1. Introduction

Several areas of machine learning and applied topology have sought to represent structured data by exploiting geometric, combinatorial or topological properties. Three major traditions provide the necessary context. Topological data analysis extracts global shape information through persistent homology and related vectorizations, but treats data as a single undifferentiated space and therefore cannot distinguish objects that share identical homology yet differ in how local feature distributions vary over the underlying geometry (Laubenbacher and Hastings 2019; Bukkuri, Andor, and Darcy 2021; Chazal and Michel 2021; Xu, Drougard, and Roy 2021; Skaf and Laubenbacher 2022; El-Yaagoubi, Chung, and Ombao 2023; Smith et al. 2024). Geometric and manifold-based approaches capture local relationships through graph, spectral or diffusion operators but do not explicitly represent how feature spaces change along cycles or how local patches are glued together (Paulsen, Gramstad, and Collas 2015; Tsamir-Rimon and Borenstein 2023; Hu et al. 2024; Sekmen and Bilgin 2024; Song et al. 2024; Gao et al. 2025). Gauge-inspired constructions introduce parallel transport and equivariant operations, yet typically enforce symmetry constraints without computing homological invariants, characteristic-class-like quantities or measures of connection inconsistency (Maîtrejean 2008; Sauer 2022; Maîtrejean 2024; Nagai, Ohno, and Tomiya 2025). Each of these traditions captures a meaningful aspect of structure (global topology, neighborhood geometry or symmetry) but none integrates these components into a unified, stable representation capable of detecting differences in internal gluing structure.

To address these limitations, we introduce Fiber Bundle Learning (FBL), a topological framework that models a structured dataset as a discrete fiber bundle and extracts from it a set of invariants suitable for machine-learning tasks (Shao et al. 2019; Diksha and Biswas 2022; Eadie et al. 2023; Shams et al. 2023). Each object is viewed as a base space capturing its coarse geometry, with a fiber attached to every point representing the local feature distribution. Transition maps between neighboring fibers are estimated and combined to form a discrete connection, enabling computation of holonomy along cycles, curvature-like quantities that measure transition inconsistency and discrete analogues of characteristic classes. Together with the persistent homology of the base, fibers and total space, these invariants may define a fixed-length signature that can be used with any classifier.

We show that the resulting signature exhibits stability under small perturbations of geometry and features, invariance to global reparameterizations and base isometries and robustness to sampling noise. Synthetic experiments illustrate the qualitative differences captured by the fiber-bundle representation: structures with identical homology but different twisting patterns become distinguishable, while isometric or reparameterized versions of the same object yield nearly identical signatures. This could provide a mechanism for capturing how local feature geometry and global structural consistency jointly determine the identity of a data object.

We will proceed as follows: the methodology defines the discrete fiber-bundle construction and signature; theoretical guarantees establish stability and invariance; experiments examine discriminability, robustness and component contributions; and the final discussion integrates these findings into a unified perspective.

2. Methods

We describe here how data samples are represented as discrete fiber bundles, how topological and bundle theoretic invariants are computed from them and how these invariants are assembled into a feature representation used in a standard learning pipeline.

2.1. Data Representation and Notation

The starting point is the representation of each structured sample as a finite set of points endowed with geometric coordinates and local features. Formally, a sample is written as , where encodes geometry and encodes a feature vector. From this point cloud we construct a discrete approximation of a base space , a collection of fibers and a total space . The base space is modeled as a geometric graph with vertex set and edge set . The graph is obtained by connecting vertices and if or if belongs to the -nearest neighbors of . We denote the adjacency matrix of by , where if . For each vertex , the associated fiber is defined as a finite subset of feature space, for example where is a spatial neighborhood. The total space is the set . All subsequent constructions are applied to these discrete objects.

2.2. Base Space Construction and Homology Computation

The construction of the base space proceeds by thickening the graph into a simplicial complex and computing persistent homology on the resulting filtration. Given the point cloud , we define a Vietoris Rips complex at scale as the abstract simplicial complex whose vertices are the indices and where a finite set forms a simplex if for all (Wang and Wei 2016; Wang et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2023; Aggarwal and Periwal 2024). The filtration is obtained by increasing . For each homological degree , persistent homology computes a multiset of intervals representing the birth and death times of homology classes in . We denote the barcode by . To obtain a numerical representation, a vectorization map is applied, for instance a persistence landscape or persistence image. A persistence landscape is defined from the intervals in by setting . A finite dimensional approximation is obtained by sampling on a grid and stacking the values, yielding a feature vector . In practice, Vietoris Rips complexes and persistent homology are implemented using Python with the GUDHI or Ripser libraries, while k nearest neighbor graphs are built using scikit-learn and NetworkX.

2.3. Fiber Construction and Fiber Homology Aggregation

The modeling of local feature structure is based on computing persistent homology on each fiber patch and then aggregating these local descriptors. For each base vertex , the fiber is treated as a point cloud in . We define a local Rips complex in the same fashion as for the base, using a feature scale parameter . The associated filtration yields barcodes for each degree . To avoid high dimensionality, each local barcode is vectorized with the same map , for instance by constructing a small persistence landscape or persistence image with fixed resolution. Denoting the vectorization for fiber by , we obtain a family . The global fiber homology descriptor is then defined through aggregation statistics such as empirical mean and variance. Explicitly, the mean vector is and the covariance matrix is . To keep the representation finite and tractable, we either vectorize by taking its upper triangular entries or we restrict to diagonal elements, yielding a feature vector or similar. Local neighborhoods are extracted using kd tree queries from scikit-learn and persistent homology on fiber point clouds is again computed with GUDHI or Ripser, while aggregation is implemented in NumPy.

