1. Introduction

For more than three decades, temperature sensing is being, probably, the most well-known application of fiber Bragg gratings (FBG) [

1]. Independently of the physical parameter under measurement, temperature discrimination is required [2-7]. In this context, a precise determination of temperature is an essential task and, therefore, an accurate knowledge of the FBG temperature sensitivity is on demand [

8]. In comparison to the number of publications related to FBG theory, applications and simulations, only few acknowledge the fact that the Bragg wavelength shifts nonlinearly with temperature, even for a limited temperature range, such as 120 °C, and that the thermo-optic coefficient of silica-doped glass fibers depends on temperature and wavelength [8-11]. Recently [

11], preliminary results pointed toward the independence on wavelength of the “temperature gauge factor” K

T=(1/

λ)(d

λ/dT) [

12] or the normalized temperature sensitivity, in the 1500–1600 nm range. However, we recognize that definite conclusions require higher stability, accuracy and resolution of the equipment used. Therefore, in this paper we compare the normalized temperature sensitivity of fs-FBG and UV-FBG, we discuss the potential effect of the hydrogen-loading process and of the initial grating coupling strength on K

T values. We demonstrate that K

T is, essentially, independent on wavelength in the 1500–1600 nm wavelength range. Based on the previous results, we also demonstrate that the temperature dependence of the Bragg wavelength of a second FBG can be predicted through integration of the K

T expression obtained previously for a former FBG. A thorough discussion on the experimental errors that can affect the determination of the FBG temperature sensitivity is also presented. The K

T expressions for FBG inscribed in silica fibers with distinct concentrations of GeO

2 are also given.

