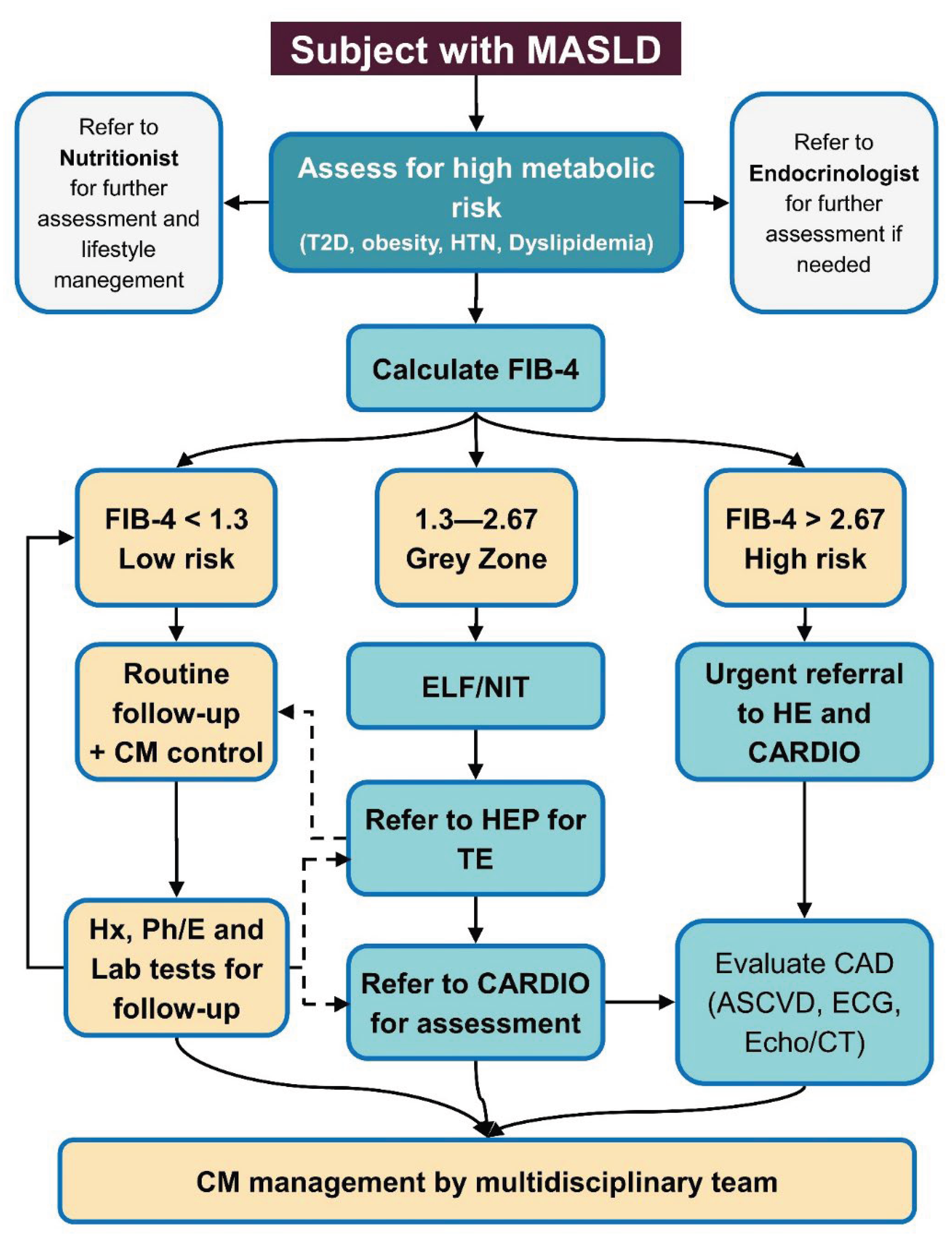

Despite such successes, no single model is yet standard; experts lament that multidisciplinary programs “are rarely co-located” and core specialists are often missing (

Figure 1) [

28]. Broadly, these reports stress that siloed care is ineffective and call for systemic changes (education, clinical pathways, co-management guidelines) to deliver holistic MASLD care alongside obesity, diabetes and CVD treatment [

12,

29].