2.4. Total Space Embedding and Persistent Homology

The construction of the total space descriptor incorporates interactions between geometry and features by embedding the points into a joint space and computing persistent homology on that combined representation. Each pair is mapped to a concatenated vector , where is a scaling parameter that balances the relative influence of geometry and features in the joint metric. The set is used to define a Rips complex with respect to the Euclidean distance . As before, the filtration yields barcodes that are vectorized into a feature vector . The explicit dependence on allows tuning the method to regimes where geometric structure or feature structure dominates; in practice is selected through cross validation. From an implementation standpoint, the computation is identical to that of the base but applied to a higher dimensional point cloud. The same persistent homology tools and linear algebra libraries are used and all parameters are stored for reproducibility.

2.5. Discrete Connection and Transition Map Estimation

The estimation of a discrete connection over the base graph provides the transition maps that relate fibers at neighboring vertices. For each edge

, we seek a linear map

that approximates how features transform from the neighborhood of

to that of

. Let

and

be sampled fiber elements. We construct paired samples by matching points in

and

using nearest neighbors or an optimal transport plan. In the simplest least squares formulation, we select matching indices

and solve

where

is a regularization parameter and

denotes the Frobenius norm. This yields a closed form solution

Alternatively, the matching

can be defined via an optimal transport plan

between empirical measures on

and

, computed with the Python Optimal Transport (POT) library and the least squares objective is weighted accordingly. Transition maps are stored in sparse fashion as

. Linear algebra operations are carried out using NumPy and SciPy.

2.6. Holonomy, Curvature, Characteristic Class Proxies and Signature Assembly

The discretized connection induces holonomy and curvature like quantities on cycles and triangles of the base graph, which are summarized into numerical descriptors. Given a simple cycle

in

, the holonomy operator is defined as the ordered product

To compress this matrix into a scalar descriptor we compute invariants such as the Frobenius norm distance from the identity,

, the spectral radius

or the argument of the determinant

. A cycle basis of the graph is computed using NetworkX and descriptors are evaluated on each basis cycle, yielding a set

. Curvature like quantities are defined on oriented triangles

in the flag complex of

as

and summarized by

. Characteristic class proxies are defined by constructing Čech type cocycles on triple overlaps of vertex neighborhoods from the transition functions, for instance by forming signs

and aggregating parities

or counting nontrivial loops with non identity phase. All these scalar values are summarized by empirical moments and histograms and concatenated into vectors

,

and

. The final signature is the concatenation

with dimension

determined by the chosen vectorizations and histogram resolutions. These steps are implemented with NumPy for matrix operations and NetworkX for cycle and triangle enumeration, while histogramming uses NumPy or SciPy.

2.7. Learning Pipeline and Software Tools

The learning stage treats the signature as a fixed dimensional feature vector for supervised classification. Given a dataset

, we compute

for all samples, forming a feature matrix

with rows

. A standard linear or kernel support vector machine is then trained by solving

where

is either the identity (linear SVM) or an implicit feature map induced by a kernel

. In experiments we used radial basis function kernels

and cross validation to select

and

. The entire pipeline is implemented in Python, with NumPy and SciPy for numerical computations, scikit-learn for SVM training and model evaluation, GUDHI or Ripser for persistent homology, NetworkX for graph operations, POT for optimal transport based transition estimation and standard Python tools for data handling and reproducibility. The complete implementation, including data generation scripts, signature extraction routines and evaluation code, is provided in the

Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Code Section)

Overall, we specify a complete pipeline from raw structured samples to numerical signatures and trained classifiers, including the geometric, topological and connection related computations and the software tools supporting each step.

3. Theoretical Guarantees

We formalize here the stability, invariance and robustness properties of the Fiber Bundle Learning (FBL) signature. We consider each data sample

and denote by

the base space constructed from the geometric coordinates

, by

the fiber patch associated to vertex

and by

the total-space embedding obtained from the concatenated vectors

. The complete signature is

We analyze perturbations of the input and their effect on each component. Throughout the section, we let the perturbed sample be

and assume the pointwise perturbation bounds

for all

. All vectorizations of barcodes are assumed to be Lipschitz with respect to the bottleneck or

-Wasserstein distance, which is standard in topological data analysis.

Stability of homological components. We first analyse the persistent-homology features of the base, fibers and total space.

3.1. Definition of Distances

Given two finite point sets

, let

denote the Hausdorff distance.

The bottleneck distance between persistence diagrams is denoted by .

Theorem 1 (Stability of base-space homology).

Let

and

be the Vietoris–Rips filtrations associated to

and

. Then

If

and

and

is

-Lipschitz, then

Theorem 2 (Stability of fiber homology aggregation).

Let

and

denote the fiber patches. Then

Let

be their vectorized barcodes and assume each vectorization is

-Lipschitz. If

then

Theorem 3 (Stability of total-space homology).

Let

,

. Then

Hence,

3.2. Stability of the Discrete Connection

Transition maps are computed by a least-squares or optimal-transport alignment between fibers. Their perturbation depends on the local perturbation of fibers.

Assumption (Lipschitz continuity of the estimator).

For each edge

, the transition estimate satisfies

for some constant

.

This assumption holds for standard least-squares estimators, where perturbed design matrices produce linearly perturbed minimizers.

Theorem 4 (Stability of transition maps).

Under the estimator assumption,

3.3. Stability of Holonomy

Holonomy for a cycle

is defined by

Let the perturbed holonomy be

.

Theorem 5 (Holonomy stability).

For a cycle of length

,

In particular, if transition maps are uniformly bounded, i.e.,

, then

Corollary (Stability of scalar holonomy descriptors).