3. Gratings Thermal Characterization

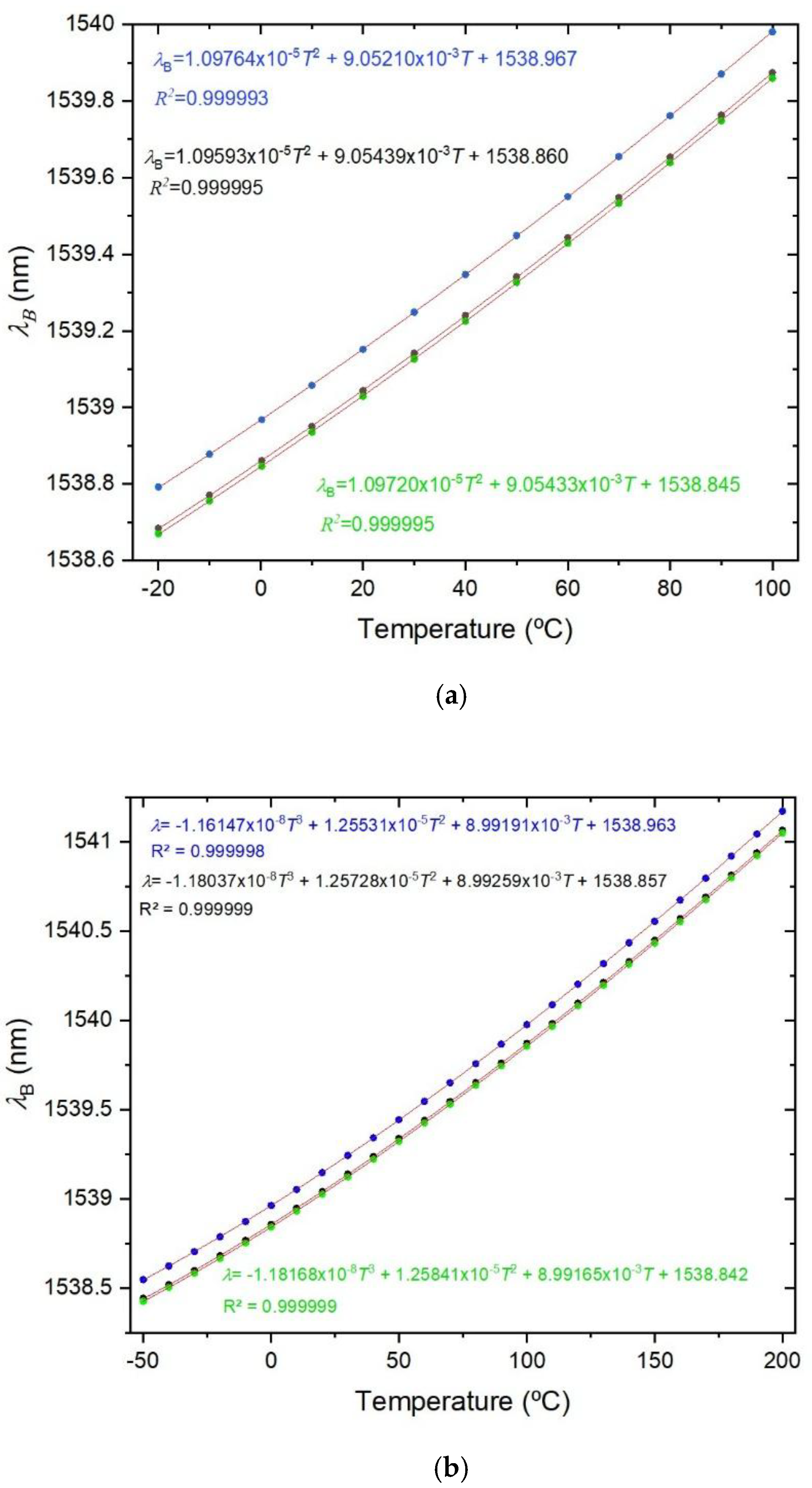

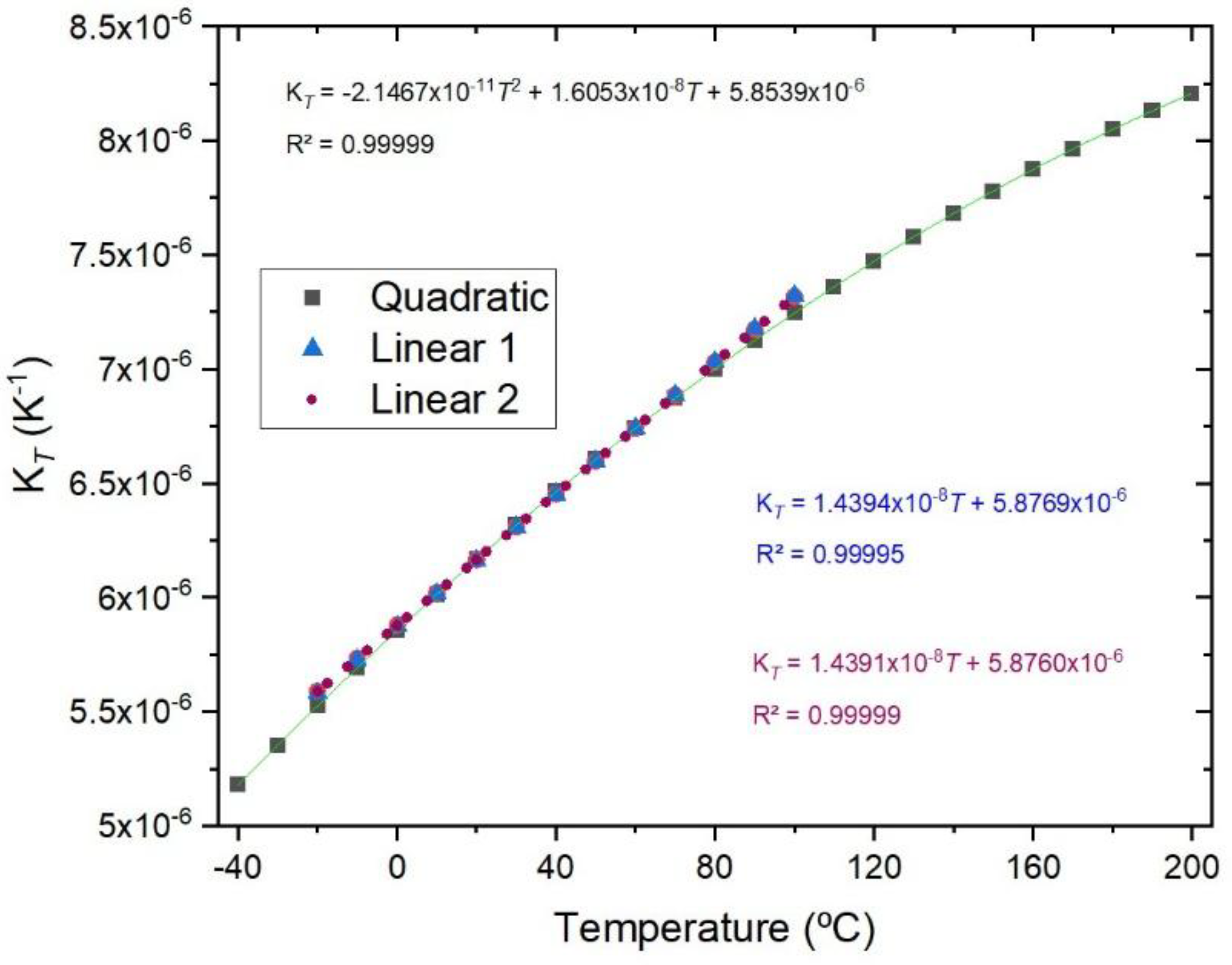

The temperature characterization was performed using a Dry block-temperature calibrator from Sika, model type TP17200S, allowing measurements between −55 °C and 200 °C with 0.01 °C resolution and an accuracy of 0.2 °C. Gratings were mounted inside the insert blocks keeping them stress-free. Bragg wavelengths were measured, after ~1h stabilization, using an optical interrogator FS22SI BraggMeter ST (with 8 channels), with an acquisition rate of 1 sample/s, which enables resolution/stability better than 0.5 pm/1 pm. The temperature range was from −20 °C up to 100 °C (cycle: 30 °C up to 90 °C, followed by 100 °C down to −20°C, and finally −10 up to 30°C, all in steps of 20°C). At each temperature step, the Bragg wavelength was determined by averaging 2500 data points and the standard deviation was lower than 0.7 pm, with a typical value of 0.4 pm. A quadratic fitting was applied to the temperature dependence of the Bragg wavelength and it was observed that K

