1. Introduction

Mutations in the human

USH2A gene account for most cases of Usher Syndrome type II (USH2), an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by progressive retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and associated hearing and balance impairment. The

USH2A gene is one of the largest in the human genome, spanning 72 exons. Despite the diversity of pathogenic missense and nonsense mutations, deletions, duplications, alternative splicing and pseudo-exon inclusion variants across these exons, several mutational hotspots have been identified, with exon-13 containing two of the most common mutations found in patients [

1].

According to the LOVD Database, the most frequent

USH2A pathogenic mutation reported in almost 25% of USH2 patients is the c.2299delG, p.Glu767Serfs*21 [

2,

3,

4], where a single base pair deletion disrupts the reading frame in the fifth laminin-type epidermal growth factor-like (EGF-Lam) domain, resulting in a premature stop codon and presumably the generation of a 786 aa truncated protein and/or nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD). This variant was reported in patients from America, Africa, China, and Europe [

5], reaching the highest frequency of 30.6% in Scandinavia [

6] due to a homozygous

USH2A European common ancestor [

7,

8]. The second most common variant is the missense mutation c.2276 G>T, p.Cys759Phe, with a frequency of 7.6%. Here, the replacement of a cysteine with a phenylalanine is thought to impair the function of usherin, the protein encoded by

USH2A, via the disruption of a disulphide bond or the affected interactions with the extracellular matrix [

9,

10].

While the exact role in the retina remains unclear, usherin is thought to be involved in the regulation of protein transport between the inner and outer segments of photoreceptors cells [

11]. After the first detection of usherin along the connecting cilium of murine photoreceptor cells [

12], more animal models have been used, confirming the spatial localization of usherin to the periciliary membrane complex of macaque [

13], zebrafish [

14] and Syrian hamster [

15] photoreceptors, where it interacts with other key proteins, both directly and indirectly.

Murine studies have shown that usherin interacts directly with adhesion G protein-coupled receptor V1 (ADGRV1, USH2C) and whirlin (WHRN, USH2D) proteins through its PDZ-binding domain, forming the USH2 complex. In fact, the knockout of whirlin long isoform in a murine model resulted in decreased usherin expression, and usherin and ADGRV1 mislocalization. Further proof of the interactions taking place in the USH2 complex, with whirlin acting as a scaffold protein, was provided by the adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV)-mediated rescue of

Whrn, which led to renewed expression of whirlin, usherin, and USH2 complex localization to the periciliary membrane complex [

16]. Additionally, other proteins like harmonin (USH1C) and SANS (USH1G) interact indirectly with usherin [

17,

18], potentially contributing to the pathophysiology of Usher syndrome.

These interactions are critical for maintaining the structure and function of photoreceptors [

19,

20,

21,

22], and disruptions to this network are believed to play a central role in the onset of retinal degeneration seen in USH2-related conditions [

16].

Despite significant advances in unraveling the genetics behind

USH2A-related retinal degeneration, clinical treatment options remain elusive, emphasizing the need for innovative models to study the underlying mechanisms of the disease and explore new potential therapeutic strategies. To this date, several challenges have limited the success of therapeutic approaches for

USH2A-related retinal diseases. First of all, the large size of the gene exceeds the capacity of AAV viral vectors, prohibiting the delivery of non-mutant

USH2A form B coding sequences. Alternative delivery techniques, such as dual/triple AAV systems, intein-mediated protein splicing, or lentiviral or adenoviral vectors, attempt to overcome this problem; although limitations regarding low efficiency and harmful immune responses result in safety concerns for clinical use [

23]. In fact, many viral and non-viral delivery platforms activate the innate and adaptive immune system, leading to retinal inflammation or damage in an extremely delicate and highly compartmentalized structure, like the eye.

While the CRISPR/Cas9 technology allows the correction of pathogenic mutations [

24], it has to face the poor editing efficiency in post-mitotic photoreceptor cells and the risk of off-target effects [

25]. On the other hand, translational read-through drugs hold the potential of partially restoring functional protein synthesis, bypassing the premature stop codons caused by nonsense mutations, but with a limited applicability on only 20% of

USH2A variants [

26]. Similarly, an alternative therapeutic option is represented by the use of antisense oligonucleotides, e.g., QR-421a, which focus on correcting splicing defects to obtain a shortened but functional usherin [

27]. While all these therapies are directly targeting

USH2A, tackling the photoreceptor degeneration is also possible, delaying this process with neuroprotective factors and histone deacetylase inhibitors. However, this strategy cannot entirely prevent, or restore, the loss of photoreceptor cells.

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) have emerged as a powerful tool for modeling human diseases

in vitro [

28]. In the absence of readily available patient-derived cell lines, CRISPR/Cas9 technology can be applied to generate hiPSCs carrying specific patient mutations

in vitro, enabling the investigation of the pathogenic mechanisms of retinal diseases, like USH2 Syndrome. Such models make it possible not only to study the disease progression, but also to develop potential gene-based therapies or drug treatments. Retinal organoids represent a rapidly advancing application of hiPSCs technology. These three-dimensional

in vitro structures recapitulate the layered architecture of the human retina, including rod and cone photoreceptors, and Müller glial cells, providing a more accurate representation of retinal development and disease mechanisms than traditional two-dimensional cell cultures. The differentiation of hiPSCs into retinal organoids allows the study of the impact of genetic mutations on retinal cell function in a more physiologically relevant context [

29,

30,

31].

In this study, we describe the phenotype of differentiation day (DD) 225 retinal organoids bearing CRISPR/Cas9-engineered

USH2A nonsense mutation in exon-13 compared with isogenic controls. Using immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) we observed loss of the usherin protein complex at the photoreceptor cilium, and disturbed homeostasis and activation of the innate immune system in the adjacent Müller glial cells. These models offer valuable insights into the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the

USH2A disease, and can be used to test CRISPR/Cas9 homology independent targeted integration therapeutic strategies [

32].