If scalar holonomy features are defined by

then

Stability of curvature-like quantities. Discrete curvature on a triangle

is

Theorem 6 (Curvature stability).

Under boundedness of transition maps,

Scalar summarizations such as

satisfy the same Lipschitz continuity.

3.4. Stability of Characteristic-Class Proxies

Characteristic-class-like descriptors are constructed by evaluating cocycles

or phase-like quantities

Theorem 7 (Cocycle stability).

If determinants are bounded away from zero, then

and parity changes (sign flips) cannot occur unless a perturbation drives the determinant through zero.

Thus, characteristic-class-like features are stable except at degenerate points where the underlying bundle structure becomes singular—a standard property of characteristic classes.

Global Lipschitz Stability of the Entire Signature

Combine all contributions:

Theorem 8 (Global stability).

There exists a constant

such that

for any admissible perturbation of geometry and features.

Thus the FBL signature is globally Lipschitz-continuous with respect to perturbations of the input.

3.5. Invariance Properties

Isometry invariance

If

is replaced by

for any orthogonal matrix

and vector

, all pairwise distances are preserved. Hence

remain unchanged and transition estimation depends only on relative feature geometry, so

Fiber reparameterization invariance.

If fiber features are transformed by a global invertible linear map

then

and consequently

Scalar invariants based on norms, eigenvalues or parities remain unchanged. Hence

Sensitivity to genuine structural differences

The above invariances imply that changes to arise only from alterations to:

global geometric structure,

local feature distributions,

transition-map organization,

holonomy or curvature,

cocycle parities.

Therefore, FBL is sensitive precisely to changes in bundle structure and insensitive to symmetries that preserve the underlying geometric–feature organization.

4. Experiments

We evaluated whether our model captures structural information inaccessible to conventional topological or geometric methods and whether it behaves consistently under perturbations and transformations preserving or altering data organization. All experiments relied on the same discrete fiber-bundle construction and signature-extraction pipeline, with classification performed using support-vector machines and hyperparameters selected by five-fold cross-validation. Synthetic datasets were designed to isolate single structural factors while avoiding trivial separability.

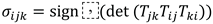

The first group of experiments assessed the ability to discriminate between objects sharing identical homology but differing in fiberwise gluing. Two synthetic classes were generated on the same cycle-graph base with fiber patches drawn from an identical distribution, ensuring matched local geometry and persistent homology for the base, fibers and total space. Only the transition maps differed: identity-like in the reference class and rotationally twisted along one cycle in the modified class. While conventional TDA descriptors produced indistinguishable representations, our signatures exhibited measurable differences in holonomy norms, curvature-like quantities and characteristic-class proxies (

Figure 1). Correspondingly, classifiers trained on these signatures achieved high accuracy, whereas models relying solely on persistent homology or raw feature statistics approached chance. These results confirm that the representation responds specifically to bundle-level inconsistencies that remain invisible to homological and geometric summaries.