5. Diagnostic Strategies and Biomarkers

Diagnostics determine who enters the care pathway and when interdisciplinary escalation is warranted. Virtual multidisciplinary model based in primary care to deliver holistic patient-centered care for patients with MASLD and associated metabolic diseases, including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes had been advocated previously [

26].

Moreover, the importance of diagnosing MASLD in patients with type 2 diabetes, early chronic kidney disease, or cardiovascular disease to assess candidacy and prioritization for management, thereby explicitly linking hepatic and cardiometabolic conditions also had been emphasized [

26]. Consequently, a well-shaped multidisciplinary models of clinical care must be integrates a team to reduce the burden of MASLD and increase diagnosis rate [

26].

Advances in MASLD diagnosis focus on noninvasive testing (NIT) and biomarkers to enable early detection in high-risk patients. Contemporary guidelines recommend screening at-risk individuals (e.g., with T2D or obesity) using sequential NITs (serum scores then imaging) to detect fibrosis [

9,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Nonetheless, most screening evidence is low-to-moderate certainty because outcomes are rarely hard clinical endpoints. For instance, FIB-4 or NAFLD fibrosis score (based on age, enzymes, platelets) are first-line, followed by transient elastography (FibroScan) or MRI elastography to confirm fibrosis [

9,

34,

35,

36].

These approaches reduce reliance on biopsy [

29] and allow primary care physicians to rule in or rule out advanced disease. Novel biomarkers are emerging; a study developed the

N3-MASH panel (CXCL10, CK-18 fragments and BMI), achieving an AUROC of 0.95 for distinguishing MASLD from controls [

37]. A larger

N7-MASH panel further improved accuracy (AUROC about 0.98) [

37]. Despite promising AUROC values, external validation of these panels remains insufficient.

Multi-omics studies have identified new candidates: a gut microbiome or metabolome analysis found that stool glycerophospholipid levels and specific bacteria (e.g.,

Parabacteroides merdae) correlate with MASLD, suggesting early noninvasive biomarkers [

38]. Small sample sizes and lack of longitudinal follow-up constrain the immediate clinical utility of multi-omics signatures. Furthermore, microRNAs (miR) showed a shared regulator and as a result a correlation between irritable bowel syndrome and MASLD [

39].

Moreover, machine-learning methods to combine routine data (labs, demographics, imaging) are under investigation for risk stratification. In all cases, primary-care implementation remains a challenge. Recent reviews note that primary clinicians must be empowered to screen early (e.g., using reflex FIB-4 alerts for diabetics), but uptake is limited [

9,

29]. So, stepwise NIT algorithms are now endorsed in guidelines [

9], while promising new biomarkers (serologic panels and metabolomic signatures) are on the horizon to enhance early MASLD detection [

37,

38]. At present, limited biomarkers have definitively demonstrated added prognostic value beyond established clinical scores in real-world MASLD populations. It warrants future investigation whether sequential NIT pathways should be redefined as triage mechanisms for multidisciplinary escalation rather than tools for fibrosis detection alone.

6. Therapeutic Strategies and Pharmacology

Therapeutics illustrate how multispecialty management modifies disease trajectory rather than merely treating isolated phenotypes. Lifestyle modification remains the cornerstone of MASLD management: weight loss (10% weight reduction), Mediterranean diet, and regular exercise improve liver steatosis and fibrosis risk. Interdisciplinary care emphasizes simultaneous management of comorbidities [

9,

40]. However, adherence rates in real-world cohorts remain suboptimal, and most trials exclude patients with severe comorbidities.