T shifted linearly with temperature. Similarly, gratings inscribed in the SMF-28 fiber were submitted to four heating cycles from −50 °C up to 200 °C. A cubic fitting was applied to the temperature dependence of the Bragg wavelength and K

T shifted quadratically with temperature.

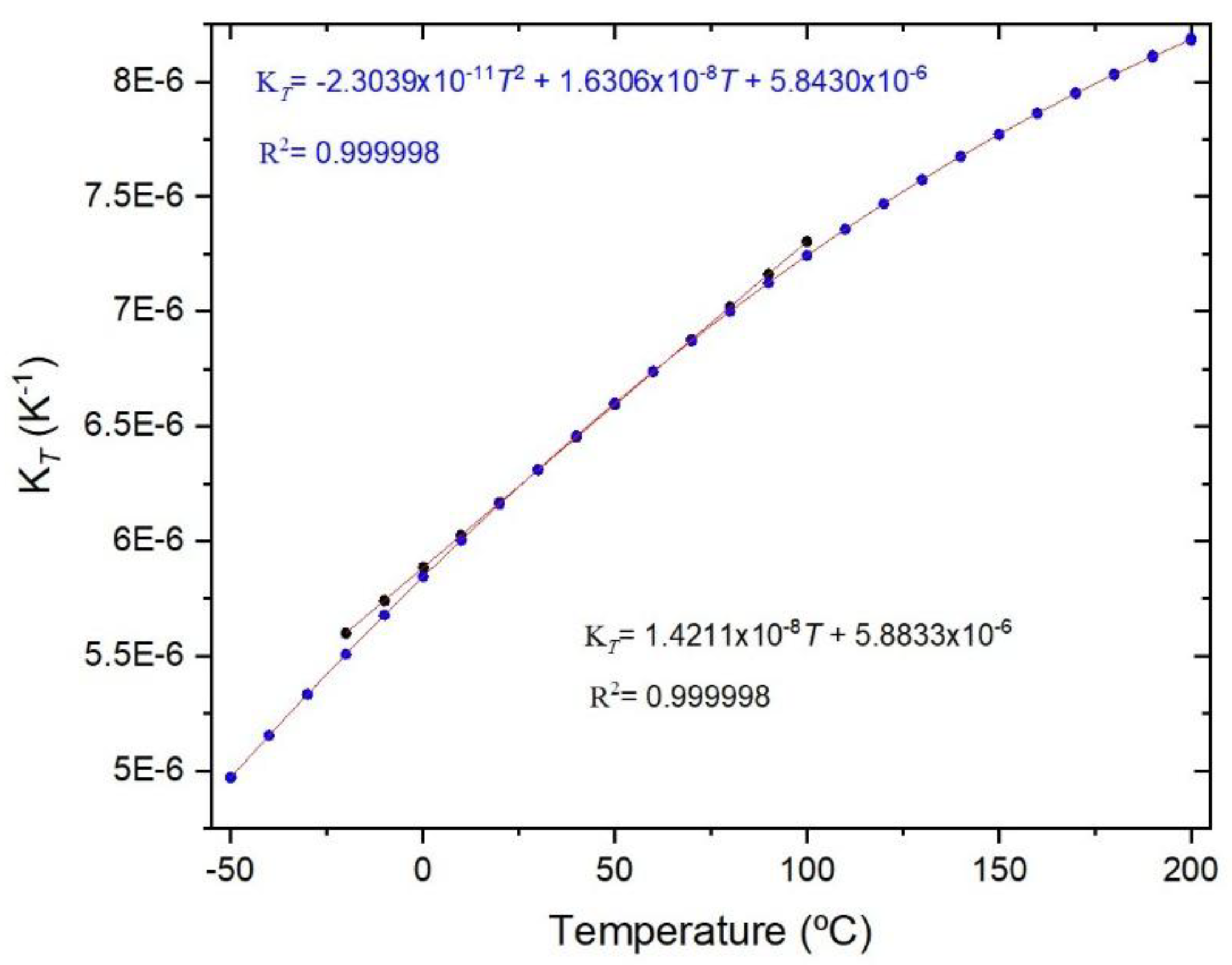

Figure 2 shows the temperature dependence of the Bragg wavelength for both temperature cycles. The comparison between the fitting of K