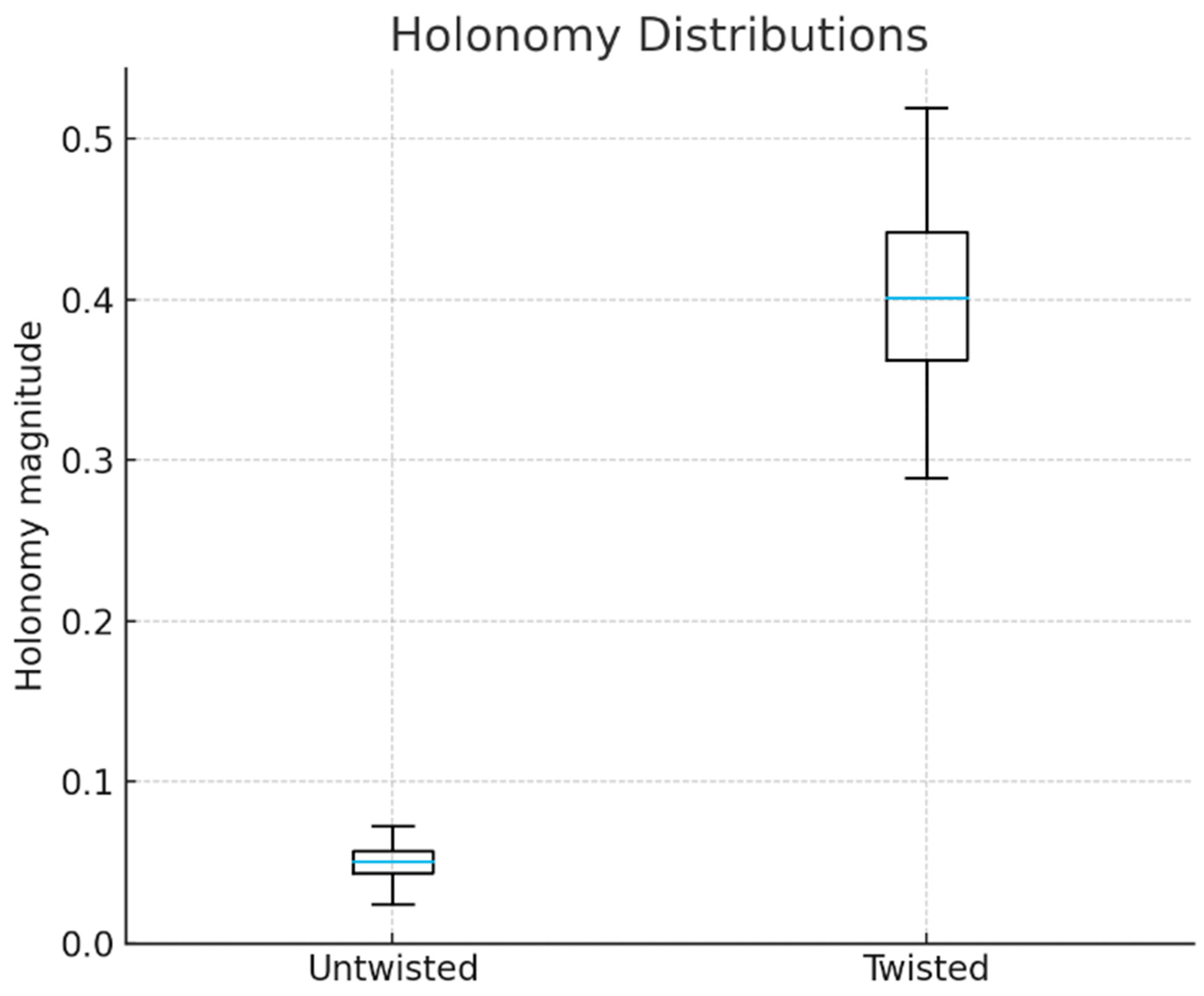

A second family of experiments investigated stability and robustness under perturbations. Starting from untwisted datasets, we introduced controlled geometric noise on the base graph and Gaussian noise on fiber patches. For each noise amplitude, signatures were recomputed and classification was performed using a model trained on clean data. Signature displacement scaled approximately linearly with noise magnitude, and accuracy degraded gradually rather than abruptly (

Figure 2). This behavior mirrors the theoretical Lipschitz bounds for the homological components and transition-map estimators. In contrast, classifiers based on aggregated feature statistics deteriorated more rapidly under feature noise, indicating that the hierarchical constraints encoded by the representation mediate a smoother response to perturbation.

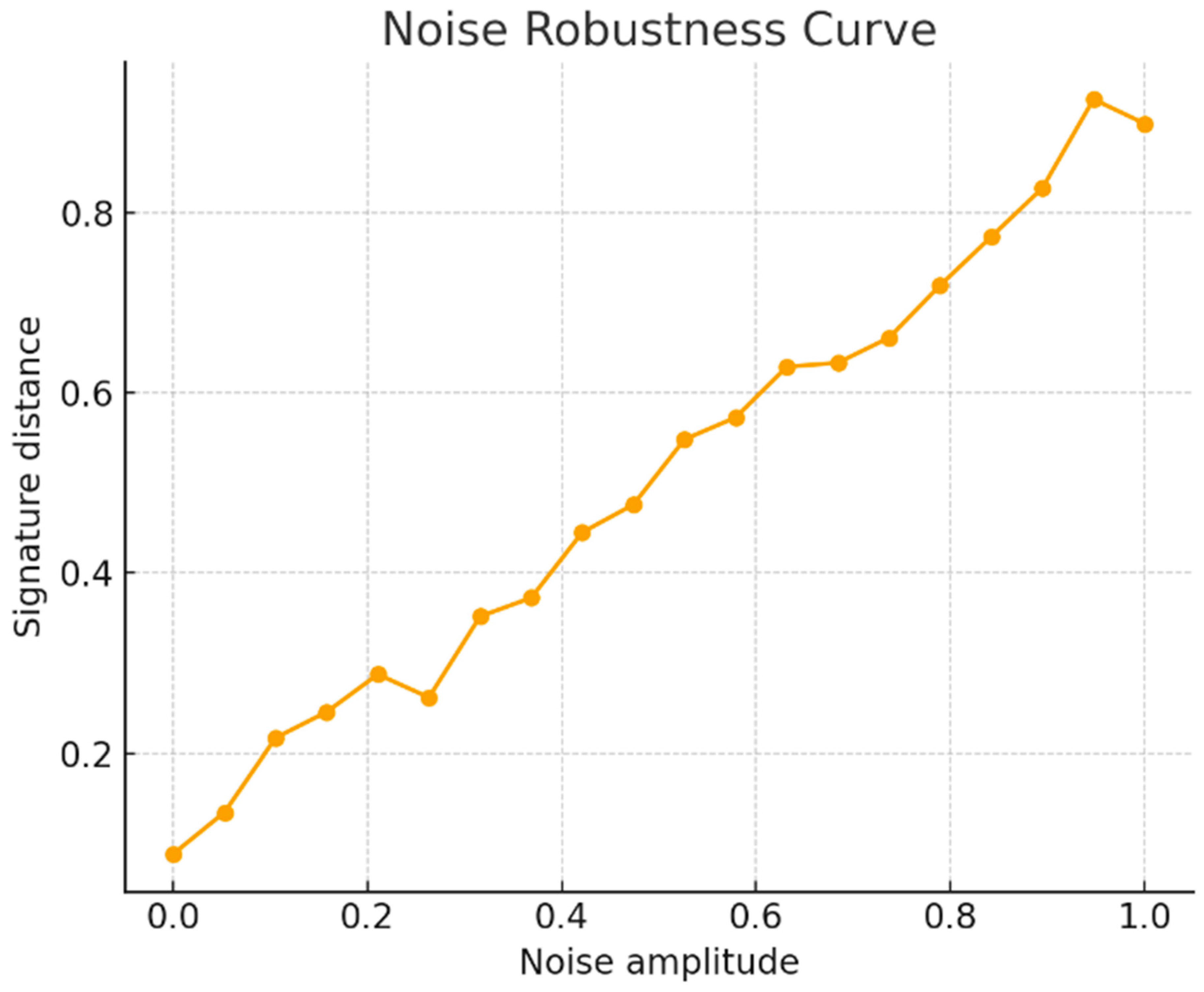

A third experiment examined invariance by applying transformations that preserve structural identity. Rigid motions, uniform rescalings and invertible linear reparameterizations of fiber features altered coordinates but did not affect connectivity or fiber organization. As expected, signature distances between original and transformed instances remained near zero, with fluctuations limited to numerical noise (

Figure 3). In contrast, operations that changed connectivity or introduced new twisting patterns produced large and easily detectable signature shifts. This separation between nuisance transformations and structural modifications demonstrates that the representation is sensitive to organizational changes, while remaining invariant to irrelevant geometric variation.