3. Discussion

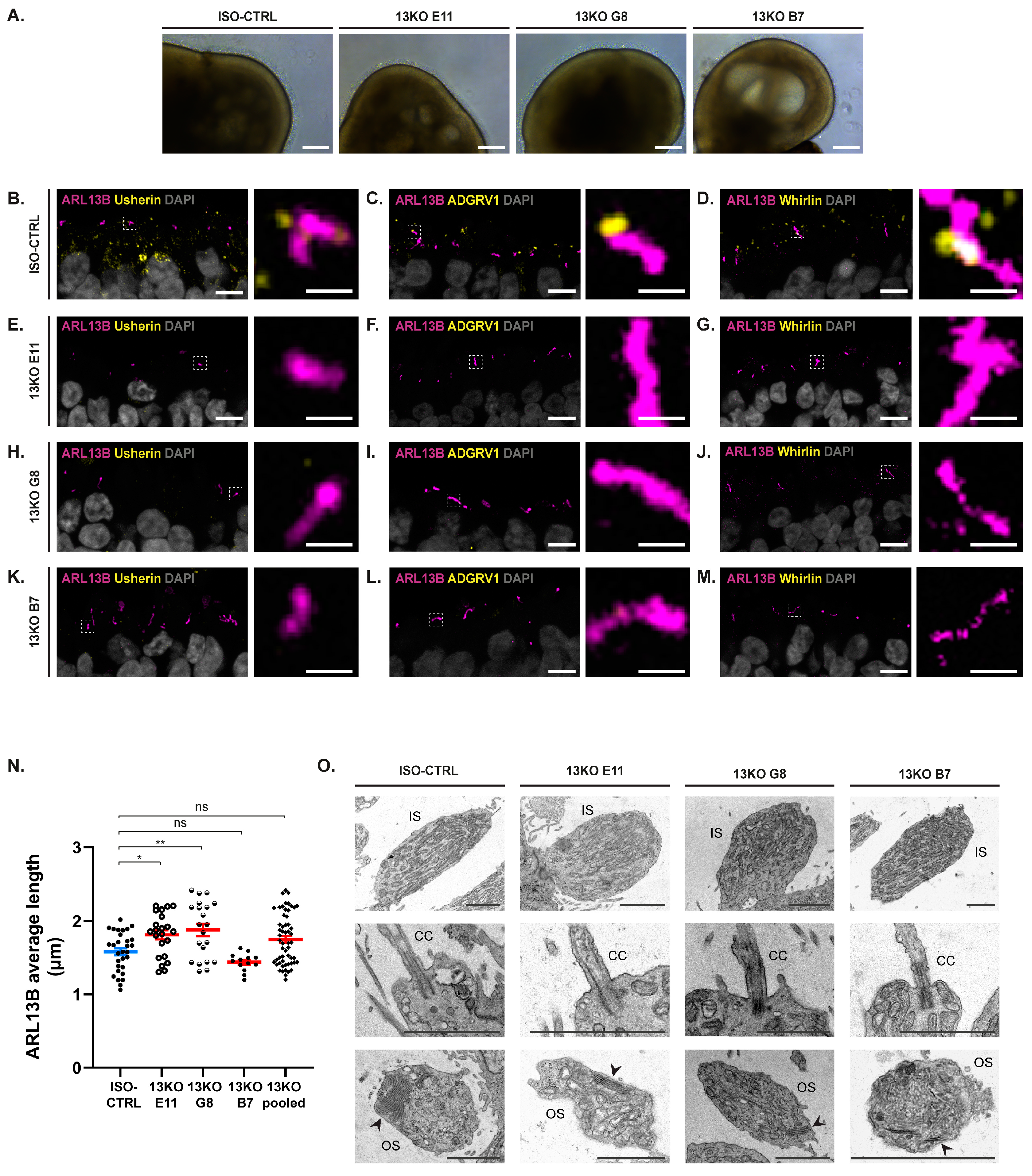

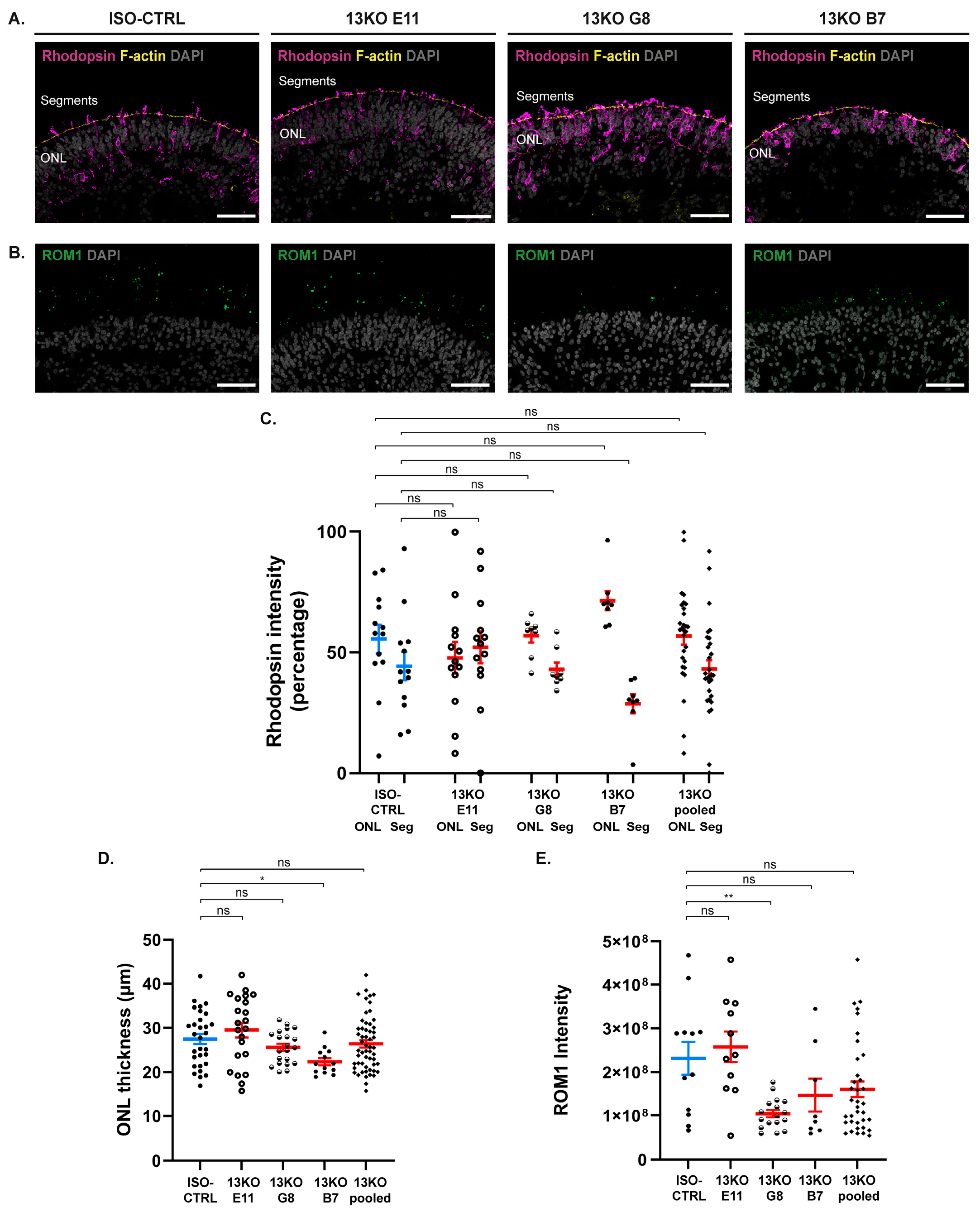

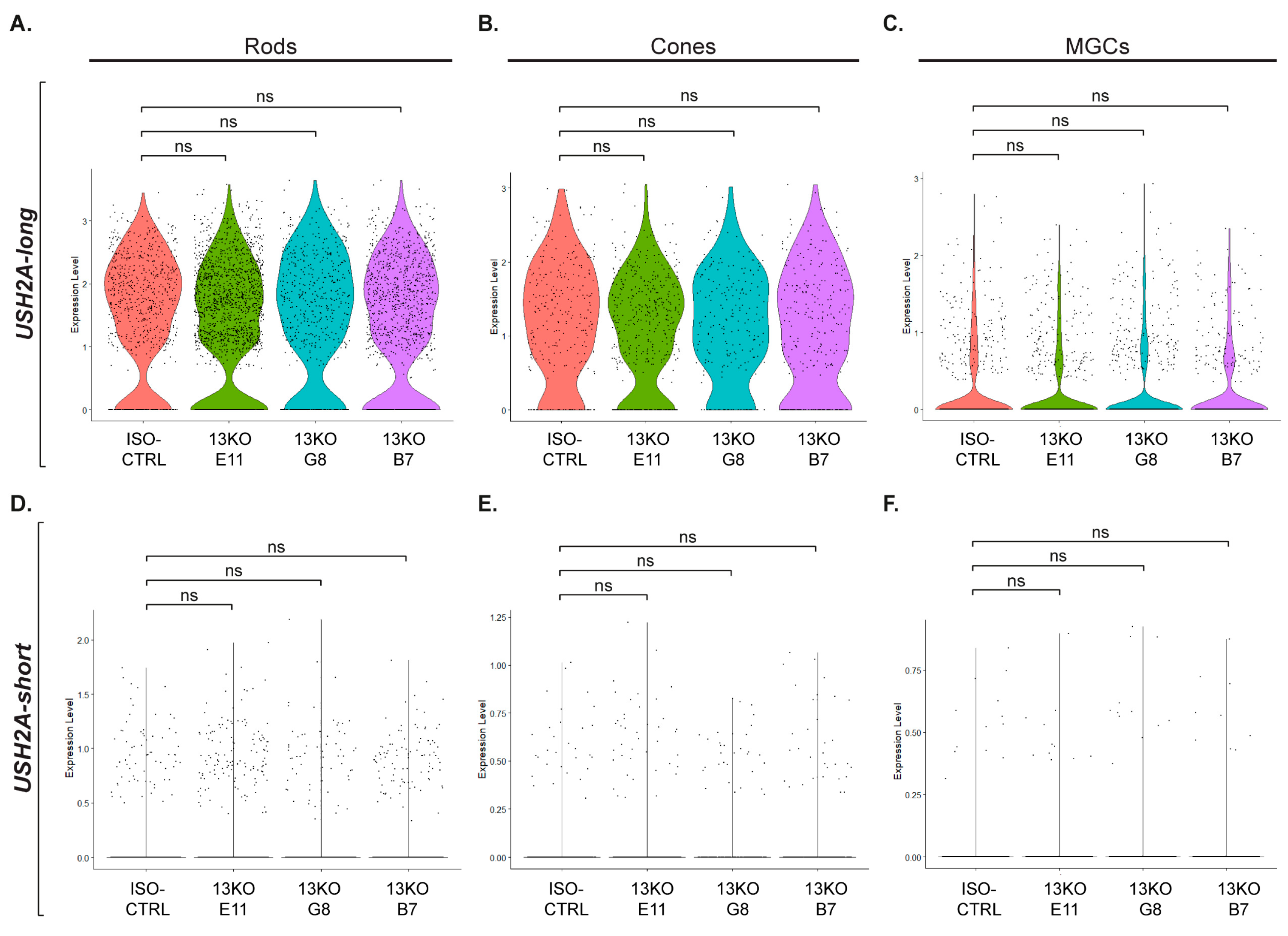

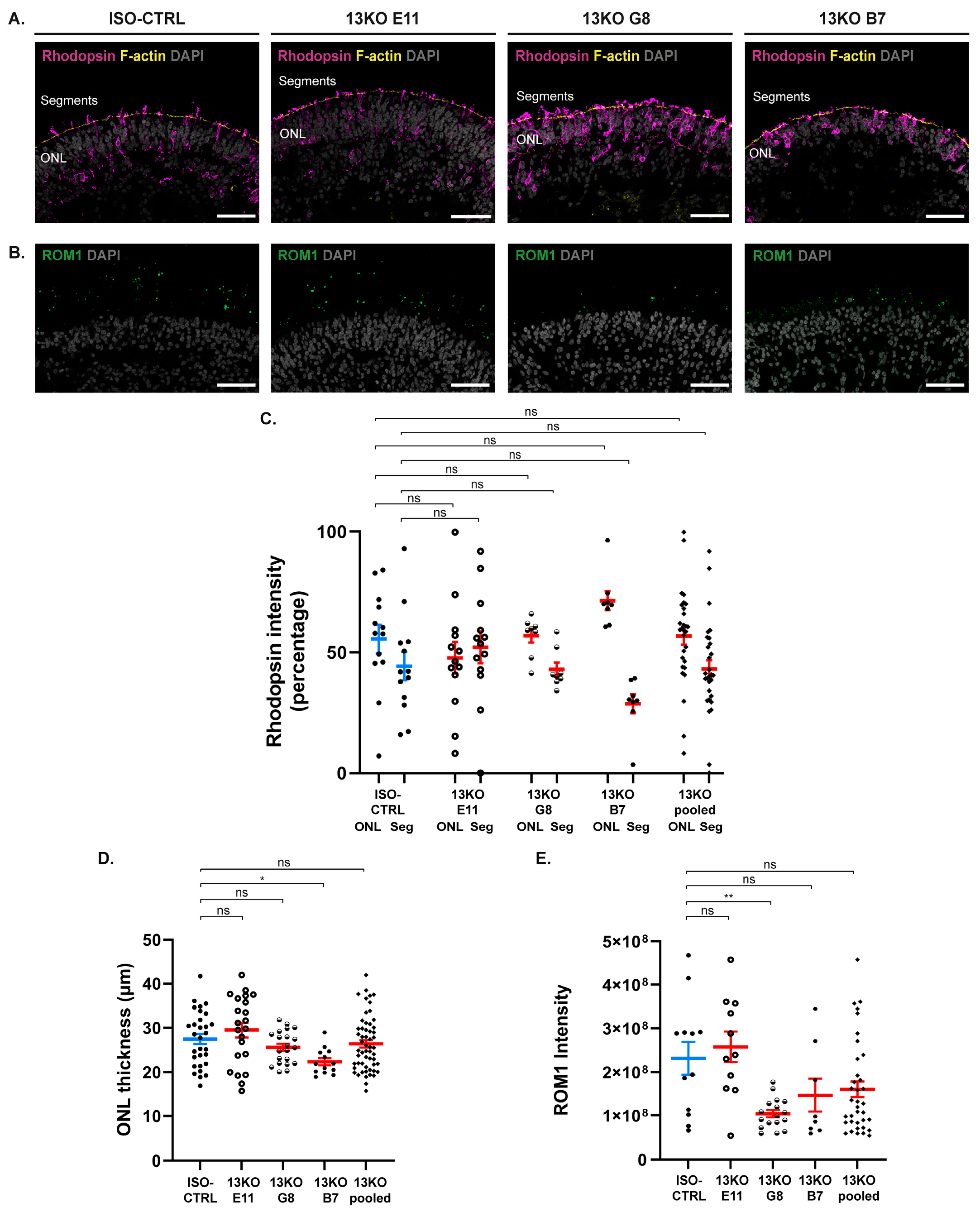

In this study, we successfully generated by CRISPR/SpCas9 technology three hiPSC subclones carrying a homozygous nonsense mutation in USH2A exon-13 and differentiated them into retinal organoids for 225 days. The overall morphology of USH2A 13KO photoreceptor structures appeared largely unaffected. The outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness and the distribution of rhodopsin, a key rod photoreceptor protein, between the ONL and the photoreceptor segments were preserved. Furthermore, only one 13KO subclone showed a significant difference in the intensity of the disk marker ROM1 when compared to the controls, although photoreceptor disks already showed varying stages of outer segment development in the TEM images.

Despite the average ciliary length being significantly increased in two 13KO subclones, this did not reach statistical significance in the comparison of the 13KO pool to the ISO-CTRL. Our data do not fully support the affected ciliogenesis detected in cells derived from non-syndromic RP and USH patients, where the fibroblasts carrying mutations in the

USH2A gene developed a 1.5 fold longer cilium than in the controls [

31]. However, the findings related to the ciliary length in our 13KO retinal organoids are in contrast with what previously investigated in mice, where the

Ush2adelG/delG variant caused the early onset shortening of the photoreceptor cilium [

37].