T is presented in

Figure 3, where it can be observed that a divergence occurs as one approaches the limits of the temperature interval [−20, 100] °C. This divergence can be explained by the fact that, at room temperature, K

T=((1/

neff)(d

neff/dT) +

SiO2) (the normalized hermos-optic coefficient and the thermal expansion coefficient, respectively) is essentially determined by the temperature behavior of the hermos-optic coefficient (d

neff/dT), a cubic temperature dependence [

8,

9,

13,

14]. The calibrations were repeated with all fiber gratings in

Table 1 and results are summarized in

Table 2. It can be observed that K

T increases with the fiber GeO

2 content, being lower for the B/Ge fiber. The absolute values of K

T for the SMF-28 fiber and Leoni SMF with an Ormocer coating differs from the ones previously measured [

11]. Therefore, we performed a reanalysis of those experiments and results will be discussed in the next section. The possible effect of the hydrogen-loading process or the grating coupling strength (reflectivity) on K

T values was studied using gratings in the SMF-28e+ fiber. The results have shown that up to a reflectivity of 15% there is no impact on the determination of the normalized temperature sensitivity. Similar results were obtained for the other fibers, namely, a grating induced in the PS1500 (NA=0.29) fiber with a reflectivity as high as 33% was tested and gratings inscribed in a batch of the Leoni SMF with an Ormocer coating, having reflectivity ranging from 1% up to a saturated level, were also used.

4. Error Analysis Related to FBG Thermal Characterization

This section besides the scientific content, also intends to be a pedagogical one in an era of unprecedent exponential increase of “insufficient mature” published data. The initial thermal characterizations were performed using a customized oven as described in [

15] (although with shorter dimensions) and the thermal bath described in [

11]. However, both heating apparatuses exhibited errors in the absolute temperature measurements. We realized that a 5 pm difference (or equivalently a temperature difference of 0.5 °C) on each temperature step led, after fitting the temperature dependence of the Bragg wavelength, to values of K

T at room temperature (20 °C) that were expected for 29.4 °C, being clearly not sufficient for the precision required [

8]. Therefore, all further characterizations were performed using the calibrated Dry block described in the previous section and using this new setup (Dry block + interrogator), we have investigated the potential source of errors in the determination of the temperature dependence of the Bragg wavelength, for which hundreds (above 750) of independent temperature measurements were performed over the last 18 months.

The potential effect of using different optical interrogators (comparison with a FS22SI with 4 channels) was analyzed. We have tested 3 FBG (

λB~1543 nm) inscribed in the SM1500 (NA_0.19) and other 3 FBG (

λB~1541 nm) induced in the Leoni SMF fiber (with an Ormocer coating). Three heating cycles were performed in the temperature interval: − 20-100 °C, using the 8 channels unit and 4 more for the 4 channels unit in a total of 34 tests. All K

T values at 20 °C were in the interval ±0.004 K

-1, therefore, both interrogators register the same values of Bragg wavelengths and, consequently, leading to the same K