Guidelines now explicitly recommend using anti-obesity or T2D medications that benefit the liver. Incretin-based therapies have shown striking effects: semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly (approved for weight loss) achieved MASH resolution in about 62% of patients vs about 34% on placebo in a phase 3 trial [

41]. These trials primarily assess histologic endpoints rather than long-term cardiometabolic outcomes. Similarly, the dual GLP-1/GIP agonist tirzepatide induced MASH resolution in 44–62% (dose-dependent) versus 10% with placebo, and doubled rates of fibrosis improvement [

42]. Furthermore, dropout rates and variable definitions of MASH resolution complicate cross-trial comparisons. These results herald GLP-1R agonists as key anti-steatohepatitis drugs.

Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors also show promise. A large real-world study on MASLD patients found SGLT2i use (mostly empagliflozin, dapagliflozin) led to better BMI, ALT and HbA1c after 1 year, and over 10 years dramatically reduced mortality, CV events and progression to cirrhosis [

43].

The cardiovascular and anti-inflammatory benefits of SGLT2i likely translate into hepatoprotection [

43]. Other pharmacotherapies are entering practice. In March 2024, the thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist

resmetirom received FDA approval for noncirrhotic MASH with fibrosis [

44,

45]; it improved steatohepatitis and fibrosis in trials, representing the first MASLD-specific drug [

9,

28]. Research continues on novel agents: efruxifermin (an FGF21 analog) showed some fibrosis regression in preliminary trials, but in a recent phase 2b trial did

not significantly reduce fibrosis in MASH cirrhosis [

46].

Combinations of these agents (e.g., GLP-1 plus FGF21) are also under study. Other approaches, e.g., thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone), vitamin E, remain options for selected patients with MASH and T2D (as per older NAFLD guidance), though are not MASLD-specific. Overall, MASLD therapeutics now emphasize drugs that also treat obesity and diabetes [

9,

43]. Thus, although pharmacotherapy is rapidly evolving, its integration into multispecialty pathways remains underexplored. Therapeutic choices should be embedded into an integrated algorithm rather than selected independently by separate specialists.

7. Implementation Challenges and Health System Perspectives

Implementation exposes where theory fails when confronted with real-world constraints. Despite new tools, translating MASLD care into practice faces barriers. Studies show wide variation in care delivery: a UK audit (2019–2022) of 34 centers found that only about 28% of patients had fibrosis staging at referral, and statins were discussed in just 9.1% of MASLD patients with high CV risk [

47].

Driessen and colleagues [

8] warranted comprehensive cardiometabolic risk management, preferably using a multidisciplinary approach, for patients with MASLD given the common drivers and increased rate of cardiovascular events.

Lifestyle counseling was often under-documented (<56% received exercise advice) [

47]. Similarly, only about 30% of U.S. centers have multidisciplinary MASLD programs [

28]. Key barriers include lack of awareness among primary physicians, limited hepatology resources, and historically siloed specialty training. Internationally, guidelines from hepatology societies (EASL, APASL) and diabetes societies are beginning to raise MASLD awareness, but time lags remain. Innovative education models are emerging: for example, the “Project ECHO” tele-mentoring program is training primary care in an integrated obesity and MASLD curriculum [

48].

Success requires system-level support. The Canadian review calls for

cross-disciplinary education, unified care pathways and resources to ensure timely diagnosis and “holistic” management [

12]. Consequently, implementation success is mixed: where multidisciplinary clinics are available, outcomes improve [

14], but many health systems still struggle to embed MASLD screening and co-management of cardiometabolic risk.

Based on synthesized evidence, we suggest a simplified clinical pathway linking primary care, diabetology, cardiology, and hepatology. This model includes three essential steps: early risk flagging, phenotype assignment, and specialty-matched intervention. Such a pathway could harmonize diverse practices into a coherent clinical workflow. Embedding this approach into electronic health systems offers an implementable route to system-level scaling. This contribution addresses the current absence of a unifying conceptual framework in the MASLD literature. This insight forms the conceptual foundation for the broader interdisciplinary architecture described throughout the manuscript.