This study also observed that the long isoform B of usherin, along with its interacting proteins ADGRV1 and whirlin, were no longer detectable at the photoreceptor ciliary level in the

USH2A 13KO retinal organoids, compared to the isogenic controls. Yet, the presence of their transcripts in our scRNA-Seq data, as well as the detection of whirlin via Western Blot, suggest that these proteins can still be produced, but might be mislocalized in the photoreceptors or trapped in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or Golgi apparatus. This is consistent with what was previously observed in a knock-in mouse expressing the common human disease-mutation, c.2299delG. In that model, usherin was truncated and glycosylated, and accumulated in the ER, causing cellular stress and disrupting the localization of ADGRV1 and whirlin at the periciliary membrane complex, which were trapped in vesicles in the inner segments [

37].

The co-dependence of proteins within the USH2 complex had been already highlighted earlier in a knock-out murine model of

Whrn, where usherin expression was decreased and its localization in the ciliary pocket compromised [

16].

The impaired assembly and function of the usherin interactome in response to

USH2A mutations was further investigated in hiPSC-derived retinal organoids. Whilst usherin and ADGRV1 were correctly detectable at the base of the connecting cilium in the isogenic controls, both proteins were mislocalized to the inner segments of organoids carrying

USH2A variants responsible for either retinitis pigmentosa or USH2 [

31]. The nonsense mediated decay (NMD)-related reactome terms in the MGCs suggest that the NMD might be affected to an extent that is no longer sufficient to clear the

USH2A transcripts containing premature stop codons.