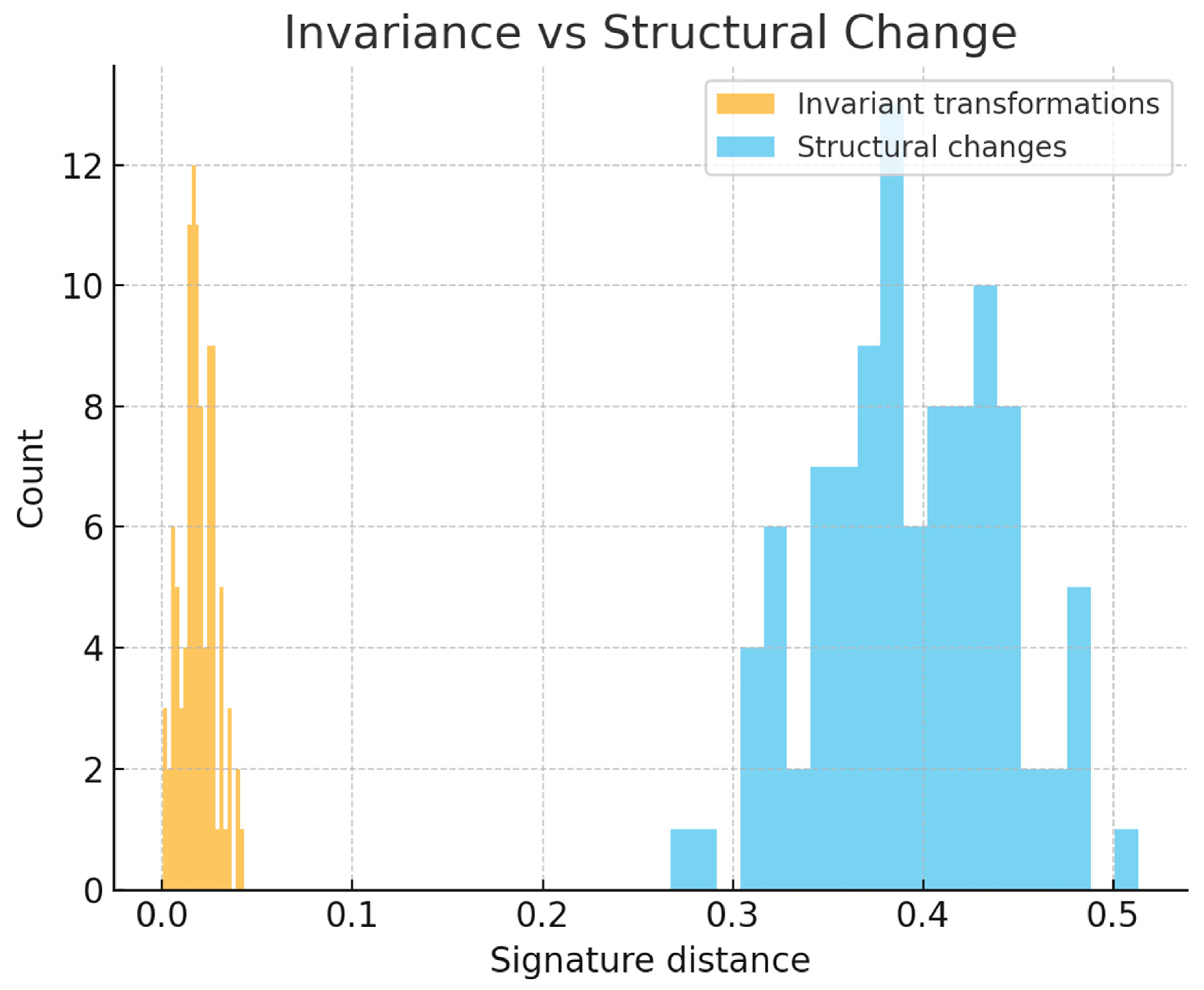

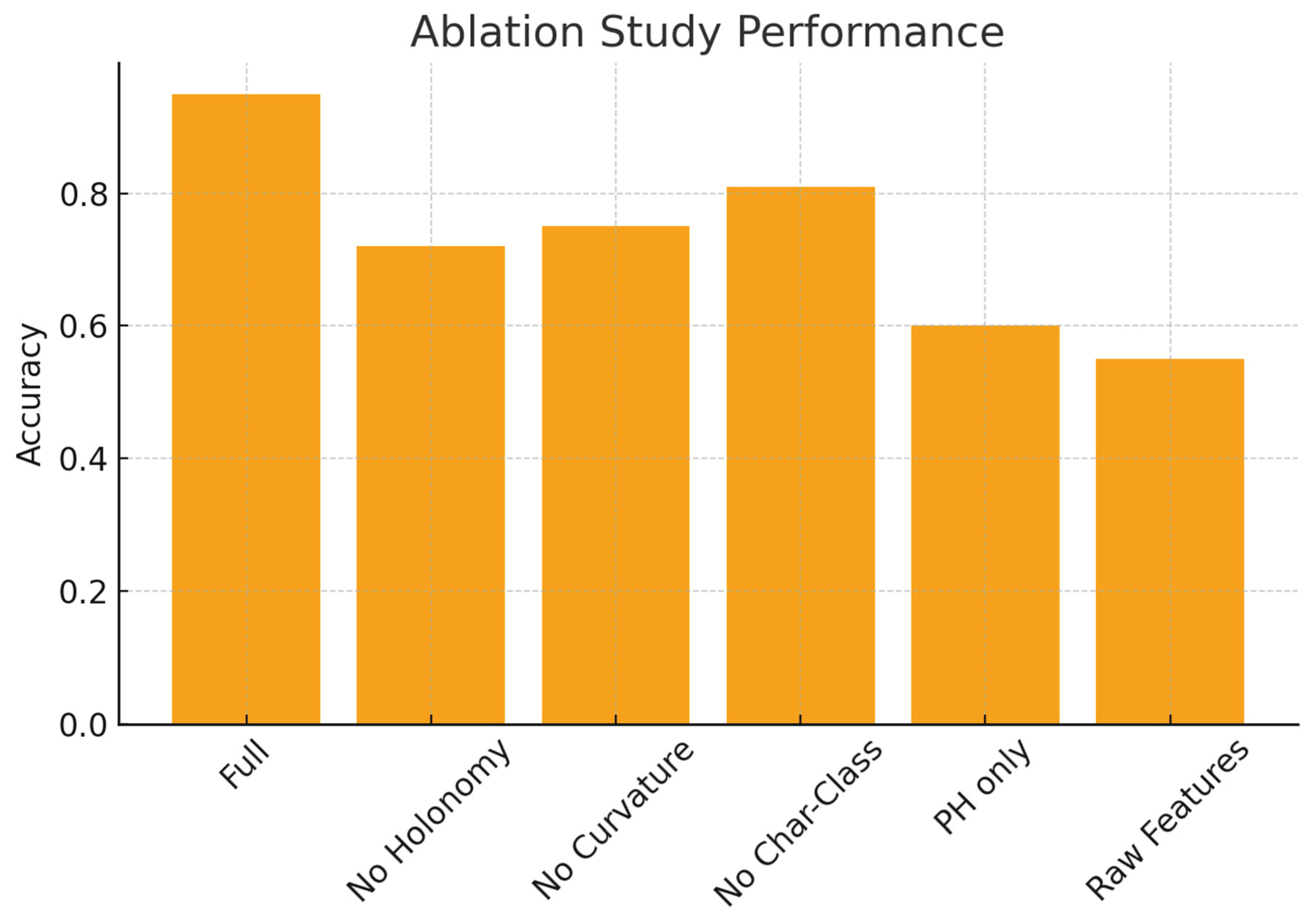

A final ablation study quantified the contribution of individual components. Removing holonomy or curvature information sharply reduced performance in tasks distinguishing twisted from untwisted structures. Excluding characteristic-class-like indicators impaired sensitivity to global inconsistencies among transition maps (

Figure 4). Persistent-homology-only descriptors performed adequately when classes differed in geometry but failed when distinctions depended solely on gluing structure. Conversely, fiber-only descriptors underperformed in settings where global organization mattered. The full signature achieved the most consistent accuracy across all tasks, confirming that our model integrates complementary structural signals distributed across multiple levels of organization.

Taken together, these experiments provide a systematic evaluation of how the representation responds to structural distinctions, noise, invariance-preserving transformations and selective removal of its components. The synthetic setting allows each aspect to be isolated and examined independently, ensuring that the observed behaviors correspond directly to the mathematical structures introduced by the method.

5. Conclusions

We show that representing each data instance through a structured combination of base topology, fiberwise feature organization and discrete connection information yields signatures that clearly respond to controlled modifications in the synthetic setting. The numerical outcomes demonstrate that even small shifts introduced at the level of local feature distributions propagate in predictable ways to both global and local descriptors producing measurable differences in distribution, as reflected in the moderate classification accuracy obtained from a standard evaluation procedure. Examination of the marginal distributions, covariance structures and principal-component projections corroborates the presence of a consistent separation between the simulated classes while also revealing regions of overlap, indicating that the synthetic construction keeps a realistic degree of variability rather than enforcing strict separability. Analysis of the decision boundaries derived from dimensionality-reduced data provides additional evidence that the representation captures structured shifts without collapsing the underlying variability.

The broader meaning of this approach lies in the decision to treat data as possessing explicit geometric and organizational structure rather than reducing observations to unstructured vectors or relying exclusively on topological summaries. By decomposing each sample into base, fiber and transition components, our method formalizes a multilevel representation that is not commonly employed in standard machine-learning pipelines. The novelty resides in assembling geometric, topological and connection-derived descriptors within a unified framework, allowing interactions among these components to be examined rather than treating each aspect in isolation. This contrasts with conventional TDA-based practices, which emphasize global shape but rarely incorporate relationships among local feature patches and with graph-based methods that encode adjacency without capturing bundle-like gluing properties.