8. Challenges and Future Directions

Several tensions emerge from the current evidence. First, mechanistic clarity is advancing rapidly, yet clinical translation lags behind. Second, diagnostic tools have expanded, but their integration into stepwise care pathways remains inconsistent. Third, although interdisciplinary clinics show promise, existing data are heterogeneous and rarely compare integrated versus conventional models. Fourth, implementation barriers such as reimbursement, specialist shortages, and inconsistent guidelines impede adoption. These gaps prevent a unified, evidence-based approach to cardiometabolic risk management in MASLD. Future work should prioritize pragmatic trials evaluating care pathways rather than individual biomarkers or therapies. Comparative effectiveness studies are needed to define which combinations of specialists confer measurable benefit. Longitudinal cohorts must incorporate multi-organ outcomes rather than liver endpoints alone. Health-system interventions such as integrated referral pathways, automated FIB-4 alerts, and shared electronic records warrant evaluation. Without such data, multidisciplinary care risks remaining a conceptual ideal rather than a standardized practice. In particular, the field lacks a validated framework to match MASLD phenotypes with specific cardiometabolic interventions. Genetic modifiers such as PNPLA3 or TM6SF2 may require tailored pathways distinct from metabolically driven MASLD. Economic analyses are also missing; no study has quantified system-level cost savings from integrated care. Furthermore, equity issues must be addressed, as integrated care is disproportionately available in high-resource settings. Telemedicine-driven models could democratize interdisciplinary care but remain understudied. Digital decision support may enhance risk stratification, but external validation is lacking. Ultimately, the field must decide whether MASLD is to be treated as a hepatic disorder with metabolic manifestations or vice versa. This conceptual positioning will dictate future research priorities, screening policies, and integration models. Clarifying this identity is essential for the maturation of MASLD care.

Together, these sections reveal a mismatch between scientific knowledge and delivery systems. Although advantages are evident, obstacles persist in the implementation of interdisciplinary care [

1]. Insufficient awareness results in fragmented or siloed treatment approaches [

11]. Educational and training programs can address this issue [

14]. Variations in cost and accessibility differ across regions [

7].

International consensus advocates for the adoption of standardized protocols [

13]. Ongoing research into biomarkers will enable more precise risk stratification. The application of artificial intelligence in predictive modeling holds considerable promise [

13]. Clinical trials evaluating combination therapies are essential [

8]. Reforms in coding policies will facilitate improvements [

11].

Consequently, interdisciplinary approaches have the potential to revolutionize the management of MASLD. MASLD is intimately associated with cardiometabolic diseases, necessitating a team-based care model [

1].

Epidemiological evidence indicates an escalating burden [

7]. Pathophysiological mechanisms elucidate the shared risk factors [

8]. Diagnostic methodologies are advancing [

9]. Integrated management incorporating lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy yields optimal results [

14]. Although challenges persist, prospective integrated strategies will augment clinical practice [

13].

This comprehensive perspective enhances patient outcomes [

14]. Healthcare professionals should implement this approach promptly to preserve lives [

1]. multidisciplinary management should involve collaboration among hepatologists, endocrinologists, cardiologists, general physicians, and allied health professionals like diet and lifestyle experts [

8]. Only by aligning mechanisms, diagnostics, models, and systems does interdisciplinary care become more than an aspirational concept. This narrative integration is essential because fragmented reporting mirrors fragmented care.

9. Conclusions

In conclusion, an interdisciplinary strategy addressing cardiometabolic disorders holds substantial transformative potential in the management of MASLD by comprehensively tackling its multifaceted pathophysiology. MASLD sits at the nexus of liver, metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Recent literature consistently emphasizes that multidisciplinary management, spanning weight control, diabetes and CVD therapies, is essential. New clinical models (integrated clinics, cardiac rehab engagement) and telehealth education (ECHO) show promise, as do emerging diagnostics (noninvasive panels, metabolomics) and therapies (GLP-1/GIP agonists, SGLT2i, thyroid hormone analogs). The challenge ahead is broadly implementing these advances. Coordinated care protocols, expanded specialist availability, and aligned guidelines across disciplines will be key to improving outcomes for patients with MASLD and cardiometabolic comorbidities. Through the cultivation of interspecialty collaboration, healthcare professionals can facilitate expedited diagnostic identification, more efficacious therapeutic interventions, and optimized patient outcomes, thereby attenuating the global epidemiological burden of this condition. The adoption of integrated care paradigms not only elevates the standards of clinical practice but also endows patients with the agency to holistically manage their comorbid conditions, thereby promoting enduring health and enhanced quality of life. Amid the escalating prevalence of MASLD, the implementation of such approaches is imperative to redress deficiencies in contemporary therapeutic frameworks and to engender innovative, patient-centered advancements.