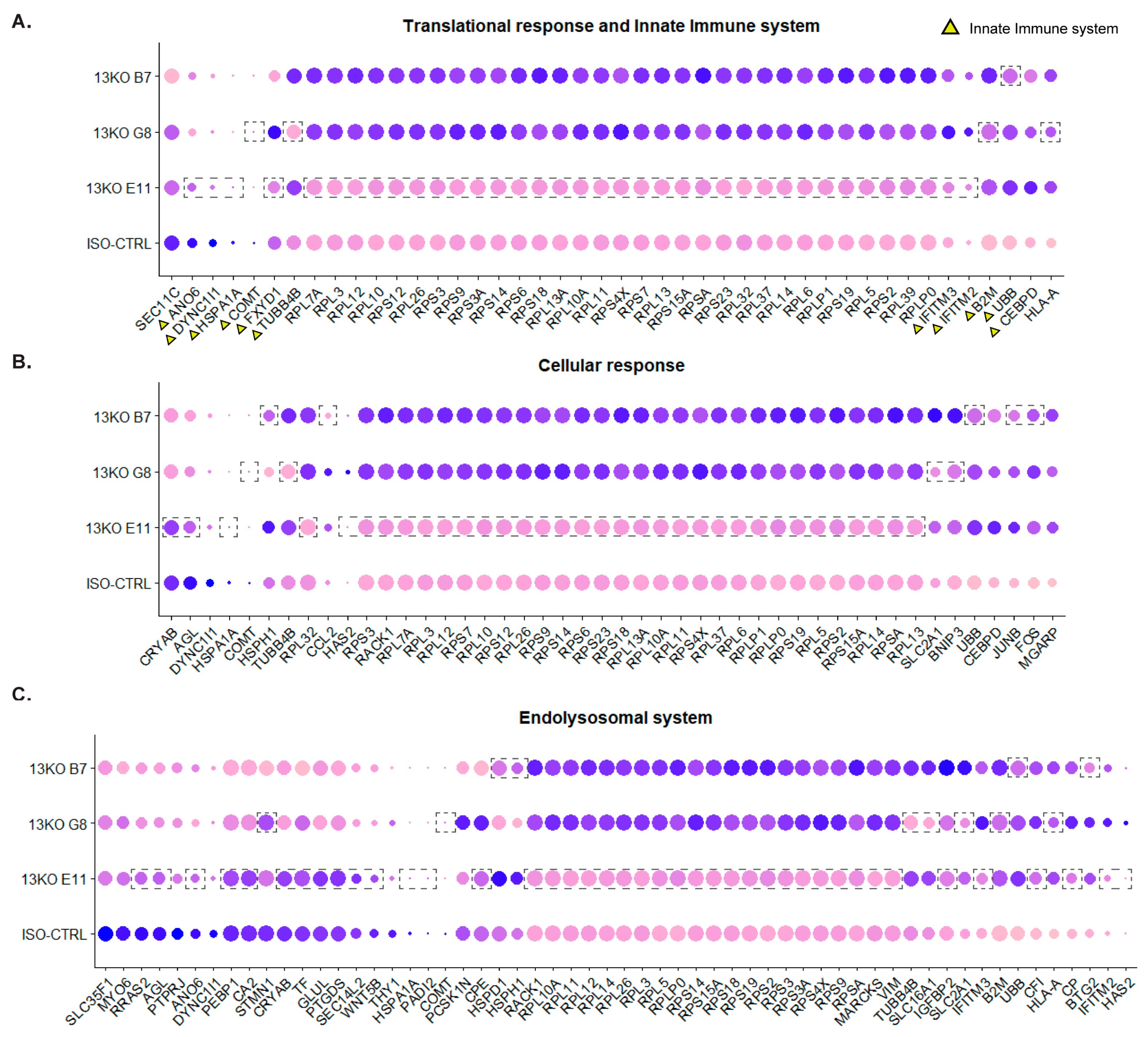

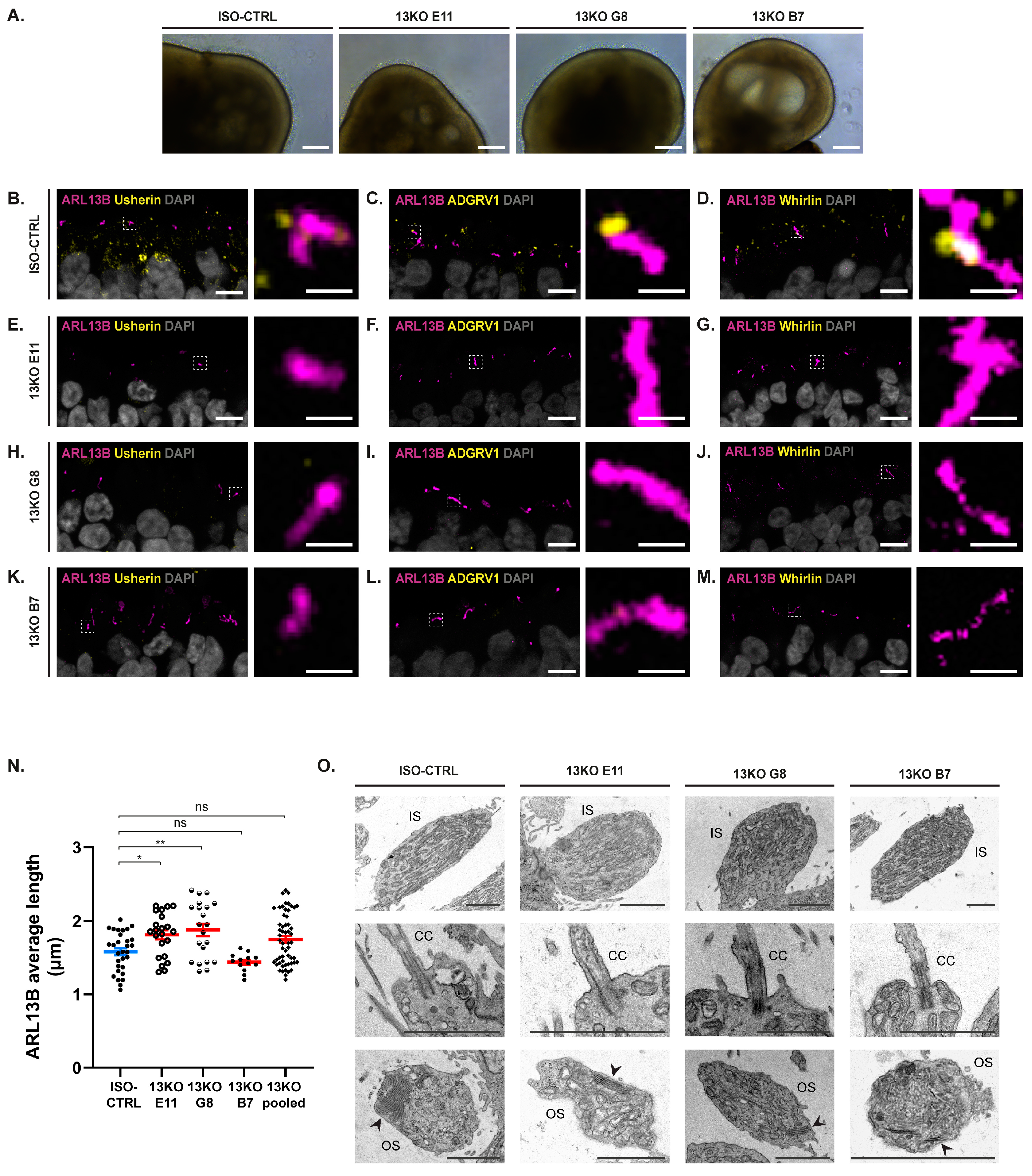

The anti-usherin antibody used in this analysis was raised against the C-terminal region of the protein, and therefore only able to detect the usherin long isoform B. We believe that a usherin mutant short form A (851 aa) or other protein might be secreted by the photoreceptor cells and endocytosed by the MGCs, triggering a cellular innate immune response, due to being recognized as a “foreign” or misfolded protein. This could explain the significant dysregulation of the endolysosomal system and the activation of the innate immune system in the MGCs of the USH2A 13KO organoids. This idea is further supported by the gene ontology terms indicative of protein misfolding, leading to the ubiquitination process. The entire cellular homeostasis in the MGCs of 13KO retinal organoids resulted compromised, spanning from translation to cellular response to stimuli.

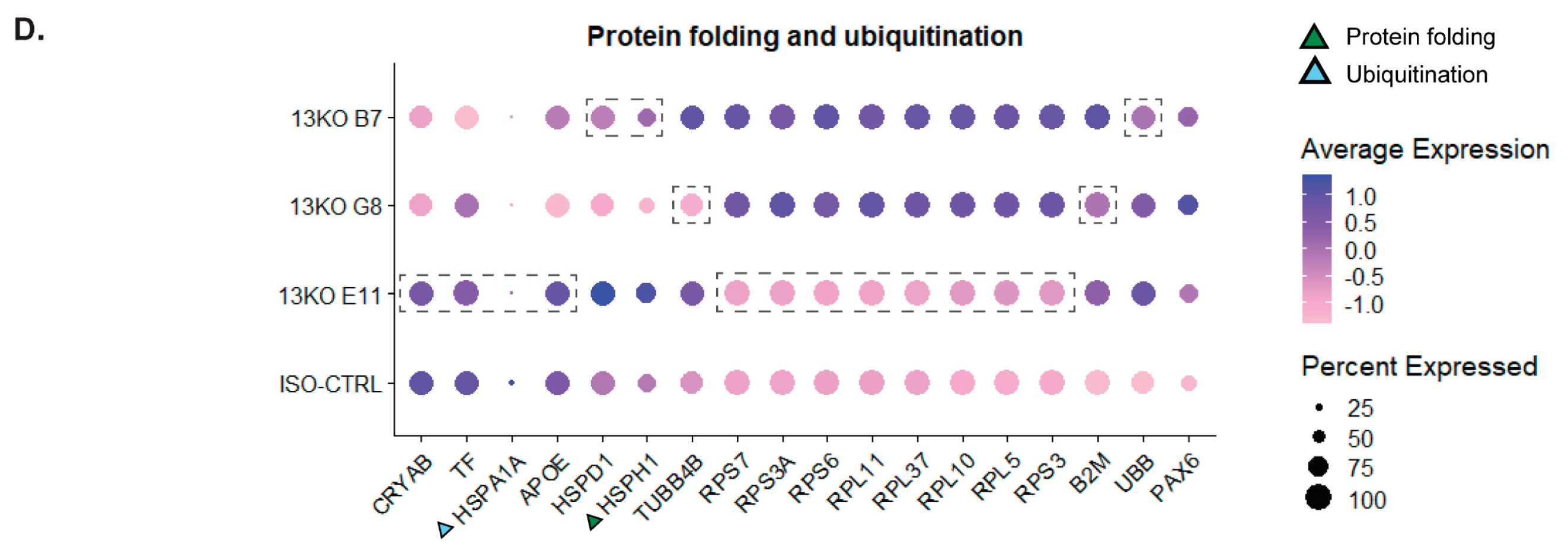

The detection of the

USH2A transcript encoding the short usherin isoform A primarily in rods, and to a lesser extent in cones, rather than in the Müller glial cells, suggests that the MGCs function as sensors of events occurring in the photoreceptor cells and respond by exhibiting signs of disrupted homeostasis. Differential expression of interferon-stimulated genes (

IFITM2 and

IFITM3) was observed, indicating an innate immune response, similarly observed upon viral infection. In fact, the release of type I and type II interferons induced by a pathogenic challenge upregulate

IFITM3 expression, which inhibits the entry of viruses into the host cells. Localizing to the endosomal compartment,

IFITM3 alters the rigidity and pH of cellular membranes, preventing the virus replication [

39,

43].

We infer that the usherin mutant short form A or other protein might be recognized as a pathogen, triggering the activation of those pathways normally taking place after infection by Influenza or SARS-CoV viruses.

Further studies need to investigate the molecular mechanisms behind the involvement of a cellular innate immune response in the USH2A 13KO retinal organoids.

Interestingly, the MGCs genotypic changes detected in our scRNA-Seq dataset were not reflected in a pronounced altered morphological phenotype. Despite the relevance of reactome terms indicating the activation of the MGCs response to stress, the intensity of GFAP, a marker of gliosis, was not statistically different in the 13KO subclones compared to the ISO-CTRL. Additionally, the apical villi of MGCs, as observed through CD44 staining and by TEM, were preserved in the mutant organoids, suggesting that there were no significant structural defects in the MGCs upon the KO of USH2A in exon-13.

This analysis provided a comprehensive overview of the molecular pathways most affected by the USH2A 13KO mutation. Although the photoreceptor cells showed some alterations in their expression profile, the most pronounced genetic changes occurred in the MGCs. Unexpectedly, these cells showed disruptions in several critical processes, including translation, immune response, and protein folding. The involvement of MGCs in the Usher 1C disease has been previously investigated [44,45,46], but the exact mechanisms of action remain unclear.