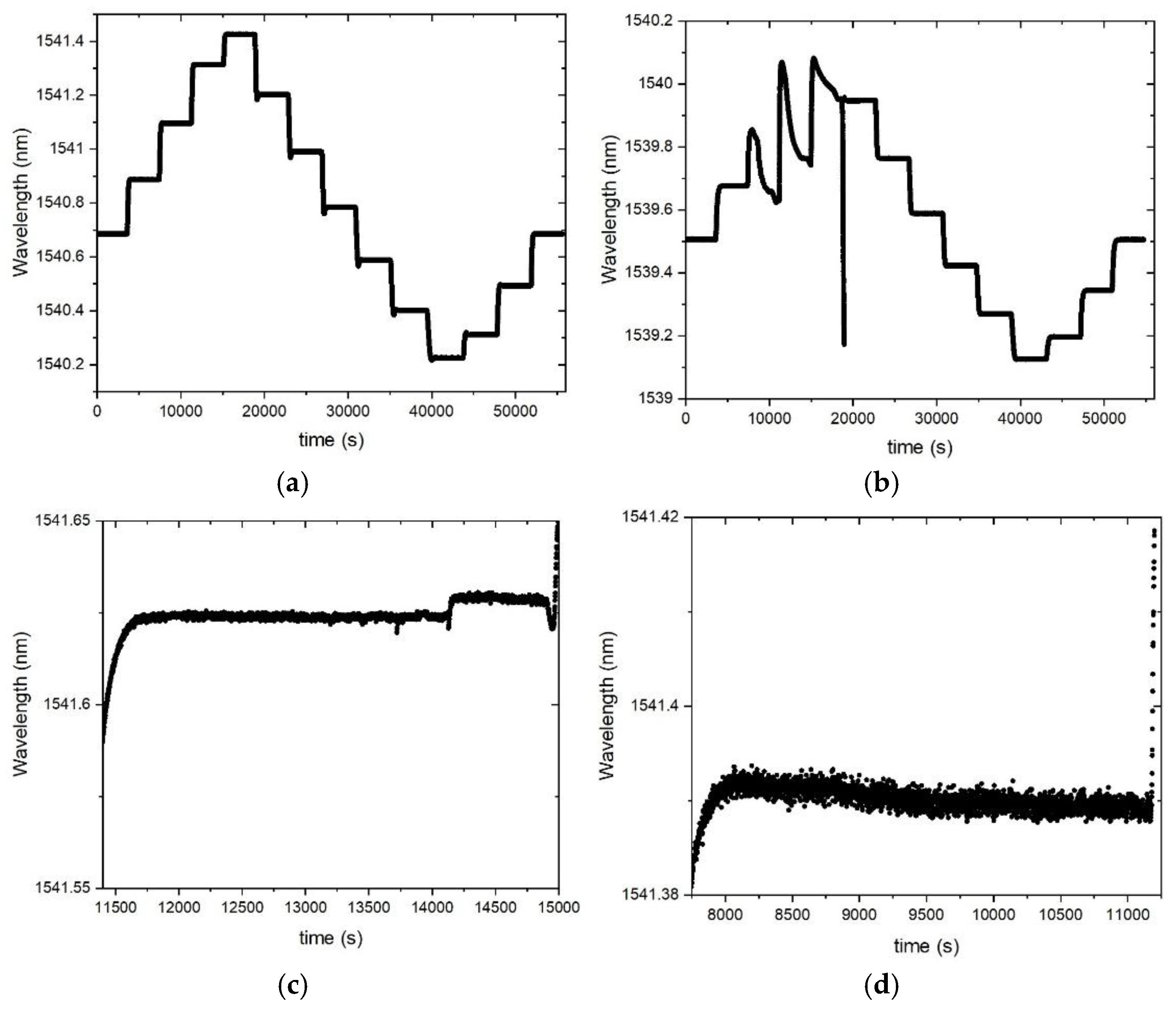

T values. We have identified another source of error related to a temperature gradient inside the calibration inserts (15.0 cm long) containing the FBG, which was estimated to be ~0.3 °C/cm outside the homogeneous temperature region. For that we have inserted gratings at different depths (5 to 15 cm) and we have also used an array with five 4.5 mm-gratings separated by ~10 mm. The Sika manual states that the homogeneous temperature zone is limited to 4.0 cm, therefore, the FBG should be well inside that region at the bottom of the insert. Since the temperature stability is very important to obtain good measurements, for each temperature step we analyzed the standard deviation, that typically was better than 0.4 pm, and we calculated the average of the resonance wavelength, typically using 2500 data points. When we close the cycle returning to the initial temperature we also checked the resonance wavelength, the difference should be lower than 1 pm. Sometimes the device loses stability, probably associated to condensation, which is observed in

Figure 4 (b)-(d) (wavelength vs time) and that also impacts the values obtained for K

T. It should be stressed that we have tried to minimize the occurrence of condensation inside the Dry block by increasing the temperature above 100 °C in the first step before decreasing to 30 °C, but the improvement is not always clear and neither uniform for all channels. The frequency of instability events seems to be associated to changes in temperature and humidity in the lab room along the year. As an example, it was difficult to reach stable values of temperature at −50 °C during summer and, therefore, we limited measurements down to −40 °C.

When the above sources of error are controlled, we still have to deal with the curve fitting. A thorough study on the measurements repeatability was performed by using three gratings inscribed in the SMF-28 fiber. Four heating cycles (−20-100 °C) followed by another four heating cycles (−50-200 °C) were performed. Recently (6 months interval), five heating cycles (−40-200 °C) were also performed to compare reproducibility (measurements were limited to −40 °C, as mentioned above). For the former a 2

nd order polynomial fitting was applied to the temperature dependence of the Bragg wavelength while a wider temperature range demands for a higher polynomial fitting (

Figure 2). As can be observed in

Figure 3 and

Figure 5, the normalized temperature sensitivity value is slightly lower for the latter. Nevertheless, a similar value is obtained when restricted to the same temperature range. It should be mentioned that K

T values at 20 °C do not differ by more than 0.01 in each temperature range, totalizing 39 independent measurements. We have also analyzed the influence of decreasing the temperature step, by performing three tests between −40 °C and 100 °C such that when merged with previous tests results in temperature steps of about 2.5 °C. The K

T values are similar to the ones obtained in previous tests (Linear 2 in

Figure 5). In general, gratings in other fibers show similar behavior.