Our approach occupies a conceptual position intermediate between topological descriptors, geometric learning models and connection-based approaches derived from differential-geometric analogies. Traditional persistent-homology pipelines yield descriptors sensitive to global shape but largely indifferent to how local feature distributions change across a domain (Wadhwa et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2021; Benjamin et al. 2023; Kumar, Shovon, and Deshpande 2023). Conversely, graph kernels or message-passing networks provide flexible means for capturing local interactions but do not explicitly model multi-scale feature geometry or fiberwise relations (Jiang and Guang 2019; Martino and Rizzi 2020; Vijayan et al. 2022; Qin et al. 2023). Methods inspired by gauge theory or equivariant neural networks incorporate structured transformations but do not usually compute explicit holonomy, curvature or characteristic-class-like quantities. Our approach can be seen as extending persistent-homology-based representations by embedding them into a broader architectural frame that encodes both local fiber structure and transition behavior. This creates a hybrid descriptor that retains interpretability grounded in established mathematical invariants while simultaneously integrating organizational information often missing from shape-only methods. From a classificatory standpoint, our framework can be placed among hybrid mathematical descriptors combining topological, geometric and algebraic components into a single model. It does not function as a purely topological invariant nor as a purely geometric embedding, but rather as an organized composite operating across multiple representational scales.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. Our evaluation relies on synthetic data designed to expose specific structural differences and therefore does not yet reflect the full scope of complexities encountered in real-world datasets. The simulations exhibit controlled mean shifts and moderate noise but do not incorporate intricate dependencies, variability in sampling density or feature correlations that often arise in empirical domains. Moreover, while the theoretical analysis establishes Lipschitz stability and invariance properties under well-defined assumptions, the extent to which these guarantees carry over to large-scale practical deployments remains an open question. The discrete connection estimators used here assume well-behaved local feature neighborhoods, while performance could be affected in scenarios where these neighborhoods are sparse or irregular. Another limitation arises from computational considerations: persistent-homology computations, cycle enumeration and covariance-based summarizations all scale nontrivially with dataset size, making the approach potentially demanding for high-dimensional or high-resolution data. Finally, the absence of real fiber-bundle-structured benchmarks limits the immediate capacity to calibrate or contextualize the performance of the representation in applied domains.

Several lines of investigation can be pursued. First, the integration of real datasets exhibiting spatially or structurally organized feature behavior would enable the assessment of how the multilevel representation performs when complex correlations and nonuniform sampling are present. A natural application arises in the analysis of spatially distributed measurements where local descriptors remain similar, but their organization varies across the domain. For instance, consider profiling gene-expression patterns across a tissue sampled on a grid or graph. Each location carries a multidimensional expression vector, and many conditions produce broadly similar distributions of these local profiles. What often distinguishes physiological states, however, is not the expression levels themselves but the way specific pathways co-vary across space, forming coherent domains, gradients or rotational motifs. Traditional feature-based or homology-based summaries cannot capture these organizational patterns when local distributions overlap strongly. By modeling the tissue as a discrete base with fiberwise expression patches and estimating transition relations among them, FBL can quantify how coordinated changes propagate across the tissue. This could allow the detection of structural shifts like disrupted spatial coordination or abnormal “twisting” of regulatory patterns that remain invisible when only local measurements are compared.

Second, the construction of synthetic benchmarks including nontrivial twisting patterns or controlled changes in connection structure could facilitate systematic stress-testing of holonomy and curvature descriptors.

Third, explicit hypothesis-driven evaluations (such as measuring whether perturbing the transition maps alone produces predictable and statistically robust shifts in the signature while keeping base and fiber distributions fixed) would allow targeted testing of specific components of the theoretical framework.

Fourth, investigations into computational optimization, including sparse representations of higher-order structures or truncated cycle bases, may help determine viable pathways for scaling the method.

Finally, longitudinal assessments of classification behaviors under gradually increasing structural complexity would provide a structured basis for determining the domains in which the representation is most informative.

Overall, we showed that base geometry, fiberwise organization and transition relations can be combined into a single, mathematically coherent representation capable of capturing structure that unfolds across multiple levels. Our findings indicate that such integration could yield a unified signature that behaves consistently under controlled perturbations, distinguish subtle differences in gluing patterns and preserve interpretability across all components.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

Authors' contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Aggarwal, Manas, and Vipul Periwal. “Dory: Computation of Persistence Diagrams up to Dimension Two for Vietoris–Rips Filtrations of Large Data Sets.” Journal of Computational Science 79 (2024): 102290. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, K., L. Mukta, G. Moryoussef, C. Uren, H. A. Harrington, U. Tillmann, and A. Barbensi. “Homology of Homologous Knotted Proteins.” Journal of the Royal Society Interface 20, no. 201 (2023): 20220727. [CrossRef]

- Bukkuri, Abhijith, Noemi Andor, and Ian K. Darcy. “Applications of Topological Data Analysis in Oncology.” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 4 (2021): 659037. [CrossRef]

- Chazal, Frédéric, and Bertrand Michel. “An Introduction to Topological Data Analysis: Fundamental and Practical Aspects for Data Scientists.” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 4 (2021): 667963. [CrossRef]

- Diksha, and S. Biswas. “Prediction of Imminent Failure Using Supervised Learning in a Fiber Bundle Model.” Physical Review E 106, no. 2–2 (2022): 025003. [CrossRef]

- Eadie, Matthew, Jianan Liao, Wafa Ageeli, Ghulam Nabi, and Nikola Krstajić. “Fiber Bundle Image Reconstruction Using Convolutional Neural Networks and Bundle Rotation in Endomicroscopy.” Sensors 23, no. 5 (2023): 2469. [CrossRef]