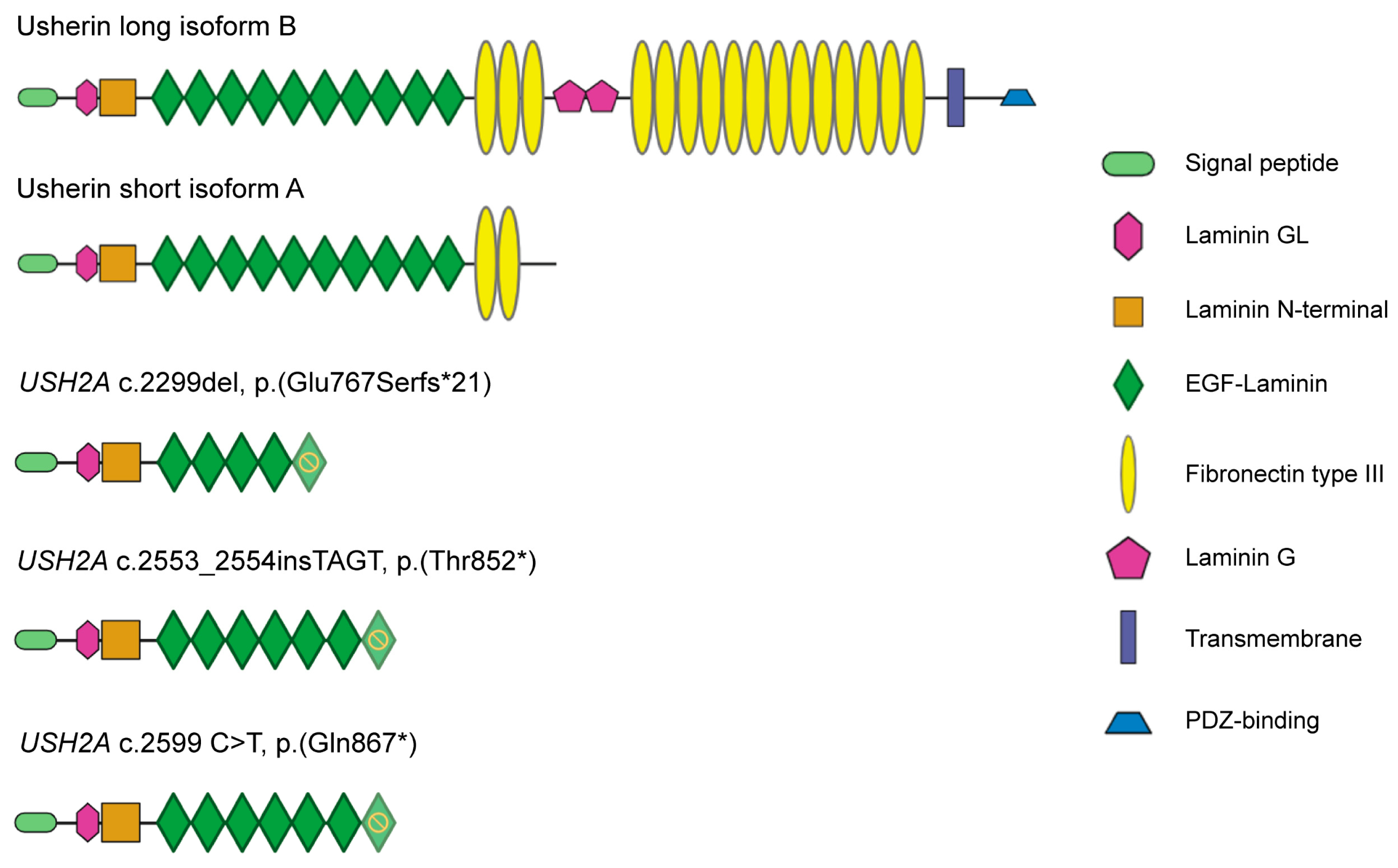

The short 851 aa usherin resulting from our KO design in

USH2A exon-13 mimics the truncated usherin produced in several patients with mutations in exon-13, such as c.2299delG and c.2599 C>T (

Table 1). Since those proteins share the same size range and functional domains, we can hypothesize that the phenotype observed in our 13KO retinal organoids faithfully recapitulate the phenotype of patients carrying other mutations in

USH2A exon-13, shedding light on a better comprehension of the pathogenic mechanisms behind Usher Syndrome type II.

In conclusion, this study suggests that, while the photoreceptor cells in the retinal organoids showed a loss of shuttling of usherin complex proteins to the cilium, the rod and cone photoreceptors were not severely affected at the gene expression level by the introduction of a nonsense mutation in exon-13 of the USH2A gene, whereas the Müller glial cells were strongly impacted, possibly playing a significant role in the pathogenesis of USH2A-related retinal diseases. Further investigation is needed to better unravel the mechanisms underlying the activation of the innate immune system and its implications for retinal disease progression and retinal gene therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.V. and J.W.; methodology, R.V., X.L., A.McD., A.M., R.M., and I.M.; software, R.V., I.M., R.M., S.K., and H.M.; validation, R.V., I.M., R.M., A.M.; formal analysis, R.V.; investigation, R.V., X.L., A.McD., A.M., R.K.; resources, J.Y.; data curation, R.V., R.M., and I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.V.; writing—review and editing, R.V. and J.W.; visualization, R.V.; supervision, J.W.; project administration, J.W.; funding acquisition, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Schematics of usherin domains in the natural occurring usherin isoforms compared to patient variants and USH2A 13KO. From top to bottom, depiction of the protein domains in the usherin long isoform B, the usherin short isoform A, and the usherin resulting from patient mutation c.2299del, c.2553_2554insTAGT (introduced in USH2A exon-13 by CRISPR/Cas9 in this study), and patient variant c.2599 C>T. Yellow stop sign indicates which EGF-Laminin domain is affected upon mutation.

Figure 1.

Schematics of usherin domains in the natural occurring usherin isoforms compared to patient variants and USH2A 13KO. From top to bottom, depiction of the protein domains in the usherin long isoform B, the usherin short isoform A, and the usherin resulting from patient mutation c.2299del, c.2553_2554insTAGT (introduced in USH2A exon-13 by CRISPR/Cas9 in this study), and patient variant c.2599 C>T. Yellow stop sign indicates which EGF-Laminin domain is affected upon mutation.

Figure 2.

USH2A 13KO mutation causes loss of photoreceptor ciliary localization of USH2 proteins in retinal organoids at DD225. (A) Representative brightfield images of ISO-CTRL, 13KO E11, 13KO G8, and 13KO B7 retinal organoids at DD225. Scale bars: 200 µm. (B-M) Representative immunohistochemical Z-stack images of ARL13B (purple) and usherin (B, E, H, K), ADGRV1 (C, F, I, L), and whirlin (D, G, J, M) (yellow) in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Scale bars: left, 6 µm; right, 2 µm. (N) Quantitative analysis of ARL13B average length in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 30, 13KO E11 n = 22, 13KO G8 n = 21, and 13KO B7 n = 13. Statistical analysis: p = 0.037, p = 0.004, p = 0.480, p = 0.067, from left to right. (O) Representative TEM images showing the presence of inner segment (IS)-like structures, basal body and connecting cilium (CC), and outer segment (OS)-like structures at the photoreceptor level in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Arrows point to the disk membranes. Scale bars: 2 µm. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 6, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, and 13KO B7 n = 3, from one differentiation.

Figure 2.

USH2A 13KO mutation causes loss of photoreceptor ciliary localization of USH2 proteins in retinal organoids at DD225. (A) Representative brightfield images of ISO-CTRL, 13KO E11, 13KO G8, and 13KO B7 retinal organoids at DD225. Scale bars: 200 µm. (B-M) Representative immunohistochemical Z-stack images of ARL13B (purple) and usherin (B, E, H, K), ADGRV1 (C, F, I, L), and whirlin (D, G, J, M) (yellow) in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Scale bars: left, 6 µm; right, 2 µm. (N) Quantitative analysis of ARL13B average length in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 30, 13KO E11 n = 22, 13KO G8 n = 21, and 13KO B7 n = 13. Statistical analysis: p = 0.037, p = 0.004, p = 0.480, p = 0.067, from left to right. (O) Representative TEM images showing the presence of inner segment (IS)-like structures, basal body and connecting cilium (CC), and outer segment (OS)-like structures at the photoreceptor level in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Arrows point to the disk membranes. Scale bars: 2 µm. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 6, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, and 13KO B7 n = 3, from one differentiation.