Author Contributions

MS: Reviewing the literature, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – the original draft, Writing – review & and editing; SH: Reviewing the literature, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – the original draft, Writing – review & and editing.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of a part of this work, we used LLMs (AI) for paraphrasing and grammar checking. Following the use of this tool, the author thoroughly reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the final version of the publication.

References

- Gries, J.J.; Lazarus, J.V.; Brennan, P.N.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Targher, G.; Lang, C.C.; Virani, S.S.; Lavie, C.J.; Isaacs, S.; Arab, J.P.; et al. Interdisciplinary perspectives on the co-management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and coronary artery disease. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 10, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, J.J.; Chen, B.; Bansal, M.B.; Rodriguez, M.; Alqahtani, S.A.; Brennan, P.N.; Lang, C.C.; Tang, W.H.W.; Lazarus, J.V.; Krittanawong, C. Guideline-directed medical strategies for the co-management of heart failure and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Yilmaz, Y.; Valenti, L.; Seto, W.; Pan, C.Q.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Ye, F.; Sookoian, S.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; et al. Global Burden of Major Chronic Liver Diseases in 2021. Liver Int. 2025, 45, e70058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrao, S.; Calvo, L.; Granà, W.; Scibetta, S.; Mirarchi, L.; Amodeo, S.; Falcone, F.; Argano, C. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A pathophysiology and clinical framework to face the present and the future. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 35, 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Guzmán, J.E.; Belmont-Hernández, R.A.; Chávez-Tapia, N.C.; Uribe, M.; Nuño-Lámbarri, N. Metabolic-Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusi, K.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Apovian, C.M.; Balapattabi, K.; Bannuru, R.R.; Barb, D.; Bardsley, J.K.; Beverly, E.A.; Corbin, K.D.; ElSayed, N.A.; et al. Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) in People With Diabetes: The Need for Screening and Early Intervention. A Consensus Report of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, 1057–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Yilmaz, Y.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Lesmana, C.R.A.; Adams, L.A.; Boursier, J.; Papatheodoridis, G.; El-Kassas, M.; et al. Global burden of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, 2010 to 2021. JHEP Rep. 2024, 7, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driessen S, Francque SM, Anker SD, Cabezas MC, Grobbee DE, Tushuizen ME, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and the heart. Hepatology 2025, 82, 487–503. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liver EAftSot, Diabetes EAftSo. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Obesity Facts 2024, 17, 374–444. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Mao, Y.; Cheung, T.T.; Yilmaz, Y.; Valenti, L.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Sookoian, S.; Chan, W.-K.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Primary Liver Cancer Attributable to Metabolic Risks: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2021. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 120, 2280–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Kim, S.U.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Valenti, L.; Glickman, M.; Ponce, J.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Crespo, J.; et al. A global survey on the use of the international classification of diseases codes for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 2024, 18, 1178–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Raggi, P.; Carreau, A.; Wharton, S.; Cheng, A.Y.Y.; Swain, M.G. A review of multidisciplinary care in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and cardiometabolic disease, with a focus on Canada. Diabetes, Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 6831–6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Lazarus, J.V.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Yilmaz, Y.; Duseja, A.; Eguchi, Y.; Castera, L.; Pessoa, M.G.; Oliveira, C.P.; et al. Global Consensus Recommendations for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2025, 169, 1017–1032.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, G.; Raggi, P.; Guaraldi, G. Integrating the Care of Metabolic Dysfunction–associated Steatotic Liver Disease Into Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Multisystem Approach. Can. J. Cardiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M. Galectin-3 and Severity of Liver Fibrosis in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Protein Pept. Lett. 2024, 31, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M.J.; Mirahmadi, S.-M.; Pirhayati, M.; Azarbad, R.; Nematollahi, S.; Taghizadeh, M.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H. Understanding the Role of Galectin-1 in Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2024, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotoudeheian, M. LBPS 02-05 ATRIAL FIBRILLATION IMMUNOLOGICAL DETERMINANTS: ROLE OF GALECTIN-3. Journal of Hypertension 2016, 34, e507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M. The Interplay Between Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Heart Failure: Mechanisms, Associations, and Clinical Implications. 2024.