The last source of error, and one of the most important, is the homogeneity of the fiber itself, that is, the uniform distribution of the germanium concentration along the fiber core. As mentioned previously, we found values for fs-FBG ranging from 6.175 x 10

-6 K

-1 up to 6.224 x 10

-6 K

-1., and from 6.153 x 10

-6 K

-1 up to 6.213 x 10

-6 K

-1 for UV-FBG. The lack of uniformity was pointed out in the past during the fabrication of mechanically-induced gratings in the SMF-28 fiber [

16] and arc-induced gratings in the B/Ge co-doped fiber [

17]. In this work, we have used the Leoni SMF fiber as a reference since we had commercially available fs-FBG on it and therefore, we could make comparisons between FBG produced under different fabrication techniques and parameters, such as, reflectivity. Initially we attributed the differences to the fs inscription, but after comparison of UV-FBG produced in the SMF-28 fiber and in the Leoni SMF fiber using different setups ([

11] and current work) we notice that while the ones inscribed in the SMF-28 fiber show similar values of K

T, the same did not happen for FBG induced in the Leoni SMF fiber. Moreover, recently we have inscribed FBG in two new commercially available batches of SM1500 fiber (both NA=0.19 and NA=0.29) and not only the Bragg wavelength is much higher (Δn

core = 1.555 x 10

-3 and 4.390 x 10

-3, which corresponds to an estimated increase in GeO

2 concentration of 1.1 and 3.0 mol%, respectively [

8]) but also K

T is higher for FBG induced in both fibers: from 6.238 x 10

-6 K

-1 to 6.290 x 10

-6 K

-1 and from 6.574 x 10

-6 K

-1 to 6.724 x 10

-6 K

-1, respectively. Therefore, we have used 18 m of the Leoni SMF fiber containing two fs-FBG (~19%; (6.182±0.001) x 10

-6 K

-1) to inscribe UV-FBG with different reflectivity (<1%, 18.9%, 98.8% and saturated) using both setups and all values of K

T fallen in the range: (6.186±0.006) x 10

-6 K

-1. It should be highlighted that peak detection for the high reflectivity gratings is also a demanding task (and the values of R

2 of the fitting are lower for these gratings). Therefore, since we cannot guarantee that there is uniform distribution of germanium in the core of the 18 m of the Leoni SMF fiber, under the experimental conditions, we may conclude that K

T is similar for fs-FBG and UV-FBG and that the coupling strength has negligible influence on the determination of K