Figure 3.

Phenotypic analysis of the photoreceptor layer in retinal organoids upon USH2A loss at DD225. (A) Representative immunohistochemical images of Rhodopsin (purple) and F-actin (yellow) in ISO-CTRL, 13KO E11, 13KO G8, and 13KO B7 retinal organoids at DD225. (B) Representative immunohistochemical images of ROM1 (green) in ISO-CTRL, 13KO E11, 13KO G8, and 13KO B7 retinal organoids at DD225. (A, B) Scale bars: 50 µm. (C) Quantitative analysis of rhodopsin intensity distribution between the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and the photoreceptor segments (Seg) in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 13, 13KO E11 n = 13, 13KO G8 n =8, and 13KO B7 n = 8. Statistical analysis: p = 0.688, p = 0.999, p = 0.212, p = 0.999, from left to right. (D) Quantitative analysis of the ONL thickness in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 30, 13KO E11 n = 22, 13KO G8 n = 21, and 13KO B7 n = 13. Statistical analysis: p = 0.584, p = 0.650, p = 0.037, p = 0.838, from left to right. (E) Quantitative analysis of ROM1 intensity in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 12, 13KO E11 n = 11, 13KO G8 n = 17, and 13KO B7 n = 8. Statistical analysis: p = 0.920, p = 0.0005, p = 0.207, p = 0.120, from left to right.

Figure 3.

Phenotypic analysis of the photoreceptor layer in retinal organoids upon USH2A loss at DD225. (A) Representative immunohistochemical images of Rhodopsin (purple) and F-actin (yellow) in ISO-CTRL, 13KO E11, 13KO G8, and 13KO B7 retinal organoids at DD225. (B) Representative immunohistochemical images of ROM1 (green) in ISO-CTRL, 13KO E11, 13KO G8, and 13KO B7 retinal organoids at DD225. (A, B) Scale bars: 50 µm. (C) Quantitative analysis of rhodopsin intensity distribution between the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and the photoreceptor segments (Seg) in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 13, 13KO E11 n = 13, 13KO G8 n =8, and 13KO B7 n = 8. Statistical analysis: p = 0.688, p = 0.999, p = 0.212, p = 0.999, from left to right. (D) Quantitative analysis of the ONL thickness in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 30, 13KO E11 n = 22, 13KO G8 n = 21, and 13KO B7 n = 13. Statistical analysis: p = 0.584, p = 0.650, p = 0.037, p = 0.838, from left to right. (E) Quantitative analysis of ROM1 intensity in ISO-CTRL and 13KO retinal organoids. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 12, 13KO E11 n = 11, 13KO G8 n = 17, and 13KO B7 n = 8. Statistical analysis: p = 0.920, p = 0.0005, p = 0.207, p = 0.120, from left to right.

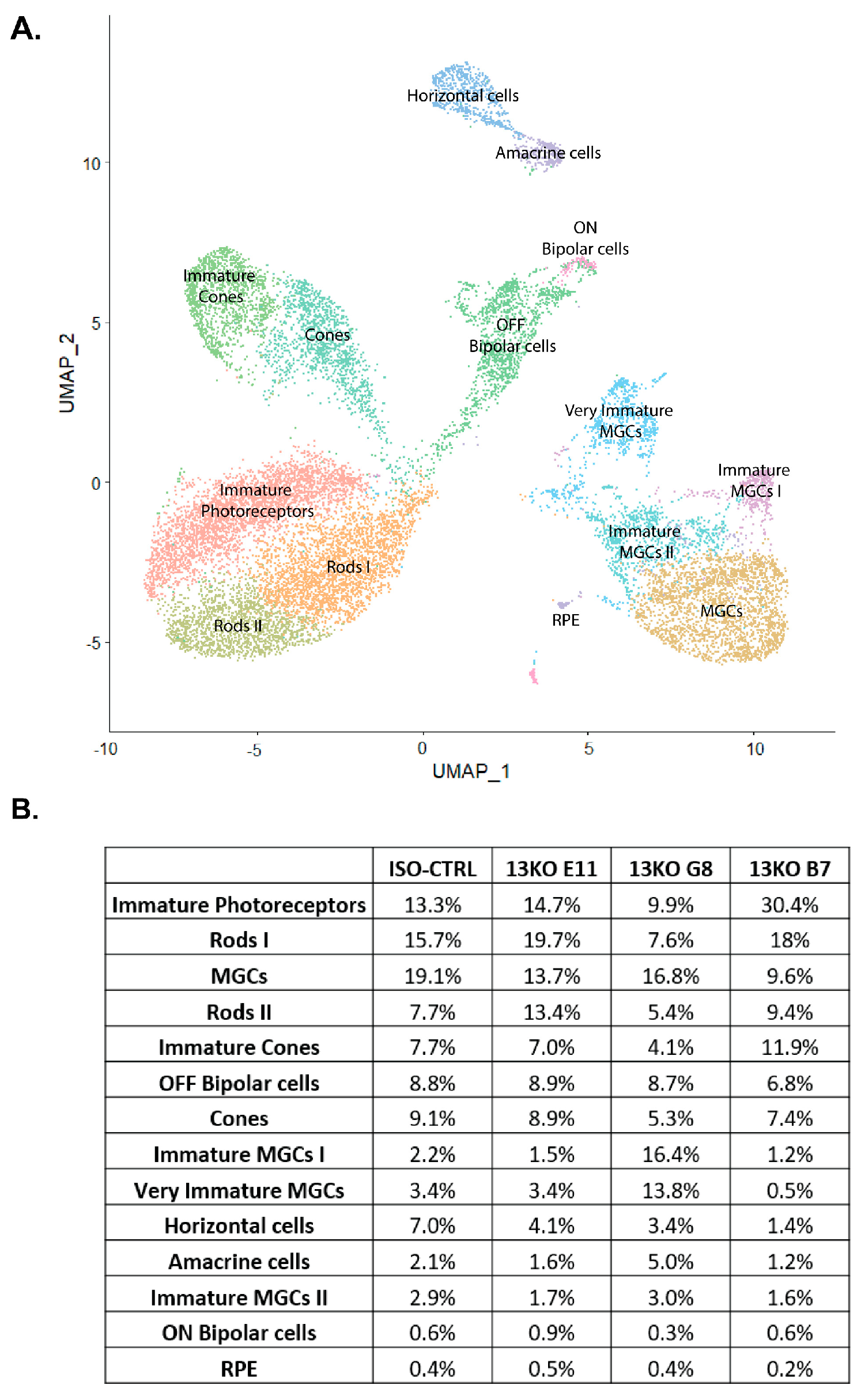

Figure 4.

scRNA-Seq analysis confirms the presence of all major retinal cell types in hiPSC-derived USH2A 13KO and isogenic control retinal organoids. (A) UMAP displaying 14 identified distinct cell clusters. (B) Table showing the percentage of each cell type across conditions. (C) Heatmap of top markers assigning cell cluster identities.

Figure 4.

scRNA-Seq analysis confirms the presence of all major retinal cell types in hiPSC-derived USH2A 13KO and isogenic control retinal organoids. (A) UMAP displaying 14 identified distinct cell clusters. (B) Table showing the percentage of each cell type across conditions. (C) Heatmap of top markers assigning cell cluster identities.

Figure 5.