- Sotoudeheian, M.; Azarbad, R.; Mirahmadi, S.-M. Investigating the correlation between polyunsaturated fatty acids intake and non-invasive biomarkers of liver fibrosis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 63, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzbicka-Rucińska, A.; Konopka, E.; Więckowski, S.; Jańczyk, W.; Świąder-Leśniak, A.; Świderska, J.; Trojanek, J.; Kułaga, Z.; Socha, P.; Bierła, J. Evaluation of Defensins as Markers of Gut Microbiota Disturbances in Children with Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotoudeheian, Mj. Value of Mac-2 Binding Protein Glycosylation Isomer (M2BPGi) in Assessing Liver Fibrosis in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Liver Disease: A Comprehensive Review of its Serum Biomarker Role. Current protein & peptide science 2025, 26, 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sotoudeheian, M.; Hoseini, S.; Mirahmadi, S.-M.; Farahmandian, N.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H. Oleuropein as a Therapeutic Agent for Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease During Hepatitis C. Rev. Bras. de Farm. 2023, 33, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian M, Hoseini S, Mirahmadi S. Therapeutic properties of polyphenols affect AMPK molecular pathway in hyperlipidemia. 2023.

- Babaeenezhad, E.; Farahmandian, N.; Sotoudeheian, M.; Dezfoulian, O.; Askari, E.; Taghipour, N.; Yarahmadi, S. Resveratrol Relieves Hepatic Steatosis and Enhances the Effects of Atorvastatin in a Mouse Model of NAFLD by Regulating the Renin-Angiotensin System, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarahmadi, S.; Sotoudeheian, M.; Farahmandian, N.; Mohammadi, Y.; Koushki, M.; Babaeenezhad, E.; Yousefi, Z.; Fallah, S. Effect of resveratrol on key signaling pathways including SIRT1/AMPK/Smad3/TGF-β and miRNA-141 related to NAFLD in an animal model. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 20, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam, M.; Ahmed, A.; Després, J.-P.; Jha, V.; Halford, J.C.G.; Chieh, J.T.W.; Harris, D.C.H.; Nangaku, M.; Colagiuri, S.; Targher, G.; et al. Incorporating fatty liver disease in multidisciplinary care and novel clinical trial designs for patients with metabolic diseases. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, F.; Vacca, A.; Bidault, G.; Sarver, D.; Kaminska, D.; Strocchi, S.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Greco, C.M.; Lusis, A.J.; Schiattarella, G.G. Decoding the Liver-Heart Axis in Cardiometabolic Diseases. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 1335–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, J.G.; Bradley, D.; McCall-Hosenfeld, J.; Motz-Patel, V.; Tondt, J.; Batra, S.; Fitzgerald, B.; Garcia, S.; Hummer, B.; Kindrew, C.; et al. Multidisciplinary clinic model enhances liver and metabolic health outcomes in adults with MASH. Hepatol. Commun. 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauridsen, M.M.; Ravnskjaer, K.; Gluud, L.L.; Sanyal, A.J. Disease classification, diagnostic challenges, and evolving clinical trial design in MASLD. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotoudeheian, M.; Mirahmadi, S.-M.; Azarbad, R. The association between glycemic state, R factor and Steatosis-Associated Fibrosis Estimator score in advanced liver fibrosis in patients with diabetes mellitus. Obes. Med. 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M. Unveiling the Link between Albumin-Bilirubin Grade and Liver Fibrosis in Patients with a History of Gallstone and Gallbladder Surgery: A Focus on Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. Korean J. Pancreas Biliary Tract 2025, 30, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtare, M.; Sharafeh, S.; Sotoudeheian, M.; Sadeghian, A.M.; Al-Busafi, S.A. The role of simple and specialized non-invasive tools in predicting of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease severity and prognosis. Obes. Med. 2025, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M. Potential Role of miR-455-3p in Liver Fibrosis Among Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Patients. 2024.