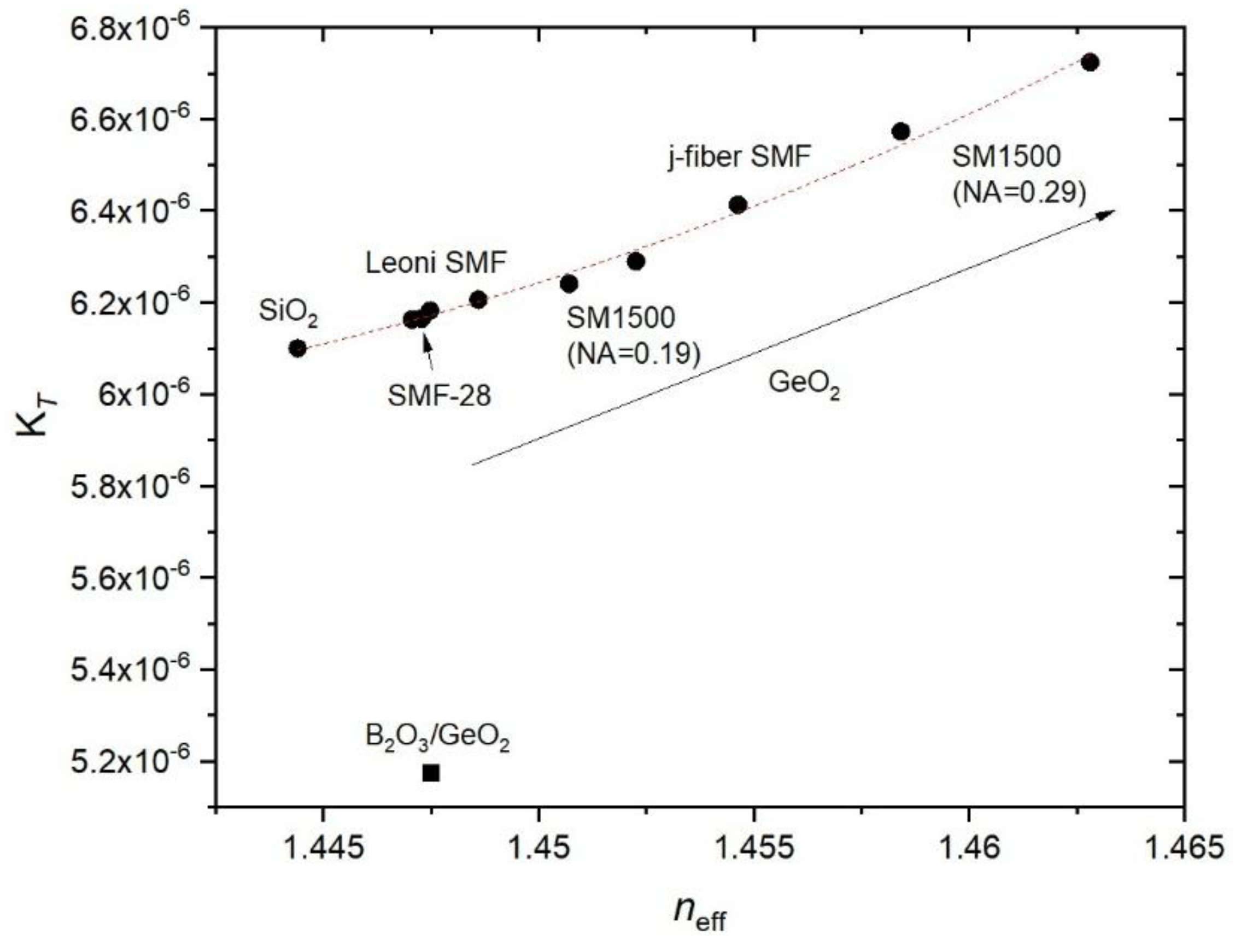

T. For the sake of illustration, and since we do not know the fiber parameters in order to determine germanium concentration, we present K

T as a function of

neff in

Figure 6. We have also included the K

T value (K

T=1.4178x10

-8 T+ 6.1299x10

-6 K

-1; 6.413x10

-6 K

-1 @20 °C) obtained using three gratings (

λB~1540, 1547 and 1554 nm) inscribed in another high Ge-doped fiber (j-fiber SMF: NA=0.26 and MFD=5.5±0.4). It is clearly shown that K

T increases with the increase of GeO

2 concentration and decreases with B

2O

3 concentration.

5. Prediction of the Temperature Dependence of the Bragg Wavelength

Assuming that we know K(

T) for one UV-FBG and

λ(

T0) for a second FBG inscribed in the same fiber, we can determine

λ(

T) for the latter, through integration of K(

T) and by applying a 3

rd order Taylor expansion to the exponential function. Thus,

and

where K

i (i=0, 1, 2) are coefficients. For the [−20, 100] temperature range, a linear behavior is adequate and therefore, K

2=0. We demonstrate the applicability by using five gratings written in the SM1500 (NA_0.19) fiber with a reflectivity of about 0.5%.

Table 3 summarizes the average values of K

T at 20 °C for four tests in the [−40, 200] temperature range, limited to the [−20, 100] °C and also three tests in the [−20, 97.5] °C, in steps of 10 °C but at different temperature plateaus. For each grating, the absolute error of K

T is within 0.002 K

-1. Therefore, there is a slight dependence of K

T on wavelength (in a range that exceeds 50 nm) that was averaged in the subsequent calculations. Thus, by fitting all experimental data, for the former temperature range we obtained K

T = −2.1973x10

-11T2 + 1.6689x10

-8T + 5.9194x10

-6 (R

2 = 0.99998), for the second K

T = 1.5004x10

-8T + 5.9410x10

-6 (R

2 = 0.99986) and for the latter K

T = 1.5118x10

-8T + 5.9358x10

-6 (R

2 = 0.99985).

Table 4 summarizes the results obtained by comparison of the Bragg wavelengths and temperature sensitivity (d

λ/d

T) values from direct calibration (d

λ_dir2/d

T and d

λ_dir3/d

T, for quadratic and cubic fitting, respectively) and by following Eq (1)-(4) where we have assumed K

T through the fitting of all experimental data of the five FBG (

λ_int2 and d

λ_dint2/d

T, for quadratic fitting and

λ_int3 and d

λ_dint3/d

T, for cubic fitting). In each temperature range, the difference in wavelength is lower than 3 pm and the calculated temperature sensitivity differs by ~0.01 pm/°C. It should be noted that the differences in the temperature sensitivity near the limits of the temperature range (0.1 pm/°C) is essentially due to the dependence of K

T on temperature (goes from quadratic to cubic dependence for larger temperature interval), despite its also slight dependence on wavelength for the five FBG inscribed in this fiber with high GeO

2 dopant concentration (as observed in

Table 3 and with impact on the fitting: R

2 = 0.99986). Concerning the [−20, 97.5] °C temperature range, the values of K

T at 20 °C have lower dispersion (

Table 3) and similar results were obtained when applying the method to estimate the wavelength and temperature sensitivity of the “unknown” grating.

A similar analysis was performed using five gratings inscribed in the SMF-28 fiber and K

T was calculated in the − 20–100 °C temperature range.

Table 5 summarizes the average values of d

λ/d

T and K

T for four independent measurements. Note that the dependence of the temperature sensitivity on wavelength is well expressed in Eq. (4). All results are within 6.165 ± 0.004 K

-1, being more stable than the ones obtained for the previous gratings inscribed in the SM1500 fiber.