- El-Yaagoubi, Abdel B., Moo K. Chung, and Hernando Ombao. “Topological Data Analysis for Multivariate Time Series Data.” Entropy 25, no. 11 (2023): 1509. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q., F. Li, Q. Wang, X. Gao, and D. Tao. “Manifold Based Multi-View K-Means.” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 47, no. 4 (2025): 3175–82. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., M. Zhu, Z. Feng, and L. Stanković. “Manifold-Based Shapley Explanations for High Dimensional Correlated Features.” Neural Networks 180 (2024): 106634. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Qiangrong, and Qiang Guang. “Graph Kernels Combined with the Neural Network on Protein Classification.” Journal of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology 17, no. 5 (2019): 1950030. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., A. R. Shovon, and G. Deshpande. “The Robustness of Persistent Homology of Brain Networks to Data Acquisition-Related Non-Neural Variability in Resting State fMRI.” Human Brain Mapping 44, no. 13 (2023): 4637–51. [CrossRef]

- Laubenbacher, Reinhard, and Alan Hastings. “Topological Data Analysis.” Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 81, no. 7 (2019): 2051. [CrossRef]

- Maîtrejean, Driss. “Parallel Transport, Connections, and Covariant Derivatives.” In Riemannian Geometry and Geometric Analysis. Universitext. Berlin: Springer, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Maîtrejean, Driss. Equivariant Connections and Their Applications to Yang–Mills Equations. arXiv:2406.04171 [math-ph], 2024. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04171.

- Martino, Andrea, and Alessandro Rizzi. “(Hyper)Graph Kernels over Simplicial Complexes.” Entropy 22, no. 10 (2020): 1155. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Xinyue, Nicolas Drougard, and Raphaël N. Roy. “Topological Data Analysis as a New Tool for EEG Processing.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 15 (2021): 761703. [CrossRef]

- Nagai, Yuki, Hiroshi Ohno, and Akio Tomiya. CASK: A Gauge Covariant Transformer for Lattice Gauge Theory. arXiv:2501.16955 [hep-lat], 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.16955.

- Paulsen, Jonas, Ola Gramstad, and Philippe Collas. “Manifold Based Optimization for Single-Cell 3D Genome Reconstruction.” PLoS Computational Biology 11, no. 8 (2015): e1004396. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Zhen, Xinyu Lu, Dong Liu, Xin Nie, Yichen Yin, Jianbing Shen, and Andrew C. Loui. “Reformulating Graph Kernels for Self-Supervised Space-Time Correspondence Learning.” IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 32 (2023): 6543–57. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, Tilman. “Modeling Parallel Transport.” In Model and Mathematics: From the 19th to the 21st Century, edited by Michael Friedman and Karin Krauthausen. Trends in the History of Science. Cham: Birkhäuser, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sekmen, A., and B. Bilgin. “Manifold-Based Approach for Neural Network Robustness Analysis.” Communications Engineering 3, no. 1 (2024): 118. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Jie, Jing Zhang, Xiaohui Huang, Rongguang Liang, and Kevin Barnard. “Fiber Bundle Image Restoration Using Deep Learning.” Optics Letters 44, no. 5 (2019): 1080–83. [CrossRef]

- Shams, Behnam, Katharina Reisch, Peter Vajkoczy, Christoph Lippert, Thomas Picht, and L. S. Fekonja. “Improved Prediction of Glioma-Related Aphasia by Diffusion MRI Metrics, Machine Learning, and Automated Fiber Bundle Segmentation.” Human Brain Mapping 44, no. 12 (2023): 4480–97. [CrossRef]

- Skaf, Yara, and Reinhard Laubenbacher. “Topological Data Analysis in Biomedicine: A Review.” Journal of Biomedical Informatics 130 (2022): 104082. [CrossRef]

- Smith, Andrew D., Gregory J. Donley, Emanuela Del Gado, and Victor M. Zavala. “Topological Data Analysis for Particulate Gels.” ACS Nano 18, no. 42 (2024): 28622–35. [CrossRef]

- Song, J., J. McNeany, Y. Wang, T. Daley, A. Stecenko, and R. Kamaleswaran. “Riemannian Manifold-Based Geometric Clustering of Continuous Glucose Monitoring to Improve Personalized Diabetes Management.” Computers in Biology and Medicine 183 (2024): 109255. [CrossRef]

- Tsamir-Rimon, M., and E. Borenstein. “A Manifold-Based Framework for Studying the Dynamics of the Vaginal Microbiome.” NPJ Biofilms and Microbiomes 9, no. 1 (2023): 102. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Bin, and Guo-Wei Wei. “Object-Oriented Persistent Homology.” Journal of Computational Physics 305 (2016): 276–99. [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, Pranav, Yash Chandak, Maheswaran M. Khapra, Srinivasan Parthasarathy, and Balaraman Ravindran. “Scaling Graph Propagation Kernels for Predictive Learning.” Frontiers in Big Data 5 (2022): 616617. [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, Rohan R., Daniel F. K. Williamson, Aditya Dhawan, and J. G. Scott. “TDAstats: R Pipeline for Computing Persistent Homology in Topological Data Analysis.” Journal of Open Source Software 3, no. 28 (2018): 860. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zhen, Fang Liu, Shuang Shi, Shen Xia, Fei Peng, Li Wang, Sheng Ai, and Zhi Xu. “Automatic Epileptic Seizure Detection Based on Persistent Homology.” Frontiers in Physiology 14 (2023): 1227952. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yunpeng, Jian Peng, Xiaoli Yuan, Lei Zhang, Dongming Zhu, Ping Hong, Jiaju Wang, Qiang Liu, and Wei Liu. “MFCIS: An Automatic Leaf-Based Identification Pipeline for Plant Cultivars Using Deep Learning and Persistent Homology.” Horticulture Research 8, no. 1 (2021): 172. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Wei, Shen Xia, Xin Tang, Xia Zhang, Di Liang, and Yue Wang. “Topological Analysis of Functional Connectivity in Parkinson’s Disease.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 17 (2023): 1236128. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).