Expression of USH2A, ADGRV1, and WHRN genes in photoreceptor and Müller glial cells. (A, E, I) UMAP plots showing expression of USH2A (A), ADGRV1 (E), and WHRN (I) across cell clusters in retinal organoids. (B, C, D) Violin plots comparing USH2A expression levels in the 13KO subclones to ISO-CTRL in Rods (A), Cones (C), and MGCs (D) (adjusted p-values = 1). (F, G, H) Violin plots comparing ADGRV1 expression levels in the 13KO subclones to ISO-CTRL in Rods (F), Cones (G), and MGCs (H) (adjusted p-values = 1). (J, K, L) Violin plots comparing WHRN expression levels in the 13KO subclones to ISO-CTRL in Rods (J), Cones (K), and MGCs (L) (adjusted p-values = 1). Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, and 13KO B7 n = 3, from the same differentiation round.

Figure 5.

Expression of USH2A, ADGRV1, and WHRN genes in photoreceptor and Müller glial cells. (A, E, I) UMAP plots showing expression of USH2A (A), ADGRV1 (E), and WHRN (I) across cell clusters in retinal organoids. (B, C, D) Violin plots comparing USH2A expression levels in the 13KO subclones to ISO-CTRL in Rods (A), Cones (C), and MGCs (D) (adjusted p-values = 1). (F, G, H) Violin plots comparing ADGRV1 expression levels in the 13KO subclones to ISO-CTRL in Rods (F), Cones (G), and MGCs (H) (adjusted p-values = 1). (J, K, L) Violin plots comparing WHRN expression levels in the 13KO subclones to ISO-CTRL in Rods (J), Cones (K), and MGCs (L) (adjusted p-values = 1). Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, and 13KO B7 n = 3, from the same differentiation round.

Figure 6.

scRNA-Seq analysis of DD225 USH2A 13KO retinal organoids shows disruptions in the endolysosomal system and cellular response in rod photoreceptors compared to isogenic controls. (A) Pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in rods, with similar terms grouped into categories. (B) Statistically significant DEGs in at least two USH2A 13KO subclones in rods. Dashed boxes highlight genes that did not exhibit differential expression in a specific subclone compared to ISO-CTRL. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, 13KO B7 n = 3 from the same differentiation round.

Figure 6.

scRNA-Seq analysis of DD225 USH2A 13KO retinal organoids shows disruptions in the endolysosomal system and cellular response in rod photoreceptors compared to isogenic controls. (A) Pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in rods, with similar terms grouped into categories. (B) Statistically significant DEGs in at least two USH2A 13KO subclones in rods. Dashed boxes highlight genes that did not exhibit differential expression in a specific subclone compared to ISO-CTRL. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, 13KO B7 n = 3 from the same differentiation round.

Figure 7.

Figure 7. scRNA-Seq analysis of DD225 USH2A 13KO retinal organoids shows major disruptions in the homeostasis of Müller glial cells compared to isogenic controls. (A) Pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in MGCs, with similar terms grouped into categories. (B) Dot plot of the statistically significant DEGs found in the MGCs of all three USH2A 13KO subclones. Triangles indicate the genes involved in pathways related to the innate immune system. (C) UMAPs of the detected common 13 DEGs. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, 13KO B7 n = 3 from the same differentiation round.

Figure 7.

Figure 7. scRNA-Seq analysis of DD225 USH2A 13KO retinal organoids shows major disruptions in the homeostasis of Müller glial cells compared to isogenic controls. (A) Pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in MGCs, with similar terms grouped into categories. (B) Dot plot of the statistically significant DEGs found in the MGCs of all three USH2A 13KO subclones. Triangles indicate the genes involved in pathways related to the innate immune system. (C) UMAPs of the detected common 13 DEGs. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, 13KO B7 n = 3 from the same differentiation round.

Figure 8.

Differential expression analysis of Müller glial cells compared to isogenic controls. (A, B, C, D) Statistically significant DEGs in at least two USH2A 13KO subclones involved in Translational response and Innate immune system (A), Cellular response (B), Endolysosomal system (C), and Protein folding and ubiquitination (D). Dashed boxes highlight genes that did not exhibit differential expression in a specific subclone compared to ISO-CTRL. Triangles indicate those genes that are exclusively involved in a single pathway within the macro-category. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, 13KO B7 n = 3 from the same differentiation round.

Figure 8.

Differential expression analysis of Müller glial cells compared to isogenic controls. (A, B, C, D) Statistically significant DEGs in at least two USH2A 13KO subclones involved in Translational response and Innate immune system (A), Cellular response (B), Endolysosomal system (C), and Protein folding and ubiquitination (D). Dashed boxes highlight genes that did not exhibit differential expression in a specific subclone compared to ISO-CTRL. Triangles indicate those genes that are exclusively involved in a single pathway within the macro-category. Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, 13KO B7 n = 3 from the same differentiation round.

Figure 9.

Analysis of USH2A transcripts coding for the long and short usherin isoforms in photoreceptors and Müller glial cells of USH2A 13KO retinal organoids compared to isogenic controls. (A-F) Violin plots comparing the expression levels of USH2A coding for usherin long isoform B (A-C) and usherin short isoform A (D-F) in the 13Ksubclones to ISO-CTRL in Rods (A, D), Cones (B, E), and MGCs (C, F) (adjusted p-values = 1). Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, 13KO B7 n = 3 from the same differentiation round.

Figure 9.

Analysis of USH2A transcripts coding for the long and short usherin isoforms in photoreceptors and Müller glial cells of USH2A 13KO retinal organoids compared to isogenic controls. (A-F) Violin plots comparing the expression levels of USH2A coding for usherin long isoform B (A-C) and usherin short isoform A (D-F) in the 13Ksubclones to ISO-CTRL in Rods (A, D), Cones (B, E), and MGCs (C, F) (adjusted p-values = 1). Number of organoids used: ISO-CTRL n = 4, 13KO E11 n = 4, 13KO G8 n = 3, 13KO B7 n = 3 from the same differentiation round.

Table 1.

List of patient and 13KO USH2A mutations resulting in a similar truncated usherin protein structure.

Table 1.

List of patient and 13KO USH2A mutations resulting in a similar truncated usherin protein structure.

|

USH2A mutation |

Usherin change |

Usherin size (aa) |

Protein domain affected |

| c.2311 G>T |

p.(Glu771Ter) |

770 |

EGF-Lam like 5 |

| c.2299del |

p.(Glu767Serfs*21) |

786 (766+20) |

EGF-Lam like 5 |

| c.2310del |

p.(Glu771Lysfs*17) |

786 (770+16) |

EGF-Lam like 5 |

| c.2314delG |

p.(Ala772Profs*16) |

786(771+15) |

EGF-Lam like 5 |

| c.2344del |

p.Glu782Lysfs*6) |

786 (781+5) |

EGF-Lam like 5 |

| c.2391_2392del |

p.(Cys797*) |

796 |

EGF-Lam like 6 |

| c.2431 A>T |

p.(Lys811*) |

810 |

EGF-Lam like 6 |

| c.2431_2432_del |

p.(Lys811Aspfs*11) |

820 (810+10) |

EGF-Lam like 6 |

| c.2440 C>T |

p.(Gln814*) |

813 |

EGF-Lam like 6 |

| c.2512 C>T |

p.(Glu838*) |

837 |

EGF-Lam like 6 |

| c.2541 C>A |

p.(Cys847*) |

846 |

EGF-Lam like 7 |

| c.2553_2554insTAGT |

p.(Thr852*) |

851 |

EGF-Lam like 7 |

| c.2599 C>T |

p.(Gln867*) |

866 |

EGF-Lam like 7 |

| c.2610 C>A |

p.(Cys870*) |

869 |

EGF-Lam like 7 |

| C.2661 C>A |

p.(Tyr887) |

886 |

EGF-Lam like 7 |