Table 6 shows the results of considering the methodology by using K

T = 1.4236 x 10

-8T + 5.8831 x 10

-6 (R

2 = 0.9999999) for the FBG at 1509.2 nm and by applying it to the FBG at 1561.6 nm. The largest difference, 2.4 pm, occurs at −20 °C but the sensitivity is always within 0.01 pm/°C. Similar results would be obtained if we have used for K

T, the average of all measurements (K

T = 1.4310 x 10

-8T + 5.8786 x 10

-6; R

2 = 0.99994). It should be stressed that we analyzed the independence on wavelength using gratings inscribed in other fibers and results were even more constant, within 0.001, although for shorter wavelength ranges: SM1500_NA=0.29 (2 FBG; 10 nm), j-fiber SMF (3 FBG; 14 nm), Leoni SMF (5 gratings; 27 nm).

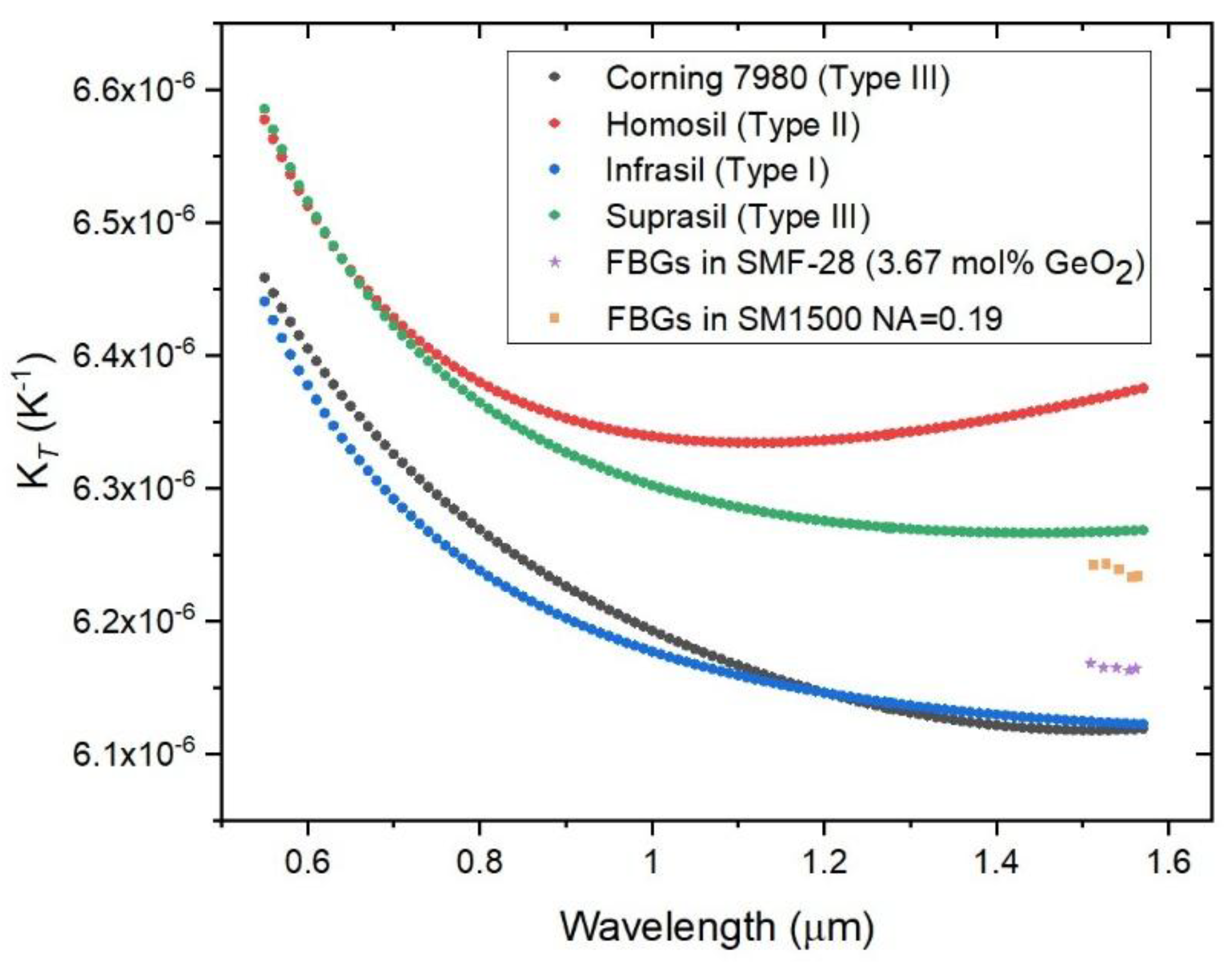

Figure 7 shows the wavelength dependence of ‘K

T‘ for four silica glasses and K

T for five FBG inscribed in the SMF-28 Corning fiber and in the SM1500 fiber (NA=0.19). As can be observed, the wavelength dependence of K

T is negligible for the FBG in the SMF-28 fiber (and also resembles the ‘K

T‘ behavior of the Corning glass). On the other hand, K

T seems to have a slight dependence on wavelength for FBG in the SM1500 fiber.