- Mokhtare, M.; Sadeghian, A.M.; Sotoudeheian, M. S1390 The Accuracy and Reliability of AST to Platelet Ratio Index, FIB-4, FIB-5, and NAFLD Fibrosis Scores in Detecting Advanced Fibrosis in Patients With Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, S1064–S1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtare, M.; Abdi, A.; Sadeghian, A.M.; Sotoudeheian, M.; Namazi, A.; Sikaroudi, M.K. Investigation about the correlation between the severity of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 58, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M. Agile 3+ and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: Detecting Advanced Fibrosis based on Reported Liver Stiffness Measurement in FibroScan and Laboratory Findings. Int. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Dis. 2024, 03, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, M.-H.; Liu, D.; Lin, Y.; Song, S.J.; Chu, E.S.-H.; Liu, D.; Singh, S.; Berman, M.; Lau, H.C.-H.; et al. A blood-based biomarker panel for non-invasive diagnosis of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Cell Metab. 2024, 37, 59–68.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaitiyiming, M.; Maihemuti, S.; Aierken, T.; Abulimiti, G.; Aibaidula, T.; Guan, Y.; Simayi, A.; Aimaiti, M.; Wang, X.; Abuduaini, A.; et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals gut microbial and metabolic signatures in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1666110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M. miRNA-29a: A Shared Regulator in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. 2024.

- Sotoudeheian, M.J.; Azarbad, R.; Mirahmadi, S.-M.; Farahmandian, N. The Role of Metformin in Modifying Ferroptosis to Treat Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: A Narrative Review. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 20, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyal AJ, Newsome PN, Kliers I, Østergaard LH, Long MT, Kjær MS, et al. Phase 3 trial of semaglutide in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. New England Journal of Medicine 2025, 392, 2089–2099. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomba, R.; Hartman, M.L.; Lawitz, E.J.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Boursier, J.; Bugianesi, E.; Yoneda, M.; Behling, C.; Cummings, O.W.; Tang, Y.; et al. Tirzepatide for Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatohepatitis with Liver Fibrosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suki, M.; Imam, A.; Amer, J.; Milgrom, Y.; Massarwa, M.; Hazou, W.; Tiram, Y.; Perzon, O.; Sharif, Y.; Sackran, J.; et al. SGLT2 Inhibitors in MASLD (Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease) Associated with Sustained Hepatic Benefits, Besides the Cardiometabolic. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkorakis, M.; Boutari, C.; Hill, M.A.; Kotsis, V.; Loomba, R.; Sanyal, A.J.; Mantzoros, C.S. Resmetirom, the first approved drug for the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis: Trials, opportunities, and challenges. Metabolism 2024, 154, 155835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keam, S.J. Resmetirom: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureddin, M.; Rinella, M.E.; Chalasani, N.P.; Neff, G.W.; Lucas, K.J.; Rodriguez, M.E.; Rudraraju, M.; Patil, R.; Behling, C.; Burch, M.; et al. Efruxifermin in Compensated Liver Cirrhosis Caused by MASH. New Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2413–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Sheridan, D.; McPherson, S.; Alazawi, W.; Abeysekera, K.; Marjot, T.; Brennan, P.; Mahgoub, S.; Cacciottolo, T.; Hydes, T.; et al. National study of NAFLD management identifies variation in delivery of care in the UK between 2019 to 2022. JHEP Rep. 2023, 5, 100897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutgers Obesity ECHO: Advancing MASLD and Obesity Management through Interdisciplinary Collaboration (Obesity-MASLD).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).